Abstract

To explore the potential benefits of Stellate ganglion block (SGB) in regulating the central and peripheral systems, as well as its potential as a treatment option for these diseases. We conducted a comprehensive search in PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar libraries using the following keywords: stellate ganglion block, sympathetic nervous system, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, and perioperative stress response. We selected and critically reviewed research articles published in English related to SGB modulation for the treatment of central and peripheral disease. The collected literature was classified according to content and reviewed in combination with experimental results and clinical cases. SGB can help regulate the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems by blocking sympathetic signals, reducing overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system linked to cardiovascular diseases. This local nerve block technique could be a treatment option for these conditions.

Introduction

Excessive activation of the sympathetic nervous system is considered to be relevant to various central and peripheral system diseases, with the main focus on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Resistant hypertension, myocardial ischemia and secretion of brain hormones are due to high sympathetic activity and prolonged activation of the sympathetic nervous system (1–3). The cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems are regulated by the sympathetic nervous system, parasympathetic nervous system, and sensory nerves, with the sympathetic nervous system playing a pivotal role in disease development (4). Therefore, understanding the modulatory mechanisms of the sympathetic nervous system is crucial to prevent and treat cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. In recent years, researchers have discovered multiple strategies to improve sympathetic nervous activity, such as medication therapy, exercise, diet, and psychological interventions (5, 6). However, the use of medication therapy can lead to side effects, and exercise and dietary interventions demand ongoing dedication to prove their effectiveness. There is currently no optimal intervention to regulate sympathetic nervous activity and reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Therefore, finding more effective ways to modulate sympathetic nervous system activity remains an important research direction.

Regional nerve block has emerged as a significant area of research due to its effectiveness in modulating regional nerve activity through the inhibition of nerve signals. This technique is extensively utilized in managing various medical conditions and in postoperative pain relief. The Stellate Ganglion Block (SGB) is a traditional approach to nerve blockade, successfully addressing a range of issues, including chronic pain, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and Raynaud's disease (7–9). Ongoing investigations are increasingly highlighting the SGB's potential influence on both central and peripheral nervous systems. Prior research indicates that SGB may impact several cardiovascular parameters, such as heart rate, blood pressure, and vascular function, by altering sympathetic nerve activity (10–12). Specifically, SGB can elicit a cascade of cardiovascular responses, including a reduction in heart rate, peripheral vasodilation, and decreased blood pressure. These physiological changes are deemed significant for enhancing blood flow to the heart and brain, minimizing oxygen demand in myocardial and cerebral tissues, thereby alleviating symptoms associated with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disorders and potentially improving patient outcomes.

The objective of this narrative review is to present a comprehensive and current analysis of the impact of SGB on both central and peripheral systems, with a specific focus on its mechanisms of action in relation to the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems. Additionally, this review aims to offer guidance on clinical assessment and management strategies.

The stellate ganglion and the sympathetic nervous system

The stellate ganglion, situated along the sympathetic chain of the cervical vertebrae, is formed by the fusion of the seventh cervical ganglion and the first thoracic ganglion, which gives it a characteristic star-like shape (13, 14). It is specifically located beneath the transverse process of the C6 vertebra, adjacent to the carotid sheath. This ganglion primarily contains postganglionic sympathetic neurons that innervate the heart. As components of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system, these neurons facilitate local neural coordination independent of higher brain centers. They influence cardiac function through the release of neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine (5, 15). Consequently, the stellate ganglion is intricately linked to the sympathetic nervous system.

Several researchers have put forth a hypothesis suggesting that the proliferation of cardiac sympathetic nerves and excessive innervation of myocardial nerves may contribute to the onset of ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and sudden cardiac death. Experimental findings indicated that the administration of neurotrophic factors into the left stellate ganglion of canines resulted in increased sympathetic nerve sprouting within the myocardium, with a reported 44% incidence of sudden cardiac death among the treated dogs (3). This hypothesis offers a novel perspective on the management of arrhythmias. In a study examining stellate ganglion activity in a canine model, it was observed that stimulation of the left stellate ganglion could induce ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation, ultimately leading to myocardial infarction (16). Furthermore, subcutaneous nerve stimulation in dogs with myocardial infarction resulted in remodeling of the stellate ganglion and a decrease in sympathetic nervous activity (17). Additionally, targeted transient potential modulation in the stellate ganglion represents a significant strategy for arrhythmia treatment. The injection of resin toxin into induced transient receptor potential sympathetic neurons for targeted ablation can mitigate ischemia-induced autonomic imbalance and cardiac electrophysiological instability, thereby preventing ventricular arrhythmias associated with acute myocardial infarction (18).

An essential contributor to the progression of heart failure is the heightened activation of the sympathetic nervous system, with the stellate ganglion serving as a component of this system and a potential target for pharmacological intervention. Researchers demonstrated that the injection of nerve growth factor into the stellate ganglion enhanced cardiac norepinephrine reuptake in a rat model of heart failure, thereby alleviating excessive local sympathetic nerve activation in the hypertrophied heart (19). In a chronic heart failure pig model, it was noted that the stellate ganglion exhibited more frequent, transient, and intense co-fluctuations in information processing and cardiac regulation. The neural specificity associated with the cardiac cycle showed considerable variation, and the relationship between neural network activity and cardiac regulation was influenced by the disease state and the degree of co-fluctuations (20). Furthermore, the administration of leptin into the left stellate ganglion was found to stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in an increased incidence of ischemia-related ventricular arrhythmias (21).

Application of SGB under ultrasound guidance in clinical practice

SGB is a procedure that entails the injection of local anesthetics into the stellate ganglion, located between the C6 and C7 vertebrae, to inhibit the transmission of signals from the ganglion and modulate the sympathetic nerve fibers it supplies (22). Lidocaine and bupivacaine are among the anesthetics frequently utilized in this technique.

