- 1Department of Life Science, Health and Health Professions Link Italy, Rome, Italy

- 2Department of Human Sciences, Innovation and Territory, School of Dentistry, Postgraduate of orthodontics, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy

- 3Department of Medical, Oral and Biotechnological Sciences, G. D’Annunzio University of Chieti -Pescara, Chieti, Italy

- 4Private Practice, Parma, Italy

- 5Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari, Italy

- 6Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Sciences, Milan University, Milan, Italy

- 7Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Salento, Lecce, Italy

Aim: The purpose of this study is to understand how the training of a clinician influences his or her therapeutic choices in the orthodontic field.

Materials and methods: An anonymized questionnaire was submitted to 317 Italian dentists to ask them about their training and what orthodontic therapies they perform. The answers were processed by statistical analysis.

Results: 221 of 314 respondents (70.3%) had an orthodontic postgraduate education and 93 subjects did not (29.7%). Out of the whole sample, 242 clinicians use functional therapy (i.e., Frankel, Bionator or Andresen), but while 133 of them, after functional therapy, apply both fixed orthodontic appliances (i.e., Straight wire, Tweed or Rickets) and aligners, 79 use only fixed oral appliances, and 19 dentists use only an aligner. The application of a lingual technique is perfectly independent from having an orthodontic postgraduate education or not.

Conclusion: Differences were found between dentists with an orthodontic postgraduate education and dentists without it. Most dentists in Italy pursued a postgraduate education. In addition, most orthodontists are dedicated exclusively to orthodontics in their office, while dentists who don't have an orthodontic postgraduate education do not practice orthodontics exclusively in their offices. It is possible to conclude that pursuing a specialization in orthodontics determines advantages for both practitioners and patients: it gives orthodontists those extra skills to customize a diagnosis and daily treatments in a more precise and innovative way, using a wider variety of therapeutic options and relying more on teamwork, for complementary solutions. These additional skills usually increase a treatment's success and decrease complications, which, first and foremost, benefit the patients.

1 Introduction

Orthodontics is the branch of dentistry that deals with promoting correct craniofacial growth, the harmonious development of the jaws, and correct occlusion. It aims to eliminate any interference with these physiological processes or to correct dental misalignments, malocclusions, or skeletal discrepancies that may arise during growth or due to genetic and environmental factors (1–9). Orthodontic interventions play a fundamental role in ensuring the proper function and aesthetics of the stomatognathic system. The complexity of modern orthodontic care, which combines biological understanding, biomechanics, and digital technology, demands a high level of professional competence (10–32). Yet, despite its evolution, orthodontics is a relatively young specialty—barely over 100 years old (33–58) Advances such as 3D imaging, intraoral scanning, and computer-aided design (CAD) have dramatically transformed diagnostic and therapeutic workflows, enhancing precision and patient engagement (59–67).

Efforts to harmonize orthodontic education across Europe began with F. P. van der Linden's Erasmus project in 1992, recognizing the need for a common academic standard (68–78). Today, clinicians can pursue various pathways for advanced training, including residencies, university master's degrees, and continuing education courses. These educational opportunities are vital to ensure that practitioners stay up to date with emerging evidence, technologies, and treatment philosophies (79, 80).

In Italy, after the six-year degree in dentistry, a three-year graduate school of orthodontics is available to those who wish to specialize (81). This residency program provides structured, evidence-based training that includes theoretical instruction, clinical practice, and research. It enables young dentists to acquire the diagnostic skills and therapeutic competence needed to treat a wide variety of malocclusions. The program also emphasizes interdisciplinary collaboration, particularly with surgeons and prosthodontists, for complex cases (82–84).

In the absence of standardized training, dentists who follow non-residency routes may exhibit variable preparation and treatment outcomes, with potential repercussions for quality and patient safety (85).

Currently, there is limited literature addressing the specific role and importance of orthodontic residency in Italy and how such advanced training influences the clinical decisions of practitioners (86–94). Understanding whether formal postgraduate education significantly impacts the quality of care and treatment outcomes is essential. The purpose of this study is to explore this topic and help clarify how postgraduate orthodontic training shapes clinical practice and, ultimately, patient management (95–97).

2 Material and methods

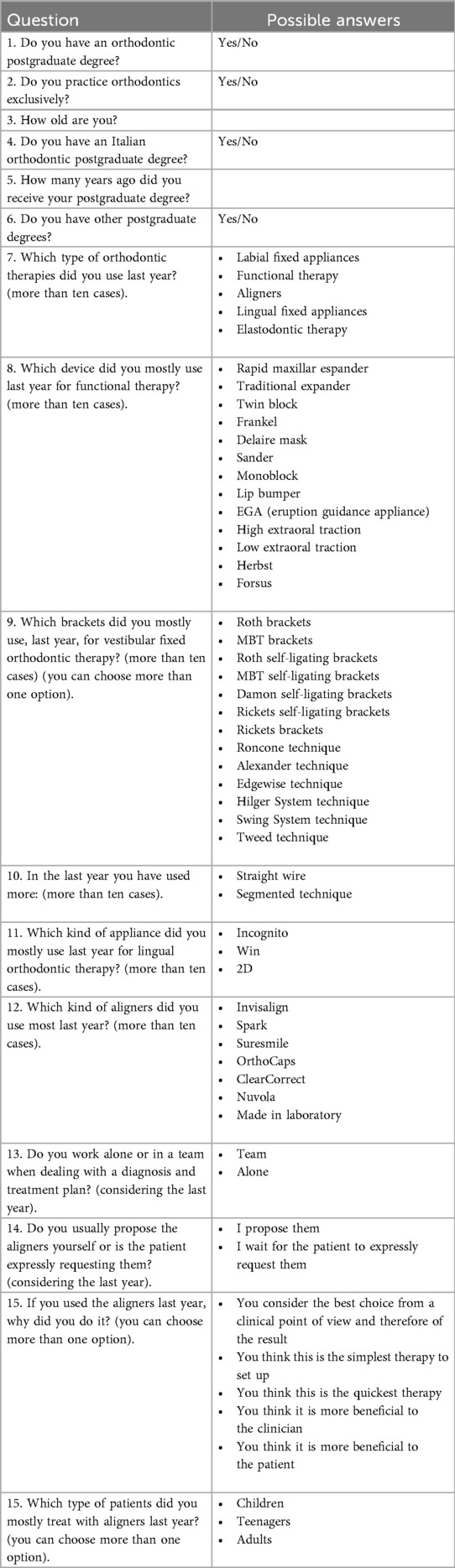

A questionnaire was submitted to 500 Italian Dental offices, in which there was a possibility to receive an orthodontic treatment. Only 317 answers could be included in this study. The dentists were asked to complete an anonymous questionnaire (Table 1) electronically distributed, in Italian, between July and August 2022.

2.1 Dissemination

The Google Form link was distributed via email to dental offices across Italy and through professional contacts and mailing lists of dental associations. No reminders were sent.

2.2 Eligibility and data cleaning

Inclusion criteria were: licensed Italian dentist who practices orthodontics and complete questionnaire. Pre-specified internal validation and cross-item consistency checks were applied (e.g., implausible age vs. training timeline; contradictory answers). Eight questionnaires were excluded (5 implausible age declarations; 3 inconsistent answers), yielding 309 valid questionnaires for analysis.

2.3 Statistics

Categorical data are reported as frequencies/percentages and compared with Chi-square tests; effect size is Cramer's V. Numerical variables were compared with t-tests. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.4 Ethics and data protection

All respondents provided informed consent. Data were collected anonymously, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

3 Results

3.1 Sample and exclusions

After internal validation and consistency checks (see Methods), 309 questionnaires were retained for analysis (8 exclusions).

3.2 Specialization status

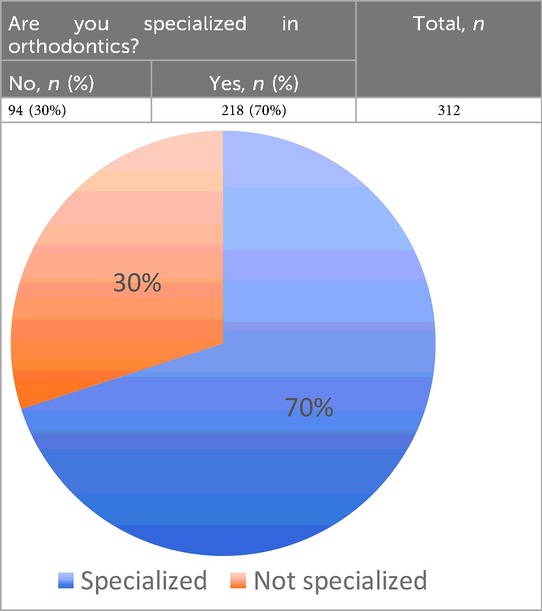

70% (218/312) were specialized in orthodontics and 30% (94/312) were not (Table 2).

