- 1Institute of Development Research and Development Policy, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany

- 2Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany

Climate change adaptation aims to reduce vulnerability to climate impacts across various sectors. Current adaptation efforts appear inadequate as they do not address deep-rooted structural barriers such as inequality, exclusion, and weak governance. This limitation hinders the long-term sustainability of these adaptation efforts. This systematic review draws on Johan Galtung’s concept of positive peace, which encompasses equity, justice, and inclusion. It seeks to explore how integrating these principles into adaptation efforts might enhance their effectiveness and sufficiency. The article employed a systematic literature review method based on the PRISMA approach to evaluate scholarly and policy-focused research on the intersection of positive peace and climate adaptation. Several databases were utilized, including Scopus and Web of Science. Searches used key terms such as ‘climate adaptation’ and ‘successful.’ The inclusion criteria emphasized studies addressing adaptation beyond mere technical solutions and those considering justice, governance, and long-term sustainability. Galtung’s peace framework served as an interpretive lens. The findings from this study indicate that while positive peace concepts are not always explicitly utilized in adaptation literature, core elements—such as distributive, procedural, and recognitional justice—often appear as critical to successful outcomes. Additionally, climate adaptation practices that intentionally incorporate these principles tend to be more resilient, community-driven, and responsive to climate risks. A grounded demonstration of this finding is illustrated with a case from the Solomon Islands, showing how integrating peacebuilding approaches into community-based adaptation may enhance both resilience and social cohesion. Consequently, the paper proposes a conceptual framework linking positive peace dimensions with the criteria of adaptation success and adequacy. Integrating positive peace into climate adaptation may offer a pathway for addressing systemic barriers, especially in non-conflict settings. Furthermore, it could redefine adaptation from reactive risk management to proactive justice-centered planning. However, more research is necessary, as beyond this systematic review and a few case studies, empirical evidence remains scarce. Adaptation activities are often undocumented or assessed without justice metrics. Although empirical testing is needed, the study underscores that integrating positive peace may help deliver more sustainable outcomes in highly vulnerable regions.

1 Introduction

Climate Change Adaptation (CCA) is crucial for addressing and reducing sector vulnerabilities to climate change. However, when adaptation strategies fail to incorporate processes that prevent negative cycles or conflict with local development realities, negative spillovers and maladaptation are likely to occur (Schapendonk et al., 2023). Currently, climate adaptation does not adequately address social issues. More specifically, the relationship between climate adaptation and peacebuilding is understudied. Discussions on the connection between environmental change and social problems trace back to classical Greece (Homer-Dixon, 1991). In contemporary times, debates on the link between both subjects have persisted since the mid-2000s (Busby, 2021).

In the 1950s, various interpretations of peace emerged following the events of the Second World War. Galtung’s binary interpretation of peace as either ‘negative’ or ‘positive’ received the greatest academic acclaim at that time. According to Galtung, negative peace refers to the absence of conflict, while positive peace involves social justice (Galtung, 1967; Galtung, 1969). Unlike negative peace, which has clear parameters for measuring its presence in a society, the criteria for assessing positive peace, as posited by Galtung, remain ambiguous. To Galtung, positive peace meant the ‘absence of structural violence, or structural limitations on the fulfilment of human potential’ (Scholten, 2020), ‘social justice’ and ‘equitable distribution of power and resources’ (Simangan et al., 2021).

This lack of clarity concerning the concept has led scholars in Peace and Conflict Studies to focus predominantly on the negative peace dimension, often overemphasizing conflicts as a starting point for peace-related studies. The lack of conceptual clarity regarding positive peace may have partly contributed to why the relationship between positive peace and the environment has been understudied in recent times (Simangan et al., 2022). The concept of environmental peacebuilding, which examines the connection between the environment and peacebuilding, has not addressed this gap. Environmental peacebuilding gained popularity in direct response to the excessive focus on the potential role of the environment in conflicts or violence (Ide et al., 2021). It aims to explore how the environment and environmental actions can serve as tools for peacebuilding following violent conflicts. However, it neglects issues of power structures and underlying tensions, which also limit the effectiveness of such environmental actions in the absence of conflicts.

The impact of policy gaps and limited research on this topic is acutely felt in smaller countries in the Pacific region, particularly those affected by sea level rise. In this review, the Solomon Islands was chosen because repeated extreme weather events and rising seas threaten food security, freshwater availability, and settlement in atolls (Leal Filho et al., 2020). Strong indications of community-based resource management practices in the region provide valuable insights into how positive peace dimensions can enhance adaptation (Basel et al., 2020). At a Pacific Islands Forum, a representative from Papua New Guinea remarked that the effects of climate change on certain regions, such as Pacific Island Countries, parallel the threats from guns and bombs faced by larger nations (Kratiuk et al., 2023). The insidious nature of climate change exacerbates tensions, which may not always lead to violent conflict. It has the potential to destabilize entire nation-states and restrict fundamental human rights. For instance, migration from sinking states affected by climate change contributes to the breakdown of the ethno-social bonds between peoples and the gradual loss of their collective identity (Chechi, 2014). In the Global South, Small Island Developing States (SIDS), Least Developed Countries, and Developing Countries lack the resources needed to adapt to climate change effectively and are hindered by societal issues.

Simangan et al. (2022) found that Least Developed Countries, in particular, perform well in terms of negative peace but not in terms of positive peace. Consequently, addressing positive peace concerns in climate change adaptation is vital to tackling issues that existing policy and research overlook. Positive peace is an umbrella term that encompasses all forms of aspirations held by people. Incorporating positive peace into environmental strategies is crucial for accommodating the unique needs and aspirations of different communities while ensuring sustainability in societal conditions. In this review, we draw on Galtung (1967, 1969) work and subsequent elaborations (Simangan et al., 2021; Scholten, 2020) to highlight three guiding criteria: procedural justice (inclusive decision-making and participation), distributive justice (fair allocation of resources and benefits), and recognitional justice (acknowledgement of diverse identities and knowledge systems). These criteria provide analytical lenses for examining how CCA measures incorporate aspects of positive peace. By using these dimensions as guiding categories, the review can systematically assess whether CCA demonstrates success and adequacy.

Positive peace is a progressive process that individuals can utilize to meet their needs in accordance with their value systems (Barnett, 2007). Galtung, who first proposed the concept, viewed the local environment as central to the unfolding of peace in a spatial context. He recognized a connection between positive peace and the local environment. Galtung advocated for the institutionalization of behavioral norms centered around peace within the local context (Amadei, 2020). Such behavioral patterns and norms, once institutionalized, become stable, valued, and recurring (Simangan et al., 2021). In this study, a case study is presented to illustrate how peace-centered norms, when integrated into local climate change adaptation efforts, may create successful and adequate CCA.

Certain negative social norms may be re-enacted during climate change adaptation due to their institutionalization in local settings. Their re-enactment limits the effectiveness of climate adaptation actions. Therefore, it is important to address these limitations in CCA by emphasizing peace-centered norms. Even if global actors aggressively reduce emissions through mitigation, global temperatures are still expected to rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius (Nguyen et al., 2023), making negative environmental changes inevitable. Climate adaptation refers to the human responses undertaken to reduce harm or exploit opportunities arising from climate impacts. To be successful and adequate, it must go beyond mere technical fixes and ensure that human needs and values are met despite the anticipated adverse changes in the external environment (Gabatbat and Santander, 2020).

Critics of Galtung’s positive peace view it as too normative for effective problem-solving. However, its normative features make it a valuable lens through which we can properly examine the principles that can enhance the sustainability of environmental actions (Simangan et al., 2023). A central case study of adaptation in Solomon Islands is used to support this position. The research gap that the review article aims to fill is the unclear role and practical use of positive peace in climate adaptation. In other words, the central question of the article is: how might principles of positive peace assist in achieving more successful and adequate climate change adaptation? For clarity, in this review, the terms ‘success’ and ‘adequacy’ are used based on climate adaptation literature—both gray and academic. According to Hamilton and Lubell (2019), ‘success’ in CCA is defined as process-based adaptation outcomes like access to information, procedural fairness, and cooperation, which strengthen the resilience and legitimacy of CCA. The IPCC (2022) also highlights the need for CCA to embed fair and desirable processes to be legitimate. Thus, it defined successful CCA as those that are ‘effective, feasible, and just’ in their processes. Success in CCA requires multiscale processes that connect various levels of knowledge and values (Granberg et al., 2019).

While success in CCA has been extensively explored in the literature (Barnett and O’Neill, 2013), the concept of adequacy is less frequently examined. However, the use of ‘adequacy’ in CCA in this review directly stems from its application by the IPCC AR6 Working Group II on Adaptation. Adequacy in CCA refers to outcome-based measures considered sufficient to avoid dangerous or unacceptable climate risks (IPCC, 2022, 2023). That is, adequacy is measured by the sufficiency of outcomes rather than the quality of the process. Adequacy in CCA is understood in terms of effectiveness, equity, and long-term sustainability. CCA is deemed adequate when it addresses immediate risks proportionally, distributes benefits fairly, and remains viable under future scenarios (IPCC, 2022, 2023). ‘Success’ and ‘adequacy’ guide both the literature review process and the interpretation of findings.

Section 1 introduces the primary questions this review aims to address, defines the key terminology, and highlights the importance of this study, which builds on existing research. Section 2 describes the systematic review process used, including the inclusion and exclusion criteria for selecting literature. 102 studies were included in this review, focusing on cases from the Global South. Based on these studies, Section 3 presents findings that integrate positive peace into CCA and highlights existing gaps. The section then offers a central case study illustrating how the integration of positive peace into CCA has led to successful and effective adaptation. Additionally, it provides a conceptual framework that translates positive peace into dimensions of justice. This section demonstrates how these dimensions can be applied across all sectors of adaptation, ensuring successful and effective adaptation according to IPCC criteria. Section 4 reexamines CCA using Millar’s (2021) trans-scalar peace system and addresses the operational limitations in Galtung’s original conceptualization of positive peace using the framework from the study. The section concludes by assessing the policy implications of these findings for current approaches to CCA in highly climate-vulnerable regions of the Global South. Section 5 outlines directions for future research, while Section 6 concludes the discussion.

