Abstract

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited arrhythmia disorder and a major cause of sudden cardiac death below 50 years. Despite more than three decades of research, diagnosis and risk prediction remain challenging due to variable presentation and incomplete understanding of its genetic basis. The Brugada electrocardiographic pattern is central to diagnosis but lacks specificity, while different scoring systems offer structured assessment yet perform inconsistently in asymptomatic or intermediate-risk patients. SCN5A is the only gene with definitive evidence for causality, but incomplete penetrance and polygenic effects limit its clinical utility. Important gaps remain, including the low diagnostic yield of genetic testing, the unclear course of asymptomatic BrS patients with spontaneous type I electrocardiographic pattern and in geno-negative BrS patients, and the limited validation of current risk models. In this mini review, we explore these challenges and discuss new directions, that could move the field toward more accurate and personalized management.

Introduction

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited primary electrical disorder, characterized by ST-segment elevation and T-wave inversion in the right precordial leads, particularly V1 and V2 (1, 2). First described by the Brugada brothers in 1992, the syndrome was recognized in eight patients, including two siblings, who presented with recurrent aborted sudden death in the absence of structural heart disease, exhibiting a coved-type ST-segment elevation, right bundle branch block, and normal QT interval (3, 4). Since then, BrS has been established as a major cause of arrhythmic death in young, otherwise healthy individuals (5–7).

While most BrS patients remain asymptomatic, some may present with ventricular fibrillation (VF), arrhythmic syncope (typically at rest or during fever), or atrial fibrillation in structurally normal hearts (8). The condition predominantly affects males, with the first episode of VF typically occurring at a mean age of 41 ± 15 years (2). However, BrS is phenotypically dynamic, and subtle or concealed patterns can complicate diagnosis. Even when diagnosis is achieved, accurate risk stratification is a major challenge, yet critical for guiding management regarding lifestyle advice, medication, ablation and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy (9). Both clinical and genetic factors contribute to risk assessment, but the optimal integration of these determinants remains an active area of investigation.

This mini review provides a concise overview of current knowledge on BrS risk prediction, focusing on clinical stratification tools, genetic contributions, and highlighting novel approaches to support precision risk assessment and individualized management.

Diagnostic evaluation and risk stratification systems in Brugada syndrome

Diagnosis of BrS requires a type 1 Brugada electrocardiographic (ECG) pattern, which may be spontaneous or transient. Other conditions that may mimic this, must be excluded. Pharmacological provocation with sodium channel blockers (SCB) or fever can unmask a type 1 pattern. An induced pattern is considered less specific, as it occurs in 2%–4% of healthy individuals and at higher prevalence in patients with other arrhythmia substrates (10). Pharmacological provocation remains central in uncovering concealed BrS, but the selection of who to test and its interpretation requires caution, and standardized protocols are still evolving (11). Therefore, confirmation of BrS requires accompanying clinical features, such as documented ventricular arrhythmia (VA), syncope, or a relevant family history (1).

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) may be the first manifestation of BrS. Systematic evaluation of the survivors and their relatives is essential to identify underlying inherited conditions. In a cohort of 155 nonischemic SCA survivors and 282 relatives, systematic evaluation identified an inherited cardiac disease in 49% of probands (including seven cases of BrS) and 15% of relatives (including one case of BrS type 1) (12). Most probands received ICDs, and relatives benefited from genetic counseling and early management. These findings emphasize the importance of systematic work-up for early diagnosis and targeted intervention.

Predicting future arrhythmic risk remains challenging, particularly in asymptomatic patients or those with borderline findings. To address this, several diagnostic and risk stratification scoring systems have been developed on identifying high-risk patients (13–17) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Overview of risk stratification models in Brugada syndrome. ECG, electrocardiogram; EPS, electrophysiological study; VA, ventricular arrhythmia; SCD, sudden cardiac death; PAT, Predicting Arrhythmic evenT.

