Abstract

Background:

The stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) is linked to cardiovascular outcomes. However, its role in predicting atrial fibrillation (AF) recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) remains unclear. Therefore, this study investigated the SHR as a potential prognostic biomarker for post-RFCA AF recurrence.

Methods:

In this retrospective cohort study, 446 symptomatic non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients who underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation were followed for 12–26 months. The stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) was calculated as admission fasting blood glucose (mmol/L)/[1.59 × HbA1c (%)−2.59]. Patients were classified based on SHR levels. The primary endpoint was atrial fibrillation recurrence, and the secondary endpoints were cardiovascular events and a composite endpoint comprising relevant clinical outcomes.

Results:

AF recurrence occurred in 128 patients (28.7%). Patients in the recurrence group exhibited significantly higher SHR levels (p < 0.001). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis identified an optimal SHR cutoff value of 0.91 for predicting recurrence. Furthermore, even after multivariable adjustment for diabetes, alcohol consumption, antiarrhythmic drug use, SGLT2 inhibitor use, left atrial diameter (LAD), and uric acid levels, elevated SHR remained significantly associated with AF recurrence (HR: 3.379, 95% CI: 2.272–5.025, P < 0.001). ROC analysis demonstrated that SHR had superior predictive performance compared with other glycemic parameters, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.74–0.84), yielding a sensitivity of 79.7% and a specificity of 68.4%. A prognostic nomogram incorporating six independent predictors was developed to estimate 1- and 2-year recurrence-free survival. Formal interaction tests indicated no significant effect modification by diabetes status (P for interaction = 0.432), with consistent SHR-associated recurrence risks observed in both diabetic and non-diabetic subgroups. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these findings, as statistical significance was maintained after excluding patients with prior open-heart surgery and when modeling SHR as tertiles.

Conclusions:

The increase in SHR is significantly correlated with atrial fibrillation recurrence and composite events after RFCA. These findings support its potential clinical application value in improving risk stratification and prognostic assessment of this patient population.

1 Introduction

AF is the most common cardiac arrhythmia globally and has witnessed a sustained increase. Currently, it affects over 60 million people worldwide (1–3). This rise is associated with longer lifespans and lifestyle changes, and it corresponds to higher risks of stroke, heart failure, and all—cause mortality (4). RFCA has become the first—line treatment for drug—resistant AF, restoring sinus rhythm by electrically isolating the pulmonary veins (5, 6). Despite technological advancements, postoperative AF recurrence remains high, with approximately 30%–40% of patients experiencing relapse within one year, which is attributed to multiple factors, including atrial structural remodeling and inflammatory responses (6, 7). Identifying biomarkers to guide intervention and optimize postoperative risk stratification and management has become a key focus of current clinical research.

Accumulating evidence from preliminary studies has implicated metabolic disturbances, especially hyperglycemia, as a critical factor in post-RFCA AF recurrence (8–10). Elevated blood glucose on admission, which often reflects stress hyperglycemia, serves as an independent predictor of adverse prognosis in various cardiovascular conditions, including heart failure, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmias (11, 12). However, this measure lacks specificity, as it may be influenced by either chronic hyperglycemia or an acute physiological stress response, which precludes its utility in precisely evaluating the acute dysmetabolic state.

Stress hyperglycemia at admission may originate from either chronic hyperglycemia or an acute physiological stress response, limiting its ability to accurately reflect true acute dysglycemia. In contrast, the stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR)—a novel metric integrating acute admission blood glucose with chronic glycemic levels (as reflected by glycosylated hemoglobin)—can more effectively evaluate genuine acute hyperglycemic status, independent of pre-existing diabetes (13, 14). The clinical value of SHR is well established in the literature, where it has been associated with critical outcomes such as thrombotic burden, coronary artery disease severity, post-stroke cerebral edema, and hospital-acquired infection risk (12). Moreover, elevated SHR has demonstrated prognostic utility in predicting clinical outcomes, showing a significant correlation with 1-year all-cause mortality in both American and Chinese cohort studies (15, 16).

Despite this, the role of SHR in predicting outcomes following atrial fibrillation ablation remains systematically underexplored, as existing studies have primarily focused on conventional diabetic indicators while overlooking the independent prognostic impact of acute glycemic abnormalities.

Our study's specific objectives include (1) quantifying the association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) and postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) recurrence, defined as the recurrence of AF three months after ablation, and (2) evaluating the predictive value of the SHR for major cardiovascular events, including stroke, heart failure hospitalizations, and cardiovascular deaths. The research results are expected to provide new evidence for personalized interventions during the perioperative period, such as blood glucose control strategies, and to improve the precision of AF management.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and population

This retrospective study consecutively enrolled 501 symptomatic patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) at our center between January 2023 and September 2024. The study aimed to include all eligible patients treated during this period.The inclusion criteria were: (1) aged 18–80 years; (2) met the ESC diagnostic criteria for nonvalvular AF; and (3) availability of complete follow-up data for at least 12 months post-procedure. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) prior open-heart surgery; (2) life-threatening comorbidities, including active infectious diseases or severe hepatic/ renal dysfunction. Severe hepatic insufficiency was defined as liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class B or C) or baseline aminotransferase levels exceeding three times the upper limit of normal. Severe renal insufficiency was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m² (consistent with chronic kidney disease stages 4–5) or a requirement for renal replacement therapy (dialysis). (3) missing crucial baseline data required for analysis (e.g., HbA1c, fasting blood glucose). After applying these criteria, 55 patients were excluded. The specific reasons for exclusion were: [missing HbA1c or glucose data (n = 45), presence of life-threatening comorbidities (n = 10)]. Consequently, the final analysis cohort comprised 434 patients.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (Approval No: YX2024-232). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2 Ablation procedure

This study exclusively enrolled patients who underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA); those treated with cryoballoon ablation (CRYO) were excluded. Preprocedural data on antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) use and prior cardioversion history were systematically collected for all participants. All RFCA procedures were performed under conscious sedation. Following transseptal puncture, an initial heparin bolus (100 IU/kg) was administered, with subsequent continuous infusion to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) between 300 and 350 s. The procedural cornerstone was extensive pulmonary vein isolation (PVI), performed using a three-dimensional electroanatomical mapping system (CARTO, Biosense Webster, or Ensite, Abbott).Continuous and contiguous point-by-point lesions were created around the ipsilateral pulmonary veins to establish a wide-area circumferential ablation line. The endpoint was successful electrical isolation of all pulmonary veins, confirmed by the absence or dissociation of PV potentials using a circular mapping catheter. This endpoint was achieved in all enrolled patients.

Ablation for non-pulmonary vein (non-PV) targets was performed at the operator's discretion based on clinical and electrophysiological findings. In patients with documented or inducible typical atrial flutter, a cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI) ablation line was created to achieve bidirectional conduction block. For patients with organized atrial tachycardias (AT) or suspected non-PV triggers, further mapping and ablation were conducted. If sustained AF persisted after PVI, electrical cardioversion was applied to restore sinus rhythm.

