- 1CEARC Research Center, Université Paris Saclay, Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Guyancourt, France

- 2Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, University of Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 3Center for the Study of the Sciences and the Humanities, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

This article analyzes the role of share and support networks (SSNs) in the Republic of Sakha (Russian Federation) in the context of accelerated climatic, environmental and socio-economic changes. The material associated to four fieldworks conducted in the Republic of Sakha has been mobilized: the first one in obtained Tiksi in November 2014, the second and third one in the city of Yakutsk in September 2015, and June 2018 respectively, and the fourth one in Tiksi and Bykovsky in July 2019. The qualitative analysis of the interviews revealed that food-centered SSNs are a salient topic in local narratives. They shape the current regional socio-economic configuration and play a key role in identity processes. They allow residents from different parts of the Republic of Sakha to have access to traditional food, but also enhance residents’ feeling of safety and wellbeing. Interviewees identified multiple manifestations of changes in climate and permafrost that are currently exerting increasing pressure on SSNs. These increase the difficulties to practice traditional activities and therefore to access black food (meat and fish) which is the base of the Yakutian diet. Local narratives demonstrate that the impacts of such changes on SSNs can exceed the merely local sphere and can entail severe and long-lasting consequences at a regional scale too. Furthermore, we identify shared representations of an ideal past—that of the Soviet Union—as an immaterial source of resilience through its potential to foster collective action.

1 Introduction

In 2019, the Belmont Forum organized a Collaborative Research Action (CRA) call for proposals specifically focused on Arctic Resilience. The rationale for this call strongly emphasized the need for a paradigm shift toward a systemic approach in analyzing the interconnectedness of seven resilience elements: natural, social, financial, cultural, and human capital, as well as infrastructure and knowledge (Belmont Forum, 2019).

The two co-authors of this paper, who previously collaborated on permafrost thaw research in the Republic of Sakha (Doloisio and Vanderlinden, 2020), joined the SeMPER-Arctic project consortium in response to this call. This consortium successfully secured funding through the CRA initiative. The resulting project, the SeMPER-Arctic project, introduced a narrative approach to resilience research in the Arctic (see Wardekker et al., 2022). By leveraging the potential of storytelling, this approach aimed to account for the systemic interactions underlying resilience. By engaging into narrative-centered research the consortium considered that a voice could be given to local communities when it comes to envision its future in the face of upheavals.

Preparatory fieldwork, conducted within partner communities in the Arctic led to the identification of three key research streams for further exploration: sensemaking, place attachment, and extended networks (Gherardi et al., 2019). These concepts were recognized as having significant potential to elucidate how the western concept of resilience manifests itself locally, especially within an Arctic context. This paper focuses on the results derived from the exploration of the “extended networks” research stream. It aims at understanding the specific interplay of share and support networks (SSNs) in the Republic of Sakha in a context of accelerated climatic changes.

In this introduction, we will: (a) Provide a brief review of the state of the art in SSNs in the Arctic (Section 1.1); (b) present how the existing literature connects local and extended SSNs to the resilience of remote Arctic communities (Section 1.2), and (c) conclude by presenting the research question that emerged from Sections 1.1 and 1.2 (Section 1.3).

1.1 Local and non-local SSNs in the Arctic region

Local social networks, whether as determinants of or shaped by sharing practices and relationality, have long been a focus of anthropological research in the Arctic (e.g., Collings et al., 1998; Berkes and Jolly, 2002; Kishigami et al., 2006; Ksenofontov et al., 2017; Ready and Power, 2018). Alfred and Corntassel (2005) suggest that relationships “are the spiritual and cultural foundations of Indigenous peoples.” According to Tynan (2021) “relationality is how the world is known and how we, as Peoples, Country, entities, stories and more-than-human kin know ourselves and our responsibilities to one another“. Salmón (2000) developed the idea of “kinship ecology”1, which refers to the acknowledgment that “indigenous people are affected by and, in turn, affect the life around them.” This complex network of relationships as well as the human recognition of their role contribute to the maintenance of ecosystems’ balance. Sharing—as an expression of indigenous relationality—is a source of emotional satisfaction, joy, and freedom among many Arctic communities (Bodenhorn, 2000) and remains a key pillar of most Indigenous cultures (Solovyeva and Kuklina, 2020). Land and food-based practices (including sharing and distributing food within the community) are, according to Miltenburg et al. (2022) guided by three relational principles: responsibility, relationality, and reciprocity. These concepts are disruptive to western epistemologies which are rooted in hierarchical dichotomies and mainly ruled by the principles of linearity and separation (Dudgeon and Bray, 2019).

Extended networks can be therefore interpreted are spheres of social and cultural life where relationality is expressed in ways that exceed the mere production and distribution of food. Sharing food and other goods enhances social cohesion and wellbeing in Arctic communities (BurnSilver et al., 2022; Doloisio, 2022; Doloisio, 2024). In this sense, it becomes evident that indigenous relationality cannot be understood outside the process of connection (Dudgeon and Bray, 2019). For instance, share and support networks—as a relational practice-, enable Peoples to strengthen their bonds with other entities (land, animals) and all of the elements involved in such practices in a way that they become more unified as one (Tynan, 2021). As a result of the growing popularity of social media among northern residents led to the emergence of digital forms of such social networks, also known as “online social networks” (Clemons, 2009).

Contemporary Arctic livelihoods strongly depend on (1) households harvesting foods from their surrounding environment, (2) households generating cash income (through salaries or wages), and (3) households and social groups redistributing food and other resources through kinship relationships (Langdon and Worl, 1981; Wolfe and Walker, 1987; BurnSilver and Magdanz, 2017). Extended networks connecting remote Arctic communities to other communities or regional and national hubs have been studied in relation to rural–urban migration (e.g., Sukneva and Laruelle, 2019; Howe and Huskey, 2022).

One consequence of increasing urban concentration in the Arctic is the rise of geographically extended networks of individuals. For these individuals, their place of origin remains central to defining their identity, shaping their social interactions, and determining where they turn in times of duress (Argounova-Low, 2007). Furthermore, these “diasporas” are closely associated to urban infrastructure, health services, and other resources and facilities from the urban world (Bogdanova et al., 2022). Such SSNs are therefore crucial in times of stress, enabling individuals to seek external intervention and support. Our working hypothesis is that SSN narratives are closely tied to narratives of change, linking community-level perspectives with science-based discourses on global change and resilience.

1.2 Local, and extended, SSNs and arctic resilience

For the work presented in this paper, we approached resilience using Wardekker’s resilient community development framework (Wardekker, 2021). Indeed, the results presented by Doloisio (2024) indicate that this framing aligns with a systemic approach designed to empirically analyze community-level resilience in the Siberian Arctic.

This resilient community development framework can be characterized as follows:

“Community resilience takes a people-centric approach. It explores how communities navigate disturbances and adversity through the interplay of local capacities, resources, and adaptation” (Wardekker, 2021, p. 6).

Thus, for our purposes, we adopted a specific framing of resilience that emphasizes the articulation of changes and disturbances with local characteristics. In the Arctic, several authors have engaged with similar approaches—without focusing precisely or explicitly on resilience.

Collings (2011), based on field observations in the Northwest Territories, indicates that social networks associated with country food2 sharing among hunters strengthen resilience in response to environmental changes but are less effective in addressing political or economic shifts. Collings et al. (2016) further demonstrate that access to country food—facilitated by a central position within family networks—is a key factor in ensuring food security.

Ready (2016) and Ready and Power (2018), following fieldwork in the Canadian Arctic, show that sharing-based networks function as sources of both social capital and food security, though their benefits are not equally distributed. Ready (2016) also observes that sharing networks are primarily based on reciprocity among high-harvest households, a dynamic that has the potential to exacerbate inequalities in food access. In contrast, BurnSilver et al. (2022), studying communities in Alaska, find that food-sharing networks contribute to social resilience through two mechanisms: reducing inequalities and enhancing social cohesion. Their findings highlight the localized dynamics of food-sharing networks and their role in resilience.

