- 1University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

- 2Faculty of Education and Health Sciences, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

- 3Central European University Private University - CEU GmbH, Vienna, Austria

- 4BOKU Institute of Meteorology and Climatology, Vienna, Austria

This study presents a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of climate-induced migration research in the Global South (2000–2024), critically examined through the lens of climate justice. Drawing on 204 peer-reviewed publications from Scopus and Web of Science, the analysis maps scholarly production, citation patterns, thematic evolution, and global collaboration networks using Biblioshiny and VOSviewer. Results reveal a significant surge in research post-2015, with intellectual roots grounded in environmental migration, but shifting progressively toward integrated themes of climate justice, human rights, adaptation, and vulnerability. High-impact contributions remain concentrated among Global North institutions, particularly the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia, although authorships are increasingly diversifying to include regions such as South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Small Island Developing States. Thematic mapping shows a maturing field marked by convergence of legal, political, ecological, and social science perspectives. However, critical gaps persist including limited attention to under-researched geographies, destination outcomes, gendered and intersectional experiences, and understanding trapped populations and immobility. South–South collaborations remain marginal, and dominant framings often reproduce epistemic hierarchies that overlook local agency and decolonial critiques. The study identifies urgent directions for future research, including deeper interdisciplinary integration, participatory and context-sensitive methodologies, and the application of attribution science to quantify climate-related displacement. By centering equity, representation, and the differentiated impacts of climate stress, this bibliometric perspective contributes not only to mapping the landscape of climate migration scholarship but also to advancing a justice-oriented research agenda. It calls for a paradigm shift where migration is understood not merely as a risk, but as a space for resilience, rights, and transformation, particularly for the most vulnerable in the Global South.

Introduction

The core objective of this paper is to systematically examine how research on climate-induced migration in the Global South has evolved, particularly through a climate justice lens. We aim to identify knowledge gaps, thematic trends, and structural imbalances in authorship and collaboration, offering insights into the extent to which existing literature addresses issues of vulnerability, equity, and representation. To this end, we employ a bibliometric approach to assess intellectual structures, co-authorship networks, citation patterns, and thematic clusters in the field. This framing ensures that our analysis remains explicitly guided by questions of justice, knowledge asymmetries, and the lived realities of climate-vulnerable populations.

Foregrounding this aim is vital because climate-induced migration has become one of the most pressing consequences of the climate crisis. Worsening hazards, from extreme heat and drought to floods and sea-level rise, are uprooting livelihoods and forcing people to move in ever-growing numbers (Almulhim et al., 2024). In 2020 alone, over 30 million people were displaced by climate-related disasters, with Asia and the Pacific among the hardest-hit regions (IFRC, 2021). By 2050, climate impacts could internally displace about 143 million people in the Global South, including ~86 million in Sub-Saharan Africa, 40 million in South Asia, and 17 million in Latin America (Baldwin, 2017; Barrios et al., 2006). These projections confirm that climate-induced migration is not a distant scenario but an unfolding reality threatening lives, stability, and development across vulnerable regions.

A climate justice perspective highlights why this subject demands urgent scholarly and policy attention. Those most vulnerable to climate change, often low-income communities in the Global South, have contributed least to the greenhouse gas emissions that drive it (Arruda Filho et al., 2024). For example, Africa produces only a fraction of global emissions yet faces some of the most severe impacts. Climate justice reframes migration not simply as an environmental or humanitarian challenge but as a matter of fairness, ethics, and human rights. It emphasizes the responsibility of major polluters and the international community to support those forced to move, through adaptation assistance, legal recognition of climate-displaced persons, and mechanisms like loss-and-damage compensation. This aligns with global policy frameworks such as Sustainable Development Goal 10, which calls for safe and responsible migration, a target jeopardized by unchecked climate extremes.

Defining climate-induced migration

“Climate-induced migration” refers to human mobility triggered primarily by climate change and related environmental hazards. It encompasses sudden displacement (e.g., fleeing floods or cyclones), planned relocation, and gradual out-migration from areas rendered uninhabitable by slow-onset changes such as drought or sea-level rise. Climate is rarely the sole cause; rather, it interacts with economic, social, and political drivers (Priovashini and Mallick, 2022). Black et al. (2013) highlight that environmental stress is one among many factors shaping migration decisions.

Scholarship increasingly rejects simplistic “climate refugee” narratives and instead distinguishes between voluntary migration, forced displacement, and immobility or “trapped” populations. Migration may be proactive, such as seasonal rural-to-urban movements, whereas displacement implies limited choice, and immobility reflects households unable to move due to poverty or legal barriers. These distinctions recognize both vulnerability and agency, highlighting migration as a potential form of adaptation if supported through policy and resources. Indeed, frameworks such as migration as adaptation suggest that planned, facilitated mobility can be a strategy for adjusting to climate stress rather than a failure of coping (Black et al., 2013).

Critical scholarship also warns against securitized framings that portray climate migrants as threats (McLeman, 2018). Such perspectives risk reinforcing border control rather than protection. Instead, a human security approach emphasizes dignity, safety, and agency. Overall, climate-induced migration is best understood as part of a continuum of mobility shaped by complex socio-political contexts.

Climate justice and migration

Climate justice is rooted in the principle that those least responsible for climate change often face its gravest consequences. It demands equitable sharing of burdens and responsibilities (Arruda Filho et al., 2024). Within migration scholarship, justice has distributive, procedural, recognition, and reparative dimensions. Distributive justice calls for fair allocation of adaptation resources and loss-and-damage compensation; procedural justice emphasizes inclusive decision-making in relocation; recognition justice stresses valuing marginalized knowledge and voices; and reparative justice addresses historical responsibilities for displacement.

At the global scale, climate justice highlights the North–South paradox: wealthy nations have historically emitted the bulk of greenhouse gases, while poorer countries bear disproportionate vulnerability (Roberts and Parks, 2006; Sultana, 2022). Small island states and least-developed countries contribute little to emissions yet face existential risks from rising seas and storms. This confers moral obligations on high-emitting countries to finance adaptation, reduce emissions, and support displaced communities.

Climate justice also operates at national and local levels, where marginalized groups within societies are hardest hit and least able to adapt. The IPCC (2022) acknowledges that “ongoing impacts of colonization” undermine adaptive capacity, linking historical injustices to present vulnerabilities (Morrison et al., 2023). In contexts such as the Pacific Islands, postcolonial critiques explicitly connect legacies of marginalization with heightened climate risks.

Applied to migration, a justice lens shifts the focus beyond numbers of displaced persons to questions of rights, responsibilities, and agency. It asks whether climate migrants are protected under international law (they currently lack a formal legal category), whether communities participate in relocation decisions, and whether adaptation funds reach those most vulnerable. This framing critiques Global North securitization discourses that prioritize border protection, contrasting them with Global South calls for mobility support and equitable adaptation.

Epistemic justice is equally critical. Bibliometric asymmetries—including Global North–dominated authorship and limited South–South collaboration—influence which diagnoses and remedies are considered legitimate (Parsons et al., 2024). Unless countered by co-production, inclusive citation practices, and Southern institutional empowerment, research risks reproducing colonial hierarchies of knowledge (Sultana, 2022).

Rationale and contribution

Against this backdrop, our study is motivated by the need to systematically evaluate the state of research on climate-induced migration in the Global South through a bibliometric lens. While the concept has gained traction in academic and policy circles, research output remains skewed toward Global North institutions, often marginalizing Southern voices and priorities (Chakrabarti, 2023). This imbalance obscures the lived realities of climate-vulnerable populations in the Global South and risks reinforcing inequitable policy agendas.

A bibliometric approach enables a rigorous, transparent, and replicable mapping of the field. It allows us to identify thematic clusters, collaboration networks, and citation patterns while assessing whether the literature incorporates principles of climate justice. Specifically, our analysis traces how migration is framed, who produces knowledge, and how Southern research is positioned in global discourse (Arruda Filho et al., 2024; Anjum and Aziz, 2025a; Donthu et al., 2021).

Research questions

This paper is guided by three interrelated questions:

1. How has the academic literature on climate-induced migration in the Global South evolved over time, and what thematic trends can be identified?

2. What structural imbalances exist in terms of authorship, collaboration, and knowledge production, particularly between Global North and Global South institutions?

3. To what extent does the literature engage with principles of climate justice—distributive, procedural, recognition, and reparative, in framing migration?

By systematically addressing these questions, this study contributes to efforts to decolonize climate research and foreground justice in the study of climate-induced migration.

Materials and methods

Bibliometric analysis has been fundamental in mapping key themes, citation networks, and interdisciplinary collaborations (Kumar, 2025). Though bibliometric analysis is widely recognized and a powerful research tool that quantitatively analyzes academic literature, its application in the climate migration domain is limited. Nonetheless, bibliometric analysis is essential for evaluating research landscapes, gaps and driving trends (Saeid et al., 2025), emerging areas (Donthu et al., 2021), and research hubs (Carrascal-Hernández et al., 2025), including in the context of climate justice (Anjum and Aziz, 2025a).

Since bibliometric analysis follows a systematic and structured approach (Passas, 2024), this study adheres to established research protocols to ensure rigor and reproducibility. The combination of Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) datasets is used in the data analysis. Both are widely used datasets in bibliometric analysis due to their comprehensive, rigorous quality, indexing of peer-reviewed literature, citation tracking capabilities, and analytical tools (Arsova et al., 2022; Kumpulainen and Seppänen, 2022). While WoS dataset is based on selectivity, Scopus offers comprehensive data. The integration of both enhances the reliability of bibliometric studies, and our study integrates both datasets.

Data analysis and visualization

WoS and Scopus have different index coverages, and they store information differently, which leads to potential biases (Kumpulainen and Seppänen, 2022) inconsistencies while merging. Consequently, researchers employ different methodological approaches to counter missing data and duplicate records. For data analysis, researchers have used the open source Bibliometric package of R (Biblioshiny) (Wei and Jiang, 2023), VOSviewer (Kirby, 2023), CiteSpace (Zhang et al., 2023), SciMAT (Cobo et al., 2012), ScientoPy (Ruiz-Rosero et al., 2019). However, most of these software requires professional skills and specialized expertise to operate effectively. To address this, recently, (Caputo and Kargina, 2022) presented a user-friendly method to merge Scopus and WoS data with the R package in Biblioshiny. We follow the guide provided by Caputo and Kargina (2022) for merging the datasets in Biblioshiny.

Biblioshiny is a web-based visual analysis tool built on the Bibliometrix package in R Studio, which is designed for bibliometric data processing and analysis. We employed Biblioshiny 2.0 for data analysis (Aria and Cuccurullo, 2017) and VOSviewer for visualization to map co-citation networks, keyword occurrence, and citation analysis of countries.

Operational definition of Global South: In this study we conceptualize the Global South primarily as a politico-economic and epistemic category denoting states historically positioned at the periphery of global power and knowledge production, rather than a strictly geographic bloc. Consistent with UN usage and contemporary scholarship, we operationalize the Global South as G77 + China (134 states) for search and inclusion purposes, aligning our queries to the House of Commons Library country list used in the data extraction (Annex 1). This approach recognizes substantial internal heterogeneity (e.g., lower-income small island states vs. large emerging economies) and guards against essentialism by treating the Global South as a relational construct whose boundaries and coalitions shift across policy arenas and scholarly fields (Bull and Banik, 2025; Mazzega et al., 2025). We therefore interpret bibliometric patterns with caution, emphasizing how geopolitical position and epistemic hierarchies shape visibility, authorship, and citation dynamics.

Eligibility criteria and screening

A list of 134 Global South countries was obtained from House of Commons Library to guide the data extraction process. The following criteria keywords, “climate migration*” OR “environmental migration*” OR “climate-induced migration*” OR “climate displacement*” OR “environmental displacement*” OR “climate refugee*” were combined with the list of the Global South countries to retrieve the scientific data on climate-induced migration from 2000 to 2024 (see Annex 1). The variation among keywords was maintained by using asterisk (*) after each keyword. For instance, “climate migration*” results in “climate migration” and “climate migrations” (WoS Help, 2020). The search was conducted on March 05, 2025.

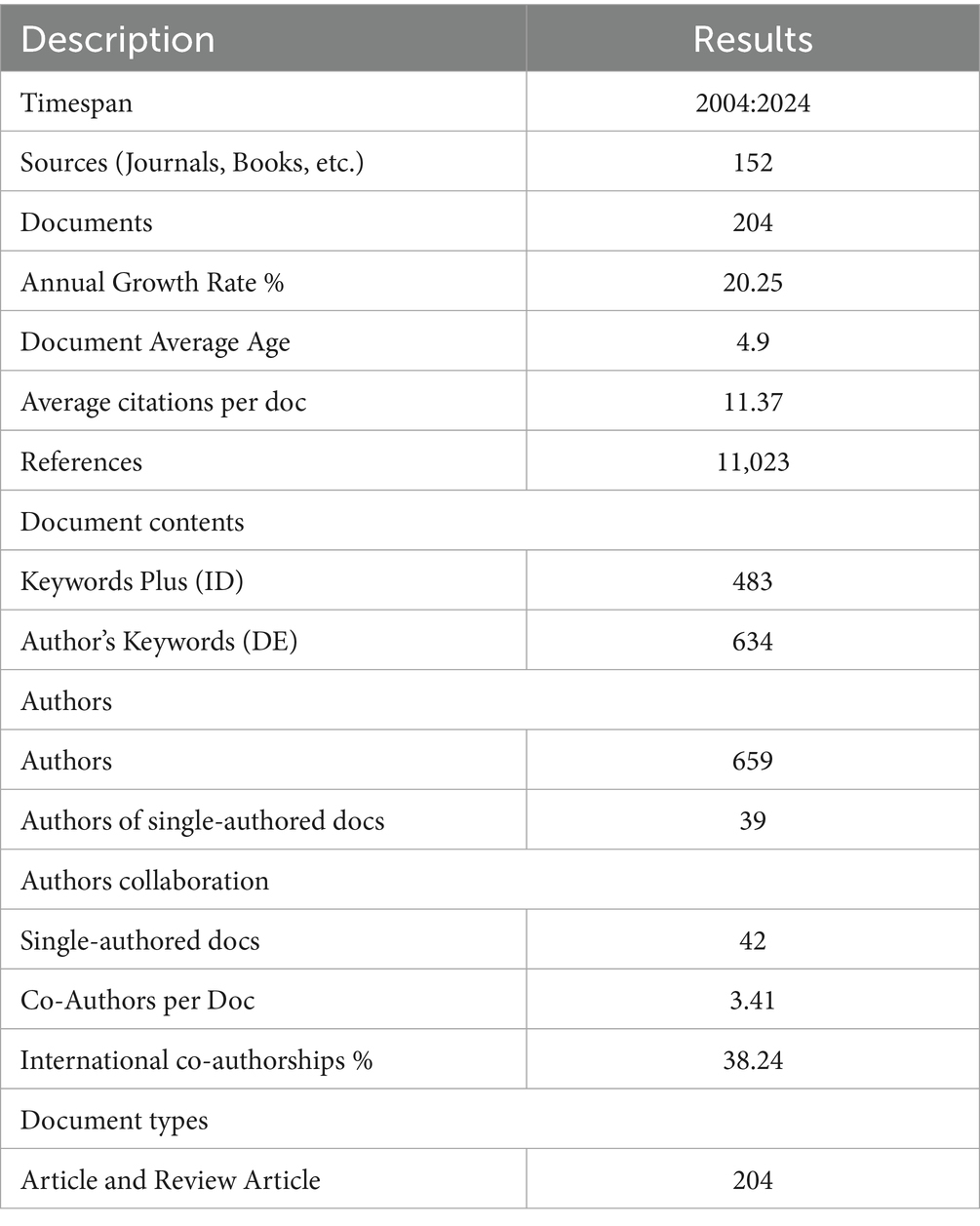

Although the search was designed to focus on climate-induced migration in the Global South; however, the results include documents from both the Global North and the Global South institutions. It is due to the global significance of climate migration, the role of international research collaborations, and the fact that researchers in the Global North contribute to policy frameworks, legal debates, and destination analyses. Lastly, the indexing bias of bibliographic databases contributes to the visibility of research from well-established academic institutions, regardless of study location (Table 1).

