- 1Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Department of Geography, Munich, Germany

- 2University of the Philippines Diliman, School of Urban and Regional Planning, Quezon City, Philippines

- 3Climate KIC, Amsterdam, Netherlands

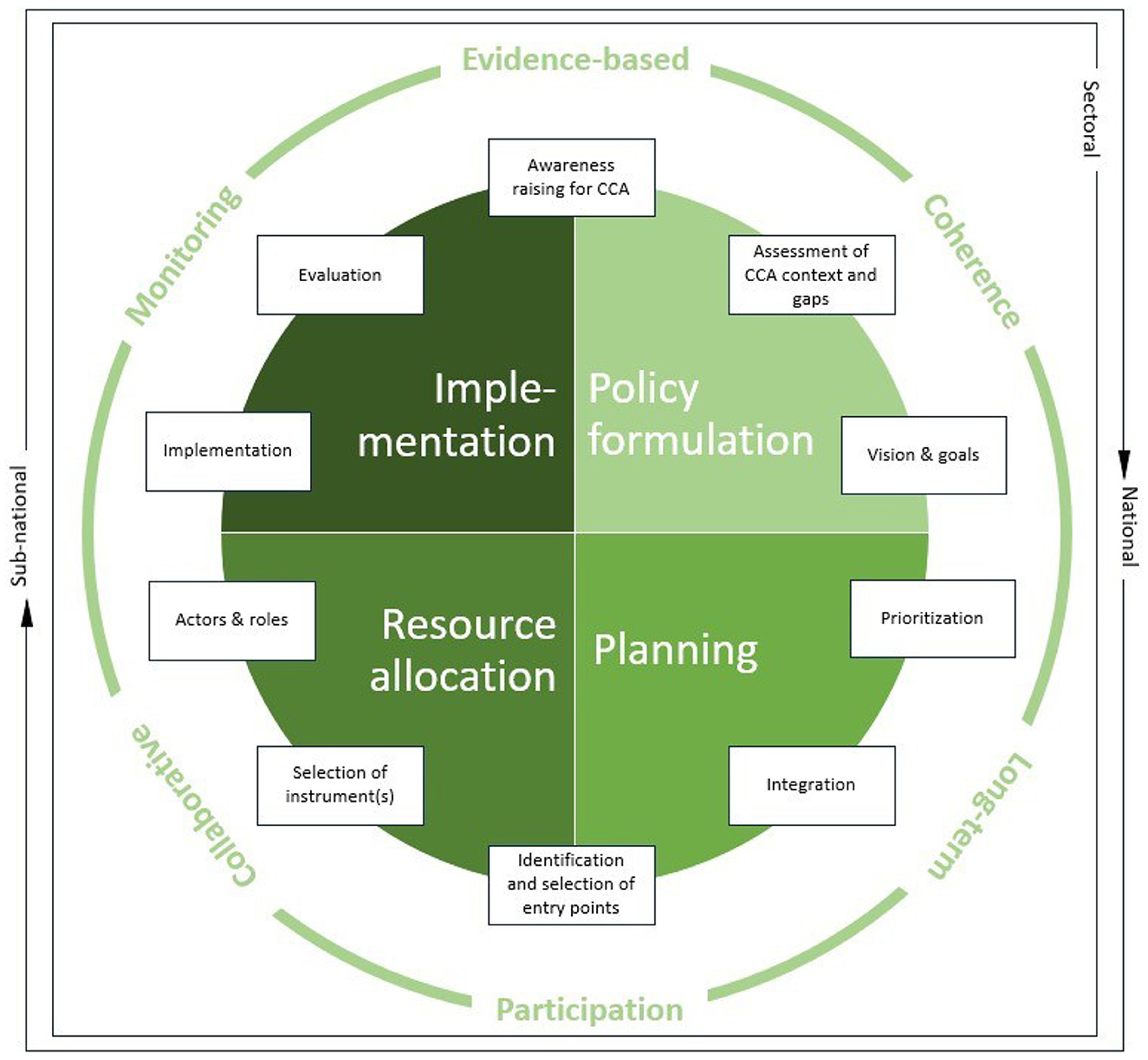

Despite the growing body of scientific literature on mainstreaming climate change adaptation (CCA) into urban planning and numerous implementation guidelines, adaptation remains insufficiently integrated across sectors and scales in urban development, particularly in cities in the Global South. Persisting challenges are conceptual ambiguity, lengthy and overwhelming manuals and guidelines not tailored to planners' needs, and the limited transferability of case study findings especially for cities in the Global South. This study addresses these gaps by developing a pragmatic mainstreaming protocol tailored for urban policymakers and planners to facilitate the mainstreaming of CCA into urban development planning. It provides information and guidance regarding four key elements of mainstreaming: policy formulation, planning, resource allocation and implementation. The protocol was piloted in Metro Manila, the Philippines, focusing on enhancing the integration of upgrading and resettlement as adaptation strategies in urban development planning. They contribute to the ongoing debate on whether mainstreaming of adaptation into general urban planning is more effective than dedicated adaptation policies. This work highlights the need for coherent policies, clear roles, and cross-sectoral collaboration to ensure resilient urban development in vulnerable regions.

1 Introduction

The imperative to mainstream climate change adaptation (CCA) across scales into sectoral policies, plans, and legislation has received growing attention with the acknowledgment of climate change as a cross-cutting issue (Adelle and Russel, 2013). Already today, the impacts of climate change affect every facet of urban planning, from transportation networks to housing infrastructure and land use decisions, demanding systematic integration of CCA into policy design and implementation. Failing to adequately consider both current and projected climate change impacts in urban planning severely inhibits sustainable development trajectories. Yet, despite this recognition, CCA remains siloed in many contexts, treated as a standalone strategy rather than a cross-cutting priority, resulting in considerable challenges for sustainable development. For example, while future flood risk exposure is often addressed in dedicated climate action plans, it is frequently not included in overall land-use planning. As a result, there is persistent expansion of urban settlements into floodplains, a trend quantified globally through satellite observations: from 2000 to 2015, the proportion of the global population exposed to inundation increased by 20–24%, with 58 to 86 million new residents settling in flood-prone areas, predominantly in rapidly urbanizing Asian cities (Tellman et al., 2021). Such patterns underscore a critical disconnect between adaptation planning and urban development, where short-term growth priorities often eclipse long-term resilience. Mainstreaming adaptation in urban planning provides a means for cities to address this disconnect and reconcile development agendas with climate resilience (García Sánchez, 2022).

Despite significant advances in both conceptual understanding and the development of practical guidelines, evidence suggests that adaptation mainstreaming remains uncommon in practice (Mogelgaard et al., 2018), with adaptation rarely addressed comprehensively across sectors and scales, particularly in urban planning (Reckien et al., 2019). This gap is particularly acute in rapidly growing cities of the Global South, which are among the most exposed and vulnerable to climate change (Dodman et al., 2022). The urgency to effectively integrate CCA considerations into development planning is underscored by the increasing risk profiles of these cities. Yet, there is rich evidence that many at-risk cities continue to pursue development trajectories that are insufficiently climate-sensitive (Wannewitz et al., 2024), for example, Jakarta's controversial urban development and coastal protection project (Colven, 2017; Garschagen et al., 2018; Wade, 2019), and Ho Chi Minh City's continued expansion into future flood zones (Storch and Downes, 2011; Duy et al., 2018). Despite projections already established earlier this century that a 100 cm rise in sea level would inundate nearly 60% of Ho Chi Minh City's built-up area under the existing urban expansion trajectories, the city has continued to prioritize industrial and residential growth in low-lying and flood-prone zones, such as the south and northeast of the city (Storch and Downes, 2011; Scheiber et al., 2024; Leitold and Diez, 2019). Analysis hence revealed that the majority of new exposure to flooding is attributable to planned urban expansion into flood-prone areas rather than sea level rise (Storch and Downes, 2011), highlighting that adaptation considerations have not been effectively mainstreamed into general spatial planning. These findings emphasize the need for adaptation mainstreaming, following an approach that embeds adaptation as a foundational consideration across all planning stages and scales, rather than trying to align policy goals after the fact.

