Abstract

Coral bleaching events are increasing in frequency, demanding examination of the physiological and molecular responses of scleractinian corals and their algal symbionts (Symbiodinium sp.) to stressors associated with bleaching. Here, we quantify the effects of long-term (95-day) thermal and CO2-acidification stress on photochemical efficiency of in hospite Symbiodinium within the coral Siderastrea siderea, along with corresponding coral color intensity, for corals from two reef zones (forereef, nearshore) on the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System. We then explore the molecular responses of in hospite Symbiodinium to these stressors via genome-wide gene expression profiling. Elevated temperatures reduced symbiont photochemical efficiencies and were highly correlated with coral color loss. However, photochemical efficiencies of forereef symbionts were more negatively affected by thermal stress than nearshore symbionts, suggesting greater thermal tolerance and/or reduced photodamage in nearshore corals. At control temperatures, CO2-acidification had little effect on symbiont physiology, although forereef symbionts exhibited constitutively higher photochemical efficiencies than nearshore symbionts. Gene expression profiling revealed that S. siderea were dominated by Symbiodinium goreaui (C1), except under thermal stress, which caused shifts to thermotolerant Symbiodinium trenchii (D1a). Comparative transcriptomics of conserved genes across the host and symbiont revealed few differentially expressed S. goreaui genes when compared to S. siderea, highlighting the host's role in the coral's response to environmental stress. Although S. goreaui transcriptomes did not vary in response to acidification stress, their gene expression was strongly dependent on reef zone, with forereef S. goreaui exhibiting enrichment of genes associated with photosynthesis. This finding, coupled with constitutively higher forereef S. goreaui photochemical efficiencies, suggests that functional differences in genes associated with primary production exist between reef zones.

Introduction

Dinoflagellates are ubiquitous unicellular algae that can occur as free-living cells, endosymbionts, or parasites across a wide variety of marine organisms. The most recognized among endosymbionts is the genus Symbiodinium, which establish obligate relationships with many reef-building corals (Trench and Blank, 1987). Photosynthetically-derived nutrients translocated from Symbiodinium to the host can yield up to 100% of the coral energy budget (Muscatine and Cernichiari, 1969; Muscatine, 1990), allowing for prolific coral growth in shallow oligotrophic tropical waters. In turn, Symbiodinium gain a protected microenvironment with access to light, inorganic nutrients, and dissolved inorganic carbon provided by the host (Muscatine and Cernichiari, 1969; Yellowlees et al., 2008; Wangpraseurt et al., 2014; Barott et al., 2015; Enríquez et al., 2017; Scheufen et al., 2017). Although initially considered a single species, advancements in genetics have uncovered nine divergent clades within Symbiodinium, designated A–I (Coffroth and Santos, 2005; Pochon and Gates, 2010; Thornhill et al., 2014), with additional evidence for significant within-clade genetic diversity (Howells et al., 2012; Pettay and Lajeunesse, 2013; Thornhill et al., 2017).

Increasing atmospheric pCO2 has reduced seawater pH, which impairs reef accretion (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007), and has increased sea surface temperatures, which can cause a breakdown of the coral-algal symbiosis—a process termed “coral bleaching” (Hoegh-Guldberg, 1999; Baker, 2003; Weis, 2008; Hoegh-Guldberg and Bruno, 2010). During bleaching, the coral is deprived of symbiont-derived organic carbon, which can lead to reduced growth, infection, and mortality. Bleaching events have been recognized as the primary driver of recent global coral reef degradation and have been increasing in frequency and severity over the past century (Pandolfi et al., 2011; Hughes et al., 2017). However, the rich genetic diversity of Symbiodinium often yields functional diversity, which may confer resilience to environmental change. For example, the composition of in hospite Symbiodinium communities can shift after bleaching disturbances (Baker, 2001; Thornhill et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2008; Kemp et al., 2014; Silverstein et al., 2015), which can strongly influence coral gene expression and future bleaching susceptibility (Desalvo et al., 2010a; Jones and Berkelmans, 2010; Howells et al., 2012). A more comprehensive understanding of how coral-Symbiodinium associations respond to ocean warming and acidification is needed to predict coral reef responses to global change.

