- Department of Cardiology, Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) accounts for more than half of all heart failure (HF) cases, with its prevalence steadily rising due to population aging, obesity, and the prevalence of metabolic diseases. Obesity, a core risk factor for HFpEF, leads to a distinct clinical phenotype and significantly worsens patient prognosis. Given the limitations of body mass index (BMI) in assessing fat distribution, epicardial adipose tissue (EAT)—a metabolically active fat depot closely adjacent to the myocardium—has emerged as a crucial anatomical and functional bridge linking obesity to HFpEF. Compared to BMI, EAT volume demonstrates a stronger predictive value for diastolic dysfunction and adverse clinical outcomes, highlighting its clinical significance. This review outlines the multifaceted mechanisms through which EAT contributes to HFpEF pathogenesis, including mechanical constraint limiting ventricular diastole, lipid infiltration causing myocardial metabolic disorders, pro-inflammatory factor paracrine secretion inducing fibrosis, microvascular dysfunction, arrhythmogenic effects, and protein modification disorders. Targeting EAT has shown promise in reducing its volume, improving inflammatory status, and enhancing cardiac function. As a pathogenic and therapeutic nexus between obesity and HFpEF, further elucidation of EAT-related mechanisms may facilitate precision diagnosis and intervention for this growing population.

1 Introduction

HF represents a growing global public health concern, with HFpEF accounting for more than half of all HF cases (1). Its prevalence continues to rise in parallel with population aging and the increasing burden of chronic comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension (2–5). Due to heterogeneous definitions and complex pathophysiological features, HFpEF continues to pose significant diagnostic challenges in clinical practice. To date, few pharmacologic interventions have demonstrated a clear prognostic benefit in HFpEF. Current therapies mainly focus on relieving congestion through diuretics and reducing the risk of hospitalization or cardiovascular death using sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) (6). Recently, a paradigm shift has emerged advocating for the classification of HFpEF into distinct phenotypes based on pathophysiological traits, which may provide a more personalized framework for therapeutic development (7).

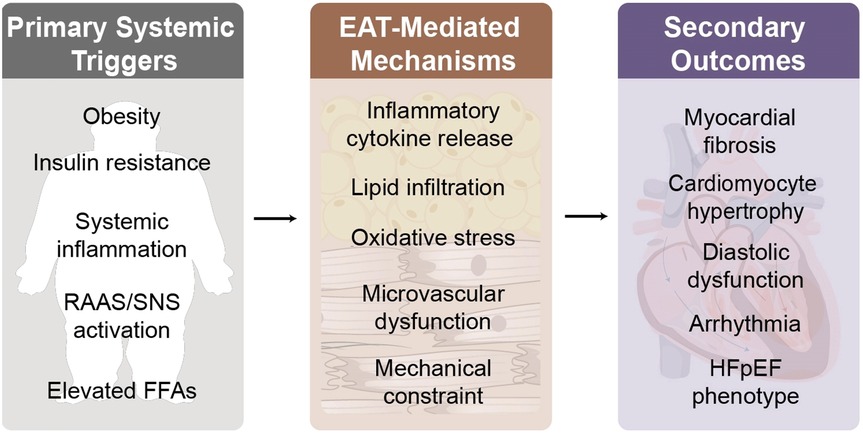

Figure 1. Obesity drives the pathogenesis of HFpEF through multiple interacting pathways. EAT and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) impairs cardiac function via structural remodeling, inflammation, neurohormonal dysregulation, and metabolic imbalance. Structurally, increased blood volume and myocardial wall stress contribute to left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and impaired diastolic relaxation, while right ventricular (RV) dilation and pericardial constraint enhance interventricular dependence. Inflammatory pathways involve adipose-derived cytokines that promote immune cell infiltration and collagen deposition, driving myocardial fibrosis. Metabolically, fatty acid (FA) overload and mitochondrial dysfunction lead to an energy crisis and impaired myocardial relaxation. Neurohormonal activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) further increases vascular resistance and endothelial dysfunction. These interdependent mechanisms collectively contribute to hallmark HFpEF manifestations, including reduced exercise capacity, pulmonary congestion, and decreased left ventricular (LV) compliance. FFA, free fatty acids; ECM, extracellular matrix.

Obesity is recognized as a major contributing factor to HFpEF and defines a distinct clinical subtype, a specific obesity-related HFpEF phenotype has been increasingly characterized (7). However, the conventional use of body mass index (BMI) as an obesity metric has proven insufficient in capturing adiposity distribution or guiding risk stratification in this population, underscoring the need for alternative assessment tools. In this context, EAT has garnered significant interest due to its close anatomical proximity to the heart and its active metabolic and endocrine properties. Expansion of EAT has emerged as a common pathological feature among HFpEF patients. Nevertheless, the precise molecular and physiological mechanisms linking EAT to HFpEF progression remain incompletely understood. This review aims to summarize the current understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying obesity-related HFpEF, with a specific focus on the functional relevance of EAT in disease development and progression.

2 HFpEF and obesity

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 890 million individuals globally meet the criteria for obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²), with a notable trend toward earlier onset in younger populations (8, 9). Compared with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), HFpEF exhibits a stronger association with obesity (10). As the severity of obesity increases, both heart failure–related and all-cause mortality risks rise accordingly (7, 11).

Diagnosing HFpEF is more complex than other heart failure subtypes. To address this, the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology recommends confirming HFpEF using a composite scoring system that incorporates echocardiographic parameters (e.g., E/e′ ratio and left atrial volume) as well as plasma B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels (12, 13). However, because left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is affected by preload, afterload, and rhythm-dependent variability, the actual prevalence of HFpEF may be substantially underestimated (14).

This diagnostic challenge is further amplified in the obesity-related HFpEF phenotype. Obese patients tend to exhibit lower circulating BNP concentrations, often falling below conventional diagnostic thresholds. Moreover, standard Doppler indices such as the E/e′ ratio may underestimate volume overload in this population, leading to underdiagnosis in clinical practice (7, 15–17). These limitations highlight the urgent need for a multidimensional diagnostic framework. Such a framework should integrate biomarkers, imaging features, and metabolic parameters while accounting for obesity-specific pathophysiological mechanisms to enable earlier detection and precision management.

3 Hemodynamic and cellular mechanisms in obesity-related HFpEF

3.1 Cardiac remodeling and hemodynamic overload

Left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction is a central feature of HFpEF pathophysiology (18). In HFpEF, mechanical alterations in sarcomere units, extracellular matrix (ECM), ventricular geometry, and pericardial compliance lead to impaired early diastolic relaxation, resulting in elevated left atrial and left ventricular end-diastolic pressures. Concurrently, increased wall stress induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) (19, 20). Chronically elevated LV pressures can provoke secondary pulmonary hypertension and atrial remodeling, thereby worsening RV dysfunction and promoting atrial fibrillation (AF). Right-sided dilation and overall cardiac enlargement contribute to pericardial constraint and augmented ventricular interdependence. These changes further raise left ventricular filling pressures (7).

Obesity is commonly associated with increased total blood volume and cardiac output. This intravascular volume expansion elevates pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), exacerbates RV enlargement, and increases total cardiac volume (7). These hemodynamic alterations impose sustained cardiac loading conditions that promote HFpEF progression.

3.2 Inflammation and lipid infiltration

Obesity is characterized as a state of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation. Adipose tissue expansion promotes inflammatory cascades within HFpEF through paracrine and immune–cardiomyocyte crosstalk. This process leads to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, reduced nitric oxide bioavailability, ECM remodeling, and myocardial dysfunction (21, 22). Endomyocardial biopsies from HFpEF patients show enhanced macrophage and neutrophil infiltration, with elevated levels of inflammatory markers including CD3, CD11a, CD45, and the adhesion molecule VCAM1 (23). Circulating inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and its receptor (TNFR), interleukins IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and CD95 are also elevated (24).

Lipid deposition is a fundamental contributor to cardiac pathophysiology in obesity (25, 26), and fibrosis, a hallmark of cardiac remodeling, may arise in part from increased circulating FFAs due to excessive lipolysis. These FFAs may infiltrate the cardiac ECM, which consists of type I and III fibrillar collagen, as well as non-fibrillar proteins such as fibronectin, decorin, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans. Alterations in collagen content, cross-linking, and stiffness significantly influence ECM mechanical properties, playing a key role in myocardial remodeling and diastolic dysfunction (27–30). Obesity contributes to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, lipid infiltration into ECM, and epicardial and thoracic wall fat accumulation exacerbate ventricular interdependence. Combined with plasma volume overload and heightened vasoconstriction, these factors accelerate HFpEF progression (7, 31).