A review of conceptual and empirical literature reveals five key gaps hindering effective mainstreaming in practice. First, while scientific research has produced a wide range of conceptual frameworks and definitions of mainstreaming, the absence of harmonization has led to ambiguity and conflations around terms and concepts (Adams et al., 2023). Achieving clarity in definitions and frameworks is essential for the operationalization and evaluation of mainstreaming processes (Runhaar et al., 2018). Second, although enablers of and barriers to mainstreaming are well-documented (e.g., Runhaar et al., 2018; New et al., 2022), significantly less is known on how to create or overcome them (Lyles et al., 2018). Third, practitioner-oriented manuals and guidelines from non-academic sources are often lengthy, overly complex, and not well-aligned with the needs of urban planners (see e.g., Dalal-Clayton and Bass, 2009; Taylor et al., 2018). Fourth, empirical research largely focuses on case studies in the Global North (Rogers et al., 2023), raising questions about the transferability of insights to high-risk cities in the Global South, where adaptation capacity is often weakest. Finally, raising criticism on mainstreaming can risk creating contestation about its value for advancing adaptation.

These knowledge gaps have serious implications for the mainstreaming of adaptation, particularly for political decision-makers and urban planners in at-risk cities in the Global South, who must navigate a landscape of competing definitions, a myriad of conceptual frameworks, and implementation strategies which are either rather broad or overwhelmingly detailed.

This study addresses these gaps by developing a pragmatic protocol to support urban policymakers and planners, designed to facilitate the mainstreaming of CCA into urban planning and its implementation. To do so, we built on three central methods: First, literature was gathered using key words and snowballing and reviewed to assess the current state of research and practical guidance on mainstreaming in the field of CCA. This review was used to identify the keys gaps and inform the protocol's development. We then validated the protocol through a two-tiered approach, (1) by collecting empirical data through an online survey of Filipino policymakers and urban planners and then (2) combining this with real-world testing in Metro Manila, Philippines, as part of the Linking Disaster Risk Governance and Land-Use Planning (LIRLAP) project. This application focused on enhancing the integration of upgrading and resettlement as adaptation strategies within urban development planning and implementation through mainstreaming.

Ultimately, this study seeks to improve the integration of CCA in urban development planning processes and to help close the adaptation mainstreaming implementation gap (Mogelgaard et al., 2018; Runhaar et al., 2018; Reckien et al., 2019; Wamsler and Osberg, 2022; Rogers et al., 2023), thereby supporting the creation of coherent, climate-sensitive urban futures.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the state of knowledge on policy mainstreaming and its implementation in the field of CCA without claiming comprehensiveness. Section 3 presents the developed LIRLAP protocol for mainstreaming and elaborates on its applicability from a user-centered perspective. Section 4 discusses the protocol in the context of current debates around mainstreaming and draws implications for the case study of Metro Manila and beyond. The conclusion emphasizes the contribution of the developed protocol to ongoing mainstreaming debates and its potential to help foster climate-resilient development.

2 Mainstreaming climate change adaptation in urban development plans—State of the art and gaps

The scientific literature on mainstreaming has increased significantly since 2010. Focusing on literature that concentrates on environmental and climate adaptation mainstreaming, including disaster risk governance and risk management, we find that it has largely evolved in four distinct directions. Firstly, from a conceptual standpoint, many scientific publications focus on categorizing and understanding the diverse types of mainstreaming. Secondly, the literature identifies barriers to and enablers of mainstreaming. Thirdly, the literature includes numerous case studies that present empirical evidence for mainstreaming processes from a variety of geographic contexts and scales. Lastly, an emergent literature stream questions whether mainstreaming is the most effective way forward to better consider CCA in urban development. In the following, we provide a concise overview of these different streams of mainstreaming literature, which collectively underpin the theoretical foundation of our scientifically informed yet practically applicable mainstreaming protocol.

2.1 First stream: types of mainstreaming and instruments

The literature on mainstreaming concepts and frameworks adopts a wide range of perspectives when conceptualizing and categorizing mainstreaming (see Supplementary Table 1—Types of mainstreaming and instruments). Many meta-studies already provide rich overviews of this research field (e.g., Gupta, 2010; Adams et al., 2023; Bleby and Foerster, 2023).

From a process perspective, mainstreaming is often categorized into vertical and horizontal mainstreaming (Nunan et al., 2012; Rauken et al., 2015; Wamsler and Pauleit, 2016), each with distinct yet complementary strategies. Horizontal mainstreaming includes add-on mainstreaming, programmatic mainstreaming, and inter- and intra-organizational mainstreaming, while vertical mainstreaming is linked to regulatory, managerial, and directed approaches (Wamsler and Pauleit, 2016). Other scholars have proposed other distinctions, such as normative, organizational, or procedural mainstreaming (Persson, 2004), or have differentiated between substantive, methodological, procedural, institutional, and policy mainstreaming (Eggenberger and Partidário, 2000).

Outcome-based categorizations further enrich this landscape. Mainstreaming be can described as either integrationist, focusing on incremental alignment with existing structures, or transformative, which seeks to foster reorganization and redesign leading to changes in rules, norms, and institutional settings, described as “mature” mainstreaming (Gupta, 2010; Bleby and Foerster, 2023). Mainstreaming is also viewed as one of several policy integration approaches, alongside policy harmonization, coordination, and institutionalization (Howlett and Saguin, 2018). This sampling of the diverse categorizations highlights the multidimensionality of the mainstreaming conceptualizations and underscores the complexity of mainstreaming as both a policy process and a governance challenge.

This literature also identifies a range of typologies of instruments and strategies for operationalizing mainstreaming. Besides the process strategies outlined above (Wamsler and Pauleit, 2016; Adams et al., 2024) distinguish between disruptive mechanisms, such as experimentation, scaling, translation, and anchoring mechanisms, including integration and learning. Bleby and Foerster (2023) categorize mainstreaming instruments into regulatory, institutional, and capacity mechanisms. Similarly, the IPCC structures its chapter on enabling conditions for catalyzing adaptation and mainstreaming risk management along three categories, namely governance, including legal, policy, and regulatory instruments, knowledge and capacities, and finance (New et al., 2022).

In summary, this stream of literature provides a wide range of conceptual perspectives on the various types and instruments of mainstreaming. It captures the conceptual richness and practical diversity of approaches yet also reveals ongoing challenges in harmonizing terminology and frameworks. The persistent coexistence of overlapping terms in the conceptualization of mainstreaming, including related terms and analytical tools, has led to conceptual and theoretical ambiguity, for instance, with mainstreaming often used interchangeably with the concept of policy integration (Tosun and Lang, 2017; Adams et al., 2023). Furthermore, many conceptualizations remain quite broad and difficult to operationalize (Cuevas, 2016b; Howlett and Saguin, 2018). As such, while this literature lays the foundation for advancing mainstreaming theory and practice, it also underscores the need for greater clarity and practical guidance to support effective implementation.

2.2 Second stream: barriers and enablers

Empirical studies on mainstreaming have identified several key barriers and enablers. Among the most frequently cited barriers (for a full list see Supplementary Table 2—Barriers to mainstreaming) are: (1) ineffective or insufficient communication, coordination, and collaboration between stakeholders across hierarchies and sectors (Macchi and Ricci, 2016; Lyles et al., 2018; Boezeman and De Vries, 2019; Ahenkan et al., 2021; New et al., 2022), (2) a lack of accessible data, e.g., regarding the spatial distribution, frequency, and intensity of climate impacts in cities (Lyles et al., 2018; Ahenkan et al., 2021; Bleby and Foerster, 2023), (3) limited technical, analytical and organizational capacity (Dalal-Clayton and Bass, 2009; Howlett and Saguin, 2018; Pieterse et al., 2021; García Sánchez, 2022; Bleby and Foerster, 2023), (4) inadequate financial resources, time, and personnel (Cuevas, 2016b; Boezeman and De Vries, 2019), and (5) lacking incentives, insufficient political support, and weak leadership diminish the momentum required to sustain mainstreaming efforts (Macchi and Ricci, 2016; Chakrabarti, 2017; Lyles et al., 2018; Runhaar et al., 2018; Boezeman and De Vries, 2019; Pieterse et al., 2021; García Sánchez, 2022).

