- 1Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Amsterdam University Medical Center Location AMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

- 4Aortic Institute at Yale-New Haven Hospital, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

Background: In patients with thoracic aortopathy post-operative recovery can be complicated by a lack of consistent, clear communication and guidance. Despite the growing recognition of these challenges, the specific needs of patients undergoing aortic surgery, especially across different ethnic groups, remain insufficiently explored. This study aims to examine the peri-operative course in thoracic aortopathy in order to identify the specific needs of the patients, particularly across ethnic groups.

Methods: This cross-sectional, retrospective study included patients who underwent aortic surgery between 2000 and 2023. Patients were asked to complete questionnaires assessing various parts of the pre-, peri-, and (long term) post-operative course. Results were compared between ethnic majority and ethnic minority patients, with further sub-categorization based on the type of aortopathy (aortic dissection vs. thoracic aortic aneurysm). Binary regression models were used, adjusted for age, sex, and follow-up duration when comparing aortopathy types, and additionally for aortic dissection diagnosis when comparing ethnic groups.

Results: A total of 189 patients (174 ethnic majority, 15 minorities) were included. Of these, 115 had type A aortic dissection and 74 had a thoracic aortic aneurysm. Ethnic minority patients showed higher rates of post-operative anxiety (20.0% vs. 5.4%). Minority patients also reported less clarity in post-operative information (p = 0.035). Acute aortic dissection patients reported lower clarity of pre-operative information (7.0 vs. 9.0, p = 0.003) and worse understanding of recovery expectations before surgery (p < 0.001).

Conclusion: This study highlights the critical importance of pre- and post-operative education in thoracic aortopathy patients. Ethnic disparities in recovery experiences exist, particularly in the domains of post-operative anxiety and communication. Our findings highlight the need for tailored post-operative guidance in order to improve recovery outcomes, and ensure more equitable care.

1 Introduction

Thoracic aortopathy encompasses various aortic diseases including a thoracic aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection (1). In patients with thoracic aortopathy life-saving surgical intervention is needed to reduce the high mortality rates (1). Prior research has demonstrated that patients who undergo aortic surgery frequently face significant challenges in their physical, mental, and emotional well-being post-operatively (2, 3). These challenges often require ongoing medical supervision and rehabilitation. However, post-operative recovery can be complicated by a lack of consistent, clear communication and guidance (4–6).

Given the complexity of thoracic aortopathy and the high-risk surgical intervention it entails, clear pre- and post-operative instructions are essential to maximise post-operative outcomes. In particular, a number of studies indicate that thorough pre-operative education regarding the procedure and any possible risks might help lower anxiety and improve the recovery trajectory (7–10). Without proper education on managing their recovery at home, patients may struggle to understand how to navigate the challenges of daily life, which can hinder their overall recovery trajectory.

Over the past decade, ethnic disparities in healthcare have become an increasingly important topic. Many studies have highlighted the impact of ethnicity on access to care, treatment outcomes, and post-operative recovery trajectories (11–13). While ethnicity is primarily a social construct encompassing shared origin, language, and cultural norms, belonging to an ethnic minority has been associated with disparities in healthcare experiences and outcomes (14). The leading hypothesis for these disparities is that they arise from a complex synergy of genetic predisposition, socioeconomic status, and healthcare access (15). Research has also shown that ethnic background can influence post-operative satisfaction in various surgical fields including orthopedic and bariatric surgery, particularly in terms of perceived recovery and rehabilitation outcomes (16, 17). Nonetheless, to our knowledge, studies on the pre- and post-operative course among ethnic groups with thoracic aortopathy have not yet been conducted.

Taken together, these findings raise important questions on pre- and post-operative experiences in thoracic aortopathy and how these may differ among ethnic populations undergoing thoracic aortic surgery. Therefore, in this study we aim to examine the pre- and post operative course in thoracic aortopathy in order to identify the specific needs of the patients. Additionally, we will investigate whether recovery experiences differ across ethnic groups to better support these patients. By identifying potential disparities in perioperative management and recovery, we seek to provide insights that may contribute to more personalized and equitable healthcare strategies.

2 Methods

2.1 Ethical considerations

The ethical standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice were followed in the conduct of this investigation, ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of all collected data. The Medical Ethical Committee of the Leiden University Medical Center reviewed and approved our study protocol. Our study protocol was covered under the IHLCN biobank protocol, with assigned reference number: B21.051/MS/ms, and acceptance date 31-01-2024. Patients were asked to sign informed consent forms and could withdraw their participation at any given moment.

2.2 Patient selection

This study assessed the pre-, peri- and (long term) post-operative course among ethnic groups in aortopathy. Patients records from the Amsterdam University Medical Center (AUMC) and the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) between January 2000 to January 2023 were assessed and selected after surgical repair for a thoracic aortic aneurysm or a type a aortic dissection. These patients were identified and were contacted digitally to complete questionnaires designed to provide insights into their recovery experiences. Two reminders were sent, one and two weeks after the initial contact. Specific patient characteristics were retrospectively obtained through digital patient records, after inclusion in our study. Inclusion criteria were age >18 years and a confirmed diagnosis of aortopathy. There were no specific exclusion criteria besides not being able to complete the entire questionnaire.

2.3 Questionnaire

A questionnaire was developed to assess various aspects of the recovery period (Supplementary File I). The questionnaire was available in both Dutch and English.

2.3.1 Patient demographics

Firstly, the questionnaire collected demographic patient data, including age, sex, weight in kg, height in cm, highest level of education and current employment. The ethnicity and gender of patients were based on recommendations for standardized collection of diversity data by the Joint Commitment for Action on Inclusion and Diversity in Publishing (18, 19). Patients who self-identified as non-white were classified as belonging to an ethnic minority group. (Supplementary File I).

