- 1United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues- UNPFII, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Indigenous Determinants of Health Alliance, Washington, DC, United States

- 3Acal El Hajeb/AZUL Network, Tangier, Morocco

- 4Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

- 5Sunway Centre for Planetary Health, Sunway University, Selangor, Malaysia

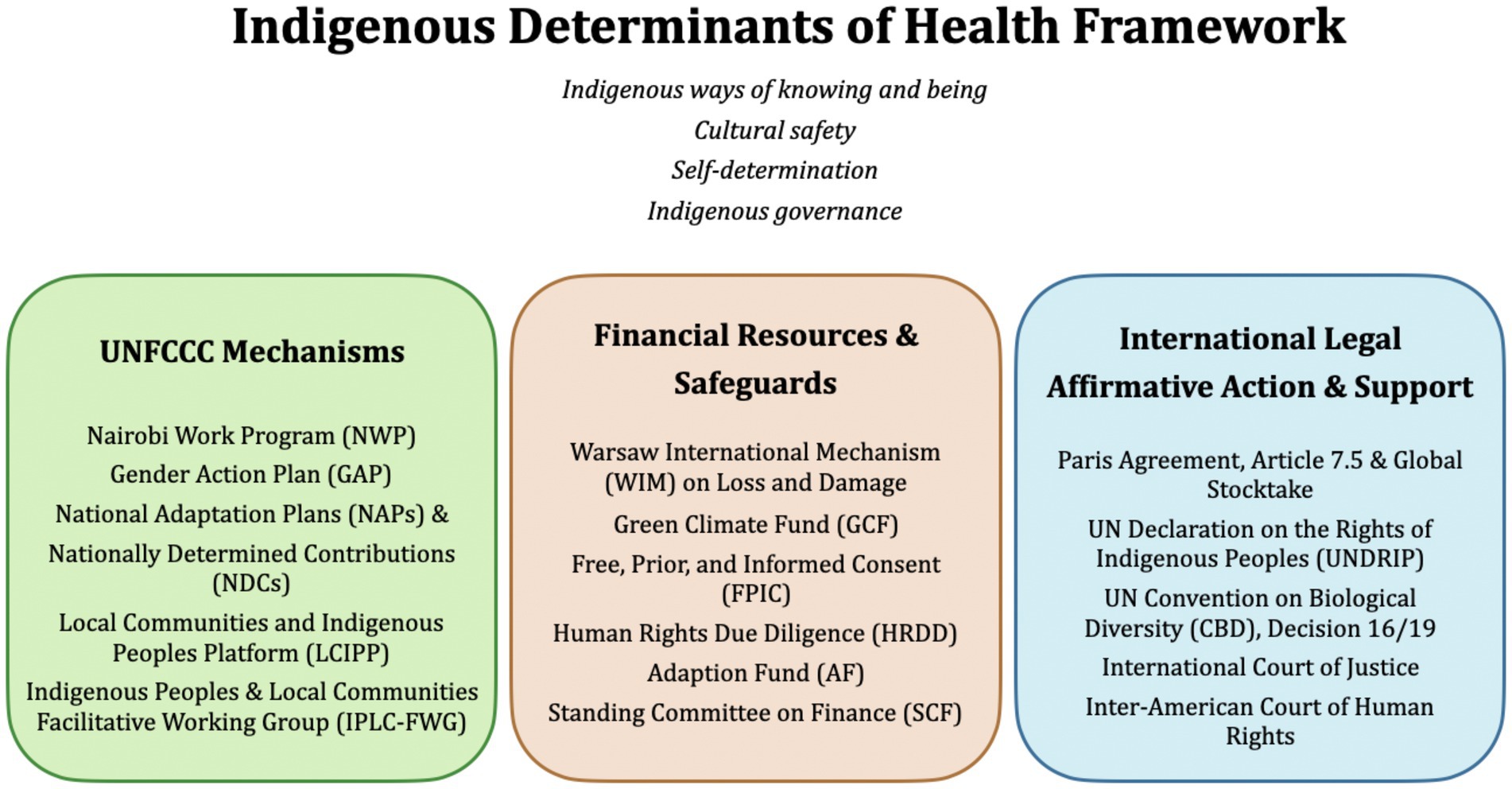

As the UNFCCC evolves, the urgency to advance Indigenous Peoples’ Rights within global climate governance has never been greater. COP 30 offers a powerful starting point to embed reforms that center Indigenous leadership, rights and knowledge systems. This article proposes integrating the Indigenous Determinants of Health (IDH) Framework into UNFCCC processes to realize Indigenous Rights as affirmed by UNDRIP and the Paris Agreement. Drawing on CBD Decision 16/19, we highlight entry points in the Global Stocktake, the Gender Action Plan and the national adaptation planning, alongside five additional mechanisms on adaptation, finance, and loss and damage. We argue the IDH provides a rights-based structure for implementing Article 7.5 of the Paris Agreement and ensuring alignment with UNDRIP, FPIC and cultural safety.

