- 1Arcadis, U.S., Inc., Wakefield, MA, United States

- 2Town of Nantucket Natural Resources Department, Nantucket, MA, United States

Nantucket, an island about 30 miles off the coast of Massachusetts, has long embraced retreat in response to coastal hazards. This community case study examines how Nantucket is enhancing its resilience by adapting to increasing coastal storms, erosion, and sea level rise through strategic retreat and relocation. Nantucketers have historically moved structures such as lighthouses and homes away from the coastline, but the increasing frequency and intensity of storms demand more comprehensive and adaptable solutions. Through resilience planning and policy efforts, the Town of Nantucket is addressing these challenges by balancing short- and long-term objectives, public and private interests, and equity considerations. Lessons learned from Nantucket’s experiences are applicable to other communities facing similar coastal risks, highlighting the importance of strategic planning, community support, and capacity building for effective retreat and relocation.

Introduction

Nantucket is no stranger to the concept of retreat. Since the island was settled, Nantucketers have been grappling with coastal hazards which, in many ways, are an accepted part of island life. Formed after the retreat of the Laurentide ice sheet, most of the island is composed of glacial outwash materials, including sand and gravel, which are especially prone to erosion (USGS, n.d.). Over time, Nantucketers have adapted to coastal hazards by moving lighthouses, homes, roads, utilities, and other structures away from the coastline in both managed (i.e., planned) and emergency situations. However, with climate change, coastal storms are increasing in frequency and intensity and erosion of the island’s bluffs, dunes, and beaches is becoming more rapid with sea level rise, bringing storm surge impacts to Nantucketers’ front doors and threatening their homes, infrastructure, and natural resources.

This community case study explores how, in the context of broader resilience planning and policy, the Town of Nantucket (the Town) is navigating the complexities of managed retreat. Different coastal hazards dominate across the island, necessitating a variable approach to planning for retreat and relocation. Along Nantucket’s Baxter Road, atop the Siasconset (‘Sconset) bluffs, retreat is unfolding in real time. Over time, the area on top of the bluffs has been developed and now faces an uncertain future. While the debate over the best long-term plan for erosion along Baxter Road continues, the Town is balancing varied and competing interests including near- and long-term objectives, public and private priorities, and considerations including equity and evolving science. In the historic Downtown, nuisance flooding is a regular reminder of the vulnerability of Nantucket’s economic core, prompting near- and long-term planning efforts and challenging conversations about the balance between preservation and adaptation. Meanwhile, on the south shore, erosion imminently threatens the island’s wastewater treatment facility, triggering emergency responses while a long-term approach is developed. Though the relatively high ground found mid-island may, in some ways, be ideal for relocation, the island’s history of conservation and fraught relationship with densification pose challenges.

To build a resilient future that embodies Nantucket’s unique history and built heritage, supports healthy coastal and ecological resources, and bolsters thriving communities, a comprehensive, adaptable, and community-supported approach is necessary. Beginning with the 2019 update of their local hazard mitigation plan, 2021 release of the Town’s first Coastal Resilience Plan (CRP), and with half of the CRP’s recommendations complete or underway as of July 2024, the Town has laid the groundwork for upcoming strategic retreat and relocation planning efforts. Lessons learned so far on Nantucket are widely applicable to other communities as they build the policy and funding pathways, capacity, and community support required of coastal retreat.

Island context

More recently known as a vacation spot for the wealthy and elite, Nantucket’s focus on tourism is a relatively new chapter in its rich history. Home to indigenous peoples for thousands of years, the island was more recently home to the Wampanoag. After the island was settled by the English in 1659, the settlers turned to whaling, learning from and utilizing the labor of the Wampanoag who had long harvested stranded whales as a valuable source of fat and meat (Harrison, n.d.). From the 1690s until the 1850s, whaling was the primary business on Nantucket, enabling the growth of industry, accumulation of wealth and expansion of the island’s population. In the mid-1800s, a variety of factors led to the whaling industry’s decline, notably including the formation of sand bars near the entrance to Nantucket Harbor which made passage difficult for the larger vessels necessary for offshore whaling following the collapse of nearshore populations (Stackpole and Harrison, n.d.).

For nearly 50 years after the decline of the whaling industry, the island experienced significant population decline, leaving Colonial-era residences and other structures neglected. In 1894, the Nantucket Historical Association was founded and began leading efforts to preserve the island’s historic structures, establishing the foundation of the island’s ongoing legacy of historic preservation. In 1955, Nantucket established a local historic district which was ultimately expanded to cover Nantucket County including Nantucket, Muskeget and Tuckernuck islands. In 1966, the local historic district was designated a National Historic Landmark.

