- Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, College of Social Sciences and Humanities, Woldia University, Woldia, Ethiopia

The study explores the relationships between geological formations, socio-political dynamics, and urbanization processes in Woldia Township, Ethiopia, focusing on their impact on urban development and environmental sustainability through a historical lens. Woldia's early settlement and growth were hindered by challenging geographical conditions, including rugged terrain, dense forests, swampy landscapes, and security concerns. A pivotal moment in its development was the relocation of administrative and military functions to the Gebrael hilltop by Ras Ali I. This strategic decision highlights the importance of site selection, with security and visibility being key factors in historical urban planning. The study examines how economic activities, such as marketplace development and Woldia's role as a caravan break-of-bulk center, spurred its emergence as a commercial hub. Using a qualitative approach, historical records were analyzed to uncover socio-political decisions, infrastructural advancements, and environmental changes that have influenced the township over time. The findings illustrate the interplay between geographical features and socio-economic factors in shaping urban growth. The study also contrasts growth patterns under various political regimes and evaluates the ecological consequences of settlement practices. Woldia's rugged terrain, volcanic ridges, and drainage systems significantly influenced settlement geometry and infrastructure, reflecting broader urban morphology themes. While Ras Ali I's relocation facilitated commercial growth, it also disrupted native vegetation, such as Acacia and Juniper, exposing the ecological costs of urbanization. The research underscores the need to integrate historical, cultural, and environmental insights into sustainable urban planning. By prioritizing ecological preservation alongside development, Woldia can balance growth with heritage conservation and environmental resilience, serving as a model for similar contexts.

1 Introduction

The origin and growth of urban areas have long been a subject of scholarly discourse, with the observation that “studying urban areas is a vast and never-ending enterprise” (LeGates, 2016, p. 5). While large-scale urbanization is a relatively recent phenomenon, dating back roughly a century, evidence suggests that human settlements in cities began around 5,500 years ago in Sumer, Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). However, this narrative is contested, with some scholars arguing that cities may have emerged even earlier (Beall and Fox, 2009; Sjoberg, 1965). This underscores that the history of urbanization is not a recent development but a deeply rooted process.

The debate over when to define the beginning of a city's history and the criteria distinguishing a city from a non-city remains a central topic in urban studies. Sjoberg (1965) and others have argued that the emergence of cities marked a revolutionary turning point—the beginning of civilization and the foundation for modern urban societies (Redfield and Singer, 1969). The first cities appeared around 5,500 B.C. in the fertile plains of Mesopotamia and the Indus and Nile valleys. These city-based cultures have profoundly shaped human history, contributing to the steady expansion of urban populations worldwide (Beall and Fox, 2009; LeGates, 2016; Pacione, 2009; Fox, 2012).

Historically, cities have served as artifacts of civilized life, often viewed as a microcosm of society itself. Before the Industrial Revolution, cities evolved primarily through developments in military, trade, and political relations, which were beyond the capacity of rural settings (Dattagupta, 2017; Pacione, 2009; Sjoberg, 1965). While urbanization in developed nations has been closely linked to industrialization and economic growth (Mumford, 1961; Tacoli et al., 2015; Fox, 2012), the process in Africa and other developing regions differs markedly.

Urbanization in developed nations, particularly in North America and Europe, has historically been closely tied to industrialization and economic growth (Mumford, 1961; Tacoli et al., 2015). In contrast, the trajectory of African urbanization does not replicate this pattern. A key distinction in the urbanization of developing nations lies in its detachment from industrial expansion and the higher standards of living that typically accompanied urban growth in industrialized countries (Arn, 1996; Rayfield, 1974). In Africa, rapid urban ward migration often outpaces modernization, exacerbating poverty, unemployment, and social tensions, such as inter-ethnic conflict, to a greater extent than seen in Western urban centers (Rayfield, 1974; Fox, 2012). Urban Africa's transformation can be broadly understood across three historical phases: pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial periods (Chirikure, 2020).

Pre-colonial African cities, often termed pre-industrial (Childe, 1950; Sjoberg, 1965), developed as political, religious, military, and trade hubs largely independent of external influence (Rakodi, 1997). These urban centers were typically organized around kinship-based structures and local governance, and their economies were sustained through trade within their hinterlands (McCall, 1971; Winters, 1983). Cities such as Timbuktu and Kano thrived at commercial crossroads, with religious and political institutions coexisting alongside markets and craft centers (Coquery-vidrovitch, 1991). Socially homogeneous, these cities reflected a shared cultural and socioeconomic identity among inhabitants (Rayfield, 1974; Winters, 1983). In East Africa, coastal cities like Zanzibar and Mombasa bore significant Islamic influence, a legacy more mixed in regions like Sudan and the Sahel (Winters, 1983).

During colonial rule, African cities were established and developed primarily to serve the economic and strategic interests of colonial powers (Rayfield, 1974). Urbanization was structured around resource extraction economies and transport systems oriented toward export markets (Obudho, 1993). Cities such as Mombasa, Dar es Salaam, and Kampala emerged as seaports and administrative centers, while others grew to support industrial, mining, and commercial activities (McCall, 1971). The character of colonial urbanization was shaped by restrictive land policies, limited African urban mobility, and the exclusion of indigenous populations from key economic and administrative roles (Rakodi, 1997). Nonetheless, colonial cities later became focal points for nationalist movements and anti-colonial struggles, eventually culminating in the independence of African nations in the 1960s (Simon, 1989).

Following independence, African cities experienced rapid urban growth, though the structural legacies of colonialism persisted (Rayfield, 1974; Rakodi, 1997). While political leadership transitioned to indigenous elites, economic power often remained externally controlled. The spatial and economic organization of cities, such as in Kenya, continued to reflect colonial frameworks rather than traditional African settlement patterns. Despite generally low levels of urbanization, the post-colonial era saw significant increases in urban populations, accompanied by the proliferation of informal settlements (Obudho, 1993). Informality in African cities, with its deep historical roots, has been shaped by factors such as weak public housing provision, inadequate land administration, and socio-political histories of exclusion (Rakodi, 1997; Myers, 2011). Cities like Cape Town and Accra exemplify how these informal dynamics are mediated by histories of race, segregation, and belonging.

In Ethiopia, urbanization has a unique history. Ethiopian towns' causes of urban origin vary based on their primary functions and historical roles. Ancient cities like Axum, Lalibela, and Gondar are among the few historical urban centers still in existence. Many towns before the twentieth century were ruined due to geological, political, and economic factors (National Urban Planning Institute, 1997). Axum emerged as a major urban center due to its role in commerce, administration, and culture, serving as an ancient trade hub and religious capital (UN-Habitat, 1996). Harar was established as a fortified town and Islamic center. Adama developed as a transportation and communication center because of its location along important road networks (Benti, 2016). Until the establishment of Addis Ababa in 1886, most Ethiopian towns served as transient capitals or trading hubs for goods such as slaves, gold, and ivory (Horvath, 1970). The spread of the Shoan rule under Emperor Menelik II in the late nineteenth century led to the establishment of garrison towns with both political and military functions, spurring the development of urban centers in southern Ethiopia (Horvath, 1970; Benti, 2016).

The construction of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway in 1917 provided further impetus for urban growth, as towns developed around railway stations, including Dire Dawa (Horvath, 1970). Urbanization accelerated during the Italian occupation (1936–1941), despite the wartime destruction. In the post-occupation period, particularly from the late 1940s through the 1960s, Ethiopian towns experienced unprecedented growth and modernization, marking the twentieth century as a transformative era for urbanization in the country (Horvath, 1970; Sarnessa, 1966).

Ethiopia's urbanization process, though distinct, reflects broader trends in urban1 development shaped by geological, historical, economic, and political forces. The role of geology in this context is critical, as the physical landscape directly influenced the location and growth of settlements. For example, settlements were often established on fertile soils or near vital resources like water, but the geological characteristics of the land, including susceptibility to natural hazards and soil stability, significantly impacted their sustainability (Carter et al., 2021; Goudie, 2018). The evolving interaction between geological factors and urban development in Ethiopia underscores the complex and varied nature of urbanization across different regions and periods.

Woldia's urban development is distinguished by the convergence of garrison, market, and administrative functions, setting it apart from other towns with similarly strategic locations in North Wollo. Despite previous research addressing certain aspects of urban growth and spatial expansion in Woldia (Baye et al., 2020, 2023; Fasigo et al., 2024), a comprehensive analysis that integrates both geological, political, and historical perspectives on the town's urbanization remains absent. This study seeks to fill that gap by investigating the interrelationship between geological formations, socio-political dynamics, and urbanization processes in Woldia, Ethiopia, through a historical lens. The research aims to illuminate the combined influence of geological and historical factors on current urban development trends and environmental sustainability.

A central objective of the study is to examine the geological characteristics and landforms of Woldia and to assess how these have shaped historical settlement patterns and urban growth trajectories. This includes an in-depth analysis of urban development across distinct political regimes: the pre-Italian occupation period (before 1936), the Italian occupation (1936–1941), the Haile Selassie regime (1941–1974), the Derg era (1974–1991), and the post-1991 period. Tracing the town's historical evolution, the research offers insights that inform contemporary urban planning and environmental management strategies.

In addition to geological and historical inquiries, the study evaluates the socio-political and economic factors that have influenced urban development in Woldia over time. In doing so, it contributes not only to the academic literature but also to practical applications in the fields of urban policy and sustainable development.

Given Woldia's strategic function as a “nodal town” within Ethiopia's national transportation network, this study also investigates the implications of nodality on urban development in the Ethiopian highlands. It explores how Woldia's role as a transportation hub has either facilitated or constrained its socio-economic and spatial development when compared to non-nodal towns in similar geographic contexts (Mayer, 1954; Sindbæk, 2009). Key questions addressed include: How has Woldia's nodal status amplified or restricted its urban development? and In what ways does Woldia's historical growth pattern—characterized by linear expansion along trade and transport corridors—differ from that of non-nodal towns with comparable geographies? By positioning Woldia as a prototypical nodal town, the research sheds light on broader themes of urban connectivity, mobility, and spatial configuration in the Ethiopian highlands.

Ultimately, this study offers significant contributions to both scholarly inquiry and urban planning practice. It provides evidence-based insights that can support strategic policymaking, guide sustainable resource management, and enhance urban planning frameworks in Woldia and comparable urban centers across Ethiopia.

