- 1School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

- 2Society for Planet and Prosperity, Abuja, Nigeria

- 3Department of Political Science, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria

Introduction: As climate governance increasingly adopts multilevel approaches, subnational actors play a central role in achieving national and global climate objectives. However, in Nigeria, as in many other developing countries, the role of subnational actors in climate governance remains underexplored. Understanding their institutional readiness is crucial for meeting national climate commitments, including the 2060 net-zero target. This paper presents the first comprehensive assessment of climate awareness, policy, and action across all 36 Nigerian states.

Methods: Using a mixed-methods design, the study combined document and budget reviews, a national survey of 1,306 respondents from relevant ministries and agencies, and a stakeholder validation workshop with over 600 participants. Indicators examined included climate literacy, policy presence and alignment, budgetary commitments, and inter-agency coordination.

Results: Findings reveal low climate knowledge among subnational officials, weak public awareness, and limited policy development. Only a handful of states, possess climate policies or action plans, and fewer than 20% have climate-related budget lines. Cross-sectoral collaboration and alignment with national frameworks are also weak.

Discussion: These gaps expose structural and institutional weaknesses that undermine Nigeria’s multilevel climate governance. Achieving the 2060 net-zero goal requires harmonized subnational frameworks, enhanced capacity-building, and innovative tools—such as performance-based disclosure and rating systems—to incentivize accountability and stimulate stronger state-level climate action. Positioned within debates on multilevel governance, the study highlights Nigeria as a critical test case of how federated system in the Global South can recalibrate institutions to transform symbolic commitments into substantive action.

1 Introduction

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy and most populous country, is grappling with the complex challenges of governing climate change associated with weak political will, limited institutional capacity, and fragmented policy coordination across multiple tiers of government (Koblowsky and Ifejika-Speranza, 2012; Olajide, 2022; Okafor et al., 2024). On the surface, Nigeria appears committed to advancing climate governance despite these limitations. Although the country remains heavily reliant on oil, which accounts for 86% of its foreign exchange earnings (Okoh, 2020), it has adopted several ambitious climate policy commitments. These include its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and a pledge, made at COP26 in Glasgow, to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060. This pledge has been codified in the nation’s Climate Change Act, which sets a net-zero deadline between 2060 and 2070. Complementing this, the federal government has issued two green bonds totalling over USD 30 million and established a National Council on Climate Change (NCCC) to coordinate national climate policy.

Despite these federal-level initiatives, a significant disconnect persists between national ambitions and the implementation at the subnational level. There is limited understanding of the level of climate awareness, the existence and scope of subnational policies, and the institutional capacity of state governments to address climate change within their jurisdictions. This gap is especially concerning, given the extensive evidence that implementing climate action at the subnational level is crucial for achieving national and global climate targets (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005; Bulkeley, 2010; Jörgensen et al., 2015b; Van der Ven et al., 2017; Fuhr et al., 2018; Ribeiro, 2023; Sulistiawati and Rembeth, 2025).

A widely cited example is the state of California, which emerged as a global leader in climate action through bold subnational innovation, in contrast to federal inaction in the United States (Mazmanian et al., 2020). Nigeria’s federal system, which devolves significant authority to its 36 federating states and a Federal Capital Territory (FCT), presents a similar opportunity to leverage the potential of subnational actors. However, capitalizing on this opportunity requires a clear understanding of the current climate governance landscape at the subnational level and deploying innovative approaches to stimulate more decisive climate action by the states. The challenge of fostering more decisive action at the subnational level is not peculiar to Nigeria but mirrors broader trends in developing federal systems where the decentralization of climate responsibility is often rhetorical rather than operational (Olajide, 2022; Ribeiro, 2023; Sulistiawati and Rembeth, 2025).

This article presents findings from a first-of-its-kind systematic assessment of climate awareness, policy development, and climate action across Nigeria’s 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The study provides a much-needed baseline, actionable reforms, and governance innovations for strengthening subnational climate action in Nigeria. With its large economy and population, high dependence on fossil fuel and deep-seated poverty, Nigeria is a major test case for balancing development imperatives with low carbon pathways and fostering climate action at the national level is a critical step toward increasing climate mitigation and enhancing climate resilience in the country.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 provides a theoretical overview of multilevel climate governance as a framework for coordinated climate action. Section 3 situates the discussion within Nigeria’s political, geographical, and environmental context and outlines the research methodology. Section 4 presents the empirical findings. Section 5 discusses these findings in relation to the multilevel governance framework and draws out implications for institutional and policy reform. Section 6 concludes with a summary of the key findings.

The significance of this study lies in its contribution to addressing a significant evidence gap in Nigeria’s climate governance discourse. By systematically mapping subnational climate awareness, institutional arrangements, and policy development, this research lays a vital groundwork for improving subnational climate governance and increasing climate action in Nigeria more broadly. This is vital not only for meeting the country’s NDC targets and long-term climate commitments but also for designing tailored interventions, capacity-building strategies, and investment plans that reflect the unique realities of Nigeria’s diverse subnational units.

2 Multilevel climate governance and coordinated climate action

Climate governance has been defined as “a range of purposive mechanisms and measures aimed at steering social systems toward preventing, mitigating or adapting to the risks posed by climate change” (Jordan et al., 2018, p. 715). It has also been defined by Bulkeley and Newell (2010, p. 6) as “the diverse ways in which public and private actors seek to regulate, steer and coordinate efforts to address climate change across different scale.” This second definition highlights both the role of multiple actors (public and private) and different levels of government authority (international, national, state, and local) in addressing climate change. This is now frequently referred to as multilevel climate governance.

Multilevel climate governance has emerged as a crucial framework for studying and facilitating coordinated action on climate change across various political jurisdictions. This approach highlights the vital role of subnational governments in combating climate change, transforming the way climate risks are framed and addressed across multiple levels. It also highlights the increasing political visibility and influence of subnational jurisdictions in the global effort to address other United Development Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs; Jörgensen et al., 2015a; Parnell, 2016; Guha and Chakrabarti, 2019; Carole-Anne and Okereke, 2022; Masuda et al., 2022).

The core justification of MLG is that achieving global climate goals requires a comprehensive approach involving collaboration among stakeholders at national, subnational, and international levels (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005; Bulkeley and Newell, 2010; Parnell, 2016; Van der Heijden, 2018; Fox, 2020; Harrison, 2023). MLG highlights not just the role of the various levels of governments within a nation but also the connectivity and collaborations across boundaries, including with Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and the private sector (Scott et al., 2023; Soto-Montes-de-Oca et al., 2024). Coordination and collaborations across levels of government (local, state and national) are often referred to as vertical collaboration, while coordination between government organizations at equal or similar levels (say across ministries, departments and agencies—MDAs) is referred to as horizontal collaboration. Transnational governance is a type of MLG that involves international organizations coordinating with governments and CSOs and the private sector (Fox, 2020; Soto-Montes-de-Oca et al., 2024).

MGL scholarship recognize that subnational governments play a dual role in climate governance, as they can either facilitate or hinder efforts to reduce carbon emissions. Subnational actions on climate change can mitigate the adverse effects of a leadership vacuum at the federal level (Mazmanian et al., 2020; Kammen et al., 2021). Policy coherence and coordination between national and subnational governments are crucial, as both levels hold jurisdiction over many climate-related issues (Gillard et al., 2017). MLG scholarship emphasize the need for cross-sectoral connections to encourage knowledge sharing and learning among subnational institutions, even in the absence of a genuine devolution of authority (Hsu et al., 2017; Mazmanian et al., 2020). A multilevel approach to climate governance ensures shared responsibilities among various actors, addressing local geophysical challenges effectively.

Despite the recognition of the importance of subnational governance, there remains a lack of effort in studying the means for operationalizing national climate agendas at the subnational level. Research by Hsu et al. (2017), Scott et al. (2023), and several others suggests that in many cases, the responses of subnational jurisdictions to climate change do not match the severity of the threat, especially in developing countries where institutional frameworks for multilevel collaboration are weak and hindered by structural disparities. Van der Heijden (2018), Guha and Chakrabarti (2019), Masuda et al. (2022) and several others have argued that the necessary policy instruments to accelerate national climate ambitions at the subnational tier remain inadequately explained. Betsill and Bulkeley (2006), Jörgensen et al. (2015a), and Masuda et al. (2022) among others share the view that, despite the increasing political visibility of subnational governments, their contributions to policy formulation are still substantially underappreciated. This gap hinders the devolution of powers across governmental agencies, which is essential for reducing climate risk and enhancing the resilience of vulnerable communities (Gillard et al., 2017; Ishtiaque et al., 2021).

