- 1Center for Clinical Management Research, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 2Division of General Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Background: Academic Detailing (AD) is an educational outreach strategy that has shown positive effects on clinical practice, but its implementation varies widely across programs, necessitating consistent definitions of its essential components. The lack of standardized guidance for tailoring AD and other multi-component implementation strategies presents challenges in program development and effectiveness evaluation. To address this, we applied FRAME-IS (Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based Implementation Strategies) to specify AD's core components and demonstrate a repeatable program development process. By showcasing a multi-project, multi-site AD program, we aim to provide guidance for others in developing and tailoring AD programs, ultimately enabling more rigorous evaluations of AD's effectiveness.

Methods: Literature and training materials were reviewed to develop a list of common AD components, then organized according to a FRAME-IS template. Coders applied directed content analysis to materials from the MIDAS AD program, a multi-site implementation center using AD in four projects across the Veterans Health Administration. Tailoring and development of the AD program was coded according to FRAME-IS modules and ERIC strategy taxonomy.

Results: 18 common AD components were identified. These components were retained but six were tailored and an additional seven were added across the MIDAS projects. The rationale for tailoring and additions was mostly to increase appropriateness, acceptability, adoption, and reach of AD. To assist in future tailoring of AD programs, we developed a list of generalizable guiding questions and an AD program documentation and tailoring template.

Conclusions: AD is a robust strategy, but empirical study of the core and modifiable components is constrained by variable definitions of the components. This is the first attempt at developing documentation and tailoring guidelines for AD programs using the nomenclature of implementation science. We further suggest which components may be core and which may be modifiable. Our effort to specify AD components using the FRAME-IS method provides an example for other AD programs, contributing to the future use and study of AD as an implementation strategy and paving the way for more rigorous analysis of which modifications affect outcomes.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05065502.

Introduction

For complex behavioral interventions, tailoring implementation strategies to address context is the rule, not an exception (1, 2). But tools to aid effective, conceptually sound, and efficient modification are only recently being developed (3, 4). Before tailoring or modification begins, consistent definitions of strategy components are essential. One strategy with a history of modifying components is Academic Detailing (AD). In use since the 1980s, AD is a form of educational outreach in which trained staff (“detailers”) have one-on-one conversations with healthcare providers to improve those providers' adoption of specific evidence-based practices (EBPs) (5, 6). This strategy has been widely and successfully used within the pharmaceutical industry (5–10). Yet experts in AD acknowledge a wide range of conceptualizations regarding which components are necessary for a program to be considered “Academic Detailing.” Individual AD programs vary in design, approach, and structure, including basic choices such as whether detailers need professional credentialing vs. project-specific training and whether educational interactions must be one-on-one vs. a group format (5–8, 11, 12).

Not only do the many structures of AD programs make program development challenging, but there is also no guidance about which design modifications to choose to best meet the needs of a specific AD program. This problem is common in multi-component implementation strategies, which are rarely fully described in the literature or are presented as unbreakable multi-component packages (3, 13), creating a challenge for both the study of their effect and tailoring efforts. Further, it is often unclear when, how, and why to tailor strategies (14). This concern has led to attempts to identify, track, and more clearly document modifications made to implementation strategies (4, 15). The Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based Implementation Strategies (FRAME-IS) provides a modular template with detailed guidance for specifying components and adaptations (4, 16–18). It is highly modular which allows thorough specification of both core and modifiable components of a strategy that has a diversity of conceptualizations. Application of FRAME-IS to AD allows us to create an AD framework for rational modification of AD programs.

This paper aims to describe possible modifications in AD when using as an implementation strategy and to provide guidance for developing and tailoring an AD program. Specifically, we aim to: (1) Specify AD core components with FRAME-IS nomenclature; (2) Demonstrate a repeatable program development process using FRAME-IS to describe the “how” and “why” of tailoring for developing one AD program used in four implementation projects; and (3) Provide guidance for developing an AD program. The context was our development of a multi-project, multi-site AD program within the United States Veterans Health Administration (VHA), and we present examples of modifications we considered and ultimately chose. This work is novel both in its use of FRAME-IS as a generalizable template for AD program development and tailoring, and in defining the core vs. modifiable components of AD that provides a guide for others to follow. While it is beyond our current scope to assess the effect of program modifications on AD outcomes, we lay the groundwork to enable rigorous evaluations of AD effectiveness.