2.3 Data collection

Data were extracted from the hospital's electronic medical record system. Sociodemographic details included age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, and alcohol consumption-the latter quantified as significant intake (>210 g/week for men and >140 g/week for women). Medical history encompassed hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, cerebral apoplexy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation (AF) type, AF duration, and the operating physician. Medication history was also recorded. Laboratory parameters, measured from venous blood samples collected after at least 8 h of fasting within 24 h of admission, included admission blood glucose (ABG), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), creatinine, uric acid, hemoglobin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and thyroid-stimulating hormone. Echocardiographic measures comprised left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), interventricular septal thickness (IVS), left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPW), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Procedural success, defined as complete electrical isolation, was confirmed in all patients.

2.4 Assessment of SHR

SHR was calculated using the formula: SHR = admission fasting blood glucose (mmol/L)/[1.59 × HbA1c (%)−2.59]. To determine the optimal cutoff value of SHR for predicting AF recurrence, we performed a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The optimal cutoff point was defined as the SHR value that maximized the Youden index (J = sensitivity + specificity −1). This analysis yielded an optimal SHR cutoff value of 0.91. Based on this cutoff, the study population was stratified into two groups: a high-SHR group (SHR ≥ 0.91, n = 181) and a low-SHR group (SHR < 0.91, n = 265).

2.5 Follow-up and outcomes

All enrolled patients were actively followed for a minimum of 12 months, with data collection ongoing until September 2025. The primary outcome was the recurrence of atrial fibrillation (AF), defined as any atrial tachyarrhythmia (including AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia) lasting for ≥30 s, as documented on electrocardiographic monitoring after a 3-month blanking period following the ablation procedure. The methodology for detecting AF recurrence was designed to capture both symptomatic and asymptomatic episodes. It consisted of a structured protocol (1) Scheduled Interrogations: All patients underwent systematic rhythm assessment at pre-specified outpatient visits at 3, 6, and 12 months post-ablation. This included a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and a 24 h ambulatory Holter monitor. (2) Symptom-Driven Recordings: Patients were provided with handheld single-lead ECG devices and instructed to record and transmit a tracing whenever they experienced palpitations or other arrhythmia-related symptoms. (3) Adjudication of Events: All recorded electrocardiographic tracings—whether from our institution, external hospitals, or patient-transmitted data—were reviewed and confirmed by two independent cardiologists who were blinded to the patients' SHR group assignment. Any discrepancy was resolved by a third senior electrophysiologist.

Secondary outcomes included other cardiovascular events (such as hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death, and significant procedural complications like cardiac tamponade or pulmonary vein stenosis) and non-cardiovascular events (including stroke, major bleeding, and non-cardiac hospitalization or death).

2.6 Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R software (version 4.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.Given the retrospective nature of this study, cases with any missing data for the analyzed variables were excluded from the final analysis to ensure data integrity. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Based on this assessment, normally distributed data are presented as means ± standard deviations and were compared between the two SHR groups using the independent samples t-test. Non-normally distributed data are presented as medians [interquartile ranges] and were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (percentages) and were compared using the Chi-square test, or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Time-to-event data for atrial fibrillation recurrence were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves. The log-rank test was used to compare recurrence-free survival between the two SHR groups. The association of variables with AF recurrence was quantified using the Cox proportional hazards model. Results are reported as Hazard Ratios (HRs), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Variables showing a univariate association with the outcome at a significance level of P < 0.1 were considered candidates for inclusion in the multivariate Cox model. This relaxed threshold of P < 0.1 is a conventional method to minimize the omission of potential confounding variables from the final model. The final multivariate model was constructed to identify independent factors associated with AF recurrence, adjusting for these candidate variables.

2.7 Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

To assess the consistency and robustness of our primary findings, we conducted pre-specified subgroup and sensitivity analyses. A subgroup analysis was performed based on diabetes status. The presence of an effect modification by diabetes was formally tested by introducing an interaction term (SHR × diabetes status) into the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. A two-sided P value for interaction < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additionally, we performed two sensitivity analyses: first, by repeating the primary analysis after excluding five patients with a history of open-heart surgery to address potential confounding from a profoundly altered atrial substrate; and second, by reclassifying SHR based on tertiles to examine if the results were dependent on the specific binary cut-off value.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics according to atrial fibrillation recurrence Status

The final analysis included 446 patients with atrial fibrillation. Comparative assessment of baseline characteristics between the recurrence (n = 128) and nonrecurrence (n = 318) groups revealed statistically significant differences in several parameters, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Baseline variables | Total | Recurrence-free group | Recurrence group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 446 | (n = 318) | (n = 128) | ||

| Age (years) | 66 (58, 72) | 66 (59, 71) | 67 (58, 72) | 0.996 |

| Female, n (%) | 187 (41.9) | 133 (41.8) | 54 (42.2) | 0.944 |

| BMI | 25.1 (23.2, 27.1) | 25.1 (23.4, 27.4) | 25 (22.5, 26.6) | 0.220 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| CAD | 87 (19.5) | 58 (18.2) | 29 (22.7) | 0.286 |

| Hypertension | 229 (51.3) | 165 (52.4) | 65 (48.9) | 0.718 |

| DM | 171 (38.3) | 111 (34.9) | 60 (46.9) | 0.019 |

| CI | 82 (18.4) | 57 (17.9) | 25 (19.5) | 0.691 |

| COPD | 51 (11.4) | 35 (11) | 16 (12.5) | 0.654 |

| Smoking | 118 (26.5) | 83 (26.1) | 35 (27.3) | 0.787 |

| Alcohol | 302 (67.7) | 208 (65.4) | 98 (76.6) | 0.065 |

| AF type | 0.956 | |||

| Paroxysmal | 203 (45.5) | 145 (45.6) | 58 (45.3) | |

| Persistent | 243 (54.5) | 173 (54.4) | 70 (54.7) | |

| AF duration, months | 18 (12, 36) | 18 (12, 36) | 24 (12, 48) | 0.661 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| HbA1c (%) | 5.9 (5.6, 6.5) | 5.9 (5.6, 6.4) | 6 (5.7, 6.8) | 0.002 |

| ABG (µmol/L) | 5.7 (4.9, 7.2) | 5.4 (4.8, 6.3) | 7.1 (5.6, 8.9) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 136 (125, 148) | 137 (126, 150) | 134 (122, 146) | 0.341 |

| TSH (mg/L) | 2.4 (1.4, 3.7) | 2.4 (1.5, 3.6) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.9) | 0.468 |

| TC(mmol/L) | 4.1 (3.5, 4.7) | 4.1 (3.5, 4.7) | 4.0 (3.4, 4.7) | 0.921 |

| TG(mmol/L) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | 0.423 |

| LDL-C(mmol/L) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.0) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.1) | 2.4 (1.9, 2.9) | 0.741 |