Though tourism initially helped support the island’s recovery after the fall of the whaling industry, preservation efforts in the mid-20th century supported further growth of the industry as visitors were attracted to the island’s natural beauty and historic charm. Today, tourism dominates Nantucket’s seasonal identity with nearly two-thirds of housing units in the County considered “for seasonal, recreational, or occasional use” (US Census Bureau, 2020a).

Though Nantucket’s year-round population is only 14,255 (US Census Bureau, 2020b) the population can swell to over 80,000 during the summer season (Town of Nantucket, n.d.). The racial composition of Nantucket County is analogous to the state of Massachusetts, though the Asian population is smaller (2% on Nantucket vs. 7% in Massachusetts) and a larger share of Nantucketers identify as two or more races or another race (US Census Bureau, 2020b). The median household income for Nantucket County is higher ($135,590 on Nantucket vs. $99,858 in Massachusetts), and the cost of living on island is also higher. Though only 1.1% of Nantucket’s households are classified as limited-English speaking, rates may be much higher during the summer months with the influx of seasonal workers. Nantucket also has higher rates of educational attainment of bachelor’s degrees or higher, higher rates of employment, and lower rates of poverty than Massachusetts (US Census Bureau, 2022).

Though census data offer one lens for understanding the composition of the Nantucket community, it fails to capture the many nuances of year-round Nantucketer’s lived experiences. While Nantucketers face many of the same challenges as communities across the country, including high housing costs and food insecurity, Nantucket’s unique island context exacerbates some of these challenges and introduces others.

With the five-year average median sale price of single-family homes coming in at $2.75 million (Allen, 2023), high housing costs are a consistent challenge for Nantucketers. When considering the high cost of housing, it is notable that on Nantucket there are nearly three times as many homes as there are year-round households. Though supply outpaces year-round demand, housing demand overall is largely divorced from the island’s year-round population due to the substantial demand for vacation homes (University of Massachusetts Amherst Donahue Institute of Economic Public Policy and Research, 2023). Housing prices are subsequently divorced from local salaries, with teachers, police officers, and firefighters earning $70,000–$100,000 annually. Fifteen percent of the fire department lives off-island due to the lack of affordable housing (Lindner, 2023), exposing another layer of the island’s vulnerability and highlighting the challenge of being located 30 miles off the mainland. During the summer season, the issue is further exacerbated with a significant portion of seasonal employees and labor force necessary to support the tourism industry living off-island, commuting approximately 2 h each day via ferry from Hyannis, a port town on Cape Cod. High housing costs also help drive widespread food insecurity. Nationally, one in eight households faces food insecurity. For year-round households on Nantucket, this number is one in three (Lindner, 2024).

Nantucket, named by the Wampanoag tribe, translates to “the faraway land.” 30 miles from the southern coast of Cape Cod, the many cascading risks associated with isolation are a major challenge for Nantucketers, especially within the context of emergency preparedness and response. The island is only reachable by boat or aircraft, with most vehicles, individuals and freight, including essential supplies like food and fuel, arriving via ferry from the mainland. At best, travel from the mainland via ferry takes about 1 h. In the event an emergency on island surpasses the capacity of emergency responders present, there is no immediate lifeline or additional capacity available. Travel time forces the island to be largely self-reliant in emergency situations. When severe weather shuts down operation of the ferries and aircraft, the island is essentially cut-off from the mainland, except for limited emergency services offered by the U.S. Coast Guard and other first responders. Due to the size of the year-round population and the ballooning of the population during the largely concurrent tourism and hurricane seasons, evacuation off the island is not practical or feasible (Town of Nantucket, 2019a).

History of retreat

Since the early days of Nantucket’s inhabitance, the natural environment and coastal hazards have been a consideration in where and how the built environment is established. Traditional indigenous homes on the island were often built into the landscape with reinforcements that offered protection against strong coastal winds (Nantucket Historical Association, n.d.). Sherburne, Nantucket’s original settlement, was once located west of the current Downtown along the north shore near what is now Capaum Pond. By 1730, the Capaum Harbor entrance closed due to longshore drift, spurring the relocation of Downtown to its current location.

More recently, several structures on the island have been relocated in response to coastal hazards (Figure 1). Notably, in 2007 the Sankaty Head Lighthouse was moved over 400 feet away from the shoreline after decades of storms and erosion claimed hundreds of feet of the bluff. Though the lighthouse’s relocation was planned, most of the island’s previous retreats have been unmanaged and reactionary. For example, portions of roadways including Madaket Road and Sheep Pond Road have been retreated following erosion-induced breaches. Though not well-documented, numerous residences, predominantly along the south shore, have also been relocated. Anecdotally, residential relocations have increased over time as erosion rates rise.

Figure 1. Locations of select historic and anticipated Town-led retreat efforts [Basemap by Esri, “World Imagery.” Source: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, and the GIS User Community].