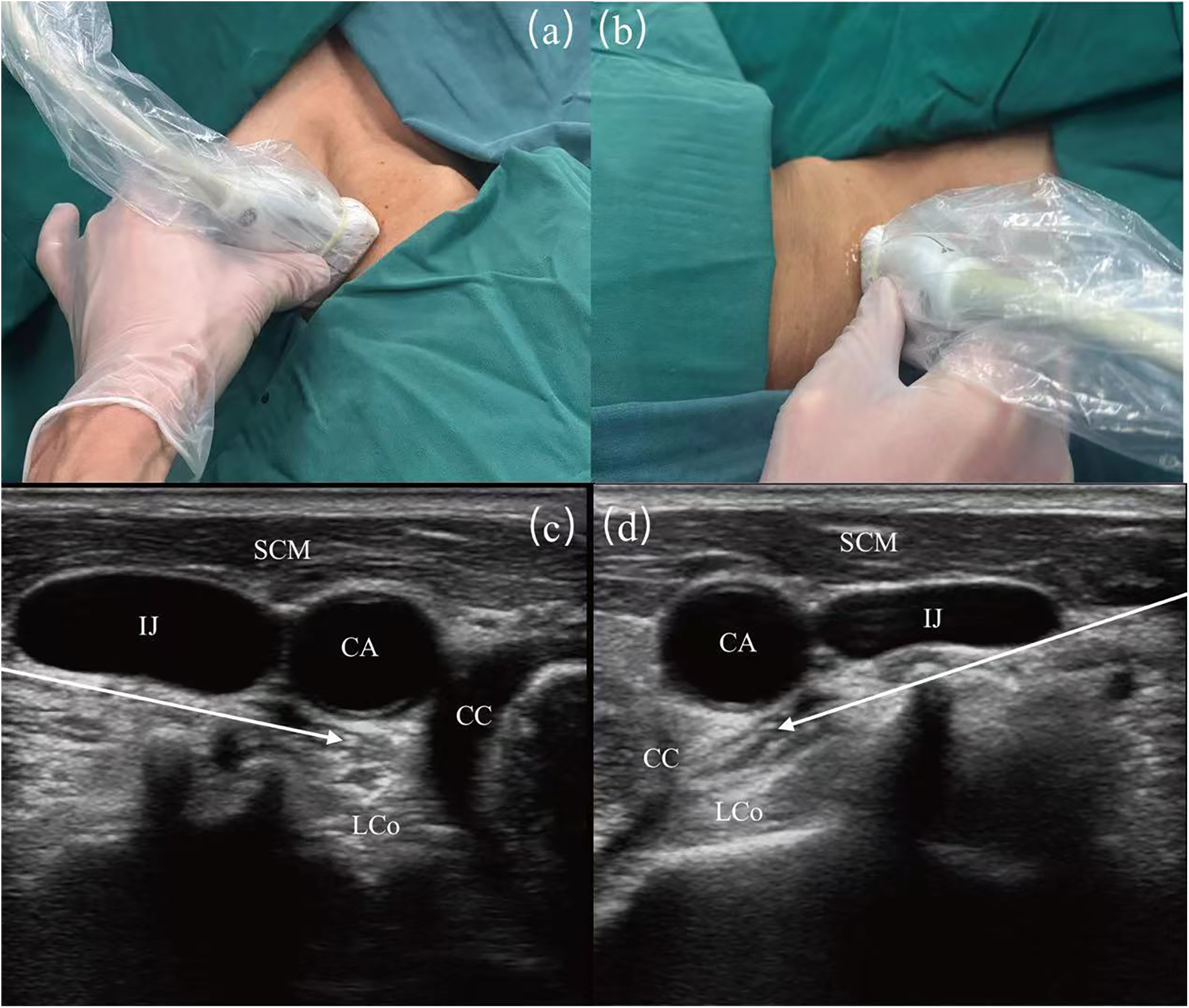

Techniques described for SGB involve anterior paratracheal, lateral, anterolateral, superior, and posterior approaches. Although SGB have been used in clinical practice for more than 70 years, the literature indicates a variable success rate (16%–100%) (23, 24). With ultrasound guidance, SGB procedures have become more accurate and standardized to ensure the accuracy of injection sites (25). Utilizing ultrasound guidance allows for the accurate identification of the appropriate fascial plane, and positioning the needle at the C6 level facilitates the caudal dispersion of the injectate to the stellate ganglion located at the C7-T1 level. This technique enhances the efficacy and precision of sympathetic nerve blocks while utilizing a reduced volume of injectate. Furthermore, ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion blocks improve procedural safety by allowing direct visualization of vascular structures (e.g., inferior thyroid artery, carotid arteries, vertebral artery, carotid sheath) and soft tissue structures (e.g., thyroid gland, esophagus, nerve roots) (Figure 1) (26).

Figure 1

Image guidance for stellate ganglion block (SGB) under ultrasound. (a) Surface ultrasound position diagram of left SGB. (b) Surface ultrasound position diagram of right SGB. (c) Guided diagram for left SGB under ultrasound guidance. (d) Guided diagram for right SGB under ultrasound guidance. SCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle; CA, carotid artery; IJ, internal jugular vein; LCo, longus colli muscle; CC, circular cartilage. The white arrows show the path of the puncture needle, with the arrowheads indicating the location of the stellate ganglion.

Despite the fact that ultrasound-guided techniques can greatly enhance the precision and safety of SGB procedures, complications remain an inevitable aspect of clinical practice. Horner's syndrome, the most common complication post-SGB, is now considered a sign of effective blockade. This syndrome presents with miosis (pupil constriction), ptosis (drooping eyelids), enophthalmos (sunken eyes), reduced or absent sweating on the affected side of the face, conjunctival congestion, facial flushing, erythema of the earlobes, nasal congestion, and elevated skin temperature (22). The higher incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury may be associated with the depth of needle insertion. Other associated complications occur less frequently but still necessitate meticulous management. These include transient loss of consciousness, brachial plexus block, high epidural block, and accidental vascular puncture (27). Obstruction of the vertebral artery by the transverse process at the ganglion of the seventh cervical vertebra often hinders clear visualization using ultrasound. Despite the assistance of ultrasound guidance, inadvertent entry of local anesthetics into the vertebral artery poses a serious risk of complications, including sudden cardiac arrest (28).