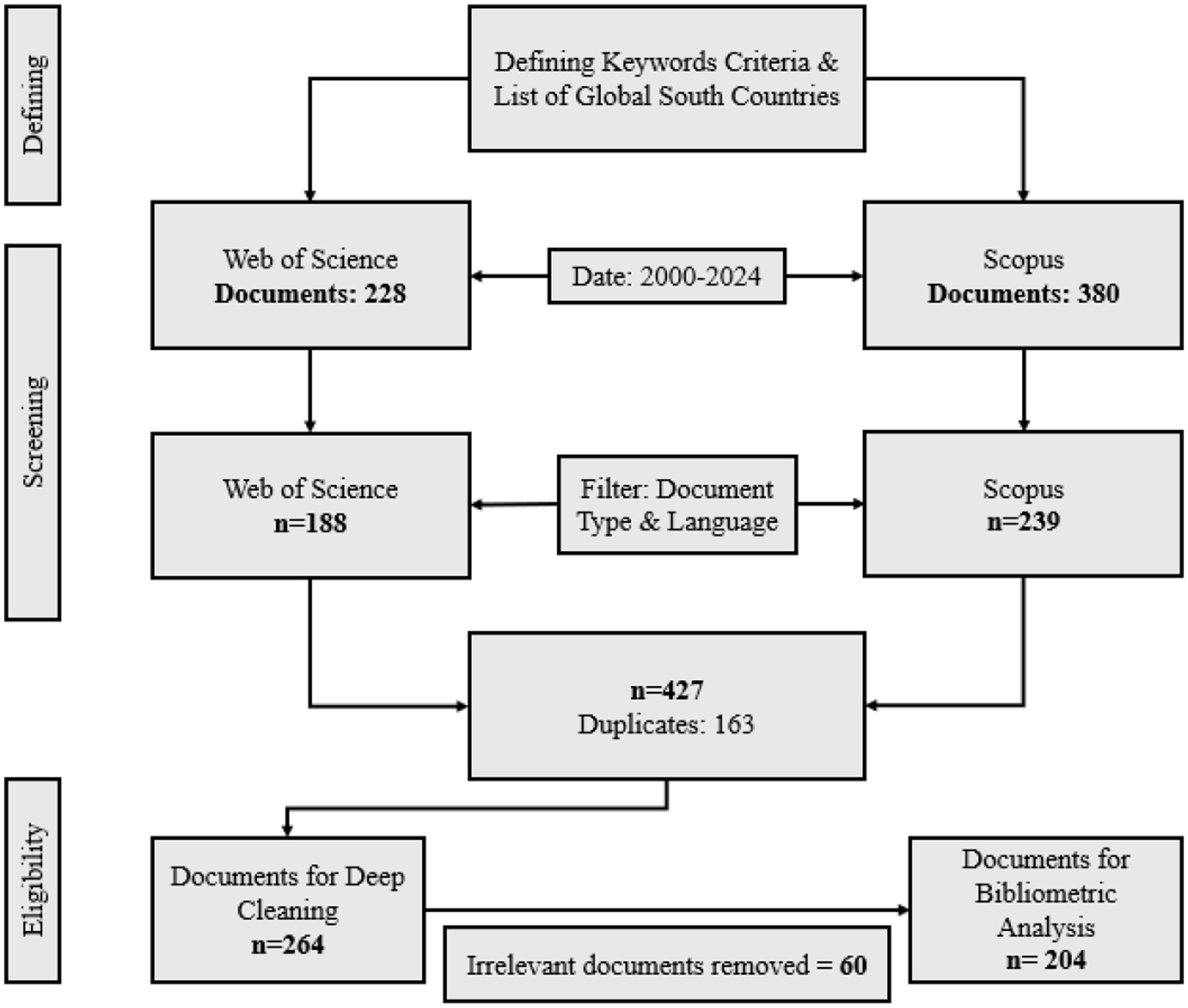

After defining the search keywords, a query was formulated and fed into WoS, and it returned 228 documents. Following document type and language filters, only articles and review articles published in English were retained, as they undergo rigorous quality control processes (Milán-García et al., 2021). In the end, a BibTeX file with 188 documents was downloaded. For Scopus, the initial search yielded 380 documents. After applying similar filters, 239 articles were downloaded in BibTeX format.

The WoS (BibTeX) and Scopus (BibTeX) files were uploaded to Biblioshiny as raw datasets, from which Excel files (WOS.xlsx and Scopus.xlsx) were extracted. These files were manually merged within Excel, and 163 duplicate records were removed. The resulting dataset of 264 articles was subjected to further manual screening (Figure 1).

A thorough revision was conducted to remove any irrelevant articles, leading to the removal of 60 documents. These articles appeared in the list as they used some keywords but were not directly relevant to climate-induced migration. In the end, an Excel file with 204 documents was fed into Biblioshiny, for analysis and a “.csv” file for VOSviewer to facilitate network visualization.

We include all peer-reviewed studies that focus on climate-induced migration in Global South regions, regardless of the author’s institutional affiliation. This allows us to analyze who is producing knowledge on Global South contexts, what the dominant themes are, and how climate justice framings are integrated.

We screened both titles and abstracts to determine relevance. Only English-language peer-reviewed articles and reviews were included, which introduces a language bias. Moreover, our keyword strategy may have excluded papers that do not explicitly use terms like ‘climate migration’ or omit country names in titles/abstracts. We acknowledge that key literature on immobility, stepwise migration, and internal displacements may be underrepresented due to these constraints. We reflect on these limitations in our discussion.

Our dataset consists of 204 documents that come from 152 sources and include 659 authors. The annual growth rate of publication was 20.25%. Notably, only 42 documents were authored by a single researcher which indicates a strong trend toward collaborative research. The dataset includes 634 author keywords which encapsulate a wide range of topics within climate-induced migration. The earliest publication in the dataset dates back to 2004, and 40 articles were published in 2024. Although the publication frequency remained relatively gradual until 2012, a substantial growth has been observed since 2017.

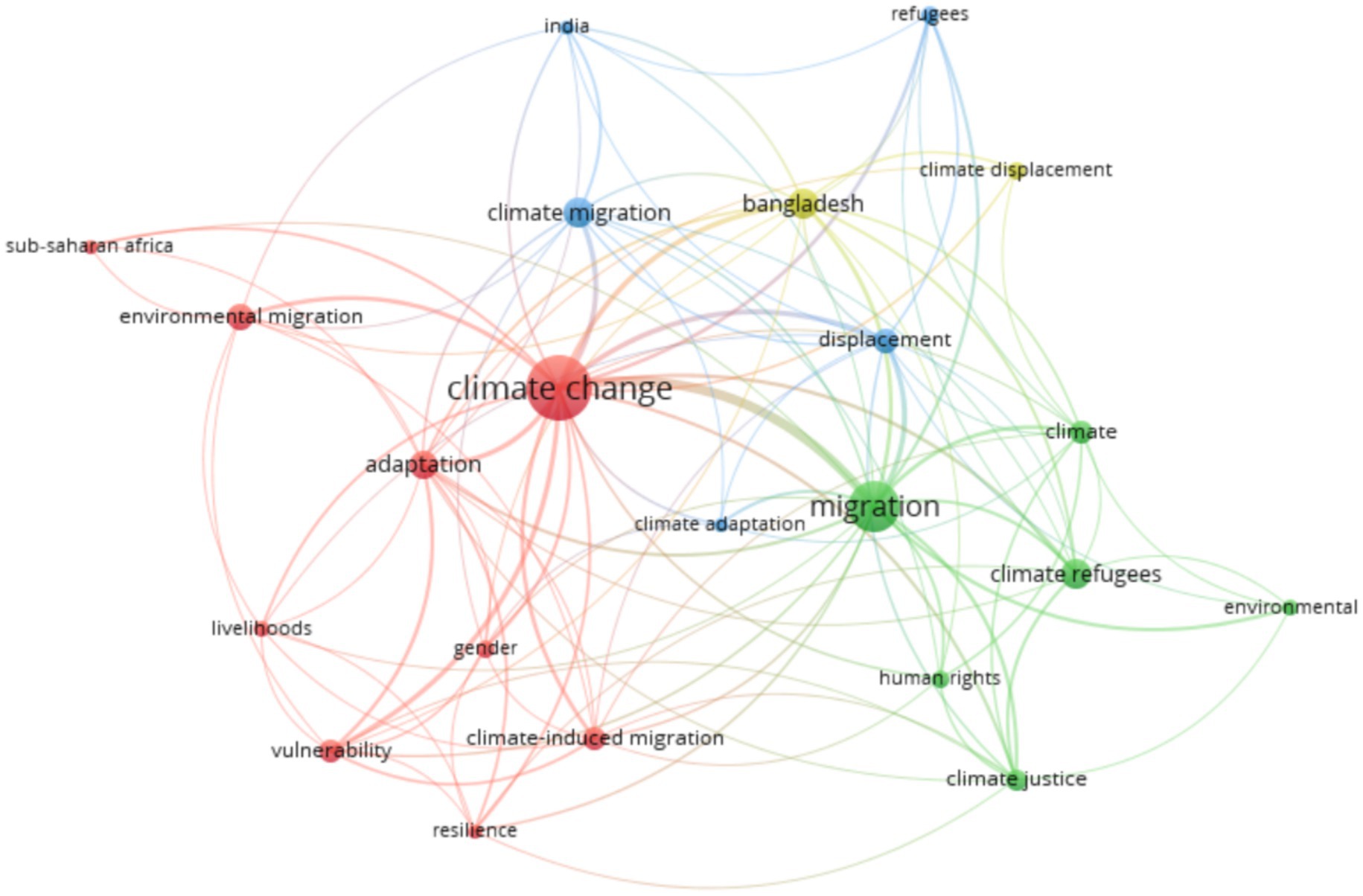

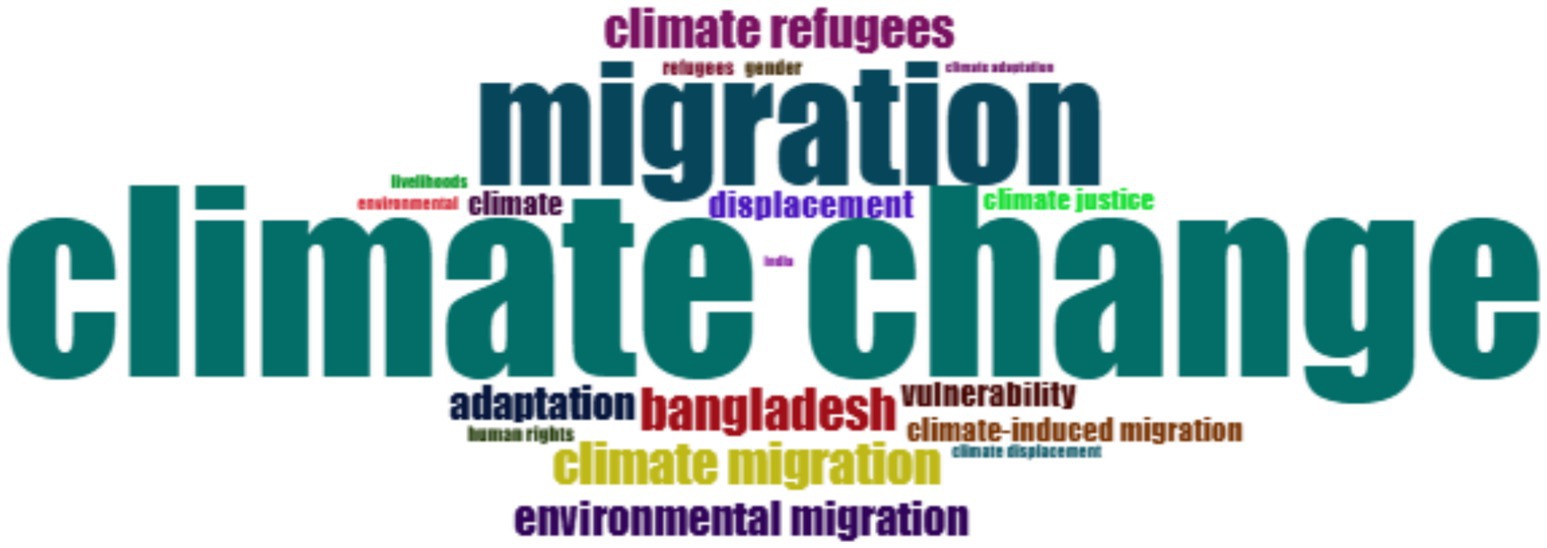

While our initial search strategy prioritized migration-related terms combined with Global South country names, we intentionally did not restrict the search to include justice-related keywords. This decision was made to avoid excluding migration studies that engage with justice implicitly, through themes of vulnerability, adaptation, gender, or human rights, even if “justice” was not an explicit keyword. Importantly, our bibliometric analysis revealed that justice-related concepts emerged strongly in the dataset itself, as seen in the co-occurrence clusters (Figure 2; Table 2) where climate justice, human rights, and gender featured prominently. This confirms that the justice–migration nexus is empirically represented in the literature we analyzed, even without front-loading justice terms in the search query.

