- 1Department of Public Policy and Management, Faculty of Public Policy and Governance, Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa, Ghana

- 2Department of Organizational Studies and Development, Faculty of Public Policy and Governance, Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa, Ghana

- 3Department of Environment and Resource Studies, Faculty of Integrated Development Studies, Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa, Ghana

This study explores climate dynamics and resilience of small-scale irrigation facilities in the Sissala West District of north-western Ghana. A multiple cross-sectional case study design was used. We randomly and proportionately sampled 208 small-scale irrigation farmers for the study. We used questionnaire, Focus Group Discussions, and semi-structured interviews for data collection. The quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, while thematic analysis was applied in analysing the qualitative data. The findings indicate that rainfall variability and high temperatures pose serious threats to irrigation dams and dugouts, resulting in their inability to have enough water for dry-season farming. The irrigation farmers, therefore, experienced low yields, low income, and loss of investment. Variability of rainfall, high evapotranspiration, and scarcity of irrigation water were responsible for the under-utilisation of irrigation assets in the district. Planting of trees around reservoirs; addressing erosion using vetiva grass on the embankment of the dams and dugouts, regular maintenance of lateral canals, avoidance of farming very close to the basins and river beds to the dams can address siltation. The District Assembly needs to prioritise the rehabilitation and regular monitoring and supervision mechanisms in collaboration with the user communities to promote the achievement of long-term benefits of dry season farming.

1 Introduction

Agriculture is the mainstay sector in development policies in sub-Saharan Africa (Zimmermann et al., 2009). The increasing concerns of the long-term impacts of climate variability on water availability (Akuriba et al., 2020; Kabat et al., 2003) continue to prompt a rethinking of technological and indigenous knowledge systems that are linked to issues of vulnerability, livelihood, and food security in semi-arid areas. The unpredictable and uneven rainfall patterns resulted in advocacies for irrigation development. This is particularly important as the number of countries is reaching alarming levels of water scarcity. In Ghana, as in other parts of the world, rainfall pattern continues to dwindle and are not adequate to meet the moisture requirements of crops (Darimani et al., 2021). So, irrigation becomes an indispensable opportunity for farming in arid and semi-arid regions to reduce drought. The Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) of Ghana has the mandate to promote irrigation schemes as a climate variability adaptation measure (Darimani et al., 2021). Efficient twenty-first-century irrigation systems are formidable in addressing water scarcity and food insecurity by improving crop yields (Askaraliev et al., 2024; Baldwin and Stwalley, 2022; Kpieta et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2025). Irrigation contributes to sustaining agricultural productivity (Kelley et al., 2025; Mati, 2023). Many organisations, especially multinational and non-governmental, implemented various irrigation schemes and technologies, especially in developing countries, that sought to ensure a sustainable supply of water to facilitate dry-season farming (Ahmad et al., 2021; Food and Agriculture Organisation, 2013; Tsegaye et al., 2013b). Simonet and Rajendran (2025) studied smartphones for estimating the timely application of water for irrigation to forestall water loss. This utilises automated systems to conserve water by providing it directly to the plants and adjusting irrigation to the specific needs of the crops.

Many studies (Askaraliev et al., 2024; Ahmad et al., 2021; Akurugu et al., 2019; Mushtaq et al., 2013; Saleth et al., 2011) looked at different aspects of the linkage between climate variability and irrigated agriculture. These studies focused on the environmental impacts of irrigation on climate variability in terms of water use reduction, greenhouse gas emission, and carbon sequestration. Other studies have assessed socioeconomic dimensions such as food security, reduction in vulnerability, incomes, and sustainable livelihoods as well as institutional arrangements for sustainable agriculture (Amede, 2014; Abdelsalam et al., 2014; Bar et al., 2015; Zimmerer, 2011). In most of these works (Askaraliev et al., 2024; Ahmad et al., 2021; Amede, 2015; Bar et al., 2015; Abdelsalam et al., 2014; Zimmerer, 2011), the consensus is that irrigation has positive feedback to climate variability from environmental, economic, and social perspectives. Some of these studies looked at unidirectional influences of climate variability on irrigated agriculture as a best adaptation strategy (Ketchum et al., 2023; Ahmad et al., 2021; Adamson and Loch, 2014) with little attention paid to climate variability and its effects on small-scale community-based irrigation dams and dug outs in the District and the policy implications for unlocking small scale irrigation farmers’ resilience.

2 Climate variability and small-scale irrigation farming and irrigation governance: a literature review

Africa’s irrigation potential is estimated at 42.5 million hectares, yet, in sub-Saharan Africa, less than 4% (6 million hectares) of the cultivated land is irrigated compared to 37% in Asia and 14% in Latin America (Ringler, 2017). The reasons for the untapped potential are due to a complex mix of factors, including investment cost, poor planning, inconsistencies between farmers’ needs and irrigation schemes, poor maintenance culture, and inefficient local management institutions (Ringler, 2021).

In Ghana, despite substantial potential for advancement in irrigation and the emphasis placed by national development plans, just close to 2% of the total potential arable land in Ghana is irrigated (Baldwin and Stwalley, 2022). Approximately, Ghana’s irrigation potential ranges between 0.36 and 1.9 million hectares, while a little over 33,000 hectares are irrigated (Akurugu et al., 2019). It has also been noted that less than one-third of the irrigated land in Ghana is captured under 22 public irrigation schemes. Very little is known about the management practices of the two-thirds remaining informal irrigation schemes (Baldwin and Stwalley, 2022). Informal irrigation schemes fall within 786 small reservoirs and 2,606 dugouts in the country, many of which are not well governed because of lack of any well-organised, effective, and efficient Water Users Association (WUAs) (Bonye et al., 2021). The few irrigation infrastructure facilities in the communities that have WUAs also suffer dysfunctional nature of such governance arrangements because they were improperly constituted, or key members have either retired or left the communities without any replacement being done. WUA conflicts stemming from power struggles, unfettered rivalry, and financial malfeasance are other problems that plagued the WUAs. Where there was a reversal of the WUAs’ irrigation governance situation, as in the case of a few other irrigation communities, the sustainability of irrigation infrastructure was guaranteed, and the irrigation activities of farmers were deemed very effective, rewarding (Akurugu, 2007).