Materials and methods

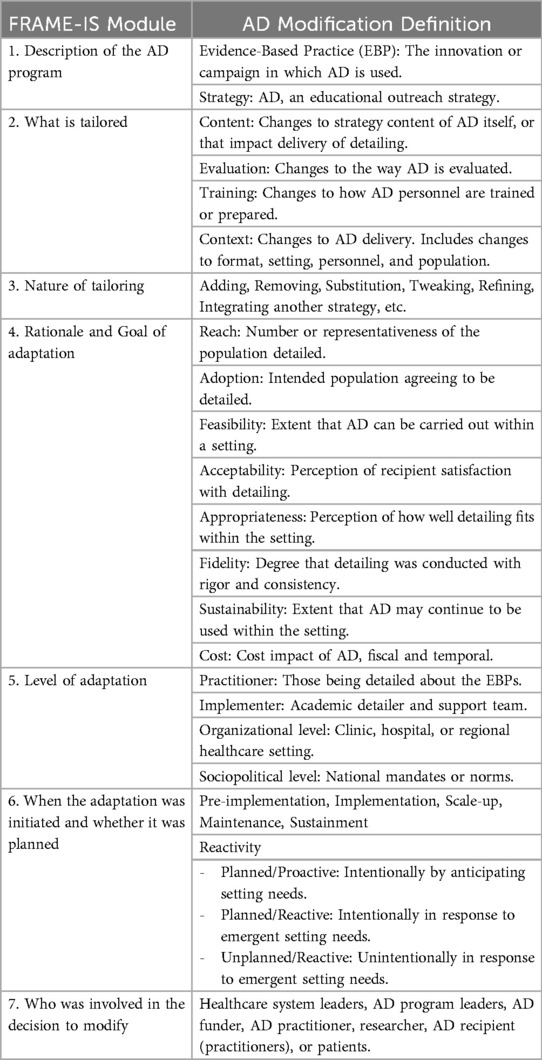

Creation of AD tailoring documentation system

FRAME-IS provides a template for systematically tracking modifications to an implementation strategy according to discrete modules (4). The modules report the: (1) “Description” of the EBP, implementation strategy, and brief modification description. (2) “What” (type) of strategy modification made according to four categories: content of the strategy itself or its delivery, evaluation for the way the strategy is evaluated, training in terms of the manner of implementer training, and context of how the strategy is delivered, specifically changes to format of delivery, setting of delivery, personnel delivering the strategy, or population targeted for delivery. (3) “Nature” of modification, which refers to the extent and intensity of the modification with pre-specified codes such as tailoring; adding elements; removing elements; lengthening, substituting, spreading, or integrating another strategy into the implementation strategy in primary use; loosening structure; and others. (4) “Rationale” behind the modification. This defines both the goal and level of modification. (4a) Goal codes are sorted by implementation outcomes such as intending to improve reach, effectiveness, adoption, acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, cost, sustainability, or equity. (4b) Level codes dictate identifying the socioecological levels influencing the decision to modify for sociopolitical, organizational, implementer, provider, or patient reasons. (5) “When” (timing) of tailoring the strategy components (pre-implementation, implementation, scale-up, or maintenance) and whether the modification was planned/proactive, planned/reactive, or unplanned/reactive. (6) “Who” defined or is involved in the decision to modify the strategy: political leaders, program leaders, funder, implementer, researcher, providers, community members, or patients.

Consistent with other implementation scientists (14, 15, 19), we use “tailoring” to reference altering strategies to fit context and “modification” as a generic term for change. There is debate but little consensus regarding the scope and definitions of the terms “adaptation,” “tailoring,” and “modification.” Notably, some researchers may classify AD tailoring as an “adaptive implementation strategy” (2, 20).

Identifying common components of AD

To understand and guide modifications, we agreed on a set of components common to AD. Due to the vast range of AD conceptualizations in the literature (5–8, 10–12, 21, 22), the decision was made to identify common components from publicly available implementation and training materials (23–25). Priority was given to AD components named by the National Resource Center for Academic Detailing (NaRCAD) and the VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management's Academic Detailing Services (ADS), as both are national leaders in AD development and practice. One project investigator (AMD) cross-walked these training materials to identify 18 components that tend to exist in AD programs both within and beyond VHA. Components were grouped by the FRAME-IS module 2 (“What”) categories (content, evaluation, training, and context) to create an initial matrix of the AD common components. The 18 components were further typed according to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy of implementation strategies (26) using a coding specification tool (27). ERIC is a sorted list of implementation strategies derived from expert consensus and concept mapping. The phrasing used in ERIC has become common nomenclature in implementation science. ERIC terms are widely used to ensure implementation tools are generalizable across contexts and innovations, and to assist future meta-analyses of implementation strategy effectiveness. Coding strategy components to ERIC is not prescribed by FRAME-IS developers but was conducted here to standardize strategy terms. By standardizing AD component definitions to a general taxonomy, this will enable future AD analyses and ensure that AD modifications are consistently defined.

Maintaining implementation through dynamic adaptations (MIDAS) AD program development

An overarching AD program was developed to support AD projects for three hybrid III cluster randomized implementation trials (28) and a non-randomized intervention project as part of the Maintaining Implementation through Dynamic Adaptations (MIDAS) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) center. Within each of these projects, AD was used as a strategy to support a specific quality improvement program (29) within participating healthcare sites across VHA. The goals for the four projects were: to reduce inappropriate polypharmacy among older adults, improve safe use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs), promote Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) as a first-line treatment over medications, and increase referrals to a telehealth suicide prevention program. The MIDAS AD program deployed in 23 sites across VHA from 2021–2024 to support the four projects.

The MIDAS team developed an AD program to support these projects. The AD program needed to meet four key criteria and work within immutable constraints. First, the program must be able to support the broad range of project topics. Second, we were not able to support separate detailers with content expertise for each of the four project topics. Third, national policies prevented us from employing VHA providers or funding VHA ADS to staff the projects (6, 9, 10, 30). Fourth, rigorous evaluation required consistency across projects, clear definition of AD strategies used, clear descriptions of adaptations, and clearly defined outcomes. MIDAS AD program development was informed by a comprehensive review of existing AD program materials, particularly from the VHA ADS (23), NaRCAD (24), and existing research publications (5–7, 11, 12, 21) and from our experience with quality improvement and implementation science interventions. Based on these sources, we created a master protocol specifying project content, evaluation design, and detailer training tailored to MIDAS's needs (Supplementary Material A). Among these materials are specifications of evaluation tools including a fidelity assessment using self-ratings and peer review (Supplementary Material B), a detailer script (Supplementary Material C), and a participant satisfaction survey (Supplementary Material D).