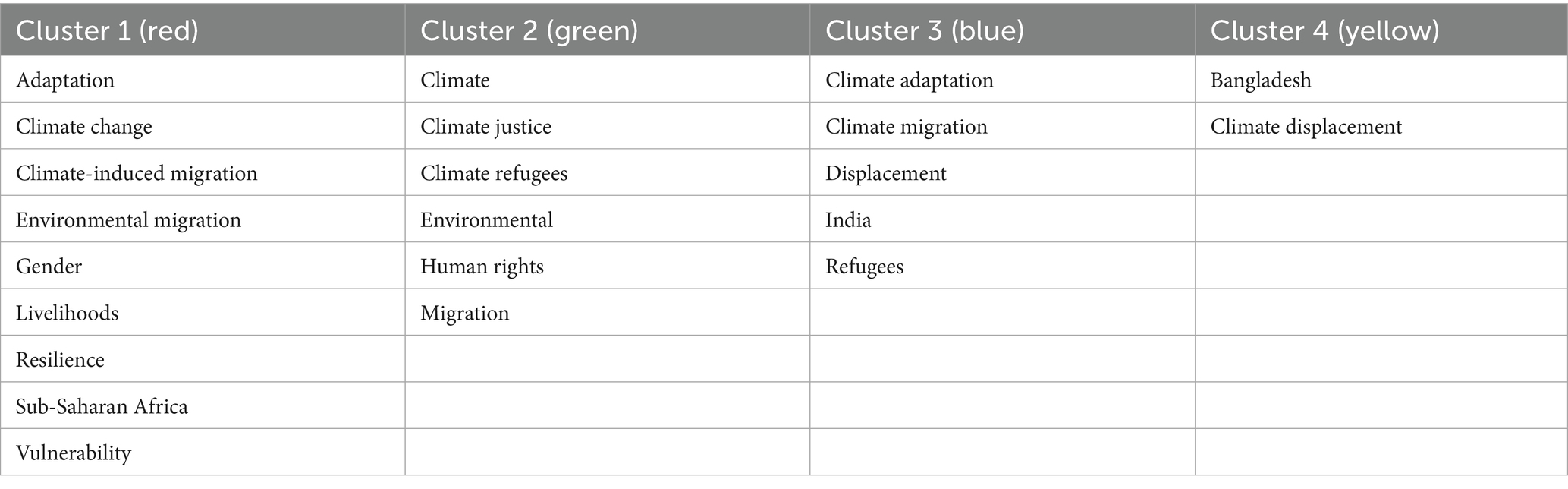

Author keywords provide a structured way to identify research patterns, thematic evolution, and the intellectual structure of a field in bibliometric analysis. Keywords are also useful in indexing and categorizing research and conveying the topics of articles (Pearson, 2024). Figure 2 shows the co-occurrence of author keywords from 2000 to 2024 for 204 documents. For 682 keywords, minimum occurrence criteria were set to 5 and 22 keywords met the threshold. In result we get the mostly used author keywords in climate-induced migration research. Authors’ keywords are grouped into four main clusters. The color of the clusters reflects the strength of relationships among keywords, while the size of the nodes represents how frequently a keyword appears. The lines between nodes indicate connections between them. Figure 2 shows the co-occurrence of author keywords from 2000 to 2024 across 204 documents. The network reveals four distinct clusters: (1) climate change, adaptation, vulnerability, and livelihoods; (2) climate justice, human rights, gender, and refugees; (3) displacement, environmental migration, and India; and (4) climate-induced migration and regional foci such as Bangladesh and Sub-Saharan Africa. Notably, the presence of climate justice, human rights, and gender as central nodes confirms that justice-oriented perspectives are empirically embedded in the literature, even though our search terms did not pre-filter for “justice.” This validates the study’s focus on the nexus of climate justice and climate-induced migration, demonstrating how normative, rights-based, and equity-focused framings have increasingly shaped the intellectual structure of the field since 2015.

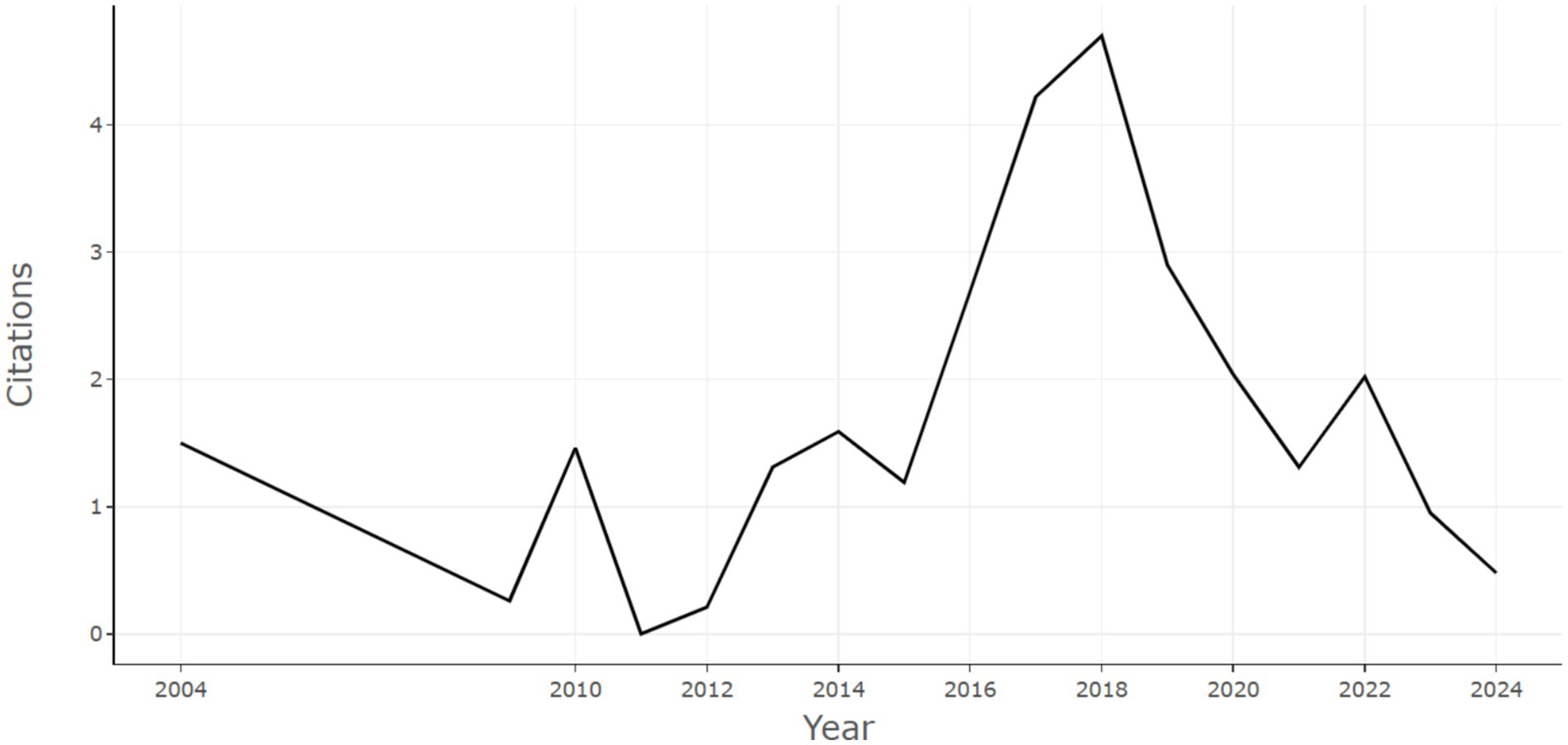

Figure 3 illustrates the average number of citations per document from 2004 to 2024. Citations increased steadily after 2012 and reached a peak around 2018. However, this was followed by a gradual decline, as indicated by the downward trend. This also shows that newer publications have yet to accumulate citations. During the peak in 2018, there were 4.70 total citations, which has reduced to 0.48 in 2024. The post-2018 decline reflects citation lag rather than waning interest; importantly, it also flags enduring citation inequities, newer Global South scholarship published since 2020 has had less time and fewer channels to accrue recognition, a phenomenon central to epistemic justice debates.” (cf. Donthu et al., 2021; see also our discussion of asymmetries).

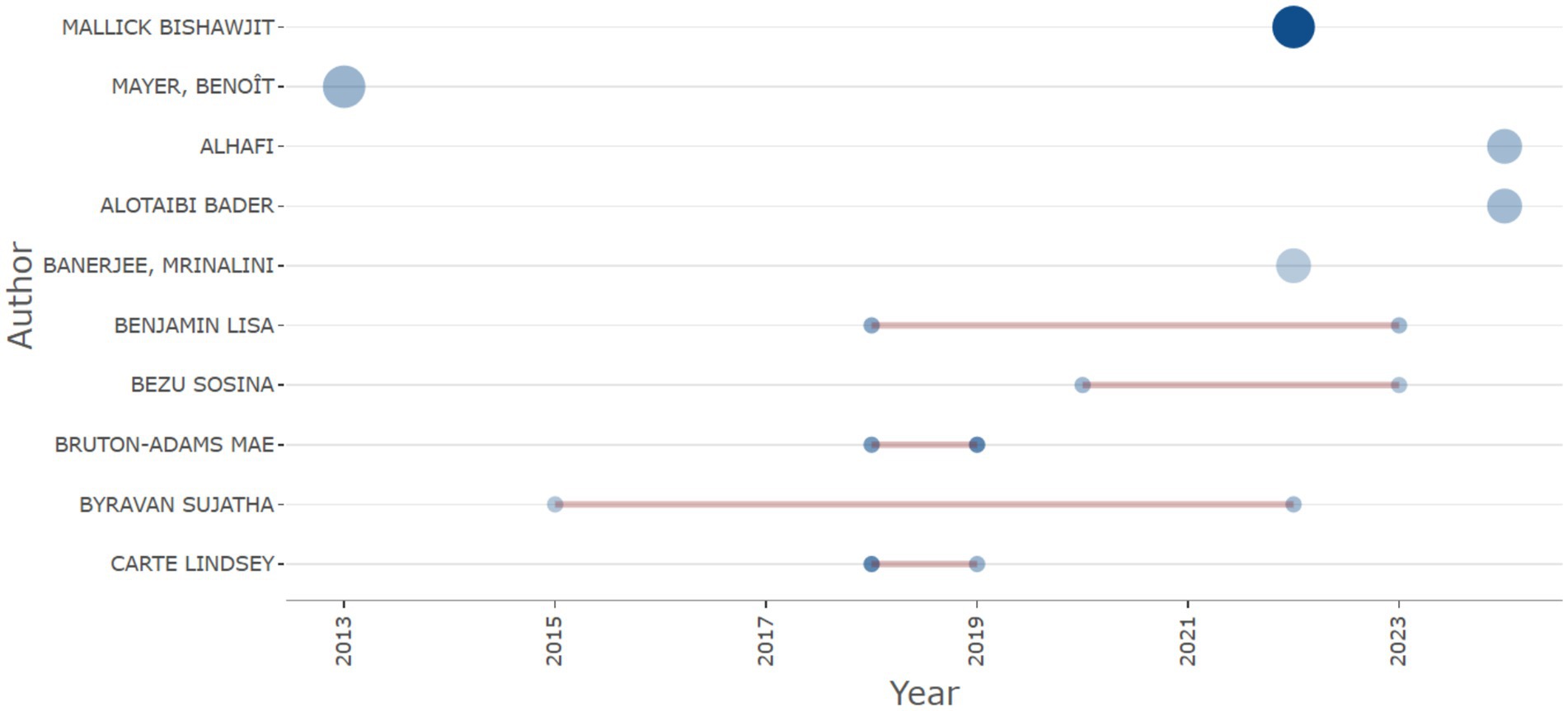

Figure 4 enlists the top 10 most productive authors who have contributed to the research on climate-induced migration. The bigger node indicates the publication volume. Mallick Bishawjit and Mayer, Benoit have bigger nodes. However, Mayer, Benoit was the most productive author in 2013, but newer authors have become more active. While Byravan Sujatha and Bezu Sosina, have maintained their publication flow research over multiple years. Overall research output has increased over time, particularly in post-2019, indicating a growing field.

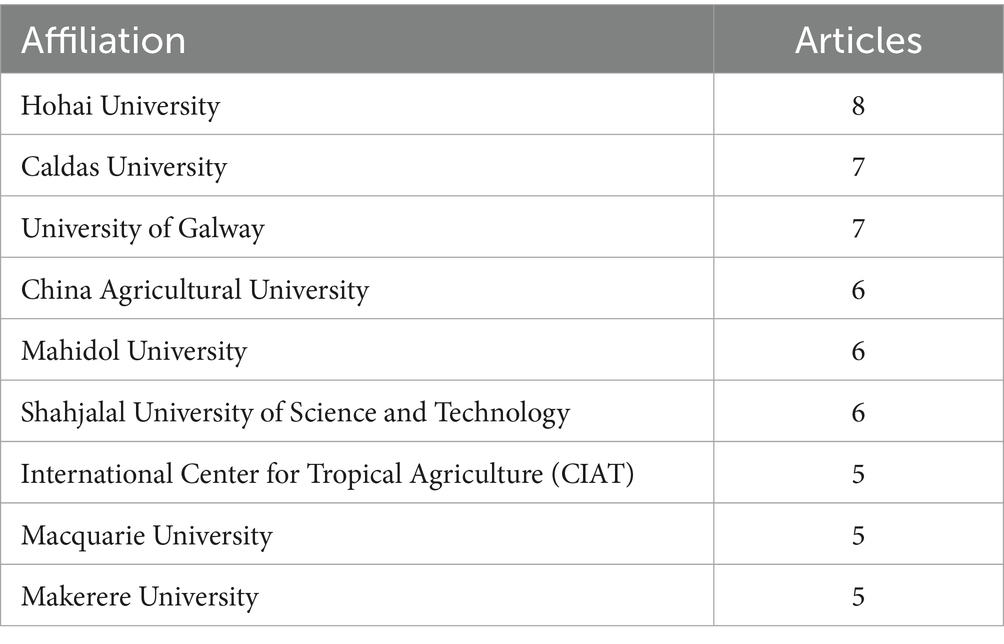

Table 3 presents the publications by top affiliations. In the top 10 relevant affiliations, Hohai University ranks 1st with 8 articles, followed by Caldas University and University of Galway with 7 articles each. Makerere University remains in 10th position with the contribution of five articles. Institutions from both the Global South and North are found to be equally engaged in climate migration research. The first publication from Hohai University was registered in 2022, and by 2023 it had published a total of eight articles. Notably, the activity around climate migration has intensified after 2018.