1.1 Contemporary debates in post-colonial urban studies

Post-colonial urban studies engage with various contemporary debates that question prevailing narratives and practices in urban theory and governance. A significant focus is on challenging the predominance of Euro-American urban theory, which frequently depicts cities in the Global South as marginal or underdeveloped (Robinson, 2013). Researchers advocate for formulating theoretical frameworks grounded in the realities of “ordinary cities” and the Global South, emphasizing the necessity for context-specific approaches (Roy, 2009). Another critical discussion pertains to the enduring colonial legacies within urban environments, wherein colonial-era infrastructures, segregation, and governance practices persist in influencing spatial inequalities and access to urban services (Prakash, 2010). The topic of urban informality is also central to these discussions, with informal settlements, street economies, and adaptive governance strategies contesting conventional urban planning frameworks. Some experts perceive informality as indicative of state planning failures, whereas others suggest it embodies a flexible and intentional governance model that frequently marginalizes certain groups (Roy, 2009; Simone, 2004). Additionally, the emergence of neoliberal urbanism and 'world-class city' paradigms has incited concerns regarding gentrification, displacement, and the perpetuation of historical exclusions through market-driven governance strategies (Söderström, 2013). Furthermore, discussions on environmental justice intersect with these topics, revealing how marginalized populations disproportionately bear the impacts of environmental hazards and displacement under the guise of sustainability initiatives (Angelo and Wachsmuth, 2020).

2 Methods and materials

This study employed a qualitative research approach, integrating document review, key informant interviews, and focus group discussions (FGDs) to examine the urbanization process through historical lenses in the case of Woldia Township, Ethiopia. These complementary methods ensured a comprehensive understanding of the township's historical and contemporary urban development.

2.1 Document review

A systematic review of primary and secondary documents formed the foundation of this research. Historical records, government reports, urban planning documents, academic publications, and archival materials were examined to trace the evolution of Woldia's urbanization. These documents provided critical insights into the socio-economic, political, and spatial dynamics that have shaped the township over time.

2.2 Key informant interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted to gain in-depth insights from individuals with extensive knowledge and expertise regarding Woldia's urbanization. Participants included four local government officials, two urban planners, 2 historians, and 1 long-time resident of the township. A purposive sampling technique was used to identify informants who could provide rich and diverse perspectives. Semi-structured interview guides were developed to explore topics such as historical events influencing urban growth, policy interventions, and socio-cultural transformations. Interviews were conducted in Amharic, recorded with the participant's consent, and later transcribed for thematic analysis.

Counter-narratives from marginalized groups, such as residents of informal settlements, can pose significant challenges to official archival records and prevailing perspectives on land use change and urban growth. Typically, archival materials and formal urban histories reflect the viewpoints of state authorities, planners, and elites, often overlooking, marginalizing, or misrepresenting the experiences of poorer, informal, and local communities. These records usually focus on planned developments, administrative decisions, and official land allocations, while neglecting the informal processes, negotiations, and daily challenges that significantly shape the urban landscape. To address these gaps and amplify marginalized voices, the author established safe spaces for discussion and employed data collection methods designed to encourage honest feedback from five informal peri-urban settlers. This approach aims to capture their experiences and insights effectively.

2.3 Focus group discussions (FGDs)

One FGD was organized to capture the collective memory and shared experiences of community members regarding Woldia's urbanization process. Participants were selected based on age, gender, and socio-economic background to ensure inclusivity and diversity of viewpoints. Besides, participants were residents with adequate information about the expansion of the town, well acquainted with the town's history, and having been employed in government administrations during Hailesellasie and Derg regimes. The focus group consisted of 6 participants, and the discussion was facilitated using a structured guide that covered topics such as historical landmarks, migration patterns, early settlements, and changes in urban infrastructure. The FGD encouraged interactive discussions, enabling participants to reflect on and validate each other's accounts. Audio recordings of the sessions were transcribed and analyzed to identify recurring themes and patterns. It was assumed that informal settlers might not express themselves freely during the FGDs, so they were excluded from these discussions but were instead involved through key informant interviews.

2.4 Data analysis

The qualitative data collected through document review, interviews, and FGD were analyzed using thematic analysis. Key themes were identified by coding the data and grouping similar ideas into broader categories. This approach facilitated the synthesis of historical narratives and contemporary perspectives, providing a nuanced understanding of Woldia's urbanization trajectory. By integrating historical and contemporary perspectives through diverse data sources, this study offers a holistic exploration of the urbanization process in Woldia Township, contributing to a deeper understanding of its developmental trajectory and implications for urban planning in Ethiopia with similar socio-cultural, and environmental contexts.

2.5 Methods for verifying the accuracy of oral histories and archival materials

To verify the accuracy of oral histories and archival materials while addressing potential biases or contradictions, the author employed a multi-method approach based on triangulation. That is, triangulation of data from multiple sources was employed to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings. This involved systematically cross-referencing oral testimonies, archival records like Sarnessa (1966), and other documentary sources to identify areas of consistency and discrepancies, thereby assessing the reliability of individual accounts.

Additionally, the study incorporated toponymic analysis, which examined place names that often preserve historical, cultural, and functional information. This offered another layer of evidence to verify or question the authenticity of historical claims. The collection of oral histories from a diverse range of informants, representing different generations and social groups, facilitated the identification of shared memories and contested recollections, highlighting the dynamics of collective memory and the potential for selective remembrance.

Chronological cross-checking was also undertaken, comparing events recalled in oral histories with verifiable historical events documented in religious and administrative texts to assess temporal consistency. By combining these complementary methods, the study navigated the complexities of historical reconstruction and the interpretation of contested pasts with care.

2.6 Ethical considerations

The study adhered to ethical research principles. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring they understood the purpose of the study and their rights, including the option to withdraw at any time. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the research process to protect participants' identities and sensitive information.

3 Geographical context

3.1 Location

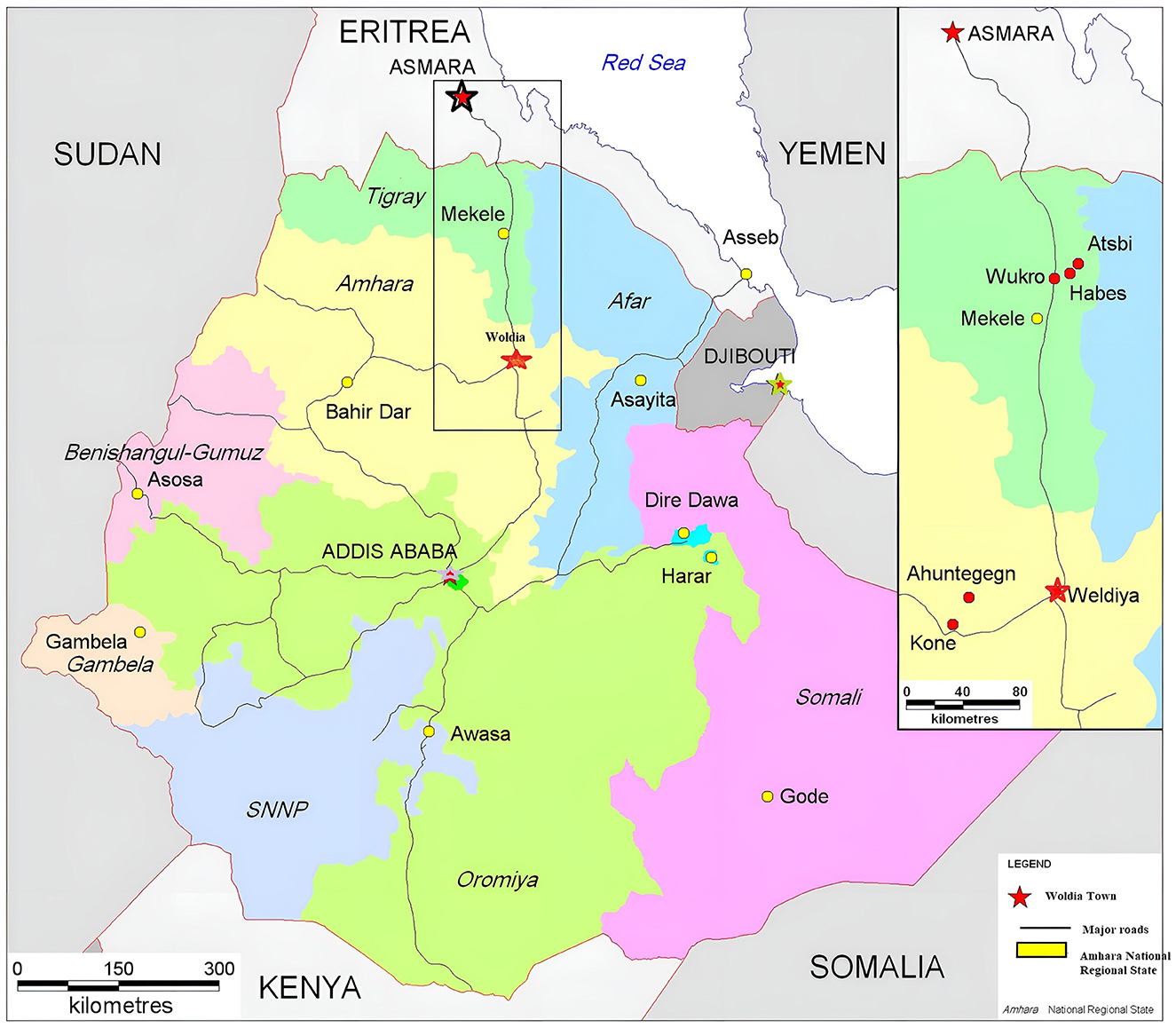

Woldia lies between 11° 48′ N−11° 50′ N latitudes and 39° 34′ E−39° 36′ E longitudes. It is the capital town of North Wollo Zone, Guba Lafto Woreda, and Woldia town Administration, and is becoming a seat of all these levels of government offices. Its name, meaning “a meeting central place”, reflects that it was serving as a place of break-of-bulk to the nearby areas (Sarnessa, 1966; Baye, 2009). It is situated on the major north-south highway that links the national capital, Addis Ababa, with Mekele in the Tigray region. The town is located at a distance of about 521 km from the national capital, Addis Ababa; 360 km from the regional capital, Bahir Dar; and about 180 Km from the tourist attraction site of Lalibela.

The area under study is, geographically, situated in the northwestern highlands and associated lowlands, and in the subdivision of the north-central massifs, having an average altitude of 2,000 m above mean sea level.