Classification of MIDAS AD components

To classify MIDAS modifications, we followed five steps for rigorous document analysis (31–34). First, two trained detailers (GH, MF) independently defined the MIDAS AD program components by conducting a MIDAS document review using modified directed content analysis (31, 32). We reviewed materials from across the development and implementation of the four projects including protocol drafts, training materials, fidelity assessment entries (such as post-detailing session notes and ratings), and peer reviewer notes. Second, we classified components according to the FRAME-IS modules. One investigator (AMD) applied predetermined FRAME-IS module codes (4) to component descriptions for MIDAS AD, then re-coded components based on ERIC labels and definitions. Labels were applied based on identifying the best fit between detailed MIDAS AD component descriptions and ERIC labels provided by the developers (26, 27), with an emphasis on the function of the component. As needed, the investigator consulted with an ERIC developer (LD) for accuracy. Third, two collaborators (LE, MS) iteratively reviewed the MIDAS AD component descriptions, categorizations, and codes as a form of validity check via peer debriefing (33). Fourth, for reliability checks (34), content and codes were reviewed and revised in five reflexivity discussions held over the course of three months with the investigative team (GH, MF, AMD, LE, MS). Finally, the final reporting structure was reviewed and approved by two project leaders (JBS, LD) as representative of the MIDAS AD program.

Results

Academic detailing documentation system

The AD documentation system used FRAME-IS codes for each module (Table 1). These definitions were extracted from the method developers (4) and worded to be AD-specific. The AD tailoring definitions are the codes within each module we suggest for use when documenting AD program customization to context, as in MIDAS (below). Supplementary Material E provides a blank AD FRAME-IS template for other programs to describe their AD components and modifications.