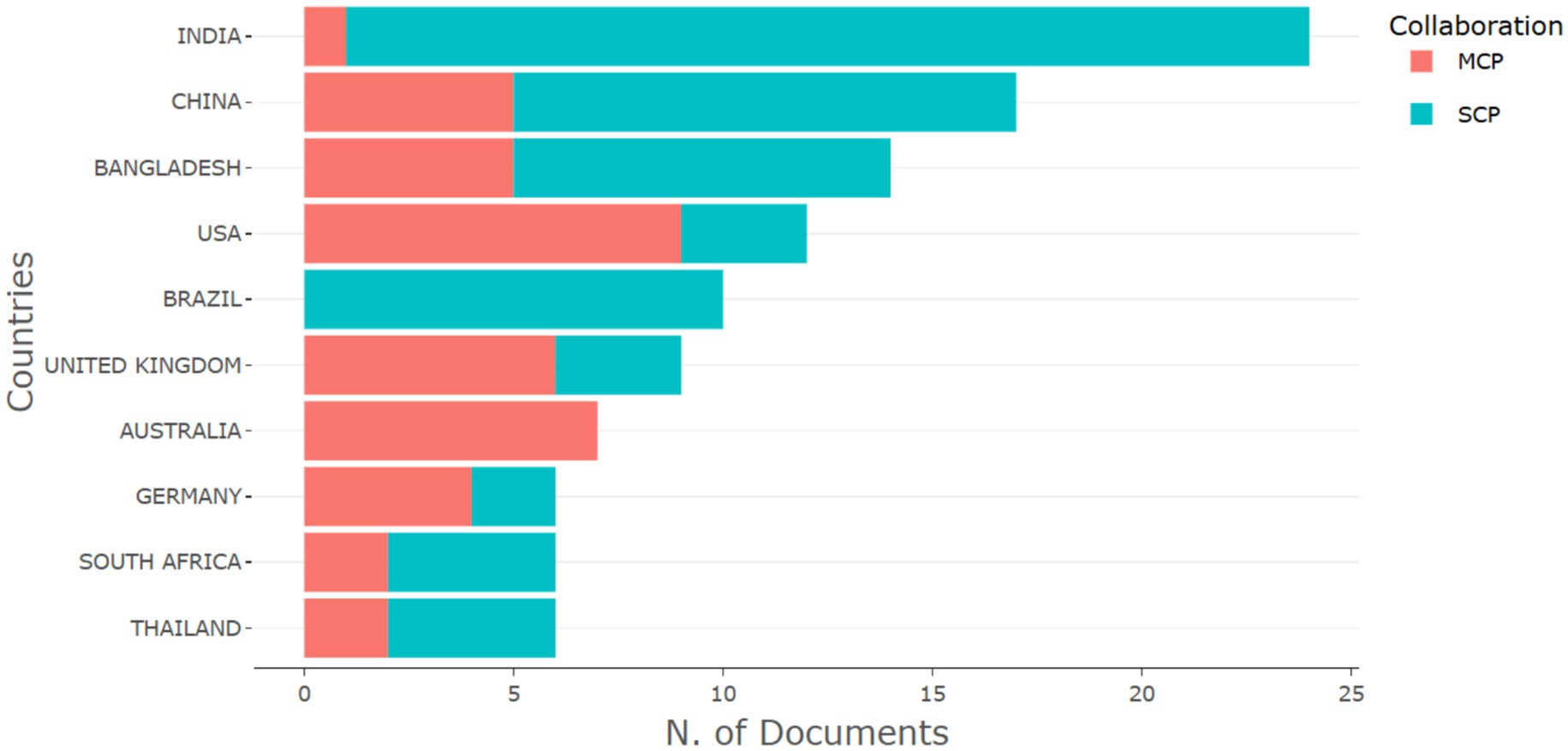

Figure 5 shows the number of articles published by corresponding authors from different countries. MCP refers to Multiple Country Publications and SCP refers to Single Country Publications. The highest number of corresponding authors is recorded from India and China. Authors from India, China, Bangladesh mostly published as single country publications, whereas the USA, UK, and Germany have a higher proportion of multi-country collaborative research. Notably, all corresponding authors from Brazil have published exclusively through SCP, whereas those from Australia have contributed solely to MCP publications. Interestingly, authors from Global North countries are more involved in international collaborations compared to authors from the Global South.

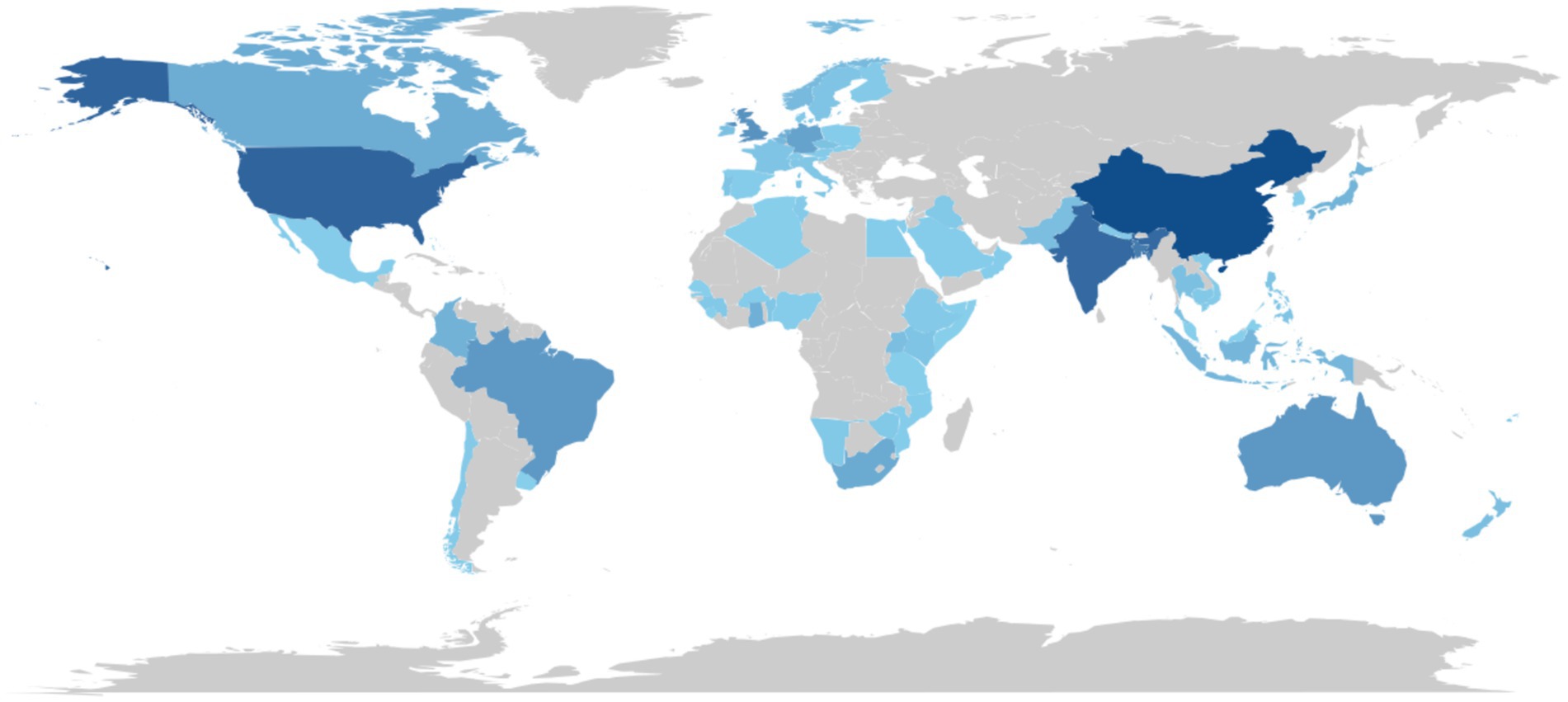

Scientific research on climate migration is particularly widespread in Asia, North America, and some parts of Europe. Figure 6 shows the countries’ scientific production. China is leading in the scientific production with 70 articles, followed by the USA (57) and India (54). Similarly, Bangladesh and the United Kingdom are also important contributors with 44 and 32 documents, respectively. A significant increase in scientific production has been witnessed, especially in China, India, and the United States. By 2024, India reached 54 articles, and Bangladesh had 44. The USA and the UK began publishing actively around 2014, with substantial increases in recent years.

If we compare the total citations, the United States significantly leads with 451 citations. However, China and India have 291 and 256 citations. United States (37.6) also leads in average citations per article followed by the United Kingdom (26), Poland (25), Bahamas (21) and Pakistan (20). However, China (17.1) and India (10.7) with a large number of publications have lower average citations.

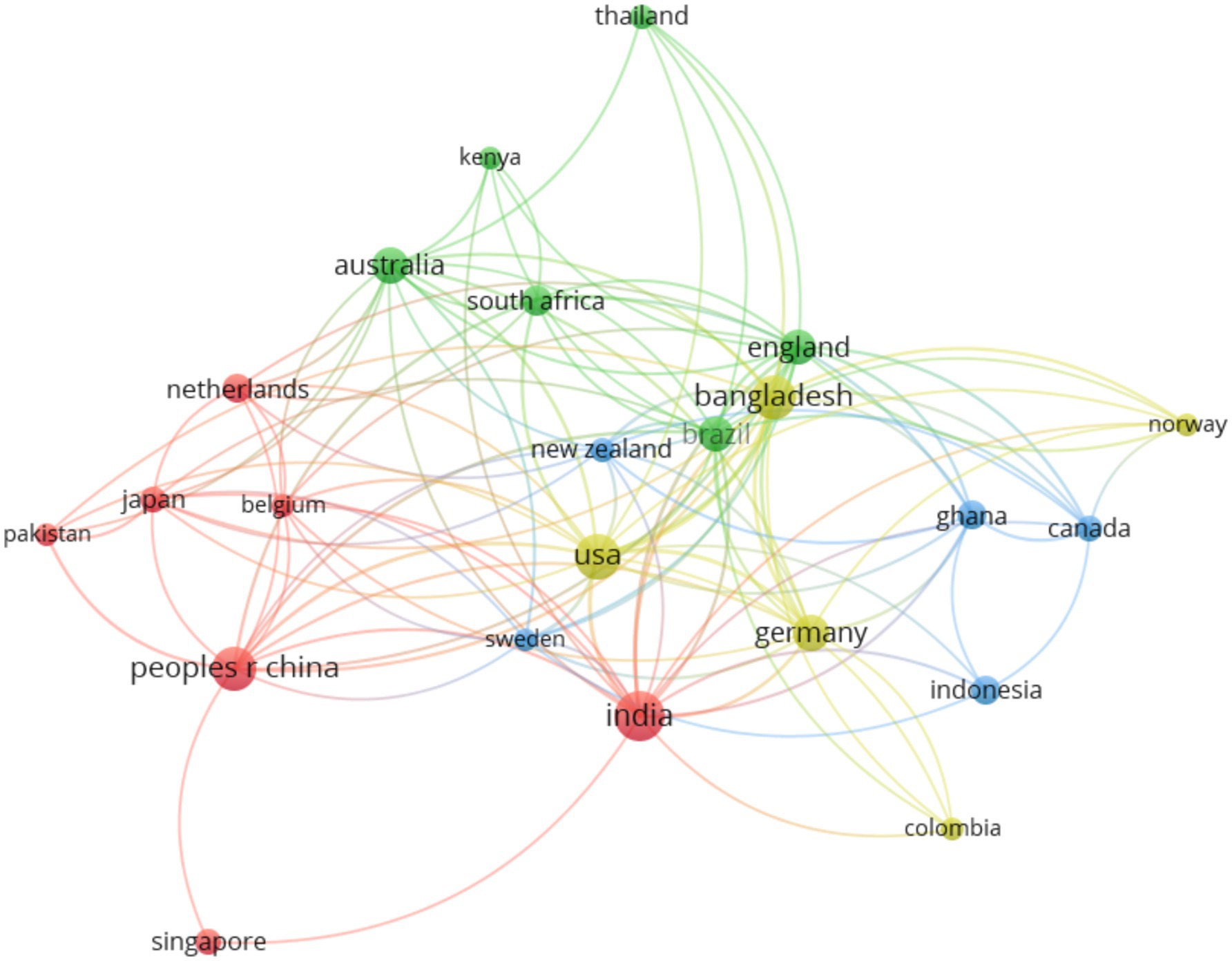

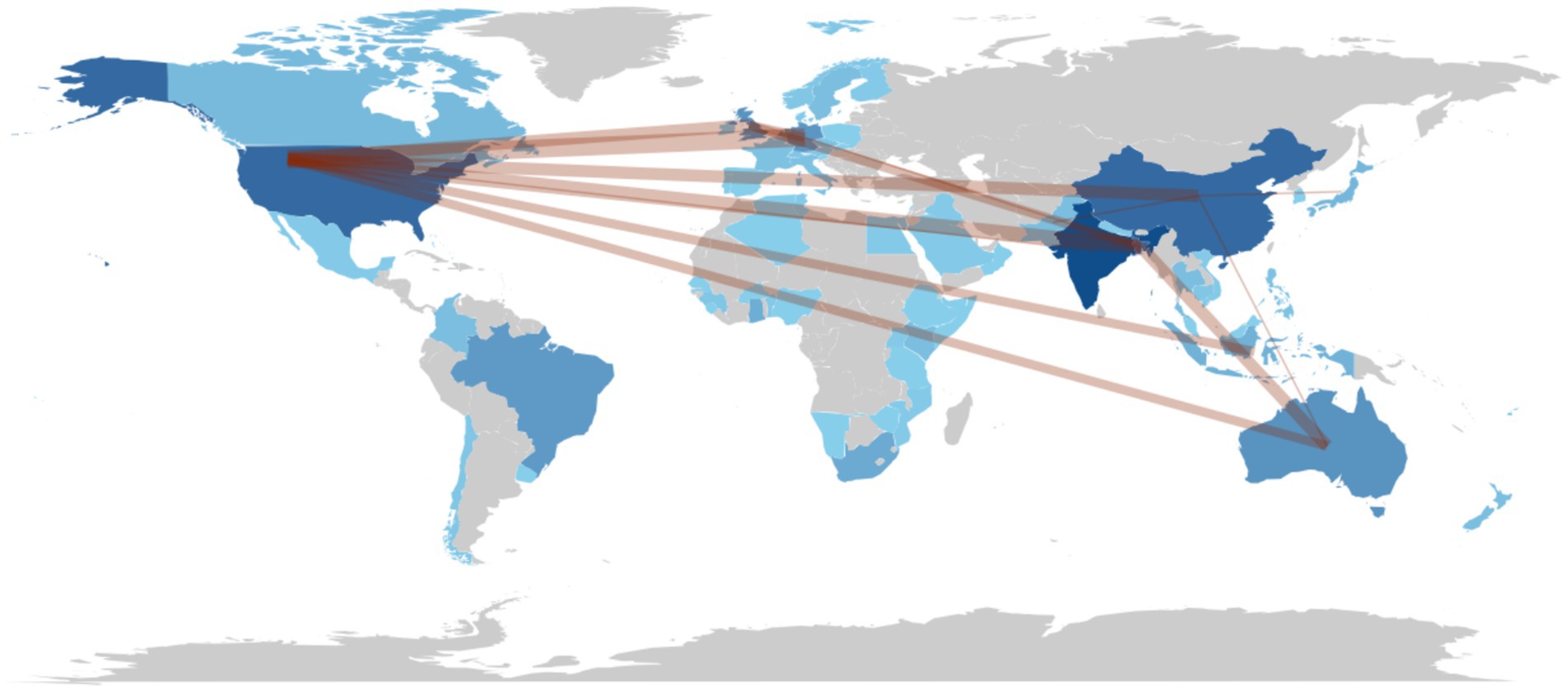

Citation analysis at the country level is a fundamental aspect of bibliometric analysis as it evaluates citation patterns across countries. Figure 7 visually represents the citation analysis of countries. Among 237 countries, 23 met the threshold of at least five citations in our dataset. In this network, the size of each node corresponds to the citation weight of the country, while the lines between nodes indicate citation connections. The label size reflects the relative importance of each country, based on PageRank values. Countries such as the USA, Germany, UK, and Australia have received the highest number of citations. USA, India, and China emerge as key contributors with strong citation connections, indicating their central role in shaping the discourse (Figure 8).