Heart

Blocking the stellate ganglion can decrease sinoatrial node discharge frequency, weaken atrioventricular conduction, and raise the ventricular fibrillation threshold due to its close synaptic connections with cardiac nerves. This intervention also tilts the cardiac autonomic nerves balance towards parasympathetic activity, relatively inhibiting sympathetic activity. Consequently, heart rate decreases, myocardial contractility weakens, and myocardial oxygen consumption reduces (29, 30).

SGB also influences ventricular contraction and relaxation. Echocardiogram analysis of 8 healthy individuals revealed a slight impairment in echocardiographic parameters during left SGB-induced ventricular diastole (31). However, this effect is minor and does not hinder ventricular function. Consistent findings from other studies indicate an increase in left ventricular power per beat, cardiac output, and arterial diastolic pressure following SGB administration. Notably, there is no alteration in the systolic or diastolic function of the right ventricle post-SGB (32, 33).

Cardiovascular diseases

Arrhythmias

The treatment of arrhythmias through cardiac denervation is effective, yet the procedure is intricate and fraught with numerous complications, demanding a high level of expertise from cardiac specialists (34, 35). Transdermal sustained SGB can transiently impede the transmission of sympathetic signals to the heart, presenting itself as a potential therapy for cardiac sympathetic denervation and a viable transition (36, 37). Continuous SGB on the left side is particularly effective for ventricular arrhythmias. A case series study involving two centers included 26 patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias who underwent percutaneous continuous SGB, with 59% of patients completely suppressing ventricular arrhythmias (38). Similarly, another multicenter retrospective study analyzed 117 patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias who received SGB treatment, and the results showed that SGB was associated with a reduction in the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias and the need for defibrillation therapy (39). The left SGB significantly increases the threshold for ventricular fibrillation and prolongs the ventricular effective refractory period (40). This provides a simple, rapid, and effective intervention for patients experiencing electrical storms due to rapid recurrence of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, significantly improving patient outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1

| Trial | Type | Sample number | Intervention | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savastano et al. (37) | Case | 1 | Percutaneous SGB | Sustained polymorphic VA |

| Dusi et al. (38) | Case and Review | 26 | Continuous percutaneous SGB | VA |

| Chouairi et al. (39) | Observational | 117 | SGB | VT and VF |

| Kim et al. (12) | Observational | 89 | SGB | HRV |

| Ouyang et al. (76) | RCT | 200 | SGB | Perioperative atrial fibrillation |

| Wu et al. (77) | RCT | 90 | SGB | Postoperative dysrhythmias |

| Liu et al. (25) | RCT | 100 | SGB | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

Representative studies on SGB apply for arrhythmias.

VA, ventricular arrhythmias; VT, ventricular tachycardia; HRV, heart rate variability.

The impact of SGB on heart rate variability varies depending on the side of the procedure. A study involving 89 head and neck pain patients found no significant changes in heart rate variability index following right-sided SGB. In contrast, left-sided SGB led to an increase in high-frequency range power and a decrease in the low-frequency to high-frequency range power ratio, indicating heightened parasympathetic nervous system activity (12).

Myocardial ischemia

Excessive activation of the sympathetic nervous system may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of vascular calcification. Some researchers have found that SGB can improve aortic calcification in rats by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum, which is mediated through the suppression of sympathetic activity and norepinephrine release (41). In a study on myocardial infarction models in rats, it was found that SGB significantly reduced the levels of serum cardiac troponin I and troponin T, alleviated ST segment depression and oxidative stress levels. The right-sided SGB was more effective than the left-sided SGB, indicating thaBt SGB can prevent myocardial damage caused by oxidative stress (42).

In the early 20th century, researchers documented a case involving a patient suffering from severe chronic refractory angina who received SGB treatment, followed by a 34-month follow-up evaluation. The findings suggested that repeated SGB may offer significant benefits in alleviating angina, indicating that further investigation into its clinical application is warranted (43). Subsequent research has indicated that SGB can also be effective in treating ventricular fibrillation resulting from myocardial infarction. In one particular case, a patient with an anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction experienced a worsening condition, resulting in loss of consciousness and absence of pulse. After several unsuccessful attempts at defibrillation and pharmacological treatment, SGB was administered, which ultimately restored basic neurological function and hemodynamic stability, enabling successful emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. While this favorable outcome is likely due to multiple factors, it suggests that sympathetic blockade may serve as a potential adjunctive therapy in cases of sustained pulseless ventricular storm (44). Nonetheless, there remains a scarcity of high-quality studies validating the precise efficacy of SGB in human applications.

