Abstract

Vision health is a critical yet often overlooked component of comprehensive primary care, particularly for underserved populations. Patient access to eye care services enhances workplace productivity, household income, and employment opportunities, ultimately supporting economic growth, poverty reduction, and food security. Community Health Centers (CHC) collectively serve over 32 million patients annually and are uniquely positioned to address disparities in eye care access. Yet only 26% of CHCs offer vision care services, and only 2.9% of people who access CHC services receive eye care. Addressing this gap requires a strategic, systems-level approach to implementation. This perspective proposes an integrated framework to guide the sustainable and equitable integration of eye care providers, including optometrists and ophthalmologists, into Community Health Centers (CHCs). Drawing on and uniting the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Research Framework, and the National Association of Community Health Centers' (NACHC) Value Transformation Framework (VTF), we outline a multi-level strategy that addresses implementation readiness, equity, and sustainability. This integrated framework is intended to inform implementation research and policy development aimed at making on-site eye care via an optometrist or ophthalmologist a mandated service in CHCs nationwide. In doing so, we offer an actionable game plan for CHC leaders, healthcare administrators, and public health advocates to expand access to comprehensive eye care in underserved communities.

Introduction

Eye health and vision loss are critical public health issues that disproportionately affect underserved populations (1, 2), including those served by Community Health Centers (CHCs). Despite national initiatives such as Healthy People 2030, access to eye care remains limited for rural, racially and ethnically minoritized, and low-income communities (2–5). As a result, conditions such as glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and uncorrected refractive error are more prevalent in these groups (6–10), with Black patients experiencing blindness rates two to four times higher than their White counterparts (7, 8).

Community Health Centers (CHC), which include Federally Qualified Health Centers that receive federal funding under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (11), are designed to address health disparities by providing comprehensive, community-based primary care to medically underserved populations. CHCs collectively serve over 32 million patients annually (12), providing essential services including primary and pediatric care, behavioral health, dental, pharmacy, substance use counseling, and immunizations, among others (13). This makes them uniquely positioned to address disparities in eye care access. Given the broad and compelling evidence documenting the value of CHCs, CHCs have traditionally received significant bipartisan support for their efforts (14–20).

Despite their mission, most CHCs do not offer on-site eye care services. The proportion of CHCs with vision care services decreased from 32% to 26% between 2021 and 2023, and only 2.9% of patients receiving care in CHCs received any form of eye care in 2023 (21–24). Barriers to integrating eye care services into CHCs include the need for assistance with creating a business plan for understanding billing and reimbursement, designing the space, and compiling an inventory of eye care equipment (21). Systemic barriers to providing vision care at CHCs include a shortage of eye care clinicians, limited funding and space for equipment, and complex implementation processes (25). Inadequate or complex reimbursement, competing health priorities, and low patient follow-up rates further hinder sustainable vision services (25, 26). However, systemic approaches to identifying, addressing, categorizing, and processing these implementation components have yet to be developed.

This represents a significant missed opportunity to address preventable vision loss and improve chronic disease management through integrated care. For example, CHC patients with diabetes are more likely to follow through with eye exams when referred by their primary care provider (27), underscoring the importance of integrated care. Furthermore, Diabetes and Diabetes prevention-focused programs already exist at many CHCs (28–31). Supplementing those programs with eye care integration components can offer a sustainable, cohesive alignment opportunity. Evidence also suggests that screening for refractive error and early eye disease could prevent a high proportion of unnecessary vision loss or blindness (32, 33). As CHCs care for one in three persons in poverty, one in six Medicaid enrollees, one in five uninsured persons, and one in five rural residents in the United States, improvements and expansion of services in CHCs will directly benefit thousands of underserved communities nationwide (34).

As the prevalence of common eye diseases continues to rise, it is critical to understand how to better integrate eye care providers into comprehensive ambulatory safety net settings. There is growing support among major health agencies and funders for implementation science (IS) to improve the adoption of evidence-based care, including eye care in CHCs (35–44). To address persistent barriers, such as organizational readiness, population health needs, and financial sustainability, a structured, theory-informed approach is essential.