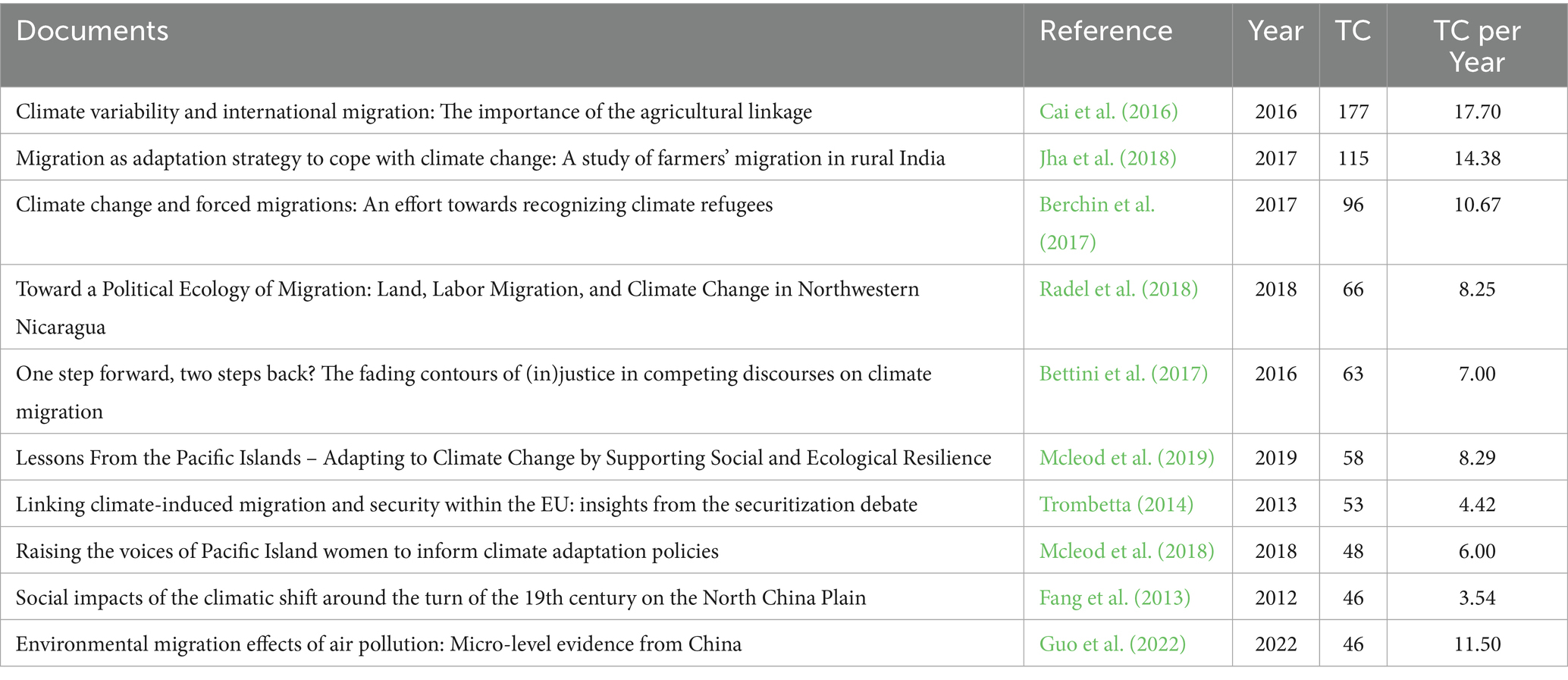

Table 4 indicates the most highly cited documents on climate-induced migration, published from 2000 to 2024. The article “Climate Variability and International Migration: The Importance of the Agricultural Linkage,” written by Ruohong Cai and published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, has accumulated 177 citations and stands highest in our dataset. This article finds a strong linkage between temperature and cross-country migration in agriculture-dependent countries. The most recent article with the least citations was titled “Environmental Migration Effects of Air Pollution: Micro-Level Evidence from China.” It was written by Qingbin and published in Environmental Pollution. This article finds that air pollution increases the probability of internal migration. Altogether, these articles have been cited 768 times.

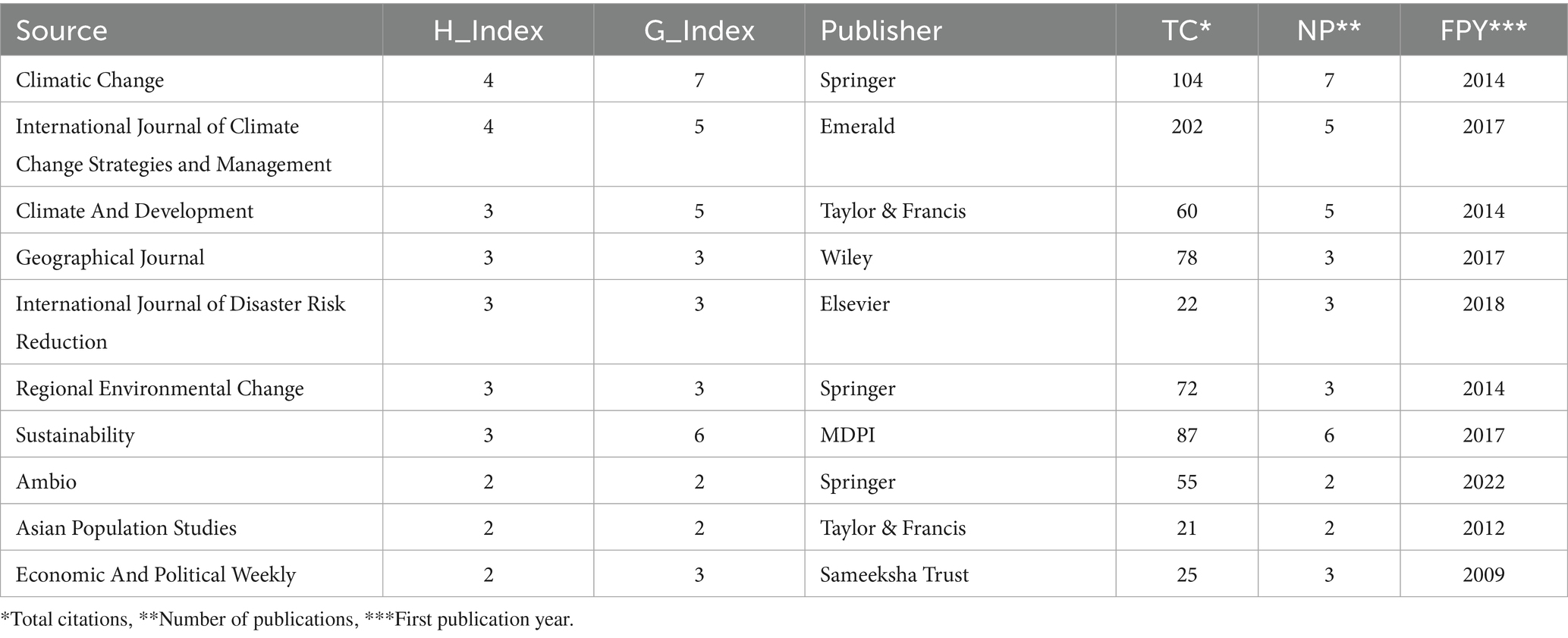

Table 5 shows the most productive journals in our dataset. These journals have 39 publications and 726 citations. Three of the articles were published by Springer and two by Taylor & Francis. The h-index is a widely used metric for measuring academic impact by assessing both publications and their citations, while the g-index ensures that the top “g” papers have received at least “g2” cumulative citations. Despite criticism, the h-index remains a key indicator of a researcher’s scientific production (Formoso, 2022).

The journal ‘Climatic Change’ has the highest number of publications (7) with citations (104). However, ‘International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management’ has five publications but 202 citations. ‘Strategies and Management’ is the third most influential journal with five publications and 60 citations. The journal ‘Climatic Change’ also leads in h-index (4) and g-index (7).

Climate change is found to be the most dominant keyword in our dataset which appeared 87 times. After that migration occurred 56 times and climate migration accrued 19 times. The use of other terms such climate refugees, environmental migration, displacement, adaptation, vulnerability and climate justice indicates that discussion is not limited to just migration but also the coping mechanisms, risks, and resilience and aftermaths. The use of these keywords increased drastically after 2018. Interestingly, keyword ‘Bangladesh’ occurred 19 times, which shows its significance as a key study area in climate migration.

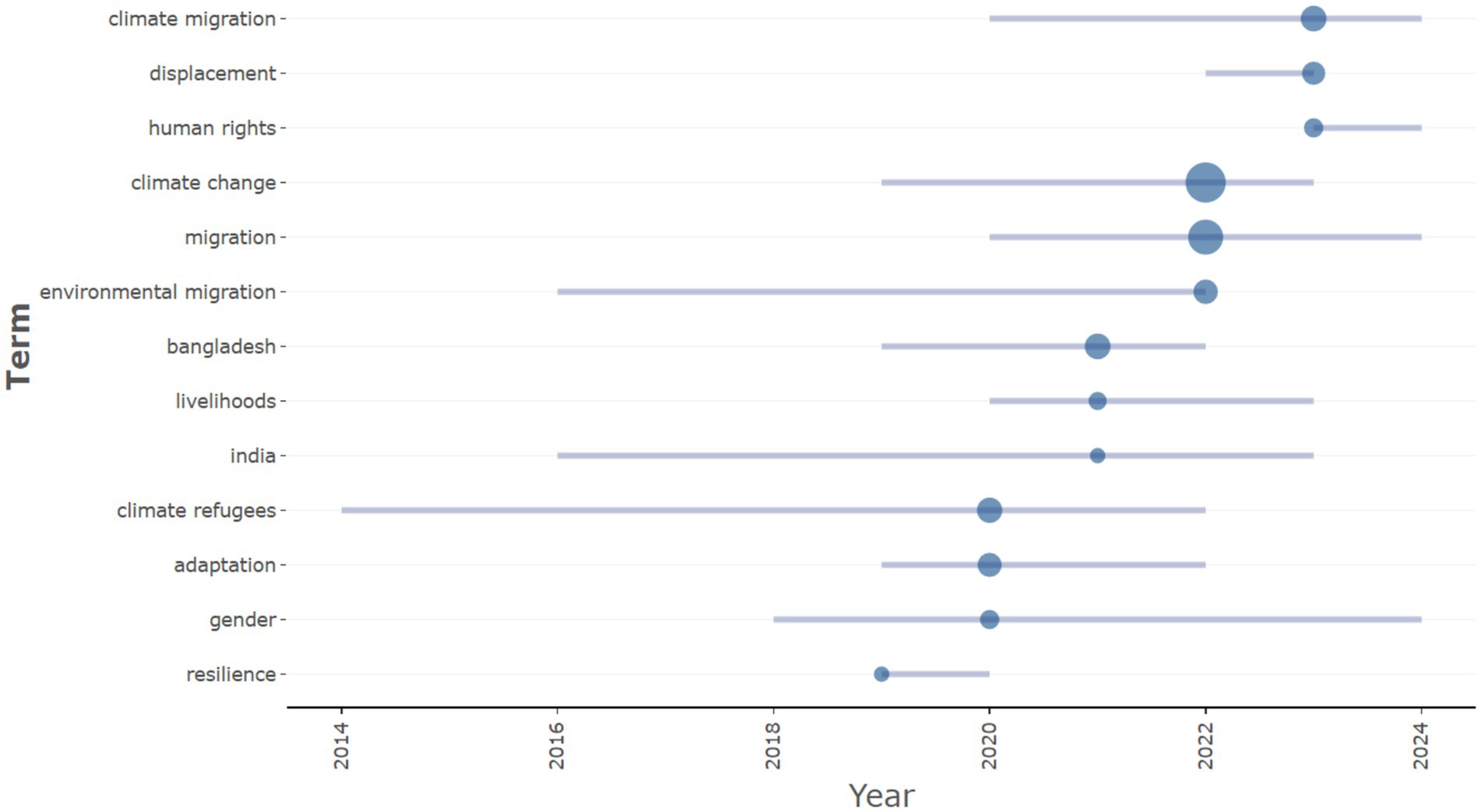

Figure 9 shows the temporal evolution of key topics in climate migration research, based on author keywords. Horizontal lines indicate years during which a specific term has been actively used in the literature, while the bubble size represents the frequency of occurrence. Environmental migration and climate refugees were among the earliest used terms to appear in research. The last few years have seen a surge in terms such as climate migration, displacement, and human rights. Much of the focus is being placed on the legal and social dimensions of climate-induced migration. Newer themes such as resilience, gender, adaptations and human rights are gaining greater attention.

Figure 10 visualizes global collaboration among researchers. The United States has emerged as a hub of collaboration with the highest number of international collaborations with China, Bangladesh, the UK, India, and Australia. Apart from the United States, climate migration research is dominated by China, India, and Australia. Meanwhile, European countries, particularly the UK and Germany, serve as secondary hubs, forming strong links with both Global North and Global South institutions. However, South–South collaborations remain limited, with most partnerships occurring through Global North institutions. The network structure makes visible the North-led brokerage and thin South–South ties, implying that evidence and frames travel along unequal corridors of influence—a justice issue in its own right that shapes which adaptation/mobility solutions gain traction.

