- Council for Agricultural Research and Economics (CREA) - Research Center for Olive, Fruit and Citrus Crops, Acireale, Italy

Edible insect flour, particularly from house cricket (Acheta domesticus) and mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), is gaining attention as a sustainable and functional food ingredient due to its high nutritional value and low environmental impact. The edible insects are considered a source of micronutrients and protein which play a crucial role as they are involved in several physiological processes. Moreover, edible insects are also a source of fatty acids and fiber. Beyond these recognized benefits, insect flour may also contribute to gut health through potential prebiotic properties. Indeed, several studies highlighted that insect flour may interact with probiotic bacteria by modulating their metabolism. In the gut microbiota, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, the most important genera for their probiotic activities are known to be susceptible to the action of prebiotics. However, further study is needed on the strain-dependent response of probiotics to insect flour. These highlighted activities related to the application of insect flour as food and feed, underline its functional value beyond its nutritional content, suggesting it as a new ingredient capable of promoting beneficial gut microbiota.

Introduction

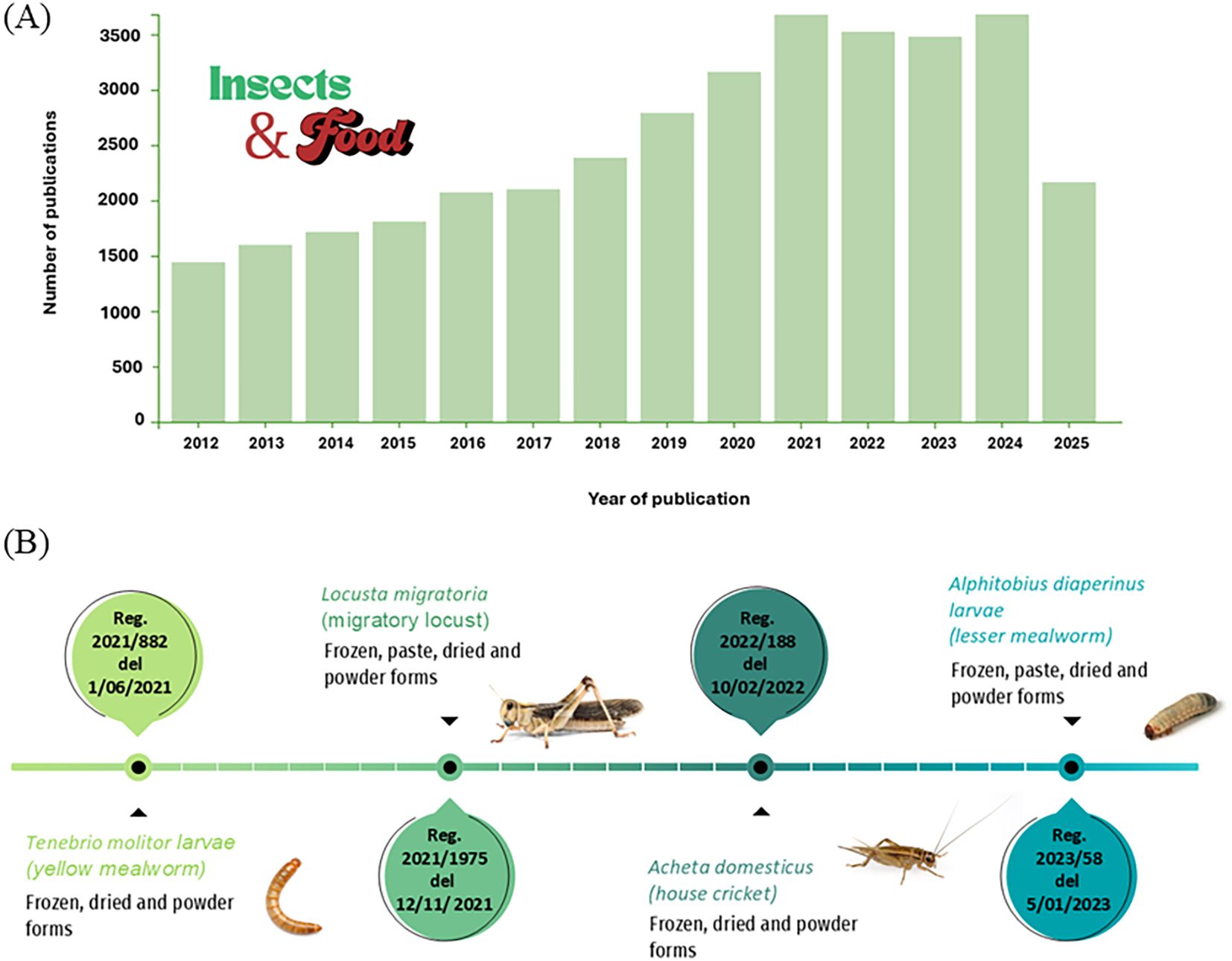

For the challenge of feeding the world’s population by 2030, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has approved the large-scale development of insect farming. Indeed, in recent years, the FAO has been strongly committed to the “Edible Insects” program, which aims to promote the use of edible insects in both human nutrition and animal feed production, with potential health and environmental benefits. According to the FAO, the consumption of insects as food is an effective strategy to counteract the rising costs of animal proteins, food insecurity, environmental challenges, responding to population growth and the resulting increase in protein demand (Tao and Li, 2018). Currently, entomophagy is most widespread in Asian countries such as Thailand, South America, and sub-Saharan Africa (Conway et al., 2024). The consumption and trade of edible insects in developing or underdeveloped Asian countries represent an important source of income, contributing to economic empowerment and improved living conditions (Van Huis, 2022). From an economic point of view, the edible insect sector is showing rapid and continuous expansion. A report by Rabo Bank estimates that global demand for insect protein will increase significantly, from the current 120,000 tons to around 500,000 tons by 2030 (De Jong and Nikolik, 2021). This growth will be accompanied by a reduction in the cost of production, with the price per ton of insect