Abstract

Background:

Intraoperative hypotension (IOH) presents a risk factor for postoperative organ dysfunction. However, as a unique definition of IOH is still missing, the influence of individual preoperative patient characteristics on IOH remains poorly understood. This systematic review aimed to examine the variability in IOH definitions and to identify preoperative risk factors associated with IOH.

Methods:

A systematic literature search was conducted from inception to March 2, 2024. Studies reporting on IOH and from which the association between preoperative characteristics and IOH in cardiac and non-cardiac surgery could be derived were included. Odds ratios (ORs) were either extracted directly or calculated based on available patient-level data. Pooled estimates were generated using a random-effects model.

Results:

Out of 7,361 screened studies, 78 met the inclusion criteria. Heterogeneity was high due to varying IOH definitions. 14 preoperative factors were included in the meta-analysis. Older age (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04) and female sex (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.08–1.24) were associated with increased IOH risk. ASA-II was linked to lower risk compared to ASA-III (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.91). Diabetes mellitus (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.04–1.35) and arterial hypertension (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.33–1.83) were independent predictors. ACE inhibitor use (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use; OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.42–1.88), angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) use (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.01–1.89), and emergent surgery (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.09–1.42) also increased IOH incidence. The risk of bias was low to moderate.

Conclusion:

The substantial variability in IOH definitions and several preoperative IOH influencing patient characteristics highlight the need for standardized criteria to improve comparability and guide personalized perioperative management.

Systematic Review Registration:

identifier PROSPERO CRD42024514229.

Introduction

Intraoperative hypotension (IOH) presents a risk factor for serious postoperative complications, including major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), stroke, acute kidney injury (AKI), and increased perioperative mortality (1, 2). Evidence indicates that postoperative organ dysfunction is not only associated with the occurrence of hypotension, but is even more strongly linked to its severity and duration, with both brief but profound hypotension as well as prolonged mild hypotension significantly contributing to risk (3).

As IOH is not yet uniformly defined, varying thresholds and durations applied across studies result in inconsistent incidence rates and limited comparability of findings (4). A comprehensive review highlighted the lack of a consensus definition and suggested a classification based on underlying mechanisms such as vasodilation, hypovolemia, or myocardial depression, emphasizing the need for individualized clinical interpretation (5). Other works have stressed the complex and multifactorial pathophysiology of IOH, calling attention to both systemic and patient-specific contributors (6). More recent perspectives have advocated for a symptom-oriented understanding of IOH, shifting the focus from fixed blood pressure thresholds to the broader hemodynamic impact, potentially redefining intraoperative blood pressure management (7).

In this context, emerging data suggest that specific patient-related factors may increase susceptibility to IOH. A retrospective cohort study identified preoperatively assessed functional status, measured using the Fried frailty criteria (8), as an independent predictor of IOH in elderly non-cardiac surgical patients (9). In addition, a systematic review demonstrated that preoperative volume status may also significantly influence the risk of IOH (10). A subgroup analysis pointed toward potentially relevant gender-related susceptibilities, suggesting that elderly female patients might be particularly vulnerable to IOH (11).

Objective

This systematic review aimed to examine the variability in IOH definitions used across studies, as inconsistent definitions may affect the identification and comparability of preoperative risk factors. Furthermore, we aimed to identify preoperative patient-related characteristics that serve as risk factors for the incidence of IOH. We hypothesized that patient-specific factors can be identified before surgery that are consistently associated with an increased risk of IOH.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO on 01.03.2024 (CRD42024514229) (12). The study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (13).

Selection criteria

Prior to the systematic search, inclusion criteria were established through a consensus-based approach using the PICOS framework (Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes, and Study Design) (Table 1).

Table 1

| P | Patients (≥18 years old) undergoing cardiac and non-cardiac surgery |

| I | Preoperative patient characteristics as predictors for hypotensive events (e.g., age, ASA status, pre-existing conditions, premedication) |

| C | Patients without the potential risk factors described above |

| O | Hypotensive event (e.g., Probability of Occurrence, Rate, Duration, and Severity) |

| S | Randomized controlled trials, Prospective cohort studies, Retrospective cohort studies |

PICOS criteria for the inclusion criteria of the systematic literature review.

ASA, American society of anesthesiologists; PICOS, participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, study design.

Studies were excluded if they were not published in English or German language.

All authors collaboratively developed the systematic search strategy. Following its approval, the search was conducted in databases including Embase, MEDLINE (via Ovid) and the Cochrane Library. The detailed search strategy for each database is provided in Supplementary Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix. The search covered all records available from the inception of each database up to March 2, 2024. Additionally, we manually screened the reference lists of relevant review articles to identify further eligible studies.

Study selection

Two independent and blinded reviewers screened all studies retrieved from the systematic search, assessing titles and abstracts based on the PICOS criteria. A third independent reviewer resolved discrepancies. After title and abstract screening, the same procedure was applied to the full-text assessment.

Data extraction process

The full texts of all included studies were reviewed by one researcher, who extracted all relevant information. A second researcher cross-checked the extracted data for accuracy and consistency. Extracted Information included the PICOS criteria as well as patient and study specific characteristics, and the definition of IOH used. Given the primary objective of this review to examine the variability in IOH definitions, we did not impose a uniform blood pressure threshold. Instead, IOH was extracted as reported in the original study, provided that the authors explicitly defined the event as intraoperative in nature. For meta-analytic pooling, IOH was therefore operationalized as a binary outcome (occurrence vs. no occurrence) based on the study's definition. This approach reflects the real-world heterogeneity of IOH definitions and enables comparison of patientś susceptibility rather than of specific hemodynamic thresholds.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias was assessed using the RoB-2 tool (14) for randomized controlled studies, ROBINS-E tool (15) for prospective studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (16) for retrospective studies. Two raters independently evaluated each study. In case of discrepancies, a third rater determined the final overall risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with MetaAnalysisOnline.com (17). The respective odds ratios (OR) for the incidence of IOH were pooled using a random-effects model, particularly for studies exhibiting high heterogeneity. Whenever available, ORs were extracted directly from the studies. In cases where ORs were missing, they were independently calculated using logistic regression models based on individual patient data, provided sufficient data was available.

Patient characteristics identified in individual studies as influencing the incidence of IOH were included in the meta-analysis, if data were available from at least five independent studies. This criterion was applied to mitigate potential bias and ensure the robustness of the analysis. Subgroup analyses were conducted for studies that exclusively investigated either general anesthesia or spinal anesthesia. Studies that included both anesthetic techniques or focused solely on regional anesthesia were categorized as “Other”. For the age-related meta-analysis, studies with age-restricted populations (e.g., cohorts limited to patients above a predefined age threshold) were excluded to prevent range restriction bias, unless sufficient within-study age variability was reported. To prevent demographic confounding, obstetric studies were excluded from the meta-analyses assessing sex and age, as these populations are uniformly female and younger. Obstetric studies were retained in other analyses, where demographic imbalance does not structurally bias effect estimates.

Inter-study heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic (values > 75% indicating considerable heterogeneity, values <25% suggesting low heterogeneity) and τ2, estimated via the restricted maximum-likelihood method, and p-values derived from Cochran's Q test (18, 19). Potential publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot to visually examine left–right symmetry (20). A 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was applied, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Results of the literature search