| HDL-C(mmol/L) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 0.745 |

| Creatinine(umol/L) | 72 (61, 84) | 73 (62, 86) | 69 (60, 80) | 0.612 |

| UA(umol/L) | 371 (306, 434) | 359 (290, 432) | 381 (326, 4,527) | 0.041 |

| SHR | 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | <0.001 |

| SHR ≥ 0.91 | 181 (40.6) | 98 (30.8) | 83 (64.8) | <0.001 |

| Medication data | ||||

| ACEI + ARB | 121 (27.1) | 87 (27.4) | 34 (26.6) | 0.864 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 104 (23.3) | 76 (23.9) | 28 (21.9) | 0.997 |

| Beta-blockers | 76 (17) | 56 (17.6) | 20 (15.6) | 0.613 |

| SGL-2 inhibitor | 125 (28) | 98 (30.8) | 27 (21.1) | 0.039 |

| Statins | 212 (47.5) | 150 (47.2) | 62 (48.4) | 0.808 |

| Anticoagulants | 429 (96.2) | 307 (96.5) | 122 (95.3) | 0.734 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 363 (81.4) | 269 (84.6) | 94 (73.4) | 0.006 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEDD (mm) | 47 (44, 51) | 47 (44, 50) | 48 (44, 52) | 0.184 |

| LAD | 41 (36, 46) | 40 (35, 44) | 44 (39, 48) | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 62 (59, 64) | 62(59, 64) | 62(60, 64) | 0.478 |

| IVS | 10(9, 11) | 10(9, 11) | 10(9, 11) | 0.212 |

| LVPW | 9(8, 10) | 9(8, 10) | 9(8, 10) | 0.771 |

Baseline characteristics of patients with atrial fibrillation in the recurrence and non-recurrence groups.

CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; CI, cerebral infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; UA, uric acid; Cr, creatinine; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; IVS, interventricular septal thickness; LVPW, left posterior wall thickness; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; ACEI + ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers; ABG, admission blood glucose; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Patients in the recurrence group showed higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, higher HbA1c, higher admission blood glucose, and higher SHR. The recurrent group had a larger left atrial diameter and higher serum uric acid levels. Regarding drug use, the recurrence group had a lower utilization rate of antiarrhythmic drugs and SGLT-2 inhibitors. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender distribution, other comorbidities, blood lipids, ventricular function parameters, or the use of most cardiovascular drugs (see Table 1 for details).

3.2 Baseline characteristics determined based on the optimal critical value of stress hyperglycemia ratio

Comparative analysis showed that patients with SHR ≥ 0.91 had significantly higher prevalence of diabetes, larger left atrial diameter (LAD) and left ventricular end diastolic diameter (LVEDD), higher uric acid level, and increased statin use. Importantly, the high SHR group had a significantly higher recurrence rate of atrial fibrillation (see Table 2 for details).

Table 2

| Baseline variables | All patients | SHR < 0.91 | SHR ≥ 0.91 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = (446) | N = 265 | N = 181 | ||

| Age (years) | 66 (58, 72) | 67 (59, 73) | 66 (57, 71) | 0.979 |

| Female, n (%) | 187 (49.1) | 115 (43.3) | 72 (39.8) | 0.447 |

| BMI | 24.9 (23.1, 27.2) | 24.9 (23.4, 27.2) | 25.2 (22.9, 21.2) | 0.845 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| CHD | 86 (19.3) | 47 (17.8) | 39 (21.5) | 0.326 |

| Hypertension | 229 (51.3) | 136 (51.3) | 93 (51.4) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes | 171 (38.3) | 76 (28.7) | 95 (52.5) | <0.001 |

| CI | 82 (18.2) | 47 (17.8) | 34 (18.8) | 0.792 |

| COPD | 50 (11.2) | 25 (9.4) | 25 (13.9) | 0.144 |

| Smoking | 118 (26.5) | 63 (23.8) | 55 (30.4) | 0.12 |

| Alcohol | 144 (32.3) | 78 (29.4) | 66 (36.5) | 0.119 |

| AF type | 0.283 | |||

| Paroxysmal | 213 (47.8) | 121 (45.7) | 92 (50.8) | |

| Persistent | 233 (52.5) | 144 (54.3) | 89 (49.2) | |

| AF duration, months | 18 (12, 36) | 18 (12, 36) | 21 (12, 36) | 0.102 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 136 (126, 148) | 136 (126, 148) | 136 (123, 148) | 0.528 |

| TSH (mg/L) | 2.4 (1.5, 3.7) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.0) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.0) | 0.258 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.1 (3.5, 4.7) | 4.1 (3.5, 4.7) | 4.1 (3.5, 4.7) | 0.465 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.7) | 0.091 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.0) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.0) | 2.5 (1.9, 2.9) | 0.401 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.3) | 0.180 |

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 72 (61, 84) | 72 (64, 84) | 71 (61, 84) | 0.065 |

| UA (umol/L) | 371 (306, 434) | 361 (290, 429) | 388 (332, 446) | 0.004 |

| Medication data | ||||

| ACEI + ARB | 121 (27.1) | 66 (24.9) | 55 (30.4) | 0.201 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 104 (23.3) | 66 (24.9) | 38 (21.0) | 0.337 |

| Beta-blockers | 76 (17) | 46 (17.4) | 30 (16.6) | 0.829 |

| SGL-2 | 125 (22.6) | 71 (26.8) | 54 (29.8) | 0.482 |

| Statins | 212 (47.5) | 114 (43.0) | 98 (54.1) | 0.021 |

| Anticoagulants | 438 (98.2) | 263 (99.2) | 175 (96.7) | 0.052 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 363 (81.34) | 217 (81.9) | 146 (80.7) | 0.744 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEDD (mm) | 47 (44, 51) | 47 (44, 50) | 48 (44, 52) | 0.031 |

| LVEF (%) | 62 (60, 64) | 62 (60, 64) | 62 (60, 64) | 0.285 |

| LA | 41(36, 46) | 40(35, 44) | 44(37, 48) | <0.001 |

| AF recurrence | 133(29.8) | 36(13.6) | 97(53.6) | <0.001 |

Baseline characteristics according to the best cutoff value for the stress hyperglycemia ratio.

CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; CI, cerebral infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI, body mass index; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; UA, uric acid; Cr, creatinine; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; IVS, interventricular septal thickness; LVPW, left posterior wall thickness; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; ACEI + ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers; ABG, admission blood glucose; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; AF, atrial fibrillation.

3.3 Independent predictive factors of atrial fibrillation recurrence

After adjusting for potential confounding factors, multivariate Cox regression analysis identified several factors independently associated with the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence. Elevated SHR (≥0.91) is the strongest predictor and significantly correlated with recurrence (adjusted HR = 3.379, 95% CI: 2.272–5.052). A history of alcohol consumption and non use of antiarrhythmic drugs are also significantly associated with a higher risk of recurrence. In continuous variables, higher levels of HbA1c, LAD, and uric acid are independently associated with increased risk. In contrast, the use of SGLT-2 inhibitors is significantly associated with a reduced risk of recurrence. It is worth noting that the history of diabetes is important in univariate analysis, but it is not an independent predictor after multivariate adjustment (see Table 3 for detailed data).

