Abstract

Objectives:

The COVID-19 is a global health issue with widespread impact around the world, and many countries initiated lockdowns as part of their preventive measures. We aim to quantify the duration of delay in discharge to community from Community Hospitals, as well as quantify adverse patient outcomes post discharge pre and during lockdown period.

Design and methods:

We conducted a before-after study comparing the length of stay in Community Hospitals, unscheduled readmissions or Emergency Department attendance, patients' quality of life using EQ5D-5l, number and severity of falls, in patients admitted and discharged before and during lockdown period.

Results:

The average length of stay in the lockdown group (27.77 days) were significantly longer than that of the pre-lockdown group (23.76 days), p = 0.003. There were similar proportions of patients with self-reported falls post discharge between both groups. Patients in the pre-lockdown group had slightly better EQ-5D-5l Index score at 0.55, compared to the lockdown study group at 0.49. Half of the patients in both groups were referred to Community Care Services on discharge.

Conclusion:

Our study would help in developing a future systematic preparedness guideline and contingency plans in times of disease outbreak and other similar public health emergencies.

Introduction

The novel Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (1), and has become a global health issue with widespread impact on countries around the world. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a pandemic due to its alarming rates of spread and severity (2). As of August 2022, there have been 587 million confirmed cases, and 6.4 million deaths reported globally (3). Many countries around the world initiated lockdowns as part of their preventive measures, with the aim to curb the spread of the virus by limiting people's movement.

Intermediate and long-term care (ILTC) services include a range of healthcare services outside of acute hospitals, typically required for patients who need further care after acute hospitalizations (4). They consist of home-based (such as home medical/nursing/palliative care and Meals-On-Wheels), centre-based (such as day care, day hospice), and residential services [such as community hospitals (CHs), nursing homes]. CHs in Singapore are intermediate care facilities, vital to the continuum of health services that are incorporated into the healthcare landscape to bridge acute and primary care. Similar to CHs in the United Kingdom (5), they are pivotal in delivering both health and social care to optimize patients' activities of daily living in preparation for community re-integration or long-term care stay (6). On discharge from CH, should transfer to or follow-up with long term care facilities such as nursing homes, senior care services and day rehabilitation centers be warranted, the CH team would apply via the Agency for Integrated Care portal after getting patients' and family agreement.

A search on the current literature reveals extensive research into the pathology, diagnosis, prevention and management of COVID-19 (7–9). We also found studies delving into the impact of COVID-19 on various at-risk groups of patients who were not infected with the virus, such as patients with dementia (10, 11), cancer (12), and eating disorders (13, 14). However, there was scant research investigating how lockdown measures have impacted discharge planning and continuity of integrated care for patients after being discharged from intermediate care facilities such as CHs during the lockdown period.

In an effort to help fill this gap, our study aims to (i) quantify the difference in duration of stay at the CHs between the pre-lockdown and the lockdown periods, as well as (ii) quantify the difference in adverse patient outcomes after discharge to community from CHs between the pre-lockdown and during lockdown periods.

Materials and methods

Design

This was a before-after study approved by the Institutional Review Board, and is part of a larger mixed-methods study (15).

Setting and participants

CHs in Singapore provide rehabilitation care and post-acute care to patients recovering after an acute illness. Participants were recruited from two large CHs with a total of 848 beds, which are part of a Regional Health System in Singapore serving more than 50% of the country's population with its network of acute hospitals, national specialty centres, CHs and polyclinics. Typical patients in a CH would be deconditioned after a major illness, such as stroke, hip fracture, Parkinson's disease, heart failure, to name a few.

Despite efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 through aggressive contact tracing, strict isolation methods and vigorous testing in Singapore, there was an increasing trend of community transmission with outbreaks in foreign worker dormitories (16). This led to the Singapore government to impose an elevated set of safe-distancing measures in the form of a country-wide lock down, termed “Circuit Breaker” in early April 2020 (17).