protein set to fall, thus promoting greater accessibility on the market. Furthermore, the report by the International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed, a European organization representing companies in the insect sector, predicts a production capacity of up to 1 million tons of insect flour by 2030, provided that favorable conditions such as appropriate regulations are guaranteed. Therefore, investment in the sector could triple, rising from €1 billion to €3 billion (IPIFF, 2021). In the scientific field, the topic of insects as a food resource has sparked growing interest, attracting the attention of numerous research groups. As shown in Figure 1A, the report obtained from the Web of Science database using the keywords “insects” and “food” highlights a strong upward trend, with the number of publications reaching record levels as early as 2021. This increase demonstrates the growing importance of the issue in the scientific community and recognition of the potential offered by entomophagy to address global challenges related to food security and environmental sustainability in accordance with the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guidelines. The EFSA has approved the use of some insects as novel foods, authorizing their use in the European Union in specific forms. According to EFSA assessments and the subsequent European Commission acts, the following insects have been definitively authorized: Tenebrio molitor larvae (mealworms) – dried; Locusta migratoria (migratory locust) – frozen, dried or powdered; Acheta domesticus (house cricket) – frozen, dried or powdered; Alphitobius diaperinus (lesser mealworm) larvae frozen, paste, dried and powdered forms (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. (A) Records found on Web of Science related to insects and food from 2012 to 2025; 1 (B) Insects approved by EFSA.

The Italian government has approved European authorizations allowing foods made from insects in frozen, dried or powdered form. Specifically, on 29 December 2023, four ministerial decrees (Ministry of Agriculture in agreement with the Ministry of Health and Enterprise) were published in the Italian Official Gazette, introducing specific rules on labelling and sales methods for these European authorized products. This decree provides specific regulations such as indicating on the label the type of insect, the form of the product (e.g. partially defatted, dried or frozen powder), the maximum quantity (up to 10%) and the country of origin of the flour. In addition, the information on the label must be immediately visible, clear and not hidden by other graphic information; there must be indications of allergenic risks, especially for people with allergies to crustaceans, mollusks and mites; products containing insect flour must be sold in separate shelf sections, with dedicated labelling.