In northern Siberia, Ziker and Fulk (2018) report that self-organized food distribution networks are crucial for maintaining food security and household resilience amid rapid environmental change, based on their observations in the Ust’-Avam community on the Taimyr Peninsula. Ziker and Fulk (2019) further emphasize the importance of cooperation within sharing networks, highlighting their central role in sustaining resilience. Graybill (2013) found that in a Russian Arctic context, where federal aid is minimal, subsistence resources play a key role for survival. Government bureaucracy are—more often than not—a hindrance for resilience. In such context, informal networks become essential for northern communities (Goldstein, 2008). Solovyeva and Kuklina (2020) thoroughly explored how remote indigenous communities utilize and modify their sharing traditions in order to adapt to the ongoing social and environmental changes, and how can this enhance resilience. Their research focused on the village of Khara Tumul (Oymyakonskiy ulus) and the city of Yakutsk.

1.3 Networks and resilience: an exploratory research question

Sections 1.1 and 1.2, along with the progress made within the SeMPER-Arctic project, led us to formulate the following exploratory research question:

“In the narratives of local community members, what is the interplay between community-level resilience and share and support networks in the Republic of Sakha?”

Building on the existing literature and on Wardekker’s (2021) characterization of the community resilience framework, we linked the central concepts of this question to the following dimensions:

• Community resilience: disturbances, adversity, and navigating their interplay

• Share and support networks: local capacities and internal and external resources.

To explore this question, we adopted a case study approach focusing on two communities in the Siberian Arctic: Tiksi and Byskovsky (Republic of Sakha, Russian Federation).

2 Methods

Originally, within the SeMPER-Arctic project, we planned to conduct new fieldwork in two settlements in the Siberian Arctic: Tiksi and Bykovsky. However, the COVID-19 pandemic initially prevented us from fully carrying out this research. Subsequently, the Russian war in Ukraine made it impossible to maintain collaboration with our Russian colleagues.

To preserve the comparative potential of the SeMPER-Arctic project, we opted to rely on hermeneutic units integrating various corpora gathered in previous years. In this section, we briefly introduce the two settlements that are the focus of our study, followed by an overview of our hermeneutic unit and analytical strategy.

2.1 Yakutsk: the capital city of the region

Yakutsk is the capital city of the Republic of Sakha and is located in the Tuymaada Valley. It is 450 km South from the Arctic Circle. Yakutsk was officially funded in 1632 and is currently considered to be the largest city located in the Russian Federation permafrost zone. In the recent decades, it has received an increasing number of indigenous persons from other regions (Fondahl et al., 2015). Although since 1991 the general trend in Arctic communities indicate a population decline, there were some exceptions, like Yakutsk. These urban centers registered population growth, especially those controlled by energy exploitation, as well as those with good infrastructure and transit accessibility (Reisser, 2016). Today, over 250,000 people live in this city.

2.2 Tiksi and Bykovsky: two settlements in the Bulunsky District

Tiksi and Bykovsky are located in the Bulunsky District, in the northern part of the Republic of Sakha Russian Federation (see Figure 1). Tiksi lies 40 km south of Bykovsky. While Tiksi is inland, Bykovsky is situated on the Bykovsky Peninsula. Tiksi’s harbor is naturally sheltered by this peninsula. Tiksi is the only urban settlement and the administrative center of the Bulunsky District. It is located 2,000 km away from Yakutsk by land transport, 1,270 km by air and 1,703 km by waterway.

Figure 1. Relative position of Yakutsk and the Bulunsky District within the Republic of Sakha. Source: https://www.sharada.ru/katalog/maps/regions/dalnevostochnyj-fed-okrug/respublika-saha-jakutija.

Bykovsky has ice-rich sediments known as the Ice Complex, which are highly sensitive to both thermo-erosion and thermokarst processes (Meyer et al., 2002). Tiksi serves as the only administrative center of the Bulunsky District, whereas Bykovsky is an indigenous rural settlement where professional and subsistence fishing are the main economic activities.

Tiksi’s population is ethnically diverse, with Russians as the predominant group, followed by Yakuts, Evenki, Evens, and Ukrainians. Bykovsky, in contrast, is primarily an Evenki settlement, with smaller populations of Sakha, Even, and Russian residents.3

Among residents of neighboring villages in the Bulunsky District, Tiksi is perceived as a prosperous settlement with better services, job opportunities, and educational resources. However, one of the main concerns in recent decades has been the rising cost of housing in Tiksi. After the Soviet breakup, many people abandoned their properties and migrated to other regions of Russia or even other countries in response to the economic crisis. This lead to a In Bykovsky, however, many residents stayed. Locals noted that the Artel Arktika played a crucial role in sustaining the community by continuing to provide fishing industry jobs for men after perestroika (Doloisio, 2022).

The entire region was impacted by the Soviet Union disintegration in 1991, especially northern settlements like Tiksi and Bykovsky. Switching from a centrally-planned-economy to a market economy lead to the liberalization of prices as well as the costs of northern development systems. The Arctic region was severely impacted since all subsidies and political forms of support were equally cut down (Heleniak, 1999). As a result, smaller Arctic settlements experienced massive out-migration, leaving behind numerous “ghost cities” (Doloisio, 2022). The disappearance of Soviet structures lead to a profound reorganization and the new national political structure became sharply vertical. This renders—according to locals—almost impossible to obtain help from the Federal government, or to request the modification of normative aspects such as fishing/hunting quotas because of how long these procedures take. This reflects both the geographical but also symbolic distance that exists between remote regions like Yakutia and the Kremlin. This is not a minor consideration, since it shapes the mechanisms and options that local residents from Tiksi and Bykovsky evaluate as legitimate, but also accessible in face of upheavals.

2.3 Hemeneutic unit

Our hermeneutic unit consisted of (a) four sets of interviews spanning 5 years of inquiry (November 2014, September 2015, June 2018, July 2019); (b) 11 years of notes taken during exchanges with various key informants (Vanderlinden, 2013–2024); and (c) field diaries (Vanderlinden: September 2015, June 2018; Doloisio: June 2018, July 2019).

This article thus draws on material from four field studies conducted in the Republic of Sakha: the first in Tiksi in November 2014 (n = 15, stakeholders in Tiksi), the second in the city of Yakutsk in September 2015 (n = 12, civil servants and local authorities), the third in June 2018 (youth connected to Tiksi), and the fourth in Tiksi and Bykovsky in July 2019 (n = 34, residents). These field studies were the result of coordinated efforts between researchers from the CEARC French research laboratory and Russian colleagues from NEFU and the Institute for Humanities Research and Indigenous Studies of the North in Yakutsk. During all field studies, interviews were conducted face-to-face, translated, and transcribed (from Russian to English or from Sakha to English).

This article uses the information gathered during the four aforementioned fieldworks, which were funded by different projects and therefore had different research questions. In this sense, being able to conduct another fieldwork in 2020—as initially planned—would have allowed us to: obtain more specific information related to local interpretations of resilience, as well as the salience (or not) of this concept among local residents. It would have also allowed us to unveil relevant and unseen aspects that could influence how SSNs can enhance (or diminish) resilience locally. Being able to conduct longer ethnographic fieldwork would have allowed us to obtain a deeper understanding of indigenous cosmologies—and consequently, more site-specific information about the sharing culture and relationality in Tiksi and Bykovsky. In this sense, it is possible to conclude that this research could be enriched with more qualitative information regarding local cosmology, which can expand the overall ontological understanding of other issues of local relevance that we might have involuntarily overlooked. Additionally, we consider that exploring power dynamics, gender issues, and underlying tensions through the thorough analysis of our interviews is invaluable, however, this exceeded the scope of this article.

2.4 Analytical strategy

For this paper, interview transcripts were thematically coded using preassigned and emerging codes in Atlas.ti. Field diaries and notes from interactions with key informants were re-read, and relevant excerpts were isolated when thematically and geographically (Tiksi and Bykovsky) aligned with the codes used in the interviews. For this research, we employed a hybrid coding approach: initially, we prioritized the use of an inductive and reflexive approach since we aimed at developing a flexible research design that allowed us to delve into issues related to “meaning,” but also to inform us about social representations, experiences, perception and attributions. The inductive logic provided us with enough flexibility and openness to identify new complexities and interrelationships relevant to our case studies (Gallart, 1992). As a result, it was possible to obtain rich qualitative information about many topics, including SSNs. The most recent and last stage of coding was deductive-oriented and was guided by Wardekker’s resilience framework. As a result of the numerous coding stages, we managed to extract three higher-order themes that helped us understand the types of SSNs as experienced in the Republic of Sakha: material, economic and symbolic.