2 Methods and limitations

2.1 Data selection: PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses)

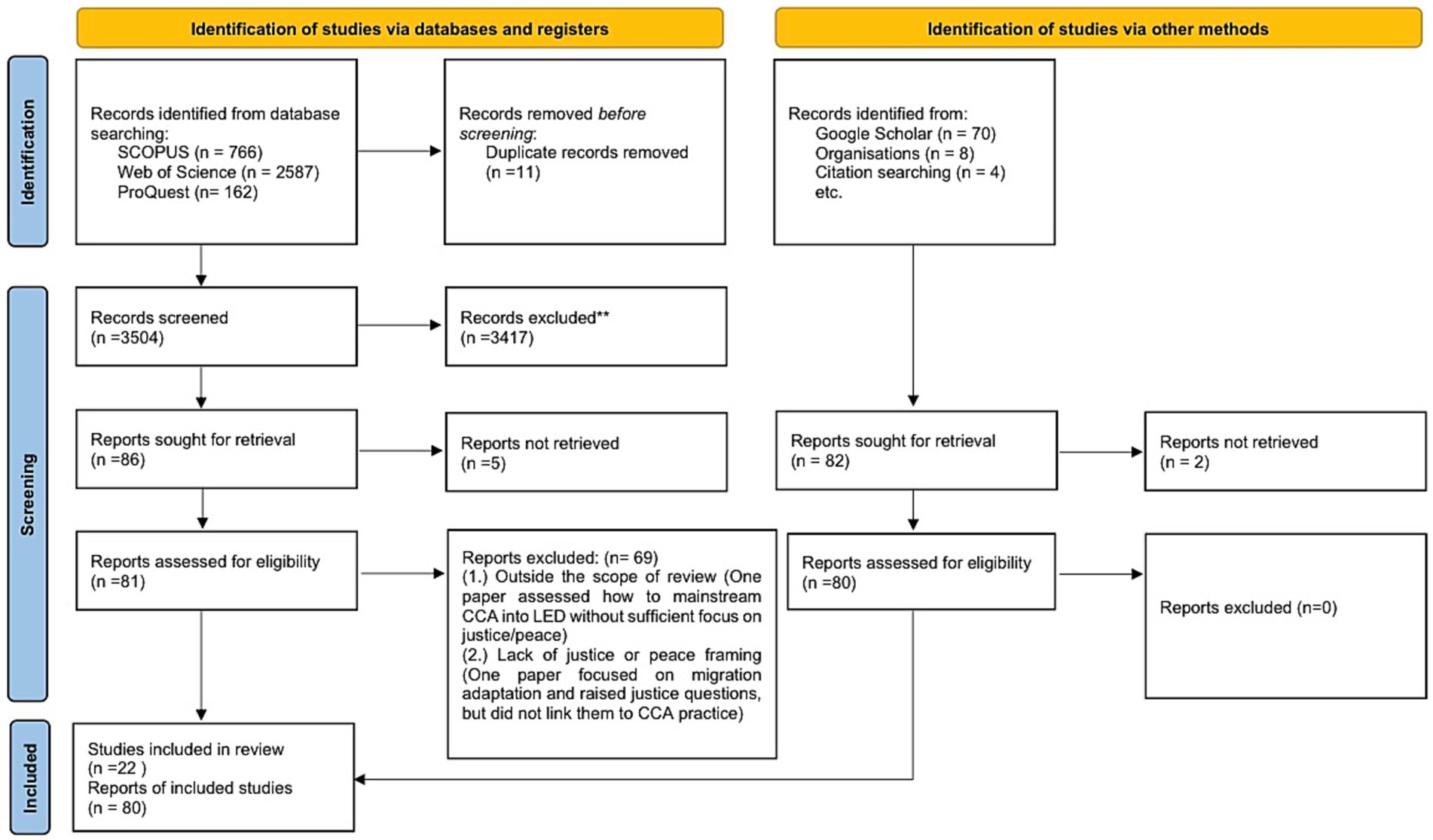

PRISMA is used in this review because it provides comprehensive and transparent reporting of the review process, allowing readers to assess the trustworthiness of the findings (Page et al., 2021). The review process is illustrated in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). We conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed and gray literature. The search was conducted between February and April 2024, with an update in January 2025, before submission. The review focused on literature from these dates, starting with the release of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) in 2014 and the publication of the AR6 Synthesis Report in 2023. The IPCC AR5 report defined adaptation as including ‘avoid harm.’ It systematically highlighted adaptation limits, governance, and equity, setting a benchmark for adaptation. Conversely, the AR6 report emphasized the importance of avoiding climate risks while integrating justice and equity as essential components of ‘adequate adaptation’. This period encompasses a decade during which the concepts of success and adequacy were analyzed and debated, making it the relevant timeframe for assessing how dimensions of positive peace intersect with CCA.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart showing the literature selection process. (PRISMA, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses; CCA, Climate Change Adaptation; LED, Local Economic Development).

The review was structured with the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, and Study design) framework. The Population was communities in the Global South. The Intervention was the Integration of positive peace dimensions into adaptation measures. The Comparator was an adaptation study with and without explicit reference to justice and peace elements. The Outcomes of the review were evidence of adaptation success (process-based) and adequacy (outcome-based). The Study design involved the use of peer-reviewed studies and authoritative institutional literature published between 2014 and 2023.

The literature search and selection process was limited to specific databases and registers: SCOPUS, ProQuest, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Web of Science provided a multidisciplinary range of high-impact journals that was crucial for the review. SCOPUS offered a wide selection of social science and environmental studies relevant to the study. ProQuest included a small but significant collection of academic literature that was essential to the review. Google Scholar supported a broader investigative and citation search, capturing additional peer-reviewed and policy documents. Using the Boolean search method, an advanced search was conducted on registers, combining key terminologies like adaptation, justice, and peace. The results of the searches, illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1) below, were as follows: SCOPUS (positive AND peace OR social AND justice OR equality AND climate AND adaptation AND successful AND adaptation OR adequate AND adaptation AND PUBYEAR > 2013 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ch”)) = 766), ProQuest (positive peace AND equality AND (social justice) AND successful AND adequate AND (climate adaptation) = 162), Web of Science (((((AB = (positive peace)) OR AB = (equality)) OR AB = (social justice)) AND AB = (climate adaptation)) AND AB = (successful adaptation)) OR AB = (adequate adaptation) = 2,587).

The definitions of ‘success’ and ‘adequacy’ in the Introduction guided the coding and selection of studies. In operationalizing this, studies were relevant where they explicitly or implicitly addressed process-based dimensions of success (like legitimacy, fairness, participation, procedural justice) or outcome-based dimensions of adequacy (like equity, long-term resilience, avoidance of maladaptation) [as defined in IPCC AR6 (2022), Hamilton and Lubell (2019)]. These served as analytical lenses to assess whether adaptation activities demonstrated success and adequacy. All articles that did not engage with these dimensions were excluded at the screening stage.

All the records that we retrieved were imported into EndNote, and duplicate records were removed. The review followed the four PRISMA stages of Identification, Screening, Eligibility, and Inclusion. After identifying the literature, the screening process occured in two stages. First, the titles and abstracts of 3,504 records were assessed by the lead author to determine their relevance to the review. In this stage, 11 duplicates were removed, and 86 articles focusing on adaptation were identified. Also, uncertain cases were jointly discussed with a second reviewer. The second stage involved reviewing the full texts of these 86 records using interpretative judgement based on predefined inclusion criteria. Only 22 texts that included a justice dimension in the adaptation literature were sought for retrieval.

Additionally, other papers, reports, and gray literature (80) were included through investigative research on Google Scholar and citation tracing from reviewed documents. In total, the literature for this review consisted of 102 pieces, including 91 papers, 8 gray literature sources, and 3 book chapters. The primary keywords guiding the literature selection were chosen based on their frequency of use in existing studies, reflecting a common understanding among scholars of their relevance to conceptual clarification. These terms remained consistent throughout the process: for climate change adaptation (climate adaptation, climate change adaptation), for positive peace (positive peace, equality, equity, social justice, participation, power), and for successful and adequate (successful, adequate, effective, just) (Owen, 2020; Matin et al., 2018; Simangan et al., 2021).

Studies were included if they focused on climate change adaptation in the Global South. A minimal number of texts from the Global North that provided some transferable insight were also included. The selected studies focused on social issues related to adaptation, including justice, equity, and community participation. They presented empirical evidence of successful and adequate adaptation, emphasizing positive peace dimensions. The articles chosen were peer-reviewed and generally published in English between 2014 and 2023. Following the inclusion criteria, we managed the bibliographic records of all included studies in EndNote. Here, we used notes and custom keyword fields to tag each study based on whether it included justice and peace-related themes, such as distributive, procedural, and recognitional justice, as well as social cohesion. This tagging process helped with thematic coding and synthesis of the reviewed literature.

Studies were excluded if they solely addressed mitigation or emissions reduction. Additionally, studies focusing on conflict resolution without clear links to climate change or adaptation were excluded. Some studies were not included because they fell outside the Geographic scope of the Global South or did not align with it. Studies viewing environmental actions as just a technical issue or discussing adaptation without referencing justice or peace dimensions were also excluded. Furthermore, non-English studies, commentaries, and non-empirical works were not considered.

One study evaluated how mainstreaming CCA into Local Economic Development (LED) as a distinct concept can enhance better inclusion and justice outcomes. This review emphasizes the CCA process itself and its integration of inclusion. Mainstreaming CCA into LED may foster inclusivity, and the process of mainstreaming may also function as a form of inclusion. The excluded literature did not address such aspects or sufficiently focus on the CCA process (Ahenkan et al., 2021). Another study assessed how migration as a form of adaptation needs to incorporate justice dimensions from a geographic perspective. It raised critical questions but did not specify how justice-based considerations have been or are being enacted in CCA (Baldwin and Fornalé, 2017). Another study that examined the limitations and barriers to CCA in small island states did not discuss how CCA is organized around justice themes for success. While the paper identified social limitations, this was not the main topic of discussion nor explored adequately to justify inclusion in this review (Leal Filho et al., 2021). A paper that addressed adaptation options from both engineering and non-engineering perspectives focused only minimally on the non-engineering aspect and did not correspond with justice themes (Li et al., 2021).

