- 1Centre for Healthcare Innovation Research (CHIR), City St George's, University of London, London, United Kingdom

- 2Faculty of Management, Bayes Business School, City St George's, University of London, London, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Health Services Research and Management, School of Health and Psychological Sciences, City St George's, University of London, London, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Social and Policy Sciences, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom

The implementation of innovations in practice is challenging and often produces disappointing outcomes. Although the reasons for this are multifaceted, part of the challenge derives from the lack of consensus on how such implementation outcomes should be conceptualized and measured. In this review, we used a meta-ethnographic approach to enhance our theoretical conceptualization of implementation outcomes. By situating such outcomes within the overall process of implementation, we were able to unpack them analytically as the product of two major components, which we term “modes” and “attributes,” respectively. Modes comprise engagement, active implementation, and integration to foreground focal implementation outcomes. The attributes associated with the modes comprise implementation depth, implementation breadth, implementation pace, implementation adaptation, and de-implementation to indicate the features of the modes of implementation outcomes. Taken together, our analysis based on modes and attributes provides an integrated framework of implementation outcomes. The proposed framework enhances our understanding of the way in which implementation outcomes have been conceptualized in previous literature, enabling us to clarify the relations and distinctions between them in terms of translatability and complementarity. The proposed framework thus extends the conceptualization of implementation outcomes to better align with the complex reality of implementation practice, offering useful insights to researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

1 Introduction

It has been argued that in healthcare, “without good implementation, innovation amounts to very little” (1). Yet, several healthcare innovations often fail to realize their potential because they are not implemented effectively or sustainably over time. This challenge has been observed in health systems globally (2–4), leading to significant waste of resources and energies.

Part of the explanation of why innovations fail to be implemented in practice is the lack of consensus on how individual implementation outcomes are conceptualized and measured (5, 6), making it challenging to learn about the reasons for both implementation successes and failures. Collectively, implementation outcomes have been defined, for example, as “success or failure of implementation” (7), “implementation effectiveness” (8), “impact of the implementation strategy” (9), or “effects of deliberate and purposive actions to implement new interventions” (10). In this review, we broadly refer to implementation outcomes as the consequences or effects of implementation efforts for innovations. Implementation outcomes (the focus of our review) are distinguished from other possible outcomes that result from implementing a given innovation, commonly referred to as service outcomes and client/clinical outcomes (10).

Over the last two decades, significant efforts have been made to develop and conceptualize frameworks that provide structure for evaluating implementation (11). Two seminal works that have become gold standards for assessing implementation effectiveness—the Implementation Outcomes Framework (IOF) (10) and Reach, Effectiveness/Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework (12)—have been critical to the conceptualization of implementation outcomes. Researchers and practitioners have widely used both frameworks to evaluate implementation effectiveness (9, 13–15). For instance, other researchers have further developed implementation outcome instruments based on the IOF to establish measures matching these outcomes (16–18). The IOF is also included in the reporting standards and guidelines for implementation studies (9).

Yet, existing implementation outcome frameworks are not without limitations. First, prior research has emphasized the need for a broader conceptualization that includes, for example, dissemination outcomes, service implementation efficiency (8, 19), adaptation (13), and readiness as a precursor to early implementation outcomes (20). Expanding the conceptualization of implementation outcomes might also mean considering aspects, such as outcomes that refer to longer-term sustainability, spread and diffusion to other settings (21), and de-implementation (22). Second, reporting of implementation outcomes rarely considers their measurement attributes (5). Finally, there has also been some criticism regarding the practicability of the existing outcome measures for practice and policy stakeholders (5). As Martinez et al. (6) pointed out, whether implementation frameworks define different outcomes in the same way or define the same outcomes in different ways, they risk compromising a construct's validity and undermining the cross-research comparability of results.

This review aims to map and consolidate existing conceptualizations of implementation outcomes to develop an integrated framework. We use an interpretive synthesis approach to systematically compare how implementation outcomes have been conceptualized across multiple disciplinary perspectives to harmonize the conceptual meanings of these outcomes. We do this by considering the relatedness of outcome terminologies and conceptual definitions to elucidate their translatability, distinctions, and partial overlaps and identify how these elements contribute to explain components of a broader conceptual meaning and its associated characteristics.

Our paper contributes to both the academic literature and policy debate. More than a decade since the publication of IOF (10) and over two decades since the publication of RE-AIM (12), an integrated and disambiguated (re)conceptualization of implementation outcomes can help counter this divergence in the operationalization of outcomes, enable a more holistic and comprehensive understanding of implementation effectiveness or failure, and clarify how de-implementation and innovation diffusion/spread efforts fit with normative implementation evaluations. Harmonizing implementation outcomes terminology is crucial to support practitioners and policymakers in implementing innovation more effectively (15).

2 Methodology: interpretive synthesis review

Unlike conventional systematic review questions, our review question was loosely formulated, first, to consolidate conceptualizations of implementation outcomes and, second, to go beyond mere synthesis and provide holistic interpretations and re-conceptualization of implementation outcomes. To do this, we used a meta-ethnography approach (23) as the main approach, combined with the Behaviour or phenomenon of interest, Health context, Exclusions, Models, and Theories (BeHEMoTh) approach (24) for searching and selecting the relevant literature in the first instance.

Meta-ethnography is one of several approaches to undertaking interpretive synthesis (25–27). What distinguishes it is its facilitative synthesis approach, which recommends “discovering a ‘whole’ among a set of parts” (23). Noblit and Hare posit that it allows systematic comparisons involving translations of published work into each other, assuming that publications can be added together. The resulting interpretation from the synthesis results in additional layers of interpretations that are “metaphoric” and “not simply an aggregation of the interpretations already made in the studies [i.e., publications] being synthesized” (23, 28).

Initially, the application of the meta-ethnography method was limited to research based on ethnographical accounts; however, since then, it has been widely applied and considered suitable for interpreting diverse types of qualitative synthesis (26, 27). A recent adaptation of the method by the original developers clarifies that the method is “no longer limited to ethnographies” and has been successfully used with all forms of qualitative research (28).

The main reason we adopt the meta-ethnography approach in this review is because of one of its main strengths of allowing higher-order conceptual output that seeks to extend and enhance current conceptualizations or theories of the phenomenon of interest (25, 26); in our case, we are interested in expanding the conceptualization of implementation outcomes.

Meta-ethnography involves seven overlapping and iterative phases. Phase 1 (getting started) focuses on formulating the review research question. Phase 2 (deciding what is relevant to the initial interest) concerns being purposeful in searching and sampling publications for inclusion in the interpretive review. Phase 3 (reading the publications) marks the beginning of data extraction. Phase 4 (determining how the publications are related), phase 5 (translating the publications into one another), and phase 6 (synthesizing translations) are all concerned with how to approach the data analysis and the resulting interpretive synthesis of the included publications. Phase 7 (expressing the synthesis) concerns the dissemination of the synthesis output beyond publication and is outside the scope of this current output. In the following three subsections, we detail the application of phases 1–6 to our review, specifically, our approach for search and sampling strategy for identifying relevant literature that aligned with our review question, the results of the included publications, and our approach to data analysis and synthesis of the included publications.

2.1 Searching and sampling the literature

2.1.1 Initial systematic search for conceptual implementation outcomes—BeHEMoTh approach

The authors of the meta-ethnography approach recommend following a process of “specification,” which involves beginning with a purposive search that is then modified based on what the search reveals, as opposed to being overly prescriptive (28). However, this method does not specify how to sample the relevant literature and only recommends a purposive search. Thus, to identify relevant literature and as a starting point, we applied the BeHEMoTh approach to systematically search for and identify a comprehensive compilation of concepts related to implementation outcomes from diverse literature (24). The BeHEMoTh approach provides a structured way of specifying and identifying theories, models, frameworks, concepts, etc. (i.e., theoretical conceptualizations) in a systematic way.

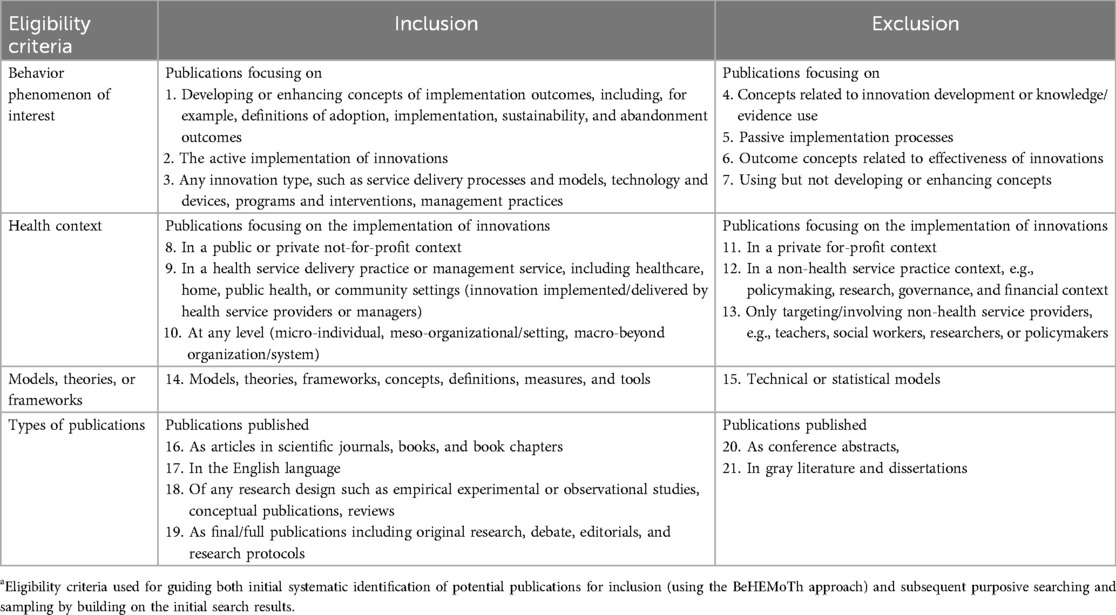

The approach applies one of two alternative strands of systematic searching with the aims of (i) identifying any occurrences of theoretical conceptualizations related to a review topic or the phenomenon of interest (theoretical conceptualizations occurrence searches) and (ii) consolidating and explaining how theoretical conceptualizations have been used in relation to a review topic (theoretical conceptualizations use searches). For this review, we applied the first strand of searching for theoretical conceptualizations because the main aim was to identify any occurrences of theoretical conceptualizations related to implementation outcomes and source a comprehensive compilation of concepts from different publications. For this strand, Booth and Carroll (24) suggested searching in the existing databases of the review team for incidental occurrences of relevant publications (i.e., articles and book chapters) to consider for inclusion and conducting a systematic electronic database search combining search terms for the review topic with terms for theoretical conceptualizations. The BeHEMoTh approach suggests following a structure (as outlined below, which is further laid out in Table 1) to derive eligibility criteria. These structured eligibility criteria are then used to inform the design of a search strategy by covering and combining the three aspects of (i) behavior/phenomenon of interest (Be), (ii) health context (He), and (iii) models (Mo) or theory (Th). For this review, these aspects are defined as follows:

• Behavior/phenomenon of interest: implementation outcomes;

• Health context: public/not-for-profit health service delivery or management; and

• Models or theory: models, theories, frameworks, concepts, definitions, measures, and tools (theoretical conceptualizations).