It is also noteworthy that apart from the few irrigation infrastructure facilities that were initiated by the central government through the Ghana Irrigation Development Authority (GIDA), which is now part of the Ministry of Agriculture, the rest of the small-scale dams and dugout projects were initiated by Community-Based Organisations (CBOs), Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs) through donor support arrangements. Out of this, there are 84 small dams and 54 dugouts, which are informal irrigation schemes in the North-western enclave of Ghana covering a land mass of 712 hectares (Namara et al., 2011). Within the informal irrigation systems, the justifications are based on food security and rural employment, especially in north-western Ghana, which is characterised by mono-modal, highly variable rainfall distributions (Akurugu et al., 2019; Namara et al., 2011). Darimani et al. (2021) noted that the climatic environment in the Upper West Region is seasonal in terms of rainfall and daytime temperature. The dry season period from November to March produces a soil deficit of available water of up to 61% in January to 76% of total available water in March, creating a water deficit that does not support sustained crop growth (Darimani et al., 2021).

The Sissala West District, located in the Upper West Region of Ghana, is associated with unimodal rainfall, short duration of precipitation, and rapid, significant evapotranspiration, making just 4 to 5 months of farming and 7 to 8 months of excruciating dry season, the usual situation. The amount of rainfall recorded was pegged at 964.5 mm as of the year 2000, with a maximum temperature of 35.4 °C. In 2010, the total annual rainfall recorded 1167 mm with a maximum temperature of 35.5 °C, and in 2022, the total rainfall recorded 1037.4 mm and a maximum temperature of 35.7 °C (Ghana Meteorological Agency, 2024). The annual rainfall is gradually decreasing with increasing temperature over the past several decades to date. These increasing temperatures possibly increase the rate at which surface water bodies dry up and affect irrigation activities (Dakpalah et al., 2018). This erratic rainfall does not support small-scale irrigation farmers in their desire to increase agricultural activities, which could enable them to produce sufficient food to support their households and also sell some of the produce to earn income, which may alleviate their poverty (Sissala West District Assembly, 2016). The erratic pattern of rainfall in the District results in water shortages. The incidence of the wet season, which usually begins late in May, ends in September, while the prolonged dry season begins from October and ends in April. Marked shifts in these two periods are very common. The causes of variable precipitation and temperature in the area described as north-western Ghana (the Upper West Region) have been variously discussed (Derbile et al., 2022). This accentuated the need for small-scale irrigation infrastructure, which could promote irrigated farming since rain-fed agriculture alone has failed to support agricultural activities in the region (Dakpalah et al., 2018) and make farmers more resilient. Akuriba et al. (2020) said this led to a call for participatory approaches in irrigation services and facility management. This creates Community-Based Irrigation Schemes (CBIS) for irrigation farmers who have irrigated plots. These CBIS are owned by individual farmers or groups who form Irrigation Water Users Associations (IWUAs) or Water User Associations (WUAs) as cooperatives or self-help groups (Mati, 2023). The IWUAs or WUAs are the beneficiary irrigation farmers, and they co-manage irrigation facilities by paying for the costs of irrigation services and providing labour for the maintenance. This approach transfers authority to IWUAs or WUAs. This creates farmer-led irrigation where the IWUAs or WUAs assume a driving role in improving their water use for agriculture through changes in knowledge production, technology use, investment patterns and market linkages, and the governance of land and water (Katic, 2024). Through this, small-scale reservoirs can avoid the governance challenges in irrigation schemes. This is particularly important where many small reservoirs in the Upper East Region were not in use due to the absence or weak IWUAs or WUAs (Akuriba et al., 2020). Notwithstanding the crucial roles IWUAs or WUAs play, Mati (2023) said the IWUAs or WUAs are not recognised in policies and institutions responsible for irrigated agriculture; they equally miss out on policy support, resource allocation, and planning alongside other sectors.

In order to strategically increase agricultural production, promote real poverty reduction through building the resilience of farmers in the Sissala West District against climatic adversity, the Government of Ghana, Community-Based Organisations (CBOs) and Nongovernmental Organisations (NGOs) have provided some irrigation facilities in the District. Thus, there are 84 small-scale dams and 54 dugouts in the Upper West Region and out of this number, the Sissala West District has only 10 small dams and 5 dugouts (Kpieta et al., 2013), which are woefully inadequate to serve the agricultural needs of the inhabitants. Climate variability affects rainfall patterns, causing the drying up of these dams (Slegers, 2008; Tsegaye et al., 2013b). Many of these small dams and dugouts in the District use the gravity method, which is cheaper as compared to the non-gravity method. This system equally uses constructed wells or tanks and open water distribution methods, which are associated with significant water loss through evapotranspiration (Sissala West District Assembly MoFA, 2024). In their quest to speed up irrigation farming, the farmers have adopted the gravity method of irrigation, which depends highly on the size and depth of water in the reservoir. However, the water levels of the reservoirs usually fall beyond the requisite levels because of poor rainfall, which limits and affects the use of the gravity system for irrigation activities within the area (Sissala West District Assembly MoFA, 2015).

A review of irrigation practices in Ghana by Namara et al. (2011) concluded that even though just a small area in Ghana is irrigated, there is yet to be a consensus in research regarding where various irrigation technologies are applied. Notwithstanding this, Kpieta et al. (2013) concluded that households and communities have achieved livelihood improvement through small-scale irrigated agriculture, and recommended an intensification of the construction of dams. Akurugu et al. (2019) also noted fair positive results in poverty reduction arising from irrigated agriculture and recommended initiatives to increase farmers’ access to farm credit, technical assistance, and high-yielding seed varieties, as well as expanding access to a ready market for their produce. Several attempts by the Government of Ghana and NGOs to develop and manage irrigation facilities for effective and efficient agricultural production in the Sissala West District have not been as robust as compared to the escalation of challenges due to climate variability and its effect on irrigation activities. Irrigation water management technologies are crucial for an increased net farm income, and yet, farmer-led irrigation technology acquisition remains a major challenge (Katic, 2024).

