Abstract

Single-cell multiomics (sc-multiomics) is a burgeoning field that simultaneously integrates multiple layers of molecular information, enabling the characterization of dynamic cell states and activities in development and disease as well as treatment response. Studying drug actions and responses using sc-multiomics technologies has revolutionized our understanding of how small molecules intervene for specific cell types in cancer treatment and how they are linked with disease etiology and progression. Here, we summarize recent advances in sc-multiomics technologies that have been adapted and improved in drug research and development, with a focus on genome-wide examination of drug-chromatin engagement and the applications in drug response and the mechanisms of drug resistance. Furthermore, we discuss how state-of-the-art technologies can be taken forward to devise innovative personalized treatment modalities in biomedical research.

Introduction

Intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity has been recognized as a hallmark of cancer and a crucial determinant contributing to drug resistance and cancer therapeutic failure (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Holohan et al., 2013). Despite progresses in molecular biological or/and biochemical measurements can help detect and reveal the overall average signals in malignant tumors (Parikh et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019), drug discovery and development remain challenging due to the various range of treatment sensitivity in diverse cellular subpopulations. Drug research and development (R&D) represents a long-term and complicated process (Sun et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2018). The whole process of drug R&D often starts with basic research for target identification in laboratory studies, followed by drug screening, leading compound and optimization, preclinical and clinical trials in humans, FDA approval and marketing (Loscher et al., 2013; Fidock et al., 2004) (Figure 1). Given the failure in efficacy, unexpected side effects, and time/cost burdens during drug development, many drug candidates that start the journey do not make it to the end, with nearly 90% of human trials failing to achieve registration (Paul et al., 2010; Alcantara et al., 2018). Traditional approaches in studying diseases and identifying anticancer targets rely on bulk sequencing, leading to a limited understanding of diverse disease subtypes and the heterogeneity of cellular responses. Therefore, the demand for new ways to develop drug targets has become an urgent call to action.

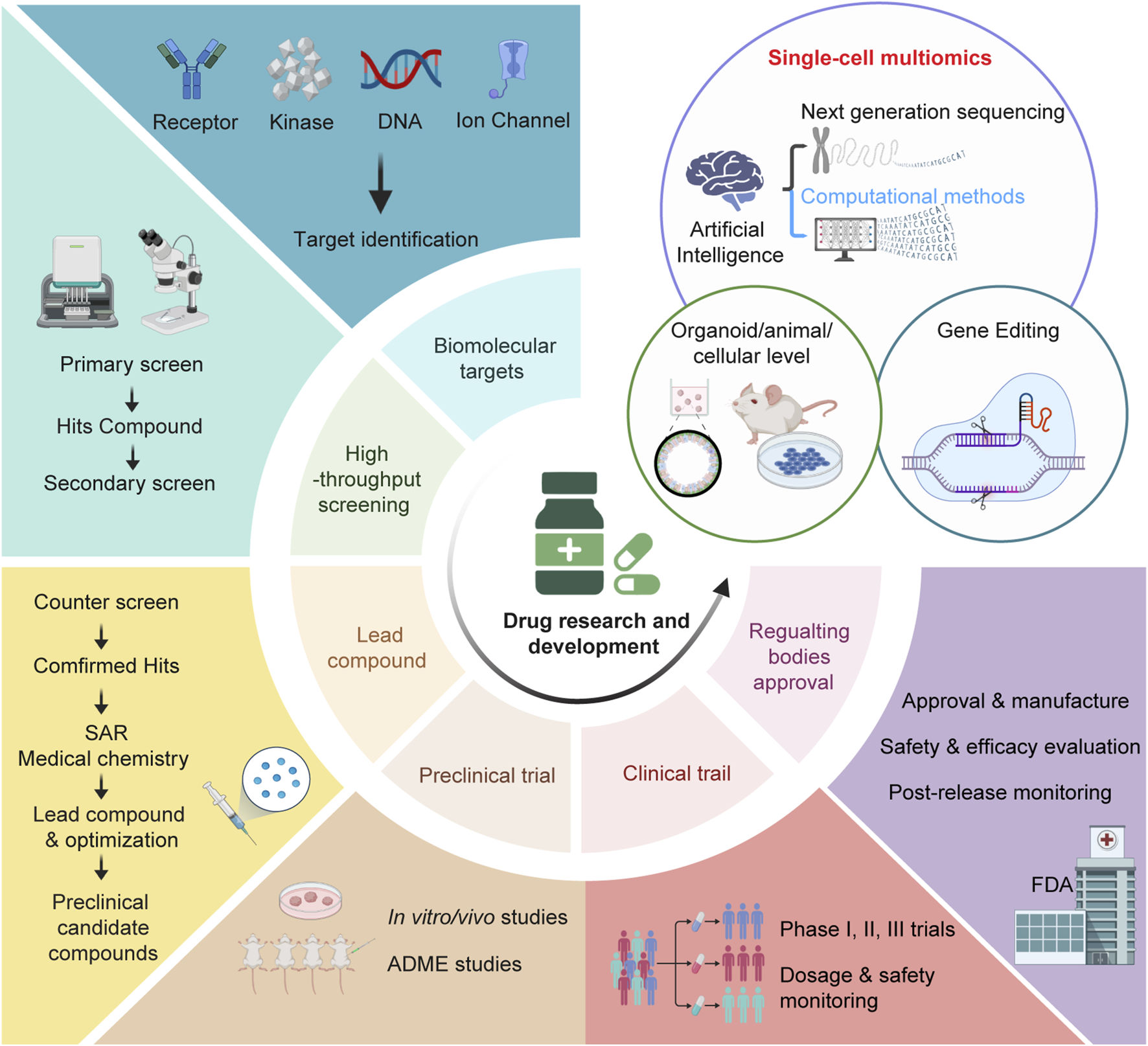

FIGURE 1

The pipeline of drug research and development. The drug research and development (R&D) process comprises several major steps including identification of lead com- pounds, primary screen, counter screen and structure-activity relationship (SAR), testing the efficacy and toxicity preclinical by in vitro/vivo studies and ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity) studies, clinical phases (phase I trials for safety and pharmacokinetics; phase II trials for dose/efficacy/toxicity testing in small patient populations; phase III trials for dose/efficacy/toxicity testing in large patient populations). Through all these processes, culminating data will be evaluated by drug regulatory industry like FDA (Food and Drug Administration) to determine the approval for marketing and use. Single-cell multiomics, in combination with organoid/animal/cellular model and gene editing technologies, is actively shaping drug discovery and promises to make a big difference in finding new drugs and validating drug targets.

In recent years, sc-multiomics enters the area of active and growing investment in drug discovery and development, which offers the capability for researchers to interrogate rare cell subpopulations with minimal sample consumption and multiplexed readouts (Baysoy et al., 2023; Lim et al., 2024; Dimitriu et al., 2022; Macaulay et al., 2017; Hao et al., 2021). The joint analysis of various molecular components using sc-multiomics data can decipher gene regulatory relationships related with tumor heterogeneity (Chen et al., 2023; Kallberg et al., 2022). In this review, we explore advances in the utilization of single-cell multi-omics in drug research and development. Through this comprehensive review, we aim to shed light on the strategies for identifying potential anticancer drug targets and provide insights into unanticipated drug effects from the perspective of sc-multiomics.

