Abstract

The European middle ages (c.500–1500 CE) is often seen as a period of poor oral health and hygiene, as evidenced through artistic, textual, or popular media portrayals. Anthropological analyses have the unique potential to illuminate what medieval mouths were actually like through direct examination of dental and skeletal tissues themselves. In doing so, we can not only document the variability of dental diseases, but also how medieval communities responded to them. This study examines dental pathological lesions (caries, antemortem tooth loss, periodontal disease, periapical lesions, and calculus) and tooth wear from skeletal remains recovered from municipal excavations in Santarém, central Portugal. These assemblages comprise multiple faith communities (Muslims and Christians) from the medieval period (7th−13th c. CE), as based on their distinct funerary treatment. As such, the presence of distinct faith communities buried in adjacent graves offers us the opportunity to furnish a comparative approach to see how health and disease (in this case, of the oral cavity) vary by faith community. Results demonstrated that Islamic females exhibited higher frequencies of antemortem tooth loss, caries, and calculus compared to their Islamic male counterparts, while Christian males exhibited higher caries and calculus frequencies compared to Islamic males. Results and patterns of dental pathological lesions are discussed in terms of religious and temporal differences in diet as well as religious differences in oral healthcare and hygiene as evidenced by ethnohistoric documents, with a particular focus on how keeping a clean mouth was both a physical and spiritual act.

1 Introduction

Human dental remains typically preserve well in archaeological contexts due to their highly mineralized structure, and as a result offer biological anthropologists unique insights into past communities and species (Hilson, 1996). Bioarchaeologists and dental anthropologists routinely examine dental pathological lesions in order to elucidate aspects of past diets and subsistence strategies (Turner, 1979; Cohen and Armelagos, 1984; Powell, 1985; Walker and Hewlett, 1990; Rose et al., 1991; Driscoll and Weaver, 2000; Temple, 2006, 2007; Cohen and Cane-Kramer, 2007; Temple and Larsen, 2007), underlying frailty (DeWitte and Bekvalac, 2010), colonial encounters (Larsen and Milner, 1994; Reeves, 2000; Klaus and Tam, 2010), and sex and gender differences (Lukacs, 1996, 2008, 2011, 2017; Lukacs and Largaespada, 2006; Fields et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2010; Walter et al., 2016; Avery et al., 2019; Trombley et al., 2019) to name only a few, though the axes by which dental remains can be examined are virtually endless.

Here, we examine the relationship between dental pathological lesions and religious identity. While oral health indicators have been analyzed in relation to burial and/or funerary treatments (Redfern et al., 2015; Tornberg, 2016), patterning along religious lines remains a relatively unexplored avenue for bioarchaeological research. While bioarchaeological approaches to religion have gained traction recently (Zakrzewski, 2011, 2015; Inskip, 2013b,a, 2016; Klaus, 2013; Livarda et al., 2018), comparative approaches are even more difficult to come by, in part due to the rare occurrences of multiple religious faith communities employing similar styles of inhumation within relatively contemporaneous and/or geographical contexts. Effectively, bioarchaeologists would require samples where religious funerary treatment of the body is similar enough among religious groups that practice inhumation (thus leading to possible preservation and excavation/analysis by bioarchaeologists), but distinct enough to discern differing religiously-motivated funerary customs. Additionally, the ethics of excavation are also noteworthy, as many surviving stakeholders and descendant communities who share religious affiliation with past faith communities may disapprove of their exhumation and analysis (Colomer, 2014).

The Iberian peninsula offers a unique study area to explore and develop a bioarchaeology of religion, both due to the presence of multiple faith communities within the middle ages, and some contemporary religious stakeholders and local communities voicing interest in (bio)archaeological findings resulting from rescue archaeology (Zakrzewski, 2011), though there are notable exceptions, especially in the case of Jewish burials (Colomer, 2014). Both Spain and Portugal experienced shifting religious and political autonomy throughout the medieval period (c. 500–1492 CE) with Roman, Visigothic, Islamic, Christian, and Jewish communities coexisting within similar geographic and social spheres. The distinct funerary treatments employed by medieval Islamic and Christian communities have allowed funerary archaeologists working within the Iberian peninsula, to distinguish religious identity (at least in death) with relative ease (Chávet Lozoya et al., 2006; Matias, 2008a,b; Ruiz Taboada, 2015; Gonzaga, 2018). Islamic burials during the Iberian middle ages are typically characterized by simple, primary earthen inhumations, a general lack of grave goods/vestments, and with the body deposited in right decubitus position oriented toward the southeast, facing Mecca (Chávet Lozoya et al., 2006; Petersen, 2013). While considerable synchronic and diachronic variation does exist (Chávet Lozoya et al., 2006), many medieval Islamic burials in the Iberian peninsula adhered to relatively prescribed frameworks outlined in the writings of Sunni scholar and jurist Malik ibn Anas (c. 711–795 CE). Conversely, Christian burials in the later middle ages (c. 1300–1500 CE) following the Christian conquests (“Reconquista”) typically employed extended, supine burials, with more variable orientation, inclusion of grave goods, and/or co-mingling via secondary burials and ossuaries (Matias, 2008b; Ruiz Taboada, 2015). Due to increasing urbanization in the later Christian middle ages (Freitas Leal, 2007; Navarro Palazón and Jiménez, 2007; Ruiz Taboada, 2015; Cressier and Lloret, 2020), later Christian cemeteries had the potential to be constructed adjacent to, or even within previously existing Islamic and Jewish cemeteries, facilitating the presence of distinct funerary groups within the same city and/or cemeteries, which can be seen in cities such as Toledo, Spain and Santarém, Portugal (Matias, 2008b; Ruiz Taboada, 2015). The various cemeteries and associated burials excavated throughout Santarém thus offer an opportunity to examine dental pathological lesions in a comparative religious framework. Recent and ongoing research on the medieval Islamic and Christian remains in Santarém has found that religious identity as evidenced by funerary treatment of the body may explain differences in growth and development (Gooderham et al., 2019), paleopathology (Tereso, 2009; Gonçalves, 2010; Graça, 2010; Fernandes, 2011; Rodrigues, 2013; Neves, 2019), atypical dental wear (Rodrigues et al., 2021), decomposition and archaeothanatological signals (Trombley et al., 2024a), and bodily preservation (Trombley et al., 2024b).

We examine here three primary research questions: (1) What was the spatial patterning of oral pathological lesions and health indicators throughout the oral cavities? (2) Are there differences in oral health indicators between sex groups? and (3) Are there differences in oral health indicators between religious groups? We anticipate that dental pathological lesions, especially carious lesions, periodontal disease, calculus, and physiological indicators of mastication such as tooth wear will be patterned predominately in posterior dentition as a result of mechanical demands associated with molars. We hypothesize that females will exhibit increased frequencies in dental pathological lesions as a result of either dietary (Larsen, 1983; Walker and Hewlett, 1990; Kelley et al., 1991; Larsen et al., 1991; Lukacs and Pal, 1993; Lukacs, 1996; Tayles et al., 2000; Temple and Larsen, 2007; Klaus and Tam, 2010; Novak, 2015) or reproductive demands and fertility (Lukacs, 1996, 2008, 2017; Lukacs and Largaespada, 2006; Watson et al., 2010). Finally, we hypothesize that Islamic funerary sub-groups will exhibit lower frequencies in dental pathological lesions than their Christian counterparts due to dietary differences and/or historical practice of oral hygiene.

2 Materials

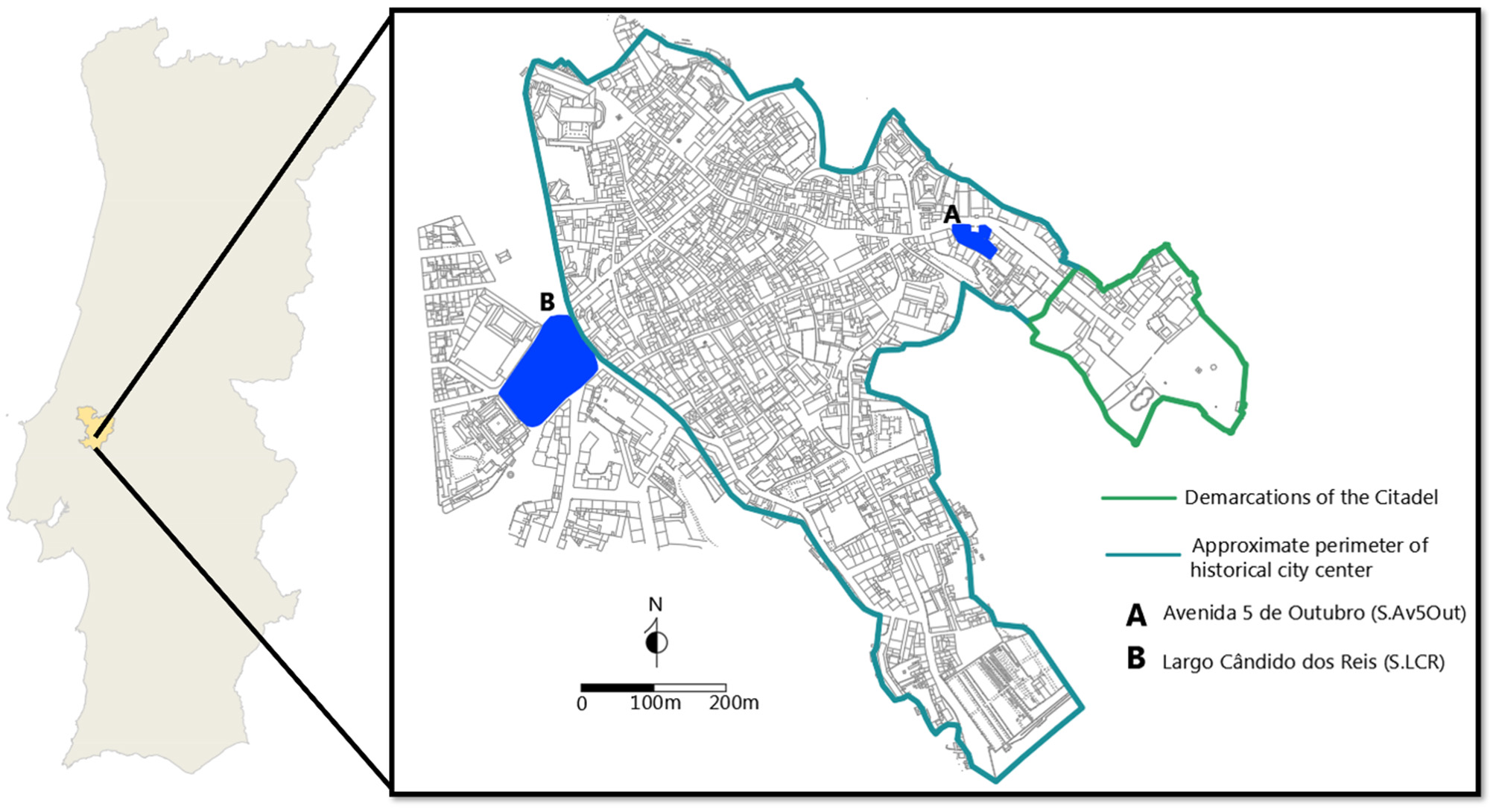

Two principal sites comprise the skeletal materials for this analysis: Avenida 5 de Outubro (S.Av5Out) and Largo Cândido dos Reis (S.LCR), both from the city of Santarém, Portugal. The city of Santarém is located approximately 80 km northeast of Lisbon (Figure 1). Much of the archaeology within the city is done in a salvage municipal framework, excavated by municipal archaeologists or contract archaeologists working with the municipality (Matias, 2018). Both sites were similarly excavated in a salvage framework as a result of urban development within the historical city center. Avenida 5 de Outubro (S.Av5Out) was carried out in two separate salvage excavations, one from August 2007–June 2008 and the second in 2009. Excavations revealed a cemetery complex (n = 164 burials) that spanned from the Roman period through the medieval period (c. 200 BCE –1500 CE), as evidenced by varying funerary deposits (Liberato, 2012). The majority (n = 90) of burials excavated were in the Islamic funerary tradition, characterized by relatively narrow and shallow earthen graves, with the bodies found in right decubitus lateral position (bodies on their right side), with a southwest (head)—northeast (feet) orientation (e.g., Ent. 956), though some minor degrees in orientation were observed (e.g., Ent. 955). Radiocarbon dating on a subsample of medieval burials (n = 5) suggests the cemetery was used between 750–950 CE (Trombley, 2023).