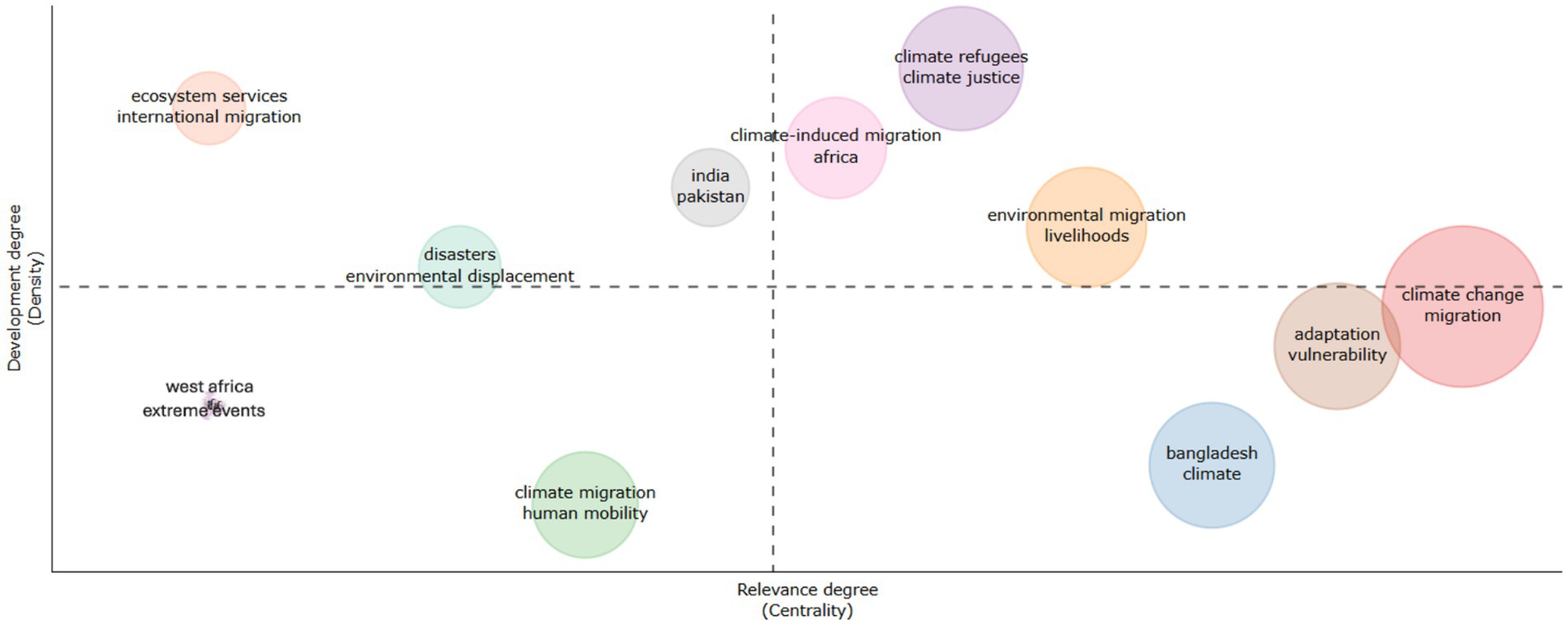

Figure 11 shows the thematic map based on author keywords. The Thematic Map is suitable to understand the relevant issues (Bagdi et al., 2023) by understanding the present status and analyzing the future direction in the field (García-Lillo et al., 2023). The map categorizes research themes based on development (density) and relevance (centrality) within climate migration literature and divides into four quadrants. This thematic map was generated using a clustering technique (Louvain) algorithm where research themes were grouped based on their relevance and development. Thematic centrality of ‘adaptation’, ‘livelihoods’, and ‘vulnerability’ signals the field’s shift from crisis talk to justice-attentive, agency-recognizing framings; yet the Basic/Transversal quadrant shows that key justice concepts remain under-integrated, underscoring the need for South-led theorization.

Motor Themes located on the upper right quadrant are well-developed and highly relevant, central, and dense themes. Keywords such as climate change migration, adaptation, vulnerability, and environmental migration with livelihoods. These themes advance discourse and reflect core policy and resilience strategies.

The upper left Quadrant indicates themes that are well-developed, specialized and dense, but less central to the overall discourse. Topic areas such as ecosystem services and international migration fall here. These peripheral themes are important yet not widely interconnected with other major themes.

The Bottom Right Quadrant is based on themes which have high relevance but are less developed networks. Adaptation, vulnerability, climate change and migration are key issues but require further attention. These are widely discussed themes but there is room for thorough engagement in policy and research.

The Bottom Left Quadrant is known as an emerging theme, consisting of underdeveloped topics that might be gaining or losing attention. A network will gradually develop topics such as climate migration, mobility, West African and extreme events. These themes either need more research attention or are becoming less central to the current discourse.

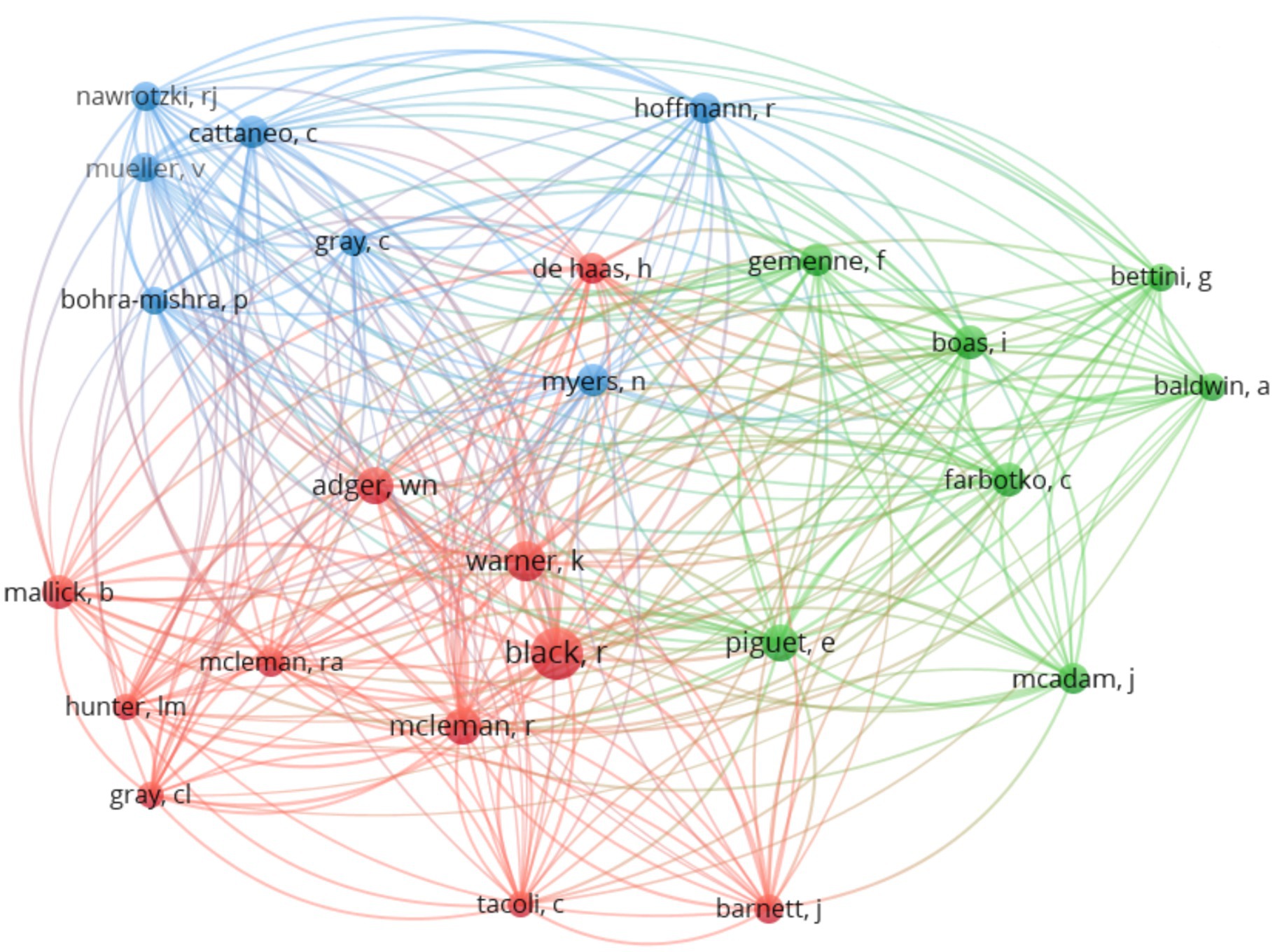

Figure 12 depicts the co-citation network of authors. The visualization created by VOSviewer includes authors who have been cited at least 15 times. Authors are grouped into three distinct clusters while each representing different thematic contributions within the field. The red cluster includes authors such as Richard Black, W. Neil Adger, and Robert A. McLeman, who are prominent figures in climate migration, environmental change, and human mobility research. Their research interests lie in adaptation, displacement, resilience, and policy responses. The green cluster includes Ingrid Boas, François Gemenne, and Jane McAdam who are primarily linked to governance, policy frameworks, and the socio-political dimensions of climate migration. These authors work on climate justice, legal frameworks, and institutional responses to migration. The blue cluster is represented by authors Cristina Cattaneo, Clark Gray, and Raphael Nawrotzki, who are focused on empirical studies, statistical modeling, and economic perspectives on migration and environmental stressors. They often utilize quantitative methods to assess migration drivers and decision-making processes. Cluster composition reveals agenda-setting by Global-North institutions in legal/normative and econometric strands; bridging these with Southern empirics and community-based methods is essential to avoid reproducing extractive knowledge dynamics.

Discussion

The trend in average citations per document from 2004 to 2024, as shown in Figure 3, reflects not only the evolving academic interest in climate-induced migration in the Global South but also illustrates deeper structural inequalities in global knowledge production. The sharp rise in citations post-2012, peaking in 2018, aligns with critical global events and policy developments that elevated the topic in academic and policy circles. The Paris Agreement (2015) brought climate-induced displacement to the international policy agenda, while devastating climate events in the Global South, such as the 2016 Cyclone Winston in Fiji and major floods in South Asia, stimulated scholarly and humanitarian interest. Influential works during this period, including those by Cai et al. (2016) on climate-migration linkages via agriculture, Berchin et al. (2017) advocating legal recognition of climate refugees, and Bettini et al. (2017) critiquing injustice in migration discourse, became widely cited across disciplines. These contributions marked a shift toward more justice-centered and nuanced conceptualizations of climate mobility, incorporating lenses of vulnerability, agency, and intersectionality (Black et al., 2011; Radel et al., 2018; McLeod et al., 2018).

The decline in citations after 2018 does not necessarily indicate waning interest but can be largely attributed to citation lag, as publications from 2022 to 2024 have not had sufficient time to accrue citations (Donthu et al., 2021). More importantly, it reveals enduring citation inequities. As Arruda Filho et al. (2024) and Milán-García et al. (2021) observe, Global North scholars and institutions continue to dominate both publication and citation counts, even though the empirical focus is often on the Global South. This epistemic imbalance is a central concern in climate justice scholarship, which critiques the marginalization of Southern knowledge systems and calls for greater visibility of Global South scholars and community-driven research (Anjum and Aziz, 2025a,b; Bettini et al., 2017). While the number of studies led by authors from institutions in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America is increasing, these still face barriers in accessing high-impact journals and citation networks.

Figure 4 maps the temporal publication activity of the top 10 most productive authors in climate-induced migration research, revealing patterns that reflect broader climate justice dynamics in academic knowledge production. Mallick Bishawjit emerges as the most prolific recent contributor, especially post-2019, through his empirically grounded work in South Asia, emphasizing justice-centered adaptation and relocation (Mallick and Etzold, 2015; Mallick and Schanze, 2020). Mayer Benoît, a key contributor in 2013, remains influential for pioneering legal critiques of refugee protection gaps under climate stress (Mayer, 20132016). Authors like Byravan Sujatha and Bezu Sosina have maintained sustained contributions; Byravan’s research advocates for dignity in planned relocation (Byravan and Rajan, 2015), while Bezu’s Ethiopia-focused work reveals intersectional vulnerabilities in youth and smallholder migration (Bezu and Holden, 2014). Emerging scholars such as Banerjee, Bruton-Adams, and Carte reflect a recent diversification of themes and perspectives, particularly those aligned with feminist and postcolonial approaches (McLeod et al., 2018; Morrison et al., 2023).

This post-2019 uptick in author productivity underscores a maturing and expanding field, yet it also exposes persistent epistemic inequalities. Most highly cited and visible authors remain affiliated with Global North institutions, despite the research being grounded in Global South realities—an imbalance critiqued in recent bibliometric reviews (Milán-García et al., 2021; Arruda Filho et al., 2024). As Anjum and Aziz (2025a) note, the dominance of Northern epistemologies in climate justice research sidelines Southern perspectives. These citation and authorship hierarchies risk reinforcing colonial knowledge dynamics and must be addressed by promoting South–South collaboration, inclusive citation practices, and recognition of indigenous and community knowledge.

The author and institutional trends presented in Figure 4 and Table 3 reflect a promising expansion of climate-induced migration research, particularly from the Global South. Scholars like Mallick Bishawjit and Bezu Sosina have made sustained, justice-oriented contributions rooted in local contexts, while institutions such as Hohai University, Makerere University, and Shahjalal University demonstrate growing regional leadership. This diversification marks a positive shift toward more inclusive and grounded scholarship. However, consistent with critiques from climate justice literature (e.g., Anjum and Aziz, 2025a; Bettini et al., 2017), Global South institutions and scholars still face structural barriers in accessing global research networks and shaping dominant narratives. Overall, the findings highlight an increasingly vibrant and geographically diverse field, while underscoring the continued need for equitable collaborations, recognition, and funding structures that empower Global South leadership.

Figure 5 illustrates the geographic distribution of corresponding authors in climate-induced migration research, distinguishing between Single Country Publications (SCP) and Multiple Country Publications (MCP). The highest publication volumes originate from India, China, and Bangladesh, with a predominant focus on SCP, suggesting strong domestic research capacities but limited international integration. This pattern is critical from a climate justice perspective, as it reflects both the strengths and constraints of Global South scholarship. While these countries are among the most affected by climate-induced migration (Rigaud et al., 2018), their limited participation in transnational research collaborations points to structural barriers in funding access, institutional networks, and linguistic capital, reinforcing long-standing North–South knowledge hierarchies (Arruda Filho et al., 2024; Anjum and Aziz, 2025a). The case of Brazil, whose corresponding authors exclusively published via SCP, exemplifies this phenomenon despite the country’s significant exposure to environmental displacement in the Amazon and northeast regions.

Conversely, Global North countries—USA, UK, Germany, and Australia—display a higher share of MCPs, reflecting dominant roles in agenda-setting, funding flows, and authorship hierarchies. For instance, the UK and USA, while producing fewer total publications than India and China, appear more integrated in cross-national research networks. This dynamic echoes critiques by Bettini et al. (2017) and Milán-García et al. (2021), who show how North-based institutions often lead collaborative projects even on Global South issues, potentially shaping narratives and research priorities. Australia’s exclusive involvement in MCPs indicates a policy-science nexus that leans heavily on international engagement, possibly linked to its geopolitical focus on the Pacific, a region facing existential threats due to climate-induced migration (McLeod et al., 2018; Morrison et al., 2023).