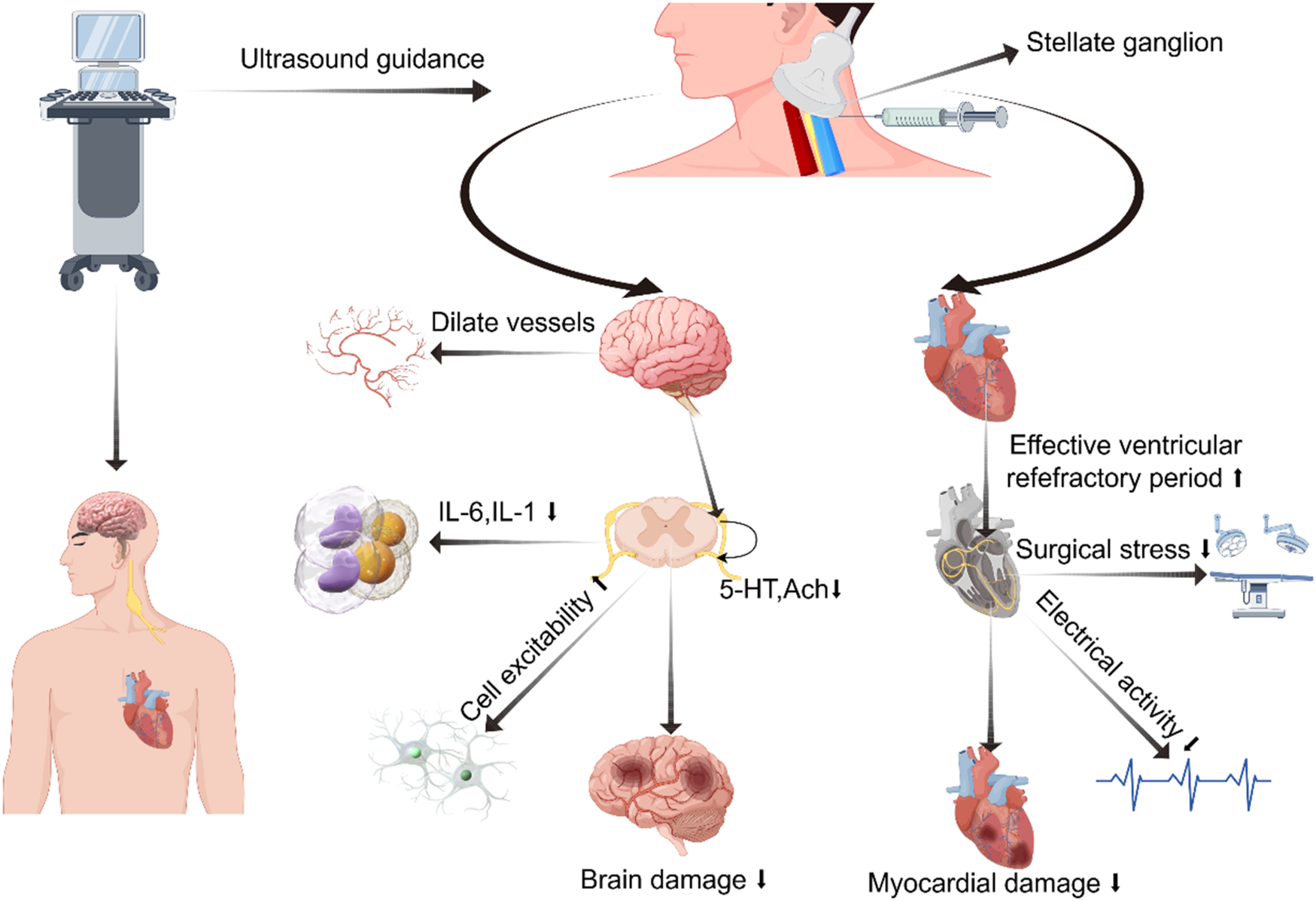

Blood vessels

SGB also has a certain impact on blood pressure. A study on 16 healthy volunteers showed that after SGB, the reflex sensitivity to stress in patients was reduced within 30 min. This may be due not only to autonomic nervous system imbalance but also to the loss of complexity in heart rate and systolic blood pressure variability (Figure 2) (45). However, a case report has suggested that autonomic nervous system dysregulation post-SGB could induce profound hypertension. This occurrence is thought to stem from the spread of local anesthetics through the carotid sheath, causing vagal nerve inhibition. Consequently, this inhibition reduces baroreceptor reflex sensitivity, prompting a compensatory elevation in sympathetic nervous system function (46).

Figure 2

Diagram illustrating potential mechanisms of regulating cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases via stellate ganglion block. Created using Figdraw.

SGB also causes redistribution of blood flow throughout the body. Research has shown that after performing SGB block in rabbits, blood flow to the lower limbs, internal organs, and the non-blocked side is redistributed to the blocked side (47). A study of 52 orthopedic surgery patients found that Doppler ultrasound assessment showed a decrease in brachial artery resistance index and an increase in blood flow after SGB. However, SGB did not alleviate forearm surgery-related pain (48, 49).

Moreover, recent research indicates that multiple SGB can diminish vasomotor symptoms in female patients (e.g., hot flashes). However, the efficacy of this intervention appears to diminish with prolonged use, underscoring the need for further investigation into its enduring mechanisms of action (7, 50).

Brain

The protective effect of SGB on the brain remains a topic of debate, yet it is demonstrating a promising trend. In the 1960s, due to the limited technology then, significant changes in cerebral blood flow were not observed in studies of SGB using nitric oxide quantification methods (51, 52). With technological advancements, researchers employ magnetic resonance imaging and direct injection tracking techniques to assess the impact of SGB on cerebral blood flow by measuring blood flow velocity in the neck vessels. Findings indicate a rise in blood flow in the ipsilateral carotid and vertebral arteries primarily attributed to extracranial blood vessel vasodilation (53). After administering SGB to 19 healthy female volunteers, MRI scans revealed a significant increase in the diameter of extracranial arteries, while intracranial arteries showed no change (Figure 2) (54).

Cerebrovascular related disorders

Among 23 patients with traumatic brain stroke in a retrospective study, multiple bilateral SGB interventions resulted in a notable increase in overall Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory scores at one month post-treatment compared to baseline measurements. Notably, male patients demonstrated a more pronounced initial response than their female counterparts (55).

In patients suffering from subarachnoid hemorrhage, SGB has exhibited beneficial effects in protecting the brain. A preliminary analysis of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage indicated that SGB can alleviate blood flow obstruction in the middle cerebral artery, with effects lasting up to 24 h (56). This suggests that SGB possesses a notable vasodilatory effect on cerebral vasospasm. Similar studies have confirmed these findings (57).

Another randomized controlled study involving 102 patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage showed that SGB reduced levels of early brain injury markers within 7 days postoperatively, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, ET-1, NPY, NSE, and S100β. Additionally, the increase in blood flow in the middle cerebral artery and basilar artery was reduced (58).

Original neurological diseases

Several researchers have conducted preliminary investigations on the regulatory role of SGB in preserving brain function within the neuroendocrine-immune network, with a focus on 50 patients who experienced traumatic brain injury. Post-SGB treatment, a notable decline was observed in IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and NF-κB p65 proteins levels in comparison to the control group. Notably, NF-κB p50 protein levels showed no change, indicating a potential modulation by SGB in neuroendocrine-immune system dysfunction post- traumatic brain injury (TBI) (59). Studies conducted earlier have suggested that SGB can change the distribution of lymphocyte subpopulations and NK cell activity, even if only temporarily (60). After a TBI, dysfunction in the autonomic nervous system of the heart may occur, characterized by increased cell excitability in stellate ganglion neurons and decreased excitability in intracardiac ganglion neurons. This alteration in peripheral cardiac efferent neuron function is thought to be influenced by the modulation of transient A-type K + currents and/or M-type K + currents (61).