Based on the synthesis of various mainstreaming studies, the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (New et al., 2022) presents a rich overview of enabling conditions categorized under governance, knowledge and capacity, and finance. To just give a few examples, it is argued that climate legislation such as laws, regulations, and standards including climate considerations can facilitate mainstreaming adaptation. Similarly, policies, plans, and strategies dedicated to climate issues are important levers for mainstreaming. Beyond formal and legally binding enabling factors, the chapter highlights the role of voluntary and non-legally required actions such as the consideration of social and environmental factors in decision-making in different sectors (New et al., 2022). The consideration and integration of different knowledge systems, the co-production of knowledge as well as stakeholders' capacities and motivations are described as essential for facilitating mainstreaming. Lastly, the availability of data and sufficient financial resources represent important enabling conditions (New et al., 2022).

This stream of literature presents valuable insights into barriers and enabling conditions for mainstreaming. However, from a practical point of view, it often falls short in providing actionable guidance on how to effectively overcome barriers and create the described enabling conditions (Lyles et al., 2018).

Beyond this, non-academic actors such as NGOs and international organizations have developed toolkits particularly focusing on practitioners to guide mainstreaming efforts (e.g., Dalal-Clayton and Bass, 2009; Olhoff and Schaer, 2010; Chakrabarti, 2017; Taylor et al., 2018). These resources aim to raise awareness and provide operational guidance for decision-makers and urban planners in integrating climate change concerns in all sectors involved in urban development as well as across scales and hierarchies. Their contributions to the field of mainstreaming research and implementation are not yet fully acknowledged in the scientific literature, nor is academic knowledge adequately feeding into these practical manuals. At the same time, these manuals are oftentimes overly detailed and do not consider planning processes and the needs of urban planners, limiting their practical use for them and other stakeholders.

2.3 Third stream: case studies

This stream of literature provides a vast variety of examples for mainstreaming processes and outcomes in different geographical locations and scales, including meta-analyses with regional (Friend et al., 2014; Runhaar et al., 2018; Reckien et al., 2019) and global (Runhaar et al., 2018; Dellmuth and Gustafsson, 2021; Rogers et al., 2023) scope. Comprehensively summarizing this field of research is beyond the scope of this study, however, it can be stated that case studies differ in the topics and approach for mainstreaming, the scale on which they focus, and the geographical location. Topics for mainstreaming reach from specific areas such as mainstreaming nature-based solutions to broader perspectives like mainstreaming environmental considerations (Nunan et al., 2012; Adelle and Russel, 2013; Adams et al., 2023; Rogers et al., 2023; Sen and Dhote, 2023) or very generally mainstreaming adaptation into, for instance, urban development planning (Farrell, 2010; Uittenbroek et al., 2013; Macchi and Ricci, 2016; Uittenbroek, 2016; Atanga et al., 2017; Koch, 2018; Newman, 2020; Gabriel et al., 2021; Burns et al., 2022; ten Brinke et al., 2022), rural municipal planning (Pieterse et al., 2021; Mugari and Nethengwe, 2022), the housing sector (Boezeman and De Vries, 2019; ten Brinke et al., 2022), or land-use planning (Khailani and Perera, 2013; Cuevas, 2016a,b; Adams et al., 2023). Geographically, there is a concentration of case studies from high-income countries, particularly in Europe, Australia, and the United States, with a strong emphasis on urban contexts (Wellstead and Stedman, 2015; Widmer, 2018; Metzger et al., 2021; Burns et al., 2022; Hanna et al., 2022; Rogers et al., 2023). Their transferability to other regions and contexts such as Asia and Latin America where case studies are scarce, is questionable. We found only a few case studies from Asia (Saito, 2013) such as biodiversity mainstreaming in Singapore and Mumbai (Sen and Dhote, 2023), or land-use planning in the Philippines (Cuevas, 2016b).

In summary (see Supplementary Table 3—Mainstreaming case studies), while there is a wealth of empirical research on mainstreaming, it is heavily skewed toward cities in the Global North. This creates a significant research gap, especially given the greater challenges of governing urban adaptation in highly vulnerable cities in the Global South, where urbanization, climate impacts, and limited capacities compound the difficulty of mainstreaming adaptation (Garschagen and Romero-Lankao, 2015).

2.4 Fourth stream: mainstreaming vs. dedicated policies

Recently, critiques of mainstreaming have grown, highlighting its risks and questioning its effectiveness. Some argue that mainstreaming might reinforce established logics where innovation is required and that it can depoliticize adaptation into technocratic decisions (Schipper et al., 2022) or blur policy scope (Reckien et al., 2019). Candel (2021) questions whether mainstreaming is always the best way to address complex challenges as there are good reasons for having specialized entities being responsible for specific topics. Furthermore, he argues that mainstreaming can take away healthy competition between topics and reduce—sometimes useful—redundancies (Candel, 2021). Given limited evidence for both the success and the disadvantages of mainstreaming, particularly from different regional contexts and scales, its effectiveness remains contested.

3 Mainstreaming definition and protocol development

3.1 Mainstreaming definition

Building on the mainstreaming literature, this study understands mainstreaming as a dynamic, multi-level, and multi-stakeholder process that aims at the informed integration of a topic of interest into all areas of policymaking (Ayers et al., 2014). It brings marginal topics of cross-cutting character to the center of political attention (Gupta, 2010; Adams et al., 2023). Mainstreaming is one instrument to pursue policy integration (Howlett and Saguin, 2018) and is a process of re-designing and re-organizing existing policies, institutions, and structures to achieve a more integrated and improved “normal” (Bleby and Foerster, 2023), i.e., to transform a system toward a new normal without radical changes (Adams et al., 2024). Mainstreaming CCA, therefore, can be considered a long-term policy process that pursues the informed integration of climate change risks into all existing policies, institutional frameworks, and decision-making structures. The process of mainstreaming thus requires a high level of political capacity due to negotiations needed to reach a consensus on common goals, instruments, and responsibilities (Howlett and Saguin, 2018).

Given this complexity, many existing conceptual frameworks suggest breaking down the process into distinct phases and sub-processes to reduce complexity and allow for coherent planning. Our suggested protocol adopts the same perspective and roughly follows the structure of well-established mainstreaming frameworks (e.g., Olhoff and Schaer, 2010; Taylor et al., 2018), but with one important difference: unlike many other frameworks, manuals, and guidelines for mainstreaming, key elements of the process are based on scientific findings. Most importantly, we operationalized them through concrete questions and to-dos in a checklist (see Supplementary Table 4—Checklist for mainstreaming protocol) aiming to provide a pragmatic and user-friendly planning tool, as well as implementation guidance, to decision-makers and urban planners.

3.2 Protocol development

In the following, we briefly describe the mainstreaming protocol (Figure 1) with selected examples from the checklist. The mainstreaming process is embedded in overarching conditions that we argue to be important throughout planning and implementation. The envisioned changes to be mainstreamed must therefore be based on context-specific evidence to ensure that they are locally-grounded and have been proven successful solutions (Adams et al., 2024). Ensuring policy coherence across sectors and scales should be central throughout the process to avoid redundancies and gaps (Aleksandrova, 2020). Furthermore, the envisioned changes need to be planned for the long-term, using participatory and collaborative approaches to increase acceptance and sustainability (Aleksandrova, 2020; Adams et al., 2024). Finally, monitoring the effects of mainstreaming and developing sound evaluation systems to assess both success and failure are key to the effectiveness of mainstreaming (Ahenkan et al., 2021).

Based on a review of mainstreaming literature and existing mainstreaming frameworks, we developed the following protocol for mainstreaming with its individual components and the supplementary checklist (Supplementary Table 4—Checklist for mainstreaming protocol). The protocol consists of four distinct phases: policy formulation, planning, resource allocation, and implementation. The questions included in the checklist were developed through a series of workshops taking place over the duration of the LIRLAP project, in addition to information ascertained during semi-structured interviews conducted between October 2023 and April 2024.

3.2.1 Policy formulation: awareness raising, assessment of context and gaps, vision and goals

When a problem such as the comprehensive integration of adaptation in urban planning is identified, the first step is to raise awareness among stakeholders (Nassef, 2012; Ahenkan et al., 2021; New et al., 2022). This approach ensures that all stakeholders possess a comprehensive understanding of the issue and their respective roles in addressing it. The process of awareness-raising has been demonstrated to engender collective commitment and to emphasize the relevance of adaptation for various sectors, ensuring that all key aspects are given due consideration in the subsequent steps (Nassef, 2012; Ahenkan et al., 2021; New et al., 2022).

