- 1Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 2Oxford Simulation, Teaching, and Research Centre, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 3NHS Education for Scotland, Glasgow, United Kingdom

- 4Centre for Health Innovation, University of Staffordshire, Stafford, United Kingdom

Background: Simulation is a well-established tool for clinical education and has been used to uncover latent safety threats (LSTs) in healthcare settings. However, the extent to which systems theory underpins efforts to detect and mitigate LSTs remains unclear.

Objective: This scoping review explores how healthcare simulations have been used to identify and address LSTs, with particular attention to the visibility and application of systems theory in study design, implementation, and analysis.

Methods: Using PRISMA-ScR, we systematically reviewed studies from 2014 to 2024 across MEDLINE, EMBASE, and grey literature sources. Studies were included if simulation was used with the primary aim of identifying LSTs. Data extraction focused on definitions of LSTs, approaches used to identify and analyse LSTs, response strategies, and the visibility of systems theory.

Results: Sixty-six studies met inclusion criteria. Most (74.2%) used the term “latent safety threat,” though definitions varied. Many studies lacked explicit detail on how LSTs were identified (33.3%) or analysed (41.8%). Systems theory was applied with varying visibility: 36.4% showed unclear or no visibility, 43.9% showed partial visibility, and 19.7% showed full visibility. While 80.3% described actions to address LSTs, approaches ranged from one-off fixes to structured quality improvement strategies. Case studies illustrate best practices and opportunities for improvement in theoretical transparency.

Conclusions: Simulation is a valuable method for identifying LSTs, but inconsistent application of systems theory and variable methodological transparency limit learning and generalisability. Future research should make theoretical underpinnings explicit, define terminology clearly, and align simulation design with both educational and organisational improvement goals.

Introduction

Identifying safety issues only after patient or staff harm is not uncommon. Traditional approaches to safety improvement, such as root cause analyses, often start with the harm. While these investigations can be helpful, there are often indicators of issues in day-to-day work which, if mitigated, could prevent harm from occurring in the first place (1). These issues are labelled as “latent safety threats” (LST), or “previously unrecognised system-based conditions that under certain circumstances manifest and threaten patient safety” (2). Simulation has been widely used to identify LSTs in various settings, such as emergency (3), paediatrics (4) and obstetrics (5). Studies that have used simulation to identify LSTs report a myriad of LSTs found and addressed, suggesting that the method can facilitate significant strides towards safer care. However, the approaches used to identify LSTs, and the influence of each on the nature of LSTs uncovered, remains unclear.

A recent review published by Grace and O’Malley was an important first step in better understanding how simulation has been used to identify LSTs in emergency settings (6). Authors highlighted wide-ranging methods used, detail provided, and the number and nature of LSTs identified. The study also revealed many studies were quality improvement (QI) initiatives, which aims to use existing knowledge to improve local systems, rather than research, which aims to produce new knowledge. These findings suggest that the degree to which the theory informs and is visible in simulation research is variable and impacts the LSTs identified.

In all qualitative research, the choice of method, data collection, sense making, and interpretation are influenced by the researcher's subjectivity and can impact the results (7). Theoretical visibility ensures the researcher's assumptions and rationale are made explicit and can determine the extent to which the findings are transferable. Because resources are limited in nearly all settings, there is a clear incentive to ensure that opportunities for safety learning yield the greatest insight. The use of systems theory has been shown to enhance clinical systems and therefore improve patient outcomes. In this paper, “systems theory” was defined as a way of understanding work that recognises how multiple elements interact to impact processes and outcomes, characterised by interactions between system factors, emergence, and feedback loops (8, 9). Thus far, the extent to which system theory has been used in the design of simulations to identify LSTs is unknown but could significantly impact the insights generated.

The 2023 Grace and O'Malley review was a significant step toward better understanding the potential for simulation to uncover LSTs. We intend to build on their review by examining the degree of theoretical visibility in the design, implementation and evaluation of simulations used to identify LSTs in all clinical areas. Additionally, we aim to understand the extent to which systems theory informed how the LSTs were addressed.

The key question for this work was “How has systems theory been used to identify, analyse, and address LSTs in healthcare simulations?”. The aims included:

1. Explore approaches previously used to identify and analyse LSTs in healthcare simulations.

2. Describe the extent of systems theory visibility in previous work.

3. Understand how uncovered LSTs have been addressed.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in five stages using the guidance from Levac and colleagues (2010) and the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (10, 11). The research question was developed by safety experts, which guided the selection of the relevant studies. The study selection process was iterative and involved refining the search strategy and selection criteria with the research team. The extraction template was developed with the full team in alignment with the aims and was iterated based on discussion. Results were reported according to the overarching question and interpreted in comparison with previous literature.

Protocol and registration

This scoping review protocol has not been registered on PROSPERO, as scoping review protocols were not accepted by PROSPERO at the time of this review.

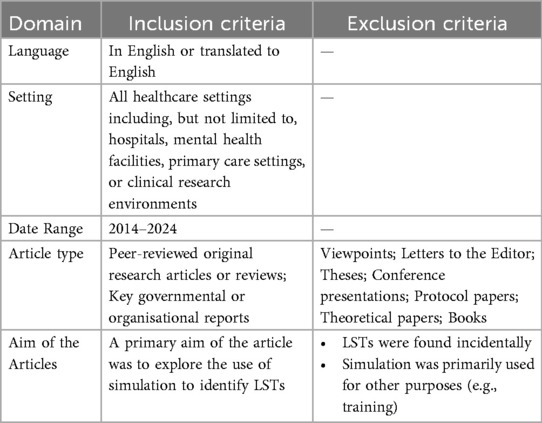

Eligibility criteria

See eligibility criteria below (Table 1).