Several studies adopting the MLG approach have explored the challenges of improving subnational climate governance. While MLG is generally seen as beneficial, it can also lead to conflicts over perceptions of accountability within the context of diverse institutional logics and relationships (Jörgensen et al., 2015a; Di Gregorio et al., 2019; Heinen et al., 2022). Nevertheless, Xu (2021) identifies MLG as an effective tool for conflict resolution. To foster effective change, it is crucial to have a thorough understanding of the current situation and the capacity of subnational institutions to manage climate change for long-term national development. This is especially urgent in developing countries, where the level of climate action at the national and, particularly, subnational levels has not been extensively studied.

There is hardly any existing published literature on the role of subnational actors in governing climate change in Nigeria. An unpublished thesis by Afolabi (2020) explored the role of Cross Rivers state in forest management in Nigeria. He finds that despite limited coordination and confusing lines of jurisdictions; the state and local governments play a crucial role in forest governance. Olajide (2022) evaluates the effectiveness of climate change policies and programs in Lagos State, Nigeria, and the KwaZulu-Natal provincial government in South Africa, but also compares the nature of intergovernmental relations in the two cases and their impact on designing effective climate change responses. His study suggests that the nature of the relationship between national and subnational authorities, including presence or lack of fiscal autonomy, is a major factor that shapes the ability of subnational governments to craft and implement effective climate strategies.

This research is crucial for understanding local challenges, formulating effective policies, and coordinating climate action. By examining different types of climate action and strategies that could boost subnational involvement in tackling the interrelated effects of climate change in a developing economy, this research adds to the body of knowledge on MLG and also contributes to promoting practical action on climate change in the most populous country in Africa.

3 Background and method

3.1 Background

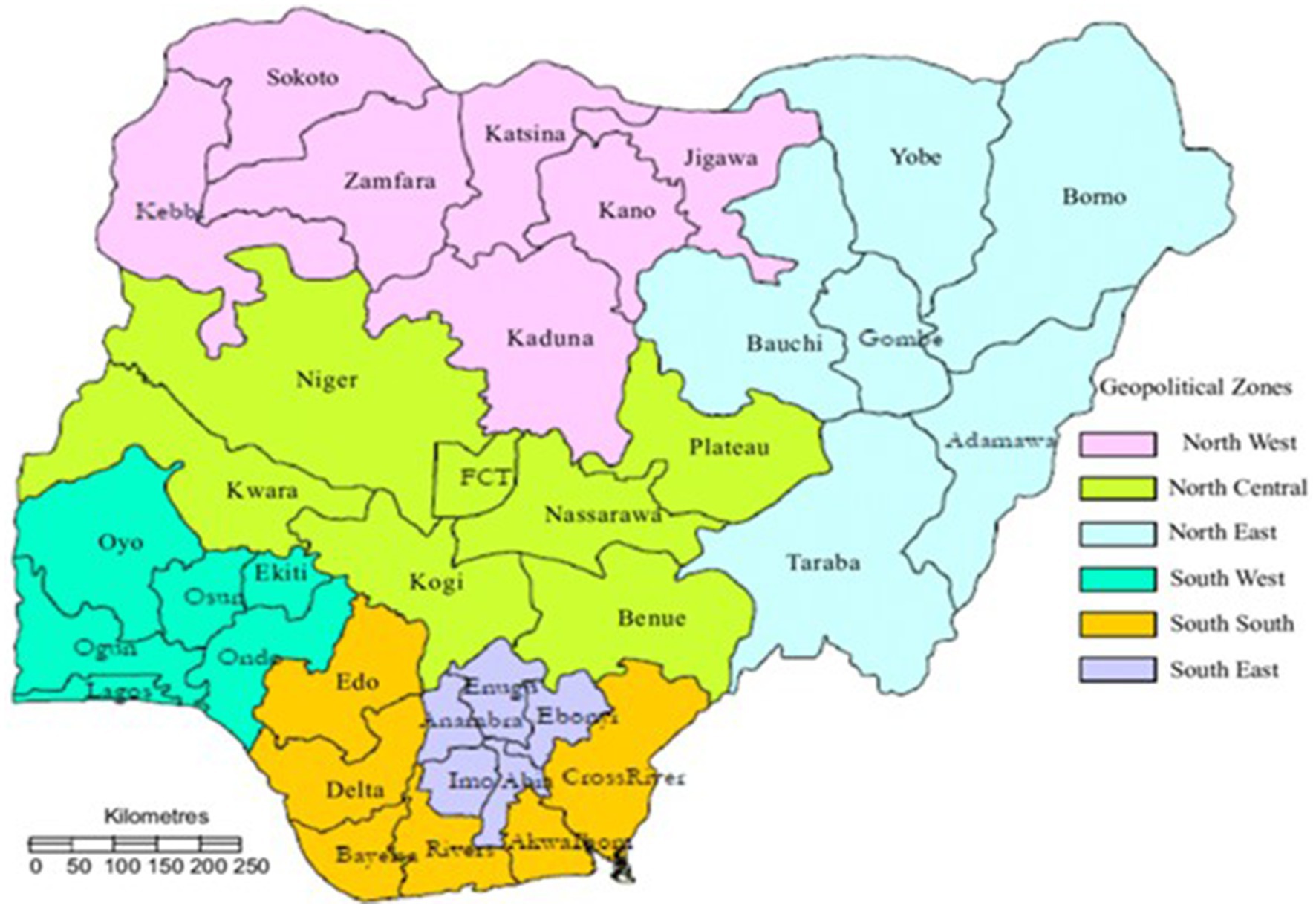

Nigeria is located on the western coast of Africa. It is a federation of 36 states and a Federal Capital Territory (FCT; see Figure 1). Each of the 36 states is a semi-autonomous political unit that shares powers with the federal government as enumerated under the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Nigeria is divided into six geopolitical zones: North-East, North-West, North-Central, South-East, South-West, and South–South, with a total land area of 923,768 square kilometers and an extensive coastline of approximately 853 km. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country, with a population exceeding 200 million. With an abundance of natural resources, notably large deposits of petroleum and natural gas, Nigeria has developed a fossil-fuel-dependent economy, with oil and gas exports representing a significant share of its foreign exchange income and trade balance. With its status as an important fossil fuel producer, Nigeria is the fourth biggest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter on the continent (Climate Action Tracker, 2023), coming after South Africa, Egypt, and Algeria.

Figure 1. Map of Nigeria showing study states: 36 states and the FCT, as distributed with the 6 Geopolitical Zones (Source; Authors).

Nigeria has a diverse geography, with climates ranging from arid to humid equatorial; and characterized by three distinct climate zones: a Sahelian hot and semi-arid climate in the North, a tropical wet climate in the South and a tropical savannah climate in significant parts of Northcentral region. There are two main precipitation regimes: a low precipitation in the North and high precipitation in most parts of the South. Climate change vulnerability analyses indicate that states located further north are more vulnerable than those located further south. The challenges associated with climate change vary across the country, as exposure factors differ regionally. Subsistence agricultural activity is generally seen as the most significant economic activity that is vulnerable to climate change.

Nigeria is ranked as the 8th most climate-vulnerable country in the world, according to the Climate Risk Index (Adil et al., 2025). According to the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN), Nigeria ranks 154th out of 185 countries on its country index, placing it among the 30 most vulnerable countries globally (ND-GAIN Index, 2021). Nigeria’s susceptibility to climate change is linked to its extensive geographic distribution. Weather extremes, such as drought, desertification, gully and coastal erosion, flooding, and erratic rainfall, are some of the effects of climate change in Nigeria (Federal Government of Nigeria (FGoN), 2020; Shiru et al., 2020). Flooding is a dominant climate impact in the Northcentral states of Benue, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, FCT, and Niger. The main impact of climate change in the North is desertification, land degradation, and drought (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, [UN OCHA], 2017; Azare et al., 2020). For the South, the major types of climate change impacts are flooding, gully erosion, and coastal erosion, which have led to the loss of arable land.

More frequent climate extremes with an increased loss of life and property, as well as damage to ecological systems and infrastructure are reported (Shiru et al., 2020). Moreover, climate change is a source of conflict over waterholes in the Northern region, while in the South, communal conflicts arise over freshwater resources as they become scarce (Azare et al., 2020). The estimated cost of climate change to Nigeria is between 6 and 30% of its GDP by 2050, worth between USD 100 billion and USD 460 billion (DFID, 2009; Federal Government of Nigeria (FGoN), 2020). Threats to food security are high as agriculture bears the brunt of the effects of climate change. Moreover, related issues such as lack of basic amenities, insufficient infrastructure, and inequality have been exacerbated by climate change (Owebor et al., 2025).

Climate change is increasingly featured in national discussions and political debates, but there is a sense that many government policy pronouncements are made in response to donor pressure and global climate events and are rarely translated into practical action. The Nigerian government is committed to achieving Net Zero by 2060 and has initiated some projects at different levels to facilitate the process. Despite the climate change initiatives at the federal level, the state of climate policy development and the capacity of states and local governments to address the challenge of climate change has hardly been seriously considered in national policy debates.