Coding interviews with Atlas.ti allowed us to structure the gathered information thematically and progress toward an analytical interpretation. Using this specific software facilitated coding sentences or paragraphs, creating code groups as well as schematic representations that visually reflect the existing relations between the aforementioned elements. The main challenge at this stage was selecting the most suitable words for each code to accurately capture the ideas expressed by respondents. Conscious efforts were made to minimize the influence of our own preconceptions. To preserve the original meaning and intent of local residents’ statements, we worked with the Russian transcriptions of the interviews, identifying the exact words used by interviewees and their closest English translations (according to our local partners). Each code was created with the intention to reflect—as faithfully as possible—the action, specific example or topic that was being addressed by our responders. Some codes were not directly liked to climate change nor permafrost thawing but provided rich information regarding the general context in which these processes occur and are mentally constructed by local inhabitants. This included topics such as the nostalgia feeling associated to the Soviet era, or the future perspectives for northern settlements, among others.

The resulting list of codes included both gerunds (reflecting ongoing processes) and static concepts. These codes helped reveal key relationships between concepts, processes, and the different societal sectors. Many paragraphs contained multiple codes simultaneously, reflecting the complexity and interconnectedness of processes linked to permafrost and climate in these settlements. In some cases, codes were reworded to enhance the relevance and accuracy of the analysis.

A preliminary (initial scoping) analysis of the interviews revealed that people’s utterances on environmental and climate-related changes were strongly influenced by their personal background (e.g., Indigenous vs. non-Indigenous identity), profession (e.g., traditional activities vs. administrative jobs), and gender (with men spending more time engaged in traditional activities and women more involved in domestic tasks). For instance, residents practicing traditional activities were typically those who spent extended periods in the tundra, enabling them to observe changes more easily and in greater detail. This initial scoping highlighted close connections between the following codes: “traditional activities,” “well-being,” “traditional food,”4 “share and support network,” “low salaries,” “high prices,” “changes in animals,” “climate change,” “black food,” and “mutual support.”

The coding process also demonstrated that SSNs in the Republic of Sakha extend beyond food production and distribution; they are discursively linked to the broader concept of mutual support. According to local perspectives, this philosophy of life—deeply rooted in the North—is shaped by the region’s harsh climatic conditions and remoteness. Many interviewees emphasized that survival in this environment depends on mutual assistance.

For this research, we did not set an exact number of stakeholders that had to be attained. Instead, we prioritized achieving the theoretical saturation as this would provide a greater replication and overall reliability. Finding different categories of stakeholders in each settlement made it possible to explore their shared points of view as well as potential differences between them. By doing so repeatedly, theoretical saturation was eventually attained. Representative stakeholders were sought out to interview in order to analyze the core topics of each of the four fieldworks, including permafrost thaw and climate change. New patterns were identified after analyzing the answers of each group of stakeholders, and preliminary conclusions were formulated.

We structured our corpora and the utterances identified during coding along three key themes: (a) SSNs and black food; (b) SSNs in terms of economic transfers; (c) SSNs as immaterial forms of sharing. The presentation of our results follows this structure.

3 Results

The first section (3.1) presents how food-centered SSNs manifest themselves in the respondents’ narratives, and how these utterances are closely associated to the observed environmental and climatic changes. The next section (3.2) examines how socio-economic challenges identified by our respondents relate to SSNs, more specifically through transfer payments. Finally, the last section of the results (3.3) presents how, despite the environmental and economic challenges, respondents express their choice to remain in their communities. It furthers shows how SSNs do play in shaping what locals consider legitimate and desirable for their future at the local level.

3.1 Black-food-based share and support networks in a rapidly changing world

Fish and meat are the base of the Yakutian diet as is often known by locals as “black food”5 (Argounova-Low, 2009).

“As we say in Yakutian: “Do we have our black food?—We do! So what else is needed?” That’s it. As you have the black food—you are alive”—so to say. You are replete” (INTERVIEW 29 QUOTE 65-18 E).6

Residents closely associate these with support networks and their living environment. Within the two settlements, respondents refer to the “environment” as a multidimensional concept that includes the interactions between climate, permafrost, flora, fauna and landscape. Each of these elements are described as in constant interaction with each other, leading to various feedback loops. These elements must thus be interpreted in relation to each other. Both climate change and permafrost thaw were salient concepts to locals—mostly as intertwined drivers of changes in practices associated to black food harvesting.

“Regarding this issue [podledka]7—yes. If you compare it with old times, with the seventies-eighties, now autumn fishing starts later. In the end of October, it used to freeze in the end of September. There is such change—yes (…) The fish always comes to rivers in September. In the end of September or October—it varies. Sometimes, it happens that the river ices on the 25th October. But before the ice was already forming in the end of September, and on the 1st October people were already fishing. Now, even on October 10th, you cannot put the nets, because the ice is too thin. It’s warm—you cannot fish, and during this moment you miss the time of catch (…) It is a danger: every year, people disappear on snowmobiles because they are not careful. Young guys… Some weren’t found. Young people, who don’t know, they rush right away. I never risk, I drive upstream. There was an opportunity, I barely remained alive—it happened five times to me.” (INTERVIEW 22 QUOTE 7-4 P)

Similarly, when conversing about the ongoing changes that they observe, respondents rapidly link them to traditional activities and to those who practice them. These activities, and those practicing them, play a key role since they constitute the mean through which they obtain and distribute traditional food (mainly meat and fish, but also mushrooms, berries, herbs, etc) among residents from different settlements in the Republic of Sakha. Moreover, traditional activities also allow interviewees to live in alignment with their traditions and worldviews, enhancing their well-being.

“Fish is not only the basis of the salary. It is the basis of well-being. It is for food and other things.” (INTERVIEW 29 QUOTE 69-13 E)

“If there is no fish, then… No fish (we cannot catch it)—we cannot live without it. If there is no reindeer… No reindeer—we cannot live without it. We eat reindeer meat every day. Fish … In winter, stroganina is also eaten every day. But in overall, all meals are with fish and meat.” (INTERVIEW 2 QUOTE 122-2 S)

People practicing such activities are strongly reliant on: (1) Spending time in nature under specific conditions (e.g., fishermen need stable ice to practice “podledka,” stable permafrost is required for safe reindeer migrations); (2) traditional knowledge (e.g., interpreting weather patterns before moving on the ice); (3) mutual share and support at a community and family level (e.g., city dwellers send money to their northern relatives to buy bullets for hunting).

As an example of the extent of such principles, many interviewees mentioned that during the Second World War, the large proportion of the population of Churapchinsky District (in Central Yakutia) was resettled in the Bulunsky District because of droughts and consequent starvation. They arrived to the region to work on state fish farms which were highly demanded to cope with the food crisis. During this episode, locals supported them and taught them how to live in the area:

“These types of relations are the specific to the north. Yes, because the distances are so big here. We cannot live without mutual support. For example, the displaced people from Churapchinsky district (when there was a massive resettlement). They mostly died at the time when they were sailing. And when they arrived here, all of them were … supported by locals. Everyone supported, they all lived. Locals taught them everything and everything was fine.” (INTERVIEW 2 QUOTE 246-1 V).

Furthermore, SSNs as they appear in our interview corpus are rooted in the principles of solidarity and reciprocity. These implicit, kin-based, connections allow relatives and friends living in different settlements of the Republic of Sakha to support each other with both material (e.g., food, materials for hunting and fishing, etc.) and non-material (e.g., administrative procedures, helping students to enter university, emotional support when students migrate to urban areas) favors. The particularity is that they do not strictly rely on previous contributions but instead is a culturally rooted form of mutual aid that is based on voluntarily taking care and supporting each other with what each member of the community can provide. In other words, SSNs inform us about the local manifestations of relationality, as conceived and experienced within the Republic of Sakha.