Edible insects as novel foods: nutritional content and value

The growing interest in edible insects as novel food is primarily due to their high environmental sustainability but also their significant nutritional value. The edible insects are considered a source of micronutrients and protein, with an average protein content of 40%, ranging from 20% to over 70%, depending on the insect species (Elhassan et al., 2019). In relation to human health and well-being, proteins play a crucial role as they are involved in several physiological processes such as the immune response and different biochemical reactions. Edible insects, as a food source, can provide a quantity of essential amino acids that are 76 to 96% digestible (Tang et al., 2019). The content of essential and semi-essential amino acids in commonly consumed species is compared with the recommended daily intake for adults, as established by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2007) and is found to be in line with the WHO guidelines for meeting amino acid requirements. In addition to their protein content, the nutritional value of insects is also linked to the presence of other substances essential for human health, such as fats (saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids and polyunsaturated fatty acids), vitamins (A, D2, D3, C, E, K, thiamine, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, niacin, pyridoxine, folic acid, D-biotin and vitamin B12), and minerals (iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, magnesium, sodium, phosphorus, iron and copper). The active ingredients from edible insects have a variety of beneficial functional effects on human health including tumor growth inhibition, immune system modulation, antibacterial, antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory properties, regulation of blood glucose and lipid levels, lowering of blood pressure, modulation of gut microbiota, and cardiovascular protection (Nowakowski et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2021).

Edible insects as a new source of prebiotics?

Due to their protein value and documented health benefits, insects can play a role as sources of prebiotic compounds capable of modulating the intestinal microbiota, thus bringing benefits to human health. The definition of prebiotic has been revised by Gibson et al. (2017) and refers to a substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms that confers health benefits. The authors provided the conclusions of the consensus panel on prebiotics: (i) although oral administration is the most common mode of administration, prebiotics can also be applied to other parts of the body colonized by microbes (as the skin and vaginal tract); (ii) prebiotics are substances that, when administered in adequate amounts over a period of time, provide health benefits to the host; (iii) the beneficial effects currently recognized mainly concern the gastrointestinal system, cardiovascular metabolism, mental health and healthy bones; (iv) although it is difficult to prove causality with certainty, controlled studies can provide reasonable evidence of a direct link between prebiotics and improved health; (v) conventional prebiotics are carbohydrate-based, but other substances, such as polyphenols and converted polyunsaturated fatty acids, may fall within the updated definition, provided they are supported by convincing evidence; (vi) the beneficial effect must be demonstrated in the target animal or host and must be mediated by the microbiota. The substances most used as prebiotics are fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), trans-galacto-oligosaccharides (TOS), lactulose and other compounds (Davani-Davari et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2020). Among the bioactive compounds contained in insects, chitin, a structural polysaccharide abundant in the exoskeleton of insects, has attracted considerable interest for its potential role as a prebiotic (Colamatteo et al., 2025). Chitin is a linear polymer of β-(1-4)-linked N-acetyl glucosamine and is the most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose. To date, clinical studies have reported that orally administered chitin reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease and may positively influence the immune system (Dong et al., 2019). Despite the beneficial effect of insects, chitin and insect derived proteins are under investigation for their allergenic potential since they can bind to immunoglobulin E (IgE) and induce immune responses. Several studies in the literature have demonstrated that most insect-based food processing and preparation methods were not able to reduce allergenic factors. Indeed, tropomyosin (the main allergen present in insects) is highly heat stable, therefore the different processing techniques may represent a more effective approach to reducing insect derived allergens (Gunal-Koroglu et al., 2025). In this context, authors have proposed that the lactic fermentation of insect flour represents a possible solution to reduce their allergenic potential. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), particularly strains from the Lactobacillus genus, can modify protein structures through their proteolytic system, breaking down proteins into oligopeptides and thereby reducing IgE-binding epitopes (Guo et al., 2016).