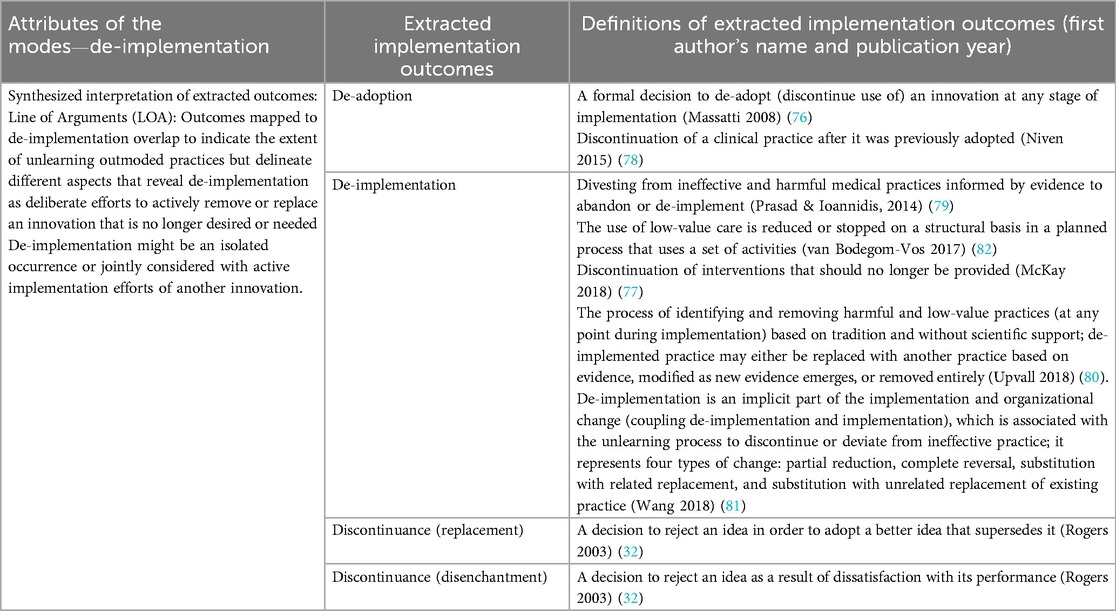

Table 1. Eligibility criteriaa for searching and sampling publications for inclusion in the interpretive synthesis review.

Following the BeHEMoTh approach, we designed an initial search strategy based on our eligibility criteria. The following electronic databases were systematically searched: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Global Health, HMIC, Business Source Complete, and Social Policy and Practice. These databases cover multiple disciplines, including medical and health sciences, implementation science, and social sciences, including organization and management research. As our review aimed to identify conceptualizations of implementation outcomes (which might be presented as or part of theories, models, frameworks, or other standalone conceptualizations) published in peer-reviewed journals or books, we did not include gray literature. The search strategy was adjusted to the different databases, combining subject headings and free-text terms for behavior/phenomenon of interest (implementation outcomes) AND health service context AND theoretical conceptualizations. For the behavior/phenomenon of interest, we also searched for different descriptors of implementation outcomes, e.g., level, strength, intensity, depth, or extent. Searches were limited to articles and book chapters published in English from 2004 onward. We chose this year as it marks the seminal publication by Greenhalgh et al., which is widely recognized as a foundational work in the field of implementation science in healthcare (29).

The initial search and sampling of publications for inclusion, using the BeHEMoTh approach, was carried out in December 2020. Citations were managed using EndNote X9 and Rayyan (30). Citations were independently double-screened by three reviewers, with one reviewer screening 100% (AZ and ZB) and the other two reviewers (AZ and CS) screening 50% each for both titles/abstracts and full texts. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus within the review team. As the BeHEMoTh approach only offers a starting point for identifying potential theoretical or conceptual publications to consider for inclusion, we carried out additional purposive sampling based on the results of this initial systematic search, as detailed below.

2.1.2 Subsequent purposive search and sampling

After the initial strategy of systematically searching for conceptual implementation outcomes for assessing implementation efforts using the BeHEMoTh approach, the second strategy we employed involved the following techniques to purposively identify relevant publications for inclusion: we included publications by hand-searching reference lists of included publications, reviewing key textbooks in the fields of implementation science and innovation research, and citation tracking of included publications between January 2021 and January 2022. In cases where an included publication was found to further develop or enhance the conceptualization of an outcome, we ensured to source the original publication to consider it for inclusion. After exhausting relevant citation sources connected to already identified publications, we proceeded with purposive searching for publications, e.g., using Google Scholar, on specific outcome concepts we identified during data analysis to fill gaps in the synthesis, enrich the analysis, and include newer publications. These searches were carried out iteratively throughout the later stages of our analysis between February 2022 and September 2023.

To examine publications identified during the subsequent purposive search and sampling for inclusion, one reviewer screened all publications to determine whether they (i) developed implementation outcome concepts/contributed to their theoretical conceptualizations or (ii) mentioned/applied but not (further) developed theoretical conceptualizations of outcomes. Publications in the first group were included in the synthesis; publications in the second group were excluded. For the excluded group, key original publications contributing to theoretical conceptualizations mentioned or applied in these publications were retrieved and included in the synthesis. The excluded group contained, for example, empirical articles/chapters that used theoretical conceptualizations in question to inform data analysis but did not contribute to their further development.

2.1.3 Data extraction

Data extraction activities (phase 3 of the meta-ethnography approach) entail reading the identified publications closely. It overlaps with the other phases, as iterative close reading of the included publications is undertaken throughout the review process. Second-order concepts, which Noblit and Hare termed “interpretative metaphors” (23)—in our case, implementation outcomes—were extracted from all publications considered eligible for inclusion. In this review, we extracted data on the following aspects of the second-order conceptual implementation outcomes described in each publication: outcome labels, outcome definitions, and outcome characteristics/attributes. In total, we extracted 55 individual implementation outcome labels. We excluded further publications if they did not include sufficient data on outcome aspects. In addition, we also extracted the following data on publication characteristics: first author's name; publication year and title; publication aim/research question; design/method; discipline (e.g., medical and health sciences, implementation science); application field (e.g., wider healthcare system, public/community health); and country, region, and theory name (where applicable). Data extraction was conducted by two members of the research team (AZ and ZB).

2.2 Included publications

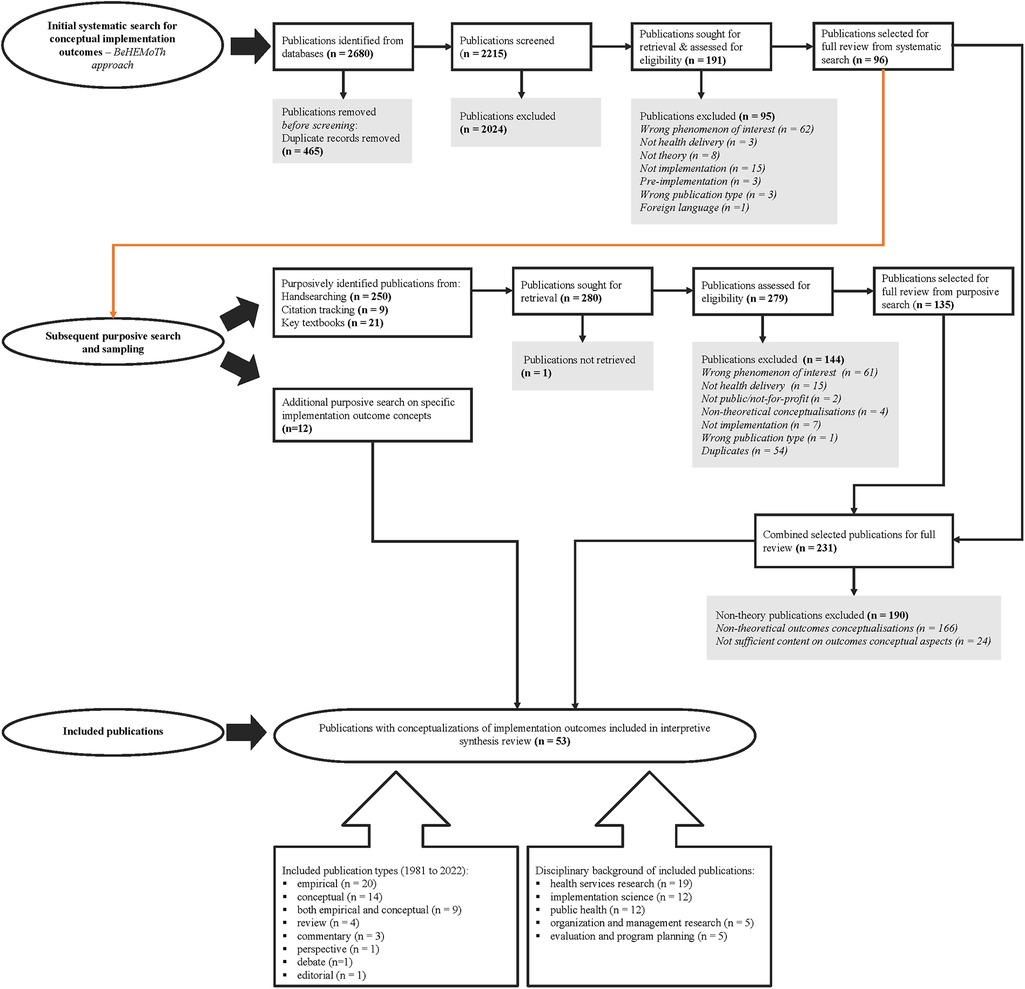

The search and sampling of the literature resulted in the inclusion of 53 publications. Of these 53 included publications, 41 were identified via the initial systematic search using the BeHEMoTh approach across eight electronic databases, along with purposive sampling via hand-searching, citation tracking of included publications, and review of key textbooks. The other 12 included publications were identified via an additional purposive search on specific implementation outcomes. Figure 1 presents an overview of the process we followed in sourcing and identifying potential publications for inclusion and a summary of key characteristics of the included publications.