3.3 Technique by specialization

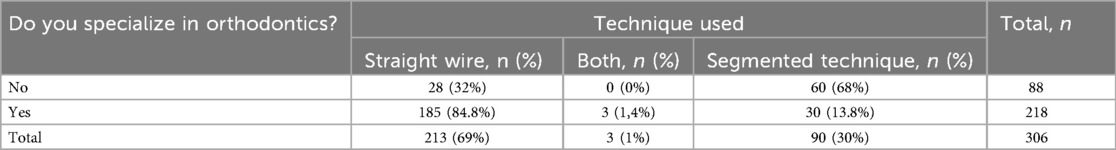

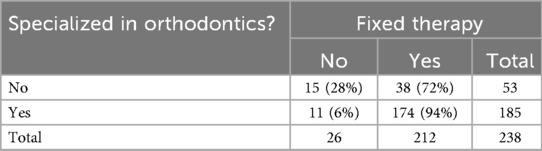

Specialization was associated with technique choice (χ2 = 89.68, df = 2, p < 0.0001; Cramer's V = 0.54): specialists predominantly used straight wire, non-specialists mainly segmented tecnique (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of orthodontic techniques used by dentists with and without orthodontic specialization.

3.4 Time since specialization

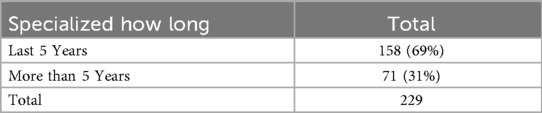

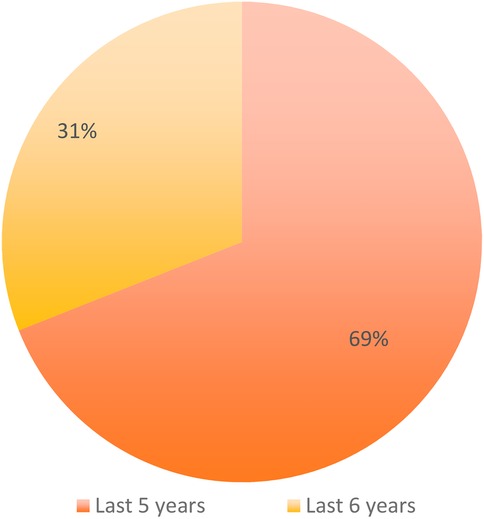

Among specialists, 69% (158/229) obtained specialization ≤5 years ago and 31% (71/229) > 5 years (Table 4; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of respondents according to the time since obtaining orthodontic specialization (last 5 years vs more than 5 years).

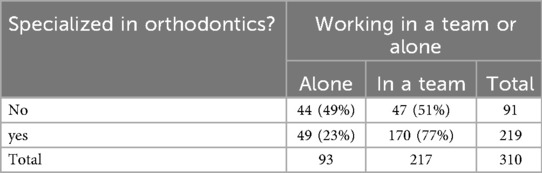

3.5 Country of specialization

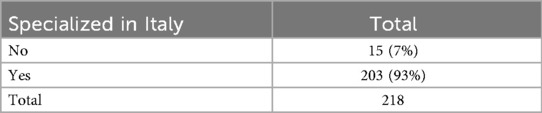

93% (203/218) trained in Italy and 7% (15/218) abroad (Table 5; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of respondents according to the country where orthodontic specialization was obtained (Italy vs abroad).

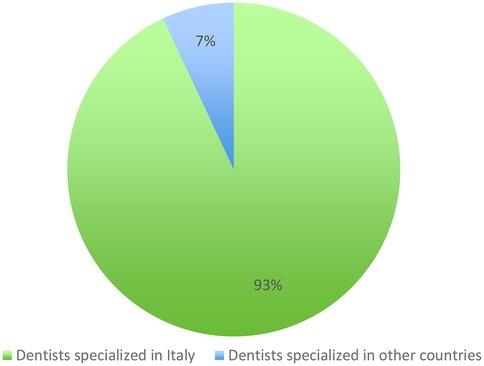

3.6 Lingual technique

Distribution of 2D, WIN, other/unknown did not differ by specialization (p = 0.96; Cramer's V≈0.03) (Table 6).

Table 6. Distribution of lingual orthodontic techniques (2D, WIN, other/unknown) used by specialists and non-specialists.

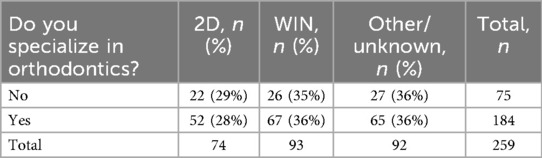

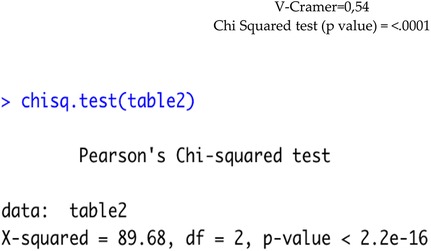

3.7 Teamwork

Specialists were more likely to work in a team (77% vs. 23%); non-specialists were ∼even (51% vs. 49%); χ2 = 19.71, df = 1, p < 0.0001; Cramer's V≈0.26 (Table 7).

Table 7. Comparison between specialists and non-specialists in orthodontics regarding their preference for working alone or in a team.

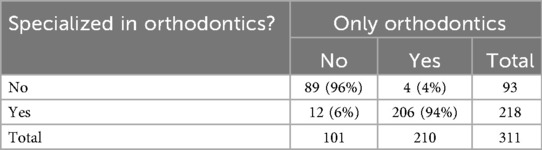

3.8 Exclusive orthodontic practice

94% (206/218) of specialists reported only orthodontics, vs. 4% (4/93) of non-specialists (Table 8).

Table 8. Proportion of specialists and non-specialists in orthodontics who practice exclusively orthodontics.

3.9 Additional specializations

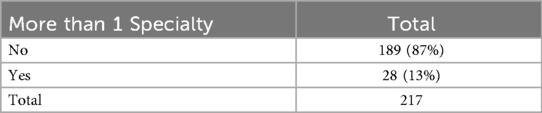

13% (28/217) of specialists reported an additional specialty (Table 9).

3.10 Post-functional therapy choices

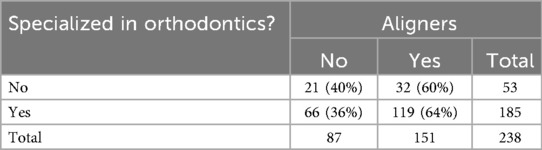

Among clinicians using functional therapy, specialists more often proceeded with fixed appliances (94% vs. 72%; Table 10) and used aligners slightly more often (64% vs. 60%; Table 11).

Table 10. Use of fixed orthodontic therapy after functional therapy among specialists and non-specialists.

3.11 Age

Mean age did not differ between predominant aligner users (44.4 years) and fixed-appliance users (45.15 years); p = 0.46.

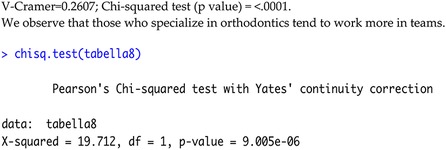

Out of the whole sample, 242 clinicians use functional therapy (i.e., Frankel, Bionator, or Andresen), but while 133 of them, after functional therapy, apply both fixed orthodontic appliances (i.e., Straight wire, Tweed or Ricketts) and aligners, 79 use only fixed oral appliances, and 19 dentists use only an aligner. The kind of lingual technique used is independent from being a dentist with an orthodontic postgraduate degree or not. The data obtained suggests that specialists do not prefer a specific technique [V Cramer: 0.03; Chi Square Test (p-value) = 0.96]. The power of the Chi Square Test used is 95.1% for lingual techniques.