2.3.2 Anxiety

Following, the level of post-surgical anxiety was assessed using the Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire (20). This questionnaire contains seven questions. The presence of anxiety can be determined based on the responses to these questions. Each question is assigned a sub-score from 0–3, where 0 indicates not experiencing a certain complaint, and 3 indicates experiencing a certain complaint nearly every day. These seven sub-scores were then summed to form the GAD-7 total score, ranging from 0–21, with higher scores indicating a higher severity of generalized anxiety. Scores from 0–4 indicated the presence of minimal anxiety. Scores from 5–9 indicated mild anxiety. Scores from 10–14 indicated moderate anxiety. Lastly, scores from 15–21 indicated severe anxiety.

2.3.3 Depression

Furthermore, the presence of depression at follow-up was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) questionnaire (21). This questionnaire consists of nine questions which determines the presence and severity of depression in patients. Similar to the previous questionnaire, the questions are all assigned a sub-score from 0–3, which similar ranking. These subscores were then also summed and the final scores, ranging from 0–27, were then used to determine the presence and severity of depression. Scores from 0–4 indicated the presence of minimal depression. Scores from 5–9 indicated mild depression. Scores from 10–14 indicated moderate depression. Scores from 15–19 indicated moderately severe depression. Lastly, scores from 20–27 indicated severe anxiety.

2.3.4 Preoperative anxiety

Additionally, preoperative anxiety was assessed by asking patients to look back at the time before their surgical intervention and answer the questions from the Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) questionnaire (22). Although this questionnaire is intended for use before surgery, in this study we applied it retrospectively to explore pre-operative anxiety, particularly among patients of ethnic minority descent, as previous research in this population is limited. This questionnaire consists of six statements that patients were asked to rate. This questionnaire assesses the presence of anxiety related to the surgical intervention that patients have had. Patients had to rate their agreement in regard to these statements from 1 (not at all), to 5 (extremely). To determine procedural anxiety the responses to statements 1, 2, 4 & 5 were summed. Scores from 0–9 indicated no procedural anxiety. Scores from 10–12 indicated the presence of procedural anxiety. Scores from 13–20 indicated high levels of procedural anxiety. To determine the need for information about the procedure, the responses to the statements 3 & 6 were summed. Scores from 0–4 indicated no need for information. Scores from 5–7 indicated that patients had an average need for information. Scores of 8–10 indicated a high need of information.

2.3.5 Pre- and post-operative care assessment

Lastly, patients were asked to rate their received care across various domains on a scale from 1–10, with 1 being the lowest and 10 the highest. Additionally, they were asked about the way they were informed, their understanding of the recovery period before surgery, and the usefulness of the informational material they received. (Supplementary File I).

2.4 Retrospectively obtained data

In order to comprehensively understand the pre- and post-operative course in thoracic aortopathy, the questionnaire was complemented with patient characteristics at event, obtained from digital patient records. This data included whether patients had a thoracic aneurysm or a type A aortic dissection, the pre-operative weight in kg, height in cm, the aortic diameter at event, the aortic valve morphology, the occurrence of a complication during the recovery period, and lastly, the date of surgical intervention, in order to determine the follow-up time in years.

2.5 Statistical analysis

To summarize the baseline characteristics of post-dissection patients, descriptive statistics were employed. Variables were assessed in terms of distribution; normally distributed continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas non-normally distributed continuous data are presented as median and interquartile range. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and proportions. Missing data was handled using complete case analysis. Primary outcomes of this study were patient-reported scores from validated questionnaires. Secondary outcomes included responses to questions on patient experience and overall satisfaction with the received care.

In addition to the comparison of ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands to the ethnic majority (European-Caucasian), disparities between patients with a thoracic aortic aneurysm and type A aortic dissection were also analyzed. To compare the findings between the groups we used a logistical regression model. A univariable approach was first used to assess all individual baseline characteristics. Following, we used a multivariable model when assessing the care evaluation. To compare patients with a thoracic aortic aneurysm to those with a type A aortic dissection, we adjusted for sex, age, and follow-up time. To compare ethnic majority patients to ethnic minority patients, we adjusted for age, sex, follow-up time, and diagnosis of a type A aortic dissection. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 30.0.

3 Results

3.1 Study population

This study assessed the pre- and post-operative course among ethnic groups in aortopathy. Patients records from AUMC and the LUMC were studied between January 2000 to January 2023. These patients had all undergone surgical repair for a thoracic aneurysm or a type A aortic dissection. After initial screening, the study cohort included 1,212 patients. Of this cohort, contact information was only available in 682 patients. One hundred and four patients of this group were deceased, leaving 578 patients who received the request to complete the digital questionnaire. Survey responses were received from 189 patients, making the response rate 32.7% (Figure 1).