Scientific evidence from the literature on insect-derived prebiotics and our findings

Recent research has shown that chitin derived from crickets (Acheta domesticus) and pupae of the silkworm (Bombyx mori) and extracted chitin have been shown to positively influence microbial biodiversity in an in vitro digestion analysis that simulates the oral, gastric and intestinal phases, followed by fermentation in anaerobic bioreactors inoculated with human stools from 10 healthy volunteers. After simulated digestion and subsequent fermentation by the gut microbiota, metagenetic analysis revealed the growth of symbiotic bacteria important for health, such as those belonging to the Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae families, or the Faecalibacterium and Roseburia genera, without altering the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (Refael et al., 2022). Furthermore, another study (Kipkoech et al., 2021) showed that cricket-derived chitosan used at different concentrations in modified media (from 1% to 20%) significantly increased in vitro the population of probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium adolescentis (the name of the genus and species belonging to the previous taxonomic classification has been shown in accordance with the quoted reference) and selectively inhibited only the growth of pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella/Shigella. Tenebrio molitor flour has also been studied for its ability to support the growth and vitality of probiotic bacteria, especially under conditions of nutritional stress, and to increase the production of SCFAs and lactate, clear signs of a prebiotic effect that could be exploited in both human and animal nutrition. In detail, different studies demonstrated that Tenebrio molitor insect flour and chitosan oligosaccharides obtained from the same insect have shown prebiotic activity. In the first study (de Carvalho et al., 2019), the Tenebrio molitor insect flour was tested in an optimized in vitro intestinal model, using Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium cultures in both monoculture and consortium. The results showed that Tenebrio molitor insect flour not only has no negative effects on the viability of probiotics, but also promotes their growth, increasing the production of SCFAs and lactate, especially under nutritional stress conditions. This suggests a possible prebiotic effect of Tenebrio molitor flour. In the second study, the aim was to optimize the production of mealworm chitosan oligosaccharides (MCOS) using the enzyme chitosanase (Kim et al., 2024). The MCOS obtained showed a significant concentration-dependent prebiotic effect, stimulating the growth of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lacticaseibacillus casei and Bifidobacterium bifidum. Furthermore, the addition of MCOS positively influenced the composition of the cecal microbiota (through in vitro anaerobic fermentation) and SCFAs production, with an increase in the abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia and Turicibacter. In addition, several studies were conducted on mice to validate the prebiotic properties of Tenebrio molitor Specifically, the two (Lee et al., 2021 and Kwon et al., 2020) in vivo studies conducted on BALB/c mice (inbred strain of laboratory mice commonly used in biomedical research) analyzed the prebiotic potential of Tenebrio molitor, both in the form of fermented mealworms (FM) and exuviae (i.e. the residual cuticles from molting). In both cases, administration for 8 weeks did not alter the animals’ diet or their body weight but led to a significant increase in intestinal lactic bacteria, particularly of the Bifidobacteriaceae and Lactobacillaceae families, compared to the control groups. In the first study (Lee et al., 2021), fermented worms improved the diversity of the intestinal microbiota without altering the total amount of bacteria. In the second study (Kwon et al., 2020), the inclusion of 20% exuviae in the mice diet showed similar effects, confirming the prebiotic potential of the chitin contained in the cuticles. However, further studies in humans are needed to confirm these beneficial effects.

As part of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), within the project “Technologies for climate change adaptation and quality of life improvement” (TECH4YOU), the action “Intelligent Modelling and Prototyping of Insect Farming for Food Purposes” was developed by the Department of Agriculture at the University of Reggio Calabria, in collaboration with the Council for Agricultural Research and Economics (CREA) – Research Centre for Olive, Fruit and Citrus Crops. One of the action’s specific objectives was to investigate the potential prebiotic effects of cricket flour produced from Acheta domesticus. As reported in literature, Acheta domesticus is one of the most farmed species for human consumption, farmed on almost every continent except Antarctica, thanks to its high nutritional value (Siddiqui et al., 2024). Preliminary findings obtained through simulated in vitro digestion confirmed results previously reported in the literature. After assessing the microbiological suitability of cricket flour using culture-dependent methods, and confirming its safety for human consumption, its potential prebiotic activity was subsequently analyzed on 4 probiotic strains used in monoculture: Lacticaseibacillus paracasei 101/37, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus CRL 1505, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BLC1 and Bifidobacterium longum ATCC BAA-999. The beneficial effects of A. domesticus appear to be strongly linked to the presence of chitin, which by diacetylation produces chitosan, whose activity is strongly correlated with antibacterial and prebiotic properties (Kipkoech et al., 2021). Chitosan exerts its antimicrobial effects mainly through interaction with the bacterial cell wall. Its positive charge allows it to adhere to the negatively charged surface of bacterial cells, thereby compromising the integrity of the cell wall and increasing membrane permeability. In addition, chitosan can bind to bacterial DNA, interfering with replication mechanisms and ultimately inducing cell death. Another proposed mechanism involves its ability to chelate metal ions, which can contribute to the formation of toxic by-products (Yilmaz, 2020; Guarnieri et al., 2022). Regarding probiotic strains, current evidence indicates that some species can partially ferment chitosan and use it as a substrate to support growth. Lactobacillus species have shown favorable growth responses, although this effect depends largely on the specific strain. However, high concentrations of chitosan may suppress rather than enhance the proliferation of probiotics (Guan and Feng, 2022). Therefore, targeted research could help expand the application of insect-derived flours as new prebiotic sources, potentially optimized through combination with selected probiotic strains.