1 Introduction

The effects of climate change on Indigenous Peoples are not merely environmental but profoundly affect health, culture, and collective identity. As frontline communities in both climate impact and resilience, Indigenous Peoples experience climate-induced disruptions in food security, water access, cultural continuity, and ecosystem integrity (World Health Organization, 2025; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2024). All of which are deeply interwoven with health and wellbeing and have been increasingly recognized in multilateral policy processes, including the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Decision 16/19 (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024). These impacts compound systemic harms rooted in colonization, which dismantled Indigenous governance, severed cultural relationships with the land, and disrupted traditional economies. Colonization brought land dispossession on a massive scale, forcibly removing Indigenous Peoples from their territories and stripping away the very foundation of their health, identity, cultural practices, and survival (United Nations, 2007; Condo et al., 2023). In parallel, colonial systems-imposed policies that criminalized the practice of traditional medicine, undermining intergenerational knowledge transmission and restricting access to plants, waters, and ecosystems essential for healing (World Health Organization, 2025).

Climate-driven damage to Indigenous territories intensifies these existing injustices by disrupting the ecological and cultural systems that remain. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and biodiversity loss directly threaten the natural elements directly linked to food sovereignty, medicinal resources, and cultural practices (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2024). These cumulative ecosystem disruptions exacerbate health inequities, and limit economic opportunities for Indigenous Peoples, who have also been historically marginalized and deprioritized by global agencies and national institutions (World Health Organization, 2025; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2024). This persistent gap in institutional responses underscores the necessity of Indigenous-led solutions, such as the Indigenous Determinants of Health (IDH) Framework.

The IDH Framework, sponsored by the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), was created by Indigenous Peoples as a culturally safe, rights-based approach to address longstanding gaps in how agencies and institutions engage with Indigenous health and wellbeing across climate and environmental contexts. It represents a distinctive contribution to global climate-health governance as the first comprehensive, culturally safe, rights-based framework addressing institutional systemic changes needed, developed by Indigenous leaders from seven sociocultural regions and endorsed at the UN level as educational guidance. Unlike other holistic approaches to health, the IDH framework centers Indigeneity as a health determinant, covering Indigenous Peoples’ specific risk and protective factors; and embeds cultural safety and self-determination as guiding principles for the conceptualization, implementation, and evaluation of institutional approaches (Condo et al., 2023; Roth, 2025; Roth, 2024). This ensures that Indigenous Peoples are positioned as rights-holders rather than stakeholders, in line with UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations, 2007), the Paris Agreement (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015), and CBD Decision 16/19 (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024).

