- 1School of Public Health, Faculty of Health, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia

- 3School of Humanities, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Faculty of Law and Justice, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia

- 5The Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 6Department of Management, Griffith Business School, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 7School of Public Health and Social Work, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 8Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, St Vincent's Hospital Sydney, Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia

- 9School of Clinical Medicine, St Vincent's Healthcare Clinical Campus, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of New South Wales Sydney, Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia

- 10Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Introduction: Rules, policies, and technologies are increasingly introduced in healthcare to reduce complexity and iatrogenic harm. One example is the implementation of Electronic Medication Management Systems (EMMS) to minimise medication errors. However, in hospitals where nurses primarily administer medications, research shows that nurses often adopt “workarounds” to overcome barriers in medication administration. This study explored how nurses experienced and perceived the use of workarounds in their daily medication administration practices. Understanding these feelings is crucial, as they are linked to both patient safety and staff retention.

Methods: This ethnographic study was conducted in six wards in two Australian hospitals across 91 shifts, 46 interviews, seven focus groups, and member-checking sessions with nurses and EMMS stakeholders (N = 113 participants). Data analysis used a general inductive approach.

Results: Nurses described positive, negative, ambivalent, and conflicting feelings about using workarounds. Some denied the use or tolerance of workarounds, despite them being routinely observed. Most reported a tension between the perceived necessity of workarounds, reluctance to deviate from policy, and the desire to be a good nurse. Workarounds were seen both as the trademark of an expert, mindful nurse and as deviations from the rules, unsafe for both patients and nurses.

Discussion: This study demonstrates challenges to patient safety associated with the tension between the necessity of workarounds and the desire to adhere to policy. This can create stress and anxiety among nurses. They experience a tension at the intersection of the necessity of workarounds to deliver care, to be a good nurse, and the desire to adhere to policy. The associated stress and anxiety can lead to burnout, professional disengagement, and attrition. The study proposes solutions to manage challenges associated with workarounds.

Conclusion: Workarounds are an inevitable aspect of healthcare delivery in response to standardisation. Negative perceptions of workarounds may inadvertently contribute to the very harm that standardisation seeks to prevent. A more open dialogue about their use is essential. Recognising their inevitability and equipping nurses to manage them constructively is key to reducing stress, preventing burnout, and enhancing patient safety.

Introduction

The development of rules, policies and technologies based on how care is thought to be delivered—work-as-imagined—without input from those delivering the care—work-as-done, leads to workarounds (1). Increasing numbers of workarounds to rules, policies and technologies introduced to reduce complexity, ironically increase it (2). Increased complexity has been linked with iatrogenic harm (3) which affects one in ten patients, accounts for over three million deaths per year (4) and is the tenth leading annual cause of death globally (5). It has been estimated that 50% of this harm is preventable and that medication-related incidents account for half of the harm (4). To mitigate iatrogenic harm, healthcare has adopted safety strategies from high-risk industries such as aviation and motor racing (6, 7–10). These include the implementation of technology, team-based training, and the development of rules, policies, and guidelines aimed at enhancing patient safety (11–13). A key strategy involves the organisation and standardisation of clinical practices (11, 14, 15), which when undertaken without input from those delivering the care, can introduce new risks, such as familiarity that leads to decreased vigilance or over-reliance on a single type of technology (16), and lead to workarounds.

The inherent complexity and unpredictability of healthcare often require practitioners to respond swiftly and adaptively. When resources are limited, this may necessitate creative problem-solving that occasionally involves deviating from established protocols. As highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses need to continuously reassess, reprioritise, and adapt to shifting circumstances, adapting to the complexity and unpredictability of care delivery in environments that frequently include operational failures and uncertainty (17, 18). While adherence to standardised procedures is said to underpin safe practice, there are instances where delivering safe care to an individual patient may require clinicians to work around certain policies or use technologies in unintended ways. Thus, workarounds can represent acts of resilience and serve as valuable opportunities for learning and system improvement (1).

While workarounds—also referred to as shortcuts, deviations, or temporary fixes—are common across everyday life and professional settings, including healthcare, engineering, and IT, published reviews on workarounds and the related concept of safety violations highlight a lack of clear definitions (19–24). This study adopts the definition of workarounds as practices that diverge from organisationally prescribed or intended procedures to circumvent actual or perceived barriers to achieving a goal, or to achieve them more readily.

Workarounds are widespread in healthcare (25, 26–29), where clinicians are often described as “masters at workarounds” (30:52). Their use has been documented across various contexts, including electronic health records (EHR) (8, 28, 31–34), high-pressure workloads (22, 35, 36), system inefficiencies (37, 38) and electronic medication management systems (EMMS) (19, 20, 38, 39). For example, in barcode medication administration (BCMA), nurses have been observed bypassing the requirement to scan patient wristbands by instead scanning barcodes on stickers or paper (40). Despite their ubiquity, workarounds almost never appear in official documentation such as policies and procedures and are rarely discussed openly and often omitted from formal accounts of nurse behaviour, making their contribution to care delivery and outcomes difficult to capture.

While traditional safety approaches (Safety-I) often view deviations from policy as threats to safety due to their potential to introduce variability and error (37, 41–43), more recent literature (Safety-II paradigm) offers a more nuanced view. Safety-II emphasises understanding of how people adapt successfully in complex, variable environments, suggesting that not all deviations are harmful, and some are in fact necessary for safe care (44). In this view, safety emerges not solely from compliance, but from the capacity of systems and workers to adapt. Nonetheless, organisational responses to safety tend to align more with Safety-I assumptions, where policy deviations are seen as inherently risky and in the minds of some, unacceptable, unethical (45, 46) and at times illegal (47). This may reflect regulatory pressures or risk management norms, rather than empirical consensus. By contrast workarounds reflect the real world of nursing work, in which they are often seen as essential to embody the traits of a “good nurse” such as time efficiency, a focus on patient safety, patient-centred care, and teamwork (1, 48–50). These competing perspectives, may create a source of stress when nurses feel compelled to use workarounds, potentially compromising nurses' well-being and thereby undermining patient safety (43, 51).

This is a critical issue, particularly as stress and burnout are correlated with patient safety and staff attrition (43, 51). Furthermore, the link between burnout and workarounds has been made clear in other work (43, 52, 53). Where autonomy is low and emotional stress or exhaustion is high, self- and supervisor-reported workarounds become more prevalent. Indeed, burnout can lead to more workarounds (53–55), lowered professional engagement (54, 55) and more adverse events (56, 57). The cyclical nature of burnout, lowered nurse engagement and associated workarounds can pose significant safety risks to patients and decrease work satisfaction for nurses, contributing to intent to leave and turnover rates (43, 55, 58).

The ability to independently resolve issues through workarounds may be interpreted as a demonstration of professional competence. Given their ubiquity and paradoxical role—both enabling care and carrying negative connotations—it is important to understand how and why nurses use workarounds. While there is growing interest in the types of workarounds employed and the motivations behind them (19, 28, 29, 39, 48, 59), less attention has been paid to how nurses feel when engaging in such practices. While noting the ubiquity of different types of workarounds across different contexts, given the use of workarounds occurs most frequently when implementing new technology (46%) and when administering medications (31%) (22), this study sought to address this knowledge gap by examining how nurses feel about using workarounds when administering medication using EMMS in everyday practice.

Despite variable evidence supporting their effectiveness (60–62), EMMS have been introduced in high-income health systems, primarily to: provide information support; and promote standard practice to reduce the incidence of medication errors (37, 63). Within an EMMS, electronic medication administration records (eMARs) provide a standardised process and record of a patient's ordered and administered medications. EMMS and eMARs—through the physical items and computerised programs that comprise them, and the policies that direct their use—dictate nurses' actions and their timing, establishing an order and routine to medication practice; thereby aiming to standardise practice, promote safety and the minimisation, or in an ideal world, elimination of errors. Mobile computer workstations, workstations on wheels [WOWs, known as computer on wheels (COWs) at the time of data collection], enable EMMS and eMARs to be taken to the patient's bedside.

Nurses' use of workarounds during medication administration using EMMS provides a lens through which to explore nurses' experiences and emotional responses when using workarounds. The results of this study can inform the development of strategies, including both practice and policy, to enhance patient safety.

