Abstract

Real-World Evidence (RWE) is a critical enabler of personalized medicine (PM), offering granular insights into how interventions perform across diverse, real-life populations. This manuscript, grounded in over 30 years of health data science and regulatory experience, explores the evolving role of RWE in transforming healthcare delivery—from regulatory frameworks and policy alignment to artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled patient stratification. Through real-world case examples in oncology, ophthalmology, and dermatology, the article illustrates how digital tools and data integration can enhance patient-centred care. Each vignette concludes with an “adoption path” outlining data requirements, minimal IT changes, training, and payer-relevant endpoints. The discussion critically examines risks—such as bias, opacity in algorithms, and lack of harmonization—and translates them into a pre-deployment audit checklist and an equity checklist for subgroup performance and representativeness audits. To guide global regulatory practice, a “regulatory pragmatics” checklist is proposed, covering data quality, traceability, validation, transparency, and patient voice, including patient-generated health data (PGHD). Building on the Healthcare 5.0 vision, the manuscript aligns RWE with human-centric, sustainable, and resilient pillars, highlighting IoT wearables, environmental sensors, and continuous lifestyle data streams. Policy and implementation recommendations, together with a global convergence roadmap, position RWE as a strategic tool for regulators, payers, and clinicians. The paper concludes with a call for systemic accountability: industry must innovate responsibly, regulators must approve with foresight, payers must assess tools beyond medications, and health systems must bridge infrastructure gaps. Over the next 12–24 months, measurable commitments are required across all stakeholders to ensure that PM becomes everyday care. PM must serve patients—not just science, policy, or business—and that demands leadership grounded in scientific integrity and human empathy.

Introduction

“Artificial intelligence (AI) still struggles to distinguish between a man and a woman.”

“Personalised care means identifying biomarkers—especially in oncology.”

“I know I want something, but I’m not yet sure what that is.”

These are not lines from a dystopian novel or fragments of misunderstood trial protocols. They are real statements—echoed in hushed conversations and boldly shared in corporate corridors by those who present themselves as “inspirational leaders”. These remarks rarely appear in Townhall minutes or polished LinkedIn posts—but they persist. And so, I ask: as the patient of tomorrow, can I trust my health and future to those who confuse science with strategy, suppress dissent, and speed toward innovation like untrained drivers—while deftly navigating their own career paths?

Looking ahead, what awaits me as an elderly patient in my 80s diagnosed with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD)? How do I preserve my vision while managing comorbidities, aging, limited mobility, and no caregiver? As a cancer patient facing treatment-related toxicity, how do I avoid hospitalisation or treatment interruption? And if I live in a rural area with limited specialist access, how can I receive timely and accurate diagnosis of a skin condition when local expertise is scarce and waiting lists are long?

These are not hypothetical scenarios—they are common realities that transcend disease areas. The question is no longer how advanced our research & development (R&D) pipelines are, how fast we develop products, or how compelling our health economic models appear. The real question is: are these solutions truly made for me—not just for the average patient? Will they reach me wherever I live? And if costs are involved, who will share that burden to ensure not just longer life, but better life?

This mix of frustration, lived experience, and future concern drives me to write—not with resentment, but with hope. It is a call for a more accountable, compassionate, and patient-centered healthcare ecosystem. I write through the lens of a future patient—someone who has spent decades working for individuals with cancer, retinal, and immune-mediated diseases, and now expects healthcare to return that commitment by delivering smart, personalised, and human care. Care that goes beyond buzzwords and tick-boxes; care that sees patients as whole people; care that will one day knock on our own doors.

Personalised care does not exist in a vacuum. It must be grounded in the ecosystem that supports it—including the systems we use to generate and apply knowledge. That is where real-world evidence (RWE) becomes essential. Not as a vague concept, but as a practical, evolving tool to drive systemic change.

In this manuscript, we use personalized medicine (PM) as an umbrella term that encompasses both biomarker- and genomics-driven precision medicine as well as broader approaches such as person-centered care (“the right care, for the right person, at the right time”). Where regulatory agencies use alternate terminology (e.g., “precision medicine” in Japan or “personalised care” in the UK), we harmonize these under the broader umbrella while noting contextual differences. This ensures consistency across the text and Table 1.

Table 1

| Region/Country | Authority/Body | Definition or Focus of Personalized Medicine | Use of RWE in Personalized Medicine | Key Initiatives/References | Maturity Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | FDA | Tailoring medical treatment to genetic, biomarker, phenotypic, and lifestyle data | Regulatory decision-making (e.g., label expansions, post-marketing surveillance) | 21st Century Cures Act, FDA RWE Framework, Oncology Center of Excellence (1, 2) | High |

| Canada | CADTH | Typology-based: Molecular, digital, and clinical personalization | HTA in rare diseases, biomarker-driven care, co-dependent technologies | CADTH HTA guidelines, PM Typology Briefing (3) | Moderate |

| European Union | EMA/EC | Designing right therapy based on genotypic/phenotypic profiles, lifestyle, environment | Adaptive pathways, pharmacovigilance, benefit-risk assessment | ICPerMed, Regions4PerMed, EMA guidance on RWE (4–7) | High |

| United Kingdom | NHS/NICE | Right care for the right person at the right time; person-centered and genomics-informed | Medicines optimisation, service design, shared decision-making | NHS Genomics Strategy, NICE NG5 (8, 9) | High |

| Australia | MSAC | HTA of co-dependent technologies and diagnostics | Early economic modeling with RWE | MSAC evaluation reports (10) | Moderate |

| China | NMPA/NHC | National PM strategies linked to AI and digital health | Pilot real-world data zones, oncology-focused registries | Healthy China 2030, Hainan RWD pilots (11) | Emerging |

| Japan | PMDA | Precision-focused early access using biomarkers | RWE in rare disease approvals, Sakigake and Conditional Approvals | Sakigake designation, PMDA real-world datasets (12) | Moderate |

| South Korea | MFDS | Bioethics-compliant genetic data use in oncology and rare diseases | Draft RWE guidance, genomic screening initiatives | Korean Genome & Epidemiology Study, MFDS draft guidelines (13) | Emerging |

Global regulatory frameworks and strategies integrating real-world evidence (RWE) into personalized medicine (PM).

(1) In this manuscript, we use personalized medicine (PM) as the umbrella term, which encompasses approaches also referred to as “precision medicine”, “stratified medicine”, or “the right care at the right time”. Precision medicine is treated as a subset of PM with a narrower focus on biomarker- or genomics-driven stratification. Regional differences in terminology are preserved in the table to reflect regulator and HTA agency usage (e.g., PMDA Japan emphasizes “precision medicine,” whereas the UK NHS and NICE emphasize “right care, right time”).

(2) Maturity levels were added to contextualize readiness across regions. United States, EU, and UK are categorized as High maturity, with established regulatory pathways and multiple RWE-based approvals. Japan, Canada, and Australia are classified as Moderate, reflecting structured HTA or accelerated access initiatives. China and South Korea are marked as Emerging, where pilots and draft frameworks are ongoing. The absence of Africa and Latin America in this table highlights important gaps and underscores the urgency of extending RWE adoption globally.

FDA, U.S. food and drug administration; CADTH, Canadian agency for drugs and technologies in health; EMA, European medicines agency; EC, European commission; NHS, national health service; NICE, national institute for health and care excellence; MSAC, medical services advisory committee; NMPA, national medical products administration; NHC, national health commission; PMDA, pharmaceuticals and medical devices agency; MFDS, ministry of food and drug safety; HTA, health technology assessment; RWE, real-world evidence; RWD, real-world data; PM, personalized medicine.

This table summarizes the evolving definitions, regulatory uses, and national initiatives related to PM and the integration of RWE across major global regions. It highlights the diverse—but increasingly convergent—approaches used by regulatory authorities and HTA bodies to incorporate patient-centric, real-world data into policy, approval, and access pathways.