The Shanghai Score was established in 2017 to address concerns about overdiagnosis, particularly due to false-positive SCB testing in healthy individuals (11, 12) This point-based system incorporates a positive history of 1) suspected arrhythmogenic syncope, 2) early onset of atrial fibrillation/flutter, 3) nocturnal agonal respiration, 4) documented VF/polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT), 5) positive genotype (SCN5A), 6) definite BrS in first- or second-degree family members and 7) family history of sudden cardiac death (SCD). Higher cumulative scores indicate probable or definite BrS. A validation study in ∼400 patients with suspected BrS (18) found no malignant VA among patients (∼12% of cohort) with a low score (categorized as either non-diagnostic or possible BrS). The Shanghai Score improves specificity, especially in cases of pharmacologically induced type 1 ECG, but requires careful documentation of phenotypic and family history details.

Sieira score was among the first, estimating event free survival at 1, 5 and 10 years following diagnosis (15), yet its predictive accuracy was limited (19–21). To improve this, the BRUGADA-RISK model was developed (22) based on a multicenter study of 1,100 patients with BrS, 906 of whom were asymptomatic. A total of 114 patients experienced primary endpoints of VA or SCD. VA was defined as aborted SCD or documented sustained VT/VF on monitoring or ICD interrogation. The model was validated using out-of-sample cross-validation. The study proposed four significant risk factors: probable arrhythmia-related syncope, or ECG changes including either spontaneous type 1 BrS morphology, the revelation of type 1 BrS pattern during elevated leads test, and presence of early repolarization pattern in the peripheral leads. Point values were weighted based on their individual predictive power. The cumulative score translates directly into a patient's estimated 5-year risk of VA or SCD. However, this model faced criticism for outcome bias by including appropriate ICD therapies in addition to SCD as primary endpoints, potentially overestimating SCD risk since not all ICD-terminated arrhythmias are fatal. Such limitations warrant careful consideration in clinical practice (21).

The latest advancement is the Predicting Arrhythmic evenT (PAT) score, derived from a worldwide pooled analysis of 7,358 patients (23). Fifteen of 23 identified risk factors were significant, and their pooled odds ratios formed the basis of the scoring system. Internal and external validation showed superior discrimination compared with BRUGADA-RISK, Shanghai Score, and Sieira score. A PAT score ≥10 predicted the first major arrhythmic event with 95.5% sensitivity and 89.1% specificity, making it a promising tool for primary prevention in BrS.

Beyond scoring systems, various diagnostic modalities have been evaluated for their ability to identify high-risk patients. Delise et al. proposed the use of electrophysiological studies (EPS) as part of a multiparametric approach (14). However, EPS and its diagnostic utility is considered controversial, especially among asymptomatic patients (10, 24, 25). This is supported by a systematic review by Mascia et al., who evaluated 1,318 patients with drug-induced type-1 pattern undergoing EPS. No significant difference in arrhythmic events was observed between EPS positive-, negative-, or non-studied groups over a mean follow-up of 5.1 years, suggesting that EPS may have limited prognostic value in this subgroup (26).

To refine substrate assessment, Letsas et al. (17) applied high-density electroanatomical mapping and identified epicardial abnormalities in the right ventricular outflow tract. Low-voltage areas effectively distinguished symptomatic from asymptomatic patients, indicating the value of this mapping technique for identifying high-risk patients.

Despite advances, stratifying SCD risk in asymptomatic and intermediate-risk individuals poses ongoing challenges (24). Wilde et al. (21) recently highlighted key methodological limitations: surrogate endpoints may overestimate actual risk, and most models are static, failing to account for changes in risk over time. The authors advocate for disease-specific surrogate endpoints and dynamic risk models that better reflect individual risk.

The evolving genetics of Brugada syndrome

Although BrS is recognized as a heritable disorder, the diagnostic yield of genetic testing remains relatively low, limiting its utility in risk stratification and clinical decision-making.

Currently, a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant is identified in approximately 20% of clinically diagnosed BrS patients (27, 28), leaving the majority genetically unexplained (29, 30). Historically, more than 20 genes were proposed to be associated with BrS. However, following the systematic re-evaluation of gene-disease-associations by the Clinical Genome Resource (31), only one gene, SCN5A, has been determined to have definite evidence for causality (32, 33). Other implicated genes have either been shown to be too prevalent in the general population to be causal or have insufficient evidence, and are therefore considered of disputed significance (4, 31).

SCN5A encodes the pore-forming α-subunit of Nav1.5, which is a voltage-gated sodium channel responsible for the inward sodium current in excitable cells (34). Loss-of-function (LOF) variants in SCN5A are the only established genetic mechanism of BrS, resulting in Nav1.5 channel dysfunction or reduced expression, producing the characteristic conduction abnormalities (35, 36). While inheritance patterns are often described as autosomal dominant, it has been shown that the genetic influence is more nuanced and with ethnic differences (37).