Methods

We purpose-designed a multi-methods ethnographic study to examine the workaround theory–practice gap and reveal the intricacies of complex nursing work environments; the study involved process mapping, observation, focus groups and interviews. Workarounds, a form of articulation work (practices that get work back on track) (64), often remain invisible in formal accounts of nursing practice because these non-sanctioned strategies may involve deviating from official policy. Nurses may interpret their actions differently from others and, being accustomed to resolving problems independently, may not recognise their solutions as workarounds or deem them noteworthy. Given their informal and context-specific nature, observing workarounds in practice was essential. Ethnography was identified as the most appropriate methodological approach, as it prioritises first-hand engagement with the setting under study and situates observed behaviours within their broader organisational and cultural context.

Participants included EMMS implementation stakeholders and nurses from six clinical units across two hospitals, each employing distinct EMMS platforms. A triangulated data collection strategy was employed, incorporating direct observation, individual interviews, and focus group discussions. Data were collected across all shifts and days of the week to maximise variation and reduce the likelihood of overlooking key phenomena influencing nurses' enactment, rationale, and experience of workarounds. Data were analysed using a general inductive approach, which facilitated the emergence of themes grounded in the data and aligned with the study's research questions.

To establish a clear understanding of the intended workflow for medication administration, a “gold standard” process map was developed for each participating hospital. These visual representations outlined the prescribed steps for administering medications using the EMMS. The maps were informed by medication policy document analysis, participation in eMAR training sessions and consultation with EMMS implementation experts at each hospital (65). The process map at one hospital was structured around route of administration, and by regulatory requirements (medications requiring a witness, a co-signer, or neither) at the second hospital. The process maps were instrumental in identifying where workarounds occurred within the medication administration process.

Setting

Data were collected at two metropolitan university-affiliated teaching hospitals in Australia. Each hospital (Hospital A and Hospital B) had over 300 beds and well-established EMMS, with roll out commencing six years prior to the study. Three units were sampled at each hospital and comprised surgical, haematology, and four medical units [three 34-bed units (A1, A2, and A3) and three units with either 26 or 28 beds (B1, B2, and B3)]. Different models of nursing care (patient allocation or team nursing) and EMMS were used at each hospital.

Sampling strategy

The study employed a non-probabilistic, purposive sampling strategy to capture a specific group with experience and knowledge of EMMS. Novice and experienced nurses who used EMMS and EMMS implementation stakeholders (staff involved in implementation and support of EMMS) were included in the sample. To accommodate ever-changing demands across shifts nurses were invited by the researcher to participate if they were available when data collection was conducted. One nurse declined to participate. Participants were allocated a unique identification number.

Recruitment

Information sessions were conducted with the EMMS stakeholders and on the participating units where nurses were invited to join the study. Participant information sheets and consent forms were provided. A researcher visited the units several times prior to commencement of data collection to invite participants to the study, provide information as needed and orientate to the research task.

Participants

A convenience sampling approach was used and nurses working on the study units (N = 6) in two hospitals were invited to participate in the study if they were available during the data collection period. There were 113 participants in total, comprising 60 nurses (A1 = 26, A2 = 20, A3 = 14) and four EMMS implementation stakeholders at Hospital A, and 46 nurses (B1 = 15, B2 = 17, B3 = 14) and three EMMS implementation stakeholders at Hospital B. Most participants were full-time registered nurses with more than one year of experience.

Data collection methods

Observations: A combination of non-shadow and shadow observation was employed. Non-shadow observations collected data to build a picture of normative operating behaviours, assumptions, attitudes, interactions and beliefs. Rather than closely observing medication administration, non-shadow observations noted practices, communication, artefacts (EMMS, notes and equipment), rituals and symbolic behaviour visible on the unit. Clarification of observed behaviours and interactions was sought from participants through opportunistic questioning—when prompted by participants, during shifts without disrupting workflow, at shift end, during interviews, or at the next suitable encounter. This process supported the interpretation of how nurses made sense of their actions and contributed to a contextualised account of each setting, including events and behavioural rationales from the participants' perspectives.

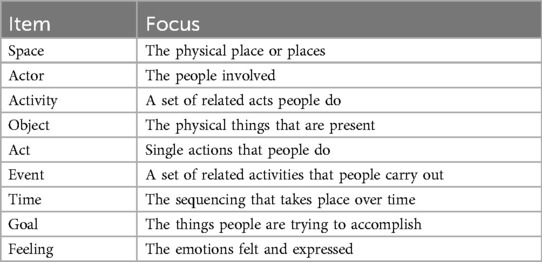

Shadow observations involved observations of a nurse during medication administration using the process map to identify workarounds. They were also conducted during other activities that did not involve patient personal care. Shadow observations were conducted to examine how nurses administered medications and engaged in related tasks, with a particular focus on identifying workarounds, their contextual influences, and how nurses responded to their own and others' use of such practices. Variations from the standard process were explored with participants to determine whether they constituted workarounds. Observations were conducted during morning (n = 44), evening (n = 35) and night shifts (n = 12) seven days a week. Given the temporal influence, and inseparability, of medication work from nurses' other work (66), nurses' use of workarounds with EMMS was examined in the context of nurses' work across a shift and, as far as possible, for complete shifts. Observation times ranged between two-and-a-half to nine hours twenty minutes. All activities observed during the time frame were documented, including omissions of expected behaviour. Spradley's framework (67) of generalised concerns (Table 1) guided note-taking to structure data recording. Additionally field notes captured nurses' explanations and reflections on their rationale for and experiences of using workarounds. These discussions during observations supported ongoing formative member checking.

Table 1. Strategies for ethnographic observation note taking (67:78).

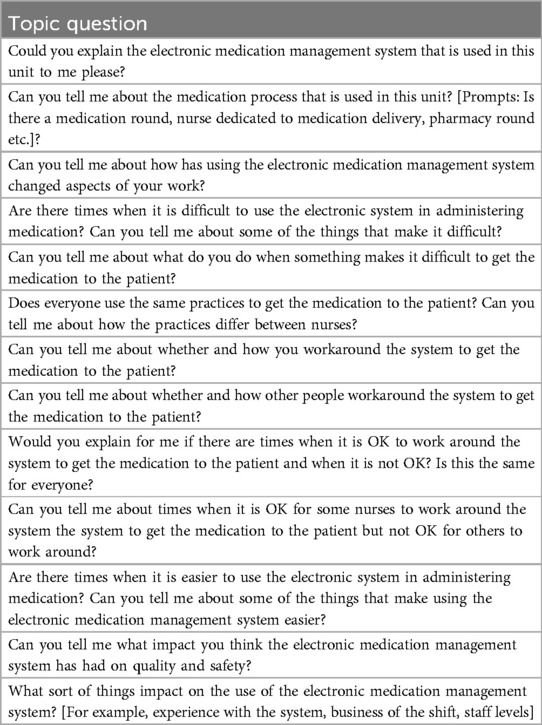

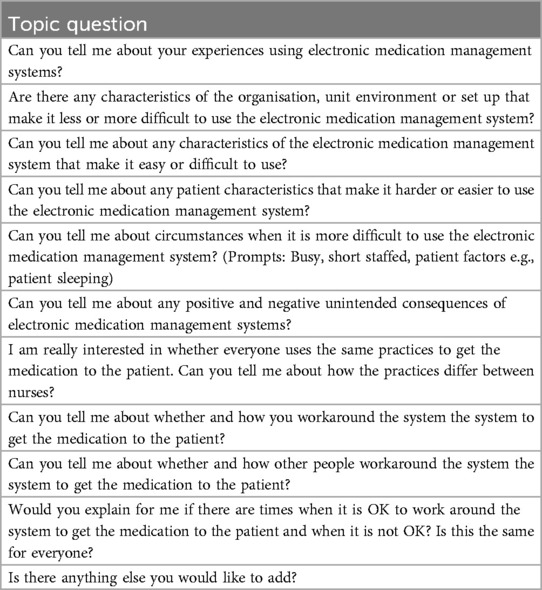

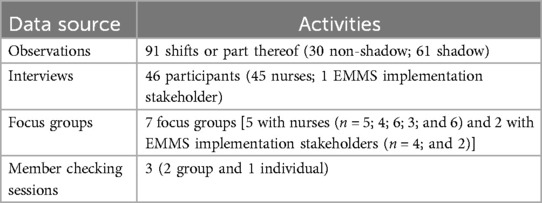

Interviews and Focus Groups: Face-to-face semi-structured interview and focus group data complemented observational data. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to garner individual's perspectives about workarounds. Focus groups were employed to generate interaction to capture the collective view on workarounds. Development of the interview and focus group topic guides was informed by literature and the expertise of the research team. Open-ended questions explored participants' experiences of using EMMS and workarounds (Tables 2, 3).