3.2 Methodology

The research approach comprised (i) desk review, (ii) a national survey of a diverse range of stakeholders, and (iii) a national stakeholder workshop involving over 600 participants. First, the research team conducted an extensive search and review of climate policies and actions in the 36 states of the Federation and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). Data were collated from secondary sources, including published materials, policy statements, reports, newspapers, and websites. Consistent with the study’s objective, the team searched for evidence of the availability of a climate policy and/or action plan in the states, evidence of climate vulnerability, and evidence of the inclusion of climate change in the state budgets. The research team also downloaded and reviewed the budgets of the states to assess the extent to which they have allocated funds for climate action.

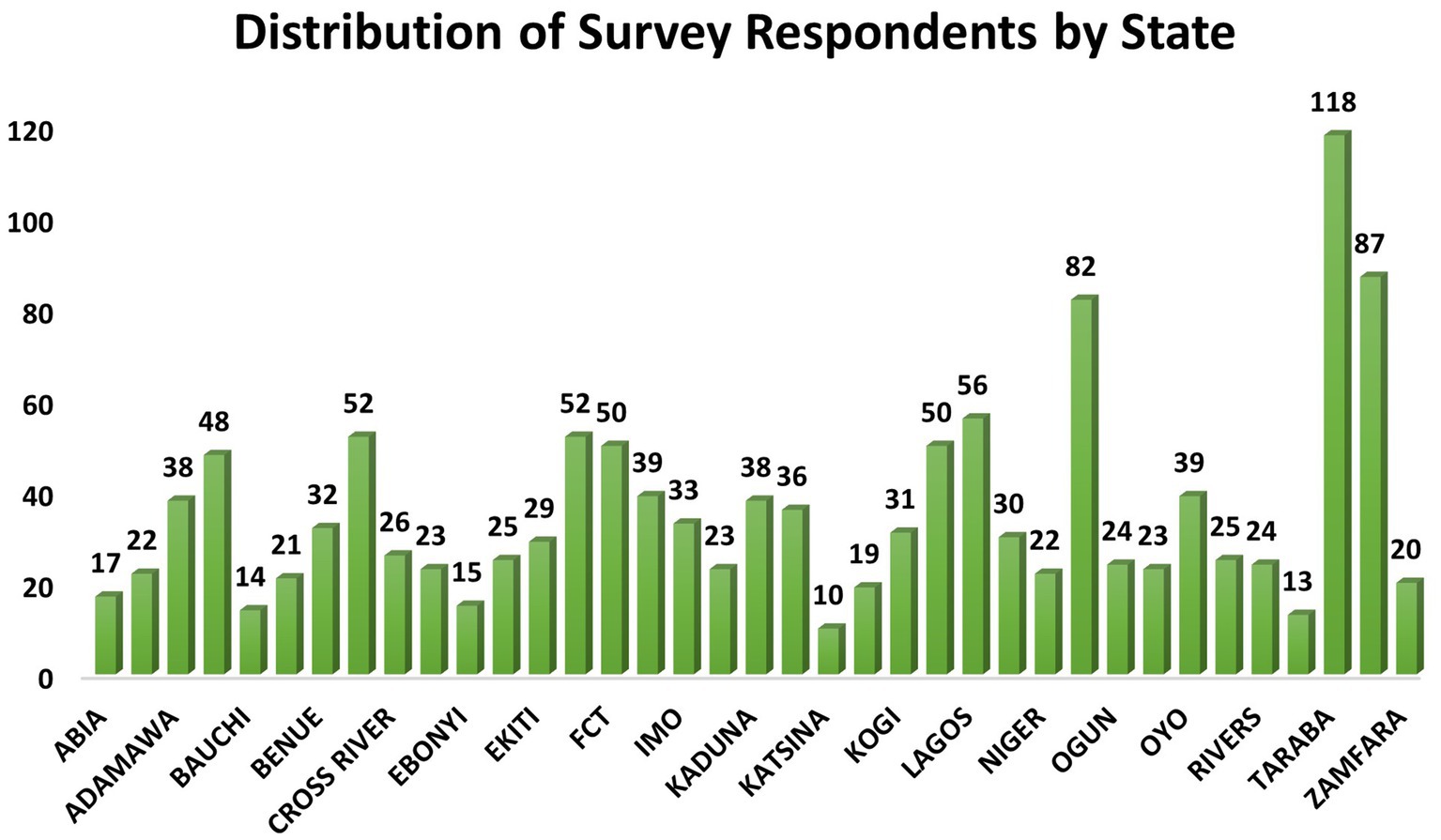

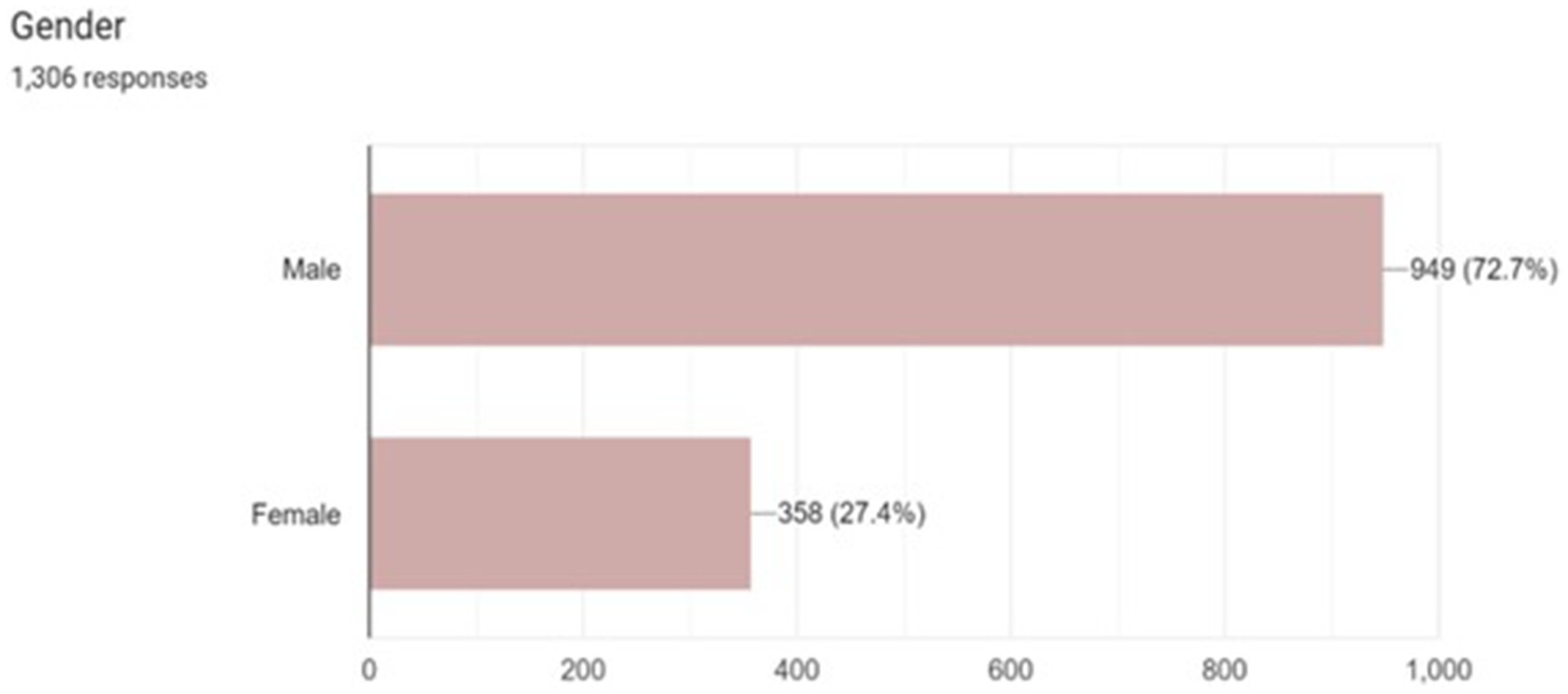

The second aspect of the research method involved an extensive survey involving 1,306 participants from across the country. To identify survey respondents, including Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs) engaged in the development and implementation of climate policies at the subnational level, we first conducted a stakeholder mapping exercise, following which the team sent both online and physical surveys. The stakeholder mapping and survey administration were done in close collaboration between the research team, the Nigeria Governors Forum, and the Department for Climate Change (DCC) of the Federal Ministry of Environment. The use of the Google platform for the online survey instrument facilitated the extensive distribution of the survey among subnational stakeholders. Figures 2–5 show the distribution of the respondents based on states (2), gender (3), age group (4), and employment (5). The information shows that the vast majority of the people who completed the survey are civil servants.

The survey questionnaire was distributed between July and September of 2023 to 1,510 respondents across the 36 states of Nigeria. A total of 1,306 people returned their completed surveys, yielding an over 90% return rate (See Appendix 1 for the consent form and survey questions). Having analyzed the survey results and triangulated the responses through further independent research and speaking with seven experts, a preliminary report was drafted and used as a basis for a national stakeholder workshop. The hybrid workshop, held in Abuja in December 2023, involved the participation of over 600 stakeholders, many of whom were among those who completed the survey. The workshop involved the presentation and discussion of the reports, including key takeaways, governance, and policy implications.