Table 3

| Characteristics | HR(95% CI) Univariate analysis | P value Univariate analysis | HR(95% CI) Multivariate analysis | P value Multivariate analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 0.943 (0.664–1.340) | 0.745 | ||

| Age | 0.996 (0.980–1.014) | 0.682 | ||

| Alcohol | ||||

| NO | Reference | Reference | ||

| YES | 1.381 (0.933–2.044) | 0.060 | 1.846 (1.213–2.811) | 0.004 |

| Statins | ||||

| YES | Reference | |||

| NO | 0.943 (0.667–1.334) | 0.741 | ||

| Antiarrhythmics | ||||

| YES | Reference | Reference | ||

| NO | 1.698 (1.147–2.513) | 0.008 | 1.577 (1.055–2.358) | 0.026 |

| AF type | ||||

| Persistent | Reference | |||

| Paroxysmal | 0.982 (0.694–1.390) | 0.919 | ||

| AF duration time | 1.036 (0.975–1.100) | 0.251 | ||

| SGL-2 inhibitor | ||||

| NO | Reference | |||

| YES | 0.694 (0.454–1.062) | 0.093 | 0.598 (0.372–0.961) | 0.034 |

| SHR ≥ 0.91 | ||||

| NO | Reference | Reference | ||

| YES | 3.827 (2.657–5.511 | < 0.001 | 3.379 (2.272–5.025) | < 0.001 |

| LAD(mm) | 1.065 (1.038–1.094) | < 0.001 | 1.034 (1.006–1.062) | 0.018 |

| LVEDD(mm) | 1.026 (0.998–1.054) | 0.069 | 1.001 (0.975–1.029) | 0.916 |

| Operators | 0.962 (0.863–1.072) | 0.480 | ||

| HbA1c (%) | 1.539 (1.320–1.795) | < 0.001 | 1.454 (1.151–1.837) | 0.002 |

| BMI | 0.967 (0.918–1.018) | 0.203 | ||

| Hb(g/dL) | 0.996 (0.986–1.003) | 0.120 | ||

| UA(umol/L) | 1.003 (1.002–1.005) | 0.017 | 1.004 (1.002–1.005) | < 0.001 |

| TSH (mg/L) | 1.0094 (0.974–1.035) | 0.798 | ||

| COPD | ||||

| YES | Reference | |||

| NO | 0.706 (0.439–1.137) | 0.152 | ||

| Anticoagulants | ||||

| YES | Reference | |||

| NO | 1.405 (0.618–3.194) | 0.417 | ||

| DM | ||||

| NO | Reference | Reference | ||

| YES | 1.689 (1.193–2.392) | 0.003 | 0.790 (0.459–1.3460) | 0.395 |

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for clinical events.

DM, diabetes mellitus; BMI, body mass index; UA, uric acid; Cr, creatinine; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; AF, atrial fibrillation; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Hb, hemoglobin.

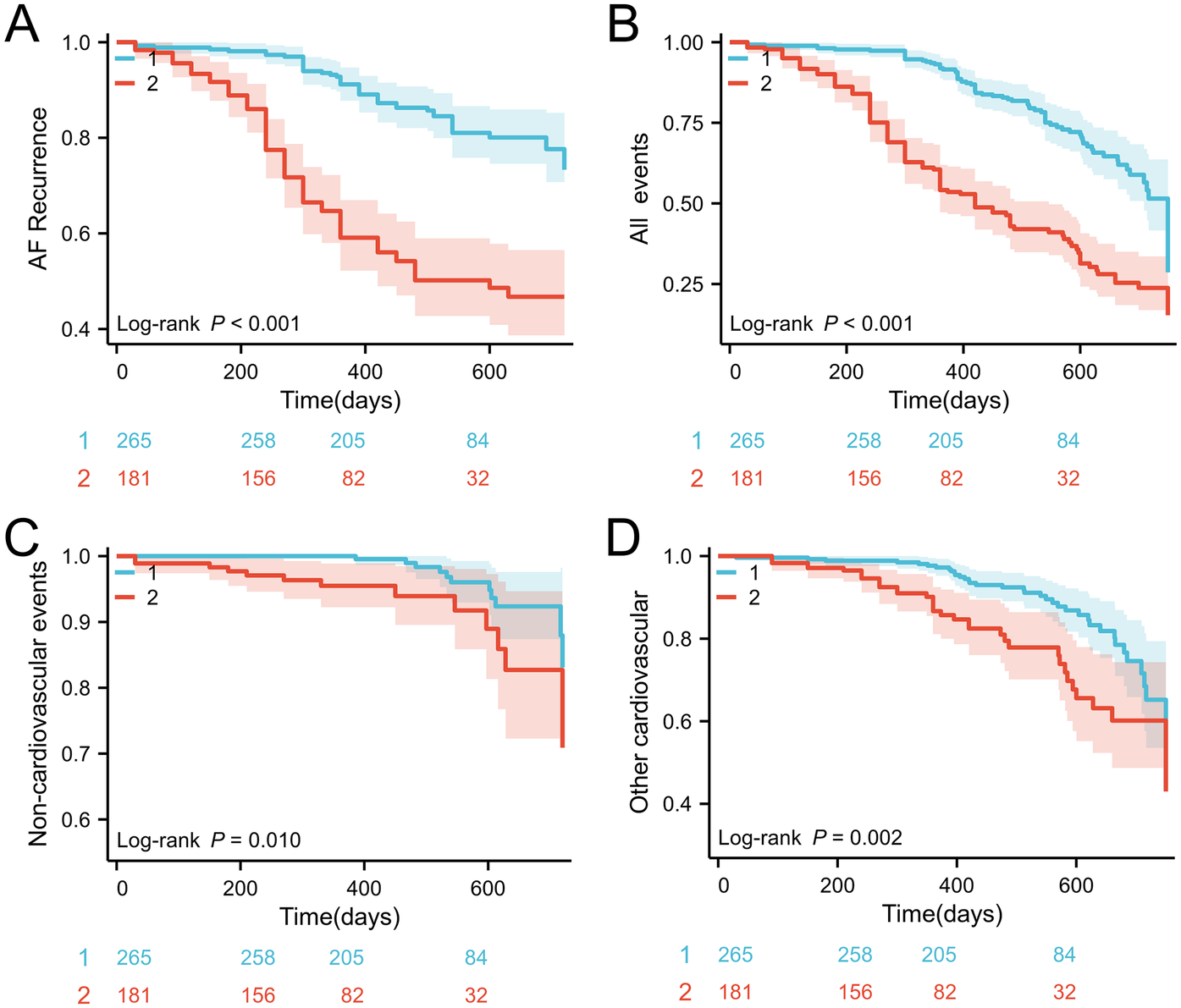

3.4 The correlation between stress hyperglycemia ratio and clinical outcomes

Consistent with preliminary analysis, the cumulative incidence of composite endpoints in the high SHR group was significantly higher, mainly due to atrial fibrillation recurrence. Kaplan Meier analysis confirmed this association, which showed that patients with SHR ≥ 0.91 had a significantly reduced probability of recurrence free survival (log rank P < 0.001); Figure 1A). Similarly, evaluations of secondary endpoints (including cardiovascular, non cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality) consistently showed poorer prognosis in the high SHR group (Figures 1B–D).