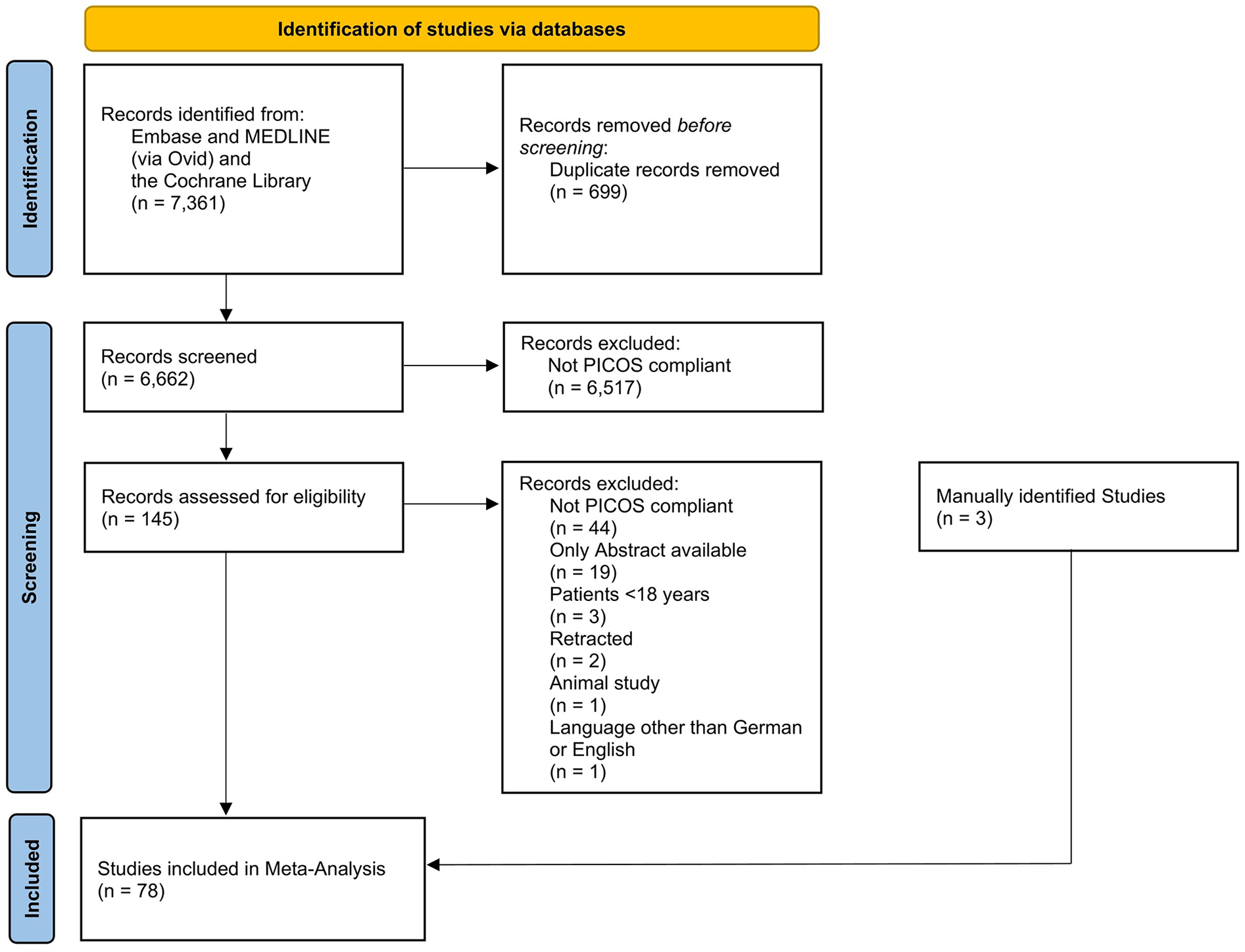

Of the 7,361 screened studies, 78 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the statistical analysis (Figure 1). The included studies comprised a total of 934,021 patients, of whom one study followed a randomized controlled design, 46 a prospective study design, while 31 studies were retrospective (Table 2). A total of 45 studies investigated patients under general anesthesia, whereas six studies included both general and spinal anesthesia. An additional 21 studies exclusively focused on spinal anesthesia, while two studies examined a combination of general and regional anesthesia, and two studies solely assessed regional anesthesia. A total of 48 studies focused exclusively on elective surgeries, whereas 18 studies analyzed both elective and emergency procedures.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the systematic search.

Table 2

| Author | Year | Country | General/Spinal/Regional Anesthesia | Blood Pressure Definition of IOH | Patient Total | LoE | Women (%) | Emergency/Elective | Main surgery department |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelhamid et al. (a) (21) | 2022 | Egypt | Spinal | MAP <75% | 71 | 3 | 28 (39.4%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Abdelhamid et al. (b) (22) | 2022 | Egypt | General | MAP <75% | 93 | 3 | 44 (47.3%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Aissaoui et al. (23) | 2022 | Morocco | General | SAP <90 mmHg or SAP <70% or MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <70% | 64 | 3 | 28 (43.8%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Aktas Yildirim et al. (24) | 2023 | Turkey | General | SAP <90 mmHg or MAP <70% | 85 | 3 | 22 (25.9%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Alghanem et al. (25) | 2020 | Jordan | General/Spinal | SAP <70% | 502 | 4 | 237 (47.2%) | n.a. | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Au et al. (26) | 2016 | USA | General | SAP <90 mmHg | 40 | 3 | 21 (53.0%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Baek et al. (27) | 2023 | South Korea | Regional | SAP <90 mmHg or MAP <60 mmHg | 2,152 | 4 | 1,003 (46.6%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Bellotti et al. (28) | 2022 | USA | General | MAP <55 mmHg | 857 | 4 | 525 (61.3%) | Both | General Surgery |

| Bijker et al. (2) | 2009 | Netherlands | General/Spinal | SAP <80 mmHg | 1,705 | 3 | 825 (48.4%) | Elective | General Surgery/Vascular Surgery |

| Bishop et al. (29) | 2017 | South Africa | Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg | 504 | 3 | 504 (100%) | Both | Obstetrics |

| Boyle et al. (30) | 2022 | Canada | General | MAP <80 mmHg | 47 | 3 | 14 (29.8%) | Elective | Neurosurgery |

| Brenck et al. (31) | 2009 | Germany | Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg or MAP <80% | 503 | 4 | 503 (100%) | Both | Obstetrics |

| Casalino et al. (32) | 2006 | Italy | General | MAP ≤60 mmHg or MAP <70% | 144 | 4 | 41 (28.5%) | Elective | Cardiac Surgery |

| Chen et al. (33) | 2023 | China | General | MAP <60 mmHg or MAP <80% | 173 | 3 | 75 (43.4%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Cheung et al. (34) | 2015 | Canada | General/Regional | SAP <90 mmHg or MAP <65% | 193 | 3 | 128 (66.3%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Chiang et al. (35) | 2022 | Taiwan | General | SAP <80 mmHg | 1,833 | 4 | 781 (42.6%) | Elective | Neurosurgery |

| Chinachoti et al. (36) | 2007 | Thailand | Spinal | SAP <80% | 2,000 | 3 | 1,338 (66.9%) | Both | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Choi et al. (37) | 2020 | South Korea | General | MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <70% | 77 | 3 | 36 (46.8%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Chowdhury et al. (38) | 2022 | India | Spinal | MAP <80% | 50 | 3 | 12 (24.0%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Chumpathong et al. (39) | 2006 | Thailand | Spinal | SAP ≤100 mmHg | 991 | 4 | 991 (100%) | Both | Obstetrics |

| Czajka et al. (40) | 2023 | Poland | General | MAP ≤65 mmHg | 508 | 3 | 269 (53.0%) | Both | General Surgery |

| Dai et al. (41) | 2020 | China | General/Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg or SAP <80% | 5,864 | 4 | 3,103 (52.9%) | Both | n.a. |

| Doo et al. (42) | 2021 | South Korea | Regional | SAP <90 mmHg or SAP <70% | 116 | 4 | 52 (44.8%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Elbadry et al. (43) | 2022 | Egypt | Spinal | MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <80% | 55 | 3 | 55 (100%) | Elective | Obstetrics |

| Fathy et al. (44) | 2023 | Egypt | General | SAP <70% or MAP <65 mmHg | 153 | 3 | 83 (54.2%) | Elective | Neurosurgery |

| Fukuhara et al. (45) | 2021 | Japan | General/Spinal | SAP ≤80 mmHg | 245 | 4 | 43 (16.9%) | n.a. | Urology |

| Gregory et al. (46) | 2021 | USA | n.a. | MAP ≤65 mmHg | 368,222 | 4 | 226,694 (62.0%) | n.a. | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Gurunathan et al. (47) | 2024 | Australia | General | SAP <70% or MAP <55 mmHg | 537 | 3 | 207 (38.5%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Hartmann et al. (48) | 2002 | Germany | Spinal | MAP <70% | 3,098 | 4 | 1,180 (38.1%) | Both | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Hojo et al. (49) | 2022 | Japan | General | MAP ≤55 mmHg | 395 | 4 | 184 (46.6%) | n.a. | Oral and maxillofacial Surgery |

| Hoppe et al. (50) | 2022 | Germany | General | MAP <70% | 366 | 3 | 195 (53.0%) | Elective | Ear, Nose and Throat Surgery |

| Huang et al. (51) | 2024 | China | General | SAP <70% or MAP < 80% or SAP <90 mmHg and MAP <60 mmHg | 112 | 3 | 44 (38.3%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Jia et al. (52) | 2022 | China | General | Blood pressure <80% | 367 | 4 | 48 (13.1%) | n.a. | Vascular Surgery |

| Jin et al. (53) | 2021 | China | General | MAP <65 mmHg | 114 | 4 | 66 (57.9%) | n.a. | General Surgery |

| Jin et al. (54) | 2024 | China | General | SAP <70% or MAP <60 mmHg or MAP <70% | 95 | 3 | 63 (66.3%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Jor et al. (55) | 2018 | Czech Republic | General | MAP <70% | 661 | 3 | n.a. | Elective | n.a. |

| Juri et al. (56) | 2018 | Japan | General | MAP <65 mmHg | 45 | 3 | 16 (35.6%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Kalezic et al. (57) | 2013 | Serbia | General | SAP <80% | 1,252 | 3 | 1,081 (86.3%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Katori et al. (58) | 2023 | Japan | General | MAP <65 mmHg | 11,210 | 4 | 5,457 (48.7%) | Both | Oral and maxillofacial Surgery |

| Kaydu et al. (59) | 2018 | Turkey | General | MAP <80% | 80 | 3 | 38 (48.7%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Kendale et al. (60) | 2018 | USA | General | MAP <55 mmHg | 13,323 | 4 | 7,441 (56.0%) | n.a. | Gynecology |

| Khaled et al. (61) | 2023 | Egypt | General | MAP <80% | 133 | 3 | 61 (45.9%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Kim et al. (62) | 2022 | South Korea | Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg and SAP <80% | 50 | 3 | 10 (20.0%) | Elective | Urology |

| Klasen et al. (63) | 2003 | Germany | Spinal | MAP <70% | 2,619 | 4 | 1,296 (49.5%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Kondo et al. (64) | 2023 | Japan | General | MAP <65 mmHg | 261 | 4 | 57 (21.9%) | Elective | Urology |