SGB has been employed in central post-stroke pain patients, yielding positive results. A case study confirmed the analgesic efficacy of this intervention in a 67-year-old individual experiencing severe paroxysmal spasm-like pain in the right side of the head, upper, and lower limbs due to intractable central post-stroke pain. patient's pain levels decreased after receiving SGB for 7 days, and during a follow-up 9 months later, the patient was found to be pain-free (62).Other researchers have reached comparable conclusions as well (63). Furthermore, SGB has been found to effectively lessen thalamic pain syndrome. Following SGB treatment, a significant reduction in headache, facial, and upper limb pain on the affected side was noted in 2 patients with thalamic pain syndrome (64). Currently, only case reports on central pain are available, underscoring the necessity for additional randomized controlled trials to investigate the mechanism of action of SGB.

Others

SGB is widely utilized in the treatment of various diseases due to its simplicity and minimal risk. Initially intended for alleviating chronic pain syndromes related to the sympathetic nervous system (65, 66), SGB has been shown in previous studies to reduce postoperative opioid consumption in patients undergoing upper limb orthopedic surgery under general anesthesia (67) Clinical trials have shown that SGB alleviates neuralgia in patients with herpes zoster affecting the face and head. After six sessions, patients reported a notable decrease in their VAS pain score, although further investigation is required to elucidate the precise mechanism of action (68).

A prospective study on military personnel demonstrated that SGB reduces anxiety symptoms in PTSD patients and enhances their quality of life (9). SGB has also been shown to improve sleep quality in individuals with sleep disorders. A study following breast cancer patients for 24 weeks revealed that the likelihood of experiencing improved sleep quality was 3.4 (95% CI 1.6–7.2) at week 1 and 4.3 (95% CI 1.9–9.8) at week 24 compared to the beginning (7). By modulating hormone levels in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis related to sleep activity, SGB serves as an alternative therapy to sedatives, potentially enhancing postoperative sleep quality and overall recovery (69).

SGB provides initial advantages for gastrointestinal function as well. Patients with ulcerative colitis who received SGB showed a notable decrease in inflammatory markers within a month, indicating a possible association with SGB's modulation of neuroimmune pathways (70).

Perioperative responses

The role of SGB is important in perioperative cardiovascular management. A study conducted with 20 patients undergoing knee arthroscopy demonstrated that preoperative SGB can mitigate tourniquet-induced hypertension and help stabilize hemodynamic parameters (71). Anesthesiologists have consistently faced a formidable challenge in managing the stress response triggered by endotracheal intubation following anesthesia induction. During a study involving 60 elderly patients slated for elective surgery, it was observed that SGB decreased blood pressure and heart rate reactions post-tracheal intubation, thereby alleviating intraoperative stress responses (72). Similarly, another investigation revealed that preoperative SGB mitigate stress responses during carbon dioxide insufflation in elderly patients, thereby stabilizing hemodynamic parameters (73). Furthermore, a study involving 80 patients undergoing elective surgery for coronary heart disease demonstrated that preoperative SGB could decrease both the frequency and intensity of symptoms associated with coronary heart disease, consequently reducing the overall risk for these patients (74).

Cardiovascular events are more prone to occur in thoracic surgery due to its proximity to the heart, the inflammatory response, incision pain, and mechanical traction. A study on visceral pain in elderly patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung cancer surgery revealed that preoperative SGB reduces intraoperative visceral stress, stabilizes hemodynamics during chest incision, and alleviates visceral pain within 24 h post video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (75).

A study of 200 postoperative lung resection patients receiving SGB prior to surgery demonstrated a notable 7% reduction in atrial fibrillation incidence, as determined through dynamic electrocardiogram analysis conducted during and 24 h post-surgery (76). A separate study involving 90 patients who underwent lung resection revealed that preoperative SGB could decrease the occurrence of postoperative supraventricular tachycardia by around 20% within 48 h following surgery, while also substantially extending the duration of postoperative sleep for the patients (77). An analysis of 50 patients demonstrated that SGB did not have a significant effect on lung function (78), thus ensuring the safety of thoracic surgery for these patient.

Moreover, there is a lack of research investigating the potential of SGB to mitigate perioperative myocardial ischemia and injury, thereby decreasing the occurrence of perioperative myocardial infarction. Some scholars have published a study protocol regarding the occurrence of myocardial injury following laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer. However, this study reported no instances of myocardial injury during surgery following the administration of SGB postoperatively (79). The clinical value of SGB in perioperative cardiovascular management may be attributed to its capacity to modulate sympathetic nervous activity, improve hemodynamics, and reduce oxidative stress. Consequently, SGB presents potential clinical efficacy in perioperative cardiovascular management.

Conclusion

In this narrative review, we have summarized the modulating effects of SGB on the central and peripheral focus on cardiovascular systems and related diseases. SGB blocked the transmission of sympathetic nerve signals to alleviate various cardiac arrhythmias and cardiovascular diseases. At the same time, it also reduced cardiac and cerebral infarction and primary diseases through anti-inflammatory pathways and inhibiting oxidative stress. Additionally, the narrative detailed the influence of SGB on stress responses and multiple postoperative outcomes among surgical patients.

Nonetheless, SGB also produced vagus nerve stimulation effects, encompassing insomnia, depression, and cognitive impairment, in addition to alleviating pain. Perhaps it would be beneficial to refocus our inquiry on whether SGB can produce effects resembling those of the parasympathetic nervous system, a subject requiring further investigation. Therefore, high-quality clinical studies studies are needed to support the administration of SGB for the central and peripheral systems.

Statements

Author contributions

ZZ: Writing – original draft. MA: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Zhejiang Province Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project - Anesthesiology Department (2023-ZJZK-001).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Guyenet PG Stornetta RL Souza GMPR Abbott SBG Brooks VL . Neuronal networks in hypertension recent advances. Hypertension. (2020) 76:300–11. 10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.14521

2.

Singh RB Hristova K Fedacko J El-Kilany G Cornelissen G . Chronic heart failure: a disease of the brain. Heart Fail Rev. (2018) 24:301–7. 10.1007/s10741-018-9747-3

3.

Chen P-S Chen LS Cao J-M Sharifi B Karagueuzian HS Fishbein MC . Sympathetic nerve sprouting, electrical remodeling and the mechanisms of sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc Res. (2001) 50:409–16. 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00308-4

4.