From the contingency table it is possible to note that, for those who don't have a specialty in orthodontics, there is an equal distribution between teamwork and work alone, while for the specialized ones there is a clear preference for teamwork. The Chi-Square Test leads us to accept the hypothesis of dependence between being specialized and preferring, or not, working with a team. The value of V Cramer equal to 0.258, however, indicates that there is no net dependence, in fact, as described above, those with specialization tend to work in a team while those without specialization do not have this attitude.

1. Among the respondents, 70% (218/312) were specialized in orthodontics, while 30% (94/312) were not (Table 2).

2. Which orthodontic techniques are the most used by those specialized and those not specialized in orthodontics? A significant association was found between specialization status and the orthodontic technique used (χ2 = 89.68, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Specialists predominantly used the straight wire technique, whereas non-specialists mainly adopted the segmented technique (Table 3).

A Chi-squared test showed a significant association between specialization status and the orthodontic technique used (χ2 = 89.68, df = 2, p < 0.0001). We can observe that those who are specialized tend to use the straight wire technique more than those who are not specialized.

3. How many dentists have obtained a degree in orthodontics or other specialization in the last 5 years? (Table 4, Figure 1)

4. Who uses aligners the most and who uses traditional fixed orthodontics, based on age:

The average age of those who use aligners is 44.4 years, the average age of those who use fixed therapy is 45.15 years. Age difference is not significant (t-test for comparison of means, p-value = 0.46).

5. Do the dentists specializing in orthodontics prefer to use segmented technique or straight wire?

188 Dentists who specialized in orthodontics do prefer to use the straight wire orthodontic technique, while 33 prefer the use of segmented technique (3 of these prefer both techniques).

6. Did most dentists specializing in orthodontics choose their residency/degree in Italy or outside the country? (Table 5, Figure 2)

7. Which lingual technique is preferred by dentists with a degree in orthodontics? (Table 6)

The p-value is equal to 0.96, therefore no differences in the lingual technique are observed between those with and those with no specialization.

8. Comparison between the dentists with specialization and the ones without it, regarding the choice of working in a team or not (Table 7):

A Chi-squared test showed a significant association between specialization status and preference for working in a team (χ2 = 19.71, df = 1, p < 0.0001; Table 7). Specialists were more likely to work in teams compared to non-specialists.

9. Evaluate if those specialized in orthodontics practice only orthodontics (Table 8):

As we would expect, those who specialize in orthodontics are more inclined to work only in this field.

10. Evaluate if those who are specialized in orthodontics have or are pursuing a second specialization (Table 9):

11. Evaluate whether orthodontic specialists use functional orthodontics first and then aligners and/or fixed devices (Table 10):

*In the following tables, only the responses of those who have used functional therapy have been considered.

We observe that those who are specialized use fixed therapy much more than those who are not specialized (Table 11).

4 Discussion

Given the breadth of training options, orthodontists should emphasise prevention (98, 99). When treatment is required, a wide array of validated appliances can manage varied presentations (100–108).

Main findings. In this national survey, orthodontic specialization was strongly associated with technique selection and work organization: specialists predominantly used straight-wire mechanics and reported team-based care and exclusive orthodontic practice, whereas non-specialists more often adopted segmented tecnique and worked across broader scopes (109–111). No preference differences emerged for lingual systems.

4.1 Clinical implications of postgraduate education

Postgraduate training appears to shape clinicians' diagnostic repertoire, biomechanical planning, and practice organization. The higher use of straight-wire mechanics among specialists likely reflects greater confidence with comprehensive tooth movement and anchorage control acquired during residency, whereas the preference for segmented tecnique among non-specialists may represent a strategy to limit unwanted effects in complex movements when biomechanical mastery is more limited (112, 113). These patterns align with literature showing that outcomes and efficiency vary by appliance and operator proficiency, and that clear biomechanical planning remains decisive regardless of technique (114–119).

Specialization was also associated with team-based care. Interdisciplinary workflows—orthodontist with surgeons, pediatric dentists, myofunctional/speech therapists, etc.—are linked to safer, higher-quality care and more predictable management of complex cases (120–132). Finally, where aligners are used, evidence suggests advantages in oral hygiene and treatment comfort but mixed findings on movement accuracy in demanding biomechanics; successful aligner therapy depends on solid diagnostic and biomechanical competence—competencies typically emphasized in structured programs. Overall, our data supports the view that formal postgraduate education may translate into broader therapeutic options, greater integration with teams, and potentially more consistent treatment execution in daily practice (133).

4.2 Limitations of a self-reported cross-sectional survey

This study has important limitations. First, self-report introduces recall and social-desirability bias; responses were not verified against charts or objective outcomes. Second, although we applied internal validation and excluded inconsistent records, some misclassification is still possible and denominators vary across items. Third, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference: specialization and technique choices may both be influenced by unmeasured factors (case mix, practice model, local market). Fourth, the sampling frame (email dissemination and professional networks) may entail selection bias and limits generalizability beyond Italy. Fifth, the questionnaire, while face-valid, lacked external psychometric validation (e.g., reliability indices). Finally, we did not collect clinical outcomes (e.g., ABO-OGS, treatment time, relapse, PROMs), so we cannot link training pathways to effectiveness or safety (134–136).

4.3 Suggestions for future research

Prospective and mixed-methods designs are needed to move beyond self-report and strengthen causal interpretation:

• Prospective cohorts/registries linking clinician training to objective outcomes (ABO-OGS, treatment duration, retreatment/relapse, root resorption, periodontal indices), with risk-adjustment for case complexity.

• Qualitative work (interviews/focus groups) to explore why some dentists do not pursue specialization and what drives technique selection (perceived risks/benefits, workload, economics, access to training).

• Comparative education studies across programs/countries (curricula, competencies, mentorship, clinical exposure) aligned with current European/WFO guidance.

• Instrument development: validation of a brief, reliable questionnaire (content/construct validity, test-retest) and clearer operational definitions for techniques.

• Health-services analyses: impact of team-based models on outcomes and costs; modeling of practice scope (exclusive vs. mixed) on adoption of innovations (e.g., aligners, TADs) (137–144).

Take-home messages. (i) Postgraduate education correlates with broader technique use and teamwork—organizational features linked to quality and safety (145–157). (ii) Self-reported, cross-sectional data cannot establish causality or outcomes. (iii) Future prospective and qualitative studies should test whether training pathways improve patient-level results and clarify barriers to specialization (158–165).

General dentists without orthodontic specialization tend to favour segmented technique for control of unwanted movements and may update techniques less often given their broader remit (166–173).

Our study has some limitations but also suggests opportunities for future research. With the exception of two potentially ambiguous items, the study did not elicit respondents’ reasons for not undertaking orthodontic specialization (174–180). Financial burden, universities not close to home, working in a rural area where the practitioner needs to have multiple but basic skills, or preference for general dental work may be some of the reasons. Conversely, behind the decision to get specialized could be the prospect of future higher earnings in orthodontics rather than in dentistry. Likewise, it's possible that financial burden on the patient and context in which an orthodontist works could impact the decision to use one orthodontic treatment over another (181–183).

5 Conclusions

Observing the data that emerged from this questionnaire submitted to 317 dentists/orthodontists, it is possible to conclude that pursuing a specialization in orthodontics brings advantages for both practitioners and patients: it gives orthodontists those extra skills to customize diagnosis and daily treatments in a more precise and innovative way, using a wider variety of therapeutic options and relying more on teamwork for complementary solutions. These additional skills usually increase treatment's success and decrease complications which, first and foremost, benefit the patients. A more specific diagnosis and a customized plan of care may reduce the time of treatment, avoid relapses, increase long term stability of the results and decrease the economic burden for the patient.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Decla-ration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Policlinico of Bari (Prot. Number: 00152571, 15 February 2023 JAOUCPG23ICOMETIP. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SaS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. StS: Resources, Writing – original draft. MP: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. EC: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LF: Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft. FI: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AMI: Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AP: Software, Writing – review & editing. GD: Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft. ADI: Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CAD, computer-aided design; EGA, Eruption Guidance Appliance; FFP2/FFP3, Filtering Face Piece type 2/type 3; MBT, McLaughlin–Bennett–Trevisi; TMJ, Temporomandibular Joint.