Figure 1

Map of Santarém in relation to Portugal (left) and sites analyzed in present study (right). Left image courtesy of the Câmara Municipal de Santarém Carta Arqueológica (p. 13–14), drawing by Inês Serafim. Right image drawn by Trent Trombley, based on drawings by Liberato and Santos (2017) and study of walled fortifications by de Cardoso (2003).

The site of Largo Cândido dos Reis (S.LCR, Municipal site no. 74) was carried out as a salvage-municipal excavation between July 12, 2004 and September 30, 2005. Situated approximately ~830 m from the citadel (alcáçova) and some ~616 m from Avenida 5 de Outubro, the site was carried out in response to urban development projects, and comprised two principle necropoles: one Islamic (with an area of at least 9,6812 meters) and the other a late medieval transitioning into early-modern Christian cemetery, likely associated with the ancient hermitage of Santa Maria Madalena (13th c. C.E.) and now integrated into the Centro de Saúde for the city (Matias, 2008a,b). While radiocarbon dating on a subsample of Islamic burials (n = 6) suggest the site was used for Islamic funerary processions between 1000 and 1100 CE, the later Christian cemetery was used possibly until the seventeenth century with the establishment of the Third Order of Saint Francis which largely replaced and integrated the previous hermitage of Santa Maria. A total of 639 (n = 422 Islamic, n = 217 Christian) burials were excavated at the site, though this likely represents a smaller portion of the total cemetery currently superimposed by modern urban development.

3 Methods

3.1 Analytical procedures

Age-at-death was estimated based on progressive degeneration of various skeletal elements, with particular focus on the pubic symphysis (Brooks and Suchey, 1990) and auricular surface (Lovejoy et al., 1985). Age-at-death was conservatively categorized as 18–29 years, 30–49 years and 50+ years to avoid some of the problematic assessments of age in older individuals (Jackes, 2000), especially given poor preservation observed at the site (Trombley et al., 2024b). In order to maximize sample size comparisons, the younger two age-at-death categories were collapsed to foster comparisons of 18–49 years and 50+ years both within and between funerary groups and sex.

Sex was estimated by similarly emphasizing morphological differences within the pelvic girdle, focusing on the Phenice complex (ventral arc, sub-pubic angle, sub-pubic concavity) (Phenice, 1969; Ascàdi and Nemeskèri, 1970; Brothwell, 1981; Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994), preauricular sulcus, and greater sciatic notch (Walker, 2005). Additionally, numerous sex-related features of the skull were also used to help increase accuracy of sex estimation (Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994). Finally, numerous studies throughout both medieval Portuguese samples (Cunha, 1994) as well as contemporary samples (Cardoso, 2000; Wasterlain, 2000) have found sexual dimorphism to be present in limb proportions and skeletal elements, which were also implemented as a means of bolstering sex estimation. In this case, the calcaneus (CM1) and talus (TM1) maximum length measurements following the procedures outlined in Silva (1995) were used, given their ability to bolster sex estimation in Portuguese reference samples. Numerous individuals were indeterminate in terms of age but estimable by sex, as a result of sexually dimorphic elements being preserved which could yield an estimation of sex accompanied by a lack of age-estimable elements preserving (e.g., pubic symphysis). This monotone feature ultimately resulted in male and female sub-samples containing individuals of indeterminate age, but were included to maximize sample sizes.

Statistical comparisons were made primarily utilizing a two-tailed log-likelihood ratio test, also called the G test. Similar to a χ2 test, the G test examines the ratio of observed to expected counts, but is more conservative in its estimation of statistical differences in smaller samples sizes, when observed counts are much larger than expected counts (Klaus and Tam, 2010, p. 598). In the event that expected counts were less than five, a Fisher's Exact test with an α = 0.05 was used instead. To avoid issues in family-wise error rate (FWER) stemming from multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was employed to help reduce Type I errors. While the Bonferroni correction is more conservative than other correction factors (e.g., Šidák), we employ here a limited number of multiple comparisons (maximum of two for any given sample), and such a correction can help conservatively correct for more spurious effects while still maintaining highly significant effects.

3.2 Antemortem tooth loss

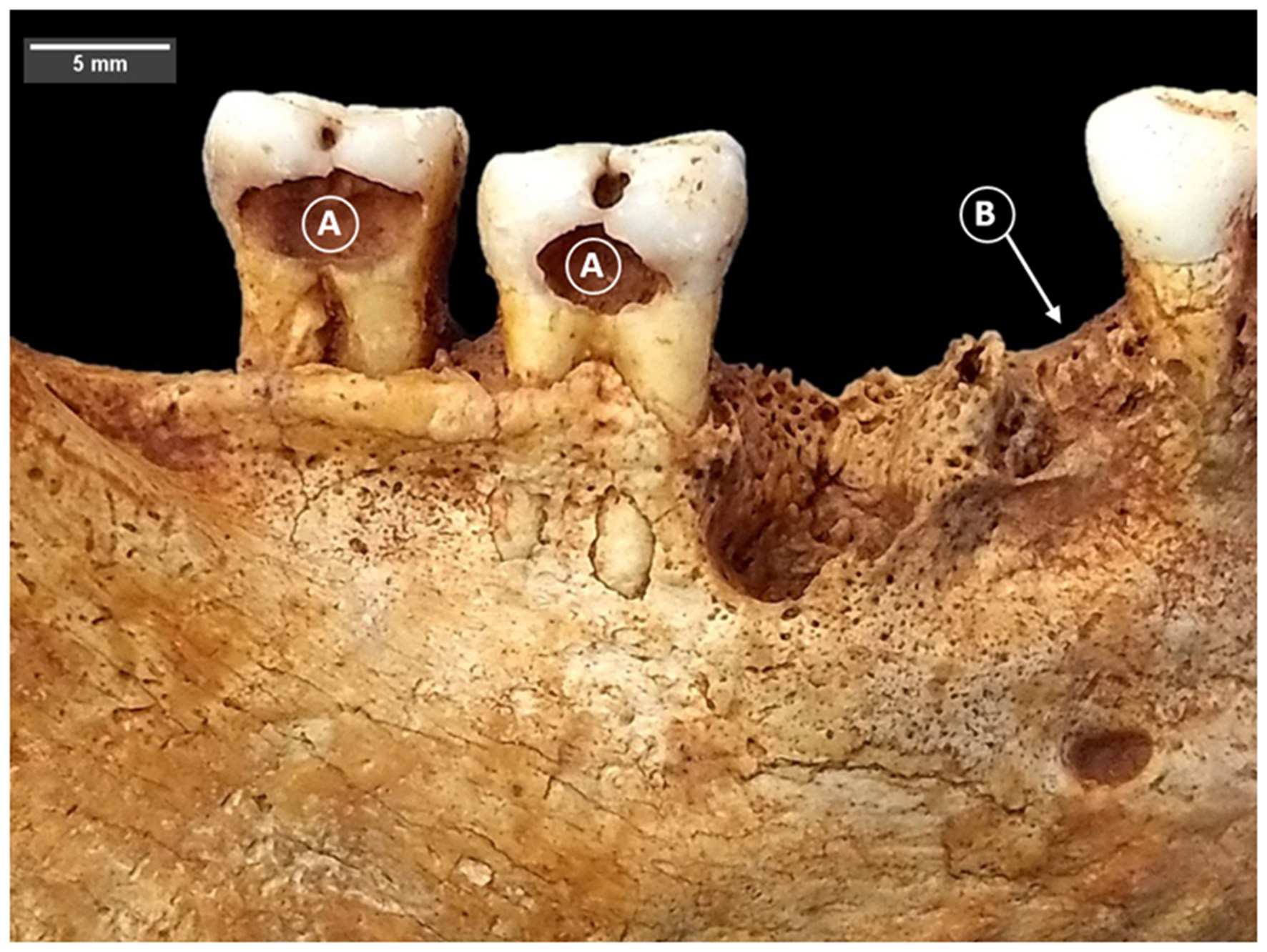

Teeth can be lost antemortem due to a variety of reasons. Commonly cited factors in bioarchaeology are (1) advanced carious lesions that penetrate the pulp-chamber and eventually compromise the integrity of gomphoses resulting in loss; (2) advanced tooth wear which can subsequently expose the pulp-chamber to cavitation; (3) intentional ablation or removal, and (4) trauma (Lukacs, 2007). Notably, teeth can also be lost as a result of increasing alveolar resorption accompanying severe gingivitis and periodontitis (Clarke and Hirsche, 1991; Hildebolt and Molnar, 1991; Varrela et al., 1995; Whittaker and Molleson, 1996). As gum disease results in resorption of the alveolar margin, teeth can continue to erupt slowly in order to continue masticatory capabilities, ultimately subjecting them to higher likelihood of cariogenesis below the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) and subsequent loss. AMTL is typically observed in skeletal remains by the characteristic alveolar resorption and remodeling of the alveolar sockets (Figure 2). AMTL was calculated by scoring the number of teeth lost antemortem over the total number of observable loci.

Figure 2

Carious lesions (A) and antemortem tooth loss (B) in LCR 183. Photo: T. Trombley.

3.3 Dental caries

Carious lesions were identified by their characteristic demineralization of the enamel and/or dentine surface, ranging from a pin-prick to the complete destruction of a crown's surface (Figure 2). In order to calculate the frequency of carious lesions, a variety of calculations have been proposed. Traditionally, and frequently in bioarchaeological literature, caries frequency is calculated using the following:

Where b refers to the number of observed teeth with caries, a refers to the total number of observed teeth, multiplied by 100. While informative, this crude frequency only reports observed carious lesions in relation to remaining observable teeth and fails to account for the relationship between carious lesions and antemortem tooth loss. As a result, numerous scholars have suggested that it is unrealistic, as both antemortem and post-mortem tooth loss causes the observed (i.e., bioarchaeological) frequency “to deviate from its real value” (Duyar and Erdal, 2003, p. 58; see also Brothwell, 1963; Erdal and Duyar, 1999; Hilson, 1996; Kerr et al., 1988; Lukacs, 1992, 1995, 2011; Moore and Corbett, 1971; Whittaker et al., 1981). In essence, many teeth that were lost antemortem likely had carious lesions, or were lost as a result of severe cavitation, to the point where many teeth affected by caries are never seen by the researcher. The issue is exacerbated in samples where antemortem tooth loss rates are high, where observed caries frequency can thus severely under-represent true caries frequency (Lukacs, 1992, 1995).

As such, we utilized the caries correction factors employed by Duyar and Erdal to supplement crude prevalence:

where, b refers to observed caries, a refers to the total number of observed teeth, c refers to the number of teeth lost antemortem, and p refers to the proportion of teeth with pulp exposure to those without, except the subscript for each variable classifies the tooth as anterior (e.g., b1) or posterior (e.g., b2). The results from the CCF2 can be used to calculate the proportional correction factor (PCF), which multiplies the anterior and posterior caries rates by their respective proportion of teeth within the ‘typical' dental arcade (3/8 for anterior, 5/8 for posterior):

3.4 Tooth wear

Tooth wear is the process by which enamel and dentine are removed from teeth through mechanical contact, either with one another (attrition) or with exogenous materials such as coarse, gritty, and/or fibrous foodstuffs (abrasion) (Lucas, 2004; Kaidonis, 2008). Differentiating between attritional and abrasion tooth wear is often difficult without the aid of advanced microscopy (Kaidonis et al., 1993; Kaidonis, 2008). As a result, most bioarchaeologists analyze tooth wear as part of a broader mechanical process to glean information on dietary, mechanical, or non-alimentary activities of past communities (Larsen, 1998). Tooth wear can significantly affect a tooth's susceptibility to cariogenesis, as sufficient wear can either expose the pulp-chamber and underlying dentine to acidogenic and cariogenic bacteria.