This paper contributes towards expanding the existing knowledge of the nexus between climate variability and small-scale irrigation farming by comparatively assessing different sites in the Sissala West District.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study context

The area studied is the Sissala West District, which lies within the northwestern part of the Upper West Region of Ghana between Longitudes 2° 13΄ W and 2° 36΄ W and Latitudes 10° 0΄ N and 11° 0΄ N. The study area is one of the 11 local government Districts and Municipalities in the region. It shares common boundaries with the Lambusia-Karni District and Jirapa Municipality to the West, Daffiama-Bussie-Issah in the South-West, Sissala East District in the East and Burkina Faso in the North as well as Wa East District South of the region. The area constitutes 22.3 percent of the landmass of the Region, The District used to be part of the Sissala East Municipality, but, gained its new district status in 2004 with its administrative capital located at Gwollu, a historical town noted to have mounted very strong resistance to slave raiders and defeated them. Figure 1 shows the district locational context highlighting the six selected study communities with the highest number of irrigation farmers in the district based on data provided in Ministry of Food (MoFA) of Sissala West District Assembly MoFA (2023).

Figure 1. Map of Sissala West District showing the studied communities. Source: Authors’ construct based on Ghana Statistical Service (2012) and Sissala West District Assembly MoFA (2023).

The estimated population of small-scale irrigation farmers was 433 people.

The sample size consisted of 208 irrigation farmers, determined using sample size formula by Yamane (1967). The sampling error was 5% and the confidence level of 95%. A proportionally representative sample was chosen for the 6 selected communities based on the small-scale irrigation farmer population in each community. Thus, the study selected 60 out of 124 irrigation farmers in Pulma, 49 out of 103 irrigation farmers in Nimoro, 23 out of 48 irrigation farmers in Bouti, 36 out of 76 irrigation farmers in Jawia, 22 out of 45 irrigation farmers in Nyimeti and 18 out of 37 irrigation farmers in Kupulima.

3.2 Data collection and handling

The study adopted both explanatory and descriptive methods in achieving the research aim. The description technique focused on ethnography to collect qualitative data. This provided context-specific (practical) knowledge rather than knowledge based on just theory (Yin, 2003, 2014; Ylikoski, 2019; Denscombe, 2021). It also provided insight at all stages with rich raw materials for advancing theoretical ideas. Though case studies are limited in terms of generalisation (George and Bennett, 2004; Ylikoski, 2019), they contextualise the issues more concretely (Flyvbierg, 2006; Ylikoski, 2019), thereby providing a basis to critique and test existing theories. A six-location cross-sectional case research approach was applied in the field to collect primary data. The criteria used for selecting case study areas included currently operational irrigated areas that were the largest irrigation schemes in the district. The merit of a multi-case study approach is that it enables the researcher to conduct a thorough comparative analysis without detaching the research problem from the context (Yin, 2011, 2017). Thus, the researchers had the chance to select a choice of criteria other than random assignments (Dinardo, 2008). This meant that irrigation sites that met the criteria were chosen for the study in the district. Primary data were generated from small-scale irrigation farmers through a cross-sectional survey using questionnaire administration. Semi-structured interviews and Focus Group Discussions were also conducted to obtain nuanced qualitative data. This helped to unearth the lived experiences and sentiments of the irrigation farmers about their irrigation livelihood under variable climate. Five Focus Group Discussions (FGD) were conducted in five out of the six communities with small-scale irrigation dams. This tool of data collection was used to enrich the data on irrigation farmers’ opinions and experiences of their past and current circumstances. Such special group discussions, specifically, were held with small-scale irrigation farmers. One focus group discussion was held in Pulma, Bouti, Nimoro, Jawia and Kupulima communities. Two of these FGD were for females only, while the other three of the FGD were conducted with male farmers only, who were into small-scale irrigation farming. The group size was maintained at eight participants, while the sex segregation of the farmers was done to ensure active participation of all group members. Thus, a total of 40 irrigation farmers, comprising 16 females and 24 males, participated in the Focus Group Discussion sessions. In all five discussion sessions, male farmers dominated because many of the males in the study locations would usually give out their plots of irrigated land to their male children to manage rather than their daughters, which corresponds with the findings of Aasoglenang et al. (2013). The discussion during the FGD covered questions on small-scale irrigation farmers’ knowledge and experience of variable climate, the effects that variable climate brought upon their irrigation activities, and the development challenges that they have experienced with their small-scale irrigation facilities. The participants were mostly middle-aged men and a few others in their early twenties. These sessions provided an avenue to validate and fill in gaps created during the administration of questionnaires.

3.3 Data analysis

The primary data that were collected with the aid of the survey questionnaires included climatic and non-climatic data, such as challenges of the development of small-scale irrigation dams and dugouts. These data were coded, and a data matrix was created with the help of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. The variables were categorised and measured. Tables and charts were then applied to analyse the data. The primary data generated from in-depth interviews and Focus Group Discussions were organised according to distinct, related, relevant themes that emerged on the subject matter of the study.

4 Results

Demographic attributes of respondents’ male irrigation farmers dominate (63%) compared to the females (37%) in the Sissala West District. This is because farmland is traditionally vested in the hands of males, whereas most females only play an assistance role to their husbands on the farms. Respondents’ ages were between 18 years to about 60 years. A greater percentage of the respondents (40%) were within the 29–39 years age group, with just a few (27.4%) between the ages of 40–50. Also, the ages 18 to 50 years indicate the active labour group, and they are the majority when combined. This certainly implies employment, household income and migration. Small irrigation serves to retain the youth in dam communities during the dry seasons.

The majority of the respondents (63%) indicated that they have no formal education, whereas a few (22%) asserted that their highest level of education attained is that of either basic or Junior High School (JHS) level. A few respondents (11%) attained middle or High School. Only 4% of them attained a tertiary level of education, yet, practice irrigation farming. The majority of the respondents (86%) are married, and few (14%) are single. The average household size was six people.