Notably, genotype-phenotype discrepancies are common. In families with SCN5A variants, individuals negative for the familial variant may still express the typical ECG phenotype, while some carriers remain lifelong asymptomatic (4, 38). SCN5A variants also overlap with other inherited cardiac diseases and syndromes, emphasizing the need to interpret genetic results within the context of the phenotype and family history (28, 36, 39). Despite these challenges, the presence of a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in SCN5A has prognostic implications: carriers tend to experience the first arrhythmic event at an earlier age than genotype-negative patients, and predicted LOF variants have been indicated to be a predictor of VA risk in BrS patients (27, 40–42). Mechanistic insights have further refined our understanding of how SCN5A variants influence phenotype expression: Using combined genetic and high-density epicardial mapping, Ciconte et al. (43) demonstrated that SCN5A variant carriers exhibit a larger epicardial arrhythmogenic substrate, prolonged electrograms, and higher prevalence of spontaneous type I ECG and VT/VF events than non-carriers. These findings provide strong evidence that SCN5A loss-of function is not only a molecular marker but also a determinant of structural electrical remodeling in BrS.

Recent studies indicate that BrS is often more complex than a simple monogenic disorder. The combination of incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity and genotype-negative phenotypes suggest a multifactorial, polygenic model, where both rare and common genetic variants contribute to genetic susceptibility. Genome-wide association studies, have identified several common variants at loci including SCN10A and HEY2 that modulate BrS risk and may explain phenotypic variability (37, 44–47), but have not been shown to benefit the clinic care (48).

Clinical integration of genetic testing requires caution. Targeted genetic testing is recommended primarily for diagnosed patients, as it can inform cascade family screening and facilitate early identification of at-risk relatives (49). Both the 2011 and 2022 Expert Consensus documents advocate genetic counselling for probands and family members when a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant is detected (50, 51).

Discussion

Integrating clinical, genetic, and electrophysiological perspectives

More than 30 years after its first description, BrS diagnosis and prognosis are still surrounded by controversy. Clinical presentation ranges from SCA to complete absence of symptoms. Genetics adds another layer of complexity. Some authors caution against overinterpreting genetic findings in risk stratification, particularly since many carriers remain asymptomatic, and many patients lack identifiable variants (30). Others see potential in refining genetic interpretation by focusing on variant location within SCN5A or integrating polygenic risk scores, which may provide a more nuanced estimate of arrhythmic risk (48). In this context, Kukavica et al. (52) recently demonstrated showed that male sex, the type of SCN5A variant, and a BrS-specific polygenic risk score are each associated with arrhythmic risk. Together, these factors form a nonmodifiable risk profile that helps identify patients at higher risk regardless of symptoms or ECG pattern.

The clinical implications of these mechanistic links were underscored by Santinelli et al. (53), who prospectively followed symptomatic BrS patients receiving ICDs with or without epicardial ablation. Substrate size, SCN5A status, and prior cardiac arrest independently predicted VF recurrence. Epicardial ablation combined with ICD implantation reduced arrhythmic events over long-term follow-up. Together, these findings bridge the gap between genetics and therapy, suggesting that SCN5A variants might identify patients with a more extensive substrate who may derive particular benefit from epicardial ablation.

Limitations of current risk stratification

Risk stratification in BrS relies on multiparametric tools including clinical risk scores, EPS and emerging procedural assessments (54, 55). Current risk models often include small cohorts, heterogeneous inclusion criteria, and limited validation, making the prediction of arrhythmic events challenging (54, 55). The type 1 ECG pattern, although diagnostic, can fluctuate due to lead placement, autonomic tone, fever or drug provocation. Lead placement and SCB dosing protocols currently vary across centers, and the latest consensus could not issue unified recommendations due to limited evidence. Other ECG markers, such as the aVR sign or fragmented QRS complexes, have been suggested to identify higher-risk patients, but results are inconsistent across studies and populations, leaving some uncertainty in interpretation (56).