Given the differing morphology between anterior dentition and molars, tooth wear is often scored separately, though both through the use of ordinal scales (Scott, 1979; Smith, 1984). Smith's (1984) scale is often more desirable for anterior dentition, whereas Scott's (1979) method is more sensitive to scoring molar wear since it separates the occlusal surfaces into quadrants and scores each quadrant separately, before aggregating the scores for any given molar. Frequently, when statistical comparisons for tooth wear are made between differing sub-groups, molar scores are averaged separately from anterior dentition (Klaus and Tam, 2010; Trombley et al., 2019). Thus, despite the lack of granularity in dental wear using the Smith (1984) method for scoring molars, subsequent averaging, especially multiple times, of Scott's (1979) scoring technique may well override its proposed resolution. This study employed only the Smith (1984) scoring method for both anterior and posterior dentition, in order to maintain consistency within author methodologies, and to avoid excessive averaging. Additionally while dental wear between groups can be done by employing a t-test (Klaus and Tam, 2010; Trombley et al., 2019), the biological differences when compounded with effect size between wear scores can inflate differences, especially since dental wear scores are not normally distributed. As such, we chose to visualize the results here rather than rely on a statistical comparison.

3.5 Calculus

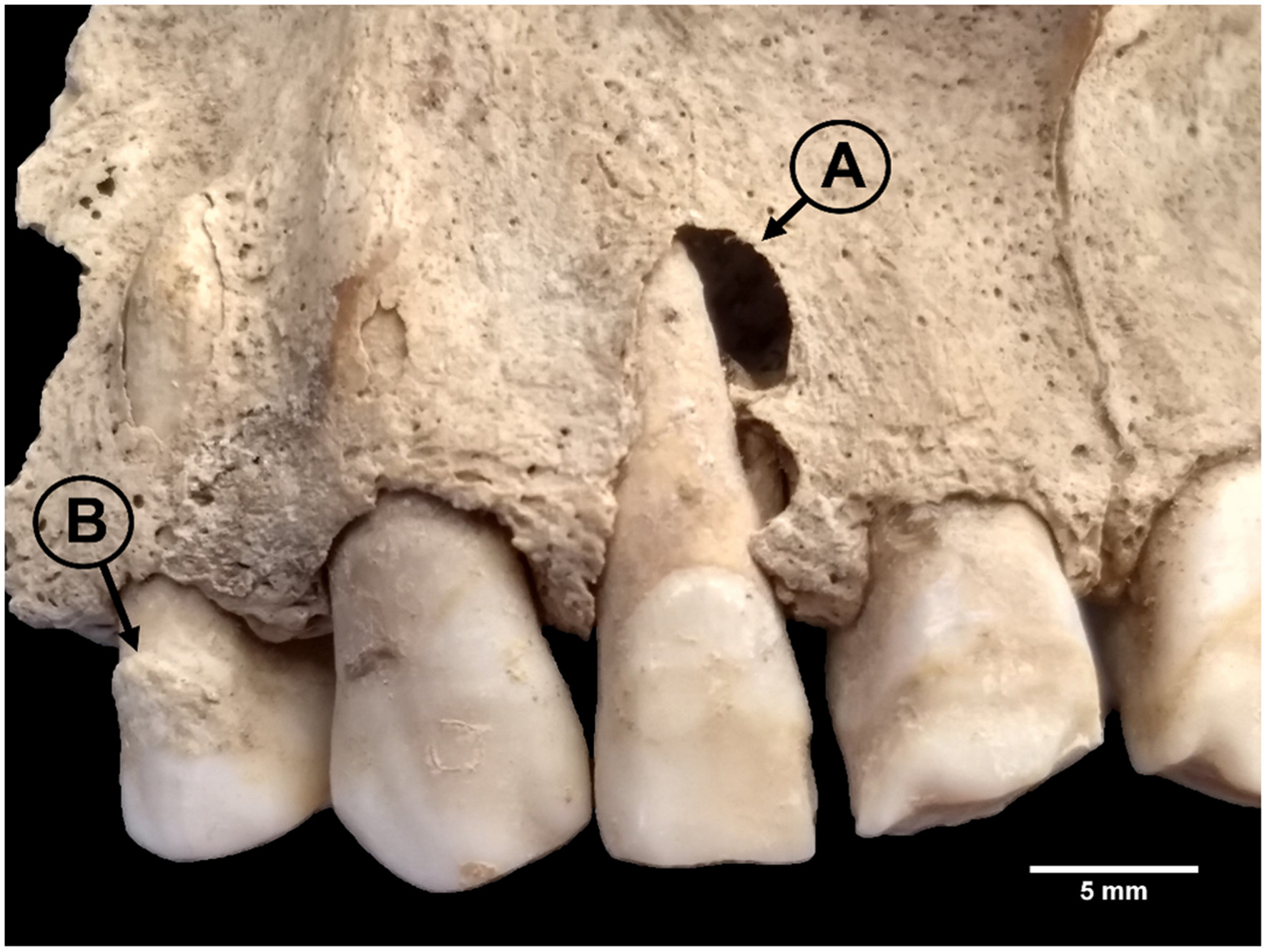

Calculus is a mineralized form of plaque which forms as a result of salivary minerals (principally, calcium-phosphate) precipitating to leave a hardened substance adhering to the tooth. While the formation of plaque and calculus are impacted by a variety of factors, oral hygiene and the employment of dentifrices has been observed to minimize formation and accretions (Jepsen et al., 2011). Lack of oral hygiene and consistent use of dentifrices often results in moderate to severe plaque (and subsequently, calculus) buildup, which can be additional risk factors for gingivitis, alveolar recession, and periodontitis (White, 1997; Jepsen et al., 2011). In skeletal remains, calculus is often observed as anything from a small deposit to a larger ‘shelf' of mineralized plaque adhering to one or more surfaces of the teeth. Calculus was scored using the three-stage ordinal scale proposed by Brothwell (1981), while also scoring its specific location on the tooth's surface (Figure 3). If calculus was present along multiple dental surfaces, the location was scored as “multiple.”

Figure 3

Periapical lesion (A) and calculus (B) in LCR 238. Photo: T. Trombley.

3.6 Periapical lesions

Though commonly referred to as ‘abscesses' or ‘abscess cavities,' the more precise term used here is ‘periapical lesions', which can refer to granuloma, cysts, and/or abscesses. Periapical lesions form when cavities penetrate a tooth's pulp chamber before draining out of the apical foramen. While the means by which pulp chambers become exposed can vary, from carious lesions to extreme dental wear, severe infection can become pyogenic, which results in a drainage of pus, localized inflammation, and the formation of a granuloma, or mass of inundated inflammatory cells such as modified macrophages and lymphocytes (Dias and Tayles, 1997; Ogden, 2008, p. 295). The granuloma can result in osteoclastic activity, which resorbs adjacent bone structures, skeletally manifesting as an acute periapical lesion observable by a cavity of resorbed bone, typically located on the buccal side (Hillson, 2008). Necrotic pulp cavities and granulomas/cysts can become infected via foodstuffs or blood-borne infection (Trowbridge and Stevens, 1992; Abbott, 2004), which can facilitate the formation of an abscess. Periapical lesions were scored only in the event that there was a clear, observable drainage channel of necrotic resorption associated with the apices of one or more tooth roots and >2 mm in diameter (Ogden, 2008, p. 297) (Figure 3). A total number of 1,020 Islamic male and 925 Islamic female loci, and 672 Christian male and 488 Christian female loci were scored for periapical lesions.

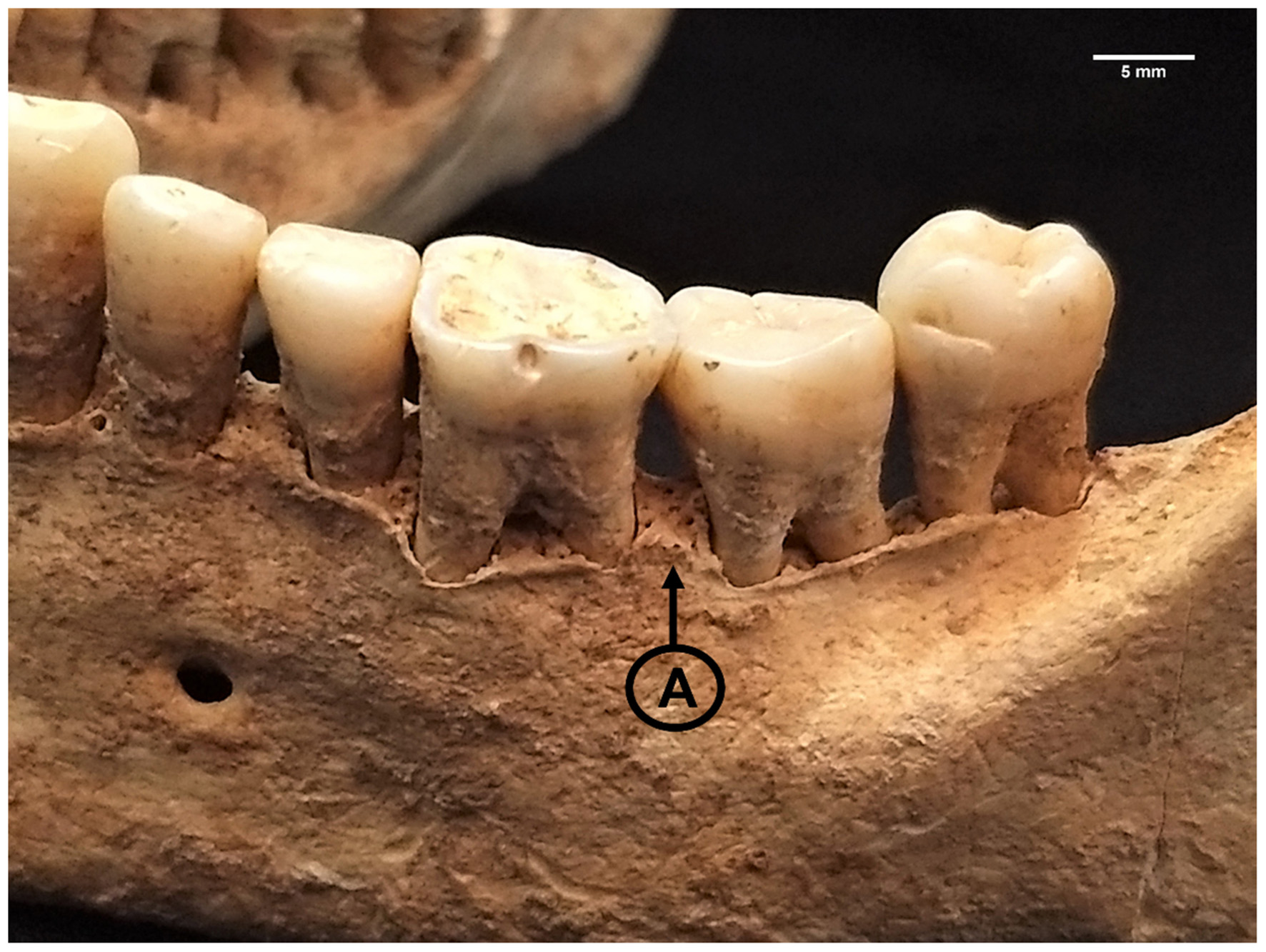

3.7 Periodontal disease

Periodontal disease is an infectious disease whereby the gingival margin experiences degeneration as a result of bacterial infection (Armitage, 1995; Hernández et al., 2011). While its more benign condition, gingivitis, is characterized by inflammation of the gums and affects adults who do not practice regular oral hygiene (Albandar and Rams, 2002; Eke et al., 2015), periodontitis results in loss of irreplaceable bone in the alveolar margin. The etiology of periodontal disease is still not entirely understood, but molecular studies suggest that alveolar resorption appears to be the product of the oral biofilm experiencing dysbiosis, where pathogenic bacterial communities interact with other microbial communities and complexes to facilitate an increase in fermentable proteins, thus weakening periodontal ligaments and resorbing underlying alveoli (Hajishengallis and Lamont, 2012; Abusleme et al., 2013).

In bioarchaeology, the presence of periodontal disease is typically characterized by porosity, exposure of the underlying trabecular bone, and reduction of the alveolar margin (Kerr, 1988, 1991; Clarke and Hirsche, 1991; Larsen, 1997). In contrast to metric methods which score periodontal disease using a distance threshold (e.g., 2 mm or greater) between the alveolar crest and cemento-enamel junction (CEJ), pioneering work by Kerr (1988, 1991) and others (Costa, 1982; Ogden, 2008) instead proposed a more detailed, ordinal scale which analyzes each of the inter-dental septa individually for texture, architecture, porosity, and contouring. While more time-intensive and dependent on good preservation of alveolar margins, the Kerr method allows one to distinguish between healthy gums (score = 1) from forms of gingivitis (score = 2), localized periodontitis (score = 3), and quiescent or rampant periodontitis (scores 4 and 5; Figure 4). While Ogden (2008, p. 289) cautions that gingivitis cannot be detected in skeletal remains as the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone are not affected, Kerr's (Kerr, 1988, 1991) score of 2 often is attributed to pre-periodontitis.

