- 1Professur für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Historisches Seminar, Universität Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

- 2Abteilung für Ur- und Frühgeschichtliche Archäologie, Historisches Seminar, Universität Münster, Münster, Germany

The paper discusses the potentials and challenges of geoarchaeological research into long-term prehistoric settlement dynamics. As an example, the study employs a dataset of 367 Bronze Age sites from the Weiße Elster river catchment in Central Germany, spanning the area between the Northern German Plain and the Central Uplands. The recorded sites are systematically processed to create a cohesive dataset with a standardized chronology, consistent classification of site types, and clear spatial delineation. A key focus is on analyzing how archaeological, geographical, and culturally intrinsic filters influence the visibility and preservation of Bronze Age sites across time and space. To investigate settlement dynamics, the study uses chronological frequency distributions, site density metrics, spatial relationships between periods, and Site Exploitation Territories (SETs). The results reveal that the basic trends in Bronze Age settlement dynamics can be identified through the dataset. However, there are limitations. Due to culturally intrinsic filters, each period is represented by a distinct combination of settlements, burials, and stray finds. The reason for this is that some periods can only be identified by artifacts made of a certain material, such as pottery or metal. This is also observed in neighboring regions, suggesting broader regional patterns. Site density analyses show that local communities in the Northern German Plain primarily settled along the Weiße Elster River during the Early Bronze Age (2150–1600 BCE) and Middle Bronze Age (1600–1300 BCE). In contrast, sites from the Transitional Period (1300–1150 BCE) show no clear settlement pattern. The Urnfield Period (1150–800 BCE), is marked by a high concentration of sites in the Northern German Plain and increased land use in the Central Uplands. SET analysis aligns with these findings, further highlighting a dominance of loess soils near Early Bronze Age settlements. Site frequencies remain relatively stable between the Early Bronze Age and Transitional Period but surge sharply during the Urnfield Period – a pattern primarily observed in adjacent study areas in the Central Uplands. Notably, both the start of the Middle Bronze Age and the Urnfield Period are characterized by a widespread abandonment of settlements and burial sites from earlier periods.

1 Introduction

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, several cornerstones were laid for systematic archaeological research into the Bronze Age in Central Germany. Shortly after Virchow (1872) had described the Lusatian culture and Rýzner (1880) the Únětice culture, Montelius (1885, 1898, 1900a,b,c) and Reinecke (1900, 1902a,b) published chronological systems for the Bronze Age in Northern and Southern Germany, thus providing researchers in Central Germany with further points of reference for archaeological dating. In addition, the introduction of archives with local area files (German: Ortsakten) and the passing of heritage protection laws enabled the long-term conservation and overview of prehistoric monuments and finds (Gummel, 1938; Schmidt, 1986; Aichinger and Grasselt, 2010; Heynowski, 2010a). Simultaneously, comprehensive catalogs and inventories of archaeological finds were published, that became important resources for the research (Götze et al., 1909; Jacob, 1911; Amende, 1922, 1928; Auerbach, 1930).

These cornerstones allowed archaeological research in the beginning 20th century to carry out large-scale and diachronic studies on early human-environment relationships in Central Germany. Hennig (1912) published a geoarchaeological dissertation in which he investigated site distribution patterns between the Neolithic and the Middle Ages with special attention to soil types (Strobel, 2009). In the following decades, this research approach was further taken up by Schlüter (1928, 1931, 1952), Schlüter and August (1959), Leipold (1934), and Schwarz (1948), who discussed prehistoric settlement dynamics with regard to the assumed distribution of open land and primeval forests (Jäger, 1973).

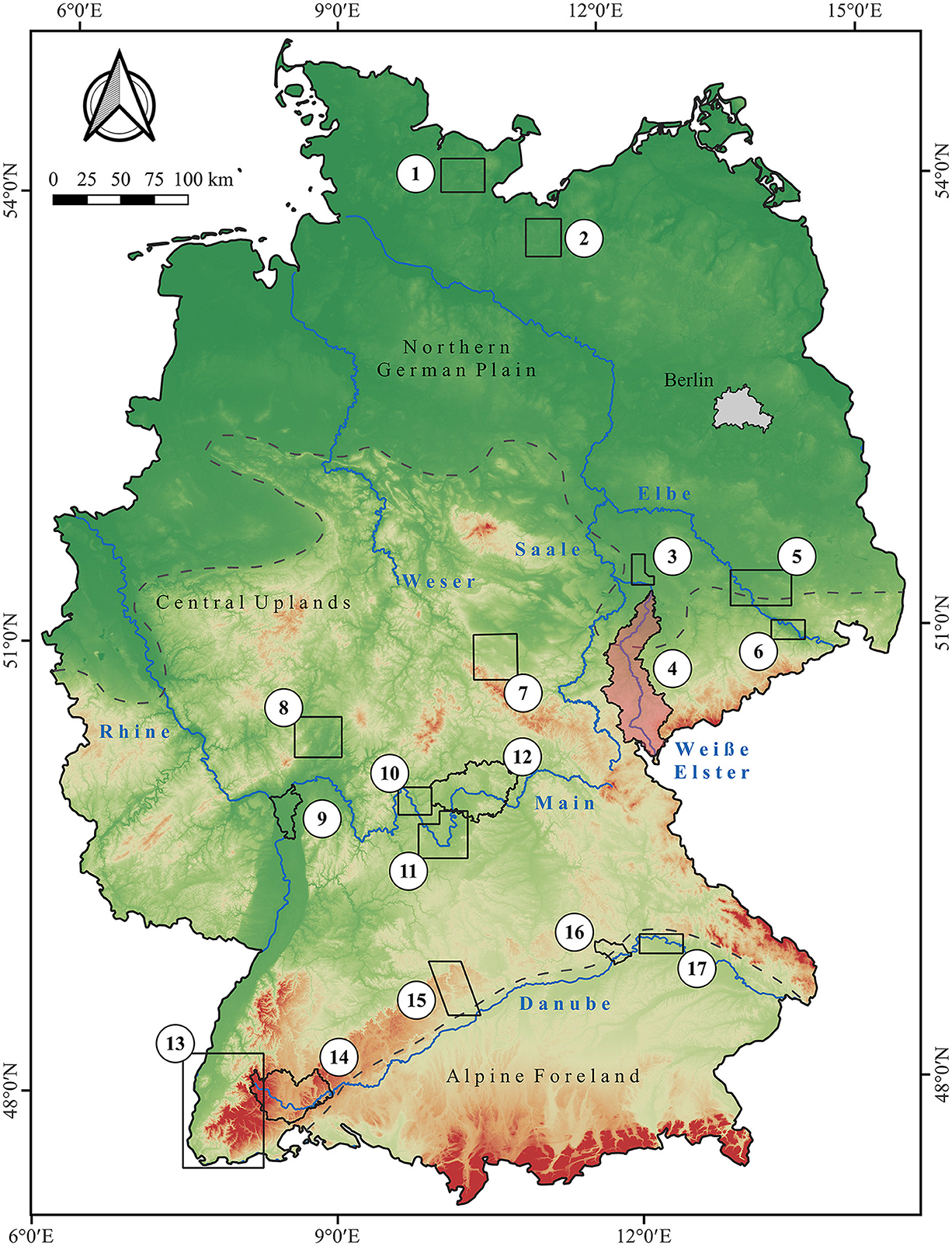

These early studies are characterized by the fact that their statements on human-environment interactions and settlement dynamics during the Bronze Age are based on individual observations and subjective impressions resulting from the examination of distribution maps (Miera, 2022). The dissertation by Müller (1980) on the prehistoric and early historical settlement of the Gothaer Land was a significant step forward in this regard: In contrast to his predecessors, he carried out a statistical analysis of the distribution of the sites using selected terrain covariates. In this way, he pioneered the long-term trend toward diachronic studies on a geostatistical basis (Figure 1). Unfortunately, Müller's approach was not taken up in the following decades (Jacob, 1982; Christl, 1989; Simon, 1991; Peschel, 1992; Hilbig, 1993; Bahn, 1996).

Figure 1. Diachronic studies with a focus on statistical analyses of long-term human-environment interactions between the Neolithic and the Middle Ages in Germany. (1) Holstein lake region (Lüth, 2012), (2) Region between Lake Schwerin and Stepenitz (Schülke, 2011), (3) north-west Saxony (Wegener, 2014), (4) Weiße Elster river catchment (this paper), (5) former district of Riesa-Großenhain (Balfanz, 2003), (6) widening of the Elbe valley at Dresden (de Vries, 2013), (7) Gotha landscape (Müller, 1980), (8) northern Wetterau (Saile, 1998), (9) district of Groß-Gerau (Gebhard, 2007), (10) north-western Main triangle (Obst, 2012), (11) southern Main triangle (Schier, 1990), (12) eastern landscape of Lower Franconia (Pfister, 2011), (13) southern Upper Rhine valley (Mischka, 2007), (14) the Baar and adjacent landscapes (Miera, 2020), (15) Brenz-Kocher valley in the eastern Swabian Jura (Pankau, 2007), (16) lower valley of the Altmühl river (Sorcan, 2011) and (17) Danube valley near Regensburg (Schier, 1985). In addition, the three main landscape units of Germany are shown. Rivers are derived from the European Catchments and Rivers network system (European Environment Agency, 2012). The topography is based on the SRTM 90 m Digital Elevation Database version 4.1 (Farr et al., 2007; Reuter et al., 2007; Jarvis et al., 2008).

It was only after the year 2000 that quantitative evaluations of prehistoric settlement dynamics were carried out again in Central Germany (Balfanz, 2003; de Vries, 2013; Wegener, 2014). However, they used different geographical data, as well as different geostatistical methods and archaeological classifications. Therefore, the current understanding of human-environment interactions and settlement dynamics in Central Germany remains a mix of subjective observations and a limited number of insights based on geostatistical analyses. As a result, their findings can only be compared to a limited extent (Miera, 2022).

This paper builds on the earlier studies mentioned above and addresses existing desiderata. The research background is provided by an interdisciplinary geoarchaeological project that investigates the interplay between the Holocene geomorphological floodplain and slope dynamics, as well as variations in prehistoric and medieval settlement dynamics and climate changes in the loess-covered catchment area of the Weiße Elster (von Suchodoletz et al., 2021, 2024; Ballasus et al., 2022; Grygar, 2022; Miera et al., 2022; Zielhofer, 2022). To this end, a comprehensive database was set up containing more than 3000 archaeological sites from the Paleolithic to the Middle Ages. Here, the Bronze Age sites are presented and discussed in detail for the first time. The aim is not only to provide a supra-regional contextualization of archaeological observations. The paper introduces a toolbox for the investigation of settlement dynamics and the implementation of source-critical analyses that can be applied to other periods and regions. The following objectives are being addressed:

• A presentation of the methodological approach for structuring and processing archaeological and geographical data for a diachronic investigation of prehistoric settlement dynamics

• A source-critical evaluation of the spatial and chronological distribution of sites, considering archaeological, geographical and culturally intrinsic filters

• An analysis of Bronze Age settlement dynamics using site densities, site distribution patterns with respect to selected terrain covariables, site frequencies and spatial affinities of individual periods

• A supra-regional discussion of the results from the Weiße Elster catchment area in the context of observations from adjacent study areas in Central Germany