Information sources and search strategy

EMBASE and MEDLINE were used to identify relevant publications that have applied simulation to identify LSTs in any healthcare context. Search terms used were based on previous literature and discussion with content experts. Search terms relating to this concept were iteratively developed in partnership with a librarian. Medical Subject Headings and free-text terms were searched. The librarian provided guidance on truncation and modification of the search terms as appropriate. See Supplementary Material 1: Searches.

Grey literature sources were identified based on librarian recommendations and discussions among the author group. Grey literature search strategies included backward citation tracking and searching websites of relevant organisations and journals.

Data management and initial screening

Search results were stored in EndNote reference manager. After deduplication, results were moved into Rayyan™, a software for abstract screening and initial and full text review. 10% of articles were screened by both blinded reviewers independently and then discussed and reconciled. Thereafter, inclusion and exclusion criteria were further specified and remaining titles and abstracts were screened independently by both blinded researchers. Disagreements were reconciled between reviewers.

Full text screening and data extraction

Articles from the initial screening were moved into Excel for full text review. Each article was screened by both reviewers independently. Authors then conducted an inductive analysis of all articles in the first review. Findings and disagreements were discussed among the research team. Based on the findings from the inductive analysis, an extraction template was co-designed by two independent researchers. All articles were re-reviewed using the extraction template. Core details were extracted from all included articles, per the extraction template below.

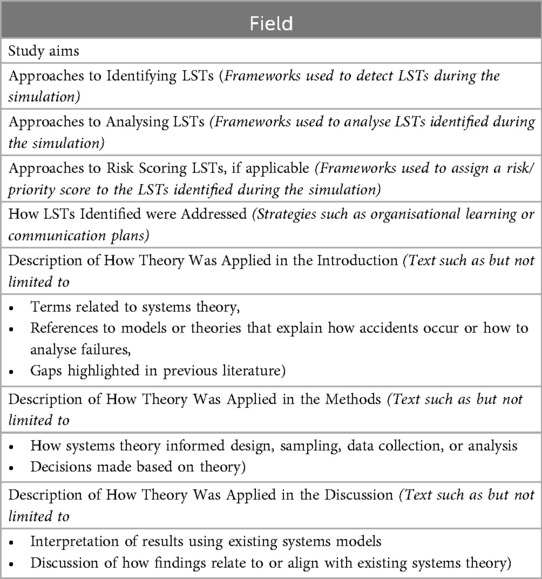

Extraction template

See extraction template below (Table 2).

Data synthesis

Data were analysed qualitatively and quantitatively. Quantitative synthesis consisted of categorical representation of the terms used to describe LSTs. Approaches to identify, analyse, and risk score LSTs were extracted and analysed quantitatively. The extent of theoretical visibility was determined inductively and was informed by previous work on theoretical visibility in qualitative research more broadly (7, 12). Case studies were used to illustrate examples of strong visibility of systems theory and opportunities for improvement.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not required for this study, as primary data collection is not being conducted.

Results

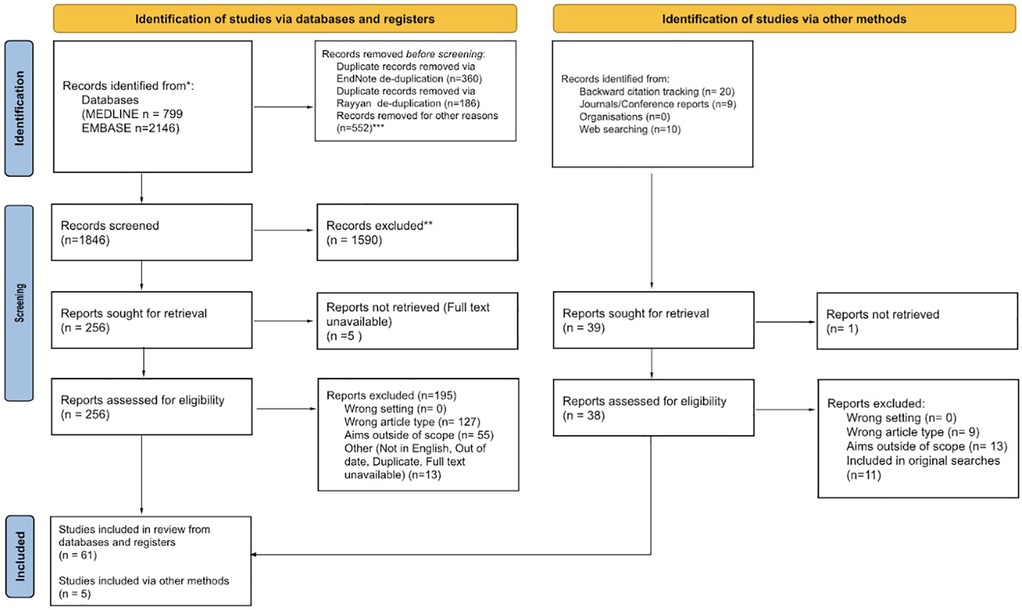

Flow diagram of articles returned

See Figure 1 for flow diagram of articles returned.

Synthesis of results

Terminology

74.2% (49/66) articles used “Latent Safety Threat” when describing unrecognised risks the simulation aimed to uncover. Other terms included “Latent Threat” (4/66, 6.1%), “Hazard” (3/66, 4.5%), “Latent Error” (2/66, 3.0%), “Error” (2/66, 3.0%), “Failure Mode” (2/66, 3.0%), and “Safety Issues” (1/66, 1.5%). The term used was unclear in 1.5% of articles.