Social acceptance of edible insects: challenges and opportunities

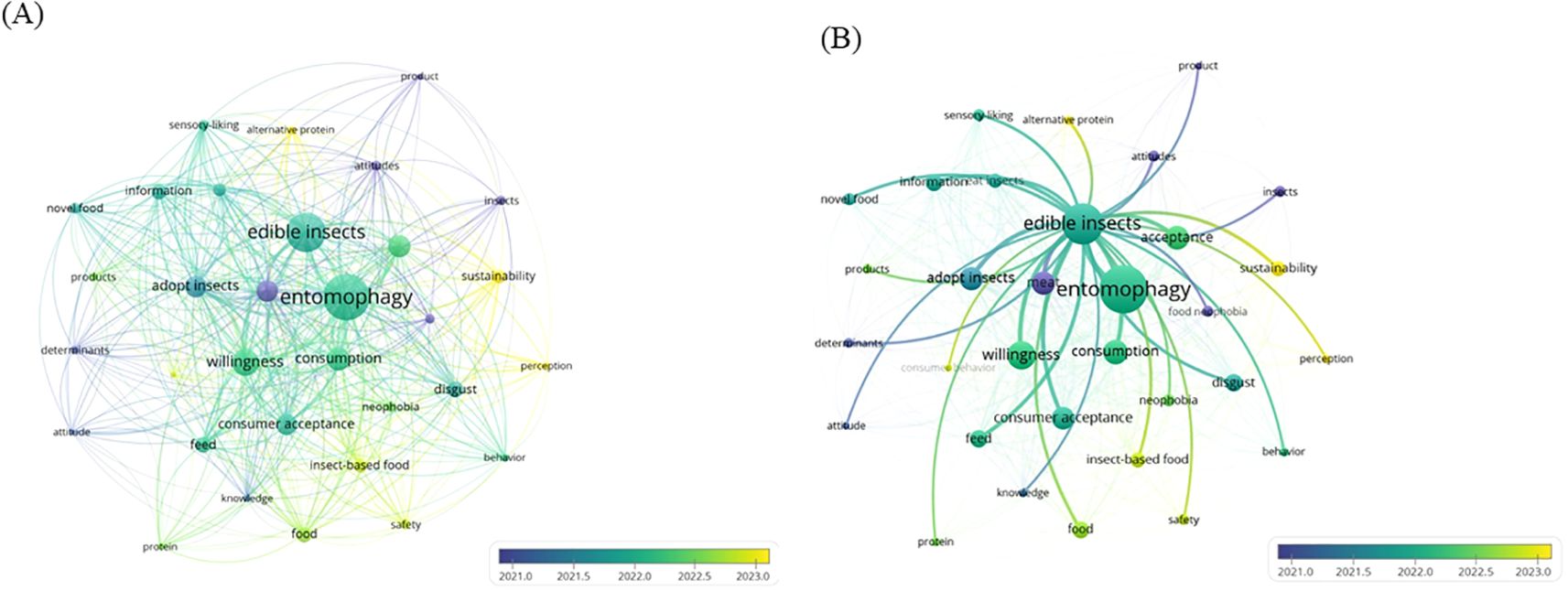

Around 1,700 species of insects are consumed as food worldwide. Although insects are an important source of nutrients for many countries, their consumption remains limited in other developed countries, because they are often perceived as “repulsive” or “disgusting” (Fukano and Soga, 2021). Nevertheless, the nutritional value of insects is too significant to be ignored. Although many Western consumers express distrust or disgust towards entomophagy, motivated by both cultural and psychological reasons, a gradual transformation is being observed in this sector. Indeed, a growing number of companies are offering bakery products containing insect flour, such as biscuits, protein bars and pasta, thus disguising the original appearance of the insect, to facilitate consumer acceptance (Siemianowska et al., 2013; Hamerman, 2016). Recent research indexed in the Web of Science over the past few years has demonstrated a significant increase in scientific interest in entomophagy (Figures 2A, B). The most frequent recurring themes include “entomophagy”, “edible insects” and “consumer acceptance”, reflecting a growing increase in research aimed primarily at understanding the spread and acceptance of insects as food, particularly in Western countries. Among the main identified obstacles, disgust emerges as a predominant emotional and cultural reaction, especially in societies that do not have a past tradition of consuming insects. This reaction is closely associated with concepts as “acceptance”, “consumption” and “behavior”, highlighting its direct influence on individuals’ availability to consume new insect-based foods. Since 2022, food safety has become a central theme in entomophagy research (Pinheiro et al., 2025). Currently, a growing number of studies are examining the perceived risks associated with the consumption of edible insects, including the presence of possible allergens, contaminants and pathogenic microorganisms. Despite the introduction of increasingly stringent regulations, particularly within the European Union, where insects are classified and authorized as “novel foods”, consumer perception of risk remains high. This highlights the importance of clear, transparent and evidence-based communication to reinforce consumer confidence and acceptability. An additional psychological barrier is food neophobia, defined as the reluctance or refusal to eat unfamiliar foods. This tendency is especially pronounced among individuals with limited exposure to diverse food experiences or those who exhibit a more conservative approach to dietary choices. Empirical models consistently demonstrate a strong correlation between neophobia, disgust sensitivity, and consumer behavior, suggesting that fear of the unfamiliar can significantly amplify rejection of insect-based foods (Sogari et al., 2019). To address these concerns, several studies advocate targeted educational interventions, guided sensory experiences, and strategic marketing campaigns. These efforts aim to normalize insect consumption by introducing insect-based foods or new formulations with high added value (Cantalapiedra et al., 2023).