The natural history of phenotype positive-genotype negative individuals is poorly understood, complicating recommendations for monitoring, lifestyle modifications, or preventive interventions (4, 29). Many centers lack multidisciplinary teams to provide comprehensive genetic counseling, including discussions of penetrance, inheritance, and individualized risk (30, 57). In sports cardiology, determining eligibility is particularly tricky, as most BrS individuals may safely compete, but only after careful evaluation (58).

Future directions

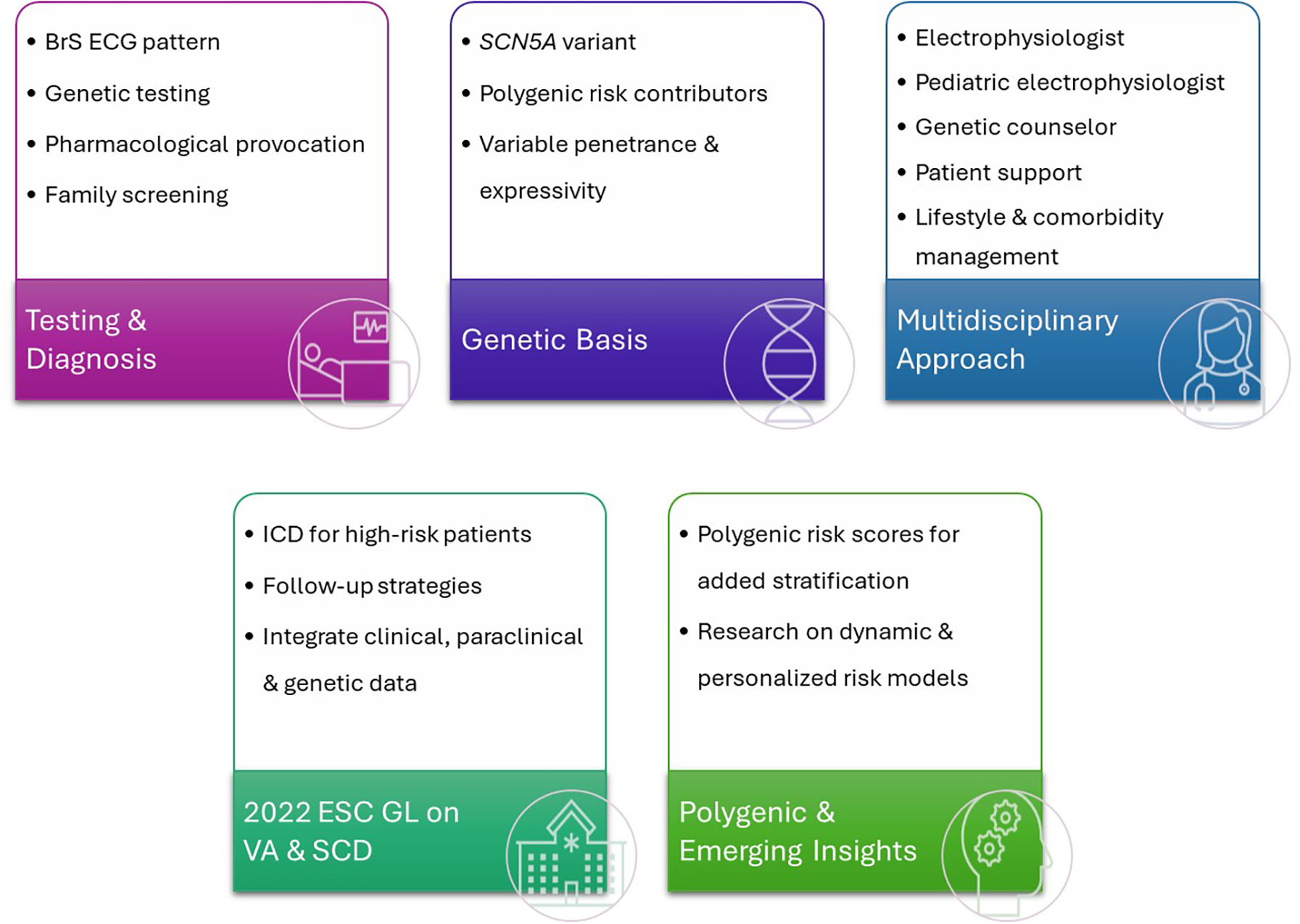

Future management strategies are likely to be increasingly personalized (Figure 2). Emerging research should focus on exploring ways to directly target the underlying genetic defects. Using advanced genetic tools such as CRISPR or allele-specific silencing, delivered through heart-targeted viral vectors, may offer a transition from symptomatic management toward potentially curative strategies (57, 59). The selection of BrS patients for gene treatment and when to initiate the gene treatment remains elusive.