Figure 4

Interdental septa (A) showing signs of periodontitis (score 5) due to jagged, irregular architecture, sloping, and microporosity accompanying alveolar recession in LCR 432. Photo: T. Trombley.

3.8 Stable isotope analysis

To further contextualize the dietary results, a small pilot sample of individuals (n = 18) were analyzed for radiogenic isotope analysis as part of an Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) funded Archaeology of Portugal Fellowship, which subsequently permitted stable isotope analysis. Analysis was carried out only on collagen for 13C and 15N, which reflect plants and protein sources, respectively (Minagawa and Wada, 1984; Schoeninger and DeNiro, 1984). Samples were processed and analyzed at the Keck Carbon Cycle AMS facility at the University of California, Irvine. Samples were decalcified in 1N HCl, before being gelatinized at 60 °C, and finally ultra-filtered to select high molecular weight fraction (>30 k Da). δ13C and δ15N values were measured to a precision of <0.1l and <0.2l, respectively, on aliquots of ultra-filtered collagen, using a Fisons NA1500NC elemental analyzer/Finnigan Delta Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometers (IRMS). All results were corrected for isotopic fractionation according to Stuiver and Polach (1977) which δ13C values measured on prepared graphite using the AMS spectrometer. All samples met minimum acceptable collagen yield according to standard metrics (%N, %N, C:N). Values from the stable isotope analysis can be seen in the Supplementary information.

4 Results

4.1 Antemortem tooth loss (AMTL)

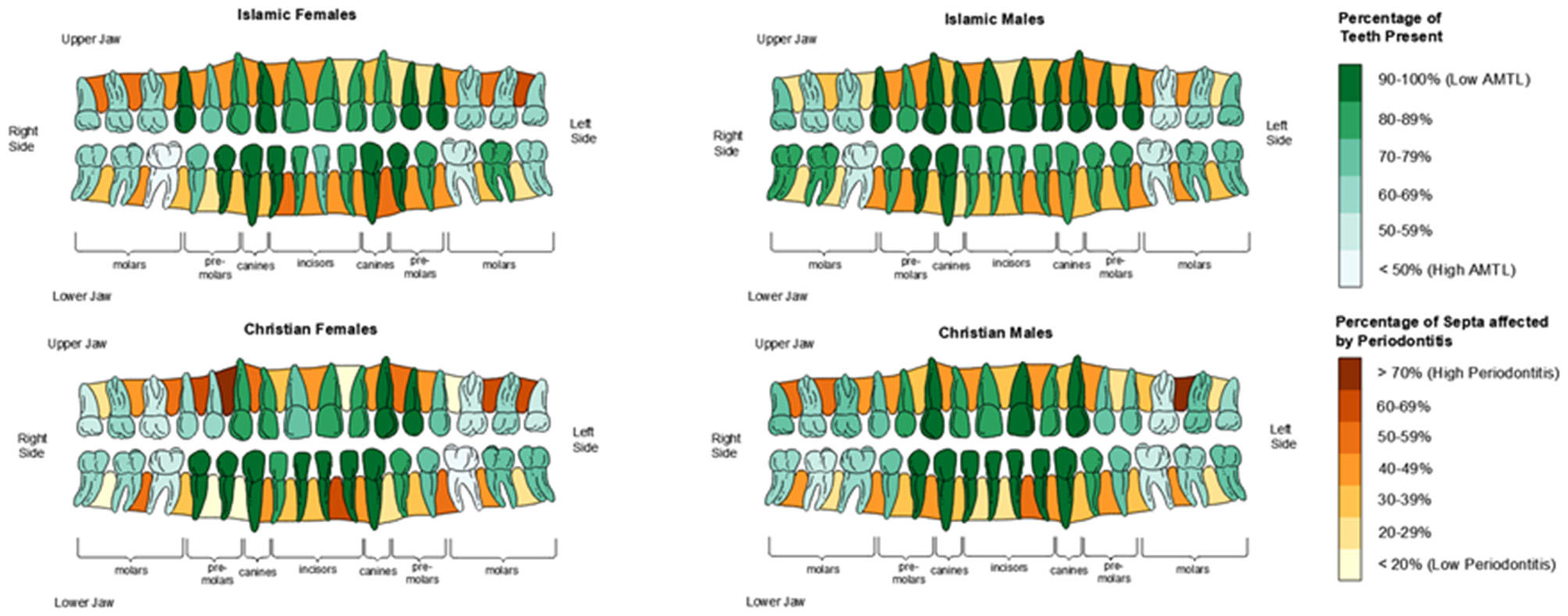

The distribution of loci by site, sex, age, and funerary group can be seen in Table 1. Dental remains associated with older individuals (50+ years) exhibited significantly higher rates of AMTL compared to younger (18–49 years) individuals, regardless of funerary group or sex (Table 2). However, when age- and sex-separated groups were compared by funerary group (e.g., Islamic 50+ year females vs. Christian 50+ year females), no differences were observed (Table 3). When analyzed by anterior and posterior dentition, all groups (Islamic Females, Islamic Males, Christian Females, Christian Males) showcased extreme AMTL in their posterior dentitions compared to anterior dentitions (Table 4). When analyzed by tooth type (Incisors, Canines, Premolars, Molars) and by sex, Islamic females showcased no significant differences in AMTL when compared to their Islamic male counterparts (SI 1). Christian females showed significantly higher AMTL in incisors compared to their male counterparts (G = 4.07; p = 0.04). Islamic females showcased significantly higher rates of AMTL compared to their Islamic male counterparts (G = 5.22, p = 0.04; Table 5). Christian females and males were not significantly different in AMTL. When total AMTL rates of same-sex groups were compared by funerary group, neither Christian females nor males were significantly different than their Islamic counterparts (Table 6). Visual results by sex and funerary group, alongside periodontitis, can be seen in Figure 5.

Table 1

| Indicator | Sex | Age | Islamic | Christian | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Av5Out | LCR | Total | Av5Out | LCR | Total | |||

| AMTL | Females | 18–29 | 96 | 141 | 210 | – | 107 | 107 |

| 30–49 | 182 | 62 | 244 | – | 80 | 192 | ||

| 50+ | 225 | 159 | 384 | – | 221 | 221 | ||

| Indet. | – | 60 | 60 | – | 80 | 80 | ||

| Total | 503 | 422 | 925 | – | 488 | 488 | ||

| Males | 18–29 | 64 | 64 | 128 | – | 64 | 64 | |

| 30–49 | 128 | 220 | 348 | – | 265 | 265 | ||

| 50+ | 89 | 152 | 241 | – | 170 | 170 | ||

| Indet. | 32 | 271 | 303 | – | 173 | 173 | ||

| Total | 313 | 707 | 1020 | – | 672 | 672 | ||

| Caries | Females | 18–29 | 93 | 135 | 228 | – | 95 | 95 |

| 30–49 | 125 | 31 | 156 | – | 65 | 65 | ||

| 50+ | 160 | 101 | 261 | – | 114 | 114 | ||

| Indet. | – | 78 | 78 | – | 69 | 69 | ||

| Total | 378 | 345 | 723 | – | 343 | 343 | ||

| Males | 18–29 | 94 | 63 | 157 | – | 78 | 78 | |

| 30–49 | 105 | 173 | 278 | – | 208 | 208 | ||

| 50+ | 43 | 102 | 145 | – | 102 | 102 | ||

| Indet. | 29 | 228 | 257 | – | 135 | 135 | ||

| Total | 271 | 566 | 837 | – | 523 | 523 | ||

| Tooth wear | Females | 18–29 | 92 | 136 | 228 | – | 95 | 95 |

| 30–49 | 124 | 28 | 152 | – | 65 | 65 | ||

| 50+ | 158 | 101 | 259 | – | 113 | 113 | ||

| Indet. | – | 50 | 50 | – | 69 | 69 | ||

| Total | 374 | 315 | 689 | – | 342 | 342 | ||

| Males | 18–29 | 62 | 63 | 125 | – | 63 | 63 | |

| 30–49 | 103 | 174 | 227 | – | 203 | 203 | ||

| 50+ | 42 | 102 | 144 | – | 102 | 102 | ||

| Indet. | 28 | 227 | 255 | – | 132 | 132 | ||

| Total | 235 | 566 | 801 | – | 500 | 500 | ||

| Periodontal disease | Females | 18–29 | 79 | 106 | 185 | – | 85 | 85 |

| 30–49 | 81 | 10 | 91 | – | 56 | 56 | ||

| 50+ | 70 | 42 | 112 | – | 75 | 75 | ||

| Indet. | – | 13 | 13 | – | 40 | 40 | ||

| Total | 230 | 171 | 401 | – | 256 | 256 | ||

| Males | 18–29 | 75 | 43 | 118 | – | 68 | 68 | |

| 30–49 | 75 | 137 | 212 | – | 148 | 148 | ||

| 50+ | 22 | 80 | 102 | – | 88 | 88 | ||

| Indet. | 21 | 138 | 159 | – | 73 | 73 | ||

| Total | 193 | 398 | 591 | – | 377 | 377 | ||

| Calculus | Females | 18–29 | 91 | 131 | 222 | – | 94 | 94 |

| 30–49 | 107 | 30 | 137 | – | 74 | 74 | ||

| 50+ | 106 | 99 | 205 | – | 112 | 112 | ||

| Indet. | – | 78 | 78 | – | 68 | 68 | ||

| Total | 304 | 338 | 642 | – | 351 | 351 | ||

| Males | 18–29 | 88 | 63 | 151 | – | 46 | 46 | |

| 30–49 | 89 | 171 | 260 | – | 205 | 205 | ||

| 50+ | 21 | 101 | 122 | – | 102 | 102 | ||

| Indet. | 29 | 255 | 294 | – | 110 | 110 | ||

| Total | 227 | 590 | 817 | – | 466 | 466 | ||

| Periapical lesions | Females | 18–29 | 96 | 141 | 210 | – | 107 | 107 |

| 30–49 | 182 | 62 | 244 | – | 80 | 192 | ||

| 50+ | 225 | 159 | 384 | – | 221 | 221 | ||

| Indet. | – | 60 | 60 | – | 80 | 80 | ||

| Total | 503 | 422 | 925 | – | 488 | 488 | ||

| Males | 18–29 | 64 | 64 | 128 | – | 64 | 64 | |

| 30–49 | 128 | 220 | 348 | – | 265 | 265 | ||

| 50+ | 89 | 152 | 241 | – | 170 | 170 | ||

| Indet. | 32 | 271 | 303 | – | 173 | 173 | ||

| Total | 313 | 707 | 1020 | – | 672 | 672 | ||

Sample distribution of dental loci/teeth analyzed for dental pathological lesions by site, sex, age, and funerary group.

Av5Out, Avenida 5 de Outubro and LCR, Largo Cândido dos Reis.

