Abstract

Background/objectives:

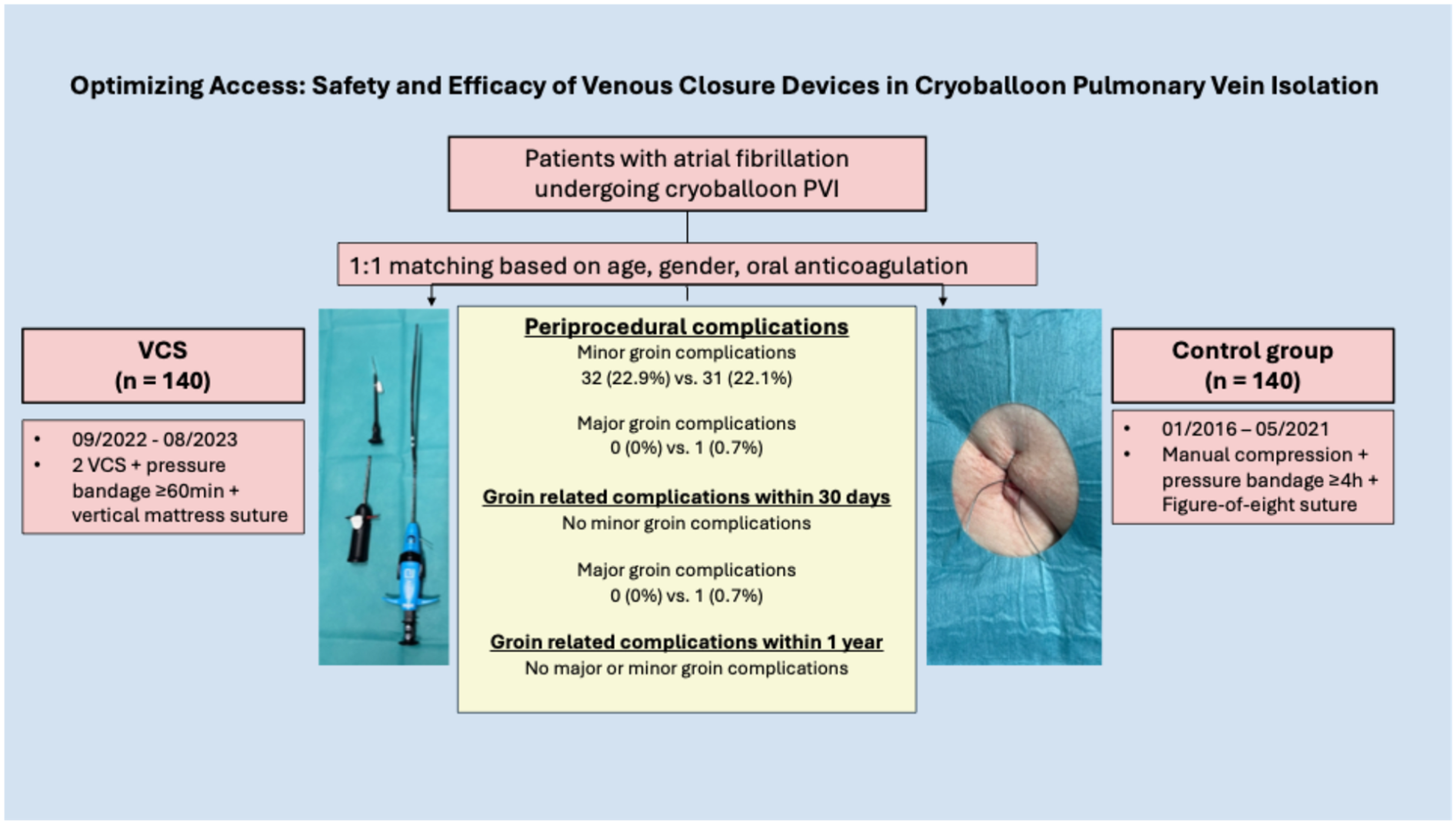

Despite technological progress in atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation, vascular access complications remain common. Venous closure systems (VCS) may reduce these events and improve patient comfort, but data on their safety and efficacy following cryoballoon-based pulmonary vein isolation (CB-PVI) are limited. This study assessed acute and long-term outcomes of VCS vs. manual compression and figure-of-eight suture after CB-PVI.

Methods:

We conducted a prospective, single-centre observational study comparing VCS with figure-of-eight suture plus manual compression post-CB-PVI. VCS patients who underwent CB-PVI between September 2022 and August 2023 were enrolled; controls were a 1:1 age-, sex-, and anticoagulation-matched cohort treated between January 2016 and May 2021. Ultrasound-guided access was used in all VCS cases and routinely from 2018 in controls. Pressure bandage time was ≥60 min in VCS vs. ≥4 h in controls. Vascular complications, emergency department (ED) visits, and readmissions were assessed over 12 months.

Results:

A total of 280 patients were included (mean age 70; 46.4% female; 38.9% paroxysmal AF). The VCS group had higher rates of hypertension (p = 0.036), coronary disease (p = 0.026), and body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.006). Groin-related periprocedural complications were similar (22.9% vs. 22.1%, p = 0.886); all were minor in the VCS group. One major complication occurred in controls. No groin-related ED visits occurred in the VCS group; one occurred in controls. Thirty-day ED visits were lower with VCS (3.6% vs. 15.1%, p < 0.001). Follow-up showed a trend toward fewer complications (2.5% vs. 8.5%, p = 0.053). Subgroup analysis (ultrasound-guidance only) confirmed these findings.

Conclusion:

VCS following CB-PVI is safe and feasible. No significant difference regarding acute, mid-term, and long-term groin complications was observed.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) remains the cornerstone therapy for atrial fibrillation (AF) (1). Recent technological advances have led to a steeper learning curve and shorter procedure times. Single-shot PVI techniques, such as cryoballoon (CB)-based PVI, have proven to be both safe and effective (2). However, vascular access site complications remain the most common adverse events, with reported incidences ranging from 1.8% to 4.0%, contributing to increased morbidity and delayed hospital discharge (3–6).