| Kose et al. (65) | 2012 | Turkey | General | MAP <70% | 157 | 3 | 75 (47.8%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Lal et al. (66) | 2023 | India | Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg or SAP <80% or MAP <60 mmHg | 75 | 3 | 17 (22.7%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Lee et al. (67) | 2022 | South Korea | General | Blood pressure <65 mmHg | 888 | 3 | 486 (54.7%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Lee et al. (68) | 2024 | South Korea | General | MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <80% | 421 | 4 | 236 (56.1%) | Both | General Surgery |

| Li et al. (69) | 2024 | Taiwan | Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg | 999 | 4 | 999 (100%) | Elective | Obstetrics |

| Lin et al. (70) | 2011 | Taiwan | General | SAP <90 mmHg or SAP <70% | 1,311 | 4 | 830 (63.3%) | Both | n.a. |

| Maitra et al. (71) | 2020 | India | General | SAP <70% or MAP <80% or SAP <90 mmHg and MAP <65 mmHg | 112 | 3 | 58 (51.8%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Malima et al. (72) | 2019 | South Africa | Spinal | SAP <100 mmHg or SAP <25% | 357 | 3 | 212 (59.4%) | Both | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Mohammed et al. (73) | 2021 | India | General | MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <70% | 110 | 2 | 52 (47.3%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Morisawa et al. (74) | 2022 | Japan | General | SAP <70 mmHg | 142 | 4 | 57 (40.0%) | n.a. | Neurosurgery |

| Moschovaki et al. (75) | 2023 | Greece | Spinal | MAP ≤65 mmHg or MAP <75% | 61 | 3 | 33 (54.1%) | n.a. | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Ni et al. (76) | 2022 | China | Spinal | MAP <60 mmHg or MAP <70% | 90 | 3 | 42 (46.7%) | Elective | Urology |

| Oh et al. (77) | 2024 | South Korea | General | MAP <65 mmHg | 157 | 3 | 90 (57.3%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Ohpasanon et al. (78) | 2008 | Thailand | Spinal | SAP <100 mmHg and SAP <80% | 807 | 3 | 807 (100%) | Both | Obstetrics |

| Okamura et al. (79) | 2019 | Japan | General | MAP <60 mmHg or MAP <70% | 82 | 3 | 46 (56.1%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Saengrung et al. (80) | 2022 | Thailand | General | SAP <90 mmHg | 83 | 4 | 22 (29.0%) | Emergency | Neurosurgery |

| Salama et al. (81) | 2019 | Egypt | Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg or SAP <70% or MAP <60 mmHg | 100 | 3 | 55 (55.0%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Saranteas et al. (82) | 2019 | Greece | Spinal | MAP ≤65 mmHg or MAP <75% | 70 | 3 | 41 (56.5%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Schonberger et al. (83) | 2022 | USA | General | MAP <55 mmHg | 319,948 | 4 | 165,733 (51.8%) | Both | General Surgery |

| Shao et al. (84) | 2022 | China | General | MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <70% | 61 | 3 | 29 (47.5%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Sharma et al. (85) | 2024 | India | General | MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <80% | 100 | 3 | 65 (65.0%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Singh et al. (86) | 2019 | India | Spinal | MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <80% | 40 | 3 | 40 (100%) | Elective | Obstetrics |

| Somboonviboon et al. (87) | 2008 | Thailand | Spinal | SAP <70% | 722 | 3 | 722 (100%) | Both | Obstetrics |

| Südfeld et al.(88) | 2017 | Germany | General/Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg | 2,037 | 4 | 901 (44.2%) | Both | n.a. |

| Taffe et al. (89) | 2009 | Switzerland | General/Regional | Blood pressure <70% | 147,573 | 4 | n.a. | Both | n.a. |

| Tarao et al. (90) | 2021 | Japan | General | MAP ≤50 mmHg | 200 | 4 | 77 (33.5%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Thirunelli et al. (91) | 2021 | India | General | MAP <60 mmHg or MAP <80% | 106 | 3 | 53 (50.0%) | Elective | n.a. |

| Walsh et al. (3) | 2013 | USA | n.a. | MAP <55 mmHg | 33,330 | 4 | 16,836 (50.5%) | Both | n.a. |

| Wang et al. (92) | 2022 | China | General | MAP <65 mmHg or MAP <80% | 99 | 3 | 34 (34.3%) | Elective | General Surgery |

| Wang et al. (93) | 2024 | China | General | SAP ≤80 mmHg or SBP <80% or MAP ≤60 mmHg | 1,461 | 4 | 192 (23.9%) | n.a. | Cardiac Surgery |

| Yatabe et al. (94) | 2020 | Japan | General/Spinal | MAP <60 mmHg | 172 | 4 | 45 (26.2%) | n.a. | Urology |

| Yilmaz et al. (95) | 2022 | Turkey | Spinal | SAP <90 mmHg or MAP <60 mmHg | 95 | 3 | 33 (34.7%) | Elective | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Zhang et al. (96) | 2016 | China | General | MAP <60 mmHg or MAP <70% | 90 | 3 | 47 (52.2%) | Elective | Cardiac Surgery |

Study characteristics along with the respective definitions of intraoperative hypotension.

DAP, diastolic arterial pressure; IOH, intraoperative hypotension; LoE, level of evidence based on (97); MAP, mean arterial pressure; n.a., not available; SAP, systolic arterial pressure.

Definition of IOH

The definition of IOH varied across studies (Table 2). In 25 studies, IOH was defined based on an absolute threshold for systolic arterial pressure (SAP) or mean arterial pressure (MAP). 14 studies defined IOH as a relative reduction in SAP or MAP compared to baseline values. In 36 studies, a combination of these criteria was used, whereas three studies described IOH as a general decrease in blood pressure.

Patient characteristics

14 preoperative characteristics were identified and included in the analysis. These were then further classified into the following categories: patient-specific characteristics, pre-existing comorbidities, pre-existing medication, and emergency interventions. A meta-analysis was only feasible for the occurrence of IOH. For other outcomes—such as the rate, duration, and severity of IOH—the available data were too scarce and too heterogeneous to allow for meaningful synthesis.

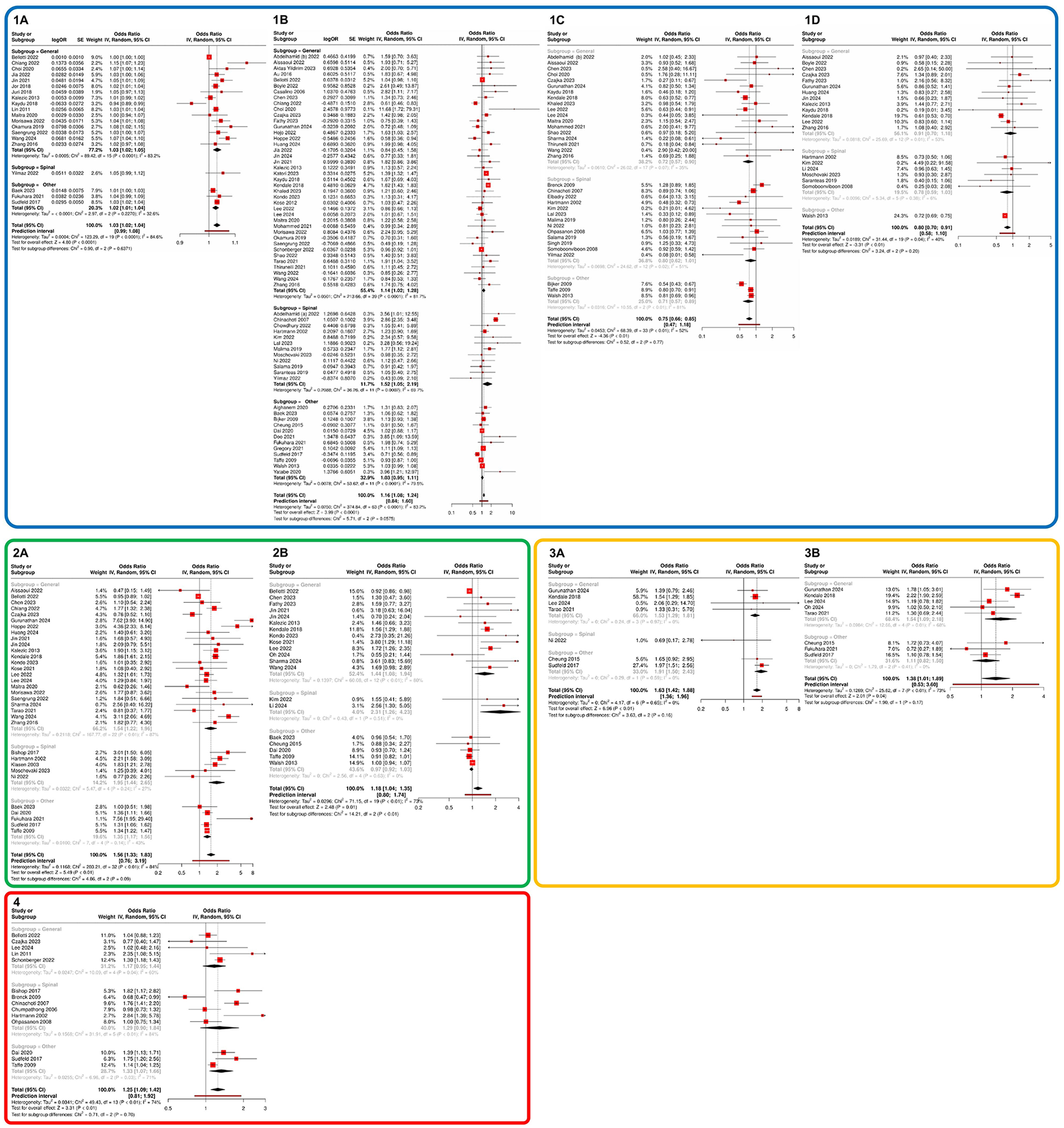

In the patient-specific characteristics, increasing age was associated with a 3% higher risk of IOH (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04, 20 studies; see Figure 2(1A)]. This effect was found to be statistically significant in both the group that considered only general anesthesia (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.05, 16 studies). Furthermore, female sex was found to be associated with a 16% increased risk of IOH [OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.08–1.24, 64 studies; see Figure 2[1B]). In the comparison of general anesthesia to spinal anesthesia, female sex was a significant influencing factor in the general anesthesia group (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02–1.28, 40 studies) as well as in the spinal anesthesia group (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.05–2.19, 12 studies).