Figure 1

(A) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for AF recurrence events stratified by the SHR cutoff; (B) incidence of all events; (C) incidence of noncardiovascular mortality; (D) incidence of cardiovascular mortality. SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; AF, atrial fibrillation.

3.5 The predictive value of stress hyperglycemia ratio for atrial fibrillation recurrence

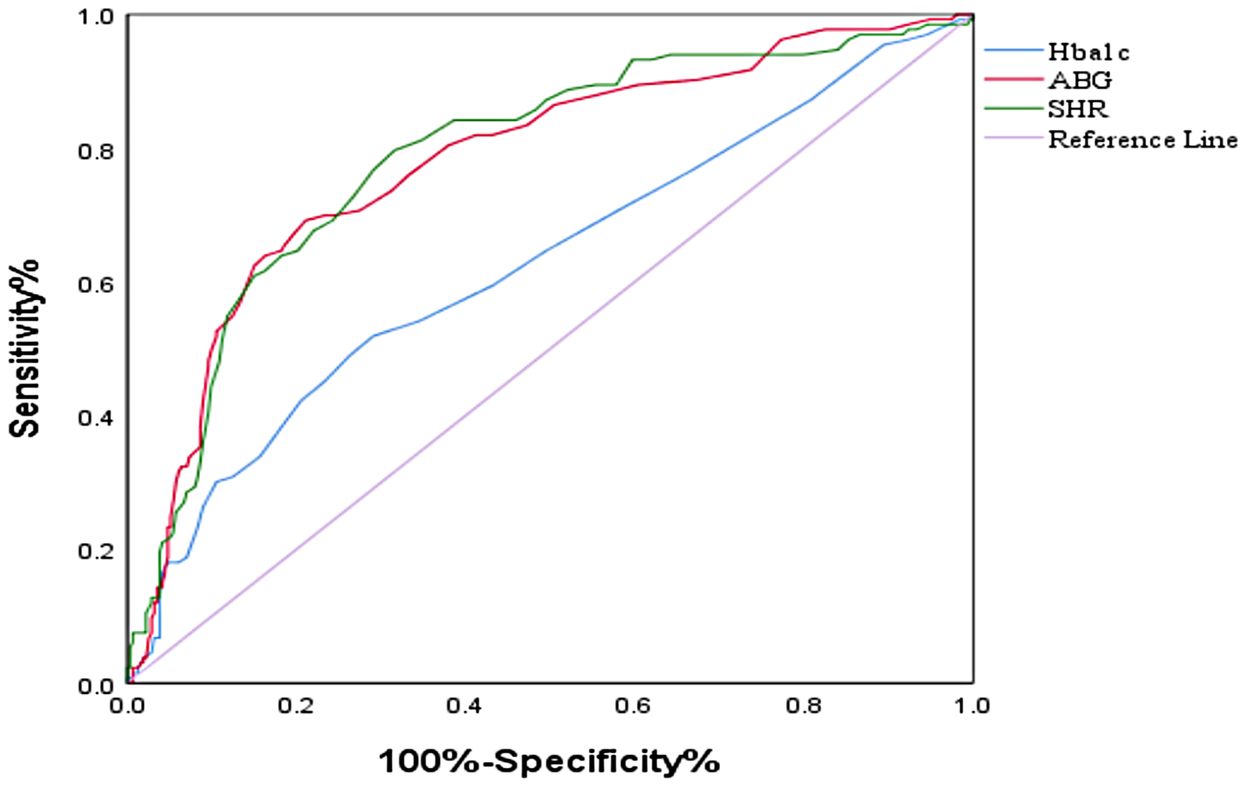

ROC curve analysis is used to evaluate the diagnostic performance of HbA1c, ABG, and SHR in predicting outcomes. SHR has the best predictive performance, with specific AUC(0.79, 95% CI: 0.74–0.84) values shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

ROC curves of the SHR, HbA1c level and ABG for the prediction of AF recurrence. ROC, receiver operating curve; SHR, stress–hyperglycemia ratio; ABG, admission blood glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin.

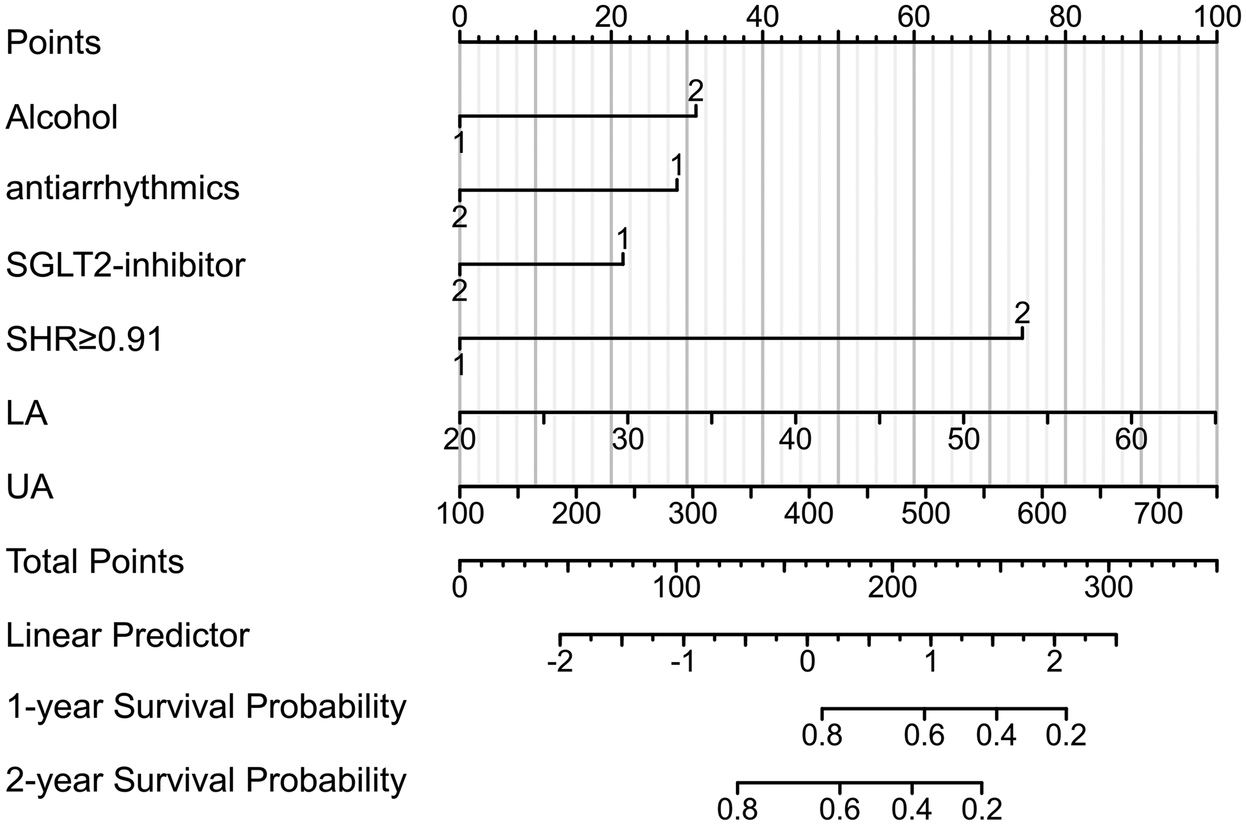

3.6 Prediction model for atrial fibrillation recurrence

Based on multivariate Cox regression analysis, a prognostic column chart was constructed to predict the 1-year and 2-year survival probabilities (Figure 3). The column chart includes six independent predictive factors: alcohol consumption; SHR; UA; LAD; And the use of antiarrhythmic drugs and SGL-2 inhibitors.