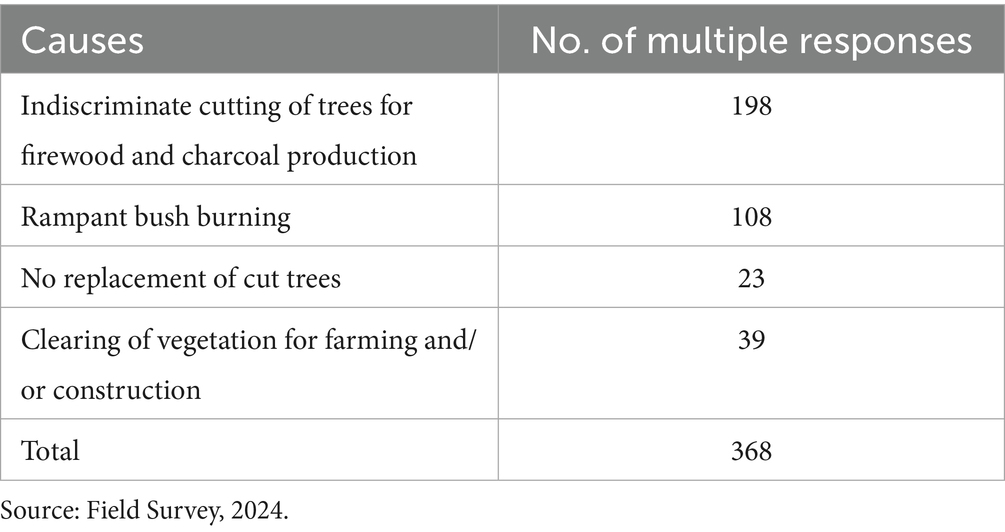

Respondents gave a variety of causes of climate variability in the Sissala West District as detailed in Table 1.

As indicated in Table 1, the dominant causes of climate variability were indiscriminate cutting down of trees for firewood and charcoal production. This was followed by rampant bush burning. The next cause of the climate variability that the respondents identified was the clearing of vegetation for farming and/or construction purposes.

The chairman of the small-scale irrigation farmer group Jawia had this to say: ‘… some community members who are not irrigation farmers farm and burn bushes around the reservoir.’

Another interviewee said

non-irrigated farmers always argue that we have started farming on these irrigated lands before the construction of the irrigation site. So, irrigation farmers cannot determine the farming practices to us. When clearing my farm, I will burn the debris and not stop because I share boundary with the site for irrigation farm’ (Nimoro Irrigation Chairman, February 2024).

This shows that the small-scale irrigation farmers attribute climate variability to human-inducement such as farming around dams and bush burning around irrigated sites destroy irrigation pipes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A broken irrigation water supply pipe at the Nyimati community irrigation site. Source: Field Survey, February 2024.

4.1 Effects of climate variability in the Sissala West District

Respondents noted that climate variability negatively affects small-scale irrigation farming and creates adverse weather conditions. The farmers gave evidence of climate variability in the study area, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Effects of climate variability and general weather conditions in the Sissala West District.

In Table 2, the dominant evidence of climate variability in the study locations has been hot temperature conditions, whereas the less visible and sighted evidence were late onset of rains, shorter duration of rains, as well as cloudy weather conditions and cold weather. They concluded that climate variability not only affects water resources but also the demand for water and other weather conditions. Increasing availability of water and food security depend, among other factors, on climate variability and the demand for water for irrigation purposes. The Sissala West District is mostly dry and warm from September to April; hence, decreased water availability usually exacerbates the problem of crop water stress. In addition to dusty and poor weather conditions, which negatively affect the health of members of smallholder farm households.

4.2 Effects of climate variability on small scale irrigation dams

The study found variable climate effects that respondents outlined in relation to small-scale irrigation dams in the Sissala West District. The respondents (73%) reported low water levels of dams as the greatest effect on irrigation farming. This was followed by 19% of them who noted high temperature levels, while 8% of them indicated fluctuation in rainfall patterns (rainfall variability). This shows that in recent times, due to increasing changes in climate-related factors, water levels of the reservoirs have reduced drastically during the dry seasons. This is because of short rainy periods, high temperatures and high sunshine, which cause excessive evaporation of water in the irrigation dams. Temperatures usually rise above the normal levels to between 37 °C and 42 °C, causing excessive heating of the earth’s surface and water bodies (irrigation dams) in the district. The variability in rainfall and extreme evaporation caused the low level of water in the dams and dugouts. The erratic, shorter, delayed or early rainfall patterns lead to low levels of water supply to irrigation dams and other reservoirs.

4.3 Effects of low water levels of dams on irrigation activities in the Sissala West District

Irrigated crops require an appropriate supply of water at all times, as occasioned by high levels of evapotranspiration due to excessive temperature. Table 3 shows the effects of inadequate water in irrigation facilities in the Sissala West District.

As shown in Table 3, all the respondents were of the view that the major effect of low water levels of their dams and dugouts is that it makes their farming less productive, due to inadequate rainfall in the Sissala West District. Reservoirs and other water bodies often dry up because of irregular precipitation patterns and longer dry spells in the area. The less dominant effects mentioned by respondents included dry farm lands (23%) due to inadequate availability of water supplied to the crops, the crops experience water stress, wilt and die (12%), and lack of water in wells, which compels farmers to incur a lot of cost in deepening the wells to reach the low water table (18%) were the least effects. Sissala West District Assembly MoFA (2024) upheld that the low water levels of reservoirs are due to rainfall variability (late and shorter rainfall patterns), which hugely affects irrigation activities in the study area.

The irrigation farmers also noted that rainfall in the district is erratic in nature, low and short in duration. A male discussant said:

We farmers rely on irrigated crops to turn the year round, but, because we do not get adequate rain in most of the years in recent times, our dams and dug outs do not store enough water for us to irrigate our plots of land (67-year-old male irrigation farmer at Nimoro, May 2024).

A female interviewee at Bouti community gave a narrative as follows:

Most of the times, we start irrigating the crops, they grow nicely and showing great hopes of a good harvest, but shortly, the water in the dams dry out. We then are compelled to compete with livestock for the small water remaining until the whole water basin dries out and cracks. At this time, the lack of water and the high intensity of the temperature makes the crops to die (48-year-old female irrigation farmer, Bouti community, May, 2024).

Figure 3 captured the opinions of the farmers regarding the percentage of rainfall in various months each year in the district.

From Figure 3, rainfall in the Sissala West District generally starts from April and ends in September each year. However, the results of the Focus Group Discussions show that majority of the discussants (32%) thought that much of the rain in the district falls between May and September, followed by 29% of them who noted that much of it falls between April and August and 19% of them indicated that the months in which more rain is experienced is from May to August. A negligible percentage of the Focus Group Discussants (7, 6% and another 7%) argued that the period within which more rainfall is experienced is April to September, May to July and June to September, respectively.

In an interview with a male irrigation farmer who has been farming for the past twenty years, he has the following to say with respect to rainfall in the area:

The rains have been failing us for a very long time. They come late and end early. In some years, it rains so much and at a time that we do not need much of it. Other times, when we need the rain so much, it either does not rain or very little of it is experienced (59-year-old male irrigation farmer, Jawia community, May 2024).