Grey literature was included to highlight adaptation practices that are under-represented in academic journals, in the Global South. Many countries from the Global South are categorized as particularly vulnerable to climate change (IPCC, 2023). These countries often have a post-colonial background and are affected by societal problems and conflicts. Focusing on the Global South aligns with historical dimensions of climate justice themes related to positive peace, which are explored in this paper. Eligible grey sources include those with policy relevance, representing the most up-to-date policy positions on adaptation. Also, the grey literature selected was that which provides globally accepted definitions of ‘success’ and ‘adequacy’, and conceptual benchmarks, such as the IPCC assessments. Also, reports from commissions and community-based studies were included, since they allow for perspectives that peer-reviewed studies do not. The grey sources included were only those that had a transparent methodology and were from recognized institutions, like the UN, IPCC, IMF, and governments.

Grey reports, such as Resurrección et al. (2019), titled ‘Gender-transformative climate change adaptation advancing social equity,’ helped bridge the gap between positive peace and adaptation adequacy, using empirical cases from Asia. The IPCC (2014, 2022, 2023) reports provided conceptual definitions for success and adequacy. Other reports, like Ng Shiu et al. (2024), ‘Perspectives from communities across the Pacific,’ were essential in providing empirical evidence for the connection between cultural identity and adaptation adequacy by gathering community voices on resilience in Pacific Islands. The case studies selected for this review originate from various countries in the Global South, like Kenya, Ghana, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, South Africa, Uganda, the Philippines, and Cambodia. These country case studies were chosen based on their high exposure to climate risks, the availability of peer-reviewed evidence on the justice and participation aspects of adaptation in such places, and their relevance as primarily low- and middle-income settings within the Global South. Country case studies outside the Global South lacking sufficient peer-reviewed evidence on justice and participation aspects of adaptation were excluded from the review.

2.2 Limitations

The review has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the scope of the literature search was restricted to studies published in English between 2014 and 2023. The language and timeframe restrictions may introduce publication bias and underrepresent adaptation research from other regions where fewer studies are indexed in international journals. Second, the inclusion of grey literature was limited to institutional sources, such as the IPCC, the IMF, National Adaptation Plans, and university-based research. This excludes other community-level or practitioner reports that might provide additional perspectives. Third, the illustrative case study of the Solomon Islands was chosen because of its rich documentation and relevance, but is not representative of all SIDS. The findings from the Solomon Islands case study are only illustrative and not generalizable.

Fourth, there are conceptual limitations. Positive peace overlaps with broad notions of justice, which require interpretive judgment when classifying the relevant themes (for example, when distinguishing between procedural justice and participation). To mitigate this, the review prioritized positive peace dimensions (procedural, distributive, and recognitional justice), as guiding categories and related justice components as operational sub-components. Fifth, the evidence base for the contribution of positive peace to successful and adequate CCA is thin. Few empirical studies explicitly link positive peace principles with successful or adequate adaptation outcomes, limiting our ability to make strong causal claims. To address this, we combine systematic evidence with an illustrative case study and identify research gaps. Finally, the focus on the Global South overlooks adaptation in other regions and underscores the need for comparative approaches across different geographies.

3 Results

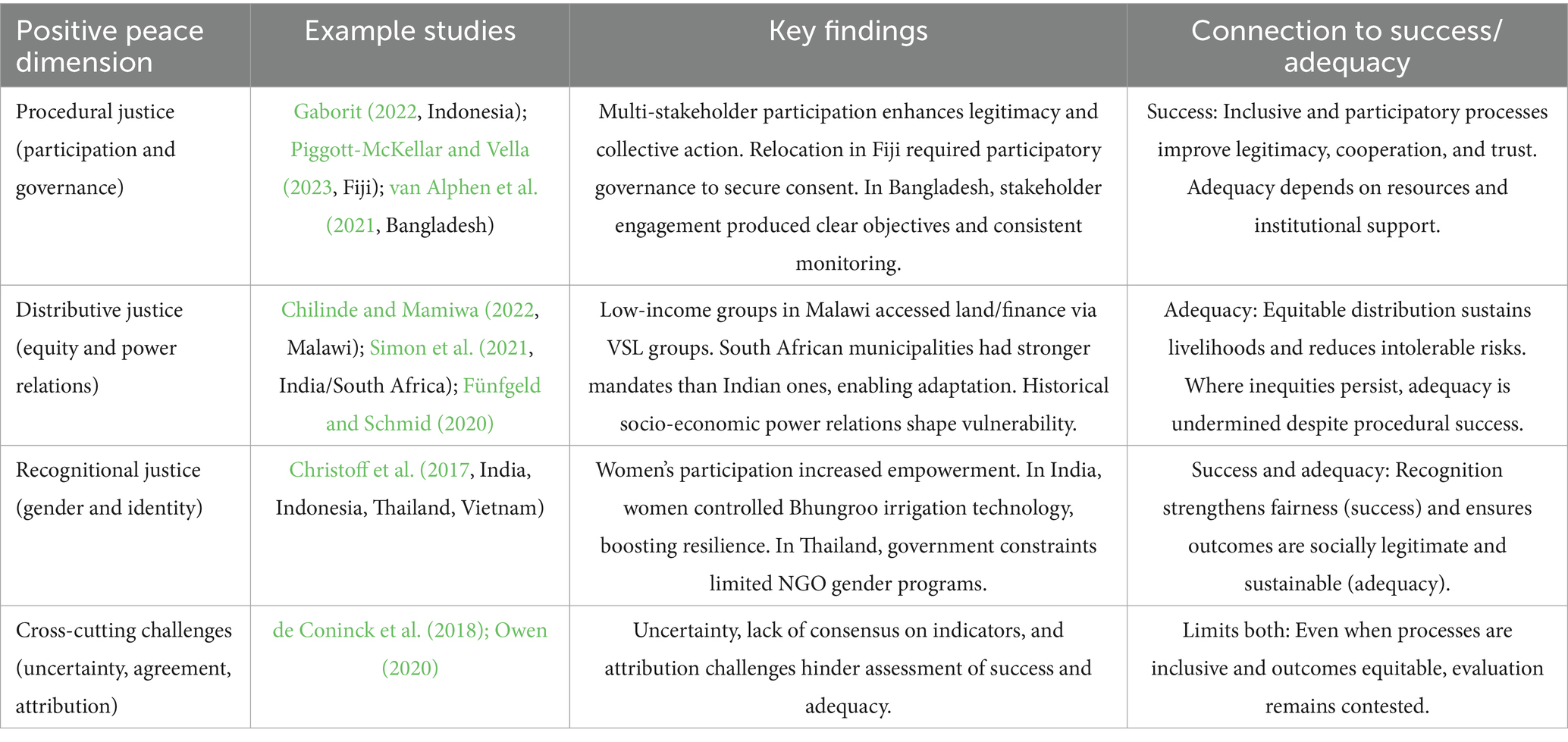

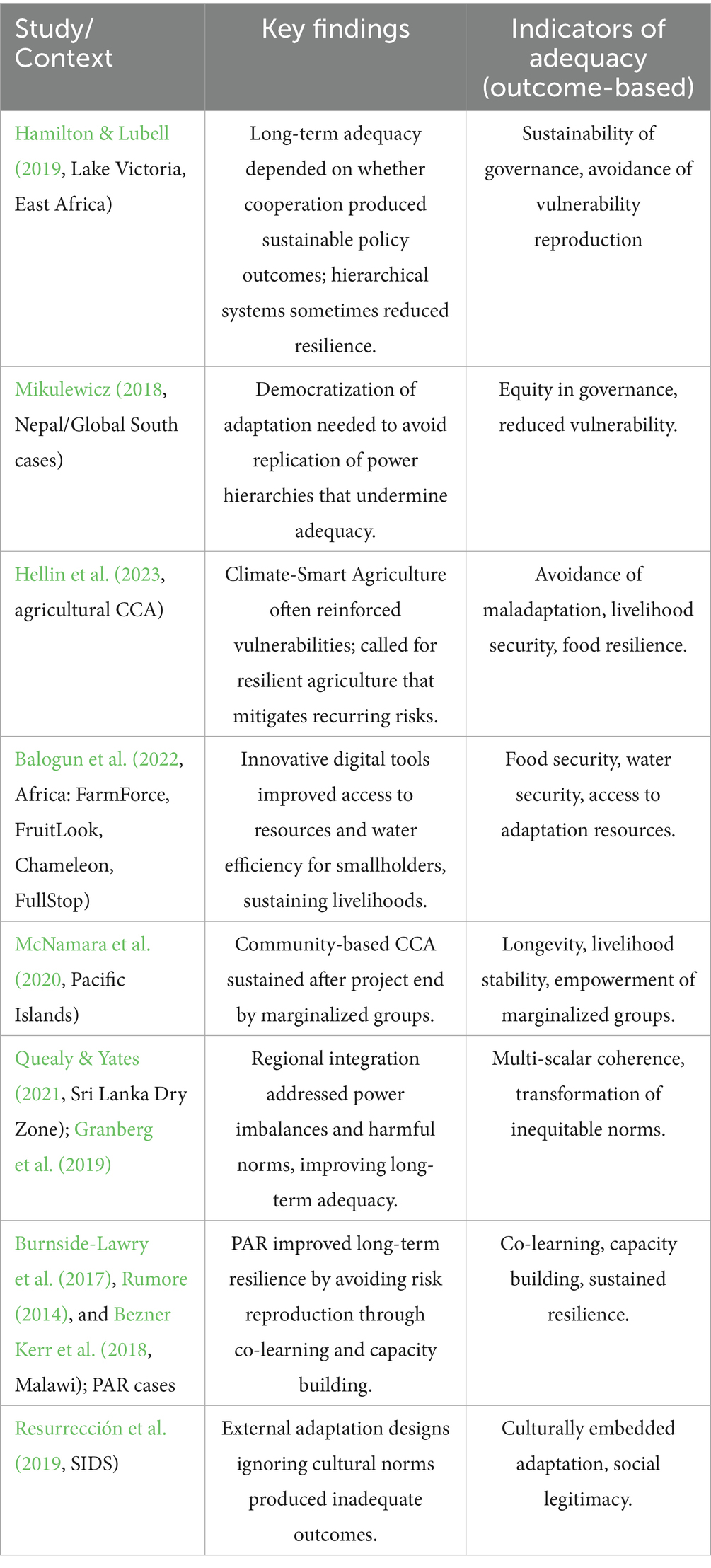

The results compile evidence from 102 studies that met the inclusion criteria. These studies cover Global South countries with a thematic focus on adaptation practices in agriculture, fisheries, urban planning, migration, and community-based adaptation. The section presents findings in five parts: (1) The first part shows how studies align positive peace (procedural, distributive and recognitional justice). Evidence is summarised in Table 1 linking key terms and key studies; (2) The second part shows studies demonstrating that success as a process-based approach is more achieved than adequacy, which is outcome-based, highlighting the value of integrating positive peace to bridge the gap from the literature. Key findings are also summarised in two tables (Tables 2, 3); (3) The gaps in the literature are highlighted to reveal that few studies define success and adequacy explicitly, with evidence of adequacy being scarce, as more studies focus on processes; (4) A case study of adaptation in Solomon Islands is presented to illustrate how positive peace dimensions enhance success and adequacy of Climate Adaptation; (5) A conceptual framework distills results connecting positive peace dimensions with success and adequacy.