Interviews and focus groups were conducted in participants' work units or offices and transcribed for analysis. Interviews lasted between 15 and 89 min (mean: 34 min; median: 31 min). Focus groups with nurses ranged from 37–51 min (mean: 42 min; median: 41 min), while those with EMMS implementation stakeholders averaged 97 min. A summary of data sources can be found in Table 4.

Data analysis

Data analysis employed the general inductive approach (68). In keeping with a general inductive approach to analysis a blended “grounded” coding for themes and concepts, and “responsive formal coding,” which focused on coding against the research question rather than line-by-line coding was employed (69). The observational field notes and focus group data were coded for categories identified in the interviews. QSR NVivo 10 software was used to manage interview data, and an Excel spreadsheet used for the field notes and focus group material.

Step 1: familiarisation with the data

The initial phase involved an immersive reading of interview transcripts and field notes, during which preliminary patterns, reflections, and ideas were noted. These were informed by contemporaneous reflections recorded during data collection. Transcripts were imported into QSR NVivo 10 software to facilitate systematic data management throughout the analysis.

Step 2: coding framework development

Identifying workarounds

Given the study's focus on nurses' use of workarounds, data were examined for behaviours aligning with the definition of workarounds. Process maps served as a benchmark against which observed or described behaviours were compared. Deviations from the prescribed process, such as omitting a formal identification check or using informal identifiers (e.g., bed numbers or handwritten notes), were coded as workarounds when they were used to overcome perceived time or workflow barriers.

Developing additional codes

Following the identification of workarounds, relevant transcript sections were re-examined to generate descriptive, content-driven codes. Coding was iterative and reflexive, with new codes prompting re-evaluation of previously coded data. Multiple codes were often applied to the same data segments. Rigorous attention was paid to remain grounded in the data, avoiding over-interpretation. Coding decisions were discussed with research team members and a qualitative coding expert.

Step 3: thematic refinement and conceptual development

Coded data were grouped into themes representing similar phenomena related to workarounds. Themes were then examined for interrelationships, forming broader categories and, ultimately, abstract concepts. Subsequently, observational field notes and focus group data were coded using the interview-derived categories. This process aimed to enrich and interrogate the emerging concepts while remaining open to new categories. An Excel spreadsheet was used to track category occurrences, with an additional column for novel insights not captured by existing codes.

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by a Lead Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), (HREC/10/XXX/116) (HREC name deidentified with XXX) and ratified by University of New South Wales HREC (HC09223). Participants provided written consent which was reestablished throughout the data collection process.

Results

Observational data revealed both similarities and differences in local practices, communication preferences, workflow, and nursing care models across the study units. The physical layout of units limited visibility across sections, potentially affecting staff awareness of colleagues' workloads. In all units, oral medications were dispensed by pharmacy and stored in locked bedside drawers, while controlled, refrigerated, and injectable medications were stored in the medication room. A locked metal cupboard (DD cupboard) housed Schedule 8 and Schedule 4D medications (DD medications), with corresponding burgundy A4 drug register books nearby. Administering DD medications required two nurses to verify the order, reconcile stock, witness preparation and administration, dispose of any residue appropriately, and sign the register and medication chart. These procedures were governed by legislation aligned with nurses' scopes of practice.

Medication rounds were structured, the heaviest workload occurring in the morning following handover, when demand for WOWs was greatest. Each unit had between five and ten WOWs available. Two models of nursing care were observed across the participating units: a patient allocation model at Hospital A and a team-based model at Hospital B. At Hospital A, individual nurses were assigned specific patients and held responsibility for their care throughout the shift. In contrast, Hospital B employed a team nursing model, where a group of nurses, led by a team leader, collectively cared for a group of patients. Staffing strategies also differed between the hospitals. At Hospital A, workforce shortages were primarily addressed through the use of overtime, agency, and casual pool nurses. At Hospital B, staff were more commonly redeployed from other wards to cover shortages, with minimal reliance on agency or casual staff during the study period. In addition to using different EMMS platforms, the hospitals differed in their EMMS access protocols—one granted eMAR access to all medication-endorsed nurses post-training, while the other restricted access to permanent staff who had completed training—and in their nursing care models (team-based vs. patient allocation). The eMAR is accessed at stationary desktop computers or via laptops mounted on trolleys, “workstations on wheels” (WOWs).

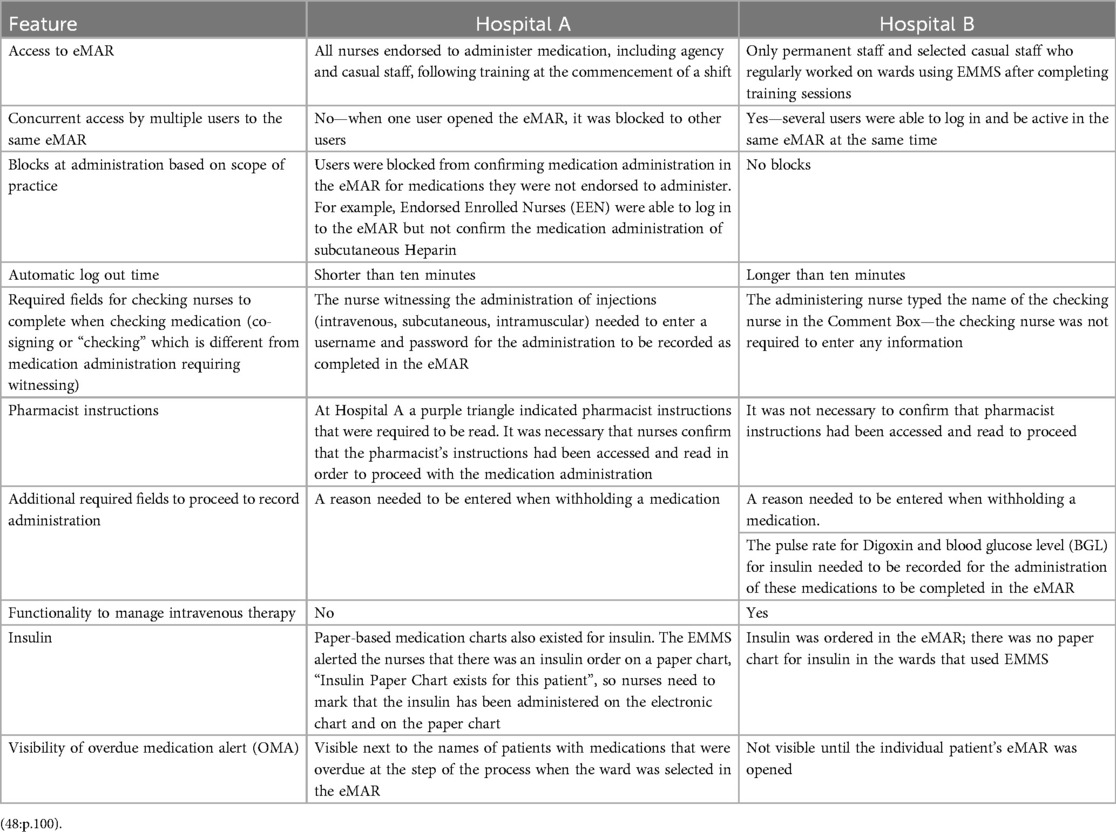

The study also identified several key differences in the configuration and functionality of the eMAR systems across the two participating hospitals that were relevant to nurses' use of and perceptions of workarounds when administering medication (Table 5). For example, during initial observations at Hospital A, it became apparent that the overdue medication alert (OMA) within the EMMS elicited strong emotional reactions from nursing staff. Nurses at Hospital A expressed more pronounced emotional responses to OMAs than their counterparts at Hospital B. At Hospital A, OMAs were prominently displayed next to patient names in the EMMS interface. Patient allocations were recorded in a staffing book and, in some units, also displayed on whiteboards in the main office—commonly referred to as the “flight deck”—which served as a central hub for clinical staff. This visibility made it easy to identify which nurse was responsible for any overdue medications. Nurses at Hospital A reacted to OMAs as indicators of personal failure, describing feelings of stress, frustration, worry, and inadequacy. Although formal reprimands were rare, the alerts created a sense of time pressure and concern about professional judgement. Nurses associated the alerts with being seen as “not coping”, “lazy”, or “neglecting patient care”.

Table 5. Differences between site-specific electronic medication administration record (eMAR) features identified as relevant to this study.