Table 2

| Analysis | Funerary group | Sex | 18–49 years | 50+ years | G | P-value | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | ||||||

| AMTL† | Islamic | Females | 66/444 | 14.86 | 119/380 | 31.32 | 20.26 | <0.01 | More AMTL in older age |

| Males | 52/453 | 11.48 | 84/229 | 36.68 | 37.07 | <0.01 | More AMTL in older age | ||

| Christian | Females | 16/176 | 9.09 | 88/202 | 43.56 | 36.60 | <0.01 | More AMTL in older age | |

| Males | 50/322 | 15.53 | 51/153 | 33.33 | 11.76 | <0.01 | More AMTL in older age | ||

| Caries, uncorrected‡ | Islamic | Females | 53/384 | 13.80 | 44/261 | 16.86 | 0.82 | 0.73 | No difference |

| Males | 31/435 | 7.13 | 18/145 | 12.41 | 3.03 | 0.99 | No difference | ||

| Christian | Females | 28/250 | 11.20 | 22/170 | 12.94 | 0.23 | 0.99 | No difference | |

| Males | 34/346 | 9.83 | 23/168 | 13.69 | 1.32 | 0.50 | No difference | ||

| Caries, corrected | Islamic | Females | 116/450 | 25.86 | 123/38 | 27.29 | 2.40 | 0.24 | No difference |

| Males | 56/487 | 11.55 | 68/229 | 29.72 | 23.14 | <0.01 | More corrected caries in older age | ||

| Christian | Females | 44/266 | 16.54 | 102/257 | 39.69 | 20.25 | <0.01 | More corrected caries in older age | |

| Males | 76/396 | 19.19 | 74/219 | 33.79 | 9.42 | <0.01 | More corrected caries in older age | ||

| Calculus§ | Islamic | Females | 204/359 | 56.82 | 132/205 | 64.39 | 0.77 | 0.38 | No difference |

| Males | 237/411 | 57.66 | 53/122 | 43.44 | 2.43 | 0.12 | No difference | ||

| Christian | Females | 152/255 | 59.61 | 117/164 | 71.34 | 1.28 | 0.26 | No difference | |

| Males | 172/300 | 57.33 | 84/167 | 50.30 | 0.64 | 0.43 | No difference | ||

| Periodontal disease? | Islamic | Females | 108/374 | 28.88 | 47/180 | 26.11 | 0.26 | 0.61 | No difference |

| Males | 106/450 | 23.56 | 54/180 | 30.00 | 1.61 | 0.20 | No difference | ||

| Christian | Females | 82/300 | 27.33 | 93/174 | 53.45 | 14.11 | <0.01 | More periodontal disease in older age | |

| Males | 81/390 | 20.77 | 79/240 | 32.92 | 6.66 | <0.01 | More periodontal disease in older age | ||

Age-at-death comparisons of dental pathological lesions separated by funerary group and sex.

All p-values presented are Bonferroni corrected.

Number of discernable teeth lost antemortem/Number of observable loci.

Number of observed and/or estimated carious lesions/Total number of teeth observed. See text for details on calculating corrected vs. uncorrected prevalence.

Number of discernable interdental septa with scores > 2/Total number of observable interdental septa.

Bold signifies statistically significant p-value at the α = 0.05 level.

Table 3

| Analysis | Age | Sex | Christian | Islamic | G | P-value | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | ||||||

| AMTL† | 18–49 | Females | 16/176 | 9.09 | 66/444 | 14.86 | 3.05 | 0.16 | No difference |

| Males | 50/322 | 15.53 | 52/453 | 11.48 | 2.04 | 0.31 | No difference | ||

| 50+ | Females | 88/202 | 43.56 | 119/380 | 31.32 | 3.95 | 0.09 | No difference | |

| Males | 51/153 | 33.33 | 84/229 | 36.68 | 0.22 | 0.99 | No difference | ||

| Caries, uncorrected‡ | 18–49 | Females | 28/250 | 11.20 | 53/384 | 13.80 | 0.72 | 0.79 | No difference |

| Males | 34/346 | 9.83 | 31/435 | 7.13 | 1.54 | 0.43 | No difference | ||

| 50+ | Females | 22/170 | 12.94 | 44/261 | 16.86 | 0.92 | 0.68 | No difference | |

| Males | 23/168 | 13.69 | 18/145 | 12.41 | 0.09 | 0.99 | No difference | ||

| Caries, corrected | 18–49 | Females | 44/266 | 16.54 | 116/450 | 25.87 | 5.5 | 0.04 | More Islamic female corrected caries |

| Males | 76/396 | 19.19 | 56/487 | 11.55 | 7.47 | 0.01 | More Christian male corrected caries | ||

| 50+ | Females | 102/257 | 39.69 | 123/380 | 27.29 | 1.69 | 0.39 | No difference | |

| Males | 74/219 | 33.79 | 68/229 | 29.72 | 0.45 | 0.99 | No difference | ||

| Calculus§ | 18–49 | Females | 152/255 | 59.61 | 204/359 | 56.82 | 0.13 | 0.99 | No difference |

| Males | 172/300 | 57.33 | 237/411 | 57.66 | 0.01 | 0.99 | No difference | ||

| 50+ | Females | 117/164 | 71.34 | 132/205 | 64.39 | 0.39 | 0.99 | No difference | |

| Males | 84/167 | 50.30 | 53/122 | 43.44 | 0.48 | 0.97 | No difference | ||

| Periodontal disease? | 18–49 | Females | 82/300 | 27.33 | 108/374 | 28.88 | 0.11 | 0.99 | No difference |

| Males | 81/390 | 20.77 | 106/450 | 23.56 | 0.60 | 0.88 | No difference | ||

| 50+ | Females | 93/174 | 53.45 | 47/180 | 26.11 | 12.26 | <0.01 | More periodontal disease in older Christian females | |

| Males | 79/240 | 32.92 | 54/180 | 30.00 | 0.21 | 0.99 | No difference | ||

Funerary comparison of dental pathological lesions separated by age-at-death and sex.

All p-values presented are Bonferroni corrected.

Number of discernable teeth lost antemortem/Number of observable loci.

Number of observed and/or estimated carious lesions/Total number of teeth observed. See text for details on calculating corrected vs. uncorrected prevalence.

Number of observed teeth with calculus/Total number of teeth observed.

Number of discernable interdental septa with scores > 2/Total number of observable interdental septa.

Bold signifies statistically significant p-value at the α = 0.05 level.

Table 4

| Analysis | Funerary group | Sex | Anterior | Posterior | G | P-value | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | ||||||

| AMTL† | Islamic | Female | 42/316 | 13.29 | 149/564 | 26.42 | 21.77 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior AMTL |

| Male | 31/361 | 8.59 | 139/611 | 22.75 | 34.44 | <0.01 | No Significantly more posterior AMTL | ||

| Christian | Female | 18/160 | 11.25 | 91/292 | 31.16 | 24.51 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior AMTL | |

| Male | 13/239 | 5.44 | 112/393 | 28.50 | 57.91 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior AMTL | ||

| Caries, uncorrected‡ | Islamic | Female | 22/288 | 7.64 | 79/435 | 18.16 | 17.11 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior caries |

| Male | 17/342 | 4.97 | 62/495 | 12.53 | 14.55 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior caries | ||

| Christian | Male | 9/231 | 3.90 | 51/272 | 18.75 | 29.11 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior caries | |

| Female | 1/142 | 0.7 | 28/201 | 13.93 | - | <0.01* | Significantly more posterior caries | ||

| Caries, corrected | Islamic | Female | 59/330 | 18.02 | 202/584 | 34.64 | 30.27 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior caries |

| Male | 27/373 | 7.33 | 158/634 | 24.96 | 54.91 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior caries | ||

| Christian | Female | 19/160 | 11.88 | 119/292 | 40.75 | 44.86 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior caries | |

| Male | 22/244 | 9.02 | 156/384 | 40.61 | 82.21 | <0.01 | Significantly more posterior caries | ||

| Calculus§ | Islamic | Female | 173/252 | 68.65 | 203/390 | 52.05 | 17.64 | <0.01 | Significantly more anterior calculus |

| Male | 203/339 | 59.88 | 197/478 | 41.21 | 27.81 | <0.01 | Significantly more anterior calculus | ||

| Christian | Female | 97/145 | 66.90 | 107/203 | 52.71 | 7.09 | <0.01 | Significantly more anterior calculus | |

| Male | 137/213 | 64.32 | 121/250 | 48.40 | 11.89 | <0.01 | Significantly more anterior calculus | ||

| Periodontal disease? | Islamic | Female | 53/131 | 40.46 | 107/270 | 39.63 | 0.03 | 0.87 | No difference |

| Male | 73/201 | 36.32 | 138/390 | 35.38 | 0.05 | 0.82 | No difference | ||

| Christian | Female | 41/100 | 41.00 | 60/156 | 38.46 | 0.16 | 0.69 | No difference | |

| Male | 52/139 | 37.41 | 93/238 | 39.08 | 0.10 | 0.75 | No difference | ||

Anterior vs. Posterior frequencies of dental pathological lesions by funerary group and sex.

Number of discernable teeth lost antemortem/Number of observable loci.

Number of observed and/or estimated carious lesions/Total number of teeth observed. See text for details on calculating corrected vs. uncorrected prevalence.

Number of observed teeth with calculus/Total number of teeth observed.

Number of discernable interdental septa with scores > 2/Total number of observable interdental septa.

P-value resulting from a Fisher's Exact test (ɑ = 0.05) due to expected counts being less than 5.

Bold signifies statistically significant p-value at the α = 0.05 level.

Table 5

| Analysis | Funerary group | Female | Male | G | P-value | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | |||||

| AMTL† | Islamic | 191/880 | 21.70 | 170/972 | 17.49 | 5.22 | 0.02 a | Significantly more AMTL in females |

| Christian | 109/452 | 24.12 | 125/632 | 19.78 | 3.61 | 0.06a | No difference | |

| Caries, uncorrected‡ | Islamic | 101/723 | 13.97 | 79/837 | 9.44 | 7.78 | <0.01 * | Significantly more caries in females |

| Christian | 29/343 | 8.45 | 60/503 | 11.93 | 2.67 | 0.10 | No difference | |

| Caries, corrected | Islamic | 262/914 | 28.67 | 186/1007 | 18.47 | 27.88 | <0.01 * | Significantly more caries in females |

| Christian | 138/452 | 30.53 | 178/628 | 28.34 | 0.61 | 0.44 | No difference | |

| Calculus§ | Islamic | 376/642 | 58.57 | 400/817 | 48.96 | 13.36 | <0.01*a | Significantly more calculus in females |

| Christian | 204/348 | 58.62 | 258/463 | 55.72 | 0.68 | 0.82 | No difference | |

| Periapical lesions¶ | Islamic | 14/925 | 1.51 | 15/1020 | 1.47 | 0.01 | 0.99a | No difference |

| Christian | 14/488 | 2.87 | 7/422 | 1.66 | 1.51 | 0.44a | No difference | |

| Periodontal disease? | Islamic | 160/401 | 39.90 | 211/591 | 35.70 | 1.79 | 0.36a | No difference |

| Christian | 101/256 | 39.45 | 145/377 | 38.46 | 0.06 | 0.99a | No difference | |

Sex comparison of frequencies of dental pathological lesions.

Number of discernable teeth lost antemortem/Number of observable loci.

Number of observed and/or estimated carious lesions/Total number of teeth observed. See text for details on calculating corrected vs. uncorrected prevalence.

Number of observed teeth with calculus/Total number of teeth observed.

Number of discernable loci with periapical lesions/Total number of observable loci.

Number of discernable interdental septa with scores > 2/Total number of observable interdental septa.

P-value adjusted with a Bonferroni correction.

Bold signifies statistically significant p-value at the α = 0.05 level.

Table 6

| Analysis | Sex | Islamic | Christian | G | P-value | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | N observed/ total | Crude frequency (%) | |||||

| AMTL† | Females | 191/880 | 21.70 | 109/452 | 24.12 | 3.50 | 0.12a | No difference |

| Males | 170/972 | 17.49 | 125/632 | 19.78 | 1.33 | 0.50a | No difference | |

| Caries, uncorrected‡ | Females | 101/723 | 13.97 | 29/343 | 8.45 | 7.00 | 0.02 | Significantly more caries in Islamic females |

| Males | 79/837 | 9.44 | 60/503 | 11.93 | 2.06 | 0.30 | No difference | |

| Caries, corrected | Females | 262/914 | 28.67 | 138/452 | 30.53 | 0.51 | 0.95 | No difference |

| Males | 186/1007 | 18.47 | 178/628 | 28.34 | 21.40 | <0.01 | Significantly more caries in Christian males | |

| Calculus§ | Females | 376/642 | 58.57 | 204/348 | 58.62 | 0.00 | 0.99a | No difference |

| Males | 400/817 | 48.96 | 258/463 | 55.72 | 5.42 | 0.04a | Significantly more calculus in Christian males | |

| Periapical lesions¶ | Females | 14/925 | 1.51 | 14/488 | 2.87 | 2.90 | 0.18a | No difference |

| Males | 15/1020 | 1.47 | 7/422 | 1.67 | 0.07 | 0.99a | No difference | |

| Periodontal disease? | Females | 160/401 | 39.90 | 101/256 | 39.45 | 0.01 | 0.99a | No difference |

| Males | 211/591 | 35.70 | 145/377 | 38.46 | 0.75 | 0.80a | No difference | |

Funerary comparison of frequencies of dental pathological lesions.