2 Study area

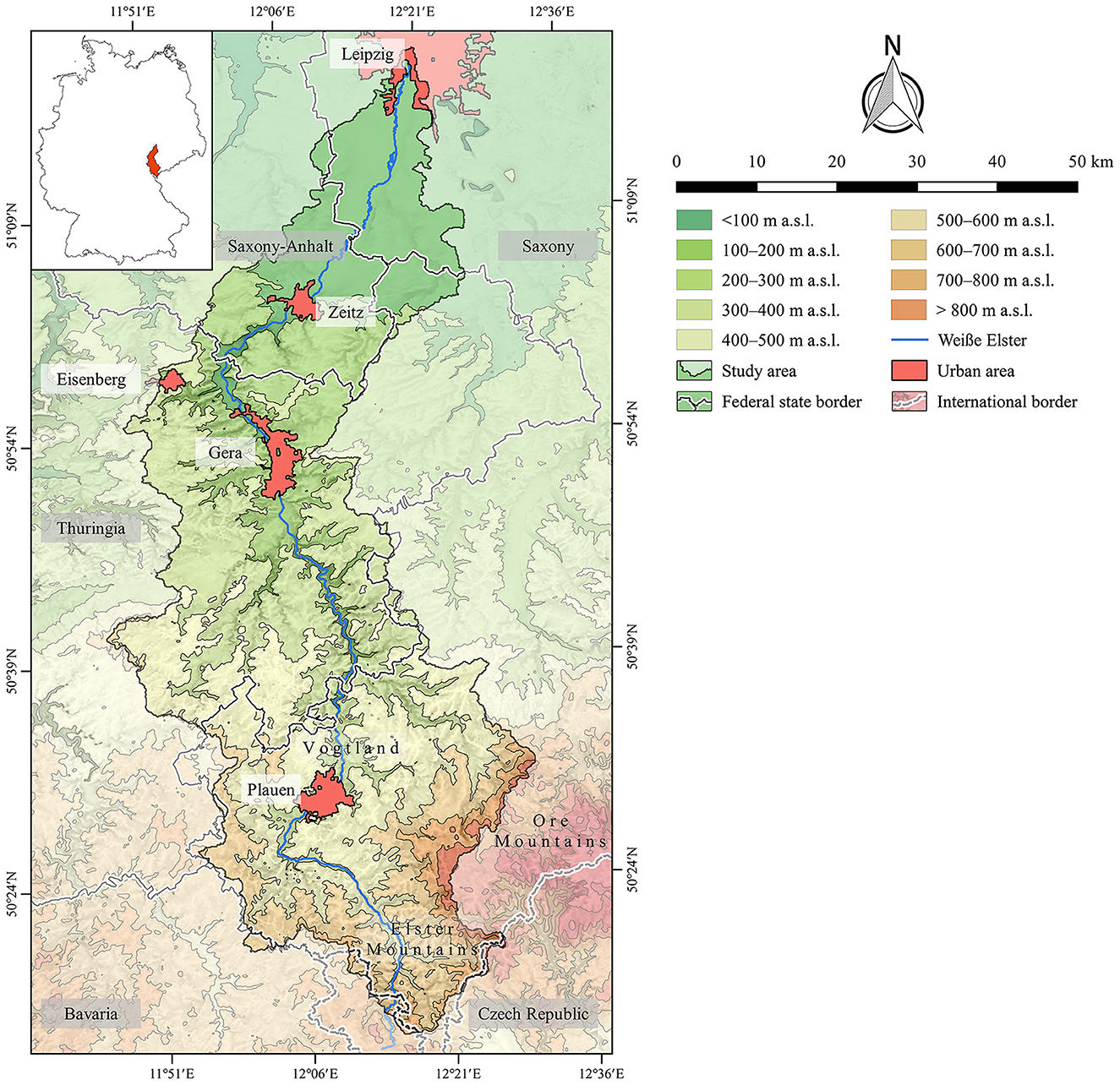

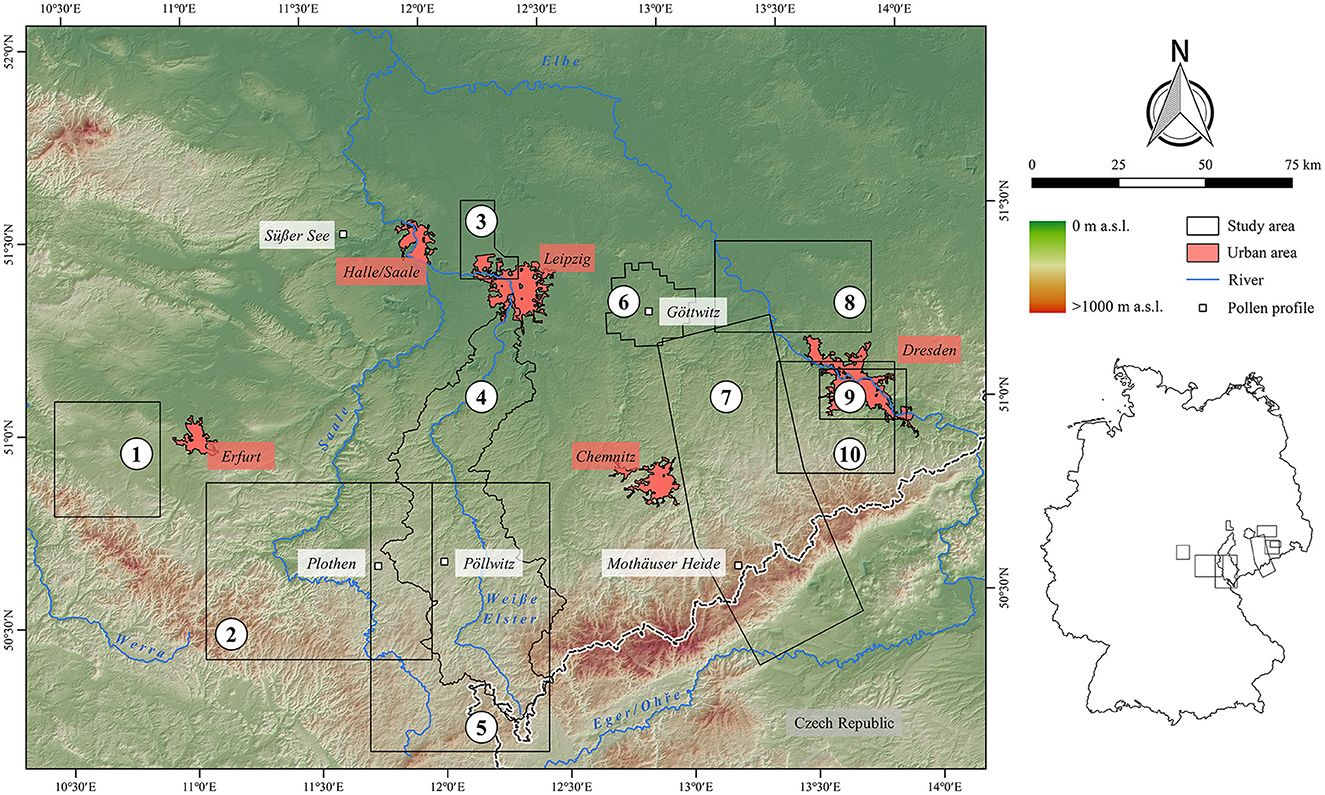

The study area is located in the tri-border region of the federal states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia (Figure 2). Its spatial extent corresponds to the catchment area of the Weiße Elster between Leipzig and the German-Czech border in the Elster Mountains. It covers an area of ~3,026 km2 and lies in the transitional region between two landscapes: the Northern German Plain (German: Norddeutsches Tiefland) and the Central Uplands (German: Deutsches Mittelgebirge) (Ssymank, 1994; Potschin and Bastian, 2004; Schwarzer et al., 2018a,b). The Northern German Plains are characterized by Cenozoic deposits (Kriebel et al., 1998; Radzinski et al., 1999), an average elevation between 100 and 200 m above sea level, gently rolling slopes and fertile chernozem/phaeozem and luvisol soils on loess (Stremme, 1951; Kasch et al., 1953, 1954). The average annual air temperatures is around 10°C and the average annual precipitation is 550–650 mm (DWD Climate Data Center, 2018a,b). The Central Uplands are geologically characterized by Mesozoic and Palaeozoic formations (Emmert et al., 1981). The landscape here reaches an altitude of up to 700 m above sea level. This is accompanied by lower mean annual air temperatures (9–7°C), higher annual precipitation (up to 1,050 mm) and longer winter and frost periods (DWD Climate Data Center, 2018a,b,c,d). The topography of the Central Uplands is also characterized by steep slopes and narrow river valleys. Furthermore, the landscape upstream is less favorable for agricultural use due to low-yielding dystric cambisols and stagnic gleysols (Hartwich et al., 1998; Panagos et al., 2012).

Figure 2. Study area with respect to borders of federal states, international borders, local topography and large urban areas mentioned in the text. The Catchment Characterization Model database (CCM2) was used to extract the research area's contours (Vogt et al., 2007). Political boundaries are drawn according to data from Federal Agency for Cartography and Geodesy [Bundesamt für Karthographie und Geodäsie (BKG), 2024]. The European Catchments and Rivers network system (Ecrins) (European Environment Agency, 2012) and the urban morphological zones dataset are used to determine rivers and urban areas (European Environment Agency, 2007). The SRTM 90 m Digital Elevation Database version 4.1 served as the basis for the topography (Farr et al., 2007; Reuter et al., 2007; Jarvis et al., 2008). Older topographic maps have been used to modify the topography and rivers (Miera et al., 2022).

3 Data and methods

3.1 Collection and processing of archaeological data

An archaeological database was set up for the diachronic analysis of prehistoric and early historical settlement dynamics in this study area. The archaeological archives of the Saxonian Archaeological Heritage Office, the State Office for Preservation of Monuments and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt and the Thuringian State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology served as the primary source of information for the database. In addition, the local archaeological literature was reviewed to fill in possible gaps and to consider the latest state of research. Sites without a date, such as potential burial mounds, ramparts and ditches, were only included when their geographical location was known. Sites of unknown date and without a geographical location were not included as their information content is too limited. All in all, between October 2017 and mid-2023, over 3,000 sites were recorded. These include 367 sites dating from the Bronze Age, which are the focus of this paper.

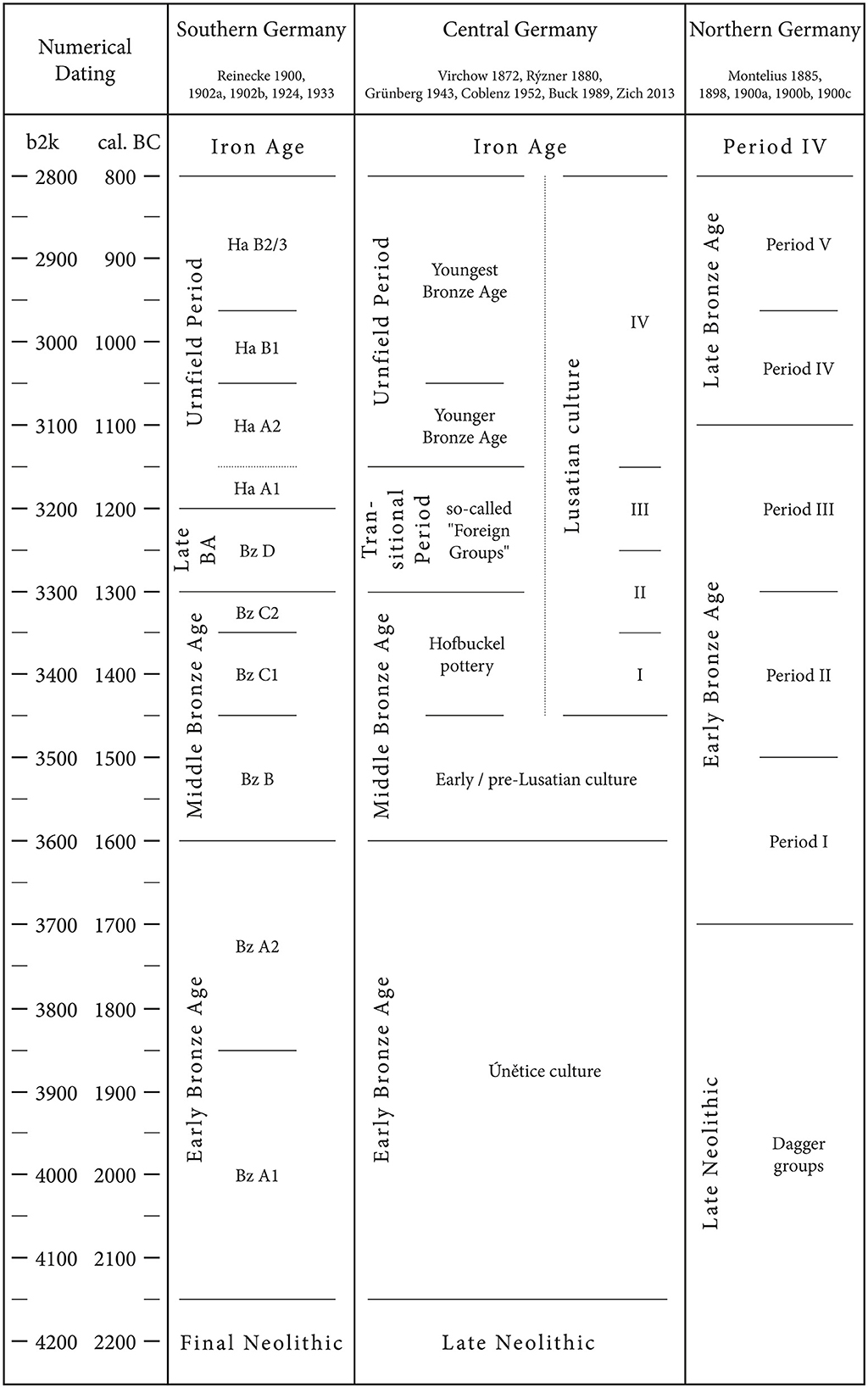

The identification of changes in prehistoric settlement patterns requires archaeological data with the highest possible chronological resolution. For this reason, the dating of the individual sites was recorded at different levels: epoch, period, phase and sub-phase (Eggert, 2012; Eggert and Samida, 2013). Whenever an imprecise dating was provided in the literature or in the archaeological archives, for example a dating between two periods, the respective site was dated to the older period (Schier, 1990). Central Germany presents a unique situation with regard to the dating of Bronze Age sites. Due to its geographical location, the archaeological finds are dated very differently in the literature: Depending on the authors either the chronological system for Northern Germany, Southern Germany or Central Germany is applied. This Babylonian confusion was not included in the database. Instead, all recorded sites were dated according to Paul Reinecke's chronology for Southern Germany. This system has a very high chronological resolution and can be easily translated into the terminology for Central Germany. The implementation of a standardized chronology in the database was a time-consuming step but it enabled the setup of a systematic basis for quantitative analyses and comparisons with data from neighboring regions.