This Perspective introduces a structured, multi-level framework to guide the integration of eye care providers into CHCs. Drawing on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Research Framework, and the National Association of Community Health Centers' (NACHC) Value Transformation Framework (VTF), we develop and outline a five-stage model that supports readiness assessment, service design, implementation, evaluation, and scale-up. This framework is intended to detail how CHCs can support and promote public health by offering a practical roadmap for expanding vision care access in safety net settings.

An integrated framework to guide eye care provider integration into community health centers

To address the complex and multi-level barriers to integrating on-site eye care into CHCs, we propose a unified implementation framework that draws on three complementary models: CFIR (

45,

46), the NIMHD Research Framework (

47), and the VTF (

48). Together, these frameworks provide a structured, comprehensive approach to understanding and guiding implementation efforts. CFIR offers a structured approach to assessing readiness in the implementation process; the NIMHD Research Framework embeds equity across all levels of influence; and VTF ensures alignment with value-based care and operational sustainability. This integrated framework supports the design, implementation, and scale-up of sustainable eye care services in CHCs.

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (45, 46, 49). CFIR provides tools to assess organizational readiness, identify implementation barriers, and guide adoption. It includes five domains: outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, innovation, and implementation process. This can help CHCs evaluate their internal and external environments, staff capacity, and integration strategies.

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Research Framework (47). NIMHD describes an individual's health outcomes involving multiple levels of influence over the life course (47). The Research Framework created by NIMHD provides a multidimensional model that depicts a comprehensive set of health determinants, including domains of influence over the life course (biological, behavioral, physical/built environment, sociocultural environment, and the health care system) and levels of influence (individual, interpersonal, community, and societal) (47). This framework ensures that implementation efforts are equity-informed and responsive to the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). Applying this framework ensures that eye care integration addresses disparities in access, cultural relevance, and systemic barriers to reduce health disparities through multidisciplinary research and community involvement.

Value Transformation Framework (VTF) (48). Uniquely developed by the NACHC, the VTF supports CHCs in improving care delivery by aligning infrastructure, care delivery, and workforce with evidence-based strategies. With 15 change areas within the above 3 domains, it offers actionable ways to promote and sustain systems change, specifically focused on CHC improvement (48). VTF allows for aligning eye care integration within the broader goals of CHCs to provide quality and patient-centered care. It also supports the development of sustainable business models, including referral systems, telehealth capacity, and workforce development.

Framework summary

Together, CFIR, the NIMHD Research Framework, and VTF form a multi-dimensional framework to guide the integration of eye care in CHCs. CFIR helps to identify and address organizational and process-level barriers and facilitators that influence implementation, the NIMHD Research Framework ensures the integration efforts are equity-informed and community-focused, and VTF supports the financial and operational sustainability of eye care services within CHCs. Table 1 summarizes each framework's focus and application to the goal, as well as key questions to consider.

Table 1

| Summary of framework | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Framework | Focus | Level | Application to goal |

| CFIR |

|

Multi-level (individual, organizational, broader policy), implementation process | Identifies how to implement effectively within CHCs |

| NIMHD Research Framework |

|

Multi-level (individual to societal) | Ensures patient- and community-level focus addressing SDOH & equity |

| VTF |

|

CHC-system level | Ensures evaluation of quadruple aim (health outcomes, patient & staff experience, reduced costs. |

| Key Questions to consider in each stage | |||

| Stage of implementation | Key questions | ||

| Contextual Inquiry |

|

||

| Implementation Planning |

|

||

| Implementation |

|

||

| Pilot Testing & Evaluation |

|

||

| Scale-Up |

|

||

Summary of framework focus, level, application to goal, and key questions to consider.

*CFIR questions adapted directly from revised interview guide (49).

Integration process

To develop this model, we systematically mapped each framework's domains to the five stages of implementation. CFIR's inner and outer settings guided organizational and community readiness assessments, while its innovation and process domains informed workflow design and fidelity monitoring. NIMHD's multi-level emphasis on social determinants and equity was layered across all stages to ensure interventions addressed disparities at individual, community, and societal levels. VTF contributed operational and financial sustainability elements, including infrastructure, cost analysis, and alignment with value-based care. This mapping process allowed us to identify complementary strengths and reduce redundancy, resulting in a cohesive, multi-level roadmap for CHCs.

