- 1Alberta Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Support Unit, Calgary/Edmonton, AB, Canada

- 2Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 3Department of Continuing Education, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 4Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 5Department of Pediatrics, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Background: Healthcare navigation services help individuals access timely and appropriate care within complex health systems, particularly those facing systemic and equity-related barriers. Understanding navigation experiences is essential to addressing service gaps and improving health outcomes. This study sought to examine the lived experiences of navigation in Alberta to identify inequities within existing programs and to provide recommendations for strengthening person-centered navigation within a learning health system framework.

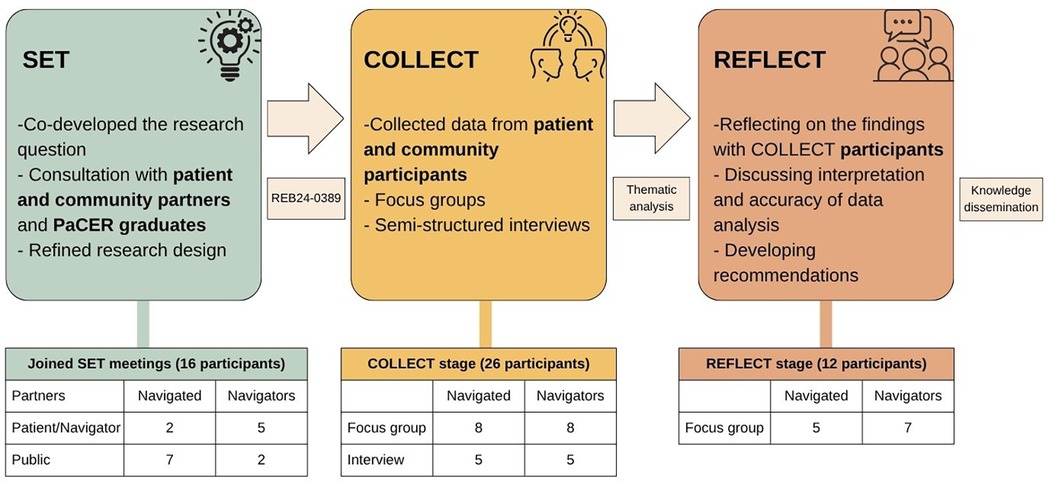

Materials: This was a qualitative, peer-to-peer, patient-oriented research study. The study design followed the Patient and Community Engagement Research process of SET-COLLECT-REFLECT. The SET phase engaged patient and public partners in discussions to co-design the research question and the study design. The COLLECT phase included focus groups and interviews with adult residents in Alberta who had been navigated (n = 13) and those who had experience as healthcare navigators (n = 13) in the Alberta healthcare system. The data were thematically analyzed, identifying key themes and subthemes. The REFLECT phase ran two focus groups with COLLECT participants for member checking. This approach yielded the recommendations.