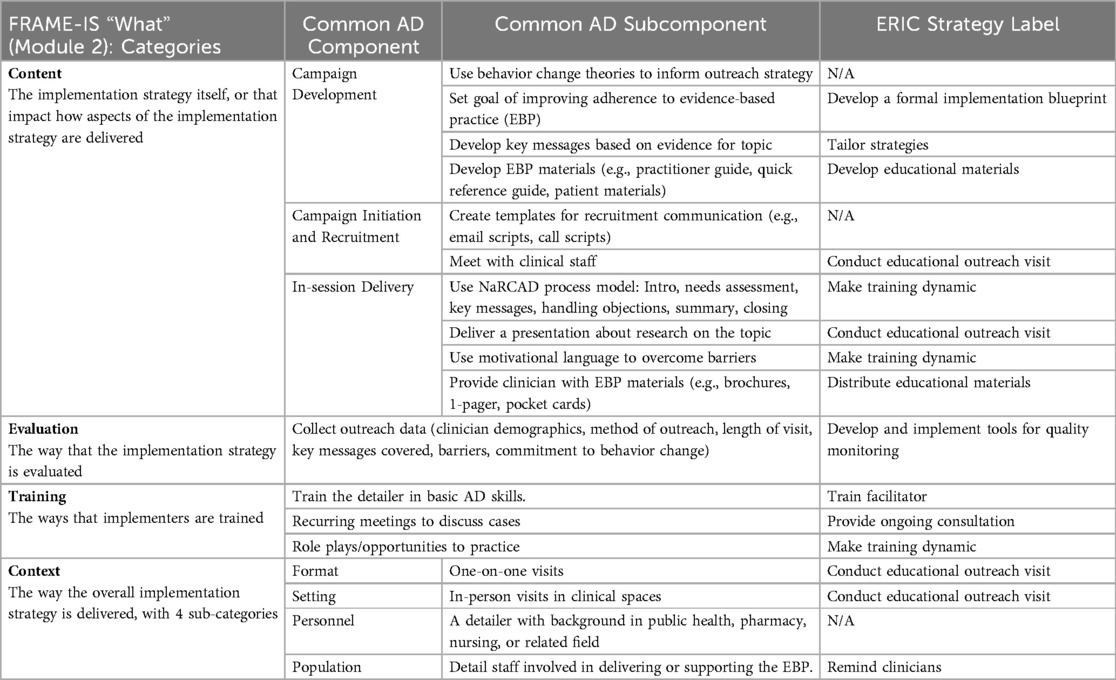

Common components of AD

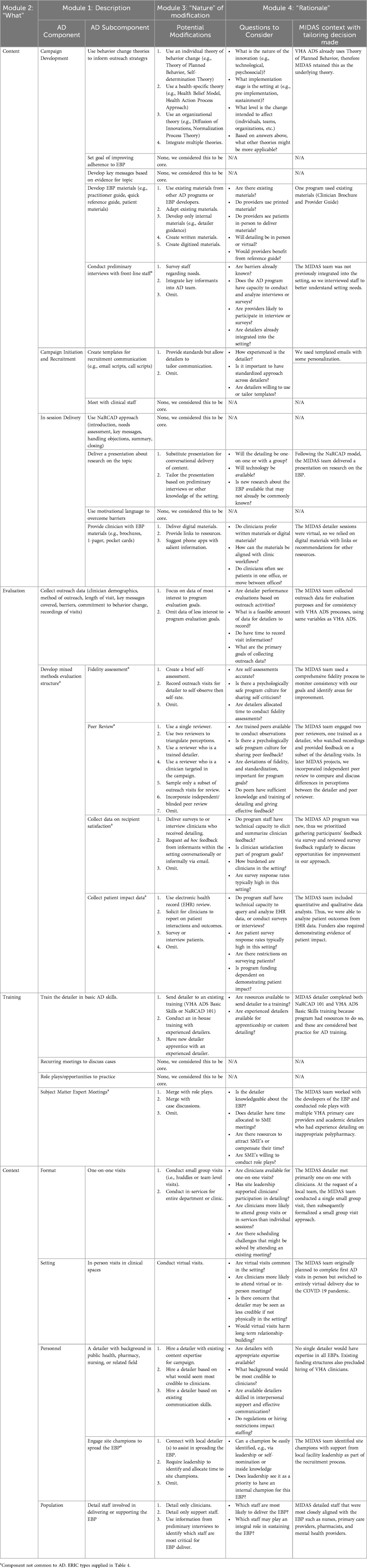

We identified common core components and subcomponents of AD programs structured by the FRAME-IS “what” module (Table 2). Content comprises three core components: campaign development, campaign initiation and recruitment, and in-session delivery. Each component has subcomponents; for example, developing key messages, meeting with clinical staff, and delivering a presentation about the topic. The only common component for AD evaluation is collecting outreach process data to document which providers were educated, the duration and timing of those educational outreach sessions, and the content of the session such as barriers brought up by the provider (for example, a necessary medication is not in their order set) and whether the detailer secured the provider's verbal commitment to change their prescribing behavior to be more consistent with the innovation. The three common components for training dictate having detailers attend a basic skills workshop, meeting with detailer colleagues or consultants for consultation, and practicing via role play. Finally, four common components of context show that AD outreach visits are usually delivered one-on-one, in-person, to front-line staff, and by someone with a background in a health-related field.

Table 2. Academic detailing (AD) common components per FRAME-IS “what” code and ERIC naming convention.

Mapping each component to ERIC reveals that four AD common components pertain to conducting educational outreach visits, three to making training dynamic, and one each to seven other strategies: develop a formal implementation blueprint, tailor strategies, distribute educational materials, develop and implement tools for quality monitoring, train facilitator, provide ongoing consultation, and remind clinicians (Table 2). Taken together, Table 2 shows that, as commonly used, AD programs are a multi-faceted implementation strategy that bundle together a range of educational and interactive components.

MIDAS AD program tailoring decisions

Key to beginning the program was identifying potential modifications of AD components, questions to consider for our program, and the MIDAS-specific context from which all decisions were made (Table 3). We strove to apply a consistent MIDAS AD strategy to all four EBP interventions. While based on our experiences developing the AD program, we structured this paper around providing guiding questions and points of consideration for future AD program developers when making tailoring decisions.

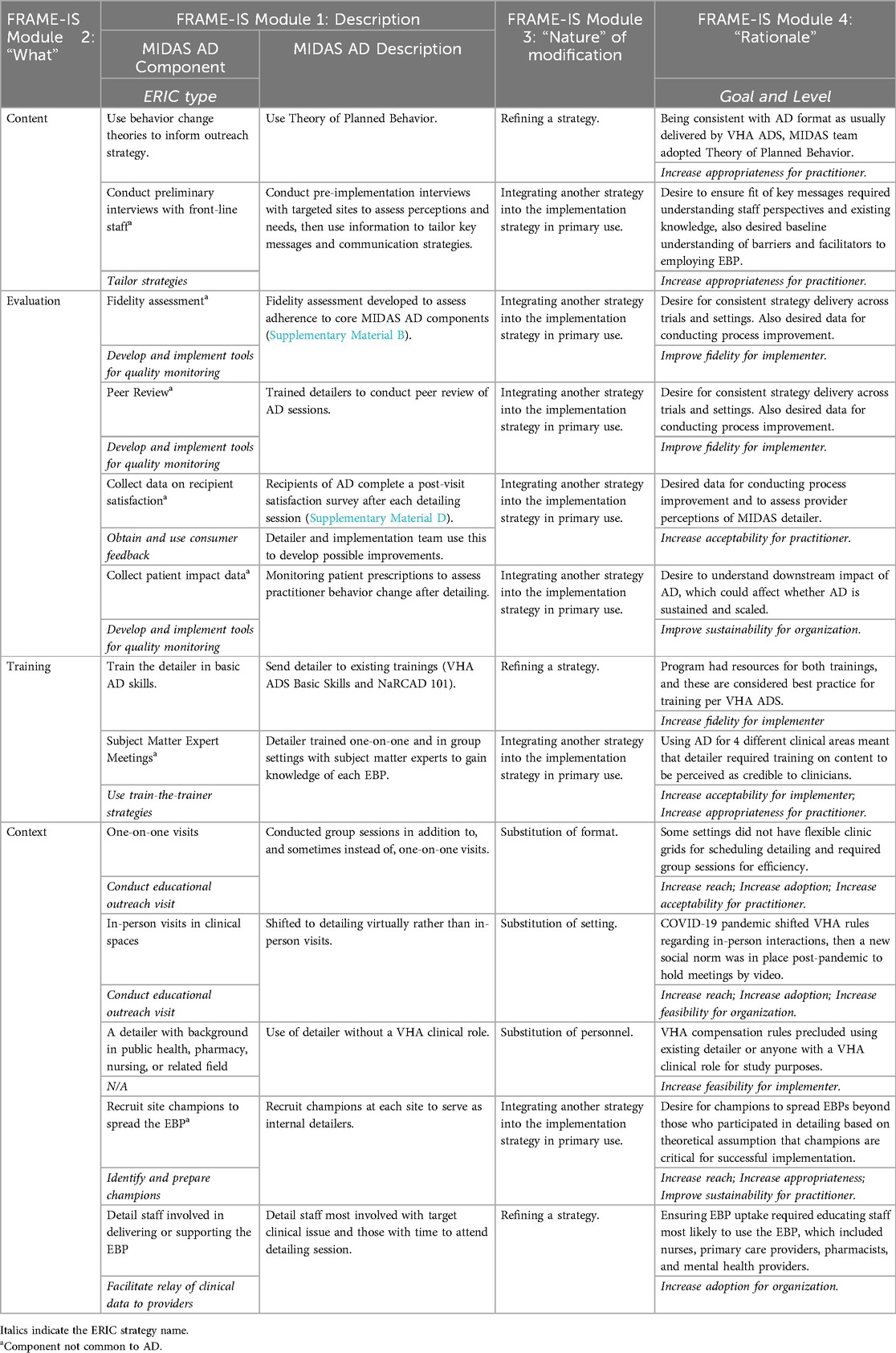

MIDAS AD tailored components classification

The list of tailored and additional MIDAS AD components is presented in Table 4 along with the reason for tailoring or adding. Out of eighteen common AD components, MIDAS AD program developers retained 12 components with no modification; these are therefore not included in Table 4 (but can be seen in Table 2). MIDAS tailored (i.e., substituted or refined) six of the common components. The MIDAS AD program developers then added an additional seven components by integrating strategies not usually included in common AD. Added components not otherwise found in common AD are denoted with an obelisk symbol. No components of common AD were removed from MIDAS AD.