The next task is to comprehensively assess the current context (Aleksandrova, 2020), encompassing all its dimensions (social, political, environmental, economic, cultural). This involves identifying both formal (e.g., policies, regulations) and informal (e.g., norms, practices) systems, pinpointing any gaps, redundancies, or mismatches. The goal is to develop a clear understanding of the current situation to have a sound knowledge basis regarding all involved subsystems for the mainstreaming process (Candel, 2021). In the checklist, this is covered through the following questions: “What are existing formal (institutions, policies, legislation, regulation, financing, etc.) and informal (traditions, norms, practices) settings of the context the mainstreaming should improve?” And “What are inter-linkages and where are problematic gaps, redundancies, or mismatches?” Besides these, users are provided with concrete to-dos such as “Develop an evidence-based overview of the context (environmental, social, economic, cultural; institutional, legal, political; norms, traditions, practices)” and “Have an overview of existing gaps, redundancies and/or mismatches.”

The context assessment and identified gaps serve as input to discuss the objective of the mainstreaming process with all relevant stakeholders (Bleby and Foerster, 2023). In a joint effort, stakeholders should set an overarching clear goal (Candel, 2021), determine a core team to work out the mainstreaming process (Taylor et al., 2018), and develop a cooperation structure for those not constantly involved (Linke et al., 2022). Together, the joint goal, which is aligned to the vision, the core team, and the cooperation structure help to align stakeholders and ensure communication, cooperation, and collaboration between stakeholders, preempting many mainstreaming barriers.

3.2.2 Planning: prioritization, integration, entry points

The second phase of mainstreaming, “Planning,” begins once the context is assessed, gaps are identified, stakeholders are involved, and a clear goal is set. This phase focuses on prioritizing key gaps, deciding how to address them, and identifying entry points for integration.

Typically, more than one gap or issue will emerge from the context assessment, but not all can be tackled through the mainstreaming process. In the case of mainstreaming climate adaptation into urban planning, various risks could be addressed. However, since addressing all issues at once is often impractical, prioritization is key (Taylor et al., 2018). Risks, issues, and gaps should be ranked considering factors such as urgency and stakeholder needs but also potential co-benefits. Most importantly, all involved stakeholders need to agree on a shared prioritization of issues that need to be most urgently addressed through mainstreaming. For this, evaluation criteria such as urgency, reach, and co-benefits need to be determined and discussed against each other with all involved stakeholders to negotiate the final choices.

Once the most critical gap is selected, the next decision is whether it should be integrated across sectors and scales or addressed through a dedicated plan, policy, or institutional change (Candel, 2021). For example, if a specific aspect of urban planning requires focused regulation, it might be best handled through a separate policy. On the other hand, if integration into existing frameworks is feasible, this would ensure a more coordinated, cross-sectoral response. The decision will depend on the potential for integration and the specific nature of the gap. In the checklist, this is addressed through the following questions: “What is the potential for integrating the mainstreaming topic across sectors/organizational structures/scales?”, “Is there a need for establishing a dedicated plan/policy/structure/institution for the topic?” and “Can an existing M&E framework be used for M&E or is it necessary to develop a new one?”. The concrete to-dos linked to it are “Decide about whether to integrate or develop a new, separate plan/policy/structure.” And “Identify a suitable M&E structure, including indicators, timeframes, and responsibilities.”

If mainstreaming is the preferred approach, the next step is identifying entry points (Dalal-Clayton and Bass, 2009; Nassef, 2012)—i.e., points to introduce change to the existing system; in other words, they represent windows of opportunity within existing systems where changes can be introduced. These entry points could be administrative, legislative, or institutional, depending on the context. For instance, in the example of urban planning, a change to an existing building code (legislative change) could ensure that new constructions are more climate resilient. Similarly, changing the mandates of existing authorities could introduce change (institutional). Which entry points are most promising for introducing change is highly context specific. Therefore, the context analysis from the beginning plays an important role, as well as the engagement of various stakeholders to assess which entry points are most promising for introducing change in an effective and sustainable way.

3.2.3 Resource allocation: instruments, actors, institutions and their roles and responsibilities

The third phase of mainstreaming begins once promising entry points for integration have been identified. This phase focuses on selecting and allocating the appropriate resources—both instruments and actors—to bring the planned changes into effect.

For this, it first needs to be determined which instruments should be employed to bring the envisioned changes to the ground. Instruments can be distinguished into several categories: legal, policy and regulatory instruments, financing, knowledge and capacity building, and catalyzing conditions (New et al., 2022). The IPCC calls them enabling conditions for mainstreaming CCA into development planning (New et al., 2022). The wide range of different instruments that fall into the listed categories are concrete tools that will drive the mainstreaming process and bring changes to the ground. Their design, application and effect are very context-specific and may evolve very differently in different settings, structures, and scales. Therefore, the exchange of what has worked, and evidence-based knowledge is essential for the selection of instruments. Despite being context-specific, many empirical studies have proven legislative instruments and finances to be a valuable tool to realize change (e.g., García Sánchez et al., 2018). Concrete to-dos for the planning phase include for example “Identify multiple instruments (if possible) from different categories,” “Link them to the entry points,” “Develop pilots/experiments to test or simulate their feasibility (implementation, financing, acceptance).” And “Discuss and adjust the selected instruments with all relevant stakeholders.”

Once instruments for the identified entry points are determined, their implementation largely depends on clearly defined roles and responsibilities of involved actors. Therefore, a joint decision on who takes on which role in both, the mainstreaming and the changed structures later on is key and needs to consider current mandates, capacities, and liabilities. This ensures stakeholders are aware of, accept, and meet their roles and responsibilities in the long term (Doshi and Garschagen, 2024).

3.2.4 Implementation: implementation, M&E

The implementation phase of a mainstreaming process is a critical stage where the planned changes are put into action, ideally leading to tangible outcomes. It begins with developing a detailed work plan (UNDP-UNEP Poverty-Environment Initiative, 2011), which includes a timeline, clearly defined responsibilities, and thresholds for evaluating progress. This plan is essential to ensure the effectiveness of the mainstreaming efforts, providing a structured approach to guide the process. A key consideration at this stage is whether to introduce pilot projects (Bleby and Foerster, 2023), which allow for testing certain changes through experimentation. If pilots are deemed useful, specific timelines and indicators must be established to assess their success before scaling up.

Ensuring that all stakeholders have the necessary capacities and knowledge to implement and maintain the planned changes is another vital aspect of this phase (New et al., 2022). Capacity-building efforts may be needed to equip actors with the skills and understanding required for successful implementation. Coordination is also crucial throughout the implementation process. An oversight body should be in place to guide and support implementers, particularly in navigating challenges such as entrenched norms, established practices, or power dynamics that could hinder progress (Macchi and Ricci, 2016).

Another important sub-component that must be addressed during the implementation phase is resource mobilization. However, it differs from finance as an instrument in that it is meant to fund the changes, i.e., provide resources of any kind (e.g., financial, technical, human, physical) for the different roles involved in mainstreaming. That is mainstreaming enablers, designers, and connectors before it comes to the actual implementation (Adams et al., 2023).

Once the changes have been implemented, they must be officially adopted to provide both planning and implementation security. Official adoption raises awareness among stakeholders, ensures accountability, and fosters a long-term commitment to the changes (Taylor et al., 2018).

Finally, the implementation phase concludes with a focus on monitoring and evaluation. This stage ideally builds on existing structures (see process element on integration), but these need to be adapted to fit the new context and ideally cover both, process and outcome of mainstreaming (Taylor et al., 2018). Ongoing exchange and mutual learning are essential components of this phase, allowing stakeholders to reflect on progress and share insights. Monitoring and evaluation should not only measure the effectiveness of the changes but also assess policy coherence, focusing on both outputs (such as policy change) and outcomes (changes in practices; Runhaar et al., 2018).