Currently, the Town is exploring questions related to proactive, managed retreat and relocation in three diverse contexts across the island: bluff erosion threatening a roadway and homes along Baxter Road, nuisance flooding threatening the historic Downtown neighborhood, and erosion threatening a critical facility along the south shore (Figure 1). Since 2019, hazard mitigation and resilience planning efforts undertaken by the Town have laid the foundation for productive community conversations around retreat and relocation.

Laying the foundation for retreat and relocation

With approximately 88 miles of shoreline, coastal hazards like flooding, erosion and high winds are, in many ways, an accepted part of island life on Nantucket. While this mindset has influenced how Nantucketers approach emergency preparedness, hazard mitigation, and long-term resilience, recent storms and a growing awareness of climate change impacts have resulted in the increasing recognition that the solutions of the past may not be adequate in the future. The planning efforts described herein are building awareness and capacity within the Town, and the community more broadly, to support conversations about the impacts of coastal hazards on Nantucket and the mounting need for strategic planning around retreat and relocation.

Before 2019, limited efforts explicitly addressed coastal hazards on Nantucket. In 2014, the Town released a Coastal Management Plan to establish priorities and procedures for protecting and managing Town-owned infrastructure and public access points (Town of Nantucket, 2014). In early 2018, Nantucket experienced two major nor’easters and a blizzard. At the time, five of the top 10 flood elevations ever observed on Nantucket were measured in the first 3 months of 2018 (Town of Nantucket, 2019b). Around this time, the Town was in the process of updating their local hazard mitigation plan, as required by 44 CFR 201.6, and recent flood experiences helped shape recommendations to create a new staff position to lead coastal resilience efforts and to develop an island-wide coastal resilience plan.

In early 2019, the Town hosted a Community Resiliency Building workshop to solicit stakeholder participation and input as a part of the Massachusetts Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) program. Funding for this workshop was provided by the MVP program. A key recommendation realized by this effort was the establishment of a municipal resilience coordinator position to facilitate resiliency initiatives across departments and conservation groups on island (Town of Nantucket, 2019a).

As a result of recent flood impacts, ongoing planning efforts, and growing public recognition of increasing climate impacts, the Town appointed a Coastal Resilience Advisory Committee (CRAC) and hired a full time Coastal Resilience Coordinator in spring 2019. Both the CRAC and Coastal Resilience Coordinator played key roles in development of the CRP, as recommended by the 2019 Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan, and continue to drive the implementation of coastal resilience efforts across the island (Town of Nantucket, 2019b).

In January 2020, Nantucket released the Coastal Risk Assessment and Resiliency Strategies Report which provided a cursory review of current and future coastal hazards, evaluated risks within each neighborhood, and made broad recommendations for adaptation (Town of Nantucket, 2020). The report highlighted the range of global and local sea level rise projections available from Federal and State sources. In response, in July 2020, Nantucket’s Select Board adopted the use of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) high sea level rise projections for planning purposes at the recommendation of the CRAC. Recommendations made in this plan also suggested the development of a managed retreat policy, consisting of regulatory and zoning tools, to empower and encourage residential retreat from eroding shorelines.

Building on previous planning efforts, Nantucket launched the CRP planning process in September 2020 to develop a united vision and roadmap for advancing coastal resilience across the island. After a comprehensive resilience planning process, including broad stakeholder engagement and completion of a risk assessment which considers multiple hazards over several time periods, the CRP was released in November 2021. The plan ultimately recommends 40 near- and longer-term resilience approaches and strategies at various scales from island-wide to site-specific. As of July 2024, half of these recommendations have been implemented, are currently underway, or are actively under development.

One of the CRP high priority recommendations is the development and administration of an island-wide approach for pursuing strategic retreat and relocation in areas of highest risk. To help guide near-term decision-making with respect to this recommendation, an island-wide risk framework was developed within the CRP. Recognizing that coastal risk can be complicated, the island-wide risk framework is a decision-making tool developed to guide near-term resilience decisions made on Nantucket based on the results of the risk assessment conducted for the CRP. The framework can be used by private property owners, Town officials, and other decision-makers to determine whether a particular type of resilience approach is appropriate given what is known about the project area’s current and future coastal risk. The goal of this framework is not to prevent new construction across the island but to direct future investment to areas of the island with the lowest coastal risk (Town of Nantucket, 2021).

Over the last 5 years, these various hazard mitigation and resilience planning efforts by the Town have contributed to the development of broad awareness about increasing coastal risks and growing capacity to address these risks within the Town and among Nantucketers more broadly. Creation and maintenance of the CRAC, an entity devoted to implementing the CRP, and the Coastal Resilience Coordinator position have formalized the Town’s capacity to act on issues related to coastal resilience. Through these plans, the Town has also started to introduce retreat to the local vernacular, familiarizing staff and the public with both the terminology and the concept. Cumulatively, these efforts have laid the foundation for an ongoing conversation about how strategic retreat and relocation may unfold in an effective and equitable manner on Nantucket.