Table 1 is intended as a decision aid for policymakers and regulators; see Global Convergence and Harmonization and Policy and Implementation Recommendations for next-step actions.

Why RWE? Is it just another managerial trend of the past decade? A fashionable acronym on curriculum vitae (CVs)? Or does it offer a meaningful route to better evidence and smarter decisions? What do regulators and payers expect from RWE? And more importantly—how do we move from theory to tangible, lasting impact?

RWE, derived from real-world data (RWD)—including electronic health records (EHRs), claims, registries, digital health apps, and social media—is now a recognised component of health technology assessments (HTAs), regulatory decisions, and pricing and reimbursement frameworks. It supplements the knowledge generated through clinical trials and brings us closer to how medicine works in daily practice. RWE helps uncover where refinement is needed, where patient voices are missing, and how we can shift from clinical efficacy to real-world effectiveness.

This paper is both a scientific reflection and a personal testament. After three decades at the crossroads of biostatistics, real-world evidence, and drug development, I have seen remarkable progress—but also persistent blind spots. Despite rapid innovation in data science, AI, and personalised medicine, we still resist addressing the inertia and fragmented responsibility that hinder meaningful, patient-focused transformation.

If change is to be real, it must flow in both directions. Bottom-up: from all of us—researchers, innovators, patients—who embrace a mindset that looks beyond annual targets and dares to challenge convention. Top-down: from regulators, payers, and healthcare professionals who face patients at their most vulnerable and must reconcile care needs with resource constraints.

This section introduces the pressing need to rethink healthcare from the lens of the future patient. Drawing from real-life frustrations and insights built over decades of biostatistical and regulatory experience, it critiques superficial interpretations of personalised care and challenges the status quo of fragmented healthcare innovation. It positions RWE not as an administrative tool but as a necessary force to bring equity, depth, and true patient-centredness into the era of PM.

Global regulatory perspectives on RWE in PM

As PM evolves from concept to reality, global regulatory agencies increasingly recognize the importance of RWE in supporting its clinical, regulatory, and reimbursement applications. Although definitions and frameworks vary, a unifying principle emerges: personalized care cannot advance without understanding how interventions perform in real-world, diverse populations.

This section surveys how major global health systems and regulatory bodies—from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) to the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) and Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH)—are integrating RWE to support the development, assessment, and implementation of PM. It highlights key regional strategies, pilot frameworks, and data infrastructure investments, demonstrating a global movement toward convergence, but also noting disparities in readiness and execution. These evolving frameworks position RWE as both a policy and scientific driver of personalised care.

United States—the FDA's precision approach

FDA defines PM as tailoring medical treatment to individual characteristics, including genetic, biomarker, phenotypic, and psychosocial data (1). Through the 21st Century Cures Act and its RWE Framework, FDA has actively incorporated RWE into regulatory decisions, particularly in oncology, cardiology, and rare diseases. FDA's 2021 progress report highlights the value of EHRs, disease registries, and wearable data in real-world regulatory applications (2).

Canada—CADTH's typology-based evaluation

CADTH uses a structured typology to guide PM evaluation across molecular, digital, and clinical dimensions (3). RWE is particularly valued in CADTH's HTA when randomized controlled trial (RCT) data are insufficient or not reflective of real-life subpopulations. Co-development of therapies and companion diagnostics is actively encouraged.

European union—EMA and European commission alignment

EMA describes PM as using a patient's phenotypic and genotypic characteristics to design the right therapeutic strategy (4). EMA encourages RWE use in adaptive licensing, post-marketing safety, and biomarker validation. Simultaneously, the European Commission supports PM as a systemic transformation, enabled by big data, AI, and RWD integration (5). Initiatives such as ICPerMed and Regions4PerMed highlight regional innovation and infrastructure as essential components of RWE maturity (6). A 2021 joint EMA–PCWP/HCPWP workshop reinforced the importance of multi-stakeholder alignment for effective implementation (7).

United Kingdom—NHS and NICE

National Health System (NHS) England defines personalized care as “the right care for the right person at the right time”, incorporating genomics, digital health, and shared decision-making (8). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), through NG5 guidance, operationalizes this via medicines optimisation, emphasizing a person-centred approach, clinical appropriateness, and health system sustainability (9).

Australia—RWE in co-dependent technologies

Australia's Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) evaluates co-dependent technologies, such as diagnostics that enable PM therapies, using both clinical trial and RWD (10). This pragmatic HTA approach supports early reimbursement decisions and aligns closely with innovation pathways.

China—policy-led expansion with local pilot zones

China's national strategy embeds PM within the Healthy China 2030 and Precision Medicine Initiative (2016–2030) frameworks. While lacking a unified RWE regulatory framework, cities like Hainan and Beijing have launched RWD pilot zones to support precision oncology and pharmacovigilance (11). However, challenges persist around data standardization, interoperability, and regional capacity disparities.

Japan—accelerated innovation through Sakigake

Japan's Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) supports PM through accelerated pathways like Sakigake and Conditional Early Approval. RWE derived from registries and EHRs is increasingly used to complement biomarker-based approvals, especially in rare and intractable diseases (12).

South Korea—ethical integration and infrastructure building

South Korea continues to develop a structured approach to PM by balancing innovation with ethical oversight. Recent revisions to the Bioethics and Safety Act aim to support genetic research while safeguarding patient rights (13). MFDS has proposed draft RWE guidelines for use in regulatory submissions, with early focus on oncology and rare diseases.

National initiatives such as the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study provide a foundation for patient stratification and data-driven screening. In parallel, the Korean Precision Medicine Initiative promotes digital infrastructure, EHR harmonization, and integration of hospital registries, enabling the scalable use of RWE in real-world settings. South Korea's regulatory bodies also reference EMA and FDA frameworks to promote international alignment (14). These efforts, combined with government investment and AI integration, position the country as a rising contributor to the global personalized care ecosystem.

As shown in Table 1, global agencies vary in their approaches: FDA emphasizes label expansion and pragmatic RWE, EMA fosters adaptive licensing, CADTH applies structured HTA frameworks, and Asia-Pacific regulators are building early pilots. We explicitly reference Table 1 here to ensure that readers understand its role as a comparative framework rather than a stand-alone list.

Table 1 summarizes the global regulatory frameworks, highlighting how key agencies incorporate RWE to support the development and implementation of PM. To aid interpretation, we also indicate relative maturity levels: United States, EU, and UK demonstrate high maturity with established regulatory pathways; Japan and Canada show moderate readiness through pilots and typology-based HTA; while China and South Korea remain emerging with early draft guidance and regional pilot zones. The absence of Africa and Latin America highlights important gaps that require urgent research and policy development.

The convergence of RWE and personalized medicine

PM promises to tailor medical interventions to an individual's genetic, phenotypic, behavioural, and environmental profile. However, clinical trials—while essential—are limited in their ability to fully capture the variability of real-life patients. RWE, derived from RWD, bridges this gap by providing population-wide, longitudinal insights into safety, efficacy, adherence, and quality of life (QoL) across diverse healthcare settings.

Oncology: AI, digital tools, and patient reported outcomes (PRO) integration

In oncology, the integration of digital health platforms and molecular diagnostics has revolutionized the personalization of care. A notable application of digital health tools is the use of electronic PROs (ePROs) to monitor symptoms and QoL in patients with advanced melanoma. These tools enable earlier clinical intervention, support improved adherence to therapy, and may contribute to reduced hospitalizations (15). Importantly, these benefits have been demonstrated in pragmatic trials with external validation, although subgroup analyses (e.g., older patients or those with comorbidities) remain limited, highlighting the need for equity-focused validation (15).