As part of the lockdown, services deemed to be “non-essential” were scaled down or halted. Residential and home-based community care services such as nursing homes, psychiatric rehabilitation homes, inpatient or home palliative care continued to function, while home personal care services were scaled down (18). Senior care centers, day rehabilitation centers, medical escort services and day hospices were closed temporarily (18). Public and private acute hospitals, CHs, polyclinics were deemed to be essential and remained open, though with tightened visitation policies (19). For example, nearly all visitors were prohibited to hospitals except in special circumstances such as for dangerously ill patients. The discharge process would understandably be delayed in view of disruption of training for caregivers and changes in therapy sessions.

We examined patients aged 21 years old (minimum age for patients to be admitted to CHs) and above who were admitted and then discharged in sub-acute and rehabilitation wards in the two CHs between 7 April 2020 to 31 July 2020 (study group during lockdown), a period during which Singapore was under lockdown measures. The outcome measures from this group of patients were compared with those admitted and then discharged from 1 Nov 2019 to 29 Feb 2020 (pre-lockdown period).

Data collection

Baseline demographic characteristics during recruitment including age, gender, marital status, ethnic group etc were collected, as well as Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) Score, Admission Diagnosis Related Group (DRG), length of hospital stay (LOS) and details of referral to Community Care Services (CCS) through medical records review.

Follow-up data were obtained via phone calls at 3 timepoints (30 days, 90 days, 180 days post discharge) for lockdown group patients and at least 1 timepoint (90 days and if possible, 180 days post discharge) for the pre-lockdown group. Patients who were discharged to long-term care facilities such as nursing homes, had hearing difficulties or faced language barriers when communicating with our study team members were excluded from this study. Due to the time-sensitive nature of this study and time required for the research grant and ethics approval, data collection of self-reported outcomes at 30 days was not possible for some of the lockdown group participants. However, key outcome measures such as length of stay, Emergency Department (ED) attendance or unscheduled readmissions within 180 days of discharge were extracted via electronic health records.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was LOS (days) in the respective CHs. Secondary outcome measures were 180 days unscheduled readmissions or ED visits to an acute hospital, number and severity of falls (using the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators® developed by the American Nurses Association (ANA-NDNQI) for fall related injuries categories (20)) at the most distal of the 3 timepoints post discharge available, and patient's quality of life [using EQ-5D-5l (21)] at 180 days post discharge.

EQ-5D-5l consist of 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression), each with 5 levels (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems), which can be converted to an Index score that reflects one's health status and quality of life. A higher index score corresponds to a better quality of life and better health. EQ-5D-5l VAS is a 0—100 scale where patients are asked to indicate their overall health on the day of questionnaire completion, with 100 as the best possible health imaginable (22). Incorporating both EQ-5D-5l Index score and VAS as outcomes measures in our study gives a more holistic picture of participants' quality of health.

We defined unscheduled readmissions or ED visits as any admissions or visits due to an unforeseen or non-elective cause, within 180 days of discharge from index community hospital admission.

Data analysis

Categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages, while continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations. To assess the association of group status (pre-lockdown vs. lockdown) with categorical and continuous variables, bivariate analyses were performed by using the Chi-square test and two-sample t-test respectively. Linear regression models were performed to assess the association between group status and length of stay in days. A simple linear regression model with only group status was first considered and provided an unadjusted analysis. Subsequently, a multiple linear regression model was considered that also included significant variables in the bivariate analyses such as gender and CCI as predictors to provide an adjusted analysis. The analyses were conducted using R software, Version 4.1.3, with p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Participants