Figure 2

Meta-analysis of influencing factors regarding the probability of IOH occurrence. Section 1 (blue) presents specific patient characteristics: (1A) age, (1B) sex, (1C) ASA status I vs. II, and (1D) ASA status II vs. III. Section 2 (green) illustrates pre-existing comorbidities: (2A) arterial hypertension and (2B) diabetes mellitus. Section 3 (orange) depicts pre-existing medication: (3A) ACEI and (3B) ARB. Section 4 (red) highlights the impact of emergency surgery. Subgroups were defined as studies that exclusively investigated general anaesthesia, those that focused solely on regional anaesthesia, and studies that included both anaesthesia techniques or purely regional procedures. The latter were categorized under “Other”. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ASA, American society of anesthesiologists; IOH, intraoperative hypotension.

The assessment of preoperative health status based on ASA classification demonstrated a stepwise increase in IOH risk with higher ASA classes. Patients with ASA I had a 25% lower risk of IOH compared to patients with ASA II (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.66–0.85; 34 studies; see Figure 2[1C]). Likewise, patients with ASA II had a 20% lower risk compared to patients with ASA III (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.91; 20 studies; see Figure 2[1D]).

With regard to pre-existing comorbidities, patients with a known diagnosis of diabetes mellitus had an 18% higher likelihood of experiencing IOH (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.04–1.35, 20 studies), whereas a history of hypertension was associated with a 56% increased probability of developing IOH (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.33–1.83, 33 studies) (see Figures 2[2A/B]. These associations remained significant across all subgroup analyses. In contrast, body mass index (BMI) showed no significant impact on the risk of IOH (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99–1.02, 18 studies; see Supplementary Figure S1A).

The analysis of preoperative hemodynamic parameters revealed that SAP, MAP, and diastolic arterial pressure (DAP), as well as heart rate, had no significant influence on the risk of developing IOH (see Supplementary Figure S1). In contrast, the evaluation of preoperative long-term medication use indicated that the intake of ACEI was associated with a 63% increased probability of IOH (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.42–1.88, 7 studies), whereas the use of ARBs was linked to a 38% increased likelihood of IOH (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.01–1.89, 8 studies) (see Figure 2[3A,B]). Regarding the likelihood of IOH occurring during emergency surgeries, a significant increase of 25% was observed (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.09–1.42, 14 studies; see Figure 2[4]).

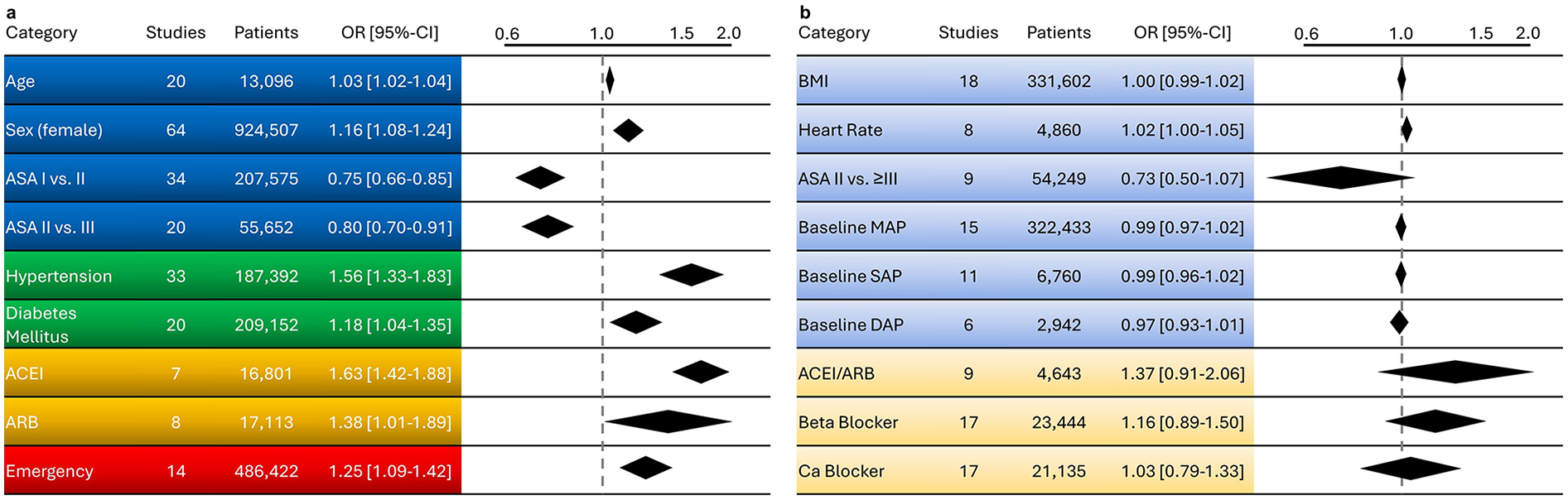

A comprehensive overview of all results, including the corresponding overall ORs, is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Overview of factors influencing the likelihood of intraoperative hypotension. In panel (a), significant factors are shown in stronger colours, while in panel (b), non-significant factors are displayed in lighter shades, each with their respective odds ratios. (Blue) represents specific patient characteristics, (green) illustrates pre-existing comorbidities, (orange) depicts pre-existing medication, and (red) highlights the impact of emergency surgery. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ASA, American society of anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; Ca, calcium; CI, confidence Interval; OR, odds rat.

Heterogeneity and risk of bias

Overall heterogeneity was remarkably high, with an I2 > 75%. However, when examining the significant influencing factors ASA status II vs. III and ACEI, heterogeneity was moderate (I2 < 50%) and low (I2 = 0%), respectively (see Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). Regarding publication bias, only a minor distortion of the published data was observed (see Supplementary Figure S2). The risk of bias was assessed as low to moderate in most studies; four prospective studies demonstrated a high risk of bias (see Supplementary Tables S2–S4).

Discussion

Our systematic review confirmed that IOH remains inconsistently defined across the literature, with substantial variability in threshold values and measurement methods. This lack of a uniform definition was consistently reflected in the included studies and represents a central challenge in synthesizing evidence. Accordingly, in our analysis we adopted a definition-inclusive approach, retaining the original IOH definitions used by individual studies. This allowed us to investigate patientś susceptibility to IOH across real-world practice variation. Therefore, our results should be interpreted as reflecting vulnerability to intraoperative hypotensive episodes, rather than referencing a single fixed pressure threshold. Despite this heterogeneity, the meta-analysis identified several patient-related factors that are significantly associated with a higher likelihood of IOH, including increasing age, female sex, higher ASA classification, preexisting hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic use of ACEIs or ARBs, and emergency surgical procedures.

Despite its high clinical relevance, IOH remains without a universally accepted definition, which continues to impede both clinical standardization and scientific advancement. The variability in thresholds and diagnostic criteria limits comparability across studies and complicates the development of evidence-based treatment protocols. Notably, even major clinical guidelines reflect this lack of consensus. This inconsistency highlights the urgent need for a harmonized, evidence-based definition of IOH to enable coherent risk stratification, intraoperative decision-making, and outcome evaluation across clinical settings within an individual patient treatment approach (98, 99).

Intraoperative hemodynamics result from a complex interplay of systemic, pharmacological, surgical, and patient-specific factors and should therefore be understood as a multimodal concept. Rather than focusing on isolated variables, it is essential to consider the dynamic interaction of multiple risk components, which may collectively contribute to the onset and severity of IOH.

Several studies have demonstrated that IOH can lead to severe organ dysfunction (1–3, 100). In this context, the identification of individual patient preoperative risk factors may become a crucial first step targeting precision medicine. However, it still remains scarce which preoperative patient characteristics are associated with an increased risk of developing IOH. Dana et al., in their systematic review, investigated the role of preoperative ultrasound in predicting IOH and identified the preoperative inferior vena cava collapsibility index (IVC-CI) as a surrogate for volume responsiveness as a strong predictor of post-induction hypotension (10). However, other metanalysis doubt the usefulness of IVC evaluation at all (101). Importantly, IOH should be regarded not as a disease entity but as a clinical symptom indicative of diverse underlying intraoperative pathophysiological mechanisms (5). This heterogeneity necessitates a structured intraoperative diagnostic pathway to distinguish between different hemodynamic causes, such as vasodilation, hypovolemia, or myocardial depression, which can be conceptualized as distinct endotypes (6). Accurate intraoperative interpretation is thus essential for effective and individualized management. While MAP thresholds provide practical surrogate targets, they do not account for interindividual differences in vascular tone, autoregulatory capacity and pulse pressure propagation. In addition, postoperative complications are more closely related to impaired organ oxygen distribution/consumption relying on both adequate blood flow and arterial pressure according to the law of Ohm. Thus, future perioperative monitoring and clinical practice must incorporate more than only pressure-related targets to improve patientś outcome.