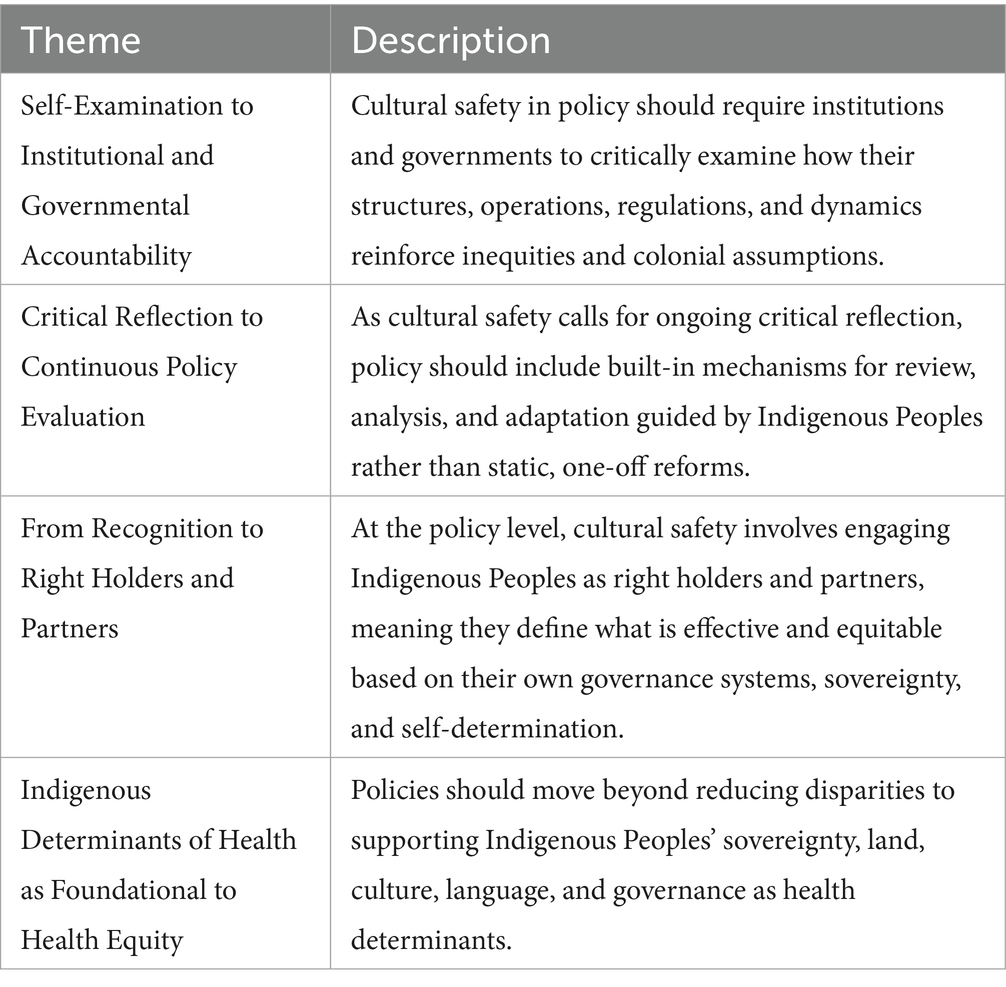

Since cultural safety has been a major concern in regard to the approach to Indigenous Peoples’ wellbeing in global health and climate change initiatives, the IDH Framework adapted the definition of ‘cultural safety’ from Curtis et al. (2025), extending beyond the healthcare workforce to focusing on institutional and governmental accountability, addressing systemic inequities, and advancing self-determination (Table 1).

Table 1. Extending cultural safety to policy within the Indigenous Determinants of Health framework [Adapted from Curtis et al. (2025)].

As such, the IDH framework offers both a guiding methodology and practical tools for systems decisionmakers and leaders to advance equitable, rights-affirming policies and action. For instance, global climate governance, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), has yet to fully operationalize frameworks that address these intersections. This article proposes the incorporation of the IDH Framework into the UNFCCC as a coherent, rights-based approach aligned with existing legal instruments.

2 Anchoring indigenous rights in climate–health governance

The Paris Agreement (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015) explicitly recognizes the rights of Indigenous Peoples in its preamble and Articles 7.5, outlining climate adaptation should be participatory, transparent, gender-responsive, and integrate Indigenous and local knowledge. UNDRIP (United Nations, 2007) affirms the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples, including rights to health, cultural integrity, and free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) (United Nations, 2007). Yet, mechanisms within the UNFCCC, such as the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP), while inclusive, have not fully differentiated the rights of Indigenous Peoples from the broader stakeholder category of “local communities.” This conflation risks diluting Indigenous Peoples’ status as rights-holders under international law, rather than simply stakeholders. However, this course can be corrected in an expedited and coherent way through the IDH Framework, which provides a rights-based methodology for operationalizing Indigenous self-determination, cultural continuity, and health within climate governance.

As a precedent, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity Decision 16/19 (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024) from November 2024, included the 2023 Indigenous Determinants of Health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development study (Condo et al., 2023) as reference in its Global Action Plan on Biodiversity and Health. The decision invited the UNPFII and Indigenous Peoples to contribute to implementation and align with Article 8(j) of the CBD (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024), which calls for respect, preservation, and maintenance of knowledge, innovations, and practices of Indigenous and local communities pertaining to biological diversity, and to foster their wider application with the approval and involvement of the knowledge holders, while ensuring equitable benefit-sharing (Convention on Biological Diversity, 1992). This CBD decision reinforced previous recommendations provided in 2023 by Indigenous leaders participating at the World Health Organizations’ Global Workshop on Biodiversity, Traditional Knowledge, Health, and Well-being (World Health Organization, Pan American Health Organization, Indigenous Determinants of Health Alliance, 2022). The workshop’s report references the IDH framework multiple times as a means to achieve a rightsbased and culturally safe approach to issues pertaining to traditional practices, climate, and the health of Mother Earth.