3.2 Pre-operative characteristics

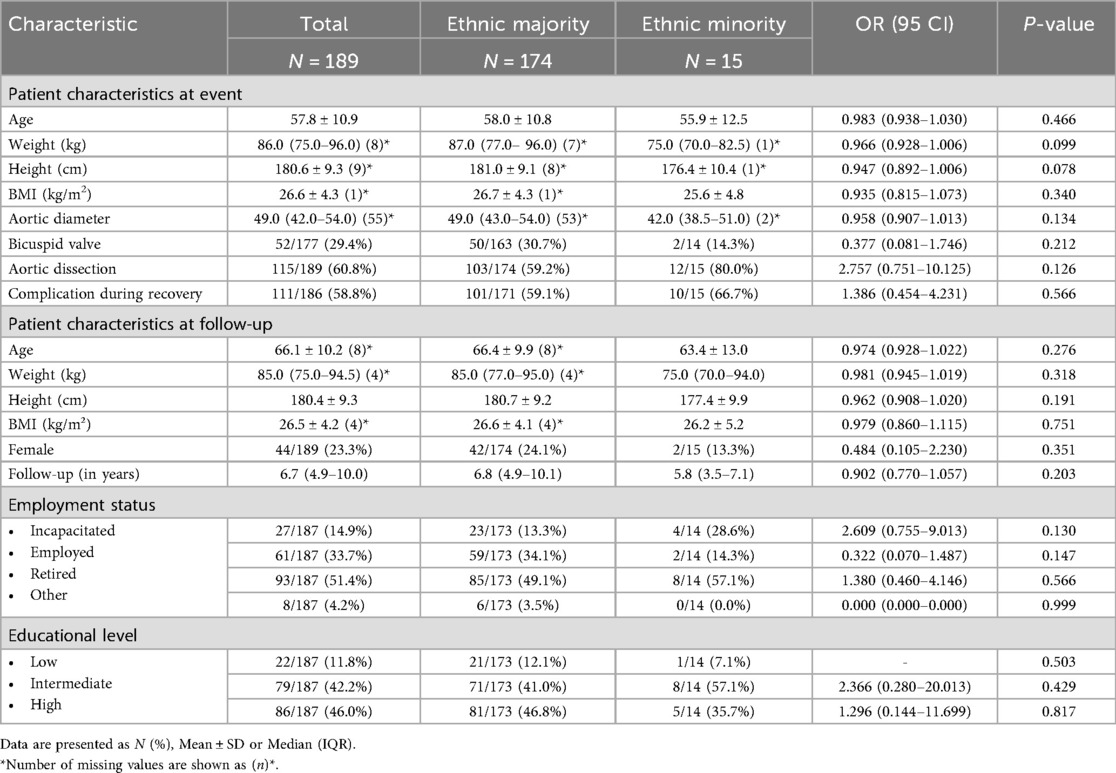

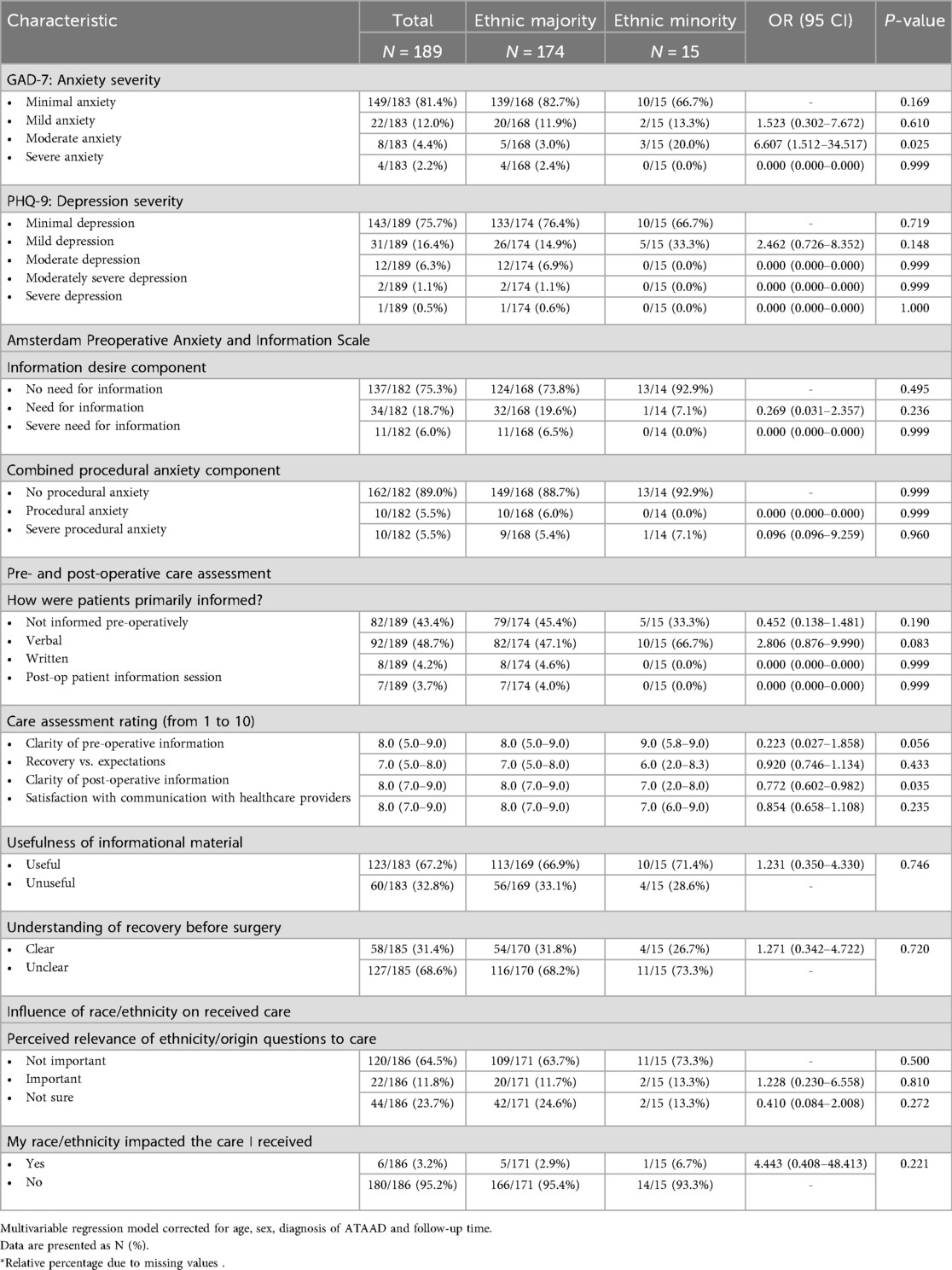

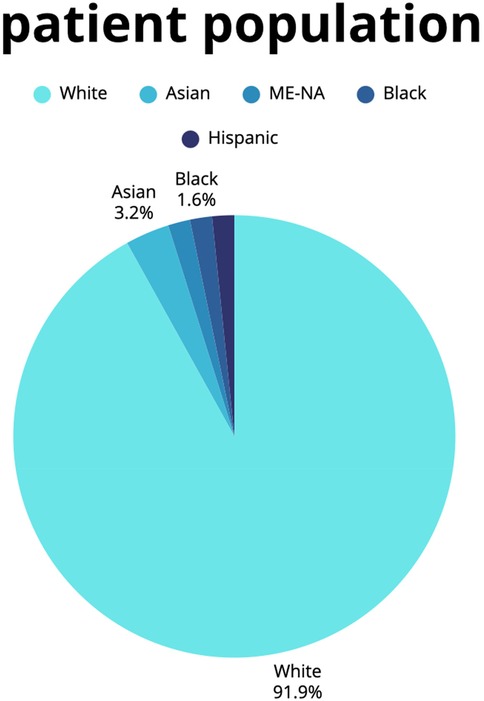

Our study population, consisting of 189 patients was subdivided into an ethnic majority group (n = 174) and ethnic minority group (n = 15), which resembles the ethnic distribution of the Dutch population (23). Figure 2 shows the distribution of ethnic background of the patients within our cohort. Of the entire cohort, 115 patients (60.8%) had undergone surgical repair for a type A aortic dissection, and 74 patients (39.2%) had undergone repair for a thoracic aortic aneurysm. In the entire cohort of 189 patients, 44 patients (23.3%) were female and the mean age was 57.8 ± 10.9 at time of intervention. The BMI at event in patients with thoracic aortopathy was 26.6 ± 4.3. In terms of clinical presentation 52 patients (29.4%) presented with a bicuspid valve and the median aortic diameter was 49.0 (42.0–54.0). A bicuspid aortic valve was 6 times more prevalent in the aneurysm group as compared to the dissection patients (10.4% [aneurysm (a)] vs. 64.5% [dissection (d)]; OR 0.064 (0.029–0.142); p < 0.001). However, it should be noted that his percentage is relative as some missing values were present. Self-reported complications were found to be less prevalent in thoracic aneurysm patients compared to acute aortic dissection patients [48.6% (a) vs. 65.2% (d); OR 2.029 (1.111–3.705); p = 0.021]. A comprehensive comparison of the pre-operative characteristics in thoracic aortic aneurysm vs. acute type A aortic dissection and ethnic majority vs. ethnic minority can be found in Tables 1, 2, respectively.