Number of discernable teeth lost antemortem/Number of observable loci.

Number of observed and/or estimated carious lesions/Total number of teeth observed. See text for details on calculating corrected vs. uncorrected prevalence.

Number of observed teeth with calculus/Total number of teeth observed.

Number of discernable loci with periapical lesions/Total number of observable loci.

Number of discernable interdental septa with scores > 2/Total number of observable interdental septa.

P-value adjusted with a Bonferroni correction. Bold values in the p-value column: 0.02, <0.01, and 0.04a

Figure 5

Visualized ‘heat map' of antemortem tooth loss (AMTL) and periodontitis by sex and funerary group. For teeth, dark green corresponds to high likelihood of tooth being present (low AMTL) and white corresponds to higher likelihood of tooth being lost antemortem. For interdental septa, dark brown corresponds to high prevalence of periodontitis for that septum, where tan/buff corresponds to low likelihood of periodontitis being present in that interdental septum.

4.2 Caries

The distribution of teeth analyzed for caries can be seen in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in crude caries prevalence between age groups (18–49 years vs. 50+ years) regardless of funerary group or sex (Table 2). Only when the correction factor was implemented did older Islamic males, older Christian males, and older Christian females differ from their younger counterparts. However, when these age- and sex-separated groups were compared by funerary group (e.g., 50+ Islamic males vs. 50+ Christian males), no significant differences were observed in the older age group (Table 3).

Groups analyzed showed higher uncorrected rates of posterior carious lesions compared to anterior ones, regardless of sex or funerary group, all of which were statistically significant (Table 4). In both uncorrected and corrected measures, Islamic females showcased higher frequency of carious lesions than their male counterparts, with only anterior uncorrected carious lesion being non-significant (Table 5). No significant sex differences were found for the Christian funerary group, regardless of uncorrected or corrected analyses. Islamic females showed higher frequency of uncorrected anterior and total carious lesions compared to their Christian female counterparts, but the differences were not significant once corrected (Table 6). Christian males showed significantly higher uncorrected posterior caries compared to Islamic males, and corrected posterior and total caries compared to Islamic males. When compared by location, Islamic females showcased higher frequency of carious lesions found on smooth surfaces and roots compared to their Islamic counterparts (SI 10). Christian males exhibited higher proportion of caries on cervical surfaces compared to Christian females, while all other differences were non-significant.

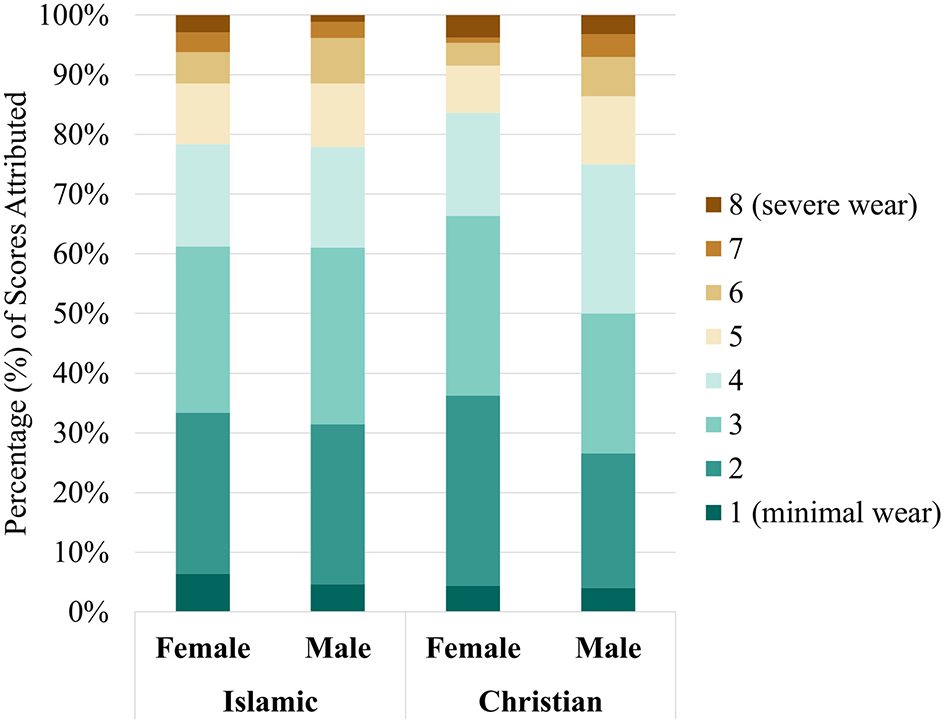

4.3 Dental wear

Results from the dental wear can be seen visually in Figure 6. The majority of scores (75.00% - 83.62%), regardless of funerary or sex group, were relatively minor in wear severity (Scores < 5).

Figure 6

Dental wear scores by sex and funerary group.

4.4 Calculus

The distribution of teeth analyzed for calculus can be seen in Table 1. No differences were observed between age- and sex-separated groups (Tables 2, 3). When analyzed by anterior and posterior dentition, all groups (Islamic Females, Islamic Males, Christian Females, Christian Males) showcased higher rates of calculus in their anterior dentition compared to posterior dentition (Table 4). When analyzed by tooth-type (Incisors, Canines, Premolars, Molars) and by sex, Islamic females showcased significantly higher frequency of molars affected with calculus (G = 12.85, p < 0.01) and total calculus (G = 13.36, p < 0.01) when compared to their Islamic male counterparts (SI 2). In the Christian funerary group, no significant sex differences in calculus by tooth type was observed.

When calculus severity was analyzed by sex and separated by funerary (SI 3), Islamic females showed significantly higher rates of score = 1 (G = 6.05, p = 0.03) and score = 3 (Fisher's Exact p = 0.02) compared to Islamic males. Christian females and males similarly showcased a majority of score = 1, but higher frequency of score = 2 and score = 3 compared to their Islamic counterparts. When calculus severity was analyzed by funerary group and separated by sex (SI 4) both Islamic females and males showed significantly higher frequency of score = 1 compared to their Christian counterparts (Females: G = 17.57, p < 0.01; Males: G = 34.56, p < 0.01 respectively). However, both Christian females and males showcased higher frequency of scores = 2 (Females: G = 38.33, p < 0.01; Males: G = 26.25, P < 0.01) and males showed increased scores of 3 compared to their Islamic counterparts.

When calculus location was analyzed by sex and separated by funerary group (SI 5), Islamic males showed a significantly higher frequency of lingual (G = 6.09, p = 0.03) whereas females exhibited higher interproximal calculus (G = 7.55, p = 0.01). No other significant sex differences were found for the Islamic funerary group. Christian females exhibited higher calculus across multiple locations than their male counterparts (G = 17.61; p < 0.01). When calculus location was analyzed by funerary group and separated by sex (SI 6), Islamic females showed higher frequencies than their Christian female counterparts for every surface except for buccal. Conversely, Christian males showed significantly higher frequency of lingual calculus compared to their Islamic male counterparts (G = 20.74, p < 0.01). When total calculus rates of same-funerary groups were compared by sex, only Islamic females had significantly higher frequency of calculus compared to Islamic males (Table 5). When total calculus rates of same-sex groups were compared by funerary group, both Christian females and Christian males showcased higher rates of calculus than their Islamic female and male counterparts, but only males showed a significant difference (Table 6). When sexes were collapsed, no significant differences were observed.

4.5 Periodontal disease

The distribution of interdental septa analyzed for periodontitis can be seen in Table 1. While no difference in periodontal disease scores were observed between age groups (18–49 years vs. 50+ years) in the Islamic funerary group, both Christian females and males exhibited more periodontal disease in the older age groups compared to their younger counterparts (Table 2). When age- and sex-separated groups were compared by funerary group (Table 3), only older (50+) Christian females exhibited more periodontal disease than their Islamic female counterparts (G = 12.26, p < 0.01).

Visualized ‘heat maps' of periodontal disease prevalence by each interdental septa and demographic category (age, sex, funerary group) can be seen in Figure 5. Periodontal scores separated by funerary group and sex showed that only two Islamic males showcased exclusively healthy (category 1) septa (SI 7). The remaining 93 individuals analyzed showcased signs of either gingivitis or periodontitis (score > 2). When analyzed by score (SI 8), Islamic males showed a sizeable presence (43.32%) of category 1 (healthy) interdental septa, while Islamic females (37.41%), Christian females (38.67%) and Christian males (36.07%) all showcased comparatively lower frequency of healthy septa. All groups analyzed showed relatively similar frequencies of septa affected by gingivitis (category 2), ranging from 20.98% to 25.46%. When categories 3, 4 and 5 were collapsed for total periodontitis ranging from acute burst to larger angular defects, all groups showed approximately 35.70–39.90% of septa affected. When analyzed by anterior and posterior septa, no significant differences were found for either sex or funerary group (Table 4). When sexes were compared within funerary groups for total periodontal disease (Table 5), for either funerary group. When funerary groups were compared between same-sex sub-groups, no differences were observed (Table 6). When maxillary and mandibular septa were compared by sex and funerary group, only Christian females showed significantly higher frequency of periodontitis in maxillary septa (47.27%) compared to mandibular ones (33.56%; SI 9). No other significant differences between maxillary and mandibular septa was found for Islamic females, males, or Christian males.

4.6 Periapical lesions

The distribution of periapical lesions analyzed can be seen in Table 1. When intra-funerary groups were analyzed by sex (Table 3), no significant differences in periapical lesions were observed. Similarly, when sexes were compared by funerary group (Table 4), no significant differences were observed.