Definitions used for “latent safety threat”

63% (31/49) papers that used “latent safety threat” explicitly provided a definition. Many used the definition provided by Patterson and colleagues (2): “system-based threats to patient safety that can materialise at any time and are previously unrecognised by healthcare providers, unit directors, or hospital administration” (13–21). Nine authors specified LSTs as problems in the system (3, 22–24) or design (25–30) that could contribute to harm. Eleven authors characterised LSTs by preventability (31, 32), their unintentional nature (33, 34), significance (34, 35), or visibility using terms like “hidden” or “dormant” (31, 32, 35, 36). Kaba and Barnes (2019) and Bloomfield and colleagues (2020) described LSTs with temporal language such as “..once [a new] facility opens” (34) or “..not identified during routine patient care” (5). Broader definitions, such as “conditions that may risk patient safety” (37) and “unrecognised safety issues that impact patient outcomes” (38, 39) were also used. Arul and colleagues (2021) described LSTs not as risks but rather “improvement goals identified during simulation that have an impact on delivery of optimal care” (40).

Approaches used to identify LSTs

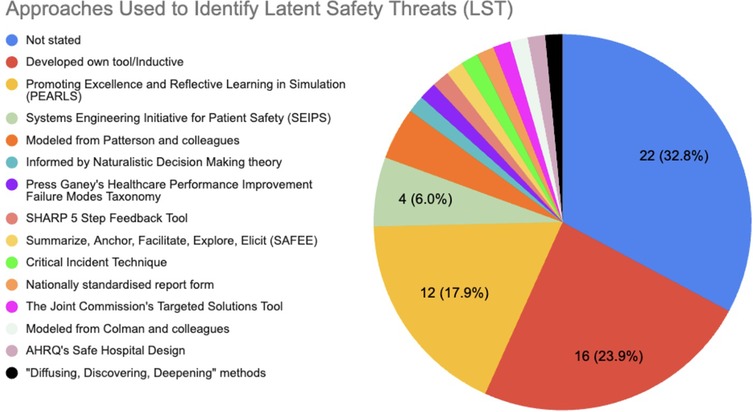

Several approaches were used to identify LSTs, with some authors using more than one approach. 33.3% (22/66) did not state the approach(es) used to identify LSTs. 24.2% (16/66) authors developed their own approach inductively and 18.2% (12/66) followed the Promoting Excellence and Reflective Learning in Simulation (PEARLS) framework (41). See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Approaches used to identify latent safety threats (LSTs). Most (32.8%, 22/66) did not state the approaches used to identify LSTs. Several (23.9%, 16/66) created their own approach. Various other tools and frameworks were used, including the Promoting Excellence and Reflective Learning in Simulation (PEARLS) and Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS).

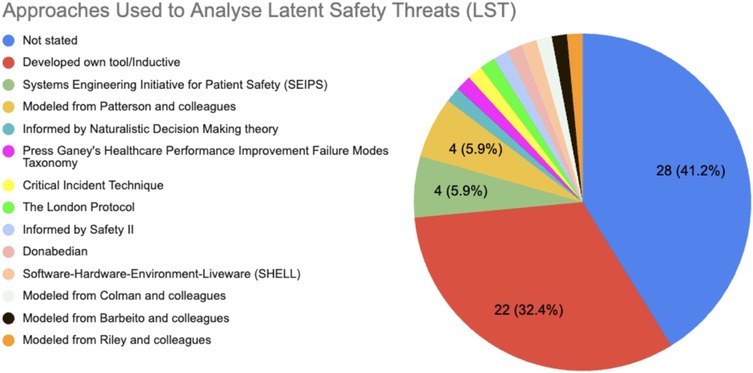

Approaches used to analyse LSTs

41.8% (28/66) did not clearly state how they analysed LSTs. If there was not a clear distinction in the approaches used for identification vs. analysis, or authors did not clearly state that one approach was used for both identification and analysis, the approach was categorised according to how the current authors thought it was primarily used. Inductive development of a bespoke tool was the most common approach (33.3%, 22/66), followed by use of approaches from Patterson and colleagues (2) (6.1%, 4/66) and Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) (6.1%, 4/66) (2, 8). See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Approaches used to analyse latent safety threats (LSTs). Many did not state the approaches or frameworks used to analyse LSTs found (41.8%, 28/66) or developed their own approach (32.4%, 22/66).

Visibility of system theory

The visibility of system theory was developed based on an inductive review of the included papers. Three categories were identified: Limited visibility, partial visibility, and full visibility. Limited visibility was defined as an absence of systems theory in the study. Partial visibility was defined as inconsistent or implicit use of systems theory. Full visibility was defined as the use of theory to influence the full study.

24 (36.3%) studies were categorised as “unclear/no visibility of systems theory”. 29 (43.9%) studies were categorised as “partial visibility of systems theory”. 13 (19.7%) studies were categorised as “full visibility of systems theory”.