Our findings now contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of IOH susceptibility and support the use of structured preoperative risk stratification to identify vulnerable patients. It will be essential to adopt a patient-specific approach based on individual characteristics to develop and implement tailored therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing IOH more effectively (102). Such an approach enables individualized intraoperative management and may ultimately improve postoperative outcomes.

Chen et al. were among the first to systematically explore patient characteristics in relation to IOH, suggesting that older age, female sex, antihypertensive medication use, and emergency procedures may increase IOH risk (103). However, their conclusions were based solely on descriptive data from 12 included studies, without conducting a meta-analysis. In contrast, our review included 78 studies, as we applied a broader search strategy and were additionally able to incorporate results from studies using patient-level data, thereby enabling, for the first time, a robust meta-analysis within a large and heterogeneous surgical patient cohort. Our findings corroborate the initial hypotheses by Chen et al., confirming significant associations between IOH and the above-mentioned factors.

Bos et al. also examined age and sex as risk factors in their systematic review (11). While they did not find a significant influence of female sex on IOH exposure in the general cohort (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.98–1.23), a subset analysis of studies with an average age ≥65 years showed increased IOH exposure in females (OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.01–1.35). Similarly, in our analysis, female sex was associated with a 16% higher likelihood of experiencing IOH. Prior studies have emphasized the need to consider sex-specific factors in clinical decision-making (104, 105). It has been demonstrated that, even under the same therapeutic regimen, female sex is an independent risk factor for increased mortality and that different safety cut-offs may be necessary (105). Whether comparable safety cut-offs for IOH are adequate among male and female patients remains unknown and should be investigated in the future. Linked to this, the sex of the anesthesia provider may play a role in addition to the patient's sex: a recent study demonstrated that female anesthesia providers more effectively prevented IOH, intraoperative desaturation, and hyper- or hypocapnia (106).

Our data identified patients with preexisting arterial hypertension and chronic use of Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS)–modulating medications (e.g., ACEIs) as particularly vulnerable, with a more than 50% higher probability of IOH. Duceppe et al. reported that in patients undergoing major vascular surgery, long-term antihypertensive therapy was independently associated with increased risk of postoperative AKI (107). On the contrary, others stated that current evidence is insufficient to recommend routine discontinuation of ACEIs/ARBs on the day of surgery but stressed the need for anesthesiologists to remain vigilant for IOH and manage it proactively (108, 109). Discontinuation has also been found to increase the likelihood of clinical significant hypertension in non-cardiac surgery (110). Moreover, it is important to note that the influence of surgical extent on the risk of IOH has not yet been adequately addressed, even in randomized controlled trials (7). While several of these associations have been reported previously, the available evidence has remained fragmented. Importantly, our findings confirm the physiologically expected increased susceptibility to IOH in patients with chronic hypertension, which is likely related to impaired baroreflex sensitivity and altered vascular compliance, and refine the magnitude of this association through pooled effect estimation. The novelty of our analysis lies in aggregating and meta-analytically quantifying these associations across 78 worl-wide studies and more than 930,000 patients. Moreover, by evaluating hypertensive disease and chronic RAAS-modulating medication use separately, our results suggest that these represent related but distinct contributors to IOH risk. Demonstrating that these effects are consistent across diverse anesthesia techniques and surgical specialties strengthens their validity as preoperative risk surrogates and supports their use in a structured, individualized perioperative hemodynamic management.

Limitations

One of the key strengths and primary objectives of our study is its comprehensive inclusion of the wide variability in IOH definitions present in the literature. Though this heterogeneity has already been suggested (4), our systematic review now provides a unique and thorough meta-analytical synthesis that captures the full spectrum of IOH definitions used up to date. While this complexity presents challenges, it also represents an important advance by reflecting real-world variability and enhancing the generalizability of our findings. To account for between-study differences, we applied a random-effects model, yielding more conservative and broadly applicable effect estimates. Importantly, despite the diversity, most studies employed comparable thresholds for absolute or relative blood pressure reductions, supporting the overall interpretability of the results.

Additionally, our analysis included both cardiac and non-cardiac surgery populations. Given the distinct hemodynamic profiles and perioperative management strategies between these groups, this broad inclusion adds another layer of real-world heterogeneity, which in turn might be considered a further strength by capturing a wider clinical spectrum and improving external validity.

A notable limitation of our meta-analysis is the heterogeneity and incomplete reporting of key clinical context variables across studies. In particular, type of surgery, intraoperative medication strategies (e.g., vasopressors, vasodilators, beta-blockers), and patient-specific pathophysiological profiles (e.g., trauma, frailty, myelopathy) were reported inconsistently or aggregated into broad categories, which did not allow for statistically robust subgroup analyses. Therefore, the associations identified in this review should be interpreted as reflecting general patientś susceptibility to IOH rather than interactions between patient characteristics and specific surgical or pharmacologic management strategies, especially in the context of underlying cardiovascular comorbidity. Moreover, considerable variability in study inclusion criteria and frequent underreporting of clinically relevant subgroups (e.g., patients with heart failure or atrial fibrillation) may limit the generalizability of our findings and introduce selection bias.

Beyond commonly assessed factors like age, sex, and comorbidities, functional status has been identified in previous research as a significant predictor of IOH. Specifically, preoperative frailty or functional impairment independently increases IOH risk, even after adjusting for age and ASA classification (9). Unfortunately, due to inconsistent reporting, this important parameter could not be included in our quantitative synthesis. Similarly, certain high-risk populations remain underrepresented in current literature. Future investigations, such as the ongoing PeriopCAreHF trial, are expected to address these gaps, thereby refining patient stratification and perioperative management strategies (111).

Due to considerable heterogeneity and insufficient reporting of IOH episode duration and severity across studies, we were unable to incorporate these important parameters within a time-weighted area under the curve approach into our analysis and were therefore restricted to only a binary consideration of IOH occurrence. Yet, existing studies suggest that the duration and depth of IOH episodes play a pivotal role in the development of organ dysfunction (3). Bijker et al. demonstrated that the more severe the hypotension, the shorter the threshold duration for a significant increase in mortality (2). Although heterogeneity was primarily driven by differences in IOH definitions, additional variability in effect estimates due to studies with mixed or regional anesthesia approaches (categorized as “Other” in the Methods section) cannot be excluded. Finally, the hemodynamic influence of neuraxial techniques such as thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA) could not be analyzed separately due to limited subgroup data; future studies should therefore evaluate TEA and combined general–epidural approaches as distinct anesthetic strategies with potentially unique IOH risk profiles.

As the evidence base expands, meta-regression techniques could help systematically explore potential effect modifiers. Further research is also needed to investigate whether the patient-related risk factors identified in our analysis not only influence the incidence but also the duration and severity of IOH. Incorporating these aspects could enhance perioperative risk stratification and support more targeted hemodynamic management strategies.

Conclusion

Our analysis underscores the considerable variability in definitions of IOH across studies, which complicates comparisons and the interpretation of findings. Establishing standardized IOH definitions in the future is crucial to enable more consistent research and improve clinical decision-making. Despite this variability, we identified a significant impact of patient characteristics, such as age, sex, comorbidities, and chronic medication use, on the incidence of IOH. However, further research is needed to explore how these factors may also influence the duration and severity of IOH episodes. To guide future clinical implementation and research, a standardized and physiologically informed definition of IOH are needed that allow distinguishing different mechanisms of intraoperative hypotensive episodes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ND: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Visualization, Data curation, Resources, Project administration, Validation, Investigation, Software, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. DB: Data curation, Resources, Validation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Software, Writing – original draft. MT: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. JF: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. DW: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Software. CS: Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. FB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. RM: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. OH: Project administration, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. AM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. DC: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AP: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. AB: Investigation, Software, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. MK: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation. ST: Conceptualization, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. MM: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Project administration, Data curation, Supervision, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Software, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

ST reports honoraria for lectures and workshops by Orion Pharma, Edwards Lifesciences, AOP Health, Cytosorbents, Chiesi, and Philips as well as research funding or grants by the German ministry on Research, Technology and Space, the German ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, the German Science Foundation, Queen Mary Hospital, Orion Pharma, Becton Dickinson, Cytosorbents, the B. Braun Foundation, and Charité; all outside the presented work. CS received grants or contracts and non-financial support from German Research Society, German Aerospace Center, Einstein Foundation Berlin, Federal Joint Committee (G-BA), Inner University Grants, Project Management Agency, Non-Profit Society Promoting Science and Education, European Society Of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, BMWI—Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Georg Thieme Verlag, Dr. F. Köhler Chemie GmbH, Sintetica GmbH, MaxPlanck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e.V., Stifterverband für die deutsche Wissenschaft e.V., Metronic, Philips Electronics Nederland BV, BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research, RKI, The European Commission Horizont Europa, Prothor, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Lynx Health Science GmbH, Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany, German Research Foundation, German National Academy of Sciences—Leopoldina, Berliner Medizinische Gesellschaft, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, German Sepsis Foundation and holds various international patents; these holdings have not affected any decisions regarding his research or this study.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1709004/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary File 1Visual abstract. Created in BioRender. Markus, M. (2025), https://BioRender.com/a6gg90v.