Studies of Symbiodinium physiology document a wide array of stress responses to environmental change, including impairment/inactivation of photosynthesis at high temperatures (Iglesias-Prieto et al., 1992; Iglesias-Prieto and Trench, 1994), increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant activity in response to thermal and UV exposure (Lesser, 1996; Suggett et al., 2008; Gardner et al., 2017), and reduced symbiont pigment concentrations at low pH (Tremblay et al., 2013). In contrast to these strong physiological responses, there is mounting evidence that Symbiodinium lack strong transcriptional responses to global change stressors, which starkly contrasts their host's transcriptional response (Leggat et al., 2011; Barshis et al., 2014; Davies et al., 2016). Leggat et al. (2011) found that Symbiodinium exhibit few changes in expression of stress response genes under thermal stress when compared to these same genes in their coral host. Minimal transcriptomic responses have also been observed in both Symbiodinium types (ITS1, ITS2, and cp23-determined) D2 and C3K following heat exposure (Barshis et al., 2014), which contrasts widespread transcriptomic shifts observed in the coral host exposed to the same heat stress (Barshis et al., 2013).

Despite the unresponsiveness of Symbiodinium gene expression to stressors, transcriptome profiles were found to be highly divergent among Symbiodinium clades D2 and C3K, regardless of experimental treatment, providing evidence for functional differences amongst Symbiodinium lineages (Barshis et al., 2014). Functional differences inferred from transcriptomics have also been observed within Symbiodinium lineages. For example, comparative transcriptomics of a variety of clade B strains revealed strain-specific differences in expression (Parkinson et al., 2016), providing additional evidence that substantial transcriptomic functional variation exists within and across Symbiodinium lineages.

Clade C strains are the most derived Symbiodinium lineage and exhibit higher within-clade diversity when compared to other, more basal clades (Pochon et al., 2006; Pochon and Gates, 2010; Lesser et al., 2013; Thornhill et al., 2014, 2017). There is therefore great interest in understanding how this diversity within clade C Symbiodinium influences the coral's response to global change stressors. Transcriptomes of two divergent C1 lineages previously shown to exhibit distinct responses to thermal stress, both in hospite and in culture (Howells et al., 2012), revealed divergent expression patterns in response to heat stress, providing insights into how symbiont functional variation could lead to variation in coral thermal tolerance (Levin et al., 2016). Given the important role that coral host-Symbiodinium interactions play in a corals' response to environmental stress (Parkinson et al., 2015), it is critical to determine how each symbiotic partner responds to multiple stressors. However, few studies have explored whole transcriptome responses of different in hospite Symbiodinium populations to ocean warming and acidification, and even fewer have compared the responses of both symbiotic partners in parallel.

Here, we exposed the resilient and ubiquitous Caribbean reef-building coral Siderastrea siderea and its in hospite Symbiodinium from two different reef zones (nearshore and forereef) to thermal stress (Temperature = 25, 28, 32°C) and CO2-acidification stress (pCO2 = 324, 477, 604, 2553 μatm) for 95 days. Our previous work has shown that both elevated temperature and pCO2 elicited strong but divergent responses of the host's transcriptome (Davies et al., 2016), with increased temperatures substantially reducing calcification rates, with smaller declines observed in response to elevated pCO2 (Castillo et al., 2014). Here, we build on these studies by quantifying changes in coral color intensity, Symbiodinium photochemical efficiencies of photosystem II (Fv/Fm), and transcriptomic responses of Symbiodinium in hospite. We combine these physiological and transcriptomic observations of the symbiont with previously published observations of the host to advance our understanding of their combined response to thermal and acidification stress, thereby improving our ability to predict a corals' ecological trajectory in response to these global change stressors.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