3.3 Cellular function and cardiac metabolism

Obesity also affects cellular activity. In obesity-related HFpEF patients, myocardial cell calcium sensitivity was significantly reduced in myocardial biopsies taken from the right ventricular septal endocardium, and sarcomere dysfunction correlated directly with adiposity estimated by BMI (32). Preclinical data further indicate that mitochondrial autophagy is impaired in HFpEF mice compared to obese controls (33). Under normal circumstances, approximately 70%–90% of cardiac ATP is derived from FFA oxidation. In the context of obesity, adipose tissue exhibits a reduced capacity for triglyceride storage, leading to elevated concentrations of circulating free fatty acids (34). The resultant oversupply of fatty acids enhances their myocardial uptake, ultimately contributing to cardiac steatosis (35, 36). Excess FFAs entering cardiomyocytes trigger metabolic reprogramming. Thus, upregulation of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) compensates for this by increasing fatty acid oxidation. However, HFpEF hearts display reduced glucose uptake, increased FA uptake, and diminished ketone oxidation. Compared with HFrEF, HFpEF exhibits lower metabolic flexibility in substrate utilization (37, 38).

This has also been validated in basic experimental models. In a murine model of HFpEF induced by obesity and hypertension, the expression of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase (MCD), an indirect regulator of fatty acid metabolism, was significantly upregulated. Elevated MCD activity reduces intracellular malonyl-CoA levels, thereby promoting fatty acid uptake and enhancing β-oxidation. Compared with control hearts, HFpEF hearts exhibited a marked downregulation of β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1. This enzyme is key in ketone body oxidation. In parallel, the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A was decreased, indicating impaired mitochondrial function and disrupted cardiac energy metabolism (37).

3.4 Neurohormonal activation

Multiple cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities associated with HFpEF. These include hypertension, cardiomyopathy, and diabetes, which are linked to enhanced RAAS activity and autonomic imbalance. This autonomic imbalance is characterized by increased sympathetic drive and reduced vagal tone (39). In HFpEF, both the endothelin and adrenomedullin pathways are upregulated. Resting and exercise-induced elevations in plasma C-terminal pro-endothelin-1 and mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin levels have been associated with impaired pulmonary hemodynamics, reduced RV reserve, diminished cardiac output, and worsened exercise capacity (40). In contrast to HFrEF, most neurohormonal modulation therapies have failed to yield consistent benefits in HFpEF clinical trials (41).

The aforementioned mechanism is illustrated in Figure 1.

4 Epicardial adipose tissue

Recent studies have recognized the distinct impact of obesity on HFpEF. BMI remains the most widely used indicator for obesity, but it is influenced by skeletal muscle mass, which is regulated by multiple factors. Compared to BMI, measures of central obesity such as waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, or waist-to-height ratio are better predictors of systemic inflammation, left ventricular hypertrophy, and diastolic filling abnormalities (42). The PARAGON-HF trial demonstrated that while only approximately half of HFpEF patients are classified as obese by BMI, nearly all exhibited central obesity, also, EAT volume predicts diastolic dysfunction more accurately than BMI (43).

Adipose tissue is divided into subcutaneous adipose tissue and visceral adipose tissue. EAT, derived from the embryonic mesoderm, is a unique visceral fat depot located between the myocardium and the visceral layer of the epicardium, covering approximately 80% of the heart's surface and accounting for about 20% of its mass (44). EAT is widely distributed around the atrioventricular grooves, interventricular sulcus, coronary arteries, atria, right ventricular free wall, and LV apex. Importantly, there is no anatomical barrier between EAT and the myocardium, and they share the same coronary microcirculation, allowing EAT to exert direct influence on myocardial metabolism and vascular function (45, 46). At the cellular level, EAT is predominantly composed of adipocytes, but it also contains nerve cells, inflammatory cells (primarily macrophages and mast cells), stromal cells, vascular cells, and immune cells (35, 45). While EAT is primarily white adipose tissue, it also exhibits features of brown and beige adipose tissue (47).

Under physiological conditions, EAT serves as a buffer by supplying FFAs to adjacent myocardium, thereby protecting the heart from excess circulating lipids. It also stores triglycerides for energy provision and provides structural support to prevent coronary artery torsion (45, 48–50). Moreover, EAT contributes to metabolic homeostasis by secreting anti-inflammatory adipokines such as adiponectin. In obesity, however, EAT transforms into a pro-inflammatory fat depot (48).

Studies indicate that the thickness of the EAT in obese patients is 58.7% greater than in patients with a BMI < 25 kg/m2 (51). EAT expansion contributes to myocardial fibrosis, coronary microvascular dysfunction, and arrhythmogenesis via mechanical compression, lipid infiltration, and inflammatory signaling cascades (52, 53). Given its critical role in the progression of cardiovascular disease, EAT has emerged as a promising therapeutic target. Interventions such as weight loss, exercise, dietary modification, and pharmacologic treatments have been shown to reduce EAT volume and improve its inflammatory profile. Clinically, echocardiography, CT, and MRI can be employed to quantify EAT thickness or volume, aiding cardiovascular risk stratification and personalized treatment planning (45).

5 EAT: a pathophysiological link between obesity and HFpEF

Recent evidence has positioned EAT as a pivotal intermediary that bridges systemic metabolic disturbances of obesity with the myocardial structural and functional abnormalities characteristic of HFpEF (45). Studies have EAT thickness and expansion predict diastolic dysfunction more accurately than classical risk factors such as metabolic syndrome or BMI, and play a contributory role even in the early stages of heart failure, underscoring their value in cardiometabolic risk stratification (51, 54–56).

A single-center prospective study demonstrated that higher BMI and EAT volume were associated with increased rates of left ventricular reverse remodeling (LVRR) in patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. However, after adjustment for confounding factors, only EAT volume remained an independent predictor of LVRR (57). In another study involving patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2, EAT thickness was negatively correlated with global longitudinal strain(GLS) and left atrial contractile strain(LASct) suggesting its potential as an early marker for cardiac dysfunction in obese populations (56). Among both healthy individuals and patients with HFpEF, BMI and age correlate with EAT parameters, a pattern not observed in HFrEF (58). In HFpEF, increased EAT thickness was directly linked to elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cardiac troponin T (hs-TnT) levels, impaired left atrial-ventricular coupling and right ventricular-arterial coupling, and adverse composite outcomes, establishing EAT as an independent prognostic factor (59).

In a Japanese study, 213 obese patients underwent bariatric surgery and were followed for 5.3 years, they experienced a 22% reduction in BMI, a 14% decrease in EAT thickness, and significant improvement in left ventricular remodeling (all P < 0.0001) (60).

These findings indicate that EAT is an active pathogenic participant in myocardial dysfunction, it exerts adverse effects through mechanical constraint, pro-inflammatory and metabolic signaling, and coronary microvascular impairment (61, 62). Integrating current knowledge, we propose that EAT acts as a multifunctional mediator that translates systemic metabolic overload into myocardial injury through three interrelated domains: (1) inflammatory and metabolic reprogramming; (2) microvascular and neurohormonal dysregulation; and (3) mechanical and electrophysiological consequences.

5.1 From systemic triggers to EAT dysfunction

EAT serves as the specific mediator converting systemic metabolic stress into localised cardiac injury. In obesity and metabolic syndrome, excessive lipid influx, insulin resistance, and neurohormonal activation converge on EAT, driving maladaptive remodeling and secretory dysfunction (63). Compared with patients with HFrEF or non-HF controls, those with HFpEF exhibit markedly higher myocardial triglyceride accumulation and more pronounced cardiac steatosis (62). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy demonstrates a positive correlation between EAT volume and myocardial triglyceride accumulation (64). EAT distribution is heterogeneous, with focal obstructive lesions often located near coronary segments adjacent to the thickest EAT regions (53, 65). Fat infiltration into atrial and ventricular myocardium has been directly observed in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, indicating EAT's potential to induce electrophysiological heterogeneity and impair diastolic relaxation (53). Other studies reveal impaired glucose and lipid metabolism in Moreover, EAT from HF patients displays reduced levels of cardioprotective fatty acids and downregulated PPAR-α expression, resulting in altered lipid handling and impaired myocardial energetics (66).

5.2 Inflammatory and metabolic reprogramming

Under inflammatory and metabolic stress, EAT transforms into a depot of pathologic adipogenesis with a proinflammatory profile. In EAT from obese HFpEF patients, macrophages exhibit increased polarization to the proinflammatory M1 phenotype, with an increase in resident CD11c+/F4/80+ macrophages (67, 68). EAT also secretes adipokines that act in a paracrine fashion on adjacent myocardium. EAT expansion has reduced adiponectin secretion and increased proinflammatory mediators such as leptin, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, MCP-1, and resistin (69–74).

These mediators act locally on adjacent myocardium, EAT-derived IL-6 stimulates fibronectin and collagen I synthesis, promoting myocardial fibrosis (75). Reduced adiponectin further suppresses fatty acid oxidation, aggravating lipid deposition and oxidative stress (76, 77). Persistent leptin elevation, coupled with hyperaldosteronism and natriuretic peptide deficiency, enhances sodium retention, sympathetic activation, and myocardial hypertrophy, thereby accelerating HFpEF progression (78–80).