References

1.

Salmasi V Maheshwari K Yang D Mascha EJ Singh A Sessler DI et al Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology. (2017) 126(1):47–65. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001432

2.

Bijker JB van Klei WA Vergouwe Y Eleveld DJ van Wolfswinkel L Moons KG et al Intraoperative hypotension and 1-year mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. (2009) 111(6):1217–26. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c14930

3.

Walsh M Devereaux PJ Garg AX Kurz A Turan A Rodseth RN et al Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology. (2013) 119(3):507–15. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a10e26

4.

Bijker JB van Klei WA Kappen TH van Wolfswinkel L Moons KG Kalkman CJ . Incidence of intraoperative hypotension as a function of the chosen definition: literature definitions applied to a retrospective cohort using automated data collection. Anesthesiology. (2007) 107(2):213–20. 10.1097/01.anes.0000270724.40897.8e

5.

Meng L . Heterogeneous impact of hypotension on organ perfusion and outcomes: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. (2021) 127(6):845–61. 10.1016/j.bja.2021.06.048

6.

Kouz K Brockmann L Timmermann LM Bergholz A Flick M Maheshwari K et al Endotypes of intraoperative hypotension during major abdominal surgery: a retrospective machine learning analysis of an observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth. (2023) 130(3):253–61. 10.1016/j.bja.2022.07.056

7.

Flick M Vokuhl C Bergholz A Boutchkova K Nicklas JY Saugel B . Personalized intraoperative arterial pressure management and mitochondrial oxygen tension in patients having major non-cardiac surgery: a pilot substudy of the IMPROVE trial. J Clin Monit Comput. (2025). 10.1007/s10877-024-01260-0

8.

Fried LP Tangen CM Walston J Newman AB Hirsch C Gottdiener J et al Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2001) 56(3):M146–56. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146

9.

Daum N Hoff L Spies C Pohrt A Bald A Langer N et al Influence of frailty status on the incidence of intraoperative hypotensive events in elective surgery: Hypo-Frail, a single-centre retrospective cohort study. Br J Anaesth. (2025). 10.1016/j.bja.2024.10.050

10.

Dana E Dana HK De Castro C Bueno Rey L Li Q Tomlinson G et al Inferior vena cava ultrasound to predict hypotension after general anesthesia induction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Can J Anaesth. (2024) 71(8):1078–91. 10.1007/s12630-024-02776-4

11.

Bos EME Tol JTM de Boer FC Schenk J Hermanns H Eberl S et al Differences in the incidence of hypotension and hypertension between sexes during non-cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. (2024) 13(3):666. 10.3390/jcm13030666

12.

Daum N Bill D Markus M Fabig L Bald A Langer N et al Preoperative Patient Characteristics as Predictors for Intraoperative Hypotension: a Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. (2024).

13.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

14.

Sterne JAC Savović J Page MJ Elbers RG Blencowe NS Boutron I et al Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. (2019) 366:14898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898

15.

Higgins JPT Morgan RL Rooney AA Taylor KW Thayer KA Silva RA et al A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ Int. (2024) 186:108602. 10.1016/j.envint.2024.108602

16.

Wells GA Shea B O'Connell D Peterson J Welch V Losos M et al The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hosp Res Instit. (2014).

17.

Fekete JT Győrffy B . Metaanalysisonline.com: web-based tool for the rapid meta-analysis of clinical and epidemiological studies. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e64016. 10.2196/64016

18.

Higgins JP Thompson SG . Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21(11):1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186

19.

Higgins JP Thompson SG Deeks JJ Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. (2003) 327(7414):557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

20.

Sterne JAC Becker BJ Egger M . The Funnel Plot. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. Chichester and Hoboken, NJ: Wiley (2006). p. 73–98.

21.

Abdelhamid BM Abeer A Mai R Ashraf R Hassan H . Pre-anaesthetic ultrasonographic assessment of neck vessels as predictors of spinal anaesthesia induced hypotension in the elderly: a prospective observational study. Egypt J Anaesth. (2022) 38(1):349–56. 10.1080/11101849.2022.2082051

22.

Abdelhamid B Yassin A Ahmed A Amin S Abougabal A . Perfusion index-derived parameters as predictors of hypotension after induction of general anaesthesia: a prospective cohort study. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. (2022) 54(1):34–41. 10.5114/ait.2022.113956

23.

Aissaoui Y Jozwiak M Bahi M Belhadj A Alaoui H Qamous Y et al Prediction of post-induction hypotension by point-of-care echocardiography: a prospective observational study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. (2022) 41(4):101090. 10.1016/j.accpm.2022.101090

24.

Aktas Yildirim S Sarikaya ZT Dogan L Ulugol H Gucyetmez B Toraman F . Arterial elastance: a predictor of hypotension due to anesthesia induction. J Clin Med. (2023) 12(9).

25.

Alghanem SM Massad IM Almustafa MM Al-Shwiat LH El-Masri MK Samarah OQ et al Relationship between intra-operative hypotension and post-operative complications in traumatic hip surgery. Indian J Anaesth. (2020) 64(1):18–23. 10.4103/ija.IJA_397_19

26.

Au AK Steinberg D Thom C Shirazi M Papanagnou D Ku BS et al Ultrasound measurement of inferior vena cava collapse predicts propofol-induced hypotension. Am J Emerg Med. (2016) 34(6):1125–8. 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.03.058

27.

Baek S Lee J Shin YS Jo Y Park J Shin M et al Perioperative hypotension in patients undergoing orthopedic upper extremity surgery with dexmedetomidine sedation: a retrospective study. J Pers Med. (2023) 13(12):1658. 10.3390/jpm13121658

28.

Bellotti A Arora S Gustafson C Funk I Grossheusch C Simmers C et al Predictors of post-induction hypotension for patients with pulmonary hypertension. Cureus. (2022) 14(11):e31887. 10.7759/cureus.31887

29.

Bishop DG Cairns C Grobbelaar M Rodseth RN . Obstetric spinal hypotension: preoperative risk factors and the development of a preliminary risk score—the PRAM score. S Afr Med J. (2017) 107(12):1127–31. 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i12.12390

30.

Boyle SL Moodley A Al Azazi E Dinsmore M Massicotte EM Venkatraghavan L . Preoperative heart rate variability predicts postinduction hypotension in patients with cervical myelopathy: a prospective observational study. Neurol India. (2022) 70(8):S269–S75. 10.4103/0028-3886.360911

31.

Brenck F Hartmann B Katzer C Obaid R Bruggmann D Benson M et al Hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: identification of risk factors using an anesthesia information management system. J Clin Monit Comput. (2009) 23(2):85–92. 10.1007/s10877-009-9168-x

32.

Casalino S Mangia F Stelian E Novelli E Diena M Tesler UF . High thoracic epidural anesthesia in cardiac surgery: risk factors for arterial hypotension. Tex Heart Inst J. (2006) 33(2):148–53.

33.

Chen H Zhang X Wang L Zheng C Cai S Cheng W . Association of infraclavicular axillary vein diameter and collapsibility index with general anesthesia-induced hypotension in elderly patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery: an observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23(1):340. 10.1186/s12871-023-02303-w

34.

Cheung CC Martyn A Campbell N Frost S Gilbert K Michota F et al Predictors of intraoperative hypotension and bradycardia. Am J Med. (2015) 128(5):532–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.11.030

35.

Chiang T-Y Wang Y-K Huang W-C Huang S-S Chu Y-C . Intraoperative hypotension in non-emergency decompression surgery for cervical spondylosis: the role of chronic arterial hypertension. Front Med (Lausanne). (2022) 9:943596. 10.3389/fmed.2022.943596

36.

Chinachoti T Tritrakarn T . Prospective study of hypotension and bradycardia during spinal anesthesia with bupivacaine: incidence and risk factors, part two. J Med Assoc Thai. (2007) 90(3):492–501.

37.

Choi MH Chae JS Lee HJ Woo JH . Pre-anaesthesia ultrasonography of the subclavian/infraclavicular axillary vein for predicting hypotension after inducing general anaesthesia: a prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2020) 37(6):474–81. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001192

38.

Chowdhury SR Baidya DK Maitra S Singh AK Rewari V Anand RK . Assessment of role of inferior vena cava collapsibility index and variations in carotid artery peak systolic velocity in prediction of post-spinal anaesthesia hypotension in spontaneously breathing patients: an observational study. Indian J Anaesth. (2022) 66(2):100–6. 10.4103/ija.ija_828_21

39.

Chumpathong S Chinachoti T Visalyaputra S Himmunngan T . Incidence and risk factors of hypotension during spinal anesthesia for cesarean section at Siriraj hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. (2006) 89(8):1127–32.

40.

Czajka S Putowski Z Krzych ŁJ . Post-induction hypotension and intraoperative hypotension as potential separate risk factors for the adverse outcome: a cohort study. J Anesth. (2023) 37(3):442–50. 10.1007/s00540-023-03191-7

41.

Dai S Li X Yang Y Cao Y Wang E Dong Z . A retrospective cohort analysis for the risk factors of intraoperative hypotension. Int J Clin Pract. (2020) 74(8):e13521. 10.1111/ijcp.13521

42.

Doo AR Lee H Baek SJ Lee J . Dexmedetomidine-induced hemodynamic instability in patients undergoing orthopedic upper limb surgery under brachial plexus block: a retrospective study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2021) 21(1):207. 10.1186/s12871-021-01416-4

43.