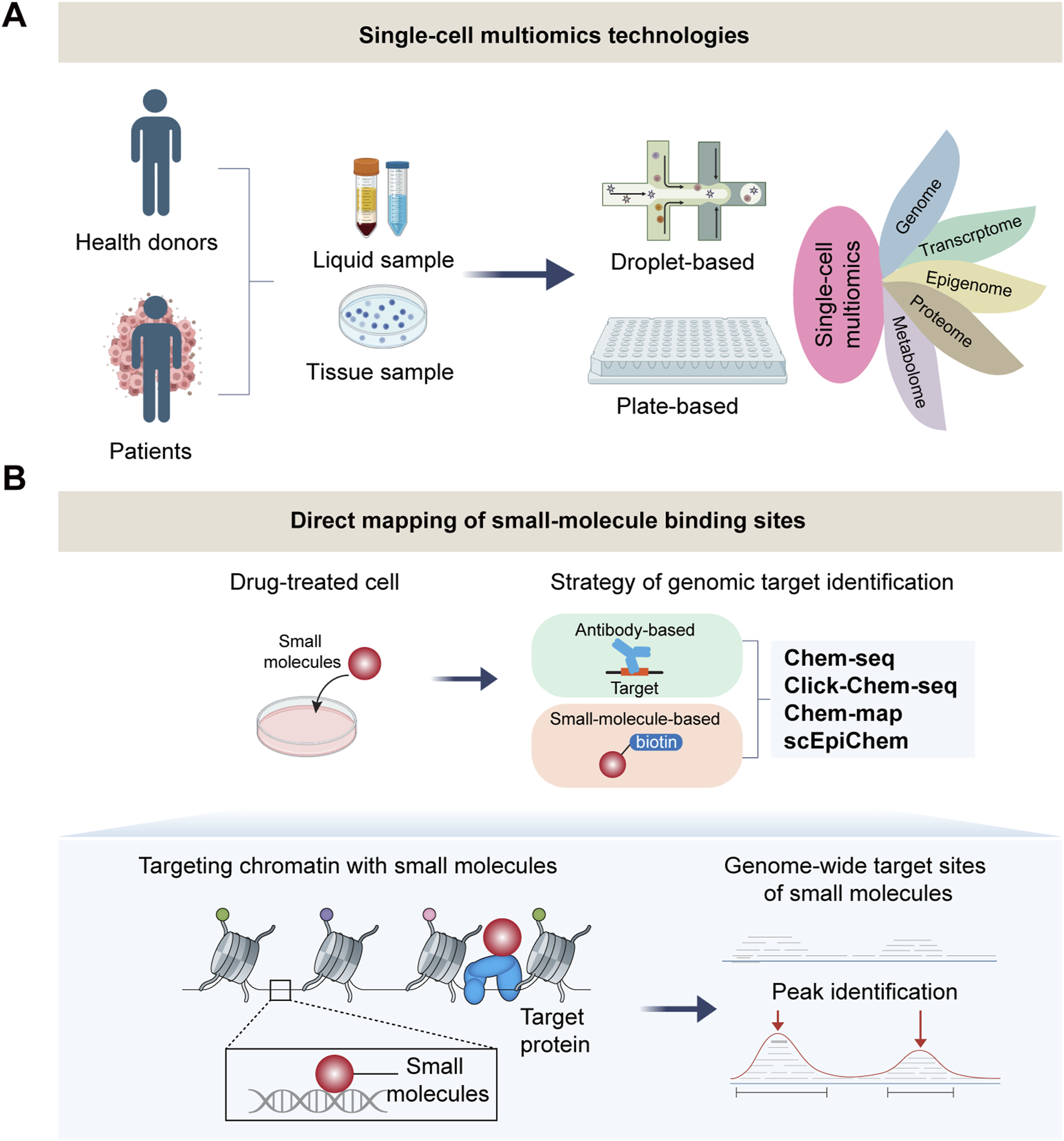

Emerging sc-multiomics technologies

Generally, sc-multiomics technologies jointly measure multi-layered molecular modalities including genome, epigenome, transcriptome, proteome, and/or metabolome in the same cells, which has been proven to have the potential to offer a more comprehensive dissection of underlying molecular mechanisms in gene regulation and cellular diversity and function in physiology and pathology (Ogbeide et al., 2022; Vandereyken et al., 2023; Bai et al., 2021; Macaulay et al., 2015; Dey et al., 2015; Han et al., 2018; Yin et al., 2019; Zachariadis et al., 2020; Kawaoka and Lomvardas, 2024; Izzo et al., 2024; Tedesco et al., 2022; Liscovitch-Brauer et al., 2021; Satpathy et al., 2018; Clark et al., 2018; Markodimitraki et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2023; Bian et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2016; Peterson et al., 2017; Stoeckius et al., 2017; Swanson et al., 2021; Fiskin et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2023; Mimitou et al., 2021; Chamorro Gonzalez et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2021; Gu et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2023; Rodriguez-Meira et al., 2019; Chen A. F. et al., 2022) (Figure 2A). Great strides have been made in the field of sc-multiomics in recent years. For example, simultaneous detection of chromatin accessibility and transcriptome in the same cell provides a direct link between chromatin state and the level of the corresponding transcripts. These approaches fall broadly into three categories based on the single-cell barcoding strategy: (i) plate (or well)-based low-throughput methods (scDam&T-seq (Rooijers et al., 2019), scCAT-seq (Liu et al., 2019)); (ii) droplet-based high-throughput methods (ASTAR-seq (Xing et al., 2020), SNARE-seq (Chen et al., 2019)); (iii) combinatorial indexing-based high-throughput methods (Paired-seq (Zhu et al., 2019), sci-CAR (Cao et al., 2018), SHARE-seq (Ma et al., 2020) and ISSAAC-seq (Xu et al., 2022)) (Table 1). The effect of chromatin potential on transcription can be inferred and interpreted in terms of enhancer regulatory model as well as cell-type specific regulatory impact on target gene expression (Mitra et al., 2024; Kartha et al., 2022).

FIGURE 2

Single-cell multi-omics technologies for mapping drug-target binding. (A) The strategy of single-cell multiomics for studying complex diseases. (B) Single-cell multiomics for direct mapping of small-molecule binding sites in drug response. Cutting-edge technolo- gies achieve genome-wide mapping of small molecule target sites at bulk (Chem-seq, Click-Chem-map, Chem-map) even single-cell level (scEpiChem).

TABLE 1

| Methods | References | Characteristics | Applicable scenarios | Advantages | Disadvantages | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modality | Single-cell strategy | ||||||

| scG&T-seq | ref. (Macaulay et al., 2015) | DNA, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | 1. Disease understanding. 2. Drug target (biomarker) discovery. 3. Drug response and resistance. 4. Personalized medicine |

1. Identification of the cellular heterogeneity at single-cell resolution beyond the transcriptome. 2. High-throughput single-cell technologies allow identification of rare cell types. 3. Linking molecular layers to explore the machnisms of gene regulation. 4. Single-cell multiomics enables the exploration of combined effects between different layers and factors. 5. Predicting the molecular features of missing modality based on machine learning |

1. Limited data quality including sensitivity and specificity for each modality in single-cell multiomics technologies. 2. Suffering from sparse nature of the data due to dropout events. 3. High cost compared to bulk sequencing 4. High level of technical noise leads to difficulties in identifying true biological signals. 5. There is no common analysis pipeline for different single-cell multiomics techmologies |

| DR-seq | ref. (Dey et al., 2015) | DNA, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| Target-seq | ref. (Rodriguez-Meira et al., 2019) | DNA, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| scSIDR-seq | ref. (Han et al., 2018) | DNA, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| sci-L3-RNA/DNA | ref. (Yin et al., 2019) | DNA, RNA | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| Perturb-seq | ref. (Dixit et al., 2016) | sgRNA perturbation, RNA | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| CROP-seq | ref. (Datlinger et al., 2017) | sgRNA perturbation, RNA | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| CRISP-seq | ref. (Jaitin et al., 2016) | sgRNA perturbation, RNA | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| DNTR-seq | ref. (Zachariadis et al., 2020) | whole-genome, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| LiMCA | ref. (Kawaoka and Lomvardas, 2024) | 3D genome, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| Got-ChA | ref. (Izzo et al., 2024) | Chromatin accessibility, genome | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| scGET-seq | ref. (Tedesco et al., 2022) | Chromatin accessibility, heterochromatin | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| CRISPR–sciATAC | ref. (Liscovitch-Brauer et al., 2021) | Chromatin accessibility, genetic perturbations | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| T-ATAC-seq | ref. (Satpathy et al., 2018) | Chromatin accessibility, TCR-encoding genes | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| scCOOL-seq | ref. (Guo et al., 2017) | DNA methylation, Nucleosome occupancy, CNV | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| sci-CAR | ref. (Cao et al., 2018) | Chromatin accessibility, RNA | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| scCAT-seq | ref. (Liu et al., 2019) | Chromatin accessibility, RNA | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| SNARE-seq | ref. (Chen et al., 2019) | Chromatin accessibility, RNA | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| ASTAR-seq | ref. (Xing et al., 2020) | Chromatin accessibility, RNA | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| Paired-seq | ref. (Zhu et al., 2019) | Chromatin accessibility, RNA | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| SHARE-seq | ref. (Ma et al., 2020) | Chromatin accessibility, RNA | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| scNMT-seq | ref. (Clark et al., 2018) | DNA methylation, Nucleosome occupancy, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| scDam&T-seq | ref. (Markodimitraki et al., 2020) | Protein–DNA interactions, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| Paired-Tag | ref. (Zhu et al., 2021) | Protein–DNA interactions, RNA | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| Droplet-based Paired-Tag | ref. (Xie et al., 2023) | Protein–DNA interactions, RNA | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| CoTECH | ref. (Xiong et al., 2021) | Protein–DNA interactions, RNA | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| scMAbID | ref. (Lochs et al., 2024) | Multiple protein–DNA interactions | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| uCoTargetX | ref. (Xiong et al., 2024) | Multiple protein–DNA interactions, RNA | combinatorial indexing | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| scMT-seq | ref. (Hu et al., 2016) | DNA methylation, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| Spear-ATAC | ref. (Pierce et al., 2021) | Chromatin accessibility, sgRNA | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| Perturb-ATAC | ref. (Rubin et al., 2019) | Chromatin accessibility, sgRNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| REAP-seq | ref. (Peterson et al., 2017) | RNA, Cell surface protein | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| CITE-seq | ref. (Stoeckius et al., 2017) | RNA, Cell surface protein | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| ICICLE-seq | ref. (Swanson et al., 2021) | Chromatin accessibility, protein | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| PHAGE-ATAC | ref. (Fiskin et al., 2022) | Chromatin accessibility, mtDNA, protein | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| scTrio-seq | ref. (Hou et al., 2016) | CNVs, DNA methylation, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| scTrio-seq2 | ref. (Bian et al., 2018) | SCNAs, DNA methylation, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| scNanoCOOL-seq | ref. (Lin et al., 2023) | CNVs, DNA methylome, Chromatin accessibility, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| TEA-seq | ref. (Swanson et al., 2021) | RNA, Cell surface protein, Chromatin accessibility | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| NEAT-seq | ref. (Chen et al., 2022a) | Chromatin accessibility, Intra-nuclear protein, genome | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| PHAGE-ATAC | ref. (Fiskin et al., 2022) | Chromatin accessibility, mtDNA, protein | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| ASAP-seq | ref. (Mimitou et al., 2021) | Chromatin accessibility, mtDNA, RNA, protein | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| DOGMA-seq | ref. (Mimitou et al., 2021) | Chromatin accessibility, mtDNA, RNA, protein | droplet-based | Large sc-multiomics landsacpe | |||