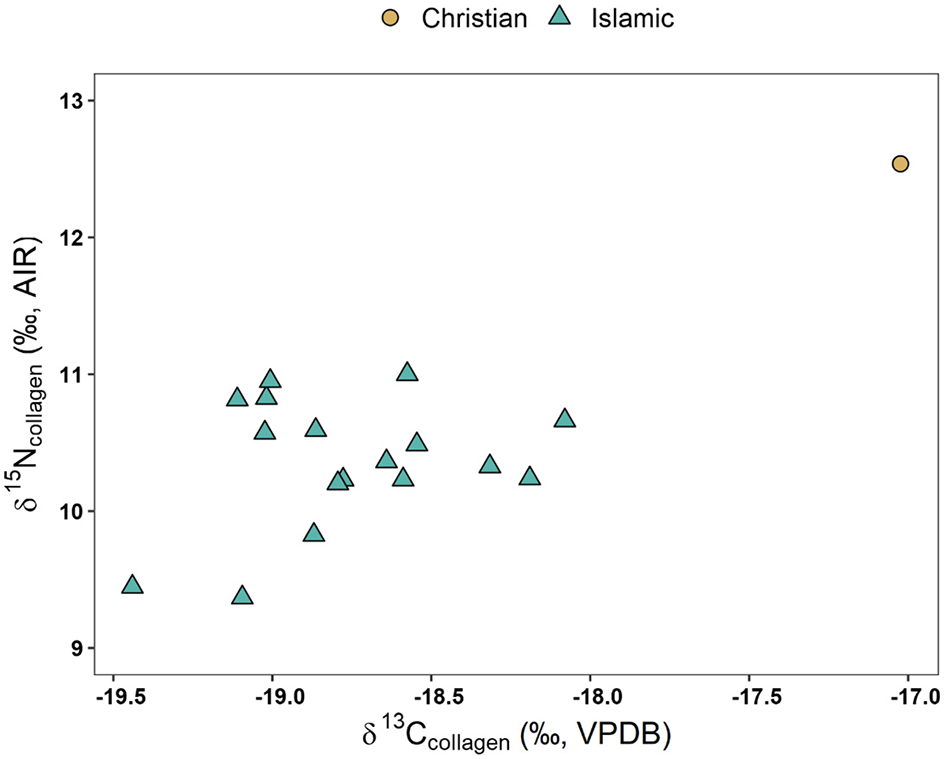

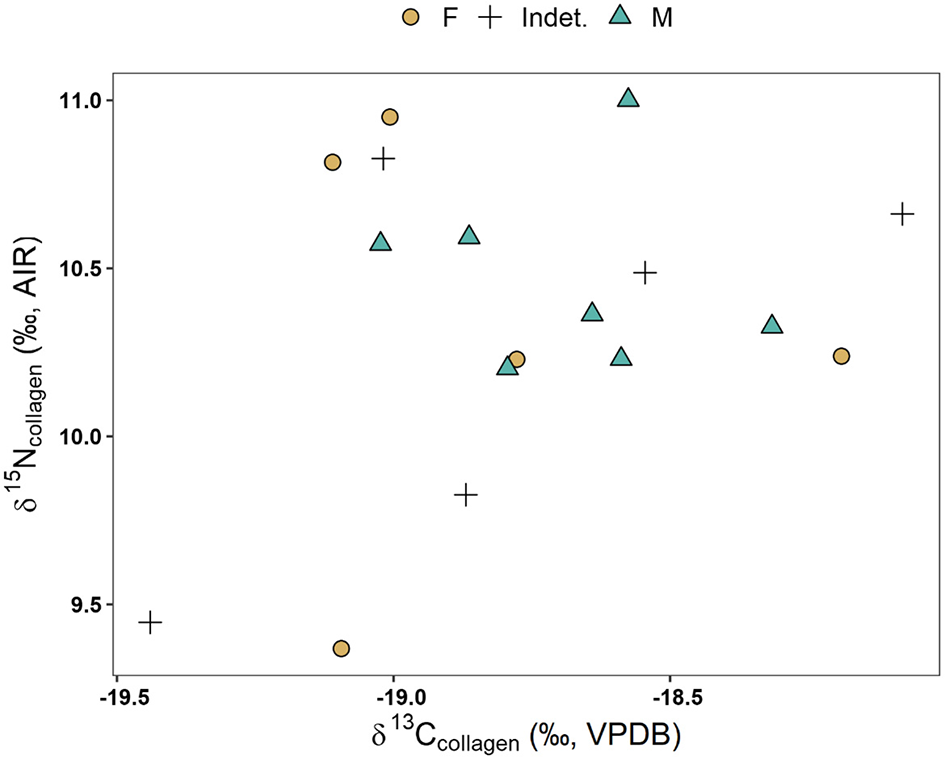

4.7 Stable isotope analysis

Results from the pilot stable isotope analysis can be seen in SI 11. Figure 7 depicts the δ13C and δ15N biplot by funerary group, while Figure 8 depicts a similar biplot but only focusing on the Islamic individuals and separated by sex.

Figure 7

Stable isotope results by funerary group.

Figure 8

Stable isotope results by sex in Islamic group only.

5 Discussion

5.1 Food, religion, and landscapes in medieval Portugal

Since oral health is impacted by diet, we begin by situating dental pathological lesions in context of the dietary landscape of Medieval Portugal. Agriculturally, central Portugal was focused on a cereal complex comprising predominately of wheat (Triticum), barley (Hordeum vulgare) and rye (Secale cereale) (Gonçalves, 2004). During the Islamic period (c. 711–1149), numerous Arabic references to the success and proliferation of buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) suggest it become one of the more dominant cultigens throughout the central and later middle ages (Marques, 2021). The arrival of Islam additionally resulted in the intensification and proliferation of arboriculture and fruit gardens, and subsequent drying of particular fruits such as figs (Ficus), grapes (Vitis), and plums (Prunus) (Marques, 2021). Orchards containing stonefruits (Prudus), gourds (Cucurbitaceae), apples (Malus), pomegranates (Lythraceae), lemons (Citrus limon), and bitter oranges (Citrus x aurantium) were particularly prevalent throughout the Islamic period, and accompanied by careful hydrological innovation and irrigation such as the development of water wheels, watermills, and aquifers (Marques, 2021). Agriculturally, the region was known for its rich fluvial floodplains and cultivation of cereals, wine, and olive oil (Custódio et al., 1996; Gonçalves, 2004). While sugar cane (Saccharum) was introduced into the Iberian peninsula by Arabic traders in the tenth century (García-Sánchez, 1990, 1995), it's initial introduction was specific to the Spanish Mediterranean coast due to its specific ecosystem (coastal, calcareous soil, frost-free, etc.) suitable for sugar cane cultivation (Jiménez-Brobeil et al., 2022). While sugar cane production was expanded under the Nasrid period (1230–1492 CE), the cultivation was generally limited to the southern coast of Spain such as Almería, Granada, and Málaga (Jiménez-Brobeil et al., 2022). As such, to our knowledge, sugar cane was never introduced to central Portugal during this period.

Unfortunately, there has been a dearth of published archaeobotanical work on Roman and medieval Iberian sites (Peña-Chocarro et al., 2019), though there is promise for emerging patterns. For instance, archaeobotanical remains dating to the Islamic period from a salvage excavation in the Alentejo city of Évora (Coradeschi et al., 2017) found high prevalence of fruits, such as grapes (Vitis vinifera), figs (Ficus carica), blackberries (Morus sp.) and possible melon seed (Cucumis sativus/melo), and cereals such as barley (Hordeum vulgare), wheat (Tricitum aestivum/durum) and oats (Avena sp.). Undoubtedly, there is exciting potential for the integration of archaeobotanical findings with other information on foodways and diet in medieval Portuguese contexts. Much of our understanding of medieval foodways in Iberia stems from traditional ethnohistorical accounts (García-Sánchez, 1983, 1986, 1996) supplemented with archaeology. Cooking and food preparation during the Islamic period seemed to employ clay containers over wood hearths, emphasizing stews and soups with various legumes such as fava beans (Fabacae), lentils (Lens), and chickpeas (Cicer arietinum) in addition to faunal bones as thickening/flavoring agents (Marques, 2021). Islamic traders not only seemed to have introduced citruses, rice, and sorghum to the peninsula, but also reinvigorated cultivation of millet and alfalfa which had been generally de-emphasized during the Visigothic period (García-Sánchez, 1995).

Livestock farming formed an important economic activity throughout the peninsula (Estaca-Gómez et al., 2018), with documentary evidence suggesting sheep and goat being preferred in the Islamic period followed by beef, fowl, and rabbit, while the Christian conquests shifted to an emphasis on pig, cattle, and marine resources as well as bread and wine (García-Sánchez, 1986; Waines, 1994, 2010; Marques, 2021). Sheep and pigs seemed to have been generally more emphasized than cattle throughout the later medieval period, such that Gonçalves (2004) suggests nearly every peasant household had a pig. The twelfth to thirteenth century CE saw a burgeoning in bread production as Christian conquests swept throughout Portugal, with variation in bread recipes as a result of regional and climatic variability in cereal cultivation (Marques, 2021). Secondary crops such as sorghum and millet seem to have been introduced, and can be seen both archaeobotanically as remains and isotopically due to their C4 photosynthetic pathway. Interestingly, times of scarcity following the Christian conquests utilized sorghum and millet as fallback crops (Marques, 1987). Faunal remains from zooarchaeological analyses seem to generally confirm these documents, with Islamic faunal assemblages showing a general dearth of pig, whereas Christian contexts exhibit higher frequencies of pig and occasionally cattle compared to their Islamic counterparts (García-García, 2017; Grau-Sologestoa, 2017). Notably, both Islamic and Christian contexts exhibit high prevalence of sheep/goat remains, likely as a result of their broad utility in not only providing meat, but also wool and milk (Grau-Sologestoa, 2017). While little published zooarchaeological studies have been conducted within the city of Santarém, analyses of faunal remains from the alcáçova (citadel) carried out by Davis (2003) showcased that most faunal remains in the Islamic period belonged to terrestrial mammalian domesticates, principally sheep/goat (Caprines sp.), cattle (Bos), pigs (Sus), deer (Cervus), equids (Equus), rabbit (Leporidae), cat (Felis), and dog (Canis), as well as avifauna (Gallus/Numida/Phasianus) and some fish remains (Acipenseridae, Mugilidae, Babus, Sparus, and Pagrus). Excavations of a sizeable silo (6 m3) near the Sant Francis convent in association with the Islamic period has uncovered further dietary information (Ramalho et al., 2001). While not as large as other silos excavated near the alcáçova, this silo would have been sufficient to feed a family of 8-10 for approximately 2 years. Faunal remains of sheep (Ovis aries/Capra hircus), cattle (Bos taurus), horse (Equus caballus), rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), bivalves (Easthonia rugosa; Pecten maximus) as well as indeterminate fish and bird remains were all recovered from the silo, with ovi-caprids comprising the majority (56.6%) of determinable remains (Ramalho et al., 2001, p. 160). Given the systematic presence of cut marks, fractures, and occasional charring, the authors posit these remains likely reflect dietary remains. Notably, there was a distinct lack of pig (Sus) remains found in this silo assemblage, contrasting with the larger temporal assemblage recovered from the alcáçova assemblage (Davis, 2003) but adhering to the general trend observed elsewhere in Iberian Islamic contexts.

Marine sources appeared to have held a varied and debated influence in medieval Iberia. While Portugal's proximity to marine resources on the Atlantic and Mediterranean, paired with extensive river and lakes, would presume a strong presence of marine and aquatic foodstuffs, there is a surprising lack of both historical and zooarchaeological data to confirm this. For instance, ethnohistoric accounts from Arab authors seemed to have debated the benefits of fish consumption, with only ~4%−10% of recipes listed in Andalusian cookbooks employing fish (García-Sánchez, 1986). However, the Qu'ran generally permits the consumption of fish (halal), referenced in 5:96:

“It is lawful for you to hunt and eat seafood, as a provision for you and for travelers. But hunting on land is forbidden to you while on pilgrimage. Be mindful of Allah to Whom you all will be gathered.”

Fishing likely comprised an activity for the laity living in littoral zones as a means of meat/protein procurement, but did not receive the comparative attention of chroniclers as terrestrial meat (García-Sánchez, 1983). Historically, the Christian period emphasized a scaling up of off-shore fishing and emphasis on fish protein, ranging from the laity to the high courts and royalty (Coelho, 1995; Coelho and Santos, 2016). Fish also became an important resource throughout Christendom during fasting and lent in abstaining from terrestrial (‘warm blooded') meat, with 150 days per year listed as fasting dates in the liturgical calendar (Adamson, 2004; Grumett and Muers, 2010; Pérez-Ramallo et al., 2022). Unfortunately, there have generally been a dearth of fish remains recovered in faunal assemblages largely due to recovery techniques (Grau-Sologestoa, 2017, p. 190; footnote 2). Other than a refuse pit in Silves (Davis et al., 2008), the aforementioned assemblage from the citadel of Santarém (Davis, 2003) is one of the few published recoveries of fish and marine remains from the medieval period.

Finally, dietary histories are becoming clearer via the burgeoning application of stable isotope analysis. While most isotopic studies that have been conducted on the medieval period in the peninsula have been limited to Spain (Alexander et al., 2015, 2019; Salazar-García et al., 2016; Guede et al., 2017; Lubritto et al., 2017; Pickard et al., 2017; Dury et al., 2019; Jordana et al., 2019; López-Costas and Müldner, 2019; MacKinnon et al., 2019; Pérez-Ramallo et al., 2022), preliminary publications are beginning to emerge for medieval Portugal as well (Curto et al., 2019; Toso et al., 2019, 2021; MacRoberts et al., 2020, 2024). The emerging trend in these studies seem to suggest that Islamic communities consumed predominately terrestrial resources outside of a few exceptions (Alexander et al., 2019). Conversely, Christian diets appeared to be highly variable depending on geographic location and emphasis on marine resources, with some such as Galicia exhibiting heavy reliance on marine resources (López-Costas and Müldner, 2019) where others such as the Portuguese site of Tomar seemed to rely on a mix of terrestrial and low-trophic fish (Curto et al., 2019). Toso et al. (2021) found a general lack of statistically significant sex differences for nearly all sites except for the high-status Muslim cemetery associated with the São Jorge castle in Lisbon (Toso et al., 2019). This complements other studies within Spain that similarly have found a lack of dietary differences via isotopes for both the general Muslim communities (Alexander et al., 2015; Salazar-García et al., 2016) and Christian laity (Lubritto et al., 2017; Jordana et al., 2019; MacKinnon et al., 2019). Toso et al. (2021) notably found evidence of marine consumption in both Islamic and Christian burials associated with urban Lisbon, and urge us to not only consider faith and cultural preferences, but acknowledge the importance of trade, mercantilism, and economics in facilitating access to various resources. A multi-isotopic investigation of diet and mobility in Évora at the time of the Christian conquests (twelfth to thirteenth century CE) is also worth considering (MacRoberts et al., 2020). Analyzing eight Christian burials in comparison with two Muslim burials, the authors found adult bone collagen (δ13Ccol) values consistent with mostly C3 inputs, while δ15N suggested high protein intake.