Further, machine learning (ML) models have been increasingly used to predict treatment outcomes, survival probabilities, and toxicity responses. These include causal ML models applied to oncological RWD (16), and AI-powered stratification tools that guide clinical decision-making in breast and colorectal cancer (17, 18). Most of these applications are at the “emerging” stage: models are internally validated but not always externally calibrated across diverse populations, and subgroup performance (by age, sex, ethnicity) is often underreported. This distinction between exploratory vs. established evidence is now explicitly stated to guide readers (18, 19). ML-based diagnostic systems, trained on imaging data, also assist in early cancer detection, including melanoma, by identifying histopathological patterns beyond human capacity (19, 20).

Predictive models like those developed by Parikh et al. use EHR data to estimate 6-month mortality among patients with metastatic cancer, enabling clinicians to better align treatment with patients' goals of care (21).

RWE building blocks—oncology

-

Data sources: EHRs, oncology registries, wearable data, and ePRO platforms

-

Data standards/models: Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model (CDM) increasingly adopted; HL7 FHIR for interoperability

-

Curation rules: Structured abstraction of lab values, tumour stage, PROs with missing data imputation

-

Identification strategy: Both associational analyses (e.g., PRO correlations) and causal ML approaches

-

Validation metrics: External validation in selected datasets; calibration often limited; subgroup performance gaps remain

-

Deployment constraints: Integration into oncology workflows requires EHR plug-ins, staff training, and payer alignment on endpoints such as hospitalization reduction

Adoption path—oncology

To operationalize these tools, clinics require: (1) access to interoperable oncology EHRs and registries, (2) minimal Information Technology (IT) upgrades for ePRO collection, (3) staff training in symptom monitoring workflows, and (4) payer recognition of reduced hospitalizations and improved QoL as reimbursable endpoints. This structured pathway offers decision-makers a reproducible template for implementation. This pathway is consistent with Japan's Sakigake designation and PMDA's use of RWE in accelerated oncology approvals, illustrating how regulatory maturity can enable earlier access to innovations (12).

Ophthalmology: AI-driven monitoring and biomarker optimization

Ophthalmology offers some of the most mature examples of PM supported by RWE and digital tools. Home-based optical coherence tomography (OCT) enables remote disease monitoring for patients with nAMD, reducing clinic visits and ensuring timely anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) administration (22). These tools are among the most established in the field: several validation studies confirm reliability of home OCT in detecting disease activity, though subgroup data for older patients living alone remain sparse (22–25).

AI-driven interpretation of OCT scans has also shown high accuracy in identifying lesion activity in nAMD, matching expert graders (23). However, most studies remain internally validated; external, multi-site calibration and subgroup analyses by ethnicity and comorbidity are not yet consistently reported, underscoring the need for equity-focused validation (18, 19). In addition, fluctuations in macular fluid volume, quantified using automated imaging tools, have been associated with changes in visual acuity (VA)—providing actionable insight into therapy adjustments (24).

Recent studies have demonstrated the prognostic value of AI models that predict long-term visual outcomes based on baseline OCT biomarkers, allowing stratified care plans (25, 26). Furthermore, large language models are emerging to assist in automated interpretation and decision support for ophthalmic imaging (27).

RWE building blocks—ophthalmology

-

Data sources: OCT imaging, ophthalmology registries, electronic health records, patient-generated visual function scores

-

Data standards/models: Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) for imaging, OMOP CDM for structured data, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) for interoperability

-

Curation rules: Automated segmentation, harmonization of imaging protocols, missing data imputation for longitudinal monitoring

-

Identification strategy: Predictive and causal ML models linking biomarkers (fluid volume, OCT features) to visual acuity outcomes

-

Validation metrics: High internal accuracy; limited external validation across multi-ethnic cohorts; subgroup performance not systematically reported

-

Deployment constraints: Dependence on device access, internet connectivity, and clinic workflow adaptation

Adoption path—ophthalmology

Successful implementation requires (1) provision of home OCT devices with reimbursement models, (2) integration of AI-driven interpretation into EHR platforms, (3) training clinicians to interpret automated lesion activity alerts, and (4) recognition by payers of improved visual acuity outcomes and reduced clinic burden as measurable endpoints. The EU's ICPerMed and Regions4PerMed initiatives provide policy alignment for integrating OCT biomarkers and home monitoring into personalized ophthalmology programs.

Dermatology: AI, teledermatology, and skin classification

In dermatology, access remains a challenge, especially in underserved or rural areas. AI-powered smartphone apps and deep learning (DL) models now offer dermatologist-level accuracy in skin disease classification, including eczema, psoriasis, and melanoma (28, 29). While promising, these remain emerging applications: most are validated against limited test datasets and frequently underperform on darker skin tones due to training data imbalance. This limitation is explicitly acknowledged as part of equity and subgroup performance reporting (20, 28, 29). These tools enable patients to self-monitor lesions and receive early alerts for suspicious changes.

AI models have demonstrated high sensitivity in diagnosing melanocytic lesions, while also supporting dermatologists in triaging cases that require urgent attention (30, 31). These developments improve early detection and reduce diagnostic delays, particularly for high-risk patients or those with limited access to specialists.

Digital dermatology platforms also assist in monitoring treatment response for chronic inflammatory diseases. Patients with chronic hand eczema, for instance, can benefit from AI tools that assess lesion severity over time, facilitating personalized adjustments in topical or systemic therapies (32). However, deployment at scale is constrained by integration into dermatology workflows, reimbursement models, and the need for longitudinal validation across diverse populations.

Moreover, recent reviews emphasize the growing role of causal AI in dermatology—not only for classification but also for understanding therapeutic pathways, patient subgroups, and outcomes (33, 34).

Here, the manuscript explores how RWD technologies have moved beyond conceptual promise to practical application across oncology, ophthalmology, and dermatology. The section presents concrete examples—such as the use of ePROs in melanoma, home-based OCT in retinal disease, and AI-powered applications for dermatological diagnosis—that demonstrate how digital tools, when integrated with RWE, can personalise care delivery, improve outcomes, and democratise access. The evidence illustrates the tangible, multidisciplinary impact of this convergence.

RWE building blocks—dermatology

-

Data sources: Smartphone images, teledermatology platforms, dermatology registries, EHRs

-

Data standards/models: FHIR for clinical metadata, OMOP extensions for dermatology-specific outcomes

-

Curation rules: Quality filters for patient-generated images, consensus scoring for lesion severity, and harmonized annotation protocols

-

Identification strategy: DL classification models and causal inference to explore treatment response pathways

-

Validation metrics: High sensitivity/specificity in controlled settings; limited external validation on darker skin tones; subgroup performance gaps significant

-

Deployment constraints: Reliance on patient smartphone quality, internet access, and specialist workflow acceptance

Adoption path—dermatology

Practical adoption requires (1) payer-approved reimbursement for teledermatology consultations, (2) standardized pathways for uploading and securing patient-generated images, (3) integration of AI lesion scoring into dermatology EHR modules, and (4) systematic validation in multi-ethnic populations to ensure equity. China's Hainan RWD pilot zones demonstrate how regulatory sandboxes can accelerate adoption of teledermatology and AI validation frameworks in dermatology (11, 35).

Expanded discussion: challenges, risks, and future directions in PM and RWE

Reading the current regulations, my understanding—as the patient of tomorrow—is that health authorities are engaging seriously in discussions about personalised care. Despite its varied definitions, PM clearly refers to tailoring diagnostics, therapies, and prevention strategies to individual characteristics and phenotypes. This alone is enough to make a patient feel seen—not just as another average case, but as a unique individual whose care maximizes safety, QoL, and therapeutic efficacy.

However, achieving optimal outcomes requires tight collaboration between industry, regulators, payers, healthcare providers, and patients themselves. Each stakeholder has a role to play in addressing the embedded challenges, limitations, and risks associated with implementation.

Challenges and limitations

Despite the transformative potential of PM supported RWE, several persistent structural and methodological challenges must be addressed, particularly around implementation, validation, and equity. In particular, reproducibility, equity, and lifecycle monitoring must become non-negotiable elements of any RWE program. One of the key limitations is the inconsistency and variable quality of RWD. EHRs differ substantially across geographies and systems, with heterogeneity in data capture, coding, and interoperability. This lack of CDMs impairs cross-country comparison and limits the generalizability of findings (35).