Figure 3

Nomogram of recurrence after RFCA for AF. UA, uric acid; LA, left atrial diameter; SHR, stress–hyperglycemia ratio.

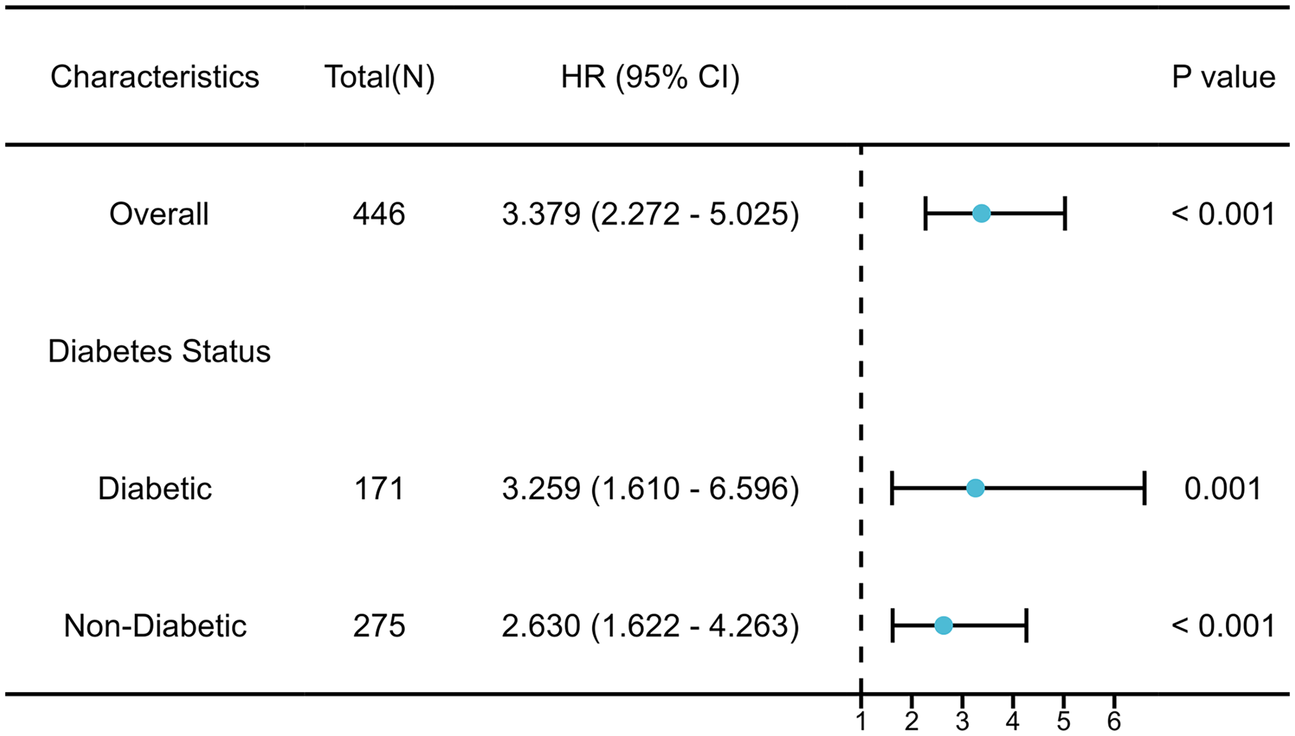

3.7 Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Formal tests of the interaction showed that diabetes status had no significant effect (interaction P = 0.432). As shown in the forest diagram (Figure 4), the elevation of SHR is consistent with the recurrence of atrial fibrillation in both diabetes patients and non diabetes patients. In all pre specified sensitivity analyses, the main finding remains robust. After excluding patients with a history of open heart surgery, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of SHR remained significant (adjusted HR = 3.451, 95% CI: 2.311–5.154). In addition, A significant graded association was observed across SHR tertiles. In the multivariable model, the highest SHR tertile was associated with a more than three-fold increased hazard of recurrence relative to the lowest tertile (adjusted HR = 3.38, 95% CI: 2.27–5.05). The detailed results of sensitivity analysis are shown in Supplementary Tables S1, S2.

Figure 4

Subgroup analysis of the association between SHR and AF recurrence.

4 Discussion

This study revealed a significant association between stress-induced hyperglycemia (SHR) and atrial fibrillation recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA). This discovery has significant clinical implications as it elucidates for the first time that acute changes in metabolic status prior to ablation may have far-reaching effects on long-term surgical outcomes. In multivariate analysis, SHR ≥ 0.91 was significantly associated with recurrence risk, and this association remained robust in various sensitivity analyses, indicating that SHR may represent a novel and clinically feasible risk stratification tool. Compared with traditional single blood glucose or glycated hemoglobin measurements, SHR provides a more comprehensive assessment of patients' metabolic status by integrating acute and chronic blood glucose indicators, thereby enhancing the risk assessment ability for patients with complex arrhythmias. This discovery opens up new avenues for individualized treatment of atrial fibrillation, particularly for optimizing treatment strategies for patients with metabolic abnormalities.

Our findings provide a meaningful comparison and supplement to previous studies on the relationship between metabolic disorders and the prognosis of atrial fibrillation. Mohanty et al. found in a study with an average follow-up of 21.7 months that patients with metabolic syndrome had a significantly higher recurrence rate after catheter ablation compared to patients without metabolic syndrome (17). In contrast, Choi et al. showed that although diabetes is associated with the recurrence of atrial fibrillation, this association is not independent after adjusting for other cardiovascular risk factors (18). However, these studies mainly focus on chronic metabolic conditions and overlook the potential impact of acute metabolic changes. Our research fills this cognitive gap and demonstrates that stress-induced hyperglycemia—a transient but pathophysiological phenomenon driven by neuroendocrine and inflammatory activation—may be an important determinant of atrial fibrillation recurrence (19–22). SHR provides a more accurate assessment of metabolic stress by simultaneously considering acute and chronic blood glucose control status, which has been validated in prognostic studies of other cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure and acute myocardial infarction (23–25). In our queue, the critical value of SHR 0.91 effectively distinguished patients with different risk levels, and the high SHR group showed a significant association with recurrence, indicating that SHR may become an effective tool for identifying high-risk patients who require more proactive preoperative optimization (26).