References

1. Peck S. The contributions of Edward H. Angle to dental public health. Community Dent Health. (2009) 26:130–1. doi: 10.1922/CDH_2570Peck02

2. Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Abenavoli FM, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AD, Inchingolo AM, et al. Comparison between traditional surgery, CO2 and Nd:Yag Laser treatment for generalized gingival hyperplasia in sturge-weber syndrome: a retrospective study. J Investig Clin Dent. (2010) 1:85–9. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1626.2010.00020.x

3. Inchingolo AD, Patano A, Coloccia G, Ceci S, Inchingolo AM, Marinelli G, et al. Treatment of class III malocclusion and anterior crossbite with aligners: a case report. Medicina (Kaunas. (2022) 58:603. doi: 10.3390/medicina58050603

4. Martelli M, Russomanno WL, Vecchio SD, Gargari M, Bollero P, Ottria L, et al. Myofunctional therapy and atypical swallowing multidisciplinary approach. Oral Implantol J Innov Adv Techniq Oral Health. (2024) 16:153–5. doi: 10.11138/oi163153-155

5. Botzer E, Quinzi V, Salvati SE, Coceani Paskay L, Saccomanno S. Myofunctional therapy part 3: tongue function and breastfeeding as precursor of oronasal functions. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2021) 22:248–50. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2021.22.03.13

6. Adamo D, Spagnuolo G. Burning mouth syndrome: an overview and future perspectives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 20:682. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20010682

7. Inchingolo AD, Patano A, Coloccia G, Ceci S, Inchingolo AM, Marinelli G, et al. The efficacy of a new AMCOP® elastodontic protocol for orthodontic interceptive treatment: a case series and literature overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:988. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020988

8. Inchingolo AM, Malcangi G, Costa S, Fatone MC, Avantario P, Campanelli M, et al. Tooth complications after orthodontic miniscrews insertion. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:1562. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021562

9. Inchingolo AM, Patano A, Di Pede C, Inchingolo AD, Palmieri G, de Ruvo E, et al. Autologous tooth graft: innovative biomaterial for bone regeneration. Tooth transformer® and the role of Microbiota in regenerative dentistry. A systematic review. J Funct Biomater. (2023) 14:132. doi: 10.3390/jfb14030132

10. Grippaudo MM, Quinzi V, Manai A, Paolantonio EG, Valente F, La Torre G, et al. Orthodontic treatment need and timing: assessment of evolutive malocclusion conditions and associated risk factors. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2020) 21:203–8. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2020.21.03.09

11. Fleming PS. Timing orthodontic treatment: early or late? Aust Dent J. (2017) 62(Suppl 1):11–9. doi: 10.1111/adj.12474

12. Robertson L, Kaur H, Fagundes NCF, Romanyk D, Major P, Flores Mir C. Effectiveness of clear aligner therapy for orthodontic treatment: a systematic review. Orthod Craniofac Res. (2020) 23:133–42. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12353

13. Sangle R, Parab M, Gujare A, Dhatrak P, Deshmukh S. Effective techniques and emerging alternatives in orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic review. Med Novel Technol Devices. (2023) 20:100274. doi: 10.1016/j.medntd.2023.100274

14. Djeu G, Shelton C, Maganzini A. Outcome assessment of invisalign and traditional orthodontic treatment compared with the American board of orthodontics objective grading system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (2005) 128:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.06.002

15. Christou T, Abarca R, Christou V, Kau CH. Smile outcome comparison of invisalign and traditional fixed-appliance treatment: a case-control study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (2020) 157:357–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.03.030

16. Zhou C, Duan P, He H, Song J, Hu M, Liu Y, et al. Expert consensus on pediatric orthodontic therapies of malocclusions in children. Int J Oral Sci. (2024) 16:32. doi: 10.1038/s41368-024-00299-8

17. Laforgia A, Inchingolo AM, Inchingolo F, Sardano R, Trilli I, Di Noia A, et al. Paediatric dental trauma: insights from epidemiological studies and management recommendations. BMC Oral Health. (2025) 25:6. doi: 10.1186/s12903-024-05222-5

18. Lin M, Xie C, Yang H, Wu C, Ren A. Prevalence of malocclusion in Chinese schoolchildren from 1991 to 2018: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent. (2020) 30:144–55. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12591

19. Biondi M, Picardi A. Temporomandibular joint pain-dysfunction syndrome and bruxism: etiopathogenesis and treatment from a psychosomatic integrative viewpoint. Psychother Psychosom. (1993) 59:84–98. doi: 10.1159/000288651

20. Ieremia L, Popoviciu L, Balaş M, Dodu S, Gabor D. [Nocturnal bruxism. Contributions to the detection and assessment of involvement in the craniomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome]. Rev Med Interna Neurol Psihiatr Neurochir Dermatovenerol Neurol Psihiatr Neurochir. (1989) 34:307–16.2485932

21. Cannistraci AJ, Friedrich JA. A multidimensional approach to bruxism and TMD. N Y State Dent J. (1987) 53:31–4.3477733

22. Gillahan RD, Melson M, Sakumura J. The psychological aspects of occlusion. J Mo Dent Assoc (1980). (1981) 61:28–31.6941030

23. Majorana A, Bardellini E, Amadori F, Conti G, Polimeni A. Timetable for oral prevention in childhood–developing dentition and oral habits: a current opinion. Prog Orthod. (2015) 16:39. doi: 10.1186/s40510-015-0107-8

24. Surana P, Madhavi Dinavahi S, Sajjanar A, Gupta NR, Sharma P, Sabharwal RJ. Oral habits among preschool Indian children at durg-bhilai city. Bioinformation. (2024) 20:528–31. doi: 10.6026/973206300200528

25. Larsson E. Sucking, chewing, and feeding habits and the development of crossbite: a longitudinal study of girls from birth to 3 years of age. Angle Orthod. (2001) 71:116–9. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071%3C0116:SCAFHA%3E2.0.CO;2

26. Duncan K, McNamara C, Ireland AJ, Sandy JR. Sucking habits in childhood and the effects on the primary dentition: findings of the avon longitudinal study of pregnancy and childhood. Int J Paediatr Dent. (2008) 18:178–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00905.x

27. Josell SD. Habits affecting dental and maxillofacial growth and development. Dent Clin North Am. (1995) 39:851–60. doi: 10.1016/S0011-8532(22)00626-7

28. Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Abenavoli FM, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AD, Villabruna B, et al. Severe anisocoria after oral surgery under general anesthesia. Int J Med Sci. (2010) 7:314–8. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.314

29. Inchingolo F, Inchingolo AD, Latini G, Trilli I, Ferrante L, Nardelli P, et al. The role of curcumin in oral health and diseases: a systematic review. Antioxidants. (2024) 13:660. doi: 10.3390/antiox13060660

30. Mostafiz W. Fundamentals of interceptive orthodontics: optimizing dentofacial growth and development. Compend Contin Educ Dent. (2019) 40:149–54. quiz 155.30829496

31. Chen XX, Xia B, Ge LH, Yuan JW. [Effects of breast-feeding duration, bottle-feeding duration and oral habits on the occlusal characteristics of primary dentition]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. (2016) 48:1060–6.27987514

32. Bishara SE, Warren JJ, Broffitt B, Levy SM. Changes in the prevalence of nonnutritive sucking patterns in the first 8 years of life. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (2006) 130:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.11.033

33. Gelb M, Montrose J, Paglia L, Saccomanno S, Quinzi V, Marzo G. Myofunctional therapy part 2: prevention of dentofacial disorders. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2021) 22:163–7. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2021.22.02.15

34. Paglia L. Interceptive orthodontics: awareness and prevention is the first cure. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2023) 24:5. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2023.24.01.01

35. Minervini G, Marrapodi MM, Cicciù M. Online bruxism-related information: can people understand what they read? A cross-sectional study. J Oral Rehabil. (2023) 50:1211–6. doi: 10.1111/joor.13519

36. Minervini G, Franco R, Crimi S, Di Blasio M, D’Amico C, Ronsivalle V, et al. Pharmacological therapy in the management of temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. (2024) 24:78. doi: 10.1186/s12903-023-03524-8