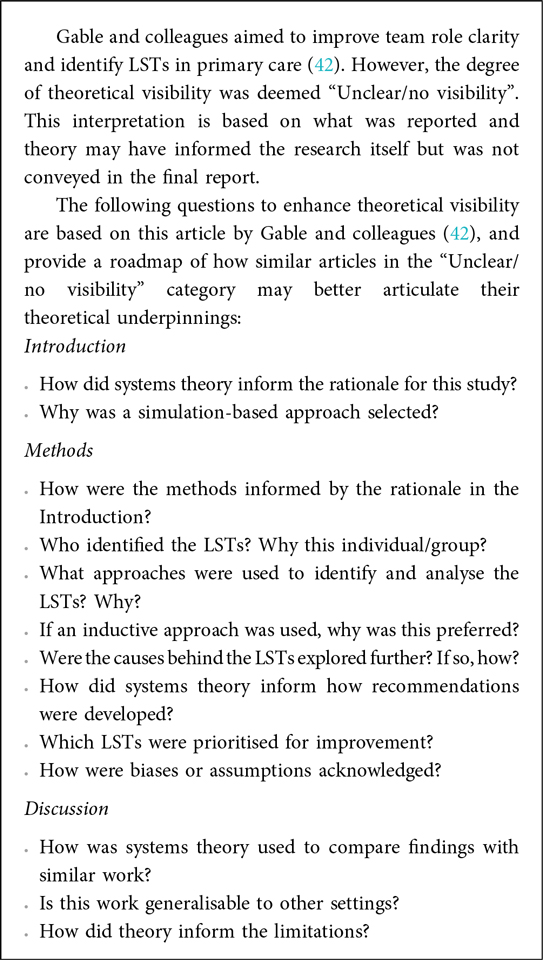

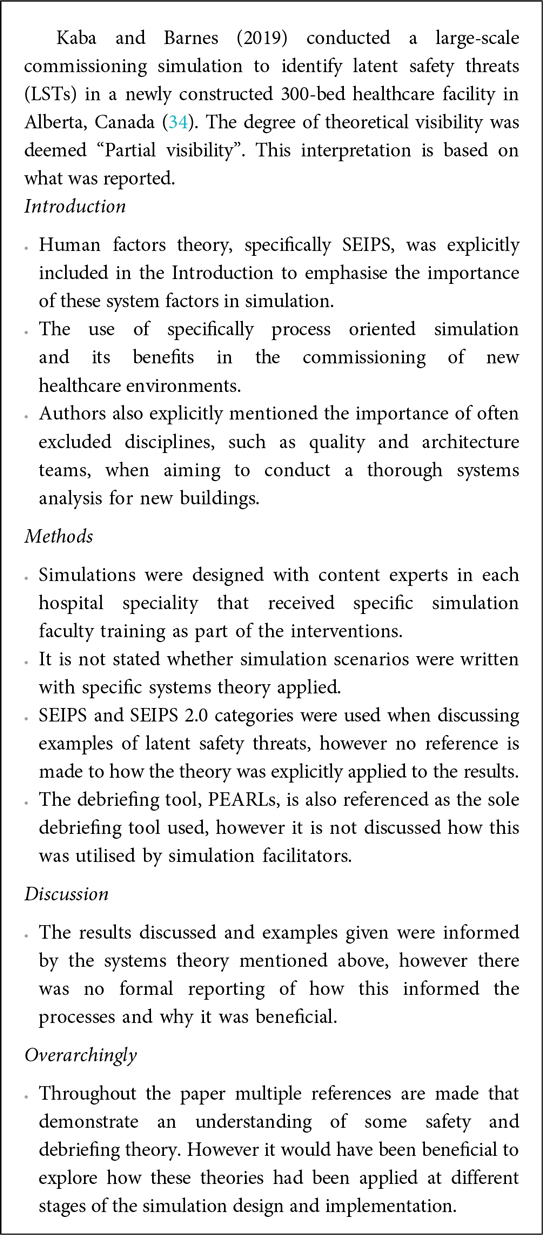

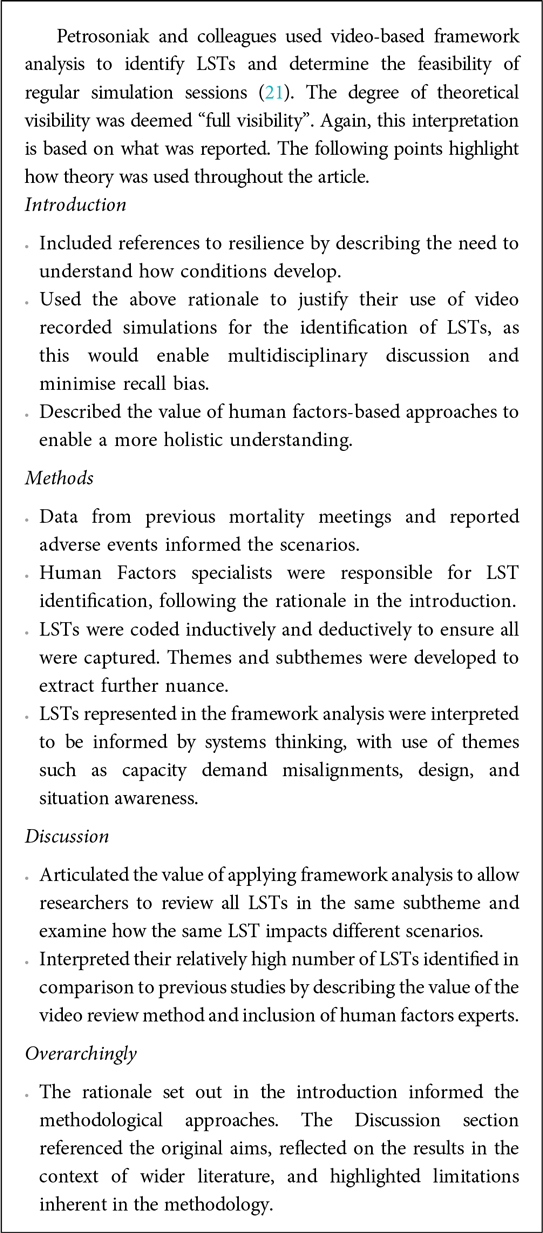

Case studies: visibility of systems theory

Quantitative analysis revealed a broad spectrum of degrees of visibility of systems theory in the articles reviewed. The three case studies below expand on the quantitative categorisation to better understand how theory was used to inform research decisions and where opportunities for improvement exist. Case study 1 illustrates an example of unclear/no visibility of systems theory. Case study 2 illustrates an example of partial visibility of systems theory. Case study 3 illustrates an example of full visibility of systems theory (see Boxes 1–3).