The farmers concluded that the erratic rainfall not only cause low levels of water in the reservoirs of dams and dugout but also dry-up farm lands and deaths of plants leading to less productive business in irrigation farming in the District.

4.4 Effects of rainfall on irrigation farming in the study communities

Figure 4 demonstrates a generally marked variability of rainfall and temperature in the study district from the year 1990 to 2020.

Figure 4. Rainfall and temperature trends in Sissala West District. Source: Based on Ghana Meteorological Agency data, 2024.

From Figure 3, years of decreased rainfall were also associated with a dip in mean temperature. Also, temperatures fell at a decreasing rate until 2001 and continued falling until the year 2004. Temperatures increased slightly in 2005, after which they decreased drastically in 2006 and again increased significantly in 2007 and began decreasing at a decreasing rate until 2009. The years 2009 and 2010 experienced an increase in temperature rates, whereas temperatures fell at a decreasing rate up to 2012. It again increased in 2013 and fell drastically in 2014. The meteorological data corroborated the evidence that smallholder irrigation farmers presented about climate variability in their locations.

All vegetables and crops require a wet, conducive environment to thrive well and produce good yields. The pre-eminent water source that dams and dugouts collect water for irrigation purposes is precipitation. Insufficient precipitation and water storage in dams and dugouts adversely affect irrigation activities because the supply of water is not guaranteed, and this leads to poor yields. The main problem of both farming and irrigation farming is insufficient rainfall in the district. Erratic and inadequate supply of water at all phases of crop cultivation, especially at the growth, flowering and fruiting stages, leads to the plants wilting. Extended periods of this situation result in huge yield losses and sometimes total crop failure. This implies that in order to forestall such losses, irrigation water requirements have to be pre-determined to facilitate effective design of the irrigation facilities and also follow planned water supply schedules.

The study concluded that variability of rainfall and temperature causes insufficient precipitation and water storage in dams and dugouts which adversely affect the irrigation farming in Sissala West District.

4.5 Effects of high temperature levels on reservoirs

Irrigation farmers in the study communities reported that temperature has been generally variable over the past 5 to 10-year period. The findings show that about a half (49%) of the respondents revealed that temperatures often rise very high, whilst others (9%) stated that temperatures are decreasing. Another 42% of them indicated that the average temperature increases in some years and decreases in other years. They added that the period from February to early April is usually associated with very high temperatures.

During irrigation farming in the dry season, there are usually higher temperatures with minimal daily fluctuations. Also, there is usually moderate humidity close to the maturity stages of cultivated vegetables. These climatic conditions are very appropriate for the vegetative growth of the crops. However, temperature patterns of the Sissala West District, which range from a minimum temperature of 30 °C to a maximum temperature of about 39o cause evaporation of reservoirs (Ghana Meteorological Agency, 2024). Inadvertently, the higher temperatures cause evaporation of reservoirs of the dams and dugouts causing scarcity of water for irrigation farming in Sissala West District.

4.6 Effects of temperature on crops and vegetables

Even though temperature affects various types of crops differently, generally, water stress coupled with high temperature negatively affects plant growth and yield. Table 4 shows the effects of high temperatures on irrigated vegetables in the Sissala West District.

From Table 4, respondents revealed that the dominant effect of high temperatures is that they cause crops to wilt and/or die in the district. The less visible effects of high temperatures on crops and vegetables include a reduction of water levels in their reservoirs, which impedes the regular supply of water to their irrigation farms to keep the lands wet and moist for proper crop growth.

A female discussant said the major effect of warmer temperatures during the reproductive stages of the development of vegetables and other crops is that they wither (Officer, MOFA, Sissala West District, February 2024).

A male interviewee said:

Plant growth trends are influenced by the temperature within the area where they are cultivated. The fact that specific plant species thrive well at specific temperature ranges, any extreme temperature rates cause low crop growth and death (39-year-old male irrigation farmer in Kupulima community, February 2024).

This frequent watering required by plants is usually challenging since the water will have to be carried from longer distances through local canals to the irrigated sites. This shows that high temperature causes poor growth of vegetable crops cultivated and drying up of farm lands. Frequent watering is required by plants, but is usually challenging since the water has to be carried from longer distances through local canals to the irrigated sites. This is particularly the case where the dry season irrigation usually requires a lot of water to enable the plants to cope with the high temperatures; otherwise, this results in low growth of vegetables and crops. From the findings, the study concluded that the higher temperatures have debilitating effect on maturity stages of cultivated vegetables in Sissala West District.

4.7 Effects of variable climate on smallholder irrigation

In a multiple response, respondents revealed that low water levels of reservoirs as a result of rainfall variation and high temperatures affect irrigation farming in the Sissala West District. Thus, 197 respondents reported low irrigation farm yields, 189 of them mentioned loss of investment, and 201 of them reported low income earned at the end of irrigation agriculture in the long period that the area does not experience precipitation. The dominant effect of inadequate water in the reservoirs is manifested in low farm yields in the Sissala West District.

An interviewee at Pulma said

A few irrigation farmers are sometimes lucky to harvest early, even though they experience low yields. However, the majority of us usually lose our investments and the rest of the subsequent months, it becomes difficult for us, especially with feeding and repayment of our debts (50-year-old female irrigation farmer, Pulma community, May 2024).

A key informant stated that

Since the rate of plant growth is dependent on the temperature surrounding the plant and each species has a specific temperature range represented by a minimum, maximum and optimum to which it can thrive, plants due to excessive temperature rates usually require a lot of water to cope with the high temperatures else it results in low growth of vegetables and crops (Field Officer, Sissala West District Assembly MoFA, 2024).

This implies that the inadequate water in the reservoirs results in a shortage of water to irrigate crops and vegetables at the irrigation site. Loss of investment is one of the significant causes of inadequate water in the reservoirs. This is also linked to variations in weather patterns in the Sissala West District. Farmers invest so many resources into small-scale irrigation farming activities, but at the end of the irrigation season, they cannot break even or realise what they have invested. Another visible effect of low water levels in reservoirs is low income earned by small-scale irrigation farmers because of low irrigation farm yields in the Sissala West District. From the findings, the authors concluded that climate variations cause drying up of reservoirs of dams and dugouts leading to low irrigation farm yields, loss of investment and low income earned from the irrigation faming in the District.