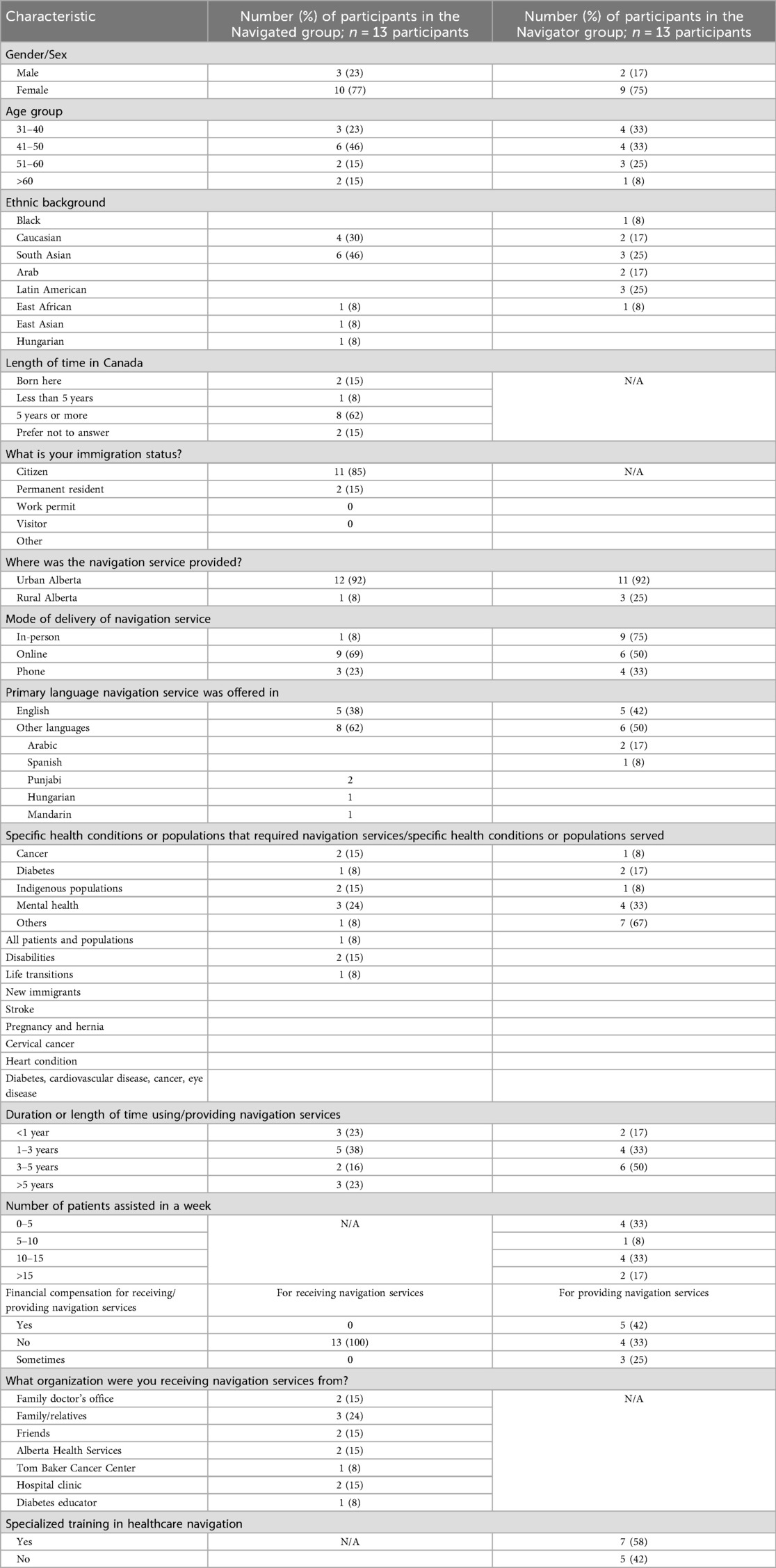

Results: Of the 26 participants, over 75% were women (77% of the Navigated group and 75% of the Navigator group) aged 41–50 years old. Half of those in the Navigator group had provided their service for more than 5 years and had received specialized training in healthcare navigation. The following themes were identified: (1) participants’ situations and circumstances, (2) navigation experiences, (3) perspectives, (4) need for healthcare navigators, (5) the navigator role, (6) current best practices and challenges, and (7) training and support. Five recommendations included expanding the scope and enhancing awareness of navigation programs with a personalized approach and embedded evaluation and developing and formalizing navigation training programs.

Conclusion: This study identified gaps and opportunities in healthcare navigation programs from both navigator and navigated perspectives. The findings provide patient-centered recommendations to strengthen navigation services and their integration into Alberta's learning health system that can enhance equitable access, healthcare experiences, and outcomes.

Introduction

Healthcare systems have grown increasingly complex due to specialization and expanding care pathways, creating significant challenges for individuals attempting to navigate care on their own (1). These challenges are particularly pronounced for people living with new diagnoses, those living with chronic and complex conditions, and those facing systemic barriers rooted in structural and social inequities. Such inequities, including those related to income, culture, language, geography, and disability, limit equitable access to timely, appropriate, and person-centered care. In response, various navigation supports and services have been developed, including in Alberta, Canada, the focus of this study.

The concept of patient navigation was first introduced in 1990 by Dr. Harold Freeman to reduce inequities in cancer care access among racialized and marginalized populations in Harlem, USA (2). Since then, navigation has evolved into a global strategy addressing a wide range of conditions and needs (3). In Alberta, navigation programs currently serve diverse populations across cancer care, diabetes, mental health, disability, life transitions, and newcomer support. However, the varied definitions and applications of “patient navigation” have led to confusion, hindering efforts to evaluate their effectiveness, improve equity in service delivery, and standardize navigator training.

More recently, the term “healthcare navigation” has been adopted to describe a broader spectrum of services, ranging from community-based wellness supports to specialized disease care. Reid et al. delineate between lay navigators (e.g., peers, community health workers, and informal caregivers) who share lived experiences with those they support, and professional patient navigators (e.g., nurse navigators, care coordinators, and diabetes educators) with clinical expertise (4). Both play important roles in addressing inequities by bridging gaps in access, fostering trust, and supporting culturally responsive, person-centered care.

In Alberta, navigation services span diverse aspects of healthcare such as cancer, diabetes, mental health, disability, life transitions, and newcomer support. Understanding healthcare navigation through a health equity lens is essential to identifying barriers, addressing gaps, and advancing system-level changes that promote fairness in access and outcomes (3, 5). This study sought to examine the lived experiences of healthcare navigation in Alberta to identify inequities within existing programs and provide recommendations for strengthening person-centered navigation within a learning health system framework.

Materials and methods

To address the objective, this peer-to-peer patient-oriented qualitative study was conducted. People with lived experience were meaningfully engaged throughout the design, development, and dissemination phases of the research process to inform more person-centered healthcare policy and practice.

A literature review and an environmental scan of existing healthcare navigation programs in Alberta provided the evidence base for this study (described elsewhere). The methodology used a participatory action research approach (6) based on the Patient and Community Engagement Research (PaCER) process that includes three phases: SET, COLLECT, and REFLECT (7–9).

The PaCER program

PaCER is a 1-year experiential-based participatory research training program supervised by the Alberta Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (AbSPORU) SUPPORT Unit, Patient Engagement Team (10), in partnership with the Continuing Education program at the University of Calgary (7–9).

The study was conducted during an 80-hour research project as part of the PaCER program by a team of PaCER students that comprised individuals from diverse ethno-cultural, academic, professional, and research backgrounds and with distinct lived experiences of being navigated and/or as navigators in the Alberta healthcare system. These students were fluent in 10 languages, including Arabic, Azerbaijani, Dari, Hindi, Mandarin, Pashto, Punjabi, Russian, Spanish, and Urdu. The students were divided into two groups of six members each, namely, the Navigated and Navigator groups, to gain a focused understanding of the unique experiences and insights from each of the two perspectives. These were then brought together to offer a more comprehensive and holistic overview of the current contexts of healthcare navigation in Alberta.

The PaCER process (Figure 1) consisted of the following three phases:

1. SET: Both the Navigator and Navigated groups held discussions with those with lived experience of healthcare navigation and public partners to refine the research question, research design, and focus group and interview question guides. The research protocol was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB24-0389).

2. COLLECT: Participant recruitment for the focus groups and interviews started in April 2024. Participants were adults, residents of Alberta, and with experience of being navigated in the Alberta healthcare system or had experience navigating people in the Alberta healthcare system. Recruitment was conducted through purposive sampling with convenience selection of participants. The Navigator and Navigated groups recruited participants for their focus groups and interviews using unique recruitment posters (see Supplementary Material). Recruitment posters were shared with the organizations identified through the environmental scan of healthcare navigation organizations in Alberta and through the team members’ community connections, the Albertans4HealthResearch.ca network (11), and community-based social media platforms, including chronic disease support groups. This supported diversity in socioeconomic, cultural, and navigation experiences. In addition, to be inclusive, the participants were asked preferences regarding languages, delivery mode (online or in person), and scheduling of focus groups or interviews. Data from the COLLECT stage were thematically analyzed, and key recommendations were synthesized based on developed themes. Data saturation in this study was determined when no new themes emerged from the data analysis, indicating that sufficient information had been collected to address the research objectives.

3. REFLECT: The COLLECT focus group and interview participants were invited to the REFLECT focus groups for member checking (12) to ensure accuracy of interpretation and findings. Recommendations were renewed based on the REFLECT participants’ comments and suggestions.