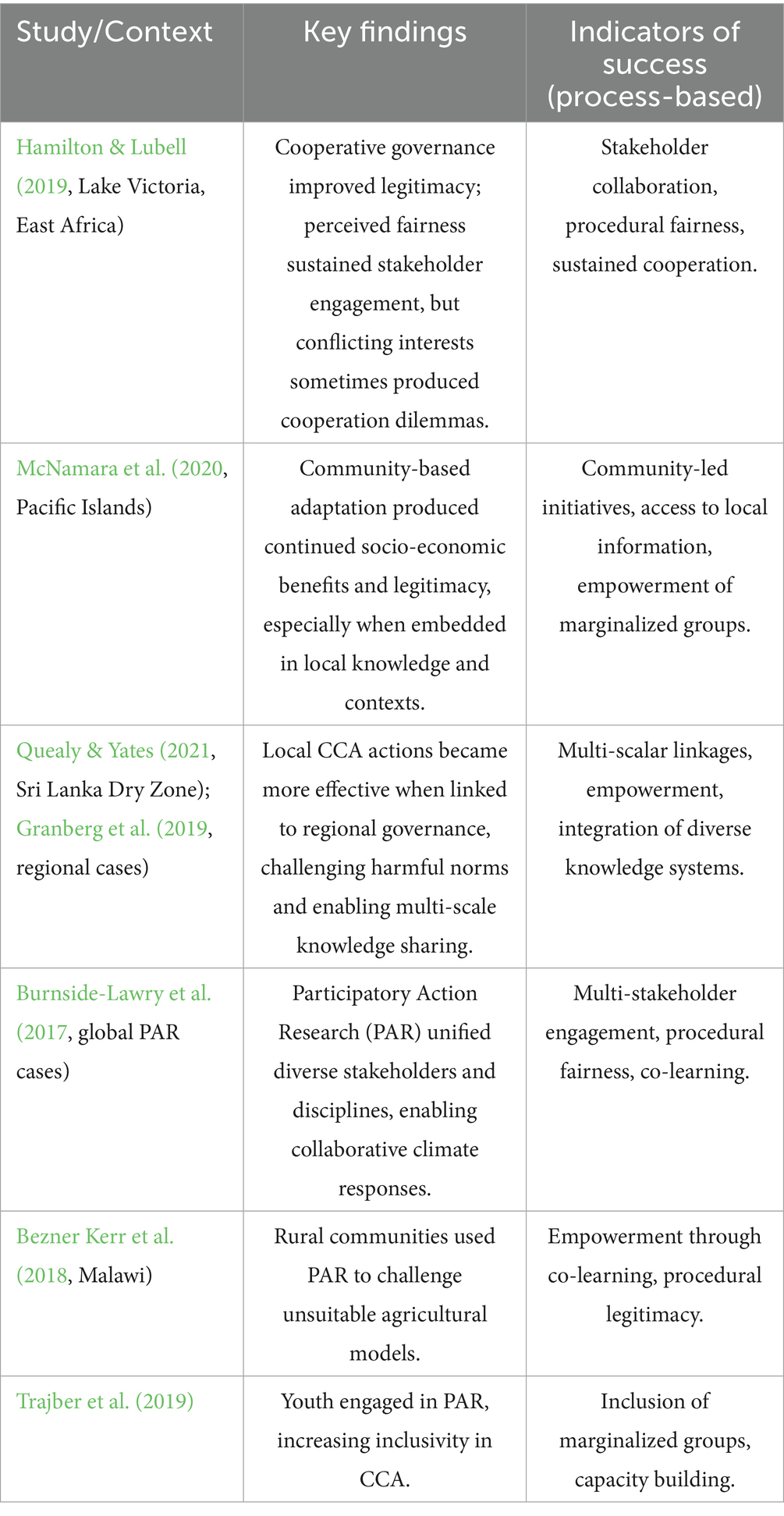

Table 1. Positive peace dimensions observed in climate change adaptation studies and their connection to success and adequacy.

Table 3. Indicators of adequate adaptation (outcome-based or sufficiency-based) in selected studies.

3.1 Positive peace themes in climate adaptation literature

The first step in the results is to identify how the 102 studies engaged with positive peace dimensions. Its core aspects under social justice and equality (procedural, distributive, and recognitional justice) were consistently identified as key factors influencing successful and adequate adaptation outcomes. Social justice involves participation and shared decision-making, engaging all stakeholders, especially marginalized groups. It includes equitable distribution and access to resources, respecting cultural and multiple perspectives, and helping individuals achieve their potential. Moral equality involves recognizing and addressing power imbalances among decision-makers (Matin et al., 2018).

As shown in Table 1, most studies addressed issues of procedural justice, while a smaller number addressed issues of distributive justice, and fewer studies addressed recognitional justice problems. The studies show that equity and participatory governance in the management of resources are sometimes considered synonymous with CCA itself. In a study, Ortega-Cisneros et al. (2021) analyzed South Africa’s fisheries management documents and found that these themes- equity and participatory governance are often integrated in CCA, even where the process is not explicitly labeled as ‘CCA’. Studies also show that equal access to resources and power is a crucial component of CCA processes (de la Torre-Castro et al., 2022). For example, a study conducted in Pakistan showed that access to information using resources such as modern ICT tools was vital for CCA processes (Ali et al., 2021). However, positive peace themes are interconnected, and the presence of one theme alongside the absence of another can influence how CCA operates. A study in Kenya showed that despite having access to information, a lack of access to financial resources hindered effective climate adaptation. Where multiple themes of positive peace exist in CCA, these themes must connect positively for the success and adequacy of climate adaptation (Adekola et al., 2022).

Another study by Nagoda and Nightingale (2017) investigated the interconnected nature of positive peace themes. The authors explored how power relations persist at the village, district, and national levels during CCA programs in Nepal. The study showed that CCA processes do not sufficiently address the needs of marginalized groups and often exclude them. It also revealed that participatory processes in community-based CCA that aim to tackle power relations within multi-scalar CCA can reproduce vulnerabilities. Despite participation, CCA replicates power imbalances and serves merely as a formal affirmation and does not foster the empowerment of marginalized individuals.

Power is a central theme of positive peace in the literature on CCA. Political leaders who hold more power than other stakeholders push their agendas during CCA. As shown in Table 1 below, in Blantyre and Lilongwe, Malawi, land use policies intersect with power, affecting the ability for collective action on adaptation. However, in this specific case study, Chilinde and Mamiwa (2022) show that local participation and access to resources for low-income groups help bridge the inequality gap. Despite different policy approaches to disaster response and land use planning, CCA processes revealed an overlap in players in both areas within Malawi. Disaster response and land use planning involve the same local actors. This means that such people are participating actively in CCA processes and gaining empowerment. Low-income groups that previously could not participate also developed systems to improve their access to resources for CCA. Village Savings and Loans (VSL) groups called Banki Mnkhode were formed to help mostly women from low-income areas pool money for loans as an adaptation measure. NGOs in Malawi also work with low-income groups to promote land rights. All of these networks, both formal and informal, empower the urban poor to leverage power and secure land that would otherwise be inaccessible due to existing power structures (Chilinde and Mamiwa, 2022).

The location of power over CCA processes influences the success and adequacy of CCA. The effect of power dynamics in CCA processes is shown in Table 1 below, in the study by Simon et al. (2021). The study showed that in South Africa, municipalities are responsible for matters such as sanitation and environmental protection. This differs from India, where municipalities are tasked only with sanitation and waste management, excluding environmental protection. Consequently, in India, municipalities and their actors have less capacity to tackle CCA issues (Simon et al., 2021). Another study by Fünfgeld and Schmid (2020) highlighted a critical point: there is also a historical dimension to power in CCA. CCA capacities are linked to historical socio-economic power dynamics. The authors have argued that, as a result of these historical dynamics, for adaptation to be successful, it must include the equitable distribution of social ‘goods,’ which encompass forms of privilege and preference.

Our findings also show that participation is the most prevalent positive peace theme in the literature. It involves multiple stakeholders at various levels (Gaborit, 2022). One study, as shown in Table 1, revealed that strong participatory governance is a crucial recommendation for affected populations seeking to relocate, as an adaptation strategy in coastal communities in Fiji (Piggott-McKellar and Vella, 2023). Another study by van Alphen et al. (2021) highlighted in Table 1 assessed participation in water governance in Bangladesh. The authors noted that participating stakeholders were necessary to establish clear objectives, divide tasks, and consistently monitor adaptation efforts. They observed that the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Principles on Water Governance incorporate stakeholder governance as a key criterion for establishing and achieving water governance objectives as part of CCA. The theme of participation in CCA is not only vertical, it is also horizontal. Climate adaptation spans multiple disciplines, making the inclusion of diverse perspectives through stakeholder participation vital.

In the Global South, participatory networks strive to address moral inequalities by empowering women politically and economically within local communities. As shown in Table 1 below, Christoff et al. (2017) studied case examples from India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Women in India utilized Bhungroo technology to combat gender inequality. Some received training on using the technology for CCA. As the sole controllers of this technology, they began to play an active economic role in their households and local governments. This report, which highlights the success of CCA due to inclusive participation, aligns with other findings from Indonesia and Vietnam. However, in Thailand, where the government wields significant power over NGOs’ activities, it opposes gender mainstreaming objectives aimed at empowering women.