As a result, improving vascular access site safety has become a growing focus of clinical research.

In the context of same-day discharge, effective vascular access management—aimed at minimising bleeding and enabling early ambulation—is essential for the success of ambulatory care strategies. In addition to the use of smaller sheaths and fewer puncture sites, common approaches to reduce access-related complications include ultrasound-guided puncture, manual compression, and the figure-of-eight suture technique (7–10). Venous closure systems (VCS) may offer further improvements in vascular access management. Devices such as the Perclose ProStyle™ and Perclose ProGlide™ (Abbott Vascular, CA, USA) and the VASCADE MVP® (Haemonetics Corporation, MA, USA) have been shown to be safe and effective alternatives to manual compression following PVI (5, 11–14). In particular, the use of VCS following CB- and pulsed-field ablation-based PVI has demonstrated reduced time to hemostasis and ambulation when compared with manual compression and the figure-of-eight suture technique. In addition, shorter time to ambulation associated with VCS use may translate into improved patient comfort and overall procedural satisfaction (5, 14). However, no data are currently available comparing VCS directly with conventional hemostasis strategies—manual compression and figure-of-eight suture—exclusively following CB-based PVI. This single-centre, observational study aims to compare VCS with conventional hemostasis methods following CB-based PVI under real-world conditions over a 12-month follow-up (FU) period.

Methods

Patient population

All consecutive patients with symptomatic AF who underwent de novo cryoballoon-based pulmonary vein isolation (CB-PVI) with VCS between September 2022 and August 2023 were prospectively enrolled in the Lübeck Ablation Registry. For comparison, a 1:1 matched control cohort—drawn from the institutional ablation registry and treated between January 2016 and May 2021—was identified based on age, sex, and oral anticoagulation status. In the control group, conventional hemostasis techniques, including manual compression and figure-of-eight suture, were used. A subset of VCS-treated patients (24.3%) also participated in the STYLE-AF study.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Lübeck Ablation Registry, ethical review board number: 2024-377_1) and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments (15). All patients provided written informed consent for the procedure and were enrolled in the Lübeck Ablation Registry.

Preprocedural management

Preprocedural transoesophageal echocardiography was performed to exclude intracardiac thrombi in patients who had not received uninterrupted therapeutic dosing of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for at least 3 weeks (16, 17). For patients on vitamin K antagonists, a periprocedural international normalised ratio (INR) of 2.0–3.0 was targeted. In patients receiving DOACs, the morning dose was withheld on the day of the procedure.

Intraprocedural management

All CB-PVI procedures were performed in accordance with the institutional standard protocol. Detailed intraprocedural management has been described previously (5, 18–20).

Procedures were conducted under deep sedation using a combination of propofol, midazolam, and fentanyl. Vascular access was obtained via two punctures of the right femoral vein. In the VCS group, all punctures were performed under ultrasound guidance, whereas in the control group, ultrasound guidance was routinely implemented from 2018 onward.

A single transseptal puncture was performed under fluoroscopic guidance using a standard Brockenbrough needle and an 8.5 F transseptal sheath (SL1, Abbott, Illinois, USA) to access the left atrium. Following transseptal access, an intravenous bolus of heparin was administered to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) > 300 s throughout the procedure. PVI was performed using either the POLARx™ system (Boston Scientific, St. Paul, MN, USA) or the second-/fourth-generation Arctic Front CB (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). The associated steerable sheaths had outer diameters of 15.9 F (POLARSHEATH, Boston Scientific) and 15 F (FlexCath Advance™, Medtronic). A spiral mapping catheter (Achieve™, Medtronic, Inc., or POLARMAP™, Boston Scientific) was positioned in the target pulmonary vein to guide and monitor isolation. The administration of protamine at the conclusion of the procedure was permitted in accordance with institutional protocols and was at the discretion of the operator.

VCS group

After a successful ultrasound-guided venous puncture, a guidewire was inserted, and an 8 F introducer sheath was temporarily advanced. The sheath was then removed, and the first VCS (ProGlide™ or ProStyle™) was advanced over the wire and deployed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, the guidewire and the 8 F sheath were reintroduced to maintain access. Following this, the sheath was again removed, and a second VCS was inserted over the wire and deployed at an angle of approximately 30°–45° relative to the first. Subsequently, the guidewire and the 8 F sheath were reintroduced to continue with the procedure as per standard workflow. At the end of the procedure, following final sheath removal and activation of the suture-mediated closure, manual compression was applied if deemed necessary by the operator. To optimise skin adaptation and reduce superficial bruising, a vertical mattress suture (Donati technique) was placed at each access site (Figure 1). A pressure bandage was applied thereafter.

Figure 1

Venous closure device.