Figure 2

Comprehensive approach to Brugada syndrome. BrS, Brugada syndrome; ECG, electro; SCN5A, gene; VA, ventricular arrhythmia; SCD, sudden cardiac death; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; GL, guidelines.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is another promising avenue. Early studies show how AI can reliably detect BrS patterns, raising the possibility of non-invasive screening and early risk identification (60). At a population level, large genomic datasets combined with AI and polygenic modeling could support predictive testing for SCD-associated SCN5A variants, enabling preventive strategies before symptoms appear, though careful ethical and familial considerations remain essential (57).

Finally, procedural approaches, such as right ventricular outflow tract epicardial ablation, may eventually provide alternatives to ICD implantation in select high-risk patients, particularly when devices carry added risk (61).

Limitations of this review

While this mini review summarizes recent advances in BrS risk prediction and genetics, it is limited by the selective focus. Some studies discussed are based on heterogeneous patient populations or surrogate outcomes, which may restrict generalizability.

Conclusion

BrS is moving toward a personalized, precision-medicine approach, integrating the clinical scenario, genetics, advanced ECG analytics, and targeted therapies. While controversies and gaps persist, these emerging tools offer real potential to improve early detection, refine risk stratification, and optimize management and ultimately reduce the burden of SCD while minimizing unnecessary interventions.

Statements

Author contributions

PB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SJ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JT-H: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Priori SG Wilde AA Horie M Cho Y Behr ER Berul C et al HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm. (2013) 10(12):1932–63. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.014

2.

Mizusawa Y Wilde AAM . Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2012) 5(3):606–16. 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.964577

3.

Brugada P Brugada J . Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. JACC. (1992) 20(6):1391–6. 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-J

4.

Behr ER Ben-Haim Y Ackerman MJ Krahn AD Wilde AAM . Brugada syndrome and reduced right ventricular outflow tract conduction reserve: a final common pathway?Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(11):1073–81. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa1051

5.

Minier M Probst V Berthome P Tixier R Briand J Geoffroy O et al Age at diagnosis of Brugada syndrome: influence on clinical characteristics and risk of arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm. (2020) 17(5):743–9. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.11.027

6.

Tfelt-Hansen J Winkel BG Grunnet M Jespersen T . Cardiac channelopathies and sudden infant death syndrome. Cardiology. (2011) 119(1):21–33. 10.1159/000329047

7.

Nakano Y Shimizu W . Brugada syndrome as a major cause of sudden cardiac death in Asians. JACC Asia. (2022) 2(4):412–21. 10.1016/j.jacasi.2022.03.011

8.

Bergonti M Sacher F Belhassen B Sarquella-Brugada G Arbelo E Sabbag A et al The clinical significance of atrial fibrillation in non–high-risk Brugada syndrome: the BruFib study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2025) 11(11):2471–80. 10.1016/j.jacep.2025.06.031

9.

Tfelt-Hansen J Garcia R Albert C Merino J Krahn A Marijon E et al Risk stratification of sudden cardiac death: a review. EP Eur. (2023) 25(8):euad203. 10.1093/europace/euad203

10.

Zeppenfeld K Tfelt-Hansen J de Riva M Winkel BG Behr ER Blom NA et al 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43(40):3997–4126. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262

11.

Behr ER Winkel BG Ensam B Alfie A Arbelo E Berry C et al The diagnostic role of pharmacological provocation testing in cardiac electrophysiology: a clinical consensus statement of the European heart rhythm association and the European association of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions (EAPCI) of the ESC, the ESC working group on cardiovascular pharmacotherapy, the Association of European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), the Paediatric & Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES), the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace. (2025) 27(4):euaf067. 10.1093/europace/euaf067

12.

Jacobsen EM Hansen BL Kjerrumgaard A Tfelt-Hansen J Hassager C Kjaergaard J et al Diagnostic yield and long-term outcome of nonischemic sudden cardiac arrest survivors and their relatives: results from a tertiary referral center. Heart Rhythm. (2020) 17(10):1679–86. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.06.030

13.