37. Ciavarella D, Lo Russo L, Mastrovincenzo M, Padalino S, Montaruli G, Giannatempo G, et al. Cephalometric evaluation of tongue position and airway remodelling in children treated with swallowing occlusal contact intercept appliance (S.O.C.I.A.). Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2014) 78:1857–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.08.008

38. Ciavarella D, Guiglia R, Campisi G, Di Cosola M, Di Liberto C, Sabatucci A, et al. Update on gingival overgrowth by cyclosporine A in renal transplants. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. (2007) 12:E19–25.17195822

39. Cazzolla AP, Lovero R, Lo Muzio L, Testa NF, Schirinzi A, Palmieri G, et al. Taste and smell disorders in COVID-19 patients: role of interleukin-6. ACS Chem Neurosci. (2020) 11:2774–81. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00447

40. Memè L, Gallusi G, Strappa E, Bambini F, Sampalmieri F. Conscious inhalation sedation with nitrous oxide and oxygen in children: a retrospective study. Appl Sci. (2022) 12:11852. doi: 10.3390/app122211852

41. Memè L, Sartini D, Pozzi V, Emanuelli M, Strappa EM, Bittarello P, et al. Epithelial biological response to machined Titanium vs. PVD zirconium-coated Titanium: an in vitro study. Materials (Basel). (2022) 15:7250. doi: 10.3390/ma15207250

42. Farronato G, Giannini L, Riva R, Galbiati G, Maspero C. Correlations between malocclusions and dyslalias. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2012) 13:13–8.22455522

43. Farronato M, Farronato D, Inchingolo F, Grassi L, Lanteri V, Maspero C. Evaluation of dental surface after De-bonding orthodontic bracket bonded with a novel fluorescent composite: in vitro comparative study. Appl Sci. (2021) 11:6354. doi: 10.3390/app11146354

44. Schneider-Moser UEM, Moser L. Very early orthodontic treatment: when, why and how? Dental Press J Orthod. (2022) 27:e22spe2. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709.27.2.e22spe2

45. Artese F. A broader Look at interceptive orthodontics: what can we offer? Dental Press J Orthod. (2019) 24:7–8. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709.24.5.007-008.edt

46. Sunnak R, Johal A, Fleming PS. Is orthodontics prior to 11 years of age evidence-based? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. (2015) 43:477–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.02.003

47. Almasoud NN. Extraction of primary canines for interceptive orthodontic treatment of palatally displaced permanent canines: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. (2017) 87:878–85. doi: 10.2319/021417-105.1

48. Dutra SR, Pretti H, Martins MT, Bendo CB, Vale MP. Impact of malocclusion on the quality of life of children aged 8 to 10 years. Dental Press J Orthod. (2018) 23:46–53. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709.23.2.046-053.oar

49. Inchingolo AM, Inchingolo AD, Carpentiere V, Del Vecchio G, Ferrante L, Di Noia A, et al. Predictability of dental distalization with clear aligners: a systematic review. Bioengineering (Basel). (2023) 10:1390. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering10121390

50. Inchingolo AD, Inchingolo AM, Campanelli M, Carpentiere V, de Ruvo E, Ferrante L, et al. Orthodontic treatment in patients with atypical swallowing and malocclusion: a systematic review. (2024) 48(5):14–26. doi: 10.22514/jocpd.2024.100

51. Abbing A, Koretsi V, Eliades T, Papageorgiou SN. Duration of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances in adolescents and adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog Orthod. (2020) 21:37. doi: 10.1186/s40510-020-00334-4

52. Papageorgiou SN, Koletsi D, Iliadi A, Peltomaki T, Eliades T. Treatment outcome with orthodontic aligners and fixed appliances: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Eur J Orthod. (2020) 42:331–43. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjz094

53. Jambi S, Thiruvenkatachari B, O’Brien KD, Walsh T. Orthodontic treatment for distalising upper first molars in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) 2013:CD008375. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008375.pub2

54. Borda AF, Garfinkle JS, Covell DA, Wang M, Doyle L, Sedgley CM. Outcome assessment of orthodontic clear aligner vs fixed appliance treatment in a teenage population with mild malocclusions. Angle Orthod. (2020) 90:485–90. doi: 10.2319/122919-844.1

55. Zhang M, Liu X, Zhang R, Chen X, Song Z, Ma Y, et al. Biomechanical effects of functional clear aligners on the stomatognathic system in teens with class II malocclusion: a new model through finite element analysis. BMC Oral Health. (2024) 24:1313. doi: 10.1186/s12903-024-05114-8

56. Rehak JR. Corrective orthodontics. Dental Clinics. (1969) 13:437–50. doi: 10.1016/S0011-8532(22)02904-4

57. Flores-Mir C. Limited evidence on treatments for distalising upper first molars in children and adolescents. Evid Based Dent. (2014) 15:23–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400988

58. Alfallaj H. Pre-Prosthetic orthodontics. Saudi Dent J. (2020) 32:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2019.08.004

59. Jamilian A, Darnahal A, Perillo L, Jamilian A, Darnahal A, Perillo L. Orthodontic preparation for orthognathic surgery. In: Motamedi MHK, editor. A Textbook of Advanced Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Vol. 2. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech (2015). p. 105–17.

60. de Ribeiro TTC, Miranda F. Orthodontic pre-surgical planning for orthognathic surgery in patients with cleft lip and palate: key considerations. Semin Orthod. (2025). doi: 10.1053/j.sodo.2025.05.001

61. Larson BE. Orthodontic preparation for orthognathic surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. (2014) 26:441–58. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.08.002

62. Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AM, Tarullo A, Inchingolo AD, et al. Combined occlusal and pharmacological therapy in the treatment of temporo-mandibular disorders. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2011) 15:1296–300.22195362

63. Inchingolo F, Inchingolo AM, Inchingolo AD, Fatone MC, Ferrante L, Avantario P, et al. Bidirectional association between periodontitis and thyroid disease: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2024) 21:860. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21070860

64. Inchingolo F, Inchingolo AM, Malcangi G, De Leonardis N, Sardano R, Pezzolla C, et al. The benefits of probiotics on oral health: systematic review of the literature. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). (2023) 16:1313. doi: 10.3390/ph16091313

65. Klein KP, Kaban LB, Masoud MI. Orthognathic surgery and orthodontics: inadequate planning leading to complications or unfavorable results. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. (2020) 32:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2019.08.008

66. Ghafari JG. Centennial inventory: the changing face of orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (2015) 148:732–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.08.011

67. Spielman AI. The birth of the most important 18th century dental text: pierre fauchard’s Le chirurgien dentiste. J Dent Res. (2007) 86:922–6. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601004

68. Adamo D, Calabria E, Canfora F, Coppola N, Pecoraro G, D’Aniello L, et al. Burning mouth syndrome: analysis of diagnostic delay in 500 patients. Oral Dis. (2024) 30:1543–54. doi: 10.1111/odi.14553

69. Adamo D, Calabria E, Coppola N, Pecoraro G, Mignogna MD. Vortioxetine as a new frontier in the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain: a review and update. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. (2021) 11:20451253211034320. doi: 10.1177/20451253211034320

70. Adamo D, Canfora F, Calabria E, Coppola N, Leuci S, Pecoraro G, et al. White matter hyperintensities in burning mouth syndrome assessed according to the age-related white matter changes scale. Front Aging Neurosci. (2022) 14:923720. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.923720

71. Adamo D, Gasparro R, Marenzi G, Mascolo M, Cervasio M, Cerciello G, et al. Amyloidoma of the tongue: case report, surgical management, and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2020) 78:1572–82. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.04.022

72. Bianchi A, Betti E, Badiali G, Ricotta F, Marchetti C, Tarsitano A. 3D Computed tomographic evaluation of the upper airway space of patients undergoing mandibular distraction osteogenesis for micrognathia. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. (2015) 35:350–4. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-546

73. Boyd K, Saccomanno S, Lewis CJ, Coceani Paskay L, Quinzi V, Marzo G. Myofunctional therapy. Part 1: culture, industrialisation and the shrinking human face. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2021) 22:80–1. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2021.22.01.15

74. Calabria E, Adamo D, Leuci S, Pecoraro G, Coppola N, Aria M, et al. The health-related quality of life and psychological profile in patients with oropharyngeal pemphigus Vulgaris in complete clinical remission: a case-control study. J Oral Pathol Med. (2021) 50:510–9. doi: 10.1111/jop.13150