Control group

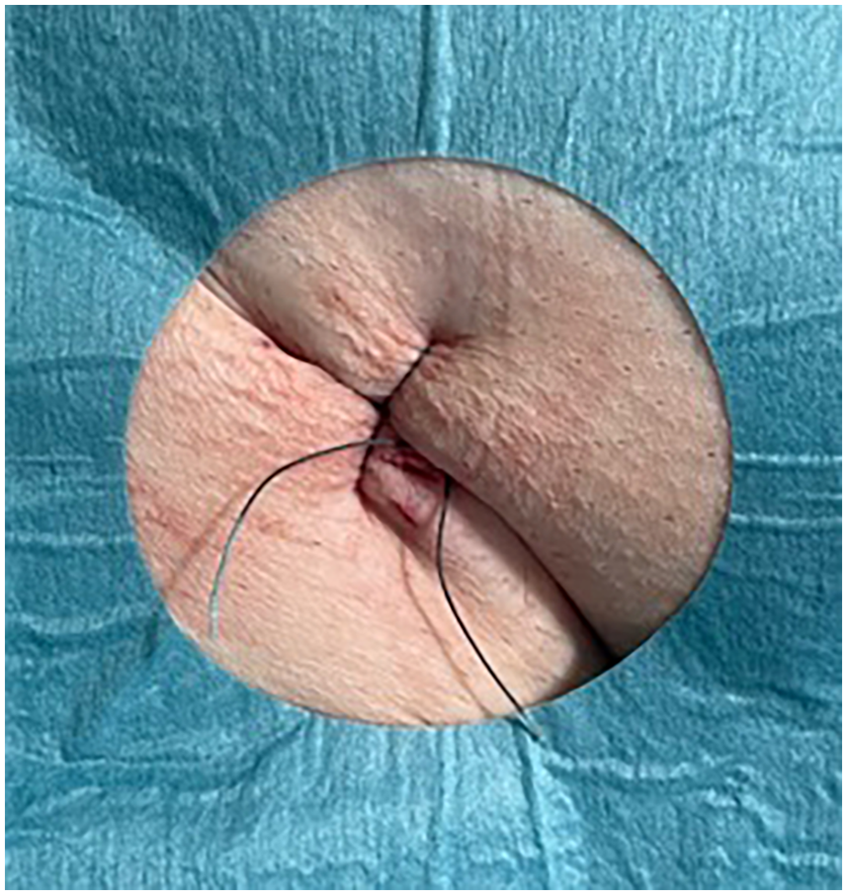

After sheath removal, a figure-of-eight suture and manual compression were applied. A pressure bandage was placed once hemostasis was achieved (Figure 2). The duration of compression was adjusted according to the individual clinical scenario.

Figure 2

Figure-of-eight suture.

Postprocedural management

Pericardial effusion was ruled out at the end of the procedure, 1 h post-intervention, and again on the following day. The pressure bandage was removed after a minimum of 60 min in the VCS group and after at least 4 h in the control group. Both the vertical mattress suture and the figure-of-eight suture were removed on the day after ablation.

All patients underwent continuous non-invasive monitoring of blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and electrocardiogram (ECG), and received a 24 h Holter ECG. Oral anticoagulation was resumed 6 h after the procedure and continued for at least 3 months, with further continuation based on the CHA2DS2-VASc score, in accordance with the prevailing ESC guidelines (16, 17). Antiarrhythmic drugs were prescribed for 3 months during the blanking period.

Follow-up

Outpatient follow-up visits were recommended at 3, 6, and 12 months after the ablation procedure, either in our institution's outpatient department or with the referring cardiologist. Follow-up assessments included a review of clinical history, a 12-lead ECG, and a 24 h Holter ECG. Atrial arrhythmia recurrence was defined as the occurrence of any atrial arrhythmia beyond the blanking period.

At the end of the follow-up period, the hospital information system was reviewed to identify potential complications and adverse events. Vascular access site complications were categorised as either minor or major. A complication was classified as major if it resulted in permanent harm, required surgical or interventional treatment, involved bleeding necessitating transfusion, prolonged hospitalisation of >48 h, or led to death (21). Complications not fulfilling these criteria were considered minor. Haematomas were classified as small (<6 cm) or large (>6 cm) based on clinical examination.

Subgroup analysis

Ultrasound-guided venous puncture was introduced as the standard approach at our institution in 2018. Consequently, not all patients in the control group underwent ultrasound-guided access. To account for the potential influence of ultrasound guidance on outcomes, a subgroup analysis was performed comparing the VCS group to only those control patients who received ultrasound-guided puncture.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were initially analysed by the Shapiro–Wilk test for normal distribution. They are described as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally or as median and interquartile range [median (quartile 1, quartile 3)] for non-normally distributed data. Student's t-test was used for comparing the mean value of a variable between two study populations. In case of non-normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. Categorial variables were shown by absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies. They were compared by the usage of Fisher's exact test or chi-squared test depending on sample size. Event-free survival was estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared via the log-rank test. Data matching was made by the use SPSS version 29.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics), and all the following calculations were made by Jamovi version 2.6.25. All p-values are two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 140 consecutive patients were analysed (mean age 70 years; 46.4% female; 56.4% with persistent AF). Arterial hypertension (81.0% vs. 70.0%, p = 0.036), vascular disease (50.7% vs. 32.9%, p = 0.002), and coronary artery disease (35.7% vs. 23.6%, p = 0.026) were more prevalent in the VCS group. Patients treated with VCS also had a significantly higher body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.006). Detailed baseline characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1

| Variables | Total cohort (n = 280) | VCS (n = 140) | Control (n = 140) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age (years), median (UQ; OQ) | 70 (62.8; 77) | 70.5 (63; 77) | 70 (62; 77) | 0.949 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 130 (46.4) | 65 (46.4) | 65 (46.4) | 1 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (UQ; OQ) | 27.7 (24.5; 31) | 28.3 (25.3; 31.6) | 26.6 (24.1; 30.2) | 0.006 |

| Atrial fibrillation | ||||

| Paroxysmal, n (%) | 109 (38.9) | 55 (39.3) | 54 (38.6) | 0.598 |

| Persistent, n (%) | 162 (57.9) | 79 (56.4) | 83 (59.3) | |

| Long persistent, n (%) | 9 (3.2) | 6 (4.3) | 3 (2.1) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 213 (76.1) | 114 (81) | 99 (70) | 0.036 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 28 (10) | 18 (12.9) | 10 (7.1) | 0.111 |

| Vascular disease, n (%) | 119 (42.5) | 71 (50.7) | 48 (34.3) | 0.005 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 83 (29.6) | 50 (35.7) | 33 (23.6) | 0.026 |

| Systolic heart failure, n (%) | 32 (11.4) | 14 (10) | 18 (12.9) | 0.452 |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 30 (10.7) | 14 (10) | 16 (11.4) | 0.699 |

| Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 26 (9.3) | 9 (6.4) | 17 (12.1) | 0.100 |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 8 (2.9) | 3 (2.1) | 5 (3.6) | 0.723 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF (%), median (UQ; OQ) | 55 (50; 56) | 55 (50; 60) | 55 (53; 55) | 0.341 |

| Number, n | 191 | 66 | 125 | |

| Medication | ||||

| Oral anticoagulation, n (%) | 258 (92.1) | 129 (92.1) | 129 (92.1) | 1 |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 59 (21.1) | 23 (16.4) | 36 (25.7) | 0.057 |

| Scores | ||||

| NYHA | ||||

| Number, n | 173 | 50 | 123 | |

| Median (UQ; OQ) | 1 (1; 2) | 2 (1; 2) | 1 (1; 2) | <0.001 |

| EHRA | ||||

| Median (UQ; OQ) | 2 (2; 2.25) | 2 (2; 2) | 2 (2; 3) | 0.011 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | ||||

| Median (UQ; OQ) | 2 (1; 4) | 3 (1; 4) | 2 (1; 4) | 0.248 |

| HASBLED score | ||||

| Median (UQ; OQ) | 2 (1; 2) | 2 (1; 2) | 2 (1; 2) | 0.659 |

Patient characteristics.