According to the Amhara National Regional Bureau of Finance and Economic Development, Woldia Town has an estimated population of 93,349. Approximately 70% of the population is under 30 years of age, indicating a predominantly youthful demographic structure. Women represent 52% of the population, while men account for 48%. The town has experienced a significant average annual population growth rate of 3.23% between 2007 and 2017.

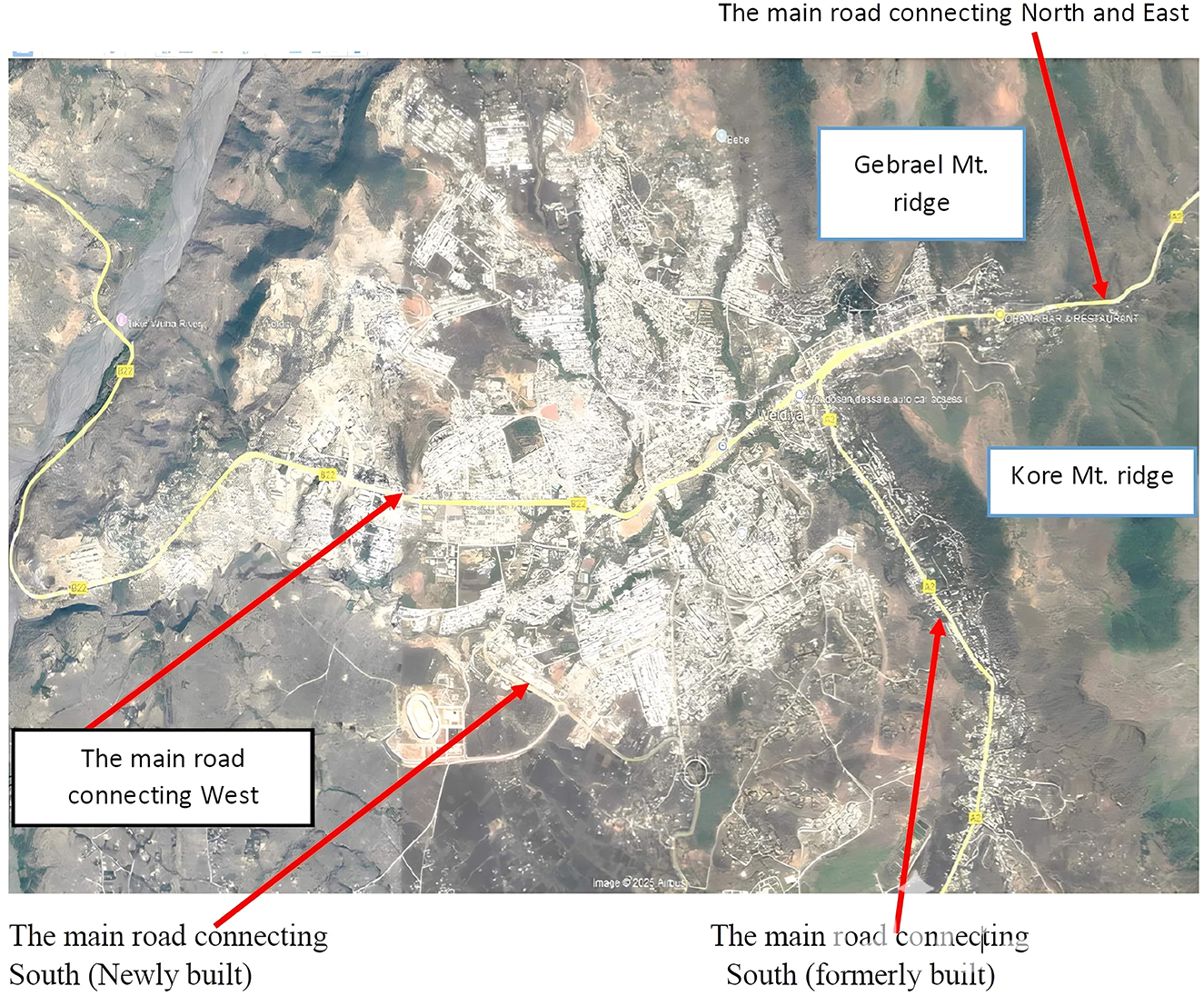

Woldia is a strategically significant town located in northern Ethiopia, positioned at the intersection of three major highways: the Addis Ababa–Dessie–Woldia route, the Bahir Dar–Gonder–Woldia corridor, and the Mekele–Woldia highway (see Figure 1). These highways not only connect Woldia to other major urban centers across the country but also provide efficient access for commuters and goods to the town center. Serving as a critical junction, Woldia links Mekele in the north and Djibouti in the east, while intersecting with the Addis Ababa–Dessie highway in the south and the Bahir Dar–Gonder route in the west. Furthermore, Woldia acts as a primary gateway to Lalibela, one of Ethiopia's most significant religious and cultural destinations.

Figure 1. A general map of Ethiopia with Woldia's location (Adapted from Morrissey, 2011, P. ix, and 131).

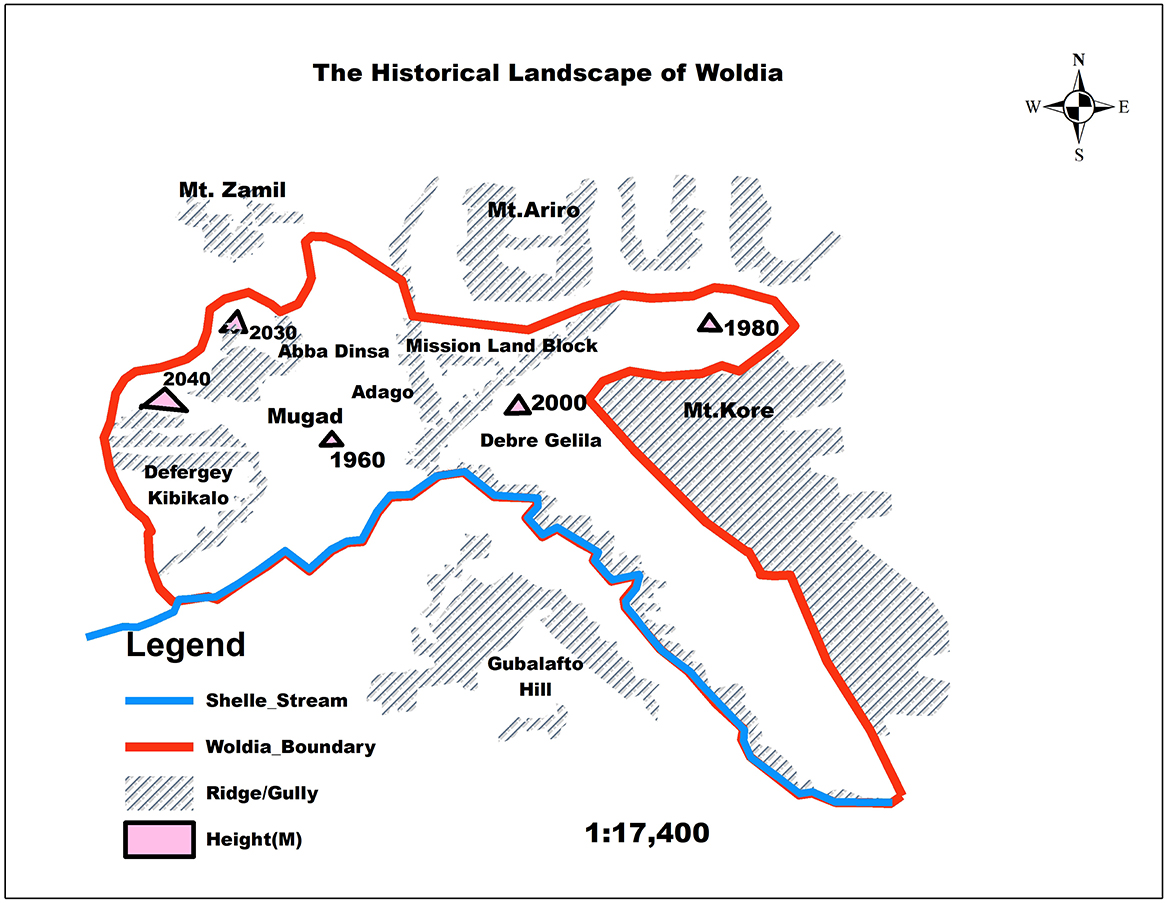

Mount Gubarja/Kore flanks the town in the east, and Mount Gebrael/Ariro in the north. It is because of these topographic constraints that the town is experiencing rapid growth toward the south, northwest, and west. To the west of Woldia lies the flat plain of Mechare, which is the alternative area for further expansion extending to Tikur Wuha and Melka Demo rivers (Baye, 2009).

There is no large river passing through Woldia, although the Shelle Stream crosses it from north to southwest, which is streaming from Gebrael Mountain and Sedeboru plain close to Woldia University. To the south of Woldia lies part of the flat plain of Mechare and the small escarpment of Gubalafto, for further expansion until it is also limited by the small mountain, which is locally called Guba Terara- meaning Mount Guba. That is why the initial growth of the town was distorted to linear geometry. At the moment, when one sees Woldia aerially, it takes the shape of a hollow, and the town is expanding almost in a compacted geometry. The morphology of the town is the form, the structure, and the layout of the town.

The expansion of the town to the south is influenced by several factors, despite the physical constraint posed by the small escarpment of Gubalafto. The most significant factor driving this development is the few kilometers highway that connects Jeneto Ber to Woldia via Gubalafto (see Figure 2). This critical infrastructure not only facilitates connectivity but also stimulates urban growth in the region.

The flat and level terrain of Mechare provides an additional advantage for expansion. Moreover, the establishment of key institutions and infrastructure, such as Woldia University, the Sheik Mohammed Hussein Al Amoudi International Stadium, Woldia College of Teachers' Education, and Woldia Polytechnic College, has greatly accelerated the town's development. The construction of major highways, including the Jeneto-Woldia route and the Woldia-Gondar-Bahirdar highway, further supports this growth by enhancing accessibility and mobility.

Economic activities in the town have also seen significant growth. The development of a designated industrial zone, coupled with an increase in investment opportunities and the annual rise in the number of businesses, highlights the town's potential as a commercial hub. Additionally, financial institutions are actively supporting investment initiatives in the area, providing access to urban loans and other financial services, which further contribute to the town's economic development.