Further issues arise from EHRs, registries, and PROs, which often lack harmonised data formats and complete records (36, 37). These inconsistencies impede evidence synthesis and hinder predictive algorithm deployment in clinical settings (38). Sheffield et al. note how difficult it is to replicate clinical trial outcomes using RWD due to misclassification, missing values, and limited follow-up periods (39).

On the methodological front, transparency and reproducibility of RWE studies remain uneven. While frameworks like RCT-DUPLICATE and HARPER call for trial-like alignment in design and analysis (40), practices such as model registration and prespecified protocols are still not standard across RWE research.

Bias and opacity in algorithms represent another major risk. Many AI systems are developed on datasets lacking demographic diversity, compromising performance for underrepresented populations (41, 42). For example, dermatology AI applications frequently underperform on darker skin tones due to training data imbalances (20).

The “black-box” nature of ML systems further complicates their integration into regulated clinical decision-making environments (43). Even when model explanation techniques like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) or Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) are available (44), their use in regulatory-grade RWE is not yet consistent (45).

Regulatory inconsistency is another constraint. Agencies like the FDA, EMA, MFDS, and HTA bodies are developing RWE frameworks, but their standards for data quality, model validation, and clinical utility vary significantly (46). Similarly, payers have different thresholds for incorporating RWE into reimbursement, especially for diagnostics and co-dependent technologies (47).

Cost considerations further complicate matters. Digital tools for home monitoring and decentralised care often fall into grey zones of responsibility between payers, providers, and patients (48). High implementation costs and the lack of long-term effectiveness data make reimbursement uncertain, even when early clinical value is evident (49, 50).

Ethical concerns regarding consent, data reuse, and algorithmic decision-making are significant. Patients are rarely aware of how their data are used after collection—particularly in decentralised or digital settings or when data feeds into predictive tools (51, 52). Even anonymised datasets can carry re-identification risks. Dynamic consent and improved data custodianship are urgently needed (53).

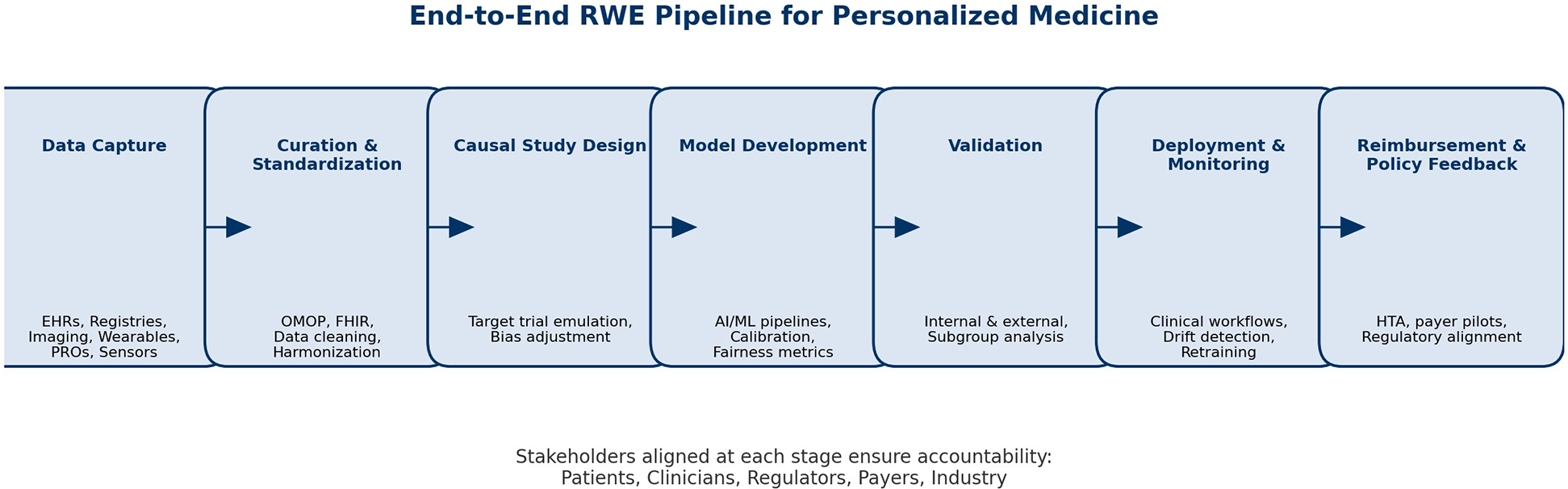

Figure 1 illustrates a consolidated roadmap for the ethical and scalable adoption of RWE in PM, integrating strategic priorities across stakeholders.

Figure 1

Real-world evidence (RWE) as a bridge to personalized medicine (PM). The figure illustrates how RWE can connect the traditional clinical evidence model—centered around RCTs, trial protocols, and average patient profiles—with a future of PM, AI-enhanced decision-making, and digital health. The bridge is made possible by ethical, interoperable, explainable, and patient-centric data streams such as EHRs, registries, PROs, and social media. Figure 1 should be read as a strategic tool for translational planning, not only an illustration.