The research measured perceptions of climate impact, level of climate knowledge and awareness, as well as the quality of climate governance in the 36 states of Nigeria, including the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). Specific indicators of governance include the presence or absence of a subnational climate policy and climate action, evidence of climate change appropriations in states’ budgets, and the quality of collaboration with state and non-state actors in the states. Documents from ministries, departments, and agencies, as well as current national climate policies, serve as the foundation for information obtained from secondary data sources. The Google form facilitated analysis, and simple percentages and ranking were used in the data analysis; the results were cross-checked with existing literature.

As previously mentioned, this study represents the first attempt to systematically map climate awareness across Nigeria’s states. It fills a gap in existing scholarship. While subnational climate governance has been studied in places like Latin America, comparable work remains scarce in Nigeria and much of Africa. By focusing on state institutions and governance structures, this research creates a clear baseline that others can build upon. The survey tools and analytical framework were intentionally designed so they can be replicated and adapted elsewhere, offering a foundation for both comparative studies and shared learning across different regions.

However, despite the novelty, certain methodological limits must be acknowledged. The questionnaire has not undergone statistical validation, such as tests of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) or factor analysis, which would have confirmed whether the questions consistently capture the same underlying ideas. Furthermore, there were no tools and analysis to mitigate the challenges associated with self-reporting of climate knowledge awareness of the respondents. These are fruitful areas for future studies. Our choice of method is justified by the exploratory aim of mapping variation across regions rather than developing a standardized scale. Hence our approach not only contributes a first baseline but also provides a framework that can be reproduced and adapted in other contexts.

4 Results and analysis

4.1 Level of climate knowledge among respondents

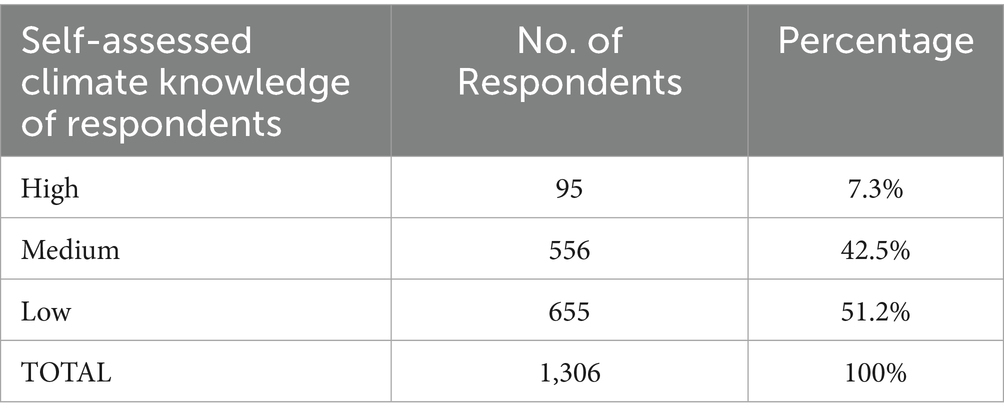

Survey findings indicate a fragmented landscape of climate knowledge among subnational stakeholders (Table 1). Of the 1,306 respondents, 51.2% rated their climate knowledge as low, 42.5% rated it as moderate, and only 7.3% reported having high levels of understanding. The high percentage of respondents that report low to medium knowledge of climate change is particularly concerning given most respondents are civil servants that one would have expected to be very familiar with climate change, sustainability, and environmental decision making.

A low or an uneven knowledge base of climate change obviously constitutes a major institutional bottleneck for effective policy development and implementation at the subnational level. While some studies have found that individual awareness or knowledge of climate change does not always translate to institutional or communal capacity (Amundsen et al., 2010; Tanner et al., 2009), there is plenty of work that has found that a persistent knowledge gap and low technical capacity among civil servants hinders effective policy formulation and implementation. Meckling and Benkler (2024), find that sound knowledge and capacity to enforce, monitor and implement are core determinants of climate policy ambition and effectiveness. A systematic review of barriers to adaptation policy at the national scale (Lee et al., 2022) finds that several studies identify limited staff expertise a key barrier that degrade policy quality and execution. The work of Biesbroek et al. (2018) which studied the link between public administration and climate adaptation shows that limited literacy, skill and learning system compromise the quality of climate ambition and implementation.

State-level disaggregation revealed that only four states—Ebonyi, Katsina, Nasarawa, and Plateau—exhibited the highest self-reported climate knowledge (50% or more). In contrast, Delta and Taraba states recorded the lowest levels, with 9 and 27% of respondents, respectively. These disparities highlight structural imbalances in capacity and investment in public awareness and institutional development, a pattern consistent with other federal systems grappling with decentralized climate governance (Fenton and Gustasfsson 2017).

At the same time, one must note that remarkable progress has been made on climate governance in some states. A relatively high level of awareness of climate change by respondents from Lagos State corresponds with remarkable bold steps on climate adaptation in that state, including a Lagos Climate Adaptation and Resilience Plan (LCARP, Lagos State Government, 2024) which is designed to address the vulnerabilities of the city to climate impact and equip decision makers with knowledge and data-driven assessment tools to calculate the economic cost of climate change and potential solutions. Similarly, its investments in electric vehicles, better public transport, and walking and cycling infrastructure are easing congestion while lowering emissions. Waste management reforms, including restrictions on single-use plastics, are addressing one of the city’s most significant environmental challenges (Olaoti, 2024). At the same time, coastal protection projects such as Eko Atlantic and grassroots efforts in communities like Makoko are helping residents adapt to flooding and erosion risks (Orimoogunje and Aniramu, 2025).

4.2 Public awareness of climate change at the subnational level

Although there is increasing engagement at the institutional level, public climate awareness remains critically low. Only 7% of respondents reported a perception of high levels of public awareness of climate change in their states, while more than 50% rated awareness as low (Figure 6). Zamfara exhibited the most pronounced climate awareness deficit, with 90% of respondents saying they believe the citizen of the state have low awareness of climate change. In contrast, respondents from Akwa Ibom and Jigawa posted perception of relatively high public awareness levels, likely attributable to localized NGO activity and targeted communication efforts. These results reinforce recent studies (Nkiaka et al., 2017) that identify limited or absence of sustained public engagement in promoting climate awareness in Nigeria. They also underscore the need for a communication-centered governance framework that makes climate discourse more accessible, especially in rural and underserved communities.

4.3 State of climate policy in the states

The research assessed the extent of climate policy development in the 36 states. Our investigation shows only seven (7) states and the FCT have climate policy documents that were publicly accessible (Figure 7). These states are largely those where political will, proactive political leadership, or “climate champions” facilitated the emergence of policy.

However, our analysis showed that most of the existing state-level policies were misaligned with the national climate policy framework, including the National Climate Change Policy (2021), the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), the Energy Transition Plan (ETP), and the National Adaptation Plan (NAP). Several of the policies were a long list of intended actions with no quantification of emissions and limited or no clear connection to the delivery of national or global climate targets. A sentiment widely shared by the workshop participants was that the development of climate policies by states was often a product of the action of few individuals that may not be strongly connected to mainstream economic development in the states or a response to some funding from international agencies rather than intended by the key political actors to radically alter the trajectory of development toward low-carbon paths. There was also a strong consensus among workshop participants that neither the federal government nor international donor agencies were doing enough to encourage states to translate national level targets (e.g., Net-zero by 2060, NDC, Energy Transition Plans) into state level climate goals.

Evidence from literature suggests that many other countries in both developed and developing countries struggle with vertical integration of climate governance, most especially in federal systems where there are limited standardized governance structures (Jörgensen et al., 2015b; Jogesh and Paul, 2020). Moreover, the absence of a unified national template or standards for climate policy development at the subnational level has widened the gap in ambition, structure, and implementation fidelity. This is also an outcome of structural imbalance between the federal and state governments, where power and instruments of governance are held by the former, with the latter facing political and economic barriers in financing climate action (Okoh, 2020).

4.4 Existence of subnational climate action plan

According to the survey, only 12 states have any form of Climate Action Plan. However, only the Action Plan from Lagos included measurable long-term targets over a given time scale (2020–2025). Interestingly 19.4% of respondents affirmed the existence of climate plans where documentary evidence showed no such plan existed and 53% declared they were uncertain whether a plan existed or not (Table 2). These numbers reveal a critical knowledge and institutional gap, further complicated by the knowledge and awareness gap discussed in previous sectors. It also reveals ambiguity over what constitutes a climate change action plan and indicates the need for some kind of guidance or template to promote some level of standardization for subnational climate planning.