Figure 2. (A) Vosviewer network visualization of the bibliometric keywords map for edible insect and food papers in last years from Web of Science (B) Vosviewer network correlation with the word edible insect. (Created in vosviewer.com).

Conclusions and future perspectives

In view of growing environmental challenges and the emerging need for sustainable food sources, edible insects represent a promising protein alternative. However, their diffusion on a large scale, particularly in Western societies, is still hampered by deeply rooted cultural and psychological barriers, such as disgust, food safety concerns and food neophobia. Overcoming these obstacles will require targeted educational interventions, guided sensory experiences and innovative product formulations to facilitate social acceptance. In addition to nutritional and ecological benefits, recent research has highlighted the functional potential of insects, particularly as a source of prebiotic ingredients. This discovery extends the view of insects as food, positioning them not only as sustainable protein alternatives but also as functional foods with beneficial health effects. Future investigations are needed to validate in vivo these prebiotic effects and to identify the bioactive compounds responsible for modulating the gut microbiota. Moreover, consumer research should explore how health-focused communication, emphasizing gut health and prebiotic advantages, might influence willingness to consume insect-based foods. Product development efforts should aim to integrate insect-based ingredients into popular food formats that mirror consumer preferences.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

PF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. RS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. FR: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Grant number ECS00000009.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the project TECH4YOU “Technologies for climate change adaptation and quality of life improvement”, innovation ecosystem project DM 1049 funded by the Ministry of University and Research (Next Generation EU - NRRP).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Cantalapiedra F., Juan-García A., and Juan C. (2023). Perception of food safety associated with entomophagy among higher-education students: Exploring insects as a novel food source. Foods 12, 4427. doi: 10.3390/foods12244427