3.3 Validation of the applicability of the mainstreaming protocol

To validate the usefulness and applicability of the protocol, we made use of the research project under which the protocol was developed. The LIRLAP project focused on linking disaster risk governance and land-use planning with a particular emphasis on the mainstreaming of adaptation in urban development planning.

Metro Manila, the capital region of the Philippines and one of the LIRLAP case studies, serves as the nation's political, economic, and educational center. Highly prone to various natural hazards and challenged by rapid urbanization, the region is under high pressure to adapt—particularly considering the number of vulnerable residents living in highly exposed informal settlements across the region. While the Philippines have advanced governance structures, including integrated approaches to disaster risk reduction and CCA for many years (Lasco et al., 2009; Cuevas, 2017), challenges concerning the governance of informal settlement upgrading and/or relocation as urban adaptation measures persist (Du et al., 2022; Lauer et al., 2024).

To assess whether the developed protocol and checklist were considered useful in addressing the existing challenges, two rounds of feedback were elicited from identified prospective end-users. First, we conducted an online survey with the aim of assessing the comprehensiveness, usability, and utility of the protocol and checklist from a user perspective, as well as preparing respondents for participation in a subsequent workshop. The selection process for survey participants began with an initial investigation to determine which institutions are involved in upgrading and resettlement projects at both the national and local scales. Together with LIRLAP project partners in Metro Manila, this list was refined, and the prospective survey participants were contacted, many of whom had already been involved in various aspects of the LIRLAP project over the years prior. In September 2024, we conducted a policy workshop with 35 representatives from various government and non-government agencies and institutions involved in upgrading and resettlement in Manila to further validate the developed protocol and checklist.

3.3.1 Online survey evaluation

The online-based, rapid, and user-focused evaluation of the protocol was comprised of four central questions around (1) its completeness; (2) the order of the elements; (3) whether respondents found the combination of an overarching protocol and more detailed checklist useful; and (4) whether respondents would use the protocol for mainstreaming.

The evaluation process yielded a predominantly positive response. All respondents agree that the protocol covers all relevant elements that should be considered in a holistic mainstreaming process (N=18), and all but one respondent confirm that the order of the elements is realistic. One respondent suggests shifting the allocation of resources prior to the formulation of plans, citing the advantage of enhanced planning efficacy when budgetary constraints and limits are known. Given that this suggestion was only raised once, the original order was kept.

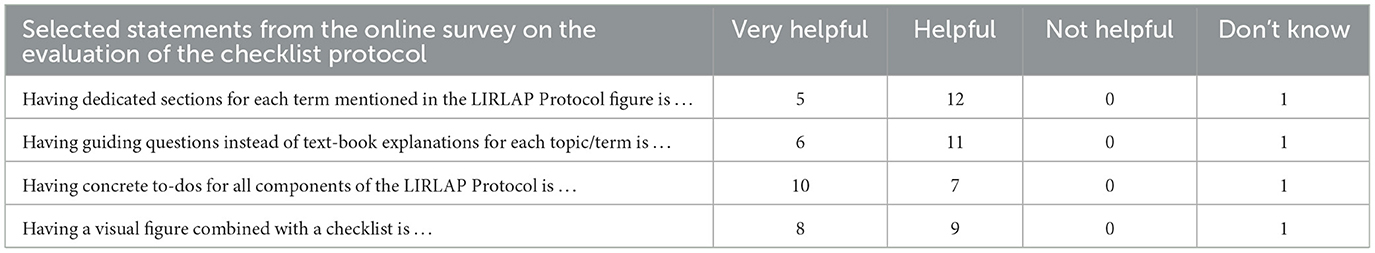

Most respondents find the dedicated sections and guiding questions in the checklist, which accompanies the mainstreaming protocol, helpful (see Table 1). The evaluation process revealed that more than half of the respondents find the concrete tasks enumerated in the checklist to be very helpful.

Finally, six out of 18 respondents confirmed that they “would definitely build on it [the protocol and checklist] to structure the work process” if they had to implement a mainstreaming process. Another eight respondents stressed that they “would consider it as helpful, but I [they] have other supportive material to build on for mainstreaming, too.” Only three respondents were unsure how it could be useful for them. None of the respondents answered that they would not use it if they had to implement a mainstreaming process. It should be noted that the small number of survey respondents limits the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. However, these initial survey results were further bolstered by the subsequent workshop.

3.3.2 Application during the policy workshop as a guiding tool for planning

On September 17, 2024, a policy workshop was convened in Metro Manila with the objective of enhancing the consideration of informal settlement upgrading and resettlement in urban development planning. The workshop brought together 35 participants representing national government agencies, local government units, community organizations, civil society organizations, and academia, each involved in various facets of urban planning in the Philippines. The agenda included introductory presentations outlining the context of mainstreaming and the structure of the protocol, followed by two interactive group work sessions. In the first session, participants collaboratively prioritized suggested mainstreaming entry points, while the second session focused on developing one selected option into a comprehensive mainstreaming approach. This development process emphasized the identification of appropriate instruments, actors and their responsibilities, formulation of workplans, and consideration of financing mechanisms within the constraints of the workshop format.

Participants were provided with the mainstreaming protocol and checklist and were instructed to utilize them during the sessions as planning tools to help guide the brainstorming process. Moderators were instructed to use the elements of the protocol as a structure to visualize the outcomes of the sessions. Researchers from the project were present in each of the sessions, observing and evaluating the utility of the protocol and checklist. The results of this evaluation were exchanged in meetings following the workshop.

Participant feedback and observer notes indicated that the protocol's categories served as a valuable tool for guiding the brainstorming process. The protocol was particularly effective in breaking down the development of mainstreaming solutions into manageable components, thereby enabling participants to approach the task more systematically. This structured approach not only facilitated the consideration of various solutions but also encouraged participants to integrate their proposals within existing policy structures, legislation, and institutions.

Another notable strength of the protocol was its ability to reveal specific challenges in the mainstreaming process, such as financial constraints, conflicting stakeholder priorities, and differing opinions. By making these issues explicit, the protocol fostered open discussion and enabled participants to address potential barriers collaboratively. Additionally, the protocol served as a safeguard to ensure that critical elements of the process were not overlooked, fostering more comprehensive discussions and allowing for the development of more realistic and holistic solutions. The tool also proved beneficial in building capacity among participants who were less accustomed to working in such contexts, enhancing their ability to contribute meaningfully.

However, it was noted that the accompanying checklist was not utilized during the sessions. Observers attributed this to the checklist's level of detail, which may have been less suited for the collaborative and time-limited format of the workshop. Despite this limitation, the protocol itself was deemed a helpful and effective instrument for supporting mainstreaming efforts in urban development planning.

4 Discussion

As we showed, there is a rich body of literature on mainstreaming in the field of CCA and environmental policies. Despite growing knowledge, gaps in a harmonized understanding and conceptualization of mainstreaming persist (Adams et al., 2023), evidence proving the success of mainstreaming is scarce and geographical biases leave critical knowledge gaps regarding mainstreaming in highly at-risk contexts (Rogers et al., 2023). Furthermore, there is a lack of pragmatic, user-centered guidance to support the implementation of mainstreaming processes in real-world settings.

Mainstreaming has been proposed as a valuable means to integrate dedicated (narrow-scope) adaptation plans and policies across sectors and scales in urban development (Lyles et al., 2018; Reckien et al., 2019), thereby advancing urgently required urban adaptation. However, the relative absence of actionable guidance is worrisome, particularly for cities in the Global South, where the risks and pressures associated with climate change are especially acute.

While this paper does not seek to resolve the diverse and sometimes conflicting terminology and conceptual frameworks of mainstreaming, it emphasizes the importance of pragmatic guidance for implementation (New et al., 2022). Only through the widespread application of mainstreaming processes—leading to tangible outcomes—can it be evaluated if mainstreaming successfully advances on the ground adaptation. Conceptual and theoretical advances in the field of mainstreaming are predominately contributing to the analysis and evaluation of existing mainstreaming processes, which, while important, are inherently secondary to their implementation. To illustrate: Whether classifying a mainstreaming process as integrative or transformational (Gupta, 2010), or normative, organizational or procedural (Persson, 2004), is primarily of analytical relevance, whereas practitioners require clear, actionable steps for implementation.