Kimura K Ieda M Fukuda K . Development, maturation, and transdifferentiation of cardiac sympathetic nerves. Circ Res. (2012) 110:325–36. 10.1161/circresaha.111.257253

5.

Hoang JD Salavatian S Yamaguchi N Swid MA Vaseghi M . Cardiac sympathetic activation circumvents high-dose beta blocker therapy in part through release of neuropeptide Y. J Clin Invest Insight. (2020) 5:e135519. 10.1172/jci.insight.135519

6.

Toyama T Hoshizaki H Seki R Isobe N Adachi H Naito S et al Efficacy of carvedilol treatment on cardiac function and cardiac sympathetic nerve activity in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: comparison with metoprolol therapy. J Nucl Med. (2003) 44:1604–11.

7.

Haest K Kumar A Van Calster B Leunen K Smeets A Amant F et al Stellate ganglion block for the management of hot flashes and sleep disturbances in breast cancer survivors: an uncontrolled experimental study with 24 weeks of follow-up. Ann Oncol. (2011) 23:1449–54. 10.1093/annonc/mdr478

8.

Yu B Hou S Xing Y Jia Z Luo F . Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block for the treatment of migraine in elderly patients: a retrospective and observational study. Headache. (2023) 63:763–70. 10.1111/head.14537

9.

Rae Olmsted KL Bartoszek M Mulvaney S McLean B Turabi A Young R et al Effect of stellate ganglion block treatment on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:130. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3474

10.

Lee M-C Bartuska A Chen J Kim RK Jaradeh S Mihm F . Stellate ganglion block catheter for paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity: calming the ‘neuro-storm’. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (2023) 48:522–5. 10.1136/rapm-2023-104399

11.

Lee YS Wie C Pew S Kling JM . Stellate ganglion block as a treatment for vasomotor symptoms: clinical application. Cleve Clin J Med. (2022) 89:147–53. 10.3949/ccjm.89a.21032

12.

Kim JJ Chung RK Lee HS Han JI . The changes of heart rate variability after unilateral stellate ganglion block. Korean J Anesthesiol. (2010) 58:56–56. 10.4097/kjae.2010.58.1.56

13.

Kizilay H Cakici H Kilinc E Firat T Kuru T Sahin AA . Effects of stellate ganglion block on healing of fractures induced in rats. Biomed Res Int. (2020) 2020:1–7. 10.1155/2020/4503463

14.

Wittwer ED Radosevich MA Ritter M Cha Y-M . Stellate ganglion blockade for refractory ventricular arrhythmias: implications of ultrasound-guided technique and review of the evidence. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2019) 34:2245–52. 10.1053/j.jvca.2019.12.015

15.

Pardini BJ Lund DD Schmid PG . Organization of the sympathetic postganglionic innervation of the rat heart. J Auton Nerv Syst. (1989) 28:193–201. 10.1016/0165-1838(89)90146-x

16.

Zhou S Jung B-C Tan AY Trang VQ Gholmieh G Han S-W et al Spontaneous stellate ganglion nerve activity and ventricular arrhythmia in a canine model of sudden death. Heart Rhythm. (2007) 5:131–9. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.007

17.

Yuan Y Zhao Y Wong J Tsai W-C Jiang Z Kabir RA et al Subcutaneous nerve stimulation reduces sympathetic nerve activity in ambulatory dogs with myocardial infarction. Heart Rhythm. (2020) 17:1167–75. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.02.006

18.

Zhou M Liu Y He Y Xie K Quan D Tang Y et al Selective chemical ablation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 expressing neurons in the left stellate ganglion protects against ischemia-induced ventricular arrhythmias in dogs. Biomed Pharmacother. (2019) 120:109500–109500. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109500

19.

Kreusser MM Haass M Buss SJ Hardt SE Gerber SH Kinscherf R et al Injection of nerve growth factor into stellate ganglia improves norepinephrine reuptake into failing hearts. Hypertension. (2005) 47:209–15. 10.1161/01.hyp.0000200157.25792.26

20.

Gurel NZ Sudarshan KB Hadaya J Karavos A Temma T Hori Y et al Metrics of high cofluctuation and entropy to describe control of cardiac function in the stellate ganglion. Elife. (2022) 11:e78520. 10.7554/elife.78520

21.

Yu L Wang Y Zhou X Huang B Wang M Li X et al Leptin injection into the left stellate ganglion augments ischemia-related ventricular arrhythmias via sympathetic nerve activation. Heart Rhythm. (2017) 15:597–606. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.12.003

22.

Serna-Gutiérrez J . Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. (2015) 43:278–82. 10.1016/j.rcae.2014.09.004

23.

Kakazu CZ Julka I . Stellate ganglion blockade for acute postoperative upper extremity pain. Anesthesiology. (2005) 102:1288–9. 10.1097/00000542-200506000-00039

24.

Ateş Y Asik I Özgencil E Açar Hİ Yağmurlu B Tekdemir İ . Evaluation of the longus colli muscle in relation to stellate ganglion block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (2009) 34:219–23. 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181a32a02

25.

Liu T Zhang J Liang J Luo R Zhang Z Li J et al Effect of stellate ganglion block on preventing atrial fibrillation after esophagectomy: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Drug Des Dev Ther. (2025) 19:7481–92. 10.2147/dddt.s538004

26.

Narouze S . Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block: safety and efficacy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. (2014) 18:1–5. 10.1007/s11916-014-0424-5

27.

Goel V Patwardhan AM Ibrahim M Howe CL Schultz DM Shankar H . Complications associated with stellate ganglion nerve block: a systematic review. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (2019) 44:669–78. 10.1136/rapm-2018-100127

28.

Rastogi S Tripathi S . Cardiac arrest following stellate ganglion block performed under ultrasound guidance. Anaesthesia. (2010) 65:1042. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06487.x

29.

Leftheriotis D Flevari P Kossyvakis C Katsaras D Batistaki C Arvaniti C et al Acute effects of unilateral temporary stellate ganglion block on human atrial electrophysiological properties and atrial fibrillation inducibility. Heart Rhythm. (2016) 13:2111–7. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.06.025

30.