| scEC&T-seq | ref. (Chamorro Gonzalez et al., 2023) | extrachromosomal circular DNAs, RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| scNOMeRe-seq | ref. (Wang et al., 2021) | chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation and RNA | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| iscCOOL-seq | ref. (Gu et al., 2019) | chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

| snm3c-seq | ref. (Liu et al., 2023) | chromatin conformation, DNA methylation | plate/well/tube-based | Biological context with limited cell number | |||

Single-cell multiomics methods and the application in drug research and development.

Of note, one aspect of sc-multiomics that is under-explored is profiling of protein-DNA interactomics including genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites. We and other groups in this field have developed a series of single-cell multimodality epigenomic technologies (Table 1). These techniques, Paired-Tag (Zhu et al., 2021) and CoTECH (Xiong et al., 2021), both rely on the use of the protein A-Tn5 (PAT) protein fusion for in situ antibody-targeted tagmentation to histone modification loci, similar to the sole single-cell protein-DNA method CUT&Tag (Kaya-Okur et al., 2019) and CoBATCH (Wang et al., 2019) with high signal-to-noise ratio. It is also exciting to witness the emergence of new methods such as uCoTargetX for profiling multiple histone marks and transcriptome at one time in single-cells (Xiong et al., 2024; Lochs et al., 2024). Moreover, the sc-multiomics technologies with the ability to simultaneously profile at least three molecular layers including scNMT-seq (Clark et al., 2018), scCOOL-seq (Guo et al., 2017), scTrio-seq (Bian et al., 2018; Hou et al., 2016), scNOMeRe-seq (Wang et al., 2021) and DOGMA-seq (Mimitou et al., 2021) or multiple histone modifications such as scMulti-CUT&Tag (Gopalan et al., 2021), MulTI-Tag (Meers et al., 2022), nano-CUT&Tag (nano-CT) (Bartosovic and Castelo-Branco, 2022), and nanobody-tethered transposition followed by sequencing (NTT-seq) (Stuart et al., 2022) at single-cell resolution greatly improves the study of highly complex molecular events. Our intention here is to provide a brief overview of current sc-multiomics technologies (Table 1), applications of sc-multiomics in drug research and development are further discussed below.

Genome-wide determination of drug-chromatin engagement

Small molecules that target specific signaling pathways and epigenetic processes have the potential to alter gene expression and eventually influence cell states (Yuan et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2012). Many antitumor drugs directly or indirectly target chromatin proteins, and these interactions are closely associated with the DNA-related processes such as DNA repair, replication, and topology maintenance (Neefjes et al., 2024). With the development of next-generation sequencing and new chemical library-screening approaches (Satam et al., 2023; Rodriguez and Krishnan, 2023), the ability to map the genome-wide interactions between small molecules with chromatin could provide new insights into the mechanisms, by which small molecules influence cellular behaviors and functions in anticancer treatment (Anders et al., 2014; Rodriguez and Miller, 2014).

Excitedly, emerging technologies have realized detection of the drug-DNA interaction in recent years. Chem-seq (Anders et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2014) and Click-Chem-seq (Tyler et al., 2017), leveraging affinity tags reacting with the functionalized drugs, enable the identification of global interactions of small molecules with chromatin genome-wide in bulk samples. Furthermore, Chem-map was based on small-molecule-directed transposase Tn5 tagmentation. They used Chem-map to reveal that JQ1 binding sites were largely overlapped (93%) with peaks identified by CUT&Tag for its putative protein target BRD4 in K562 cell, and found that Chem-map outperformed Click-Chem-seq in signal accumulation (Yu et al., 2023). However, these technologies measure the drug-target engagement in bulk samples, which requires millions of cells—not always an option. To gain better understanding of the functional effect of small molecules and where in the genome the drugs are located at single-cell resolution, our laboratory just recently presented, for the first time, a sc-multiomics method dubbed scEpiChem, achieving joint measurement of drug-chromatin binding and multimodal epigenome in the same cells (Dong et al., 2024). Notably, scEpiChem allows for mapping of epigenomic and drug-binding information from tens of thousands of single cells in a single experiment by adopting split-and-pool barcoding strategy, representing a highly sensitive and scalable approach to dissect the interplay of drug-chromatin in single cells. Given the tumor heterogeneity and molecular dynamics, we believe that the application of scEpiChem holds great promises to explore the mechanisms of drug action and drug specificity in single cells (Figure 2B).