The potential pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the association between stress-induced hyperglycemia and atrial fibrillation recurrence deserve further exploration. Acute hyperglycemia may promote atrial electrophysiological remodeling through various pathways: firstly, the hyperglycemic environment enhances oxidative stress, leading to an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which in turn damages the ion channel function of myocardial cells (27, 28); Secondly, the systemic inflammatory response induced by hyperglycemia may activate a cascade of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to atrial fibrosis and abnormal electrical conduction (29–31); Thirdly, endothelial dysfunction and microvascular injury may lead to inadequate perfusion of atrial tissue, increasing the risk of local ischemia (32). These mechanisms working together may reduce the effectiveness of ablation and promote the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. It is worth noting that our study found that the association between SHR and recurrence of atrial fibrillation is consistent in both diabetes and non diabetes patients, which indicates that stress hyperglycemia may affect the prognosis of atrial fibrillation through general pathophysiological mechanisms, not limited to specific patient groups. This finding is consistent with the recent meta-analysis results, emphasizing the practicability of robust risk predictors in a wide range of people, and also providing important enlightenment for clinicians: even in non diabetes patients, the optimization of preoperative metabolic status may improve the prognosis after ablation (33).

Our research findings have significant clinical implications for atrial fibrillation management strategies. Firstly, as a simple and easily accessible biomarker, SHR can be seamlessly integrated into existing preoperative assessment processes to help identify high-risk patients. For patients with elevated SHR, clinical doctors may consider adopting more proactive preoperative metabolic optimization strategies, such as strengthening blood glucose control, anti-inflammatory treatment, or delaying surgery until metabolic status stabilizes. Secondly, our findings support the comprehensive cardiovascular risk factor intervention strategy confirmed in the ARREST-AF trial, which shows that preoperative adjustment of risk factors can significantly reduce the recurrence rate of atrial fibrillation after ablation. Third, we observed that the SGLT2 inhibitor use rate was low in patients in the relapse group, which suggests that specific anti diabetes drugs may have a cardioprotective effect beyond blood glucose control. SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to have anti-inflammatory, anti oxidative stress, and improved myocardial energy metabolism effects (34, 35), which may be particularly beneficial for patients with atrial fibrillation. Therefore, SGLT2 inhibitors may be the first choice for patients with atrial fibrillation complicated with diabetes, especially in patients who plan to receive catheter ablation. Finally, our findings emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, as collaboration between endocrinologists and arrhythmia specialists may optimize the management of such complex patients.

Our research clearly establishes the independent predictive value of the SHR for prognosis after RFCA in humans for the first time, filling a knowledge gap in this field. This study has several limitations. Its retrospective, single-center design inherently limits causal inference. The assessment of left atrial size relied on linear diameter rather than the more robust volume index (LAVI), which may have reduced the sensitivity of our atrial remodeling assessment. Finally, despite multivariate adjustments, the possibility of unmeasured confounding cannot be entirely excluded. Nevertheless, the relatively large sample size, standardized follow-up, and advanced statistical modeling are key strengths of our analysis.

5 Conclusion

In summary, SHR is a reliable and readily available biomarker that is significantly associated with atrial fibrillation recurrence after RFCA. Its predictive value is consistent across diabetic and non-diabetic subgroups, enhancing its potential for broad clinical application. Integrating SHR into pre-procedural risk assessment could facilitate more personalized patient management and ultimately improve long-term outcomes after catheter ablation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Second Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ML: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft. NZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation. ZW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. TF: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Supervision, Investigation. XW: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XY: Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to LiJun Liu for statistical analysis support and to QingWen Ren for providing critical feedback on the manuscript. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. We wish to declare that an AI-powered tool (deepseek) was used solely for language polishing of the English text in this manuscript. The core scientific content, data, and conclusions remain entirely our own. This use is in accordance with the journal's policy on AI-assisted tools.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1699551/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- CI

cerebral infarction

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- BMI

body mass index

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin A1c

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglyceride

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- UA

uric acid

- Cr

creatinine

- LAD

left atrial diameter

- LVEDD

left ventricular end-diastolic diameter

- IVS

interventricular septal thickness

- LVPW

left posterior wall thickness

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- SHR

stress hyperglycemia ratio

- ACEI + ARB

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers

- ABG

admission blood glucose

- TSH

thyroid stimulating hormone

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- RFCA

radiofrequency catheter ablation

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

area under the curve

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- eAG

estimated average glucose

- ABG

admission blood glucose

- CRYO

cryoballoon ablation

- AAD

antiarrhythmic drug

- ACT

activatedclottingtime

- PVI

pulmonary vein isolation

- CARTO

three-dimensional electroanatomical mapping system

- non-PV

non-pulmonary vein

- CTI

cavotricuspid isthmus

- AT

atrial tachycardias

- CIs

confidence intervals

- HRs

Hazard Ratios.

References

1.

Manolis AA Manolis TA Manolis AS . Current strategies for atrial fibrillation prevention and management: taming the commonest cardiac arrhythmia. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. (2025) 23(1):31. 10.2174/0115701611317504240910113003

2.

Zhang J Johnsen SP Guo Y Lip GYH . Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: geographic/ecological risk factors, age, sex, genetics. Card Electrophysiol Clin. (2021) 13(1):1. 10.1016/j.ccep.2020.10.010

3.

Dai H Zhang Q Much AA Maor E Segev A Beinart R et al Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, mortality, and risk factors for atrial fibrillation, 1990–2017: results from the global burden of disease study 2017. Eur Heart J. (2021) 7(6):574–82. 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa061

4.

Hernández-Angeles C Castelo-Branco C . Cardiovascular risk in climacteric women: focus on diet. Climacteric. (2016) 19(3):215–21. 10.3109/13697137.2016.1173025

5.

Shah AJ Haissaguerre M Hocini M Jais P . Comparison of rhythm restoration strategies in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. (2010) 8(7):903–6. 10.1586/erc.10.66

6.

Yang X Lin M Zhang Y Wang J Zhong J . Radiofrequency catheter ablation for re-do procedure after single-shot pulmonary vein isolation with pulsed field ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: case report. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 11:1376229. 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1376229

7.

Packer DL Mark DB Robb RA Monahan KH Bahnson TD Poole JE et al Effect of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality, stroke, bleeding, and cardiac arrest among patients with atrial fibrillation. Jama. (2019) 321(13):1261. 10.1001/jama.2019.0693

8.

Kishima H Mine T Fukuhara E Kitagaki R Asakura M Ishihara M . Efficacy of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on outcomes after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Clin Electrophysiol. (2022) 8(11):1393–404. 10.1016/j.jacep.2022.08.004

9.

Wang Z He H Xie Y Li J Luo F Sun Z et al Non-insulin-based insulin resistance indexes in predicting atrial fibrillation recurrence following ablation: a retrospective study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2024) 23(1):87. 10.1186/s12933-024-02158-6

10.