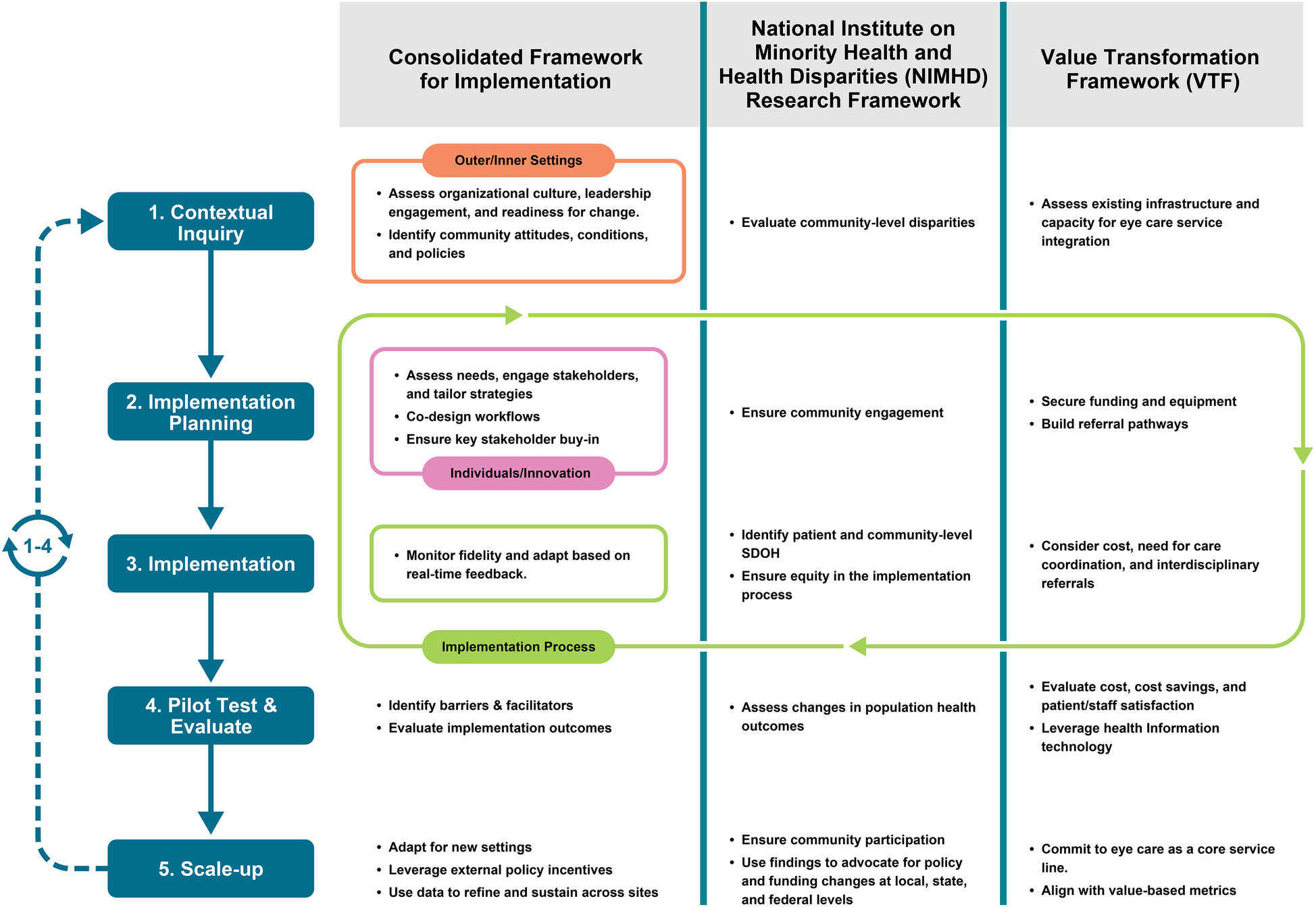

This integrated model works across five stages. 1) Contextual inquiry: involves evaluating organizational readiness (CFIR), infrastructure (VTF), and community-level disparities (NIMHD); 2) Implementation planning: focuses on co-designing service models, securing resources (e.g., space, equipment), building referral systems (i.e., surgical intervention), and using stakeholder/community input; 3) Implementation: strategies are focused on addressing individual and community-level SDOH. Here, there is significant emphasis on stakeholder engagement and staff buy-in; 4) Pilot testing and evaluation: use CFIR & Proctor's taxonomy to evaluate implementation outcomes, VTF to measure cost and care delivery, and NIMHD to assess population health outcomes; 5) Scale-up: involves expanding eye care services by aligning with sustainable long term financial models, and advocating for policy changes to support adoption. This model (Figure 1) provides a roadmap for CHCs to implement eye care services that are sustainable, equitable, and scalable. Table 1 also shares questions to consider in each stage.

Figure 1

Integrated framework for eye care integration in community health centers (CHCs), combining CFIR, NIMHD research framework, and value transformation framework (VTF). The model maps complementary domains from each framework across five stages of implementation: contextual inquiry, implementation planning, implementation, pilot testing and evaluation, and scale-up. CFIR informs readiness and process evaluation; NIMHD embeds equity and addresses social determinants of health; VTF ensures operational sustainability and alignment with value-based care.

Outcome evaluation

Evaluating the integration of eye care providers into CHCs requires a multi-dimensional approach that captures implementation, population health, and operational outcomes. This section emphasizes how the synthesis of CFIR, NIMHD Research framework, and VTF supports comprehensive outcome assessment across three domains. The integrated framework enables CHCs to assess fidelity, equity impact, and sustainability in a unified manner.

Implementation outcomes

While the CFIR framework is instrumental in identifying barriers and facilitators to implementation, it does not directly measure implementation outcomes. Thus, we also incorporate Proctor's taxonomy to assess key implementation metrics (50). These include qualitative outcomes (e.g., acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, and fidelity) and quantitative outcomes (e.g., adoption, feasibility, penetration) (50) to assess how well on-site eye care services are integrated within workflows.