At the molecular level, proteomic analyses identify increased expression of inflammation-related proteins in EAT from HF patients, such as α1-antichymotrypsin (Serpina3), creatine kinase B (CKB), and matrix metalloproteinase-14 (MMP14) (81, 82). The EAT proteome further indicates that lipid metabolism dysregulation, inflammation activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction are major mechanisms in HFpEF. Cholesterol efflux from adipocytes is mediated by ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) and G1 (ABCG1) transporters, which are dysregulated in both subcutaneous and visceral fat during obesity and metabolic syndrome (83, 84). EAT from patients with coronary atherosclerotic heart disease exhibits high DNA methylation of ABCA1 and ABCG1, which may contribute to its pro-inflammatory phenotype, underscoring the importance of reverse cholesterol transport in EAT (85).

Regarding energy metabolism, patients with HFpEF exhibit marked mitochondrial fragmentation and cristae disruption, with reduced mitochondrial surface area. This impairs fatty acid utilisation, glucose uptake and metabolism, and branched-chain amino acid oxidation (86–88).The AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1α axis is a central regulatory pathway modulating inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function (89). Activated AMPK induces SIRT1, which suppresses NF-κβ activity by deacetylating p65/RelA, thereby reducing COX-2 and iNOS expression while upregulating anti-inflammatory antioxidant genes (90, 91). Additionally, SIRT1 deacetylates several residues on PGC-1α, a key mitochondrial regulator, thereby modulating mitochondrial activity (92). It also suppresses glycolysis via SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), altering protein function and gene expression in the failing heart (93). In EAT from patients with coronary artery disease, PGC-1α gene expression is downregulated, SIRT1 expression correlates positively with RELA, and miR-1247-5p expression is reduced, negatively correlating with BMI and PRKAA1 (which encodes the catalytic α-1 subunit of AMPK) (94). In EAT samples from AF patients, the degree of fibrotic remodeling correlates with LA myocardial fibrosis, and overexpression of HIF-1α may be involved in these processes (95).

Although current studies specifically focused on HFpEF are limited, post-translational protein modifications play important roles in various cardiovascular diseases. Given the involvement of key genes in HFpEF pathophysiology, we propose that such modifications in EAT may represent a potential mechanistic link in HFpEF.

5.3 Microvascular and neurohormonal dysregulation

Coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) has emerged as a novel mechanism linking EAT and HFpEF (22, 96–99). Autopsy studies reveal reduced coronary microvascular density (MVD) in HFpEF, correlating with the severity of myocardial fibrosis (100). Compared to patients without CMD, those with CMD have significantly thicker EAT, particularly in the BMI 25–30 kg/m2 subgroup (101). Studies have shown that EAT volume surrounding the left ventricle correlates with mean coronary flow reserve (CFR) and impacts diastolic function (102). In women with CMD, EAT attenuation is reduced; EAT-mediated inflammation and alterations in vascular tone may underlie the impaired microvascular reactivity (103).

The pathogenesis of CMD is not fully elucidated, but oxidative stress due to excess ROS production and accumulation, along with subsequent inflammatory responses, are considered key drivers (22, 104). Excess ROS production by coronary microvascular endothelial cells reduces NO bioavailability in adjacent cardiomyocytes, impairing the cGMP/PKG pathway that normally constrains cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Consequently, hypertrophy progresses and promotes ventricular remodeling, ultimately impairing myocardial diastolic function (22, 98). However, the causal relationship between CMD and HFpEF remains unclear, whether CMD precedes and causes remodeling and diastolic dysfunction or occurs secondary to myocardial remodeling in HFpEF remains unresolved.

Beyond local vascular effects, EAT accumulation also exacerbates neurohormonal activation in HFpEF. Compared to other adipose tissues, EAT shows increased catecholamine levels and elevated expression of biosynthetic enzymes, suggesting enhanced adrenergic activity. The combined effects of EAT, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation, and peripheral catecholamine production ultimately lead to cardiac sympathetic denervation (105).

5.4 Mechanical and electrophysiological consequences

Approximately 75% of EAT is distributed over the right ventricle, making it particularly susceptible to EAT-induced mechanical stress (106, 107). In the setting of limited pericardial compliance, EAT expansion exerts an external compressive force that impedes right ventricular filling and venous return, thereby amplifying ventricular interdependence. These changes contribute to right ventricular dysfunction and markedly impair exercise tolerance, a hallmark of obesity-related HFpEF (46, 108). Compared with non-obese HFpEF patients and healthy controls, obesity-related HFpEF patients exhibit more pronounced interventricular interaction abnormalities and pericardial constraint (7).

Beyond direct mechanical loading, inflammation and oxidative stress associated with myocardial interstitial inflammation impair the bioavailability of endothelial nitric oxide (NO), thereby disrupting the NO- cyclic guanosine monophosphate-protein kinase G (PKG) signalling pathway within cardiomyocytes (109, 110). PKG typically reduces passive tension and maintains myocardial compliance by phosphorylating the sarcomeric protein myosin, particularly at PKA/PKG sites within the N2B segment (111–113). In HFpEF, reduced NO and PKG activity leads to titin hypophosphorylation, increased myocardial cell stiffness, and impaired diastolic relaxation (22, 109). Concurrently, upregulation of protein kinase C (PKCα) and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity further enhances myosin phosphorylation at rigid PEVK domain sites, exacerbating myocardial stiffness (114, 115). These biomechanical alterations synergise with pericardial constriction induced by pericardial adipose tissue, amplifying diastolic dysfunction and elevating ventricular filling pressures.

The Framingham Heart Study followed patients with new-onset AF or HF for up to 7.5 years. It found that AF was associated with more than a twofold increased risk of developing HFpEF (116). In a similar vein, the PREVEND study demonstrated that AF increased the risk of HFpEF nearly sevenfold over a 10-year follow-up period (117). The presence of AF raises left atrial pressure, weakens its contractile function, and further contributes to arrhythmia development and progression in HFpEF patients (118). When EAT-derived FFA exceed mitochondrial oxidation capacity, lipotoxicity occurs. This leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, calcium dysregulation, and increased ROS production, all of which impair myocardial electrical activity (119). This promotes arrhythmogenesis and HF progression. Extracellular vesicles secreted from EAT in AF patients contain pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines and miRNAs. Co-incubation with human iPSC-derived cardiomyocyte sheets for 7 days shortensthe action potential duration during repolarization of myocardial cells by 80% (73).

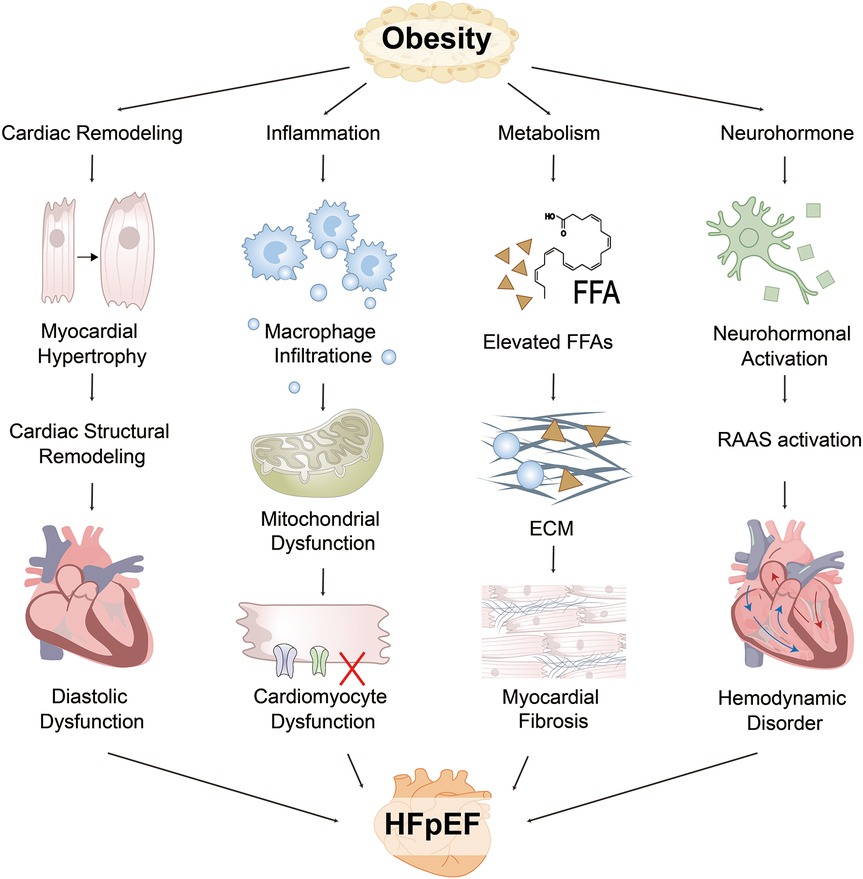

5.5 Integrative hierarchical framework

The existing evidence collectively supports a layered model, EAT acts as a multidimensional mediator linking systemic metabolic overload to myocardial injury in HFpEF. Systemic triggers (obesity, insulin resistance, neurohormonal activation) induce EAT dysfunction, subsequently driving inflammation and metabolic reprogramming, which in turn precipitate microvascular and neurohormonal dysregulation. These alterations ultimately yield mechanical and electrophysiological consequences manifesting as increased ventricular stiffness, fibrosis, and arrhythmia development.