Ariyaratnam JP Middeldorp M Thomas G Noubiap JJ Lau D Sanders P . Risk factor management before and after atrial fibrillation ablation. Card Electrophysiol Clin. (2020) 12(2):141–54. 10.1016/j.ccep.2020.02.009

11.

Cheng S Shen H Han Y Han S Lu Y . Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio index and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with atrial fibrillation: a retrospective study using the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2024) 23(1):363. 10.1186/s12933-024-02462-1

12.

Tan M Zhang Y Zhu S Wu S Zhang P Gao M . The prognostic significance of stress hyperglycemia ratio in evaluating all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk among individuals across stages 0–3 of cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic syndrome: evidence from two cohort studies. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2025) 24(1):137. 10.1186/s12933-025-02689-6

13.

Li L Zhao M Zhang Z Zhou L Zhang Z Xiong Y et al Prognostic significance of the stress hyperglycemia ratio in critically ill patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2023) 22(1):275. 10.1186/s12933-023-02005-0

14.

Roberts GW Quinn SJ Valentine N Alhawassi T O'Dea H Stranks SN et al Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2015) 100(12):4490–7. 10.1210/jc.2015-2660

15.

Liu J Zhou Y Huang H Liu R Kang Y Zhu T et al Impact of stress hyperglycemia ratio on mortality in patients with critical acute myocardial infarction: insight from American MIMIC-IV and the Chinese CIN-II study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2023) 22(1):281. 10.1186/s12933-023-02012-1

16.

Ding L Zhang H Dai C Zhang A Yu F Mi L et al The prognostic value of the stress hyperglycemia ratio for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes: insights from NHANES 2005–2018. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2024) 23(1):84. 10.1186/s12933-024-02172-8

17.

Mohanty S Mohanty P Di Biase L Bai R Pump A Santangeli P et al Impact of metabolic syndrome on procedural outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2012) 59(14):1295–301. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.051

18.

Choi SH Yu HT Kim D Park J Kim T Uhm J et al Late recurrence of atrial fibrillation 5 years after catheter ablation: predictors and outcome. Europace. (2023) 25(5):euad113. 10.1093/europace/euad113

19.

Bateman RM Sharpe MD Jagger JE Ellis CG Solé-Violán J López-Rodríguez M et al 36th international symposium on intensive care and emergency medicine: Brussels, Belgium. 15–18 march 2016. Crit Care (London, England). (2016) 20(Suppl 2):94. 10.1186/s13054-016-1208-6

20.

Zhou F Yu T Du R Fan G Liu Y Liu Z et al Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet (British Edition). (2020) 395(10229):1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3

21.

Lei M Li Y Cheng L Tang N Song J Song M et al Stress hyperglycemia ratio as a biomarker for early mortality risk stratification in cardiovascular disease: a propensity-matched analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2025) 24(1):286. 10.1186/s12933-025-02812-7

22.

Li X Guo L Zhou Y Yuan C Yin Y . Stress hyperglycemia ratio as an important predictive indicator for severe disturbance of consciousness and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with cerebral infarction: a retrospective study using the MIMIC-IV database. Eur J Med Res. (2025) 30(1):53. 10.1186/s40001-025-02309-9

23.

Xie Y Chen H Wang Z He H Xu Y Liu L et al Impact of stress hyperglycemia ratio on long-term clinical outcomes in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Angiology. (2025). 10.1177/00033197251333216

24.

Pei Y Ma Y Xiang Y Zhang G Feng Y Li W et al Stress hyperglycemia ratio and machine learning model for prediction of all-cause mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2025) 24(1):77. 10.1186/s12933-025-02644-5

25.

Mohammed A Luo Y Wang K Su Y Liu L Yin G et al Stress hyperglycemia ratio as a prognostic indicator for long-term adverse outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2024) 23(1):67. 10.1186/s12933-024-02157-7

26.

Kamioka M Narita K Watanabe T Watanabe H Makimoto H Okuyama T et al Hypertension and atrial fibrillation: the clinical impact of hypertension on perioperative outcomes of atrial fibrillation ablation and its optimal control for the prevention of recurrence. Hypertens Res. (2024) 47(10):2800–10. 10.1038/s41440-024-01796-3

27.

Sharma D Singh JN Sharma SS . Effects of 4-phenyl butyric acid on high glucose-induced alterations in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neurosci Lett. (2016) 635:83–9. 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.10.038

28.

Thilo F Lee M Xia S Zakrzewicz A Tepel M . High glucose modifies transient receptor potential canonical type 6 channels via increased oxidative stress and syndecan-4 in human podocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2014) 450(1):312–7. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.116

29.

Wust IC . Viral interactions with host factors (TIM-1, TAM -receptors, Glut-1) are related to the disruption of glucose and ascorbate transport and homeostasis, causing the haemorrhagic manifestations of viral haemorrhagic fevers. F1000Res. (2024) 12:518. 10.12688/f1000research.134121.6

30.

Tang H Lu K Wang Y Shi Y Ma W Chen X et al Analyses of lncRNA and mRNA profiles in recurrent atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation. Eur J Med Res. (2024) 29(1):244. 10.1186/s40001-024-01799-3

31.

Zhan G Wang X Wang X Li J Tang Y Bi H et al Dapagliflozin: a sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, attenuates angiotensin II-induced atrial fibrillation by regulating atrial electrical and structural remodeling. Eur J Pharmacol. (2024) 978:176712. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.176712

32.

Matsuda Y Masuda M Uematsu H Sugino A Ooka H Kudo S et al Impact of diabetes mellitus and poor glycemic control on the prevalence of left atrial low-voltage areas and rhythm outcome in patients with atrial fibrillation ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2024) 35(4):775–84. 10.1111/jce.16219

33.

Zhao H Liu M Chen Z Mei K Yu P Xie L . Dose-response analysis between hemoglobin A1c and risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with and without known diabetes. PLoS One. (2020) 15(2):e227262. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227262

34.

Banerjee M Pal R Nair K Mukhopadhyay S . SGLT2 inhibitors and cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian Heart J. (2023) 75(2):122–7. 10.1016/j.ihj.2023.03.003

35.

Li J Yu Y Sun Y Yu B Tan X Wang B et al SGLT2 inhibition, circulating metabolites, and atrial fibrillation: a mendelian randomization study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2023) 22(1):278. 10.1186/s12933-023-02019-8

Summary

Keywords

stress–hyperglycemia ratio, atrial fibrillation, radiofrequency catheterablation, atrial fibrillation recurrence, prognostic biomarker, nomogram

Citation

Li M-l, Zhu N-J, Wang Z, Fan T-t, Wang X-c and Yang X (2025) Relationship between the stress–hyperglycemia ratio and atrial fibrillation recurrence risk after radiofrequency catheter ablation: a retrospective study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1699551. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1699551

Received

05 September 2025

Revised

16 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

02 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Tatsuya Sato, Sapporo Medical University, Japan

Reviewed by

Zeming Zhou, Capital Medical University, China

Aykun Hakgor, Istanbul Medipol University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li, Zhu, Wang, Fan, Wang and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Xun Yang yxcardio110@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.