Population health outcomes

The NIMHD Research Framework supports the evaluation of disparities in access, utilization, and outcomes at individual, community, and societal levels. Effectiveness indicators include rates of comprehensive eye exams among high-risk populations, reductions in preventable vision loss through early detection and treatment of conditions such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and amblyopia, as well as improvements in chronic disease management through coordinated care.

Operational outcomes

VTF emphasizes outcomes related to care quality, cost-effectiveness, and patient experience. Metrics may include Medicaid/Medicare revenue, improvement in diabetes management, or reduction in emergency department visits. These outcomes demonstrate the clinical and financial value of integrating eye care in individual CHCs.

Together, these outcome domains reflect the strength of the integrated framework in supporting sustainable, equitable, and scalable eye care delivery in safety net settings.

Practice and Policy Implications

This integrated framework provides a practical blueprint for implementing and sustaining eye care services in CHCs. It equips CHC leadership with tools to assess organizational readiness, identify and engage key stakeholders, and tailor implementation strategies to local contexts. The framework emphasizes equity by addressing patient and community-level social determinants of health (SDOH). It also supports alignment with quality improvement initiatives and value-based care, promoting a financially sustainable model for eye care delivery in CHCs.

Policy makers can also use this framework in guiding reimbursement reform and policy development. For example, expansion of Medicaid coverage for comprehensive eye care would directly support broader implementation efforts. While current research on the U.S. Medicaid program does not specifically examine eye care, its findings on improved access and reduced disparities following Medicaid expansion help set the stage for examining how similar changes could benefit comprehensive eye care services (51). A federal mandate requiring vision services as a component of primary care in CHCs, similar to dental or behavioral health (13), could also improve access and sustainability. Funders and researchers can support this transformation by investing in pilot programs, implementation research, and workforce development initiatives to build capacity in CHCs.