Figure 1. Flowchart of publications’ search and selection processes. BeHEMoTh, Behaviour or phenomenon of interest, Health context, Exclusions, Models, and Theories.

The publication year of the 53 included publications ranged from 1981 to 2022. Most of the publications were theoretically relevant empirical publications (n = 20), followed by conceptual publications (n = 14), with the rest being publications that were both empirical and conceptual (n = 9), reviews (n = 4), commentaries (n = 3), a perspective ( n = 1), a debate piece (n = 1), and an editorial (n = 1). The disciplinary backgrounds of the included publications spanned a range of fields, including health services research (n = 19), implementation science (n = 12), public health (n = 12), organization and management research (n = 5), and evaluation and program planning (n = 5). The indicated application field of the included publications commonly included evaluation of (evidence-based) innovations (n = 42), organizational change (n = 5), quality improvement (n = 5), and reporting guidelines (n = 1).

2.3 Data analysis and synthesis

As mentioned in the above overview of the methods, meta-ethnography suggests the synthesis of interpretations extracted from the included publications (e.g., conceptual implementation outcomes and the associated explanations) in a manner that generates additional layers of interpretation during a process of translating publications into one another. To achieve this, Noblit and Hare suggested three forms of translation: reciprocal translational analysis (RTA)—applicable when the extracted theoretical conceptualizations of the phenomena of interest (in our case, implementation outcomes) are directly translatable into one another; line of arguments (LOA)—applicable in cases where there is overlap, but a closer comparison reveals that the extracted concepts address different aspects of a larger explanation; and refutational synthesis (RS)—applicable when there are some contradictions between extracted concepts, i.e., they do not add up (23, 28). For RS, a further step is to substantively consider the implied relationships between competing explanations of extracted concepts and include them as part of the synthesis (23). For example, we applied RTA in cases where two extracted outcomes were deemed translatable, thus conveying the same conceptual explanation—“implementation” and “implementation quality.” We applied LOA, for example, in the interpretive synthesis of “institutionalization” and “sustainability” outcomes, which overlap in their conceptualizations but delineate different aspects of what it means to integrate an innovation. We applied the RS translation approach to distinguish between the extracted outcomes—“penetration” and “reach” because even though, at the surface level, the conceptual definition of these two concepts implied some degree of overlap, their detailed conceptual explanations did not sufficiently satisfy placing them under the same category.

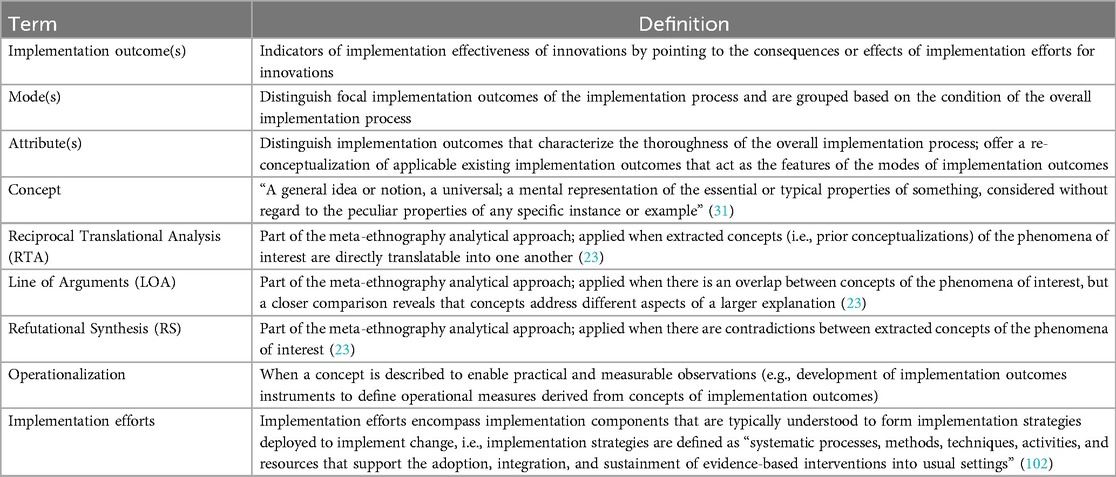

We began with a tentative analysis of the extracted second-order concepts of implementation outcomes based on similarities in their conceptual meanings using RTA and LOA translation approaches as appropriate as analytical lenses to examine their relatedness and translatability. The application of RS is more of a consequential step that emerges from applying the other two forms of translation (RTA and LOA). Applying the latter two indicates the necessity to substantively consider the implied relationship between competing conceptual explanations of the outcomes. Thus, implied refutations between the conceptual meanings of extracted outcomes led us to formulate distinct categories and establish boundary conditions between categories. We tentatively categorized extracted outcomes that were either translatable or exhibited overlapping conceptualizations into emergent third-order constructs, which we eventually labeled as either modes or attributes. We then conducted a more detailed inspection of conceptual definitions and explanations of the extracted outcomes to produce synthesized, broader conceptual definitions of the individual outcomes clustered within the modes and attributes. We report the findings and analysis outputs of the individual modes and attributes in the following section. Table 2 lists key terms we used in this review and their definitions to serve as a reference point.

3 Findings and analysis: integrated re-conceptualization of implementation outcomes

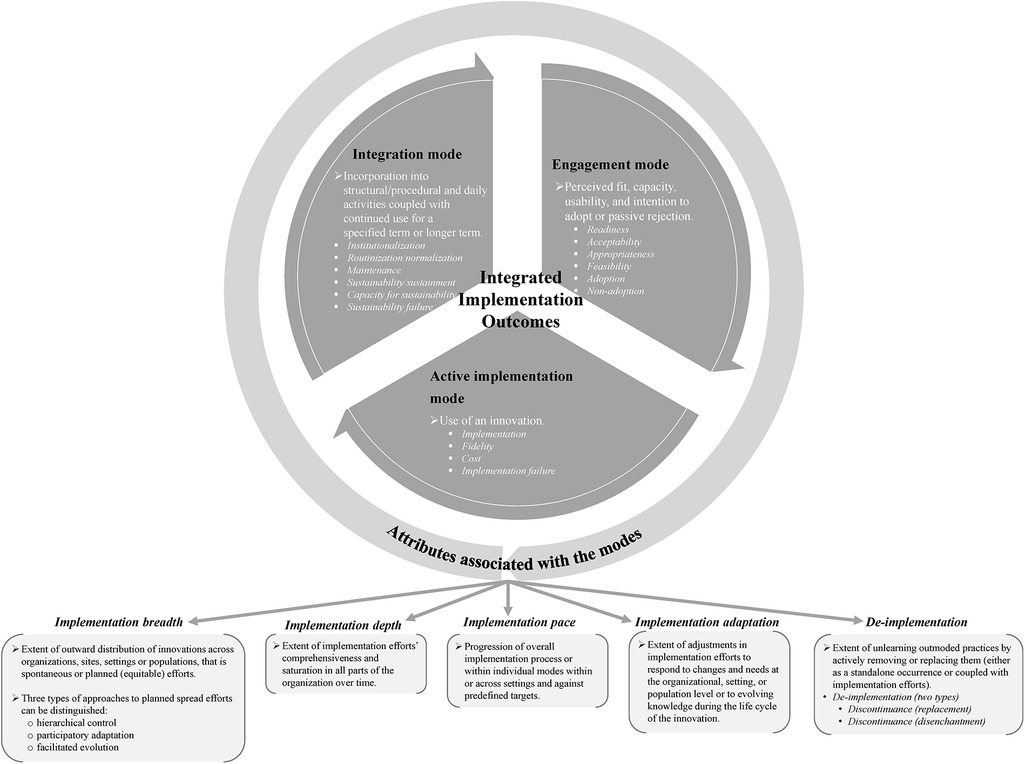

Implementation outcomes are understood to function as indicators of the implementation effectiveness of innovations. After reviewing their existing conceptualizations, we mapped and consolidated synthesized interpretations to extend established conceptualizations of implementation outcomes. We conceptualized two main components of implementation outcomes as modes and attributes by considering the relationships between and across the outcomes and their roles in the overall process of implementation efforts. Based on the analysis of the synthesized implementation outcomes, modes refer to distinct conditions of the implementation process. Modes specify focal implementation outcomes of the overall implementation process. Attributes distinguish implementation outcomes that characterize the thoroughness of the overall implementation process. Attributes classify individual implementation outcomes to indicate the extent of depth, breadth, progression, and adaptation of implementation efforts and the extent of de-implementation (e.g., the extent of unlearning) associated with the modes of implementation outcomes. While the modes refer to implementation outcomes at the core of implementation efforts, the relevance of evaluating outcomes linked to the attributes will vary depending on the circumstances and requirements of implementation efforts.

The modes comprise engagement, active implementation, and integration. The attributes associated with the modes are implementation depth, implementation breadth, implementation pace, implementation adaptation, and de-implementation. In the following subsections, we discuss the synthesized extracted implementation outcomes concerning each mode and attribute and how they add to the conceptual clarity and/or advance re-conceptualization of implementation outcomes.