Where CCA integrates positive peace themes, it transcends a technical focus to aim for social outcomes. However, unlike technical CCA, which may use scientific criteria to ensure its objectives are met, it is not always clear that socially based CCA, incorporating positive peace themes, is successful and adequate. Uncertainty, lack of agreement, and attribution are three key inhibitors (de Coninck et al., 2018; Owen, 2020), when assessing the success and adequacy of CCA. Uncertainty means that existing evidence suggests CCA activities often do not succeed. Lack of agreement refers to the lack of consensus on what constitutes the best methods and appropriate indicators for monitoring. Attribution indicates that it is challenging to determine if certain outcomes are specifically linked to specific CCA activities, as adaptation is an ongoing process.

The table below (Table 1) summarizes the various positive peace dimensions observed in CCA studies. It demonstrates their connections to success and adequacy as defined in the introduction. The table indicates that procedural justice promotes process-based success through legitimacy and cooperation. Distributive justice enhances adequacy by shaping fair outcomes, while recognitional justice reinforces fairness and ensures socially legitimate adaptation.

3.2 Success and adequacy in climate change adaptation literature

Building on the patterns above, the second set of results assessed how selected studies conceptualised success and adequacy. Table 2 summarises examples of how particular justice dimensions translate into success or adequacy, or both success and adequacy.

As shown in Table 2, Hamilton and Lubell (2019) note that CCA is successful when stakeholders collaborate to tackle climate challenges through cooperative governance. Actors who see policy systems as unfair due to a lack of procedural justice may withdraw from the system. Conversely, those who perceive the CCA system as fair are more likely to cooperate, which improves its sustainability and adequacy in the long term. Hamilton and Lubell (2019) explore CCA in the Lake Victoria region of East Africa using success indicators. They find that, despite a variety of actors, individuals may still face cooperation dilemmas because of conflicting interests. When CCA is integrated into policy frameworks, existing hierarchies can be reinforced, reducing the resilience of CCA. They note that even with efforts to implement fair new processes or interventions for climate issues, vulnerabilities can still be perpetuated. CCA is only adequate when interventions avoid reinforcing or creating climate vulnerabilities.

A study in the agricultural sector by Hellin et al. (2023) indicates that CSA (Climate Smart Agriculture) initiatives reinforce existing vulnerabilities. In their study, Huyer et al. (2024) also found that CSA solidifies power relations, limiting women’s ability in particular to benefit from it. This has occurred in places like India, East Africa, and West Africa. While climate-smart solutions have not always been successfully implemented in local settings of the Global South, other scholars have noted that climate issues in countries of the Global North, like Australia, require smart solutions approaches. However, it was also noted that collaborative governance is a crucial requirement for planning, managing, and implementing such climate smart initiatives successfully (Frantzeskaki et al., 2022).

In a study, Mikulewicz (2018) suggests that democratizing CCA can help address issues caused by replicating hierarchies and power structures. Some climate smart initiatives now designed to prevent the replication of current hierarchies prioritize social equity. As shown in Table 3, numerous examples of such initiatives emphasizing social equity are currently being implemented in farming practices across Africa. FarmForce, a cloud-based mobile program launched in 2012, aims to improve access to resources for small-scale farmers to adapt to climate change. Another initiative, FruitLook, enhances water use efficiency. Others, like Chameleon and FullStop, are used by irrigation farmers in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique (Balogun et al., 2022). CSA initiatives that are not gender or socially blind, but integrate social equity, tend to be more successful and adequate.

The table below (Table 2) summarizes the findings on successful CCA. A key insight is that existing power asymmetries undermine procedural fairness, as top-down adaptation planning tends to reinforce current vulnerabilities (Mikulewicz, 2018). Conversely, collaboration among communities, governments, and NGOs enhances adaptive capacity, particularly when knowledge co-production is prioritized (Bezner Kerr et al., 2018).

Other studies show that bottom-up responses driven by local actors lead to successful and adequate CCA. Especially bottom-up responses that are community-oriented and aim to tackle climate issues collaboratively. In a study by McNamara et al. (2020), it was shown that these responses have positive socio-economic impacts and demonstrate continued success. Community-based approaches thrive because they incorporate access to local information, skills, and contexts to address climate impacts where they are most severe. Community-based responses align with their contextual applications and achieve their intended objectives. Such interventions are also adequate CCA as they engage marginalized groups who can sustain them after the CCA project concludes. Transferable insights from Global North countries like New Zealand also support the need to integrate local knowledge into CCA It has been noted, for example, that there is potential for nature-based urban adaptation to be successful when linked to indigenous ecological understandings of wellbeing (Mihaere et al., 2024).

However, Quealy and Yates (2021), in another study highlighted in Table 3, have also argued that successful and adequate local CCA actions are those that are linked to the regional level. The authors find that the regional level can address concerns related to power dynamics and challenge the continuation of harmful norms, hierarchies, and vulnerabilities (Granberg et al., 2019). Connecting local actions to cities and regions fosters a multi-scale platform where diverse knowledge and values can be represented. Other studies also posit that successful CCAs must connect multiple stakeholders and unify diverse disciplines within a single system to ensure procedural fairness. According to a study by Burnside-Lawry et al. (2017), Participatory Action Research (PAR) can lead to successful CCA since it brings together multiple stakeholders from different disciplines to help countries effectively respond to climate impacts on both local and global scales, and by integrating various fields. A study PAR has also been deemed an adequate form of CCA action, as it can avoid replicating climate risks through co-learning and by incorporating existing CCA knowledge. As further evidence of its effectiveness, PAR is now recognized as a vital tool for capacity building. Various studies show that it has been used for successful CCA by academics (Rumore, 2014), young people (Trajber et al., 2019), and researchers, and civil society organizations at both local and global levels (Burnside-Lawry et al., 2017). In a study highlighted in Table 3 below, Bezner Kerr et al. (2018) illustrate how co-learning among disciplines supports CCA in Malawi. According to that study, rural communities in Malawi utilized PAR as a component of CCA to challenge dominant agricultural models that were unsuitable for them in the long term.

Table 3 below summarizes key findings on adequate CCA. Few studies directly measured adequacy; most used proxies like avoiding harm, livelihood stability, social equity, or food security. Community-based initiatives that incorporated distributive justice showed the strongest links to adequacy. Small island states highlighted the inadequacy of external designs that ignored their cultural and social norms (Resurrección et al., 2019). Outcome sufficiency was rarely achieved without inclusive processes and the presence of procedural and recognitional justice.

The lack of conceptual clarity regarding successful and adequate adaptation in the literature also creates difficulties. It is difficult, for example, to determine when a CCA action has, in fact, not achieved its intended effect, but instead increased vulnerability- maladaptation. Maladaptation as a concept remains undertudied in research, with many scholars expressing reluctance in proposing a universal definition (Rouzaneh and Savari, 2024; Westoby et al., 2020). On the other hand, the presence of numerous similar terms to ‘success’ and ‘adequacy’ contributes to the lack of conceptual clarity. Owen (2020) conducted a systematic review of CCA literature to determine the metrics for effective CCA. Indicators of effectiveness identified in that study include improvements in resilience, such as reduced risk; enhanced social relationships; improved environmental quality; increased access to resources; strengthened institutional connections; and improved governance. Significant gaps remain in accurately identifying genuinely successful CCA due to the numerous and sometimes disconnected metrics from both policy and procedural viewpoints. Implementing these metrics is challenging because they cannot be uniformly applied across all contexts; instead, they must be tailored to each specific CCA situation. In other words, what is considered a successful or adequate CCA outcome in one context may differ in another or among different individuals evaluating a single CCA process. This issue arises from diverse epistemologies and ontologies in climate change contexts (Goldman et al., 2018). The existence of diverse epistemologies and ontologies creates substantial gaps in the literature.

3.3 Gaps in the literature

While the studies provide useful evidence, significant gaps remain. This section identifies where the evidence remains incomplete and inconsistent. For example, studies acknowledge that social justice for marginalized groups is integral to CCA. Still, they often fail to include outcome-based measures as the main objectives in most existing studies. Thus, they fail to measure their adequacy. This oversight is partly due to the difficulty in measuring social outcomes achieved in the short term (de Coninck et al., 2018), in contrast to the technical objectives that parties mostly pursue under CCA processes. Technical outcomes in the short term remain core objectives.

The timeline for CCA itself presents a challenge for measuring successful and adequate CCA. Much of the literature analyses CCA either as a long-term strategic vision or as short-term immediate responses, while overlooking an important middle ground. More research is needed on adaptive planning that combines long-term strategies and short-term no-regret measures through a trans-scalar approach (van Alphen et al., 2021). This approach links the immediate needs of local participants with the long-term strategic visions of external stakeholders and their government. Current studies generally focus on either bottom-up or top-down methods, but often fail to combine both (Clar, 2019).

The existing literature on positive peace themes or success and adequacy does not clearly label them as such. When topics like participation, power, and social justice are discussed, they are not explicitly identified as positive peace themes. As a result, they remain separate from the field of peace and conflict studies. Only a limited number of studies in the literature empirically connect adaptation actions to peace and conflict studies (Chilinde and Mamiwa, 2022; Gaborit, 2022). The connection established is also very broad. Few studies expressly define success and adequacy in CCA, making it difficult to compare different analyses. Moreover, the links between positive peace and adequacy remain conceptual, rather than empirical. CCA studies lack sufficient empirical case studies demonstrating how these themes have been practically or consciously applied for successful CCA (Fünfgeld and Schmid, 2020).

Furthermore, research is essential to investigate the interconnections between different aspects of peace and their impact on successful adaptation, rather than focusing solely on the negative effects of one element (Adekola et al., 2022; Tripathi and Mishra, 2017) on another, hindering successful CCA. The focus on the links between various parts of CCA usually examines how one factor, like power, can hinder participation. The positive relationship between different themes and successful and adequate CCA has not been sufficiently explored in the literature. Themes such as power are often viewed from a negative standpoint (conflict) and are usually interpreted in terms of political power (Chilinde and Mamiwa, 2022). These gaps highlight the need for a comprehensive case study that demonstrates how the inclusion of positive peace themes contributed to successful and adequate CCA.