In Table 4, the FRAME-IS codes show the category of “what” was modified (Module 2), provide a “description” of the modification (Module 1) with ERIC labels, and the “nature” (Module 3) and “rationale” (Module 4) of each modification. Two modules are not included in Table 4: Modules 6 and 7. The “when” (Module 5) was always during pre-implementation and planning was always planned/proactive, except for the use of group visits when the modification was during implementation and the planning was reactive. The “who” (Module 6) of decision-makers was always the MIDAS team.

Per Module 4 (“rationale”), reasons for modification primarily stemmed from needs at the provider and organizational levels, and in some cases the implementer level. The goals of each modification varied and aimed primarily to improve appropriateness, acceptability, adoption, and reach. Per ERIC type (shown in italics in the Module 1 column), the MIDAS AD program tailored components related primarily to the method of conducting educational outreach visits and developing and implementing tools for quality monitoring of AD.

Remaining results are organized according to the “nature” of modification (Module 3), first by those tailored (Module 1, no symbol in Table 4) and then by the integration of other strategies into AD (Module 1, denoted with obelisk symbol in Table 4). Underlined words indicate the categories of “what” (Module 2) was changed with italics to draw attention to specific codes.

Tailored MIDAS AD components

Tailored components refer to those common in AD but modified for MIDAS (Table 4). One common component of AD content was tailored by refining the strategy of using behavior change theories to inform outreach strategy. Among the available options, MIDAS used the Theory of Planned Behavior because it is consistently named by VHA ADS and NaRCAD as the key theory underlying provider behavior change after detailing. This uses detailer influence to affect provider attitudes towards the EBP, share data of what is expected in practice to affect subjective norms, listen to provider opinions on the EBP to foster a perception of control, and secure a provider's verbal intention to change practice to be EBP-consistent (35). One tailored component of AD training was similarly refining the strategy to educate the MIDAS detailer via VHA ADS's Basic Skills training and NaRCAD's AD 101 training. There are few options for AD training, and these are consistently used by VHA ADS detailers to enhance fidelity of implementing AD.

All common components of AD context were tailored to MIDAS. The substitution of format (offering both group and one-on-one sessions) and substitution of setting (only virtual sessions were practical) were made in response to the needs and restrictions of the setting. The format varied slightly across projects in reaction to a site's staff requests. One unplanned substitution of format occurred in the suicide prevention project when providers insisted it was infeasible to conduct one-on-one visits. This modification compromised the fidelity of AD, which is assumed to work best one-on-one. Nevertheless, in this project AD was delivered to a group of providers under the assumption that it could increase reach, adoption, and acceptability among staff with limited time. The substitution of setting deviated from the original MIDAS plan (28), shifting from in-person sessions to virtual. This reactive change was made during the pre-implementation stage in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and retained across all projects since video meetings had become a VHA norm. A substitution of personnel—employing someone who was not a pharmacist or nurse as detailer—was made for several reasons. Commonly, VHA ADS uses pharmacists whereas other AD programs use detailers with clinical service or public health backgrounds. Regulatory restrictions prohibited part-time hiring of both existing VHA detailers or providers, and financial limitations precluded hiring one directly onto the MIDAS staff. We believed with appropriate EBP upskilling, as described in the training section below, a detailer without clinical or public health experience could be an excellent detailer. The population modification simply refined the definition of the targeted audience (“front-line staff”). In practice VHA detailers often target primary care providers (5). In MIDAS, the decision was made to detail staff most involved with the target clinical issue. This varied by EBP and included nurses, pharmacists, primary care providers, and mental health professionals across clinical services. Detailing clinical staff with a salient role in delivering each EBP aimed to increase adoption under the assumption that potential EBP adopters would be those who would benefit most from detailing.

Integrating other strategies into MIDAS AD

Integrated components are those not found in common AD but added for MIDAS. When developing the MIDAS AD program, strategies not usually found in AD were integrated across all four “what” categories (labeled with obelisk marker in Table 4).

The modification to content was the addition of pre-implementation interviews with front-line staff at participating sites prior to each project launch. This change was made for two reasons: a desire to understand whether each campaign's key messages fit well with staff perspectives on the topic and to understand the baseline implementation barriers and facilitators. The overall goal of tailoring this aspect of campaign development was to increase perceived appropriateness of AD among the strategy recipients (VHA providers). Information gleaned from interviewees was used to optimize delivery of targeted key messages to ensure they were responsive to reported barriers and would resonate with recipients. For example, in the DOAC trial, the second of four, pre-implementation interviews highlighted a site-level variation in who was responsible (pharmacists or primary care providers) and how DOACs were managed (centralized vs. decentralized vs. a combination). With this information, we developed targeted messaging based on the identified management structure and responsible party.