75. Galluccio G. Is the use of clear aligners a real critical change in oral health prevention and treatment? Clin Ter. (2021) 172:113–5. doi: 10.7417/CT.2021.2295

76. Fortuna G, Ruoppo E, Pollio A, Aria M, Adamo D, Leuci S, et al. Multiple myeloma vs. Breast cancer patients with bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a comparative analysis of response to treatment and predictors of outcome. J Oral Pathol Med. (2012) 41:222–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01095.x

77. Cascone M, Celentano A, Adamo D, Leuci S, Ruoppo E, Mignogna MD. Oral lichen Planus in childhood: a case series. Int J Dermatol. (2017) 56:641–52. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13571

78. Moss JP. Orthodontics in Europe 1992. Eur J Orthod. (1993) (15):393–401. doi: 10.1093/ejo/15.5.393

79. Huggare J, Derringer KA, Eliades T, Filleul MP, Kiliaridis S, Kuijpers-Jagtman A, et al. The erasmus programme for postgraduate education in orthodontics in Europe: an update of the guidelines. Eur J Orthod. (2014) 36:340–9. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjt059

80. Orthodontic Specialists Education in Europe: Past, Present and Future. Available online: Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7849126_Orthodontic_specialists_education_in_Europe_past_present_and_future (Accessed on July 8, 2025).

81. Best Dental Schools in Italy [2025 Rankings] Available online: Available online at: https://edurank.org/medicine/dentistry/it/ (Accessed on July 8, 2025).

82. de Alves ACM, Janson G, Mcnamara JA, Lauris JRP, Garib DG. Maxillary expander with differential opening vs hyrax expander: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (2020) 157:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.07.010

83. Angelieri F, Cevidanes LHS, Franchi L, Gonçalves JR, Benavides E, McNamara JA. Midpalatal suture maturation: classification method for individual assessment before rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (2013) 144:759–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.04.022

84. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

86. Inchingolo AM, Inchingolo AD, Latini G, Garofoli G, Sardano R, De Leonardis N, et al. Caries prevention and treatment in early childhood: comparing strategies. A systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2023) 27:11082–92. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202311_34477

87. Ghafari JG, Macari AT, Zeno KG, Haddad RV. Potential and limitations of orthodontic biomechanics: recognizing the gaps between knowledge and practice. J World Fed Orthod. (2020) 9:S31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejwf.2020.08.008

88. Feng Y, Kong W-D, Cen W-J, Zhou X-Z, Zhang W, Li Q-T, et al. Finite element analysis of the effect of power arm locations on tooth movement in extraction space closure with miniscrew anchorage in customized lingual orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (2019) 156:210–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.08.025

89. Papageorgiou SN, Keilig L, Hasan I, Jäger A, Bourauel C. Effect of material variation on the biomechanical behaviour of orthodontic fixed appliances: a finite element analysis. Eur J Orthod. (2016) 38:300–7. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjv050

90. Almuzian M, Alharbi F, McIntyre G. Extra-Oral appliances in orthodontic treatment. Dent Update. (2016) 43:74–6. 79–82. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.1.74

91. Diedrich P. [Different orthodontic anchorage systems. A critical examination]. Fortschr Kieferorthop. (1993) 54:156–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02171574

92. Inchingolo AM, Malcangi G, Inchingolo AD, Mancini A, Palmieri G, Di Pede C, et al. Potential of graphene-functionalized titanium surfaces for dental implantology: systematic review. Coatings. (2023) 13:725. doi: 10.3390/coatings13040725

93. Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Abenavoli FM, Inchingolo AD, Inchingolo AM, Dipalma G. Fish-Hook injuries: a risk for fishermen. Head Face Med. (2010) 6:28. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-6-28

94. Inchingolo AD, Patano A, Coloccia G, Ceci S, Inchingolo AM, Marinelli G, et al. Genetic pattern, orthodontic and surgical management of multiple supplementary impacted teeth in a rare, cleidocranial dysplasia patient: a case report. Medicina (Kaunas). (2021) 57:1350. doi: 10.3390/medicina57121350

95. Abu-Qamar MZ, Vafeas C, Ewens B, Ghosh M, Sundin D. Postgraduate nurse education and the implications for nurse and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. (2020) 92:104489. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104489

96. Nguyen VNB, Brand G, Gardiner S, Moses S, Collison L, Griffin K, et al. A snapshot of Australian primary health care nursing workforce characteristics and reasons they work in these settings: a longitudinal retrospective study. Nurs Open. (2023) 10:5462–75. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1785

97. Taylor A, Staruchowicz L. The experience and effectiveness of nurse practitioners in orthopaedic settings: a comprehensive systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. (2012) 10:1–22. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2012-249

98. Saccomanno S, Saran S, De Luca M, Fioretti P, Gallusi G. Prevention of malocclusion and the importance of early diagnosis in the Italian young population. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2022) 23:178–82. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2022.23.03.02

99. Zou J, Meng M, Law CS, Rao Y, Zhou X. Common dental diseases in children and malocclusion. Int J Oral Sci. (2018) 10:7. doi: 10.1038/s41368-018-0012-3

100. Rodríguez-Fuentes DE, Fernández-Garza LE, Samia-Meza JA, Barrera-Barrera SA, Caplan AI, Barrera-Saldaña HA. Mesenchymal stem cells current clinical applications: a systematic review. Arch Med Res. (2021) 52:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.08.006

101. Balzanelli MG, Distratis P, Lazzaro R, Pham VH, Tran TC, Dipalma G, et al. Analysis of gene single nucleotide polymorphisms in COVID-19 disease highlighting the susceptibility and the severity towards the infection. Diagnostics. (2022) 12:2824. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12112824

102. Balzanelli MG, Distratis P, Catucci O, Cefalo A, Lazzaro R, Inchingolo F, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: the secret children’s weapons against the SARS-CoV-2 lethal infection. Appl Sci. (2021) 11:1696. doi: 10.3390/app11041696

103. Trávníčková M, Bačáková L. Application of adult mesenchymal stem cells in bone and vascular tissue engineering. Physiol Res. (2018) 67:831–50. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933820

104. Debela DT, Muzazu SG, Heraro KD, Ndalama MT, Mesele BW, Haile DC, et al. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: current perspectives. SAGE Open Med. (2021) 9:20503121211034366. doi: 10.1177/20503121211034366

105. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: gLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 2021(71):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

106. Merriel SWD, Ingle SM, May MT, Martin RM. Retrospective cohort study evaluating clinical, biochemical and pharmacological prognostic factors for prostate cancer progression using primary care data. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e044420. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044420

107. Ganesh K, Massagué J. Targeting metastatic cancer. Nat Med. (2021) 27:34–44. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01195-4

108. Marquardt S, Solanki M, Spitschak A, Vera J, Pützer BM. Emerging functional markers for cancer stem cell-based therapies: understanding signaling networks for targeting metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. (2018) 53:90–109. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.06.006

109. Ronsivalle V, Nucci L, Bua N, Palazzo G, La Rosa S. Elastodontic appliances for the interception of malocclusion in children: a systematic narrative hybrid review. Children (Basel). (2023) 10:1821. doi: 10.3390/children10111821

110. Ureni R, Verdecchia A, Suárez-Fernández C, Mereu M, Schirru R, Spinas E. Effectiveness of elastodontic devices for correcting sagittal malocclusions in mixed dentition patients: a scoping review. Dent J (Basel). (2024) 12:247. doi: 10.3390/dj12080247

111. Yang X, Lai G, Wang J. Effect of orofacial myofunctional therapy along with preformed appliances on patients with mixed dentition and lip incompetence. BMC Oral Health. (2022) 22:586. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02645-w

112. Mahdavifard H, Noorollahian S, Omid A, Yamani N. What competencies does an orthodontic postgraduate need? BMC Med Educ. (2024) 24:1461. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-06475-y

113. Baneshi M, O’Malley L, El-Angbawi A, Thiruvenkatachari B. Effectiveness of clear orthodontic aligners in correcting malocclusions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. (2025) 25:102081. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2024.102081

114. Barnett AS, Bahnson TD, Piccini JP. Recent advances in lesion formation for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2016) 9. 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003299 e003299. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003299

115. Myrlund R, Dubland M, Keski-Nisula K, Kerosuo H. One year treatment effects of the eruption guidance appliance in 7- to 8-year-old children: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Orthod. (2015) 37:128–34. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cju014

116. Almekkawy M, Chen J, Ellis MD, Haemmerich D, Holmes DR, Linte CA, et al. therapeutic systems and technologies: state-of-the-art applications, opportunities, and challenges. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. (2020) 13:325–39. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2019.2908940

117. De Gabriele O, Dallatana G, Vasudavan S, Wilmes B. CAD/CAM-Guided microscrew insertion for horseshoe distalization appliances. J Clin Orthod. (2021) 55:384–97.34464337

118. Engineering (US), N.A. of; Medicine (US), I. of; Ekelman, K.B. New Medical Devices and Health Care. In New Medical Devices: Invention, Development, and Use; National Academies Press (US), (1988).