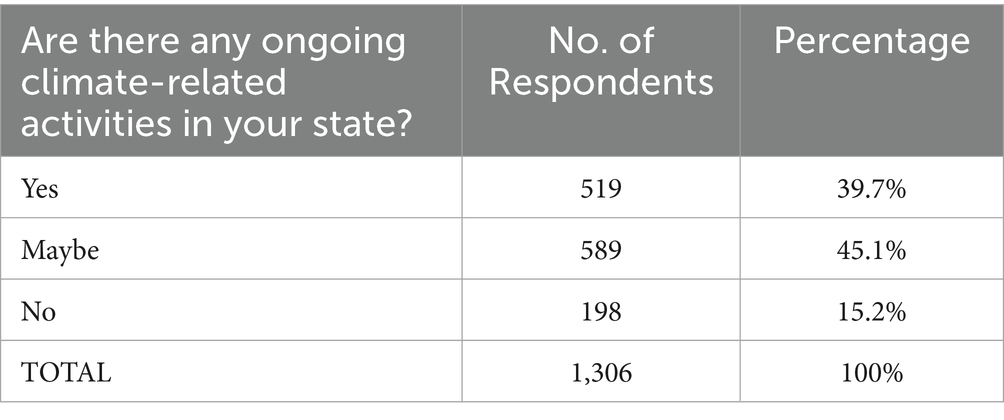

With regard to implementation, 39.7% of respondents acknowledged being aware of ongoing climate projects in their states, 45% were unsure, and 15% reported there were none. Documentary evidence and discussion during the national workshop suggested that more climate or climate-related projects were actually going on in the states than suggested by the respondents. One major discussion point that proved controversial during the workshop was how to decide what counted as climate change project. While some thought a climate project must be solely decided dedicated to reducing emissions or enhancing climate resilience directly, others felt that projects like improved urban transportation or improved seedlings which have climate-co benefits should also be counted. Where there was more consensus was on the point that most climate and climate-related activities were fragmented, donor-driven, and lacked long-term sustainability mechanisms (Table 3).

In any case, there was a strong sense among workshop participants and the expert interviewees that state-level climate policies and action plans in Nigeria remains ill-defined and fragmented. As several interviewees noted, most relevant policies are scattered across sectors lacking the coherence needed for effective climate governance. This reflects not only limited institutional capacity but also a structural deficit in vertical coordination between federal and state governments. The survey confirms that across all 36 states, there is no standard template or framework for climate planning—a gap that perpetuates disparities in policy ambition, design, and implementation.

4.5 Climate budgeting and financial commitments

Fiscal support is key driver or enabler for climate action at all levels of government. Accordingly, we decided to explore the extent to which state governments make provisions for climate action in their budgets. This question was also intended to trigger awareness that developing country states could not reasonably rely solely on international climate finance to fund climate ambition. The analysis revealed that only six states had dedicated budget lines for climate change (Figure 8). It was also found that even where climate-related interventions exist, such as in sectors addressing erosion control, renewable energy, or afforestation, they are rarely coordinated under a unified thematic umbrella. According to the survey results, 55% of states do not explicitly budget for climate-related activities. Budgeting, where it existed, was found to be often ad hoc and lacking strategic coherence, undermining implementation efficiency and long-term planning. This fragmented funding structure aligns with critiques in the existing literature, which identify the lack of financial mainstreaming as a key barrier to subnational climate governance (Pindiriri and Kwaramba, 2024).

4.6 Cross-sectoral collaboration and institutional coordination

Jurisdictional overlaps, unclear mandates, and institutional silos inhibit effective collaboration between state agencies, civil society, and the private sector (Lee et al., 2022). The survey also revealed that 32% of respondents confirmed the existence of multi-stakeholder partnerships in their states, while 48.5% were unsure whether their states had such a structure. Imo state stood out negatively, with 42% of respondents indicating a complete absence of collaborative frameworks. This supports earlier analyses (Okoh and Okpanachi, 2023) emphasizing that policy fragmentation, lack of interagency coordination and limited collaboration with private and civil society organizations severely constrain climate action in Nigeria. The over-reliance on federal leadership further weakens the operational autonomy of subnational actors.

There is some evidence that private sector investments and public-private partnerships (PPPs) play pivotal roles in enhancing subnational climate governance in Nigeria. In Lagos State, for instance, private companies such as First Bank have funded drainage rehabilitation and flood mitigation projects, complementing state-led urban planning initiatives and reducing flood risks in vulnerable communities. Similarly, companies like D.light have partnered with state governments in northern Nigeria, including Kano and Jigawa, to deploy solar home systems and mini-grids, enhancing energy access in off-grid areas and supporting state renewable energy goals. However, political interferences have limited the widespread diffusion of renewable energy solutions in the country, as most PPPs are awarded to political patrons with limited capacity (Okoh, 2020).

4.7 Key barriers to effective subnational climate governance

Stakeholders identified multiple barriers to effective subnational climate governance. Chief among them are: (i) federal-subnational power asymmetries (40%), (ii) political contestation and elite interests (20%), (iii) limited planning capacity, (iv) inadequate intergovernmental coordination, and (v) a dearth of technically competent personnel. These constraints are deeply rooted in structural and institutional deficiencies, consistent with scholarly insights on the limits of decentralized climate governance (Eckersley, 2017; Pierre and Peters, 2020). To date, many states have prioritized immediate development challenges over climate goals, thereby relegating climate policy to a secondary or symbolic role.

4.8 Proposed measures for enhancing subnational climate governance

While suggestions for strategies varied among respondents, a significant majority (50%) advocated for a non-structural, capacity-centered approach that prioritizes community-driven planning, backed by federal technical and financial support (Figure 9). Approximately 20% recommended integrating climate risk reduction into broader development plans, while 32% emphasized the deployment of low-carbon technologies, particularly solar energy. The majority (94%) agreed that subnational governments urgently require support in developing and implementing climate policies and green investment programs, especially in operationalizing the nascent carbon markets at the subnational level to rapidly increase revenue flows to green projects.

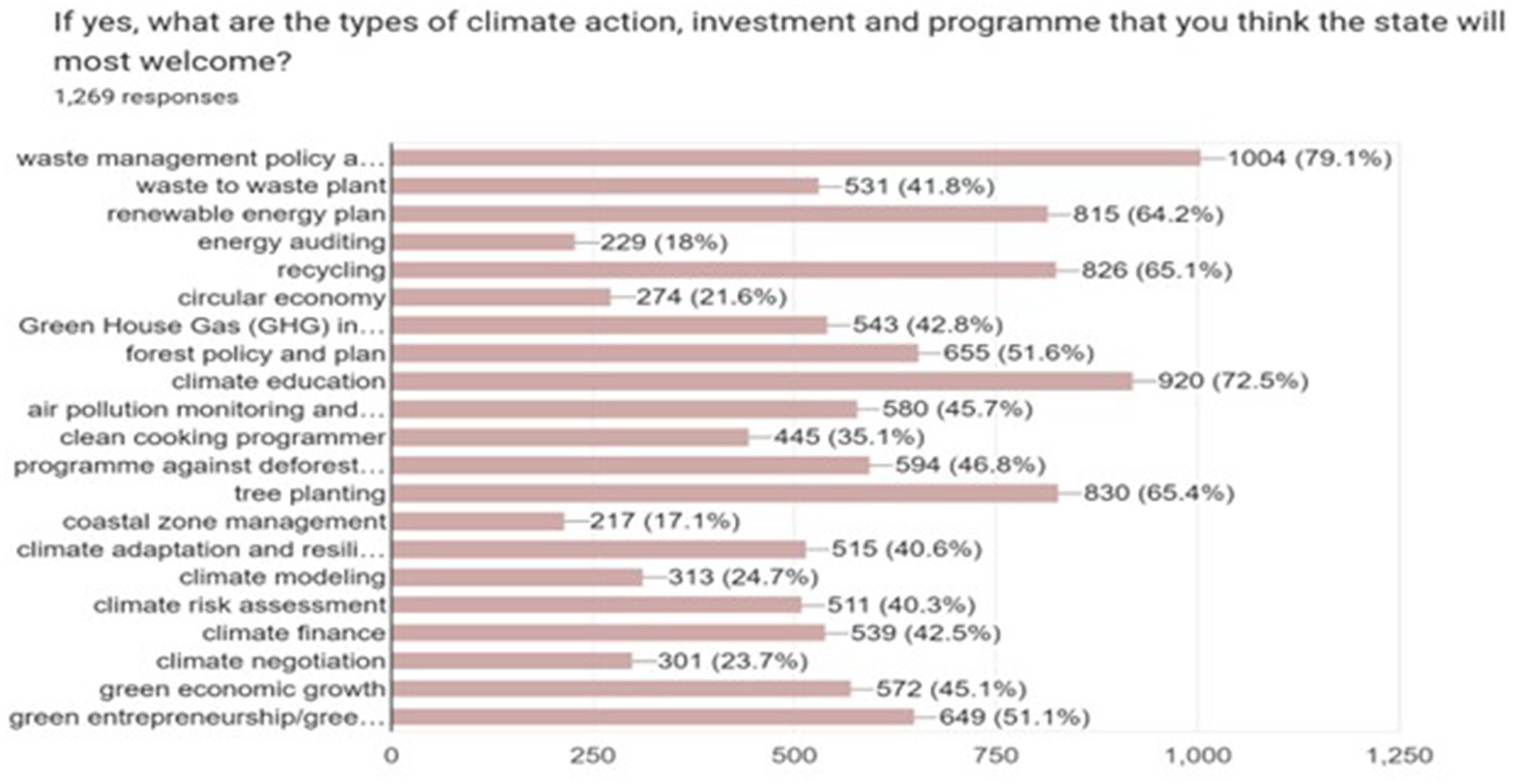

Key priority areas identified include waste management (especially waste to wealth) (79%), climate education (72%), afforestation (65%), recycling (65%), renewable energy (64%), and climate finance (43%; Figure 9). Furthermore, 26% of respondents supported the creation of a subnational environmental disclosure and rating system to monitor industrial emissions and enhance transparency. This reflects knowledge of international best practices where voluntary or mandatory environmental disclosure mechanisms serve as performance levers for local governance (Wang et al., 2004).