Above all, we aimed to provide scientifically informed, practical guidance for practitioners and decision-makers engaged in planning and implementing mainstreaming processes. Easy-to-understand and user-focused guidance has proven useful in other contexts, e.g., the formulation of national or international climate frameworks to guide decision-makers' climate actions or guidelines that help translate national climate action to sub-national levels (New et al., 2022).

The proposed mainstreaming protocol bridges the gap between science and practice. While making use of existing mainstreaming manuals that focus on practical applicability (e.g., Dalal-Clayton and Bass, 2009; Olhoff and Schaer, 2010; Taylor et al., 2018), our protocol differs from such guidelines in three distinct ways: first, it is based on sound scientific findings on mainstreaming, particularly enablers and barriers (Cuevas, 2016a; Runhaar et al., 2018; New et al., 2022) as well as scientifically identified elements and processes of mainstreaming (Wamsler and Osberg, 2022; Adams et al., 2023). Second, it is concise, user-focused, and pragmatic to ensure its applicability. We put a particular emphasis on unpacking the most crucial points in a mainstreaming process. That is, one, to decide whether mainstreaming is the most effective way forward (Candel, 2021), and two, to address implementation challenges (Mogelgaard et al., 2018). Concerning the former, a dedicated “to do” raises awareness and calls for sound consideration of this question. The latter is concretely addressed through questions and to-dos for the selection of instruments, the joint determination of roles and responsibilities, and the effective implementation, including pilots, workplans for planning, and stakeholder engagement. With this, we hope to guide users such as urban planners and decision-makers in overcoming scientifically identified barriers to mainstreaming and practically realizing enabling environments for change through mainstreaming. Third, to ensure the applicability of the mainstreaming protocol, we conducted an online-based evaluation answered by potential users. It directly assessed how potential future users evaluate the completeness and utilization of the mainstreaming protocol, with positive results. The results were validated through an indirect evaluation of the protocol's use through its application during a workshop with potential users in Metro Manila. Respondents deemed it comprehensive and valuable as an alone-standing or complementary tool for planning and implementing mainstreaming processes. Such user-centered evaluation is rare in the context of mainstreaming guidelines to our knowledge, despite evidence proving that stakeholder involvement in such processes is crucial for the uptake of such tools (Palutikof et al., 2019). The user-centered evaluation is an initial step in the direction of co-design of a mainstreaming tool.

The application to the example of Metro Manila has proven the protocol's utility in two ways. First, it was useful for participants as an analytical tool to lay open that adaptation is already widely considered, i.e., mainstreamed in the city's urban planning. The context assessment in fact revealed that it is a highly over-regulated context in which policy incoherence and redundancies lead to confusion and administrative overload which ultimately hinder the implementation. Second, the mainstreaming protocol helped users to address this challenge by guiding them in the process to reduce incoherences across sectors, scales, and actors. Participants identified entry points, i.e., windows of opportunity, in the existing structures to introduce change. Following the protocol, they discussed amendments to existing laws, financial mechanisms, institutional mandates, and policy plans as instruments for facilitating the implementation of mainstreaming in the context of urban planning. The discussions revealed that no new legislation is needed in Metro Manila; instead streamlining of different regulations, laws, mandates, and financial mechanisms appeared as more useful to facilitate better adaptation action. The identification of streamlining as a potential solution to the highly regulated urban development processes in Metro Manila was realized through the cooperation of the various stakeholders guided by the protocol's elements. Jointly discussing visions, entry points, instruments, and roles and responsibilities of stakeholders revealed that instead of gaps in mainstreaming, the urban planning context already comprehensively considers various CCA measures, which has led to overregulation and high levels of complexity in regulations and processes of urban planning. Streamlining existing regulations, processes, and mandates is therefore key for more coherent urban planning processes and implementation. The outcome shows the usefulness of the protocol as an analytical lens and guidance for the users to understand the context, identify opportunities, and address them through coherent and jointly planned solutions that build on existing structures.

Despite being validated in Metro Manila, the protocol is also applicable beyond the case study as it is sufficiently abstract to be widely applied. At the same time, it is still concrete enough to practically guide implementers through questions and to-dos through the process without being prescriptive. Rather, the protocol allows them to decide upon the level of integration which is most effective for advancing adaptation in their particular context. The protocol does not suggest analytical categories (transformations, normative, etc.) but gives users choices to design their process in an effective, yet pragmatic way. We strongly encourage future testing and application to other contexts to further validate the protocol's utility as an analytical lens and guiding tool.

5 Conclusion

The effective integration of CCA in urban development planning is inherently context-dependent, shaped by factors such as governance structures, cultural and political dynamics, and local capacities. Whether a dedicated approach with specialized institutions, a fully mainstreamed approach that achieves cross-sectoral integration of adaptation, or a hybrid approach is most suitable for advancing adaptation in cities depends on these contextual nuances. Yet, across all settings, there is a clear and urgent need for pragmatic and actionable guidance that enables coherent policy planning and facilitates the translation of mainstreaming ambitions into concrete actions. Particularly, decision-makers at the sub-national scale are at the forefront of bringing policies and plans into fruition (Uittenbroek et al., 2013; Runhaar et al., 2018), hence capacitating them with adequate tools is essential.

This study responds to that need by presenting a user-oriented, scientifically grounded mainstreaming protocol and checklist designed to support policymakers and practitioners in embedding adaptation within urban planning processes. The protocol's utility was validated through a user-centered online evaluation. Its initial application in Metro Manila showcased how the protocol and checklist can serve as an analytical tool for assessing the state of mainstreaming, representing an added value beyond the case study and its practical application in the realm of research, policy design, and implementation.

By bridging the gap between scientific knowledge and practical implementation, this work contributes to ongoing efforts to close the adaptation mainstreaming implementation gap (Runhaar et al., 2018; Reckien et al., 2019; Wamsler and Osberg, 2022; Rogers et al., 2023). The protocol offers a foundation for strengthening adaptation mainstreaming in urban planning and for catalyzing further research, particularly in rapidly urbanizing and climate-vulnerable cities of the Global South, where context-specific evidence and guidance remain limited.

Looking ahead, the developed protocol and checklist can serve not only as practical resources for urban planners and decision-makers, but also as analytical lenses for future research. Further empirical application and refinement in diverse urban contexts will be essential to enhance their robustness and relevance. Ultimately, advancing adaptation mainstreaming in urban planning is critical for fostering coherent, climate-resilient urban futures.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans. We conducted a voluntary, online survey and workshop-based, expert consultation. The participants provided their written and informed consent to participate in this study. The authors received consent from participants to use the submitted data in an anonymized form. The studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

BL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. MW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CC: Writing – review & editing. LG: Writing – review & editing. SI: Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – review & editing. MN: Writing – review & editing. VE: Writing – review & editing. MG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Research, Technology and Aeronautics (BMFTR) under the umbrella of the funding priority “Sustainable Development of Urban Regions” (SURE) (Grant number 01LE1906B1).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2025.1557352/full#supplementary-material

References

Adams, C., Frantzeskaki, N., and Moglia, M. (2023). Mainstreaming nature-based solutions in cities: a systematic literature review and a proposal for facilitating urban transitions. Land Use Policy 130:106661. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106661

Adams, C., Moglia, M., and Frantzeskaki, N. (2024). Realising transformative agendas in cities through mainstreaming urban nature-based solutions. Urban Forestry Urban Green. 91:128160. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2023.128160

Adelle, C., and Russel, D. (2013). Climate policy integration: a case of Déjà Vu? Environ. Policy Governance 23, 1–12. doi: 10.1002/eet.1601

Ahenkan, A., Chutab, D. N., and Boon, E. K. (2021). Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into pro-poor development initiatives: evidence from local economic development programmes in Ghana. Clim. Dev. 13, 603–615. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2020.1844611

Aleksandrova, M. (2020). Principles and considerations for mainstreaming climate change risk into national social protection frameworks in developing countries. Clim. Dev. 12, 511–520. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2019.1642180

Atanga, R. A., Inkoom, D. K. B., and Derbile, E. K. (2017). Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into development planning in Ghana. Ghana J. Dev. Stud. 14:209. doi: 10.4314/gjds.v14i2.11