“Life in the village is like this: calm and even. In fact, all people support each other. Because they are isolated from everything (…) These are the ones … [mumbling] Human qualities are very much appreciated. Helping each other. Because residents’ lives are directly dependent on natural conditions.” (INTERVIEW 2 QUOTE 6-1 A)

“We go fishing and treat each other, yes, we share it.” (INTERVIEW 24 QUOTE 31-7 IK K)

“You know what? Our people live in the old good times. We help each other. We support newcomers and treat them well. We can just give it [meat] to them. We will not sell it (…) Yes, this is a kind of tradition (…) All people provide to each other.” (INTERVIEW 29 QUOTE 72-1F)

Narratives from Tiksi and Bykovsky suggest that two major levels of support networks exist in the Republic of Sakha: SSN between people living in villages and settlements and SSNs between people living in cities and villages/settlements.

SSNs between people living in villages and settlements: residents living in settlements from the same or different districts/regions share, barter or sell their traditional products to each other. For instance, reindeer herders from Namy (situated on the river) and Naiba (on the coast) sell their meat to residents from Tiksi and Bykovsky. The fish caught in Bykovsky is sent to other settlements from the Bulunsky District, including Tiksi.

A woman living in Bykovsky highlighted the importance of being able to rely on her brother who provides her and the rest of the women in her household with fish. This is according to her the only secure and accessible way to obtain fish. Some other neighbors treat her with meat, albeit in smaller proportions. This allows her to sharply reduce her food expenses.

Black food (meat and fish) is the base of the respondents’ traditional diet, but other products are also important such as different varieties of berries (including lingonberries, blueberries and cloudberries), mushrooms and herbs which are gathered from nature. Those who do not have relatives engaged in traditional activities can buy black food from villagers through informal trade networks interacting on Whatsapp groups. This is a financially more convenient option than buying these products at the shops. In this sense, people mainly buy fruits, vegetables, milk and other basic household products in local shops. Even if they do not know anyone in the village, they can request a stranger to sell them or share some black food (Doloisio, 2022). Even newcomers can manage to enter into the informal barter exchanges with locals. The former ones often bring furniture or machinery, while locals can provide with valuable products like fish.

Maintaining a strict control on what, from where and the quantity of products they buy, exchange and receive is essential to preserve the fragile balance of the fragile household’s budget.

SSNs between people living in cities and villages/settlements: these relationships inform us about the traditional food supply in the Republic of Sakha. Yakutsk is the biggest urban center in this region. This type of network shapes what Argounova-Low (2007) described as the “close relatives and outsiders” relationship.

Calling on their kin and friends is essential for residents from northern villages who decide to migrate to urban centers like Yakutsk to attend university or find better jobs. Some rural dwellers send their children to live with their relatives in Yakutsk where they continue their studies. In exchange, they send different products (potatoes, fish, meat, berries, etc.) from their villages and settlements. Similarly, when they go gathering or hunting, people apply this “reciprocity principle” and counter gift nature as a demonstration of gratitude. This form of support also extends to administrative structures such as the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North of the Republic of Sakha. They provide official support to indigenous students who want to enter university. This is essential for families who send their children to Yakutsk from remote areas since the cultural shock and contrasting lifestyles can be overwhelming. Having a support network in the new place of residence can alleviate the psychological stress that young students undergo upon arrival. Another important form of support to rural relatives is doing their administrative paperwork in Yakutsk, thus preventing them from having to travel to the capital city.

Furthermore, food obtained from traditional activities in northern settlements are shared with relatives living in bigger urban centers. This is particularly relevant since buying fish and meat in urban supermarkets is very expensive. In this context, urban dwellers rely on their rural relatives to access traditional food. Additionally, fish, eggs, meat, milk, butter and cream are central in sustaining the culture. Special ceremonies (such as weddings and anniversaries) always include these products and are perceived as an indicator of wealth and well-being (Argounova-Low, 2007).

SSN under stress: most residents agreed with the following changes as direct threats to local food-based SSNs: changes in species distribution and migration patterns, unstable permafrost affects reindeer herds, difficulty in maintaining ice-cellars, unstable ice conditions for ice-fishing, increasing accidents among hunters due to overflow ice (or naled8), and finally the lack of interest of the younger generations for traditional activities.

Respondents pointed out that changing fish migration routes will lead to modifications in the migration of ringed seals (Pusa hispida) and bears (Ursus maritimus). Respondents also mentioned that new species of animals are now arriving to the North, such as sables, hares and ravens (Corvus corax). These ecological niche shifts are associated to changes in climate and the environment.

“Changes. New animals have appeared. This is a sable, a hare. About 15 years ago they were not here. People could not even imagine that there would be such animals (…) I think, it is due to climate change. Summer is warmer and winter is colder. They still somehow influence these changes.” (INTERVIEW 27 QUOTE 6-1 Y)

The arrival of new species of animals, especially those with fur like hares or sables, are perceived as potential new commercial opportunities if hunted and traded, and therefore, as a potential new income for northern residents. These animals could also become food. However, the arrival of new predators such as polar bears represent a threat to hunters, fishermen and gatherers who long periods of time in the nature.

One of the biggest concerns—especially for fishermen from Bykovsky—is the sharp reduction in the amount and size of fish caught in recent years. Several explanations and theories for this phenomenon were proposed by residents: brackish water distribution, changes in water salinity, wind influence, later river ice formation, or even oil and gas exploration on the Laptev sea. It is important to highlight that in the North, having access to fish exceeds the merely commercial interest and also enhance residents’ overall wellbeing (please refer to quote INTERVIEW 29 QUOTE 69–13 E above).

Local inhabitants only fish in internal waters (rivers, streams, lakes, islands in the Lena Delta). They mainly rely on a small variety of whitefish such as omul (Coregonus migratorius), muksun (Coregonus muksun), chir (Salvelinus alpinus), nelma (Stedonus nelma), Siberian vendace (Coregonus sardinella) and whitefish (Coregonus pidschian). Omul has the highest commercial value in the region. Only the Kholkhoz Arktika9 from Bykovsky has fishing grounds along the coast. Small boat brigades use annual plans to define the quotas of fish that they can catch to be able to continue using the specific ground they have been attributed by authorities.

The corpus indicates that fish spawning areas might have moved northwards since the inflow of freshwater from the Lena River entering the Laptev Delta area has increased. Respondents also mentioned that the increase of freshwater is a result of accelerated coastal permafrost thaw. Furthermore, interviewees mentioned that the scientific research conducted in the area suggested that fish are now moving deeper into the sea because the brackish water where they normally live is also being pushed deeper into the sea. In the past, brackish water used to be closer to the coast of Bykovsky, where locals have their fishing grounds are.

“As for the fishing, the fish “went further into the sea”—they say. Before, the ichthyologists said that the water of Lena went too far in the sea, and the fish followed it. But if you would go there—it’s all the border zone. When you go around 10 kilometers away from here. Even less. The border guard doesn’t allow fishing beyond those last islands (you can see these islands, right there). That’s why you cannot fish. Those waters belong to the Federation. The fish are following the fresh water. The white fish (Omul, Muksun)” (INTERVIEW 28 QUOTE 8-4 S).

A local fisherman pointed out that plankton and other small forms of biota are migrating deeper into the sea. Fish follows the aforementioned and consequently move deeper as well. The arrival of big mammals such as whales and belugas who feed on fish could also lead to a decrease on fish availability, according to some residents.

If brackish waters continue flowing deeper into the sea and exceed the 20-mile zone (legally known as “internal waters” where fishermen are allowed to fish), locals will be forced to move deeper into the sea to catch fish—a significant change involving many challenges such as change in fishing vessel and gears, need for stock assessment and change in the regulations pertaining to the border area.

According to residents, the lack of stability in soil conditions can severely affect some traditional activities such as reindeer herding. Reindeers follow seasonal migration routes trying to find the best pastures to feed themselves. According to herders, permafrost thaw creates more swamps in their pastures. As a result, reindeers can fall and get injured. This might lead to a sharp increase in the amount of dead animals, which is perceived as a financial upheaval for herders. More mosquitos due to warmer temperatures also impact negatively reindeer herds. Sharp sudden changes in weather conditions can also produce thick layers of ice-crust, causing reindeers to hurt their hoofs when they try to get the moss from under the ice. According to locals, this could also lead to starvation if animals do not manage to reach the pastures. A local man who worked within the department of agriculture mentioned that in 2017 a large number of horses died of exhaustion: due to the ice crust, they could not dig out the forage with their hoofs and passed away.