Feigin G Figueroa SV Englesakis MF D’Souza R Hoydonckx Y Bhatia A . Stellate ganglion block for non-pain indications: a scoping review. Pain Med. (2023) 24:775–81. 10.1093/pm/pnad011

31.

Schlack W Dinter W . Haemodynamic effects of a left stellate ganglion block in ASA I patients. An echocardiographic study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2000) 17:79–84. 10.1046/j.1365-2346.2000.00606.x

32.

Lobato EB Kern KB Paige GB Brown M Sulek CA . Differential effects of right versus left stellate ganglion block on left ventricular function in humans: an echocardiographic analysis. J Clin Anesth. (2000) 12:315–8. 10.1016/s0952-8180(00)00158-6

33.

de la Vega Costa KP Perez MAG Roqueta C Fischer L . Effects on hemodynamic variables and echocardiographic parameters after a stellate ganglion block in 15 healthy volunteers. Auton Neurosci. (2016) 197:46–55. 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.04.002

34.

Xiong L Liu Y Zhou M Wang G Quan D Shen C et al Targeted ablation of cardiac sympathetic neurons improves ventricular electrical remodelling in a canine model of chronic myocardial infarction. EP Europace. (2018) 20:2036–44. 10.1093/europace/euy090

35.

Liu S Yu X Luo D Qin Z Wang X He W et al Ablation of the ligament of marshall and left stellate ganglion similarly reduces ventricular arrhythmias during acute myocardial infarction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2018) 11:e005945. 10.1161/circep.117.005945

36.

Witt CM Bolona L Kinney MO Moir C Ackerman MJ Kapa S et al Denervation of the extrinsic cardiac sympathetic nervous system as a treatment modality for arrhythmia. EP Europace. (2017) 19:1075–83. 10.1093/europace/eux011

37.

Savastano S Pugliese L Baldi E Dusi V Tavazzi G De Ferrari GM . Percutaneous continuous left stellate ganglion block as an effective bridge to bilateral cardiac sympathetic denervation. EP Europace. (2020) 22:606. 10.1093/europace/euaa007

38.

Dusi V Angelini F Baldi E Toscano A Gravinese C Frea S et al Continuous stellate ganglion block for ventricular arrhythmias: case series, systematic review, and differences from thoracic epidural anaesthesia. EP Europace. (2024) 26:euae074. 10.1093/europace/euae074

39.

Chouairi F Rajkumar K Benak A Qadri Y Piccini JP Mathew J et al A multicenter study of stellate ganglion block as a temporizing treatment for refractory ventricular arrhythmias. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2024) 10:750–8. 10.1016/j.jacep.2023.12.012

40.

Savastano S Schwartz PJ . Blocking nerves and saving lives: left stellate ganglion block for electrical storms. Heart Rhythm. (2022) 20:1039–47. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2022.11.025

41.

Hao W Yang R Yang Y Jin S Li Y Yuan F et al Stellate ganglion block ameliorates vascular calcification by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress. Life Sci. (2017) 193:1–8. 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.12.002

42.

Wei N Chi M Deng L Wang G . Antioxidation role of different lateral stellate ganglion block in isoproterenol-induced acute myocardial ischemia in rats. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (2017) 42:588–99. 10.1097/aap.0000000000000647

43.

Chester M Hammond C Leach A . Long-term benefits of stellate ganglion block in severe chronic refractory angina. PAIN. (2000) 87:103–5. 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00270-0

44.

Margus C Correa A Cheung W Blaikie E Kuo K Hockensmith A et al Stellate ganglion nerve block by point-of-care ultrasonography for treatment of refractory infarction-induced ventricular fibrillation. Ann Emerg Med. (2019) 75:257–60. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.07.026

45.

Taneyama C Goto H . Fractal cardiovascular dynamics and baroreflex sensitivity after stellate ganglion block. Anesth Analg. (2009) 109:1335–40. 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b018d8

46.

Kimura T Nishiwaki K Yokota S Komatsu T Shimada Y . Severe hypertension after stellate ganglion block. Br J Anaesth. (2005) 94:840–2. 10.1093/bja/aei134

47.

Terakawa Y Ichinohe T Kaneko Y . Redistribution of tissue blood flow after stellate ganglion block in the rabbit. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (2009) 34:553–6. 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181b4c505

48.

Li G Zhang C Li Y Yang J Wu J Shao Y et al Optogenetic vagal nerve stimulation attenuates heart failure by limiting the generation f monocyte-derived inflammatory CCRL2+ macrophages. Immunity. (2025) 58(7):1847–61. 10.1016/j.immuni.2025.06.003

49.

Kim MK Yi MS Park PG Kang H Lee JS Shin HY . Effect of stellate ganglion block on the regional hemodynamics of the upper extremity: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. (2017) 126:1705–11. 10.1213/ane.0000000000002528

50.

Walega DR Rubin LH Banuvar S Shulman LP Maki PM . Effects of stellate ganglion block on vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. (2014) 21:807–14. 10.1097/gme.0000000000000194

51.

Scheinberg P . Cerebral blood flow in vascular disease of the brain; with observations on the effects of stellate ganglion block. Am J Med. (1950) 8:139–47. 10.1016/0002-9343(50)90354-8

52.

Kety SS . Stellate ganglion blockade and the cerebral circulation. Anesthesiology. (1959) 20:697. 10.1097/00000542-195909000-00023

53.

Nitahara K . Blood flow velocity changes in carotid and vertebral arteries with stellate ganglion block: measurement by magnetic resonance imaging using a direct bolus tracking method. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (1998) 23:600–4. 10.1016/s1098-7339(98)90088-8

54.

Kang C-K Oh S-T Chung RK Lee H Park C-A Kim Y-B et al Effect of stellate ganglion block on the cerebrovascular system. Anesthesiology. (2010) 113:936–44. 10.1097/aln.0b013e3181ec63f5

55.

Mulvaney SW Lynch JH Olmsted KLR Mahadevan S Dineen KJ . The successful use of bilateral 2-level ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block to improve traumatic brain injury symptoms: a retrospective analysis of 23 patients. Mil Med. (2024) 189:e2573–7. 10.1093/milmed/usae193

56.