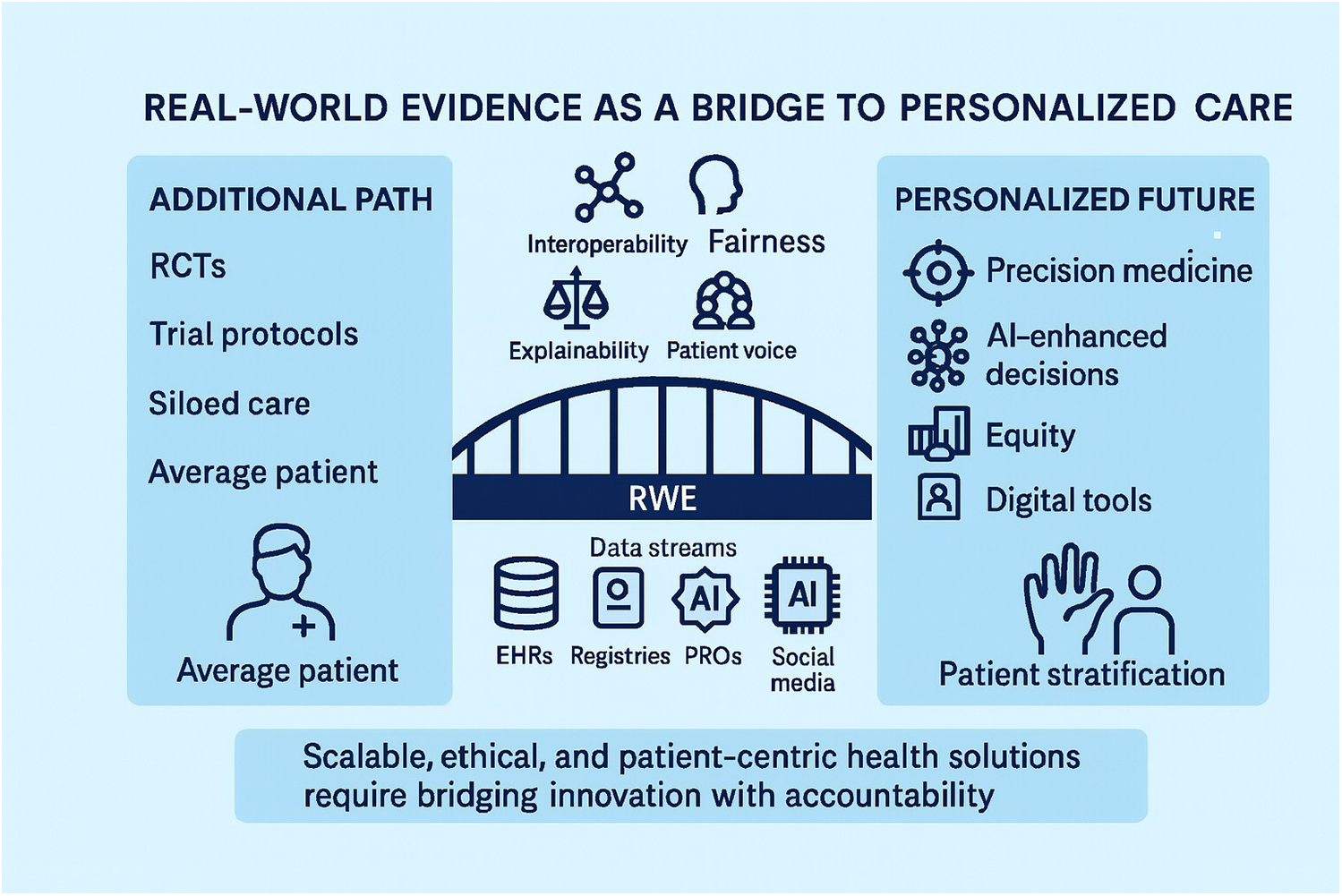

Figure 2

End-to-end pipeline for real-world evidence (RWE) in personalized medicine (PM). The figure illustrates the sequential stages through which real-world data are transformed into actionable evidence: data capture, curation and standardization, causal study design, AI/ML model development, validation, deployment into clinical workflows, and reimbursement/policy feedback. Each stage is aligned with stakeholder roles—patients, clinicians, regulators, payers, and industry—underscoring the shared accountability required to ensure quality, transparency, and equity. Unlike Figure 1, which emphasizes the bridge between traditional RCT-based evidence and personalized care, Figure 2 provides a more granular roadmap for operationalizing RWE in practice, making explicit the checkpoints where methodological rigor and ethical safeguards must be applied. Figure 2 functions as an operational checklist for teams delivering RWE in PM.

Risk mitigation strategies

Several solutions have been proposed to mitigate the risks and limitations of RWE in personalised care.

First, aligning RWE methodologies with RCT standards is essential. Initiatives like the Real-World Evidence Transparency Initiative, use of prespecified protocols, and application of CDMs (e.g., OMOP) can increase confidence in RWE findings (54, 55).

Second, the future lies in hybrid evidence ecosystems that blend RWE with traditional trial data in iterative feedback loops for regulators and clinicians (56).

Third, regulatory-grade AI validation frameworks must be required, ensuring external validation, subgroup performance, and post-deployment monitoring (57).

Fourth, HTA frameworks should be updated to reflect process benefits like patient empowerment and improved diagnosis, in addition to clinical outcomes. Evaluations of personalised nutrition interventions suggest that multi-stakeholder dialogue and iterative modelling are essential for early-stage PM assessments (58, 59).

Finally, ethical implementation requires strong patient and public involvement (PPI). Participatory models and early patient engagement can help build trust and improve the clinical relevance of AI-enabled PM solutions (60, 61).

Lifecycle monitoring and drift

Lifecycle monitoring of deployed models is critical. Data drift across hospitals, imaging devices, or populations can erode performance over time. We propose systematic triggers for retraining when calibration deteriorates, ensuring that predictive tools remain safe and equitable across diverse sites (18, 45, 61).

Equity checklist

Equity in AI-enabled RWE requires consistent subgroup reporting. We propose a short checklist: (1) audit demographic representativeness of training data; (2) report subgroup performance metrics; (3) apply fairness indicators (e.g., calibration by sex, ethnicity, age); and (4) disclose limitations openly. This checklist directly addresses known performance gaps, such as dermatology AI underperforming on darker skin tones (20, 41, 45). This checklist can also serve as a procurement and payer assessment tool, ensuring that AI solutions adopted into healthcare contracts meet equity and fairness standards.

Implementation blueprint

Implementation Blueprint for Decision-Makers: Successful adoption requires a “starter kit” that includes: (1) minimal IT integration with existing EHRs, (2) workflow redesign for ePRO and Patient-Generated Health Data (PGHD) capture, (3) staff training modules for AI-supported decision-making, and (4) payer-aligned endpoints (reduced hospitalizations, improved QoL, diagnostic accuracy). This structured pathway makes RWE operational, not aspirational (36, 54, 56).

From clinic-centric RWE to healthcare 5.0

The evolution of RWE is moving beyond hospital and clinic walls toward a new paradigm often referred to as Healthcare 5.0. This framework emphasizes care that is human-centric, sustainable, and resilient. In alignment with Tan et al. (62), we now highlight how continuous lifestyle and environmental data must be treated as first-class signals in PM—not only genomic and clinical variables (see Table 2 for pillar-level alignment).

Table 2

| Healthcare 5.0 Pillar | RWE Alignment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Human-centric | Integration of patient-generated data (activity, sleep, mental health) into care pathways | Remote monitoring of fatigue in oncology patients |

| Sustainable | Continuous monitoring reduces unnecessary hospital visits and optimizes therapy scheduling | Home OCT for nAMD, reducing travel burden |

| Resilient | Lifecycle monitoring and retraining of AI models against data drift | Recalibration of dermatology AI apps across different skin types |

Aligning real-world evidence (RWE) with healthcare 5.0 pillars.

RWE, real-world evidence; AI, artificial intelligence; OCT, optical coherence tomography; nAMD, neovascular age-related macular degeneration.

This table synthesizes the core reproducibility elements that enable case studies in three disease areas to be generalized beyond single studies or pilot programs. Each vignette is mapped against a set of building blocks: data sources, data standards/models (e.g., OMOP, FHIR, DICOM), curation rules, analytic identification strategy, validation metrics, and deployment constraints. By presenting these components side by side, the table demonstrates recurring patterns in how RWE is constructed and deployed. It also highlights key gaps—such as external validation, subgroup performance, and workflow integration—that remain barriers to equitable implementation. In contrast to Table 1, which provides a global regulatory panorama, Table 2 focuses on the clinical and methodological scaffolding necessary to translate digital tools and real-world data into reproducible, accountable personalized care.

Table 2 serves as a deployment playbook connecting Healthcare 5.0 pillars to concrete RWE building blocks.

Wearables (e.g., continuous glucose monitors, actigraphy), environmental sensors [e.g., air quality, temperature, ultraviolet (UV) exposure], and high-throughput connectivity (5G/6G) are enabling longitudinal RWE streams. These real-time data flows, when integrated with EHRs and registries under strong governance controls, allow for hyper-personalized care that adapts dynamically to patient context (62).

Table 2 provides an alignment of RWE building blocks with Healthcare 5.0 pillars, showing how data and governance expand under this new paradigm.

We propose a call to action: stakeholders should extend RWE programs to systematically capture lifestyle and environmental determinants, supported by privacy-by-design principles. This would move PM from reactive, clinic-centered care toward proactive, contextual, and equitable care ecosystems.

Regulatory pragmatics—minimum requirements for RWE submissions

To translate narrative principles into actionable guidance, we propose a one-page regulatory checklist that can travel consistently with any RWE submission:

Data quality: Prespecified CDM (e.g., OMOP), minimum completeness thresholds, missing data strategy.

Traceability: End-to-end audit trail linking raw RWD to final analysis dataset.

Validation artifacts: Documentation of internal and external validation, calibration plots, and subgroup performance metrics.

Transparency: Prespecified protocol, public registration of study design, and clear reporting of deviations.

Patient voice: Demonstrated incorporation of PROs or PGHD where clinically appropriate.

This pragmatic summary responds directly to regulators' demand for reproducibility while giving sponsors a concrete template for future submissions (

35,

36,

63).

Pre-deployment audit checklist for clinics and vendors

Before integrating RWE-based AI tools into practice, we recommend that clinics and vendors apply a short audit covering four domains:

Dataset representativeness: Evidence that training data cover relevant age, sex, ethnicity, and comorbidity distributions.