Data collection and analysis

All the participants were asked to complete a sociodemographic electronic Qualtrics survey that included questions about characteristics unique to each group, e.g., number of patients and hours offering navigation services per week for the Navigator group and number of years living in Canada for the Navigated group. All the participants were offered a prepaid gift card ($25 CAD) in appreciation for their participation in each of the COLLECT and REFLECT focus groups and interviews they joined.

Interpretation services were offered in the 10 different languages previously mentioned to the focus groups and interview participants. All the focus groups and interviews were held online via the Zoom platform. All the participants provided oral or electronic consent to participate using a REB-approved informed consent form. The participants were asked for permission to video record the focus groups or interviews for notetaking purposes only. The focus groups were 2 h long. At least three team members conducted the focus groups, with one facilitating the session, and the other two managing the chat, taking notes, and supporting participants with sign-on or Zoom issues. Participants who were unable or uncomfortable joining the focus groups shared their experiences in a 1-h online semi-structured interview. Two team members conducted the interviews—one asked the questions and the other took detailed notes. Participation of multiple team members at the focus groups and interviews was a priority to allow diverse points of view and limit personal bias. The focus groups and interview question guides contained the same questions. (See Supplementary Table 5 for the Navigated Focus Group Question Guide and Supplementary Table 6 for the Navigator Focus Group Question Guide).

Zoom transcripts of the focus groups and interviews were de-identified, cleaned and sorted, and arranged into Excel files. The data were then analyzed using the six-step thematic analysis approach as described by Braun and Clarke (13), including (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) writing the report. The transcripts were collectively analyzed. These discussions encouraged critical reflection on each member's interpretations and provided opportunities to challenge underlying assumptions and preconceptions. After each member individually coded the first focus group, each team created a code book that included a brief description of the codes as they related to the context of the study. These code books were then applied to the remaining focus group and interview data, adding additional codes as they emerged. Codes were consolidated into categories and then organized into themes and key recommendations.

Results

Demographics

Table 1 depicts the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. Of the 26 participants, 13 were people with lived experience of being navigated in the Alberta healthcare system, and the other 13 were healthcare navigators. The navigators had experience in serving in multiple areas (rural and urban) and covering a wide range of health conditions, including domestic violence, and all spoke at least one additional language to English. The navigated participants represented a wide range of socioethnic backgrounds, languages, and health conditions.

The majority of the participants in both groups were female (77% of the Navigated group and 75% of the Navigator group). The largest age group among the participants in the Navigated group was 41–50 years (46%), while those in the Navigator group were distributed across 41–50 years (33%) and 31–40 years (33%). The majority of the navigation services were provided and received in Alberta's urban settings (92% in both groups).

The participants in the Navigated group most often accessed services online (69%) or by phone (23%), whereas those in the Navigator group primarily delivered services in person (75%) or online (50%). A substantial proportion of the participants spoke a language other than English (62% of the Navigated group and 50% of the Navigator group). While all participants in the Navigator group were fluent in English, two participants in the Navigated group who spoke Punjabi reported limited English proficiency.

Half of the participants in the Navigator group (50%) had more than 5 years of experience, while 38% of the participants in the Navigated group had received navigation services for 1–3 years. All participants in the Navigated group accessed services free of charge, and a majority of those in the Navigator group (42%) received compensation for their work. In addition, 58% of the participants in the Navigator group reported receiving specialized training in healthcare navigation.