Wendel C Scheibe R Wagner S Tangemann W Henkes H Ganslandt O et al Decrease of blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery after stellate ganglion block following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a potential vasospasm treatment? J Neurosurg. (2019) 133:773–9. 10.3171/2019.5.jns182890

57.

Wendel C Oberhauser C Schiff J Henkes H Ganslandt O . Stellate ganglion block and intraarterial spasmolysis in patients with cerebral vasospasm: a retrospective cohort study. Neurocrit Care. (2023) 40:603–11. 10.1007/s12028-023-01762-w

58.

Zhang J Nie Y Pang Q Zhang X Wang Q Tang J . Effects of stellate ganglion block on early brain injury in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a randomised control trial. BMC Anesthesiol. (2021) 21:23. 10.1186/s12871-020-01215-3

59.

Yang X Shi Z-Q Li X Li J . Impacts of stellate ganglion block on plasma NF-κB and inflammatory factors of TBI patients. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2015) 8(9):15630–8.

60.

Yokoyama M Nakatsuka H Itano Y Hirakawa M . Stellate ganglion block modifies the distribution of lymphocyte subsets and natural-killer cell activity. Anesthesiology. (2000) 92:109. 10.1097/00000542-200001000-00021

61.

Oh J-W Lee C-K Whang K Jeong S-W . Functional plasticity of cardiac efferent neurons contributes to traumatic brain injury-induced cardiac autonomic dysfunction. Brain Res. (2021) 1753:147257. 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.147257

62.

Liu Q Zhong Q Tang G Ye L . Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block for central post-stroke pain: a case report and review. J Pain Res. (2020) 13:461–4. 10.2147/jpr.s236812

63.

Purohit G Kumar A Sharma RS Bhandari B Mahiswar A Singh GK et al Stellate ganglion blocks for refractory central poststroke pain: a case series. A A Pract. (2023) 17:e01665. 10.1213/xaa.0000000000001665

64.

Wilkinson AJ Yang A Chen GH . Stellate ganglion block to mitigate thalamic pain syndrome of an oncological origin. Pain Pract. (2023) 24:231–4. 10.1111/papr.13275

65.

Luo Q Wen S Tan X Yi X Cao S . Stellate ganglion intervention for chronic pain: a review. Ibrain. (2022) 8:210–8. 10.1002/ibra.12047

66.

Tian Y Hu Y Hu T Liu T An G Li J et al Stellate ganglion block therapy for complex regional pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician. (2024) 27:175–84.

67.

Kumar N Thapa D Gombar S Ahuja V Gupta R . Analgesic efficacy of pre-operative stellate ganglion block on postoperative pain relief: a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. (2014) 69:954–60. 10.1111/anae.12774

68.

Wang C Yuan F Cai L Lu H Chen G Zhou J . Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block combined with extracorporeal shock wave therapy on postherpetic neuralgia. J Healthc Eng. (2022) 2022:1–5. 10.1155/2022/9808994

69.

Zhang X Huang X Yang J . Efficacy of stellate ganglion block on postoperative sleep disorder: a systematic review. Asian J Surg. (2024) 02117–1(24):S1015–9584. 10.1016/j.asjsur.2024.09.072

70.

Zhao H-Y Yang G-T Sun N-N Kong Y Liu Y-F . Efficacy and safety of stellate ganglion block in chronic ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. (2017) 23:533. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i3.533

71.

Arai YP Ogata J Matsumoto Y Yonemura H Kido K Uchida T et al Preoperative stellate ganglion blockade prevents tourniquet-induced hypertension during general anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2004) 48:613–8. 10.1111/j.0001-5172.2004.00389.x

72.

Chen Y-Q Jin X-J Liu Z-F Zhu M-F . Effects of stellate ganglion block on cardiovascular reaction and heart rate variability in elderly patients during anesthesia induction and endotracheal intubation. J Clin Anesth. (2015) 27:140–5. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2014.06.012

73.

Chen Y-Q Xie Y-Y Wang B Jin X-J . Effect of stellate ganglion block on hemodynamics and stress responses during CO2-pneumoperitoneum in elderly patients. J Clin Anesth. (2017) 37:149–53. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.12.003

74.

Zheng H . Analysis of the necessity of stellate ganglion block after anesthesia to reduce the risk of cardiovascular accidents in coronary heart disease. J Clin Nurs Res. (2024) 8:235–40. 10.26689/jcnr.v8i7.7876

75.

Xiang X Wu Y Fang Z Tang X Wu Y Zhou J et al Stellate ganglion block for visceral pain in elderly patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic lung cancer surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. Int J Surg. (2024) 110:6996–7002. 10.1097/js9.0000000000001867

76.

Ouyang R Li X Wang R Zhou Q Sun Y Lei E . Effect of ultrasound-guided right stellate ganglion block on perioperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing lung lobectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Braz J Anesthesiol. (2020) 70:256–61. 10.1016/j.bjane.2020.04.024

77.

Wu C-N Wu X-H Yu D-N Ma W-H Shen C-H Cao Y . A single-dose of stellate ganglion block for the prevention of postoperative dysrhythmias in patients undergoing thoracoscopic surgery for cancer. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2020) 37:323–31. 10.1097/eja.0000000000001137

78.

Kim W-J Park HS Yi MS Koo G-H Shin H-Y . Evaluation of lung function and clinical features of the ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block with 2 different concentrations of a local anesthetic. Anesth Analg. (2017) 124:1311–6. 10.1213/ane.0000000000001945

79.

Hu Z Li W Zhao G Liang C Li K . Postoperative stellate ganglion block to reduce myocardial injury after laparoscopic radical resection for colorectal cancer: protocol for a randomised trial. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e069183. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069183

Summary

Keywords

stellate ganglion block, sympathetic nervous system, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, perioperative stress response

Citation

Zhang Z and An M (2025) The potential role of stellate ganglion block in impacting the central and peripheral systems: a narrative review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1706435. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1706435

Received

16 September 2025

Revised

25 October 2025

Accepted

07 November 2025

Published

20 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Stepan Havranek, Charles University, Czechia

Reviewed by

Zhiling Guo, University of California, Irvine, United States

Taifu Hou, Luohe Medical College, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang and An.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Mingzi An anmingzizi@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.