The application of sc-multiomics in identifying drug targets

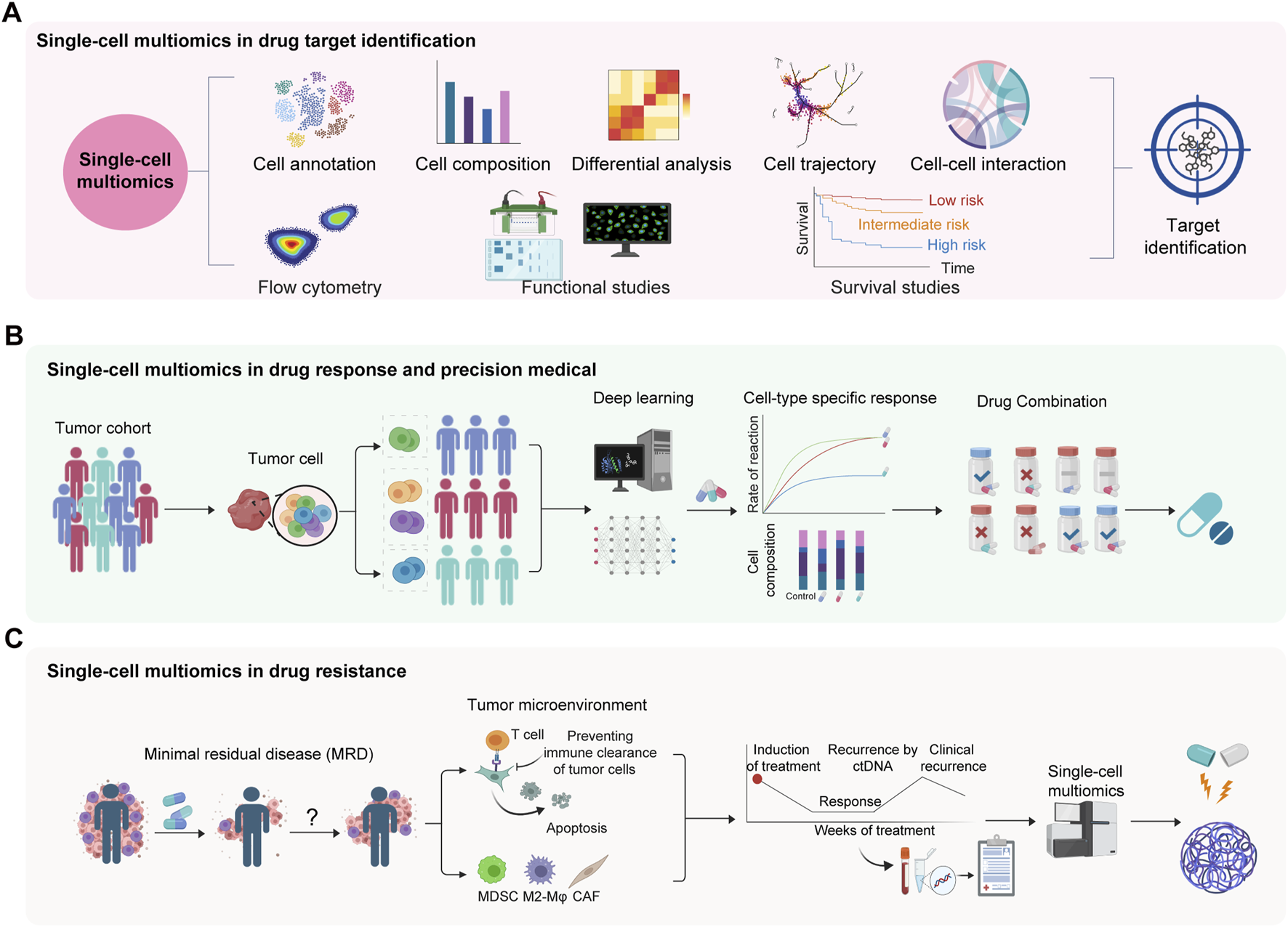

The identification of practical drug targets and cellular distribution has significant implications in pharmaceutical industries and research. The discovery of novel natural active small molecule targets presents vast opportunities for advancing the treatment of related diseases. Generally, conventional bulk sequencing allows for systematically elucidating disease pathogenesis and various phenotypes at the individual level. However, bulk technologies provide averaged signals of population of cells for each sample, which fails to capture the heterogeneity and variations within cell populations. The advent of sc-multiomics has opened up new avenues in drug screening, efficacy evaluation, and pharmacological research through comprehensive global analyses. These analyses encompass the identification of drug targets within specific cell subclusters, the elucidation of gene expression dynamics, the tracking of cell trajectories, and the investigation of cell-cell interactions (Spaethling and Eberwine, 2013; Yang et al., 2020; Erfanian et al., 2022) (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3

Applications of single-cell multi-omics in drug target identification, and deciphering of drug response and resistance. (A) Single-cell multiomics for target identification in complex diseases. (B) Single-cell multiomics in drug response and precision medical. (C) Single-cell multiomics in drug resistance. Minimal residual disease (MRD) might be capable of reinitiating tumors and causing recurrence. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell. CAF, cancer associated fibroblast.

In the realm of drug discovery, changes in the cell function or immunophenotype of drug candidates can be detected using single-cell omics based on ex vivo or in vivo designs. The fields of single-cell proteomics and transcriptomics offer significant capabilities in this regard. A recent single-cell omics study, for instance, revealed that LILRB4 was highly enriched in pre-matured plasma cells of patients compared to those in durable remission, thereby establishing its potential as a promising immunotherapy target for both tumor cells and myeloid-derived suppressive cells in multiple myeloma (Gong et al., 2024). Recently, the field has witnessed exciting breakthroughs in single-cell proteomics techniques, enabling the quantification of thousands of proteins from single mammalian cells (Bennett et al., 2023; Slavov, 2023). These approaches have been applied to assess drug effects on target proteins and explore the heterogeneous cellular responses to drugs under different treatment conditions over time (Vegvari et al., 2022; Ahmad and Budnik, 2023). Joint analyses of scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data demonstrated enhanced transcriptional activation of primitive cells to other lineages besides myeloid in resistant and relapsed samples and revealed MEF2C as a potential therapeutic target in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (Lambo et al., 2023). Qi et al. uncovered a potential therapeutic strategy by disrupting FAP + fibroblasts and SPP1+ macrophages interaction to improve immunotherapy in colorectal tumor using scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics (Qi et al., 2022). In addition to the aforementioned study, Tietscher et al. analyzed molecular characterization of depletion-like T cells and identified IL-15 as a potential therapeutic target through sc-multiomics analysis (Tietscher et al., 2023).

Furthermore, single-cell technologies are invaluable at the preclinical stage for elucidating how small molecules alter the molecular dynamics and immunophenotype, facilitating the assessment of the immunotoxicology of potential drug candidates (Nassar et al., 2021). Comparison between human and model animal using different modalities of sc-multiomics data may reveal similarities and dissimilarities in tumor microenvironment (TME), enabling data-driven selection of the most effective tumor model at the preclinical stage (Author Anonymous, 2020). In the clinical stage, sc-multiomics enables the assessment of specific pharmacodynamic (PD) markers, the effects of toxicity, making safety, and receptor occupancy (Nassar et al., 2021). These latest discoveries based on sc-multiomics provide a unique understanding of complex biological processes, from target identification to clinical decision-making, which paves the way for innovative strategies in improving and personalizing treatments.

The application of sc-multiomics in drug response and resistance

Single-cell multiomics, a rapidly evolving technology, has significantly advanced our understanding of cellular responses to drugs, yielding an unambiguous view of drug efficacy and resistance mechanisms. A pioneer study by Trapnell laboratory developed sci-Plex for enabling high-content screening of exposure of 188 compounds in three cancer cell lines in up to 650,000 cells to detect genetic requirements for individual cells’ response to a drug exposure. This method has been particularly effective in evaluating the synergistic effects of drug combinations (Srivatsan et al., 2020). A similar strategy was employed to develop sciPlex-ATAC-seq to investigate drug-altered distal regulatory sites that were predictive of compound- and dose-dependent effects on transcription (Booth et al., 2023). Moreover, integrating Sci-Plex with CRISPR screening (sci-Plex-GxE) establishes connections between gene and drug perturbations, providing insights into how specific genetic modifications influence drug responses (McFaline-Figueroa et al., 2024). These efforts in studying drug response and resistance at single-cell level have been further boosted by the recent progresses made in patients. Through the identification and analysis of therapy-induced clonal evolution and resistance pathways in minimal residual clones at the single-cell level, it has been demonstrated that cancer cells rapidly adapt to induction treatment through transcriptional adaptation, metabolic adaptation, and specialized immune evasion in multiple myeloma (Cui et al., 2024). Another study also provided a basis to learn drug resistance by identifying resistance pathways and therapeutic targets in relapsed multiple myeloma patients using single-cell multi-omics (Cohen et al., 2021). These studies reveal the mechanisms in patient prognosis and drug response.

Several innovative methodologies have recently been developed to improve the utility of single-cell technologies in drug response evaluation. Using the strategy of single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides with poly-A tails to uniquely label each drug-treated sample, SBOs-scRNA-seq facilitated the detection of cellular responses over varying time points and drug concentrations (Shin et al., 2019). Notable technical advancements such as DRUG-seq have proven effective in classifying compounds based on their mechanisms of action (Ye et al., 2018). PLATE-seq offered a cost-effective alternative for such analyses by incorporating sample-specific barcodes with specialized oligo-dT primers (Pang et al., 2022). Additionally, single-cell resolution imaging of drug molecules has been achieved by CATCH, revealing their distribution across various brain regions and the cell types targeted by small molecules (Pang et al., 2022), and TraCe-seq provided a comprehensive comparison of different treatments at both subgroup and single-cell resolution (Chang et al., 2022). Furthermore, emerging single-cell epigenomic methods have been employed to investigate the heterogeneity of chromatin states in cancers. For example, Grosselin et al. used single-cell ChIP-seq to uncover the heterogeneity of chromatin states in cancers, finding that a small population of tumor cells with resistance chromatin signatures could also be detected in the sensitive tumor, which supports the selection of treatment-resistant cells already present in the initial tumor (Grosselin et al., 2019). This finding aligns with the conclusion that the acquisition of malignant phenotypes after treatment results from the selection of pre-existing drug-resistant subpopulations as revealed by single-cell transcriptome analysis (Brady et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2018). Therefore, sc-multiomics provides mechanistic insights into the mechanisms of therapy-induced resistance and cellular plasticity in targeting tumor evolution (Figures 3B, C). These technologies are opening new avenues for understanding complex drug-cell interactions, paving the way for more effective and personalized therapeutic approaches.

The combination of single-cell multi-omics and artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI)/database-driven sc-multiomics is already making an impact in drug discovery, powering a new generation of companies and laboratories in the search for effective treatments. Computational frameworks are required to address the limited exploration power of existing experimental methods and discover promising therapeutic drug candidates (Sadybekov and Katritch, 2023; Abel et al., 2017).