Thematic analysis

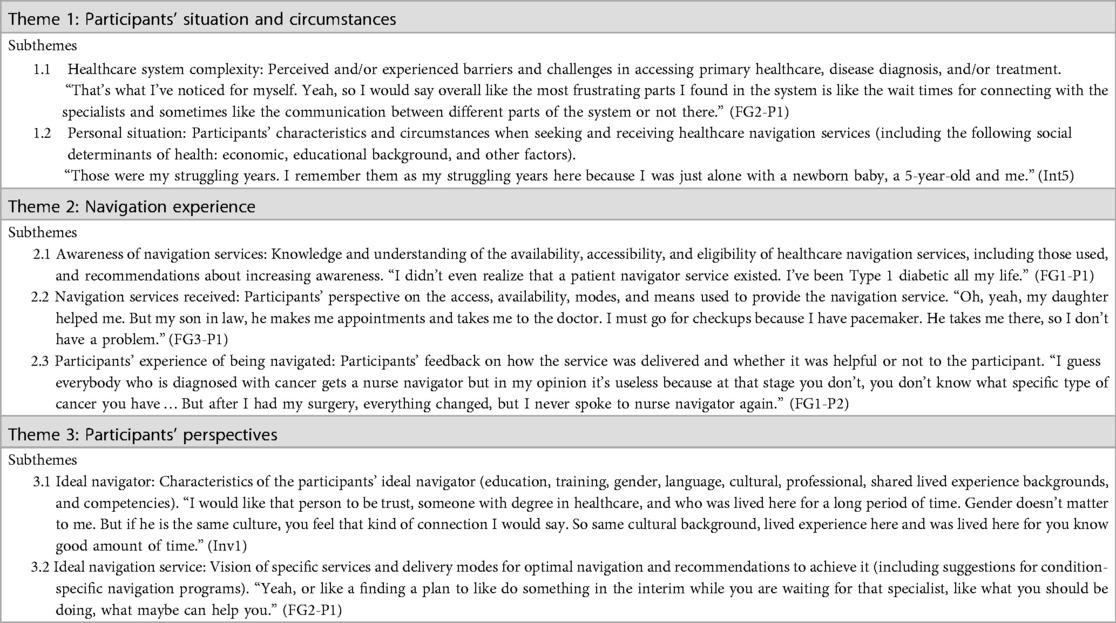

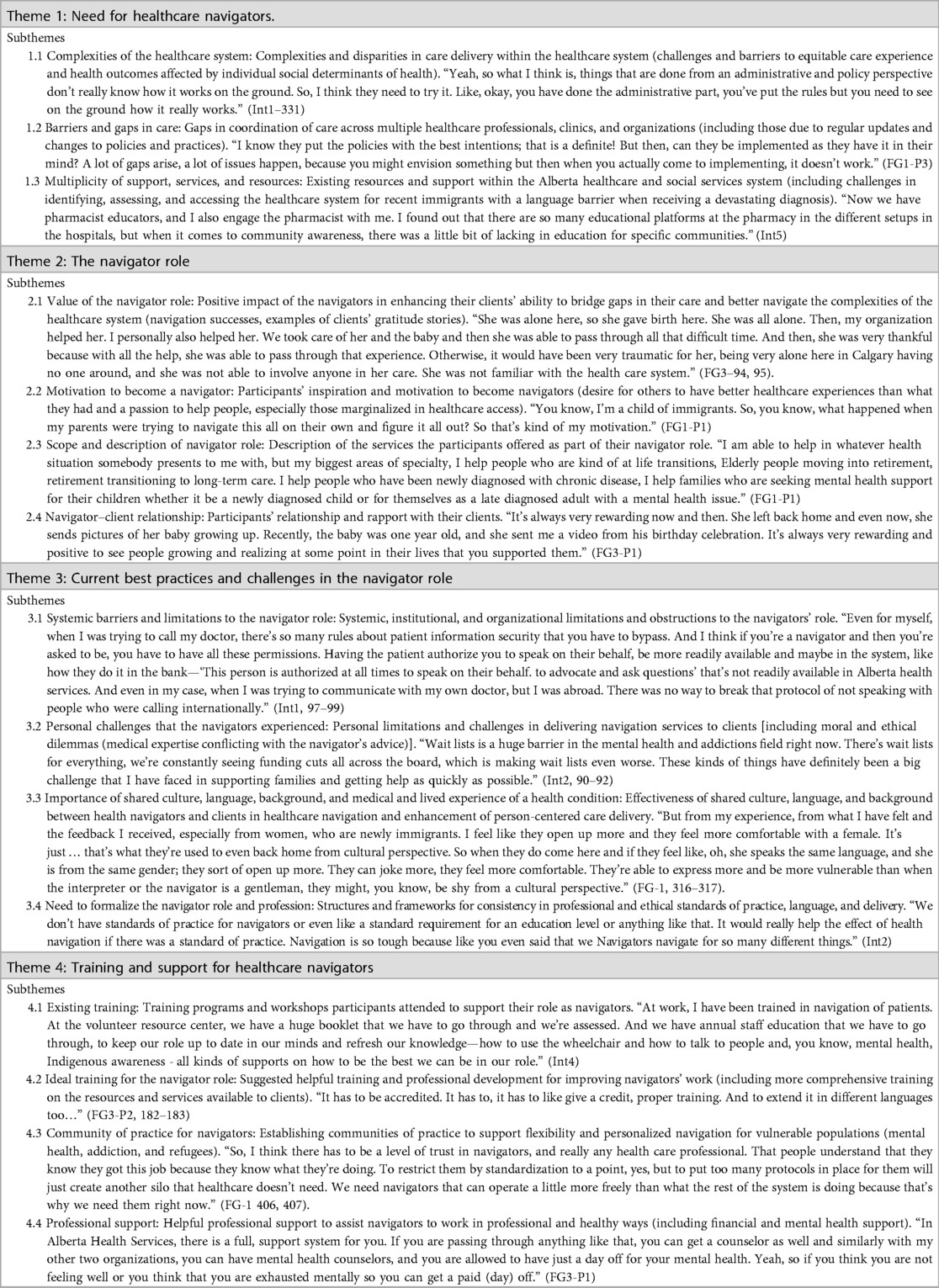

The themes identified by both groups reflected the complexity of the healthcare system and shed light on gaps in healthcare navigation services and navigator training programs. The themes from the Navigated group reflected the participants’ unique situations and circumstances, and their perspectives about being navigated in the Alberta healthcare system. The participants in the Navigated group described improved access to care, care experiences, and health outcomes because of their navigation. The themes from the Navigator group centered on the need for healthcare navigators, the navigator role, current best practices, challenges in working as a healthcare navigator, and insights and recommendations to improve training and support for healthcare navigators. Tables 2, 3 outline the themes, subthemes, and exemplar quotes.

The Navigated group developed three themes: (1) participants’ situations and circumstances, (2) navigation experiences, and (3) perspectives.

1. Participant's situations and circumstances. The context in which navigation happened.

“… well, I came from New Zealand, so it's similar health system …. Yeah, but I also had an issue with. … I, didn’t, wasn’t originally recognizing my, low blood sugars and I actually collapsed on one of the train stations downtown.” (FGD2-P2).

2. Navigation experiences. The participants’ unique perspectives and insights on their navigation experience(s).

“Sometimes the needed language support. And having someone there who could speak on their behalf. Was helpful or like help them communicate or understand what they were being told by the medical professionals about like the kind of care that they needed.” (FGD2-P1).

3. Participant's perspectives. The participant's point of view about an ideal navigator and ideal navigation services.

“Yeah. I feel like being a male or female is not important. So who has some knowledge, a person who can speak, our own language, participant one is saying, so language is very important and who can understand you can put themselves at in your position.” (FG-P1).

The Navigator group developed the following four themes:

1. The need for healthcare navigators. Social, systemic, and structural factors that define the need for healthcare navigators in Alberta.

“In a lot of cases, once the treatment is completed, there isn’t necessarily a follow up, you know, in terms of, dialog with the patient. Lot of cases they felt feel or they feel as if they are left. And nobody nobody's following them.” (FG2-P1).

2. The navigator role. Participants’ motivations for becoming a navigator.

“You know, I’m a child of immigrants. So, you know, what happened when my parents were trying to navigate this all on their own and figure it all out? So that's kind of my motivation.” (FG1-P1).

3. Current best practices and challenges. Effective strategies, gaps, and possible improvements in existing navigation service delivery in Alberta.

“We don’t have standards of practice for navigators or even like a standard requirement for an education level or anything like that. It would really help the effect of health navigation if there was a standard of practice. Navigation is so tough because like you even said that we Navigators navigate for so many different things.” (Int2).

4. Training and support. Existing and proposed training programs, workshops, and professional development enhancing navigators’ work.