Figure 6 reveals notable geographical patterns in the scientific production of climate-induced migration research, with particularly high output from China (70 articles), the USA (57), and India (54). The growing participation of countries such as Bangladesh (44) and the UK (32) also reflects an expanding and increasingly internationalized field. This growth in Global South scholarship, particularly from India and Bangladesh, is commendable, as it brings attention to frontline regions where climate impacts and migratory pressures are already acute. However, a climate justice lens requires critical engagement not just with the quantity of publications, but with whose knowledge is produced, disseminated, and cited. While China and India have high publication volumes, their average citations per article remain lower (17.1 and 10.7 respectively) compared to the USA (37.6), the UK (26), and even smaller contributors like Poland (25) and Pakistan (20). This disparity suggests ongoing structural citation inequities, where Global South knowledge is often less recognized in dominant academic discourse (Milán-García et al., 2021; Arruda Filho et al., 2024).

These patterns echo concerns in climate justice scholarship about epistemic inequality and the coloniality of knowledge production. For instance, Anjum and Aziz (2025c) emphasize that even when research is rooted in Global South contexts, citations, influence, and policy uptake tend to favor Global North institutions. This is reinforced by Bettini et al. (2017), who critique how Northern-centric narratives often overshadow context-sensitive, justice-oriented research emerging from the Global South. Moreover, although the USA leads in both total and average citations, much of its research focuses on other regions, raising concerns about positionality, representation, and power asymmetries. In contrast, countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan, despite their vulnerability, produce fewer high-impact papers, often due to barriers in accessing elite journals, funding, and transnational collaborations. These results suggest the urgent need to recognize and amplify Southern epistemologies, promote inclusive citation practices, and ensure that those most affected by climate displacement are not only research subjects but also leading voices in the global academic and policy arenas.

Table 4 showcases a strong and evolving foundation of high-impact scholarship on climate-induced migration, led by widely cited works such as Cai et al. (2016) and Jha et al. (2018), which establish critical empirical linkages between environmental stressors and migration, especially in agriculture-dependent regions. Notably, studies like Bettini et al. (2017) and Radel et al. (2018) enrich the discourse by embedding climate migration within broader justice and political ecology frameworks, while McLeod et al. (2018, 2019) foreground Indigenous and gendered perspectives from the Pacific Islands, aligning with the decolonial aims of climate justice. The inclusion of newer works such as Guo et al. (2022) reflects the field’s responsiveness to emerging drivers like air pollution. This collection of literature, with over 760 citations in total, is commendable not only for its scholarly depth but also for its increasing orientation toward equity, intersectionality, and community-centered adaptation, demonstrating meaningful progress toward a more justice-oriented and inclusive research landscape.

Table 5 highlights the distribution of influential journals in climate-induced migration research, revealing both the visibility of the field and the dynamics of knowledge dissemination. From a climate justice perspective, the presence of journals such as Climatic Change, International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, and Climate and Development—with a combined total of 17 articles and over 360 citations—indicates growing academic engagement with the complex interplay between environmental stressors, displacement, and human rights. Notably, the International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management stands out with only five publications but the highest total citations (202), suggesting that its content is especially impactful, likely due to its focus on adaptation strategies and policy integration, themes central to justice-oriented responses (Jha et al., 2018; Berchin et al., 2017).

The dominance of mainstream publishers such as Springer, Taylor & Francis, and Elsevier, while reflecting academic rigor, also underscores concerns raised in climate justice scholarship about restricted access and global inequalities in publication visibility and affordability (Anjum and Aziz, 2025c; Arruda Filho et al., 2024). Journals like Sustainability (MDPI), which offer open access, are playing an important democratizing role with six publications and 87 citations, helping to amplify voices from the Global South and increase accessibility for underfunded institutions. Importantly, the inclusion of regionally focused journals such as Asian Population Studies and Economic and Political Weekly—both publishing fewer but impactful studies—illustrates efforts to engage with localized, community-based, and often underrepresented perspectives on migration and vulnerability (McLeod et al., 2018; Radel et al., 2018).

Figure 2 and Table 2 present a co-occurrence network of author keywords, illustrating four thematic clusters that define the intellectual structure of climate-induced migration research. The red cluster centers on climate change, adaptation, and vulnerability, interlinked with gender, livelihoods, resilience, and Sub-Saharan Africa. This grouping emphasizes justice-oriented concerns around exposure, coping capacity, and intersectionality, especially in Global South contexts (McLeod et al., 2018; Radel et al., 2018). The green cluster focuses on migration, climate refugees, climate justice, and human rights, highlighting a normative and rights-based turn in the field that critiques securitized framings and foregrounds dignity, equity, and historical responsibility (Bettini et al., 2017; Mayer, 2016; Berchin et al., 2017). Together, these clusters reflect a broadening of the field from empirical assessments of mobility to ethical and legal frameworks, signaling increasing alignment with the principles of climate justice.

Figure 9 maps the temporal evolution of key terms in climate-induced migration research and reveals a shift from early environmental determinism toward a more nuanced, justice-oriented discourse. Terms like “environmental migration” and “climate refugees” were dominant in the early years, particularly around 2014–2016, reflecting the initial framing of climate migration as an inevitable outcome of environmental change. However, these framings have been widely critiqued for their securitized and decontextualized narratives, which risk undermining the agency of affected populations and oversimplifying complex socio-political drivers (Bettini et al., 2017; Mayer, 2016). In contrast, recent years—especially post-2020—have seen a marked rise in the usage of terms such as “displacement,” “human rights,” and “climate migration,” indicating a shift toward more legal, social, and ethical considerations, in line with the principles of climate justice (Berchin et al., 2017; McLeod et al., 2018).

Simultaneously, the growing presence of terms like “resilience,” “adaptation,” “gender,” and “livelihoods” points to an increasing concern with structural vulnerability, intersectionality, and local agency in shaping mobility outcomes (Radel et al., 2018; Morrison et al., 2023). The emphasis on “gender” and “livelihoods” particularly signals engagement with feminist and community-based perspectives, which advocate for recognition of how climate stress intersects with social roles, economic insecurity, and historical marginalization (McLeod et al., 2018; Anjum and Aziz, 2025b). The recent surge in “human rights” discourse reflects ongoing advocacy for formal legal protection for climate-displaced persons, and a movement away from crisis narratives toward rights-based and participatory approaches. Overall, this evolution demonstrates encouraging progress in the field—moving from reactive and technocratic framings to critical, inclusive, and justice-informed paradigms that better reflect the lived realities of vulnerable populations in the Global South (Anjum and Aziz, 2025a; Aziz and Anjum, 2024).

Figure 10 reveals the global architecture of scholarly collaboration in climate-induced migration research, underscoring a persistent North–South asymmetry in knowledge production networks. The United States stands out as the dominant hub, collaborating extensively with China, India, Bangladesh, the UK, and Australia. While such partnerships have contributed to increased scholarly output and funding access, they often follow patterns of asymmetric power, where Global North institutions control research agendas, lead authorship, and determine publication venues, even when studies focus on Global South contexts (Anjum and Aziz, 2025a; Arruda Filho et al., 2024). This pattern reinforces epistemic hierarchies that climate justice scholars’ critique as replicating colonial modes of knowledge extraction, where affected communities and Southern scholars are positioned as data providers rather than co-producers of knowledge (Bettini et al., 2017; Aziz and Anjum, 2025).

Though countries like China, India, and Australia are emerging as productive contributors, the figure shows limited South–South collaboration, with most research partnerships still mediated through Global North institutions such as those in the USA, UK, and Germany. This reflects broader critiques in climate justice and development literature regarding the lack of horizontal, equitable research networks among Global South regions, which share similar climate vulnerabilities and socio-political constraints but are rarely given space to collaborate directly (Milán-García et al., 2021; Morrison et al., 2023). For instance, despite their shared experiences with displacement and adaptation, countries like Bangladesh and Kenya, or India and the Philippines, are rarely seen in direct collaboration. Addressing this gap is crucial not only for ensuring context-sensitive and inclusive research, but also for empowering Southern institutions to reshape the theoretical, methodological, and policy discourse on climate migration from within. Moving forward, fostering South–South knowledge solidarity and challenging North-led epistemic dominance must be central to a climate justice-informed research agenda.

Figure 11 presents a thematic map of climate-induced migration research using author keywords, structured along two axes: centrality (relevance to the field) and density (degree of development). The upper right quadrant (Motor Themes) includes climate change, migration, adaptation, vulnerability, and environmental migration with livelihoods, reflecting well-developed and central topics that dominate scholarly and policy debates. These themes represent the core of climate justice discourse, focusing on both structural drivers and human agency in contexts of environmental stress (Bettini et al., 2017; Gemenne and Blocher, 2017). The presence of adaptation and livelihoods in this quadrant signifies a shift from reactive framings toward resilience-building and justice-based strategies that prioritize agency, equity, and systemic transformation (McLeod et al., 2018; Radel et al., 2018).

In the upper left quadrant (Highly Developed but Peripheral Themes), we find ecosystem services and international migration. These are specialized and technically mature themes, but less central to the current climate migration discourse. Their marginality may reflect a lack of integration with justice-centered and community-based approaches, even though ecosystem degradation and cross-border migration are critical issues, especially in regions affected by ecological collapse and political instability (Morrison et al., 2023). The lower right quadrant (Basic and Transversal Themes), including climate-induced migration, climate refugees, and climate justice, demonstrates that these topics are highly relevant but still underdeveloped in their theoretical integration and empirical breadth—pointing to the need for deeper interdisciplinary engagement and South-led frameworks (Anjum and Aziz, 2025a; Mayer, 2016). Meanwhile, the lower left quadrant (Emerging or Declining Themes)—with terms like West Africa, extreme events, and human mobility—represents areas requiring renewed focus. Although these topics are crucial for understanding contextual vulnerability and acute shocks, their marginal status reveals ongoing geographical and thematic blind spots in dominant literature (Arruda Filho et al., 2024; Milán-García et al., 2021). As climate impacts intensify, it is essential for research to center these neglected themes and ensure that underrepresented regions and framings are brought into the mainstream of climate migration scholarship.

Figure 12 maps the co-citation network of influential authors in climate-induced migration research, organized into three thematic clusters that reflect distinct scholarly orientations within the field. The red cluster, featuring prominent figures like Richard Black, W. Neil Adger, and Robert A. McLeman, is grounded in research on human mobility, adaptation, and environmental change. These authors have been central to conceptualizing migration as both a coping strategy and adaptation mechanism in response to environmental stressors (Black et al., 2011; Adger et al., 2014). Their work emphasizes structural vulnerability, policy responses, and the role of resilience, aligning closely with climate justice principles that advocate for agency-driven and context-specific solutions (Mallick and Etzold, 2015; McLeman, 2018). The presence of Md. Bishawjit Mallick in this cluster further strengthens its justice orientation, particularly through his contributions from a Global South perspective on trapped populations, relocation, and community adaptation (Mallick and Schanze, 2020).

The green cluster, anchored by authors such as François Gemenne, Ingrid Boas, and Jane McAdam, brings a legal, governance, and normative focus to the field. These scholars engage with climate justice, human rights, and institutional accountability, often critiquing the inadequacies of current legal regimes to protect climate-displaced populations (McAdam, 2011; Boas et al., 2019). Their work underscores the need to move beyond securitized or apolitical framings toward rights-based and participatory frameworks, calling for institutional reform and equitable governance structures (Bettini et al., 2017; Gemenne and Blocher, 2017). The green cluster reflects a vital strand of scholarship that situates climate migration within broader questions of power, colonial legacies, and global inequality, thus advancing the normative core of climate justice.

In contrast, the blue cluster, comprising authors such as Cristina Cattaneo, Clark Gray, Raphael Nawrotzki, and Valerie Mueller, is characterized by quantitative, empirical approaches. These scholars have contributed rigorous econometric and demographic analyses of migration drivers, often linking temperature variations, rainfall shocks, and agricultural productivity with mobility outcomes (Cattaneo and Peri, 2016; Nawrotzki and DeWaard, 2016). While this work provides essential insights into causality and migration decision-making, it has been critiqued by justice scholars for sometimes lacking contextual depth and critical engagement with political structures (Bettini et al., 2017). Nonetheless, the increasing integration of these empirical approaches with justice-oriented frameworks holds promise for evidence-based, policy-relevant, and ethically grounded research.

Implications for the climate justice–migration nexus

Our bibliometric findings underscore that climate justice and migration are deeply interconnected but often unevenly articulated in scholarly discourse. Justice-related terms such as climate justice, human rights, gender, and livelihoods emerged as significant clusters in keyword and thematic analyses, demonstrating that the justice–migration nexus is empirically visible across the literature. However, the prominence of Global North authorship and thin South–South collaboration reflects persistent distributive and recognition inequities. Thematic gaps in procedural justice (e.g., inclusive participation in relocation planning) and reparative justice (e.g., linking historical emissions to displacement responsibilities) highlight areas where the field remains underdeveloped. These findings suggest that future research must not only document mobility patterns but also interrogate the justice dimensions shaping who migrates, under what conditions, and with what rights. By foregrounding climate justice, our study reframes migration from being understood merely as a risk management issue to being recognized as a justice-laden process that reflects deeper structural inequities in global governance.

Another limitation stems from linguistic and indexing constraints. As the analysis only includes English-language publications, contributions in regional languages remain unaccounted for. Furthermore, emerging terms like ‘climate mobilities’ and ‘immobility’ may not have been fully captured due to keyword design. These gaps should be explored in future multilingual or mixed-method reviews.

Gaps and opportunities for future research

While climate-induced migration has gained scholarly momentum, key gaps remain that limit both conceptual completeness and the development of just, effective policies. Geographical blind spots persist regions like Central Africa, the Middle East, interior Latin America, and Indian Ocean island states remain underexplored, despite their acute vulnerabilities (e.g., drought-induced rural–urban migration in Sudan or Iran). Within well-studied countries, marginalized groups—such as Indigenous peoples, remote rural communities, and urban informal migrants—are often overlooked. Moreover, migrant destinations are understudied; research tends to focus on departure zones rather than outcomes in host cities (jobs, health, integration).

There is also a growing need to explore mobility trajectories and immobility—including stepwise migration patterns and the plight of “trapped” populations who cannot or choose not to move. Meanwhile, stronger cross-disciplinary integration is essential. Climate science, migration modeling, political science, anthropology, and decolonial theory must be better synthesized to capture the complexity of displacement. Advancing climate attribution methods to quantify migration directly linked to anthropogenic climate change will also reinforce climate justice claims by connecting emissions to displacement. Similarly, policy evaluation research should assess the effectiveness of adaptation, relocation, and migration-as-adaptation interventions to guide future action.

Data scarcity remains a challenge; however, new tools like remote sensing, mobile data, and citizen science offer promising solutions—if used ethically. Research must also address intersectionality, recognizing how gender, age, class, and ability shape migration experiences and adaptation capacity. Lastly, while crisis dominates the discourse, future research should also explore positive migration outcomes, identifying cases where mobility has improved wellbeing or reduced environmental strain. Ultimately, addressing these gaps requires interdisciplinary collaboration, ethical innovation, and Global South leadership, ensuring climate migration scholarship serves equity, justice, and resilience (Anjum and Aziz, 2024).