3.4 A central illustrative case: community-based adaptation and peacebuilding in the Solomon Islands

To demonstrate how the positive dynamic between themes of positive peace and successful, adequate adaptation unfolds in practice, this subsection draws on a study from the Solomon Islands. The Solomon Islands case here is, however, primarily illustrative. The Solomon Islands case study also shows that procedural success does not automatically lead to the adequacy of CCA and highlights the importance of scale and context. The Solomon Islands is a developing country in the Global South. As an island nation, its geographic isolation limits accessibility and hampers its development potential. Its socio-political history, combined with extreme environmental vulnerability, is a crucial factor to consider in the context of peacebuilding efforts on the island. Climate change-related challenges in the Solomon Islands include sea-level rise, salt intrusion, coastal erosion, flash floods, landslides, cyclones, storm surges, food insecurity, and reduced salinity, which cause coral bleaching (Leal Filho et al., 2020). Climate change impacts the human rights of SIDS nationals (Cullen, 2018). The history of the Solomon Islands has been shaped by conflict and underlying tensions. In 1998, ethnic tensions erupted when militant youths from Guadalcanal attacked islanders from nearby Malaita. Further violence escalated in early 2000. This conflict stemmed from claims of unequal resource and wealth distribution dating back to colonial times. These underlying tensions sometimes flare into open conflict. Inequality in the Solomon Islands also has a gender component. Political leadership has marginalized women, giving them little or no influence in national affairs (Maebuta, 2014). CCA in the Solomon Islands must focus on addressing these social issues to be successful and adequate.

3.4.1 Community-based adaptation in Rendova Island, Western Province, Solomon Islands

Basel et al. (2020) employed a community-based CCA planning process in the Baniata and Lokoru communities on Rendova Island. An assessment of their approach shows the integration of social justice and equality—positive peace themes- as procedural, recognitional, and distributive justice within the CCA process. The Baniata community is a subsistence community that relies on local fishery products, groundwater, construction materials, and livelihoods. In contrast, the Lokoru community, which was primarily subsistence-based, is now increasingly dependent on cash income from the sale of copra and garden produce.

The criteria for selecting these communities included factors critical to successful CCA. These factors were strong leadership, a willingness to participate, feasible logistics, and existing governance structures. These indicators, which the authors incorporated into their criteria for community selection, closely align with Hamilton and Lubell’s (2019) metrics for successful CCA—access to information, procedural fairness, and cooperation. The willingness to participate emphasizes engagement as a core theme of positive peace. Strong governance structures promote social justice by ensuring equal access to resources and accommodating diverse perspectives. These also constitute elements of distributive and procedural justice.

The eventual CCA outcomes had some elements of adequacy. This was because participation was gender-sensitive, involving one male and one female Community Coordinator nominated to attend a three-day workshop. Representatives from two other communities also participated in the workshop. This, therefore, enhanced its social equity and legitimacy and reduced the possibility of long-term vulnerability. Moreover, the involvement of local people was meaningful. The vulnerability assessment method used in the community-based CCA planning process, Local Early Action Planning (LEAP), is a participatory and inclusive tool. But participation was not merely symbolic; participants actively contributed to the workshop activities. Agency and decision-making remained with local participants, making their involvement significant (Cattino and Reckien, 2021).

Social justice, as a theme of positive peace, was central to the CCA process. It encompassed elements of procedural and recognitional justice. The participatory approach brought together various stakeholders from different fields—including local groups, religious denominations, government partners, and the National Ministry of Environment and Climate Disaster Management. Involving individuals from diverse sectors facilitated knowledge integration and co-learning, which are essential for successful CCA. In the CCA planning process within the Baniata and Lokoru communities, the methodology specifically included access to information. Awareness materials were presented in Solomon Islands Pidgin. The awareness sessions featured videos and demonstrations showcasing local examples. Along with these communication channels, educational methods were employed to ensure that the materials were fully understood.

Equality, as a theme of positive peace, was also a core component of the CCA process. In this CCA process, it clearly addressed existing power structures, allowing for distributive justice. The socio-political history of the Solomon Islands illustrates that women have been historically marginalized and have lacked the opportunity to actively participate in decision-making regarding national socio-political issues. Socio-cultural norms also empower men rather than women in the decision-making process in Solomon Islands (Mikulewicz, 2018). This situation has granted men greater power and representation, resulting in a significant power imbalance between men and women. To tackle this power imbalance, the CCA process was designed with gender sensitivity in mind. Approximately 40% of the community representatives who participated as Community Coordinators and in workshops were female.

This CCA process, while it deeply incorporates positive peace and includes elements of successful and adequate CCA, also faces limitations. These limitations arise from ongoing structural barriers that restrict the adequacy of this CCA action’s outcomes. Participants mentioned local resistance to installing phone towers due to cultural beliefs. They aimed to improve telecommunications with radios and phone towers while also reducing disaster risk; however, they faced opposition from the local community. Local knowledge can oppose CCA (Kirkby et al., 2018). Local actors who benefit from maintaining the current situation are known to oppose certain CCA efforts. Conflicting interests continue to challenge the process despite the integration of positive peace themes in CCA (Fedele et al., 2019). Moreover, the representation of women in the CCA process, did not lead to real inclusion as it was not numerically equal (50/50); a 40% representation of women still falls below the required number for equal representation. This is very important in the socio-political context of the Solomon Islands, characterized by the marginalization of women. Women play a pivotal role in developing local strategies. CCA policies and processes must, therefore, ensure that women’s vulnerabilities are reduced during CCA (Resurrección et al., 2019).