Model explainability: Availability of explanations appropriate for clinicians (e.g., SHAP plots, feature importance).

Human-factors testing: Usability testing with clinicians and patients to assess workflow fit and risk of alert fatigue.

Patient-facing transparency: Clear disclosure of how data are used, algorithm limitations, and channels for patient feedback.

This checklist converts high-level ethical risks into operational safeguards that are implementable across diverse healthcare settings (

44,

51,

61).

Learning health systems

RWE also enables continuous learning health systems: RWD feeds into evidence generation, which in turn updates care plans and informs regulatory and payer feedback. This data → evidence → care → policy loop ensures PM evolves continuously, not episodically (54, 57).

Comparative readiness commentary

As noted in Table 1, readiness varies: United States, EU, and UK are high maturity; Japan, Canada, and Australia are moderate; China and South Korea remain emerging. The absence of Africa and Latin America underscores urgent needs for infrastructure, governance, and policy development in these regions (6, 11–14). See Global Convergence and Harmonization for mechanisms to close these gaps.

Global convergence and harmonization

While regional frameworks for real-world evidence (RWE) are advancing at different speeds, global convergence is increasingly critical to avoid fragmented standards and duplicative efforts. Collaborative initiatives between regulators provide a foundation. For example, the FDA and EMA have jointly explored methodological guidance and case studies on RWE acceptance, signaling a shared commitment to reproducibility and transparency in decision-making (35–37). Within Europe, the launch of DARWIN EU represents a major step toward creating a federated, interoperable RWD infrastructure that can serve regulators, payers, and HTA agencies across the region (35–37).

At the global level, the ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice revision explicitly acknowledges pragmatic and real-world designs, underscoring the growing role of RWE in regulatory science. However, convergence is uneven. While the United States, EU, and UK are classified as high-maturity regions with established pathways (Table 1), Asia-Pacific regulators often lag behind, with pilots in Japan, China, and South Korea not yet harmonized with US/EU frameworks. Similarly, Canada and Australia remain at moderate levels of integration, with RWE primarily applied in rare diseases and co-dependent technology assessments.

To bridge these disparities, mutual learning mechanisms are needed. Template sharing of protocols, joint scientific advice, and common data model pilots could accelerate alignment, particularly in emerging regions. Equally important is the role of HTA agencies and payers, who must converge on minimum evidence standards to support equitable patient access globally. Without such harmonization, personalized medicine risks advancing only in well-resourced settings, further widening the equity gap (35–37).

This global convergence arc highlights the importance of RWE not as a local experiment but as an international priority, requiring cooperation across regulators, HTA bodies, payers, and industry to establish common, trusted standards for evidence generation. See Policy and Implementation Recommendations for an actionable checklist.

Policy and implementation recommendations

To accelerate integration of RWE into personalized medicine globally, we propose a short checklist for policymakers and regulators:

Shared minimum dataset: define a core, internationally shared set of RWE elements required across submissions to improve comparability.

Privacy rules for continuous data: establish harmonized, privacy-by-design governance for Internet of Things (IoT) devices (such as connected wearables, home medical devices, and environmental sensors), ensuring that lifestyle and environmental data streams (sleep, activity, UV exposure, air quality) are securely managed, consented, and interoperable across health systems.

Interoperability standards: promote convergent adoption of OMOP, FHIR, and DICOM adoption to enable cross-border RWE use.

Equity safeguards: require subgroup performance reporting and representativeness audits for every AI-enabled RWE submission.

Capacity building in emerging regions: incentivize investment and international collaboration in Africa, Latin America, and Asia-Pacific.

Stakeholder accountability: link regulatory and payer decisions to measurable outcomes in patient access, quality of care, and system sustainability.

This checklist provides regulators and policymakers with a practical starting point for accelerating convergence while safeguarding equity and patient trust (

54,

56,

59).

Next steps and future directions

To transition PM from pilot programs to routine care, the focus must shift to transparency, reproducibility, and patient-centric design. Standardising protocols, publishing negative findings, and integrating digital biomarkers and remote monitoring into practice are necessary steps (63, 64). Trust in AI systems will be enhanced by explainability tools (e.g., SHAP values), external validation, and fairness metrics (65). Embedding PPI as a foundational element, rather than an afterthought, will foster public trust and ensure ethical scalability of personalised care initiatives (53).

Conclusion

PM is no longer aspirational—it must become everyday care. But its promise hinges on collective responsibility and intentional action.

Industry must commit to innovation grounded in ethics, inclusivity, and external validation of digital tools and RWD applications. Regulators must shift from approving only drugs to also supporting rigorously validated AI models, companion diagnostics, and infrastructural digital health tools. Payers must broaden their perspective beyond medications, valuing early diagnosis, remote monitoring, and AI-enhanced patient-centered insights. Healthcare systems, particularly those serving underserved or rural communities, must invest in the digital capacity and workforce needed to harness these innovations equitably.

Above all, patients—who contribute not only their data but their lives, and who often bear the consequences of our innovations—deserve transparency, empathy, and trust. Responsibility cannot be offloaded to algorithms, junior staff, or vague governance frameworks. Patients have the right to receive clear, honest explanations about the predictions that inform their care, the decisions made on their behalf, and how their data is being used.

As soon as possible, each stakeholder should commit to implementing measurable actions within their scope, in a collaborative manner with other stakeholders, keeping in mind that the key value is patients and their lives:

Industry: publish protocols and validation datasets for AI models; demonstrate subgroup performance; establish equity dashboards.

Regulators: harmonize minimum RWE submission standards; pilot shared templates for global convergence.

Payers: include remote monitoring and AI-enabled diagnostics in reimbursement pilots; define reimbursable endpoints beyond drug efficacy.

Clinicians and health systems: adopt site-readiness criteria; train staff to integrate ePROs, PGHD, and AI decision-support tools into workflows.

Patients and advocates: co-develop transparency statements; participate in governance boards overseeing RWE use.

This is not simply a scientific or policy challenge—it's a moral one. The persons seated behind the screen must embody leadership, not just in title but in integrity. PM isn't about trends or talent pipelines—it's about human lives. By grounding these responsibilities in concrete actions, stakeholders can ensure that PM becomes everyday care—equitable, accountable, and patient-centered. Let us act on this understanding, starting now.

Statements

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Visualization, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses heartfelt gratitude to his daughter, whose curiosity, resilience, and unwavering encouragement have been a constant source of inspiration. Her presence is a daily reminder of the responsibility to help shape a more transparent, equitable, and evidence-informed healthcare system. With over 30 years of leadership experience across global pharmaceutical companies—spanning clinical development, real-world evidence, and medical affairs—the author is motivated to share accumulated knowledge with the next generation of researchers, healthcare leaders, and policymakers. This manuscript is part of that effort: a contribution grounded in practice, aimed at exploring how RWE can support the scalable, ethical, and meaningful implementation of personalised care. Several thematic insights and conceptual foundations in this manuscript were originally developed and shared by the author in a series of professional reflections published on LinkedIn (Alexandros Sagkriotis). The author also extends sincere thanks to the reviewers and editors of Frontiers in Health Services, whose constructive critiques and thoughtful suggestions substantially improved the clarity, balance, and practical applicability of this manuscript. Their feedback helped transform the paper from a narrative review into an actionable playbook, strengthening its relevance for regulators, payers, clinicians, and policymakers.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Portions of this manuscript, including language refinement and idea framing, were supported using OpenAI's GPT-4 (ChatGPT) model. All content was critically reviewed, edited, and validated by the author to ensure scientific integrity and originality.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

- AI

artificial intelligence

- anti-VEGF

anti–vascular endothelial growth factor

- CADTH

Canadian agency for drugs and technologies in health

- CDM

common data model

- CV

curriculum vitae

- DICOM

digital imaging and communications in medicine

- DL

deep learning

- EC

European commission

- EHRs

electronic health records

- EMA

European medicines agency

- ePROs

electronic patient-reported outcomes

- FDA

U.S. food and drug administration

- FHIR

fast healthcare interoperability resources

- HTAs

health technology assessments

- IT

information technology

- IoT

internet of things

- LIME

local interpretable model-agnostic explanations

- MFDS

ministry of food and drug safety (South Korea)

- ML

machine learning

- MSAC

medical services advisory committee (Australia)

- nAMD

neovascular age-related macular degeneration

- NHC

national health commission (China)

- NHS

national health service (UK)

- NICE

national institute for health and care excellence (UK)

- NMPA

national medical products administration (China)

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- OMOP

observational medical outcomes partnership

- PGHD

patient-generated health data

- PM

personalized medicine

- PMDA

pharmaceuticals and medical devices agency (Japan)

- PPI

patient and public involvement

- QoL

quality of life

- PROs

patient reported outcomes

- R&D

research and development

- RCTs

randomized controlled trials

- RWE

real-world evidence

- RWD

real-world data

- SHAP

SHapley additive exPlanations

- UV

ultraviolet

- VA

visual acuity.