“It has to be accredited. It has to, it has to like give a credit, proper training. And to extend it in different languages too…” (FG3-P2).

Recommendations

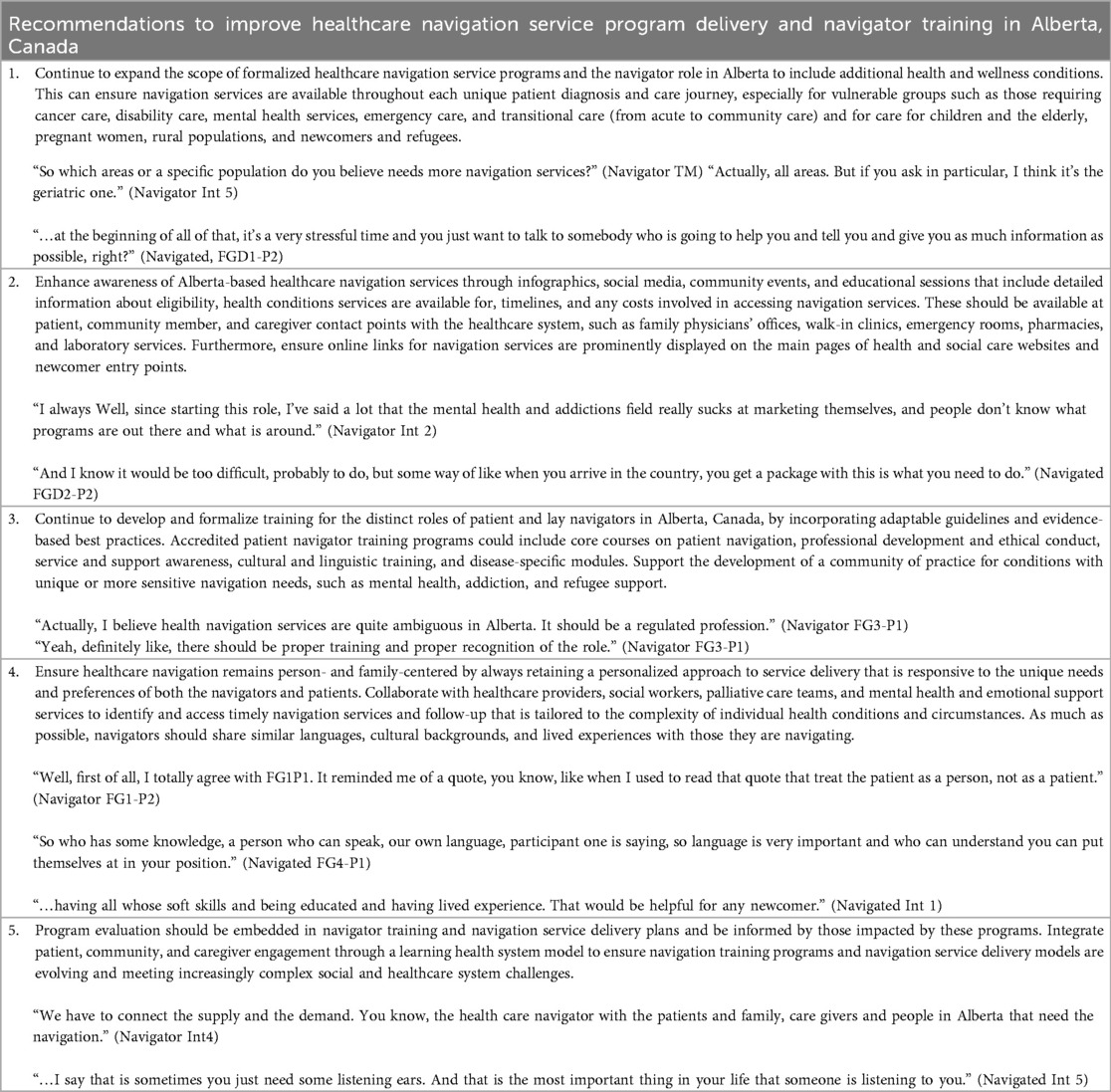

The recommendations were derived from the data collected during the COLLECT and REFLECT phases. Five recommendations included expanding the scope and enhancing awareness of navigation programs, integrating more person-centered approaches, and embedding evaluation into the development and delivery of service and training programs. All the participants proposed more navigation service advocacy and flexible access, especially for vulnerable populations seeking timely mental health support. Including specialized interpretation and translation services to newcomer and immigrant populations was also deemed crucial, reflecting that English was a second language for the majority of the participants in both the Navigated and Navigator groups. The participants also emphasized the need for adequate financial compensation and mental health services for navigators to ensure ethical and sustainable support to significantly enhance navigation effectiveness and outcomes for both navigators and their clients.

The participants in the Navigator group described how often the lack of formal recognition and systemic limitations affected the scope of support they could provide to their clients. The navigators suggested formalizing the navigator role with flexible guidelines and best practices, while maintaining flexibility for personalized service delivery tailored to the unique needs of each client. As 58% of the participants in the Navigator group reported having a professional training in healthcare navigation, they identified a need for more comprehensive and professional training that covers both broad professional and ethics training for the navigator role and training specific to the health conditions and populations their clients represent.

The participants in the Navigated group highlighted the need to improve awareness and communication about navigation programs. They agreed that primary care clinics and emergency departments are crucial entry points to the healthcare system, making them ideal sources for accessing navigation information. Considering that the majority of the participants in the Navigated group used online navigation services, they also suggested improving the user interface of the Alberta Health Services website to a more patient-centered design, enabling the public to better access and navigate the extensive information available. In addition, immigration and refugee service providers in Alberta, along with immigration websites and entry points to Alberta, such as airports, were highlighted as strategic locations for disseminating information on accessing healthcare navigation services. The participants in the Navigated group emphasized the need to develop peer navigator services that acknowledge the unique role that peer navigators play by validating their feelings and sharing their experience in navigating certain conditions.

Furthermore, the participants highlighted the necessity of professional support for navigators, advocating for improved financial compensation (only 42% of the participants in the Navigator group were financially compensated for their services) and mental health services to ensure that navigators can fulfill their roles ethically and sustainably. Addressing these needs could significantly enhance the effectiveness of navigation services, ultimately leading to better outcomes for both navigators and the clients they serve. Finally, continuous evaluation of healthcare navigation services and training programs is integral to allow learning health systems (14) to adapt to evolving healthcare needs and ensure effective service delivery. Table 4 outlines the recommendations.