3.5 A conceptual framework linking positive peace with successful and adequate adaptation activities

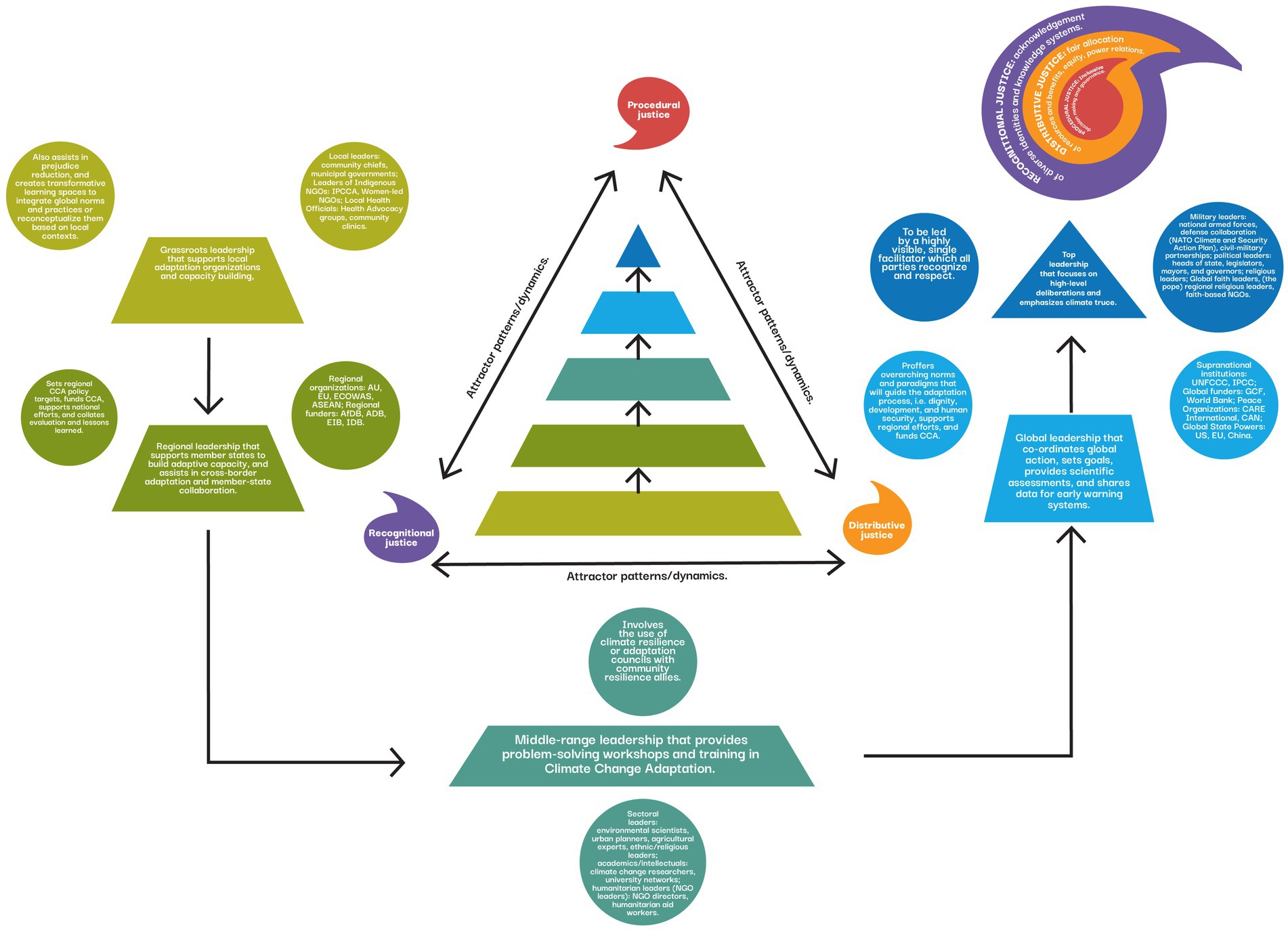

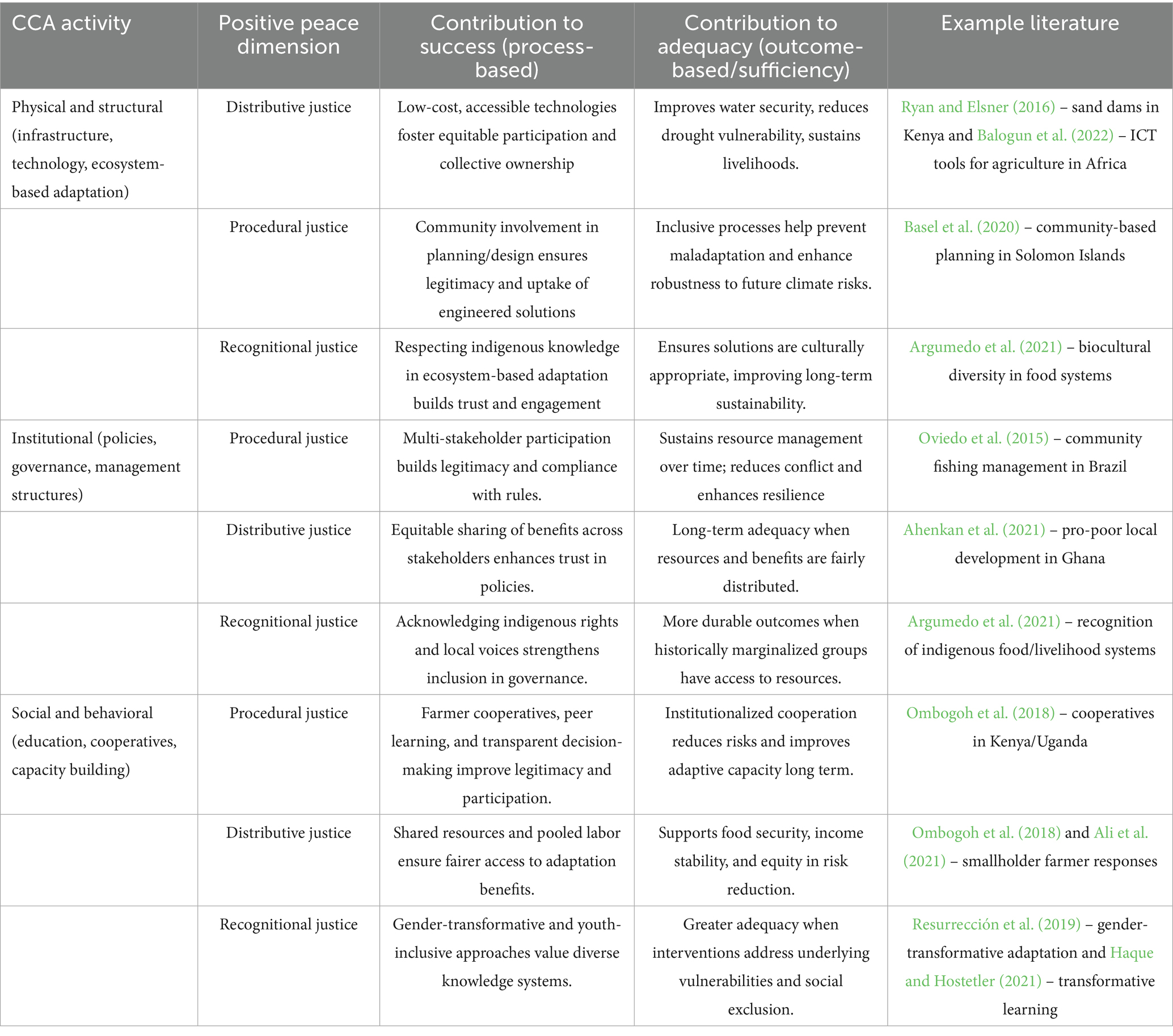

This subsection synthesizes the evidence into a conceptual framework (Figure 2 and Table 4), which links positive peace with success and adequacy. The framework provides a basis for the subsequent Discussion, where we interpret findings through the lens of Galtung’s positive peace and Millar’s trans-scalar peace system. Similar to Owen (2020) systematic review on effective CCA, this conceptual framework categorizes CCA into three main activities: physical and structural, institutional, and social activities. Physical and structural adaptation activities emphasize the tangible aspects of adaptation, such as the built environment and the services provided for CCA. Institutional actions pertain to policies and programs, while management approaches facilitate tangible adaptation. Social activities tackle the educational, informational, and behavioral aspects of CCA. Findings suggest that positive peace, when integrated into various categories of CCA activities, may result in successful and adequate adaptation.

Figure 2. Reframing CCA through positive peace [adapted from Millar, 2021]. (CCA, Climate Change Adaptation; NGOs, Non-Governmental Organizations; IPCCA, Indigenous Peoples’ Climate Change Assessment; AU, African Union; EU, European Union; ECOWAS, Economic Community of West African States; ASEAN, Association of Southeast Asian Nations; AfDB, African Development Bank; ADB, Asian Development Bank; EIB, European Investment Bank; IDB, Inter-American Development Bank; NATO, North Atlantic Treaty Organization; UNFCCC, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; IPCC, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; GCF, Green Climate Fund; CAN, Climate Action Network; US, United States; EU, European Union).

Table 4. Conceptual framework linking positive peace dimensions to success and adequacy in climate adaptation activities.

In a study, Ryan and Elsner (2016) examine physical and structural CCA activities in Kenya. They discover that ecosystem-based adaptation through sand dams represents an appropriate technology for drylands. Sand dams highlight distributive justice, as their low-cost and straightforward construction methods enable numerous local residents to access water. The study demonstrated that sand dams have proven effective in Kenya, contributing to equitable outcomes and mitigating climate risks. Oviedo et al. (2015) in another study examined institutional CCA activities in Brazil. The community-based fishing management structure that supports aquatic reserves in the Amazon basin emphasizes procedural justice by involving multiple stakeholders. This process proved successful, mitigating climate risks for freshwater fish populations and enhancing economic resources for households during the five years following implementation. Findings from another study in Uganda and Kenya also show that social and behavioral CCA activities incorporate positive peace for successful CCA. Farmer cooperatives allowed farmers to meet regularly to exchange knowledge and skills about farming techniques. The cooperatives also facilitated equal access to resources, thereby embracing distributive justice. This was achieved by pooling resources to purchase agricultural products like seeds. Farmers also shared labor among themselves. The results indicated that CCA was successful. There was a reduction in risks, and it was favorable as it improved socio-economic and environmental conditions (Ombogoh et al., 2018).

Argumedo et al. (2021) in their study also show that in institutional CCA activities, economic and livelihood options reflect positive peace dimensions when they acknowledge indigenous peoples in local spaces, who often face limited livelihood choices. However, Haque and Hostetler (2021) have argued that integrating positive peace in local spaces must also incorporate transformative learning metrics, where climate disasters do not present a ‘disorienting dilemma.’ Indigenous knowledge may sometimes be inaccurate and should be supplemented with scientific knowledge through co-production.

Table 4 below shows how procedural, distributive, and recognitional justice, the core dimensions of positive peace, contribute to process-based success and outcome-based adequacy across various CCA activities.

The results shown above demonstrate how adaptation practices in the Global South address issues of success and adequacy. The synthesis and accompanying tables emphasize these patterns across the 102 studies. A clearer interpretation of these findings requires placing them within broader conceptual frameworks of peace and justice. The discussion that follows draws on Galtung’s concept of positive peace and Millar’s trans-scalar system to explain why some justice-focused processes lead to success in adaptation and others result in adequate outcomes.

4 Discussion

Building on the descriptive synthesis in the Results, this section interprets the findings using established peace and justice frameworks. Specifically, Galtung’s concept of positive peace helps explain how procedural, distributive, and recognitional justice influence perceptions of adaptation success and adequacy. Additionally, Millar’s trans-scalar peace system shows why processes that succeed at the local level may not necessarily be adequate when scaled through national or international structures. Using these frameworks, the Discussion moves beyond simply listing adaptation outcomes and explores the deeper dynamics that connect justice-focused processes with sustainable adaptation in the Global South.

Galtung views peace not just as the absence of violence but as the presence of fair social relations. However, Millar’s trans-scalar peace system adds depth to this perspective. The use of Millar’s framework is not a result of the findings above or the study, but a theoretical lens for interpreting the findings. In Millar’s model, effective adaptation relies on coherence across different levels. Without this coherence, locally accepted processes might remain ineffective—especially in Small Island States with limited resources. By framing findings within these models, the review demonstrates that the link between positive peace and adaptation outcomes is not always successful, but might be successful when deliberately implemented. Justice-focused processes positively influence both the success and adequacy of adaptation when supported across different levels.

4.1 Reframing climate adaptation through positive peace

Institutions and systems can determine the success or failure of CCA processes. Therefore, it is crucial to effectively integrate the social aspects of CCA into existing systems. CCAs are socio-political processes that require capabilities to produce equitable and effective outcomes (Malloy and Ashcraft, 2020). These capabilities should encompass the institutions and standards essential for achieving successful and adequate CCA results. These standards are grounded in positive peace dimensions.

Millar (2021) Transscalar Peace System offers a structured approach to integrating positive peace dimensions, allowing CCA to be redefined beyond simple technical adaptation. In Figure 2 below, positive peace is linked with CCA to empower relevant actors at all levels. Since positive peace is inherently normative, the norms related to positive peace embedded in CCA processes must be clearly explained and understood by all involved to bridge gaps in knowledge and worldview differences. Mayer suggests that norms applicable in CCA should generally align with existing norms in human rights, development, and other legal and institutional fields. According to Mayer, there is no need to create new norms (Mayer, 2021). In this discussion, such norms include themes of positive peace, specifically social justice and equality—reconceptualized as procedural, distributive, and recognition justice, aligned with IPCC metrics for easier operationalization. Redefining and defining norms for use in CCA through local perspectives is vital for positive peace because it empowers local actors with agency. Redefining and establishing operational procedures in CCA may require transformative learning in certain local contexts, as it can help reduce prejudice and clarify where knowledge gaps exist or where climate risks are perceived as non-disorienting dilemmas (Haque and Hostetler, 2021). Millar describes this process as backward mapping, which allows local actors to shape and develop structures that better reflect their realities during Community-Based Adaptation (CBA).

While CCA actors at the international level can provide positive peace norms to guide the operationalization of CCA, it is the ‘local’ that must clarify what those norms mean to them based on their specific context. According to Millar, the consistent affirmation of these norms by local actors will lead to institutionalization and create attractor patterns. Attractor patterns are indicator states of where systems in such local spaces stabilize and where routines become established over the cyclical lifetime of the CCA process. Achieving routines under these localized definitions is an indicator of adequate CCA.