4.8 Strategies that smallholder irrigation farmers adopt to withstand climatic extremes

The study revealed that apart from mulching their crops, early planting of crops immediately after the rainfall season is over, planting of trees around reservoirs, checking erosion using vetiva grass on the embankment of the dams and dugouts, maintaining the lateral canals regularly, and avoiding farming closer to the basins and river beds of the dams were some measures to the siltation. Other small-scale irrigation farmers in the Sissala West District rely on the use of local canals, water hoses, pipes and local wells to channel water to their irrigation farms, as shown in Figures 5, 6.

Figure 5. Irrigated tomatoes and pepper fields at Nimoro community. Source: Field Survey, February, 2024.

These strategies that smallholder irrigation farmers adopt to withstand climatic extremes help reduce the losses of water. The irrigation farmers dig and use local wells to be able to generate, store and channel water to their various farms to facilitate crop growth. Others adopt strategies such as a water hose to channel water from the constructed wells or water sources onto their farms for watering of crops. So, until the human activities that trigger erratic rainfall and high temperatures are curtailed, irrigation farming will continue to be a dicey livelihood enterprise. The study concluded that the small-holder irrigation farmer employ various strategies to withstand climatic extremes, but they require support to unlock the resilience of these strategies.

5 Discussion

The study found that the Sissala West District is experiencing climate variability due to human-induced factors, including indiscriminate cutting of trees for construction, firewood and charcoal, rampant bush burning for farming activities (Akurugu et al., 2019; Askaraliev et al., 2024; Mushtaq et al., 2013) heightens climate variability in the district. The study adds to the findings of Kpieta et al. (2013) that poor harvests are the result of erratic elements of the weather, as well as an increase in the incidence of crop diseases and destruction by pests. The findings of Namara et al. (2011) have confirmed that environmental degradation is a cause of climate variability, which results in reduced arable land, low soil fertility, less precipitation, high temperatures and negative impacts on labour available to work.

The study also confirms the conclusions of Ringler (2017) and Derbile et al. (2022) that Africa is losing its forest lands every year due to excessive clearing of vegetation for the establishment of farmland. The wanton harvesting of trees for charcoal production and cultivation of crops, as well as bush burning, have had remarkable negative impacts on the green economy, contributing to increasing local average temperatures.

The implications of rainfall variation in the Sissala West District are the low water in dams and dugouts, which affects healthy crop growth. Excessive water also reduces the yield of some crops, while surface runoff that could have been stored for dry season farming is wasted, which confirms the findings of Sissala West District Assembly MoFA (2024). Irrigation crops have a serious vulnerability to extreme weather variation, since the main climate elements influencing the availability of water and its usage for irrigation purposes depend on rainfall, air temperature, and sunshine (Kelley et al., 2025; Mati, 2023; Tsegaye et al., 2013a). Any time there are substantial rainfall patterns in the Sissala West District, it increases crop yields. Proper distribution of rainfall coupled with the right air temperature and measured sunshine enhanced yields of the farmers (Darimani et al., 2021; Simonet and Rajendran, 2025). This is important, particularly because the growth of the crops is influenced by the availability of the right quantity of soil moisture and the general fertility of the land (Simonet and Rajendran, 2025). There is no doubt that in dry lands that are mostly dependent on rain-fed agriculture, irrigation opportunities significantly help farming communities to properly cope, adapt and build resilience against the adverse effects of global warming on the cultivation of crops all year long (Askaraliev et al., 2024; Antwi-Agyei and Nyantakyi-Frimpong, 2021). However, rising levels of water scarcity due to climate variability and change as well as poor irrigation infrastructure governance exhibited by Irrigation Water Users (Bonye et al., 2021) as a result of lack of effective and efficient maintenance regime resulting broken irrigation water distribution pipes, unequitable distribution of irrigation water among a host of other issues identified by this study, and increasing water requirements from other sectors placed smallholder irrigation water services under intense pressure (Ringler, 2021; Baldwin and Stwalley, 2022). This has made irrigation farming, as a supplementary livelihood activity, a shaky economic venture for such farmers in the Sissala West District. This situation was also reported by Dakpalah et al. (2018). The analysis of data shows that the annual rainfall pattern has been fluctuating in the Sissala West District across all years from 1990 to 2020 (Ghana Meteorological Agency, 2024).

Similarly, the finding in Figure 3 shows that in the summer (November–April), which is the dry season, the temperature rises above the normal average daily temperatures. This causes evaporation of the water in the reservoirs of dams, leading to low levels. During winter (May–October) from the year 1990 to 2020, the temperature fluctuates to show the variation in the Sissala West District (Ghana Meteorological Agency, 2024). The low water level of reservoirs is due to variations in weather patterns (Kelley et al., 2025; Mati, 2023; Akuriba et al., 2020; Akurugu et al., 2019) in the Sissala West District. So, during this period of high temperature, the cultivation of vegetables is seriously limited by reduced water levels in the reservoirs. Also, the incidence of crop diseases and pests causes a significant reduction in yields and farmers are compelled to either borrow money at high interest rates to procure agro-chemicals to enable them to mitigate their losses. The consequence is that the farmers invest in small-scale irrigation farming activities and cannot recoup their investment or break even. The findings in this study, therefore, build on the works of Ahmad et al. (2021), Mushtaq et al. (2013), as well as Saleth et al. (2011), that high temperatures, usually as a result of excessive sunshine, cause plants to wither or experience low growth with poor yields.

The consequences of the climate variability left farmers with no option (Mati, 2023; Derbile et al., 2022; Ahmad et al., 2021; Amede, 2015; Askaraliev et al., 2024; Bar et al., 2015; Zimmerer, 2011), but they had to adapt to the use of a water hose to channel water from the constructed wells and dugouts for watering of crops. Others adopt mulching of crops, early planting, planting of trees around reservoirs, using vetiva grass on the embankment of the dams and dugouts; regular maintenance of the lateral canals, not farming closer to the basins and river beds to the dams and dugouts. These help reduce siltation. These activities that the beneficiary irrigation farmers undertake do not just co-manage these irrigation facilities as Community Based Irrigation Schemes (Mati, 2023; Akuriba et al., 2020), but also pay for the costs of irrigation services and provide labour for the maintenance. Thus, these beneficiary farmers continue to offer critical support and duty to the governance of the irrigation facilities and services (Katic, 2024) to enhance the sustainability of reservoirs in the Sissala West District. So, until the human activities that trigger erratic rainfall and high temperatures are curtailed, irrigation farming will continue to be a dicey livelihood enterprise.