A tailored approach

A forthcoming island-wide retreat and relocation planning effort led by the Town will build on the previous hazard mitigation and resilience planning efforts to identify priority retreat areas, evaluate potential receiving areas, and codify engagement best practices. Reflecting on the Town’s recent experiences will be critical to informing the development of an island-wide approach to managed retreat. This section details how conversations around town-led retreat and relocation are unfolding across the island in real-time, highlighting many nuances that other communities may face as they engage in these topics.

Nantucket’s formation due to glacial retreat and the resultant unique geology and topography has caused different coastal hazards to dominate in different areas of the island. Along the island’s eastern shore, steep bluffs like those running along Baxter Road are threatened by largely unpredictable episodic erosion. In areas of lower topography and gently sloping shorelines, like the Downtown area, tidal flooding and storm surge are the primary threats to the built environment. On the southern shore, erosion during storm events poses an increasing threat as storms become stronger and more frequent. Its island location, glacial geology and topography allows Nantucket to serve, in many ways, as a real-time case study. In the context of retreat and relocation planning, it provides the opportunity to document and learn from three very different experiences unfolding concurrently within one municipality.

Baxter Road

Along Nantucket’s Baxter Road, on top of the ‘Sconset bluffs, retreat is unfolding in real time (Figure 2). The ‘Sconset bluffs are subject to episodic erosion which can be infrequent and unpredictable. When erosion happens, large pieces of the bluff face can slump off, resulting in the loss of an unpredictable number of feet between a given structure and the bluff’s edge. Already, 27 homes along Baxter Road have been relocated as the bluff collapses and more have been demolished. Interestingly, when the land along Baxter Road was originally sub-divided, the alleged intent was for a single parcel to span both sides of the road, extending landward perpendicular to the bluff face, allowing property owners the opportunity to relocate their property landward if necessary (Brace, 2010).

Between 2013 and 2015, nearly 950 feet of geotubes (large, permeable sand filled tube shaped containers) were installed by the Siasconset Beach Preservation Fund with permission of the Town as an emergency measure to help protect the toe, or base, of the bluff and prevent additional erosion and loss of property along a particularly vulnerable stretch of Baxter Road. Since the geotubes were put in place, proponents have sought to expand the project resulting in an ongoing debate about how to best address erosion in this area in the long-term. In June of 2021, the Nantucket Conservation Commission (local regulatory authority over wetland and environmental permitting) voted to remove the geotubes, triggering a series of events that are still unfolding. As of July 2024, the geotubes have not been removed but the Town has taken steps to identify and begin to implement a practicable long-term plan for this high-risk area.