Physiological measurements, transcriptomes, and gene expression analyses presented here build upon experiments previously published by Castillo et al. (2014) and Davies et al. (2016). Briefly, whole S. siderea colonies from nearshore (N = 6) and forereef (N = 6) reef zones were collected from the Belize Mesoamerican Barrier Reef (total colonies = 12) in July 2011 and transported to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Aquarium Research Center. At UNC, whole coral colonies were sectioned into 18 fragments, each of which were maintained in one of six experimental treatments (3 tanks per treatment; 18 tanks total). Treatments tested the effects of temperature and pCO2 independently. The pCO2 treatments corresponded to near-pre-industrial (P324: 324 ± 89 μatm, 28.14 ± 0.27°C), predicted end-of-century (P604: 604 ± 107 μatm, 28.04 ± 0.28°C), and an extreme mid-millennium scenario (P2553: 2553 ± 506 μatm, 27.93 ± 0.19°C). Temperature treatments spanned the monthly minimum and maximum seawater temperatures (T25: 25.01 ± 0.14°C, 515 ± 92 μatm; T28: 28.14 ± 0.27°C, 324 ± 89 μatm, T32: 32.01 ± 0.17°C, pCO2 472 ± 86 μatm) over the 2002–2014 interval (Castillo and Helmuth, 2005; Castillo and Lima, 2010; Castillo et al., 2012). The same treatment condition was used for pCO2 and temperature controls, which represented near-present-day pCO2 and annual mean temperature (Control: 477 ± 83 μatm, 28.16 ± 0.24°C). Tanks were illuminated with 250 μmol photons m−2 s−1 on a 12-h light-dark cycle for 95 days. Upon completion of the experiment, tissue (coral + symbiont) was extracted by water pick, immediately preserved in RNAlater, and stored at −80°C until RNA was extracted.

Symbiodinium physiology: coral color and photochemical efficiency

Coral color from standardized photographs has been historically used as an indicator of chlorophyll A concentration and symbiont density, and more generally as an indicator of coral bleaching (i.e., Winters et al., 2009; Kenkel et al., 2013; Chakravarti et al., 2017). Coral fragments were photographed with a standardized color scale at the end of the 95-day experiment prior to tissue extraction. Adobe Photoshop was first used to balance exposures, which were standardized across photographs using a white standard. Total red, green, blue, and sums of all color channel intensities (red, green, blue) were normalized relative to the standardized color scale in each photo and calculated for 10 quadrats of 25 × 25 pixels within each coral fragment as a measure of brightness, with higher brightness indicating a reduction in coral color (i.e., reduced symbiont density and chlorophyll a concentration). This analysis was performed following Winters et al. (2009) using the MATLAB macro “AnalyzeIntensity.” Resulting data were inverted so that higher values represent increased coral pigmentation (i.e., increased symbiont density and chlorophyll a concentration).

One-time measurements of the maximum photosynthetic efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm; where Fv = Fm – Fo; and Fv, Fm, and Fo are variable, maximum, and minimum fluorescence, respectively) were obtained on day 94 of the experiments with an underwater PAM fluorometer (saturation width 0.80 s of >5,000 μmol photon m−2 s−1 saturation light pulse; Diving-PAM, Walz, Germany) at 20:00 h, 2 h after daytime illumination ended to ensure that non-photochemical quenching was suppressed and that the corals were adequately dark-adapted (three measurements per coral fragment). Reductions in Fv/Fm values are indicative of sustained damage to the photosystem.