6 Conclusion and policy implications

The study on the impact of variable climate on smallholder dry season irrigation farming revealed that the capacity of reservoirs to store enough water, ways of the reservoirs’ water distribution methods to irrigation farms and the type of irrigation system affect the irrigation activities in the Sissala West District. Although the small-scale irrigation dams were meant to irrigate about 10 to 20 hectares (i.e., each site) of the vast land area, they irrigate 10 hectares or less on average from each irrigation site, and that is small compared to their potentials. The study indicated that low levels of water in the reservoirs are the most salient elements responsible for the underutilisation of irrigable land.

To sustain the level of water in reservoirs for small-scale irrigation farming in the Sissala West District, the Ghana Irrigation Development Authority (GIDA) should always involve community members in the planning and development of small-scale irrigation dams. Participatory irrigation management has been considered as the driving force in the effective and efficient irrigation management that involves small-scale irrigation farmers in planning, operation and maintenance of the irrigation schemes.

The District Office of MoFA should provide training for smallholder dry-season farmers on best practices of irrigation water management. This will enhance the understanding of how to use irrigation water effectively and efficiently for farmers to manage water in the reservoirs for their irrigation activities.

The Central Government and agriculture-centred Non-Governmental Organisations need to support smallholder dry season irrigation farmers with extension services and conservation technologies, knowledge and skills on better agronomic practices, and environmental conservation.

The Government of Ghana, through the Sissala West District Assembly, should support the respective irrigation communities to rehabilitate their irrigation dams and dugouts by constructing new canals, replacing damaged pipes and desilting or dredging the reservoirs. This will reduce water wastage and improve small-scale irrigation outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Simon Diedong University of Business and Integrated Development Studies (SDD-UBIDS), Ethical review Board, SDD-UBIDS/37/24. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because participants preferred oral consent because they could not read and write.

Author contributions

LS: Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SK: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software. A-RA: Investigation, Software, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Methodology, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aasoglenang, A. T., Kanlisi, K. S., Naab, F. X., Dery, I., Maabasog, R., Maabier, E., et al. (2013). Land access and poverty reduction among women in Chansa in the north western region of Ghana. Int. J. Dev. Sustain., 2: 1580–1596. Available online at: www.isdsnet.com/ijds

Abdelsalam, N. M., Aziz, M. Z., and Agrama, A. A. (2014). Quantitative and financial impacts of Nile River inflow reduction on hydropower and irrigation in Egypt. Energy Procedia 50, 652–661.

Adamson, D., and Loch, A. (2014). Possible negative sustainability impacts from ‘gold- plating’ infrastructure. Agric. Water Manag. 145, 134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2013.09.022

Ahmad, Q., Biemans, H., Moors, E., Shaheen, N., and Masih, I. (2021). The impacts of climate variability on crop yields and irrigation water demand in South Asia. Water 13:50.

Akurugu, A. J. (2007). The role of user organisations in the management of smallholder irrigation schemes: the case of the Binduri water users Association of the Bawku Municipality, Ghana. J. Dev. Stud. 4, 59–74.

Akurugu, M.A., Salifu, M., and Millar, K. K. (2019). Rising to meet the new challenges of Africa’s agricultural development beyond vision 2020: The role of irrigation investments for jobs and wealth creation. Paper presented at the 6th African conference of agricultural economists. Abuja, NigeriaSeptember 23–26, 2019.

Akuriba, M. A., Haagsma, R., Heerink, N., and Dittoh, S. (2020). Assessing governance of irrigation systems: a view from below. World Dev. Perspect. 19:100197. doi: 10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100197

Amede, T. (2014). Technical and institutional attributes constraining the performance of small-scale irrigation in Ethiopia. Water Resour. Rural Dev. 6, 78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.wrr.2014.10.005

Amede, T. (2015). (Eds). Managing rainwater and small reservoirs in sub-Saharan Africa. Water Resources and Rural Development 6. doi: 10.1016/s2212-6082(15)00028-5

Antwi-Agyei, P., and Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. (2021). Evidence of climate change coping and adaptation practices by smallholder farmers in northern Ghana. Sustainability 13. doi: 10.3390/su13031308

Askaraliev, B., Musabaeva, K., Koshmatov, B., Omurzakov, K., and Dzhakshylykova, Z. (2024). Development of modern irrigation systems for improving efficiency, reducing water consumption and increasing yields. Naukovij žurnal «Tehnìka ta energetika» 15, 47–59. doi: 10.31548/machinery/3.2024.47

Bar, R., Rouholahnedjad, E., Rahman, K., Abbaspour, K. C., and Lehmann, A. (2015). Climate change and agricultural water resources: a vulnerability assessment of the Black Sea catchment. Environ Sci Policy 46, 57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2014.04.008

Baldwin, G. L., and Stwalley, R. M., III. (2022). Opportunities for the Scale-Up of Irrigation Systems in Ghana, West Africa. Sustainability, 14:8716. doi: 10.3390/su14148716

Bonye, S., Yenglier, B. F. D., and Yiridomoh, G. (2021). Common-pool community resource use: governance and management of community irrigation schemes in rural Ghana common-pool community resource use: governance and management of community irrigation schemes in rural Ghana. Community Dev. 53, 39–56. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2021.1937668

Dakpalah, S. S., Anornu, G. K., and Ofoso, E. A. (2018). Small scale irrigation development in upper west region, Ghana; challenges, potentials and solutions. Civ. Environ. Res. 10, 85–97. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13061139

Darimani, H. S., Kpoda, N., Suleman, S. M., and Luut, A. (2021). Field performance evaluation of a small-scale drip irrigation system installed in the upper west region of Ghana. Comput. Water Energy Environ. Eng. 10, 82–94. doi: 10.4236/cweee.2021.102006

Denscombe, M. (2021). The good research guide: Research methods for small-scale social research. 7th Edn. London: Open University Press.