Despite these advancements, there is untapped potential in several key sectors. Enhanced investment in tourism, hospitality, transportation, commerce, and agriculture is essential to fully realize the town's development aspirations. A more integrated and strategic focus on these sectors will ensure sustainable growth and broaden the town's economic base.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Results

4.1.1 Topographic and geological characteristics of Woldia

Woldia, as documented by Sarnessa (1966), Baye (2009), and the Woldia Structural Plan (2009), is strategically located on the Ethiopian plateau, just west of the Main Ethiopian Rift Valley. Framed by the Gabriel Mountain chain to the north and the Kore Mountain chain to the east, Woldia's location underscores its historical and geographical significance as a crossroads for ancient human migrations and ecological transitions. The town's unique position highlights the interplay between geological forces and human adaptation over millennia.

4.1.2 Geological features shaping Woldia's urban growth and morphology

The geological nature of Woldia and its surrounding landscape significantly influences its urban growth and development, shaping its morphology, expansion patterns, and settlement geometry. The dissected landscape of Woldia and its surroundings is a product of intense volcanic activity and other geological processes, which have shaped its diverse topographic features (Willians, 2016). The surrounding areas are characterized by a striking alternation of mountains, ridges, hills, plains, and gently inclined surfaces. These features are not merely natural; they reflect a long history of interaction between the land and its inhabitants, who adapted their practices to the challenging terrain.

The elevated ridges and higher grounds, composed predominantly of Tertiary basalts of varying ages and compositions, bear testament to the volcanic origins of the area. The deep gorges and dissected valleys—hallmarks of tectonic and erosional forces—also served as natural pathways or barriers, influencing ancient traveling patterns and settlement distributions (Willians, 2016). Over time, this rugged relief became both a challenge and an opportunity for human societies, shaping agricultural practices, trade routes, and urban planning.

The geological nature of Woldia and its surroundings significantly shapes its urban growth and development, influencing its form, structure, and layout. To the south of the town lies the flat plain of Mechare, which initially provided a conducive area for urban expansion due to its accessibility and suitability for construction. Further growth in the north and north east direction is constrained by the mountainous terrain of Gebrael and Kore (Gubarja), which act as natural barriers. These limitations forced the town's early development into a linear geometry, as expansion was restricted to narrow, accessible corridors along the plains. Over time, as linear growth became less feasible due to geographical constraints, Woldia's urban form shifted toward a compact geometry, with development concentrating in the limited available space. Aerially, the town now resembles a hollow structure, reflecting this densification and spatial containment. The overall morphology of Woldia—its form, structure, and layout—is a direct response to the surrounding geological features. While flat areas allow for relatively organized and structured growth, the presence of escarpments and mountains creates irregular boundaries, shaping the urban landscape into a mix of planned and organic patterns. This compact growth and constrained layout necessitate careful urban planning to ensure efficient use of space and sustainable development amidst these natural limitations.

4.1.3 Drainage system and hydrological influence

The drainage system of Woldia is intricately tied to its geological structures and slope orientation. Surface water from various directions converges into the Shelle River, which flows northwestward to join the Tikur Wuha River. This drainage pattern, predominantly parallel, not only reflects the underlying geological and topographic influences but also highlights the role of water in shaping human-environment interactions.

4.1.4 Soil erosion and land degradation

Soil erosion and land degradation are interlinked processes that have long-lasting impacts on both natural landscapes and human settlements. These processes often result from the combined effects of geological and climatic factors, as well as human activities, leading to the removal of topsoil, loss of vegetation cover, and the creation of deeply dissected land surfaces. In Woldia, soil erosion and land degradation are particularly prevalent, posing significant challenges to urban development, infrastructure, and environmental sustainability.

The gorges and degraded land in Woldia represent a significant disruption to the natural biome and urban landscape. These changes not only threaten local ecosystems by reducing biodiversity and altering hydrological cycles but also create barriers to infrastructure development. Roads, buildings, and other urban projects face heightened risks due to unstable ground conditions and the progressive expansion of eroded areas.

4.2 History

4.2.1 Foundation and development of Woldia

While the explicit case of the pattern and trend of spatial growth of Woldia will be made later, it is necessary to now introduce the establishment and early development of the town.

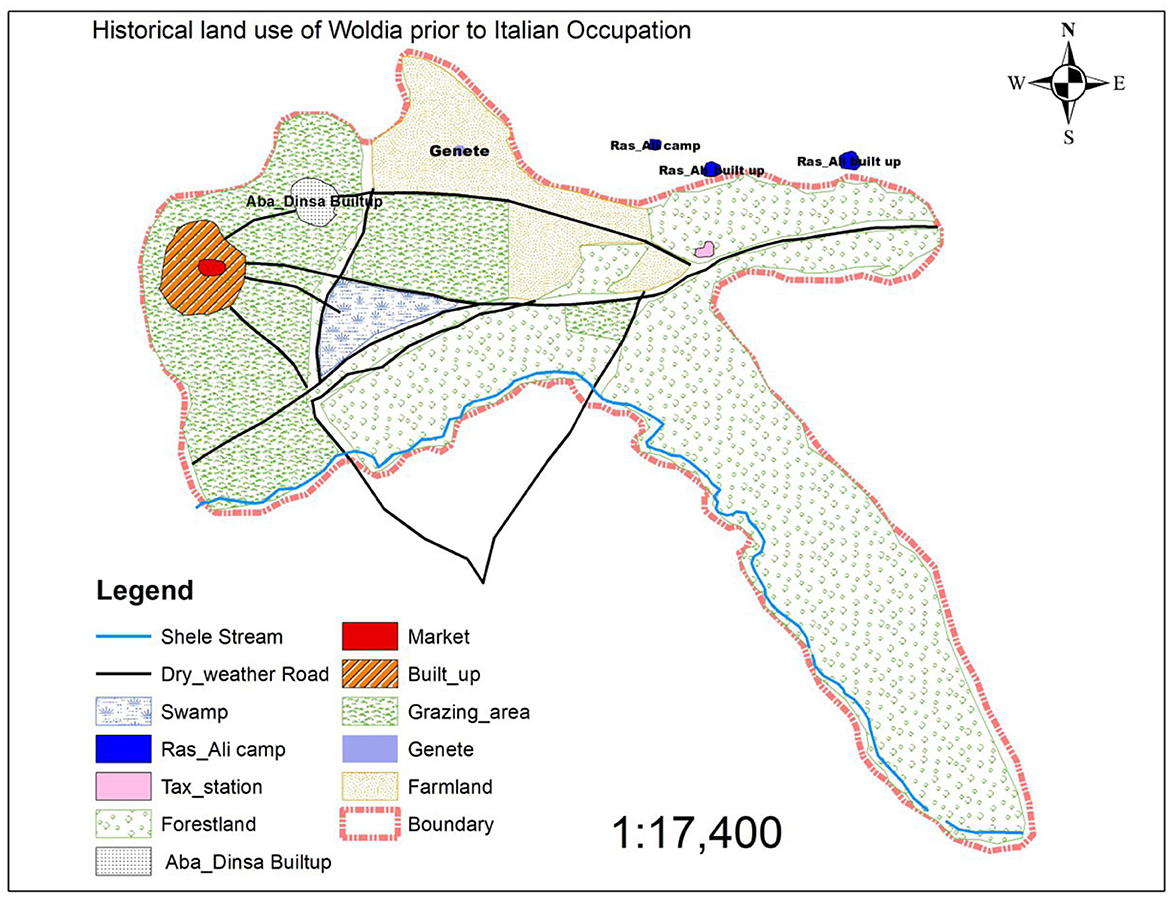

As per the data obtained from the various sources, before the foundation of Woldia, both the area in which Woldia was built and the surrounding areas were covered with thick forests and thorny bushes of indigenous origin of Acacia, Cactus, Olive tree, Juniper, and many more species. There were various types of wild animals sheltered inside these thick forests and thorny bushes including Hyena, Leopard, Gazelle, etc. As a consequence of the existence of thick and thorny forests and due to its swampy nature, the area was hardly occupied by people. For instance, due to its flatness and lower altitude than Adago and Abba Dinsa, Mugad was a marshy area until the occupation of the Italians who drained it. Besides, except for the only built-up areas of Defergay-Islam-Kebele and Abba Dinsa hillock, the rest were unoccupied until the Italian occupation (Sarnessa, 1966). To this end, there were no permanent settlements in other areas for a long period because of its inhospitable environment and due to security reasons.

The transformation of Woldia's landscape from dense forests and swamps to built-up areas highlights the significant role of early settlers in shaping contemporary biomes. Human activities, such as clearing forests and draining swamps for settlement and agriculture, not only altered the local ecosystem but also led to habitat loss for native species like hyenas, leopards, and gazelles. The disruption of native vegetation underscores the loss of biodiversity associated with urbanization. These historical interactions between humans and the environment demonstrate how migration and land-use practices have long-lasting effects on ecosystems. Understanding these processes provides valuable insights for addressing contemporary challenges in biodiversity conservation, sustainable land management, and balancing urban development with ecological preservation.

Nevertheless, it does not mean that there was a complete absence of people. In addition to the original settlers in and around Woldia, there were Oromo pastoralists who settled in the surrounding area of present-day Woldia, where local Oromiffa terms are still in use in and around the town: Guba Lafto, Abba Mana, Mechare, Kibikalu, Abba Dinsa, Melka Kole, Melka Demo, Karahatu, etc. As the structural plan document of Woldia (Woldia town structural plan, 2009) discloses, these people were pastoralist and were not as submissive to the authority of the then Yeju rules. Consequently, they constantly rebelled against the existing political order.

Historically, Woldia was built at the hilltop of Gebrael by Ali I as the site itself was conducive to access to defense. It also arose as administrative (defensive) and commercial foci of the surrounding areas, as well as far distant areas such as Illubabor, Keffa, and Shewa (Sarnessa, 1966). This implies that Woldia came to be embellished as a center of commerce or garrison, or the seat of the then-ruler Ali the Great (Ali I). Ali, I founded Woldia by shifting the settlement from Wedo to the hilltop of Gebrael, due to the area's geographic characteristics. To this effect, Ali I is credited for the founding of Woldia. The exact date of the first settlement is uncertain, but Woldia was established sometime between 1784 and 1788 (1777 E.C−1781 E.C) as the break-of-bulk point where the transportation necessarily changes (Sarnessa, 1966; Baye, 2009). In general, the foundation and history of Woldia are principally attached to the following two fundamental reasons: Administrative and security reasons, and Caravan trade reasons. The reign of Talaku Ali, also called Ali the Great in Woldia, was from 1784 to 1788 (Mekuria, 2013, p. 290).