Through this integrated cascade, EAT transforms from a benign fat reservoir into an organ actively participating in pathological processes, driving the progression of HFpEF. Consequently, interventions targeting the metabolic, inflammatory, and structural axes of EAT may represent effective strategies for future precision therapies (Figure 2).

6 Therapeutic strategies targeting EAT and future perspectives

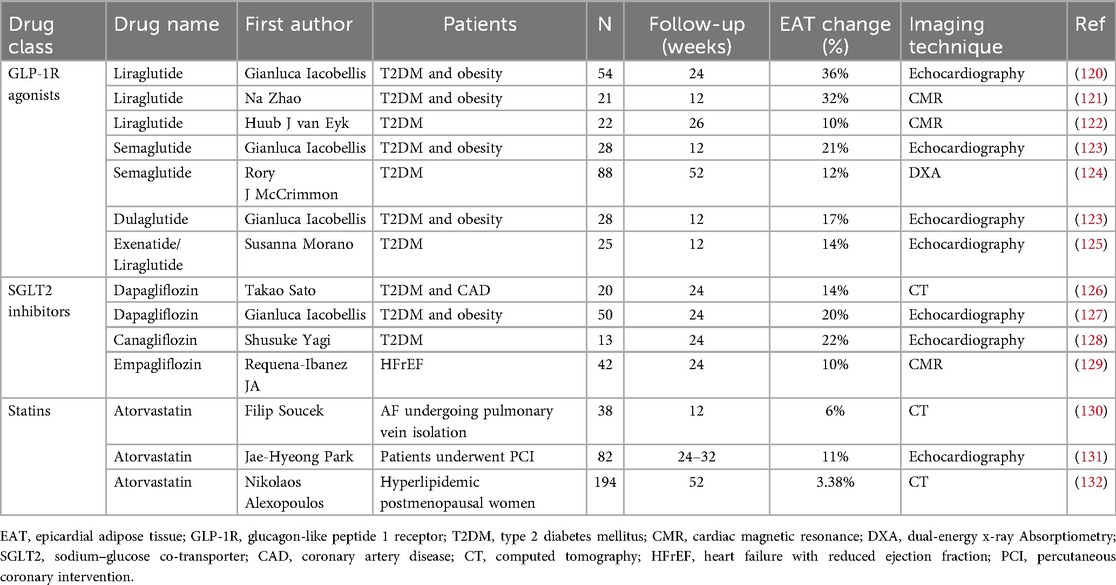

EAT has emerged as a promising therapeutic target due to its pleiotropic characteristics and responsiveness to pharmacological interventions with established cardiovascular benefits (Table 1). Lifestyle interventions including physical activity, dietary modification, and bariatric surgery can also effectively reduce EAT volume (133).

6.1 GLP-1 receptor agonists

Human EAT expresses glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which regulates local inflammation and ectopic lipid accumulation (134, 135). Activation of the GLP-1 receptor (GLP1R) in EAT has been shown to reduce local adipogenesis, enhance lipid utilization, promote adipocyte browning, and modulate the renin–angiotensin system (136). Clinical trials have specifically targeted the obese HFpEF phenotype using GLP-1R agonists or GLP-1R/GIP dual agonists. Long-acting agents such as semaglutide and tirzepatide significantly attenuate systemic inflammation, improve clinical features of HFpEF, and reduce adverse heart failure outcomes in obese individuals (137, 138). Liraglutide has been shown to ameliorate coronary inflammation, although its benefits may primarily stem from weight loss and glycemic control (139). Semaglutide also reduces vascular inflammation in advanced atherosclerosis models by suppressing activated macrophages (140). In obese patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), adjunctive liraglutide therapy significantly reduced EAT thickness compared to metformin monotherapy, independent of BMI reduction (120).

6.2 PPAR-γ agonists

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) agonists, possess both antidiabetic and lipid-lowering properties. Experimental studies have demonstrated that TZDs can directly target EAT, promoting rapid browning and increasing lipid turnover (141). In patients with T2DM and coronary artery disease, pioglitazone suppresses macrophage-mediated adipose tissue inflammation and IL-1β expression. Reductions in IL-1Ra and IL-10 are thought to be secondary to IL-1β suppression and unrelated to selective PPAR-γ mRNA modulation (142).

6.3 SGLT2 inhibitors

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) is abundantly expressed in human EAT, particularly in preadipocytes. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce hospitalization and improve quality of life in patients with HFpEF, with benefits extending beyond glycemic control and hemodynamic improvement (6, 143, 144). Agents such as dapagliflozin and empagliflozin have been shown to reduce EAT thickness, attenuate inflammation, improve myocardial fibrosis, and enhance fatty acid oxidation—thereby targeting EAT around the left atrium and coronary arteries for the treatment and prevention of AF and coronary artery disease (45, 127, 129, 145). Empagliflozin inhibits epicardial preadipocyte differentiation and downregulates proinflammatory adipokines including MCP-1 and IL-6 (143), in a dose-dependent manner. Long-term administration of the dual SGLT1/2 inhibitor sotagliflozin improves left atrial enlargement in HFpEF. In vitro studies reveal that sotagliflozin suppresses spontaneous calcium release events in atrial cardiomyocytes, prevents mitochondrial swelling, enhances mitochondrial Ca²+ buffering, mitigates mitochondrial fission and ROS generation during glucose deprivation, and prevents post-glycolysis Ca²+ overload—collectively reducing arrhythmogenic risk (146).

6.4 Lipid-lowering agents

Lipid-lowering agents, particularly statins, are frequently used in cardiovascular medicine and possess anti-inflammatory properties. In T2D-associated lipid disorders, EAT overexpresses low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 1 and very low-density lipoprotein receptor (147). Both in vitro and clinical studies have demonstrated that statins can reduce EAT thickness by modulating local inflammation (132, 148–151). EAT thickness directly correlates with inflammasome expression; in vitro, atorvastatin specifically exerts anti-inflammatory effects on cultured EAT adipocytes but not on subcutaneous tissue (150). Rosuvastatin has been shown to downregulate the NLRP3/GSDMD pathway and pyroptosis in HFpEF mouse models, while combination with spironolactone improves exercise tolerance and mitigates inflammatory injury (152).

Furthermore, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is expressed at both gene and protein levels in EAT, and its local expression is associated with EAT inflammation, predominantly in chemokine-enriched monocytes and lymphocytes. However, the therapeutic potential of PCSK9 inhibitors in this context remains to be confirmed (153).

6.5 Cytokine-targeted therapies

EAT expansion is driven by inflammation, and theoretically, inhibitors of cytokines like IL-1 and IL-6 could reduce EAT accumulation. However, clinical evidence remains inconclusive. The D-HART trial demonstrated that IL-targeting agents confer cardiac protection in patients with HFpEF (154). Yet, the subsequent D-HART2 study showed that IL-1 blockade with anakinra failed to improve exercise capacity in HFpEF (155). Further trials are warranted to clarify their effects on EAT in patients with T2DM and HFpEF.

7 Conclusion

Although the exact mechanisms linking EAT and HFpEF remain incompletely understood, current evidence strongly supports the involvement of EAT in the diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment of HFpEF. As a cardiovascular risk factor that can be measured using echocardiography, CT, or MRI, EAT adds value to risk stratification. Nonetheless, its precise contribution to heart failure pathophysiology continues to be actively explored.

EAT contributes to HFpEF through multiple mechanisms, including excessive fatty acid release leading to ectopic myocardial lipid accumulation, overexpression of local proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokines, arrhythmogenic effects, and enhanced β-adrenergic signaling. Current experimental findings suggest that certain drugs, such as GLP-1R agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, also exert therapeutic effects on EAT. It is anticipated that restoring EAT's cardioprotective properties through pharmacotherapy could yield benefits for cardiac metabolism.