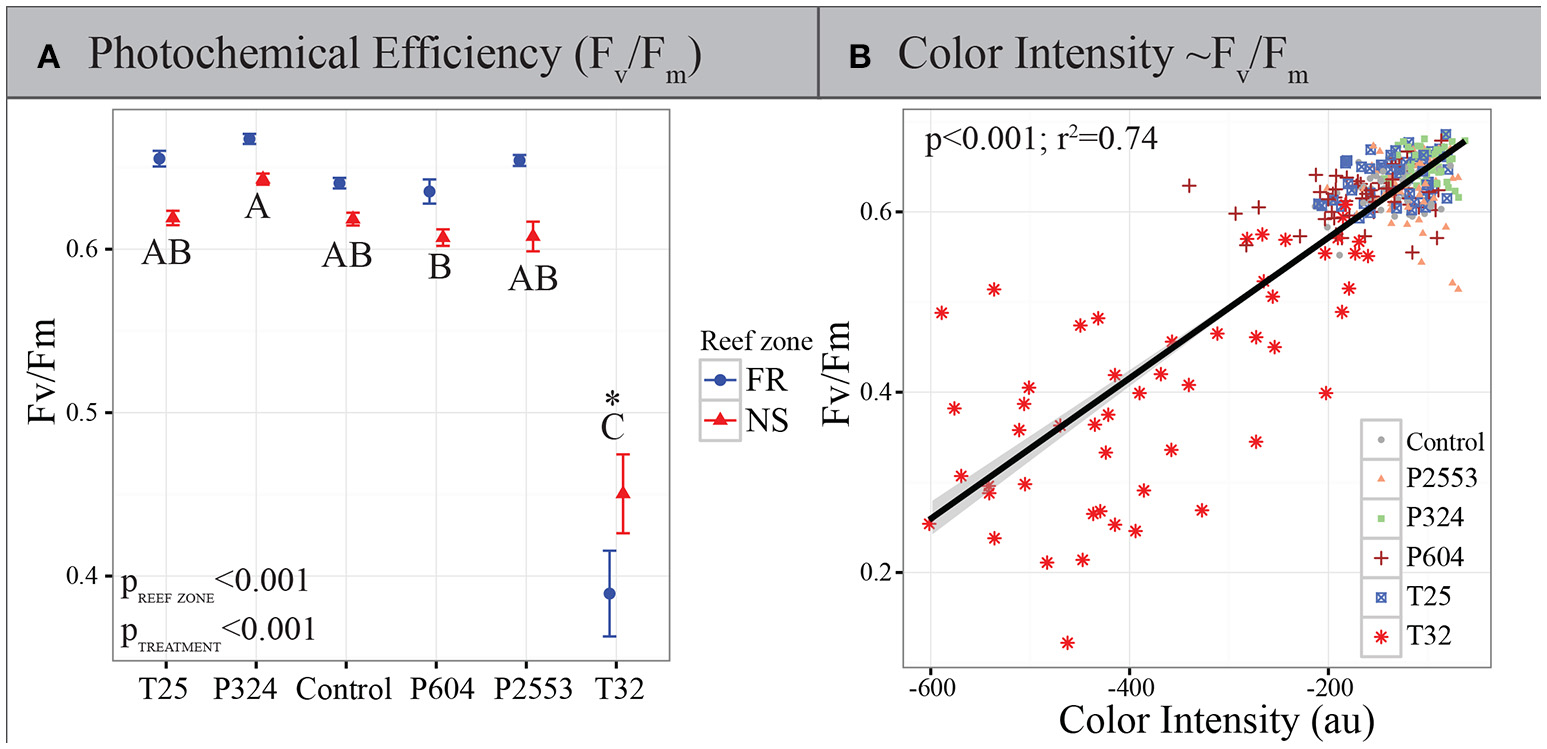

All statistical analyses were implemented in R (R Development Core Team, 2015) using the ANOVA function based on log-transformed sum of all color channels and Fv/Fm data. The sum of all channels was chosen as the color metric proxy here since these data correlated best with Fv/Fm (Figure 1B; Adjusted r2: 0.7366, p < 0.001). Experimental treatment and reef zone were modeled as fixed effects and significant differences across levels within factors were evaluated using post-hoc Tukey's HSD tests. All assumptions of parametric testing were explored using diagnostic plots in R.

Figure 1

Physiological measurements of in hospite Symbiodinium. (A) Photochemical efficiency of Symbiodinium photosystem II (PSII) (Fv/Fm) after 94 days in experimental treatments. Blue circles: forereef population average (±SE); red triangles: nearshore population average (±SE). Asterisk (*) indicates a significant interaction between treatment and reef zone. Treatment pairs lacking a letter in common indicate a statistically significant difference between those treatments pursuant to Tukey's Honest Significant Difference tests. High temperatures reduce Fv/Fm, however, symbionts from nearshore environments remain significantly higher than those from the forereef, while forereef symbionts exhibit higher Fv/Fm in all other treatments. (B) Maximum Fv/Fm of Symbiodinium vs. mean coral color intensity after 94 days in experimental treatments (T25 = 25.01 ± 0.14°C, 515 ± 92 μatm; Control = 28.16 ± 0.24°C, 477 ± 83 μatm; P324 = 28.14 ± 0.27°C, 324 ± 89 μatm; P604 = 28.04 ± 0.28°C, 604 ± 107 μatm; P2553 = 27.93 ± 0.19°C, 2553 ± 506 μatm; T32 = 32.01 ± 0.17°C, 472 ± 86 μatm), as measured by the sum of all color intensities in the red, green and blue channels in standardized coral photographs across all treatments. This relationship demonstrates that Fv/Fm and coral color (a proxy of bleaching) are highly correlated.