Ice-cellars are essential in northern residents’ lives. They are underground caves that are built below the frozen ground. They work as natural community refrigerators where locals store meat and fish that are obtained during the fishing/hunting seasons. This allows them to have access to black food throughout the rest of the year. They can include multiple rooms and storeys and can be owned by families or organizations (such as fishing farms). In Bykokvsy, the Artel “Kholkhoz” has a commercial one while residents have smaller versions of these in their houses. Fishing and hunting farms use them to keep their products frozen until the summer navigation period beings and a reefer ship picks up the tons of fish/meat before distributing them to distant cities such as Yakutsk or Moscow. These structures allow northern fishing farms to provide urban shops and supermarkets with traditional food. But this is also relevant at a family level: those relatives who practice traditional activities in the North send black food to their relatives living in Yakutsk or other settlements.

Ice-cellars require specific and regular maintenance: they must be iced, aired and cleaned. This delays the degradation of the surface and the underground structure and avoids the growth of microorganisms inside.

Increasing air and permafrost temperatures are now diminishing ice-cellars’ stability. This represents a threat for food security in the Republic of Sakha since their products can get rotten more easily, but also exerts additional pressure on northern traditional lifestyle and on the commercial activities. Therefore, residents now have to dig deeper to make sure that the temperature will remain low enough not to rot their food. As for farms, the rapid thawing of their ice-cellars means that black food can be now stored in optimal conditions for shorter periods of time and require more time and work to maintain them, or even new knowledge.

“The second ice-cellar of Raipo fell. Everything is falling. It is the influence…The warm is coming. The collective farm made its own ice-cellar and they are taking care of it, but everything can fall at any time.” (INTERVIEW 29 QUOTE 28-10 F)

Interviewees mentioned that it is now taking longer for rivers and lakes to get fully frozen up and this was identified as a tangible threat to traditional activities, and more specifically to northern residents who practice “podledka.”10 This refers to winter-fishing from underneath the ice which is followed by immediately freezing the fish. When ice is not fully frozen, it can lead to severe accidents for fishermen. Local residents have experienced several dangerous episodes related to incomplete frozen ice (please also refer to quote referenced as INTERVIEW 22 quote 7–4 P above):

“Autumn has become much longer. It is warm until September. It starts to be cold in October. The sea starts freezing. “Shuga” appears only in October. It used to appear in the end of September when the motor boat arrived. We had “shuga” already by this time. September is getting warmer and warmer now, that is good.” (INTERVIEW 25 QUOTE 8-1 K)

Locals use “shuga” (a thin floating layer of ice that appears before the surface water freezes completely) to know when the best and safest moment is to fish. They mentioned that in the past, “shuga” used to appear in the end of September or first days of October. This has now changed and it only appears in mid-October or even in November. This leads to a misalignment between the moment in which fishermen can step on solid ice and the moment of the year when the largest amount of fish migrates upstream to spawn under the ice. Autumn remains the most important season of the year for catching fish due to their natural migration cycles. A few species of fish can also be found in the river in wintertime.

One man living in Tiksi added that some fish, like Siberian Vendace (Coregonus sardinella), may be used as an indicator to predict if the freeze-up will be earlier or later that year since this fish prefers lower water temperatures. If a local goes fishing and catches one of these, the community will know that the water temperature is low and will therefore freeze soon.

During the winter, after the ice surface cracks, new holes (known as “treshina11” in Russian) appear on the ground surface. As a result, water overflows or sits on top of the ice and freezes. These masses of layered ice formed on the ground, the river or the sea resulting from the overflow events is what locals call “naled.”12 Such layers become scratched when driving or stepping its surface and it is particularly dangerous because being white and flat is it difficult to identify. This has become an additional threat for hunters and fishermen who circulate in the tundra for their traditional activities.

“These overflow ice (naled) are dangerous for our hunters. They can fall into naled, get wet and freeze to death. That’s because there is some water inside. “(INTERVIEW 29 QUOTE 55-17 Sh)

Traditional activities are considered by many northern residents as at risk believe they might soon disappear if the current trend is not reversed. In indigenous rural villages in the Bulunsky District young people show an increasing disinterest in living traditionally and often abandon traditional activities such as reindeer herding, fishing and hunting. Moreover, these activities are practiced in harsh conditions: they are physically demanding; they require people to remain isolated from family for days or weeks because they do not have internet in the tundra; low remuneration; among others. Climate change and permafrost thaw render these activities even harder.

“[…] Here in our place, in the North, the conditions for traditional activities have been disappearing for people in recent years. For us, for example, for Evenkis. Like, traditional fishing, reindeer herding, wild reindeer herding, hunting for fur animals. As for today, domestic reindeer herding is already on the decline. For example, back in the days, we had more than 40 thousand reindeers in the district. In the 1970s, around 1977 (…) But in my opinion, the federal government and our region are paying insufficient attention to the preservation of traditional activities. They do initiate measures but they are insufficient, too small, minimal (…) The number of domestic reindeer is declining. It means that the number of local people conducting these activities is also decreasing. They are also dying out, if there is no activity, people cannot adapt to lifestyle like in Tiksi, they are decreasing in numbers.” (INTERVIEW 17 QUOTE 2-6 T)

All of these changes point towards increasing difficulties to practice traditional activities and therefore to access black food (traditional food), which is the base of SSN in the Republic of Sakha. Yet SSNs may also take the form of transfer payments by individuals. Networked economic flows may be central to dynamics of solidarity.

3.2 Transfer-payment in the face of the socio-economic challenges

Addressing changes in climate and the environment often led to reflecting about their current living conditions in the North. Residents mentioned the deteriorating condition of buildings, the lack of clubs and entertainment facilities as well as the availability and prices of goods and supplies:

“We come here and have to pay high prices. You can only buy one or two things. We cannot afford more.” (INTERVIEW 29 QUOTE 67-10 E)

“We have just very poor supplying here. […] lack of activity clubs/sections, and some kind of entertainment facilities.” (INTERVIEW 15 QUOTE 26-1 A)

These features were identified as elements that restrain development possibilities and diminish livability in settlements like Tiksi and Bykovsky. The liberalization of prices after the dissolution of the Soviet Union lead to a sharp increase of goods and supplies’ prices in remote Arctic settlements and continues to impact local residents nowadays. High prices negatively impact purchasing power.

High prices exert additional pressure on low-income families and newcomers. A resident from Bykovsky mentioned that some newcomers cannot overcome the devastating consequences of it and eventually return to their places of origin (see interview 21 quote 16–5 KK).

“Well, it’s hard here. The prices are very expensive here: for food, for flight tickets. For example, for us, for a multi-child family, it is very difficult to travel, like, for vacation or somewhere else.” (INTERVIEW 12 QUOTE 5-2 D)

Low salaries and high prices are two sides of the same coin: locals agreed that salaries are not high enough to guarantee a good quality of life in these settlements. The owner of a family farm affirmed that their monthly income as a family does not allow them to save any money:

“It is not enough. Everything is expensive here. [For example], our machinery, the snowmobiles cost millions. Those Yamaha snowmobiles cost a million robles, the cheapest one costs 800 thousand, even 900 thousand rubles with the delivery. Food and gasoline are expensive. 200 thousand rubles are spent on gasoline for one season. In addition, we pay taxes: for the farm, for the licenses, for the weapons. The Northern residents, don’t pay transport tax for cars and snowmobiles since this year. Earlier, we were and since this year we do not pay the transport tax. Almost everything is spent. What we earn, all this money is spent on survival.” (INTERVIEW 22 QUOTE 27-2 Pe)

Elders from these settlements also mentioned that they send money to their grandsons and granddaughters to support their studies. The high prices of gasoline needed for cars and snowmobiles adds extra pressure on families’ budgets. A native of Tiksi who previously lived in Bykovsky said:

“The salary is very small. Administrative workers have a small salary. Meat is expensive here. Fish we can take on our own but still you have to buy the fish from people who caught it (…) I rent a small flat in Tiksi. I pay 15 000 rubles every month, plus utility bills cost 18.000. Basically I have to pay everything what I have earned. [I earn] 38 000. I spend everything. I have no savings.” (INTERVIEW 23 QUOTE 27-7 B)

In such context, saving money becomes impossible. Their expenses include basic food products, housing expenses, loans, mortgages and special equipment needed to live in the North—such as snowmobiles. Other residents also showed concern regarding the increasing inflation, increasing the financial tension in the region.