Nevertheless, the quality of current evidence is limited. Most trials were small (often fewer than 60 participants, e.g., Yagi et al. n = 13; Zhao et al. n = 21) and of short duration (12–26 weeks), restricting statistical power and precluding firm conclusions about long-term efficacy or clinical outcomes. While early results are promising, findings should be interpreted with caution. Large, multicenter randomized controlled trials with longer follow-up and standardized imaging protocols are required to confirm the therapeutic relevance of targeting EAT.

Despite promising findings, EAT research faces ongoing challenges. In particular, most current studies focus on HFrEF, while data on HFpEF remain insufficient. Future studies are needed to determine whether reducing EAT volume can prevent HF onset. Pharmacological modulation of the EAT transcriptome to restore physiological and tissue-specific functions is an intriguing concept, but remains to be validated. A deeper understanding of EAT's potential role in improving prognosis, management, and therapeutic outcomes in HFpEF is critically important.

Author contributions

YZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HY: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – review & editing. WJ: Writing – review & editing. SZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Project supported by the Foundation from Jiangsu Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Grant No. k2021j17-3 and No. SLJ0326), the Natural Science Foundation of NJUCM (Grant No. XZR2024014) and the Outstanding Young Doctors Training Special Funding of Affiliated Hospital of NJUCM (Grant No. 2024QB019).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Campbell P, Rutten FH, Lee MM, Hawkins NM, Petrie MC. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: everything the clinician needs to know. Lancet. (2024) 403:1083–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02756-3

2. Khan MS, Shahid I, Bennis A, Rakisheva A, Metra M, Butler J. Global epidemiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2024) 21:717–34. doi: 10.1038/s41569-024-01046-6

3. Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, et al. 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American heart association. Circulation. (2024) 149(8):e347–913. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

4. Tsao CW, Lyass A, Enserro D, Larson MG, Ho JE, Kizer JR, et al. Temporal trends in the incidence of and mortality associated with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2018) 6(8):678–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.03.006

5. Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. (2006) 355:251–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256

6. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Böhm M, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:1451–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038

7. Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Pislaru SV, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA. Evidence supporting the existence of a distinct obese phenotype of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. (2017) 136:6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026807

8. Collaboration (NCD-RisC) NRF. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. (2024) 403:1027. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2

9. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (Accessed November 4, 2024).

10. van Essen BJ, Emmens JE, Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, Smit MD, Geluk CA, et al. Sex-specific risk factors for new-onset heart failure: the PREVEND study at 25 years. Eur Heart J. (2024) 46:1528–36. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae868

11. Savji N, Meijers WC, Bartz TM, Bhambhani V, Cushman M, Nayor M, et al. The association of obesity and cardiometabolic traits with incident HFpEF and HFrEF. JACC Heart Fail. (2018) 6:701–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.05.018

12. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 145(79):e263–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012

13. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2023 Focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European society of cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44(44):3627–39. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad195

14. Khan MS, Shahid I, Fonarow GC, Greene SJ. Classifying heart failure based on ejection fraction: imperfect but enduring. Eur J Heart Fail. (2022) 24:1154–7. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2470

15. Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Sorimachi H, Jarolim P, Borlaug BA. Uncoupling between intravascular and distending pressures leads to underestimation of circulatory congestion in obesity. Eur J Heart Fail. (2022) 24:353–61. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2377

16. Verbrugge FH, Omote K, Reddy YNV, Sorimachi H, Obokata M, Borlaug BA. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in patients with normal natriuretic peptide levels is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:1941–51. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab911

17. Buckley LF, Canada JM, Buono MGD, Carbone S, Trankle CR, Billingsley H, et al. Low NT-proBNP levels in overweight and obese patients do not rule out a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Failure. (2018) 5:372. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12235

18. Borlaug BA. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2014) 11:507–15. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.83

19. Borlaug BA, Kass DA. Mechanisms of diastolic dysfunction in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. (2006) 16:273–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.05.003

20. Borlaug BA, Paulus WJ. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur Heart J. (2011) 32:670–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq426

21. Daou D, Gillette TG, Hill JA. Inflammatory mechanisms in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Physiology. (2023) 38:217–30. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00004.2023

22. Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 62:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092

23. Westermann D, Lindner D, Kasner M, Zietsch C, Savvatis K, Escher F, et al. Cardiac inflammation contributes to changes in the extracellular matrix in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. (2011) 4(1):44–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.931451

24. Chirinos JA, Orlenko A, Zhao L, Basso MD, Cvijic ME, Li Z, et al. Multiple plasma biomarkers for risk stratification in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75:1281–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.069

25. Hatem SN, Sanders P. Epicardial adipose tissue and atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. (2014) 102:205–13. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu045

26. Hirata Y, Tabata M, Kurobe H, Motoki T, Akaike M, Nishio C, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis is associated with macrophage polarization in epicardial adipose tissue. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 58:248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.048

27. Kasner M, Westermann D, Lopez B, Gaub R, Escher F, ühl U K, et al. Diastolic tissue Doppler indexes correlate with the degree of collagen expression and cross-linking in heart failure and normal ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 57:977–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.024

28. Weber KT. Cardiac interstitium in health and disease: the fibrillar collagen network. J Am Coll Cardiol. (1989) 13:1637–52. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90360-4

29. Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix in ischemic and non-ischemic heart failure. Circ Res. (2019) 125:117–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.311148

30. Li L, Zhao Q, Kong W. Extracellular matrix remodeling and cardiac fibrosis. Matrix Biol. (2018) 68–69:490–506. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.01.013

31. Kruszewska J, Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A, Czarzasta K. Remodeling and fibrosis of the cardiac muscle in the course of obesity—pathogenesis and involvement of the extracellular matrix. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:4195. doi: 10.3390/ijms23084195

32. Aslam MI, Hahn VS, Jani V, Hsu S, Sharma K, Kass DA. Reduced right ventricular sarcomere contractility in HFpEF with severe obesity. Circulation. (2020) 143:965. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052414

33. Yoshii A, McMillen TS, Wang Y, Zhou B, Chen H, Banerjee D, et al. Blunted cardiac mitophagy in response to metabolic stress contributes to HFpEF. Circ Res. (2024) 135(10):1004–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.123.324103

34. Borlaug BA, Jensen MD, Kitzman DW, Lam CSP, Obokata M, Rider OJ. Obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: new insights and pathophysiological targets. Cardiovasc Res. (2022) 118:3434. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvac120

35. Bodenstab ML, Varghese RT, Iacobellis G. Cardio-lipotoxicity of epicardial adipose tissue. Biomolecules. (2024) 14:1465. doi: 10.3390/biom14111465

36. Wang J, Pu L, Zhang J, Xu R, Li Y, Yu M, et al. Effect of obesity on myocardial tissue characteristics in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance-based study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. (2025) 27:101903. doi: 10.1016/j.jocmr.2025.101903

37. Sun Q, Güven B, Wagg CS, Almeida de Oliveira A, Silver H, Zhang L, et al. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation is the major source of cardiac adenosine triphosphate production in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Res. (2024) 120:360–71. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvae006

38. Hahn VS, Petucci C, Kim M-S, Bedi KC, Wang H, Mishra S, et al. Myocardial metabolomics of human heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. (2023) 147:1147–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061846

39. Castiglione V, Gentile F, Ghionzoli N, Chiriacò M, Panichella G, Aimo A, et al. Pathophysiological rationale and clinical evidence for neurohormonal modulation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Card Fail Rev. (2023) 9:e09. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2022.23

40. Obokata M, Kane GC, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Olson TP, Jarolim P, et al. The neurohormonal basis of pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40:3707–17. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz626

41. Aimo A, Senni M, Barison A, Panichella G, Passino C, Bayes-Genis A, et al. Management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: from neurohormonal antagonists to empagliflozin. Heart Fail Rev. (2023) 28:179–91. doi: 10.1007/s10741-022-10228-8

42. Pedersen SD, Manjoo P, Dash S, Jain A, Pearce N, Poddar M. Pharmacotherapy for obesity management in adults: 2025 clinical practice guideline update. CMAJ. (2025) 197:E797–809. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.250502

43. Peikert A, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Kulac IJ, Litwin S, Zile M, et al. Near-universal prevalence of central adiposity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the PARAGON-HF trial. Eur Heart J. (2025) 46(25):2372–90. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf057

44. Ansaldo AM, Montecucco F, Sahebkar A, Dallegri F, Carbone F. Epicardial adipose tissue and cardiovascular diseases. Int J Cardiol. (2019) 278:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.089

45. Iacobellis G. Epicardial adipose tissue in contemporary cardiology. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2022) 19:593. doi: 10.1038/s41569-022-00679-9

46. Wong CX, Ganesan AN, Selvanayagam JB. Epicardial fat and atrial fibrillation: current evidence, potential mechanisms, clinical implications, and future directions. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38:1294–302. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw045

47. Sacks HS, Fain JN, Bahouth SW, Ojha S, Frontini A, Budge H, et al. Adult epicardial fat exhibits beige features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2013) 98:E1448–1455. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1265