Kawazoe H Nakano Y Ochi H Takagi M Hayashi Y Uchimura Y et al Risk stratification of ventricular fibrillation in Brugada syndrome using noninvasive scoring methods. Heart Rhythm. (2016) 13(10):1947–54. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.07.009

14.

Delise P Allocca G Marras E Giustetto C Gaita F Sciarra L et al Risk stratification in individuals with the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern without previous cardiac arrest: usefulness of a combined clinical and electrophysiologic approach. Eur Heart J. (2011) 32(2):169–76. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq381

15.

Sieira J Conte G Ciconte G Chierchia GB Casado-Arroyo R Baltogiannis G et al A score model to predict risk of events in patients with Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38(22):1756–63. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx119

16.

Subramanian M Prabhu MA Rai M Harikrishnan MS Sekhar S Pai PG et al A novel prediction model for risk stratification in patients with a type 1 Brugada ECG pattern. J Electrocardiol. (2019) 55:65–71. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2019.04.006

17.

Letsas KP Vlachos K Conte G Efremidis M Nakashima T Duchateau J et al Right ventricular outflow tract electroanatomical abnormalities in asymptomatic and high-risk symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome: evidence for a new risk stratification tool? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2021) 32(11):2997–3007. 10.1111/jce.15262

18.

Kawada S Morita H Antzelevitch C Morimoto Y Nakagawa K Watanabe A et al Shanghai score system for diagnosis of Brugada syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2018) 4(6):724–30. 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.02.009

19.

Chow JJ Leong KMW Yazdani M Huzaien HW Jones S Shun-Shin MJ et al A multicenter external validation of a score model to predict risk of events in patients with Brugada syndrome. Am J Cardiol. (2021) 160:53–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.08.035

20.

Wei H Liu W Ma YR Chen S . Performance of multiparametric models in patients with Brugada syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:859771. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.859771

21.

van der Heide MYC Verstraelen TE Wilde AAM . Personalized sudden cardiac death risk prediction in genetic heart diseases: beyond one-size-fits-all. Heart Rhythm. (2025). (in press). 10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.07.041

22.

Honarbakhsh S Providencia R Garcia-Hernandez J Martin CA Hunter RJ Lim WY et al A primary prevention clinical risk score model for patients with Brugada syndrome (BRUGADA-RISK). JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2020) 7(2):210–22. 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.08.032

23.

Rattanawong P Mattanapojanat N Mead-Harvey C Van Der Walt C Kewcharoen J Kanitsoraphan C et al Predicting arrhythmic event score in Brugada syndrome: worldwide pooled analysis with internal and external validation. Heart Rhythm. (2023) 20(10):1358–67. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.06.013

24.

Probst V Goronflot T Anys S Tixier R Briand J Berthome P et al Robustness and relevance of predictive score in sudden cardiac death for patients with Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(17):1687–95. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa763

25.

Rodríguez-Mañero M Baluja A Hernández J Muñoz C Calvo D Fernández-Armenta J et al Validation of multiparametric approaches for the prediction of sudden cardiac death in patients with Brugada syndrome and electrophysiological study. Rev Esp Cardiol Engl Ed. (2022) 75(7):559–67. 10.1016/j.rec.2021.07.007

26.

Mascia G Brugada J Barca L Benenati S Della Bona R Scarà A et al Prognostic significance of electrophysiological study in drug-induced type-1 Brugada syndrome: a brief systematic review. J Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 25(11):775. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000001665

27.

Pannone L Bisignani A Osei R Gauthey A Sorgente A Monaco C et al Genetic testing in Brugada syndrome: a 30-year experience. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2024) 17(4):e012374. 10.1161/CIRCEP.123.012374

28.

Wilde AAM Semsarian C Márquez MF Shamloo AS Ackerman MJ Ashley EA et al European Heart rhythm association (EHRA)/heart rhythm society (HRS)/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS)/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for cardiac diseases. Europace. (2022) 24(8):1307–67. 10.1093/europace/euac030

29.

Campuzano O Grassi S Martínez-Barrios E Greco A Arena V Sarquella-Brugada G et al Brugada syndrome in the forensic field: what do we know to date? Front Cardiovasc Med. (2025) 12:1618762. 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1618762

30.