MIDAS AD further integrated evaluation strategies not commonly found in AD programs to improve process fidelity and acceptability and to enable later evaluation of project success. We aimed to assess both the strategy itself and the quality of the detailer's delivery of the strategy. With recipient approval, the MIDAS detailer recorded outreach sessions with providers to allow for detailer reflection, evaluation, and quality assurance. The detailer completed a self-report fidelity assessment (36) after each session to assess adherence to AD components. Peer review of sessions was another strategy added; periodically, a subset of AD session recordings underwent peer review for fidelity ratings via an external observer. The peer reviewer shared notes with the detailer which were deliberated in weekly collaboration meetings. These meetings empowered the AD team to troubleshoot challenges and refine the detailing as needed. One project further tailored the peer review process to include blinded ratings by the peers, which were then compared to the detailer's self-assessment prior to collaboration meetings. This modification was made to strengthen the peer review process and better discern areas of protocol fidelity and deviation.

Collecting recipient satisfaction surveys after each session was another evaluation addition that served as a form of process feedback. Survey data was reflected upon as a group and used to improve detailing. Further, to assess impact of AD on service provision, MIDAS collected patient outcomes data and monitored referrals and patient prescriptions as a proxy of provider behavior change post-detailing. Integrating an outcome monitoring strategy served to enhance sustainability by creating a norm of data tracking to assess use of best practices.

A single additional strategy was integrated into detailer training: subject matter expert meetings. Because MIDAS applied AD to four different clinical areas, there was a need to train the detailer on content for each campaign to ensure the detailer was perceived by providers as a credible source of information. Notably, upskilling on campaign topics is common in VHA ADS detailing (23) but is not described broadly in the literature as a common AD component. The MIDAS detailer met with content experts both one-on-one and as a group. These meetings served to increase the detailer's topical expertise across disparate EBPs to accurately disseminate the EBP information. Increasing detailer's EBP-specific knowledge aimed to improve perceived appropriateness and acceptability of the detailer educating providers. These supplementary subject matter expert trainings were delivered across projects, including those where the MIDAS detailer had clinical experience (CBT and suicide prevention) under the assumption that expertise is enhanced through repeated exposure and feedback. Initial meetings were focused purely on acquiring the knowledge and learning communication norms about the intervention; later meetings included a role-playing component for the detailer. This was also an opportunity for the detailer to received targeted feedback from the subject matter expert.

One context addition was to recruit and train site champions. Providers were identified from each site to not only receive education, but also to encourage them to advocate for EBP use among colleagues. The intention behind this modification was to enhance EBP uptake by having champions promote use of the EBP internally, essentially ensuring spread beyond the reach of one-on-one detailing recipients. This proactive change aimed to increase reach, appropriateness, and sustainability by preparing an in-house advocate.

Discussion

Developing effective implementation strategy modifications requires a complex synthesis of understanding local needs and which aspects of a strategy are core, which are useful, and which can be effectively modified. In this study, we defined the common components of AD and nested them within a conceptual framework from implementation science. We then outlined how and why we modified common AD components to develop and tailor the AD strategy to fit program-specific needs and context. We also illustrated a repeatable modification process using the FRAME-IS template. We hope this can be used as a model for how future AD programs can use existing variation as a strength, while still learning from prior work.

There are four important observations from the process of tailoring AD for MIDAS. First, few modifications were necessary, particularly in the content domain. AD is already a robust strategy with resources available from NaRCAD, VHA ADS, and more (5–7, 11, 12, 21, 23, 24). Second, the wide variation in AD programs may be because context choices, such as format, delivery, and detailer background, truly are modifiable (able to be changed without compromising strategy success) and not “core” (essential and indispensable) to AD. In fact, in our project, a feature considered core to AD by many programs (5, 7, 11, 24)—one-on-one outreach—was infeasible in some settings, but shifting to group educational sessions for one project effectively ensured that the key campaign messages were delivered to providers. Third, project-specific content education was practical, instead of hiring detailers with expertise in the content of each study (9, 10, 23). Our primary detailer had a background in counseling and was trained in motivational interviewing. Training modifications focusing on the specifics of the EBP, the AD key messages, and providers' likely individual barriers and facilitators to adoption made the MIDAS detailer knowledgeable across all four clinical topics. Finally, due to our program's research interests, we modified traditional programs by adding evaluation components that may be infeasible or unnecessary in some AD programs (12). Our tools could be helpful to other AD programs to assess detailer skill, detailer behavior, detailer-provider interaction, provider behavior, and patient outcomes. We felt the peer review process, in particular, enhanced AD rigor and fidelity to ensure consistent delivery across projects compared to self-assessment (36) or no evaluation at all. Collecting data on recipient satisfaction and provider prescribing behavior means that the effectiveness of AD can be empirically validated. Adding these components can build the AD evidence-base regarding where and how AD is effective.

Implications for AD program development

Strategy tailoring is necessary to fit implementation processes to specific needs (3, 15, 37). Yet, changing an established strategy raises key questions: how much can it change? At what point has it changed so much that the critical elements are gone? Given the wide range of conceptualizations regarding AD key components and activities (5–8, 11, 12), our work to describe common AD components and their tailoring is an important step. One previous review that attempted to define AD characteristics found a 36.5%–100% variation between AD programs, particularly regarding communication components (12). A subsequent Delphi study (11) specified six key features of AD, among them an emphasis that AD focus on changing provider behavior. Despite these attempts at consensus, disagreement remains. For example, some argue AD is most effective in one-on-one, face-to-face sessions (6, 7, 9), while others report effective virtual delivery (10), or that—in contrast to the Delphi study findings—AD is designed for making workflow process improvements (21). This variation in what defines AD calls for future studies to document and make available programmatic components, resources used for development, and modifications from those resources. Our work starts to fill this aim.