The town's administrative role began sometime between 1784 and 1788 when Ali I transferred the seat from Wedo (sometimes named Woidu) to the top of Mount Gebrael (Baye, 2009). Woldia, as an urban center, had emerged as a fortress and military garrison to serve the needs of the then-provincial chieftain, Ali the Great, at least 100 years before the emergence of Addis Ababa in 1886 as the permanent capital. According to Mekuria (2013), when Atse Tekle Giorgis imposed a tax upon his ruled people, the people gathered together and requested the king to withdraw his tax imposition. But, Atse Teklegiorgis refused the request of the people. The people secretly gathered together and appointed Ali the Great as Ras: a ruler equivalent to the prime minister of Great Britain of that day, and had a royal family as a figurehead. During this time, Ras Ali I (Talaku Ali meant Ali the Great) was the ruler of Lasta, Wadla, Delanta, and Yeju (Sarnessa, 1966; Baye, 2009). Ras Ali gladly accepted and rebelled against the then king Atse Teklegiorgis of Gonder. As a result, Ali fled from Gonder and descended to reside in Yeju, camping at the top of one of the mountains that surrounded the present Woldia town (see Figure 3), as other rulers of the time did because it was customary for Ethiopian rulers to camp on Ambas, meaning mountain tops.

Figure 3. Historical land use of Woldia prior to the Italian occupation (Adapted from: Sarnessa, 1966).

Ras Ali I is said to have chosen this site because it was a mountaintop and strategically important for military and administrative purposes. In the meantime, Ras Ali wanted to consolidate his economic and military base at Yeju, and to this effect, he stationed himself at the top of Mount Gebrael that bounds Woldia to the north. On top of this mountain, he built the Gebrael church, which is one of the churches he constructed in his territories during his ruling period. In line with this historical fact, Yirgalem (2008, p. 69) explained that “for security and religious purposes, Ethiopians usually locate their settlements on the high ground. As a symbol of reflection, churches in Ethiopia are built on higher ground while settlements occupy the lower ground”.

The second reason was associated with the trade and commerce-caravan trade. While Ras Ali settled at the top of Mount Gebrael, the marketplace was at Woidu (sometimes called Wodo), some 20–25 km south of Woldia. For security reasons, Ras Ali the Great relocated the marketplace from Woidu to Jenete [genete], just a few kilometers to the west of the foot of Mount Gebrael over which he camped. For this reason, Woldia was sometimes previously known as Genete. However, this selected place was a marshy area, which was prohibited from marketing practices during rainy days, and Ras Ali I was unable to control and command the people, as it was not visible from the top of the mountain (Baye, 2009).

Thus, ultimately, as per the data obtained from unpublished documents, ker informants and oral histories, due to these two factors, unable to control and command the people he administered, Ras Ali I relocated the marketplace from the Jenete/Genete/to the present marketplace at Deferge area, namely Maksegno Gebeya, between 1784 and 1788, to the site of the present market area. The marketplace was formerly named “Awaji Mengeria”, which meant a place at which government messages were disseminated to its governed people during market days by government representatives. They called the attention of the people in the market via the loud sound of a drum.

It was probably during its establishment that Woldia became a commercial town. In this period, there was a gradual development of trade and commerce. Merchants came from Begemidir and Gojam, bringing butter and honey, and on their way back they used to take salt bars (Amole; Sarnessa, 1966) and still play an important role in commerce today. Woldia, as a caravan gate as well as a fledgling marketplace, proved to be an economically significant place to the Yeju authorities. However, trade between far places was in a challenging situation because the formation of Woldia and the development of the marketplace took place during the time of regional rulers (Zemene Mesafints). Hence, the absence of authorities permanently in the area, who at times made their administrative seat at Begemidir/Debre-Tabor/, harmed the security situation of Woldia and its environs because of the aggressive raid and looking of bandits on caravan traders.

However, as salt bars were a means of bartering and they had to be obtained at any cost, and as Yeju was a Gonderian empire, one can consider that this obstacle might be overcome, though it was risky to go to the south. Through time, the market became popular, and the caravan traders also found it a comfortable place to have a break from their tiresome journey. To that end, Woldia had served as a break-of-bulk center. In furtherance, traders also used to sell their merchandise in that market. As the market grew in volume and importance, neighborhoods like Gonder Sefer, Gojam Sefer, and Islam-Kebele were created. In these places, the merchants used to rest to feed their pack animals (Sarnessa, 1966; Woldia Town Structural Plan, 2009). To sum up, the factors governing the position of Woldia were economic/commercial and defense/administrative, and Ras Ali's camp on the top of Mount Gebrael was an attractive and defensive position rivaling the market.

4.3 Naming

There is no standard system for the transliteration (in the sense of lettering) of most Ethiopian place names. The name of the capital city of Ethiopia, for example, is spelled in at least four different ways: Addis Ababa, Addis Abeba, Adis Abeba, and Adis Abbaba (Willians, 2016, P. xxxiv). Similarly, the study area is spelled out differently by different writers: Weldeya (Sarnessa, 1966), Weldiya (Sarnessa, 1966; Willians, 2016), Woldiya (Woldia town structural plan, 2009), and Woldia (Baye, 2009; Fasigo, 2009; Willians, 2016). Throughout this paper, except for citing one's work, however, the author used the word “Woldia”, which is most familiar and used by many individuals in their writings.

Regarding the origin of the name “Woldia”, there are two main scenarios discussed in Sarnessa (1966) and Baye (2009) based on oral traditions and an unpublished document. The first is the one derived from the Amharic word “Set Wolda” and the second from the Oromiffa term “Welda”.

4.3.1 Scenario one

According to the first scenario, the name Woldia is said to have originated from the Amharic term “Set Wolda”. In this scenario, according to local accounts, when Ras Ali the Great relocated the marketplace from Jenete (or Genete) to its current location in the Deferge area, the event was marked by a significant moment. It is said that while seated at the top of Gebrael Mountain, Ras Ali observed a white object on a hillock in the Deferge-Islam Kebele, an occurrence that influenced his decision to move the marketplace. Ali the Great, then, sent his Balemuals-literally, loyalists to identify what that white matter was. When the loyalists arrived there, they found a woman with a baby waiting for her clothes (Shema) to dry after washing. In due course, after returning to the camp at Gebrael, they told Ras Ali the great as “Set Wolda”, meaning a woman who has given birth to a child. After that, gradually, the place gained the name Woldia from the Amharic term “Set Wolda” through time. This is the first story as to how the name Woldia has evolved and consigned.

4.3.2 Scenario two

In addition to the first scenario, the second scenario is associated with the origin of the name to Oromiffa's term “Welda”. In this regard, after Ras Ali the Great changed the marketplace from Jenete (Genete), just a few kilometers to the west of the foot of Mount Gebrael to the present marketplace at Deferge area, namely Maksegno Gebeya, between 1784 and 1788, he then named it “Welda”. To this end, the term Woldia is believed to be derived from the Oromiffa term “Welda” meaning a central meeting place for all. As noted above, Woldia served as a break-of-bulk center for nearby small towns and far-distance places. Hence, Woldia was started as some sort of meeting place- likely a marketplace-around 1784 and 1788 during the reign of Ras Ali the Great and got its name during that time. Since then, the word “Welda” has been modified with time to Woldia and has been used till now.

The name derived from “Welda”, the second scenario, is mostly agreed upon and accepted due to the following reasons:

1) “Welda” bears a meaningful relation to Woldia,

2) The historical background supports the name means that:

2.1 The camp place and Woldia are intervisible,

2.2 The area is rocky and not muddy, as Jenete, and

2.3 The word “Welda” is an Oromo term meaning a meeting central place (Shengo), and the founder, Ras Ali the Great, was also an Oromo (Sarnessa, 1966, p. 20).

4.4 History of urban spatial restructuring of Woldia

Here, by urban spatial restructuring refers to the pattern and trends of spatial growth of Woldia throughout different regimes. As the political and economic environment has changed, so has the physical structure of Woldia. The evolution of Woldia's urban spatial structure since the founding time can be divided into five periods: Pre-Italian occupation (prior 1936), the time of Italian occupation (1936–1941), the Haile Selassie regime after Italian occupation (1942–1974), the Derg period (1974–1991) and finally the post-Derg to the present period, and these are described chronologically in these periods.

4.4.1 Urban development through different regimes

The development of Woldia as an urban center has been shaped by various historical, political, and socio-economic factors during different regimes in Ethiopia. Each regime brought unique policies, priorities, and challenges that influenced the town's physical expansion and urban form.

4.4.1.1 Woldia during the pre-Italian occupation

From the previous discussion, it is possible to remark that whatever the reasons were, the connection of Ras Ali the Great to the evolution and development of Woldia, in general, is a reality. Though it is difficult to tell the exact year when Ras Ali the Great founded Woldia, it is also possible to tell that the town was established sometime between 1784 and 1788. During this time, it is believed that the center of Woldia was set in today's Maksegno Gebeya at Deferge Kebele.

Throughout the early settlement in Woldia, having given an order to the people, Ras Ali divided the area into two sections: the early 100 “gebbars” (tax-payers) of Ras Ali who settled around Deferge-Islam Kebele and the fifty “gebbars” (tax-payers) of Abba Dinsa hillock settlers. Plots of land were given to 150 “gebbars” (tax-payers). This area was the place where the horses of the ruling circles were groomed and trained (Sarnessa, 1966, p. 20; Baye, 2009, p. 38). Yet, as far as their urban morphology, as well as housing typology, is concerned, the early settlements were more of a rural type.

Settlements grew slowly during the years following its foundations from tiny hamlets; its sizes were limited to Deferge-Islam Kebele and Abba Dinsa hillocks. The areas to the east, north, south, and west of it were unoccupied. At that time, for example, the southern part of Adago or the area south of Mugad, such as the current Melka Kole School, was densely forested and was the shelter of hyenas and other animals, whereas the northern part was agricultural land. The eastern zone, known today as Debre Gelila, in the past as Lafto and Abba Maana, was partly farmland, marshy, and forested areas.