Applying the framework in a Community Health Center: A theoretical use case

To illustrate the practical application of this framework, consider a theoretical example of an urban CHC serving a predominantly low-income population with high rates of diabetes and limited access to specialty care.

Stage 1: Contextual inquiry

Organizational readiness is assessed by external designers and implementation researchers using a CFIR-based survey and semi-structured interviews with CHC leadership, frontline staff, the quality improvement team, and the Community Advisory Board. These tools are publicly available and evaluate leadership engagement, available resources, and readiness for change {Research, 2023 #1337}. Strong leadership support and space are identified and it is also determined that there is currently limited staffing. A community health needs assessment (CHNA), required to be conducted every 3 years by FQHCs, is conducted by the CHC's research team and included questions about history of eye disease and whether individuals have had an eye exam in the prior 12 months (52). This CHNA reveals high rates of diabetic retinopathy in the community compared to national and county prevalence rates as estimated by the CDC {CDC, 2025 #1577} {Lundeen, 2023 #1578}, as well as low rates of diabetic eye examinations in CHC patients, a Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure (53). Additionally, internal assessment finds gaps in care coordination as well as billing.

Stage 2: Implementation planning

Findings from contextual inquiry directly inform strategy selection. The CHC forms a multidisciplinary planning team, including primary care, finance, quality improvement, information technology, frontline staff, and CHC patients. A service model is co-designed to include part-time on-site optometry services, the addition of an AI-based diabetic retinopathy screening using fundus camera operated by trained image takers, and a referral pathway to ophthalmology for individuals requiring treatment for diabetic retinopathy. This approach ensures comprehensive coverage across the CHC network while addressing workforce constraints. Pilot funding is secured through CHC partnerships to support equipment purchase and optometrist staffing. Additional community input is gathered through meetings with the Community Advisory Board and interactive workshops to ensure cultural relevance and build community trust. Specific questions and considerations are included in Table 1.

Stage 3: Implementation

Implementation is explicitly tied to barriers identified during contextual inquiry and the CHC launches a pilot at one site. Standing orders for diabetic eye exams are introduced to reduce missed referrals, addressing gaps in care coordination. Confidence and fidelity are built through staff training that incorporates practice based learning on the AI-based diabetic retinopathy screening camera, as well as protocols for referrals to the internal optometrist and external ophthalmologist based on screening results. Community health workers assist patients with scheduling and transportation, mitigating social determinants of health that may have been identified during contextual inquiry. Standing meetings are held to monitor fidelity, review early data, and enable rapid prototyping and adaptation of workflows.

Stage 4: Evaluation

Implementation outcomes are evaluated using Proctor's taxonomy and include adoption, fidelity, and acceptability. Adoption is measured as the percentage of eligible patients with diabetes screened using electronic health record data, fidelity is assessed through workflow reviews, and acceptability is evaluated via staff and patient surveys. Several measurement resources are publicly available through the Dissemination & Implementation Models in Health Research and Practice Webtool {University of Colorado Denver, 2025 #1579}. Cost-effectiveness is analyzed by comparing implementation costs to revenue generated, which includes reviewing billing codes used by the optometrist for comprehensive eye exams and procedures, as well as reimbursement rates for AI-based diabetic retinopathy screening. Population health metrics include changes in CHC-level diabetic eye exam rates in comparison to community-level metrics, as well as rates of referrals for treatment.

Stage 5: Scale-up

Upon positive pilot results, the CHC creates the program as a permanent service and expands its screening to additional CHCs. The CHC then begins to evaluate screening for glaucoma and refractive error. At the state level, partners begin advocating for policy changes to support on-site vision care statewide using data gathered from the pilot.

Discussion

Despite the high burden of vision impairment and the availability of effective interventions, most CHCs lack integrated eye care services. This Perspective responds to a long-standing gap in primary care by offering a structured, equity-informed framework to guide the integration of optometrists and ophthalmologists into CHCs. By combining CFIR, NIMHD, and VTF, the model addresses readiness, equity, and sustainability, three critical dimensions often overlooked in specialty care integration.