Survey participants and national workshop participants share the view on the need for improved communication and expedited decision-making, which was central to their suggestions. They further called for more comprehensive, “action-orientated plans” at the subnational level—ones that are both detailed and responsive to local specificities while remaining aligned with national climate aspirations. Survey results show that 92% of responds strongly agree that subnational governments need technical and financial assistance in developing and implementing climate policy, programs, and action plans (74% of respondents). Similarly workshop participants emphasized that financial support for subnational climate programs and green investments is not merely desirable but constitute a structural imperative for effective multilevel climate governance in Nigeria. Over again it was reiterated that subnational governments lack the fiscal autonomy, technical capacity and the institutional frameworks necessary to design and implement robust climate initiatives. Targeted interventions are essential not only to strengthen programmatic development and investment pipelines but also to embed those within coherent national frameworks.

Another main governance innovation advanced during the workshop and by expert interviewees was to institute an environmental information and disclosure system at the subnational level as a means of stimulating a race to the top, rewarding exemplary practice and shaming the laggards. It was consistently emphasized that in the absence of strong political will and adequate capacity to enforce regulation, information disclosure in the form of ratings and rankings could be a major key to unlocking climate action at the subnational level. Participants noted that proliferation and seeming effectiveness of similar initiatives globally including in developing countries where pollution intensive economic activities are rated and information divulged as either voluntarily or mandated by law (Wang et al., 2004; Clarkson et al., 2013; Boatemaa Darko-Mensah and Okereke, 2013; Situ and Tilt, 2018; Alhaj and Mansor, 2019).

There was also a strong call to integrate local communities into subnational climate governance. It was noted that some states such as Lagos, Ebonyi, Taraba, and Gombe, had already demonstrated that climate governance can be more effective when local realities and community are allowed to drive policy design and implementation. Our work did not delve into the role of local governments which is the third and frequently the most neglected tier of governance structure in Nigeria. However, it was noted that Lagos State, for instance, combined institutional commitment, strategic planning, and engagement with local government and communities to create a climate governance model that aims to address both mitigation and adaptation. Through its Climate Adaptation and Resilience Plan (LCARP) and partnerships with the private sector, Lagos was deemed to have shown that state-led initiatives can complement federal policies while filling gaps left by top-down approaches.

5 Discussion and policy implications

The global shift toward multilevel climate governance and implementation has highlighted subnational governments as indispensable agents in the efforts to achieve national and international climate targets. Climate action in the contemporary era is inherently multi-scalar, involving overlapping jurisdictions, transboundary risks, and shared responsibilities. However, this study reveals that subnational climate governance in Nigeria remains structurally weak, institutionally fragmented, and politically constrained. While national-level instruments such as the Climate Change Act, the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), and the Energy Transition Plan (ETP) reflect considerable ambition, their uptake by subnational (state) actors has been largely tokenistic. This persistent gap echoes Agrawal (2008) observation that policy diffusion in federated systems, especially in developing countries, is often rhetorical and fails to yield meaningful outcomes on the ground. To strengthen the analytical insights of this study, this discussion is organized around four interrelated themes: institutional capacity and coherence, climate knowledge and legitimacy, finance an elite capture; and governance innovations and pathways forward.

5.1 Institutional capacity and coherence

The analysis shows that most Nigerian states lack comprehensive climate action plans or operate with fragmented strategies scattered across sectoral lines. Where policies exist, they are seldom aligned with national frameworks such as the NDC or the ETP. This condition reflects broader governance weakness in Nigeria where incoherent, incoherent mandates, overlapping jurisdictions, and limited inter-agency coordination undermine the effectiveness of public policy (Koblowsky and Ifejika-Speranza, 2012; Okafor et al., 2024). In multilevel governance (MLG) terms, this reveals a structural deficit in vertical coordination between federal and state governments. Rather than providing consistent guidance and harmonized standards federal organs have focuses on horizontal coordination at the national level, leaving states without templates or benchmarks for action.

Comparatively, federations such as India have attempted to address this by requiring state-level climate action plans under a national framework (Jörgensen et al., 2015b; Jogesh and Paul, 2020) while Brazil’s Amazonian states have developed jurisdiction-specific policies that are formally linked to federal climate and deforestation goals (DiGiano et al., 2020). The absence of such tools and mechanism in Nigeria is a constraint on effective multilevel governance of climate change and has resulted in disparities in ambition and implementation across states. Lack of institutional capacity is also manifest in the weakness of institutional processes, procedure needed to foster inter-agency coordination, policy integration, collaboration and feedback from private, CSO and community level actors.

5.2 Climate knowledge and legitimacy

The survey results reveal a low level of climate literacy among civil servants and uneven awareness among the public, with especially stark deficit in northern states. These disparities are significantly associated with educational attainment levels, echoing earlier findings by Odjugo (2013), Azeez et al. (2024) and Ogunji et al. (2025), which tend to indicate that a general higher level of education correlates with higher awareness and engagement with environmental issues. In governance terms, limited knowledge and awareness is not just a technical issue; it also weakness the legitimacy and sustainability of climate policies. Without an informed and engaged citizenry, climate policies struggle to gain legitimacy and public ownership, which in turn undermines participatory governance and the long-term effectiveness of adaptation strategies. The literature suggests that without broad-based awareness and participation, climate policy risks being elite-driven, symbolic, and short-lived (Odjugo, 2013; Nkiaka et al., 2017). In contrast, a good example exists in South Africa where public engagement and awareness campaigns in the provinces such as KwaZulu-Natal led to the securing of strong legitimacy provincial climate strategies.

In addition, our work shows that securing political buy-in from Nigerian states and citizens requires framing climate action as complementary to core development goals, such as poverty reduction and infrastructure development. Lagos, for instance, has linked its Climate Action Plan to urban development and private investment, and Taraba frame renewable energy initiatives as tools for rural electrification and livelihoods. Embedding sustainable development objectives into climate project and plans and linking it to financing opportunities reduces the perception of trade-offs, while incentives such as performance-based grants and recognition schemes, alongside coalitions of political and community leaders, can strengthen ownership and commitment (Avellaneda and Bello-Gómez, 2024).

5.3 Finance and elite capture

The research found that lack of finance constitutes a major critical barrier in fostering subnational climate action in Nigeria. While national-level climate finance channels have improved, they are poorly aligned with subnational needs and capacities. Only a handful of states have a dedicated line for climate change and even these remain modest and fragmented. Often, climate-related expenditures are buried within general environmental budgets, blurring the lines of accountability and diluting the strategic intent of climate spending. In most cases, elites with vested interests determine the climate action implemented, pulling it toward divergent ends. This reinforces Xu (2021) argument that elite capture and distributive politics in federated systems often result in inequitable access to climate finance, hence undermining multilevel governance. As Olajide (2022) notes, such conditions foster rent-seeking behavior and institutional opacity, which further erode public trust in governance systems.

Limited and fragmented climate finance is not peculiar to Nigeria. Comparable challenges are observed in Mexico and Indonesia where decentralization has provided uneven fiscal capacity across subnational units, leading to fragmented or symbolic climate programs (Wilder and Romero Lankao, 2006; Valenzuela, 2014; Sulistiawati and Rembeth, 2025). For Nigeria increasing earmarked fiscal transfers and creating transparent, performance-based funding mechanisms will be critical to overcoming these distortions.