Ayers, J. M., Huq, S., Faisal, A. M., and Hussain, S. T. (2014). Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into development: a case study of Bangladesh. WIREs Clim. Change 5, 37–51. doi: 10.1002/wcc.226

Bleby, A., and Foerster, A. (2023). A conceptual model for climate change mainstreaming in government. Trans. Environ. Law 12, 623–648. doi: 10.1017/S2047102523000158

Boezeman, D., and De Vries, T. (2019). Climate proofing social housing in the Netherlands: toward mainstreaming? J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 62, 1446–1464. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2018.1510768

Burns, C., Flood, S., and O'Dwyer, B. (2022). “Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into planning and development: a case study in Northern Ireland,” in Creating Resilient Futures: Integrating Disaster Risk Reduction, Sustainable Development Goals and Climate Change Adaptation Agendas, eds. S. Flood, Y. Jerez Columbié, M. Le Tissier, and B. O'Dwyer (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 129–147. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-80791-7_7

Candel, J. J. L. (2021). The expediency of policy integration. Policy Stud. 42, 346–361. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2019.1634191

Chakrabarti, P. G. D. (2017). Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction for Sustainable Development: A Guidebook for the Asia Pacific. Available online at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/knowledge-products/publication_WEBdrr02_Mainstreaming.pdf (accessed May 9, 2025).

Colven, E. (2017). Understanding the allure of big infrastructure: Jakarta's Great Garuda sea wall project. Water Alternatives 10, 250–264.

Cuevas, S. C. (2016a). Examining the Challenges in Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation Into local Land-Use Planning: The Case of Albay, Philippines. Brisbane, QLD: The University of Queensland. doi: 10.14264/uql.2016.161

Cuevas, S. C. (2016b). The interconnected nature of the challenges in mainstreaming climate change adaptation: evidence from local land use planning. Clim. Change 136, 661–676. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1625-1

Cuevas, S. C. (2017). Institutional dimensions of climate change adaptation: insights from the Philippines. Clim. Policy 18, 499–511. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2017.1314245

Dalal-Clayton, D. B., and Bass, S. (2009). The Challenges of Environmental Mainstreaming: Experience of Integrating Environment into Development Institutions and Decisions. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Dellmuth, L. M., and Gustafsson, M.-T. (2021). Global adaptation governance: how intergovernmental organizations mainstream climate change adaptation. Clim. Policy 21, 868–883. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2021.1927661

Dodman, D., Hayward, B., Pelling, M., Castan Broto, V., Chow, W., Chu, E., et al. (2022). “Cities, settlements and key infrastructure,” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds. H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. (Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press), 907–1040. doi: 10.1017/9781009325844.008

Doshi, D., and Garschagen, M. (2024). Actor-specific adaptation objectives shape perceived roles and responsibilities: lessons from Mumbai's flood risk reduction and general considerations. Reg. Environ. Change 24:164. doi: 10.1007/s10113-024-02315-3

Du, J., Greiving, S., and Yap, D. L. T. (2022). Informal settlement resilience upgrading-approaches and applications from a cross-country perspective in three selected metropolitan regions of Southeast Asia. Sustainability 14:8985. doi: 10.3390/su14158985

Duy, P. N., Chapman, L., Tight, M., Linh, P. N., and Thuong, L. V. (2018). Increasing vulnerability to floods in new development areas: evidence from Ho Chi Minh City. IJCCSM 10, 197–212. doi: 10.1108/IJCCSM-12-2016-0169

Eggenberger, M., and Partidário, M. R. (2000). Development of a framework to assist the integration of environmental, social and economic issues in spatial planning. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal 18, 201–207. doi: 10.3152/147154600781767448

Farrell, L. A. (2010). Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation into Urban Development: Lessons from Two South African Cities. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available online at: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/59569 (accessed November 6, 2023).

Friend, R., Jarvie, J., Reed, S. O., Sutarto, R., Thinphanga, P., and Toan, V. C. (2014). Mainstreaming urban climate resilience into policy and planning; reflections from Asia. Urban Clim. 7, 6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2013.08.001

Gabriel, A. G., Santiago, P. N. M., and Casimiro, R. R. (2021). Mainstreaming disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation in comprehensive development planning of the cities in Nueva Ecija in the Philippines. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 12, 367–380. doi: 10.1007/s13753-021-00351-9

García Sánchez, F. (2022). “Mainstreaming adaptation into urban planning: projects and changes in regulatory frameworks for resilient cities,” in Business and Policy Solutions to Climate Change: From Mitigation to Adaptation, eds. T. Walker, S. Wendt, S. Goubran, and T. Schwartz (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 265–289. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-86803-1_12

García Sánchez, F., Solecki, W. D., and Ribalaygua Batalla, C. (2018). Climate change adaptation in Europe and the United States: a comparative approach to urban green spaces in Bilbao and New York City. Land Use Policy 79, 164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.08.010

Garschagen, M., and Romero-Lankao, P. (2015). Exploring the relationships between urbanization trends and climate change vulnerability. Clim. Change 133, 37–52. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-0812-6

Garschagen, M., Surtiari, G. A. K., and Harb, M. (2018). Is Jakarta's new flood risk reduction strategy transformational? Sustainability 10:2934. doi: 10.3390/su10082934

Gupta, J. (2010). “Mainstreaming climate change: a theoretical exploration,” in Mainstreaming Climate Change in Development Cooperation, ed. J. Gupta (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 67–96. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511712067.004

Hanna, C., Cretney, R., and White, I. (2022). Re-imagining relationships with space, place, and property: the story of mainstreaming managed retreats in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Planning Theory Prac. 23, 681–702. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2022.2141845

Howlett, M. P., and Saguin, K. (2018). Policy Capacity for Policy Integration: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Research Paper Series 18-06, 1–21. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3157448

Khailani, D. K., and Perera, R. (2013). Mainstreaming disaster resilience attributes in local development plans for the adaptation to climate change induced flooding: a study based on the local plan of Shah Alam City, Malaysia. Land Use Policy 30, 615–627. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.05.003

Koch, F. (2018). Mainstreaming adaptation: a content analysis of political agendas in Colombian cities. Clim. Dev. 10, 179–192. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2016.1223592

Lasco, R. D., Pulhin, F. B., Jaranilla-Sanchez, P. A., Delfino, R. J. P., Gerpacio, R., and Garcia, K. (2009). Mainstreaming adaptation in developing countries: the case of the Philippines. Clim. Dev. 1, 130–146. doi: 10.3763/cdev.2009.0009

Lauer, H., Chaves, C. M. C., Lorenzo, E., Islam, S., and Birkmann, J. (2024). Risk reduction through managed retreat? Investigating enabling conditions and assessing resettlement effects on community resilience in Metro Manila. Natural Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 2243–2261. doi: 10.5194/nhess-24-2243-2024

Leitold, R., and Diez, J. R. (2019). Exposure of manufacturing firms to future sea level rise in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J. Maps 15, 13–20. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2018.1548385

Linke, S., Erlwein, S., van Lierop, M., Fakirova, E., Pauleit, S., and Lang, W. (2022). Climate change adaption between governance and government—collaborative arrangements in the city of Munich. Land 11:1818. doi: 10.3390/land11101818

Lyles, W., Berke, P., and Overstreet, K. H. (2018). Where to begin municipal climate adaptation planning? Evaluating two local choices. J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 61, 1994–2014. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2017.1379958

Macchi, S., and Ricci, L. (2016). “15. Climate change adaptation through urban planning: a proposed approach for Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania,” in Planning to Cope With Tropical and Subtropical Climate Change (Warsaw: De Gruyter Open Poland), 267–289. doi: 10.1515/9783110480795-016

Metzger, J., Carlsson Kanyama, A., Wikman-Svahn, P., Mossberg Sonnek, K., Carstens, C., Wester, M., et al. (2021). The flexibility gamble: challenges for mainstreaming flexible approaches to climate change adaptation. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 23, 543–558. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2021.1893160

Mogelgaard, K., Dinshaw, A., Ginoya, N., Gutiérrez, M., Preethan, P., and Waslander, J. (2018). From Planning to Action: Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation into Development. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at: https://www.wri.org/publication/climate-planning-to-action (Accessed May 9, 2025).