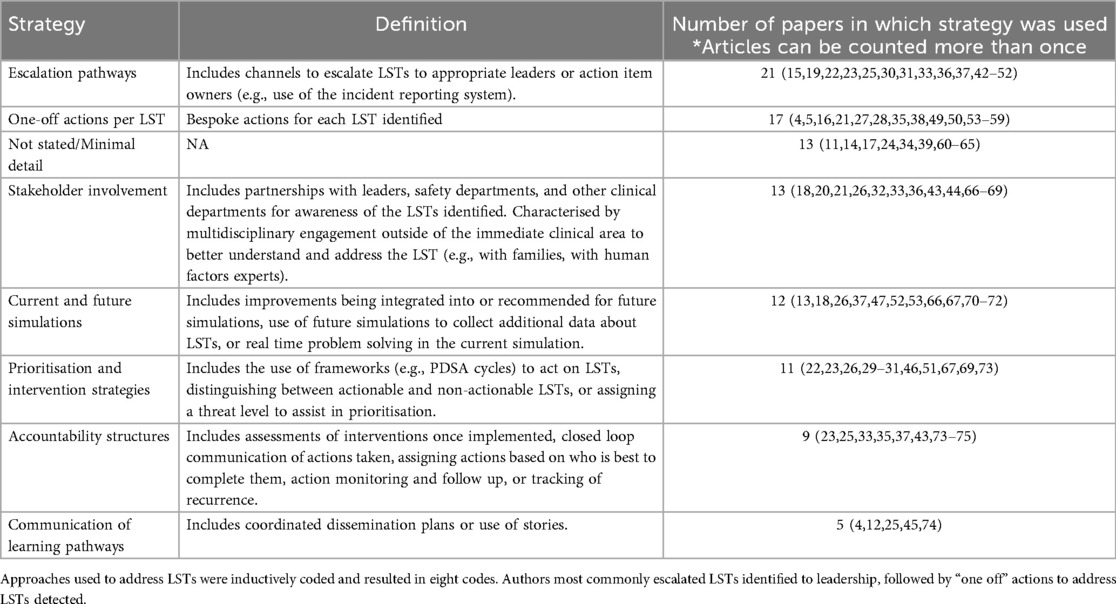

Strategies to address LSTs

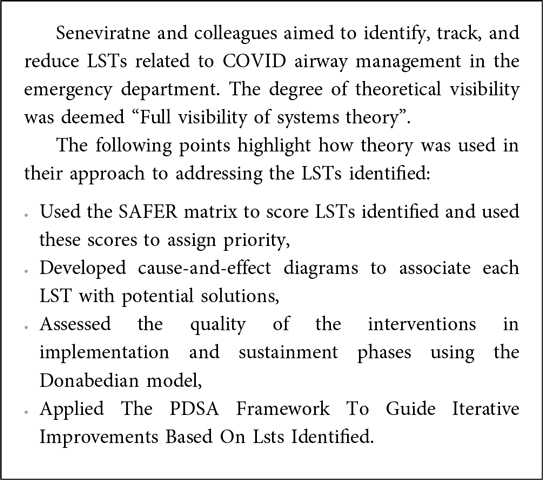

80.3% (53/66) of articles described strategies to address the LSTs identified. Strategies varied from one-off actions to more robust strategies such as accountability structures. Strategies to address LSTs identified were inductively coded with a resultant eight codes. These strategies, along with their definitions and the number of papers, are described in Table 3. See case study 4 for an illustration of the use of systems theory to address LSTs in healthcare.

Risk scoring LSTs

Some authors risk scored the LSTs without clearly stating how these risk scores were used to address the LSTs [hence the discrepancy between the articles that risk scored the LSTs (14) and the articles that applied “Prioritisation and intervention strategies” to address LSTs (11)]. Of the 14 articles that risk scored the LSTs identified, five (35.7%) used Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) methodology (43), followed by Healthcare Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (HFMEA) (4/14, 28.6%) (44), inductive approaches (3/14, 21.4%), the Survey Analysis for Evaluating Risk (SAFER) matrix (1/14, 7.1%) (45), and adoption of the approach from Dadiz and colleagues (1/14, 7.1%) (38) (see Box 4).

Discussion

Summary of evidence

The current review aimed to understand how systems theory has been used to identify LSTs in simulation. We found a variety of terms used instead of “latent safety threat”. A number of the papers reviewed did not explicitly state how they identified or analysed LSTs. 80.3% described how the LSTs uncovered were addressed. Several developed “one off” solutions for each LST without explaining how these solutions were developed. Of those that included risk scoring as an approach to address LSTs, various risk scoring tools were used. Finally, there was a broad spectrum of the degree of theoretical visibility. A case study of robust practice is included, as well as reflective questions for future researchers to consider to improve their own theoretical visibility.

Strengths and limitations

All papers underwent initial screening and full text review by two researchers with 40.0% of the papers undergoing extraction by two researchers. Disagreements were discussed and adjustments were made as needed.

Several papers did not meet our inclusion criteria but may be valuable to consider for future research. For example, there were many papers in which LSTs were incidental findings, the aim of the simulation was to “test” how risky known LSTs actually were (rather than uncovering unknown LSTs), or in which the simulation was used to train other staff members to identify LSTs themselves.

Comparison with existing literature

We support Grace and O’Malley's assertion that many of the “research” studies in this area take on a QI, rather than research, angle (6). Many studies in this review were interpreted to be QI (46). Any intention to report a QI project must be overtly stated, as QI aims to improve the local context using existing evidence and does not aim to produce new knowledge.

If the intention is to conduct research, theoretical transparency is essential. Lack of theoretical clarity can overlook assumptions or errors in logic (47), lead to a disconnect between intervention components (47), and reduce transferability (48). While theory may have been used in the research itself, it should be explicit in the written research output. The case studies illustrate key questions that should be addressed for robust theoretical transparency for future studies aiming to use simulation to address LSTs. Overarchingly, a response to “To what extent are the questions, approaches, and interpretations congruent with one another through a theoretical paradigm?” should be clearly articulated.