3.1 Modes of implementation outcomes

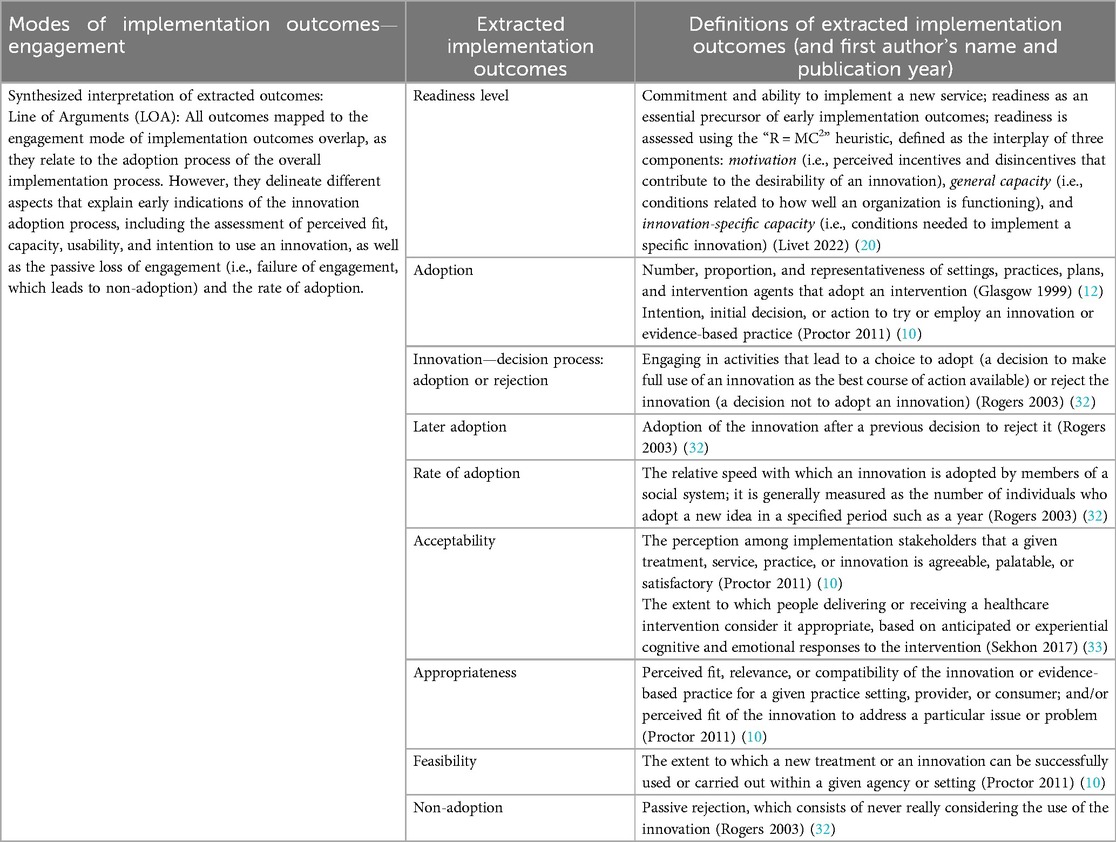

3.1.1 Engagement mode

Engagement mode explains the perceived fit, capacity, usability, and intention to adopt an innovation or a passive loss of engagement (i.e., failure of engagement, which leads to non-adoption) and adoption rate within or across settings. When we examined the conceptual definitions of the implementation outcomes related to the “adoption” process of the overall implementation process, the lines-of-argument analytical approach (i.e., outcomes overlap but delineate different aspects of the adoption process) was most appropriate to compare conceptual definitions. However, we deemed creating the term “engagement” to label this mode of implementation outcomes, rather than adopting the term adoption, to be able to capture the holistic meaning conveyed by all the outcomes mapped under this mode (Table 3).

As shown in Table 3, the outcomes mapped to this mode represent the initial or later decision to adopt an innovation. These include “adoption” (10); understanding “proportion” of adopting units/agents or “rate of adoption” (12, 32); indication of “readiness level” (20); perceptual outcomes, such as—“acceptability” (10, 33) and “appropriateness” and “feasibility” (10), which are known to predict adoption (15); and “non-adoption”—defined as a “passive rejection that consists of never really considering the use of the innovation” (32). The engagement mode of implementation outcomes thus integrates outcomes for evaluating the initial commitment or promise to try an innovation, the related perceptions and activities that lead to this commitment, or the unintended/undesired consequence of the adoption process. The engagement mode also includes outcomes that indicate the proportion and rate of the commitment by the engaged units or agents.

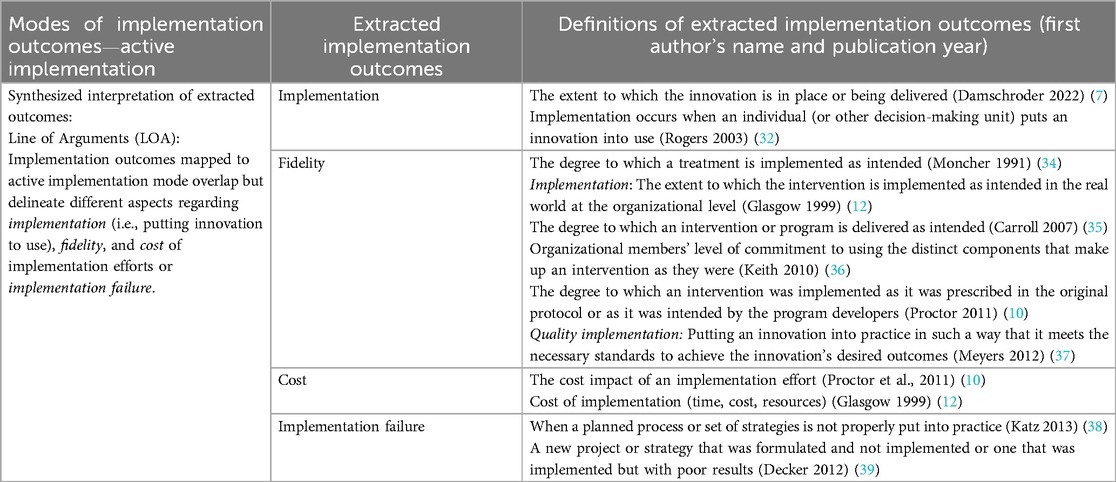

3.1.2 Active implementation mode

The active implementation mode represents implementation outcomes that indicate the use (or non-use) of an innovation, along with considering the level of fidelity and the associated implementation cost. This mode typically follows the engagement mode, as a natural sequential step of the implementation efforts is to proceed with active implementation of the innovation once a sufficient level of engagement has been established. The cluster of implementation outcomes we synthesized under the active implementation mode conveys a general or specific conceptual meaning (Table 4). The implementation outcome labeled as “implementation” (7, 32) conveys a general or broader meaning, referring to the extent to which an innovation is being delivered, put into use, and operationalized to signal the transition to the active implementation mode (7, 32).

In contrast, outcomes that convey a specific meaning of active implementation may overlap, but a comparison reveals that they capture relevant and distinct aspects that need to be considered when innovations are put into use. These outcomes are “fidelity” (10, 12, 34–37), “cost” (10, 12), and “implementation failure” (38, 39). The specific conceptual meanings of these outcomes indicate the degree to which the innovation was delivered as intended (fidelity) (10, 12, 34–37), taking stock of implementation cost (cost) (10, 12), and improper execution of implementation plans/strategies or poor results after active use of the innovation, which leads to reverting to the pre-implementation state (implementation failure) (38, 39). Some authors use the labels “implementation” (12) and “quality implementation” (37) to refer to a conceptual definition that is consistent with the conceptual meaning of fidelity. Thus, we translated these two individual outcomes as synonymous with fidelity, as similarly defined by the other authors (10, 34–36). Taken together, we propose that the active implementation mode represents a conceptual reduction of outcomes under this cluster, which serves as a necessary transitional mode between the engagement mode and integration mode, as discussed below, that may lead to routinized and enduring desired consequences.

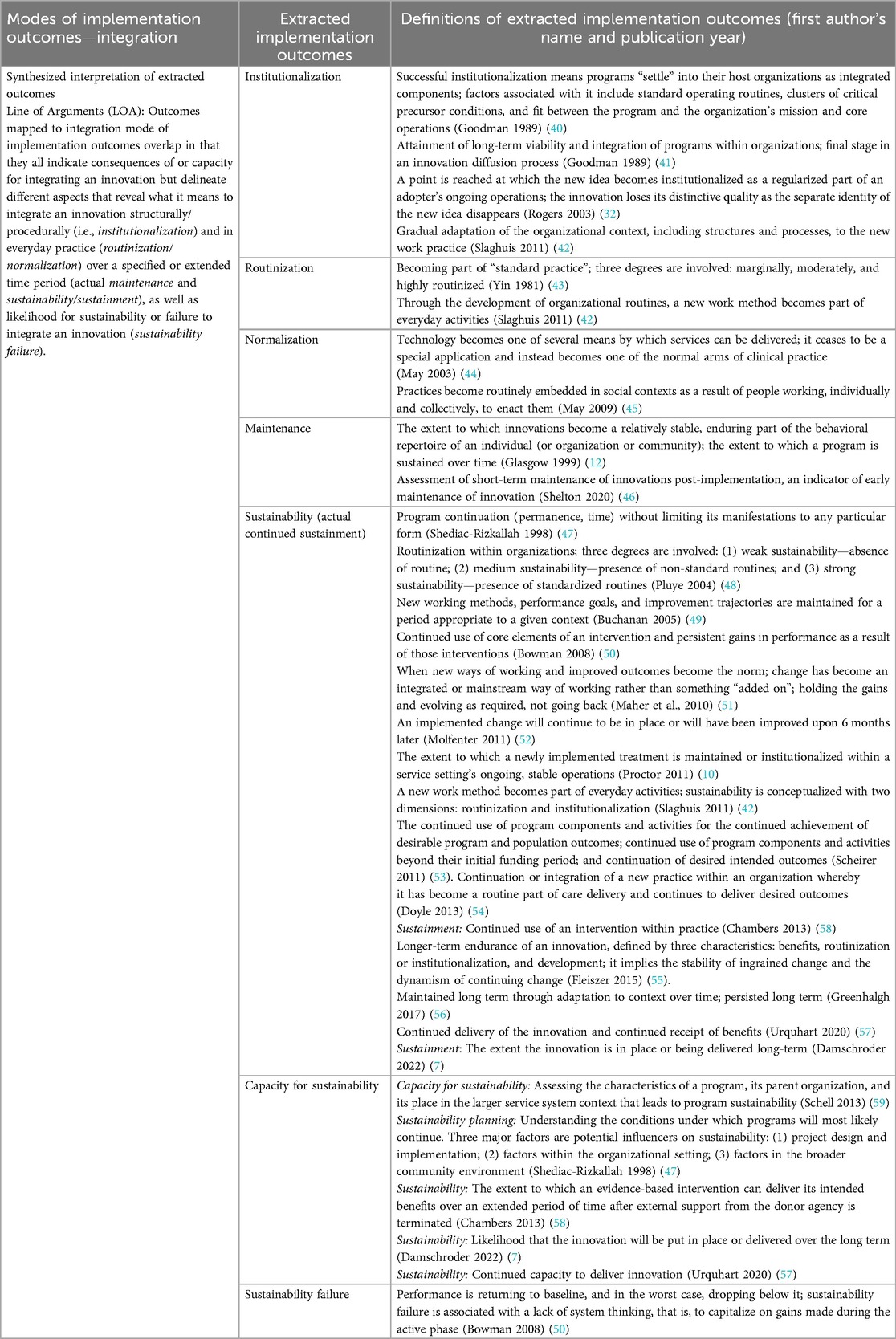

3.1.3 Integration mode

The integration mode reflects implementation outcomes that arise when an innovation is embedded—specifically, its structural and procedural integration as enacted in everyday practice over a defined (or extended) period. This mode also nuances assessing the likelihood of continued integration of the innovation. Conversely, it also points to a failure to integrate an innovation.