Figure 2. Patient population. This figure shows a pie chart of the proportion of racial backgrounds in our cohort.

3.3 Post-operative characteristics

At the time of follow up, the mean age was 66.1 ± 10.2 and the mean BMI was 26.5 ± 4.2. The median follow-up time was 6.7 (4.9–10.0) years, with a significantly longer follow-up in patients with thoracic aortic aneurysm patients compared to those with a type A aortic dissection [8.6 (a) vs. 6.9 (d) years; OR 0.863 (0.798–0.934); p < 0.001]. Overall, most patients were retired (93; 51.4%) and highly educated (86; 46.0%). When comparing thoracic aortic aneurysm patients to type A aortic dissection patients, we found that the aneurysm group had significantly more patients that were retired [62.9% (a) vs. 42.6% (d); OR 0.497 (0.273–0.903), p = 0.022] and the dissection group had higher levels of incapacitated patients [5.6% (a) vs. 20.0% (d); OR 4.360 (1.441–13.189), p = 0.009]. Additionally, no significant disparities were found between ethnic majority and ethnic minority patient groups (p > 0.05). A comprehensive comparison of the post-operative characteristics in thoracic aortic aneurysm vs. acute type A aortic dissection and ethnic majority vs. ethnic minority can again be found in Tables 1, 2, respectively.