119. Breuer JA, Ahmed KH, Al-Khouja F, Macherla AR, Muthoka JM, Abi-Jaoudeh N. Interventional oncology: new techniques and new devices. Br J Radiol. (2022) 95:20211360. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20211360

120. Bambini F, Orilisi G, Quaranta A, Memè L. Biological oriented immediate loading: a new mathematical implant vertical insertion protocol, five-year follow-up study.. Materials (Basel. (2021) 14:387. doi: 10.3390/ma14020387

121. Casu C, Mannu C. Atypical afta Major healing after photodynamic therapy. Case Rep Dent. (2017) 2017:8517470. doi: 10.1155/2017/8517470

122. Casu C, Orrù G, Scano A. Curcumin/H2O2 photodynamically activated: an antimicrobial time-response assessment against an MDR strain of Candida Albicans. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2022) 26:8841–51. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202212_30556

123. Casu C, Murgia MS, Orrù G, Scano A. Photodynamic therapy for the successful management of cyclosporine-related gum hypertrophy: a novel therapeutic option. J Public Health Res. (2022) 11:22799036221116177. doi: 10.1177/22799036221116177

124. Farronato G, Maspero C, Farronato D. Orthodontic movement of a dilacerated maxillary incisor in mixed dentition treatment. Dent Traumatol. (2009) 25:451–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00722.x

125. Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Abenavoli FM, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AD, Servili A, et al. A hypothetical correlation between hyaluronic acid gel and development of cutaneous metaplastic synovial cyst. Head Face Med. (2010) 6:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-6-13

126. Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Abenavoli FM, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AD, Corelli R, et al. Upper eyelid reconstruction: a short report of an eyelid defect following a thermal burn. Head Face Med. (2009) 5:26. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-5-26

127. Limongelli L, Cascardi E, Capodiferro S, Favia G, Corsalini M, Tempesta A, et al. Multifocal amelanotic melanoma of the hard palate: a challenging case. Diagnostics (Basel). (2020) 10:424. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10060424

128. Memè L, Bambini F, Pizzolante T, Sampalmieri F, Bianchi A, Mummolo S. Evaluation of a single non-surgical approach in the management of peri-implantitis: glycine powder air-polishing versus ultrasonic device. Oral Implantol J Innov Adv Techniq Oral Health. (2024) 16:67–78. doi: 10.11138/oi.v16i2.44

129. Meme L, Grilli F, Pizzolante T, Capogreco M, Bambini F, Sampalmieri F, et al. Clinical and histomorphometric comparison of autologous dentin graft versus a deproteinized bovine bone graft for socket preservation. Oral and Implantology: A Journal of Innovations and Advanced Techniques for Oral Health. (2024) 16:101–6. doi: 10.11138/oi.v16i2.47

130. Palermo A, Naciu AM, Tabacco G, Manfrini S, Trimboli P, Vescini F, et al. Calcium citrate: from biochemistry and physiology to clinical applications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. (2019) 20:353–64. doi: 10.1007/s11154-019-09520-0

131. Saccomanno S, Martini C, D’Alatri L, Farina S, Grippaudo C. A specific protocol of myo-functional therapy in children with down syndrome. A pilot study. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2018) 19:243–6. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2018.19.03.14

132. Saccomanno S, Di Tullio A, D’Alatri L, Grippaudo C. Proposal for a myofunctional therapy protocol in case of altered lingual frenulum. A pilot study. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2019) 20:67–72. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2019.20.01.13

133. Saccomanno S, Saran S, Laganà D, Mastrapasqua RF, Grippaudo C. Motivation, perception, and behavior of the adult orthodontic patient: a survey analysis. Biomed Res Int. (2022) 2022:2754051. doi: 10.1155/2022/2754051

134. Upadhyay V, Fu Y-X, Bromberg JS. From infection to colonization: the role of Microbiota in transplantation. Am J Transplant. (2013) 13:829. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12232

135. Levrini L, Carganico A, Deppieri A, Saran S, Bocchieri S, Zecca PA, et al. Predictability of invisalign® clear aligners using OrthoPulse®: a retrospective study. Dent J (Basel). (2022) 10:229. doi: 10.3390/dj10120229

136. Upadhyay M, Abu Arqub S. Biomechanics of clear aligners: hidden truths & first principles. J. World Fed Orthod. (2022) 11:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejwf.2021.11.002

137. Tamer İ, Öztaş E, Marşan G. Orthodontic treatment with clear aligners and the scientific reality behind their marketing: a literature review. Turk J Orthod. (2019) 32:241–6. doi: 10.5152/TurkJOrthod.2019.18083

138. Jiang W, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Shen Y, Yen E, Zou B. Bioceramic micro-fillers reinforce antibiofilm and remineralization properties of clear aligner attachment materials. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2023) 11:1346959. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1346959

139. Alam MK, Hajeer MY, Alahmed MA, Alrubayan SM, Almasri MF. A comparative study on the efficiency of clear aligners versus conventional braces in adult orthodontic patients. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. (2024) 16:S3637–9. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_1161_24

140. Saccomanno S, Antonini G, D’Alatri L, D’Angeloantonio M, Fiorita A, Deli R. Case report of patients treated with an orthodontic and myofunctional protocol. Eur J Paediatr Dent. (2014) 15:184–6.25101498

141. Inchingolo F, Inchingolo AM, Palmieri G, Di Pede C, Garofoli G, de Ruvo E, et al. Root resorption during orthodontic treatment with clear aligners vs. Fixed appliances—a systematic review. Appl Sci. (2024) 14:690. doi: 10.3390/app14020690

142. Weir T. Clear aligners in orthodontic treatment. Aust Dent J. (2017) 62(Suppl 1):58–62. doi: 10.1111/adj.12480

143. Wang Y, Long H, Zhao Z, Bai D, Han X, Wang J, et al. Expert consensus on the clinical strategies for orthodontic treatment with clear aligners. Int J Oral Sci. (2025) 17:19. doi: 10.1038/s41368-025-00350-2

145. Liu J, Zhang C, Shan Z. Application of artificial intelligence in orthodontics: current state and future perspectives. Healthcare (Basel). (2023) 11:2760. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11202760

146. Alam MK, Abutayyem H, Kanwal B, Shayeb MAL. Future of orthodontics—a systematic review and meta-analysis on the emerging trends in this field. J Clin Med. (2023) 12(532). doi: 10.3390/jcm12020532

147. Kahn S, Ehrlich P, Feldman M, Sapolsky R, Wong S. The jaw epidemic: recognition, origins, cures, and prevention. Bioscience. (2020) 70:759–71. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biaa073

148. Šitum M, Filipović N, Buljan M. A reminder of skin cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. (2021) 291:58.