In addition to the chronological resolution of the archaeological data, the quality of their spatial localization and the consistency of their functional classification are important prerequisites for the description and evaluation of settlement dynamics. Against this background, two types of coordinates are differentiated in the archaeological database: Sites with exact coordinates and sites with symbolic coordinates. Exact coordinates were assigned to those sites whose geographical position is known to an accuracy of ± 125 m. Symbolic coordinates, on the other hand, are assigned to all those sites that cannot (or can no longer) be localized in the field due to missing or insufficient geographical information. In these cases, either the presumed location or the church of the nearest village was taken as a point of reference (Ostritz, 2000).

To make the recording and analysis of a large number of sites as efficient as possible, only four types of sites are distinguished: settlements, burial sites, ritual sites and stray finds (Eggert, 2012; Eggert and Samida, 2013). A site is interpreted as a settlement once pits, postholes, building structures, grinding stones, loom weights, spindle whorls or pottery fragments are documented. Human bones and selected artifact ensembles are used as indicators for burial sites. Skeletal remains of humans that are documented in pits within a settlement are registered separately in the database as burial sites. Ritual sites include the deliberate deposition of multiple objects that are not grave, or settlement finds. Stray finds are artifacts and assemblages with little or no contextual information. These finds may be lost objects or material remains from settlements, burials or ritual sites that have (yet) not been identified as such (Schülke, 2011; Obst, 2012).

In geostatistical studies, the spatial definition and extent of archaeological sites is of paramount importance. This definition directly affects the absolute number of sites in any given study area (Pankau, 2004; Schmidt, 2019). For example, frequent construction works or repeated field surveys in a small area can result in the discovery of material remains from large settlements across multiple closely spaced sites. If each of those observations is treated as an independent site, all following (geo-)statics would be considerably distorted, such as the number of sites per period, the density of site distributions, or the importance of terrain covariates for settlement dynamics. Unfortunately, most sites have not been fully excavated, so their original extent remains unknown. As a result, large-scale studies often rely on an artificially defined standard for how sites are spatially grouped and aggregated (Hilbig, 1993; Mischka, 2007; Pankau, 2007). In this study, all sites with exact coordinates were aggregated if they (I) were located less than 250 m apart, (II) were dated in the same or a similar manner (e.g. “Bronze Age” + “Bronze Age”, “Early Bronze Age” + “Bronze Age”, etc.) and (III) were interpreted in either the same or a compatible way (e.g. “settlement” + “settlement”, “burial site” + “single find”, etc.). This approach ensures a basic level of consistency in how archaeological sites are analyzed, while also reflecting the realities of partial excavation and the challenges of interpreting spatial data (Miera et al., 2022).

3.2 Collection and processing of geographical data

For the source-critical analysis of site distributions and the analysis of settlement dynamics, a set of different continuous and categorical grid data was compiled (Supplementary Table 1). For each grid, the cell size was adapted to the spatial resolution of the sites and converted to 250 × 250 m. Some raster data had to be processed before they could be used for archaeological analyses. This applies to the digital elevation model (DEM) of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (Farr et al., 2007; Reuter et al., 2007; Jarvis et al., 2008).

In its original state, this DEM is not suitable for the analysis of site distributions because the terrain in the southern area of Leipzig has undergone considerable changes due to modern open-cast mining (Stäuble et al., 1996; Stäuble, 2010). For this reason, the DEM was corrected based on topographic maps from the early 20th century. Several maps at a scale of 1:25,000 were georeferenced and dozens of contour lines were digitized manually. On this basis, the DEM in the southern area of Leipzig was corrected over an area of 640 km2, i.e., modern disturbances were removed. In addition, old topographic maps were used to correct the courses of local rivers and streams that had been altered in the past 100 years due to the open-cast mining (for a documentation of the local DEM and river modifications see Miera et al., 2022).

It is important to emphasize that the datasets created in this way only represent approximations to prehistoric and early historical conditions as landscapes are subject to constant changes (Gerlach, 2006; Gerlach and Meurers-Balke, 2017). For the processing and analysis of the geographical data, the System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses (SAGA) as well as QGIS and R were used (Conrad et al., 2015; R Core Team, 2020; QGIS Development Team, 2023).

3.3 Archaeological source criticism

In regional studies like this paper, prehistoric and early historical settlement patterns are typically explored by comparing distribution maps across different time periods. These findings are then quantified and analyzed using geostatistical methods and geographic information systems (GIS). To further strengthen the analysis, source-critical approaches are employed to evaluate the representativeness of the archaeological record and the reliability of conclusions drawn from it (cf. Jacob-Friesen, 1928; Eggers, 1959; Gerhard, 2006; Lucas, 2012).

Generally, it can be assumed that the current distribution of archaeological sites is shaped by three types of filters: (I) archaeological filters, i.e., the type and intensity of archaeological fieldwork, (II) geographical filters, such as modern land use and processes of soil redeposition as well as weathering, and (III) culturally intrinsic filters, such as the duration of the archaeological periods under investigation as well as the visibility and identifiability of the archaeological remains from those periods (Pankau, 2007).

The archaeological and geographical filters will be the focus of the following sections. Culturally intrinsic filters, on the other hand, will be addressed in the discussion in the form of a qualitative review of research contributions.

3.4 Archaeological filters

3.4.1 State of research

The current state of archaeological research on the Bronze Age will be summarized using selected key data derived from the database. These include the number of sites per period, their functional interpretation, as well as the accuracy of their coordinates. In addition, it will be analyzed how many of them have been published and what kind of field work has been carried out. Furthermore, the time of discovery of the individual sites is examined. For this purpose, the number of site discoveries is counted for each decade (Schmotz, 1989; Schier, 1990).

3.4.2 Intentionality of site discoveries

There are a variety of activities that can lead to the discovery of archaeological sites. A systematic evaluation of these activities provides an invaluable basis for understanding the temporal and spatial dimensions of archaeological data (Dauber, 1950). In general, a distinction can be made between intentional and non-intentional modes of discoveries (Wilbertz, 1982). The first category includes activities that are archaeologically motivated, i.e., activities aimed at the discovery of material remains or features. For example, this includes excavations as well as field and aerial surveys. In contrast, non-intentional modes of discovery are activities that take place without archaeological motivation such as construction works, the extraction of raw materials, plowing, forestry or hikes. The differentiation between intentional and non-intentional modes of discovery is important insofar as non-intentional data potentially represent a true random sample of the chronological and spatial distribution of the recorded sites (Schier, 1990).

An examination of the intentional modes of discovery sheds light on whether and to what extent site distributions are distorted by field surveys and/or aerial surveys. It has been observed repeatedly that individual people can considerably influence the regional status of archaeological field research. This happens when there is a very strong focus on selected landscapes, types of sites (e.g., burial mounds) or time periods (Mischka, 2007; Pankau, 2007). For this reason, the name of the respective discoverer was recorded during data collection, provided it had been handed down. In general, it can be assumed that individuals can only cause local distortions in the archaeological record once a certain number of discoveries have been made. For this reason, only people who discovered at least nine sites during archaeologically motivated activities are considered in the analysis (Hinz, 2014).

Both the area covered by field surveys as well as the area covered by aerial surveys is calculated and described using the concept of the largest empty circle (Zimmermann and Wendt, 2003; Frank, 2007; Ahlrichs et al., 2016). The areas covered by each method are calculated separately because field surveys and aerial surveys have their own advantages and disadvantages. For example, aerial surveys can result in the discovery of archaeological features on or just below the recent surface that are not (or no longer) recognizable in the field. Field surveys, on the other hand, may result in the discovery of small artifacts on the ground that are not visible from the air (Schier, 1990; Schülke, 2011).

The mapping and evaluation of the surveyed areas is based on isolines representing an average site density of 1.5 and 2.5 km. These threshold values were chosen freely, as there are no standards for the delineation of modeled areas (Mischka, 2007). It should also be noted that only positive detections with an exact localization could be used to determine the potentially walked or flown areas. Negative observations cannot be considered because they are not systematically documented. In this respect, the modeled areas tend to be smaller than the areas actually investigated.

3.5 Geographical filters

3.5.1 Site distribution in relation to archaeological site visibility and preservation of material remains

Archaeological site distributions are not only effected by the intentionality of individual site discoveries, but also by the visibility of the sites themselves. The visibility of archaeological sites and the preservation of material remains are known to be effected by local geomorphic terrain dynamics. Alluviation and colluviation can result in the superimposition of prehistoric sites and thereby protect them from weathering. However, this is taking place at the expense of their visibility. On the other hand, prehistoric sites may be uncovered as a result of erosion, improving accessibility at the expense of worse preservation conditions or even their total destruction because of increased exposure to weathering and plowing.

These geographical filters can be studied on the basis of the site discoveries. Each mode of discovery provides information about the depth of the respective archaeological site. One group consists of (I) sites that are found on the surface. These sites are often long known (i.e. burial mounds, ditches, ramparts, etc.) or are discovered by chance. Furthermore, field surveys result in the discovery of sites on the recent surface. (II) A further group consists of sites buried beneath the modern surface. These are typically discovered during construction works, plowing, forestry, the extraction of raw materials or excavations (Schier, 1990; Saile, 1998). This information can be used to analyze how many Bronze Age sites were recorded on the recent surface and how many of them were buried due to natural or anthropogenic erosion processes. This is crucial for the evaluation of field surveys.

In addition, it is important to discuss the preservation conditions of the material remains themselves. To address this issue, the type of material discovered at each site was recorded. A general distinction was made between pottery and artifacts made of stone or metal as these are the most common material typeson Bronze Age sites. The information derived from the various modes of discovery can be utilized to investigate if the different materials are predominantly associated with buried sites or not. For example, if pottery is mainly found at buried sites this might indicate a disintegration of this material on the surface due to long exposure to weathering.

3.5.2 Site distribution in relation to modern land use

Since the early 20th century, recent land use has repeatedly been identified as a filter whose examination contributes to the understanding of contemporary site distributions (cf. Wahle, 1921; Koschik, 1981; Vogt and Kretschmer, 2019). To investigate the influence of modern land use on Bronze Age site distributions, the grid dataset from the European CORINE (Coordination of Information on the Environment) Land Cover (CLC) project of the European Environment Agency (EEA) is used (European Environment Agency, 2007). This dataset has already been used successfully in several studies for source-critical analyses (Kerrel et al., 1991; Pankau, 2007; Fender, 2017; Sauer, 2018). The dataset is derived from satellite images and distinguishes a total of 44 classes of modern land use with a spatial resolution of 100 × 100 meters (European Environment Agency, 2007). In its original state, the dataset is too complex for archaeological research and statistical analyses due to the large number of land use classes. It is therefore recommended to aggregate it to the following basic types of modern land use: urban areas, forests, arable land, grassland, water bodies, bogs and open-cast mines (Mischka, 2007; Pankau, 2007; Hinz, 2014). Following the aggregation of the land use classes, an additional modification had to be made because not all open-cast mining areas in the southern area of Leipzig were recorded in the raster dataset (cf. Miera et al., 2022).

Here, the chi-squared test is used to analyze the distribution of sites across the land use classes (formula explained by Shennan, 1988; Barceló, 2018). In this method, two observations are related to each other: the frequency distribution of modern land use classes in the study area and the frequency distribution of the sites across the individual land use classes. Only sites with exact coordinates are used for this analysis. If modern land use has no impact on the distribution of the sites, the frequency distribution of the sites across the land use classes should be congruent with their respective occurrence in the study area. Any differences between the observed and expected number sites indicate that the respective type of land use has a positive or negative effect on the preservation and visibility of archaeological sites. Finally, the chi-squared value can be used to determine the extent to which the observed deviations are statistically significant (Mischka, 2007; Pankau, 2007).

3.6 Analysis of settlement dynamics

3.6.1 Site frequency

Bronze Age settlement patterns are analyzed in chronological and spatial terms. One straightforward way to assess local settlement intensity is by calculating site frequency. This metric relates the number of sites recorded during a specific period to the length of that period. To compute the site frequency, the total number of sites dating to a given period is multiplied by 100 and then divided by the duration of the respective period in years. In other words, site frequency represents the average number of sites per century for each period, making it a useful tool for comparing periods with different durations side-by-side (Schmotz, 1989; Paetzold, 1992).

This approach has been widely applied in diachronic studies (Saile, 1998; Schefzik, 2001; Pankau, 2007; Wegener, 2014; Ahlrichs et al., 2018; Miera, 2020). However, it's important to note that the size of a study area directly affects the total number of sites recorded during a period. Larger regions naturally yield higher site frequencies compared to smaller ones. To account for this, the average site frequency per 250 km2 is calculated for all study areas included in a supra-regional contextualization of Bronze Age site frequencies from the Weiße Elster catchment (formula provided in Miera et al., 2022).