Although these difficulties are shared by people living in both settlements, the economic profile of Tiksi and Bykovsky differ, leading to local specificities: people living in Tiksi strongly rely on administrative jobs, which provide them with fixed salaries. Whereas in Bykovsky, fishermen obtain money after they sell the fish. In the Republic of Sakha, residents traditionally provide financial support to their relatives when it is possible. This helps counteract high prices and low salaries. This is particularly relevant among inhabitants from the Bulunsky District: elder people want to stay there—among other reasons—because pensions are higher in the North and this allows them to financially support their relatives living in order places. Such is the case of a woman from Tiksi who helps her son to pay his studies:

“I live here because my son is a graduate student at Leningrad University. Therefore, I support him financially (…) My salary here is (I don’t know whether I can say this or not) 50 thousand. Then, when the lunch break is also on Saturday, I give lessons at the Tiksi versatile lyceum. I am a teacher of biology, chemistry, and I also conduct geography there. This is a dozen. I’m also a pensioner. This is 20 thousand. But my son doesn’t work. And, despite the fact that he is a graduate student with a budget (he has a stipend), I have to help him, because I pay a mortgage for an apartment, I pay loans. I help, give him life (…) But I want to tell you that we have enough for food, for clothes, but, for example, there is already not enough for repairs. Here it is very expensive. And there it is expensive. We cannot make [money] for repairs anywhere. We have more or less there, but here the apartment is in a decadent state, to be honest. No household appliances. And all this is expensive.” (INTERVIEW 31 QUOTE 21-3 E)

These difficulties may partially be alleviated through transfers from those who have left to those who have stayed, or from those who live in other settlements to those living in Tiksi/Bykovsky. Our respondents mentioned several situations where urban dwellers reciprocated through other forms of support: financial (buying bullets for hunting, or equipment for fishing); administrative (filling out forms, applying for state support); education (guidance for northern relatives who want to pursue upper studies in the capital city). Although such dynamics seem to be rooted on material exchanges, they also have deeper connotations within the social configuration and identity processes: these implicit relationships existing between residents from different regions and settlements reinforce—according to them—their feeling of security and well-being.

While environmental and social changes indicate that food-based SSNs may be under threat (section 3.1), section 3.2 indicates that economic-based SSNs seem to simultaneously support individuals that have left Tiksi and Bykovsky and support those who have chosen to stay—this despite often disadvantageous economic conditions.

The ability to support family members that have left, or that have stayed, is presented as a rationale for staying—not for leaving. This shows that respondents express other rationale to stay in arctic communities. The question of staying or leaving is frequently addressed as part of a more symbolic network of shared representations.

3.3 To leave or not to leave –the sharing of attachment and nostalgia

The interviews that we conducted—as well as the fieldwork notes—further show that the experiences—or at least what is remembered of this experience—of northern residents during the Soviet days sways the perception of their current quality of life, the accelerated changes and the prospects that they consider for themselves and their settlements. According to these observations, the socio-economic prosperity and high quality of life (reflected as daily flights from Tiksi-Moscow, wide variety of products, receiving all sorts of cargos in the seaport, cheap subsidized prices), came to an end with the collapse of the Soviet centrally planned economy.

In such a context, the “sharing” of SSNs takes a new form: that of a symbolic shared relationship to time gone by. Such a symbolic sharing may shape the options that residents deem desirable for their futures in terms of mobility. Central to this sharing are the nostalgia and melancholia associated to northern settlements as they once were. Indeed, these feelings emerged from locals’ narratives. More specifically, residents from Tiksi and Bykovsky showed signs of melancholia towards the prosperous days that they lived during the Soviet Union. The word “nostalgia”13 was used to describe the way they felt about what this region used to be during Soviet times, but no longer is. This strong reliance and attachment to what once was reveals that the current living conditions and experienced changes are interpreted through the lenses of their shared past experiences.

“Earlier in Soviet times, there was generally beauty. We had everything. And now, look, everything is somehow not very. And there were a lot of ships, and now there is not a single ship.” (INTERVIEW 13 QUOTE 12 SP)

“Of course! Absolutely. This is a very important factor—nostalgia, memories of youth. An excellent standard of living in younger years compared to what it is now. Of course.” (INTERVIEW 15 QUOTE 28-6 T)

“Earlier in Soviet times everything was good. Provisions came from Moscow and from St. Petersburg, Leningrad. First priority. The food was very good. Clothes, everything. The seaport worked well. Then, during perestroika, in the 90s, when everything came to ruin and the seaport was closed. People began to leave, experts left.” (INTERVIEW 34 QUOTE 9 EF)

Elderlies’ reluctance to leave their settlements is also connected to the nature of the place:

“No, no [I’m not willing to move]. My wife says: “let’s go, let’s move to Yakutsk.” And I say: “You know, let’s get divorced and you leave. And I can stay here alone.” [jokes, laughs]. Because my father, my grandfather, were born here. Although my mother is not from here. She was [born] near Yakutsk. There [they] have trees—I cannot stand these trees. [laughs] Tundra is dearer. [There is] Space, visibility—you can see far!” (INTERVIEW 5 QUOTE 42-2 S)

“It’s no fun to be old (laughs). You can only go to your children, where else would you go? If the health is allowing it—you should live in your birthplace till the end. We are both from here: me and my wife. My wife is also from here; she is a native dweller too. We cannot separate from our homeland.” (INTERVIEW 28 QUOTE 38-1 S)

The specificities of these lands and climate appeared as important elements that contribute to develop emotional ties and material practices for locals. In this context, cold is perceived as a constitutive element of their culture and worldview and often appears as an element that underpins locals’ decision to stay. Therefore, warmer temperatures in Tiksi and Bykovsky could lead to irreversible identity and psychological consequences for their population.

“And always, when I go on vacation, I am always in a hurry to come back. Because it’s cool and good here (laughs). When I go to my grandmother’s in Ukraine on vacations—it’s a nightmare! There is such a heat! Horrrible!” (INTERVIEW 15 QUOTE 16-3 L)

Such a pluri-dimensional connection to the birthplace is also expressed by young students from Tiksi living in Yakutsk. They express missing their settlement and their willingness to return after finishing their studies. Their utterance resonates with that of the elderly:

“Tiksi is my favorite home, I love it so much. If I could, I want to come back to Tiksi because I feel a responsibility for the whole land. That is why I want to work for my home, for the people who live there. Weather is not so cold as in Yakutsk. There is very strong wind, 15 m/s. It is very difficult because people leave Tiksi. It is the economic situation…it’s very difficult to find good jobs with high salaries and people don’t know what to do. It’s dangerous because people dream. Infrastructure is really bad, internet (laughs) even worse! By the way, I think that in the future it will be better because the Arctic is an area of interest for the government. It will take time.” (INTERVIEW 16 QUOTE 1 (Yakutsk, 2019))

This shared attachment, leads to the expression of intergenerational expectations:

“Before, we used to have a port here. We had an international port. Now everything is closed, so we have nothing. There is no good. If it was restored, there could be an improvement (…) Yes, I want them [teenagers] to at least raise their homeland” (our emphasis, INTERVIEW 13 QUOTE 77 SP)

Sharing meaningful memories, a common past, and the attachment to their places can reinforce the notion of purpose among northern residents and therefore, guide and foster community action. Nostalgia towards the past lifestyle that they once had in the Bulunsky District also seems to influence the future projections for the settlement and for local residents’ lives. Being part of such symbolic networks as an extent of the SSNs described in sections 3.1 and 3.2, can increase the sense of belonging, reinforce the sense of unity within the community, and enhance their sense of security associated to knowing that they can rely on each other to overcome hurdles.