Several authors do not state how they identified or analysed LSTs. Without clear reporting of methodology, it becomes difficult to determine the extent to which LSTs identified were the result of robust approaches or the result of serendipitous observations. Many articles appeared to exemplify quantitative-dominant thinking in that authors seemed to aim to objectively confirm the presence of LSTs without acknowledging theoretical underpinnings or biases in “what they were seeing” (7). Therefore, there is a risk of oversimplifying complex healthcare systems, chalking up LSTs to isolated incidents of error (rather than exploring the complex interactions that influence safety) and developing solutions that are not likely to reliably address the problem.

How a problem is framed influences the approach to resolving it and the potential for learning (49, 50). Without the application of systems and Just Culture (51) approaches, LSTs are more likely to be attributed to individual non-compliance. This leads to solutions focussed on modifying individual behaviour. Therefore, the moral responsibility is to implement reliable, system-based solutions that address LSTs at their root, rather than relying on interventions directed at individuals.

Finally, the variety in terms used can complicate comparison of LSTs over time or between settings. The terminological precision problem is not new in the patient safety space. For example, there has been a longstanding advocacy for greater precision in the terms “adverse event” and “medication error” (52, 53). While organisations have published taxonomies, how this guidance is used in practice remains unclear (53–55). The terminological precision is likely to become even more pressing as simulation becomes an important component of safety work.

Implications for policy, education, practice and research

Identifying one term to use may not be feasible, given that contexts may have different needs. However, academics should explicitly identify the terminology used, its definition, and why it was selected to help trace origins of terms and enable greater comparison. Publishers should reinforce this expectation upon receiving papers related to this topic. Similarly, publishers should assess the degree of theoretical visibility in papers submitted to peer-reviewed journals and highlight examples of good practice. Using probing questions, developing templates, and providing examples can steer the degree of theoretical visibility expected of future research. Future researchers should consider increased precision in their data extraction. Some tools [e.g., SEIPS (8)] are more directly aimed at identifying LSTs whereas others [e.g., PEARLS (41)] provide the conditions for groups to discuss the LSTs but were not designed specifically to detect LSTs. Defining which tools are most appropriate based on the aim may better refine the findings.

Organisations should integrate simulation into the larger safety learning strategy. Historically, safety learning has been characterised by incident reports and investigations once a harm event has occurred. Techniques that provide additional insight into LSTs, such as simulation, could be further integrated into traditional safety strategies by encouraging reporting of LSTs identified in simulation in the normal event report systems or allocating safety resources to facilitate simulation debriefs, for example. Many of the papers reviewed “stumbled upon” LSTs, which is a testament to the benefit of systems testing via simulation. Simulation leaders should be aware that LSTs may be unexpectedly detected and should have an established process to escalate these LSTs to groups that will be able to help. A significant challenge arises from the fact that simulation often resides within the “education” division of healthcare organisations, rather than also being integrated into the “safety” division. This division can create barriers to leveraging simulation for system-level improvements. Bridging this gap might be achieved by aligning simulation efforts with organisational priorities and designing simulations for both education and systems improvement.

It is important to make recommendations to mitigate LSTs identified but further resources must be allocated to refine the solution once the LST is identified (56). Organisations conducting simulations should embed clear guidance to help translate LSTs into solutions (56). Those with safety expertise should be involved in simulation design, data collection and analysis, and recommendation generation. These professionals can serve as the “glue” between the simulation and larger organisational work.

Many articles involved high-fidelity simulations, which are costly and may disproportionately report on findings from high-income countries. There is a gap in the literature around how lower fidelity simulations can be used to identify LSTs in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). However, certain costly aspects of the simulation, such as conceptualisation, do not need to be created in silos. Making scenarios, written materials, and data collection tools publicly available so that they can be adapted in other contexts could minimise the barriers to engagement for those in LMIC.

Conclusion

This review has revealed the extensive use of simulation to aid in the identification of LSTs. Simulation practitioners should aim to make explicit their use of systems theory when designing simulations to identify LSTs and be prepared for the likelihood of identifying LSTs incidentally. Researchers should overtly state how theory informed their study. Theoretical transparency is likely to enhance the transferability of approaches and findings to other contexts, which is of particular value in settings where resources for simulation are scarce.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

OL: Project administration, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis. AT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation. JW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. PB: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis. HH: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2025.1682629/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Macrae C. Early warnings, weak signals and learning from healthcare disasters. BMJ Qual Saf. (2014) 23(6):440–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002685

2. Patterson MD, Geis GL, Falcone RA, LeMaster T, Wears RL. In situ simulation: detection of safety threats and teamwork training in a high risk emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. (2013) 22(6):468–77. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000942

3. Bentley SK, Meshel A, Boehm L, Dilos B, McIndoe M, Carroll-Bennett R, et al. Hospital-wide cardiac arrest in situ simulation to identify and mitigate latent safety threats. Adv Simul Lond Engl. (2022) 7(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s41077-022-00209-0

4. Colvin D, Gallagher S, Marcus S, Fitzpatrick G, Milliken I, Thompson A, et al. Theatre LISTS: learning from incidents, finding safety threats with simulation. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. (2020) 6(5):308–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjstel-2019-000538

5. Bloomfield V, Ellis S, Pace J, Morais M. Mode of delivery: development and implementation of an Obstetrical in situ simulation program. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. (2020) 42(7):868–73.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.12.011

6. Grace MA, O’Malley R. Using in situ simulation to identify latent safety threats in emergency medicine: a systematic review. Simul Healthc J Soc Simul Healthc. (2024) 19(4):243–53. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000748

7. Collins CS, Stockton CM. The central role of theory in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. (2018) 17(1):1609406918797475. doi: 10.1177/1609406918797475

8. Carayon P, Wooldridge A, Hoonakker P, Hundt AS, Kelly MM. SEIPS 3.0: human-centered design of the patient journey for patient safety. Appl Ergon. (2020) 84:103033. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.103033