48. Oikonomou EK, Antoniades C. The role of adipose tissue in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2019) 16:83–99. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0097-6

49. Mouton AJ, Li X, Hall ME, Hall JE. Obesity, hypertension, and cardiac dysfunction: novel roles of immunometabolism in macrophage activation and inflammation. Circ Res. (2020) 126:789–806. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.312321

50. Kenchaiah S, Ding J, Carr JJ, Allison MA, Budoff MJ, Tracy RP, et al. Pericardial fat and the risk of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77:2638. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.003

51. Aitken-Buck HM, Moharram M, Babakr AA, Reijers R, Hout IV, Fomison-Nurse IC, et al. Relationship between epicardial adipose tissue thickness and epicardial adipocyte size with increasing body mass index. Adipocyte. (2019) 8:412. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2019.1701387

52. Choy M, Huang Y, Peng Y, Liang W, He X, Chen C, et al. Association between epicardial adipose tissue and incident heart failure mediating by alteration of natriuretic peptide and myocardial strain. BMC Med. (2023) 21:117. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02836-4

53. Nalliah CJ, Bell JR, Raaijmakers AJA, Waddell HM, Wells SP, Bernasochi GB, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue accumulation confers atrial conduction abnormality. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:1197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.07.017

54. West HW, Siddique M, Williams MC, Volpe L, Desai R, Lyasheva M, et al. Deep-learning for epicardial adipose tissue assessment with computed tomography: implications for cardiovascular risk prediction. Jacc Cardiovascular Imaging. (2023) 16:800. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.11.018

55. Cavalcante JL, Tamarappoo BK, Hachamovitch R, Kwon DH, Alraies MC, Halliburton S, et al. Association of epicardial fat, hypertension, subclinical coronary artery disease, and metabolic syndrome with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. (2012) 110:1793–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.07.045

56. Chin JF, Aga YS, Abou Kamar S, Kroon D, Snelder SM, van de Poll SWE, et al. Association between epicardial adipose tissue and cardiac dysfunction in subjects with severe obesity. Eur J Heart Fail. (2023) 25:1936–43. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.3011

57. Yamaguchi Y, Shibata A, Yoshida T, Tanihata A, Hayashi H, Kitada R, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue volume is an independent predictor of left ventricular reverse remodeling in patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. (2022) 356:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.03.051

58. Wu C-K, Tsai H-Y, Su M-YM, Wu Y-F, Hwang J-J, Lin J-L, et al. Evolutional change in epicardial fat and its correlation with myocardial diffuse fibrosis in heart failure patients. J Clin Lipidol. (2017) 11:1421–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.08.018

59. Pugliese NR, Paneni F, Mazzola M, De Biase N, Del Punta L, Gargani L, et al. Impact of epicardial adipose tissue on cardiovascular haemodynamics, metabolic profile, and prognosis in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. (2021) 23:1858–71. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2337

60. Sorimachi H, Obokata M, Omote K, Reddy YNV, Takahashi N, Koepp KE, et al. Long-term changes in cardiac structure and function following bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 80:1501–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.738

61. van Woerden G, Gorter TM, Westenbrink BD, Willems TP, van Veldhuisen DJ, Rienstra M. Epicardial fat in heart failure patients with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. (2018) 20:1559–66. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1283

62. Wu C-K, Lee J-K, Hsu J-C, Su M-YM, Wu Y-F, Lin T-T, et al. Myocardial adipose deposition and the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. (2020) 22:445–54. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1617

63. Mukherjee AG, Renu K, Gopalakrishnan AV, Jayaraj R, Dey A, Vellingiri B, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue and cardiac lipotoxicity: a review. Life Sci. (2023) 328:121913. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121913

64. Ng ACT, Strudwick M, van der Geest RJ, Ng ACC, Gillinder L, Goo SY, et al. Impact of epicardial adipose tissue, left ventricular myocardial fat content, and interstitial fibrosis on myocardial Contractile function. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. (2018) 11(8):e007372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007372

65. Mahajan R, Lau DH, Brooks AG, Shipp NJ, Manavis J, Wood JP, et al. Electrophysiological, electroanatomical, and structural remodeling of the atria as consequences of sustained obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2015) 66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.058

66. Fosshaug LE, Dahl CP, Risnes I, Bohov P, Berge RK, Nymo S, et al. Altered levels of fatty acids and inflammatory and metabolic mediators in epicardial adipose tissue in patients with systolic heart failure. J Card Fail. (2015) 21:916–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.07.014

67. Patel VB, Mori J, McLean BA, Basu R, Das SK, Ramprasath T, et al. ACE2 deficiency worsens epicardial adipose tissue inflammation and cardiac dysfunction in response to diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. (2016) 65:85–95. doi: 10.2337/db15-0399

68. Patel VB, Shah S, Verma S, Oudit GY. Epicardial adipose tissue as a metabolic transducer: role in heart failure and coronary artery disease. Heart Fail Rev. (2017) 22:889–902. doi: 10.1007/s10741-017-9644-1

69. Gorter PM, van Lindert ASR, de Vos AM, Meijs MFL, van der Graaf Y, Doevendans PA, et al. Quantification of epicardial and peri-coronary fat using cardiac computed tomography; reproducibility and relation with obesity and metabolic syndrome in patients suspected of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. (2008) 197:896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.08.016

70. Madonna R, Massaro M, Scoditti E, Pescetelli I, De Caterina R. The epicardial adipose tissue and the coronary arteries: dangerous liaisons. Cardiovasc Res. (2019) 115:1013–25. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz062

71. Mahabadi AA, Reinsch N, Lehmann N, Altenbernd J, Kälsch H, Seibel RM, et al. Association of pericoronary fat volume with atherosclerotic plaque burden in the underlying coronary artery: a segment analysis. Atherosclerosis. (2010) 211:195–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.02.013

72. Verhagen SN, Visseren FLJ. Perivascular adipose tissue as a cause of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. (2011) 214:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.034

73. Shaihov-Teper O, Ram E, Ballan N, Brzezinski RY, Naftali-Shani N, Masoud R, et al. Extracellular vesicles from epicardial fat facilitate atrial fibrillation. Circulation. (2021) 143:2475–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052009

74. Patel VB, Basu R, Oudit GY. ACE2/Ang 1–7 axis: a critical regulator of epicardial adipose tissue inflammation and cardiac dysfunction in obesity. Adipocyte. (2016) 5:306–11. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2015.1131881

75. Chou C-H, Hung C-S, Liao C-W, Wei L-H, Chen C-W, Shun C-T, et al. IL-6 trans-signalling contributes to aldosterone-induced cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res. (2018) 114:690–702. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy013

76. Turer AT, Scherer PE. Adiponectin: mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Diabetologia. (2012) 55:2319–26. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2598-x

77. Salazar J, Luzardo E, Mejías JC, Rojas J, Ferreira A, Rivas-Ríos JR, et al. Epicardial fat: physiological, pathological, and therapeutic implications. Cardiol Res Pract. (2016) 2016:1291537. doi: 10.1155/2016/1291537

78. Theodorakis N, Kreouzi M, Hitas C, Anagnostou D, Nikolaou M. Adipokines and cardiometabolic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a state-of-the-art review. Diagnostics. (2024) 14:2677. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14232677

79. Mazurek T, Zhang L, Zalewski A, Mannion JD, Diehl JT, Arafat H, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation. (2003) 108:2460–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099542.57313.C5

80. Iacobellis G. Local and systemic effects of the multifaceted epicardial adipose tissue depot. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2015) 11:363–71. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.58

81. Zhao L, Guo Z, Wang P, Zheng M, Yang X, Liu Y, et al. Proteomics of epicardial adipose tissue in patients with heart failure. J Cell Mol Med. (2019) 24:511–20. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14758

82. He S, Zhu H, Zhang J, Wu X, Zhao L, Yang X. Proteomic analysis of epicardial adipose tissue from heart disease patients with concomitant heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol. (2022) 362:118–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.05.067

83. Vincent V, Thakkar H, Aggarwal S, Mridha AR, Ramakrishnan L, Singh A. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) expression in adipose tissue and its modulation with insulin resistance in obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. (2019) 12:275. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S186565

84. Frisdal E, Le Lay S, Hooton H, Poupel L, Olivier M, Alili R, et al. Adipocyte ATP-binding cassette G1 promotes triglyceride storage, fat mass growth, and human obesity. Diabetes. (2014) 64:840–55. doi: 10.2337/db14-0245

85. Miroshnikova VV, Panteleeva AA, Pobozheva IA, Razgildina ND, Polyakova EA, Markov AV, et al. ABCA1 And ABCG1 DNA methylation in epicardial adipose tissue of patients with coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2021) 21:566. doi: 10.1186/s12872-021-02379-7