Colamatteo I., Bravo I., and Cappelli L. (2025). Insect-based food products: A scoping literature review. Food Res. Int. 200, 115355. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.115355

Conway A., Jaiswal S., and Jaiswal A. K. (2024). The potential of edible insects as a safe, palatable, and sustainable food source in the European Union. Foods 13, 387. doi: 10.3390/foods13030387

Davani-Davari D., Negahdaripour M., Karimzadeh I., Seifan M., Mohkam M., Masoumi S. J., et al. (2019). Prebiotics: definition, types, sources, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Foods 8, 92. doi: 10.3390/foods8030092

De Carvalho N. M., Teixeira F., Silva S., Madureira A. R., and Pintado M. E. (2019). Potential prebiotic activity of Tenebrio molitor insect flour using an optimized in vitro gut microbiota model. Food Funct. 10, 3909–3922. doi: 10.1039/C8FO01536H

De Jong B. and Nikolik G. (2021). No Longer Crawling: Insect Protein to Come of Age in the 2020s (Amsterdam, The Netherlands: RaboResearch), 1–9.

Dong L., Wichers H. J., and Govers C. (2019). “Beneficial health effects of chitin and chitosan,” in Chitin and Chitosan. Eds. Van Den B. and Boeriu C. G. (Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA), 145–167.

Elhassan M., Wendin K., Olsson V., and Langton M. (2019). Quality aspects of insects as food—nutritional, sensory, and related concepts. Foods 8, 95. doi: 10.3390/foods8030095

Fukano Y. and Soga M. (2021). Why do so many modern people hate insects? The urbanization–disgust hypothesis. Sci. Total. Environ. 777, 146229. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146229

Gibson G. R., Hutkins R., Sanders M. E., Prescott S. L., Reimer R. A., Salminen S. J., et al. (2017). Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 491–502. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75

Guan Z. and Feng Q. (2022). Chitosan and chitooligosaccharide: The promising non-plant-derived prebiotics with multiple biological activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6761. doi: 10.3390/ijms23126761

Guarnieri A., Triunfo M., Scieuzo C., Ianniciello D., Tafi E., Hahn T., et al. (2022). Antimicrobial properties of chitosan from different developmental stages of the bioconverter insect Hermetia illucens. Sci. Rep. 12, 8084. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12150-3

Gunal-Koroglu D., Karabulut G., Ozkan G., Yılmaz H., Gültekin-Subaşi B., and Capanoglu E. (2025). Allergenicity of alternative proteins: Reduction mechanisms and processing strategies. J. Agr. Food Chem. 73, 7522–7546. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5c00948

Guo T., Ouyang X., Xin Y., Wang Y., Zhang S., and Kong J. (2016). Characterization of a new cell envelope proteinase PrtP from Lactobacillus rhamnosus CGMCC11055. J. Agr. Food Chem. 64, 6985–6992. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03379

Hamerman E. J. (2016). Cooking and disgust sensitivity influence preference for attending insect-based food events. Appetite 96, 319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.029

IPIFF (2021). An overview of the European market of insects as feed. Available online at: https://ipiff.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Apr-27-2021-IPIFF_The-European-market-of-insects-as-feed.pdf (Accessed April 27, 2021).

Kim H., Cheon G. Y., Kim J. H., Choi R. Y., Kim I. W., Suh H. J., et al. (2024). Preparation of chitosan oligosaccharides from chitosan of tenebrio molitor and its prebiotic activity. Appl. Biol. Chem. 67, 84. doi: 10.1186/s13765-024-00937-z

Kipkoech C., Kinyuru J. N., Imathiu S., Meyer-Rochow V. B., and Roos N. (2021). In vitro study of cricket chitosan’s potential as a prebiotic and a promoter of probiotic microorganisms to control pathogenic bacteria in the human gut. Foods 10, 2310. doi: 10.3390/foods10102310