The integrated framework offers a practical roadmap for CHC leaders, policymakers, and public health stakeholders to implement and sustain eye care services in underserved settings. However, successful implementation will require overcoming persistent challenges, including limited space, staffing shortages, and reimbursement constraints. CHCs vary widely in infrastructure and capacity, and adaptation of this framework must be context-specific. Stakeholder engagement, particularly with CHC administrators, eye care providers, and patients, will be essential to ensure feasibility and community buy-in. This framework outlines a practical playbook for CHC leaders and policymakers to support the sustainable and equitable expansion of access to these essential services in underserved communities across the US.

While conceptual, this framework is grounded in evidence-based models and informed by the operational realities of CHCs. It serves as a critical starting point for researchers, providers, and policymakers to build and test implementation strategies that are contextually relevant, equity-focused, and scalable. Ultimately, this integrated framework supports a long-term policy goal, the inclusion of on-site eye care services by an eye care provider as a required component of primary care in CHCs. With coordinated advocacy, research, and investment, it has the potential to transform vision care delivery and reduce preventable blindness in underserved communities.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AS: Visualization, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SP: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JF: Validation, Writing – review & editing. JM: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by NIH/NEI K23 EY034602 (Scanzera), NIH/NEI P30 EY001792, and an unrestricted grant to the UIC Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this work.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lauren Kalinoski for her assistance in updating the framework figure, which significantly enhanced the clarity and visual presentation of our conceptual model.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used Microsoft Copilot to improve the readability of this manuscript only, and no content was generated by AI.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Saaddine JB Narayan KM Vinicor F . Vision loss: a public health problem?Ophthalmology. (2003) 110(2):253–4. 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01839-0

2.

Elam AR Lee PP . High-risk populations for vision loss and eye care underutilization: a review of the literature and ideas on moving forward. Surv Ophthalmol. (2013) 58(4):348–58. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.07.005

3.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030 Health.gov: U.S. Rockland, MD: Department of Health and Human Services (2020).

4.

McCarty CA Taylor HR . Reviewing the impact of social determinants of health on rural eye care: a call to action. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2022) 50(5):475–8. 10.1111/ceo.14086

5.

Rasendran C Tye G Knusel K Singh RP . Demographic and socioeconomic differences in outpatient ophthalmology utilization in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. (2020) 218:156–63. 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.05.022

6.

Hale NL Bennett KJ Probst JC . Diabetes care and outcomes: disparities across rural America. J Community Health. (2010) 35(4):365–74. 10.1007/s10900-010-9259-0

7.

Klein R Klein BE . The prevalence of age-related eye diseases and visual impairment in aging: current estimates. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2013) 54(14):ORSF5–ORSF13. 10.1167/iovs.13-12789

8.

Peek ME Cargill A Huang ES . Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. (2007) 64(5 Suppl):101S–56. 10.1177/1077558707305409

9.

Qiu M Wang SY Singh K Lin SC . Racial disparities in uncorrected and undercorrected refractive error in the United States. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. (2014) 55(10):6996–7005. 10.1167/iovs.13-12662

10.

Fricke TR Tahhan N Resnikoff S Papas E Burnett A Ho SM et al Global prevalence of presbyopia and vision impairment from uncorrected presbyopia: systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling . Ophthalmology. (2018) 125(10):1492–9. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.013

11.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Federally Qualified Health Center. Woodlawn, MD: CMS (2025).

12.

National Association of Community Health Centers. America’s Health Centers. Bethesda, MD: NACHC (2024). Available from: Available online at:https://www.nachc.org/resource/americas-health-centers-by-the-numbers/?utm_source=chatgpt.com(Accessed July 01, 2025).

13.

HRSA. Health Centers: A Guide for Patients. In: Care BoP, editor (2024).

14.

Landon BE Hicks LS O'Malley AJ Lieu TA Keegan T McNeil BJ et al Improving the management of chronic disease at community health centers. N Engl J Med. (2007) 356(9):921–34. 10.1056/NEJMsa062860

15.

Bailey MJ Goodman-Bacon A . The war on poverty’s experiment in public medicine: community health centers and the mortality of older Americans. Am Econ Rev. (2015) 105(3):1067–104. 10.1257/aer.20120070

16.