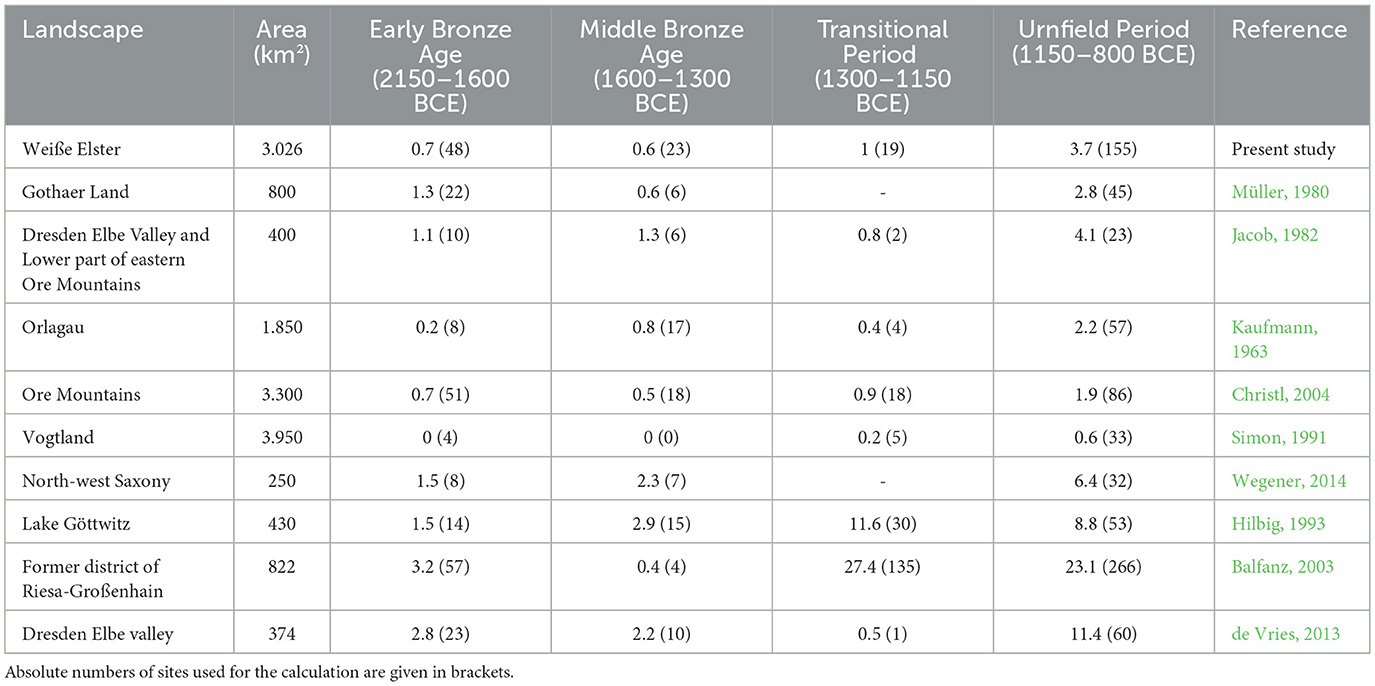

Another key step in comparing site frequencies across neighboring regions is aligning the archaeological data to a single chronological framework. Here, the absolute numbers of Bronze Age sites are grouped into the following time windows: Early Bronze Age (2150–1600 BCE), Middle Bronze Age (1600–1300 BCE), Transitional Period (1300–1150 BCE), and Urnfield Period (1150–800 BCE) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Chronological system for the Bronze Age in Central Germany according to Virchow (1872), Rýzner (1880), Grünberg (1943), Coblenz (1954), Buck (1989), and Zich (2013). The synchronization with the systems of Reinecke (1900, 1902a,b, 1924, 1933) and Montelius (1885, 1898, 1900a,b,c) is based on Puttkammer (2008a,b) and Gramsch (2010).

3.6.2 Site distribution and density

Two methods are combined to describe the spatial distribution of Bronze Age sites. The first is based on point mapping, which distinguishes between sites with exact and symbolic coordinates. In addition, the density of sites with exact coordinates is determined based on the largest empty circle (LEC). To increase the comparability of the period-specific site distributions, the isolines for an average site density of 1.5 and 2.5 km are used. This procedure makes it possible to identify geographical focal points of settlement for each period and thus derive long-term settlement dynamics from the maps (Zimmermann et al., 2005, 2009; Schmidt et al., 2021). The inclusion of sites with a symbolic coordinate is done deliberately. Even archaeological data with a less optimal state of research provide important information on prehistoric settlement dynamics when mapped on a larger scale. This also prevents the potential fallacy that areas without sites were not settled in prehistoric times.

3.6.3 Spatial continuity and affinity of Bronze Age periods

Furthermore, a geostatistical approach is used to examine how different periods overlap in the immediate surroundings of the recorded sites. By doing so, key changes in local settlement patterns and recurring trends can be identified that cannot be detected through site frequencies and differences in site densities (Schier, 1985, 1990; Saile, 1998, 1999; Gebhard, 2007).

The spatial continuity and affinity of Bronze Age periods is examined by creating a 250-meter radius around each site with exact coordinates. Within these defined areas, the chronological frequency distribution of the sites is calculated. The K* coefficient is then used to quantify the observed co-occurrence of different periods. It is calculated in two steps (Saile, 1999):

Where K is the preliminary and non-normalized version of K*, Z is the absolute number of sites dating to one period, S is the absolute number of sites dating to the other period, and B is the absolute number of instances where Z and S occur together.

Where K* is the normalized coefficient, K is the preliminary and non-normalized version of K*, Z is one period, S is the other period.

K* reaches a maximum value of 1 when all sites of one period are spatially associated with another period – for example, if all Middle Bronze Age sites are recorded within the area covered by the 250-meter radii of Early Bronze Age sites. In case of a low spatial affinity, K* tends toward zero (Saile, 1999). To evaluate the impact of different types of archaeological sites on this metric, the analysis is carried out in three ways: (I) based on settlements alone, (II) based on settlements and burial sites, and (III) by considering all sites regardless of their functional interpretation.

3.6.4 Site Exploitation Territories (SETs) and settlement dynamics

It is likely that communities' perceptions and use of their environment evolved over the course of the Bronze Age. This hypothesis can be tested using a geostatistical analysis of how recorded sites were distributed across selected terrain covariates. Here, this is done using the concept of SETs, which differs from traditional point pattern analyses and Site-Catchment Analyses (SCA). Unlike those methods, SETs account for the topographical context of each site (Higgs, 1972, 1975; Jarman et al., 1972, 1982). A SET is an area that could have been exploited economically, defined by the time it takes to travel to and from the site. Accordingly, its shape is heavily influenced by local topography, meaning SETs tend to form circular shapes in flat regions and irregular shapes in low mountainous areas (cf. Bailey and Davidson, 1983; Valde-Nowak, 2002).

Ethnographic observations have provided important clues for the definition of time distances for mobile and sedentary societies. In sedentary societies, the resources necessary for everyday life are in an area that can be reached on foot within an hour. The most important agricultural and economic areas are located directly at the place of residence and can be reached within 10 to 15 min (Vita-Finzi and Higgs, 1970; Higgs and Vita-Finzi, 1972; Jarman, 1972).

Accordingly, the individual SET for a time-distance of 10 min is modeled for each Bronze Age site with an exact coordinate. For this purpose, a freely available script for the programming language R is used (Ahlrichs et al., 2016; Miera et al., 2023). The DEM with a resolution of 250 × 250 meters, an estimated walking speed of 5 km/h in flat terrain (Tobler, 1993) and an attenuation of the walking speed on slopes with an inclination of >15° serve as a working basis. For the description of the site distribution via terrain covariates, two statistics are collected for each period: (I) once for all sites and (II) once exclusively for settlements (Miera et al., 2022).

The following parameters are used to characterize the SETs: the size of the modeled SETs, the altitude above sea level, the slope steepness and the altitude above the nearest water body, the distance to the nearest water body and the proportion of soils on loess within the modeled SETs (Supplementary Table 1). It is important to keep in mind that all these parameters are subject to both natural and anthropogenic changes (Gerlach, 2006; Eckmeier et al., 2011; Gerlach and Meurers-Balke, 2017). SET analyses should therefore be understood as models that represent an approximation to prehistoric conditions and provide a general basis for discussing settlement dynamics.

4 Results

4.1 Archaeological filters

4.1.1 State of research

The archaeological record of Bronze Age settlements in the Weiße Elster catchment area comprises 367 sites. Due to the nature of the archaeological record, only a fraction of the sites can currently be chronologically analyzed at the level of phases or even sub-phase. Therefore, the Bronze Age settlement dynamics in the study area will be investigated at the level of periods.

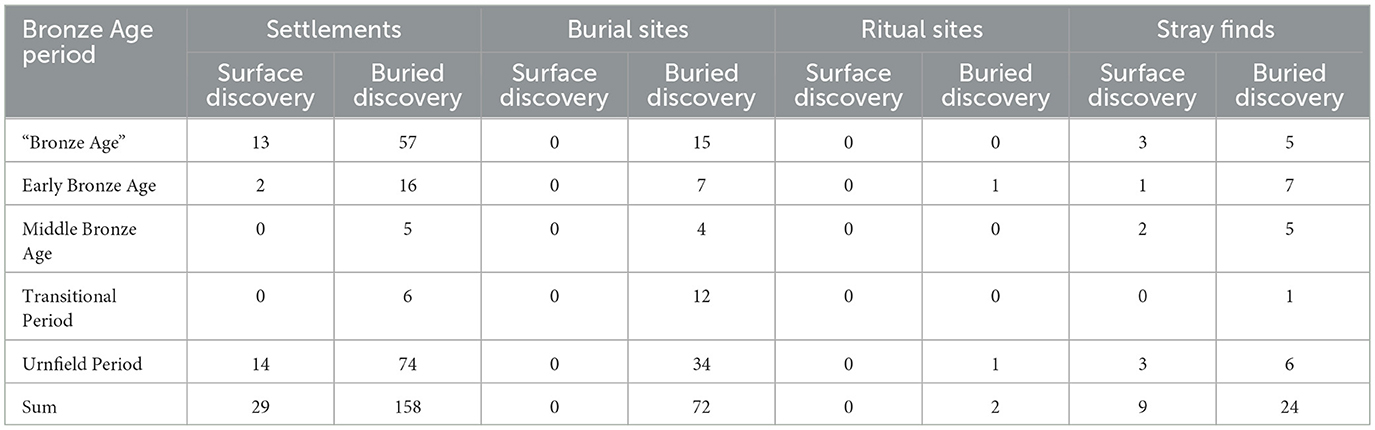

Out of the 367 sites, 48 date to the Early Bronze Age, 23 to the Middle Bronze Age, 19 to the Transitional Period and 155 to the Urnfield Period. In addition, there are 122 sites that are generally described as “Bronze Age” due to a lack of diagnostic finds. The frequency distribution of the site types across the periods is remarkable. Significantly more settlements than burial sites were recorded from the Early Bronze Age and the Urnfield Period—the same applies to the “Bronze Age” sites without a more precise date. The Middle Bronze Age sites show a balanced relationship between settlements and burial sites. However, this period is mainly documented by stray finds. The Transitional Period is distinguished from the other periods by the fact that the number of recorded settlement sites is only half as high as the number of burial sites (Supplementary Table 2).

In total, 265 of the recorded sites can be precisely localized (Supplementary Table 2). The remaining 107 sites were given a symbolic coordinate. Within the Early and Middle Bronze Age, the number of sites without localization is relatively high. In contrast, the Transitional Period and the Urnfield Period are characterized by a low proportion of symbolic coordinates. This trend can be explained by the fact that stray finds make up a relatively large proportion of the Early and Middle Bronze Age dataset and that these are often old finds with no details of the find location.

The frequency distribution of site discoveries per decade reflects the local development of heritage management as well as political developments in Germany (Supplementary Figure 1). While the decades of the 19th century are characterized by a low frequency of discoveries, an increase marks the beginning of the 20th century. The increasing number of site discoveries between 1901 and 1910 and in the period from 1921 to 1940 goes hand in hand with a systematization of heritage management (Schmidt, 1986; Aichinger and Grasselt, 2010; Heynowski, 2010a; for a critical review of archaeological research between 1933 and 1945 see Härke, 2000; Leube, 2002; Halle, 2013; Grunwald et al., 2016). There is a noticeable decline in discoveries in the decades overlapping with the First and Second World War. This development can be observed across Germany (Pankau, 2007; Schülke, 2011; Miera, 2020). In the 1950s, the number of discoveries returned to pre-war levels and declined again until 1990. Following the reunification of Germany, many construction projects were carried out in the 1990s, the archaeological supervision of which led to a substantial increase in discoveries and excavations (Fröhlich, 1998). Almost a fifth of all Bronze Age sites were discovered in the 1990s. After the turn of the millennium, the frequency of site discoveries declined (Supplementary Figure 1).

An examination of the publication status shows that more than half of the Bronze Age sites had not been published at the time of data collection. These sites were previously only known in the archaeological archives (Supplementary Table 3). The proportion of unpublished sites from the Early Bronze Age and Urnfield Period and in the group of “Bronze Age” sites is comparatively high. The Middle Bronze Age and the Transitional Period take a special position insofar as most sites from these periods have been published. Furthermore, depending on the type of site, the proportion of (un)published sites varies: most settlements and stray finds have not yet been published. This applies in particular to the sites that have been discovered during excavations since the 1990s. In contrast, most burial sites and hoards have been published (Supplementary Table 3).