In essence, the gaps point to a need for more granular, inclusive, and forward-looking research. Bridging these gaps will require collaboration across disciplines and with practitioners, as well as elevating voices from the Global South in setting research agendas. Filling these knowledge gaps will directly inform more just and effective solutions.

Conclusion

This bibliometric analysis of climate-induced migration research in the Global South, viewed through a climate justice lens, reveals a rapidly evolving and increasingly interdisciplinary field. The study analyzed 204 documents spanning two decades (2000–2024), mapping trends in authorship, publication, thematic evolution, and geographic focus. Citation patterns suggest that foundational works—largely published prior to 2020—continue to dominate influence, while newer studies, especially those from the Global South, remain under-cited.

The analysis identified key thematic clusters—such as climate change, displacement, adaptation, and human rights—indicating a welcome shift from narrow crisis narratives to broader, justice-oriented frameworks. Scholars like François Gemenne, Ingrid Boas, Richard Black, and Bishawjit Mallick have contributed significantly to shaping debates across empirical, legal, and normative domains. Nevertheless, epistemic asymmetries persist: Global North institutions continue to dominate collaborative networks and high-impact publications, even though much of the empirical focus lies in the Global South. Thematic maps and network analyses reveal emerging interest in intersectionality, gender, and immobility, but these areas remain underdeveloped. Moreover, the data highlight a lack of sustained South–South collaboration, limited integration of Indigenous knowledge systems, and insufficient research on migration destinations and livelihood outcomes.

From a climate justice perspective, the current research landscape is expanding in promising directions but remains constrained by structural imbalances in authorship, representation, and access. Addressing these gaps will require a reorientation toward inclusive and decolonial knowledge production—where Global South scholars are not just contributors, but agenda-setters. Future research should integrate interdisciplinary methods, strengthen links between empirical evidence and legal frameworks, and foreground the lived realities and voices of displaced populations. Critically, it must also challenge dominant narratives by incorporating historical accountability, relational vulnerability, and the political economy of migration.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MA: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Project administration, Visualization, Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology. GA: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation. AN: Resources, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. IN: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. GA received financial support for writing this article from the Department of Psychology (PSI), University of Oslo (UiO). PSI provided the funding in 2025 under sub-project number 102603241.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adger, W. N., Pulhin, J. M., Barnett, J., Dabelko, G. D., Hovelsrud, G. K., Levy, M., et al. (2014). Human security. In C. B. Field (ed.), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

Almulhim, A. I., Alverio, G. N., Sharifi, A., Shaw, R., Huq, S., Mahmud, M. J., et al. (2024). Climate-induced migration in the global south: an in depth analysis. NPJ Clim. Action 3:47. doi: 10.1038/s44168-024-00133-1

Anjum, G., and Aziz, M. (2024). Advancing equity in cross-cultural psychology: embracing diverse epistemologies and fostering collaborative practices [review]. Front. Psychol. 15:1368663. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1368663

Anjum, G., and Aziz, M. (2025a). Bibliometric analyses of climate psychology: critical psychology and climate justice perspectives. Front. Psychol. 16:1520937. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1520937

Anjum, G., and Aziz, M. (2025b). Psychological insights and structural solutions: using community frame (c-frame) in climate action and policy response. Clim. Pol. 1-11, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2025.2511267

Anjum, G., and Aziz, M. (2025c). Climate change and gendered vulnerability: a systematic review of women's health. Womens Health (Lond) 21:17455057251323645. doi: 10.1177/17455057251323645

Aria, M., and Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 11, 959–975. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

Arruda Filho, M. T. d., Torres, P. H. C., and Jacobi, P. R. (2024). A systematic review of the literature on climate justice: a comparison between the global north and south. Sustainability 16:9888. doi: 10.3390/su16229888

Arsova, S., Genovese, A., and Ketikidis, P. H. (2022). Implementing circular economy in a regional context: a systematic literature review and a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 368:133117. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133117

Aziz, M., and Anjum, G. (2024). Transformative strategies for enhancing women’s resilience to climate change: a policy perspective for low- and middle-income countries. Womens Health 20:17455057241302032. doi: 10.1177/17455057241302032

Aziz, M., and Anjum, G. (2025). Rethinking knowledge systems in psychology: addressing epistemic hegemony and systemic obstacles in climate change studies [perspective]. Front. Psychol. 16:1533802. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1533802

Bagdi, T., Ghosh, S., Sarkar, A., Hazra, A. K., Balachandran, S., and Chaudhury, S. (2023). Evaluation of research progress and trends on gender and renewable energy: a bibliometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 423:138654. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138654

Baldwin, A. (2017). Climate change, migration, and the crisis of humanism. WIREs Clim. Change 8:e460. doi: 10.1002/wcc.460

Barrios, S., Bertinelli, L., and Strobl, E. (2006). Climatic change and rural–urban migration: the case of sub-Saharan Africa. J. Urban Econ. 60, 357–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2006.04.005

Bezu, S., and Holden, S. (2014). Are rural youth in Ethiopia abandoning agriculture? World Development, 64, 259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013

Berchin, I. I., Valduga, I. B., Garcia, J., and de Andrade Guerra, J. B. S. O. (2017). Climate change and forced migrations: an effort towards recognizing climate refugees. Geoforum 84, 147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.022

Bettini, G., Nash, S. L., and Gioli, G. (2017). One step forward, two steps back? The fading contours of (in)justice in competing discourses on climate migration. Geogr. J. 183, 348–358. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12192

Black, R., Arnell, N. W., Adger, W. N., Thomas, D., and Geddes, A. (2013). Migration, immobility and displacement outcomes following extreme events. Environ. Sci. Pol. 27, S32–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.09.001

Black, R., Bennett, S. R. G., Thomas, S. M., and Beddington, J. R. (2011). Migration as adaptation. Nature 478, 447–449. doi: 10.1038/478477a

Boas, I., Farbotko, C., Adams, H., Sterly, H., Bush, S., van der Geest, K., et al. (2019). Climate migration myths. Nature Climate Change 9, 901–903. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0633-3

Bull, B., and Banik, D. (2025). The rebirth of the global south: geopolitics, imageries and developmental realities. Forum Dev. Stud. 52, 195–214. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2025.2490696

Byravan, S., and Rajan, S. C. (2015). Sea level rise and climate change exiles: a possible solution. Bull. At. Sci. 71, 21–28. doi: 10.1177/0096340215571904

Cai, R., Feng, S., Oppenheimer, M., and Pytlikova, M. (2016). Climate variability and international migration: the importance of the agricultural linkage. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 79, 135–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2016.06.005

Caputo, A., and Kargina, M. (2022). A user-friendly method to merge Scopus and web of science data during bibliometric analysis. J. Mark. Anal. 10, 82–88. doi: 10.1057/s41270-021-00142-7

Cattaneo, C., and Peri, G. (2016). The migration response to increasing temperatures. Journal of Development Economics, 122, 127–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.05.004

Carrascal-Hernández, D. C., Grande-Tovar, C. D., Mendez-Lopez, M., Insuasty, D., García-Freites, S., Sanjuan, M., et al. (2025). CO2 capture: a comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of scalable materials and sustainable solutions. Molecules 30:563. doi: 10.3390/molecules30030563

Chakrabarti, D. (2023). Urban theory of/from the global south: a systematic review of issues, challenges, and pathways of decolonization [systematic review]. Front. Sustain. Cities 5:1163534. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.1163534

Cobo, M. j., López-Herrera, A. g., Herrera-Viedma, E., and Herrera, F. (2012). SciMAT: a new science mapping analysis software tool. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 63, 1609–1630. doi: 10.1002/asi.22688

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., and Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 133, 285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

Fang, X., Xiao, L., and Wei, Z. (2013). Social impacts of the climatic shift around the turn of the 19th century on the North China plain. Sci. China Earth Sci. 56, 1044–1058. doi: 10.1007/s11430-012-4487-z

Formoso, G. (2022). The H-index is an unfair measure of scientific achievements. A proposal to address its shortcomings : Cambridge Open Engage.

García-Lillo, F., Sánchez-García, E., Marco-Lajara, B., and Seva-Larrosa, P. (2023). Renewable energies and sustainable development: a bibliometric overview. Energies 16:1211. doi: 10.3390/en16031211

Gemenne, F., and Blocher, J. (2017). How can migration serve adaptation to climate change? Challenges to fleshing out a policy ideal. The Geographical Journal, 183, 336–347. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12205

Guo, Q., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Yi, M., and Zhang, T. (2022). Environmental migration effects of air pollution: micro-level evidence from China. Environ. Pollut. 292:118263. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118263

IFRC. (2021). Displacement in a changing climate: localized humanitarian action at the forefront of the climate crisis. (Geneva, Switzerland: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies).

IPCC (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

Jha, C. K., Gupta, V., Chattopadhyay, U., and Amarayil Sreeraman, B. (2018). Migration as adaptation strategy to cope with climate change. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manage. 10, 121–141. doi: 10.1108/IJCCSM-03-2017-0059

Kirby, A. (2023). Exploratory bibliometrics: using VOSviewer as a preliminary research tool. Publica 11:10. doi: 10.3390/publications11010010

Kumar, R. (2025). Bibliometric analysis: comprehensive insights into tools, techniques, applications, and solutions for research excellence. Spectr. Eng. Manag. Sci. 3, 45–62. doi: 10.31181/sems31202535k

Kumpulainen, M., and Seppänen, M. (2022). Combining web of science and scopus datasets in citation-based literature study. Scientometrics 127, 5613–5631. doi: 10.1007/s11192-022-04475-7

Mallick, B., and Etzold, B. (2015). Environment, migration and adaptation: evidence and politics of climate change in Bangladesh. A H Development Publishing House. Available online at: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1970023484986523285

Mallick, B., and Schanze, J. (2020). Trapped or voluntary? Non-migration despite climate risks. Sustainability 12:4718. doi: 10.3390/su12114718

Mayer, B. (2013). Constructing “climate migration” as a global governance issue: Essential flaws in the contemporary literature. McGill International Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy, 9, 87–117.

Mayer, B. (2016). Climate migration and the politics of causal attribution: A case study in Mongolia. Migration and Development, 5, 234–253. doi: 10.1080/21632324.2015.1022971

Mazzega, P., Rugmini, D. M., and Barros-Platiau, A. F. (2025). Where is the “global south” located in scientific research? Earth Syst. Gov. 25:100269. doi: 10.1016/j.esg.2025.100269

McAdam, J. (2011). Swimming against the Tide: Why a Climate Change Displacement Treaty is Not the Answer. International Journal of Refugee Law, 23, 2–27. doi: 10.1093/ijrl/eeq045

McLeman, R. (2018). Thresholds in climate migration. Popul. Environ. 39, 319–338. doi: 10.1007/s11111-017-0290-2

McLeod, E., Arora-Jonsson, S., Masuda, Y. J., Bruton-Adams, M., Emaurois, C. O., Gorong, B., et al. (2018). Raising the voices of Pacific Island women to inform climate adaptation policies. Mar. Policy 93, 178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.03.011

Mcleod, E., Bruton-Adams, M., Förster, J., Franco, C., Gaines, G., Gorong, B., et al. (2019). Lessons from the Pacific Islands – adapting to climate change by supporting social and ecological resilience. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:289. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00289

Milán-García, J., Caparrós-Martínez, J. L., Rueda-López, N., and de Pablo Valenciano, J. (2021). Climate change-induced migration: a bibliometric review. Glob. Health 17:74. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00722-3

Morrison, K., Nand, M. M., Ali, T., and Mele, S. (2023). Postcolonial lessons and migration from climate change: ongoing injustice and hope. NPJ Clim. Action 2:22. doi: 10.1038/s44168-023-00060-7

Nawrotzki, R. J., and DeWaard, J. (2016). Climate shocks and the timing of migration from Mexico. Population and Environment, 38, 72–100. doi: 10.1007/s11111-016-0255-x

Parsons, M., Asena, Q., Johnson, D., and Nalau, J. (2024). A bibliometric and topic analysis of climate justice: mapping trends, voices, and the way forward. Clim. Risk Manag. 44:100593. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2024.100593

Passas, I. (2024). Bibliometric analysis: the main steps. Encyclopedia 4:2. doi: 10.3390/encyclopedia4020065

Pearson, W. S. (2024). Research Topics in Applied Linguistics as Keywords from Authors and Keywords from Abstracts: A Bibliometric Study. In: H Meihami and R Esfandiari (eds). A Scientometrics Research Perspective in Applied Linguistics. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-51726-6_5

Priovashini, C., and Mallick, B. (2022). A bibliometric review on the drivers of environmental migration. Ambio 51, 241–252. doi: 10.1007/s13280-021-01543-9

Radel, C., Schmook, B., Carte, L., and Mardero, S. (2018). Toward a political ecology of migration: land, labor migration, and climate change in northwestern Nicaragua. World Dev. 108, 263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.04.023

Rigaud, K. K., Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Bergmann, J., Clement, V., Ober, K., et al. (2018). Groundswell: Preparing for internal climate migration. World Bank. doi: 10.1596/29461

Roberts, J. T., and Parks, B. (2006). A climate of injustice: Global inequality, North–South politics, and climate policy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Available online at: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262681612/a-climate-of-injustice/

Ruiz-Rosero, J., Ramirez-Gonzalez, G., and Viveros-Delgado, J. (2019). Software survey: ScientoPy, a scientometric tool for topics trend analysis in scientific publications. Scientometrics 121, 1165–1188. doi: 10.1007/s11192-019-03213-w

Saeid, M. F., Abdulkadir, B. A., Ismail, M., and Setiabudi, H. D. (2025). A bibliometric analysis of metal-based catalysts for efficient hydrogen production. Environ. Qual. Manag. 34:e70046. doi: 10.1002/tqem.70046

Trombetta, M. J. (2014). Linking climate-induced migration and security within the EU: insights from the securitization debate. Crit. Stud. Secur. 2, 131–147. doi: 10.1080/21624887.2014.923699

Wei, W., and Jiang, Z. (2023). A bibliometrix-based visualization analysis of international studies on conversations of people with aphasia: present and prospects. Heliyon 9:e16839. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16839

WoS Help (2020). Web of science core collection help. Available online at: https://images.webofknowledge.com/images/help/WOS/hs_wildcards.html

Keywords: climate-induced migration, Global South, climate justice, bibliometric analysis, epistemic justice, vulnerability and equity

Citation: Aziz M, Anjum G, Nawaz AR and Nadeem I (2025) Who speaks for climate migrants? A justice-oriented bibliometric analysis of Global South research. Front. Clim. 7:1658517. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1658517

Edited by:

Rui Liu, University of Canberra, AustraliaReviewed by:

Susan S. Ekoh, German Institute of Development and Sustainability, GermanyKennedy Liti Mbeva, University of Oxford, United Kingdom