TIA, transitory ischemic attack; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

The bold values indicate statistically significant p-values.

Periprocedural data

Ultrasound-guided venous access was performed significantly more often in the VCS group (100% vs. 68.8%, p < 0.001). The most frequently used closure device in the VCS group was ProGlide™ (82.1%), followed by ProStyle™ (17.9%). VCS failure occurred in 2.9% of patients, who were subsequently managed with a figure-of-eight suture and manual compression to achieve hemostasis.

Fluoroscopy time [9.15 (6.57; 12.1) vs. 11.3 (7.50; 16.4) min, p < 0.001] and total procedure time [52 (44.8; 60) vs. 55 (45; 70) min, p = 0.047] were significantly shorter in the VCS group compared with the control group.

The most used CB was the fourth-generation Arctic Front Advance Pro (52.1%), followed by POLARx™ (28.6%) and the second-generation Arctic Front (19.3%).

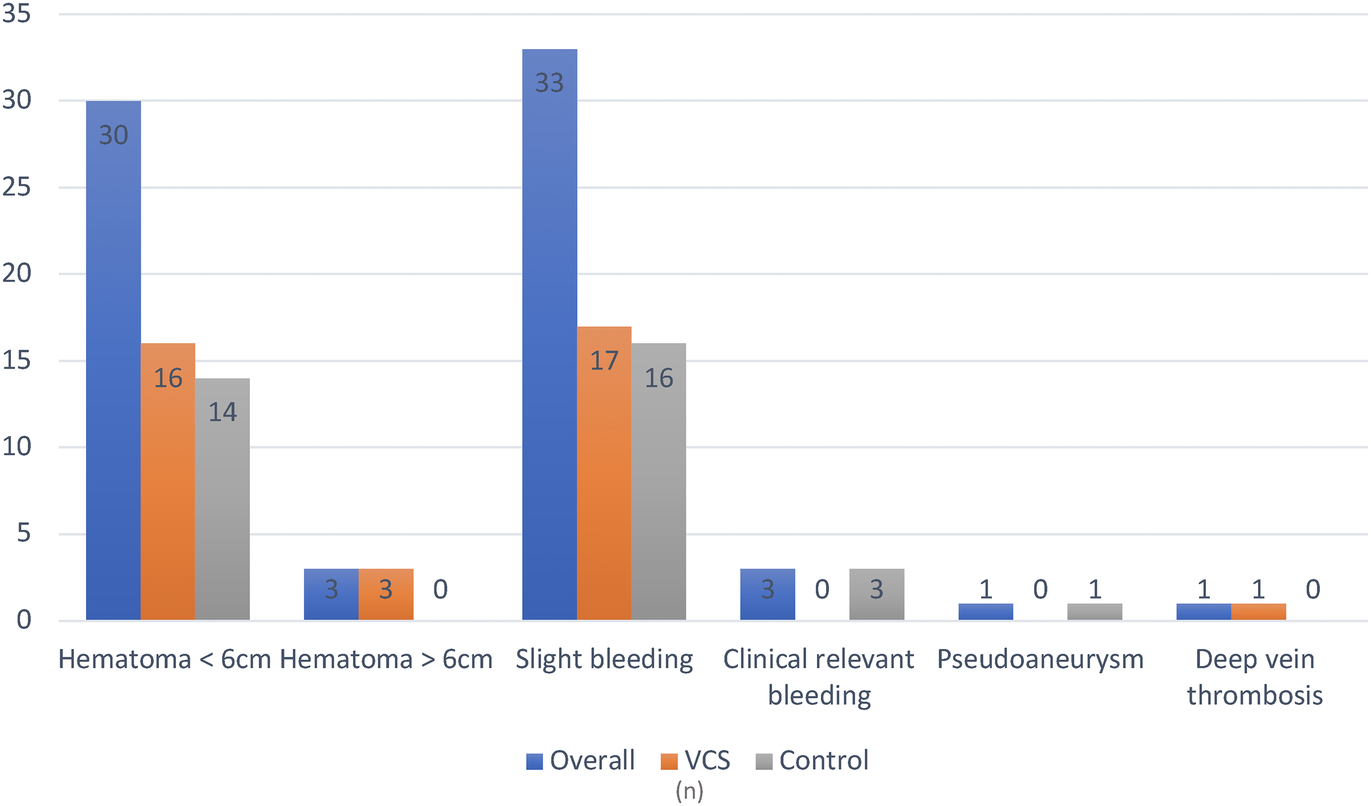

Overall, vascular access site complications occurred in 22.5% of all patients. No major complications were reported in the VCS group, whereas one major complication (pseudoaneurysm) occurred in the control group (p = 1). Clinically relevant bleeding events not requiring transfusion were observed in 2.1% of control group patients and none in the VCS group. The most frequent complication in both groups was groin haematoma <6 cm (11.4% vs. 10.0%, p = 0.699). One patient in the control group experienced a femoral pseudoaneurysm that required surgery. The postoperative course was complicated by sepsis and multiorgan failure, resulting in death. Same-day discharge was performed exclusively in the VCS group (7.9% vs. 0%, p < 0.001). Detailed results are presented in Tables 2, 3 and Figure 3.