MacRoberts et al. (2024) present results from the first multi-isotopic analysis from human remains within the city of Santarém, with a focus on n = 45 Islamic burials from Avenida 5 de Outubro. Human collagen values were relatively homogenous with a δ13Ccol mean of −19.0‰ ± 0.5‰ (range:−19.9‰ to −17.0‰) and δ15N values averaging 10.4 ± 1.0‰ (range: 8.5‰ to 12.4‰). Bone apatite values were similarly homogenous, with a δ13Cap mean of −11.9‰ (range: −13.4‰ to −9.9‰). The authors also found no significant difference by sex, suggesting a relatively homogenous diet among males and females. Interestingly, the authors also found that those buried in a manner that ‘incorrectly' aligned with Mecca consumed higher quantities of C4 plants during childhood compared to those who were buried more in line (‘correctly') with Mecca. Finally, modeled values of collagen (δ13Ccol) strongly suggest C3 based protein inputs while apatite (δ13Cap) values suggest C3 dominance supplemented by C4 sources. Altogether, this exciting research has helped sketch some of the dimensions of Islamic diet within the city, so far suggesting a relatively homogenous dietary pattern among adults with an emphasis on C3 proteins.

The pilot stable isotope data presented here (Figures 7, 8; SI 11) are incredibly preliminary, but we report them here to supplement both our interpretation and burgeoning application of biogeochemical methods to archaeological contexts within medieval Portugal. Within the Islamic group, males (n = 7) had a δ15N 10.5 ± 0.3‰ whereas females (n = 5) had a δ15N 10.3 ± 0.6‰, suggesting virtually no sex differences in diet, though sample sizes are small. From a temporal perspective (Figures S1, S2), the subsample of Islamic individuals shows generally little variation in δ13C values. While earlier burials visually exhibit more δ13C variability (x = −18.9 ± 0.4‰) than later burials (x = −18.7 ± 0.3‰), the differences are less than 1‰ and barely above analytical error, so we caution against interpreting these as signaling any temporal change. In terms of δ15N values, most Islamic individuals fell between 10 to 11‰, though two early burials (Av5Out Ent. 956 and PVSP1 Ent. 1) exhibited lower δ15N values (9.4‰). It is curious to see the only Christian individual as a clear outlier (+2.1‰ from Islamic δ15N group mean, +1.8‰ from Islamic δ13C group mean). This may suggest that this individual consumed a higher trophic position diet consistent with marine resources or terrestrial meat coupled with C4 crops such as sorghum and millet (Ambrose, 1990), as discussed above in some other medieval Iberian Christian burials (Alexander et al., 2019; López-Costas and Müldner, 2019). Higher δ13C paired with δ15N values can correspond to consuming more marine sources, which typically have higher δ15N values than consuming terrestrial resources due to expanded trophic levels within marine food systems (Schoeninger and DeNiro, 1984). However, small sample size and lack of sufficient Christian burials severely limit our potential for interpretation and comparisons. Additionally, since these data were obtained through pilot radiocarbon dating, we additionally lack baseline faunal and floral data, further limiting interpretations. Future research is needed to characterize the baseline food web within the region, as well as elucidate whether this Christian individual is a true outlier, or possibly reflective of larger religious, socio-economic, and agronomic changes following the Christian conquests.

Differences in oral pathological lesions may be contextualized in relation to changing foodways and agricultural landscapes during the Portuguese middle ages. Uncorrected, crude caries frequencies suggest Islamic females had higher caries rates than their Christian female counterparts, but once corrected for antemortem tooth loss, Christian frequencies in caries rates were actually higher. In fact, Christian males exhibited a significantly higher frequency in caries compared to their Islamic male counterparts once corrected for antemortem tooth loss. These results suggest that correction factors continue to play an important role in elucidating caries frequencies in the past, especially in its relation to pulpal exposure, dental wear, and antemortem tooth loss. Additionally, these results may suggest that a reliance on heavy cereal diets in the later Christian middle ages could result in higher caries frequency compared to the dietary landscape during the Islamic period. However, dental wear was observed to be relatively minor in severity, with only ~20% of dental remains exhibiting severe wear (scores > 6), regardless of sex or funerary group. Most of the dental remains analyzed in this study exhibited moderate amounts of wear (Scores 3–4) such that a moderate-to-large area of dentine was exposed with enamel rims still complete. An analysis of dental wear from the Islamic necropolis of Al Fossar, Spain found males to exhibit more wear than their female counterparts (Gómez González, 2013, p. 138). Future studies conducting stable isotope analysis will aid immensely to better characterize the regional baseline, faunal variation, and human dietary patterns, especially among and between religious funerary groups. This study is therefore a preliminary analysis on possible diet and oral health within the city.

5.2 Reproductive ecology and fertility

Numerous bioarchaeological and clinical studies have observed significantly higher frequencies in antemortem tooth loss (al Shammery et al., 1998; Nelson et al., 1999; Cucina and Tiesler, 2003; López and Baelum, 2006; Oyamada et al., 2007; Meisel et al., 2008; Corraini et al., 2009; Shigli et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2010) and caries (Lukacs and Largaespada, 2006; Lukacs, 2008, 2017; Watson et al., 2010) in females compared to males, and interpreted such differences in light of reproductive ecology. In addition to potential sex and/or gendered differences in diet, increased caries and AMTL frequencies are interpreted as a product of age- and fertility-related alterations in hormones (e.g., estrogen and progesterone) which have cascading effects on salivary quality and quantity (Steinberg, 2000; Laine, 2002; Burakoff, 2003; Silk et al., 2008). Clinically, saliva has been shown to be a crucial inhibitor to cariogenesis through its role as a lubricant, as a pH buffer, and in remineralizing enamel (Dowd, 1999; Lenander-Lumikari and Loimaranta, 2000; Amerongen and Veerman, 2002; Vitorino et al., 2006; de Almeida et al., 2008). Increased estrogen levels, especially during pregnancy, appear to result in decreased salivary flow and quantity, which can lead to changes in the overall oral microbiome and subsequent dental pathological lesions such as tooth loss, cariogenesis, and plaque buildup (Kolenbrander and Palmer, 2004; Marsh, 2004; Arantes et al., 2009; Fields et al., 2009). However, in bioarchaeological studies, salivary factors are difficult to control for given the inability to reconstruct saliometric and saliochemical profiles, though some studies have considered such factors in light of dental remains (Lukacs and Largaespada, 2006; Lukacs, 2017; Trombley et al., 2019).

While numerous sources have analyzed medieval fertility, biology, and motherhood in the Islamic Middle East (Kueny, 2013; Verskin, 2020), unfortunately, there is a general lack of ethnohistorical sources relating to specific birthing and reproduction within central Portugal during the medieval period. Paleodemographic assessments and fertility estimates, such as D30+/D5+ ratios (Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994, p. 534) can aid in contextualizing patterning in dental pathological lesions (Klaus and Tam, 2010; Trombley et al., 2019). This ratio examines the number of individuals over 30 years of age (D30+) compared to the number of individuals over 5 years of age (D5+), as the ratio is negatively associated with birth rate. Unfortunately, D30+/D5+ require a preservation of sub-adults to more accurately reflect fertility estimates. Both Largo Cândido dos Reis and Avenida 5 de Outubro contained few sub-adults at the site, either as a result of excavation/intervention areas, preservation, recovery techniques, deliberate burial of sub-adults in a separate location from adults, or a confluence of all of these factors (Matias, 2008a; Petersen, 2013). As a result, D30+/D5+ could not be calculated with accuracy. Consequently, our interpretation of dental pathological lesions in light of reproductive demands are preliminary. Our results suggest a general elevation of dental pathological lesions frequencies in Islamic females compared to Islamic males, with Islamic females exhibiting higher frequencies of AMTL, both corrected and uncorrected caries, and calculus compared to their male counterparts. Conversely, no such sex differences were observed in Christians. When females were compared by funerary group, Islamic females showed a higher crude frequency of caries compared to Christian females, but the difference was not significant when corrected for antemortem tooth loss. Notably, there was no significant difference in older (50+ years) Islamic females compared to Christian females for AMTL, caries (both corrected and uncorrected), nor calculus. However, older Christian females did exhibit significantly higher rates of periodontal disease compared to their Islamic female counterparts (Table 3). Given that Islamic females exhibited higher frequencies of dental pathological lesions compared to Islamic males, but not Christian females, it follows that Islamic and Christian females exhibited similar levels of reproductive demands, and that sex differences were likely more a product of dietary and/or hygienic differences within funerary groups rather than reproductive ones, though future research is needed to clarify this further.

5.3 Sex, gender, and religious attitudes toward oral hygiene

Here, we seek to consider how gendered and religious conceptions on oral cleanliness may explain some of the variation observed in dental pathological lesions. Interpreting textual and oral evidence directly in light of bioarchaeological remains is often tenuous and challenging (Perry, 2007), and oral hygienic regimens in particular prove difficult to document in bioarchaeological samples. However, contextualized analysis of dental tissues in light of ethnohistorical accounts and sources can provide unique and textured insights into oral hygiene and lesion patterning (Hosek et al., 2020). For example, in their examination of the Late Classic period (600–800 CE) Maya site of Piedras Negras. Schnell and Scherer (2021) help reframe how isolated teeth, although frequently understudied due to their decontextualized nature, can provide insights on therapeutic tooth extractions. They did this by comparing loose teeth with an adjacent mortuary sample whose teeth were still in occlusion. They hypothesized that loose teeth could be interpreted as extracted if they showed (1) different patterning compared to those of the adjacent mortuary population, since posterior dentition would have more likely been extracted, (2) increased prevalence of pathology compared to the mortuary sample, since those teeth would be more likely targets for therapeutic extraction, and (3) decreased dental wear compared to the mortuary sample, since they would have been in the mouth for fewer years. They found that tooth types did indeed vary between the loose teeth and mortuary sample, with loose teeth being over-represented in terms of posterior dentition (77%) compared to the mortuary sample (62.5%). The loose teeth sample also exhibited higher prevalence of carious lesions (59%) compared to the mortuary sample (17.2%). Finally, dental wear was less severe in the loose teeth than the mortuary sample, but the difference was not significant. Altogether, these results supported their hypotheses that many of these teeth were in fact the result of extractions. This was bolstered by the fact that many of loose teeth (77%) showed incidence of traumatic fractures, likely resulting from extraction and not ante- or post-mortem trauma given their location patterning around the CEJ, which would have been a prime target for grasping the tooth close to the gumline. Ultimately, Schnell and Scherer (2021) make a convincing case for interpreting loose teeth systematically in terms of dentistry, and for expanding Maya dentistry beyond just cosmetics to also include palliative care (Cucina and Tiesler, 2011). Subsequent research (Watson et al., 2023) incorporated microbotanical analyses and residue analyses of teeth from Piedras Negras alongside geospatial data on the proximity of monumental sweatbaths to situate oral healthcare in terms of the Mayan marketplace. By synthesizing ethnohistorical and paleoethnobotanical analyses with osteological analyses of dental remains and architecture, Watson et al. (2023) effectively trace how healthcare can be both in the oral cavity and on the landscape.

We follow this approach to discuss how oral hygiene and care may have affected the dental pathological lesions observed in this study. We begin by examining some of the broader Islamic conceptions surrounding oral hygiene, and in turn examine conceptions and prescriptions within later medieval Christendom. Throughout much of the medieval Islamic world, the teachings of the Holy Prophets of Islam appear to have institutionalized oral hygiene as a practice of piety in ḥadīth. Occasionally referenced is the brushing of the teeth and mouth with siwāk (or miswāk)—a toothbrush, preferentially made from the bark, branches, and roots of the arāk tree, a variety of Salvadora persica:

“If I did not feel that it would be difficult upon my Ummah [believers, people], I would have commanded them to perform miswāk with every Wudu [ablution]”1

“Make it a habit to perform miswāk, as it is a means of cleansing the mouth and a means of attaining the pleasure of Allah”2

“When any one of you stand at night to offer Salah, you should clean your teeth with a miswāk because when you recite the Quran, an angel places his mouth on yours and anything coming out of your mouth enters the mouth of that angel”3