4.1.2 Intentionality of site discoveries

For a total of 294 Bronze Age sites, it was possible to determine the circumstances that led to their discovery (Supplementary Table 4). The majority can be attributed to non-intentional modes of discovery, in particular construction works and the extraction of raw materials. Only 60 sites from the Bronze Age were discovered during archaeologically motivated activities such as field surveys or excavations. The proportion of non-intentional discoveries predominates in all types of sites.

The chronological frequency distribution of non-intentional discoveries shows that a decline in sites characterizes the transition from the Early to the Middle Bronze Age. In contrast, the absolute proportion of non-intentionally discovered sites from the Transitional Period does not differ from that of the Middle Bronze Age. Finally, the Urnfield Period, on the other hand, is marked by a considerable increase in the number of sites.

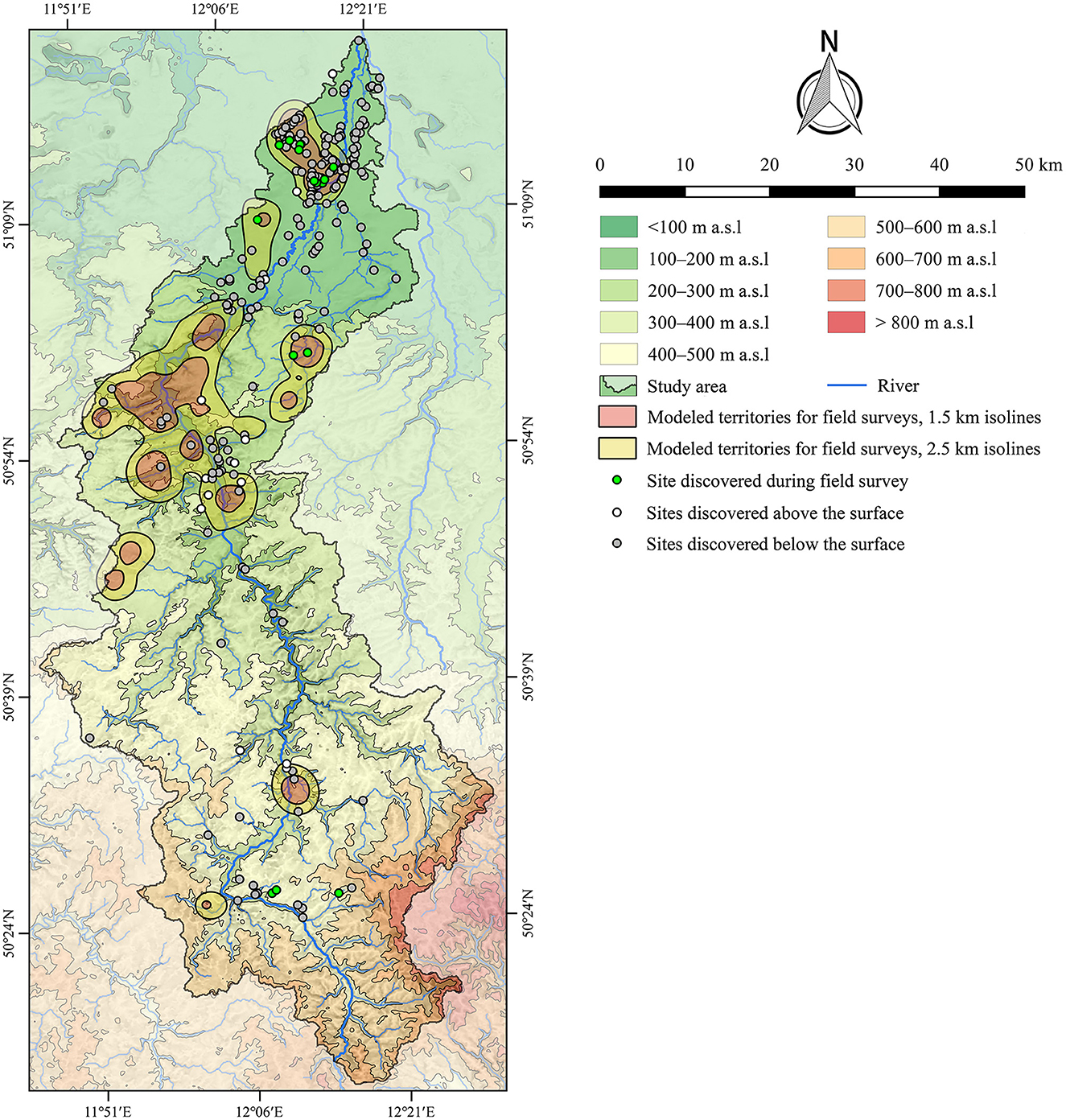

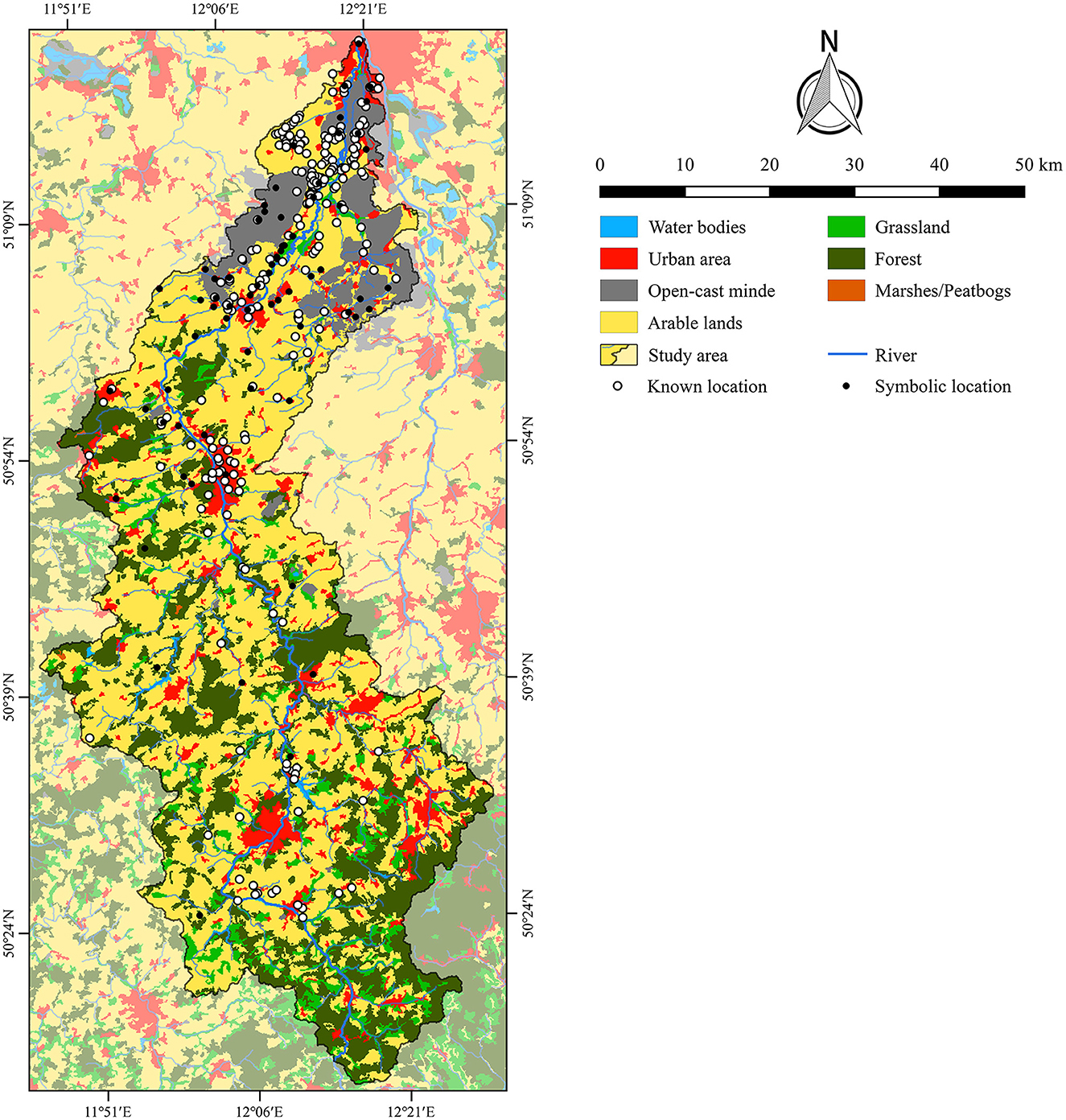

In total, 12 individuals have identified nine or more sites each within the study area. Together, they documented 263 prehistoric and early historic sites, which were used to model potential survey areas (Figure 4). This analysis highlights a concentration of successful field work south of Leipzig and within the Zeitz–Eisenberg–Gera triangle. Smaller regions are also present north and south of Plauen in the Vogtland. However, the 12 individuals discovered no more than 15 Bronze Age sites altogether (Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 4. Distribution of Bronze Age sites with respect to their modes of discovery against the background of areas investigated by field surveys and aerial photography. Rivers are plotted according to the European Catchments and Rivers network system (European Environment Agency, 2012). The topography is based on the SRTM 90 m Digital Elevation Database version 4.1 (Farr et al., 2007; Reuter et al., 2007; Jarvis et al., 2008). Topography and rivers are modified according to older topographic maps (Miera et al., 2022). See Figure 2 for the location of the urban areas mentioned in the text.

4.2 Geographical filters

4.2.1 Site distribution in relation to archaeological site visibility and preservation of material remains

Most Bronze Age sites were buried at the time of their discovery. This is true for the individual periods as well (Table 1). Whenever sites were discovered on the surface, this usually happened in the context of archaeologically motivated activities, i.e., there are very few accidental discoveries of Bronze Age sites on the surface. In the case of buried sites, the relationship between intentional and non-intentional types of discoveries is reversed. Here, activities without archaeological motivation account for the largest share.

Table 1. Chronological distribution of sites with regard to their depth at the time of their discovery.

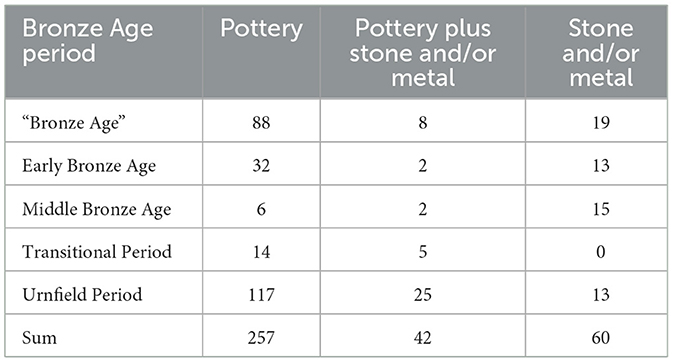

There are 257 sites from the Bronze Age where only pottery artifacts have been found (Table 2). In addition, there are 42 sites where stone and metal artifacts were documented alongside pottery. Only stone or metal artifacts are known from 60 sites. The material groups are unevenly distributed across the periods: sites from the Early Bronze Age and the Urnfield Period were identified based on both pottery and metal artifacts. However, in these periods the proportion of sites where only pottery was found predominates. The Middle Bronze Age, on the other hand, is mainly documented by metal finds. The opposite is true for the Transitional Period: this period is known almost exclusively through pottery finds (Table 2).

Intentional discoveries are more frequent at surface sites where only pottery was recorded (Table 3). However, most of the sites where only pottery was recorded were buried below the recent surface when they were discovered, and the finds were made by accident. In contrast, the proportion of intentional to accidental discoveries is roughly equal at surface sites where only stone or metal artifacts have been found. This suggests that bronze artifacts are more easily recognized and likely better preserved than pottery.

Table 3. Frequency distribution of material groups with regard to the intentionality and depth of their discoveries.

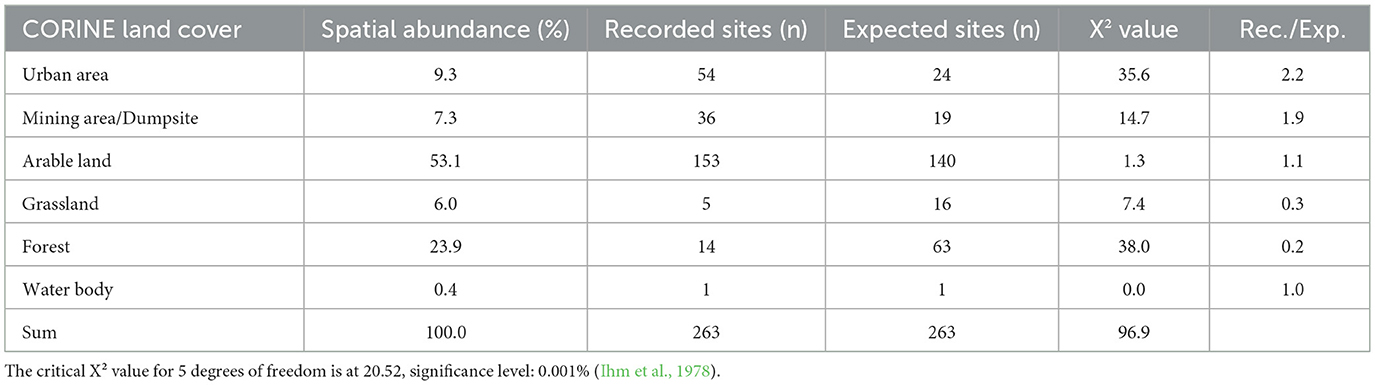

4.2.2 Site distribution in relation to modern land use

The individual land use classes are represented to varying degrees in the study area. Arable land (53.1%) and forest (23.9%) account for the largest shares. Urban areas, open-cast mines and grassland account for 6–9%. Water areas account for only 0.4% of modern land use. Marshes and peatbogs cover only 1 km2 of the study area and thus account for less than 0.1%. For this reason, these latter classes of land use are not considered further in the source-critical analysis.