Elbadry AA El Dabe A Sabaa A A M . Pre-operative ultrasonographic evaluation of the internal jugular vein collapsibility index and inferior vena cava collapsibility Index to predict post spinal hypotension in pregnant women undergoing caesarean section. Anesth Pain Med. (2022) 12(1):e121648. 10.5812/aapm.121648

44.

Fathy MM Wahdan RA Salah AAA Elnakera AM . Inferior vena cava collapsibility index as a predictor of hypotension after induction of general anesthesia in hypertensive patients. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23(1):420. 10.1186/s12871-023-02355-y

45.

Fukuhara H Nohara T Nishimoto K Hatakeyama Y Hyodo Y Okuhara Y et al Identification of risk factors associated with oral 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced hypotension in photodynamic diagnosis for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a multicenter retrospective study. BMC Cancer. (2021) 21(1):1223. 10.1186/s12885-021-08976-1

46.

Gregory A Stapelfeldt WH Khanna AK Smischney NJ Boero IJ Chen Q et al Intraoperative hypotension is associated with adverse clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. (2021) 132(6):1654–65. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005250

47.

Gurunathan U Roe A Milligan C Hay K Ravichandran G Chawla G . Preoperative renin-angiotensin system antagonists intake and blood pressure responses during ambulatory surgical procedures: a prospective cohort study. Anesth Analg. (2024) 138(4):763–74. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006728

48.

Hartmann B Junger A Klasen J Benson M Jost A Banzhaf A et al The incidence and risk factors for hypotension after spinal anesthesia induction: an analysis with automated data collection. Anesth Analg. (2002) 94(6):1521. 10.1213/00000539-200206000-00027

49.

Hojo T Kimura Y Shibuya M Fujisawa T . Predictors of hypotension during anesthesia induction in patients with hypertension on medication: a retrospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2022) 22(1):343. 10.1186/s12871-022-01899-9

50.

Hoppe P Burfeindt C Reese PC Briesenick L Flick M Kouz K et al Chronic arterial hypertension and nocturnal non-dipping predict postinduction and intraoperative hypotension: a secondary analysis of a prospective study. J Clin Anesth. (2022) 79:110715. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2022.110715

51.

Huang CJ Kuok CH Kuo TB Hsu YW Tsai PS . Pre-operative measurement of heart rate variability predicts hypotension during general anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2006) 50(5):542–8. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.001016.x

52.

Jia Y Feng G Wang Z Feng Y Jiao L Wang T-L . Prediction of risk factors for intraoperative hypotension during general anesthesia undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:890107. 10.3389/fneur.2022.890107

53.

Jin Y-N Feng H Wang Z-Y Li J . Analysis of the risk factors for hypotension in laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair. Int J Gen Med. (2021) 14:5203–8. 10.2147/IJGM.S327259

54.

Jin G Liu F Yang Y Chen J Wen Q Wang Y et al Carotid blood flow changes following a simulated end-inspiratory occlusion maneuver measured by ultrasound can predict hypotension after the induction of general anesthesia: an observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2024) 24(1):13. 10.1186/s12871-023-02393-6

55.

Jor O Maca J Koutna J Gemrotova M Vymazal T Litschmannova M et al Hypotension after induction of general anesthesia: occurrence, risk factors, and therapy. A prospective multicentre observational study. J Anesth. (2018) 32(5):673–80. 10.1007/s00540-018-2532-6

56.

Juri T Suehiro K Tsujimoto S Kuwata S Mukai A Tanaka K et al Pre-anesthetic stroke volume variation can predict cardiac output decrease and hypotension during induction of general anesthesia. J Clin Monit Comput. (2018) 32(3):415–22. 10.1007/s10877-017-0038-7

57.

Kalezic N Stojanovic M Ladjevic N Markovic D Paunovic I Palibrk I et al Risk factors for intraoperative hypotension during thyroid surgery. Int Med J Exp Clin Res. (2013) 19:236–41. 10.12659/MSM.883869

58.

Katori N Yamakawa K Kida K Kimura Y Fujioka S Tsubokawa T . The incidence of hypotension during general anesthesia: a single-center study at a university hospital. JA Clin Rep. (2023) 9(1):23. 10.1186/s40981-023-00617-9

59.

Kaydu A Güven DD Gökcek E . Can ultrasonographic measurement of carotid intima-media thickness predict hypotension after induction of general anesthesia?J Clin Monit Comput. (2019) 33(5):825–32. 10.1007/s10877-018-0228-y

60.

Kendale S Kulkarni P Rosenberg AD Wang J . Supervised machine-learning predictive analytics for prediction of postinduction hypotension. Anesthesiology. (2018) 129(4):675–88. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002374

61.

Khaled D Ismail F EY M Dina Z Rasmy I . Comparison of ultrasound-based measures of inferior vena cava and internal jugular vein for prediction of hypotension during induction of general anesthesia. Egypt J Anaesth. (2023) 39(1):87–94. 10.1080/11101849.2023.2171548

62.

Kim HJ Cho A-R Lee H Kim H Kwon J-Y Lee H-J et al Ultrasonographic carotid artery flow measurements as predictors of spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension in elderly patients: a prospective observational study. Int Med J Exp Clin Res. (2022) 28:e938714. 10.12659/MSM.938714

63.

Klasen J Junger A Hartmann B Benson M Jost A Banzhaf A et al Differing incidences of relevant hypotension with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia and spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg. (2003) 96(5):1491–5. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000057601.90930.18

64.

Kondo Y Nagamine Y Yoshikawa N Echigo N Kida T Sumitomo M et al Incidence of perioperative hypotension in patients undergoing transurethral resection of bladder tumor after oral 5-aminolevulinic acid administration: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. J Anesth. (2023) 37(5):703–13. 10.1007/s00540-023-03222-3

65.

Kose EA Kabul HK Yildirim V Tulmac M . Preoperative exercise heart rate recovery predicts intraoperative hypotension in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Clin Anesth. (2012) 24(6):471–6. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2012.02.007

66.

Lal J Jain M Rahul Singh AK Bansal T Vashisth S . Efficacy of inferior vena cava collapsibility index and caval aorta index in predicting the incidence of hypotension after spinal anaesthesia- A prospective, blinded, observational study. Indian J Anaesth. (2023) 67(6):523–9. 10.4103/ija.ija_890_22

67.

Lee S Lee M Kim S-H Woo J . Intraoperative hypotension prediction model based on systematic feature engineering and machine learning. Sensors. (2022) 22(9):3108. 10.3390/s22093108

68.

Lee HJ Kim YJ Woo JH Oh H-W . Preoperative frailty is an independent risk factor for postinduction hypotension in older patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Gerontol Ser A. (2024) 79(1).

69.

Li Y-S Lin S-P Horng H-C Tsai S-W Chang W-K . Risk factors of more severe hypotension after spinal anesthesia for caesarean section. J Chin Med Assoc (2024).

70.

Lin C-S Chang C-C Chiu J-S Lee Y-W Lin J-A Mok MS et al Application of an artificial neural network to predict postinduction hypotension during general anesthesia. Int J Soc Med Decis Making. (2011) 31(2):308–14. 10.1177/0272989X10379648

71.

Maitra S Baidya DK An RK Subramanium R Bhattacharjee S . Carotid artery corrected flow time and respiratory variations of peak blood flow velocity for prediction of hypotension after induction of general anesthesia in adult patients undergoing elective surgery: a prospective observational study. J Ultrasound Med. (2020) 39(4):721–30. 10.1002/jum.15151

72.

Malima Z Torborg A Cronjé L Biccard BM . Predictors of post-spinal hypotension in elderly patients: a prospective observational study in the Durban Metropole, ZA. S Afr J Anaesth Analg. (2019) 25(5):13–7. 10.36303/SAJAA.2019.25.5.A2

73.

Mohamed S Befkadu A Mohammed A Neme D Ahmed S Yimer Y et al Effectiveness of prophylactic ondansetron in preventing spinal anesthesia induced hypotension and bradycardia in pregnant mother undergoing elective cesarean delivery: a double blinded randomized control trial, 2021. Int J Surg Open. (2021) 35:100401. 10.1016/j.ijso.2021.100401

74.

Morisawa S Jobu K Ishida T Kawada K Fukuda H Kawanishi Y et al Association of 5-aminolevulinic acid with intraoperative hypotension in malignant glioma surgery. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. (2022) 37:102657. 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102657

75.

Moschovaki N Saranteas T Spiliotaki E Giannoulis D Anagnostopoulos D Talliou C et al Point of care transthoracic echocardiography for the prediction of post—spinal anesthesia hypotension in elderly patients with cardiac diseases and left ventricular dysfunction: inferior vena cava and post-spinal anesthesia hypotension in elderly patients. J Clin Monit Comput. (2023) 37(5):1207–18. 10.1007/s10877-023-00981-y

76.

Ni T-T Zhou Z-F He B Zhou Q-H . Inferior vena cava collapsibility index can predict hypotension and guide fluid management after spinal anesthesia. Front Surg. (2022) 9:831539. 10.3389/fsurg.2022.831539

77.

Oh CS Park JY Kim SH . Comparison of effects of telmisartan versus valsartan on post-induction hypotension during noncardiac surgery: a prospective observational study. Korean J Anesthesiol. (2024) 77(3):335–44. 10.4097/kja.23658

78.