Mugari, E., and Nethengwe, N. S. (2022). Mainstreaming ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction: towards a sustainable and just transition in local development planning in rural South Africa. Sustainability 14:12368. doi: 10.3390/su141912368

Nassef, Y. (2012). “Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into development planning,” in Climate Change in Asia and the Pacific: How Can Countries Adapt? (New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd), 328–337. doi: 10.4135/9788132114000.n26

New, M., Reckien, R., Viner, D., Adler, C., Cheong, S.-M., Conde, C., et al. (2022). “Decision-making options for managing risk,” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, eds. H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. (Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 2539–2654. doi: 10.1017/9781009325844.026

Newman, P. (2020). Cool planning: how urban planning can mainstream responses to climate change. Cities 103:102651. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102651

Nunan, F., Campbell, A., and Foster, E. (2012). Environmental mainstreaming: the organisational challenges of policy integration: public administration and development. Public Admin. Dev. 32, 262–277. doi: 10.1002/pad.1624

Olhoff, A., and Schaer, C. (2010). Screening Tools and Guidelines to Support the Mainstreaming of Climate Change Adaptation into Development Assistance – A Stocktaking Report. New York, NY: UNDP. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/publications/stocktaking-tools-and-guidelines-mainstream-climate-change-adaptation (Accessed May 9, 2025).

Palutikof, J. P., Street, R. B., and Gardiner, E. P. (2019). Looking to the future: guidelines for decision support as adaptation practice matures. Clim. Change 153, 643–655. doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02404-x

Persson, K. (2004). Environmental Policy Integration: An Introduction. Stockholm: Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI). Available online at: https://mediamanager.sei.org/documents/Publications/Policy-institutions/EPI.pdf (Accessed May 9, 2025).

Pieterse, A., Du Toit, J., and Van Niekerk, W. (2021). Climate change adaptation mainstreaming in the planning instruments of two South African local municipalities. Dev. South. Afr. 38, 493–508. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2020.1760790

Rauken, T., Mydske, P. K., and Winsvold, M. (2015). Mainstreaming climate change adaptation at the local level. Local Environ. 20, 408–423. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2014.880412

Reckien, D., Salvia, M., Pietrapertosa, F., Simoes, S. G., Olazabal, M., De Gregorio Hurtado, S., et al. (2019). Dedicated versus mainstreaming approaches in local climate plans in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 112, 948–959. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2019.05.014

Rogers, N. J. L., Adams, V. M., and Byrne, J. A. (2023). Factors affecting the mainstreaming of climate change adaptation in municipal policy and practice: a systematic review. Clim. Policy 23, 1327–1344. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2023.2208098

Runhaar, H., Wilk, B., Persson, Å., Uittenbroek, C., and Wamsler, C. (2018). Mainstreaming climate adaptation: taking stock about “what works” from empirical research worldwide. Reg. Environ. Change 18, 1201–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10113-017-1259-5

Saito, N. (2013). Mainstreaming climate change adaptation in least developed countries in South and Southeast Asia. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 18, 825–849. doi: 10.1007/s11027-012-9392-4

Scheiber, L., Sairam, N., Hoballah Jalloul, M., Rafiezadeh Shahi, K., Jordan, C., Visscher, J., et al. (2024). Effective adaptation options to alleviate nuisance flooding in coastal megacities–learning from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Earth's Futur. 12:e2024EF004766. doi: 10.1029/2024EF004766

Schipper, E. L., Revi, A., Preston, B. L., Carr, E. R., Eriksen, S. H., Fernández-Carril, L. R., et al. (2022). “Climate resilient development pathways,” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds. H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Craig, et al. (Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 2655–2807. doi: 10.1017/9781009325844.027

Sen, J., and Dhote, M. (2023). “Mainstreaming biodiversity in urban habitats for enhancing ecosystem services: a conceptual framework,” in Climate Crisis: Adaptive Approaches and Sustainability, eds. U. Chatterjee, R. Shaw, S. Kumar, A. D. Raj, and S. Das (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 349–368. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-44397-8_19

Storch, H., and Downes, N. K. (2011). A scenario-based approach to assess Ho Chi Minh City's urban development strategies against the impact of climate change. Cities 28, 517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2011.07.002

Taylor, H., Reid, J., Rinschede, T., Sett, D., Fee, L., Cea, L., et al. (2018). Climate Change and National Urban Policies in Asia and the Pacific: A Regional Guide for Integrating Climate Change Concerns into Urban-related Policy, Legislative, Financial and Institutional Frameworks. Nairobi and Bangkok: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) and United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP).

Tellman, B., Sullivan, J. A., Kuhn, C., Kettner, A. J., Doyle, C. S., Brakenridge, G. R., et al. (2021). Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods. Nature 596, 80–86. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03695-w

ten Brinke, N., Kruijf, J. V., Volker, L., and Prins, N. (2022). Mainstreaming climate adaptation into urban development projects in the Netherlands: private sector drivers and municipal policy instruments. Clim. Policy 22, 1155–1168. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2022.2111293

Tosun, J., and Lang, A. (2017). Policy integration: mapping the different concepts. Policy Stud. 38, 553–570. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2017.1339239

Uittenbroek, C. J. (2016). From policy document to implementation: organizational routines as possible barriers to mainstreaming climate adaptation. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 18, 161–176. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2015.1065717

Uittenbroek, C. J., Janssen-Jansen, L. B., and Runhaar, H. A. C. (2013). Mainstreaming climate adaptation into urban planning: overcoming barriers, seizing opportunities and evaluating the results in two Dutch case studies. Reg. Environ. Change 13, 399–411. doi: 10.1007/s10113-012-0348-8

UNDP-UNEP Poverty-Environment Initiative (2011). Guide Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation into Development Planning: A Guide for Practitioners. Nairobi: UNDP-UNEP.

Wade, M. (2019). Hyper-planning Jakarta: the Great Garuda and planning the global spectacle. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 40, 158–172. doi: 10.1111/sjtg.12262

Wamsler, C., and Osberg, G. (2022). Transformative climate policy mainstreaming – engaging the political and the personal. Glob. Sustain. 5:e13. doi: 10.1017/sus.2022.11

Wamsler, C., and Pauleit, S. (2016). Making headway in climate policy mainstreaming and ecosystem-based adaptation: two pioneering countries, different pathways, one goal. Clim. Change 137, 71–87. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1660-y

Wannewitz, M., Ajibade, I., Mach, K. J., Magnan, A., Petzold, J., Reckien, D., et al. (2024). Progress and gaps in climate change adaptation in coastal cities across the globe. Nat. Cities 1, 610–619. doi: 10.1038/s44284-024-00106-9

Wellstead, A., and Stedman, R. (2015). Mainstreaming and beyond: policy capacity and climate change decision-making. Michigan J. Sustain. 3. doi: 10.3998/mjs.12333712.0003.003

Keywords: mainstreaming adaptation, urban planning, urban development practices, retreat, resettlement, in-situ upgrading, Philippines

Citation: Liss BM, Wannewitz M, Chaves CM, Grobusch LC, Islam S, Magnaye DC, Napalang MSG, Eugenio VF and Garschagen M (2025) Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into urban planning—A pragmatic protocol to tackle the implementation gap. Front. Clim. 7:1557352. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1557352

Received: 08 January 2025; Accepted: 20 June 2025;

Published: 21 July 2025.

Edited by:

Joe Ravetz, The University of Manchester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Rajiv Kumar Srivastava, Texas A&M University, United StatesAnika N. Haque, University of York, United Kingdom

John W. Day, Louisiana State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Liss, Wannewitz, Chaves, Grobusch, Islam, Magnaye, Napalang, Eugenio and Garschagen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bethany M. Liss, Yi5saXNzQGxtdS5kZQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Bethany M. Liss

Bethany M. Liss Mia Wannewitz

Mia Wannewitz Carmeli Marie Chaves

Carmeli Marie Chaves Lena C. Grobusch

Lena C. Grobusch Sonia Islam

Sonia Islam Dina C. Magnaye

Dina C. Magnaye Ma Sheilah G. Napalang

Ma Sheilah G. Napalang Vincent F. Eugenio2

Vincent F. Eugenio2 Matthias Garschagen

Matthias Garschagen