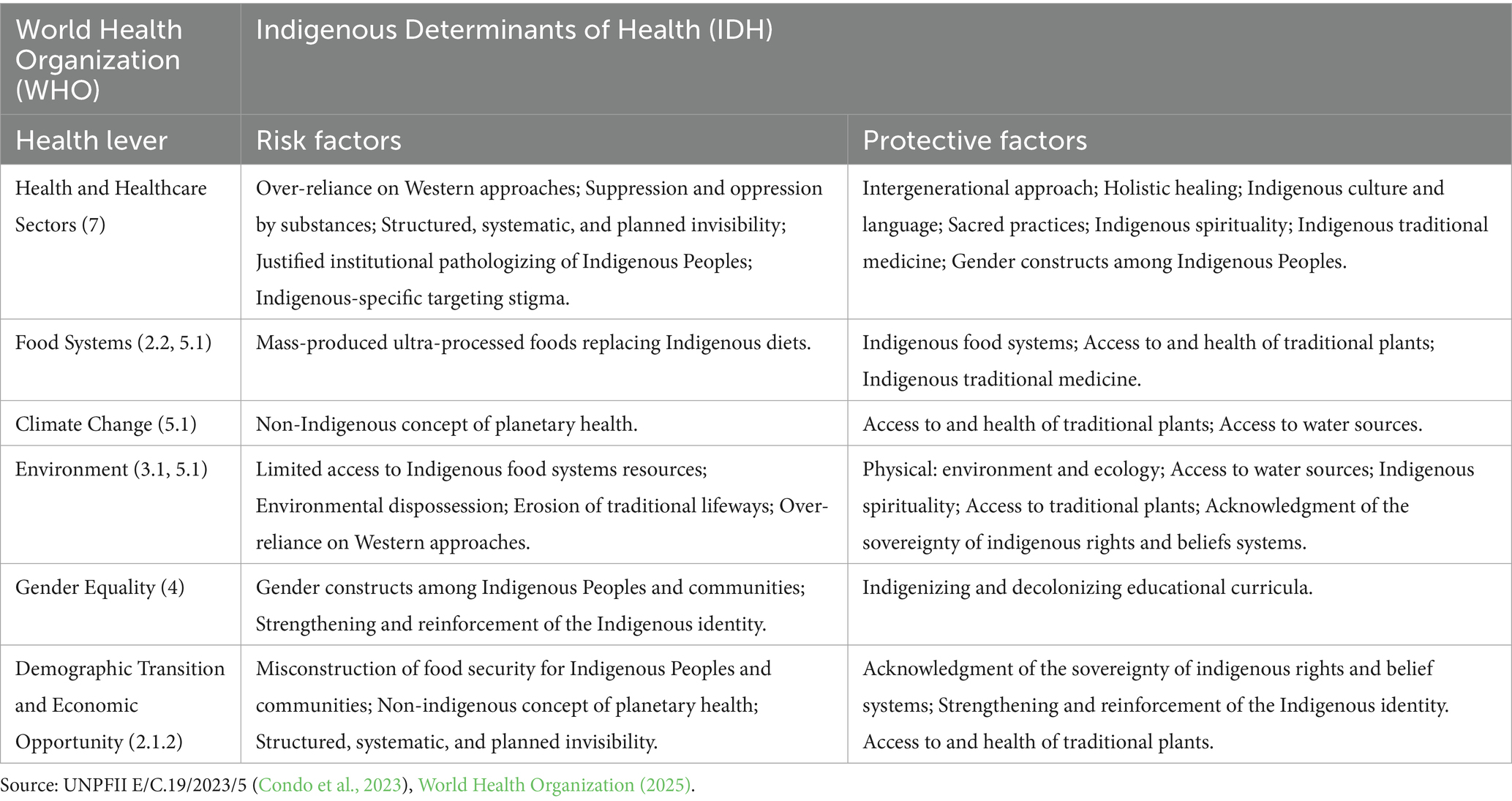

Similarly, the 2025 World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Report on Social Determinants of Health Equity (World Health Organization, 2025) acknowledges the IDH and the concept of ‘Indigeneity” as a determinant of health– encompassing unique risk and protective factors impacting Indigenous health beyond the clinical sphere. With its UNDRIP aligned foundations and culturally grounded design, the IDH framework is well-positioned to be integrated into existing global governance mechanisms covering climate, economy, culture, health, and all other aspects of life. Taken together, the recognitions by WHO and CBD set a powerful precedent for UNFCCC and other multilateral environmental agreements to formally adopt the IDH Framework as a practical tool for advancing indigenous rights in the context of climate change.