Ohpasanon P Chinachoti T Sriswasdi P Srichu S . Prospective study of hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section at siriraj hospital: incidence and risk factors, part 2. J Med Assoc Thail. (2008) 91(5):675–80.

79.

Okamura K Nomura T Mizuno Y Miyashita T Goto T . Pre-anesthetic ultrasonographic assessment of the internal jugular vein for prediction of hypotension during the induction of general anesthesia. J Anesth. (2019) 33(5):612–9. 10.1007/s00540-019-02675-9

80.

Saengrung S Kaewborisutsakul A Tunthanathip T Phuenpathom N Taweesomboonyat C . Risk factors for intraoperative hypotension during decompressive craniectomy in traumatic brain injury patients. World Neurosurg. (2022) 162:e652–e8. 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.03.102

81.

Salama ER Elkashlan M . Pre-operative ultrasonographic evaluation of inferior vena cava collapsibility index and caval aorta index as new predictors for hypotension after induction of spinal anaesthesia: a prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2019) 36(4):297–302. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000956

82.

Saranteas T Spiliotaki H Koliantzaki I Koutsomanolis D Kopanaki E Papadimos T et al The utility of echocardiography for the prediction of spinal-induced hypotension in elderly patients: inferior vena Cava assessment is a key player. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2019) 33(9):2421–7. 10.1053/j.jvca.2019.02.032

83.

Schonberger RB Dai F Michel G Vaughn MT Burg MM Mathis M et al Association of propofol induction dose and severe pre-incision hypotension among surgical patients over age 65. J Clin Anesth. (2022) 80:110846. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2022.110846

84.

Shao L Zhou Y Yue Z Gu Z Zhang J Hui K et al Pupil maximum constriction velocity predicts post-induction hypotension in patients with lower ASA status: a prospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2022) 22(1):274. 10.1186/s12871-022-01808-0

85.

Sharma V Sharma A Sethi A Pathania J . Diagnostic accuracy of left ventricular outflow tract velocity time integral versus inferior vena cava collapsibility index in predicting post-induction hypotension during general anesthesia: an observational study. Acute Crit Care. (2024) 39(1):117–26. 10.4266/acc.2023.00913

86.

Singh Y An RK Gupta S Chowdhury SR Maitra S Baidya DK et al Role of IVC collapsibility index to predict post spinal hypotension in pregnant women undergoing caesarean section. An observational trial. Saudi J Anaesth. (2019) 13(4):312–7. 10.4103/sja.SJA_27_19

87.

Somboonviboon W Kyokong O Charuluxananan S Narasethakamol A . Incidence and risk factors of hypotension and bradycardia after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section. J Med Assoc Thail. (2008) 91(2):181–7.

88.

Südfeld S Brechnitz S Wagner JY Reese PC Pinnschmidt HO Reuter DA et al Post-induction hypotension and early intraoperative hypotension associated with general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. (2017) 119(1):57–64. 10.1093/bja/aex127

89.

Taffe P Sicard N Pittet V Pichard S Burn B . The occurrence of intra-operative hypotension varies between hospitals: observational analysis of more than 147,000 anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2009) 53(8):995–1005. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02032.x

90.

Tarao K Daimon M Son K Nakanishi K Nakao T Suwazono Y et al Risk factors including preoperative echocardiographic parameters for post-induction hypotension in general anesthesia. J Cardiol. (2021) 78(3):230–6. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2021.03.010

91.

Thirunelli RK Nanjundaswamy NH . A prospective observational study of plethysmograph variability index and perfusion index in predicting hypotension with propofol induction in noncardiac surgeries. Anesth Essays Res. (2021) 15(2):167–73. 10.4103/aer.aer_81_21

92.

Wang J Li Y Su H Zhao J Tu F . Carotid artery corrected flow time and respiratory variations of peak blood flow velocity for prediction of hypotension after induction of general anesthesia in elderly patients. BMC Geriatr. (2022) 22(1):882. 10.1186/s12877-022-03619-x

93.

Wang L Xiao L Hu L Chen X Wang X . Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting intraoperative hypotension in cardiac valve replacement. Biomark Med. (2023) 17(20):849–58. 10.2217/bmm-2023-0548

94.

Yatabe T Karashima T Kume M Kawanishi Y Fukuhara H Ueba T et al Identification of risk factors for post-induction hypotension in patients receiving 5-aminolevulinic acid: a single-center retrospective study. JA Clin Rep. (2020) 6(1):35. 10.1186/s40981-020-00340-9

95.

Yilmaz A Demir U Taskin O Soylu VG Doganay Z . Can ultrasound-guided femoral vein measurements predict spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension in non-obstetric surgery? A prospective observational study. Medicina. (2022) 58(11).

96.

Zhang J Critchley LA . Inferior vena cava ultrasonography before general anesthesia can predict hypotension after induction. Anesthesiology. (2016) 124(3):580–9. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001002

97.

Medicine CfE-B. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence. (2011). Available online at:https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence(Accessed May 01, 2025).

98.

Saugel B Annecke T Bein B Flick M Goepfert M Gruenewald M et al Intraoperative haemodynamic monitoring and management of adults having non-cardiac surgery. Anasthesiol Intensivmed. (2024) 65:193–212.

99.

Saugel B Fletcher N Gan TJ Grocott MPW Myles PS Sessler DI . Perioperative quality initiative (POQI) international consensus statement on perioperative arterial pressure management. Br J Anaesth. (2024) 133(2):264–76. 10.1016/j.bja.2024.04.046

100.

Wesselink EM Kappen TH Torn HM Slooter AJC van Klei WA . Intraoperative hypotension and the risk of postoperative adverse outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. (2018) 121(4):706–21. 10.1016/j.bja.2018.04.036

101.

Huang H Shen Q Liu Y Xu H Fang Y . Value of variation index of inferior vena cava diameter in predicting fluid responsiveness in patients with circulatory shock receiving mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. (2018) 22(1):204. 10.1186/s13054-018-2063-4

102.

Fuest KE Ulm B Daum N Lindholz M Lorenz M Blobner K et al Clustering of critically ill patients using an individualized learning approach enables dose optimization of mobilization in the ICU. Crit Care. (2023) 27(1):1. 10.1186/s13054-022-04291-8

103.

Chen B Pang QY An R Liu HL . A systematic review of risk factors for postinduction hypotension in surgical patients undergoing general anesthesia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2021) 25(22):7044–50.

104.

Merdji H Long MT Ostermann M Herridge M Myatra SN De Rosa S et al Sex and gender differences in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. (2023) 49(10):1155–67. 10.1007/s00134-023-07194-6

105.

von Wedel D Redaelli S Jung B Baedorf-Kassis EN Schaefer MS . Higher mortality in female versus male critically ill patients at comparable thresholds of mechanical power: necessity of normalization to functional lung size. Intensive Care Med. (2025) 51:624–6. 10.1007/s00134-024-07761-5

106.

von Wedel D Redaelli S Wachtendorf LJ Ahrens E Rudolph MI Shay D et al Association of anaesthesia provider sex with perioperative complications: a two-centre retrospective cohort study. Br J Anaesth. (2024) 133(3):628–36. 10.1016/j.bja.2024.05.016

107.

Duceppe E Lussier AR Beaulieu-Dore R LeManach Y Laskine M Fafard J et al Preoperative antihypertensive medication intake and acute kidney injury after major vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. (2018) 67(6):1872–1880.e1. 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.065

108.

Ling Q Gu Y Chen J Chen Y Shi Y Zhao G et al Consequences of continuing renin angiotensin aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. (2018) 18(1):26. 10.1186/s12871-018-0487-7

109.

Giannas E Patel A Dias P Heath RJ Sinclair R Surman K et al Perioperative management of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in patients undergoing elective major noncardiac surgery: a mixed model investigation using systematic review, meta-analysis, multicentre service evaluation, and national survey. Br J Anaesth. (2025) 135:861–9. 10.1016/j.bja.2025.06.026

110.

Ackland GL Patel A Abbott TEF Begum S Dias P Crane DR et al Discontinuation vs. Continuation of renin-angiotensin system inhibition before non-cardiac surgery: the SPACE trial. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(13):1146–55. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad716

111.

Nürnberger C Widmann J Habicher M Kenz M Schmidt G Reese J-P et al Perioperative inter-, interdisciplinary, inter-sectoral process optimization in heart failure: a multicenter, prospective randomized controlled intervention study (PeriOP-CARE HF). ClinicalTrialsgov. (2024).

Summary

Keywords

intraoperative hypotension, preoperative risk factors, patient characteristics, perioperative management, cardiovascular risk, meta-analysis

Citation

Daum N, Bill D, Thiele M, Felber J, von Wedel D, Spies C, Balzer F, Mörgeli R, Hunsicker O, Müller A, Contag D, Pohrt A, Bald A, Kayser M, Treskatsch S and Markus M (2025) Preoperative patient risk factors for intraoperative hypotension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1709004. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1709004

Received

19 September 2025

Revised

15 November 2025

Accepted

20 November 2025

Published

05 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Hong Liu, UC Davis Health, United States

Reviewed by

Christian Bohringer, UC Davis Medical Center, United States

Cristina Barboi, Indiana University Hospital, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Daum, Bill, Thiele, Felber, von Wedel, Spies, Balzer, Mörgeli, Hunsicker, Müller, Contag, Pohrt, Bald, Kayser, Treskatsch and Markus.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Maximilian Markus maximilian.markus@charite.de

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.