Table 2

| Variables | Total cohort (n = 280) | VCS (n = 140) | Control (n = 140) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural data | ||||

| Isolation of all PV, n (%) | 278 (99.3) | 140 (100) | 138 (98.6) | 0.498 |

| CB, n (%) | ||||

| POLARx™ | 80 (28.6) | 65 (46.4) | 15 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Arctic Front 2. generation | 54 (19.3) | 0 (0) | 54 (38.6) | |

| Arctic Front 4. generation | 146 (52.1) | 75 (53.6) | 71 (50.7) | |

| Fluoroscopy time (min), median (UQ; OQ) | 10 (7.1; 14.2) | 9.15 (6.57; 12.1) | 11.3 (7.50; 16.4) | <0.001 |

| Dose area product (cGycm²), median (UQ; OQ) | 920 (463; 1,866) | 855 (472; 1,408) | 1,140 (423; 2,380) | 0.097 |

| Procedural time (min), median (UQ; OQ) | 53 (45; 62.3) | 52 (44.8; 60) | 55 (45; 70) | 0.047 |

| Contrast agent (ml), median (UQ; OQ) | 70 (45; 62.3) | 70 (60; 80) | 60 (60;100) | 0.404 |

| Groin-related procedural data | ||||

| Ultrasound-guided puncture, n (%) | 236 (84.3) | 140 (100) | 96 (68.8) | <0.001 |

| VCS | ||||

| Amount VCS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 140 (50) | 0 | 140 (100) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 137 (48.9) | 137 (97.9) | 0 | |

| 3 | 3 (1.1) | 3 (2.1) | 0 | |

| Type VCS, n (%) | ||||

| No VCS | 140 (50) | 0 (0) | 140 (100) | <0.001 |

| ProGlide™ | 115 (41.1) | 115 (82.1) | 0 | |

| ProStyle™ | 25 (8.9) | 25 (17.9) | 0 | |

| VCS failure, n (%) | 4 (2.9) | |||

| Periprocedural complications without groin complications | ||||

| Patients with complications in total, n (%) | 28 (10) | 15 (10.7) | 13 (9.3) | 0.690 |

| Pericardial effusion during ablation, n (%) | ||||

| Yes, with intervention | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Yes, without intervention | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Pericardial effusion following ablation, n (%) | ||||

| Yes, with intervention | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.4) | 0.498 |

| Yes, without intervention | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.4) | 0.498 |

| Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Phrenic nerve palsy, n (%) | ||||

| Transient | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Until the end of the procedure | 13 (4.6) | 7 (5) | 6 (4.3) | 1 |

| AV-Block III° with intervention, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Pulmonary artery embolism, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Other complications, n (%) | 13 (4.6) | 7 (5) | 6 (4.3) | 1 |

| Death, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

Periprocedural data.

The bold values indicate statistically significant p-values.

Table 3

| Variables | Total cohort (n = 280) | VCS (n = 140) | Control (n = 140) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall patients with groin complications, n (%) | 63 (22.5) | 32 (22.9) | 31 (22.1) | 0.886 |

| Major, n (%) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 0.492 |

| Minor, n (%) | 63 (100) | 32 (100) | 31 (100) | 1 |

| Haematoma < 6 cm, n (%) | 30 (10.7) | 16 (11.4) | 14 (10) | 0.699 |

| Haematoma > 6 cm, n (%) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0.247 |

| Minor bleeding, n (%) | 33 (11.8) | 17 (12.1) | 16 (11.4) | 0.853 |

| Clinically relevant groin bleeding, n (%) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.1) | 0.247 |

| Pseudoaneurysm, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Deep vein thrombosis (%) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 |

Groin-related periprocedural complications. Since some patients experienced more than one type of complication, the total number of complications exceeds the number of individuals affected.

Figure 3

Overview of periprocedural groin complications. VCS, venous closure system.

Short-term follow-up (<30 days)