Furthermore, the IDH offers specific relevance for enhancing the effectiveness of global mechanisms. Its three studies (2023, 2024, 2025) respond to global agencies’ lack of knowledge and infrastructure in Indigenous health through 16 risk and 17 interrelated protective factors specific to Indigenous Peoples, centered around the concept of Indigeneity as a foundational determinant of health (Condo et al., 2023). These interconnected elements are not only vital to Indigenous wellbeing but also correspond with the WHO’s Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). In doing so, the studies highlight the crucial role of cultural safety, the acknowledgment of indigenous rights, and the exercise of self-determination in developing fair and culturally grounded health interventions. For instance, the Table 2 provide an example of the intersection of the WHO SDOH Equity levers with the IDH factors.

Table 2. Sample comparison between 5 of 13 proposed WHO social determinants of health equity levers and the Indigenous Determinants of Health factors.

The IDH Framework also offers a critical lens to examine emerging conceptual platforms such as the One Health frame. This approach assumes an interdependence between human, animal, and environmental wellbeing (Adisasmito et al., 2022) and has been adopted by global institutions as unifying methodologies. However, these responses do not originate from Indigenous Peoples’ epistemologies, and thus, in many aspects, fail to incorporate Indigenous perspectives. If adopted uncritically or merged with other non-Indigenous frames, there are high risks of losing the Indigenous knowledge, purpose, and meaning, therefore perpetuating exclusion and marginalization (Redvers et al., 2022). For instance, the Indigenous concept of cultural safety is of paramount importance. Unlike the concept of “cultural competency,” which often implies that one can become fully proficient in another culture, whereas cultural safety requires an ongoing process of self-reflection and accountability. It calls on individuals and institutions to examine and address structural power dynamics in every setting (Roth, 2024; Anderson et al., 2003). A growing body of Indigenous scholarship has developed practical pathways for embedding cultural safety across organizations and systems to ensure the Indigenous perspective is appropriately incorporated (Anderson et al., 2003; Roth, 2024).

Building on its initial conceptualization in 2023 (Condo et al., 2023), the framework was first expanded in 2024 to articulate the structural and systemic reforms needed to advance indigenous rights (Roth, 2024). This included policy, governance, and institutional changes aimed at supporting culturally grounded, self-determined health systems. In 2025, a new study (Roth, 2025) further evolved the framework with the introduction of an evaluation tool designed to assess how well institutions align with Indigenous health determinants. This tool supports participatory governance, affirms cultural integrity, and upholds data sovereignty—empowering Indigenous Peoples to define, monitor, and measure wellness according to their own knowledge systems and values.

With the IDH Framework now offering both structural guidance and evaluative tools, the focus shifts to how international climate mechanisms—particularly within the UNFCCC—can adopt this approach. COP30 presents a timely opportunity to begin the alignment of global climate action with Indigenous health rights.

3 Opportunities in the UNFCCC to advance indigenous rights via the IDH

a. The Nairobi Work Programme (NWP) (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2005). The NWP is the UNFCCC’s knowledge-to-action hub for adaptation and resilience, with over 450 partners contributing to knowledge sharing and exchange. NWP acts as a global platform for turning knowledge into action on climate adaptation. Its main goal is to support countries—especially developing nations, LDCs, and small island states—in improving their understanding of climate risks and crafting effective adaptation responses. By bridging scientific, technical, and socio-economic insights, the NWP helps close knowledge gaps. Starting at COP30, the NWP is expected to deepen its engagement with Indigenous knowledge systems. It could advance IDH integration by:

• Producing a synthesis report on Indigenous Peoples and climate-related health impacts.