86. Chaanine AH, Joyce LD, Stulak JM, Maltais S, Joyce DL, Dearani JA, et al. Mitochondrial morphology, dynamics, and function in human pressure overload or ischemic heart disease with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. (2019) 12:e005131. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005131

87. Lopaschuk GD, Karwi QG, Tian R, Wende AR, Abel ED. Cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. Circ Res. (2021) 128:1487. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318241

88. Tong D, Schiattarella GG, Jiang N, Altamirano F, Szweda PA, Elnwasany A, et al. NAD+ repletion reverses heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Res. (2021) 128:1629. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317046

89. Qi D, Young LH. AMPK: energy sensor and survival mechanism in the ischemic heart. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2015) 26:422–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.05.010

90. Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR, Frye RA, et al. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. (2004) 23(12):2369–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244

91. Rajendrasozhan S, Yang S-R, Kinnula VL, Rahman I. SIRT1, An antiinflammatory and antiaging protein, is decreased in lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2012) 177(8):861–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1269OC

92. Nemoto S, Fergusson MM, Finkel T. SIRT1 Functionally interacts with the metabolic regulator and transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α*. J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:16456–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501485200

93. Lim J-H, Lee Y-M, Chun Y-S, Chen J, Kim J-E, Park J-W. Sirtuin 1 modulates cellular responses to hypoxia by deacetylating hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Mol Cell. (2010) 38:864–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.023

94. Dogan N, Ozuynuk-Ertugrul AS, Balkanay OO, Yildiz CE, Guclu-Geyik F, Kirsan CB, et al. Examining the effects of coronary artery disease- and mitochondrial biogenesis-related genes’ and microRNAs’ expression levels on metabolic disorders in epicardial adipose tissue. Gene. (2024) 895:147988. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2023.147988

95. Abe I, Teshima Y, Kondo H, Kaku H, Kira S, Ikebe Y, et al. Association of fibrotic remodeling and cytokines/chemokines content in epicardial adipose tissue with atrial myocardial fibrosis in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. (2018) 15:1717–27. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.06.025

96. Del Buono MG, Montone RA, Camilli M, Carbone S, Narula J, Lavie CJ, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction across the Spectrum of cardiovascular diseases: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 78:1352–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.042

97. Franssen C, Chen S, Unger A, Korkmaz HI, De Keulenaer GW, Tschöpe C, et al. Myocardial microvascular inflammatory endothelial activation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2016) 4:312–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.10.007

98. Shah SJ, Lam CSP, Svedlund S, Saraste A, Hage C, Tan R-S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: PROMIS-HFpEF. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39:3439. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy531

99. Kitzman DW, Haykowsky MJ. Vascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Card Fail. (2016) 22:12–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.11.004

100. Mohammed SF, Hussain S, Mirzoyev SA, Edwards WD, Maleszewski JJ, Redfield MM. Coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. (2015) 131:550–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009625

101. Mahmoud I, Dykun I, Kärner L, Hendricks S, Totzeck M, Al-Rashid F, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue differentiates in patients with and without coronary microvascular dysfunction. Int J Obes. (2021) 45:2058–63. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00875-6

102. Nakanishi K, Fukuda S, Tanaka A, Otsuka K, Taguchi H, Shimada K. Relationships between periventricular epicardial adipose tissue accumulation, coronary microcirculation, and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Can J Cardiol. (2017) 33:1489–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.08.001

103. Patel NH, Dave EK, Fatade YA, De Cecco CN, Ko Y-A, Chen Y, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue attenuation on computed tomography in women with coronary microvascular dysfunction: a pilot, hypothesis generating study. Atherosclerosis. (2024) 395:118520. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.118520

104. Masi S, Rizzoni D, Taddei S, Widmer RJ, Montezano AC, Lüscher TF, et al. Assessment and pathophysiology of microvascular disease: recent progress and clinical implications. Eur Heart J. (2020) 42:2590–604. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa857

105. Parisi V, Rengo G, Perrone-Filardi P, Pagano G, Femminella GD, Paolillo S, et al. Increased epicardial adipose tissue volume correlates with cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with heart failure. Circ Res. (2016) 118:1244–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307765

106. Koepp KE, Obokata M, Reddy YN, Olson TP, Borlaug BA. Hemodynamic and functional impact of epicardial adipose tissue in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2020) 8:657. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.016

107. Sw R. Epicardial fat: properties, function and relationship to obesity. Obes Rev. (2007) 8:253–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00293.x

108. Gorter TM, van Woerden G, Rienstra M, Dickinson MG, Hummel YM, Voors AA, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue and invasive hemodynamics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2020) 8:667–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.06.003

109. van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Falcão-Pires I, Leite-Moreira AF, Begieneman MPV, Bronzwaer JGF, et al. Low myocardial protein kinase G activity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. (2012) 126:830–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076075

110. Schiattarella GG, Altamirano F, Tong D, French KM, Villalobos E, Kim SY, et al. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature. (2019) 568:351–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1100-z

111. Krüger M, Kötter S, Grützner A, Lang P, Andresen C, Redfield MM, et al. Protein kinase G modulates human myocardial passive stiffness by phosphorylation of the titin springs. Circ Res. (2009) 104:87–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184408

112. Cai Z, Wu C, Xu Y, Cai J, Zhao M, Zu L. The NO-cGMP-PKG axis in HFpEF: from pathological mechanisms to potential therapies. Aging Dis. (2023) 14:46–62. doi: 10.14336/AD.2022.0523

113. Tejero J, Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Sources of vascular nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species and their regulation. Physiol Rev. (2019) 99:311–79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2017

114. Zile MR, Baicu CF, Ikonomidis J, Stroud RE, Nietert PJ, Bradshaw AD, et al. Myocardial stiffness in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: contributions of collagen and titin. Circulation. (2015) 131:1247–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013215

115. Braz JC, Gregory K, Pathak A, Zhao W, Sahin B, Klevitsky R, et al. PKC-alpha regulates cardiac contractility and propensity toward heart failure. Nat Med. (2004) 10:248–54. doi: 10.1038/nm1000

116. Santhanakrishnan R, Wang N, Larson MG, Magnani JW, McManus DD, Lubitz SA, et al. Atrial fibrillation begets heart failure and vice versa: temporal associations and differences in preserved vs. Reduced ejection fraction. Circulation. (2016) 133:484–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018614

117. Vermond RA, Geelhoed B, Verweij N, Tieleman RG, Van der Harst P, Hillege HL, et al. Incidence of atrial fibrillation and relationship with cardiovascular events, heart failure, and mortality: a community-based study from The Netherlands. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2015) 66:1000–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1314

118. Reddy YN, Obokata M, Verbrugge FH, Lin G, Borlaug BA. Atrial dysfunction in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.07.009

119. Ernault AC, Meijborg VMF, Coronel R. Modulation of cardiac arrhythmogenesis by epicardial adipose tissue: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 78:1730–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.08.037

120. Iacobellis G, Mohseni M, Bianco SD, Banga PK. Liraglutide causes large and rapid epicardial fat reduction. Obesity. (2017) 25:311–6. doi: 10.1002/oby.21718

121. Zhao N, Wang X, Wang Y, Yao J, Shi C, Du J, et al. The effect of liraglutide on epicardial adipose tissue in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. (2021) 2021:5578216. doi: 10.1155/2021/5578216

122. van Eyk HJ, Paiman EHM, Bizino MB, de Heer P, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH, Kharagjitsingh AV, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial to assess the effect of liraglutide on ectopic fat accumulation in South Asian type 2 diabetes patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2019) 18:87. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0890-5

123. Iacobellis G, Villasante Fricke AC. Effects of semaglutide versus dulaglutide on epicardial fat thickness in subjects with type 2 diabetes and obesity. J Endocr Soc. (2020) 4:bvz042. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvz042

124. McCrimmon RJ, Catarig A-M, Frias JP, Lausvig NL, le Roux CW, Thielke D, et al. Effects of once-weekly semaglutide vs once-daily canagliflozin on body composition in type 2 diabetes: a substudy of the SUSTAIN 8 randomised controlled clinical trial. Diabetologia. (2020) 63:473–85. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-05065-8

125. Morano S, Romagnoli E, Filardi T, Nieddu L, Mandosi E, Fallarino M, et al. Short-term effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists on fat distribution in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: an ultrasonography study. Acta Diabetol. (2015) 52:727–32. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0710-z

126. Sato T, Aizawa Y, Yuasa S, Kishi S, Fuse K, Fujita S, et al. The effect of dapagliflozin treatment on epicardial adipose tissue volume. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2018) 17:6. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0658-8

127. Iacobellis G, Gra-Menendez S. Effects of dapagliflozin on epicardial fat thickness in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity. Obesity. (2020) 28:1068–74. doi: 10.1002/oby.22798