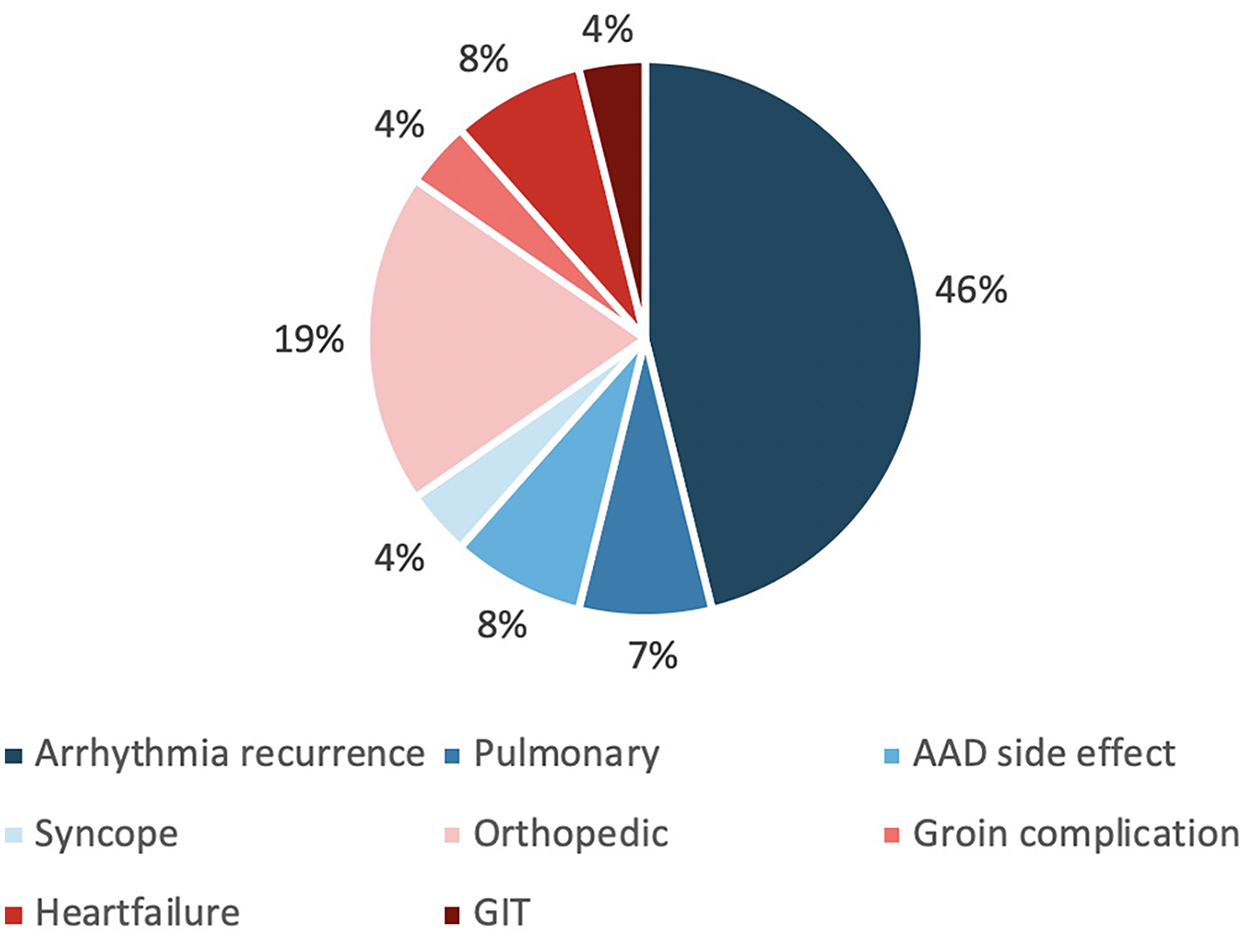

Within 30 days following ablation, a significantly higher number of patients in the control group presented to the emergency department (ED) (15.1% vs. 3.6%, p < 0.001). One patient (4.8%) in the control group presented with painful groin swelling, which was diagnosed as a pseudoaneurysm. All other ED presentations were unrelated to vascular access site complications. The most common reason for ED visits was arrhythmia recurrence (46%), followed by orthopaedic complaints (19%) (Table 4, Figure 4).

Figure 4

Overview of causes of emergency department visits within 30 days post-ablation. AAD, antiarrhythmic drug; GIT, gastrointestinal tract.

Table 4

| Variables | Total cohort (n = 279) | VCS (n = 140) | Control (n = 139) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation in emergency department, n (%) | ||||

| Total | 26 (9.3) | 5 (3.6) | 21 (15.1) | <0 . 001 |

| Groin-related | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 1 |

Presentation in the emergency department within 30 days post-ablation.

The bold values indicate statistically significant p-values.

Long-term follow-up (>30 days)

Follow-up beyond 30 days was completed in 89.3% of patients, with a median duration of 370 days (363; 390). A significantly lower arrhythmia recurrence rate beyond the blanking period was observed in the VCS group (26.7% vs. 40.8%, p = 0.019). The VCS group also showed numerically fewer complications (2.5% vs. 8.5%, p = 0.053) and other adverse events (3.3% vs. 7.7%, p = 0.172). No groin-related complications were reported in either group during long-term follow-up. Stroke and sick sinus syndrome each occurred in 1.6% of patients (Table 5).

Table 5

| Variables | Total cohort (n = 250) | VCS (n = 120) | Control (n = 130) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | ||||

| Overall complications, n (%) | 14 (5.6) | 3 (2.5) | 11 (8.5) | 0.053 |

| Death, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 |

| Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.3) | 0.623 |

| Groin complications | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Other complications, n (%) | 9 (3.6) | 2 (1.7) | 7 (5.4) | 0.175 |

| Sick sinus syndrome, n (%) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (100) | 2 (28.6) | |

| ASD, n (%) | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Acute heart failure due to arrhythmia recurrence, n (%) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0 | 2 (28.6) | |

| Other adverse events, n (%) | 14 (5.6) | 4 (3.3) | 10 (7.7) | 0.172 |

| GI bleeding, n (%) | 4 (28.6) | 2 (50) | 2 (20) | |

| Intracardiac thrombus, n (%) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (25) | 1 (10) | |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (25) | 2 (20) | |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | |

| Pulmonary oedema, n (%) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | |

| Non-procedure-related pericardial effusion, n (%) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | |

Follow-up.

ASD, atrium septum defect; GI, gastrointestinal.

Subgroup analysis

As previously mentioned, ultrasound-guided venous access was performed significantly more often in the VCS group (p < 0.001). Given this difference, a subgroup analysis was conducted excluding patients without ultrasound-guided access, resulting in 140 patients in the VCS group and 95 in the control group. The results of this analysis regarding periprocedural complications and ED visits within 30 days post-ablation were consistent with those of the overall cohort (Tables 6, 7).

Table 6

| Variables | Total cohort (n = 236) | VCS (n = 140) | Control (n = 96) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall patients with groin complications, n (%) | 49 (20.8) | 32 (22.9) | 17 (17.7) | 0.338 |

| Major, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.347 |

| Minor, n (%) | 49 (100) | 32 (100) | 17 (100) | 1 |

| Haematoma < 6 cm, n (%) | 25 (10.6) | 16 (11.4) | 9 (9.4) | 0.615 |

| Haematoma > 6 cm, n (%) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0.273 |

| Minor bleeding, n (%) | 24 (10.2) | 17 (12.1) | 7 (7.3) | 0.226 |

| Clinically relevant groin bleeding, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.407 |

| Pseudoaneurysm, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.407 |

| Deep vein thrombosis (%) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 |

Subgroup analysis—groin-related periprocedural complications.

Table 7

| Variables | Total cohort (n = 235) | VCS (n = 140) | Control (n = 95) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation in emergency department, n (%) | ||||

| Total | 21 (8.9) | 5 (3.6) | 16 (16.8) | <0 . 001 |

| Groin-related | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 1 |

Subgroup analysis—presentation in the emergency department within 30 days post-ablation.

The bold values indicate statistically significant p-values.

Discussion

The recently published STYLE-AF trial from our institution demonstrated the safety and feasibility of VCS in single-shot-based PVI, along with increased patient satisfaction due to shorter time to ambulation (5). However, no dedicated analysis of VCS exclusively in the setting of CB-based PVI, including long-term follow-up, has been conducted to date. The present study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of VCS specifically in CB-based PVI procedures.