Tuijnenburg F Amin AS Wilde AAM . Inherited arrhythmia syndromes - cardiogenetics. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. (2025) 25(4):255–62. 10.1016/j.ipej.2025.07.004

31.

Rehm HL Berg JS Brooks LD Bustamante CD Evans JP Landrum MJ et al Clingen–the clinical genome resource. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372(23):2235–42. 10.1056/NEJMsr1406261

32.

Hosseini SM Kim R Udupa S Costain G Jobling R Liston E et al Reappraisal of reported genes for sudden arrhythmic death. Circulation. (2018) 138(12):1195–205. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035070

33.

Baruteau AE Kyndt F Behr ER Vink AS Lachaud M Joong A et al SCN5A mutations in 442 neonates and children: genotype–phenotype correlation and identification of higher-risk subgroups. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39(31):2879–87. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy412

34.

Veerman CC Wilde AAM Lodder EM . The cardiac sodium channel gene SCN5A and its gene product NaV1.5: role in physiology and pathophysiology. Gene. (2015) 573(2):177–87. 10.1016/j.gene.2015.08.062

35.

Li KHC Lee S Yin C Liu T Ngarmukos T Conte G et al Brugada syndrome: a comprehensive review of pathophysiological mechanisms and risk stratification strategies. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. (2020) 26:100468. 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100468

36.

Tfelt-Hansen J Winkel BG Grunnet M Jespersen T . Inherited cardiac diseases caused by mutations in the Nav1.5 sodium channel. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2010) 21(1):107–15. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01633.x

37.

Makarawate P Glinge C Khongphatthanayothin A Walsh R Mauleekoonphairoj J Amnueypol M et al Common and rare susceptibility genetic variants predisposing to Brugada syndrome in Thailand. Heart Rhythm. (2020) 17(12):2145–53. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.06.027

38.

Probst V Wilde AAM Barc J Sacher F Babuty D Mabo P et al SCN5A mutations and the role of genetic background in the pathophysiology of Brugada syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. (2009) 2(6):552–7. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.853374

39.

Winkel BG Larsen MK Berge KE Leren TP Nissen PH Olesen MS et al The prevalence of mutations in KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A in an unselected national cohort of young sudden unexplained death cases. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2012) 23(10):1092–8. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2012.02371.x

40.

Milman A Behr ER Gray B Johnson DC Andorin A Hochstadt A et al Genotype-phenotype correlation of SCN5A genotype in patients with Brugada syndrome and arrhythmic events: insights from the SABRUS in 392 probands. Circ Genomic Precis Med. (2021) 14(5):e003222. 10.1161/CIRCGEN.120.003222

41.

Aizawa T Makiyama T Huang H Imamura T Fukuyama M Sonoda K et al SCN5A variant type-dependent risk prediction in Brugada syndrome. EP Eur. (2025) 27(2):euaf024. 10.1093/europace/euaf024

42.

Yamagata K Horie M Aiba T Ogawa S Aizawa Y Ohe T et al Genotype-phenotype correlation of SCN5A mutation for the clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics of probands with Brugada syndrome. Circulation. (2017) 135(23):2255–70. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027983

43.

Ciconte G Monasky MM Santinelli V Micaglio E Vicedomini G Anastasia L et al Brugada syndrome genetics is associated with phenotype severity. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(11):1082–90. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa942

44.

Barc J Tadros R Glinge C Chiang DY Jouni M Simonet F et al Genome-wide association analyses identify novel Brugada syndrome risk loci and highlight a new mechanism of sodium channel regulation in disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. (2022) 54(3):232–9. 10.1038/s41588-021-01007-6

45.

Juang J-MJ Liu YB Chen C-YJ Yu QY Chattopadhyay A Lin LY et al Validation and disease risk assessment of previously reported genome-wide genetic variants associated with Brugada syndrome. Circ Genomic Precis Med. (2020) 13(4):e002797. 10.1161/CIRCGEN.119.002797

46.

Ishikawa T Masuda T Hachiya T Dina C Simonet F Nagata Y et al Brugada syndrome in Japan and Europe: a genome-wide association study reveals shared genetic architecture and new risk loci. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(26):2320–32. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae251

47.

Bezzina CR Barc J Mizusawa Y Remme CA Gourraud JB Simonet F et al Common variants at SCN5A-SCN10A and HEY2 are associated with Brugada syndrome, a rare disease with high risk of sudden cardiac death. Nat Genet. (2013) 45(9):1044–9. 10.1038/ng.2712

48.