Derbile, E. K., Kanlisi, K. S., and Dapilah, F. (2022). Mapping the vulnerability of indigenous fruit trees to environmental change in the fragile savannah ecological zone of northern Ghana. Heliyon 8:e09796. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09796

Dinardo, J. (2008). “Natural experiments and quasi-natural experiments” in The new Palgrave dictionary of economics, London: Palgrave Macmillan. 856–859. doi: 10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2006-1

Flyvbierg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case study research Qual. Inq. 12: 219–245. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2230464

Food and Agriculture Organisation (2013). Trends and impacts of foreign investment in developing country agriculture. Evidence from case studies. Rome.

George, A., and Bennett, A. (2004). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences (BCSIA studies in international security). The MIT Press. 19–20

Ghana Meteorological Agency (2024). Rainfall and temperature data from 2021 to 2023. Wa- Upper West Region. Unpublished.

Ghana Statistical Service (2012). 2010 population and housing census. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

Kabat, P., Schulze, R. E., Hellmuth, M. E., and Veraart, J. A. (Eds.) (2003). Coping with impacts of climate variability and climate change in water management: A scoping paper. DWC-report no. DWCSSO-01 international secretariat of the dialogue on water and climate. Wageningen: International Secretariat of the Dialogue on Water and Climate.

Katic, P. G. (2024). Comparing the impacts of different irrigation systems on the livelihoods of women and youth: evidence from clustered data in Ghana. Water Int. 49, 616–640. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2024.2330272

Kelley, B., Dong, Y., Chilvers, M. I., and Das, N. (2025). Understanding the impact of irrigation scheduling on water use efficiency in corn and soybean production in humid climates: insights from on-farm demonstration. Front. Agron. 7:1496198. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2025.1496198

Ketchum, D., Hoylman, Z. H., Huntington, J., Brinkerhoff, D., and Jencso, K. G. (2023). Irrigation intensification impacts sustainability of streamflow in the western United States. Commun. Earth Environ. 4:479. doi: 10.1038/s43247-023-01152-2

Kpieta, B. A., Owusu-Sekyere, E., and Bonye, S. Z. (2013). Reaping the benefits of small-scale irrigation dams in North-Western Ghana: experiences from three districts in the upper west region. Res. J. Agric. Environ. Manage. 2, 217–228.

Mati, B. (2023). Farmer-led irrigation development in Kenya: characteristics and opportunities. Agric. Water Manag. 277:108105. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2022.108105

Mushtaq, S., Maraseni, T. N., and Reardon-Smith, K. (2013). Climate change and water security: estimating the greenhouse gas costs of achieving water security through investments in modern irrigation technology. Agric. Syst. 117, 78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2012.12.009

Namara, R.E., Horowitz, L., Nyamadi, B., and Barry, B. (2011) Irrigation development in Ghana: past experiences, emerging opportunities, and future directions. Ghana strategy support program (GSSP) working paper 27. Available online at: http://www.ifpri.org/themes/gssp/gssp.htm

Ringler, C. (2017). Investment in irrigation for global food security. IFPRI policy note. Washington DC: IFPRI.

Ringler, C. (2021). From torrents to trickles: irrigation's future in Africa and Asia. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 13, 157–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev-resource-101620-081102

Saleth, R.M., Dinar, A., and Frisbie, A., (2011). Climate change, drought and agriculture: the role of effective institutions and infrastructure. In: Dinar, A., and Mendelsohn, R 2nd, Handbook on agriculture and climate change. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 466–485.

Simonet, D., and Rajendran, P. (2025). A smartphone application for estimating irrigation frequency and runtime for Californian crops based on the water balance approach. Mausam 76, 541–552. doi: 10.54302/mausam.v76i2.6610

Sissala West District Assembly MoFA (2015). Annual progress report. Sissala West District Assembly. Sissala West District, Gwollu, Ghana.

Sissala West District Assembly (2016). Medium term development plan. NationalDevelopment Planning Commission, Accra.

Sissala West District Assembly MoFA (2023). Annual progress report. Sissala West District Assembly. Sissala West District, Gwollu, Ghana.

Sissala West District Assembly MoFA (2024). Annual progress report. Sissala West District Assembly. Sissala West District, Gwollu, Ghana.

Slegers, M. F. W. (2008). If only it would rain: farmers’ perceptions of rainfall and drought in semi-arid Central Tanzania. J. Arid Environ. 72, 2106–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.06.011

Tsegaye, D., Moe, S. R., and Haile, M. (2013a). Livestock browsing, not water limitations, contributes to recruitment failure of Dobera glabra in semiarid Ethiopia. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 62, 540–549. doi: 10.2111/08-219.1

Tsegaye, D., Vedeld, P., and Moe, S. R. (2013b). Pastoralists and livelihoods: a case study from northern Afar, Ethiopia. J. Arid Environ. 91, 138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2013.01.002

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ylikoski, P. (2019). Mechanism-based theorizing and generalization from case studies. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. A. 78, 14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.shpsa.2018.11.009,

Zhang, W., Zhao, X., Gao, X., Liang, W., Li, J., and Zhang, B. (2025). Spatially explicit assessment of water scarcity and potential mitigating solutions in a large water-limited basin: The Yellow River basin in China. Hydrology and Earth Sciences, 29, 507–524. doi: 10.5194/hess-29-507-2025

Zimmerer, K. S. (2011). The landscape technology of spate irrigation amid development changes: assembling the links to resources, livelihoods, and agrobiodiversity-food in the Bolivian Andes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 21, 917–934. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.04.002

Zimmermann, R., Bruntrüp, M., and Kolavalli, S. & Flaherty, K. (2009). Agricultural policies in sub-Saharan Africa: understanding and improving participatory policy processes in CAADP and APRM. Studies, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, ISSN 1860-0468. Available online at: http://www.die-gdi.dc

Keywords: climate variability, effects, small-scale farming, irrigation, Sissala West District

Citation: Susan L, Kanlisi SK and Abdulai A-RA (2025) Unlocking resilience: exploring climate dynamics in small-scale irrigation systems of Sissala West District of north-western Ghana. Front. Clim. 7:1733615. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1733615

Edited by:

Rajiv Kumar Srivastava, Texas A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

Soumitra Saha, University of Burdwan, IndiaMustapha Mohammed Suraj, CSIR-Savanna Agricultural Research Institute, Ghana

Copyright © 2025 Susan, Kanlisi and Abdulai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Libanus Susan, c2xpYmFudXNAdWJpZHMuZWR1Lmdo

Libanus Susan

Libanus Susan Simon Kaba Kanlisi2

Simon Kaba Kanlisi2