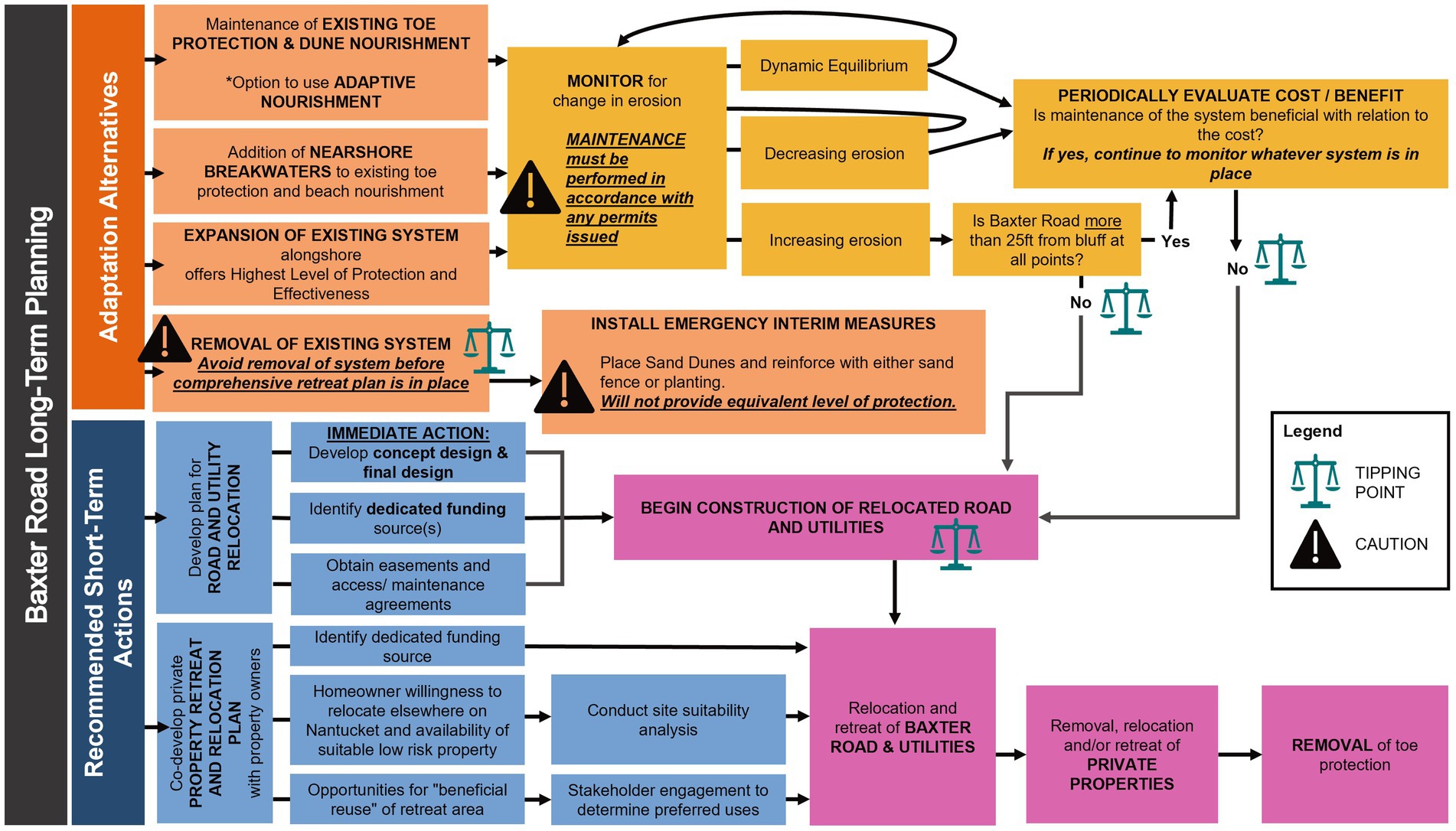

In October of 2021, in response to the Conservation Commission’s vote to remove the geotubes, the Town released the Baxter Road Long-Term Planning Summary of Findings Memorandum (Arcadis, 2021). This effort sought to compare technically feasible alternatives for providing bluff protection and develop a prioritized action plan to adapt the area over time based on the results of an alternatives analysis and significant stakeholder engagement. This memorandum served as a conversation starter and was the first time that Baxter Road was framed, publicly, as a retreat area. To support the alternatives analysis, adaptation pathways were developed (Figure 3). Adaptation pathways are sequences of actions implemented progressively and dependent on future dynamics. For Baxter Road, the adaptation pathways illustrate various alternatives, recommend short-term actions, and identify tipping points that may result in changes to the preferred long-term alternative. Prior to introducing the adaptation pathways, many stakeholders felt there was a binary choice to be made between removing the geotubes to allow for an immediate retreat and leaving the geotubes in place to continue providing protection. Stakeholder-informed development and subsequent socialization of this tool provided a common framework for how to think and talk about parallel planning efforts necessary in the short-term regardless of whether the geotubes are removed or not. Further, the tool proved to be effective in demonstrating that all potential pathways eventually lead to strategic retreat from the shoreline. This finding reinforced the importance of continued proactive planning for retreat and relocation along Baxter Road.

Figure 3. Adaptation pathways developed to support retreat and relocation planning along Baxter Road.

To support the eventual retreat of this area, engagement of stakeholders is ongoing as the Town develops an Alternative Access and Utility Relocation Plan for Continuity of Services for Baxter Road Residents (Town of Nantucket, n.d.). This plan will provide longer-term alternative access and utility services to residences along the northern, most vulnerable stretch of Baxter Road. As of July 2024, a shovel ready final design is expected in Summer 2025. The plan does not include the relocation of any private residences but does include demolition of Baxter Road and provision of landward alternative access.

Additionally, in January 2024, the Town released an Emergency Readiness Plan for Baxter Road from the Sankaty Head Lighthouse to Bayberry Sias Lane (Town of Nantucket, 2024). This plan establishes recovery procedures for when Baxter Road is no longer passable due to coastal erosion and highlights the Town’s responsibilities with respect to maintaining safety and provision of utility services if the roadway is unpassable.

The Town has not yet begun co-development of a private property retreat and relocation plan with property owners in the area. However, engagement has played a critical role in guiding the development of both the alternative access and emergency readiness plans. Given the small and largely seasonal population that may face the decision to retreat, it is anticipated that advancement of this planning is likely to happen in conjunction with the development of an island-wide retreat and relocation strategy.