Figure 4 depicts Debre Gelila in Woldia during that time, showcasing a distinct geographical or spatial configuration that resembles the shape of a standing man with arms extended forward. The two arms represent the extensions of the town while the rest of the body indicates the area to the west of the sharp bend, including the then road. This unique formation not only reflects the natural landscape of the area but also provides an interesting perspective on how the physical terrain might have influenced the cultural or symbolic interpretation of the region's topography. The southeastern part of Debre Gelila, which is known as Tinfaz, is the narrow arm-like extension of the foot of Kore Mountain on the west. The area gently slopes in the southwest direction to the Shelle stream (Sarnessa, 1966).

Figure 4. The historical landscape of Woldia in 1966 (Adapted from: Sarnessa, 1966).

Part of the Itege Taitu Bitul school compound and the then-mission land block (today's hospital area and the surroundings) were swampy and home to mosquitoes. The Mission land block of Woldia at that time (the Zonal specialized referral hospital of today) was a triangulated-shaped plot of land, separated from Adago by Aba Nigusse stream (now it dried up) and from Debre Gelila by Nitaf Dingay stream. The southern boundary was the confluence of these two streams, nowadays Woldia Health Center.

The rest, all the plain areas, were farmlands except the valley between Ariro and Kore Mountain, which was densely forested with a path in the middle. That is, within the then boundary of Woldia, the only built-up areas were Deferge-Islam Kebele and Abba Dinsa hillocks, while the rest was unoccupied until the Italian occupation. It meant that Woldia remained stagnant in settlement expansion till the Italian occupation, even though there was a sign of growth during the reign of Atse Yohannes and a very slight growth during the reign of Menelik II (Sarnessa, 1966).

It was during the time of Atse Yohannes that a taxation station was established at a place (today piazza), which was about 3 km to the east of Woldia of the time, and directed the growth of the town eastward. However, as the taxation station was only a hut in which “Negadras”, equivalent to the present Mayor of a town, worked during the day, it did not transform Woldia either in size or plan.

However, with the expansion of the Ethiopian kingdom, during the reign of Menelik II, trade was promoted. For example, Woldia and Mekele, Merchants, took Amole (Salt Bars) as far as Addis Ababa, Jima, Nekemte, Gonder, and Gojam. On their way back, they used to bring coffee from Jima and Nekemte, and butter, honey, hides, and skins from Begemider and Gojam (Sarnessa, 1966). Consequently, Woldia became both a lodging place and a famous market. To meet the needs of traders, some drinking houses were set up.

4.4.1.2 Woldia during the Italian occupation (1936–1941)

During the short-lived Italian occupation, Woldia functioned mainly as a military garrison and as an administrative center. The Italian period was very important for its growth in several ways because it was during the Italian occupation that all-weather roads, different governmental institutions such as the then Awraja Gizat, Awraja court, Awraja finance, Woreda court, Coptic offices, and what are now called Debre Gelila, Adago, and Mugad were built, and commercial business began on a large extent (Sarnessa, 1966). The introduction of motorized transportation also stimulated commercial activities in and around Woldia, which in turn affected the urban expansion of the town.

As per Sarnessa (1966) and other FGD informants, the first weather road was made when His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I passed to Maychew to fight the Italians. But all-weather roads joining Woldia to the Northern or Southern regions were constructed by the Italians. While the Italians did not focus heavily on urbanizing Woldia specifically, their efforts in the broader area helped improve connectivity, which later facilitated urban growth (Tronvoll, 2000). Soon after their arrival, the Italians made their fortress on the top of KibbiKalu hill, just to the then west of Woldia. The physical growth of the town was also powered by the construction of the residence of the commanding officer at Aste Yalew, the then junction of the road from Woldia, and the path from Lafto or Mekerecha (taxation station) in the east. After staying at Aste Yalew, the residence of the officer was changed to Defergay, which was within the then boundary of the town, Woldia. However, with the transfer and substitution of the officer, the new officer, Major Foglia, built his residence at Abba Manna by the Addis Ababa-Asmara road of that time. This, in turn, caused the physical expansion of the town eastward, though this also marks the beginning of the limitation of the eastward growth of Woldia.

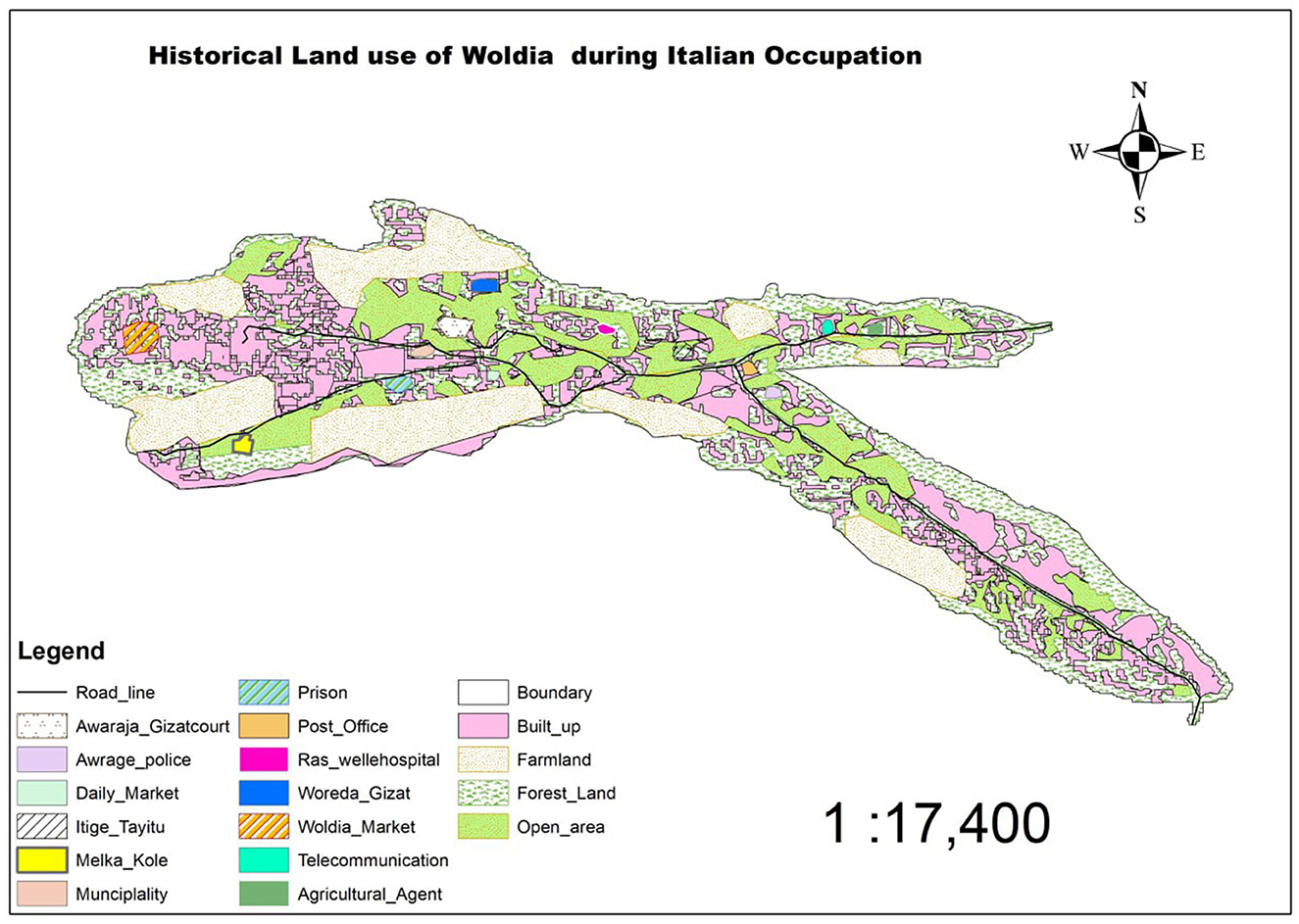

The governor of the day, Major Foglia, saw the improvements of urban networks as an important means of acquiring power over the town to play an important role as a stronghold in the area. The contribution of Major Foglia was very important for the growth of Woldia in several ways because it was during the Italian occupation, during his rule, that an astonishing growth of the town was observed than the growth of the town before. During this time, Woldia grew to about four times its previous size within five years, which had previously remained stagnant for almost 150 years. That is why Major Foglia was considered the founder of modern Woldia (Sarnessa, 1966). Interview with key informants confirms that the development of these gave impetus to the growth of Woldia, which attracted the construction of workers and later small service firms and domestic workers supporting the new suburb's middle-income class residents and government offices. Figure 5 illustrates the historical land use patterns of Woldia during this period, highlighting how different sections of the town were allocated for various functions, such as residential, commercial, administrative, and public service activities. This depiction offers insights into the spatial organization and urban development priorities that shaped the town's growth and functionality at the time.

Figure 5. Woldia land use during the Italian occupation (Adapted from: Sarnessa, 1966).

Moreover, the road constructed from Addis Ababa to Woldia and other places solved some of the transportation problems associated with the traditional method of trading to a greater extent and the town served as a break of the bulk center for distributing goods and services; it has long been a center of trade and commerce. On the evolution of infrastructures and their roles, an elderly Female Participant stated that:

“I remember when there were only dirt roads in Woldia. Over time, paved roads and new schools, institutions, and health stations have been built, which has made life easier for many. However, these developments were mostly concentrated in the center of town. Peripheral areas struggled with poor infrastructure and lack of basic services.”

What has been established by Atse Yohannes, Foglia continued the Mekerecha (taxation station) as a controlling station or a place at which all goods passing by were examined. As a result, the place which had been Lafto and later named as Mekerecha was named as Commanda Tabba-literally means Command station. In addition to these, various facilities such as lodgings, drinking houses, restaurants, storehouses, garages, and many dwelling houses, clinics, and offices were introduced and built during the time of Italian occupation (Sarnessa, 1966). The occupants were encouraged to purchase land at a lower price, to build houses, and to live in the town.

To the west of Kore Mountain, a clinic and offices were built, and a football field and bakery were made in the area occupied by Itege Taitu Bitul School today. These were not the only things that Major Foglia contributed to Woldia. He marked out the boundaries of Woldia in 1938. It is his demarcation that was officially accepted and recognized by the government of that time. Also, the Italians planned Woldia, built a school and clinics, made running water available, and caused the growth of the town.

Before the Italian occupation, selling “injera” or milk was not the culture of the people. However, the first food or “injera” selling was started when the armed forces began asking for food at a price. An interview on the role of urbanization in cultural changes is reflected via the response of key informant:

“Before the Italian occupation, it was unheard of for people to sell traditional foods like injera or milk. This practice began when armed forces demanded food in exchange for payment, introducing a cash-based economy into local cultural practices.”