96: I was beside myself when I saw that clock. I'd failed. When I first came−‘No, No’−I thought. I was really, really stressed because I wasn't getting through the medication by nine o'clock but that was because I saw the clock. (Focus Group: Nurses_ID_4)

At Hospital B, the OMA was only visible when a clinician opened an individual patient's electronic medication chart, making it less prominent than at Hospital A. This reduced visibility was coupled with a team-based model of nursing care, in which responsibility for medication administration was shared among team members. Participants at Hospital B generally viewed the OMA as a simple reminder rather than a source of pressure.

I like it because it's readable. It's going red when it's overdue or you just forgot about it, or if we don't have any stock in the ward, it goes red. It means that you didn't give it−gives the nurses a warning. (Interview: Nurse_42)

To avoid being late with medications, in both hospitals nurses were observed to use a variety of workarounds. For example, the nurse:

put the meds in the med cup and put another cup on top of it−put on something, like a piece of paper or Alco wipe, what the bed number is… line the med cups up and then take them to the patients one after another [Field Notes Observation (FNO): _111_AM]

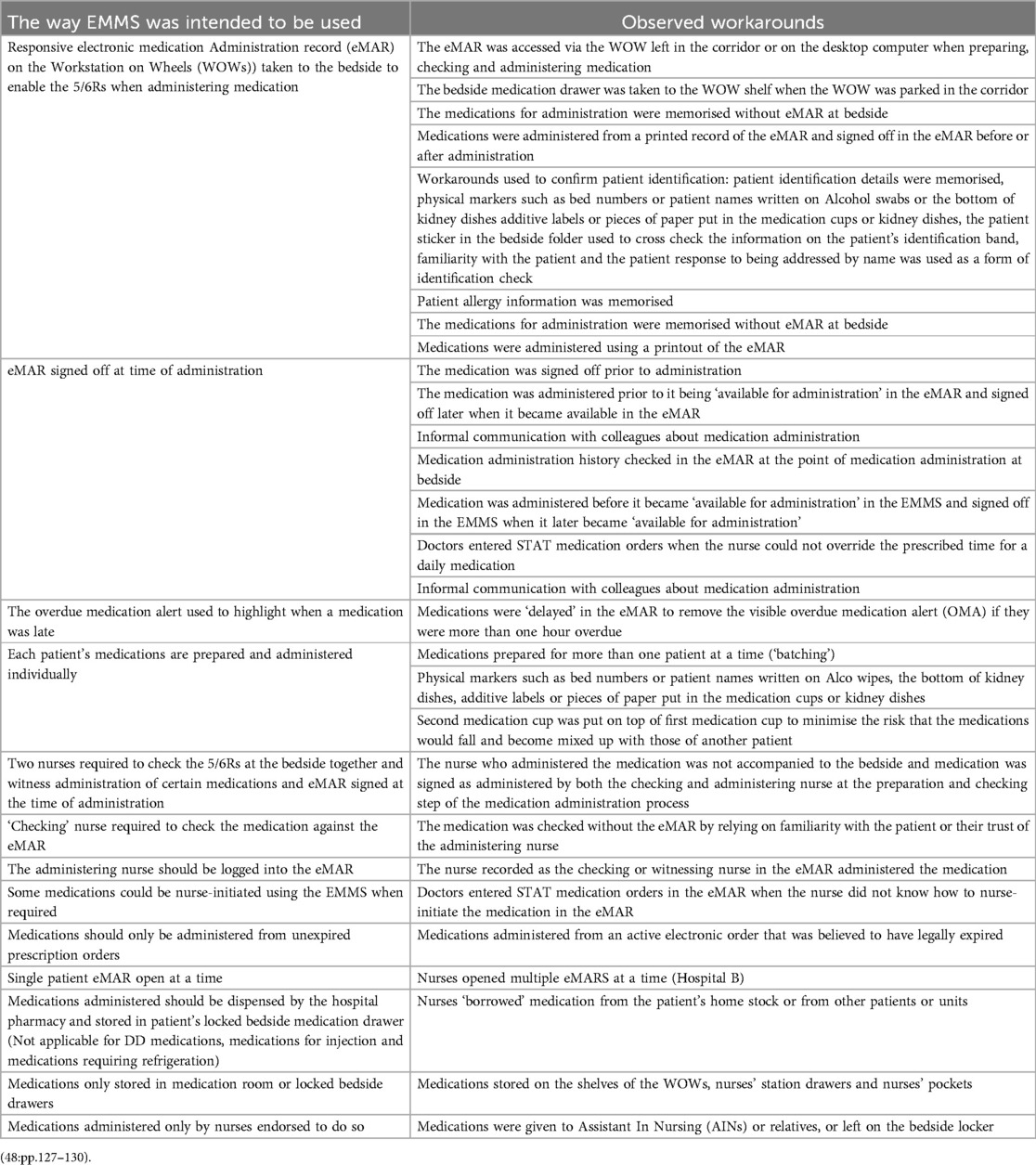

Observed workarounds

Workarounds were employed in the use of EMMS for medication administration. These workarounds were applied either individually or in combination with others, initially giving the impression of considerable variability. However, discernible patterns emerged in how these combinations were enacted, explained, and experienced by nurses. The variation observed in the workarounds can be understood as resulting from the combination of each process step workaround with none, one, or multiple others. The workarounds presented in Table 6 are illustrative rather than exhaustive examples of observed practices.

How nurses felt about using workarounds

Overarching duality of feelings

Nurses had mixed feelings about using workarounds. Some felt uneasy or worried about possible consequences, while others saw them as a sign of being resourceful and resilient. How individual nurses felt about using workarounds was influenced by seniority and experience, ward culture, type of task and workaround required. Across both hospitals, participants identified specific units where deviating from EMMS policy through workarounds was not considered acceptable and therefore using them evoked negative emotions. Casual pool nurses, who worked across multiple units, described how local norms could either discourage or enable such practices. While some participants admired units that strictly adhered to policy, others viewed them less favourably—citing, for example, that nurses on a particular ward often worked through breaks and stayed late due to their avoidance of workarounds. Whether tasks were left for the next shift was influenced by unit culture. In some units, nurses expressed concern about being perceived as lazy if medications were delayed or tasks left incomplete. In these settings, workarounds were more commonly used to maintain an appearance of efficiency. Participants also reported adopting local workarounds when working on unfamiliar units to avoid disrupting team routines.

One of the pool nurses explains that when you work on different wards you play by their rules. Some wards have a slightly different way of doing things, different preferences—the nurses get used to how it is done on the ward. [Documented conversation as part of Field Notes Observation (DC/FNO): _57_PM]

Negative emotions

Feelings of uncertainty and concern about professional retribution surrounded workarounds. Nurses reported feeling unsettled at their use, particularly as the official stance on workarounds was that they posed a risk to patient safety and compromised staff integrity. They also described tension, powerlessness and fear when management put them in a position in which they were expected to not follow policy. The perception was that in some instances “management” tacitly expected nurses to break policy and systematically “turned a blind eye” to this. At the same time, nurses felt that were an incident to occur following a workaround, the organisation would not support them because they had not followed policy. Nurses frequently suggested that punishment or reprimands were more likely for some workarounds than others. For example, from the field notes during observation of several nurses having a discussion at a nurses' station between a casual RN and permanent junior RNs:

The nurses are discussing the organisational policy, which is that permanent staff need to hold ‘the keys’—not casual and not agency. However, they said, they will send a casual to a ward and if necessary the casual will be In-charge—seniority over permanency when it suits the organisation—one of the casual nurses says, that the management turns a blind eye, and asks—‘What are the casual staff supposed to do? But if there is an incident, I am hung out to dry because I know that it was against hospital policy for a casual to hold the keys. [Documented conversation as part of Field Notes Observation (DC/FNO): _126_PM]

Nurses indicated that there were some policies that could be worked around and others that could not; for instance, if a patient had severe chest pain in the presence of the doctor, nurses could administer intravenous morphine, but were not permitted to do so at any other time. Similarly, when medication orders had expired but they could not get a doctor on the unit, nurses described feeling conflicted between administering the medication from an “expired” order for the patient's benefit and not doing so to protect themselves from professional recriminations. In such instances, failing to use a workaround to administer medication was considered potentially harmful to the patient but, at the same time, doing so was perceived as having possible professional ramifications.