Large volumes of published researches and numerous clinical trials have illustrated the reliability and practicality of AI-driven sc-multiomics approaches (Kp Jayatunga et al., 2024). Drug2cell can identify specific cellular targets of bioactive molecules based on single-cell RNA-seq data, potentially revealing hidden mechanisms of action and predicting the impact of medicines on specific cell types. Applying Drug2cell to human heart single-cell data, researchers mapped drugs to target-expressing cells (Kanemaru et al., 2023). Several single-cell studies use drug-response transcriptional signatures obtained from cell line experiments and data mining to predict drug effects. For example, scDrug is a bioinformatics workflow using a one-step pipeline to generate cell clustering for scRNA-seq data and two methods to predict drug treatments (Hsieh et al., 2023). In addition, scDEAL predicted the cancer drug response at the single-cell level by integrating large-scale bulk cell line data based on a deep transfer learning framework (Chen J. et al., 2022). Furthermore, AI-driven sc-multiomics has also made it possible in auto-detection and classification of benign nuclei from cancer cells (Mousavikhamene et al., 2021), precision medicine matching trials (Baysoy et al., 2023), and drug repurposing (Jonker et al., 2024; Prasad and Kumar, 2021).

Various tools related to drug discovery have been developed, and a vast amount of database are now readily available for public use. Many archives and databases for drug-target interaction, drug combination, and drug response have also been established, such as Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (Zhou et al., 2024), Drug Combination Database (DCDB) (Liu et al., 2010), SC2MeNetDrug (Feng et al., 2024), and SuperTarget (Hecker et al., 2012) (Supplementary Table 1). Based on these databases and archives, many studies combine MRI and/or CT imaging with biological pathways and cellular morphology to further characterize a disease (Woloszyk et al., 2019), which could potentially aid in identifying the molecular subtypes of cancer. Together, suitable methods should predict the response to unobserved perturbations or combinations of perturbations. Therefore, AI/database-driven sc-multiomics is reshaping current researches in drug discovery. Such predictive models would be helpful for understanding disease progression and drug response in known and novel cell populations.

Conclusion and perspectives

In conclusion, sc-multiomics provides a multi-molecular readout that has proven its potential for powerful and comprehensive dissection of the complex molecular mechanisms in gene regulation, resulting in a more accurate depiction of individual cell states. Sc-multiomics is particularly well-suited for applications involving rare cell types, as it maximizes the information obtained from each individual cell. Such approaches have immense potential applications in a wide range of research fields, from developmental biology to cancer biology and precision medicine related to drug research and development.

Sc-multiomics, while in its infancy, is still in the early stages of development. One of key challenges for sc-multiomics is balancing single-cell data quality and throughput. The coverage of epigenome and transcriptome for individual cells obtained from current high-throughput methods is still low, hindering the identification of biological cell-to-cell variability beyond technical noise. Thus, many applications have so far been restricted to proof-of-concept stages. More sensitive and highly efficient sc-multiomics technologies are required and expected to facilitate discovering better drugs. Importantly, newly developed CRISPR/Cas9-mediated single-cell tools allow for the manipulation of the specific molecules in different modalities (Dixit et al., 2016; Rubin et al., 2019; Datlinger et al., 2017; Jaitin et al., 2016; Pierce et al., 2021), and the sc-multiomics approaches are vital for ensuring the safety and efficacy of CRISPR-based therapeutics, particularly in detecting potential unintended outcomes (Chehelgerdi et al., 2024).

The combination of AI and sc-multiomics aims to address complex problems related to understanding disease mechanisms, target identification, and predicting potential therapeutic drug efficacy. AI’s ability to derive actionable insights from enormous and complex datasets significantly reduces the risk, cost, and time associated with traditional drug discovery methods. As we witness the blending of AI and multi-omics, a significant shift in our current approaches is expected in healthcare, transforming it from a one-size-fits-all model to a more personalized, precision-driven approach.

Statements

Author contributions

JM: Investigation, Writing–original draft. CD: Writing–original draft. AH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. HX: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. HX was supported by grants from the Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2022- RC180-07); CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2022-I2M-1-022); State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology Research Grant (Z22-09). AH was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1100100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32025015 and 32192401), and the Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences.

Acknowledgments

We thank all lab members for critical comments on this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fddsv.2024.1474331/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 1The computational methods and database for drug R&D.

References

1

Author Anonymous (2020). Single-cell analyses in the multi-omics era. Cancer Cell38, 9–10. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.06.015

2

Abel R. Wang L. Harder E. D. Berne B. J. Friesner R. A. (2017). Advancing drug discovery through enhanced free energy calculations. Acc. Chem. Res.50, 1625–1632. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00083

3

Ahmad R. Budnik B. (2023). A review of the current state of single-cell proteomics and future perspective. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.415, 6889–6899. 10.1007/s00216-023-04759-8

4

Alcantara L. M. Ferreira T. C. S. Gadelha F. R. Miguel D. C. (2018). Challenges in drug discovery targeting TriTryp diseases with an emphasis on leishmaniasis. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist8, 430–439. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.09.006

5

Anders L. Guenther M. G. Qi J. Fan Z. P. Marineau J. J. Rahl P. B. et al (2014). Genome-wide localization of small molecules. Nat. Biotechnol.32, 92–96. 10.1038/nbt.2776

6

Bai D. Peng J. Yi C. (2021). Advances in single-cell multi-omics profiling. RSC Chem. Biol.2, 441–449. 10.1039/d0cb00163e

7

Bartosovic M. Castelo-Branco G. (2022). Multimodal chromatin profiling using nanobody-based single-cell CUT&Tag. Nat. Biotechnol.41, 794–805. 10.1038/s41587-022-01535-4

8

Baysoy A. Bai Z. Satija R. Fan R. (2023). The technological landscape and applications of single-cell multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.24, 695–713. 10.1038/s41580-023-00615-w

9

Bennett H. M. Stephenson W. Rose C. M. Darmanis S. (2023). Single-cell proteomics enabled by next-generation sequencing or mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods20, 363–374. 10.1038/s41592-023-01791-5

10

Bian S. Hou Y. Zhou X. Li X. Yong J. Wang Y. et al (2018). Single-cell multiomics sequencing and analyses of human colorectal cancer. Science362, 1060–1063. 10.1126/science.aao3791

11

Booth G. T. Daza R. M. Srivatsan S. R. McFaline-Figueroa J. L. Gladden R. G. Furlan S. N. et al (2023). High-capacity sample multiplexing for single cell chromatin accessibility profiling. bioRxiv, 531201. 10.1101/2023.03.05.531201

12

Brady S. W. McQuerry J. A. Qiao Y. Piccolo S. R. Shrestha G. Jenkins D. F. et al (2017). Combating subclonal evolution of resistant cancer phenotypes. Nat. Commun.8, 1231. 10.1038/s41467-017-01174-3

13

Cao J. Cusanovich D. A. Ramani V. Aghamirzaie D. Pliner H. A. Hill A. J. et al (2018). Joint profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in thousands of single cells. Science361, 1380–1385. 10.1126/science.aau0730

14

Chamorro Gonzalez R. Conrad T. Stöber M. C. Xu R. Giurgiu M. Rodriguez-Fos E. et al (2023). Parallel sequencing of extrachromosomal circular DNAs and transcriptomes in single cancer cells. Nat. Genet.55, 880–890. 10.1038/s41588-023-01386-y

15

Chang M. T. Shanahan F. Nguyen T. T. T. Staben S. T. Gazzard L. Yamazoe S. et al (2022). Identifying transcriptional programs underlying cancer drug response with TraCe-seq. Nat. Biotechnol.40, 86–93. 10.1038/s41587-021-01005-3

16

Chehelgerdi M. Chehelgerdi M. Khorramian-Ghahfarokhi M. Shafieizadeh M. Mahmoudi E. Eskandari F. et al (2024). Comprehensive review of CRISPR-based gene editing: mechanisms, challenges, and applications in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer23, 9. 10.1186/s12943-023-01925-5

17

Chen A. F. Parks B. Kathiria A. S. Ober-Reynolds B. Goronzy J. J. Greenleaf W. J. (2022a). NEAT-seq: simultaneous profiling of intra-nuclear proteins, chromatin accessibility and gene expression in single cells. Nat. Methods19, 547–553. 10.1038/s41592-022-01461-y

18

Chen J. Luo X. Qiu H. Mackey V. Sun L. Ouyang X. (2018). Drug discovery and drug marketing with the critical roles of modern administration. Am. J. Transl. Res.10, 4302–4312.