Transcriptome assembly, annotation, and Symbiodinium identification

Detailed descriptions of sequence library preparations, transcriptome assembly, and separation of host and symbiont contigs can be found in Davies et al. (2016). Briefly, RNA was isolated from 94 coral fragments and pooled by reef zone within each experimental treatment, yielding a total of 12 sequencing libraries (Table 1), each of which contained RNA from at least six fragments. Since each coral can host a community of Symbiodinium, RNA pooling is not expected to yield any additional complications compared to preparing each coral independently. Pooled libraries were prepared and sequencing was performed using four lanes of Illumina HiSeq 2000 at the UNC—Chapel Hill High Throughput Sequencing Facility, which yielded paired-end (PE) 100 bp reads (Table 1).

Table 1

| Sample | Pool | Reef zone | Temp (°C) | pCO2 (μatm) | PE reads (106) | Mapped (106) | Symbiont (106) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR_P324 | 6 | FR | 28.14 ± 0.27 | 324 ± 89 | 63.6 | 59.2 | 24.1 |

| FR_P604 | 6 | FR | 28.04 ± 0.28 | 604 ± 107 | 77.1 | 72.3 | 16.8 |

| FR_P2553 | 7 | FR | 27.93 ± 0.19 | 2553 ± 506 | 48.1 | 44.7 | 17.1 |

| NS_P324 | 6 | NS | 28.14 ± 0.27 | 324 ± 89 | 88.3 | 82.4 | 35.0 |

| NS_P604 | 8 | NS | 28.04 ± 0.28 | 604 ± 107 | 48.5 | 45.3 | 10.5 |

| NS_P2553 | 6 | NS | 27.93 ± 0.19 | 2553 ± 506 | 69.2 | 64.6 | 23.3 |

| FR_T25 | 11 | FR | 25.01 ± 0.17 | 515 ± 92 | 50.9 | 47.4 | 20.5 |

| FR_Control | 14 | FR | 28.16 ± 0.24 | 477 ± 83 | 63.2 | 58.8 | 24.3 |

| FR_T32 | 9 | FR | 32.01 ± 0.17 | 472 ± 86 | 50.0 | 47.2 | 1.2 |

| NS_T25 | 7 | NS | 25.01 ± 0.17 | 515 ± 92 | 100.0 | 93.1 | 39.9 |

| NS_Control | 7 | NS | 28.16 ± 0.24 | 477 ± 83 | 56.7 | 52.7 | 23.6 |

| NS_T32 | 7 | NS | 32.01 ± 0.17 | 472 ± 86 | 54.7 | 51.5 | 3.9 |

| TOTAL | 770.3 | 719.2 | 235.1 |

Summary of RNA libraries, including the number of corals from which RNA was pooled (“Pool”), reef zone where corals were collected (forereef = “FR” and nearshore = “NS”), temperature (°C) ±SD, pCO2 (μatm) ±SD, raw 100 bp paired-end reads (“PE Reads”), mapped reads to the coral host, and symbiont (“Mapped”) and total number of Symbiodinium goreaui-specific read counts (“Symbiont”).

Shaded samples were excluded from analyses due to low read counts arising from low RNA yields, resulting in the availability of 235.1 million reads for downstream analyses.

Transcriptome de novo assembly of over 770 million PE reads was completed using Trinity (Grabherr et al., 2011) and resulting contigs were assigned as either coral- or Symbiodinium-derived contigs using a translated blast search (tblastx) against host and symbiont specific databases (Davies et al., 2016). Symbiodinium-specific contigs were annotated by BLAST sequence homology searches against UniProt and Swiss-Prot NCBI NR protein databases with an e-value cutoff of e−5 (UniProt Consortium, 2015). Annotated sequences were then assigned to Gene Ontology (GO) categories. Transcriptome contiguity analysis (Martin and Wang, 2011) and Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs v2 (BUSCO; Simão et al., 2015) were used to assess Symbiodinium transcriptome quality and completeness.