Other examples of using workarounds to support patient safety included numerous observations of nurses not taking the WOW to the bedside when the patient was infectious or isolated for immunosuppressed:

A nurse justifies why she left the COW at the door, explaining that you have to weigh up the risks—risking spread of MRSA [Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus] and VRE [Vancomycin Resistant Enterococcus] vs. not following the 5Rs* of giving medication. [(DC/FNO): 204_Morning Shift]

* The 5Rs of medication safety: right patient, right medication, right dose, right route, right time

Participants acknowledged that while certain workarounds reduced the risk of cross-infection, they simultaneously heightened the risk of medication errors. To mitigate this, nurses employed a range of secondary workarounds to verify medications and patient identities against the eMAR. These included writing medication names on paper, preparing ward stock medications in the medication room, labelling medication cups with patient details, and memorising information from the eMAR. Some printed the eMAR and used it within isolation rooms, discarding it there to prevent contamination, and later signed off medications outside the room. Others avoided bringing the COW to the bedside by transporting the medication drawer to the COW shelf, which they cleaned afterwards. In certain cases, a colleague would stand at the door and read out eMAR details while the nurse prepared and administered medications, particularly for controlled drugs.

Many nurses were reluctant to discuss workarounds. Their body language, hushed tones, and descriptors such as “dodgy” and “naughty” conveyed their discomfort. Phrases such as “I don’t know if I should be telling you this” or “I know I shouldn't but …” frequently preceded discussion about workarounds. Fear of professional retribution and consequences was often linked to these discussions. To illustrate, having just observed a nurse complete a medication round:

16:40—I asked about the times when the nurses take the medication trolley to the bedside and sometimes that they don't. “We are naughty, you are supposed to take the trolley to the bedside and check the armband for every single medication even Panadol.” I pursue any reasons why sometimes it happens and others not … “it’s just some staff. In the morning I start and I try to do the right thing”. [(DC/FNO): 68 Evening Shift])

The tension nurses expressed about using workarounds was exemplified in nurses' accounts of the gap between what was taught in university as “ideal care” and what was realistic in everyday practice. Delivering care in the “real” world, nurses argued, required workarounds to get the job done, and it was evident that workarounds with the EMMS flowed into other areas of care delivery. The nurse repeatedly shook her head as she explained the following while sitting at the nurses' station having completed the evening medication round:

There is a gap between education during training about how to give medications and the reality of when you get on the wards. I would like to say, yes the 5Rs are important, but I would like to know which are the most important because you don't have time.

[(DC/FNO): 71_Evening Shift])

The complexity of the experience of tension when using workarounds was illustrated by a nurse participating in the observations, a focus group and an individual interview. The nurse showed mixed views about workarounds—saying in a one-on-one interview that they never used them, even though they were seen doing so, and agreeing in a group discussion with senior staff that workarounds are a normal part of daily work.In doing so they highlighted the gap between what nurses espoused publicly, the sacred, and the profane, what they talked about off the record and what they actually did (70).

Some nurses managed the tension between organisational expectations of timely medication administration (“work-as-imagined”) and the realities of clinical practice (“work-as-done”) by administering medications early but delaying documentation in the EMMS until the scheduled time. This workaround allowed them to appear compliant while maintaining workflow efficiency. To mitigate the risk of error, nurses often communicated informally with colleagues to confirm that medications had already been given. Although the EMMS recorded the time medications were signed off, EMMS implementation stakeholders acknowledged that these records did not always reflect real-time practice. This highlights a disconnect between system data and actual clinical activity:

I can, from a system point of view, have a look … From a system point of view, you can see what's occurred and then you have to make some inferences as to what the actual workflow behind that was. (Focus Group: EMMS implementation stakeholders_ID_2)

Nurses expressed frustration, feeling trapped in a “damned-if-you-do and damned-if-you-don’t” situation where they had to justify using workarounds in an under-resourced system. They believed workarounds were acceptable when used safely by experienced staff, but not in all situations. For example:

“To be honest, if we went two to the bedside for every single IV medication and infusion, the patients would die from not getting their medications … because there isn't enough time … You might both check and do it by the book but the patient would be dead because they wouldn't have got half of their meds…” [Nurse 69] told me that for some of the medications someone definitely goes with the administering nurse—ALWAYS because those medications are more complex or dangerous or they involve steps that need to be exactly … This increases the chance of compliance, but you must always be asking yourself … “what is better for the patient, what is safer for the patient? Constantly weighing it up”. [(DC/FNO): _69_Evening shift])

[Nurse 44] says “I know how it is meant to be done BUT we have to get care to our patients. We do the best we can we choose the best way to get things done. We can't do it all”. [(DC/FNO): _44_Evening shift])

Ambivalence

Some workarounds did not appear to evoke an emotional response or attitude. Several nurses described theirs and their colleagues' workarounds using “matter of fact” tones, without using qualifiers or words that depicted emotions. These descriptions of workarounds were not couched in positive or negative terms, rather they were part of the adaption to the EMMS, and to delivering care at a broader level, and were sometimes presented as a “fait accompli”.

Legibility, and it is quite user friendly now that we've ironed out all the bugs and worked out our shortcuts and ways around doing things and stuff like that. (Interview: Nurse_61)

While such statements may initially appear to reflect increased familiarity or efficiency with the system, closer examination reveals that the term “shortcuts” refers to informal, unsanctioned adjustments to the intended use of EMMS. These adaptations represent workarounds because they deviate from prescribed protocols and workflows.

While some expressed that they did not use workarounds themselves, they sounded noncommittal about their colleagues doing so. For example, Nurse_42 reported that whether nurses worked around the policy that required them to take the WOW to the bedside was not considered problematic, as long as they did not breach “the standards” by which they judge their performance as a good nurse,—that is, patient-centred, safe, team player and able to deliver care efficiently.

I've seen some people—they have their own way. As long as I—personally I don't care, if they're not with their medication, the electronic medication, or take the COW or whatever—how they want to do it, as long as they don't breach ‘the standards’. (Interview: Nurse_42)

When describing her colleagues' use of workarounds, Nurse_53 spoke in a neutral and non-judgemental tone, simply acknowledging that some nurses engaged in workarounds while others did not.

I don't personally, but people do their own practices. Sometimes you will see people writing, putting it in a kidney dish and writing a number or a patient's drug and maybe racing them up because they've got all their meds from the medication room or something or other. I mean it's rare. They might line them up like the Heparins or Calciparines or Clexanes and things ready to go with numbers and things. I don't do that. I just collect what I need and palm them out as I go. (Interview: Nurse_53)

Positive emotions

Many nurses expressed positive feelings and attitudes to workarounds, describing them in such terms as “resilient” and “resourceful”.

Nurses are resilient—they can ensure that the basic care is given and then write a note to sign off a medication later. (Interview: Nurse_26)

Personally, I don't know shortcuts through it but then again—or workarounds or whatever they call it … I don't doubt that nurses and medical staff being extremely resourceful people, that if they're there, they'll find them quite quickly. (Interview: Nurse_20)

For some, workarounds were viewed as a way of “thinking outside the box” (Field Notes: Observation_77_Evening shift) and their use indicative of an ability to problem-solve and personalise care through innovation. Nurse 50 drew on the notion that in a fluid working environment nurses use workarounds to adapt to and navigate the unexpected:

Nurses put their workarounds in place because they're dealing with any given situation that is never the same. (Interview: Nurse_50)

Having recourse to workarounds that involved more than one nurse was often perceived as a proxy for being a team player and indicated trust in each other's competency as a nurse. For example, Nurse 31 interpreted her colleagues' workaround of the policy requiring them to witness her administrating a medication as demonstration that they trusted her professional practice:

I see that my colleague trusts me … it's a kind of validation, like a respect—they trust you, as an RN. (Interview: Nurse_31)

Discussion

This study examined how nurses feel towards workarounds when administering medication using EMMS in their everyday clinical practice. We know that when administering medication using EMMS nurses deploy two type of workarounds—primary and secondary—alone or in combination, to achieve multiple purposes (48). Primary workarounds come into play when circumventing a barrier to achieving a goal; and secondary workarounds are mobilised to overcome barriers produced by using a primary workaround (48). The reasoning nurses provide for applying workarounds is to be a “good nurse”, to be time-efficient, safe, patient-centred or to be a team player (1, 48).

This paper adds ethnographic texture to these findings by reporting how nurses feel about using workarounds to be a “good nurse”. It highlights that whether nurses had recourse to, or avoided using workarounds, there were simultaneous feelings of ambivalence, negativity, and positivity, depending on context, setting and type of workaround mobilised. The findings highlight how the complex and interconnected dynamics of individual actions, team priorities and orientations, and organisational constraints shape the practice environment—one that both enables the creation of workarounds and simultaneously tends to deny their existence.