The outcomes mapped to the integration mode (Table 5) are typically all observable, in more tangible ways, or have more resonance following the effective active implementation of an innovation. Thus, they overlap in this way in their conceptual meanings. However, there are some distinctions that foreground five main characteristics of implementation outcomes associated with the integration mode, which are (i) integration in relation to an organization's structural and procedural conditions (i.e., “institutionalization”) (32, 40–42); (ii) integration in relation to conditions of everyday practice [i.e., “routinization” (42, 43) or “normalization” (44, 45)]; (iii) actual integration in relation to a specified or longer term timeframe [i.e., “maintenance” (12, 46), “sustainability” (10, 39, 42, 47–57), or “sustainment” (7, 58)]; (iv) potential integration in relation to capacity for continued delivery [i.e., “capacity for sustainability” (59), “sustainability planning” (47), or “sustainability” (7, 57, 58)]; and (v) failure to integrate an innovation [“sustainability failure” (50)].

Hence, the first two aspects of the integration mode refer to features of an organization's context. The first aspect, institutionalization, is more commonly associated with the innovation becoming part of the organization's procedural practices, core competencies, and the values of organizational members (42), as well as being regularized within an organization's ongoing operations (32, 40, 41). The second aspect, routinization and normalization, refers to an innovation becoming part of the organization's everyday activities (42–45). The third aspect of integration, which we associate with maintenance and sustainability/sustainment outcomes, conveys a comprehensive conceptual meaning that not only refers to the innovation being officially in place (institutionalization) and use in daily activities (routinization/normalization) but also to the extent the innovation is integrated for a specified term (short-term maintenance) (12, 46) or a longer-term (long-term sustainability) (7, 10, 39, 42, 47–58). The fourth aspect conceptually delineates what it means to prepare for and determine continued capacity to integrate an innovation. The final aspect of the integration mode refers to a failure to embed and maintain gains achieved during the active implementation mode (sustainability failure) (50).

Notably, in the included publications, the concept of “sustainability” is used interchangeably to refer to either an outcome that indicates the actual continued delivery of an innovation or the potential for continued delivery (i.e., capacity for sustainability). Of the 16 included publications in our review that conceptualize what it means to evaluate outcomes related to sustaining an innovation, 14 use the “sustainability” concept to explain the actual continued delivery of an innovation (7, 10, 42, 47–52, 54–58), whereas only two publications make a conceptual distinction between “sustainability” and “sustainment”—reserving sustainability for assessing capacity to sustain the innovation and sustainment for the actual continued use of the innovation (7, 58). In addition, in 5 of the 16 publications, authors offer conceptual clarity on assessing capacity for sustainability, albeit using varied concept labels (Table 5) (7, 47, 57–59).

3.2 Attributes associated with the modes of implementation outcomes

3.2.1 Implementation depth

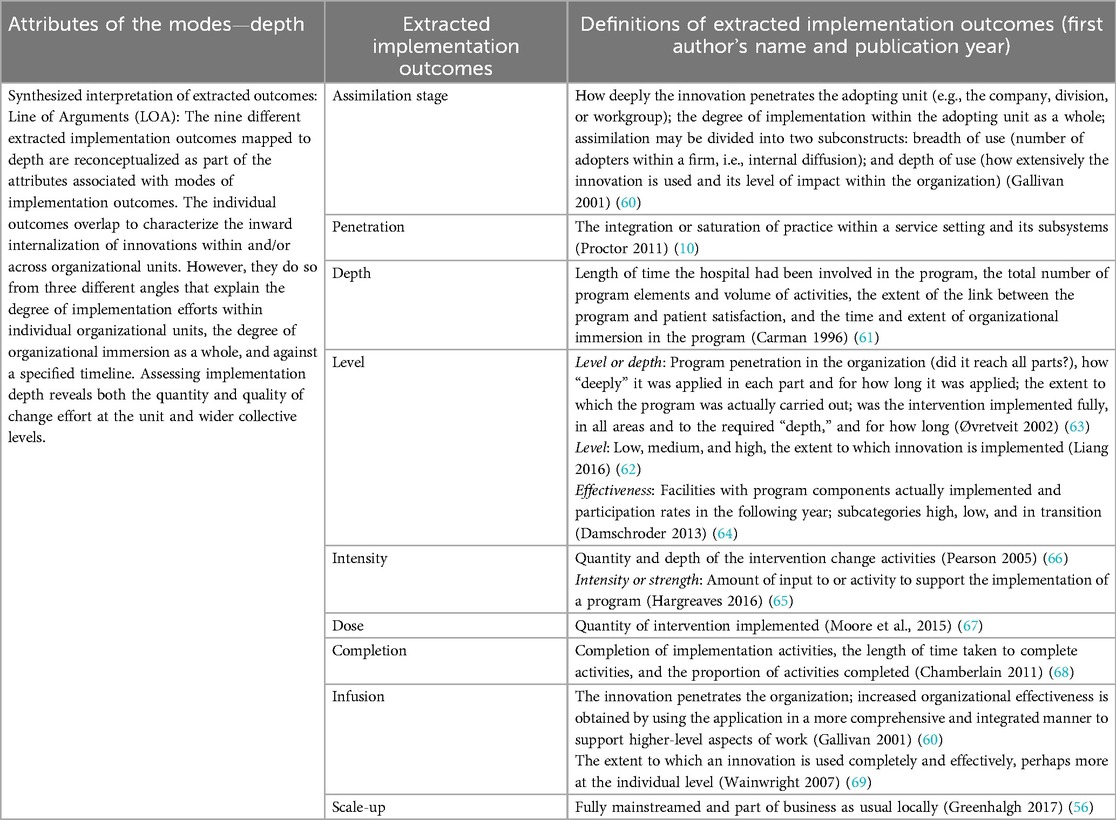

Implementation depth is defined as the inward internalization of an innovation within and/or across specific organizational units and indicates the innovation's temporal progression and degree of implementation in three dimensions: (i) the extent of use within each part of an organization (i.e., quantity and quality of implementation efforts in each part); (ii) the reach of the innovation in all parts of an organization (i.e., organizational immersion as a whole); and (iii) the amount of time taken to achieve each of these two dimensions of depth (i.e., depth of implementation against a timeline). The extracted implementation outcomes that convey this integrated conceptual meaning have definitions that overlap but emphasize different aspects of implementation depth.

With regard to the terminology used by authors (Table 6), the outcomes that explain both the depth of implementation efforts in each part and the whole organizational immersion are referred to in the publications included as “assimilation” (60) and “penetration” (10). Outcomes such as “depth” (61), “level” (62, 63), and “effectiveness” (64) are also used to refer both to the part and the whole and include time dimension in their conceptualizations. In contrast, outcomes such as “intensity” or “strength” (65, 66), “dose” (67), “completion” (68), “infusion” (60, 69), and “scale-up” (56) mainly focus on explaining the depth of implementation at the organizational level or the whole.

Outcomes mapped to implementation depth are defined as ratings that indicate implementation effectiveness by assessing facilities that actually implemented an innovation's components (64); completion of implementation activities and proportion of activities completed (68); integration of practices within a setting and its subsystems (10); the reach across all parts of an organization, the depth of application within each part of an organization, and the extent to which an innovation is implemented (63); the penetration of the innovation into an organization (10, 60, 63); and the timeframe and extent of organizational immersion (61). As an attribute of the modes, the evaluation of implementation depth offers insight into the extent of comprehensiveness and saturation of implementation efforts across all parts of the organization over time.

3.2.2 Implementation breadth

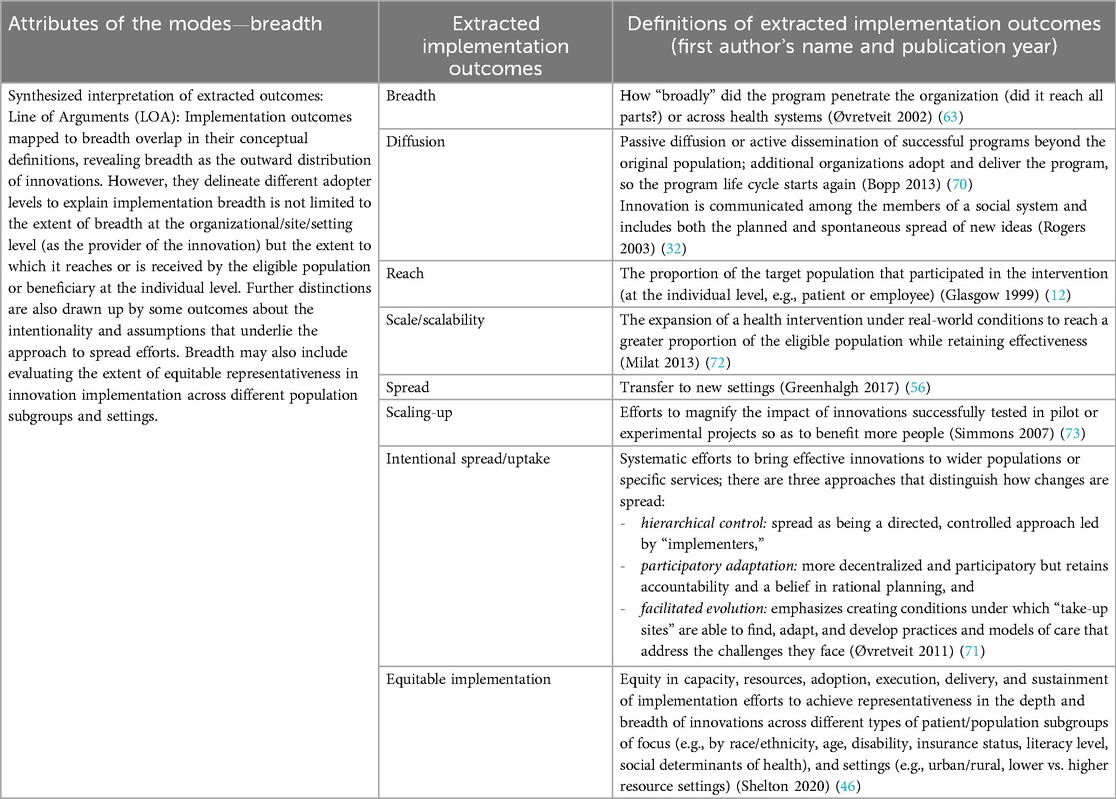

We interpret implementation breadth as a second attribute of the modes of implementation outcomes, defined as the extent of outward distribution of innovations across organizations, sites, settings, or populations, encompassing both spontaneous and planned efforts coupled with equitable distribution. This synthesized conceptual meaning of implementation breadth is based on the similarities we observed across related implementation outcomes extracted from the included publications. However, some differences foreground three main aspects of implementation breadth: breadth at the organization/site/setting level, breadth at both the organization/site/setting level and population level, and breadth at the population level.