Litt M Deo R . Brugada syndrome risk stratification: selecting the population of interest. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2024) 84(21):2099–101. 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.08.076

49.

Cutler MJ Eckhardt LL Kaufman ES Arbelo E Behr ER Brugada P et al Clinical management of Brugada syndrome: commentary from the experts. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2024) 17(1):e012072. 10.1161/CIRCEP.123.012072

50.

Ackerman MJ Priori SG Willems S Berul C Brugada R Calkins H et al HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies: this document was developed as a partnership between the heart rhythm society (HRS) and the European heart rhythm association (EHRA). EP Eur. (2011) 13(8):1077–109. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.05.020

51.

Zeljkovic I Gauthey A Manninger M Malaczynska-Rajpold K Tfelt-Hansen J Crotti L et al Genetic testing for inherited arrhythmia syndromes and cardiomyopathies: results of the European heart rhythm association survey. Europace. (2024) 26(9):euae216. 10.1093/europace/euae216

52.

Kukavica D Trancuccio A Mazzanti A Napolitano C Morini M Pili G et al Nonmodifiable risk factors predict outcomes in Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2024) 84(21):2087–98. 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.07.037

53.

Santinelli V Ciconte G Manguso F Anastasia L Micaglio E Calovic Z et al High-risk Brugada syndrome: factors associated with arrhythmia recurrence and benefits of epicardial ablation in addition to implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation. EP Eur. (2024) 26(1):euae019. 10.1093/europace/euae019

54.

Moore BM Roston TM Laksman Z Krahn AD . Updates on inherited arrhythmia syndromes (Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome, CPVT, ARVC). Prog Cardiovasc Dis. (2025) 91:130–43. 10.1016/j.pcad.2025.06.002

55.

Gomes DA Lambiase PD Schilling RJ Cappato R Adragão P Providência R . Multiparametric models for predicting major arrhythmic events in Brugada syndrome: a systematic review and critical appraisal. Europace. (2025) 27(5):euaf091. 10.1093/europace/euaf091

56.

Brugada J . Searching for the holy grail in risk stratification in patients with Brugada syndrome. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. (2025) 25(4):235. 10.1016/j.ipej.2025.08.004

57.

Dewars ER Landstrom AP . The genetic basis of sudden cardiac death: from diagnosis to emerging genetic therapies. Annu Rev Med. (2025) 76:283–99. 10.1146/annurev-med-042423-042903

58.

Scarà A Sciarra L Russo AD Cavarretta E Palamà Z Zorzi A et al Brugada syndrome in sports cardiology: an expert opinion statement of the Italian society of sports cardiology (SICSport). Am J Cardiol. (2025) 244:9–17. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2025.02.031

59.

Xie X Chen Y Li Z Sun Y Chen G . Genetic basis of Brugada syndrome. Biomedicines. (2025) 13(7):1740. 10.3390/biomedicines13071740

60.

Barbosa LM Mazetto R Defante MLR Antunes VLJ Oliveira VMR Cavalcante D et al A systematic review and meta-analysis of artificial intelligence ECGs performance in the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2025). 10.1007/s10840-025-02075-y

61.

Belhassen B Milman A . Theory and practice of present clinical use of quinidine in the management of cardiac arrhythmias. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. (2025) 25(4):264–73. 10.1016/j.ipej.2025.07.017

Summary

Keywords

arrhythmia, arrhythmic syncope, atrial fibrillation, Brugada syndrome, BRUGADA-RISK model, electrocardiographic pattern, SCN5A , Shanghai score

Citation

Bhardwaj P, Stavnem D, Jacobsen SB, Winkel BG and Tfelt-Hansen J (2025) Current perspectives on risk prediction and genetic basis of Brugada syndrome. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1722105. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1722105

Received

10 October 2025

Revised

27 November 2025

Accepted

28 November 2025

Published

12 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Vincenzo Santinelli, IRCCS San Donato Polyclinic, Italy

Reviewed by

Irene Paula Popa, Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Bhardwaj, Stavnem, Jacobsen, Winkel and Tfelt-Hansen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Priya Bhardwaj priya.kumar.bhardwaj@regionh.dk

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.