Discussion

This study offers practical person-centered recommendations to improve existing healthcare navigation programs. Integrating these recommendations into learning health system initiatives in Alberta will support more equitable access to healthcare services and treatments and improve public and patient healthcare experiences and health outcomes for all populations.

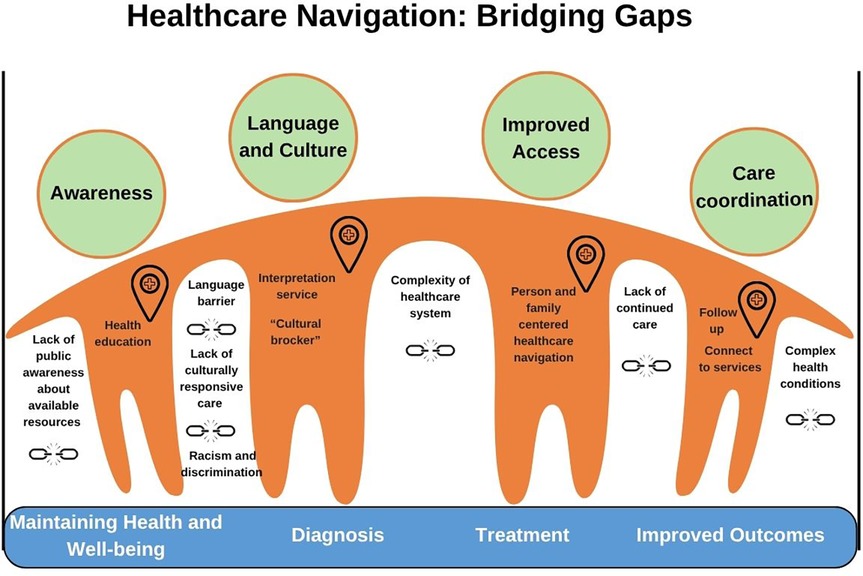

This study confirmed that healthcare navigation is crucial for addressing gaps and barriers in accessing healthcare services (Figure 2), thereby improving one’s healthcare experience and health outcomes, especially for those facing systemic and other healthcare equity-denying barriers (3, 15–19). Several barriers to accessing appropriate and timely care, including the complexities of the healthcare system, can create gaps in an individual's healthcare journey, potentially causing them to fall through the cracks and negatively impacting their health outcomes. Challenges such as long wait times for specialist appointments, convoluted referral processes involving multiple healthcare professionals, and transportation issues are notable examples. Language barriers and a lack of culturally responsive care further complicate access to necessary services, particularly for newcomers and marginalized populations (20–22).

Participants shared that even when multiple resources, support, and services are available, there is often a general lack of public awareness about these resources, affecting not only newcomers who face language and cultural barriers but also all potential users of healthcare systems and healthcare providers. In these cases, the role of navigators, whose primary aim is to identify and coordinate resources, care, and treatment and to ease the client's journey through the healthcare system, becomes invaluable. This emphasizes the importance of navigation support, particularly for individuals facing new or complex health issues and those in socially disadvantaged groups (3, 15–23).

A key finding is that, regardless of their specific role, navigators serve as crucial links between their clients and the healthcare system, helping to make the healthcare journey less daunting and promoting positive, more inclusive health-seeking behaviors. We confirmed that the scope of the navigator role is broad and multifaceted, varying based on the specific conditions being addressed and the type of navigation services offered (4, 19, 22–25). Informal navigators may assist with tasks such as accompanying individuals to doctors' appointments or providing interpretation and translation services, while professional navigators may offer specialized support for specific conditions, such as pediatric care coordination, cancer care, dementia, or diabetes. This diversity in navigator roles highlights their contribution to overcoming the barriers and complexities of the healthcare system (4, 22, 24, 25).

Many of the participants in the Navigator group shared that their motivation to become navigators stemmed from an intrinsic passion for helping others, especially those who have become discouraged with the complexities of the healthcare system. In such instances, the relatively informal yet respectful relationship between the navigator and client—built on mutual trust, empathy, and cultural sensitivity—enables the navigator to act as an advocate, educator, mediator, supporter, and even a friend, helping clients to “connect the dots” and access the care they need. The findings of this study align with a study by Phillips et al. (26) that explored navigators’ reflections on the navigator-patient relationship, describing the navigator role as providing motivational support throughout the patient's clinical care (26–28).

Navigators play an important role in addressing additional issues of racism and discrimination within the healthcare system by reducing barriers that prevent access to quality healthcare among immigrant, marginalized, and low-income populations (24). One participant shared an experience of misdiagnosis in an urban Alberta hospital that she felt was the result of discrimination based on her being a member of a visible minority group, highlighting systemic issues that resulted in a stroke in her case. The same participant shared numerous instances of being denied the chance to accompany her mother as an interpreter when the used phone language line was unsuccessful due to cultural misunderstanding or missed situational details. These situations underscore how healthcare navigators can help avoid such problems, especially for socially disadvantaged groups.

The navigators highlighted the importance of incorporating formal interpretation and translation training into the navigator role, which would greatly improve the healthcare experience for clients who require these services. Language and communication barriers, as highlighted in one participant's story, pose substantial challenges to healthcare delivery, especially among newcomers in Alberta. Existing language tools, such as language lines, often fall short in addressing these barriers, as they may not account for the sociocultural complexities of clients, including dialects, hierarchical structures, and gender dynamics.

An important finding was the personal connection between the navigators and their clients, noting that this relationship can significantly enhance the client's healthcare experience. The participants in the Navigated group also highlighted the value of sharing one or more similar characteristics with their navigators, whether it was language, culture, or a similar health condition. They confirmed that when trying to understand and access healthcare services and resources after a diagnosis, it was important to them that their navigator had a strong knowledge of the healthcare system, experience related to their health condition, and familiarity with the pathways available for treatment. Even with minimal interventions, the majority of the participants in the Navigated group expressed satisfaction with the services they received from their navigator, noting that the latter’s services were instrumental in improving their overall health outcomes, including mental health.