• Partnering with Indigenous organizations and UNPFII (Condo et al., 2023) to include the IDH in thematic outputs under the health and wellbeing stream.

b. The Gender Action Plan (GAP) (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2019) At COP29. Parties extended the Lima Work Programme on Gender and mandated the development of a new Gender Action Plan to be adopted. Starting at COP 30, this updated GAP (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2019) will address implementation, gender balance, and intersectional responsiveness, including the disproportionate impact of climate change on Indigenous Peoples, as acknowledged in previous UNFCCC decisions (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2020). The IDH Framework can strengthen the GAP by introducing indicators on:

• Traditional midwifery, in alignment with the 2025 UNPFII recommendation directed to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 2025).

• Land-based healing.

• Water security, particularly for Indigenous women and caregivers (Condo et al., 2023; Roth, 2025).

c. National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015) are tools countries use to plan and report their climate actions under the Paris Agreement. A group called the Least Developed Countries Expert Group (LEG) assists the world’s most vulnerable countries in designing these plans, with a focus on issues such as gender and community vulnerability. At COP30 and subsequent negotiations, countries will discuss how to better incorporate Indigenous knowledge and rights into these plans. The Indigenous Determinants of Health (IDH) Framework provides a practical approach, enabling countries to define health priorities that reflect the worldviews, needs, and cultural values of Indigenous Peoples. Parties can:

• Use the IDH Measurement Instrument (Roth, 2025) to ensure the inclusion of indigenous rights in adaptation measures.

• Reference culturally grounded health targets aligned with article 7.5 of the Paris agreement (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015).

d. Global Stocktake GST Reviews (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015). The GST is mandated under Article 14 of the Paris Agreement to assess collective progress on mitigation, adaptation, and means of implementation. The IDH framework can be used in the adaptation and equity sections of the GST to develop measures that ensure Indigenous well- being is explicitly assessed in the global climate scorecard. This would create a systemic and periodic means to monitor Indigenous wellbeing in adaptation responses, consistent with Article 7.5 of the Paris Agreement (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015) and UNDRIP (United Nations, 2007).

e. Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) on Loss and Damage. The WIM and the new Loss and Damage Fund have increasingly emphasized non-economic losses (NELs) (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2013; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Executive Committee of the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage, 2023). The IDH could serve as a baseline for negotiations to refine the conceptualization of losses beyond the economic realm. That is, support the development of culturally relevant metrics of non-economic losses like language, spiritual ties to land, and Indigenous identity (Roth, 2025).

f. Green Climate Fund (GCF). The GCF already funds projects with Indigenous components and mandates gender and social inclusion strategies (Green Climate Fund, 2018). Entities can apply for GCF support using the IDH framework to expand the understanding of the Indigenous perspective and demonstrate impact and accountability. The IDH Framework offers a model that includes an evaluation instrument (Roth, 2025), which can support GCF’s emphasis on measurable, transformative impact.

g. An Indigenous Peoples’ separate approach in Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP) (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2024).

Similar to other UN agencies, the UNFCCC accounts for a representative mechanism that conflates Indigenous Peoples’ issues with those of other local populations, referred to as the “Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples” Facilitative Working Group (IPLC-FWG) (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2024). This conflation is not compliant with UNDRIP (United Nations, 2007) since Indigenous Peoples are rights-holders, while local communities are stakeholders. Thus, the conflation of issues dilutes the rights of Indigenous Peoples and impedes appropriate engagement and representation of Indigenous Peoples in decision-making, policy development, and initiatives implementation. While this is a significant issue and a systemic barrier for Indigenous Peoples across the UN, there is an excellent opportunity to improve the situation through adopting a rights-based approach that separates Indigenous Peoples’ issues from local communities within this mechanism. The LCIPP’s 2022–2024 work plan is set to be succeeded by a new work plan at COP30. The Facilitative Working Group (FWG) has prepared a draft third three-year workplan for 2025–2027, which is included in its latest report to the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) and is expected to be considered and adopted at COP30, and can serve as a framework for ongoing reform.

The timing is especially opportune. The LCIPP’s 2022–2024 work plan is set to conclude at COP30. The Facilitative Working Group (FWG) has already prepared a draft third work plan for 2025–2027, which will be considered by the SBSTA and is expected to be adopted at COP30. This presents a unique and immediate opportunity to embed a rights-distinctive approach within the LCIPP’s structure and deliverables. The Indigenous Determinants of Health (IDH) Framework should be adopted to guide this new approach, as it provides a culturally grounded, rights-based methodology for defining Indigenous-specific priorities in climate and health policy. Its integration would mark a shift toward differentiated, rights-affirming participation that is both legally coherent and ethically grounded, and institutionally actionable. Since major activities to promote rights-based climate policies are expected to be reviewed and expanded at COP30 as part of agreement implementation, the current LCIPP is well-positioned to incorporate the IDH Framework through:

• Technical workshops on climate–health linkages specifically for Indigenous Peoples.