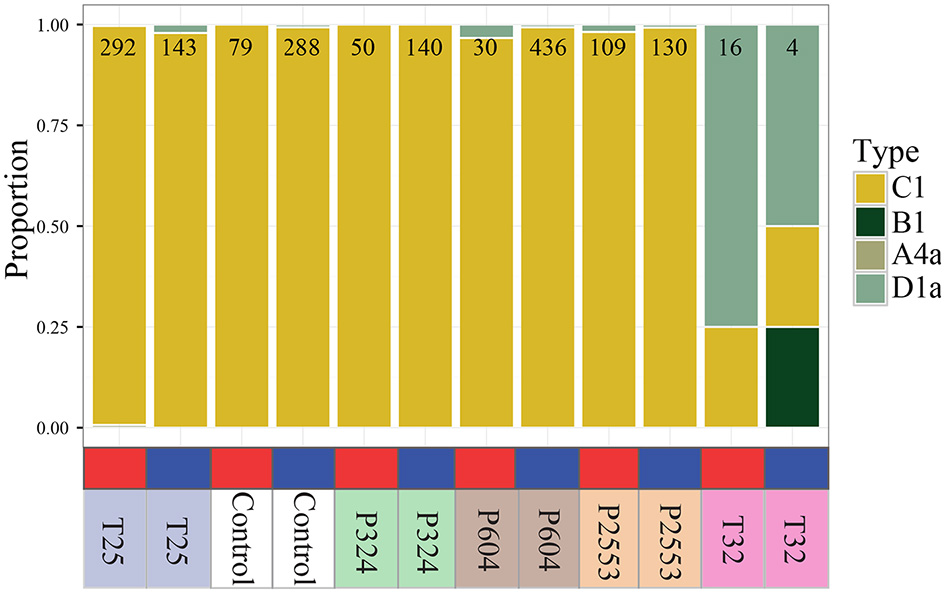

Symbiodinium community composition

To compare Symbiodinium expression across reef zones and experimental treatments, it was first necessary to determine which Symbiodinium lineages were present in each library. Reads were trimmed with Fastx_toolkit (<20 bp length cutoff and bp quality score >20) and resulting quality filtered reads were then mapped to an ITS2-specific database (Franklin et al., 2012) using Bowtie 2.2.0 with the—a flag to search all possible alignments (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). All possible alignments were identified and then the read was quantified in the analysis if all possible alignments for that read mapped to a single reference lineage. This analysis determined that 96.7–100% of mapped reads from 10 of the 12 libraries exclusively aligned to a single Symbiodinium lineage (Symbiodinium goreaui C1), with remaining libraries [nearshore 32°C (NS_T32) and forereef 32°C (FR_T32)] hosting divergent communities consisting of S. goreaui (C1) and Symbiodinium trenchii (D1a). However, these two libraries hosting divergent communities were excluded from downstream expression analysis due to temperature-induced symbiont loss causing low symbiont concentrations, which ultimately led to insufficient quantities of mapped Symbiodinium reads (1.2 and 3.9 million) relative to other libraries (10.5–39.9 million).

Mapping and differential expression analysis for Symbiodinium goreaui

Raw reads across samples ranged from 48.1 to 100.0 million PE 100 bp sequences. Quality filtered reads were mapped to the combined host-symbiont transcriptome (S. siderea + S. goreaui) and S. goreaui mapped reads ranged from 10.5 (NS_P604) to 39.9 (NS_T25) million (Table 1). Differential gene expression analyses were performed on raw counts with DESeq2 [v. 1.6.3; (Love et al., 2014) in R (v. 3.1.1; R Development Core Team, 2015)] using the model: design ~ reef zone + treatment. Raw counts are available in Supplementary Table 1. Counts were normalized for size factor differences and pairwise contrasts were computed for each treatment relative to the control and between the two reef zones. A contig was considered significantly differentially expressed if it had an average basemean expression >5 and an FDR adjusted p < 0.05 (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Raw counts were then rlog normalized, a principle coordinate analysis was performed, and the adonis function tested for overall expression differences across treatments and reef zones (Oksanen et al., 2018). Gene expression heatmaps with hierarchical clustering of expression profiles were created with the pheatmap package in R (Kolde, 2012). Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using the GO_MWU method, which uses adaptive clustering of GO categories and Mann–Whitney U-tests (Voolstra et al., 2011) based on a ranking of signed log p-values (Dixon et al., 2015). Results were plotted as a dendrogram, which traces the level of gene sharing between significant categories and lists the proportion of genes in the dataset with raw p < 0.05 relative to the total number of genes within the entire expression dataset.