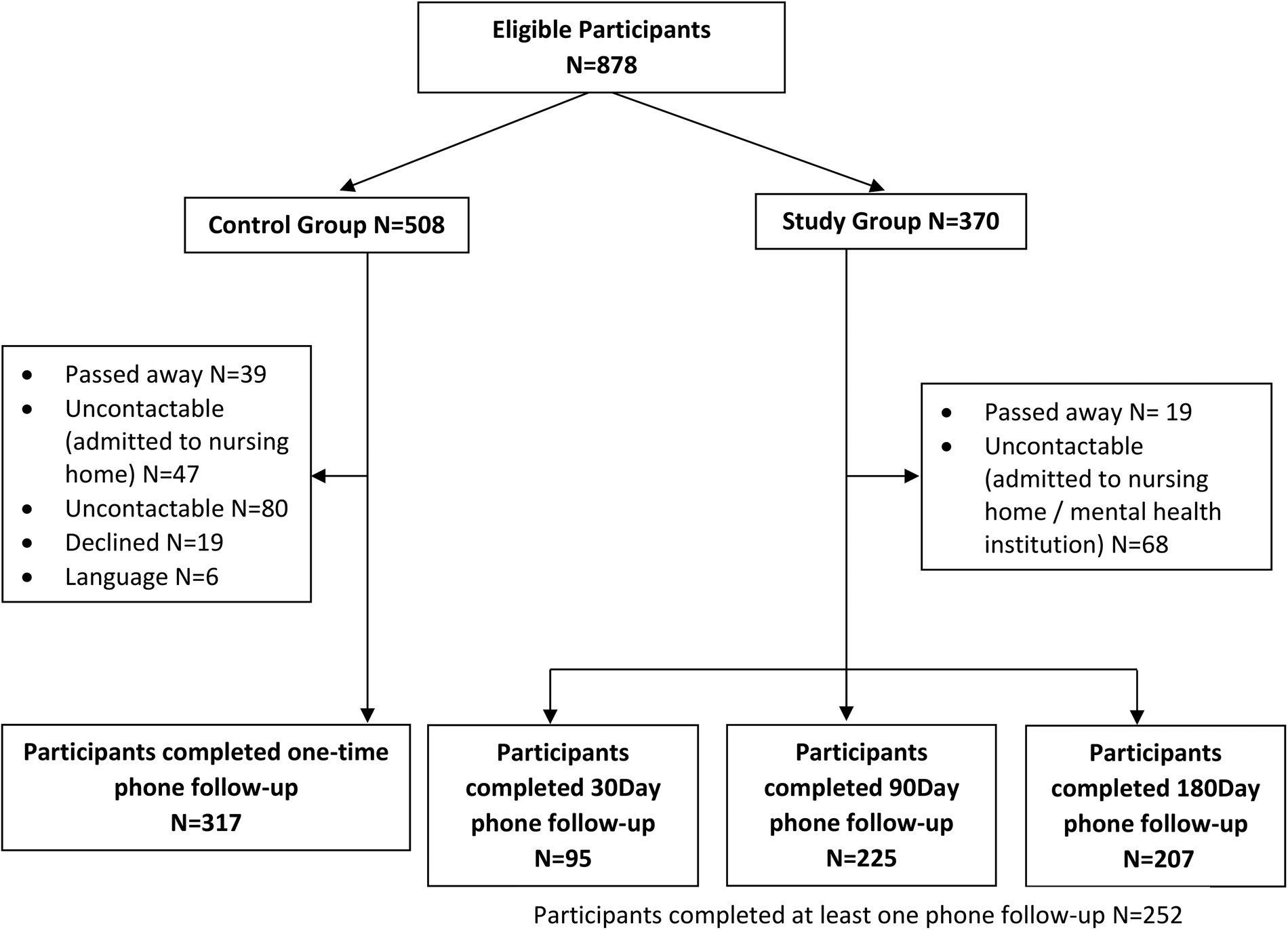

A total of 878 patients fulfilling criteria were admitted and discharged during the study period, with 508 from the pre-lockdown group and 370 from the lockdown group (Figure 1). Amongst these, 191 patients (37.6%) from the pre-lockdown group and 77 patients (20.8%) from the lockdown group were lost to follow-up for patient-reported outcomes at all three time points due to reasons such as being uncontactable, declined follow-up phone calls, language barriers or death. Overall, 317 patients from the pre-lockdown group completed one-time phone follow-up. In the lockdown group, 95 patients completed 30 days phone follow-up, 225 patients completed 90 days phone follow-up, and 207 patients completed 180 days phone follow-up.