3.4 Depression and (pre-operative) anxiety

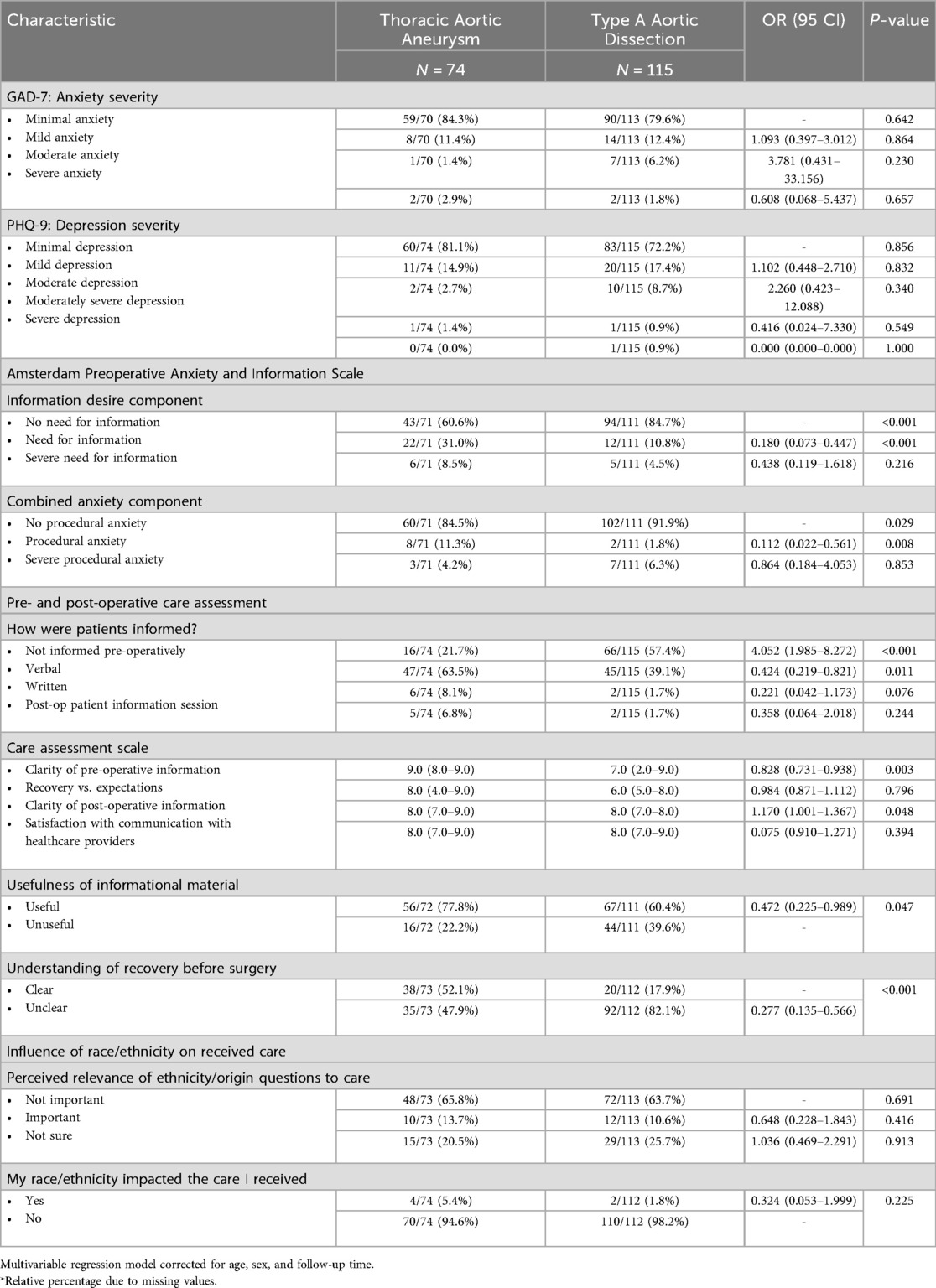

Depression severity, as assessed using the PHQ-9 questionnaire (21) showed that 15 patients (7.9%) had moderate to severe prevalence of depression. When comparing thoracic aortic aneurysms to acute type A aortic dissection and ethnic majority patients to ethnic minority patients, these proportions were not significant (p > 0.05) (Tables 3, 4).

Following, the presence of preoperative anxiety, as assessed using the APAIS questionnaire (22), showed that 45 patients (24.7%) of patients desired information pre-operatively. When comparing thoracic aortic aneurysms to acute type A aortic dissection we found that patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms were significantly more likely to report a general need for information compared with those with acute type A aortic dissection [31.0% (a) vs. 10.8% (d); OR 0.180 (0.073–0.447), p < 0.001]. However, the proportion of patients reporting a severe need for information did not differ significantly between groups [8.5% (a) vs. 4.5% (d); OR 0.438 (0.119–1.618), p = 0.216]. Nevertheless, following survey distribution, we received feedback from several ATAAD patients indicating they responded neutrally to the information-related items, due to the absence of a pre-operative phase. This may partially account for the significantly lower reported desire for information in this group. These disparities were not found in ethnic majority patients compared ethnic minority patients (p > 0.05).

Procedural anxiety was found in 20 patients (11.0%). When comparing thoracic aortic aneurysms to acute type A aortic dissection, procedural anxiety was found in 11 patients (15.5%) compared to 9 patients (8.1%) respectively. Comparable to the findings on information desire, a significant difference was also observed in general procedural anxiety, which was more prevalent among patients with thoracic aortic aneurysm patients than in those with acute type A aortic dissections [11.3% (a) vs. 1.8% (d); 0.112 (0.022–0.561), p = 0.008]. In contrast, the proportion of patients reporting severe procedural anxiety did not differ significantly between the groups [4.2% (a) vs. 6.3% (d); 0.924 (0.198–4.315), p = 0.920] (Tables 3, 4).

Lastly, generalized anxiety, as assessed using the GAD-7 questionnaire (20) showed that moderate to high anxiety rates were seen in 12 patients post-operatively (6.6%). When comparing thoracic aortic aneurysms to acute type A aortic dissection no significant disparities were found (p > 0.05). However, moderate anxiety was significantly more prevalent in ethnic minority patients compared to ethnic majority patients, even after adjusting for age, sex, type of aortopathy diagnosis and follow up duration [3.0% (ethnic majority) vs. 20.0% (ethnic minority); OR 6.607 (1.512–34.517), p = 0.025] (Tables 3, 4).

3.5 Pre- and post-operative care assessment

Our questionnaire assessed various aspects of the pre- and post-operative course in patients with thoracic aortopathy. First, we examined how patients received information. In the overall population, as well as in comparisons between ethnic majority and ethnic minority patients, the primary mode of information delivery was similar, with verbal communication being the most commonly reported method. However, when comparing thoracic aortic aneurysms patients to those with an acute type A aortic dissection, significant disparities were found. Most patients with an acute type A aortic dissection were not informed pre-operatively [21.7% (a) vs. 57.4% (d); OR 4.052 (1.985–8.272), p < 0.001], whereas most patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms were informed verbally [63.5% (a) vs. 39.1% (d); OR 0.424 (0.219–0.821), p = 0.011] (Tables 3, 4).

Furthermore, we asked patients to rate various parts of the received care from 1–10. When comparing thoracic aortic aneurysms to acute type A aortic dissection we found that patients with acute type A aortic dissections reported lower median ratings of the clarity of pre-operative information when being compared to the thoracic aneurysm group [9.0 (a) vs. 7.0 (d); OR 0.828 (0.731–0.938), p = 0.003]. Additionally, patients belonging to an ethnic minority group reported lower median ratings of the clarity of post-operative information compared to ethnic majority patients [8.0 (ethnic majority) vs. 7.0 (ethnic minority); OR 0.772 (0.602–0.982), p = 0.035] (Tables 3, 4).

Lastly, we asked patients if they felt that their race/ethnicity impacted their received care. In general, 180 patients (95.2%) did not find that their ethnic origin impacted the care they received. This finding did not significantly differ among patients of ethnic minority descent (p > 0.05). Additionally, we also asked patients to give their opinion on whether the patients found questions on race and ethnicity in regard to medical care relevant. In general, the majority of patients found ethnic information not important [120 patients (64.5%)]. Slightly higher proportions of ethnic minority patients did find this to be important, while this disparity was not significant [11.7% (ethnic majority) vs. 13.3% (ethnic minority); OR 1.228 (0.230–6.558), p = 0.810] (Tables 3, 4).

3.6 Patient recommendations on improving information provision

The usefulness of the information provided to patients was classified by these patients as either “useful” or “not useful”. The majority of patients [123 (67.2%)] found the informational material to be useful. When comparing patients with a thoracic aortic aneurysm to those with an aortic dissection, the proportion of patients finding the material unhelpful differed significantly; less patients with an aortic dissection found the informational material useful compared to patients with a thoracic aortic aneurysm [77.8% (a) vs. 60.4% (d); OR 0.472 (0.225–0.989), p = 0.047] (Tables 3, 4).