Kwon G. T., Yuk H. G., Lee S. J., Chung Y. H., Jang H. S., Yoo J. S., et al. (2020). Mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor L.) exuviae as a novel prebiotic material for BALB/c mouse gut microbiota. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 29, 531–537. doi: 10.1007/s10068-019-00699-1

Lee J. H., Kim T. K., Jeong C. H., Yong H. I., Cha J. Y., Kim B. K., et al. (2021). Biological activity and processing technologies of edible insects: a review. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 30, 1003–1023. doi: 10.1007/s10068-021-00942-8

Lee S. J., Kwon G. T., Chung Y. H., Yoo J. S., Cho K. H., Kim Y. S., et al. (2021). Study of fermented mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.) as a novel prebiotic for intestinal microbiota. Korean Soc Food Sci. Nut 50, 543–550. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2021.50.6.543

Nowakowski A. C., Miller A. C., Miller M. E., Xiao H., and Wu X. (2022). Potential health benefits of edible insects. Crit. Re. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 3499–3508. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1867053

Pinheiro N. A., Silva L. J., Pena A., and Pereira A. M. (2025). Entomophagy: nutritional value, benefits, regulation and food safety. Foods 14, 2380. doi: 10.3390/foods14132380

Refael G., Riess H. T., Levi C. S., Magzal F., Tamir S., Koren O., et al. (2022). Responses of the human gut microbiota to physiologically digested insect powders or isolated chitin thereof. Future Foods 6, 100197. doi: 10.1016/j.fufo.2022.100197

Scott K. P., Grimaldi R., Cunningham M., Sarbini S. R., Wijeyesekera A., Tang M. L., et al. (2020). Developments in understanding and applying prebiotics in research and practice—an ISAPP conference paper. J. Appl. Microbiol. 128, 934–949. doi: 10.1111/jam.14424

Siddiqui S. A., Zhao T., Fitriani A., Rahmadhia S. N., Alirezalu K., and Fernando I. (2024). Acheta domesticus (house cricket) as human foods-An approval of the European Commission-A systematic review. Food Front. 5, 435–473. doi: 10.1002/fft2.358

Siemianowska E., Kosewska A., Aljewicz M., Skibniewska K. A., Polak-Juszczak L., Jarocki A., et al. (2013). Larvae of mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.) as European novel food. Agric. Sci. 4, 287–291. doi: 10.4236/as.2013.46041

Sogari G., Menozzi D., and Mora C. (2019). The food neophobia scale and young adults’ intention to eat insect products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 43, 68–76. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12485

Tang C., Yang D., Liao H., Sun H., Liu C., Wei L., et al. (2019). Edible insects as a food source: a review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 1, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s43014-019-0008-1

Tao J. and Li Y. O. (2018). Edible insects as a means to address global malnutrition and food insecurity issues. Food Qual. Saf. 2, 17–26. doi: 10.1093/fqsafe/fyy001

Van Huis A. (2022). Edible insects: Challenges and prospects. Entomol. Res. 52, 161–177. doi: 10.1111/1748-5967.12582

WHO (2007). Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition: report of a joint FAO/WHO/UNU expert consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Technical Report Series No. 935, WHO.

Keywords: insect flour, prebiotic, functional ingredients, health effects, gut microbiota

Citation: Foti P, Sanfilippo RR and Romeo FV (2025) Exploring the prebiotic activity of edible insect flour: a sustainable functional food ingredient. Front. Ind. Microbiol. 3:1716542. doi: 10.3389/finmi.2025.1716542

Received: 30 September 2025; Accepted: 14 November 2025; Revised: 03 November 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Mukesh Yadav, Maharishi Markandeshwar University, IndiaReviewed by:

Nelson Mota De Carvalho, Escola Superior de Biotecnologia - Universidade Católica Portuguesa, PortugalCopyright © 2025 Foti, Sanfilippo and Romeo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Flora V. Romeo, ZmxvcmF2YWxlcmlhLnJvbWVvQGNyZWEuZ292Lml0

Paola Foti

Paola Foti Rosamaria R. Sanfilippo

Rosamaria R. Sanfilippo Flora V. Romeo

Flora V. Romeo