An omnipresent feature of nursing practice is fear of professional retribution, particularly if an adverse event occurs (37, 41–43, 45–47). These incompatible realities leave nurses facing an invidious choice: to be a “good nurse”, sometimes bypassing rules to provide better care, potentially incurring consequences for not following policy; or to strictly follow the rules and cause potential care delays, incurring the frustration of their colleagues and potential patient safety issues. This situation can lead to internal stress, which is a potential contributor to burnout and professional disengagement, as we have documented here.

Our findings reveal that nurses had conflicting feelings about workarounds—both their own and their colleagues'. Most described a tension between the perceived necessity of workarounds, the hesitation and unwillingness to deviate from policy, and the desire to be a “good nurse”. On the one hand workarounds were seen to demonstrate an ability to “think outside the box” and were the hallmark of an expert: a mindful nurse who doesn't “blindly follow the rules”. On the other hand, as deviations from the rules, workarounds were also conceptualised as unsafe both for patients and nurses themselves and, therefore, unprofessional. These conflicting feelings can lead to anxiety.

In her seminal work examining the high levels of stress and anxiety among nurses, Menzies (71) described social defences that nurses employ to reduce anxiety associated with their work. These include eliminating decisions through ritual task performance; reducing the weight of responsibility in decision-making by checks and counterchecks; and purposeful obscurity in the formal distribution of responsibility (71). Thus, it appears that nurses have long relied on “following the rules”, particularly in relation to medication administration, to manage tension inherent in their work. Yet, as demonstrated in our study, nurses perceive that they need to work around rules to deliver care, to be a good nurse. It is unsurprising then that needing to work around the rules creates stress, and anxiety.

Tension, burnout and disengagement

Workarounds have been described as the byproduct of workload pressures and as “survival mechanisms” (58) for healthcare professionals navigating a paucity of resources, inadequate systems and professional burnout. Tension arises in professionals caught between needing to use workarounds but in doing so breaching organisational rules. The study has noted the link between burnout and workarounds, established in the literature (43, 52, 53). The intricate dynamics and impact, for individuals and nursing cohort, needs further investigation.

Potential solutions

On the basis of the foregoing, how might we formulate a strategic way forward?

De-implementing low-value care/policies that do not support patient safety: Focusing on and removing mandated nurses' work that is not essential or evidence based could help alleviate the pressure to use workarounds. For instance, recent research indicates that requiring double-checking of medication administration at the bedside offers minimal safety benefits if not done independently (72). The findings of our study highlighted the stress and professional vulnerability nurses experience when they felt forced to work around medication double checking policies because of a lack of resources and the need to administer medication in a timely way. These findings are supported by an international study conducted in Australia and the United Kingdom which identified double-checking medication as a safety practice that health care staff perceived to be of low value (sometimes because they could not complete it independently) (73). Simplifying procedures and removing low-value safety practices could reduce the need for nurses to use workarounds. However, stopping practices introduced to reduce uncertainty and that are perceived to increase patient safety (71) (even when not evidence based) is notoriously difficult (74). We need to specify the conditions under which the de-implementation of low-value practices can occur, and how doing so reduces nurses' need to use workarounds.

Implementing the “Traffic Light Model”: Adapting the “Traffic Light Model” used in antimicrobial prescribing (75) can shift us along the continuum of managing workarounds more effectively. This model categorises policies into: Green Policies: Allow workarounds if they are beneficial and counter secondary harms; Orange Policies: Permit cautious workarounds with senior guidance; Red Policies: Prohibit workarounds entirely. This approach acknowledges the inevitability of workarounds and provides a structured way to manage them, ensuring patient safety and nurse autonomy.

Preparing Newly Graduated Nurses: Given the high rate of attrition among newly graduated nurses due to disillusionment and dissatisfaction (76, 77), it is crucial to expose them to the reality of workarounds before they graduate. Creating realistic expectations and educating neophyte nurses about the challenges they will face and preparing them to navigate these challenges can reduce stress and improve retention rates (78). This preparation should include training on how to identify and manage workarounds safely and effectively.

Enhancing psychological safety and autonomy in the workplace is crucial for supporting nurses effectively. Encouraging open communication and providing robust support systems are essential strategies to help nurses manage stress and maintain their professional engagement. By fostering an environment where nurses feel safe to voice their concerns and have the autonomy to make decisions, we can contribute to the reduction in burnout and the need for workarounds (58). The results of our study might assist clinical leadership in acknowledging workarounds, understanding their underlying triggers, and working towards reconciling official procedures with real-world situations (79). This approach can help nurses in clinical practice reflect on and reconcile the demands of their organisations with their patient-oriented professional needs (59).

Change the dichotomous conceptualisation of workarounds to align with other research which underscores the complexity of workarounds in healthcare settings. Boonstra et al. (2021) (28) present a typology of enduring workarounds in Electronic Health Records (EHR), helping users and managers differentiate between harmful and less harmful workarounds to inform their decisions on discouraging or legitimising them. Additionally, Tucker et al. (2020) (36) suggest that workarounds used to navigate operational failures can lead to more positive patient outcomes, while those deployed to avoid processes are associated with negative outcomes. Investigating coping strategies could help managers and employees manage job stress and reduce burnout in the healthcare sector, thereby enhancing effectiveness and efficiency through safety workarounds (80).

Aligned with the findings of this study, Goff et al. (2021) (81), drawing on interview data from a policy pilot in general practice within the National Health Service in England, challenge the dichotomous conceptualisation of workarounds in relation to access to care. They argue that workarounds can both support and undermine policy pilots, making them inherently political as employees must balance the consequences for themselves and the wider organisation.

Strengths and limitations

Most studies examine medication administration on day and evening shifts (27) on weekdays (40). This study was conducted across all shifts and days of the week enabling the capture of primary and secondary workarounds. The strength of in situ studies of behaviour is their capacity to understand context but this limits generalisability to other settings (82). To minimise this limitation, the study sample covered six units in two hospitals. Not every type of workaround was seen; rather it sampled for variation.

A potential limitation of this study was the Hawthorne effect, which has been observed in some observational studies examining nurses' compliance with interventions (70). However, prolonged engagement in the field allowed nurses time to become accustomed to the researcher's presence, thereby reducing the likelihood of sustained behaviour changes aimed at presenting a more favourable image (83).

Pre-planned observations may mean some aspects of care may have gone unnoticed; especially with a sole field data collector. To minimise these effects regular debriefing with the research team was conducted and a reflexive approach taken. The researcher may not have seen surreptitious behaviours that complied with policies but manifested as workarounds. In some circumstances the researcher was limited to visible observation data and was unable to hear communication between nurses and patients.

Conclusions

Workarounds are an inevitable part of health care delivery. The rhetoric that workarounds are always harmful and unprofessional is not only unrealistic but indefensible and causes tension in nurses. This tension will likely contribute to stress and burnout, which leads to more workarounds and unsafe practices. Negative attitudes towards workarounds must be addressed, and a more open and nurse-centred discussion about their use encouraged.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the authors do not have ethical approval to share the qualitative data sets. Requests to access the datasets should be directed toZGVib3JhaC5kZWJvbm9AdXRzLmVkdS5hdQ==.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was granted by a Lead Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), (HREC/10/XXX/116) (HREC name deidentified with XXX) and ratified by University of New South Wales HREC (HC09223). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Participants provided written consent which was reestablished throughout the data collection process.

Author contributions

DD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. WL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. DC: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. DB: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RH: Writing – review & editing. JC: Writing – review & editing. JB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Program Funding Scheme (grant number 568612). JB's work is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (APP1054146).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the traditional custodians of the lands on which the study was conducted, the Gadigal, Wangal, Bediagal and Burramattugal people of the Eora and the Dharug Nations and pay our respects to Aboriginal Elders past present and emerging. We also acknowledge and are so grateful to the nurses and EMMS stakeholders who participated in this study. The authors would also like to make a special acknowledgement to the late Professor Joanne Travaglia, who played an instrumental role in the interpretation of data and in the drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. This research was part of PhD study conducted at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (Microsoft 365 Copilot) was used to edit some sections of the manuscript “Please rephrase the following making it clearer and more succinct”.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Debono D, Clay-Williams R, Taylor N, Greenfield D, Black D, Braithwaite J. Using workarounds to examine characteristics of resilience in action. In: Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wears RL, editors. Delivering Resilient Health Care. New York, NY: Routledge (2018). p. 44–55.

2. Woodward S. Moving towards a safety II approach. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. (2019) 24(3):96–9. doi: 10.1177/2516043519855264

3. Woods DD, Patterson ES, Cook RI. Behind human error: taming complexity to improve patient safety. Handb Hum Factors Ergon Healthc Patient Saf. (2007) 459:476.