The extracted implementation outcomes labeled as “breadth,” referring to the reach of an innovation across all parts of an organization or health systems (63), and “spread,” denoting the transfer of an innovation to new settings (56), explicitly capture the evaluation of breadth at the organizational/site/setting level. The extracted outcomes labeled as “diffusion,” which refers to the dissemination of an innovation beyond the original organization/site/setting/population (70), and “intentional spread/uptake,” defined as systematic efforts to extend effective innovations to wider populations or specific services (71), explicitly reflect breadth both at the organization/site/setting level and the population level.

In contrast, the extracted outcomes labeled as “reach,” referring to the proportion of the target population participating in intervention (12), “scale/scalability,” indicating expansion of an innovation to reach a greater proportion of the eligible population (72), “scaling-up,” denoting efforts to increase the impact of innovations to benefit more people (73), and Roger's conceptualization of “diffusion,” indicating communication of an innovation among the members of a system (32), all foreground assessment of breadth at the population level in their conceptual meanings. The final outcome mapped under implementation breadth—“equitable implementation”—complements all the other outcomes in this category by pointing to the assessment of equity representativeness in the implementation of innovations across different population subgroups and settings (46) (Table 7).

When considered together, the interpretive synthesis of outcomes mapped to implementation breadth reveals that breadth can be observed at the organization/site/setting level or the population level. Furthermore, the outcome “intentional spread/uptake” further encapsulates the intentionality behind the implementation breadth of innovations (i.e., whether it is linked to passive/spontaneous or active/planned efforts). In cases where breadth is linked to active spread efforts, these three types of spread approaches—hierarchical control, participatory adaptation, and facilitated evolution—may explain assumptions that underlie active/planned spread efforts (71).

The evaluation of breadth may be appropriate during the engagement and active implementation modes of implementation outcomes, as authors conceptualizing the synthesized outcomes of breadth refer to bringing, expanding, or further adopting an innovation that has been successfully tested in a pilot project or at a small scale to new adopters. This suggests it is possible to conceive evaluating the breadth of the engagement mode to gauge the early successes of a spread effort. Likewise, in the synthesized conceptual meanings of breadth, authors also refer to the number of adopters who used, participated in, or received the innovation or the extent to which the innovation has reached, thus again suggesting the pertinence of evaluating the breadth of active implementation.

Something worth noting is some of the ambiguity we encountered in the labeling of implementation outcomes or their conceptual definitions provided by authors. An example of the first type is the use of similar outcome labels that refer to distinct conceptual meanings, such as “scale-up,” “scaling-up,” and “scale/scalability.” In our synthesis, we mapped “scale-up” under implementation depth, as Greenhalgh and colleagues conceptualized “scale-up” as a limited local spread within an organization (56). In contrast, we mapped “scaling-up” and “scale/scalability” under implementation breadth because these outcome labels were used to describe active or intentional spread where efforts are made to expand innovations beyond the original site (72, 73). However, as also acknowledged by other authors (71), we noted that the outcome concepts “scale” and “spread” are used interchangeably in the literature concerning the evaluation of implementation efforts.

The second type of ambiguity we encountered was the conceptual definitions provided by Øvretveit and Gustafson (63) for the extracted outcome “breadth,” where it is used to imply both internal (i.e., reach within all parts of the organization) and external (i.e., reach across organizations) breadths of implementation. However, we limited mapping breadth as an extracted outcome under the derived attribute—breadth—because the other extracted conceptual outcomes—“level/depth”—by the same authors, which we mapped under implementation depth, explain the conceptual meaning of internal breadth (i.e., depth).

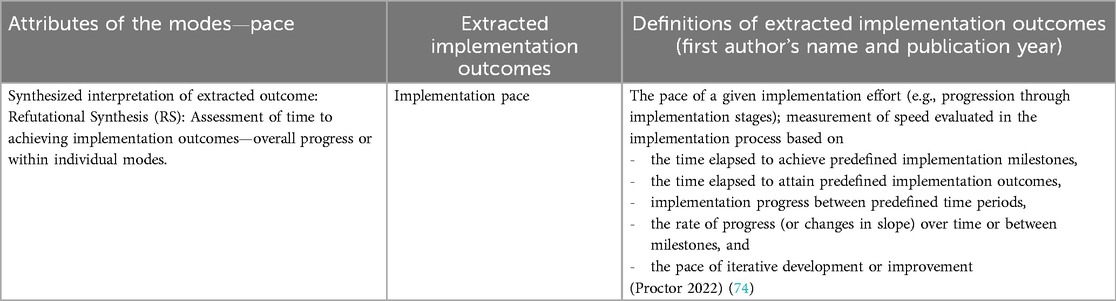

3.2.3 Implementation pace

Implementation pace, the third attribute of the modes of implementation outcomes, is defined as the rate of progression of the overall implementation process measured against predefined milestones or the pace at which key milestones are achieved within the implementation modes (74). We only identified one publication by Proctor and colleagues that develops a conceptualization of how to assess “pace” in implementation efforts, included as part of a broader concept—Framework to Assess Speed of Translation (FAST) (74). In this framework, measuring pace is conceptualized to include the time from an innovation's availability to adoption, the time required to train providers to deliver innovations with fidelity, and the time to scale-up within an organizational unit or a setting (74) (Table 8).

The speed of implementation is an ambiguous concept that may refer to (i) the pace of research translation processes, (ii) the pace of implementation efforts, (iii) the pace of achieving service outcomes, and (iv) the pace of achieving clinical outcomes (74). The publication included in this review focuses on the conceptual development of pace in the first two situations. Including implementation pace as part of evaluating a given implementation effort may be appropriate in scenarios with a clear case or need to accelerate implementation efforts (such as during public health crises, e.g., during the COVID-19 pandemic). Incorporating the assessment of implementation pace may also be relevant when rapid and agile implementation approaches are used, where timely implementation of innovations is a critical component (75).

3.2.4 Implementation adaptation

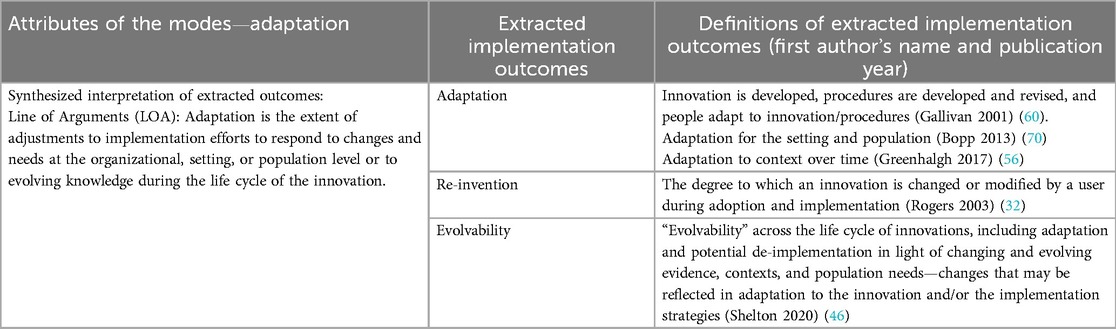

We propose implementation adaptation as the fourth attribute of the modes of implementation outcomes. Based on the synthesized conceptualizations of the related extracted outcomes, we define it as the extent to which implementation efforts are adjusted in response to needs and changes at the organizational/setting level or population level or in response to evolving knowledge during the life cycle of the innovation.

The individual extracted implementation outcomes linked to this attribute all overlap in their conceptualizations (Table 9): “adaptation”—defined as adapting implementation efforts related to contextual preparation that may involve modification to the innovation and/or the implementation strategies that enable the use of the innovation (56, 60, 70); “re-invention”—defined as the degree to which an innovation is modified by a user (32); and “evolvability”—defined as evolvability of innovations’ implementation across all phases, which may include adaptation (and potential de-implementation) in response to evolving and changing knowledge (46).

Implementation adaptation as a process is an important consideration often part of implementation efforts. It helps ensure implementation flexibility and contextualization to improve the chances of implementation success (56). However, as an implementation outcome, it sheds light on gauging a balance between adaptation and fidelity (70).

3.2.5 De-implementation

How should de-implementation be conceptually conceived in relation to implementation? Based on the synthesized conceptualizations, we identify de-implementation as an attribute of the modes of implementation outcomes that indicate the extent of unlearning outmoded practices by actively removing or replacing them. The publications included in this synthesis consider de-implementation either a standalone process/outcome or in conjunction with the overall implementation process of putting another innovation in place. Thus, de-implementation is classified into two types: disenchantment (i.e., active rejection) of an existing practice/previously adopted innovation (32, 76–81) or substitution (i.e., replacement) of an existing practice/previously adopted innovation with a newer innovation that is perceived to be better (32, 77, 80–82).

In both of these circumstances of whether de-implementation is triggered by disenchantment or substitution, a common feature of the extracted outcomes—“de-implementation” (77, 79–82), “de-adoption” (76, 78), and “discontinuance (replacement or disenchantment)” (32), which we map under the attribute “de-implementation”—is their focus on deliberate efforts to actively remove or replace (to some extent or completely) a previously implemented innovation that is no longer desired or needed (Table 10). However, not all the conceptualizations provided for these outcomes are directly translatable.

As shown in Table 10, some of these outcomes overlap in their conceptual definitions. However, some conceptualizations stopped at framing de-implementation as a standalone/isolated occurrence, implying it to be the opposite of implementation efforts (76, 78, 79). Others, however, go beyond to argue that de-implementation and implementation are not always opposites or mirror images but instead propose to conceptually, practically, and logistically couple or jointly consider de-implementation and implementation since de-implementation is an implicit part of implementation and organizational change in the general sense (81, 82). The main reason is the inherent unlearning when implementing new practices (77, 81, 82). Thus, considering de-implementation in conjunction with implementation efforts at various time points and modes (i.e., engagement, active implementation, and integration modes) could positively contribute to the implementation effectiveness of new practices. For example, Wang et al. stated that “coupling may result in effort-neutral change and considerably raise the likelihood for change, as intended” (81). McKay et al. also made a similar point by stating that in the face of technological and scientific advancement, “stopping [outmoded] existing practices to make room for better solutions becomes a necessity” (77).