Downtown

Nantucket’s Downtown neighborhood epitomizes the island’s unique historic character and is the economic, cultural, and historic hub of the island. Due to the relatively low topography of the area, Downtown is highly vulnerable to flooding (Figure 4). In 2022, a Town report documented a six-fold increase in the frequency of tidal flooding Downtown over the last 40 years (Larson, 2022). Between 1965 and 2023, NOAA tide gauge records indicate that Nantucket Harbor has experienced approximately 9.2 inches of sea level rise (NOAA, 2025). At-risk structures in the Downtown neighborhood include structures designated historically significant, cultural institutions, essential facilities and services (Steamboat Wharf, Hy-Line Cruises Terminal, the Downtown supermarket, and primary electrical substation for utility provider National Grid), in addition to dozens of businesses and services that support the local economy. According to the CRP, 325 structures and 3.5 miles of roadway Downtown are within priority action areas of extreme coastal risk per the island-wide risk framework. Assets within these areas are likely to be exposed to high-tide flooding or erosion as soon as 2030. Due to the extreme coastal risks faced in these areas today or within the next decade, the island-wide risk framework generally recommends a proactive reduction of density and minimization of large structural investments (Town of Nantucket, 2021).

However, despite the high level of flood risk Downtown, the Town has determined that, for now, structural protection is justified given the density of critical facilities and economic, social, cultural and historic assets. To preserve and enhance quality of life in Downtown, the Town is pursuing a series of structural approaches that reduce risk to the neighborhood’s core while prolonging the service of critical transportation facilities and corridors, as recommended in the CRP.

The Easy Street Flood Mitigation project and Washington Street Resilience Framework & Francis Street Beach Improvement Project, both currently underway, represent critical steps in building the long-term resilience of the historic Downtown and the entire island. The projects include the lowest lying roads in Downtown which play an essential role in providing access and egress to and from the island’s ferries and the many structures in the vicinity. Completion of these near-term projects will not eliminate flood risk to Downtown but will buy the Town time while determining the appropriate long-term adaptation pathway to transform Downtown in the face of increasing coastal risks, including significant groundwater rise, by the end of the century.

South shore—Surfside Wastewater Treatment Facility

Along Nantucket’s south shore, the Surfside Wastewater Treatment Facility (WWTF), built in the 1970s, is responsible for treating wastewater from the Town Sewer District which services about 60% of the island. When the facility was first built, it is estimated that there was up to 400 feet of beach between the wastewater treatment filter beds and the water. Over the past 2 years, there has been almost 150 feet of erosion. Notably, over the winter of 2023–2024, more than 50 feet of dunes eroded, imminently threatening the southernmost filter bed. While the bed was not operational, there were concerns that saltwater intrusion would impact operations of the other beds. In response, the Town filled in and closed the southernmost bed, allowing it to serve as a sacrificial sand source, buying some time before erosion progresses further inland and threatens facility operations (Treffeisen, 2024).

Now the Town is wrestling with how to protect the WWTF in the long-term. The CRP recommends the installation of reinforced dunes in front of the facility to provide additional protection while strategically relocating operative filter beds further back on the facility property. Other ideas discussed include installation of protective steel sheeting and relocation of the facility altogether. With uncertainty around the continued rate of erosion in this area, steep price tags (the CRP recommended project was estimated to cost between $33–38 million), the critical importance of this facility, and the dearth of low-risk land available for relocation, the decision is not likely to be straightforward. Communities and other critical assets, including the airport, along the south shore face similar challenges necessitating the assessment of trade-offs and acceptance of compromise in determining the appropriate long-term adaptation approach.

Relocation

As an island with inherently limited space, discussions of retreat on Nantucket are unfolding in parallel with discussions of relocation. Through Nantucket’s long-standing commitment to conservation, approximately 16,419 acres, or about 55% of the island’s total land area, are managed as conservation lands. These conservation lands are owned by various entities including the Nantucket Conservation Foundation, Massachusetts Audubon Society, Madaket Land Trust, ‘Sconset Trust, Nantucket Land Bank, Nantucket Land Council, The Nature Conservancy, the Trustees of Reservations, the Town, State and Federal governmental agencies, and other conservation groups (Town of Nantucket, 2019a). Though the limitations placed on conservation lands vary from property to property, new development is often not feasible for legal reasons or otherwise. Given the abundance of conservation land located in the relatively low coastal hazard risk areas mid-island, the trade-offs between conservation and opportunities for on-island relocation will need to be considered in the development of Nantucket’s strategic retreat and relocation plan. The identification of areas suitable for relocation will also need to consider the growing demand for year-round affordable housing on-island. In a recent affordable housing lottery for local non-profit Housing Nantucket’s latest project, 176 lottery applications were received for just six affordable apartments (Graziadei, 2024).

Discussion

Despite a noteworthy lack of guidance at State and Federal levels, since 2019, the Town has made great strides in laying the foundation for an ongoing, inclusive, and productive conversation around strategic retreat and relocation. As the Town prepares to take the next steps by developing an island-wide strategic retreat and relocation plan, there is an opportunity to document the many dimensions of this formidable challenge, as described in the previous sections, and to recognize lessons learned to date.