Figure 1

Participant flowchart.

The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. There were more female patients in both groups, at 312 (61.4%) for the pre-lockdown group, and 198 (53.5%) for the lockdown group. The mean age of both groups was the same at 75 years old. It is notable that patients in the lockdown group had a statistically significant higher CCI Score (p < 0.001). We have also included the common comorbidities seen among patients in the pre-lockdown and lockdown group in Table 2.

Table 1

| Patient characteristics n = 878 | Control n = 508 | Study n = 370 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 196 (38.6) | 172 (46.5) | .01909 |

| Female | 312 (61.4) | 198 (53.5) | |

| Age group, n (%) | |||

| 65 and above | 417 (82.1) | 305 (82.4) | .8947 |

| Below 65 | 91 (17.9) | 65 (17.6) | |

| Age in years, mean (SDa) | 75.14 (11.18) | 75.14 (12.33) | .9997 |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | |||

| Chinese | 433 (85.2) | 305 (82.4) | .2625 |

| Non-Chinese | 75 (14.8) | 65 (17.6) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 85 (5.7) | 68 (18.4) | .2343 |

| Married | 141 (27.8) | 84 (22.7) | |

| Unknown | 282 (55.5) | 218 (58.9) | |

| LOSb in days, mean (SD) | 23.76 (16.09) | 27.77 (17.73) | 0.003 (Adjusted) |

| CCIc score, mean (SD) | 4.95 (2.64) | 6.06 (2.82) | <.001 |

| No. of unscheduled readmissions/ED visits (180 day), mean (SD) | 1.54 (0.89) | 1.55 (1.05) | .925 |

Patient characteristics.

SD, Standard deviation.

LOS, Length of hospital stay.

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Table 2

| Common comorbidities among patients, n (%) | Control n = 317 | Study n = 252 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction | 40 (12.62) | 39 (15.48) | 0.3913 |

| Congestive heart failure | 27 (8.52) | 20 (7.94) | 0.923 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 57 (17.98) | 78 (30.95) | 0.0004 |

| Dementia | 31 (9.78) | 39 (15.48) | 0.054 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 99 (31.23) | 98 (38.89) | 0.069 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 45 (14.2) | 50 (19.84) | 0.0929 |

Common comorbidities among patients in control and study group.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The average LOS in the lockdown study group (27.77 ± 17.73 days) were significantly longer than that of the pre-lockdown group (23.76 ± 16.09 days), at p = 0.003 (Table 1). The linear regression model was adjusted for gender and CCI Score as shown in Table 3. Patients admitted during COVID-19 were more likely to stay 3.5 more days than patients who were admitted during pre-COVID-19 period.

Table 3

| Coefficient | 95% Confidence interval | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19a | 3.4873 | 1.154–5.820 | 0.003 |

Association between COVID-19 study group status and length of stay.

The linear regression model was adjusted for gender and CCI score due to the statistical significance at baseline between COVID-19 study group and control group.

There was a similar proportion of patients with self-reported falls post discharge at 180 days between both groups at around 18%, with an average of 0.3 falls per participant (Table 4). In terms of quality of life, patients in the pre-lockdown group had slightly better EQ-5D-5l Index score at 0.55 ± 0.44, compared to the lockdown study group at 0.49 ± 0.49 (Table 4), although there is no statistical significance. In addition, pre-lockdown group patients had significantly better EQ-5D-5l VAS score (68.03 ± 18.79) than lockdown study group patients (57.17 ± 30.20), p < 0.01.

Table 4

| Control n = 317 | Study n = 252 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported falls | |||

| No. of self-reported falls post-discharge, n (%) | 59 (18.61) | 46 (18.25) | 0.9129 |

| No. of falls per participant, mean (SDa) | 0.33 (0.78) | 0.3 (0.95) | 0.657 |

| Quality of life based | |||

| EQ-5D-5l index score, mean (SDa) | 0.55 (0.44) (2 with no values) |

0.49 (0.49) (48 with no values) |

0.1289 |

| EQ-5D-5l VAS score, mean (SDa) | 68.03 (18.79) (33 with no values) |

57.17 (30.20) (36 with no values) |

<0.001 |

Self-reported falls and quality of life based on 569 patients surveyed in this study.