3.4 Organizing these results analytically

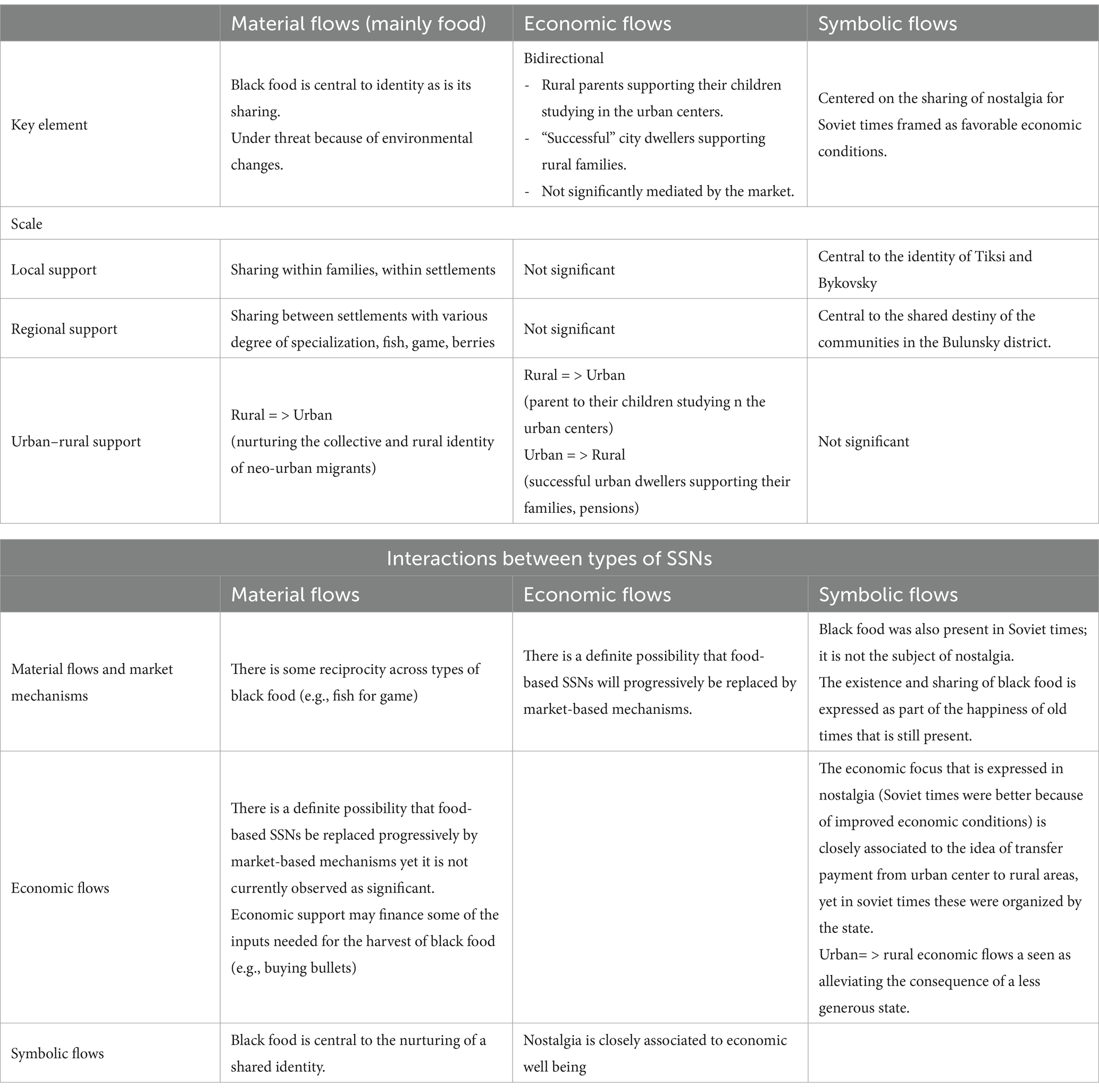

In sections 3.1 to 3.3 we followed the narrative streams that we found in our corpus. SSNs, as described by our respondents, are constituted by hybrid flows of material, economic and symbolic resources that are somehow discursively intertwined. This hybridity does not necessarily lend itself to clear cut categorizations without betraying the utterance of our respondents. Not only are the narrated flows hybrids, but they also connect individuals and families locally, regionally, and between rural and urban areas. In Table 1 below we present these results in a more synthetic way to better inform the discussion that will follow.

Accordingly, we will organize the discussion along the cells in Table 1 that relate to community level resilience by grouping these under three thematic areas:

1. SSNs as a source of strength, yet fragilized by current changes,

2. Symbolic network, in the form of shared identity and nostalgia,

3. Integrating these results in order to reflect on the resilience framing of SSNs.

4 Discussion

4.1 SSNs may be framed as a source of resilience, yet they are currently threatened by accelerated environmental changes

Our findings indicate that food-based SSNs remain central to sustaining life in the Russian Arctic. As observed in other Arctic settings (e.g., Berman, 2021; Konnov et al., 2022), the ability to harvest resources or practice traditional herding remains a fundamental livelihood strategy in Tiksi and Bykovsky—one that serves as a source of strength in normal times and as a crucial coping mechanism during periods of heightened socio-economic adversity. However, our results also suggest that food-based SSNs are increasingly vulnerable to the ongoing impacts of climate change and permafrost thaw.

The effects of climate change on Siberian ecosystems and food systems are now widely acknowledged and well-documented in academic circles (e.g., García Molinos et al., 2024; Gartler et al., 2025). Our corpus indicates that residents of Tiksi and Bykovsky are acutely aware of these environmental changes (see also Doloisio and Vanderlinden, 2020; Doloisio, 2024). Furthermore, discussions about environmental changes are often intertwined with discussions of “black food” and vice versa.

Black food-based SSNs thus interact with community capacities in an equivocal way: they serve as a source of strength, agency, and well-being in the face of rapid change—a form of resilience, one might say—yet they are also at risk of becoming inoperative or less effective due to these same changes. This highlights the need to recognize a potential threshold beyond which traditional activities, and strong reliance on them, may shift from being a mechanism that enhances resilience to a factor increasing exposure and vulnerability to climate change. In this sense, more research should be conducted to understand at what point and under what specific conditions would the boundaries of relationality and the sharing culture within the Republic of Sakha—as conceived and experienced today—could reach their tipping point, forcing a deep social, cultural and economic reconfiguration.

Reducing black food solely to its nutritional value would be a mistake (see Sandré et al., 2024, for an example). In the Republic of Sakha, food-based SSNs are deeply intertwined with indigenous spiritual worldviews. For instance, among the Evenki of the Republic of Sakha, Buga refers not only to the biophysical environment but also to the spirits inhabiting it and a central spiritual entity that governs environmental relations and human interactions (Lavrillier, 2005). Human-environment interactions are structured around the principles of gifting and counter-gifting, along with a set of prohibitions. Failing to respect these obligations can lead to severe consequences, as Buga may cease offering resources to humans in exchange. Conversely, successful hunting or herding requires an offering to Buga in return. Among local hunters, it is well understood that one must never take too much from the environment. Similarly, natural products such as meat and fish must be shared within the community (Lavrillier, 2013).

A related practice in the region known as nimat, is a Tungusic traditional custom that refers to the “distribution of equal shares of the spoils of the hunt among the entire local community” (Forsyth, 1989, p. 76) and thus establishes social relations with other people (Ksenofontov, 2018). According to Bereznitsky et al. (1997), this practice applies to hunters, fishermen, and gatherers and extends not only to families within the same settlement but also to those in neighboring settlements. These widely observed yet implicit rules illustrate how sharing, gifting, and counter-gifting form a complex network of interactions, where material exchanges are merely a reflection of deep spiritual foundations. The material and non-material dimensions of these networks are inseparable.

Our results also indicate that networks based on economic transfers are seldom mentioned. When they do appear, they are most often in reference to the support that younger out-migrants receive from older residents of Tiksi or Bykovsky. This suggests that, in the face of environmental change, economic-based SSNs might play a relatively minor role compared to food-based networks.

The information gathered, however, does not allow us to theorize about other underlying issues that could be “hidden.” For instance, how accelerated changes might reinforce internal power dynamics (either between settlements/regions or within each of them), or how could a sharp and sustained reduction in access to black food could reshape local and regional relationality, as well as sharing trends. We do not have information to theorize about potential new sources of food in face of accelerated climatic changes: if reindeer meat was increasingly difficult to obtain, would people be keen to consume new alternative animal species like hares? Could changes in climate lead to the arrival of new fish species (that have not appeared until now), that could replace the traditional ones which are becoming scarce? Additionally, since the beginning of the war with Ukraine, obtaining specific information about local/regional economies, new laws, changes in migration patterns, etc. has become difficult to access from our particular vantage point, located in the West.