While we propose that choices made for MIDAS may represent areas that are core (i.e., content) and modifiable (i.e., evaluation, context), we cannot conclusively say this is true across contexts. However, based on our literature reviews and experience across four projects, we can provide a template and guidance for tailoring AD programs. When we developed and delivered AD, there were many potential decision points for how to tailor the program. We describe these guiding questions to provide options for tailoring AD depending on context. Table 3 is a resource for AD developers to consider as they embark on their own implementation projects.

While several resources are freely available to learn about AD (10–12, 23, 24), we can only find one guidebook for creating and implementing a new AD program (25). To build the public library on AD development and study, MIDAS AD protocols and evaluation tools are available as supplementary materials. We strongly suggest that AD programs use the FRAME-IS template in Supplementary Material E to track their modifications towards building our understanding of which AD components are core and which are modifiable, in effort towards the broader study of implementation strategy bundles.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this report are the use of extensive document review and coding schemes supported by a team of collaborators with strong implementation science experience, the application of a systematic method for reporting modifications, and the demonstration of a generalizable suite of modifications that applied to four projects with different EBPs. A limitation for non-VHA settings is that there may be more variations on common components than we identified, especially given the large number of small AD programs nationwide. Notably, in non-VHA settings the payment and reimbursement systems provide different prescribing incentives and adherence metrics. Another limitation is our inability to assess which modifications were effective for their programs.

Conclusion

The present work is of greatest relevance to those seeking to develop and test new VHA AD programs and for implementation researchers interested in using FRAME-IS to identify critical and modifiable components of AD and other implementation strategies.

AD is a multi-component bundle of strategies; indeed, multi-faceted and tailored strategies are necessary to affect health providers' behavior (38). Implementation strategies are often bundled (3), which presents a challenge for studying their effects on outcomes (15). Efforts have been made to specify discrete strategies within bundles (13), track their effects on outcomes (3, 15), and document strategy modification (4). Still, few examples of combining these efforts to determine which modifications affect outcomes exist (39). The prominent barrier is that implementation scientists have yet to consistently take the prerequisite first step of unbundling strategies. The present work displays an effort to unbundle and define both the usual practice of AD, name the modifications present in a series of projects, and provide guidance for others seeking to tailor an AD program for their needs. Future analysis of the MIDAS projects will indicate the successes and failures of MIDAS AD and highlight AD components critical for implementation outcomes.

Our work to describe common AD represents an important step in studying AD given the wide range of conceptualizations regarding AD key components and activities (5–8, 11, 12). The FRAME-IS method used here may provide a template for other VHA AD programs to specify which components are core and modifiable across applications. We hope this contributes to future use and study of AD as an implementation strategy.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GH: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MF: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LE: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Resources, Writing – review & editing. LD: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the US Department of Veteran’s Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) for Maintaining Implementation through Dynamic Adaptations (MIDAS) (QUE 20-025).

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is extended to the VA Academic Detailing Service for their invaluable partnership and the MIDAS QUERI team for their support and feedback.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2025.1521504/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AD, academic detailing; ADS, academic detailing services; CBT-I, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; EBP, evidence-based practice; ERIC, expert recommendations for implementing change; FRAME-IS, framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based implementation strategies; NaRCAD, national resource center for academic detailing; MIDAS, maintaining implementation through dynamic adaptations; QUERI, quality enhancement research initiative; VHA, veterans health administration.

References

1. Mody A, Filiatreau LM, Goss CW, Powell BJ, Geng EH. Instrumental variables for implementation science: exploring context-dependent causal pathways between implementation strategies and evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci Commun. (2023) 4:157. doi: 10.1186/s43058-023-00536-x

2. Geng EH, Mody A, Powell BJ. On-the-go adaptation of implementation approaches and strategies in health: emerging perspectives and research opportunities. Annu Rev Public Health. (2023) 44:21–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-051920-124515

3. Rudd BN, Davis M, Beidas RS. Integrating implementation science in clinical research to maximize public health impact: a call for the reporting and alignment of implementation strategy use with implementation outcomes in clinical research. Implement Sci. (2020) 15:103. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01060-5

4. Miller CJ, Barnett ML, Baumann AA, Gutner CA, Wiltsey-Stirman S. The FRAME-IS: a framework for documenting modifications to implementation strategies in healthcare. Implement Sci. (2021) 16:36. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01105-3

5. Rowett D. Evidence for and implementation of academic detailing. In: Weekes LM, editor. Improv Use Med Med Tests Prim Care, Singapore: Springer (2020). p. 83–105. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-2333-5_4.

6. Midboe AM, Wu J, Erhardt T, Carmichael JM, Bounthavong M, Christopher MLD, et al. Academic detailing to improve opioid safety: implementation lessons from a qualitative evaluation. Pain Med. (2018) 19:S46–53. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny085

7. Kennedy AG, Regier L, Fischer MA. Educating community clinicians using principles of academic detailing in an evolving landscape. Am J Health Syst Pharm. (2021) 78:80–6. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa351

8. Avorn J, Soumerai SB. Improving drug-therapy decisions through educational outreach. N Engl J Med. (1983) 308:1457–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306163082406

9. Bounthavong M, Suh K, Christopher MLD, Veenstra DL, Basu A, Devine EB. Providers’ perceptions on barriers and facilitators to prescribing naloxone for patients at risk for opioid overdose after implementation of a national academic detailing program: a qualitative assessment. Res Soc Adm Pharm. (2020) 16:1033–40. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.10.015

10. Himstreet JE, Shayegani R, Spoutz P, Hoffman JD, Midboe AM, Hillman A, et al. Implementation of a pharmacy-led virtual academic detailing program at the US veterans health administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. (2022) 79:909–17. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxac024

11. Yeh JS, Van Hoof TJ, Fischer MA. Key features of academic detailing: development of an expert consensus using the Delphi method. Am Health Drug Benefits. (2016) 9(1):42.27066195