Expression comparison across symbiotic partners

To compare expression across symbiotic partners, a subset of highly conserved genes (HCG) from the coral host (S. siderea) and S. goreaui were mined based on conserved gene annotation, which were determined based on BLAST sequence homology searches against UniProt and Swiss-Prot NCBI NR protein databases (e < e−5; UniProt Consortium, 2015 (N = 2,862 genes; Supplementary Table 2). Differential gene expression analyses were performed with DESeq2 using only count data from the HCG set (design ~ reef zone + partner.treatment) (Supplementary Table 3). Counts were normalized for size factor differences and pairwise contrasts were computed for each treatment relative to the control for each symbiotic partner. A contig was considered a significantly differentially expressed gene (DEG) if it had an average basemean expression >5 and an FDR adjusted p < 0.05 (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Significant DEGs were then compared across symbiotic partners. In order to confirm that S. goreaui gene expression results were not confounded by strong reef zone differences in expression, heatmaps were generated on the HCG panel that was significantly differentially expressed in the host but not the symbiont.

Results

Reef zone variation in Symbiodinium photophysiology

Long-term thermal stress treatments resulted in significantly reduced Fv/Fm of Symbiodinium (p < 0.001; Figure 1A), which was highly correlated with reductions in coral color intensity across all treatments (p < 0.001, r2 = 0.74; Figure 1B), but particularly in the high-temperature treatment (Adjusted r2: 0.6183, p < 0.001; Supplementary Figure 1A). Interestingly, Symbiodinium originating from nearshore habitats had significantly higher Fv/Fm under thermal stress when compared to forereef Symbiodinium (Tukey's HSD p = 0.008), suggesting increased photoacclimation or local adaptation of nearshore symbionts to warmer temperatures. However, nearshore Symbiodinium only exhibited significantly higher Fv/Fm compared to forereef symbionts in the 32°C treatment, although coral color intensity did not differ between reef zones under control conditions or under thermal stress (Supplementary Figure 1B). In all other experimental treatments, forereef symbionts had constitutively higher photochemical efficiencies (Figure 1A; p < 0.001).

Symbiodinium goreaui transcriptome

Sequencing data suggest that S. siderea predominately hosted S. goreaui (C1), which corroborates previous ITS2 sequencing work that found S. siderea from Belize hosts primarily C1 (Baumann et al., 2018). Although several clade C Symbiodinium transcriptomes are publicly available, we assembled a novel transcriptome since our samples were derived from S. siderea and clade C Symbiodinium are known to exhibit host specificity (Thornhill et al., 2014) and may therefore be divergent from previously assembled transcriptomes of clade C Symbiodinium hosted by the Pacific coral Acropora hyacinthus (Barshis et al., 2014) and the Caribbean anemone Discosoma sanctithomae (Rosic et al., 2015). A total of 1,255,626,250 reads were retained after adapter trimming and quality filtering (81.5%; 69.6% paired, 11.9% unpaired). The resulting metatranscriptome contained 333,835 contigs (N50 = 1,673), of which 65,838 were unambiguously assigned as Symbiodinium specific contigs, with an average length of 1,482 bp and an N50 of 1,746. Among symbiont contigs, 45,947 unique isogroups were obtained, of which 22,239 (48.4%) had gene annotations based on sequence homology. Thirty-nine percent of Symbiodinium contigs had protein coverage exceeding 0.75 (Supplementary Figure 1) and results from BUSCO suggest that 81.9% of complete and fragmented BUSCOs were present (77.6% complete, 4.3% fragmented), indicating that the transcriptome was fairly comprehensive. All raw reads are archived in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Short Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA307543, with transcriptome assembly and annotation files available at www.bco-dmo.org/project/635863.

Altered Symbiodinium communities under thermal stress

Analysis of sequencing libraries for Symbiodinium maintained at the low (25°C) and control (28°C) temperature treatments (for all pCO2 treatments) revealed that 96.7–100% of reads mapped exclusively to one clade (N = 30–436) aligned to S. goreaui (C1; Figure 2). Analysis of sequencing libraries for Symbiodinium maintained at high temperature treatments [nearshore 32°C (NS_T32); forereef 32°C (FR_T32)] consisted of divergent Symbiodinium communities hosting 50–75% Symbiodinium D1a (Figure 2). However, both libraries had very few mapped reads (NS_T32: 16, FR_T32: 4). Therefore, these two libraries were removed from all downstream gene expression analyses due to their divergent ITS2-derived communities, which have been shown to exhibit strong transcriptomic differences (Barshis et al., 2014). These libraries also had the lowest mapped Symbiodinium reads (Table 1), most likely due to reduced symbiont RNA available under thermal stress.