• Regional dialogues on IDH-informed adaptation strategies.

• Collaboration with the UNPFII (Condo et al., 2023) and WHO to develop thematic guidance on Indigenous Peoplesled health initiatives and cultural safety.

4 COP 30 decisions - a major occasion to improve Indigenous Rights in climate change

In addition to the aforementioned opportunities, the UNFCCC can adopt enabling language that formally acknowledges the Indigenous Determinants of Health (IDH) Framework as a valuable, rights-based instrument. Doing so would signal the Parties’ readiness to integrate Indigenous worldviews, governance systems, and cultural health determinants into climate policy in a way that aligns with international legal obligations, including the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (United Nations, 2007; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024). This opportunity could mirror the decisive action taken by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which adopted Decision 16/19 to endorse the IDH Framework as part of its Global Action Plan on Biodiversity and Health (Condo et al., 2023). That decision not only acknowledged the distinct health realities of Indigenous Peoples but legitimized CBD as a policy space for Indigenous knowledge systems and determinants of health to shape implementation strategies. The UNFCCC can learn from this precedent by weaving the IDH Framework into the fabric of its existing mechanisms—such as the Gender Action Plan (GAP) (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2019), the LCIPP (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2024), and the Nairobi Work Programme (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2005)—thereby advancing indigenous rights in a practical, measurable, and culturally grounded manner.

Recent legal developments provide further justification for integrating indigenous rights into climate governance. The Inter-American Court on Human Rights’ Advisory Opinion No. 32/25 (Inter-American Court of Human Rights, 2025) from July 2025 progressively interprets legally binding obligations for states to face the climate crisis through human rights law, including Indigenous Peoples’ Rights. Moreover, the 2025 advisory opinion by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on climate change obligations (International Court of Justice, 2025) under international law confirms the legal standing of differentiated rights, including those of Indigenous Peoples. These milestone opinions underscore the obligations of states to consider the rights of Indigenous Peoples as binding legal standards, and not solely mere ethical commitments, when designing and implementing policies (Figure 1).

5 Conclusion and call to action

By referencing the IDH Framework in the COP30 decision text, Parties would enhance policy coherence across UN bodies and elevate Indigenous health priorities as central to effective adaptation. In doing so, the UNFCCC would not only respond to longstanding calls from Indigenous leaders but also demonstrate its evolving institutional maturity—one that can embrace differentiated rights frameworks while preserving unity of purpose in climate action.

COP30 offers a key political moment for Parties to:

• Endorse Indigenous frameworks like the IDH (Condo et al., 2023; Roth, 2025; Roth, 2024).

• Encourage their integration into the UNFCCC GAP (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2019).

• Recognize the distinct needs and rights of Indigenous Peoples as enshrined in international law, including UNDRIP (United Nations, 2007; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024). COP30 presents a political opportunity to introduce enabling language referencing the IDH Framework, encouraging its use within existing mechanisms without necessitating their restructuring.

Indigenous leaders—both within the UNFCCC process and across grassroots climate-health movements — are uniquely positioned to lead and drive transformation in global climate governance. Their lived experience, cultural authority, and status as rights-holders under international law equip them to articulate with precision and urgency the health needs of Indigenous Peoples in the face of climate change. By fostering the adoption of the Indigenous Determinants of Health (IDH) Framework and advocating for its adoption into core UNFCCC mechanisms, Indigenous representatives can steer climate governance toward greater accountability, cultural safety, and legal coherence. Whether through formal interventions in COP negotiations, participation in LCIPP (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2024) and SBSTA processes, or alliances with supportive States and UN agencies, Indigenous leaders can catalyze a systemic shift—one that moves beyond inclusion and toward true recognition of Indigenous Peoples as decision-makers and partners in the climate-health interface.