5.4 Governance innovations and pathways forward

Despite these challenges the study highlights potential innovations that could transform Nigeria’s subnational climate governance landscape. Chief among these is the proposal for environmental/climate disclosure and rating system at the state level. By incentivizing competition, rewarding good practice and shamming laggards, such systems can stimulate a “race to the top,” even in context of weak enforcement capacity (Wang et al., 2004; Alhaj and Mansor, 2019). Importantly this approach aligns with global best practices and can be adapted to Nigeria’s institutional realities. Subnational climate rating, ranking and disclosure initiatives could serve as transparency-enhancing tools by tracking emissions and climate actions at both the subnational and industrial levels. In addition to increasing accountability and public engagement, such mechanisms could help synchronize local and national greenhouse gas (GHG) inventories, thereby improving Nigeria’s overall reporting under the Enhanced Transparency Framework of the Paris Agreement. However, their effectiveness is currently limited by the absence of robust and standardized policy criteria at the subnational level.

Equally significant is the potential of hybrid governance models that combine federal guidance, subnational experimentation and private sector partnerships. Federal institutions can provide overarching legal and reporting framework consistent with the Paris Agreement, while states tailor interventions to local realities—such as desertification in the North, flooding in the East and costal erosion in the Niger Delta. Private sector actors complement these efforts by financing green infrastructure, supporting standardized reporting, and introducing accountability mechanisms. Together, this hybrid model balances national coherence with local experimentation, fostering a multilevel governance system that avoids fragmentation and accelerates climate action. Examples from Lagos (urban resilience and transport reform) and Taraba (renewable energy for rural electrification) show that context-sensitive innovation is possible when climate action is framed as complementary to core development objective.

6 Conclusion

This study has presented the first systematic assessment of climate awareness, policy and action across Nigeria’s 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory. The findings reveal that while Nigeria has articulated ambitious climate commitments o through its Climate Change Act, NDCs and Energy Transition Pans—these have not meaningfully diffused to the subnational (state) level. Instead state-level climate governance remains fragmented, underfunded and constrained by limited institutional capacity, weak vertical coordination, and entrenched political dynamics.

Yet, subnational governments are indispensable for Nigeria’s climate transitions. They have jurisdiction over agriculture, water, land use, waste management, urban planning and infrastructure – some of the very sectors that determine resilience and emission trajectories. Without an empowered, capable and accountable state government, Nigeria’s net-zero pledge for 2060 will remain aspirational rather than achievable.

The evidence points to five urgent priorities: (i) harmonizing policy frameworks through standardized templates and state climate plans; (ii) investing in civil service and institutional capacity; (iii) ensuring transparent and predictable fiscal transfers for climate action; (iv) embedding civil engagement and climate literacy to build legitimacy; and (v) advancing governance innovations such as climate disclosure rating and ranking as well as hybrid federal -state-private sector partnerships.

Nigeria presents a critical test case for advancing the theory and practice of MLG in the Global South. The country illustrates both the risk of rhetorical decentralization and the opportunities for institutional innovations when climate governance is linked to broader development goals. Only be recalibrating governance structures to empower subnational actors can Nigeria move from symbolic commitments to substantive and decisive climate action that will help the country build climate resilience an contribute to global climate goals.

Given this interest in multipronged strategy, a hybrid governance models that combine federal guidance, subnational innovation, and private sector partnerships offer a coherent yet flexible pathway for Nigeria’s climate governance.

Effective decentralization must also be accompanied by capacity development. As Hsu et al. (2017) caution, devolution without technical and institutional capacity leads to policy fragmentation and governance inefficiency. State governments must be supported to develop internal systems for project preparation, climate finance absorption, and monitoring and evaluation.

Despite their proximity to vulnerable populations and their jurisdiction over key sectors such as agriculture, water, and local infrastructure, their potential contributions are constrained by limited capacity, fragmented mandates, and entrenched clientelism.

This study highlights that building a multisectoral, multilevel governance system is not a matter of political choice but an institutional necessity. Achieving coherence between national goals and subnational realities requires distributed decision-making, clear responsibilities, and approaches sensitive to local contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Olukayode Oladipo, University of Lagos. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CO: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SO: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft. TO: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Visualization, Data curation, Validation. GO: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The European Climate Foundation through Grant reference number G-2401-67638 provided funding to the Society for Planet and Prosperity, Nigeria which enabled this research and publication.

Acknowledgments

The support of Mr Elochukwu Anieze with data curation and the graphic designs including the creation of tables, figures and charts is highly appreciated.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2025.1650172/full#supplementary-material

References

Adil, L., Eckstein, D., Künzel, V., and Schäfer, L. (2025), Climate risk Index 2025: Impacts of Extreme Weather Events Policy Commons Available online at: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/82rdkn7 (Accessed 14 September, 2025).

Afolabi, T. E. (2020). The role of international, national and sub-national policies in sustainable forest management and climate change in Nigeria: a case study of Cross River State (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia).

Agrawal, A. (2008). The role of local institutions in adaptation to climate change (Vol. 17, p. 28274). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Alhaj, A., and Mansor, N. (2019). Sustainability disclosure on environmental reporting: a review of literature in developing countries. American Based Res. J. 8, 1–13.

Amundsen, H., Berglund, F., and Westskog, H. (2010). Overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation—a question of multilevel governance?. Environ. Plann. C Gov. Policy. 28, 276–289.

Avellaneda, C. N., and Bello-Gómez, R. A. (2024). Introduction to the Handbook on Subnational Governments and Governance. In Handbook on Subnational Governments and Governance (pp. xi–xxii). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Azare, I. M., Abdullahi, M. S., Adebayo, A. A., Dantata, I. J., and Duala, T. (2020). Deforestation, desert encroachment, climate change and agricultural production in the Sudano-Sahelian region of Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 24, 127–132. doi: 10.4314/jasem.v24i1.18

Azeez, R. O., Rampedi, I. T., Ifegbesan, A. P., and Ogunyemi, B. (2024). Geo-demographics and source of information as determinants of climate change consciousness among citizens in African countries. Heliyon 10:e27872. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27872

Betsill, M. M., and Bulkeley, H. (2006). Cities and the multilevel governance of global climate change. Glob. Gov. 12, 141–160. doi: 10.1163/19426720-01202004

Biesbroek, R., Peters, B. G., and Tosun, J. (2018). Public bureaucracy and climate change adaptation. Rev. Policy Res. 35, 776–791. doi: 10.1111/ropr.12316

Boatemaa Darko-Mensah, A., and Okereke, C. (2013). Can environmental performance rating programmes succeed in Africa? An evaluation of Ghana's AKOBEN project. Manag. Environ. Qual. 24, 599–618. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-01-2012-0003

Bulkeley, H. (2010). Cities and the governing of climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 35, 229–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-072809-101747

Bulkeley, H., and Betsill, M. (2005). Rethinking sustainable cities: multilevel governance and the'urban'politics of climate change. Environ. Polit. 14, 42–63. doi: 10.1080/0964401042000310178

Clarkson, P. M., Fang, X., Li, Y., and Richardson, G. (2013). The relevance of environmental disclosures: are such disclosures incrementally informative? J. Account. Public Policy 32, 410–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2013.06.008

Carole-Anne, S., and Okereke, C. (2022). Role of SDGs in promoting Equity and Inclusion: In The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance by Global Goals?, eds S. Carole-Anne and F. Biermann. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Climate Action Tracker (2023). “Nigeria”. Available online at: http://climateactiontracker.org. (Accessed on 2025-03-07).

Di Gregorio, M., Fatorelli, L., Paavola, J., Locatelli, B., Pramova, E., Nurrochmat, D. R., et al. (2019). Multi-level governance and power in climate change policy networks. Global Environ. Change-Human Policy Dimensions 54, 64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.003

DiGiano, M., Stickler, C., and David, O. (2020). How can jurisdictional approaches to sustainability protect and enhance the rights and livelihoods of indigenous peoples and local communities? Front. For. Glob. Change 3:40. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2020.00040

Eckersley, P. (2017). A new framework for understanding subnational policy-making and local choice. Policy Stud. 38, 76–90. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2016.1188910

Federal Government of Nigeria (FGoN) (2020). National adaptation plan framework (NAPF). Nigeria: Department of Climate Change, Federal Ministry of Environment.

Fenton, P., and Gustafsson, S. (2017). Moving from high-level words to local action—governance for urban sustainability in municipalities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 26, 129–133.

Fuhr, H., Hickmann, T., and Kern, K. (2018). The role of cities in multi-level climate governance: local climate policies and the 1.5 C target. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 30, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.10.006

Gillard, R., Gouldson, A., Paavola, J., and Van Alstine, J. (2017). Can national policy blockages accelerate the development of polycentric governance? Evidence from climate change policy in the United Kingdom. Glob. Environ. Chang. 45, 174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.06.003

Guha, J., and Chakrabarti, B. (2019). Achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) through decentralisation and the role of local governments: a systematic review. Commonwealth J. Local Governance 22, 1–21. Available at: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.896493850496702

Harrison, K. (2023). “Climate governance and federalism in Canada” in Climate governance and federalism: A forum of federations comparative policy analysis. eds A. Fenna, S. Jodoin, and J. Joana Setzer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 64–85.