Goldman LE Chu PW Tran H Romano MJ Stafford RS . Federally qualified health centers and private practice performance on ambulatory care measures. Am J Prev Med. (2012) 43(2):142–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.033

17.

Jin JL Bolton J Nocon RS Huang ES Hoang H Sripipatana A et al Early experience of the quality improvement award program in federally funded health centers. Health Serv Res. (2022) 57(5):1070–6. 10.1111/1475-6773.13986

18.

Skinner D Wright B . The paradoxical politics of community health centers from the great society to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Health Polit Policy Law. (2023) 48(3):379–404. 10.1215/03616878-10358724

19.

Parker E . Poverty governance in the delegated welfare state: privatization, commodification, and the U.S. Health Care Safety Net. Social Problems. (2025) 72(4):1595–612. 10.1093/socpro/spae037

20.

Parker E . Politics, stigma, and the market: Access to health care for the poor in the United States, 1965–2020 (2021).

21.

Shin P Finnegan B . Assessing the need for on-site eye care professionals in community health centers. Policy Brief George Wash Univ Cent Health Serv Res Policy. (2009):1–23. PMID: 19768853.

22.

Woodward MA Hicks PM Harris-Nwanyanwu K Modjtahedi B Chan RVP Vogt EL et al Eye care in federally qualified health centers. Ophthalmology. (2024) 131(10):1225–33. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.04.019

23.

Health Resources & Services Administration. National Health Center Program Uniform Data System (UDS) Awardee Data (2025). Contract No.: Jule 14.

24.

Health Resources & Services Administration. National Health Center Program Uniform Data System (UDS) Look-Alike Data (2025).

25.

Bai P Burt SS Woodward MA Haber S Newman-Casey PA Henderer JD et al Federally qualified health centers as a model to improve vision health: a systematic review. JAMA Ophthalmol. (2025) 143(3):242–51. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2024.6264

26.

Lipton BJ Garcia J Boudreaux MH Azatyan P McInerney MP . Most state medicaid programs cover routine eye exams for adults, but coverage of other routine vision services varies. Health Aff. (2024) 43(8):1073–81. 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00873

27.

Chin MH Cook S Drum ML Guillen JL Humikowski M A C et al Improving diabetes care in midwest community health centers with the health disparities collaborative. Diabetes Care. (2004) 27(1):2–8. 10.2337/diacare.27.1.2

28.

Huguet N Green BB Larson AE Moreno L DeVoe JE . Diabetes and hypertension prevention and control in community health centers: impact of the affordable care act. J Prim Care Community Health. (2023) 14:21501319231195697. 10.1177/21501319231195697

29.

Modica C Lewis JH Bay RC . The value transformation framework: applied to diabetes control in federally qualified health centers. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2021) 14:3005–14. 10.2147/JMDH.S284885

30.

Rivers P Hingle M Ruiz-Braun G Blew R Mockbee J Marrero D . Adapting a family-focused diabetes prevention program for a federally qualified health center: a qualitative report. Diabetes Educ. (2020) 46(2):161–8. 10.1177/0145721719897587

31.

Van Name MA Camp AW Magenheimer EA Li F Dziura JD Montosa A et al Effective translation of an intensive lifestyle intervention for hispanic women with prediabetes in a community health center setting. Diabetes Care. (2016) 39(4):525–31. 10.2337/dc15-1899

32.

Varma R Vajaranant TS Burkemper B Wu S Torres M Hsu C et al Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the United States: demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmol. (2016) 134(7):802–9. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1284

33.

National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Health, Medicine D, Board on Population H, Public Health P, et al. The national academies collection: reports funded by national institutes of health. In: WelpAWoodburyRBMcCoyMATeutschSM, editors. Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) (2016). Copyright 2016 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

34.

National Association of Community Health Centers. Community Health Center Chartbook. Bethesda, MD: National Association of Community Health Centers (2023).

35.

Handley MA Gorukanti A Cattamanchi A . Strategies for implementing implementation science: a methodological overview. Emerg Med J. (2016) 33(9):660–4. 10.1136/emermed-2015-205461

36.