The main findings are:

No significant difference regarding acute, mid-term, and long-term groin complications

No severe groin complications in the VCS group

Due to its short learning curve and favourable safety and efficacy profile, CB-PVI has become an established method for first-time ablation procedures (

2,

22). However, vascular access site complications remain the most frequent periprocedural events (

4). Prolonged manual compression, figure-of-eight suture techniques, and the extended application of often uncomfortable pressure bandages have long represented the standard approach to achieve hemostasis (

4,

7,

10).

The introduction of VCS offers the potential to improve both procedural safety and patient comfort (5). In our study, procedural time was significantly shorter in the VCS group. This observation may be explained by the fact that procedures in the VCS group were performed more recently, at a time when CB technology, procedural workflows, and overall operator experience had further advanced. Therefore, the shorter procedural times are not directly attributable to the use of VCS itself, but rather to the overall procedural evolution and increased experience during the study period (20).

VCS failure occurred in 2.9% of patients, which is consistent with previous reports from our centre (5). In these cases, hemostasis was successfully achieved with manual compression and a figure-of-eight suture. Despite a higher burden of comorbidities in the VCS group, no significant difference in the rate of periprocedural groin complications was observed between groups. The overall incidence of groin-related complications was comparable to previous studies (5), but importantly, no severe access site complications occurred in the VCS group. Although small groin haematomas (<6 cm) were more common in the VCS group, no clinically relevant bleeding events were reported. In contrast, such events did occur in the control group. None of the patients in either group required a blood transfusion; however, clinically significant bleeding would have precluded same-day discharge.

Same-day discharge following CB-PVI is increasingly viewed as a cornerstone of modern electrophysiological care (23, 24). In our cohort, same-day discharge was only performed in the VCS group, reflecting the more recent timing of their ablation procedures and the greater procedural efficiency and safety profile observed in this group.

Within 30 days post-ablation, ED presentations occurred more frequently in the control group. With the exception of one pseudoaneurysm case, all visits were not directly associated with vascular access site complications. The majority of presentations were due to arrhythmia recurrence or orthopaedic complaints. Orthopaedic-related ED visits were numerically more frequent in the control group (3.8% vs. 15.4%, p = 0.350), although this difference was not statistically significant. This may suggest an indirect association with reduced early mobility in patients treated without VCS. However, this observation remains speculative and requires confirmation in larger cohorts (5, 11).

Long-term follow-up over 12 months revealed a favourable safety profile, with numerically fewer complications and adverse events in the VCS group. Importantly, no groin-related complications were observed during the follow-up period, further supporting the long-term safety of VCS in the setting of CB-based PVI.

Given the imbalance in ultrasound-guided puncture between groups, a subgroup analysis was performed, including only patients who underwent ultrasound-guided venous access. The results of this analysis were consistent with those of the overall cohort, confirming the robustness of the findings.

Limitations

This was a prospective, single-centre, observational study. All procedures were performed by experienced operators at a high-volume electrophysiology centre, which may limit the generalisability of the results to lower-volume centres where procedural workflows and outcomes may be affected by the learning curve. The observed differences in procedural duration might, in part, reflect a more advanced stage of the learning curve in the VCS group.

Time to ambulation, time to hemostasis, and patient comfort were not assessed systematically and should be addressed in future studies. Moreover, the unequal use of ultrasound-guided puncture between groups may have influenced the results and could have a greater impact in larger or more diverse patient populations.

Conclusion

This study is the first to investigate VCS in CB-PVI with long-term follow-up. Despite a higher burden of comorbidities, VCS were safe and feasible, with no major access-site complications observed. Moreover, VCS-treated patients presented less frequently to the ED, which may reflect the benefits of shorter postprocedural immobilisation as demonstrated in previous studies. Overall, VCS offers patient-centred advantages without compromising safety or efficacy.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the local ethics committee (Lübeck Ablation Registry, ethical review board number: 2024-377_1) and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SH: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CHH: Writing – review & editing. SSP: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MD: Writing – review & editing. HG: Writing – review & editing. AT: Writing – review & editing. SR: Writing – review & editing. BS: Writing – review & editing. KU: Writing – review & editing. KK: Writing – review & editing. MK: Writing – review & editing. JV: Writing – review & editing. CE: Writing – review & editing. JN: Writing – review & editing. JPW: Writing – review & editing. KHK: Writing – review & editing. JM-W: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RRT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

CE received travel and research grants from Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, CardioFocus, and LifeTech and speaker honoraria from these companies as well as C.T.I. GmbH and Doctrina Med. CHH received travel and research grants from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, CardioFocus, and LifeTech and speaker honoraria from these companies plus C.T.I. GmbH and Doctrina Med. JPW received funding from the German Foundation of Heart Research (F/29/19), speaker fees from Abbott and Doctrina Med, and travel grants from Boston Scientific. JV received travel grants and speaker honoraria from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, C.T.I. GmbH, Doctrina Med, EHRA, and Philips. KHK received grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Biosense Webster, and Medtronic. MK received travel and congress support from Abbott Medical. RRT received lecture fees from Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Doctrina Med, Medtronic, Pfizer, Radcliffe Cardiology, cme4u, and Wikonect; consulting and advisory honoraria from Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Capvision, Guidepoint, Haemonetics, Medtronic, and Philips; institutional research support from Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, LifeTech, and Medtronic; and travel grants from Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Philips. SSP is a medical consultant for Active Health and received travel, congress, educational, and speaker grants from Abbott Medical and LifeTech.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence, and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Van Gelder IC Rienstra M Bunting KV Casado-Arroyo R Caso V Crijns HJGM et al 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. (2024) 45:3314–414. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae176

2.

Kuck K-H Brugada J Fürnkranz A Metzner A Ouyang F Chun KRJ et al Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:2235–45. 10.1056/NEJMoa1602014

3.

Arbelo E Brugada J Lundqvist CB Laroche C Kautzner J Pokushalov E et al Contemporary management of patients undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation: in-hospital and 1-year follow-up findings from the ESC-EHRA atrial fibrillation ablation long-term registry. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38(17):1303–16. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw564

4.

De Greef Y Ströker E Schwagten B Kupics K De Cocker J Chierchia G-B et al Complications of pulmonary vein isolation in atrial fibrillation: predictors and comparison between four different ablation techniques: results from the Middleheim PVI-registry. EP Eur. (2018) 20:1279–86. 10.1093/europace/eux233

5.