149. Sutherland K, Vanderveken OM, Tsuda H, Marklund M, Gagnadoux F, Kushida CA, et al. Oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: an update. J Clin Sleep Med. (2014) 10:215–27. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3460

150. Phillips CL, Grunstein RR, Darendeliler MA, Mihailidou AS, Srinivasan VK, Yee BJ, et al. Health outcomes of continuous positive airway pressure versus oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2013) 187:879–87. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2223OC

151. Inchingolo AD, Ferrara I, Viapiano F, Netti A, Campanelli M, Buongiorno S, et al. Rapid maxillary expansion on the adolescent patient: systematic review and case report. Children (Basel). (2022) 9:1046. doi: 10.3390/children9071046

152. De Gabriele O, Dallatana G, Riva R, Vasudavan S, Wilmes B. The easy driver for placement of palatal Mini-implants and a maxillary expander in a single appointment. J Clin Orthod. (2017) 51:728–37.29360638

153. Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AD, Corelli R, Inchingolo AM, et al. Clinical case-study describing the use of skin-perichondrium-cartilage graft from the auricular concha to cover large defects of the nose. Head Face Med. (2012) 8:10. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-8-10

154. White DP, Shafazand S. Mandibular advancement device vs. CPAP in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: are they equally effective in short term health outcomes? J Clin Sleep Med. (2013) 9:971–2. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3008

155. Sharples L, Glover M, Clutterbuck-James A, Bennett M, Jordan J, Chadwick R, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness results from the randomised controlled trial of oral mandibular advancement devices for obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea (TOMADO) and long-term economic analysis of oral devices and continuous positive airway pressure. Health Technol Assess. (2014) 18:1–296. doi: 10.3310/hta18670

156. Gogou ES, Psarras V, Giannakopoulos NN, Minaritzoglou A, Tsolakis IA, Margaritis V, et al. Comparing efficacy of the mandibular advancement device after drug-induced sleep endoscopy and continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. (2024) 28:773–88. doi: 10.1007/s11325-023-02958-2

157. Avvanzo P, Ciavarella D, Avvanzo A, Giannone N, Carella M, Lo Muzio L. Immediate placement and temporization of implants: three- to five-year retrospective results. J Oral Implantol. (2009) 35:136–42. doi: 10.1563/1548-1336-35.3.136

158. Baxmann M, Baráth Z, Kárpáti K. The role of psychology and communication skills in orthodontic practice: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. (2024) 24:1472. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-06451-6

159. Ma J, Huang J, Jiang J-H. Morphological analysis of the alveolar bone of the anterior teeth in severe high-angle skeletal class II and class III malocclusions assessed with cone-beam computed tomography. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0210461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210461

160. Athanasiou AE. Global guidelines for education and their impact on the orthodontics profession through the years. Semin Orthod. (2024) 30:385–8. doi: 10.1053/j.sodo.2024.04.010

161. Zhang Y, Gu L, Du B, Xu J, Du S. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of orthodontic treatment among student patients preparing for or undergoing treatment. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:17838. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-97801-x

162. Oh PY, Chadwick SM. Perceptions of orthodontic specialist training in the United Kingdom: a national survey of postgraduate orthodontic student opinion. J Orthod. (2016) 43:202–17. doi: 10.1080/14653125.2016.1204510

163. Chawla RK, Ryan FS, Cunningham SJ. Orthodontic Trainees’ perceptions of effective feedback in the United Kingdom. Eur J Dent Educ. (2025) 29:211–8. doi: 10.1111/eje.13063

164. Gaunt A, Markham DH, Pawlikowska TRB. Exploring the role of self-motives in postgraduate Trainees’ feedback-seeking behavior in the clinical workplace: a multicenter study of workplace-based assessments from the United Kingdom. Acad Med. (2018) 93:1576–83. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002348

165. Gaunt A, Patel A, Fallis S, Rusius V, Mylvaganam S, Royle TJ, et al. Surgical trainee feedback-seeking behavior in the context of workplace-based assessment in clinical settings. Acad Med. (2017) 92:827–34. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001523

166. Saran S, Saccomanno S, Petricca MT, Carganico A, Bocchieri S, Mastrapasqua RF, et al. Physiotherapists and Osteopaths’ attitudes: training in management of temporomandibular disorders. Dent J (Basel). (2022) 10:210. doi: 10.3390/dj10110210

167. Preshaw PM, Minnery H, Dunn I, Bissett SM. Teamworking in dentistry: the importance for dentists, dental hygienists and dental therapists to work effectively together-A narrative review. Int J Dent Hyg. (2024. doi: 10.1111/idh.12874

168. Teusner DN, Amarasena N, Satur J, Chrisopoulos S, Brennan DS. Applied scope of practice of oral health therapists, dental hygienists and dental therapists. Aust Dent J. (2016) 61:342–9. doi: 10.1111/adj.12381

169. Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, Benishek LE, Thompson D, Pronovost PJ, et al. Teamwork in healthcare: key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychol. (2018) 73:433–50. doi: 10.1037/amp0000298

170. McLaney E, Morassaei S, Hughes L, Davies R, Campbell M, Di Prospero L. A framework for interprofessional team collaboration in a hospital setting: advancing team competencies and behaviours. Healthc Manage Forum. (2022) 35:112–7. doi: 10.1177/08404704211063584

171. Brandt B, Lutfiyya MN, King JA, Chioreso C. A scoping review of interprofessional collaborative practice and education using the Lens of the triple aim. J Interprof Care. (2014) 28:393–9. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.906391

172. Farronato M, Farronato D, Giannì AB, Inchingolo F, Nucci L, Tartaglia GM, et al. Effects on muscular activity after surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion: a prospective observational study. Bioengineering. (2022) 9:361. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering9080361

173. Inchingolo AD, Dipalma G, Inchingolo AM, Malcangi G, Santacroce L, D’Oria MT, et al. The 15-months clinical experience of SARS-CoV-2: a literature review of therapies and adjuvants. Antioxidants (Basel. (2021) 10(881). doi: 10.3390/antiox10060881

174. Maheshwer B. Chapter 48—survey studies and questionnaires. In: Eltorai AEM, Bakal JA, DeFroda S, Owens BD, editors. Translational Sports Medicine. Cambridge (MA): Academic Press (2023). p. 229–32.

175. Ghafourifard M. Survey fatigue in questionnaire based research: the issues and solutions. J Caring Sci. (2024) 13:214–5. doi: 10.34172/jcs.33287

176. Reducing Respondents’ Perceptions of Bias in Survey Research - Adam Mayer. (2021). Available online: Available online at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/20597991211055952 (Accessed on July 8, 2025).

177. Behind the Numbers: Questioning Questionnaires - Katja Einola, Mats Alvesson. (2021). Available online: Available online at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1056492620938139 (Accessed on 8 July 2025).

178. LaDonna KA, Taylor T, Lingard L. Why open-ended survey questions are unlikely to support rigorous qualitative insights. Acad Med. (2018) 93:347–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002088

179. Kelly M, Ellaway RH, Reid H, Ganshorn H, Yardley S, Bennett D, et al. Considering axiological integrity: a methodological analysis of qualitative evidence syntheses, and its implications for health professions education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. (2018) 23:833–51. doi: 10.1007/s10459-018-9829-y

180. Rich J, Handley T, Inder K, Perkins D. An experiment in using open-text comments from the Australian rural mental health study on health service priorities. Rural Remote Health. (2018) 18:4208. doi: 10.22605/RRH4208

181. Castleman B, Meyer K. Financial constraints & collegiate student learning: a behavioral economics perspective. Daedalus. (2019) 148:195–216. doi: 10.1162/daed_a_01767

182. (PDF) Financial Inclusion in Rural Areas: Challenges and Opportunities Available online: Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368691910_Financial_Inclusion_in_Rural_Areas_Challenges_and_Opportunities (Accessed on July 8, 2025).

Keywords: orthodontics, post-graduate education, malocclusion, invisible aligners, questionnaire, functional therapy

Citation: Saccomanno S, Saran S, Petricca MT, Caramaschi E, Ferrante L, Inchingolo F, Inchingolo AM, Palermo A, Dipalma G and Inchingolo AD (2025) Does orthodontic postgraduate education influence the choice of orthodontic treatment?. Front. Dent. Med. 6:1665422. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2025.1665422

Received: 15 July 2025; Accepted: 18 September 2025;

Published: 7 October 2025.

Edited by:

Abhiram Maddi, Medical University of South Carolina, United StatesReviewed by:

Vincenzo Grassia, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyMichele Tepedino, University of L'Aquila, Italy

Copyright: © 2025 Saccomanno, Saran, Petricca, Caramaschi, Ferrante, Inchingolo, Inchingolo, Palermo, Dipalma and Inchingolo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesco Inchingolo, ZnJhbmNlc2NvLmluY2hpbmdvbG9AdW5pYmEuaXQ=; Angelo Michele Inchingolo, YW5nZWxvbWljaGVsZS5pbmNoaW5nb2xvQHVuaWJhLml0

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Sabina Saccomanno1,†

Sabina Saccomanno1,† Francesco Inchingolo

Francesco Inchingolo