19

Chen J. Wang X. Ma A. Wang Q. E. Liu B. Li L. et al (2022b). Deep transfer learning of cancer drug responses by integrating bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat. Commun.13, 6494. 10.1038/s41467-022-34277-7

20

Chen S. Jiang W. Du Y. Yang M. Pan Y. Li H. et al (2023). Single-cell analysis technologies for cancer research: from tumor-specific single cell discovery to cancer therapy. Front. Genet.14, 1276959. 10.3389/fgene.2023.1276959

21

Chen S. Lake B. B. Zhang K. (2019). High-throughput sequencing of the transcriptome and chromatin accessibility in the same cell. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 1452–1457. 10.1038/s41587-019-0290-0

22

Clark S. J. Argelaguet R. Kapourani C. A. Stubbs T. M. Lee H. J. Alda-Catalinas C. et al (2018). scNMT-seq enables joint profiling of chromatin accessibility DNA methylation and transcription in single cells. Nat. Commun.9, 781. 10.1038/s41467-018-03149-4

23

Cohen Y. C. Zada M. Wang S. Y. Bornstein C. David E. Moshe A. et al (2021). Identification of resistance pathways and therapeutic targets in relapsed multiple myeloma patients through single-cell sequencing. Nat. Med.27, 491–503. 10.1038/s41591-021-01232-w

24

Cui J. Li X. Deng S. Du C. Fan H. Yan W. et al (2024). Identification of therapy-induced clonal evolution and resistance pathways in minimal residual clones in multiple myeloma through single-cell sequencing. Clin. Cancer Res.30, 3919–3936. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-24-0545

25

Datlinger P. Rendeiro A. F. Schmidl C. Krausgruber T. Traxler P. Klughammer J. et al (2017). Pooled CRISPR screening with single-cell transcriptome readout. Nat. Methods14, 297–301. 10.1038/nmeth.4177

26

Dey S. S. Kester L. Spanjaard B. Bienko M. van Oudenaarden A. (2015). Integrated genome and transcriptome sequencing of the same cell. Nat. Biotechnol.33, 285–289. 10.1038/nbt.3129

27

Dimitriu M. A. Lazar-Contes I. Roszkowski M. Mansuy I. M. (2022). Single-cell multiomics techniques: from conception to applications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.10, 854317. 10.3389/fcell.2022.854317

28

Dixit A. Parnas O. Li B. Chen J. Fulco C. P. Jerby-Arnon L. et al (2016). Perturb-seq: dissecting molecular circuits with scalable single-cell RNA profiling of pooled genetic screens. Cell167, 1853–1866. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.038

29

Dong C. Meng X. Zhang T. Guo Z. Liu Y. Wu P. et al (2024). Single-cell EpiChem jointly measures drug-chromatin binding and multimodal epigenome. Nat. Methods21, 1624–1633. 10.1038/s41592-024-02360-0

30

Erfanian N. Derakhshani A. Nasseri S. Fereidouni M. Baradaran B. Jalili Tabrizi N. et al (2022). Immunotherapy of cancer in single-cell RNA sequencing era: a precision medicine perspective. Biomed. Pharmacother.146, 112558. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112558

31

Feng J. Goedegebuure S. P. Zeng A. Bi Y. Wang T. Payne P. et al (2024). sc2MeNetDrug: a computational tool to uncover inter-cell signaling targets and identify relevant drugs based on single cell RNA-seq data. PLoS Comput. Biol.20, e1011785. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011785

32

Fidock D. A. Rosenthal P. J. Croft S. L. Brun R. Nwaka S. (2004). Antimalarial drug discovery: efficacy models for compound screening. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.3, 509–520. 10.1038/nrd1416

33

Fiskin E. Lareau C. A. Ludwig L. S. Eraslan G. Liu F. Ring A. M. et al (2022). Single-cell profiling of proteins and chromatin accessibility using PHAGE-ATAC. Nat. Biotechnol.40, 374–381. 10.1038/s41587-021-01065-5

34

Gong L. Sun H. Liu L. Sun X. Fang T. Yu Z. et al (2024). LILRB4 represents a promising target for immunotherapy by dual targeting tumor cells and myeloid-derived suppressive cells in multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 10.3324/haematol.2024.285099

35

Gopalan S. Wang Y. Harper N. W. Garber M. Fazzio T. G. (2021). Simultaneous profiling of multiple chromatin proteins in the same cells. Mol. Cell81, 4736–4746.e5. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.09.019

36

Grosselin K. Durand A. Marsolier J. Poitou A. Marangoni E. Nemati F. et al (2019). High-throughput single-cell ChIP-seq identifies heterogeneity of chromatin states in breast cancer. Nat. Genet.51, 1060–1066. 10.1038/s41588-019-0424-9

37

Gu C. Liu S. Wu Q. Zhang L. Guo F. (2019). Integrative single-cell analysis of transcriptome, DNA methylome and chromatin accessibility in mouse oocytes. Cell Res.29, 110–123. 10.1038/s41422-018-0125-4

38

Guo F. Li L. Li J. Wu X. Hu B. Zhu P. et al (2017). Single-cell multi-omics sequencing of mouse early embryos and embryonic stem cells. Cell Res.27, 967–988. 10.1038/cr.2017.82

39

Han K. Y. Kim K. T. Joung J. G. Son D. S. Kim Y. J. Jo A. et al (2018). SIDR: simultaneous isolation and parallel sequencing of genomic DNA and total RNA from single cells. Genome Res.28, 75–87. 10.1101/gr.223263.117

40

Hanahan D. Weinberg R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell144, 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

41

Hao Y. Hao S. Andersen-Nissen E. Mauck W. M. 3rd Zheng S. Butler A. et al (2021). Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell184, 3573–3587.e29. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048

42

Hecker N. Ahmed J. von Eichborn J. Dunkel M. Macha K. Eckert A. et al (2012). SuperTarget goes quantitative: update on drug-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res.40, D1113–D1117. 10.1093/nar/gkr912

43

Holohan C. Van Schaeybroeck S. Longley D. B. Johnston P. G. (2013). Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer13, 714–726. 10.1038/nrc3599

44

Hou Y. Guo H. Cao C. Li X. Hu B. Zhu P. et al (2016). Single-cell triple omics sequencing reveals genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinomas. Cell Res.26, 304–319. 10.1038/cr.2016.23

45

Hsieh C. Y. Wen J. H. Lin S. M. Tseng T. Y. Huang J. H. Huang H. C. et al (2023). scDrug: from single-cell RNA-seq to drug response prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J.21, 150–157. 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.11.055

46

Hu Y. Huang K. An Q. Du G. Hu G. Xue J. et al (2016). Simultaneous profiling of transcriptome and DNA methylome from a single cell. Genome Biol.17, 88. 10.1186/s13059-016-0950-z

47

Izzo F. Myers R. M. Ganesan S. Mekerishvili L. Kottapalli S. Prieto T. et al (2024). Mapping genotypes to chromatin accessibility profiles in single cells. Nature629, 1149–1157. 10.1038/s41586-024-07388-y

48

Jaitin D. A. Weiner A. Yofe I. Lara-Astiaso D. Keren-Shaul H. David E. et al (2016). Dissecting immune circuits by linking CRISPR-pooled screens with single-cell RNA-seq. Cell167, 1883–1896. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.039

49

Jin C. Yang L. Xie M. Lin C. Merkurjev D. Yang J. C. et al (2014). Chem-seq permits identification of genomic targets of drugs against androgen receptor regulation selected by functional phenotypic screens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.111, 9235–9240. 10.1073/pnas.1404303111

50

Jonker A. H. O'Connor D. Cavaller-Bellaubi M. Fetro C. Gogou M. 't Hoen P. A. C. et al (2024). Drug repurposing for rare: progress and opportunities for the rare disease community. Front. Med. (Lausanne)11, 1352803. 10.3389/fmed.2024.1352803

51

Kallberg J. Xiao W. Van Assche D. Baret J. C. Taly V. (2022). Frontiers in single cell analysis: multimodal technologies and their clinical perspectives. Lab. Chip22, 2403–2422. 10.1039/d2lc00220e

52

Kanemaru K. Cranley J. Muraro D. Miranda A. M. A. Ho S. Y. Wilbrey-Clark A. et al (2023). Spatially resolved multiomics of human cardiac niches. Nature619, 801–810. 10.1038/s41586-023-06311-1

53

Kartha V. K. Duarte F. M. Hu Y. Ma S. Chew J. G. Lareau C. A. et al (2022). Functional inference of gene regulation using single-cell multi-omics. Cell Genom2, 100166. 10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100166

54

Kawaoka J. Lomvardas S. (2024). LiMCA: hi-C gets an RNA twist. Nat. Methods21, 934–935. 10.1038/s41592-024-02205-w

55

Kaya-Okur H. S. Wu S. J. Codomo C. A. Pledger E. S. Bryson T. D. Henikoff J. G. et al (2019). CUT&Tag for efficient epigenomic profiling of small samples and single cells. Nat. Commun.10, 1930. 10.1038/s41467-019-09982-5

56

Kp Jayatunga M. Ayers M. Bruens L. Jayanth D. Meier C. (2024). How successful are AI-discovered drugs in clinical trials? A first analysis and emerging lessons. Drug Discov. Today29, 104009. 10.1016/j.drudis.2024.104009

57

Lambo S. Trinh D. L. Ries R. E. Jin D. Setiadi A. Ng M. et al (2023). A longitudinal single-cell atlas of treatment response in pediatric AML. Cancer Cell41, 2117–2135.e12. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.10.008