The Bronze Age sites show an uneven distribution across the modern land use classes (Figure 5). This observation is statistically significant (see Table 4). This result is primarily due to the fact that approximately twice as many sites were recorded in urban areas and in the vicinity of open-cast mines than would have been expected if there had been an even distribution across all land use classes. Wooded areas and areas classified as grassland also contribute to the uneven distribution. Here, the number of documented sites is far below the respective expected value. Arable land and water areas occupy a neutral position, i.e., the deviations between the observed and expected values are minimal.

Figure 5. Modern land use and Bronze Age site distribution in the study area. Distribution of modern land use classes according to CORINE Land Cover data (European Environment Agency, 2007). The spatial extent of the (refilled) open-cast mines has been modified according to older topographic maps (Miera et al., 2022).

4.3 Analysis of settlement dynamics

4.3.1 Site frequency

On average, the Bronze Age site frequency is around 28 sites per century. With the transition from the Early to the Middle Bronze Age, a slight decline from nine to eight sites per century can be observed. In the Transitional Period, the frequency of sites rises to 13 before reaching a maximum of 45 sites per century in the Urnfield Period.

4.3.2 Site distribution and density

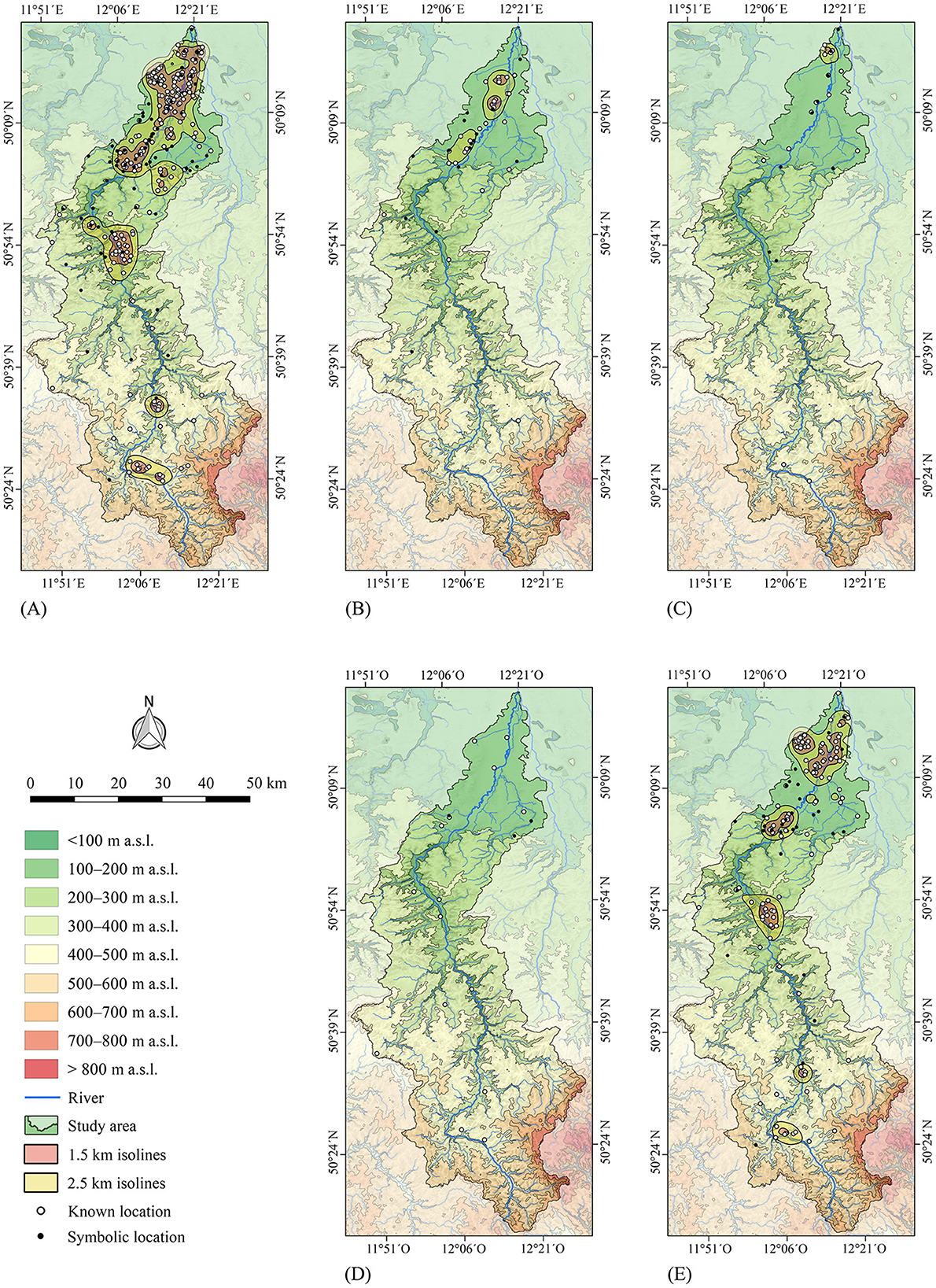

The distribution of 75% of the Bronze Age sites can be described using the 1.5 km isolines (Figure 6). If the 2.5 km isolines are considered, 89% of the sites are covered with an exact coordinate. Three geographical focal points can be identified: these include a large contiguous area between Leipzig and Zeitz. Here, the sites are primarily located along the Weiße Elster and smaller tributaries. In addition, the 1.5 and 2.5 km isolines describe an increased density of sites near Gera and two smaller areas north and south of Plauen in the Vogtland.

Figure 6. Bronze Age site densities in the study area. (A) Entire Bronze Age, (B) Early Bronze Age, (C) Middle Bronze Age, (D) Transitional Period and (E) Urnfield Period. Rivers are plotted according to the European Catchments and Rivers network system (European Environment Agency, 2012). The topography is based on the SRTM 90 m Digital Elevation Database version 4.1 (Farr et al., 2007; Reuter et al., 2007; Jarvis et al., 2008). Topography and rivers are modified according to older topographic maps (Miera et al., 2022). See Figure 2 for the location of the urban areas mentioned in the text.

A separate analysis of the individual periods shows that the Early Bronze Age sites are concentrated along the Weiße Elster south of Leipzig. Few sites from this period are known from the area of the Central Uplands. In general, this period is characterized by a rather loose scattering of sites: the 1.5 km isoline covers only 30% and the 2.5 km isoline 63% of the sites. The Middle Bronze Age is characterized by a wide scattering of sites. Only in the south of Leipzig a small area with an increased site density is outlined by the 2.5 km isoline. However, only 29% of the sites from this period are in this area. Furthermore, there is a vague correlation to the Weiße Elster valley. In addition, several isolated sites from the Central Uplands are known. The Transitional Period occupies a special position because the sites from this period are so loose and widely scattered that neither isoline can identify a concentration of sites. Compared to previous periods, it can only be noted that the number of sites in the Central Uplands has increased. By contrast, several areas with an increased site density can be identified for the Urnfield Period. The 1.5 km isolines already describe the distribution of 57% of all sites with exact coordinates. The 2.5 km isolines cover 77% of the sites dating to this period. There are remarkable concentrations of sites along the Luppe river, along the Weiße Elster between Zwenkau and Pegau, and in the surroundings of Zeitz and Gera. In the Central Uplands, there are two smaller concentrations of sites near Plauen.

4.3.3 Spatial continuity and affinity of Bronze Age periods

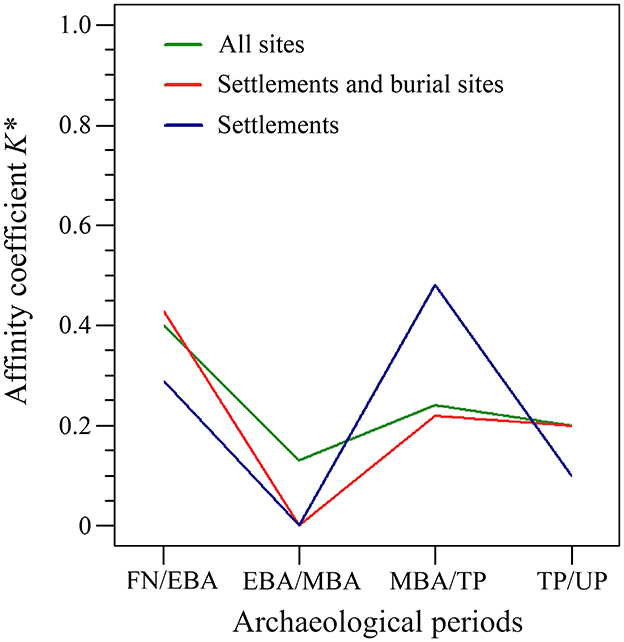

While the Early Bronze Age has a high spatial affinity to the Late Neolithic, a clear break in K* can be observed at the transition to the Middle Bronze Age (Figure 7). There is no spatial affinity between the Early and Middle Bronze Age settlements and burial sites. Even when considering all types of sites, including hoards and stray finds, the spatial affinity between these periods is very low. The opposite is true for the shift from the Middle Bronze Age to the Transitional Period. The few known settlements from these periods show a high affinity. The transition to the Urnfield Period is again characterized by a sharp drop in K*.

Figure 7. Affinity coefficient K* (Saile, 1999) of prehistoric periods in the Weiße Elster catchment based on all sites (green), the settlement and burial sites (red) and the settlement sites alone (blue). Periods: Final Neolithic (FN), Early Bronze Age (EBA), Middle Bronze Age (MBA), Transitional Period (TP), Urnfield Period (UP).