Additionally, patients were asked about their clarity of understanding regarding the recovery process before surgery. In our entire study cohort, 127 patients (68.6%) reported that they had an unclear understanding of the post-operative recovery period before it began. This was particularly evident in patients with an acute type A aortic dissection, as compared to those with an aortic aneurysm [47.9% (a) vs. 82.1% (d); 0.277 (0.135–0.566), p < 0.001] (Tables 3, 4).

In the last segment of our questionnaire, we gave patients the opportunity to give their opinion on how to best enhance information provision (Tables 3, 4). Among the proposed improvements were:

1. Enhancement of (general) information provision (n = 16)

• Use clear and simple language in pre- and post-operative information (n = 8)

• Provide booklets with general information (n = 1)

• Make more online information available (n = 1)

• Use video materials for clarification (n = 4)

• Provide alternative forms of information (n = 1)

• Offer concise information (n = 1)

2. Better post-operative support (n = 13)

• Personalized post-operative guidance, especially in case of complications (n = 6)

• Mental support and assistance in processing experiences (e.g., PTSD) (n = 4)

• Clear explanation of possible residual symptoms (n = 3)

3. Improved communication and coordination (n = 5)

• Better communication between doctors and nursing staff (n = 1)

• Clear identification of contact persons for patients (n = 1)

• One-on-one discussions covering the entire process and possible scenarios (n = 1)

• Consultation with an experienced physician instead of residents (n = 2)

4. More personalized and targeted post-operative support (n = 9)

• Personal advice tailored to the patient (n = 5)

• Involvement of the patient's partner in the process (n = 3)

• Opportunity to ask medical questions (n = 1)

5. Better preparation for surgery (n = 9)

• Preoperative consultation with an experienced physician (n = 1)

• Clear explanation of check-ups and what the patient can expect (n = 8)

4 Discussion

This study aimed to examine the pre- and post-operative course in thoracic aortopathy. Specifically, we investigated whether recovery experiences differed across ethnic groups.

4.1 Depression and (pre-operative) anxiety

One of the key findings from this study was that overall anxiety rates were found to be relatively more prevalent compared to normative values. Previous research reported moderate to severe anxiety in 5.0% of a normative sample (Germany) (24). Our study showed higher anxiety rates than the average in both the ethnic majority and ethnic minority groups, as well as in patients with an aortic dissection, but not in those with a thoracic aortic aneurysm. The finding of heightened anxiety rates in type A aortic dissection was comparable to previous studies (2, 3, 25, 26). A study by McEntire et al. (27) showed that psychological distress can arise due to severe physical inactivity. This may be particularly relevant for aortopathy patients who experience significant physical activity restrictions, leading to reduced functional capacity and quality of life, which in turn may negatively impact their mental well-being (28). Previous research has demonstrated that physical activity influences brain structure and function; for example, it reduces levels of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), which has been associated with increased anxiety and depression. At the same time, physical activity boosts dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline levels, which offer protective effects against the development of mental health disorders (29–31). Also, in case of pre-operative anxiety in elective aortic surgery, this can be improved by stimulating physical activity, which in turn can enhance the recovery trajectory (32). Therefore, encouraging physical activity is crucial in this patient group to mitigate these psychological issues.

Post-operative anxiety was also elevated in ethnic minority patients, even after adjusting for age, sex, follow-up duration and diagnosis of a type A aortic dissection. This is particularly interesting as, to our knowledge, previous research has not yet identified this trend in aortic surgery patients. Previous research has shown that this population often faces differences in cultural perceptions of illness, socioeconomic status, communication barriers between patients and healthcare providers, and variations in disease presentation or access to healthcare services (33–35). These factors may contribute to the development of post-operative anxiety in this group. However, further investigation into the psychosocial factors contributing to ethnic differences in anxiety and depression would be valuable, to better understand the mechanisms driving these disparities.

In patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms, the prevalence of procedural anxiety was significantly higher than in patients with aortic dissection, contrary to our hypothesis. However, as stated in the results, some patients with aortic dissections reported providing neutral responses regarding their pre-operative experience, as not all of them consciously remembered their pre-operative phase. Consequently, these results should be considered exploratory. The APAIS questionnaire should ideally be administered pre-operatively, but since we lacked such data, we attempted to approximate this time period in our analysis.

To obtain more accurate results, a prospective comparison is needed in a future study, as our current findings may underestimate anxiety levels and the need for information in this field. However, the overall demand for information was high across all subgroups, particularly among thoracic aneurysm patients. Considering these findings, it is evident that there is a significant need for information within our patient population.

On the contrary, overall depression rates were relatively low across all subgroups when compared to normative values. Previous research has found moderate to severe depression in 5.6% of a normative sample (Germany) (36). Our study showed lower depression rates than this average. Other research also observed these trends, indicating that depression rates were comparable to those of patients without thoracic aortopathy (37, 38).

4.2 Pre- and post-operative care assessment

The post-operative care experience was also evaluated, and it was found that most patients received verbal information. Previous research indicates that direct communication with patients can improve individualized care, is more specific than educational materials, and can help reduce procedural anxiety (8). However, we still found suboptimal scores in the ratings of pre- and post-operative information clarity. In regard to ethnic based disparities, patients themselves did not report that their ethnicity significantly influenced their received care or impacted their treatment experience. However, as previously mentioned, the results on quality assessments and anxiety rates hint at the possibility of differences in how information was received or processed by some patient groups. This indicates room for improvement in pre-operative education, particularly for these patient groups.

Several studies suggest that this could be addressed through a health promotion program that considers all patient needs both pre- and post-operatively (39, 40). We suggest, however, that such programs should be developed in close collaboration with the target population to meet the broad needs of all individuals. This, in turn, can enhance patient engagement and satisfaction, leading to improved health outcomes. For instance, a review by Stenberg et al. (41) highlighted that co-created group-based patient education programs, involving both healthcare professionals and patients from the target group, effectively promote self-management, which can enable patients to actively work towards a healthy post-operative life. Furthermore, the World Health Organization emphasized that therapeutic patient education should be tailored to the individual needs of patients, suggesting that collaborative development ensures relevance and effectiveness (42).