4. World Health Organization. Patient safety: World Health Organization (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety (Accessed June 15, 2025).

5. Flott K, Fontana G, Darzi A. The Global State of Patient Safety. London: Imperial College London (2019).

6. Massaad C. Formula 1 Steering the Wheel of Medical Car (E): A Review and a Preview (2024). Available at SSRN 4700086.

7. Catchpole KR, De Leval MR, McEwan A, Pigott N, Elliott MJ, McQuillan A, et al. Patient handover from surgery to intensive care: using formula 1 pit-stop and aviation models to improve safety and quality. Pediatr Anesth. (2007) 17(5):470–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02239.x

8. Dominiczak J, Khansa L. Principles of automation for patient safety in intensive care: learning from aviation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. (2018) 44(6):366–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.11.008

9. Torres Y, Rodríguez Y, Pérez E. How to improve the quality of healthcare services and patient safety by adopting strategies from the aviation sector? J Healthc Qual Res. (2022) 37(3):182–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhqr.2021.10.009

10. Webster CS, Henderson R, Merry AF. Sustainable quality and safety improvement in healthcare: further lessons from the aviation industry. Br J Anaesth. (2020) 125(4):425–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.045

11. Greenfield D. Accountability and transparency through the technologisation of practice. In: Braithwaite J, Hyde P, Pope C, editors. Culture and Climate in Health Care Organisations. London: Palgrave Macmillan (2010). p. 185–95.

12. Greenfield D. Changing Practice in a Health Organisation. Köln: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing (2009). Available online at: http://www.amazon.com/Changing-Practice-Health-Organisation-Technologisation/dp/3838300157/ref=sr_1_5?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1271630414&sr=1-5

13. Claridge T, Parker D, Cook G. Pathways to patient safety: the use of rules and guidelines in health care. In: Walshe K, Boaden R, editors. Patient Safety Research into Practice. Berkshire: Open University Press (2006). p. 198–207.

14. Gawande A. The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. New York: Metropolitan Books-Henry Holt and Company (2009).

15. Fracica PJ, Fracica EA. Patient safety. In: Giardino AP, Riesenberg LA, Varkey P, editors. Medical Quality Management. Cham: Springer (2021). p. 53–90.

16. Fuller HJ, Arnold T. The flip side of the coin: potential hazards associated with standardization in healthcare. International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics. Springer (2021).

17. Jaarsma T, van der Wal M, Hinterbuchner L, Köberich S, Lie I, Strömberg A. Flexibility and Safety in Times of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Implications for Nurses and Allied Professionals in Cardiology. London, England: Sage Publications Sage UK (2020).

18. Dippel KS, Kelly EK. Implementation of a nurse practitioner-led drive-through COVID-19 testing site. J Nurse Pract. (2021) 17(2):185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.10.004

19. Clark D, Lawton R, Baxter R, Sheard L, O'Hara JK. Do healthcare professionals work around safety standards, and should we be worried? A scoping review. BMJ Quality and Safety. (2024) 34(5):317–29. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2024-017546

20. Debono D, Greenfield D, Travaglia J, Long J, Black D, Johnson J, et al. Nurses’ workarounds in acute healthcare settings: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2013) 13(175):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-175

21. Halbesleben JR, Wakefield DS, Wakefield BJ. Work-arounds in health care settings: literature review and research agenda. Health Care Manage Rev. (2008) 33(1):2–12. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304495.95522.ca

22. McCord JL, Lippincott CR, Abreu E, Schmer C. A systematic review of nursing practice workarounds. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. (2022) 41(6):347–56. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000549

23. Alter S. Theory of workarounds. Commun Assoc Inf Syst. (2014) 34(1):1041–66. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.03455

24. Alper SJ, Karsh B-T. A systematic review of safety violations in industry. Accid Anal Prev. (2009) 41(4):739–54. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.03.013

25. Kweon Y-R, Lee S. Nurses’ electronic medical record workarounds in mental healthcare settings. Comput Inform Nurs. (2021) 39(10):592–603. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000762

26. Lee S, Lee M-S. Nurses’ electronic medical record workarounds in a tertiary teaching hospital. Comput Inform Nurs. (2021) 39(7):367–74. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000692

27. van der Veen W, Taxis K, Wouters H, Vermeulen H, Bates DW, van den Bemt PM, et al. Factors associated with workarounds in barcode-assisted medication administration in hospitals. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29(13-14):2239–50. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15217

28. Boonstra A, Jonker TL, van Offenbeek MA, Vos JF. Persisting workarounds in electronic health record system use: types, risks and benefits. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2021) 21(1):183. doi: 10.1186/s12911-021-01548-0

29. Debono D, Taylor N, Travaglia J, Carter D, Baysari M, Day R. Embedding electronic medication management systems into practice: identifying barriers to implementation using a theoretical approach. Sigma’s 30th International Nursing Research Congress; 25–29 July; Calgary, Canada (2019).

30. Morath JM, Turnbull JE. To Do No Harm: Ensuring Patient Safety in Health Care Organizations. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons (2005).

31. Varpio L, Schryer CF, Lingard L. Routine and adaptive expert strategies for resolving ICT mediated communication problems in the team setting. Med Educ. (2009) 43(7):680–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03395.x

32. Blijleven V, Hoxha F, Jaspers M. Workarounds in electronic health record systems and the revised sociotechnical electronic health record workaround analysis framework: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24(3):e33046. doi: 10.2196/33046

33. Fraczkowski D, Matson J, Lopez KD. Nurse workarounds in the electronic health record: an integrative review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2020) 27(7):1149–65. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa050

34. Zheng K, Ratwani RM, Adler-Milstein J. Studying workflow and workarounds in electronic health record–supported work to improve health system performance. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 172(11_Supplement):S116–S22. doi: 10.7326/M19-0871

35. Morrison B. The problem with workarounds is that they work: the persistence of resource shortages. J Oper Manag. (2015) 39:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2015.07.008

36. Tucker AL, Zheng S, Gardner JW, Bohn RE. When do workarounds help or hurt patient outcomes? The moderating role of operational failures. J Oper Manag. (2020) 66(1-2):67–90. doi: 10.1002/joom.1015

37. Blijleven V, Koelemeijer K, Wetzels M, Jaspers M. Workarounds emerging from electronic health record system usage: consequences for patient safety, effectiveness of care, and efficiency of care. JMIR Hum Fac. (2017) 4(4):e27. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.7978

38. Debono D, Taylor N, Lipworth W, Greenfield D, Travaglia J, Black D, et al. Applying the theoretical domains framework to identify barriers and targeted interventions to enhance nurses’ use of electronic medication management systems in two Australian hospitals. Implement Sci. (2017) 12(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0572-1

39. Watts EJ, Jackson J. Automated dispensing cabinets and nursing workarounds: how nurses silently adapt clinical work. Comput Inform Nurs. (2024) 42(10):691–3. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000001148

40. Koppel R, Wetterneck T, Telles JL, Karsh B-T. Workarounds to barcode medication administration systems: their occurrences, causes, and threats to patient safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2008) 15(4):408–23. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2616

41. Wilson RM, Michel P, Olsen S, Gibberd RW, Vincent C, El-Assady R, et al. Patient safety in developing countries: retrospective estimation of scale and nature of harm to patients in hospital. Br Med J. (2012) 344:e832. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e832

42. van der Veen W, van den Bemt PMLA, Wouters H, Bates DW, Twisk JWR, de Gier JJ, et al. Association between workarounds and medication administration errors in bar-code-assisted medication administration in hospitals. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2017) 25:385–92. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx077

43. Baker E, Connolly AJ. When IT Workarounds Threaten Workplace Safety. Health Information Technology and IS for Healthcare (2024). Available online at: https://ecis2024.eu/

44. Hollnagel E, Wears RL, Braithwaite J. From Safety-I to Safety-II: A White Paper. The Resilient Health Care Net: Published Simultaneously by the University of Southern Denmark, University of Florida, USA, and Macquarie University, Australia. 2015.

45. Berlinger N. Workarounds are routinely used by nurses—but are they ethical? Am J Nurs. (2017) 117(10):53–5. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000525875.82101.b7

46. Milton CL. Taking shortcuts and workarounds: is it ethical? Nurs Sci Q. (2024) 37(3):212–4. doi: 10.1177/08943184241246994

47. Farber DA, Gould J, Stephenson M. Workarounds in American Public Law. Harvard Public Law Working Paper No 23-35. 2023.