References

1.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Precision Medicine. (2018). Available online at:https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/precision-medicine(Accessed August 08, 2025).

2.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Personalized Medicine at FDA: The Scope & Significance of Progress in 2021 (2022). Available online at:https://www.fda.gov/media/155682/download(Accessed August 08, 2025).

3.

CADTH. Personalized Medicine Typology Briefing (2021). Available online at:https://cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/PM_Typology.pdf(Accessed August 08, 2025).

4.

European Medicines Agency. Personalised Medicine. (2025). Available online at:https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/personalised-medicine(Accessed November 29, 2025).

5.

European Commission. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future: Personalised Medicine. Available online at:https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/research-area/health-research-and-innovation/personalised-medicine_en(Accessed August 08, 2025).

6.

Nardini C Osmani V Cormio PG Carta MG Kautz T Boccia S . The evolution of personalized healthcare and the pivotal role of European regions in its implementation. Pers Med. (2021) 18(3):283–94. 10.2217/pme-2020-0115(Accessed August 08, 2025).

7.

European Medicines Agency. Report—Patients’ and Consumers’ Working Party (PCWP) and Healthcare Professionals’ Working Party (HCPWP) Joint Workshop on Personalised Medicines (2021). Available online at:https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/report-patients-consumers-working-party-pcwp-healthcare-professionals-working-party-hcpwp-joint_en.pdf(Accessed August 08, 2025).

8.

NHS England. Personalised Medicine in Practice (2020). Available online at:https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/personalised-medicine-in-practice(Accessed August 08, 2025).

9.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medicines Optimisation: The Safe and Effective Use of Medicines to Enable the Best Possible Outcomes. NG5 (2015). Available online at:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5(Accessed August 08, 2025).

10.

Merlin T Street J Pearson SA . Personalized medicine and co-dependent technologies: a review of policy development and reimbursement decisions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2016) 32(3):137–44. 10.1017/S0266462316000304

11.

Di Marcantonio R . Personalized medicine in China: an overview of policies, programs, and partnerships. World Med Health Policy. (2024) 16(1):4–16. 10.1002/wmh3.591

12.

Japan PMDA. Conditional Early Approval System and Sakigake Designation System. Available online at:https://www.pmda.go.jp(Accessed August 08, 2025).

13.

ManagingIP. Korea Updates Rules on Personalised Medicines. Managing Intellectual Property (October 2023). Available online at:https://www.managingip.com(Accessed August 08, 2025).

14.

Research Nester. South Korea Personalized Medicine Market Report (Published 2023). Available online at:https://www.researchnester.com/reports/south-korea-personalized-medicine-market/5152(Accessed August 08, 2025).

15.

Mohr P Ascierto P Addeo A Vitale MG Queirolo P Blank C et al Electronic patient-reported outcomes, fever management, and symptom prediction among patients with BRAF V600 mutant stage III–IV melanoma: the Kaiku Health platform. EJC Skin Cancer. (2024) 2:100254. 10.1016/j.ejcskn.2024.100254

16.

Feuerriegel S Frauen D Melnychuk V Schweisthal J Hess K Curth A et al Causal machine learning for predicting treatment outcomes. Nat Med. (2024) 30:958–68. 10.1038/s41591-024-02902-1

17.

Kourou K Exarchos KP Papaloukas C Sakaloglou P Exarchos T Fotiadis DI et al Applied machine learning in cancer research: a systematic review for patient diagnosis, classification and prognosis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. (2015) 13:8–17. 10.1016/j.csbj.2014.11.005

18.

Kleppe A Skrede OJ De Raedt S Liestøl K Kerr DJ Danielsen HE et al Designing deep learning studies in cancer diagnostics. Nat Rev Cancer. (2021) 21:199–211. 10.1038/s41571-020-00450-y

19.

Stratigos AJ Forsea AM Erdmann M Antoniou C Nagore E Olsen CM et al Predictive modeling and machine learning for melanoma: present and future. J Clin Oncol. (2022) 40(22):2504–10. 10.1200/JCO.21.02496

20.

Liopyris K Stratigos AJ Gregoriou S Dias J . Artificial intelligence in dermatology: challenges and perspectives. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). (2022) 12:2637–51. 10.1007/s13555-022-00833-8

21.

Parikh RB Manz C Chivers C Regan L Schwartz JS Navathe AS et al Machine learning approaches to predict 6-month mortality among patients with cancer. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2(10):e1915997. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15997

22.

Schmidt-Erfurth U Vogl WD Jampol LM Bogunović H Sadeghipour A Waldstein SM et al Application of automated quantification of fluid volumes to anti-VEGF therapy of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. (2020) 127(9):1211–9. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.022

23.

Chakravarthy U Goldenberg D Young G Mietzsch F Deneke J Neubauer A et al Automated identification of lesion activity in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. (2016) 123(8):1731–6. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.009

24.

Chakravarthy U Havilio M Syntosi A Young G Deneke J Neubauer A et al Impact of macular fluid volume fluctuations on visual acuity during anti-VEGF therapy in eyes with nAMD. Eye (Lond). (2021) 35(9):2416–23. 10.1038/s41433-020-01354-4

25.

Schmidt-Erfurth U Bogunović H Schlegl T Sadeghipour A Gerendas BS Langs G et al Prognostic modelling of visual outcome in neovascular age-related macular degeneration using machine learning on baseline OCT biomarkers. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:1–12. 10.1038/s41598-018-31961-0

26.

Schmidt-Erfurth U Sadeghipour A Gerendas BS Waldstein SM Bogunović H Langs G et al Artificial intelligence in retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2018) 67:1–29. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.07.004

27.

Jin K Yuan L Wu H Wang Y Wang J Zhang Y et al Exploring large language models for next generation of artificial intelligence in ophthalmology. Front Med (Lausanne). (2023) 10:1291404. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1291404

28.

Hartmann T Passauer J Hartmann J Wagner L Amler S Biermann J et al Basic principles of artificial intelligence in dermatology explained using melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2024) 22:339–47. 10.1111/ddg.15322

29.

Steeb T Wessely A Kohl M Berking C Heppt MV . Automated machine learning analysis of patients with chronic skin disease using a medical smartphone app: retrospective study. J Med Internet Res. (2023) 25:e46332. 10.2196/46332

30.

Hebebrand M . Review Investigates Machine Learning in Skin Disease Identification. New York: Dermatology Times (2024). Available online at:https://www.dermatologytimes.com/view/review-investigates-machine-learning-in-skin-disease-identification

31.

Hebebrand M . Comparing AI Models for Dermatological Diagnoses. New York: Dermatology Times (2024). Available online at:https://www.dermatologytimes.com/view/comparing-ai-models-for-dermatological-diagnoses

32.