12. Van Hoof TJ, Harrison LG, Miller NE, Pappas MS, Fischer MA. Characteristics of academic detailing: results of a literature review. Am Health Drug Benefits. (2015) 8:414–22.26702333

13. Leeman J, Birken SA, Powell BJ, Rohweder C, Shea CM. Beyond “implementation strategies”: classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:125. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0657-x

14. Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. (2017) 44:177–94. doi: 10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6

15. Walsh-Bailey C, Palazzo LG, Jones SM, Mettert KD, Powell BJ, Stirman SW, et al. A pilot study comparing tools for tracking implementation strategies and treatment adaptations. Implement Res Pract. (2021) 2:26334895211016028. doi: 10.1177/26334895211016028

16. Martinez K, Lane E, Hernandez V, Lugo E, Muñoz FA, Sahms T, et al. Optimizing ATTAIN implementation in a federally qualified health center guided by the FRAME-IS. Am Psychol. (2023) 78:82–92. doi: 10.1037/amp0001077

17. Yakovchenko V, Rogal SS, Goodrich DE, Lamorte C, Neely B, Merante M, et al. Getting to implementation: adaptation of an implementation playbook. Front Public Health. (2023) 10:980958. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.980958

18. Miller CJ, Sullivan JL, Connolly SL, Richardson EJ, Stolzmann KL, Brown M, et al. Adaptation for sustainability in an implementation trial of team-based collaborative care. Implement Res Pract. (2024) 5:26334895231226197. doi: 10.1177/26334895231226197

19. Metz A, Kainz K, Boaz A. Intervening for sustainable change: tailoring strategies to align with values and principles of communities. Front Health Serv. (2023) 2:959386. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.959386

20. Kilbourne A, Chinman M, Rogal S, Almirall D. Adaptive designs in implementation science and practice: their promise and the need for greater understanding and improved communication. Annu Rev Public Health. (2024) 45:69–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-060222-014438

21. Fralick M, Kesselheim A, Avorn J. Applying academic detailing and process change to promote choosing wisely. JAMA Intern Med. (2017) 177:282. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8503

22. Soumerai B, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. Jama. (1990) 263(4):549–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440040088034

23. VA PBM Academic Detailing Service. VA Academic Detailing Implementation Guide (2016). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration.

24. NARCAD—National Resource Center for Academic Detailing. Available at: https://www.narcad.org/ (Accessed October 3, 2024).

25. Pharmacy Systems Outcomes and Policy, University of Illinois Chicago. Creating and implementing an Academic Detailing (AD) program (2024). Available at: https://psop.pharmacy.uic.edu/adtoolkit/ (Accessed October 3, 2024).

26. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

27. Kirchner JE, Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Woodward EN, Smith JL, Proctor EK. Implementation strategies. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2024). p. 119–46.

28. Damschroder LJ, Sussman JB, Pfeiffer PN, Kurlander JE, Freitag MB, Robinson CH, et al. Maintaining implementation through dynamic adaptations (MIDAS): protocol for a cluster-randomized trial of implementation strategies to optimize and sustain use of evidence-based practices in veteran health administration (VHA) patients. Implement Sci Commun. (2022) 3:53. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00297-z

29. Damschroder LJ, Yankey NR, Robinson CH, Freitag MB, Burns JA, Raffa SD, et al. The LEAP program: quality improvement training to address team readiness gaps identified by implementation science findings. J Gen Intern Med. (2021) 36:288–95. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06133-1

30. Ragan AP, Aikens GB, Bounthavong M, Brittain K, Mirk A. Academic detailing to reduce sedative-hypnotic prescribing in older veterans. J Pharm Pract. (2021) 34:287–94. doi: 10.1177/0897190019870949

31. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J. (2009) 9:27–40. doi: 10.3316/QRJ0902027

32. Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. (2018) 23:42–55. doi: 10.1177/1744987117741667

33. Spall S. Peer debriefing in qualitative research: emerging operational models. Qual Inq. (1998) 4:280–92. doi: 10.1177/107780049800400208

34. Darawsheh W. Reflexivity in research: promoting rigour, reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Ther Rehabil. (2014) 21:560–8. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2014.21.12.560

35. Azjen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. (1991) 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

36. Smart MH, Monteiro AL, Saffore CD, Ruseva A, Lee TA, Fischer MA, et al. Development of an instrument to assess the perceived effectiveness of academic detailing. J Contin Educ Health Prof. (2020) 40(4):235–41. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000305

37. Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

38. Kunstler BE, Lennox A, Bragge P. Changing prescribing behaviours with educational outreach: an overview of evidence and practice. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:311. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1735-3

Keywords: academic detailing, implementation strategies, implementation science, tailoring strategy, QUERI, FRAME-IS

Citation: Domlyn AM, Hooks G, Freitag M, Evans L, Stewart M, Damschroder L and Sussman JB (2025) Core and modifiable components of academic detailing: demonstration of implementation strategy development, tailoring, and documentation process. Front. Health Serv. 5:1521504. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2025.1521504

Received: 7 January 2025; Accepted: 19 May 2025;

Published: 3 June 2025.

Edited by:

Jeremiah Brown, Dartmouth College, United StatesReviewed by:

Suzanne Kerns, University of Colorado, United StatesEkaterina Noyes, University at Buffalo, United States

Copyright: © 2025 Domlyn, Hooks, Freitag, Evans, Stewart, Damschroder and Sussman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ariel M. Domlyn, YXJpZWwuZG9tbHluQHZhLmdvdg==

Ariel M. Domlyn

Ariel M. Domlyn Gwendolyn Hooks1

Gwendolyn Hooks1