SD, standard deviation.

As can be seen from Table 5, approximately half of the patients in both the pre-lockdown and lockdown group were referred to Community Care Services on discharge, with the majority being centre-based care such as day care or day rehabilitation. Nearly two-thirds of patients from both groups require caregivers, of which half were foreign domestic workers.

Table 5

| Control n = 317 | Study n = 252 | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients discharged home with no community care services, n (%) | 153 (48.26) | 130 (51.59) |

| Patients referred to community care services, n (%) | 164 (51.74) | 122 (48.41) |

| Community care services referred per person, mean (SDa) | 0.55 (0.57) | 0.55 (0.62) |

| Type of community care services referral | (175) | (149) |

| Centre based care (includes day care and day rehabilitation) | 134 | 87 |

| Home based care (includes home medical, home nursing, home palliative care, home personal care, home therapy) | 17 | 38 |

| IHDCb, ICSc | 14 | 12 |

| Meals on wheels and medical escort | 9 | 10 |

| Residential care (short stay unit) | 1 | 2 |

| Community care services rendered post-discharge, n (%) | 104 (63.41) | 85 (69.67) |

| Require caregiver, n (%) | 195 (61.51) | 162 (64.29) |

| Require new caregiver post-discharge, n (%) | 78 (24.61) | 38 (15.08) |

| Caregiver relationship | ||

| Spouse | 37 (18.97) | 27 (16.67) |

| Child/child-in-law | 28 (14.36) | 39 (24.07) |

| Parent/grandchildren | 0 | 3 (1.85) |

| Foreign domestic worker | 102 (52.31) | 75 (46.30) |

| Others (siblings, relatives, friends etc.) | 28 (14.36) | 17 (10.49) |

Discharge destination, community care services and caregiver needs.

SD, Standard deviation.

IHDC, Integrated Home and day care.

ICS, Interim care services.

Discussion

In our study, we found that patients staying in CHs during the lockdown period had statistically significantly longer LOS in the CHs than those during the pre-lockdown period. Limitations to access in follow-up care like day rehabilitation centres and medical escort services during lockdown may likely have prolonged the discharge process and impacted on continuity of integrated care. Other postulations to explain the longer LOS observed include delay due to lockdown restrictions such as new foreign domestic workers not being able to enter the country. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic measures and the subsequent disruption of community care services on discharge planning and continuity of integrated care on various stakeholders such healthcare workers, community partners and patients' caregivers, was explored in the qualitative component of our study through semi-structured interviews (15). Various studies have shown that higher CCI have been associated with a longer length of stay (23–25), and our linear regression model was adjusted for CCI due to statistical significance at baseline between pre-lockdown group and lockdown group.

Additionally, our study revealed that the patients staying in CHs during the lockdown period had a higher CCI Scores than those staying there during the pre-lockdown period. This suggests that more medically complex patients were admitted and discharged to CHs during the lockdown period. One possible explanation for this would be that acute hospital physicians tried to discharge patients back home as far as possible to reduce the risk of transmission in a facility. Hence, patients who were admitted to the CHs were more medically complex and also unable to be discharged directly to home from acute care. It is also possible that patients with mild illnesses avoided admission to CH for fear of COVID-19 transmission. This is alluded to in an Italy study whereby authors found a dramatic decrease in emergency department access during COVID-19 period, especially after lockdown, with the reduction mostly from patients who decided to seek emergency department care directly (26). This was attributed at least partly to fear of being infected with COVID-19. Other studies have also showed similar findings (27, 28).