As such, this conceptual synthesis of de-implementation suggests that the extent of unlearning has direct implications for achieving outcomes across the engagement, active implementation, and integration modes and the associated implementation outcomes when replacing an existing innovation or implementing another adjacent innovation within a setting. Thus, we suggest de-implementation as part of the attributes of modes of implementation outcomes to be integral to implementation efforts, given the risk of creating burdensome complexity by adding innovations to a service or system without, at the same time, removing other outmoded practices.

4 Discussion

We have developed an integrated re-conceptualization of implementation outcomes of innovations (Figure 2). We conceptualize three modes of implementation outcomes (each refers to a distinct condition): engagement mode (perceived fit, capacity, usability, and intention to adopt or passive rejection of an innovation), active implementation mode (use of an innovation along with indications of the degree of fidelity, and cost of implementation), and integration mode (integration into structural/procedural and daily activities coupled with continued use over time). We further conceptualize five attributes associated with the modes of implementation outcomes: implementation depth (within a setting), implementation breadth (across settings), implementation pace (time to achieving implementation outcomes—overall progresses or within individual modes), implementation adaptation (responsive adjustments in implementation efforts at the organizational/setting/population level), and de-implementation (active removal or replacement efforts to unlearn outmoded practices that might be coupled with implementation efforts of another innovation). Together, the modes and attributes reveal an integrated framework of implementation outcomes that offers conceptual reductions of existing outcomes to clarify the relationships and distinctions between the individual outcomes in terms of translatability and complementary aspects.

As presented in Figure 2, the modes and attributes harmonize conceptual meanings of existing implementation outcomes by specifying the pertinence of the outcomes as either focal outcomes or outcomes characterizing the thoroughness of the implementation efforts. The engagement, active implementation, and integration modes delineate and structure relevant sets of implementation outcomes that we argue present core implementation outcomes of implementation efforts and are most salient under particular conditions during the implementation process journey, albeit being an iterative and not an entirely linear process. The focal implementation outcomes that are connected to the different modes are “readiness,” “acceptability,” “appropriateness,” “feasibility,” and “adoption” or “non-adoption” (engagement mode); “implementation,” “fidelity,” and “cost” or “implementation failure” (active implementation mode); and “institutionalization,” “routinization”/“normalization,” and “maintenance”/“sustainability”/“sustainment,” “capacity for sustainability,” or “sustainability failure” (integration mode). In comparison, the attributes of the three modes cut across the modes to specify the degree of implementation depth, breadth, pace, adaptation, and de-implementation achieved with implementation efforts.

4.1 Theoretical contributions

Our review contributes to theory in three ways. First, it clarifies and consolidates the diverse range of terminologies and conceptual meanings of implementation outcomes by considering their relatedness. We distinguished existing conceptualizations of implementation outcomes as either belonging to modes of implementation outcomes or serving as attributes of the modes. Within each mode or attribute, we translated similar outcomes into one another to achieve conceptual reductions of translatable terminologies and definitions or delineated the outcomes that partially overlap but reveal additional conceptual layers of the overarching mode or attribute. We further considered how the range of extracted outcomes contradict or refute one another to draw distinctions that elucidate the boundary conditions between the modes and attributes. It is important to distinguish outcomes for evaluating modes vs. attributes because the implementation outcomes linked to the modes present sets of outcomes fundamental to indicating the consequences of implementation efforts. The attributes reinforce the modes.

In addition, the modes are associated with distinct conditions of the implementation process that indicate the progression of the implementation efforts, while the attributes cut across the life cycle of the innovation. Such conceptual distinctions can help guide targeted ascertainment of the success or failure of implementation efforts. In contrast, conceptual explanations of outcomes specified in existing implementation outcome frameworks are dispersed across the diverse range of conceptual frameworks in our synthesis. For example, they commonly focus on addressing either short-term to mid-term implementation but not all aspects of the integration mode (e.g., short-term maintenance as well as longer-term sustainability) (46), implementation (15) but not de-implementation (22), or depth (local implementation) but not breadth (global spread) (21).

Second, we broadened the conceptualizations of implementation outcomes by conceptualizing the additions of overlooked or emerging outcomes absent in prominent implementation outcome frameworks. We distinguished the conceptualization of these additional conceptual outcomes by including them within the modes, e.g., assessment of readiness level, or as part of the attributes, i.e., pace, adaptation, and de-implementation. These additions consolidate and build on recent efforts to extend the RE-AIM and IOF frameworks (7, 15, 46, 74, 83). These insights address increasing recognition to redefine the scope of the outcomes to meet challenges related to evaluating implementation in complex healthcare systems and related key issues (8, 15, 19, 84). In the proposed integrated framework, we also included within the conceptualizations of the modes outcome concepts that may reveal abandonment of implementation efforts, i.e., non-adoption, implementation failure, or sustainability failure.

Third, we clarified and mapped the role of existing implementation outcomes in analyses or evaluations of implementation efforts by explicitly distinguishing how implementation outcomes relate to different modes and the corresponding individual outcomes within each mode. Thus, evaluating each mode can provide insights into the effectiveness of engagement, active implementation, or integration of an innovation. This insight extends prior work theorizing phases of the implementation process but does not explicitly specify which core implementation outcomes apply within each phase (referred to as “modes” in this review). Instead, prior work primarily focuses on identifying the temporal relationships between phases, often depicted linearly, in terms of associated processes and contextual factors (70, 85–87).

Although the inclusion of pace might suggest a linear progression of implementation efforts, its conceptual definition suggests otherwise: rather than being a strictly sequential progression, it refers to the overall speed of the implementation efforts or the rate of progression within individual modes. Furthermore, we classified pace as an attribute, meaning that it is not included among the outcomes proposed as core or focal implementation outcomes (i.e., not mapped into the modes) and is therefore not necessarily relevant in all circumstances. In contrast, pace might only be deemed of interest for inclusion in an evaluation when there is a clear purpose for doing so. In general, the role of temporality in relation to implementation strategies requires further development in implementation theories, models, and frameworks (88).

Overall, the standardization of the conceptual definitions of implementation outcomes sought in this synthesis review aims to clarify and integrate their generic conceptualizations. An underlying assumption of this approach is that the synthesized definitions and generic features of these outcomes should hold across contexts. A “concept” is generally universal and therefore applicable across contexts. Hence, heterogeneity of these outcomes may arise once they are operationalized in specific settings (as expected). Implementation practitioners can address such heterogeneity by ensuring the conceptual definitions remain consistent across contexts. In this way, they can strike a balance between internal validity—which accounts for local contextual elements, objectives, and priorities driving how outcomes are measured—and external validity—which preserves the conceptual meaning of each outcome.

Related to this point is the importance of high-quality instruments for measuring implementation outcomes, which is a necessary intermediary step (i.e., an interface) between the conceptual form of implementation outcomes and implementation strategies. Accordingly, when it comes to selecting concepts of implementation outcomes and their related instruments to assess which implementation strategies work best, we agree with recommendations from other researchers that the selection process be guided by the context and project objectives (16). In the proposed integrated framework, the term mode emphasizes the condition of the implementation process, not the stage or phase, which would imply a linear process. Bracketing implementation outcomes into distinct timeframes (such as phases or stages) is problematic since implementation processes typically unfold in parallel and iteratively. Thus, when considering which implementation outcomes might be relevant for a particular implementation project, a circumstance-driven approach (e.g., based on context and objectives) can better guide the selection of both the outcomes and a psychometrically robust instrument. However, the availability of instruments for implementation outcomes and their psychometric quality remains underdeveloped (16, 17, 89), with most existing tools concentrating on concepts such as acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility, adoption, fidelity, cost, penetration, and sustainability (16, 17, 89). Little or no development has been made for outcomes such as implementation depth, breadth, de-implementation, and implementation (the extent to which an innovation is in place).

Operationalization of the implementation outcomes into measures is crucial to enable practical and measurable observations and bridge the connection between conceptual implementation outcomes and implementation strategies. Once outcome measures have been developed, it becomes apparent how the conceptual implementation outcomes are directly related to the implementation strategies, which encompass implementation activities (16).

4.2 Practical implications

Our integrated implementation outcomes framework seeks to better reflect the complex reality of implementing innovations in health systems. It is thus in line with recent discussions that are moving away from conceptualizing the implementation process as a linear step-by-step or phased model to more iterative, integrated, or system-based models (8, 90). Our integrative re-conceptualization represents a more holistic and relational perspective on implementation outcomes, integrating focal outcomes used to assess the effectiveness or failure of implementation across three distinct modes of the implementation process on a scale of depth, breadth, and pace while also considering adaptation and de-implementation. Thus, by clarifying and identifying relevant outcomes for selection and operationalization in measurement, one of the implications of the framework we propose is its helpfulness in focusing the attention of evaluators to direct the scope of solutions or decisions that stem from evaluation outputs to improve or learn from implementation efforts. This curtails confusion and ambiguity of implementation outcomes, which are also observed to be used interchangeably in a way that blurs conceptual distinctions; it may also aid syntheses across research publications (14). However, we acknowledge that the interchangeability of some concepts, such as “sustainability” and “sustainment,” will likely persist. Sustainability is a dynamic concept (7, 47, 57, 58) that makes nuanced conceptual distinctions between the ability to predict and provide assurance of longer-term maintenance and sustainment of an implemented innovation explaining the actual continued delivery. In our review, to minimize blurred conceptual distinctions and encourage consistency in the language used, we denote the terms “sustainability” and “sustainment” (both used by authors) as representing the actual continued delivery of an innovation, which closely overlap with or might even be completely translatable with the conceptualization of “maintenance” (12, 46). In comparison, we denote and recommend using the term “capacity for sustainability” to represent the potential or likelihood of continued delivery.

Another implication of the clarified and simplified approach to conceptualizing implementation outcomes can also answer the call from practice and policy stakeholders for more pragmatic outcome measures (5). The number of outcomes is reduced and mapped accordingly under the three modes of implementation outcomes and the five associated attributes. Depicting the conceptualization of the outcomes this way makes their condition and saliency more straightforward, which addresses the recommendation to report the mode (so-called phase) during which relevant outcomes are observed or are most salient during the implementation process (14).