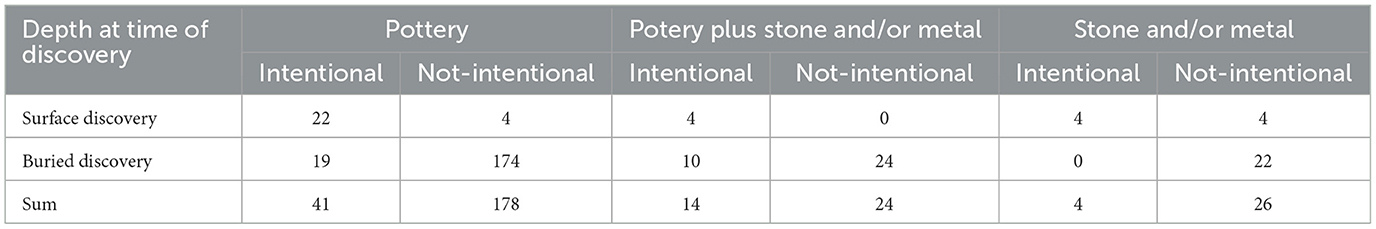

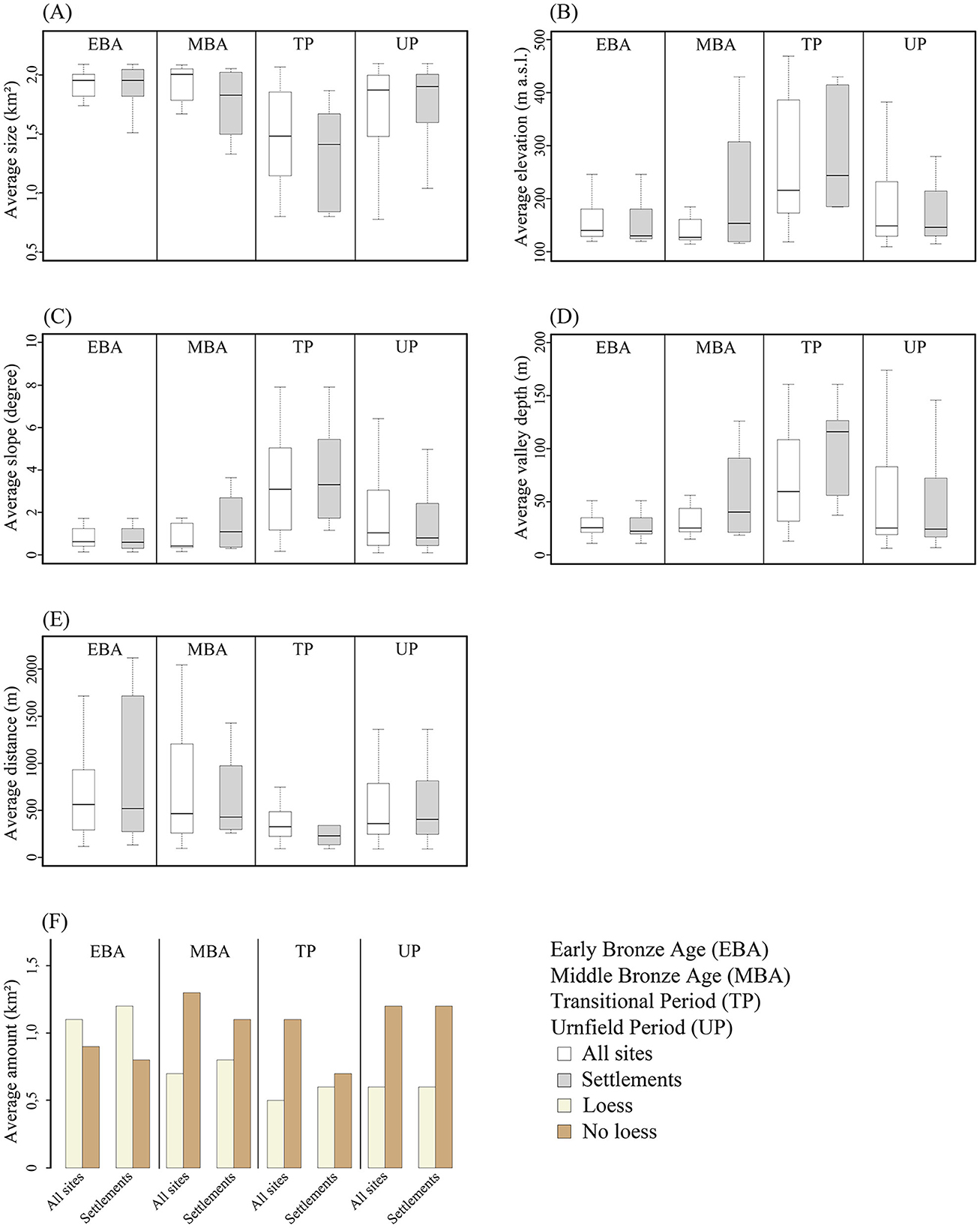

4.3.4 Site Exploitation Territories (SETs) and settlement dynamics

By investigating terrain covariates based on SETs, the dynamics of Bronze Age land use can be characterized more precisely (Figure 8). The data for the Early Bronze Age, for example, illustrate the focus on the Northern German Plain. This can be recognized by large SETs resulting from the settlement of areas with gentle slopes and low terrain elevation. The distribution of the Early Bronze Age sites is also characterized by a low altitude above the nearest river, combined with rather long distances to the nearest river. Within the Early Bronze Age SETs, soils on loess predominate. This tendency becomes even more apparent in a separate analysis of the settlements.

Figure 8. Analyses of Site Exploitation Territories. (A) Size of modeled SETs, (B) terrain elevation, (C) slope, (D) valley depth, (E) river distance and (F) soils on loess and soils not on loess. For more information on each terrain covariate see Supplementary Table 1.

At first sight, the distribution of the Middle Bronze Age sites hardly differs from that of the Early Bronze Age. However, stronger contrasts become visible when looking at the settlements separately. Here there is a tendency toward smaller SETs, due to the more frequent occurrence in areas with steeper slopes. As a result of increased settlement activity in the Central Uplands, there is a higher location above the nearest river and a shorter distance to it. Soils on loess no longer predominate the vicinity of the sites.

The distribution of sites from the Transitional Period differs considerably from the preceding periods and the subsequent Urnfield Period. One of the characteristics is an increase in the average height of the terrain within the SETs. The average size of the SETs decreases as a result due to a focus on areas with more pronounced slopes. There is a noticeable reduction in the distance to the nearest river, while the height above the nearest valley increases. These tendencies become more apparent in the settlement SETs from the Transitional Period. While the average proportion of soils on loess within the SETs is low, the immediate surroundings of the settlements from the Transitional Period are characterized by a balanced proportion of soils on loess.

Sites from the Urnfield Period are primarily observed in areas with a lower slope gradient in the Northern German Plain and therefore show a tendency toward larger SETs. Compared to the Transitional Period, the distance to the nearest river increases, while the height above the nearest river valley is reduced. The average proportion of soil on loess in the vicinity of the sites is comparatively low.

5 Discussion

5.1 Spatial and chronological representativeness of the Bronze Age record

5.1.1 Site distribution with respect to modern land use and archaeological surveys

Modern land use classes are not tied to archaeological criteria. Therefore, they represent an independent sample in terms of the spatial and temporal distribution of archaeological sites (Hinz, 2014; Miera et al., 2022).

This study shows that Bronze Age sites are more likely to be found in urban areas, open-cast mines, and agricultural land. These land use classes are more likely to reveal buried sites as they are associated with construction, farming, or mining. As a result, these land use types can be considered positive filters—they make it easier to find archaeological sites. In contrast, forests, grasslands, and water bodies are more likely to act as negative filters. These environments tend to hide or obscure archaeological evidence, making it harder to detect sites. Similar patterns have been observed in other parts of Germany (Mischka, 2007; Pankau, 2007; Hinz, 2014; Miera, 2020).

The negative filters are mainly found in the Central Uplands. However, they cover less than 30% of the study area, while the positive filters account for 70%. This suggests that the conditions for discovering buried sites are good, even in the Central Uplands. Therefore, the distribution of Bronze Age sites is only partially biased by modern land use, and general conclusions about settlement patterns can still be drawn from distribution maps.

In addition, a biased site distribution due to field surveys and aerial photography can be ruled out. Together, both methods led to the discovery of only 16 Bronze Age sites. Remarkably, a total of 139 Bronze Age sites with exact coordinates were recorded within the modeled territories for field surveys and aerial photography. These sites were mainly discovered during activities that involved some form of opening the surface.

5.1.2 Site distribution with respect to archaeological site visibility and preservation of material remains

Settlement archaeology faces unique challenges in landscapes like the Central Uplands, where pottery preservation tends to be worse than in lowland areas (Miera et al., 2019, 2022). For instance, early interpretations of the sparse site density in the Vogtland attributed this to the disintegration of fragile material due to local soil conditions (Reinecke, 1956). However, this explanation was disputed after Bronze Age pottery from the Vogtland proved remarkably well-preserved (Coblenz, 1954; Simon, 1989, 1991). Moreover, no clear spatial pattern separates areas with and without pottery in the study area—contrary to what is observed in the Neolithic dataset from the Weiße Elster catchment, where a distinct north-south divide exists between pottery-rich sites in the Northern German Plains and pottery-poor regions in the south (Miera et al., 2022). With this in mind, the low site density recorded for the Bronze Age in the Central Uplands likely reflects genuine settlement patterns rather than preservation biases.

However, there is a correlation between the frequency of sites with pottery on the surface and the intentionality of the discoveries: The few pottery finds that have been discovered on the surface are primarily linked to intentional modes of discovery (Table 3). This could be the result of different factors: among other things, pottery is less well preserved on the surface as it is constantly exposed to the elements and therefore becomes fragmented more rapidly than artifacts made of stone or metal (Geilmann and Spang, 1958; Skibo et al., 1989; Madsen, 1991; Sease, 1994; Fuente, 2008; Odegaard and Watkinson, 2023). As a result, pottery finds from the surface are difficult to identify and therefore primarily discovered by trained archaeologists during field surveys. Radig (1934a), for example, had already stated with a certain amount of ridicule that pottery from Bronze Age settlements was poorly researched and “rather unattractive anyway”. Even in recent times, it has been repeatedly pointed out that the state of research into Bronze Age settlement pottery is still insufficient, as finds are often coarse, poorly fired, and heavily fragmented (Möbes and Speitel, 1984; Coblenz, 1969, 1986b; Ebner, 2001, 2005; Bartelt, 2004; Ganslmeier, 2011). One is inclined to agree with Coblenz's (1950) observation that “most finds are discovered by amateurs, and vessel-rich graves attract far more attention than inconspicuous settlement sherds”.

5.1.3 Culturally intrinsic filters: Bronze Age chronologies in Central Germany

The recorded sites are unevenly distributed over the individual Bronze Age periods. These fluctuations are not exclusively the result of long-term changes within the prehistoric communities. A bias due to culturally intrinsic filters must also be taken into consideration—including our current state of knowledge on the chronological framework of Bronze Age periods in Central Germany.

Even after more than a century and a half of research, the chronology of the Bronze Age in Central Germany still faces significant challenges. To date, no regional chronological system has been developed that covers the entire Bronze Age while simultaneously accounting for local characteristics in Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony, and eastern Thuringia. The closest approximation to this goal has been achieved for the Early Bronze Age, when the Únětice culture is clearly identifiable on a supra-regional scale (Zich, 1996, 2013; Becker et al., 2015; Hubensack, 2018a; Schwarz, 2021; for recent revisions see Stockhammer et al., 2015; Brunner et al., 2020).

Dating the Middle Bronze Age has proven to be particularly complex. Early interpretations suggested a smooth transition from the Únětice culture to the Lusatian culture (Richthofen, 1926; Petsch, 1940), but later work by Grünberg (1943) and Coblenz (1952, 1961a, 1969, 1971, 1987, 1990, 1991) revised this view. Their research demonstrated that the classic Lusatian culture was preceded by a Pre-Lusatian culture, a Hofbuckel pottery phase and the Transitional Period (Figure 3). In addition, west of the Weiße Elster, the Middle Bronze Age is represented by the Tumuli culture. Due to a lack of clear evidence for regional developments in Thuringia, these sites are dated using the chronology developed for Southern Germany (Feustel, 1958a,b, 1972; Kaufmann, 1959, 1992; Neumann, 1968; Fröhlich, 1983).

The absolute dating of the Pre-Lusatian culture, the Hofbuckel pottery phase, and the Transitional Period as well as their synchronization with chronologies from Northern and Southern Germany remain active areas of research (Bahn, 1996; Wagner, 2001; Puttkammer, 2008a,b; Gramsch, 2010; Innerhofer, 2010; Schmalfuß et al., 2022). Additionally, the transition between the Middle Bronze Age and the Urnfield Period presents another layer of complexity for those who apply the chronological framework from Southern Germany. Here, the placement of Bz D—whether as part of the late Middle Bronze Age or the early Urnfield Period—remains contested (Neumann, 1958a, 1968; von Brunn, 1959; Billig, 1968; Donat, 1969; Peschel, 1969, 1978, 1987; Schmidt, 1978; Fröhlich, 1983; Lappe, 1986a,b; Speitel, 1986, 1990).

The situation gets even more complex between 1200 and 800 BCE. Three chronology systems are used simultaneously for this time window in Central Germany. This is due to the fact that several cultural areas meet in this region at that time: Influences from the Nordic Bronze Age, the southern German Bronze Age and the Lusatian culture from eastern Central Europe (Engel, 1933; Agde, 1935, 1939; Schulz, 1939; Mildenberger, 1959). Moreover, there are influences from the Bohemian Knovíz culture in the Vogtland (Coblenz, 1954, 1961b, 1963, 1966; Bouzek, 1967; Bouzek et al., 1966). As icing on the cake, hoard finds and burial customs have shown that there is not only a clash of different chronological systems, but also the formation of regional groups (von Brunn, 1954a,b, 1958, 1960; Billig, 1968; Schmidt, 1967, 1972a,b; Wagner, 1983; Lappe, 1986b; Horst, 1972, 1987, 1989; Schunke, 2004). As a result, the chronology and synchronization of the diverse cultural phenomena from the Urnfield Period in Central Germany are under constant revision (Wagner, 1992, 2004; Heynowski, 2010b; Schmalfuß, 2019).

Due to these ongoing revisions and discussions, a pragmatic approach is needed when comparing site frequencies across different regions in Central Germany, as this analysis requires a standardized chronological framework. For this paper, an absolute chronology was adopted that aligns with the synchronization of Southern, Central, and Northern German chronologies, as outlined by Puttkammer (2008a,b) and Gramsch (2010) (Figure 3). Naturally, a different synchronization of the chronological terminologies may result in different site frequencies. Against this background, the observed site frequencies reflect the outcomes of a model calculation designed to highlight key trends.

5.1.4 Culturally intrinsic filters: material visibility of Bronze Age periods in Central Germany

The archaeological record from the Weiße Elster catchment is characterized by an uneven distribution of Bronze Age sites over time, with certain materials—like pottery or stone and bronze artifacts—dominating finds during specific periods. The balance between settlements, burials, and stray finds, also shifts across periods. These findings indicate that the archaeological record is probably influenced by culturally intrinsic filters. Here, these filters are addressed via the chronological frequency distribution of the material groups and the chronological frequency distribution of the different types of sites.