Reframing CCA through positive peace based on Millar’s trans-scalar peace system requires top leadership focused on high-level deliberations. This should be accomplished through a highly visible single facilitator whom all parties recognize and respect. This facilitator could include political leaders, heads of state, legislators, mayors, governors, religious leaders, and global faith leaders who continue to promote long-term positive environmental actions. At the second level, international actors establish comprehensive norms and frameworks that guide local adaptation. They also coordinate global actions, set goals, and provide scientific assessments. Global leadership at this level shares data for early warning systems. Supranational institutions like the UNFCCC, IPCC, global funders, the World Bank, peace organizations, and influential powers such as the EU and China play crucial roles in global leadership.

Additionally, middle-range leadership at the third level offers problem-solving workshops and training in CCA. Actors at this level include climate resilience or Community Climate Adaptation (CCA) councils, as well as community resilience allies. The types of actors at this level include sectoral leaders, environmental scientists, urban planners, agricultural experts, ethnic and religious leaders, academics and researchers, university networks, NGO directors, and humanitarian aid workers. The cross-disciplinary nature of actors at this level makes their findings and discussions crucial for advancing climate resilience at higher levels. Regional actors at the fourth level support member states in building their adaptive capacity and assist with cross-border collaboration and member state cooperation—regional organizations like the EU, ECOWAS, and ASEAN operate at this level. They work together to set state-regional CCA policy targets, fund CCA initiatives, support national efforts, and compile evaluations and lessons learned.

Local actors at the grassroots level provide leadership that supports local adaptation organizations and strengthens the capacity of community members. They also work to reduce prejudice where social norms hinder the acceptance of global standards, creating transformative learning spaces that either integrate global norms and practices or reconceptualize them to fit local contexts, since CCA actions are place-based (Siders et al., 2021). Bennett et al. (2019) refer to these learning spaces as transformative spaces. Fonseca et al. (2022) describe such spaces as ecovillages where collective learning is continuously reconstructed. Local knowledge plays a crucial role in developing a comprehensive understanding of adaptation strategies beyond a single region (Ross et al., 2015). Grassroots leadership encompasses local leaders, community chiefs, municipal governments, leaders of indigenous non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and women-led NGOs.

The reconceptualization of CCA using Millar’s transscalar peace system creates successful and adequate CCA because it addresses socio-political concerns and promotes integration across scales. Focusing solely on physical externalities or processes leads to maladaptation. Sustainable CCA is viewed as a transformative, development-oriented action that supports the progressive realization of both structural and environmental transformation. The term ‘development,’ particularly when used in Global South transscalar actions involving external actors, is often viewed with skepticism as a hegemonic instrument. In CCA actions, Western normative engagement with Global South interactions has typically focused on technical issues that align with the current worldview but fail to challenge the dominant perspective (Briggs and Sharp, 2004). Even when integrating scientific and non-scientific aspects of CCA, power dynamics between stakeholder groups and alternative knowledge systems present a barrier (Briggs, 2013).

However, systematizing CCA in the Global South through positive peace, as derived from Galtung and organized under Millar’s transscalar peace system, can address these limitations and create successful and adequate CCA. The localized reconceptualization of guiding norms and success metrics can serve as attractor patterns to gauge the effectiveness of CCA interventions while ensuring the retention of local particularities. The post-colonial ‘state’ of the Global South is a mimicry and emerges in the international system as a direct product of colonization. The success and adequacy of CCA projects, in the same vein, is judged in relation to the ‘international.’ The argument is therefore for a variant of CCA that is transformative and seeks to address systemic injustices that have been institutionalized while also addressing the environmental issues that arise from them. This is achieved when post-colonial states of the Global South, under the CCA, recognize international standards but derive normative and institutional agency in a self-determined and localized manner (Jabri, 2016).

4.2 Critiques of positive peace: addressing the challenges

Galtung defined positive peace as the elimination of all forms of structural violence. He equated positive peace with social justice and equity, noting that violence is not always visible within groups (Simangan et al., 2021, 2022; Sharifi and Simangan, 2021). Critics argue that Galtung’s concept of positive peace has several limitations.

First, the parameters or indicators for measuring positive peace are unclear, unlike negative peace, which has defined parameters for identification—the absence of armed conflicts (Scholten, 2020). Second, positive and negative peace, seen as dialectical variations, are considered inadequate to fully address the concept of peace across different levels. Significant contributions and events have challenged these dialectical framings, proposing new concepts and frameworks to assess peace (Olivius and Åkebo, 2021) at various levels. The meaning of peace can vary significantly depending on the level of analysis. For instance, peace at the local or community level often markedly differs from peace at the national level (Scholten, 2020). Third, and most importantly in the context of this study, the expansive nature of positive peace and its normative qualities make practical operationalization challenging in the mid-term. This broad scope means that any real or perceived injustice could be seen as a lack of positive peace; it might even manifest physically or psychologically. Furthermore, it can occur at any level of social organization, from interpersonal to global (Gleditsch et al., 2014). Also, the goal of operationalizing positive peace is perfect equality, which is not practically achievable or necessarily desirable (Barnett, 2007).

However, recent research clearly recognizes and refers to positive peace as a relevant feature that facilitates the synthesis between the environment and social integration (Simangan et al., 2021). This framework also acknowledges and builds on these recent findings. The conceptual framework in this review addresses the limitations of operationalizing positive peace. It grounds positive peace themes—participation, social justice, and equality—in dimensions of justice (distributive, procedural, and recognitional) and integrates them across various sectors of adaptation (institutional, social, physical, and structural). Procedural justice embraces the participatory aspects of positive peace by allowing multiple stakeholders, particularly the marginalized, to actively engage in the CCA decision-making process.1

Distributive justice promotes equality by addressing power inequalities and ensuring equal access to resources and power at the pre-planning, planning, implementation, and evaluation stages, alongside other related components of the CCA process. Recognitional justice fosters equality by acknowledging the voices, perspectives, and cultural differences of multiple stakeholders, integrating them across scales. Millar’s trans-scalar peace system (2021) provides evidence of how this conceptual framework can be applied across scales for successful and adequate CCA. Millar’s systematic trans-scalar system, reconceived as CCA in this research, actually builds on Lederach’s Peacebuilding Triangle.2 Millar himself recognized climate change as one of the emerging challenges to peace. At the very least, he argues that climate change will exacerbate social conflicts, either directly or indirectly. Thus, the trans-scalar peace system draws lessons from the ‘local turn’ but also recognizes the need to include the global, regional, and international levels.

Solely bottom-up CCA processes will not suffice to address the dynamic challenges of systemic injustices across scales. While Lederach’s model recognized the importance of middle actors in achieving socially just processes, it focused on how such processes occur within a single state. It did not consider the broader regional structures that influence local processes. Millar builds on this by addressing dynamics at the regional and global levels. It does not prioritize those middle actors but empowers relevant actors across each scale. Power dynamics and operational challenges may still hinder the achievement of socially just CCA within this framework, where international actors develop ‘solutions’ and metrics that favor them. Power continues to exert an uneven influence on decision-making and the enforcement of processes. Also, operational challenges arise from the unpredictable nature of self-organization in local spaces, as well as the highly normative character of positive peace, which is subject to various epistemological and ontological variations.

However, Millar proposes using backward mapping and attractor dynamics to tackle these challenges. Backward mapping prioritizes the most relevant actors at each scale in the process, granting them the opportunity to exercise agency in informing and designing CCA structures. Attractor patterns, in contrast, are indicator states where systems settle and are habitual patterns that are maintained over time as proof of adequate CCA. Developing such behavioral changes necessitates transformative learning for individuals in local spaces or the integration of learning across scales. It is a gradual process that, once achieved, naturally reinforces itself.

This approach makes positive peace principles measurable within policy and planning. This framework directly responds to calls for legitimacy and equity in CCA. Ensor et al. (2019) argue that CCA processes must account for changes in non-biophysical aspects as an alternative starting point for conceptualizing CCA. For example, in Nepal and South Africa, livelihood patterns are shifting, with a decrease in household investments in the non-agricultural economy. An approach that views CCA as solely a biophysical process will rely on conventional practices. This neglects the transformation of rural and socio-political identities within CCA processes—identities that are also part of the epistemological starting points that foster maladaptation. CCA activities in agriculture, for example, aim to address production constraints but often overlook the multidimensional challenges faced by rural households and the needs of those who have left or are planning to leave the agricultural sector.

This issue of building on conventional CCA reflects the current situation in Ghana. In Ghana, young people lack the power to influence government policies on CCA. Studies reveal a disconnect between the adaptation discourses of the government and scientists and those of young people. Farming and labor migration have lost their appeal, leading to a shift in aspirations toward education due to perceived economic benefits. However, the government continues to create policies that support farming (Laube, 2016). The conceptual framework and approach in this study hold positive implications for government policies and can help address the limitations associated with persisting in conventional CCA practices.

While these limitations may be effectively addressed with the approach discussed in this review, not all justice-oriented climate adaptation projects are guaranteed to succeed. In many local contexts, participatory processes often reinforce existing power inequalities rather than overcoming them. This is because participation does not often translate to genuine inclusion. Only by acknowledging these limitations can this review offer a balanced and critical perspective on the research area. Moreover, existing policies and entrenched practices in local contexts often create systemic hindrances and reinforce vulnerabilities.

4.3 Policy implications for extremely climate-vulnerable regions of the global south

Despite the advantages that the proposed approach to CCA in this review provides, systemic limitations, as reflected in practice and policies, still reinforce vulnerabilities in many areas. Under current CCA policies in highly climate-vulnerable regions of the Global South, climate harms are primarily identified through natural externalities such as sea level rise, cyclones, droughts, and coastal erosion. These negative externalities are then addressed in relation to their impacts on ‘critical’ sectors (Forster and Woodham, 2024; Iese et al., 2020; Ng Shiu et al., 2024; Jarillo and Barnett, 2024). The limitation of a narrow focus on externalities is that it restricts the ability to address latent climate impacts and structural contributors.

Additionally, non-systematic adaptation policies that focus on specific sectors create problems for less visible sectors, resulting in maladaptation (Magnan et al., 2016). Current actions often conflict with future climate risks, and vice versa (Owen, 2020). A focus on externalities also means that adaptations do not adequately address impacts in an anticipatory and transformative manner (Robinson, 2017). This approach restricts the capacity for adaptation to tackle structural (Galtung, 1969) or ‘slow violence,’ which becomes ‘decoupled from its original causes by the workings of time’ (Nixon, 2011).