During the short period between the Italians' evacuation of Ethiopia and the revival of peace and order in the country, many of the Italian-built houses were destroyed. That is, as the Italians left the town, some of the people despoiled the houses and shared out the sheets of galvanized metal that made the roofs. It is because of this that Italian-built houses were not found even in the 1960s at Debre Gelila (the then Abba Maana and Lafto) where the clinics, bakery, and residential houses were built (Sarnessa, 1966).

4.4.1.3 Woldia during Haile Selassie's regime after the Italian occupation (1941–1974)

With the restoration of Ethiopia from the short Italian occupation, more people came into the town, and more houses were built. At the time of Italian occupation, houses stood here and there, far apart. There was even part of Woldia which was not built up at all. As discussed above, Maksegno Gebeya, Abba Dinsa, and their surrounding areas were established before the Italian occupation. For instance, in the southern part of the town known as Tinfaz along the Addis Ababa-Dessie road, there were no houses. However, after the Italian occupation and their evacuations, houses were built along these directions following the main road within the boundary of the town at that time. Moreover, in the built-up areas, the houses were very close together, and in some places, they were even overcrowded. For example, part of Mugad and a small portion of Debre Gelila Piazza area, are directly overcrowded. The number of houses increased more than 10 times during the evacuation of the Italian invasion (Sarnessa, 1966).

The other major impetus factor for the slow but steady growth of Woldia was the introduction and build-up of public institutions after the Italian occupation. One of the major developments in the urban growth of Woldia during the post-Italian period was the introduction of municipal administration in the country. To this end, a municipality was established in Woldia in 1944 (Sarnessa, 1966). The municipality was not, however, strong enough to execute its responsibility because of the strong influence of the landowners. Before the nationalization of the land and houses by the Derg Regime, the land was purely under the control of feudal lords of the period, and as a result, the municipality was not in a position to effectively administer the land that was under its municipal jurisdiction.

It was in 1947 that Kidane Mihiret Church was built within Commanda Tebba. It was at this time that Commanda Tebba was given a new name, Gelila, by Dejazmach Ayalew Biru (the then-governor of Yeju Awraja). From that time onwards, the name Commanda Tebba was replaced with Debre Gelila (Sarnessa, 1966). In addition to the earlier mosque built in the old Woldia, two mosques- one in Mugad and the other in Debre Gelila- were built after the Italian occupation of Ethiopia. The government clinic, which was formerly called Mission Hospital or Ras Wole Bitul Hospital, was built after the Italian occupation by the governor of Yeju Awraja, Dejazmach Ayalew Biru.

Before the establishment of Itege Taitu Bitul School in 1948, a school named Prince Asfaw Wosen was opened in 1943 at Commanda Tebba and served the remains of Italians and sons of high government officials. Itege Taitu Bitul School was established even though the people were not willing to send their children to modern Schools. Through time and much effort, the local people took the initiative and built eight classrooms for an elementary school at Melka Kole, and a secondary school was opened in 1964. Yet, the problem of the shortage of classrooms was not solved. The first school of Woldia, Itege Taitu Bitul School, became secondary in 1964. To this end, Woldia is the second town, after Dessie, to have a secondary school in the Wollo Province of that time (Sarnessa, 1966). All these facts together indicate the slow but steady growth of Woldia after the Italian occupation through the establishment of these and other institutions. Figure 5 provides an overview of the general land use patterns in Woldia during the Haile Selassie era, illustrating how various areas of the town were designated and utilized for different purposes. This includes residential zones, commercial spaces, administrative centers, and other functional uses, reflecting the urban planning and developmental priorities of that period.

However, during Haile Selassie's reign, the absence of attractive investment alternatives led persons in possession of surplus wealth to speculate in urban real estate. This pattern of investment drove up the cost of land in urban areas dramatically and led to a situation in which a small number of wealthy individuals possessed almost all urban land. An estimate made in 1966 indicated that 5% of the population of Addis Ababa owned 95 percent of the privately owned land (Cohen and Koehn, 1977, p. 25; Kebbede and Jacob, 1985). To this end, Woldia was no exception to this situation.

Hence, during the Imperial era, urban land was privately owned, and henceforth, if one wants to use urban land without owning it, he or she needs to lease it from the property owner. As was true for, Ethiopia, the land was owned by a few people, whereas the majority of the people were landless. Cohen and Koehn (1977) while writing on these issues state that an estimated 60 percent of the occupied housing units, in Addis Ababa, were rented rather than owned by their occupants in the late 1960s. The same pattern prevailed throughout Ethiopia, generating large incomes for a few urban landlords and landowners.

In the same vein, Sarnessa (1966), while writing on this line, confirms that out of the total population of 9708 of Woldia, only 1329 were urban landowners while the remaining were landless in 1965. Hence, urban land was owned by a few individuals who leased out the service to whoever wanted to make use of it. Few property owners owned urban houses, and others, the majority, had rented the dwelling houses or buildings or even lands from the property.

4.4.1.4 Woldia during the Derg period (1974–1991)

After the overthrow of the Haile Selassie Regime in 1974, the radical reforms by the Derg (sometimes spelled as Dergue) destroyed private property ownership in the urban areas in the following period (1974–1991). The Derg era or the socialist regime (1974–1991) nationalized urban lands and extra houses and set a maximum threshold for private capital accumulation and investment (Cohen and Koehn, 1977).

As such, there appears to be general agreement on the fact that Ethiopia claims to have nationalized all land and extinguished private freehold land ownership in 1975 under the government ownership of urban lands and extra houses Proclamation No. 47/1975. Hence, the property owner remained in his or her private house, and all the extra-urban houses had been nationalized in 1975. All industries, hotels, and buildings were also nationalized along with the rural land they occupied in bulk. Accordingly, the government announced in its statement by saying that “land reform in urban areas” to “put an end to … disparity in wealth”, “urban land will have to be returned to the people in the same way that rural land was” (Cohen and Koehn, 1977; Holden and Yohannes, 2002). Cohen and Koehn (1977) write that:

“To build public support for nationalization, the new military rulers disclosed the figures revealing the extent to which private urban land ownership had become concentrated in the hands of the few in Ethiopia. For instance, on 25 July 1975, the Ethiopian Herald published statistics culled from incomplete municipal records revealing that seven members of Haile Selassie's family owned eight million square meters of land in Addis Ababa, while the heirs of a powerful aristocrat claimed 12 million square meters in the Entoto and Yeka zones of the city. The extra houses and the extensive land the loyalists and their adherents were possessing in urban settings were doomed to be dealt [with] seriously. Accordingly, Derg formerly announced a proclamation to provide for government ownership of urban land and extra Urban Houses No. 47/1975.” (p. 25)

Therefore, all urban dwellers were allowed to own one house in any municipality in Ethiopia. Any individual was granted possessory rights over a maximum of 500 square meters of urban land in any one municipality, as living quarters. Nevertheless, free transfer of the same was prohibited. Similarly, sale, mortgaging, succession, or otherwise was strictly prohibited except the right to pass the property on inheritance to one's spouse or children. Private house owners and other organizations were prohibited from renting houses or buildings. Government buildings of the imperial regime were classified as “enemy property” and were nationalized immediately. The proclamation strengthens state control over the physical development of urban areas. Moreover, it prevents individuals and families from preserving or acquiring large urban holdings and, thereby, effectively eliminates gross inequities in land distribution (Cohen and Koehn, 1977).

The nationalization of urban land and extra houses halted private investment. This had repressed, among others, urban development. To that end, spatial and physical developments were mere responses to political demands. For its effective implementation and to tighten political control, throughout the Derg regime, new and decentralized administrative units like the “Kebele” were established. Woldia was no exception to the nationalization of privately owned property, and the nationalization of urban housing and land was imminent. The political climate under the Derg was marked by repression and instability, which further stunted economic and urban growth. The regime's emphasis on ideology and state control limited private sector development, and towns like Woldia experienced little in the way of modern urban development during this time (Abbink, 1997).

The government was the only viable entity for the construction of facilities for urban services, public buildings, and homes, except for a few private investments for dwelling houses. The government started to offer land free of charge for government employees who produced evidence that they did not possess any house previously (Tufa, 2008). However, the growth of the urban areas such as Woldia continued to be stagnant. Four major reasons decelerated the growth of the urban areas: the political unrest, insecurity of urban life due to political conflicts, the nationalization of extra houses which halted the building of houses for rent, and the strict control of in-migration to cities/towns through the registration of people's movements (Tufa, 2008).

Yet, one of the salient features of the Derg era was the nationalization of urban land and extra houses that gave municipalities the upper hand to manage their resources (land) freely and effectively. Evidence of this comes from the fact that the municipality of Woldia is reported to have provided land to its people for the first time in 1978 which incentives for the expansion of the town. During this period, Woldia expanded along the main road that runs between Addis Ababa and Asmara (as Eritrea was part of Ethiopia during that time). Moreover, the construction of the Woldia-Woreta road in the early 1980s contributed to the stretching of the town's development toward the northwest and west and reshaped the morphology of Woldia. Generally, the overall government policy of the Derg Period discouraged the urbanization process of all towns, and thus, Woldia also shares this fate.

A key informant historian reflects the situation as follow:

“Woldia's growth as an urban center can be traced back to the establishment of the main trade route connecting the northern, western, and southern regions. The influx of traders and the construction of administrative offices in the mid-20th century acted as a catalyst for economic and population growth. However, the Derg regime's land nationalization policies in the 1970s caused disruptions, forcing many landowners to abandon their properties, which slowed the urbanization process temporarily.”

4.4.1.5 Woldia during the post Derg period (1991 to the present)

After the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) assumed power in 1991, following the fall of the Derg regime, a shift in land ownership policies was implemented. All land, occupied or unoccupied-was declared state property and registered in the name of the people. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia's Constitution, specifically Article 40 on property rights, reinforced this policy. Sub-article 3 states, “The right to ownership of rural and urban land, as well as of all-natural resources, is exclusively vested in the State and the peoples of Ethiopia. The land is a common property of the Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples of Ethiopia and shall not be subject to sale or other means of exchange”. Any misuse or practices contrary to the Constitution are subject to legal penalties [Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE), 1995].