4.2 Shared representations of the past as a source of resilience fostering networks

Arctic community members consider a wide range of factors when assessing the livability of their settlements. In the literature, economic considerations tend to dominate, including local public goods provision (Howe and Huskey, 2022), cost of living and livelihood opportunities (Berman and Wang-Cendejas, 2024), and educational opportunities (Rozanova-Smith, 2021). However, our corpus suggests that respondents from northern settlements such as Bykovsky and Tiksi also express nostalgia tied to non-material aspects they deem important—shared feelings about past experiences, as well as symbolic representations of their climate and environment.

Soviet nostalgia is particularly salient among older residents, especially in Tiksi, who refuse to leave their settlements. For them, the Soviet era represents a distinct period in national history, serving as a point of comparison for their current living conditions. It also evokes specific experiences shared by those who lived in the North during the Soviet Union and remain there today. Narratives from these residents suggest that prosperity was once measured by the quality of infrastructure, the volume of goods delivered to the North, employment levels, transportation facilities, low prices for goods and services, and the number of ships passing through the port. The high costs associated with remoteness and the short periods of open navigation were offset by subsidies from the Russian budget for Northern shipping (Heleniak, 1999). Their attachment to the Soviet Union as a reference point underscores their frustration with today’s lower material quality of life and the many challenges they face. This frustration is often accompanied by a strong desire to remain in their settlements, to “rebuild” them, and to reclaim a sense of prosperity reminiscent of the past.

Nostalgia, and the invocation of modern soviet times as a reference point, is not totally surprising. Scholars have been identifying nostalgia as a concept central to early and late modernity (see Tannock, 1995; Pickering and Keightley, 2006). Furthermore, considering the changes that Siberian Arctic communities are going though, it is worth noting that nostalgia is seen as a “bridge between a number of large-scale societal/social forces […] and individual and/or collective ways of feeling, responding to and coping with experiences that are sometimes stressful or critical […]. In this way, nostalgia links the macro (e.g., social changes and cultural transformations) with the meso and micro experiences of individuals and groups” (Becker et al., 2024). Another fundamental dimension of nostalgia is its relationship to identity continuity/discontinuity in changing times. Central to this are the effects of nostalgia on the collectiveness and the continuity of identity (see Davis, 1979 for a foundational text, Wilson, 2005, for a more textured analysis) and social connectedness (Sedikides and Wildschut, 2019). In these lines of thought, we interpret nostalgia as a local source of collective agency—through networked symbols and reference points. Shared past experiences, perceived as positive and meaningful, now serve as motivation for collective action. Nostalgia fosters optimism and hope for a better future, encouraging residents to actively and collectively seek ways to sustain their communities despite the adversities they face. One could argue that the opposite situation should be considered: if the ongoing and rapid political, environmental or climatic changes worsened the situation at a regional and local scale, the specific principles that currently shape the functioning of SSNs fostered by nostalgia might be forced to change, leading to a social and cultural fragmentation. However, this negative evolution does not appear to manifest itself in our corpus.

Boym (2014, p. 18), whose focus is significantly soviet and post-soviet, considers that “nostalgia can be a poetic creation, an individual mechanism of survival, a countercultural practice, a poison, or a cure.” Our narratives from Tiksi and Bykovsky reveal a strong sense of nostalgia. Boym considers that “nostalgia, like globalization, exists in the plural.” In this sense, we deem important to highlight subtle differences among residents. The experiences from elder people who lived there during the Soviet Union and still do, find that past that no longer exists as a point of reference for their present and future and are often accompanied by a strong discursive desire to see their settlements to be developed again “like in the old times.” Whereas the young students who were originally from Tiksi but lived and studied in Yakutsk seemed to embrace a different form of nostalgia that is strongly shaped by the feelings, life experiences and stories as told by their relatives. Following the author’s concepts of restorative and reflective nostalgia, it is possible to infer that:

(a) Being unable to return to their settlements as they were in the past does not allude to a literal physical or geographical displacement, but rather to the radical changes in time, forms and socio-economic dynamics;

(b) While this can be experienced as a tragedy in some cases, it can also become an enabling force. Both restorative and reflective forms of nostalgia—as conceived by Boym (2014)—could be found in our narratives, leading to positive outcomes, but expressed in different ways. For instance, if residents from Tiksi and Bykovsky achieved a state of acceptance about that temporal irreversibility and start finding appreciation or love towards ruins since they are now perceived as “living” parts of that past that evoke cherished memories, common experiences and histories. In this sense, deteriorated buildings could be reinterpreted: they are no longer structures to be restored, but they become part of the landscape they live in where personal and collective past memories find a tangible way to remain alive today. If we consider the narratives of those residents who firmly stated that they want to see their settlements rebuilt like in the past, we could interpret them as forms of restorative nostalgia. In this case, those feelings would—or should, according to them—be accompanied by coordinated action. For example, by trying to promote that young people who left to pursue their studies in Yakutsk or other regions come back to help in the development of the settlements. In both cases, the past “will act by inserting itself into a present sensation from which it borrows the vitality” (Bergson, 1988). However, such vitality might adopt different shapes depending on which of these two forms of nostalgia prevail.

These narratives demonstrate that the present and future of settlements like Tiksi and Bykovsky cannot be fully understood without considering the symbolic historical legacy of the Soviet Union. Rapid permafrost degradation and climate change, combined with fragile socio-economic conditions, present new challenges for both local and regional authorities, as well as for northern communities themselves. However, this moment of transition could also serve as an opportunity to create new spaces for dialogue—both within coastal communities and between neighboring settlements—where residents—who have so much in common, including representations of an idealized past—can voice their major concerns, priorities, and aspirations.

4.3 What does SSNs tell us on resilience as an interpretative lens?

The work that we present here stems from a quite prevalent idea that resilience in the Arctic needs to be explored, interpreted, fostered (see introduction, Arctic Council, 2016, Belmont Forum, 2019). Yet a growing body of literature distances itself from resilience. Considering our results we will explore how these relate to three closely connected streams of decolonial resilience critique: (a) resilience-based approaches as failing to address the deeper colonial and neoliberal logics that produce ecological destruction in the first place (e.g., Young, 2021); (b) resilience discourse as a universalizing Eurocentric device (e.g., Amo-Agyemang, 2021); resilience as a device that cements time-tried expectations that indigenous peoples always adapt (e.g., Lindroth and Sinevaara-Niskanen, 2019).

Considering the issue of the root cause of disturbances—climate change—as being ignored, black food-based SSNs inform us precisely on the fact that local structures, such as food harvesting practices, are intimately associated—to some extent—to climate and ecological stability. A dominant subject of conversation when envisioning SSNs is precisely the manifestations of changes that are beyond the control of locals in Tiksi and Bykovsky. These changes are threatening their ability to lead the networked life they desire and are threatening a central source of multiscale collective and individual strength. Therefore, by analyzing SSNs, through a resilience lens, we may be in a position to shed light on ecological destructions and the degraded conditions these impose on local communities.

Considering the resilience lens as a universalizing Eurocentric device, our results are not very informative. This may in part be explained by the prevalence of western modernity in settlements of the Russian Arctic such as Tiksi and Bykovsky, which foundations are closely associated to the very modern Eurocentric universalizing Soviet state. Material conditions are central to the narratives that we collected, as are the promises of modernity consubstantial to the expressions of nostalgia that we identified. Thus, a resilience lens, as a western centric “scientization” of communities’ ability to fare in the face of severe changes, may very well be received positively within such a worldview (e.g., Nikulkina et al., 2020).

Finally, considering the framing of local communities as ontologically able to adapt, our results indicate that this is precisely not the case and that rapid environmental changes may very well lead to potentially irreversible threshold beyond which black food will become less and less accessible, and/or where exchanges may become increasingly mediated by the market.

Our results thus point to the potential of engaging a conversation between theoretical discourses on resilience and local practices. Such a cross-framing, local practices framed by resilience, and resilience framed by local practice, has the potential to simultaneously assess critically local practices, and contribute to a pluriversal, decolonized approach to resilience.

5 Conclusion