Tilz RR Feher M Vogler J Bode K Duta AI Ortolan A et al Venous vascular closure system vs. figure-of-eight suture following atrial fibrillation ablation: the STYLE-AF study. Europace. (2024) 26:euae105. 10.1093/europace/euae105

6.

Ekanem E Reddy VY Schmidt B Reichlin T Neven K Metzner A et al Multi-national survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety on the post-approval clinical use of pulsed field ablation (MANIFEST-PF). Europace. (2022) 24:1256–66. 10.1093/europace/euac050

7.

Mujer MT Al-Abcha A Flores J Saleh Y Robinson P . A comparison of figure-of-8-suture versus manual compression for venous access closure after cardiac procedures: an updated meta-analysis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2020) 43:856–65. 10.1111/pace.14008

8.

Teumer Y Eckart D Katov L Graf M Bothner C Rottbauer W et al Ultrasound-guided venous puncture reduces groin complications in electrophysiological procedures. Biomedicines. (2024) 12:2375. 10.3390/biomedicines12102375

9.

Yorgun H Canpolat U Ates AH Oksul M Sener YZ Akkaya F et al Comparison of standard vs modified “Figure-of-Eight” suture to achieve femoral venous hemostasis after cryoballoon based atrial fibrillation ablation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2019) 42:1175–82. 10.1111/pace.13764

10.

Aytemir K Canpolat U Yorgun H Evranos B Kaya EB Şahiner ML et al Usefulness of “figure-of-eight” suture to achieve haemostasis after removal of 15-French calibre femoral venous sheath in patients undergoing cryoablation. Europace. (2016) 18:1545–50. 10.1093/europace/euv375

11.

Fabbricatore D Buytaert D Valeriano C Mileva N Paolisso P Nagumo S et al Ambulatory pulmonary vein isolation workflow using the Perclose Proglide™ suture-mediated vascular closure device: the PRO-PVI study. Europace. (2023) 25:1361–8. 10.1093/europace/euad022

12.

Castro-Urda V Segura-Dominguez M Jiménez-Sánchez D Aguilera-Agudo C García-Izquierdo E De la Rosa Rojas Y et al Efficacy and safety of Proglide use and early discharge after atrial fibrillation ablation compared to standard approach. PROFA trial. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2023) 46:598–606. 10.1111/pace.14753

13.

Del Prete A Della Rocca DG Calcagno S Di Pietro R Del Prete G Biondi-Zoccai G et al Perclose Proglide™ for vascular closure. Future Cardiol. (2021) 17:269–82. 10.2217/fca-2020-0065

14.

Natale A Mohanty S Liu PY Mittal S Al-Ahmad A De Lurgio DB et al Venous vascular closure system versus manual compression following multiple access electrophysiology procedures: the AMBULATE trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2020) 6:111–24. 10.1016/j.jacep.2019.08.013

15.

World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. (2013) 310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053

16.

Kirchhof P Benussi S Kotecha D Ahlsson A Atar D Casadei B et al 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37:2893–962. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210

17.

Hindricks G Potpara T Dagres N Arbelo E Bax JJ Blomström-Lundqvist C et al 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. (2021) 42:373–498. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612

18.

Heeger C-H Popescu SȘ Sohns C Pott A Metzner A Inaba O et al Impact of cryoballoon application abortion due to phrenic nerve injury on reconnection rates: a YETI subgroup analysis. EP Eur. (2023) 25:374–81. 10.1093/europace/euac212

19.

Heeger CH Popescu SS Saraei R Kirstein B Hatahet S Samara O et al Individualized or fixed approach to pulmonary vein isolation utilizing the fourth-generation cryoballoon in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the randomized INDI-FREEZE trial. EP Eur. (2022) 24:921–7. 10.1093/europace/euab305

20.

Heeger C-H Popescu SS Inderhees T Nussbickel N Eitel C Kirstein B et al Novel or established cryoballoon ablation system for pulmonary vein isolation: the prospective ICE-AGE-1 study. Europace. (2023) 25:euad248. 10.1093/europace/euad248

21.

Calkins H Hindricks G Cappato R Kim Y-H Saad EB Aguinaga L et al 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace. (2018) 20:e1–e160. 10.1093/europace/eux274

22.

Theis C Kaiser B Kaesemann P Hui F Pirozzolo G Bekeredjian R et al Pulmonary vein isolation using cryoballoon ablation versus RF ablation using ablation index following the CLOSE protocol: a prospective randomized trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2022) 33:866–73. 10.1111/jce.15383

23.

Popescu SS Heeger CH Vogler J Eitel C Feher M Kirstein B et al Same day discharge after interventional electrophysiology procedures, first German experience. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44:ehad655.389. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad655.389

24.

Jafry AH Akhtar KH Khan JA Clifton S Reese J Sami KN et al Safety and feasibility of same-day discharge for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2022) 65:803–11. 10.1007/s10840-022-01145-9

Summary

Keywords

venous closure device, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary vein isolation, cryoballoon ablation, venous access

Citation

Hatahet S, Heeger CH, Popescu SS, Delgado M, Grasshoff H, Traub A, Reincke S, Subin B, Ukita K, Klotz K, Küchler M, Vogler J, Eitel C, Nikorowitsch J, Wenzel JP, Kuck KH, Meyer-Waeterling J and Tilz RR (2025) Optimising access: safety and efficacy of venous closure devices in cryoballoon pulmonary vein isolation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1704394. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1704394

Received

12 September 2025

Accepted

27 October 2025

Published

18 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Robert Hatala, National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases, Slovakia

Reviewed by

László Gellér, Cardiovascular Center Semmelweis University, Hungary

Peter Lukac, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Hatahet, Heeger, Popescu, Delgado, Grasshoff, Traub, Reincke, Subin, Ukita, Klotz, Küchler, Vogler, Eitel, Nikorowitsch, Wenzel, Kuck, Meyer-Waeterling and Tilz.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: S. Hatahet hatahet95@web.de

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.