During this transformative period, Woldia witnessed rapid spatial expansion. Geographical constraints, particularly mountainous barriers, limited growth to the north and east. However, expansion proceeded rapidly in all other directions. As a result, Woldia adopted a more compact urban form compared to its earlier elongated, linear shape. Historically, the growth of Woldia was predominantly influenced by major highways linking the town to Dessie and Addis Ababa, Mekele, and Bahir Dar-Gondar/Woreta. This connectivity resulted in an east-west spatial orientation, with the town's length nearly double its north-south dimensions during the Derg era. In contrast, the post-Derg period has witnessed a significant increase in road density, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The condition of the current road infrastructure in some parts of Woldia (Source: Woldia Town Asset Management Document, 2017).

This period also marked significant modernization within the town. Multi-story buildings are constructed, and urban services are expanded rapidly, resulting in improved living conditions for residents. Compared to earlier times, Woldia experienced unprecedented progress, transitioning into a multifunctional urban center serving as a hub for administration, commerce, education, healthcare, and politics.

Specifically, the growth and expansion of urban areas in Woldia have been marked by significant developments in public service facilities, housing, institutions, and administrative buildings, despite variations in quality and quantity. Public service facilities have played a crucial role in shaping the town's urban fabric. Key developments include the establishment of a public library and cultural hall, which serve as centers for education and cultural enrichment. Transportation infrastructure has also improved with the construction of a modern bus station, complementing the historical Melka Kole Old Stadium and the state-of-the-art Mohammed Hussein Ali Al-Amoudi Stadium (see Figure 7), which caters to sports and large-scale events. Public spaces, such as parks, have been developed to enhance the town's livability, while essential facilities like an abattoir and market areas provide critical services to the local economy. Improvements in water supply systems, energy infrastructure, and drainage networks have further supported the town's urban expansion by addressing basic utility needs.

Figure 7. The multipurpose Stadium of Sheik Mohammed Hussien Almoudi (Source: Woldia Town Asset Management Document, 2017).

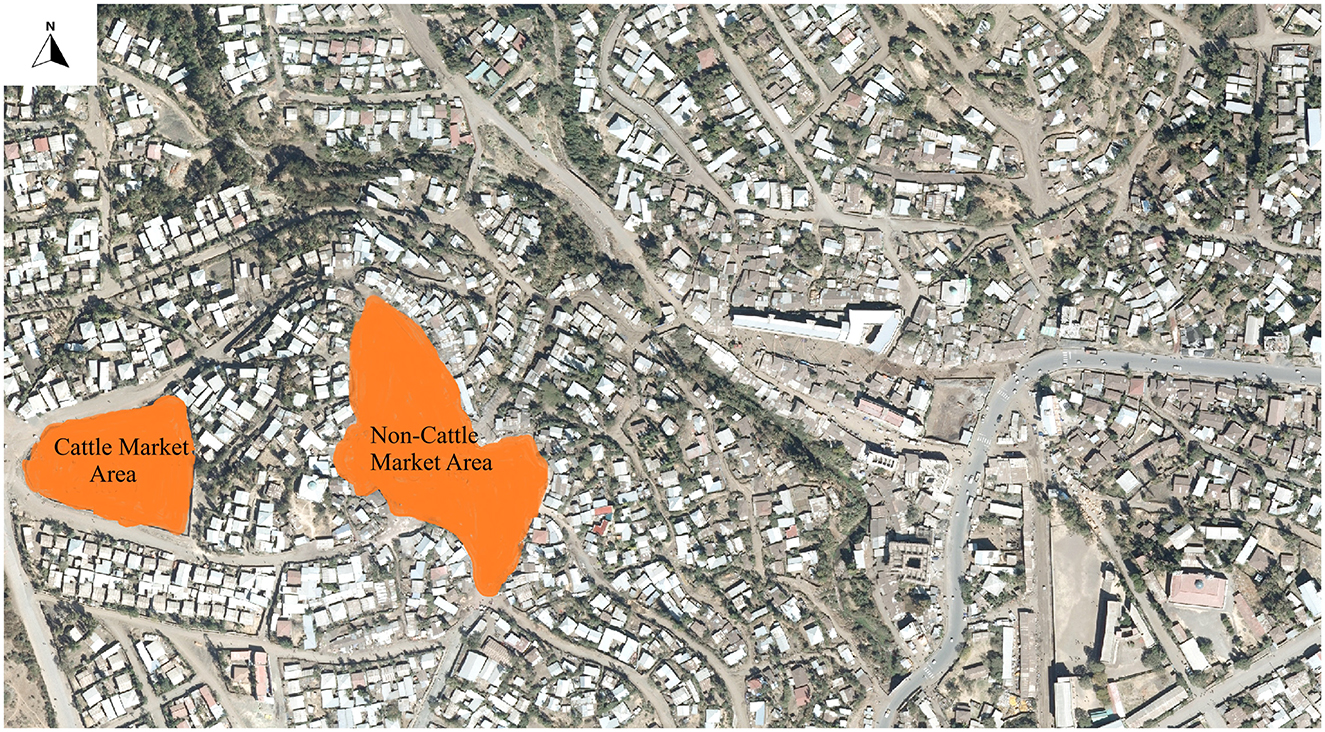

Housing development has been another pivotal aspect of Woldia's urban growth. The town has experienced growth in both commercial and residential housing, addressing the rising population and the diverse needs of its residents. The area surrounding the market became a central focus for the development of settlements, which, in turn, stimulated the expansion of the town. As the market attracted more people for trade and commerce, residential and commercial developments began to emerge in its vicinity, contributing to the overall growth and expansion of the town. This process of settlement flourishing around the market area is a key factor in the town's development and is illustrated in Figure 8. These developments range from modern apartment complexes to traditional single-family residences, reflecting the town's socio-economic diversity.

Figure 8. The location of the main market areas in Woldia (Source: Woldia Town Asset Management document, 2017).

Institutional growth has been instrumental in driving Woldia's expansion. The establishment of various educational institutions, including schools, colleges (private and government), and university, has positioned the town as a regional center for learning. Similarly, the development of healthcare facilities has significantly improved access to medical services, ensuring better health outcomes for residents and surrounding communities.

Administrative buildings have also played a critical role in Woldia's urban growth. As the town's administrative functions expanded, new government offices and public administration centers were constructed to meet the increasing demand for governance and public services. Collectively, these developments have transformed Woldia into a vibrant urban center, balancing functionality and growth, while meeting the diverse needs of its growing population.

On the other hand, in recent years, Woldia has faced several challenges related to rapid urbanization, including informal settlements, inadequate infrastructure, and environmental degradation (Baye, 2025a; Baye et al., 2020, 2023; Baye, 2025b). However, ongoing government initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable urban growth and improving local infrastructure are expected to facilitate the town's continued urbanization (Mezgebo, 2020). A key local government official informant claims the policy and governance challenges in the current period as follows:

“While urban planning policies have laid a foundation for Woldia's development, enforcement has been a challenge due to budget constraints and institutional fragmentation. For instance, the new rural-urban dichotomy intended to control informal settlements remains largely unimplemented, leading to unregulated construction and overburdened public infrastructure.”

The central area (particularly Mugad) retained much of the urban morphology originally shaped by the Italian occupation, while peripheral areas were increasingly influenced by urban sprawl and informal settlements. This expansion reflects Woldia's transition into a vibrant and dynamic urban center, driven by its strategic location, economic activities, and institutional growth.

4.5 Discussion and implications

The topographic and geological characteristics of Woldia are integral to understanding the urban development processes and challenges faced by the town, as outlined in the literature. Several sources, including Sarnessa (1966), Baye (2009), and the Woldia Structural Plan (2009), provide crucial insights into how the town's unique location has influenced both historical settlement patterns and modern urban morphology. Positioned on the Ethiopian plateau, Woldia's geographical context underscores the complex interplay of geological forces that have shaped its development over millennia. These features not only highlight the historical significance of Woldia as a crossroads for human settlement but also point to the long-standing interaction between the land and its inhabitants.

As noted by Willians (2016), the dissected landscape of Woldia, shaped by intense volcanic activity and tectonic processes, has been pivotal in determining the town's growth and morphology. The alternating ridges, hills, and plains are not merely natural formations; they embody a history of adaptation to a challenging environment. This observation aligns with broader discussions on how topographical constraints influence urban growth, as found in the work of several scholars (Willians, 2016; Mumford, 1961), who emphasize that natural features such as escarpments and hills often define the physical and spatial limits of settlement expansion. Woldia's urban growth has mirrored this relationship, with early development constrained by the geographical barriers posed by the surrounding mountainous terrain.

A key theme emerging from the literature is how these geological features—especially the volcanic ridges, basalts, and gorges—have influenced urban planning and settlement geometry in Woldia (Willians, 2016). The historical progression from linear growth to a more compact urban form reflects the direct impact of these natural barriers. As discussed in the Woldia Structural Plan (2009), urban expansion initially followed the main highways, then the flat Mechare plain to the south, but further growth was limited by the escarpment of Gubalafto and the rugged terrain of Mount Guba. This constraint is consistent with findings from other regional studies, which highlight how topographical limitations shape urban forms into compact, densely populated settlements when natural expansion is not possible (Sarnessa, 1966). Woldia's current urban form, a “hollow” structure, demonstrates the result of this limitation, as development has concentrated in available spaces, creating a mixed pattern of planned and organic growth.

The socio-economic and environmental constraints, including unoccupied swampy areas and agricultural lands, further align with prior literature on the geographical limitations affecting settlement patterns in Ethiopia. The study extends this consistency by illustrating the ecological impacts of Woldia's transformation from a natural wilderness to an urbanized area, including biodiversity loss and the replacement of indigenous vegetation by human-managed landscapes. These insights reflect established patterns of urbanization-induced environmental changes observed in similar historical contexts (Nyssen et al., 2004; Douglass et al., 2018).

The role of drainage systems, discussed by Sarnessa (1966) and Baye (2009), is another crucial aspect of Woldia's geological landscape. The convergence of surface water into the Shelle stream and its eventual flow into the Tikur Wuha River highlights the impact of the region's geological structures on water distribution and urban development. The parallel drainage patterns suggest a long-standing relationship between human settlements and natural water flows. The importance of hydrology in shaping settlement patterns is well-documented in the literature, with many studies emphasizing how watercourses determine the location of key infrastructures, such as roads, bridges, and agricultural zones (Willians, 2016). In Woldia, these natural features have likely influenced the town's growth and the development of agricultural practices in the surrounding areas.