Author contributions

GR: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Supervision. AB: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Project administration. AA: Validation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources. LF: Validation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Investigation. MC: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Resources, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used formatting of references, narrative style, checking for accuracy, citation formats.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adisasmito, W. B., Almuhairi, S., Behravesh, C. B., Bilivogui, P., Bukachi, S. A., Casas, N., et al. (2022). One health: a new definition for a sustainable and healthy future. PLoS Pathog. 18:e1010537. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010537

Anderson, J. M., Perry, J., Blue, C., Browne, A., Henderson, A., Khan, K. B., et al. (2003). “Rewriting” cultural safety within the postcolonial and postnational feminist project. Toward new epistemologies of healing. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 26, 196–214. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200307000-00005

Condo, F., McGlade, H., and Roth, G. (2023). Indigenous determinants of health in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UPFII).

Convention on Biological Diversity (1992). Article 8(j): Traditional knowledge, innovations and practices. Montreal: CBD.

Curtis, E., Loring, B., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Paine, S.-J., et al. (2025). Refining definitions of cultural safety, cultural competency and indigenous health: lessons from Aotearoa New Zealand. Int. J. Equity Health 24:130. doi: 10.1186/s12939-025-02478-3

Inter-American Court of Human Rights (2025). Advisory opinion no. 32/25: Climate emergency and human rights. San José, Costa Rica: IACHR.

International Court of Justice (2025). Obligations of States in respect of climate change. Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports 2025, General List No. 187. The Hague: International Court of Justice.

Redvers, N., Celidwen, Y., Schults, C., Horn, Q., Githaiga, C., Vera, M., et al. (2022). The determinants of planetary health: an indigenous consensus perspective. Lancet Planet. Health 6:e156e163. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00354-5

Roth, G. (2024). Improving the health and wellness of indigenous peoples globally: Operationalization of indigenous determinants of health. New York: United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII).

Roth, G. (2025). Evaluating institutional structures to improve the health and wellness of indigenous peoples globally: The indigenous determinants of health measurement instrument. New York: United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2024). Decision 16/19: Global action plan on biodiversity and health. CBD/COP/DEC/16/19. Montreal: CBD.

United Nations (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples (UNDRIP). Resolution adopted by the general assembly, a/RES/61/295. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2024). State of the world’s indigenous peoples: Volume VI – Climate crisis. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2013). Non-economic losses in the context of the work programme on loss and damage. Technical paper FCCC/TP/2013/2. Bonn: UNFCCC.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015). Paris Agreement. FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1. Bonn: UNFCCC.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015). Paris agreement, article 14. FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/rev.1. Bonn: UNFCCC.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2019). Decision 3/CP.25: Enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender and Gender Action Plan. FCCC/CP/2019/13/Add.1. Bonn: UNFCCC.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2020). Report of the conference of the parties on its twenty-fifth session, held in Madrid from 2 to 15 December 2019. FCCC/CP/2019/13/add.1. Bonn: UNFCCC.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2024). Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP). Bonn: UNFCCC.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2005). Nairobi work Programme on impacts, vulnerability and adaptation to climate change. Bonn: UNFCCC.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Executive Committee of the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (2023). Explainer: the Warsaw international mechanism for loss and damage. Bonn: UNFCCC.

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (2025). Forum report. E/2025/43– E/C.19/2025/8. New York: United Nations.

World Health Organization (2025). World report on social determinants of health equity. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization, Pan American Health Organization, Indigenous Determinants of Health Alliance (2022). Recommendations towards a resilient future for biodiversity and human health through ancestral and indigenous knowledge systems. Report prepared under the auspices of the UN convention on biological diversity. Colombia: Cali.

Keywords: Indigenous Determinants of Health, UNFCCC, IDH framework, climate adaptation, UNDRIP, FPIC, cultural safety, Indigenous Rights

Citation: Roth GS, Bermudez Del Villar A, Amharech A, Forrest L and Carvalho M (2025) Implementing Indigenous rights through climate–health governance: advancing the Indigenous Determinants of Health framework within the UNFCCC. Front. Clim. 7:1697881. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1697881

Edited by:

Kaitlyn Patterson, Queen's University, CanadaReviewed by:

Roxana Roos, EA4455 Cultures, Environnements, Arctique, Représentations, Climat (CEARC), FranceDanya Carroll, The University of Western Ontario, Canada

Copyright © 2025 Roth, Bermudez Del Villar, Amharech, Forrest and Carvalho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alejandro Bermudez Del Villar, YWxlamFuZHJvQGNlZGFycm9ja2FsbGlhbmNlLmNvbQ==

Geoffrey Scott Roth1

Geoffrey Scott Roth1 Alejandro Bermudez Del Villar

Alejandro Bermudez Del Villar Matthew Carvalho

Matthew Carvalho