Through the Town’s recent experiences considering retreat in the diverse contexts of Baxter Road, Downtown, and the wastewater treatment facility, it has become clear that there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Retreat and relocation planning must be highly tailored and dynamic. However, there are lessons learned that resonate across these contexts and may be relevant to other communities engaged in conversations around strategic retreat.

• Capacity, support, time and funding are critical to sustain ongoing conversations on strategic retreat. Beginning in 2019, Nantucket gradually built capacity within Town government by demonstrating the need for a coastal resilience coordinator position and developing the public awareness necessary to support establishment of the position. However, the lack of affordable housing on island threatens the Town’s ability to maintain and expand staff capacity to lead proactive resilience planning efforts. Support for resilience work broadly, both within Town government and among the public, has been garnered over time through dedicated engagement and establishment of the CRAC as an entity devoted to implementation. Developing a steady funding source for proactive planning is a perennial challenge. On Nantucket, increasing public awareness and demand for action to address coastal hazards has served as a motivating force in the acquisition of funding through municipal, grant, and private sources.

• Engagement is key in all resilience planning but especially when planning for retreat and relocation (Mach and Siders, 2021; Kraan et al., 2021). The work on Baxter Road has demonstrated the necessity of approaching engagement as an enduring conversation, communicating early and often, and the reality of consensus-building as an ongoing process. Across various efforts, the Town has learned that communication, both internally and to the public, can be misinterpreted, highlighting the necessity of checking in consistently to ensure the intent of communication is heard. Education through various engagements has also helped foster shared understanding of climate change, coastal hazards and resilience, and the use of shared terminology across the island. Though engagement inevitably leads to pushback and differing ideas of success, Nantucket has leveraged this as an opportunity to make a better plan moving forward rather than viewing it as a setback or an excuse not to proceed.

• One of the major challenges in discussing retreat and relocation is the lack of certainty around what the future looks like. Nantucket’s experiences have demonstrated repeatedly the importance of transparency and expectation setting. To help set expectations, Nantucket has found success in communicating things that are known or can be defined. In the case of Baxter Road, the Town worked with stakeholders to define what failure and success looked like (while acknowledging the necessity of compromise), define the process (recognizing that it may change), and identify key decision points and decisionmakers.

As the Town embarks on the development of a strategic retreat and relocation plan, these lessons learned will be incorporated into the process to support a productive community conversation as critical decisions are made about how retreat and relocation can help realize a resilient island home for all Nantucketers, today and in the future.

Constraints

This community case study is based on the experience of one municipality. Their experience with retreat and relocation may not be representative of other municipalities. Further, Nantucket’s approach to retreat and relocation is ever evolving and, as such, may change following publication.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. LH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding for development of this article was provided by the Town of Nantucket Natural Resources Department and Arcadis, U.S. Inc.

Acknowledgments

Thank you first and foremost to the Nantucket community and Town staff who drive this important work forward. Thank you also to Arcadis colleagues Kathryn Edwards, Trevor Johnson and Jennifer Kelly Lachmayr for their support in development of this article.

Conflict of interest

DM was employed by Arcadis, U.S., Inc., a consultancy hired by the Town of Nantucket to support several of the initiatives mentioned in this article.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, Jen Shalley. (2023). “Nantucket Real Estate.” A comprehensive real estate analysis - 2023 year in review. Available online at: https://fishernantucket.com/2023-nantucket-real-estate-year-in-review/ [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Arcadis. (2021). Baxter Road Long-Term Planning Summary of Findings Memorandum. Available online at: https://www.nantucket-ma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/40516/Baxter-Road-Long-Term-Planning-Final-Memo-October-20-2021-PDF [Accessed May 15, 2025].

Brace, Peter B.. (2010). “Paradise lost, Baxter road owner moving house to Monomoy.” WickedLocal. April 21. Available online at: https://www.wickedlocal.com/story/archive/2010/04/21/paradise-lost-baxter-road-owner/987639007/ [Accessed July 31, 2024].

Graziadei, Jason. (2024). “Nantucket current.” Housing Nantucket Sees Huge Demand During Affordable Apartment Lottery. Available online at: https://nantucketcurrent.com/news/housing-nantucket-sees-huge-demand-during-affordable-apartment-lottery [Accessed July 31, 2024].