9. Carayon P, Hundt AS, Karsh B, Gurses AP, Alvarado CJ, Smith M, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. (2006) 15(Suppl 1):i50–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842

10. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. (2010) 5(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

11. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

12. Bradbury-Jones C, Herber OR, Miller R, Taylor J. Improving the visibility and description of theory in qualitative research: the QUANTUM typology. SSM Qual Res Health. (2022) 2:100030. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2021.100030

13. Greer JA, Haischer-Rollo G, Delorey D, Kiser R, Sayles T, Bailey J, et al. In situ interprofessional perinatal drills: the impact of a structured debrief on maximizing training while sensing patient safety threats. Cureus. (2019) 11(2):e4096. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4096

14. Argintaru N, Li W, Hicks C, White K, McGowan M, Gray S, et al. An active shooter in your hospital: a novel method to develop a response policy Using in situ simulation and video framework analysis. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2021) 15(2):223–31. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.161

15. Gray A, Chartier LB, Pavenski K, McGowan M, Lebovic G, Petrosoniak A. The clock is ticking: using in situ simulation to improve time to blood administration for bleeding trauma patients. Can J Emerg Med. (2021) 23(1):54–62. doi: 10.1007/s43678-020-00011-9

16. Shrestha A, Sonnenberg T, Shrestha R. COVID-19 emergency department protocols: experience of protocol implementation through in situ simulation. Open Access Emerg Med. (2020) 12:293–303. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S266702

17. Shrestha R, Shrestha AP, Shrestha SK, Basnet S, Pradhan A. Interdisciplinary in situ simulation-based medical education in the emergency department of a teaching hospital in Nepal. Int J Emerg Med. (2019) 12(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12245-019-0235-x

18. Kjaergaard-Andersen G, Ibsgaard P, Paltved C, Irene Jensen H. An in situ simulation program: a quantitative and qualitative prospective study identifying latent safety threats and examining participant experiences. Int J Qual Health Care. (2021) 33(1):mzaa148. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa148

19. Rusiecki D, Walker M, Douglas SL, Hoffe S, Chaplin T. Multiprofessional perspectives on the identification of latent safety threats via in situ simulation: a prospective cohort pilot study. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. (2021) 7(2):102–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjstel-2020-000621

20. Mileder LP, Schwaberger B, Baik-Schneditz N, Ribitsch M, Pansy J, Raith W, et al. Sustained decrease in latent safety threats through regular interprofessional in situ simulation training of neonatal emergencies. BMJ Open Qual. (2023) 12(4):e002567. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2023-002567

21. Petrosoniak A, Fan M, Hicks CM, White K, McGowan M, Campbell D, et al. Trauma resuscitation Using in situ simulation team training (TRUST) study: latent safety threat evaluation using framework analysis and video review. BMJ Qual Saf. (2021) 30(9):739–46. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011363

22. Lawrence JF, Tsang R, Fedee G, Musick MA, Lichliter RL, Bastero P, et al. Prevention of latent safety threats: a quality improvement project to mobilize a portable CT. Pediatr Qual Saf. (2021) 6(4):e422. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000422

23. Zimmermann K, Holzinger IB, Ganassi L, Esslinger P, Pilgrim S, Allen M, et al. Inter-professional in situ simulated team and resuscitation training for patient safety: description and impact of a programmatic approach. BMC Med Educ. (2015) 15:189. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0472-5

24. Colman N, Stone K, Arnold J, Doughty C, Reid J, Younker S, et al. Prevent safety threats in new construction through integration of simulation and FMEA. Pediatr Qual Saf. (2019) 4(4):e189. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000189

25. Carmichael H, Mastoras G, Nolan C, Tan H, Tochkin J, Poulin C, et al. Integration of in situ simulation into an emergency department code orange exercise in a tertiary care trauma referral center. AEM Educ Train. (2021) 5(2):e10485. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10485

26. Congenie K, Bartjen L, Gutierrez D, Knepper L, McPartlin K, Pack A, et al. Learning from latent safety threats identified during simulation to improve patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. (2023) 49(12):716–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2023.08.003

27. Kennedy C, Sycip M, Woods S, Ell L. A novel approach to emergency department readiness for airborne precautions using simulation-based clinical systems testing. Ann Emerg Med. (2023) 81(2):126–39. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.08.015

28. Kennedy C, Doyle NM, Pedigo R, Toy S, Stoner A. A novel approach to operating room readiness for airborne precautions using simulation-based clinical systems testing. Paediatr Anaesth. (2022) 32(3):462–70. doi: 10.1111/pan.14386

29. Gibbs K, DeMaria S, McKinsey S, Fede A, Harrington A, Hutchison D, et al. A Novel in situ simulation intervention used to mitigate an outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. (2018) 194:22–7.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.10.040

30. Long JA, Webster CS, Holliday T, Torrie J, Weller JM. Latent safety threats and countermeasures in the operating theater: a National in situ simulation-based observational study. Simul Healthc J Soc Simul Healthc. (2022) 17(1):e38–44. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000547

31. Mastoras G, Poulin C, Norman L, Weitzman B, Pozgay A, Frank JR, et al. Stress testing the resuscitation room: latent threats to patient safety identified during Interprofessional in situ simulation in a Canadian academic emergency department. AEM Educ Train. (2020) 4(3):254–61. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10422

32. Mastoras G, Poulin C, Norman L, Weitzman B, Pozgay A, Frank JR. Stress-testing the resuscitation room: latent threats to patient safety identified during interprofessional in situ simulation in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. (2016) 18:S45. doi: 10.1017/cem.2016.81

33. Fuselli T, Raven A, Milloy S, Barnes S, Dube M, Kaba A. Commissioning clinical spaces during a pandemic: merging methodologies of human factors and simulation. HERD. (2022) 15(2):277–92. doi: 10.1177/19375867211066933