58

Lim J. Park C. Kim M. Kim H. Kim J. Lee D. S. (2024). Advances in single-cell omics and multiomics for high-resolution molecular profiling. Exp. Mol. Med.56, 515–526. 10.1038/s12276-024-01186-2

59

Lin J. Xue X. Wang Y. Zhou Y. Wu J. Xie H. et al (2023). scNanoCOOL-seq: a long-read single-cell sequencing method for multi-omics profiling within individual cells. Cell Res.33, 879–882. 10.1038/s41422-023-00873-5

60

Liscovitch-Brauer N. Montalbano A. Deng J. Méndez-Mancilla A. Wessels H. H. Moss N. G. et al (2021). Profiling the genetic determinants of chromatin accessibility with scalable single-cell CRISPR screens. Nat. Biotechnol.39, 1270–1277. 10.1038/s41587-021-00902-x

61

Liu H. Zeng Q. Zhou J. Bartlett A. Wang B. A. Berube P. et al (2023). Single-cell DNA methylome and 3D multi-omic atlas of the adult mouse brain. bioRxiv, 536509. 10.1101/2023.04.16.536509

62

Liu L. Liu C. Quintero A. Wu L. Yuan Y. Wang M. et al (2019). Deconvolution of single-cell multi-omics layers reveals regulatory heterogeneity. Nat. Commun.10, 470. 10.1038/s41467-018-08205-7

63

Liu Y. Hu B. Fu C. Chen X. (2010). DCDB: drug combination database. Bioinformatics26, 587–588. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp697

64

Lochs S. J. A. van der Weide R. H. de Luca K. L. Korthout T. van Beek R. E. Kimura H. et al (2024). Combinatorial single-cell profiling of major chromatin types with MAbID. Nat. Methods21, 72–82. 10.1038/s41592-023-02090-9

65

Loscher W. Klitgaard H. Twyman R. E. Schmidt D. (2013). New avenues for anti-epileptic drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.12, 757–776. 10.1038/nrd4126

66

Ma S. Zhang B. LaFave L. M. Earl A. S. Chiang Z. Hu Y. et al (2020). Chromatin potential identified by shared single-cell profiling of RNA and chromatin. Cell183, 1103–1116. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.056

67

Macaulay I. C. Haerty W. Kumar P. Li Y. I. Hu T. X. Teng M. J. et al (2015). G&T-seq: parallel sequencing of single-cell genomes and transcriptomes. Nat. Methods12, 519–522. 10.1038/nmeth.3370

68

Macaulay I. C. Ponting C. P. Voet T. (2017). Single-cell multiomics: multiple measurements from single cells. Trends Genet.33, 155–168. 10.1016/j.tig.2016.12.003

69

Markodimitraki C. M. Rang F. J. Rooijers K. de Vries S. S. Chialastri A. de Luca K. L. et al (2020). Simultaneous quantification of protein-DNA interactions and transcriptomes in single cells with scDam&T-seq. Nat. Protoc.15, 1922–1953. 10.1038/s41596-020-0314-8

70

McFaline-Figueroa J. L. Srivatsan S. Hill A. J. Gasperini M. Jackson D. L. Saunders L. et al (2024). Multiplex single-cell chemical genomics reveals the kinase dependence of the response to targeted therapy. Cell Genom4, 100487. 10.1016/j.xgen.2023.100487

71

Meers M. P. Llagas G. Janssens D. H. Codomo C. A. Henikoff S. (2022). Multifactorial profiling of epigenetic landscapes at single-cell resolution using MulTI-Tag. Nat. Biotechnol.41, 708–716. 10.1038/s41587-022-01522-9

72

Mimitou E. P. Lareau C. A. Chen K. Y. Zorzetto-Fernandes A. L. Hao Y. Takeshima Y. et al (2021). Scalable, multimodal profiling of chromatin accessibility, gene expression and protein levels in single cells. Nat. Biotechnol.39, 1246–1258. 10.1038/s41587-021-00927-2

73

Mitra S. Malik R. Wong W. Rahman A. Hartemink A. J. Pritykin Y. et al (2024). Single-cell multi-ome regression models identify functional and disease-associated enhancers and enable chromatin potential analysis. Nat. Genet.56, 627–636. 10.1038/s41588-024-01689-8

74

Mousavikhamene Z. Sykora D. J. Mrksich M. Bagheri N. (2021). Morphological features of single cells enable accurate automated classification of cancer from non-cancer cell lines. Sci. Rep.11, 24375. 10.1038/s41598-021-03813-8

75

Nassar S. F. Raddassi K. Wu T. (2021). Single-cell multiomics analysis for drug discovery. Metabolites11, 729. 10.3390/metabo11110729

76

Neefjes J. Gurova K. Sarthy J. Szabo G. Henikoff S. (2024). Chromatin as an old and new anticancer target. Trends Cancer10, 696–707. 10.1016/j.trecan.2024.05.005

77

Ogbeide S. Giannese F. Mincarelli L. Macaulay I. C. (2022). Into the multiverse: advances in single-cell multiomic profiling. Trends Genet.38, 831–843. 10.1016/j.tig.2022.03.015

78

Pang Z. Schafroth M. A. Ogasawara D. Wang Y. Nudell V. Lal N. K. et al (2022). In situ identification of cellular drug targets in mammalian tissue. Cell185, 1793–1805.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.040

79

Parikh A. R. Leshchiner I. Elagina L. Goyal L. Levovitz C. Siravegna G. et al (2019). Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting acquired resistance and tumor heterogeneity in gastrointestinal cancers. Nat. Med.25, 1415–1421. 10.1038/s41591-019-0561-9

80

Paul S. M. Mytelka D. S. Dunwiddie C. T. Persinger C. C. Munos B. H. Lindborg S. R. et al (2010). How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry's grand challenge. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.9, 203–214. 10.1038/nrd3078

81

Peterson V. M. Zhang K. X. Kumar N. Wong J. Li L. Wilson D. C. et al (2017). Multiplexed quantification of proteins and transcripts in single cells. Nat. Biotechnol.35, 936–939. 10.1038/nbt.3973

82

Pierce S. E. Granja J. M. Greenleaf W. J. (2021). High-throughput single-cell chromatin accessibility CRISPR screens enable unbiased identification of regulatory networks in cancer. Nat. Commun.12, 2969. 10.1038/s41467-021-23213-w

83

Prasad K. Kumar V. (2021). Artificial intelligence-driven drug repurposing and structural biology for SARS-CoV-2. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov.2, 100042. 10.1016/j.crphar.2021.100042

84

Qi J. Sun H. Zhang Y. Wang Z. Xun Z. Li Z. et al (2022). Single-cell and spatial analysis reveal interaction of FAP(+) fibroblasts and SPP1(+) macrophages in colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun.13, 1742. 10.1038/s41467-022-29366-6

85

Rodriguez R. Krishnan Y. (2023). The chemistry of next-generation sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol.41, 1709–1715. 10.1038/s41587-023-01986-3

86

Rodriguez R. Miller K. M. (2014). Unravelling the genomic targets of small molecules using high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet.15, 783–796. 10.1038/nrg3796

87

Rodriguez-Meira A. Buck G. Clark S. A. Povinelli B. J. Alcolea V. Louka E. et al (2019). Unravelling intratumoral heterogeneity through high-sensitivity single-cell mutational analysis and parallel RNA sequencing. Mol. Cell73, 1292–1305. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.01.009

88

Rooijers K. Markodimitraki C. M. Rang F. J. de Vries S. S. Chialastri A. de Luca K. L. et al (2019). Simultaneous quantification of protein-DNA contacts and transcriptomes in single cells. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 766–772. 10.1038/s41587-019-0150-y

89

Rubin A. J. Parker K. R. Satpathy A. T. Qi Y. Wu B. Ong A. J. et al (2019). Coupled single-cell CRISPR screening and epigenomic profiling reveals causal gene regulatory networks. Cell176, 361–376. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.022

90

Sadybekov A. V. Katritch V. (2023). Computational approaches streamlining drug discovery. Nature616, 673–685. 10.1038/s41586-023-05905-z

91

Satam H. Joshi K. Mangrolia U. Waghoo S. Zaidi G. Rawool S. et al (2023). Next-generation sequencing technology: current trends and advancements. Biol. (Basel)12, 997. 10.3390/biology12070997

92

Satpathy A. T. Saligrama N. Buenrostro J. D. Wei Y. Wu B. Rubin A. J. et al (2018). Transcript-indexed ATAC-seq for precision immune profiling. Nat. Med.24, 580–590. 10.1038/s41591-018-0008-8

93

Sharma A. Cao E. Y. Kumar V. Zhang X. Leong H. S. Wong A. M. L. et al (2018). Longitudinal single-cell RNA sequencing of patient-derived primary cells reveals drug-induced infidelity in stem cell hierarchy. Nat. Commun.9, 4931. 10.1038/s41467-018-07261-3