Glasgow RE Vinson C Chambers D Khoury MJ Kaplan RM Hunter C . National institutes of health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102(7):1274–81. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755

37.

Sampson UK Chambers D Riley W Glass RI Engelgau MM Mensah GA . Implementation research: the fourth movement of the unfinished translation research symphony. Glob Heart. (2016) 11(1):153–8. 10.1016/j.gheart.2016.01.008

38.

Oh A Abazeed A Chambers DA . Policy implementation science to advance population health: the potential for learning health policy systems. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:681602. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.681602

39.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ’s Dissemination and Implementation Initiative (2022). Available online at: https://www.ahrq.gov/pcor/ahrq-dissemination-and-implementation-initiative/index.html(Accessed July 01, 2025).

40.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Evidence for Action: Innovative Research to Advance Racial Equity. Open Call for Proposals (2022). [Available online at: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/funding-opportunities/2021/evidence-for-action-innovative-research-to-advance-racial-equity.html(Accessed July 01, 2025).

41.

National Heart L, and Blood Institute. Sustaining Global Capacity for Implementation Research for Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries and Small Island Developing States (2022) Available online at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/events/2020/sustaining-global-capacity-implementation-research-health-low-and-middle-income(Accessed July 01, 2025).

42.

Black AT Steinberg M Chisholm AE Coldwell K Hoens AM Koh JC et al Building capacity for implementation—the KT challenge. Implement Sci Commun. (2021) 2(1):84. 10.1186/s43058-021-00186-x

43.

Davis R D'Lima D . Building capacity in dissemination and implementation science: a systematic review of the academic literature on teaching and training initiatives. Implement Sci. (2020) 15(1):97. 10.1186/s13012-020-01051-6

44.

Notice of Participation of the National Eye Institute in PAR-22-105, “Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health (R01 Clinical Trial Optional)” [press release] (2022).

45.

Kirk MA Kelley C Yankey N Birken SA Abadie B Damschroder L . A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci. (2016) 11:72. 10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z

46.

Damschroder LJ Aron DC Keith RE Kirsh SR Alexander JA Lowery JC . Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

47.

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. NIMHD Research Framework (2017).

48.

Modica C . The value transformation framework: an approach to value-based care in federally qualified health centers. J Healthc Qual. (2020) 42(2):106–12. 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000239

49.

Damschroder LJ Reardon CM Widerquist MAO Lowery J . The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implement Sci. (2022) 17(1):75. 10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0

50.

Proctor E Silmere H Raghavan R Hovmand P Aarons G Bunger A et al Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2011) 38(2):65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

51.

Donohue JM Cole ES James CV Jarlenski M Michener JD Roberts ET . The US medicaid program: coverage, financing, reforms, and implications for health equity. JAMA. (2022) 328(11):1085–99. 10.1001/jama.2022.14791

52.

Health Resources & Services Administration. Chapter 3: Needs Assessment. Rockville, MD: Health Resources & Services Administration (2025) Available online at: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/compliance/compliance-manual/chapter3(Accessed July 01, 2025).

53.

An J Niu F Turpcu A Rajput Y Cheetham TC. Adherence to the American diabetes association retinal screening guidelines for population with diabetes in the United States. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25(3):257–65. 10.1080/09286586.2018.1424344

Summary

Keywords

community health center, federally qualified health center, health equity, implementation framework, access to eye care, optometry, ophthalmology

Citation

Scanzera AC, Russo D, Primo SA, Fleurimont J and Markowski JH (2025) Integrating eye care into Community Health Centers: a framework for advancing vision equity in underserved communities. Front. Health Serv. 5:1697969. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2025.1697969

Received

15 September 2025

Revised

11 November 2025

Accepted

28 November 2025

Published

18 December 2025

Volume

5 - 2025

Edited by

Pan Long, General Hospital of Western Theater Command, China

Reviewed by

Caroline Presley, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Scanzera, Russo, Primo, Fleurimont and Markowski.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Angelica C. Scanzera ascanz@uic.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.