4.3 Patient recommendations on improving information provision

Patients provided valuable feedback on how to improve information provision and overall care. Most patients recommended: enhancement of (general) information provision, better post-operative support, improved communication and coordination, more personalized and targeted post-operative support, and better preparation for surgery. Adding to these valuable insights, previous research suggests that standardized information provision is often lacking, yet could be highly beneficial (43). Optimizing pre-operative education can significantly enhance overall patient satisfaction while reducing psychological stress and post-operative anxiety, particularly in cardiac surgery patients (43, 44).

4.4 Limitations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Firstly, our study was conducted among patients who underwent surgery between 2000 and 2023, resulting in significant disparities in follow-up time. While we did adjust for follow-up duration in our multivariate analysis, this could potentially affect our findings. Following, as participation in our study was voluntary and limited to those who responded to our questionnaire invitation, this may have introduced some selection bias. However, this also presents a learning opportunity; we could prospectively ask patients to complete our questionnaires at specific time points, allowing for broader generalizability. Additionally, our small sample size could have influenced our results. At the same time, we are studying rare diseases, which inherently leads to smaller sample sizes, as seen in other studies (3, 6).

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights the critical importance of pre- and post-operative education in thoracic aortopathy patients and suggests that ethnic disparities in recovery experiences exist, particularly in the domains of post-operative anxiety and communication. The findings call for more personalized, culturally sensitive care models that address the specific needs of diverse patient populations. By improving communication and providing more tailored information, healthcare providers can help reduce anxiety, improve recovery outcomes, and ensure more equitable care for all patients undergoing thoracic aortic surgery.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Medical Ethical Committee of the Leiden University Medical Center: reference number B21.051/MS/ms, and acceptance date 31-01-2024. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NB: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. AT: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. SG: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. RK: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. NG: Project administration, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1708865/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Czerny M, Grabenwöger M, Berger T, Aboyans V, Della Corte A, Chen EP, et al. EACTS/STS guidelines for diagnosing and treating acute and chronic syndromes of the aortic organ. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2024) 65(2):ezad426. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezad426

2. Bacour N, Grewal S, Theijsse RT, Klautz RJM, Grewal N. From survival to recovery: understanding the life impact of an acute aortic dissection through activity, sleep, and quality of life. J Clin Med. (2025) 14(3):859. doi: 10.3390/jcm14030859

3. Bacour N, van Erp O, Grewal S, Tirpan AU, Eberl S, Yeung KK, et al. Beyond survival: assessing quality of life, activity level, and ethnic diversity in aortic dissection survivors. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. (2025) 12(2):78. doi: 10.3390/jcdd12020078

4. Mejia OAV, Borgomoni GB, Lasta N, Okada MY, Gomes MSB, Foz MLNN, et al. Safe and effective protocol for discharge 3 days after cardiac surgery. Sci Rep. (2021) 11(1):8979. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88582-0

5. Abraham J, Kandasamy M, Huggins A. Articulation of postsurgical patient discharges: coordinating care transitions from hospital to home. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2022) 29(9):1546–58. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocac099

6. Breel JS, de Klerk ES, Strypet M, de Heer F, Hermanns H, Hollmann MW, et al. What really matters to survivors of acute type A aortic dissection—a survey of patient-reported outcomes in the Dutch national aortic dissection advocacy group. J Clin Med. (2023) 12(20):6584. doi: 10.3390/jcm12206584

7. Jlala HA, French JL, Foxall GL, Hardman JG, Bedforth NM. Effect of preoperative multimedia information on perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing procedures under regional anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. (2010) 104(3):369–74. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq002

8. Eberhart L, Aust H, Schuster M, Sturm T, Gehling M, Euteneuer F, et al. Preoperative anxiety in adults—a cross-sectional study on specific fears and risk factors. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02552-w

9. Kharod U, Panchal NN, Varma J, Sutaria K. Effect of pre-operative communication using anaesthesia information sheet on pre-operative anxiety of patients undergoing elective surgery-A randomised controlled study. Indian J Anaesth. (2022) 66(8):559–72. doi: 10.4103/ija.ija_32_22

10. Peng F, Peng T, Yang Q, Liu M, Chen G, Wang M. Preoperative communication with anesthetists via anesthesia service platform (ASP) helps alleviate patients’ preoperative anxiety. Sci Rep. (2020) 10(1):18708. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74697-3

11. Macias-Konstantopoulos WL, Collins KA, Diaz R, Duber HC, Edwards CD, Hsu AP, et al. Race, healthcare, and health disparities: a critical review and recommendations for advancing health equity. West J Emerg Med. (2023) 24(5):906–18. doi: 10.5811/WESTJEM.58408

12. National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Health, Medicine D, Board on Population H, Public Health P, et al. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Copyright 2017 by the National Academy of Sciences (2017). (All rights reserved).

13. Wilson Jimica B, Jackson Larry R, Ugowe Francis E, Jones T, Yankey George SA, Marts C, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in treatment and outcomes of severe aortic stenosis. JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13(2):149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.08.056

14. Lu C, Ahmed R, Lamri A, Anand SS. Use of race, ethnicity, and ancestry data in health research. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2022) 2(9):e0001060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001060

15. Edwards TL, Breeyear J, Piekos JA, Velez Edwards DR. Equity in health: consideration of race and ethnicity in precision medicine. Trends Genet. (2020) 36(11):807–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2020.07.001

16. Yelton MJ, Jildeh TR. Cultural competence and the postoperative experience: pain control and rehabilitation. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. (2023) 5(4):100733. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2023.04.016

17. Perry M, Baumbauer K, Young EE, Dorsey SG, Taylor JY, Starkweather AR. The influence of race, ethnicity and genetic variants on postoperative pain intensity: an integrative literature review. Pain Manag Nurs. (2019) 20(3):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2018.11.002

18. Publishing. JCfAoIaDi. Diversity Data Collection in Scholarly Publishing. Available online at: https://wwwrscorg/policy-evidence-campaigns/inclusion-diversity/joint-commitment-for-action-inclusion-and-diversity-in-publishing/diversity-data-collection-in-scholarly-publishing/ (Accessed March 05, 2025).