34. Kaba A, Barnes S. Commissioning simulations to test new healthcare facilities: a proactive and innovative approach to healthcare system safety. Adv Simul Lond Engl. (2019) 4:17. doi: 10.1186/s41077-019-0107-8

35. Uttley E, Suggitt D, Baxter D, Jafar W. Multiprofessional in situ simulation is an effective method of identifying latent patient safety threats on the gastroenterology ward. Frontline Gastroenterol. (2020) 11(5):351–7. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101307

36. Shah S, McGowan M, Petrosoniak A. Latent safety threat identification during in situ simulation debriefing: a qualitative analysis. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. (2021) 7(4):194–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjstel-2020-000650

37. Couto TB, Barreto JKS, Marcon FC, Mafra ACCN, Accorsi TAD. Detecting latent safety threats in an interprofessional training that combines in situ simulation with task training in an emergency department. Adv Simul Lond Engl. (2018) 3:23. doi: 10.1186/s41077-018-0083-4

38. Dadiz R, Riccio J, Brown K, Emrich P, Robin B, Bender J. Qualitative analysis of latent safety threats uncovered by in situ simulation-based operations testing before moving into a single-family-room neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. (2020) 40(1):29–35. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-0749-3

39. Poor AD, Acquah SO, Wells CM, Sevillano MV, Strother CG, Oldenburg GG, et al. Implementing automated prone ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome via simulation-based training. Am J Crit Care. (2020) 29(3):e52–59. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2020992

40. Arul N, Ahmad I, Hamilton J, Sey R, Tillson P, Hutson S, et al. Lessons learned from a collaborative to develop a sustainable simulation-based training program in neonatal resuscitation: simulating success. Child Basel Switz. (2021) 8(1):39. doi: 10.3390/children8010039

41. Eppich W, Cheng A. Promoting excellence and reflective learning in simulation (PEARLS): development and rationale for a blended approach to health care simulation debriefing. Simul Healthc. (2015) 10(2):106. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000072

42. Gable BD, Hommema L. In situ simulation in interdisciplinary family practice improves response to in-office emergencies. Cureus. (2021) 13(4):e14315. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14315

43. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) tool (2017). Available online at: https://www.ihi.org/resources/tools/failure-modes-and-effects-analysis-fmea-tool (Accessed October 15, 2024).

44. DeRosier J, Stalhandske E, Bagian JP, Nudell T. Using health care failure mode and effect analysis: the VA national center for patient safety’s prospective risk analysis system. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. (2002) 28(5):248–67; 209. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28025-6

45. Joint Commission International. SAFER matrix scoring process fact sheet (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/fact-sheets/facts-about-safer-matrix-scoring-process/ (Accessed October 15, 2024).

46. Bass PF, Maloy JW. How to determine if a project is human subjects research, a quality improvement project, or both. Ochsner J. (2020) 20(1):56–61. doi: 10.31486/toj.19.0087

47. Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. (2015) 24(3):228–38. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627

48. Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. (2014) 23(4):290–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862

49. Martin G, Ozieranski P, Leslie M, Dixon-Woods M. How not to waste a crisis: a qualitative study of problem definition and its consequences in three hospitals. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2019) 24(3):145–54. doi: 10.1177/1355819619828403

50. Donaldson L. An organisation with a memory. Clin Med Lond Engl. (2002) 2(5):452–7. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.2-5-452

51. Dekker S. Just Culture: Restoring Trust and Accountability in Your Organization. 3rd ed. London: Routledge & CRC Press (2016). Available online at: https://www.routledge.com/Just-Culture-Restoring-Trust-and-Accountability-in-Your-Organization-Third-Edition/Dekker-Dekker/p/book/9781472475787 (Accessed October 15, 2024).

52. Biro J, Rucks M, Neyens DM, Coppola S, Abernathy JH, Catchpole KR. Medication errors, critical incidents, adverse drug events, and more: a review examining patient safety-related terminology in anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. (2022) 128(3):535–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.11.038

53. Wahr JA, Nanji KC, Merry AF. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet: defining patient safety-related terminology. Br J Anaesth. (2022) 128(4):605–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.01.028

54. Chang A, Schyve PM, Croteau RJ, O’Leary DS, Loeb JM. The JCAHO patient safety event taxonomy: a standardized terminology and classification schema for near misses and adverse events. Int J Qual Health Care. (2005) 17(2):95–105. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi021

55. AHRQ. Adverse events, near misses, and errors (2022). Available online at: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/adverse-events-near-misses-and-errors (Accessed October 15, 2024).

56. CIEHF. Learning from adverse events (2020). Available online at: https://ergonomics.org.uk/resource/learning-from-adverse-events.html (Accessed January 15, 2025).

Keywords: healthcare simulation, patient safety, safety risks, system engineering, latent safety threats, quality improvement

Citation: Lounsbury O, Tomlinson A, Wakeling J, Bowie P and Higham H (2025) The use of healthcare simulation to identify and address latent safety threats: a scoping review. Front. Health Serv. 5:1682629. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2025.1682629

Received: 9 August 2025; Accepted: 24 September 2025;

Published: 18 November 2025.

Edited by:

Robyn Clay-Williams, Macquarie University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Jane Torrie, University of Auckland, New ZealandMary Patterson, University of Florida, United States

Copyright: © 2025 Lounsbury, Tomlinson, Wakeling, Bowie and Higham. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olivia Lounsbury, b2xpdmlhLmxvdW5zYnVyeUBuZHMub3guYWMudWs=

Olivia Lounsbury

Olivia Lounsbury Ashley Tomlinson

Ashley Tomlinson Judy Wakeling3

Judy Wakeling3 Paul Bowie

Paul Bowie Helen Higham

Helen Higham