This study highlights the vital role healthcare navigation has in bridging the gaps between patients and community members and the complexities of healthcare systems, and further emphasizes how shared culture, language, and lived experience can significantly enhance the quality of navigation services, facilitating the provision of effective person- and family-centered care. The scope of navigation services in Alberta is constantly expanding, with more specialized roles emerging. This study also reemphasizes the need for ongoing development and enhancement of navigation services and navigator training in Alberta. Evidence from our literature review (available elsewhere) identified key reviews describing several programs tailored to the development of navigation services for specific health conditions (3, 16–19, 21).

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the strong connections our team members had with their respective communities, which proved instrumental in achieving more inclusive and representative participant recruitment. This was especially important when we faced hurdles such as difficulties recruiting through healthcare and community organizations and a setback caused by social media spammers that led to the closure of our Qualtrics survey. The deep-rooted community ties of our group members allowed us to navigate these obstacles and successfully achieve our recruitment goals. Furthermore, the linguistic and cultural diversity within our team also significantly enhanced the data collection and analysis process. Team members fluent in Punjabi provided interpretation during one focus group, enabling seamless communication and interaction with the participants. A comprehensive translation of the focus group transcript allowed us to capture emotional nuances and details of the participants’ stories, resulting in richer and more accurate data for our analysis.

The majority of the participants were from Calgary, with some from Edmonton. This study had limited representation from rural Alberta, with only one participant in the Navigated group and three in the Navigator group from that region. The member-checking focus groups (REFLECT) validated the findings, adding to the robust study design (12).

This study encountered several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. A significant limitation was the tight timeline to complete participant recruitment at the COLLECT stage (1.5 months). Some organizations required lengthy administrative procedures to obtain permission to recruit participants, which limited the number of participants available to recruit. Organizational policies surrounding confidentiality and privacy were also major obstacles to recruiting participants in the Navigator group. This study was limited by the overrepresentation of female participants, individuals aged 31–50 years, and those residing in urban settings. Women may be more engaged both as users and providers of navigation services due to their greater involvement in healthcare and caregiving, while recruitment pathways may have disproportionately reached this group. Similarly, adults in midlife may be more visible in navigation roles, whereas the perspectives of younger and older populations remain underrepresented. Finally, the predominance of urban participants limits insights into the distinct navigation challenges faced by rural and remote populations. Together, these factors constrain the generalizability of findings and highlight the need for further research with more diverse participant groups.

Conclusion

The study highlights the need for ongoing efforts to formalize and expand healthcare navigation services in Alberta with a focus on personalizing care to support vulnerable groups, such as those requiring cancer care, disability care, and mental health services. This can best be achieved through the integration of patient engagement into learning health systems. Learning health systems should provide a culturally sensitive, person-centered healthcare navigation experience, broaden the scope and availability of navigation services across various health conditions, and increase public awareness through targeted strategies and outreach. Continuous evaluation of these programs, using a learning health system approach, is vital to adapt to evolving healthcare needs and ensure effective patient-centered service delivery. The findings of this study may be considered relevant to a broader audience in Canada and globally, as they address current issues, such as gaps and best practices in navigating complex healthcare systems, and provide an exploration of navigation services from the perspective of immigrants, which is a particularly relevant topic given ongoing global migration (29, 30). This study provides a framework for larger, long-term research aiming for a more comprehensive scan of navigation programs in Alberta, including rural parts of the province, that could lead to the creation of a Directory of Healthcare Navigation Programs available to Albertans. Further research, including broader geographical representation of Albertans with diverse lived experiences, will be beneficial to inform the ongoing research on healthcare navigation delivery and training.

Data availability statement

Due to privacy and confidentiality considerations, we are unable to share the raw data. Nevertheless, we are committed to transparency and will consider sharing anonymized data upon reasonable request and in accordance with data sharing policies.

Ethics statement

This study involving humans was approved by the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB24-0389). This study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing – review & editing. IN: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration. LZ-C: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization. SA: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. CE: Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation. SP: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation. BF: Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation. MK: Investigation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. HK: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization. NM: Formal analysis, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Investigation. UO: Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. SZ: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology. XS: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. KN: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PF: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MS: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Alberta SPOR SUPPORT Unit (AbSPORU), which is co-funded by the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research program of the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR), Alberta Innovates, and the University Hospital Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the contributions of the participants and the funding agency.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2025.1642188/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Manns BJ, Hastings S, Marchildon G, Noseworthy T. Health system structure and its influence on outcomes: the Canadian experience. Healthc Manag Forum. (2024) 37(5):340–50. doi: 10.1177/08404704241248559

2. Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. (2011) 117(S15):3537–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262

3. Chan RJ, Milch VE, Crawford-Williams F, Agbejule OA, Joseph R, Johal J, et al. Patient navigation across the cancer care continuum: an overview of systematic reviews and emerging literature. CA Cancer J Clin. (2023) 73(6):565–89. doi: 10.3322/caac.21788

4. Reid AE, Doucet S, Luke A. Exploring the role of lay and professional patient navigators in Canada. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2020) 25(4):229–37. doi: 10.1177/1355819620911679

5. Tang KL, Kelly J, Sharma N, Ghali WA. Patient navigation programs in Alberta, Canada: an environmental scan. CMAJ Open. (2021) 9(3):E841–7. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20210004

6. Vaughn LM, Jacquez F. Participatory research methods—choice points in the research process. J Particip Res Methods. (2020) 1(1). doi: 10.35844/001c.13244

7. University of Calgary. Patient and Community Engagement Research (PaCER) | Home (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.ucalgary.ca/patient-community-engagement-research (Accessed September 4, 2025).

8. Shklarov S, Marshall DA, Wasylak T, Marlett NJ. Part of the team’: mapping the outcomes of training patients for new roles in health research and planning. Health Expect. (2017) 20(6):1428–36. doi: 10.1111/hex.12591

9. Marlett N, Shklarov S, Marshall D, Santana MJ, Wasylak T. Building new roles and relationships in research: a model of patient engagement research. Qual Life Res. (2014) 24(5):1057–67. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0845-y

10. Alberta Strategy for Patient Oriented Research SUPPORT Unit (AbSPORU). Patient Engagement—Alberta Strategy for Patient Oriented Research SUPPORT Unit (AbSPORU) (2025). Available online at: https://absporu.ca/patient-engagement/ (Accessed September 4, 2025).