128. Yagi S, Hirata Y, Ise T, Kusunose K, Yamada H, Fukuda D, et al. Canagliflozin reduces epicardial fat in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr. (2017) 9:78. doi: 10.1186/s13098-017-0275-4

129. Requena-Ibáñez JA, Santos-Gallego CG, Rodriguez-Cordero A, Vargas-Delgado AP, Mancini D, Sartori S, et al. Mechanistic insights of empagliflozin in nondiabetic patients with HFrEF: from the EMPA-TROPISM study. JACC Heart Fail. (2021) 9:578–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2021.04.014

130. Soucek F, Covassin N, Singh P, Ruzek L, Kara T, Suleiman M, et al. Effects of atorvastatin (80 mg) therapy on quantity of epicardial adipose tissue in patients undergoing pulmonary vein isolation for atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. (2015) 116:1443. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.067

131. Park J-H, Park YS, Kim YJ, Lee IS, Kim JH, Lee J-H, et al. Effects of statins on the epicardial fat thickness in patients with coronary artery stenosis underwent percutaneous coronary intervention: comparison of atorvastatin with simvastatin/ezetimibe. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. (2010) 18:121. doi: 10.4250/jcu.2010.18.4.121

132. Alexopoulos N, Melek BH, Arepalli CD, Hartlage G-R, Chen Z, Kim S, et al. Effect of intensive versus moderate lipid-lowering therapy on epicardial adipose tissue in hyperlipidemic post-menopausal women: a substudy of the BELLES trial (beyond endorsed lipid lowering with EBT scanning). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 61:1956–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.051

133. Launbo N, Zobel EH, von Scholten BJ, Færch K, Jørgensen PG, Christensen RH. Targeting epicardial adipose tissue with exercise, diet, bariatric surgery or pharmaceutical interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. (2021) 22:e13136. doi: 10.1111/obr.13136

134. Malavazos AE, Iacobellis G, Dozio E, Basilico S, Di Vincenzo A, Dubini C, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue expresses glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, glucagon, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors as potential targets of pleiotropic therapies. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2023) 30:680–93. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwad050

135. Iacobellis G, Camarena V, Sant DW, Wang G. Human epicardial fat expresses glucagon-like peptide 1 and 2 receptors genes. Horm Metab Res. (2017) 49:625–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-109563

136. Beiroa D, Imbernon M, Gallego R, Senra A, Herranz D, Villarroya F, et al. GLP-1 agonism stimulates brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and browning through hypothalamic AMPK. Diabetes. (2014) 63:3346–58. doi: 10.2337/db14-0302

137. Zile MR, Borlaug BA, Kramer CM, Baum SJ, Litwin SE, Menon V, et al. Effects of tirzepatide on the clinical trajectory of patients with heart failure, preserved ejection fraction, and obesity. Circulation. (2025) 151:656–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.072679

138. Butler J, Shah SJ, Petrie MC, Borlaug BA, Abildstrøm SZ, Davies MJ, et al. Semaglutide versus placebo in people with obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a pooled analysis of the STEP-HFpEF and STEP-HFpEF DM randomised trials. Lancet. (2024) 403:1635–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00469-0

139. Jensen JK, Zobel EH, von Scholten BJ, Rotbain Curovic V, Hansen TW, Rossing P, et al. Effect of 26 weeks of liraglutide treatment on coronary artery inflammation in type 2 diabetes quantified by [64Cu]Cu-DOTATATE PET/CT: results from the LIRAFLAME trial. Front Endocrinol. (2021) 12:790405. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.790405

140. Jensen JK, Binderup T, Grandjean CE, Bentsen S, Ripa RS, Kjaer A. Semaglutide reduces vascular inflammation investigated by PET in a rabbit model of advanced atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. (2022) 352:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.03.032

141. Distel E, Penot G, Cadoudal T, Balguy I, Durant S, Benelli C. Early induction of a brown-like phenotype by rosiglitazone in the epicardial adipose tissue of fatty Zucker rats. Biochimie. (2012) 94:1660–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.04.014

142. Sacks HS, Fain JN, Cheema P, Bahouth SW, Garrett E, Wolf RY, et al. Inflammatory genes in epicardial fat contiguous with coronary atherosclerosis in the metabolic syndrome and type 2 DiabetesChanges associated with pioglitazone. Diabetes Care. (2011) 34:730–3. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2083

143. Takano M, Kondo H, Harada T, Takahashi M, Ishii Y, Yamasaki H, et al. Empagliflozin suppresses the differentiation/maturation of human epicardial preadipocytes and improves paracrine secretome profile. JACC Basic Transl Sci. (2023) 8:1081–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2023.05.007

144. Kosiborod MN, Deanfield J, Pratley R, Borlaug BA, Butler J, Davies MJ, et al. Semaglutide versus placebo in patients with heart failure and mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: a pooled analysis of the SELECT, FLOW, STEP-HFpEF, and STEP-HFpEF DM randomised trials. Lancet. (2024) 404:949–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01643-X

145. Habibi J, Aroor AR, Sowers JR, Jia G, Hayden MR, Garro M, et al. Sodium glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibition with empagliflozin improves cardiac diastolic function in a female rodent model of diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2017) 16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0489-z

146. Bode D, Semmler L, Wakula P, Hegemann N, Primessnig U, Beindorff N, et al. Dual SGLT-1 and SGLT-2 inhibition improves left atrial dysfunction in HFpEF. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2021) 20:7. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01208-z

147. Nasarre L, Juan-Babot O, Gastelurrutia P, Llucia-Valldeperas A, Badimon L, Bayes-Genis A, et al. Low density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 1 is upregulated in epicardial fat from type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and correlates with glucose and triglyceride plasma levels. Acta Diabetol. (2014) 51:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s00592-012-0436-8

148. Yamada Y, Takeuchi S, Yoneda M, Ito S, Sano Y, Nagasawa K, et al. Atorvastatin reduces cardiac and adipose tissue inflammation in rats with metabolic syndrome. Int J Cardiol. (2017) 240:332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.04.103

149. Packer M. Are the effects of drugs to prevent and to treat heart failure always concordant? The statin paradox and its implications for understanding the actions of antidiabetic medications. Eur J Heart Fail. (2018) 20:1100–5. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1183

150. Parisi V, Petraglia L, D'Esposito V, Cabaro S, Rengo G, Caruso A, et al. Statin therapy modulates thickness and inflammatory profile of human epicardial adipose tissue. Int J Cardiol. (2019) 274:326–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.06.106

151. Jialal I, Stein D, Balis D, Grundy SM, Adams-Huet B, Devaraj S. Effect of hydroxymethyl glutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitor therapy on high sensitive C-reactive protein levels. Circulation. (2001) 103:1933–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.15.1933

152. Xia YY, Shi Y, Li Z, Li H, Wu LD, Zhou WY, et al. Involvement of pyroptosis pathway in epicardial adipose tissue—myocardium axis in experimental heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2022) 636:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.10.109

153. Dozio E, Ruscica M, Vianello E, Macchi C, Sitzia C, Schmitz G, et al. PCSK9 Expression in epicardial adipose tissue: molecular association with local tissue inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. (2020) 2020:1348913. doi: 10.1155/2020/1348913

154. Van Tassell BW, Arena R, Biondi-Zoccai G, Canada JM, Oddi C, Abouzaki NA, et al. Effects of interleukin-1 blockade with anakinra on aerobic exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (from the D-HART pilot study). Am J Cardiol. (2014) 113:321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.08.047

155. Van Tassell BW, Buckley LF, Carbone S, Trankle CR, Canada JM, Dixon DL, et al. Interleukin-1 blockade in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: rationale and design of the diastolic heart failure anakinra response trial 2 (D-HART2). Clin Cardiol. (2017) 40:626–32. doi: 10.1002/clc.22719

Keywords: HFpEF, obesity, epicardial adipose tissue, mechanisms, metabolism

Citation: Zhou Y, Yan H, Zhu Y, Jiang W and Zhang S (2025) Multifactorial mechanisms of obesity-related HFpEF: the central role of epicardial adipose tissue and therapeutic perspectives. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1701459. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1701459

Received: 8 September 2025; Revised: 12 November 2025;

Accepted: 14 November 2025;

Published: 4 December 2025.

Edited by:

Francesca Musella, Ospedale Santa Maria delle Grazie, ItalyReviewed by:

Zhongwen Qi, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, ChinaVincenzo Nuzzi, Mediterranean Institute for Transplantation and Highly Specialized Therapies (ISMETT), Italy

Copyright: © 2025 Zhou, Yan, Zhu, Jiang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Weimin Jiang, andtMDQxMEBuanVjbS5lZHUuY24=; Shujie Zhang, enNodWppZXp6QDE2My5jb20=

Yuxin Zhou

Yuxin Zhou Han Yan

Han Yan Shujie Zhang

Shujie Zhang