19. Flanagin A, Frey T, Christiansen SL, Committee AMoS. Updated guidance on the reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. JAMA. (2021) 326(7):621–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13304

20. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166(10):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

21. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

22. Moerman N, van Dam FS, Muller MJ, Oosting H. The Amsterdam preoperative anxiety and information scale (APAIS). Anesth Analg. (1996) 82(3):445–51. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199603000-00002

24. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. (2008) 46(3):266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

25. Ilonzo N, Taubenfeld E, Yousif MD, Henoud C, Howitt J, Wohlauer M, et al. The mental health impact of aortic dissection. Semin Vasc Surg. (2022) 35(1):88–99. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2022.02.005

26. Chaddha A, Kline-Rogers E, Braverman AC, Erickson SR, Jackson EA, Franklin BA, et al. Survivors of aortic dissection: activity, mental health, and sexual function. Clin Cardiol. (2015) 38(11):652–9. doi: 10.1002/clc.22418

27. McEntire A, Helm BM, Landis BJ, Elmore LR, Wilson T, Wetherill L, et al. Psychological distress in response to physical activity restrictions in patients with non-syndromic thoracic aortic aneurysm/dissection. J Community Genet. (2021) 12(4):631–41. doi: 10.1007/s12687-021-00545-0

28. Chaddha A, Eagle KA, Braverman AC, Kline-Rogers E, Hirsch AT, Brook R, et al. Exercise and physical activity for the post-aortic dissection patient: the clinician’s conundrum. Clin Cardiol. (2015) 38(11):647–51. doi: 10.1002/clc.22481

29. Martinowich K, Manji H, Lu B. New insights into BDNF function in depression and anxiety. Nat Neurosci. (2007) 10(9):1089–93. doi: 10.1038/nn1971

30. Cotman CW, Berchtold NC, Christie LA. Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. (2007) 30(9):464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.011

31. Young SN. How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs. J Psychiatry Neurosci. (2007) 32(6):394–9. doi: 10.1139/jpn.0738

32. Fathi M, Alavi SM, Joudi M, Joudi M, Mahdikhani H, Ferasatkish R, et al. Preoperative anxiety in candidates for heart surgery. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. (2014) 8(2):90–6. PMID: 25053963.25053963

33. Ekezie W, Cassambai S, Czyznikowska B, Curtis F, O'Mahoney LL, Willis A, et al. Health and social care experience and research perception of different ethnic minority populations in the East Midlands, United Kingdom (REPRESENT study). Health Expect. (2024) 27(1):e13944. doi: 10.1111/hex.13944

34. Bacour N, Grewal S, Ploem MC, Suurmond J, Klautz RJM, Grewal N. Bridging barriers: engaging ethnic minorities in cardiovascular research. Healthcare (Basel). (2025) 13(11):1217. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13111217

35. Muncan B. Cardiovascular disease in racial/ethnic minority populations: illness burden and overview of community-based interventions. Public Health Rev. (2018) 39(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40985-018-0109-4

36. Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2013) 35(5):551–5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006

37. Blakeslee-Carter J, Menon AJ, Novak Z, Spangler EL, Beck AW, McFarland GE. Association of mental health disorders and aortic dissection. Ann Vasc Surg. (2021) 77:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2021.05.054

38. Okamoto Y, Motomura N, Murashima S, Takamoto S. Anxiety and depression after thoracic aortic surgery or coronary artery bypass. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. (2013) 21(1):22–30. doi: 10.1177/0218492312444283

39. Lang X, Feng D, Huang S, Liu Y, Zhang K, Shen X, et al. How to help aortic dissection survivors with recovery?: a health promotion program based on the comprehensive theory of health behavior change and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). (2023) 102(7):e33017. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000033017

40. Bacour N, Grewal S, Tirpan AU, Theijse R, Erp OV, Klautz RJM, et al. The TRAIN health awareness clinical trial: baseline findings and cardiovascular risk management in aortic dissection patients. Aorta (Stamford). (2024) 12(4):86–93. doi: 10.1055/a-2524-4772

41. Stenberg U, Haaland-Øverby M, Fredriksen K, Westermann KF, Kvisvik T. A scoping review of the literature on benefits and challenges of participating in patient education programs aimed at promoting self-management for people living with chronic illness. Patient Educ Couns. (2016) 99(11):1759–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.027

42. Therapeutic Patient Education: An Introductory Guide (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289060219 (Accessed March 05, 2025).

43. Brodersen F, Wagner J, Uzunoglu FG, Petersen-Ewert C. Impact of preoperative patient education on postoperative recovery in abdominal surgery: a systematic review. World J Surg. (2023) 47(4):937–47. doi: 10.1007/s00268-022-06884-4

Keywords: aortopathy, ethnicity, health disparities, pre- and post-operative course, anxiety

Citation: Bacour N, Tirpan AU, Grewal S, Klautz RJM and Grewal N (2025) Exploring ethnic differences in the perioperative course of thoracic aortopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1708865. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1708865

Received: 19 September 2025; Accepted: 27 October 2025;

Published: 17 November 2025.

Edited by:

Giuseppe Nasso, LUM University "Giuseppe Degennaro", ItalyReviewed by:

Maria Grazia De Rosis, ASL Bari, ItalyTommaso Loizzo, LUM University "Giuseppe Degennaro", Italy

Copyright: © 2025 Bacour, Tirpan, Grewal, Klautz and Grewal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nimrat Grewal, bi5ncmV3YWxAYW1zdGVyZGFtdW1jLm5s

Nora Bacour

Nora Bacour Aytug U. Tirpan1

Aytug U. Tirpan1 Robert J. M. Klautz

Robert J. M. Klautz Nimrat Grewal

Nimrat Grewal