11. Betterimpact.com. Albertans4HealthResearch.ca (2025). Available online at: https://app.betterimpact.com/PublicOrganization/25809ea0-7311-40db-bfac-aaa0e28ba518/1 (Accessed September 4, 2025).

12. McKim C. Meaningful member-checking: a structured approach to member-checking. Am J Qual Res. (2023) 7(2):41–52. Available online at: https://www.ajqr.org/download/meaningful-member-checking-a-structured-approach-to-member-checking-12973.pdf

13. Braun V, Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int J Transgend Health. (2022) 24(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

14. Lee-Foon N, Smith M, Greene SM, Kuluski K, Reid RJ. Positioning patients to partner: exploring ways to better integrate patient involvement in the learning health systems. Res Involv Engagem. (2023) 9(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s40900-023-00459-w

15. Tang KL, Ghali WA. Patient navigation—exploring the undefined. JAMA Health Forum. (2021) 2(11):e213706. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3706

16. McBrien KA, Ivers N, Barnieh L, Bailey JJ, Lorenzetti DL, Nicholas D, et al. Patient navigators for people with chronic disease: a systematic review. PLoS One. (2018) 13(2):e0191980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191980

17. Anthonisen G, Luke A, MacNeill L, MacNeill AL, Goudreau A, Doucet S. Patient navigation programs for people with dementia, their caregivers, and members of the care team: a scoping review. JBI Evid Synth. (2023) 21(2):281–325. doi: 10.11124/jbies-22-00024

18. Peart A, Lewis V, Brown T, Russell G. Patient navigators facilitating access to primary care: a scoping review. BMJ Open. (2018) 8(3):e019252. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019252

19. Katerenchuk J, Salas AS. An integrative review on the oncology nurse navigator role in the Canadian context. Can Oncol Nurs J. (2023) 33(4):385–99. doi: 10.5737/23688076334385

20. Urquhart R, Kendell C, Pfaff K, Stajduhar K, Patrick L, Dujela C, et al. How do navigation programs address the needs of those living in the community with advanced, life-limiting illness? A realist evaluation of programs in Canada. BMC Palliat Care. (2023) 22(1):179. doi: 10.1186/s12904-023-01304-3

21. Watson L, Anstruther SM, Link C, Qi S, Burrows K, Lack M, et al. Enhancing cancer patient navigation: lessons from an evaluation of navigation services in Alberta, Canada. Curr Oncol. (2025) 32(5):287. doi: 10.3390/curroncol32050287

22. Meade CD, Wells KJ, Arevalo M, Calcano ER, Rivera M, Sarmiento Y, et al. Lay navigator model for impacting cancer health disparities. J Cancer Educ. (2014) 29(3):449–57. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0640-z

23. Leong M, Campbell D, Ronksley P, Garcia-Jorda D, Ludlow NC, McBrien K. The role of community health navigators in the creation of plans to support patients with chronic conditions. PubMed Central. (2023) 21 (Suppl 1):4372. doi: 10.1370/afm.21.s1.4372

24. Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, Jones LA. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. (2011) 117(S15):3541–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26264

25. UNB. Implementing a patient navigation program for people with dementia 2 (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.unb.ca/cric/_assets/documents/implementation-resource-toolkit.pdf (Accessed September 4, 2025).

26. Phillips S, Nonzee N, Tom L, Murphy K, Hajjar N, Bularzik C, et al. Patient navigators’ reflections on the navigator-patient relationship. J Cancer Educ. (2014) 29(2):337–44. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0612-3

27. Santos Salas A, Watanabe SM, Sinnarajah A, Bassah N, Huang F, Turner J, et al. Increasing access to palliative care for patients with advanced cancer of African and Latin American descent: a patient-oriented community-based study protocol. BMC Palliat Care. (2023) 22(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12904-023-01323-0

28. Bruce M, Lopatina E, Hodge J, Moffat K, Khan S, Pyle P, et al. Understanding the chronic pain journey and coping strategies that patients use to manage their chronic pain: a qualitative, patient-led, Canadian study. BMJ Open. (2023) 13(7):e072048. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-072048

29. Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: the challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. (2001) 323(7313):625–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625

Keywords: person-centered care, patient navigation, learning health systems, patient engagement, peer-to-peer research, healthcare navigation

Citation: Aghabayli F, Nielssen I, Zapata-Cardona LA, Ahmed S, Ezemenahi C, Parmar S, Fahimi B, Khan MH, Khan HH, Mendez Muniz ND, Osigwe U, Zaidi S, Shi X, Nabil K, Fairie P and Santana MJ (2025) From experience to a learning health system: peer-to-peer perspectives and implications for healthcare navigation in Alberta, Canada. Front. Health Serv. 5:1642188. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2025.1642188

Received: 6 June 2025; Accepted: 19 September 2025;

Published: 17 October 2025.

Edited by:

Júlio Belo Fernandes, Egas Moniz Center for Interdisciplinary Research (CiiEM), PortugalReviewed by:

Laith Daradkeh, Hamad Medical Corporation, QatarShuo Liu, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (CAMS), China

Copyright: © 2025 Aghabayli, Nielssen, Zapata-Cardona, Ahmed, Ezemenahi, Parmar, Fahimi, Khan, Khan, Mendez Muniz, Osigwe, Zaidi, Shi, Nabil, Fairie and Santana. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fakhriyya Aghabayli, YWZha2hyaXl5YUBrZWVtYWlsLm1l

Fakhriyya Aghabayli

Fakhriyya Aghabayli Ingrid Nielssen

Ingrid Nielssen Luz Aida Zapata-Cardona1

Luz Aida Zapata-Cardona1 Chisom Ezemenahi

Chisom Ezemenahi Shaziah Zaidi

Shaziah Zaidi Xingye Shi

Xingye Shi Kiran Nabil

Kiran Nabil Paul Fairie

Paul Fairie Maria Jose Santana

Maria Jose Santana