In an effort to circumvent the safe distancing measures and to facilitate communication for better continuity of care, telemedicine had gained popularity due to the reduction in risk of COVID-19 transmission and the Singapore government's Smart Nation initiative (29). At MyDoc, a telemedicine platform headquartered in Singapore, the number of daily active users rose 60% in February and more than doubled again in March 2020 (30). However, its uptake was found to be limited by a number of factors, including patient-related barriers such as limited digital literacy among older adults, hearing impairments and inability to adequately describe care needs and symptoms (15, 31). Measures to educate the less tech-savvy population as well as to promote access to such telemedicine services could help improve utilisation of telemedicine, which have been demonstrated in studies to help promote disease management and self-care in older patients (32, 33). This would be exceptionally useful in the face of the various safe distancing measures (34).

Furthermore, our study found lower EQ-5D-5l Index score and EQ-5D-5l VAS score for patients in the lockdown group, suggesting a lower quality of life in this group of patients. The effect of the pandemic on quality of life was further explored in several studies (35–37), and reported the far-reaching effects of COVID-19 beyond just healthcare-related outcomes.

As part of the efforts to improve its pandemic preparedness against future infectious disease outbreaks, the Singapore Ministry of Health established PREPARE, or the Programme for Research in Epidemic Preparedness and Response (38). This workgroup is tasked with developing a national epidemic Research and Development plan that helps generate methods and tools to respond to future infectious disease outbreaks. Our study has shown a possible association of longer length of stay in CH and worse quality of life among patients in the lockdown group while they were under COVID-19 restrictions. This could spur on efforts by the PREPARE workgroup to design measures that identify and help mitigate such effects.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies that attempts to quantify the duration of delay in discharge as well as adverse discharge outcomes of patients from CHs before and after COVID-19 lockdown period. However, the results of our study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. In view of the retrospective nature of the study, it is susceptible to recall bias among the pre-lockdown group participants and their caregivers due to time lag between study and patients’ discharge date. We attempted to minimize this by using objective measures such as LOS and 180 days unscheduled readmissions or ED attendance back to an acute hospital. These were obtained via electronic health records and hence were not subjected to recall bias.

Additionally, despite the best of our efforts, we noted a significant proportion of patients lost to follow up (37.5% in the pre-lockdown group and in the 23.5% lockdown group). This could possibly influence the findings. Future studies are needed to further assess the long-term impact of lockdown measures.

Conclusion

Pandemics such as COVID-19 had posed challenges to governments and its healthcare systems around the world. Our study findings quantified the impact of COVID-19 and safe distancing measures had on discharge planning in CHs and patient outcomes. The importance of continuity of integrated care services for patients cannot be overly emphasized, and we believe findings from our study would inform the future development of systematic emergency preparedness guidelines and contingency plans in times of disease outbreak and other similar public health emergencies. This would help to minimize disruption of integrated care throughout the different levels and sites of care within the health system. Exploring the feasibility and barriers to adopting innovative models of care for different patient segments will also help to build a more inclusive society.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: LL, YK, CT, and SY. Acquisition of data: LL, SL, YL, BX, CK, KL, ZL, RT, and SL. Analysis and interpretation of data: JX, SC, YK, LL, and CT. Drafting of the manuscript: SC. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: SC, JX, YK, ZL, CT, SL, BX, YL, LK, CK, RT, SL, SY, SS, and LL. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Petrosillo N Viceconte G Ergonul O Ippolito G Petersen E . COVID-19, SARS and MERS: are they closely related?Clin Microbiol Infect. (2020) 26(6):729–34. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.026

2.

Cucinotta D Vanelli M . WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. (2020) 91(1):157–60. 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

3.

Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19–17 August 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—17-august-2022 (Accessed August 22, 2022).

4.

MOH | Intermediate And Long-Term Care (ILTC) Services. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/home/our-healthcare-system/healthcare-services-and-facilities/intermediate-and-long-term-care-(iltc)-services (Accessed August 22, 2022).

5.

Heaney D Black C O'donnell CA Stark C van Teijlingen E . Community hospitals—the place of local service provision in a modernising NHS: an integrative thematic literature review. BMC Public Health. (2006) 6:309. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-309.