48. Debono D. Learning the rules of the game: how ‘good nurses’ negotiate workarounds (Doctoral thesis). University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia (2014).

49. Debono D, Braithwaite J. Workarounds in nursing practice in acute care: a case of a health care arms race? In: Wears RL, Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, editors. Resilient Health Care, Volume 2. Burlington, VT: CRC Press (2017). p. 53–68.

50. Debono D, Greenfield D, Black D, Braithwaite J. Achieving and Resisting Change: Workarounds Straddling and Widening Gaps in Health Care. The Reform of Health Care: Shaping, Adapting and Resisting Policy Developments. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK London (2012). p. 177–92.

51. Jun J, Ojemeni MM, Kalamani R, Tong J, Crecelius ML. Relationship between nurse burnout, patient and organizational outcomes: systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2021) 119:103933. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103933

52. Difaputra SA, Sawitri HSR. The effect of high-performance work system on intention to leave and safety workarounds: the role of burnout as mediation and mentoring and coping mechanism as moderator. Jurnal Indonesia Sosial Teknologi. (2024) 5(9):3491. doi: 10.59141/jist.v5i9.3312

53. Rathert C, Williams ES, Lawrence ER, Halbesleben JR. Emotional exhaustion and workarounds in acute care: cross sectional tests of a theoretical framework. Int J Nurs Stud. (2012) 49(8):969–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.02.011

54. Halbesleben JR. The role of exhaustion and workarounds in predicting occupational injuries: a cross-lagged panel study of health care professionals. J Occup Health Psychol. (2010) 15(1):1. doi: 10.1037/a0017634

55. Heron L, Bruk-Lee V. When empowered nurses are under stress: understanding the impact on attitudes and behaviours. Stress Health. (2020) 36(2):147–59. doi: 10.1002/smi.2905

56. Garcia CD, Abreu LC, Ramos JL, Castro CF, Smiderle FR, Santos JA, et al. Influence of burnout on patient safety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (B Aires). (2019) 55(9):553. doi: 10.3390/medicina55090553

57. Laschinger HKS, Leiter MP. The impact of nursing work environments on patient safety outcomes: the mediating role of burnout engagement. J Nurs Adm. (2006) 36(5):259–67. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200605000-00019

58. Mansour S, Tremblay D-G. How can we decrease burnout and safety workaround behaviors in health care organizations? The role of psychosocial safety climate. Pers Rev. (2019) 48(2):528–50. doi: 10.1108/PR-07-2017-0224

59. Bianchi M, Ghirotto L. Nurses’ perspectives on workarounds in clinical practice: a phenomenological analysis. J Clin Nurs. (2022) 31(19-20):2850–9. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16110

60. Gates PJ, Hardie R-A, Raban MZ, Li L, Westbrook JI. How effective are electronic medication systems in reducing medication error rates and associated harm among hospital inpatients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2020) 28(1):167–76. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa230

61. Westbrook JI, Li L, Woods A, Badgery-Parker T, Mumford V, Raban MZ. Stepped-wedge cluster RCT to assess the effects of an electronic medication system on medication administration errors. In: Bichel-Findlay J, Otero P, Scott P, Huesing E, editors. MEDINFO 2023—the Future is Accessible. Amsterdam: IOS Press (2024). p. 329–33.

62. Zheng WY, Lichtner V, Van Dort BA, Baysari MT. The impact of introducing automated dispensing cabinets, barcode medication administration, and closed-loop electronic medication management systems on work processes and safety of controlled medications in hospitals: a systematic review. Res Soc Admin Pharm. (2021) 17(5):832–41. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.08.001

63. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Electronic Medication Management Systems: A Guide to Safe Implementation. 3rd ed. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2019).

64. Star SL, Strauss A. Layers of silence, arenas of voice: the ecology of visible and invisible work. Comput Supported Co-op Work (CSCW). (1999) 8:9–30. doi: 10.1023/A:1008651105359

65. Taylor N, Mazariego C, Baffsky R, Liang S, Wolfenden L, Presseau J, et al. Advancing the speed and science of implementation using mixed-methods process mapping–best practice recommendations. Int J Qual Methods. (2025) 24:16094069251340908. doi: 10.1177/16094069251340908

66. Jennings BM, Sandelowski M, Mark B. The nurse’s medication day. Qual Health Res. (2011) 21(10):1441–51. doi: 10.1177/1049732311411927

68. Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. (2006) 27(2):237–46. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748

69. Rubin H, Rubin I. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (2005).

70. Eckmanns T, Bessert J, Behnke M, Gastmeier P, Rüden H. Compliance with antiseptic hand rub use in intensive care units the Hawthorne effect. Infect Cont Hosp Epidemiol. (2006) 27(9):931–4. doi: 10.1086/507294

71. Menzies I. A case-study in the functioning of social systems as a defence against anxiety: a report on a study of the nursing service of a general hospital. Hum Relat. (1960) 13:95–121. doi: 10.1177/001872676001300201

72. Westbrook JI, Li L, Raban MZ, Woods A, Koyama AK, Baysari MT, et al. Associations between double-checking and medication administration errors: a direct observational study of paediatric inpatients. BMJ Qual Saf. (2021) 30(4):320–30. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011473

73. Halligan D, Janes G, Conner M, Albutt A, Debono D, Carland J, et al. Identifying safety practices perceived as low value: an exploratory survey of healthcare staff in the United Kingdom and Australia. J Patient Saf. (2023) 19(2):143–50. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001091

74. Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. (2020) 15(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0960-9

75. Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC). Antimicrobial Restrictions in Medium to Large-sized Hospitals Fact Sheet. Sydney: CEC (2014).

76. Kreedi F, Brown M, Marsh L, Rogers K. Newly graduate registered Nurses’ experiences of transition to clinical practice: a systematic review. Am J Nurs. (2021) 9(3):94–105. doi: 10.12691/ajnr-9-3-4

77. Mellor PD, Gregoric C. New graduate registered nurses and the spectrum of comfort in clinical practice. J Contin Educ Nurs. (2019) 50(12):563–71. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20191115-08

78. Brown JA, Capper T, Hegney D, Donovan H, Williamson M, Calleja P, et al. Individual and environmental factors that influence longevity of newcomers to nursing and midwifery: a scoping review. JBI Evid Synth. (2024) 22(5):753–89. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-22-00367

79. Braithwaite J, Wears RL, Hollnagel E. Resilient Health Care, Volume 3: Reconciling Work-as-imagined and Work-as-done. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (2016).

80. Waqar H, Mahmood A, Ali M. High-Performance work systems and coping strategies in regulating burnout and safety workarounds in the healthcare sector. SAGE Open Nurs. (2023) 9:23779608231162058. doi: 10.1177/23779608231162058

81. Goff M, Hodgson D, Bailey S, Bresnen M, Elvey R, Checkland K. Ambiguous workarounds in policy piloting in the NHS: tensions, trade-offs and legacies of organisational change projects. New Technol Work Employ. (2021) 36(1):17–43. doi: 10.1111/ntwe.12190

82. Sittig DF, Singh H. A new socio-technical model for studying health information technology in complex adaptive healthcare systems. In: Patel VL, Kannampallil TG, Kaufman DR, editors. Cognitive Informatics for Biomedicine. Cham: Springer (2015). p. 59–80.

Keywords: workaround, electronic medication systems, medication, nurse, patient safety

Citation: Debono D, Greenfield D, Lipworth W, Carter DJ, Black D, Hinchcliff R, Carland JE and Braithwaite J (2025) “I know I shouldn't but …” the inevitable tension of using workarounds to be a “good nurse”. Front. Health Serv. 5:1579265. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2025.1579265

Received: 19 February 2025; Accepted: 8 July 2025;

Published: 29 July 2025.

Edited by:

Charles Vincent, University of Oxford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Davina Allen, Cardiff University, United KingdomDebbie Clark, Sheffield Hallam University, United Kingdom

Copyright: © 2025 Debono, Greenfield, Lipworth, Carter, Black, Hinchcliff, Carland and Braithwaite. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Deborah Debono, ZGVib3JhaC5kZWJvbm9AdXRzLmVkdS5hdQ==

Deborah Debono

Deborah Debono David Greenfield2

David Greenfield2 Wendy Lipworth

Wendy Lipworth David J. Carter

David J. Carter Reece Hinchcliff

Reece Hinchcliff Jane Ellen Carland

Jane Ellen Carland Jeffrey Braithwaite

Jeffrey Braithwaite