94

Shin D. Lee W. Lee J. H. Bang D. (2019). Multiplexed single-cell RNA-seq via transient barcoding for simultaneous expression profiling of various drug perturbations. Sci. Adv.5, eaav2249. 10.1126/sciadv.aav2249

95

Slavov N. (2023). Single-cell proteomics: quantifying post-transcriptional regulation during development with mass-spectrometry. Development150, dev201492. 10.1242/dev.201492

96

Spaethling J. M. Eberwine J. H. (2013). Single-cell transcriptomics for drug target discovery. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol.13, 786–790. 10.1016/j.coph.2013.04.011

97

Srivatsan S. R. McFaline-Figueroa J. L. Ramani V. Saunders L. Cao J. Packer J. et al (2020). Massively multiplex chemical transcriptomics at single-cell resolution. Science367, 45–51. 10.1126/science.aax6234

98

Stoeckius M. Hafemeister C. Stephenson W. Houck-Loomis B. Chattopadhyay P. K. Swerdlow H. et al (2017). Simultaneous epitope and transcriptome measurement in single cells. Nat. Methods14, 865–868. 10.1038/nmeth.4380

99

Stuart T. Hao S. Zhang B. Mekerishvili L. Landau D. A. Maniatis S. et al (2022). Nanobody-tethered transposition enables multifactorial chromatin profiling at single-cell resolution. Nat. Biotechnol.41, 806–812. 10.1038/s41587-022-01588-5

100

Su M. Xiao Y. Ma J. Tang Y. Tian B. Zhang Y. et al (2019). Circular RNAs in Cancer: emerging functions in hallmarks, stemness, resistance and roles as potential biomarkers. Mol. Cancer18, 90. 10.1186/s12943-019-1002-6

101

Sun D. Gao W. Hu H. Zhou S. (2022). Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it?Acta Pharm. Sin. B12, 3049–3062. 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.002

102

Swanson E. Lord C. Reading J. Heubeck A. T. Genge P. C. Thomson Z. et al (2021). Simultaneous trimodal single-cell measurement of transcripts, epitopes, and chromatin accessibility using TEA-seq. Elife10, e63632. 10.7554/eLife.63632

103

Tedesco M. Giannese F. Lazarević D. Giansanti V. Rosano D. Monzani S. et al (2022). Chromatin Velocity reveals epigenetic dynamics by single-cell profiling of heterochromatin and euchromatin. Nat. Biotechnol.40, 235–244. 10.1038/s41587-021-01031-1

104

Tietscher S. Wagner J. Anzeneder T. Langwieder C. Rees M. Sobottka B. et al (2023). A comprehensive single-cell map of T cell exhaustion-associated immune environments in human breast cancer. Nat. Commun.14, 98. 10.1038/s41467-022-35238-w

105

Tyler D. S. Vappiani J. Cañeque T. Lam E. Y. N. Ward A. Gilan O. et al (2017). Click chemistry enables preclinical evaluation of targeted epigenetic therapies. Science356, 1397–1401. 10.1126/science.aal2066

106

Vandereyken K. Sifrim A. Thienpont B. Voet T. (2023). Methods and applications for single-cell and spatial multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Genet.24, 494–515. 10.1038/s41576-023-00580-2

107

Vegvari A. Rodriguez J. E. Zubarev R. A. (2022). Single-cell chemical proteomics (SCCP) interrogates the timing and heterogeneity of cancer cell commitment to death. Anal. Chem.94, 9261–9269. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c00413

108

Wang Q. Xiong H. Ai S. Yu X. Liu Y. Zhang J. et al (2019). CoBATCH for high-throughput single-cell epigenomic profiling. Mol. Cell76, 206–216. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.015

109

Wang Y. Yuan P. Yan Z. Yang M. Huo Y. Nie Y. et al (2021). Single-cell multiomics sequencing reveals the functional regulatory landscape of early embryos. Nat. Commun.12, 1247. 10.1038/s41467-021-21409-8

110

Woloszyk A. Wolint P. Becker A. S. Boss A. Fath W. Tian Y. et al (2019). Novel multimodal MRI and MicroCT imaging approach to quantify angiogenesis and 3D vascular architecture of biomaterials. Sci. Rep.9, 19474. 10.1038/s41598-019-55411-4

111

Xie Y. Zhu C. Wang Z. Tastemel M. Chang L. Li Y. E. et al (2023). Droplet-based single-cell joint profiling of histone modifications and transcriptomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.30, 1428–1433. 10.1038/s41594-023-01060-1

112

Xing Q. R. Farran C. A. E. Zeng Y. Y. Yi Y. Warrier T. Gautam P. et al (2020). Parallel bimodal single-cell sequencing of transcriptome and chromatin accessibility. Genome Res.30, 1027–1039. 10.1101/gr.257840.119

113

Xiong H. Luo Y. Wang Q. Yu X. He A. (2021). Single-cell joint detection of chromatin occupancy and transcriptome enables higher-dimensional epigenomic reconstructions. Nat. Methods18, 652–660. 10.1038/s41592-021-01129-z

114

Xiong H. Wang Q. Li C. C. He A. (2024). Single-cell joint profiling of multiple epigenetic proteins and gene transcription. Sci. Adv.10, eadi3664. 10.1126/sciadv.adi3664

115

Xu W. Yang W. Zhang Y. Chen Y. Hong N. Zhang Q. et al (2022). ISSAAC-seq enables sensitive and flexible multimodal profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in single cells. Nat. Methods19, 1243–1249. 10.1038/s41592-022-01601-4

116

Yang X. Kui L. Tang M. Li D. Wei K. Chen W. et al (2020). High-throughput transcriptome profiling in drug and biomarker discovery. Front. Genet.11, 19. 10.3389/fgene.2020.00019

117

Ye C. Ho D. J. Neri M. Yang C. Kulkarni T. Randhawa R. et al (2018). DRUG-seq for miniaturized high-throughput transcriptome profiling in drug discovery. Nat. Commun.9, 4307. 10.1038/s41467-018-06500-x

118

Yin Y. Jiang Y. Lam K. W. G. Berletch J. B. Disteche C. M. Noble W. S. et al (2019). High-throughput single-cell sequencing with linear amplification. Mol. Cell76, 676–690. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.08.002

119

Yu Z. Spiegel J. Melidis L. Hui W. W. I. Zhang X. Radzevičius A. et al (2023). Chem-map profiles drug binding to chromatin in cells. Nat. Biotechnol.41, 1265–1271. 10.1038/s41587-022-01636-0

120

Yuan Z. D. Zhu W. N. Liu K. Z. Huang Z. P. Han Y. C. (2020). Small molecule epigenetic modulators in pure chemical cell fate conversion. Stem Cells Int.2020, 8890917. 10.1155/2020/8890917

121

Zachariadis V. Cheng H. Andrews N. Enge M. (2020). A highly scalable method for joint whole-genome sequencing and gene-expression profiling of single cells. Mol. Cell80, 541–553. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.09.025

122

Zhang Y. Li W. Laurent T. Ding S. (2012). Small molecules, big roles -- the chemical manipulation of stem cell fate and somatic cell reprogramming. J. Cell Sci.125, 5609–5620. 10.1242/jcs.096032

123

Zhou Y. Zhang Y. Zhao D. Yu X. Shen X. Zhou Y. et al (2024). TTD: therapeutic Target Database describing target druggability information. Nucleic Acids Res.52, D1465–D1477. 10.1093/nar/gkad751

124

Zhu C. Yu M. Huang H. Juric I. Abnousi A. Hu R. et al (2019). An ultra high-throughput method for single-cell joint analysis of open chromatin and transcriptome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.26, 1063–1070. 10.1038/s41594-019-0323-x

125

Zhu C. Zhang Y. Li Y. E. Lucero J. Behrens M. M. Ren B. (2021). Joint profiling of histone modifications and transcriptome in single cells from mouse brain. Nat. Methods18, 283–292. 10.1038/s41592-021-01060-3

Summary

Keywords

sc-multiomics, drug research and development, small molecule, drug-chromatin interaction, drug response

Citation

Ma J, Dong C, He A and Xiong H (2024) Single-cell multiomics: a new frontier in drug research and development. Front. Drug Discov. 4:1474331. doi: 10.3389/fddsv.2024.1474331

Received

01 August 2024

Accepted

07 October 2024

Published

22 October 2024

Volume

4 - 2024

Edited by

Linheng Li, Stowers Institute for Medical Research, United States

Reviewed by

Xu Ma, University of California, Santa Barbara, United States

Bing Liu, Chinese PLA General Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Ma, Dong, He and Xiong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haiqing Xiong, xionghaiqing@ihcams.ac.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.