Harrison, Michael R. (n.d.). When Did Nantucketers Begin Whaling? Available online at: https://nha.org/research/nantucket-history/history-topics/when-did-nantucketers-begin-whaling/ [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Kraan, C. M., Hino, M., Niemann, J., Siders, A. R., and Mach, K. J. (2021). Promoting equity in retreat through voluntary property buyout programs. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 11, 481–492. doi: 10.1007/s13412-021-00688-z

Larson, Charles D. (2022). Easy street: An update on high-tide flooding. February 4. Available online at: https://www.nantucket-ma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/41289/Easy-Street-An-Update-on-High-Tide-Flooding---February-4-2020-PDF [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Lindner, L. (2023). In the Shadows: An update on Nantucket's housing crisis. N Magazine. July 31. Available online at: https://www.n-magazine.com/in-the-shadows [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Lindner, L. (2024). Hunger is no game: A deeper look into Nantucket's food insecurity. N magazine. April 24. Available online at: https://www.n-magazine.com/food-insecurity-nantucket [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Mach, K. J., and Siders, A. R. (2021). Reframing strategic, managed retreat for transformative climate adaptation. Science 372, 1294–1299. doi: 10.1126/science.abh1894

Nantucket Historical Association. (n.d.). Native Peoples. Available online at: https://nha.org/research/nantucket-history/history-topic/native-peoples/ [Accessed July 1, 2024].

NOAA. (2025). Tides and Current: Relative Sea Level Trend 8449130 Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. Available online at: https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/sltrends_station.shtml?id=8449130 [Accessed September 13, 2024].

Stackpole, Matthew, and Harrison, Michael R. (n.d.). Why did Nantucketeers stop whaling? Available online at: https://nha.org/research/nantucket-history/history-topics/why-did-nantucketers-stop-whaling/ [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Town of Nantucket. (n.d.). FAQs. Available online at: https://www.nantucket-ma.gov/Faq.aspx?QID=289 [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Town of Nantucket. (2014). Coastal Management Plan. Available online at: https://nantucket-ma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/6333/Nantucket-Coastal-Management-Plan---2014 [Accessed May 15, 2025].

Town of Nantucket. (2019a). Community Resilience Building Workshop Summary of Findings - Final Report. Available online at: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2019/07/11/Nantucket%20Report.pdf [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Town of Nantucket. (2019b). Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan. Available online at: https://www.nantucket-ma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/24719/Town-of-Nantucket-2019-Hazard-Mitigation-Plan [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Town of Nantucket. (2020). Coastal Risk Assessment and Resiliency Strategies Report. Available online at: https://www.nantucket-ma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/35045/Coastal-Risk-Assessment-and-Resiliency-Strategies-Report-January-2020-PDF [Accessed May 15, 2025].

Town of Nantucket. (2021). Nantucket Coastal Resilience Plan - Final Report. Available online at: https://www.nantucket-ma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/40278/Nantucket-Coastal-Resilience-Plan-PDF [Accessed July 1, 2024].

Town of Nantucket. (2024). Emergency Readiness Plan - Baxter Road (Sankaty Head Lighthouse to Bayberry Sias Lane). Available online at: https://www.nantucket-ma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/48240/Emergency-Readiness-Plan-for-Baxter-Road---January-11-2024-PDF [Accessed May 15, 2025].

Town of Nantucket. (n.d.). Baxter Road Alternative Access. Available online at: https://www.nantucket-ma.gov/2654/Baxter-Road-Alternative-Access [Accessed May 15, 2025].

Treffeisen, Beth. (2024). "Beach erosion threatens sewage-treatment plant on Nantucket." Boston Globe. February 22. Available online at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/02/22/science/nantucket-sewer-treatment-plant-erosion-climate-change/#:~:text=So%20drastic%20that%20the%20treatment,left%20from%20a%20nearby%20development [[Accessed July 31, 2024].

University of Massachusetts Amherst Donahue Institute of Economic Public Policy and Research. (2023). An Evaluation of Current Conditions in the Nantucket Housing and Short-Term Rentals Market. Nantucket Current. April. Available online at: https://nantucket-current.nyc3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/assets/An-Evaluation-of-Nantucket-Housing-and-STRs.pdf [Accessed July 1, 2024].

US Census Bureau. (2022). 2022 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Available online at: data.census.gov [Accessed July 1, 2024].

US Census Bureau. (2020a). American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables. Available online at: data.census.gov [Accessed July 1, 2024].

US Census Bureau. (2020b). 2020 Decennial Census. Available online at: data.census.gov [Accessed July 1, 2024].

USGS. (n.d.). Geologic History of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Available online at: https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/capecod/glacial.html [Accessed September 13, 2024].

Keywords: retreat, Nantucket, resilience, climate change, coastal hazards

Citation: McKaye DJ, Murphy V and Hill L (2025) Retreat in real time—Nantucket’s balancing act along a changing coast. Front. Clim. 7:1510802. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1510802

Edited by:

Charles Krishna Huyck, ImageCat (United States), United StatesReviewed by:

David Casagrande, Lehigh University, United StatesChristopher Jones, CPJA, United States

Copyright © 2025 McKaye, Murphy and Hill. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Devon J. McKaye, ZGV2b24ubWNrYXllQGFyY2FkaXMuY29t

Devon J. McKaye

Devon J. McKaye Vincent Murphy2

Vincent Murphy2