Heinen, D., Arlati, A., and Knieling, J. (2022). Five dimensions of climate governance: a framework for empirical research based on polycentric and multi‐level governance perspectives. Environ. Policy Gov. 32, 56–68.

Hsu, A., Weinfurter, A. J., and Xu, K. (2017). Aligning subnational climate actions for the new post-Paris climate regime. Clim. Chang. 142, 419–432. doi: 10.1007/s10584-017-1957-5

Ishtiaque, A., Eakin, H., Vij, S., Chhetri, N., Rahman, F., and Huq, S. (2021). Multilevel governance in climate change adaptation in Bangladesh: structure, processes, and power dynamics. Reg. Environ. Chang. 21, 75–90. doi: 10.1007/s10113-021-01802-1

Jogesh, A., and Paul, M. M. (2020). Ten years after: evaluating state action plans in India. Sci. Cult. 86, 38–35. doi: 10.36094/sc.v86.2020.Climate_Change.Jogesh_and_Paul.38

Jordan, A., Huitema, D., van Asselt, H., and Forster, J. (2018). Governing climate change: Polycentricity in action? 1st Edn. Cambrdige: Cambridge University Press.

Jörgensen, K., Jogesh, A., and Mishra, A. (2015a). Multi-level climate governance and the role of the subnational level. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 12, 235–245. doi: 10.1080/1943815X.2015.1096797

Jörgensen, K., Mishra, A., and Sarangi, G. K. (2015b). Multi-level climate governance in India: the role of the states in climate action planning and renewable energies. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 12, 267–283. doi: 10.1080/1943815X.2015.1093507

Kammen, D. M., Matlock, T., Pastor, M., and Pellow, D. (2021). Accelerating the timeline for climate action in California. arXiv. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2103.07801

Koblowsky, P., and Ifejika-Speranza, C. (2012). African developments: competing institutional arrangements for climate policy: the case of Nigeria (briefing paper 7/2012). German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS). Available online at: https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/BP_7.2012.pdf (accessed September 11, 2025).

Lagos State Government (2024). Lagos climate adaptation and resilience plan (LCARP). Lagos: Ministry of Environment and Water Resource.

Lee, S., Paavola, J., and Dessai, S. (2022). Towards a deeper understanding of barriers to national climate change adaptation policy: a systematic review. Clim. Risk Manag. 35:100414. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2022.100414

Masuda, H., Kawakubo, S., Okitasari, M., and Morita, K. (2022). Exploring the role of local governments as intermediaries to facilitate partnerships for the sustainable development goals. Sustain. Cities Soc. 82:103883. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2022.103883

Mazmanian, D. A., Jurewitz, J. L., and Nelson, H. T. (2020). State leadership in US climate change and energy policy: the California experience. J. Environ. Dev. 29, 51–74. doi: 10.1177/1070496519887484

Meckling, J., and Benkler, A. (2024). State capacity and varieties of climate policy. Nat. Commun. 15:9942. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-54221-1

ND-GAIN Index. (2021). https://gain-new.crc.nd.edu/country/nigeria (accessed 12 September 2025).

Nkiaka, E., Nawaz, N. R., and Lovett, J. C. (2017). Evaluating global reanalysis precipitation datasets with rain gauge measurements in the Sudano‐Sahel region: case study of the Logone catchment, Lake Chad Basin. Meteorol. Appl. 24, 9–18. doi: 10.1002/met.1600

Odjugo, P. A. O. (2013). Analysis of climate change awareness in Nigeria. Sci. Res. Essays 8, 1203–1211. doi: 10.5897/SRE11.2018

Ogunji, C. V., Rudd, J. A., Chukwu, I. N., Okereke, C., and Ogunji, J. O. (2025). Engaging a critical mass of change agents through climate action in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 1–17.

Okafor, C. C., Ajaero, C. C., Madu, C. N., Nzekwe, C. A., Otunomo, F. A., and Nixon, N. N. (2024). Climate change mitigation and adaptation in Nigeria: a review. Sustainability 16:7048. doi: 10.3390/su16167048

Okoh, A. S., and Okpanachi, E. (2023). Transcending energy transition complexities in building a carbon-neutral economy: the case of Nigeria. Cleaner Energy Systems 6, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cles.2023.100069

Olajide, B. E. (2022). An evaluation of subnational climate change response in Lagos state, Nigeria and Kwazulu Natal province, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, North-West University (South Africa).

Olaoti, S. O. (2024). Plastic pollution in Lagos State, Nigeria: Challenges and sustainable solutions. Open Environ. Res. 5, 1–15.

Orimoogunje, O., and Aniramu, O. (2025). Systematic review of flood resilience strategies in Lagos Metropolis: pathways toward the 2030 sustainable development agenda. Front. Clim. 7:1603798. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1603798

Owebor, K., Okereke, C., Diemuodeke, O. E., Owolabi, A. B., and Nwachukwu, C. O. (2025). A systematic review of literature on the decarbonization of the Nigerian power sector. Energy Sustain. Soc. 15:34. doi: 10.1186/s13705-025-00527-x

Parnell, S. (2016). Defining a global urban development agenda. World Dev. 78, 529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.028

Pierre, J., and Peters, B. G. (2020). Governing complex societies: Trajectories and scenarios. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pindiriri, C., and Kwaramba, M. (2024). Climate finance in developing countries: green budget tagging and resource mobilization. Clim. Pol. 24, 894–908. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2024.2302325

Ribeiro, T. L. (2023). Institutional outcome at the subnational level–climate commitment as a new measurement. Earth System Governance 16, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.esg.2023.100176

Scott, W. A., Rhodes, E., and Hoicka, C. (2023). Multi-level climate governance: examining impacts and interactions between national and sub-national emissions mitigation policy mixes in Canada. Clim. Pol. 23, 1004–1018. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2023.2185586

Shiru, M. S., Shahid, S., Dewan, A., Chung, E. S., Alias, N., Ahmed, K., et al. (2020). Projection of meteorological droughts in Nigeria during growing seasons under climate change scenarios. Sci. Rep. 10, 10107–10125. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67146-8

Situ, H., and Tilt, C. (2018). Mandatory? Voluntary? A discussion of corporate environmental disclosure requirements in China. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 38, 131–144. doi: 10.1080/0969160X.2018.1469423

Soto-Montes-de-Oca, G., Cruz-Bello, G. M., Quiroz-Rosas, L. E., and Flores-Gutiérrez, S. (2024). The challenge of integrating subnational governments in multilevel climate governance: the case of Mexico. Territ., Politics, Gov. 12, 1114–1133. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2022.2106298

Sulistiawati, L. Y., and Rembeth, I. A. (2025). Climate change regulations in subnational governments of the southeast Asian countries: case studies from Indonesia and the Philippines. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law, 1–28. doi: 10.1080/02646811.2024.2443307

Tanner, T., Mitchell, T., Polack, E., and Guenther, B. (2009). Urban governance for adaptation: assessing climate change resilience in ten Asian cities. IDS Working Papers, 2009, 1–47.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, [UN OCHA] (2017). Nigeria: Drought impact report 2016–2017. Abuja: UN OCHA.

Valenzuela, J. M. (2014). Climate change agenda at subnational level in Mexico: policy coordination or policy competition? Environ. Policy Gov. 24, 188–203. doi: 10.1002/eet.1638

Van der Heijden, J. (2018). “City and subnational governance: high ambitions, innovative instruments and polycentric collaborations” in Governing climate change: Polycentricity in action? eds A. Jordan, D. Huitema, H. van Asselt, and J. Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 81–96.

Van der Ven, H., Bernstein, S., and Hoffmann, M. (2017). Valuing the contributions of nonstate and subnational actors to climate governance. Global Environ. Politics 17, 1–20. doi: 10.1017/9781108284646

Wang, H., Bi, J., Wheeler, D., Wang, J., Cao, D., Lu, G., et al. (2004). Environmental performance rating and disclosure: China’s GreenWatch program. J. Environ. Manag. 71, 123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.01.007

Wilder, M., and Romero Lankao, P. (2006). Paradoxes of decentralization: water reform and social implications in Mexico. World Dev. 34, 1977–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.11.026

Keywords: climate change, climate policy, climate governance, rating and disclosure, Nigeria, multilevel governance

Citation: Okereke C, Okoh S, Ogenyi T and Olorunfemi G (2025) Assessment of climate awareness, policy development, and action across Nigerian states. Front. Clim. 7:1650172. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1650172

Edited by:

David Kasdan, Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Arnaud Zlatko Dragicevic, Chulalongkorn University, ThailandSoledad Soza, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

Copyright © 2025 Okereke, Okoh, Ogenyi and Olorunfemi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chukwumerije Okereke, Yy5va2VyZWtlQGJyaXN0b2wuYWMudWs=

Chukwumerije Okereke

Chukwumerije Okereke Sadiq Okoh

Sadiq Okoh Timothy Ogenyi

Timothy Ogenyi Gboyega Olorunfemi2

Gboyega Olorunfemi2