6.

Ministry of Health Singapore. Community Hospital Care. Handbook for Patients. (2017). Available at:moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/default-document-library/handbook-on-ch-care-for-healthcare-professionals-2nd-edition-200918-for.pdf

7.

Dhama K Khan S Tiwari R Sircar S Bhat S Malik YS et al Coronavirus disease 2019–COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2020) 33(4):e00028–20. 10.1128/CMR.00028-20

8.

Dinnes J Deeks JJ Berhane S Taylor M Adriano A Davenport C et al Rapid, point-of-care antigen tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2021) 2021(3):CD013705. 10.1002/14651858.CD013705.pub2

9.

Sharma A Ahmad Farouk I Lal SK . COVID-19: a review on the novel coronavirus disease evolution, transmission, detection, control and prevention. Viruses. (2021) 13(2):202. 10.3390/v13020202

10.

Soysal P Smith L Trott M Alexopoulos P Barbagallo M Tan SG et al The effects of COVID-19 lockdown on neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychogeriatrics. (2022) 22(3):402–12. 10.1111/psyg.12810

11.

Rajagopalan J Arshad F Hoskeri RM Nair VS Hurzuk S Annam H et al Experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic in India: a mixed-methods study. Dement Lond Engl. (2022) 21(1):214–35. 10.1177/14713012211035371

12.

Pareek A Patel AA Harshavardhan A Kuttikat PG Pendse S Dhyani A et al Impact of nationwide lockdown on cancer care during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective analysis from Western India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. (2021) 15(4):102131. 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.05.004

13.

Baenas I Etxandi M Munguía L Granero R Mestre-Bach G Sánchez I et al Impact of COVID-19 lockdown in eating disorders: a multicentre collaborative international study. Nutrients. (2021) 14(1):100. 10.3390/nu14010100

14.

Schneider J Pegram G Gibson B Talamonti D Tinoco A Craddock N et al A mixed-studies systematic review of the experiences of body image, disordered eating, and eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Eat Disord. (2022) 56(1):26–67. 10.1002/eat.23706

15.

Yoon S Mo J Lim ZY Lu SY Low SG Xu B et al Impact of COVID-19 measures on discharge planning and continuity of integrated care in the community for older patients in Singapore. Int J Integr Care. (2022) 22(2):13. 10.5334/ijic.6416

16.

MOH. COVID-19 Statistics. Available at:https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/statistics

17.

MOH. Circuit Breaker to Minimise Further Spread of COVID-19 (2020). Available at:https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/circuit-breaker-to-minimise-further-spread-of-covid-19

18.

MOH. Continuation of Essential Healthcare Services During Period of Heightened Safe Distancing Measures (2020). Available at:https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/continuation-of-essential-healthcare-services-during-period-of-heightened-safe-distancing-measures

19.

Channel News Asia. No visitors for patients in hospitals except in certain cases, MOH says (2020). Available at:https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/covid-19-visitors-not-allowed-patients-hospitals-moh-763181

20.

Garrard L Boyle DK Simon M Dunton N Gajewski B . Reliability and validity of the NDNQI® injury falls measure. West J Nurs Res. (2016) 38(1):111–28. 10.1177/0193945914542851

21.

Herdman M Gudex C Lloyd A Janssen MF Kind P Parkin D et al Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5l). Qual Life Res. (2011) 20(10):1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

22.

Brooks R . Euroqol: the current state of play. Health Policy Amst Neth. (1996) 37(1):53–72. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6

23.

Lakomkin N Kothari P Dodd AC VanHouten JP Yarlagadda M Collinge CA et al Higher charlson comorbidity Index scores are associated with increased hospital length of stay after lower extremity orthopaedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. (2017) 31(1):21–6. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000701

24.

Ofori-Asenso R Zomer E Chin KL Si S Markey P Tacey M et al Effect of comorbidity assessed by the charlson comorbidity index on the length of stay, costs and mortality among older adults hospitalised for acute stroke. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15(11):2532. 10.3390/ijerph15112532

25.