A bias in the Early Bronze Age dataset caused by material-specific preservation conditions is unlikely, as more than half of all sites from this period have been identified through pottery. This well-preserved pottery serves as a critical resource for dating and classifying the Únětice culture (Neumann, 1929, 1958b; Billig, 1958; Zich, 1996; Schwarz, 2021). Altogether, settlements dominate the distribution of site types, with significantly fewer examples of other site categories (Supplementary Table 2). Notably, most burial sites consist of single burials or small groups of graves, and just under half contain grave goods (Voigt, 1972; Sattler, 2015; Hubensack, 2018a). As a result, these burial sites are often discovered accidentally during construction work, leading to their underrepresentation in the archaeological record. This phenomenon is documented in adjacent study areas as well (Balfanz, 2003; Wegener, 2014; de Vries, 2013). Furthermore, until the 1990s, the entire Early Bronze Age settlement system was a desideratum of Central German research (Voigt, 1972; Peschel, 1994; Walter, 1994; Bartelheim, 1996; Wagner, 2001). Only in the last two and a half decades has the state of research been improved by large-scale projects (Stäuble, 1997, 2019; Huth and Stäuble, 1998; Stäuble and Campen, 1998; Walter et al., 2008; Schunke, 2009; Hansen, 2019; Jurkènas and Spatzier, 2019; Schunke and Stäuble, 2019; Risch et al., 2022). It is important to bear this in mind, as this paper compares archaeological data from studies carried out at different times.

Both settlements and burial sites are underrepresented in the Middle Bronze Age dataset—most sites are stray finds. Notably, metal artifacts are present at three-quarters of all Middle Bronze Age sites, with only a quarter identified based on pottery alone. This reflects a state of research that has long been recognized as inadequate (Feustel, 1972; Fröhlich, 1983; Walter, 1994; Bahn, 1996; Tellenbach, 1996). For example, little is known about the settlement pottery associated with the Tumuli culture and the Pre-Lusatian culture, which means both cultures are primarily documented through bronze artifacts. These objects mostly originate from graves or appear as stray finds (Feustel, 1958a, 1993; Coblenz, 1961a, 1969; Gedl, 1977, 1992; Innerhofer, 2010; Ganslmeier, 2011). The few known settlements from this period have largely been discovered through the dating of pits (Spazier, 2011; Schmalfuß et al., 2018a, 2020). The discovery of building structures and wells at Roitzschjora is therefore particularly rare—a finding made possible by the close monitoring of open-cast mining (Schmalfuß and Tolksdorf, 2016). With regard to the excavations of burial mounds near Rittersrain, Feustel (1993) suggested that settlements from the Middle Bronze Age consisted probably of only one or two households and were therefore very small. Accordingly, the fragmented evidence of Middle Bronze Age settlements likely results from a limited archaeological visibility (Jacob, 1982; Fröhlich, 1983; Bahn, 1996; Wagner, 2001; Balfanz, 2003; Innerhofer, 2010).

Much like the Middle Bronze Age the Transitional Period barely visible in the archaeological record (Feustel, 1958a,b; Kaufmann, 1963; Peschel, 1969, 1978). Within the catchment of the Weiße Elster, this period is mainly documented through pottery finds from burial sites that are dated to Bz D based on parallels with the Knovíz culture from Bohemia or the southern German Urnfield culture (Coblenz, 1954; Peschel, 1969, 1978). This can be attributed to the fact that little is known about the settlement system and the settlement pottery from the Transitional Period (Wirtz, 2000; Ebner, 2001; Hellmund, 2012; Schöneburg, 2012; Schöneburg and Linsener, 2014; Lehmann, 2016; Neubeck, 2017). Consequently, the widespread lack of sites dating to the Transitional Period likely reflects the state of research and not the result of prehistoric settlement processes.

The Urnfield Period is characterized by conditions similar to the Early Bronze Age. The number of settlements exceeds the total number of known burial sites by a factor of two, while pottery is the most common type of material. The dataset is affected by culturally intrinsic filters in that the burial sites are primarily shallow burial fields (Barthel, 1972; Buck, 1972; Schmidt, 1972a,b; Lappe, 1986a). Despite the high number of settlements, little is known about the settlement structures themselves. It is only through the systematic monitoring of construction works along routes and open-cast mines in the last two decades that evidence of settlement areas with building structures has become increasingly more frequent (Schwarzländer, 1996; Bartelt, 2004; Koch and Strobel, 2009; Küßner, 2011; Petzold, 2011; Frehse et al., 2012; Wegener and Strobel, 2012; Conrad et al., 2014; Conrad S. et al., 2016; Conrad M. et al., 2016; Schmalfuß, 2014; Homann and Hubensack, 2016; Hubensack, 2018b; Schmalfuß et al., 2018b; Schöneburg and Ender, 2018; Schöneburg et al., 2020). One reason for the frequent lack of building structures may be that these are generally small and, in addition to post structures, log or sill beam constructions were used, which are difficult to detect in the archaeological record (Coblenz, 1969, 1986b; Möbes and Speitel, 1984; Lindinger, 2010; Knoll, 2018). A further challenge lies in the fact that these are mostly small open settlements, and it was also suggested that the settlements often had to be relocated to compensate for the depletion of agricultural land (Coblenz, 1986b; Heynowski, 2010b).

5.2 Bronze Age land use and settlement dynamics in Central Germany

5.2.1 Site frequencies and spatial affinity of Bronze Age periods

There is a total of nine studies from Central Germany that can be used to contextualize the observations from the Weiße Elster catchment (Figure 9). Minor limitations must be accepted insofar that the Bz D phase is combined with the Ha A and Ha B phases in the archaeological catalogs for the Gothaer Land and the northwest Saxony region (Müller, 1980; Wegener, 2014). Consequently, in this case, it is impossible to determine how many sites date to the Transitional Period.

Figure 9. Pollen profiles and study areas from Central Germany mentioned in the text: (1) Gothaer Land (Müller, 1980), (2) Orlagau (Kaufmann, 1959), (3) Northwest Saxony (Wegener, 2014), (4) Weiße Elster (this paper), (5) Vogtland (Simon, 1989, 1991), (6) Lake Göttwitz (Hilbig, 1993), (7) Ore Mountains (Christl, 2004), (8) former district Riesa-Großenhain (Balfanz, 2003), (9) widening of the Elbe valley at Dresden (de Vries, 2013), (10) widening of the Elbe valley at Dresden and eastern Ore Mountains (Jacob, 1982).

Basically, the supra-regional comparison shows that in most of the study areas a stagnation or a slight decline in site frequencies characterizes the transition to the Middle Bronze Age (Table 5). Among the few exceptions are the Orlagau, northwest Saxony and Lake Göttwitz, where the site frequency increased slightly. In the Transitional Period, the frequency of sites increases in almost all regions, except the Elbe valley near Dresden and the Orlagau. A general increase in the site frequency is characteristic of the Urnfield Period. Only at Lake Göttwitz and near Riesa-Großenhain the opposite trend is observed.

Table 5. Supra-regional comparison of site frequencies per century per 250 km2, calculated based on the chronology for Central Germany (Figure 3).

The dataset for the Bronze Age at the Weiße Elster thus confirms a supra-regional trend in Central Germany that was previously only known from smaller study areas. The closest similarities for the developments in the Weiße Elster catchment are found in adjacent study areas from the Central Uplands. At the same time, differences to the study areas at Lake Göttwitz and Riesa-Großenhain are observed. In the latter regions, there is an increase in the site frequency in the Transitional Period and a decline in the Urnfield Period.

The results of this study represent a novelty, as no quantitative studies on the spatial affinity of Bronze Age sites in Central Germany have been carried out to date. Future studies will show to what extent the observations at the Weiße Elster are a local phenomenon or a reflection of a supra-regional trend. However, Molloy et al. (2023) also observed a drastic change in settlement patterns in the southern Carpathian Basin around 1600 BCE as well. This change may have been triggered by a collapse of the Únětice culture (Shennan, 1993; Kneisel et al., 2013, 2019; Svizzero, 2016, 2018; Großmann et al., 2023).

5.2.2 Bronze Age colonization of low mountain ranges

The settlement dynamics observed at the Weiße Elster confirm earlier observations. These include the finding that most Early Bronze Age sites are located in the Northern German Plains as well as a lack of archaeological evidence indicating a permanent settlement in the Central Uplands during this period (Simon, 1989; Bahn, 1996; Bartelheim, 1996; Christl, 2004; Küßner and Walter, 2019). The same applies to the Middle Bronze Age (Hauswald, 1986; Peschel, 1994; Bahn, 1996; Tellenbach, 1996). The sites from the Transitional Period in the Vogtland are a local peculiarity. So far, there is no other low mountain range region in Central Germany with a comparably high level of settlement activity (Lappe, 1990; Tolksdorf et al., 2019). Excavations in the late 1930s demonstrated that a small settlement enclave had developed during the Bz D phase in the Vogtland (Haase, 1938; Coblenz, 1954, 1986a; Simon, 1991; Christl and Simon, 1995). In this context, it has been pointed out that the Vogtland had a favorable microclimate, which is said to have been enhanced by climatic changes at the end of the Middle Bronze Age (Billig, 1954; Weber and Richter, 1964; Heinrich and Lange, 1969; Simon, 1989, 1991; Christl and Simon, 1995). In contrast to the almost completely empty Ore Mountains (cf. Tolksdorf et al., 2019), the Vogtland is thus considered the “most settlement-friendly upland region in Central Germany” (Christl and Simon, 1995). In addition, the dataset from the Weiße Elster confirms a settlement dynamic for the Urnfield Period that was pointed out early on: During the Ha A and Ha B phases, the settlement density increases considerably and at the same time the low mountain ranges are colonized (Hennig, 1912; Radig, 1934a,b; Pietsch, 1934; Billig, 1954; Peschel, 1969, 1994; Jacob, 1982; Coblenz, 1986b; Hauswald, 1986; Richter, 1986; Lappe, 1990; Simon, 1991; Hilbig, 1993; Nebelsick, 1996; Heynowski, 2010a,b). The intensity of this process and its impact on the environment was even compared to the colonization of the low mountain ranges in the High Middle Ages (Jäger and Ložek, 1978, 1982, 1987).

5.2.3 Site distribution patterns and geostatistics in their regional context

A supra-regional discussion of GIS analyses of Bronze Age land use is only possible based on general remarks as hardly any quantitative analyses have been carried out. Furthermore, the few published studies differ in the general structure of their data and methods (Müller, 1980; Balfanz, 2003; de Vries, 2013; Wegener, 2014). Nevertheless, there is a consensus that Early Bronze Age land use is concentrated on the most fertile soils and that a wider range of less fertile soils was cultivated in the following periods (de Vries, 2013; Wegener, 2014; Küßner and Walter, 2019). This dynamic has been interpreted as an indication of fundamental changes in the economic system, during which the importance of pastoralism is likely to have increased (Jacob, 1982; Müller, 1985; Simon, 1991; Hilbig, 1993; Christl and Simon, 1995; Heynowski, 2010a,b). Moreover, in neighboring study regions it was also observed that Early Bronze Age sites are mainly located on gentle slopes in the lowlands, while higher elevations and steeper slopes are colonized in subsequent periods (Müller, 1980; Balfanz, 2003; de Vries, 2013; Wegener, 2014). In addition, the GIS analyses indicate that the proximity to rivers and streams becomes increasingly important during the Bronze Age and is particularly pronounced between the Transitional Period and the Urnfield Period (Balfanz, 2003). This aspect has often been addressed in earlier studies, but without accompanying statistical analyses (Hennig, 1912; Radig, 1936; Coblenz, 1958; Peschel, 1978; Jacob, 1982; Coblenz, 1986b). This development could be a reaction to the dry climate that has been documented in Central Germany and beyond at this time (Jäger, 2002a,b,c, 2009a; Arosio et al., 2025). However, this trend of increasing proximity to rivers and streams cannot be observed in north-western Saxony and the Dresden Elbe Valley (de Vries, 2013; Wegener, 2014).

5.2.4 Archaeobotanical perspectives on Bronze Age settlement dynamics

The findings on Bronze Age land use are supplemented by archaeobotanical investigations of pollen profiles and analyses of plant remains from settlement pits, hoards and burials (Figure 9). However, the pollen profiles in question from Lake Göttwitz (Jacob, 1957, 1971), Plothen and Pöllwitz (Heinrich and Lange, 1969) were investigated early on, so that the sampling methods no longer meet today's requirements (Schneider, 2025). In addition, their interpretation lacks precise dating. That said, archaeological finds allowed for a provisional dating of Profile III at Lake Göttwitz. The profile indicates a humid climate during the Middle Bronze Age and a drier phase in the Urnfield Period. A high proportion of non-tree pollen from this period also indicates that surrounding forests were thinning during the Transitional Period (Jacob, 1971). This observation is consistent with the archaeological site frequencies in this region (Table 5).

Notably, at Pöllwitz in the Vogtland “a more or less continuous human impact since the Neolithic” was observed (Heinrich and Lange, 1969). However, the human impact on local forests was limited (Heinrich and Lange, 1969; see also Mildenberger's, 1972 critique; Schneider, 2025). Similarly, evidence of Bronze Age land use remains sparse in the Ore Mountains, with only faint traces identified in pollen profiles (Lange et al., 2005; Seifert-Eulen, 2016; Kaiser et al., 2023).

The pollen records from Süßer See are particularly significant for understanding Bronze Age settlement patterns. Here, evidence of pasture farming and cultivation during the Early Bronze Age was confirmed, along with signs of human activity during the Middle Bronze Age (Hellmund et al., 2011; Hellmund and Wennrich, 2014). So far, however, no archaeological finds from the Middle Bronze Age are known from the vicinity of this profile. Therefore, this finding supports the notion that identifying the Middle Bronze Age in the archaeological record is challenging due to culturally intrinsic filters—such as small-scale settlements.