Sengupta D . Artificial intelligence in diagnostic dermatology: challenges and the way forward. Indian Dermatol Online J. (2023) 14(6):782–7. 10.4103/idoj.idoj_462_23

33.

Peltner J Becker C Wicherski J Müller T Schneider A Hoffmann S et al . The EU project Real4Reg: unlocking real-world data with AI. Health Res Policy Syst. (2025) 23:27. 10.1186/s12961-025-01287-y

34.

Andrews C D’Souza K Lacey S Black T Patel M Johnson M et al Predicting response to anti-VEGF treatment using EMR data in eyes with neovascular AMD. Presented at: ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress; 2016 Oct 29–Nov 2; Vienna, Austria: Novartis Pharma AG & QuintilesIMS

35.

Sherwin CM de Bie J de Vries TW Conroy EJ de Wildt SN Hooft L et al The use of real-world evidence (RWE) in drug development and regulatory decision making: a review of the literature. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2024) 115(3):617–29. 10.1002/cpt.2971

36.

Kuriakose S Fleming E Goldsack JC Wicks P Bakker JP Schnell M et al Advancing the science of real-world evidence: strengthening regulatory, reimbursement and clinical decision-making. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2022) 111(1):135–43. 10.1002/cpt.2479

37.

Anderson M Naci H Mossialos E . Expanding the role of real-world evidence in the regulatory and post-approval environment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2021) 110(3):559–66. 10.1002/cpt.2309

38.

Sagkriotis A Klitou E Roukis A Theodorou M Michel S Makady A et al Challenges and learnings from applying AI to RWD across ophthalmology, oncology and dermatology. J Med Inform. (2022) 1:e30363. 10.2196/30363

39.

Sheffield KM Peairs KC Wang J Coley RY Dusetzina SB Jiao S et al Replication of randomized clinical trial results using real-world data: paving the way for effectiveness research. Value Health. (2022) 25(2):204–12. 10.1016/j.jval.2021.08.016

40.

Franklin JM Schneeweiss S . When and how can real world data analyses substitute for randomized controlled trials?Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2022) 111(1):130–4. 10.1002/cpt.2475

41.

Obermeyer Z Powers B Vogeli C Mullainathan S . Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. (2019) 366(6464):447–53. 10.1126/science.aax2342

42.

Heaven WD . AI Systems Trained on Poor Data Could Cause Lasting Harm. Cambridge, MA: MIT Technology Review (2020). Available online at:https://www.technologyreview.com

43.

Parikh RB Obermeyer Z Navathe AS . Regulation of predictive analytics in medicine. Science. (2019) 363(6429):810–2. 10.1126/science.aaw0029

44.

Lundberg SM Lee S-I . A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Red Hook, NY: NeurIPS (2017). Available online at:https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/hash/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Abstract.html

45.

Yang G Xu J Zhang C Cai W Gao S Huang P et al Evaluating transparency and bias in AI models in cancer imaging. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2024) 21(1):15–27. 10.1038/s41571-023-00763-4

46.

Garrison LP Jr Neumann PJ Willke RJ Basu A Dubois RW Lakdawalla DN et al A health technology assessment of personalized nutrition interventions using the EUnetHTA core model. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. (2023) 15:17–27. 10.2147/CEOR.S395658

47.

Curzen N Rana B Dwivedi G Redwood S Francis D Rajani R et al Clinical requirements and potential health economic value of a novel computational method for planning coronary interventions. Front Med (Lausanne). (2023) 10:1274688. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1274688

48.

Shamszadeh M Karami H Ghassemi F Karimi N Vahidi H Hosseini SA et al Institutional bias in real-world data: evidence from cancer centers. Cancer Med. (2024) 13(2):874–81. 10.1002/cam4.5927

49.

Myles P Walker M Thomas G Liu Y Schuster T Shaw A et al A health technology assessment of personalised nutrition interventions using the EUnetHTA core model. J Pers Med. (2023) 13(2):203. 10.3390/jpm13020203

50.

Eichler H-G Bloechl-Daum B Abadie E Barnett D Konig F Pearson SD . Bridging the efficacy–effectiveness gap in rare diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2020) 19:833–4. 10.1038/d41573-020-00082-6

51.

Ploug T Holm S . The four dimensions of contestable AI explanations. Philos Technol. (2021) 34:113–34. 10.1007/s13347-019-00399-3

52.

Garrison LP Towse A . A strategy to support efficient development and use of innovations in personalized medicine. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. (2019) 25(10):1083–7. 10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.10.1083

53.

Goldstein CE Henshall C Brown E Martin J Payne K Richards T et al Patient and public involvement and engagement in real-world data and evidence research: a rapid review. Front Med. (2024) 11:1274688. 10.3389/fmed.2024.1274688

54.

Makady A de Boer A Hillege H Klungel O Goettsch W . Using RWE in HTA: from concepts to applications. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2017) 33(5):502–10. 10.1017/S0266462317000634

55.

Franklin JM Pawar A Martin D Franklyn V Bainbridge M Schneeweiss S . Moving transparency in RWE towards RCT standards. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2021) 110(3):563–73. 10.1002/cpt.2290

56.

Makady A ten Ham R de Boer A Hillege H Klungel O Goettsch W . Practice of RWE in decision making. Front Pharmacol. (2019) 10:256. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00256

57.

Hernán MA Robins JM . Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. Am J Epidemiol. (2016) 183(8):758–64. 10.1093/aje/kwv254

58.

Voelker R Krueger H Rosenzweig J Wolff J Arain M Patel C et al Building trust in real-world evidence: moving transparency toward the randomized controlled trial standard. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2023) 113(6):1156–61. 10.1002/cpt.2983

59.

Henshall C Schuller T . HTA and value in personalized healthcare: international perspectives. J Comp Eff Res. (2013) 2(5):453–60. 10.2217/cer.13.56

60.

Richard S Jones D Lee S Ahmed N Patel R Thompson H et al Patient and public involvement and engagement in RWE research. Res Involv Engagem. (2023) 9(1):20. 10.1186/s40900-023-00438-1

61.

Tcheng JE Bakken S Bates DW Bonner S Gandhi TK Glaser J et al Ethical use of data for AI in medicine. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2021) 28(3):489–94. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa262

62.

Tan MJT Kasireddy HR Satriya AB Abdul Karim H AlDahoul N . Health is beyond genetics: on the integration of lifestyle and environment in real-time for hyper-personalized medicine. Front Public Health. (2025) 12:1522673. 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1522673

63.

Wang SV Pinheiro S Hua W Arlett P Uyama Y Berlin JA et al STaRT-RWE: structured template for planning and reporting on the implementation of real-world evidence studies. Br Med J. (2021) 372:m4856. 10.1136/bmj.m4856

64.

Coravos A Goldsack JC Karlin DR Nebeker C Perakslis E Zimmerman N et al Digital medicine: a primer on measurement. Digit Biomark. (2019) 3(2):31–71. 10.1159/000502000

65.

Ribeiro MT Singh S Guestrin C . “Why should I trust you?” explaining the predictions of any classifier. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016 Aug 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. New York: ACM (2016). p. 1135–44. 10.1145/2939672.2939778

Summary

Keywords

real-world evidence, personalized medicine, oncology, ophthalmology, dermatology, artificial intelligence, digital health, health policy

Citation

Sagkriotis A (2025) Real-world evidence and the future of personalized medicine: a global perspective on data, ethics, and equity. Front. Health Serv. 5:1682159. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2025.1682159

Received

08 August 2025

Revised

26 October 2025

Accepted

24 November 2025

Published

08 December 2025

Volume

5 - 2025

Edited by

Liaqat Ali Khan, Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia

Reviewed by

Myles Joshua Toledo Tan, University of Florida, United States

Dario Sacchini, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Sagkriotis.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Alexandros Sagkriotis asagkriotis@gmail.com

ORCID Alexandros Sagkriotis orcid.org/0000-0002-1666-5248

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.