Yang Y. Ong BC . The effect of comorbidity and age on hospital mortality and length of stay in patients with sepsis. J Crit Care. (2010) 25(3):398–405. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.09.001

26.

Garrafa E Levaggi R Miniaci R Paolillo C . When fear backfires: emergency department accesses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy Amst Neth. (2020) 124(12):1333–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.10.006

27.

Ojetti V Covino M Brigida M Petruzziello C Saviano A Migneco A et al Non-COVID diseases during the pandemic: where have all other emergencies gone? Medicina (Kaunas). (2020) 56(10):512. 10.3390/medicina56100512

28.

Bellan M Gavelli F Hayden E Patrucco F Soddu D Pedrinelli AR et al Pattern of emergency department referral during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Panminerva Med. (2021) 63(4):478–81. 10.23736/S0031-0808.20.04000-8

29.

Smart Nation Singapore — Responding to COVID 19 with Tech. Available at: https://www.smartnation.gov.sg/covid-19/covid-19-tech

30.

Covid-19 Accelerates the Adoption of Telemedicine in Asia-Pacific Countries. Bain. (2020) Available at: https://www.bain.com/insights/covid-19-accelerates-the-adoption-of-telemedicine-in-asia-pacific-countries/ (Accessed September 25, 2022).

31.

Scott Kruse C Karem P Shifflett K Vegi L Ravi K Brooks M . Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. (2018) 24(1):4–12. 10.1177/1357633X16674087

32.

Hwang NK Park JS Chang MY . Telehealth interventions to support self-management in stroke survivors: a systematic review. Healthcare. (2021) 9(4):472. 10.3390/healthcare9040472

33.

Wang QQ Zhao J Huo XR Wu L Yang LF Li JY et al Effects of a home care mobile app on the outcomes of discharged patients with a stoma: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. (2018) 27(19–20):3592–602. 10.1111/jocn.14515

34.

Lai FHY Yan EWH Yu KKY Tsui WS Chan DTH Yee BK . The protective impact of telemedicine on persons with dementia and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28(11):1175–84. 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.07.019

35.

Mouratidis K . How COVID-19 reshaped quality of life in cities: a synthesis and implications for urban planning. Land Use Policy. (2021) 111:105772. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105772

36.

Tessitore E Mach F . Impact of COVID-19 on quality of life. e-Journal of Cardiology Practice. (2021) 21(3). https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-21/impact-of-covid-19-on-quality-of-life(Accessed August 12, 2022).

37.

Lehmann J Holzner B Giesinger JM Bottomley A Ansari S von Butler L et al Functional health and symptoms in Spain before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:837. 10.1186/s12889-021-10899-2

38.

MOH | News Highlights. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/speech-by-mr-ong-ye-kung-minister-for-health-at-the-launch-event-for-the-programme-for-research-in-epidemic-preparedness-and-response-(prepare)-3-november-2022-at-the-ministry-of-health (Accessed June 22, 2023).

Summary

Keywords

COVID-19, discharge planning, public health, care continuity, lockdown

Citation

Chia S, Xia J, Kwan YH, Lim ZY, Tan CS, Low SG, Xu B, Loo YX, Kong LY, Koh CW, Towle RM, Lim SF, Yoon S, Seah SSY and Low LL (2023) Evaluating the association of COVID-19 restrictions on discharge planning and post-discharge outcomes in the community hospital and Singapore regional health system. Front. Health Serv. 3:1147698. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2023.1147698

Received

31 January 2023

Accepted

24 August 2023

Published

05 September 2023

Volume

3 - 2023

Edited by

Joris Van De Klundert, Adolfo Ibáñez University, Chile

Reviewed by

Hujie Wang, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands Shasha Yuan, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Chia, Xia, Kwan, Lim, Tan, Low, Xu, Loo, Kong, Koh, Towle, Lim, Yoon, Seah and Low.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Lian Leng Low low.lian.leng@singhealth.com.sg

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.