The proposed integrated framework of implementation outcomes in our review can be deployed as a complementary framework with other existing frameworks, e.g., determinant frameworks such as Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (7, 91), implementation theories such as Normalization Process Theory (92), established implementation outcome measures (16, 17, 89, 93), and measures of implementation progress such as the Stages of Implementation Completion (68). It can particularly inform theory-based evaluations aimed at understanding and assessing the effectiveness of implementation efforts as a proximal indication to achieving implementation success, for example, evaluation designs using program theories or logic models such as realist evaluations (94–98).

4.3 Limitations and future research

Our goal was not to achieve comprehensiveness but to capture key implementation outcomes. However, there is a possibility that we missed publications on implementation outcome frameworks and publications that conceptually further develop individual outcomes. Nonetheless, we applied a rigorous interpretive synthesis approach that combined systematic search with purposive search, including hand-searching references, citation tracking, and targeted citation searching, as a best-fit approach to balance comprehensiveness and relevance to capture and include publications conceptualizing key outcomes.

To clearly define and differentiate “health service delivery of innovations,” we applied and defined the exclusion criteria; we excluded publications focusing on the implementation of innovations in a private for-profit health context, non-health service practice context, or only involving non-health service providers. Excluding these contexts limits the scope and transferability of our findings. However, we attempted to define clear eligibility criteria to focus the review on comparable data from the literature. To ensure that we included comparable publications, we excluded publications focusing on contexts and innovation types that would influence implementation outcomes and their conceptualizations in a very diverse way, potentially blurring the boundary condition of implementation outcomes included in our consolidated conceptualization. We expected implementation outcomes and their conceptualization to be very different between private/for-profit and public/not-for-profit contexts and very different between non-health service innovations (e.g., financial/policy/governance contexts) and health service delivery innovations. Future research could expand our eligibility criteria to explore other sectors, settings, and innovation types.

Future research could further develop the integrated re-conceptualization of implementation outcomes by refining, expanding, or testing the proposed framework. Refining or expanding the modes, attributes, or individual outcomes might be helpful to advance the conceptual meanings and their application in practice, particularly for outcomes with limited conceptual developments, such as implementation pace and equitable implementation. The assessment of equitable implementation, which we proposed as being part of the breadth of implementation efforts, is significant because it is a proximal indicator to track the achievement of health equity outcomes, which is an important concern in health systems. However, there has been insufficient conceptualization and operationalization of what it means to include an equity lens in implementation outcomes and service system outcomes, although it is an area that is receiving increasing attention (15, 46, 99–101). Thus, there are opportunities to identify additional emerging concepts that are more pertinent to key issues related to the implementation of health innovations.

Future research could also test novel aspects of implementation outcomes advanced in this review, such as the attributes, including depth and breadth of implementation efforts and de-implementation (when relevant), to understand their usefulness, applicability, and saliency across the modes of implementation outcomes.

4.4 Conclusion

The suggested re-conceptualization of implementation outcomes integrates concepts developed in extensive literature from various traditions and for different implementation efforts of health innovations and evaluation purposes, reflecting the complex reality of implementation practice. It provides much-needed re-conceptualization of existing outcomes, thereby clarifying and distinguishing between focal implementation outcomes organized as modes and outcomes that can be considered as attributes of the modes that signal the thoroughness of implementation efforts. It offers a holistic yet concise and more explicit structure and guidance for improving the development and application of measures to assess the implementation effectiveness of health innovations.

Author contributions

ZB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AN: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. ZB was supported by a PhD fellowship from the National Institute for Health and Care Research ARC North Thames. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health and Care Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. The Health Foundation. Innovation is being squeezed out of the NHS (2023). Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/innovation-is-being-squeezed-out-of-the-nhs (Accessed December 22, 2023).

2. Collins B. Adoption and spread of innovation in the NHS. The King’s Fund (2018). Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/innovation-nhs (Accessed January 19, 2024).

3. Horton T, Illingworth J, Warburton W. The spread challenge. The Health Foundation (2018). Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/the-spread-challenge (Accessed January 19, 2024).

4. Lundin J, Dumont G. Medical mobile technologies – what is needed for a sustainable and scalable implementation on a global scale? Glob Health Action. (2017) 10:1344046. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1344046

5. Lewis CC, Proctor EK, Brownson RC. Measurement issues in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2017). p. 229–44. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190683214.003.0014

6. Martinez RG, Lewis CC, Weiner BJ. Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implement Sci. (2014) 9:118. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0118-8

7. Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Opra Widerquist MA, Lowery J. Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR): the CFIR outcomes addendum. Implement Sci. (2022) 17:7. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01181-5

8. Willmeroth T, Wesselborg B, Kuske S. Implementation outcomes and indicators as a new challenge in health services research: a systematic scoping review. INQUIRY. (2019) 56:0046958019861257. doi: 10.1177/0046958019861257

9. Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI): explanation and elaboration document. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013318. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013318

10. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2011) 38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

11. Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

12. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. (1999) 89:1322–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322

13. Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:64. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064

14. Lengnick-Hall R, Gerke DR, Proctor EK, Bunger AC, Phillips RJ, Martin JK, et al. Six practical recommendations for improved implementation outcomes reporting. Implement Sci. (2022) 17:16. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01183-3

15. Proctor EK, Bunger AC, Lengnick-Hall R, Gerke DR, Martin JK, Phillips RJ, et al. Ten years of implementation outcomes research: a scoping review. Implement Sci. (2023) 18:31. doi: 10.1186/s13012-023-01286-z

16. Khadjesari Z, Boufkhed S, Vitoratou S, Schatte L, Ziemann A, Daskalopoulou C, et al. Implementation outcome instruments for use in physical healthcare settings: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2020) 15:66. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01027-6

17. Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:155. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0342-x

18. Lewis CC, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Fischer SM. Advancing implementation science through measure development and evaluation: a study protocol. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:102. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0287-0

19. Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, Lysdahl KB, Booth A, Hofmann B, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the context and implementation of complex interventions (CICI) framework. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0552-5

20. Livet M, Blanchard C, Richard C. Readiness as a precursor of early implementation outcomes: an exploratory study in specialty clinics. Implement Sci Commun. (2022) 3:94. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00336-9

21. Scarbrough H, Kyratsis Y. From spreading to embedding innovation in healthcare: implications for theory and practice. Health Care Manage Rev. (2022) 47(3):236–44. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000323

22. Prusaczyk B, Swindle T, Curran G. Defining and conceptualizing outcomes for de-implementation: key distinctions from implementation outcomes. Implement Sci Commun. (2020) 1:43. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00035-3

23. Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-Ethnography: Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc (1988). doi: 10.4135/9781412985000

24. Booth A, Carroll C. Systematic searching for theory to inform systematic reviews: is it feasible? Is it desirable? Health Info Libr J. (2015) 32:220–35. doi: 10.1111/hir.12108

25. Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Gerhardus A, Wahlster P, van der Wilt GJ, et al. Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches. J Clin Epidemiol. (2018) 99:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.003

26. Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2005) 10:45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110

27. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. (2009) 26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

28. Noblit GW. Meta-Ethnography: adaptation and return. In: Urrieta L, Noblit GW, editors. Cultural Constructions of Identity: Meta-Ethnography and Theory. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press (2018). p. 34–50. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190676087.003.0002

29. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. (2004) 82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

30. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

31. Oxford English Dictionary. Concept, n. meanings, etymology and more (2015). Available at: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/concept_n (Accessed May 06, 2025).

33. Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17:88. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

34. Moncher FJ, Prinz RJ. Treatment fidelity in outcome studies. Clin Psychol Rev. (1991) 11:247–66. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(91)90103-2

35. Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. (2007) 2:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40

36. Keith RE, Hopp FP, Subramanian U, Wiitala W, Lowery JC. Fidelity of implementation: development and testing of a measure. Implement Sci. (2010) 5:99. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-99

37. Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. (2012) 50:462–80. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x

38. Katz J, Wandersman A, Goodman RM, Griffin S, Wilson DK, Schillaci M. Updating the FORECAST formative evaluation approach and some implications for ameliorating theory failure, implementation failure, and evaluation failure. Eval Program Plann. (2013) 39:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2013.03.001

39. Decker P, Durand R, Mayfield CO, McCormack C, Skinner D, Perdue G. Predicting implementation failure in organization change. J Org Cult Commun Conflict. (2012) 16:29–49.

40. Goodman RM, Steckler A. A model for the institutionalization of health promotion programs. Fam Community Health. (1989) 11:63–78.

41. Goodman RM, Steckler A. A framework for assessing program institutionalization. Knowl Soc. (1989) 2:57–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02737075

42. Slaghuis SS, Strating MMH, Bal RA, Nieboer AP. A framework and a measurement instrument for sustainability of work practices in long-term care. BMC Health Serv Res. (2011) 11:314. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-314

43. Yin RK. Life histories of innovations: how new practices become routinized. Public Adm Rev. (1981) 41:21–8. doi: 10.2307/975720

44. May C, Harrison R, Finch T, MacFarlane A, Mair F, Wallace P, et al. Understanding the normalization of telemedicine services through qualitative evaluation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2003) 10:596–604. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1145

45. May CR, Mair F, Finch T, MacFarlane A, Dowrick C, Treweek S, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: normalization process theory. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:29. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-29

46. Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:134. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00134

47. Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res. (1998) 13:87–108. doi: 10.1093/her/13.1.87

48. Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis J-L. Making public health programs last: conceptualizing sustainability. Eval Program Plann. (2004) 27:121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.01.001

49. Buchanan D, Fitzgerald L, Ketley D, Gollop R, Jones JL, Lamont SS, et al. No going back: a review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. Int J Manag Rev. (2005) 7:189–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00111.x

50. Bowman CC, Sobo EJ, Asch SM, Gifford AL. HIV/Hepatitis quality enhancement research initiative. Measuring persistence of implementation: QUERI series. Implement Sci. (2008) 3:21. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-21

51. Maher L, Gustafson DH, Evans A. NHS sustainability model. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2010). Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/publication/sustainability-model-and-guide/ (Accessed October 8, 2021).

52. Molfenter T, James FH, Bhattacharya A. The development and use if a model to predict sustainability of change in health care settings. Int J Inf Syst Change Manag. (2011) 5:22–35. doi: 10.1504/IJISCM.2011.039068

53. Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:2059–67. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193

54. Doyle C, Howe C, Woodcock T, Myron R, Phekoo K, McNicholas C, et al. Making change last: applying the NHS institute for innovation and improvement sustainability model to healthcare improvement. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:127. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-127

55. Fleiszer AR, Semenic SE, Ritchie JA, Richer M-C, Denis J-L. The sustainability of healthcare innovations: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. (2015) 71:1484–98. doi: 10.1111/jan.12633

56. Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, Lynch J, Hughes G, A’Court C, et al. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e367. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8775