Figure 2

Proportion of RNAseq reads mapping exclusively to one Symbiodinium lineage (A4a, B1, C1, D1a) for each transcriptome library, with independent columns representing a unique transcriptome library. Number at top of bar indicates total number of reads mapping exclusively to one clade within that library. Red and blue blocks indicate that the library originated from nearshore and forereef corals, respectively. Treatment conditions are noted below the bar (T25 = 25.01 ± 0.14°C, 515 ± 92 μatm; Control = 28.16 ± 0.24°C, 477 ± 83 μatm; P324 = 28.14 ± 0.27°C, 324 ± 89 μatm; P604 = 28.04 ± 0.28°C, 604 ± 107 μatm; P2553 = 27.93 ± 0.19°C, 2553 ± 506 μatm; T32 = 32.01 ± 0.17°C, 472 ± 86 μatm). All libraries were dominated by Symbiodinium goreaui (C1), excepting the T32 treatments that were dominated by Symbiodinium trenchii (D1a).

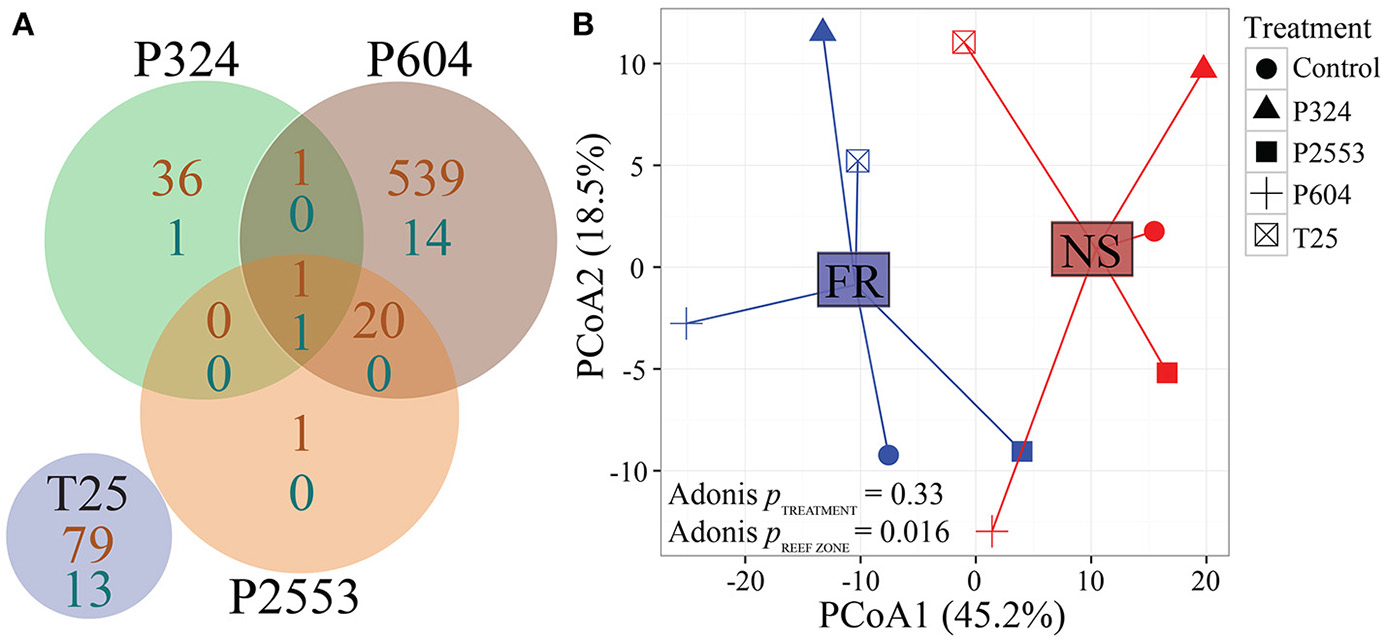

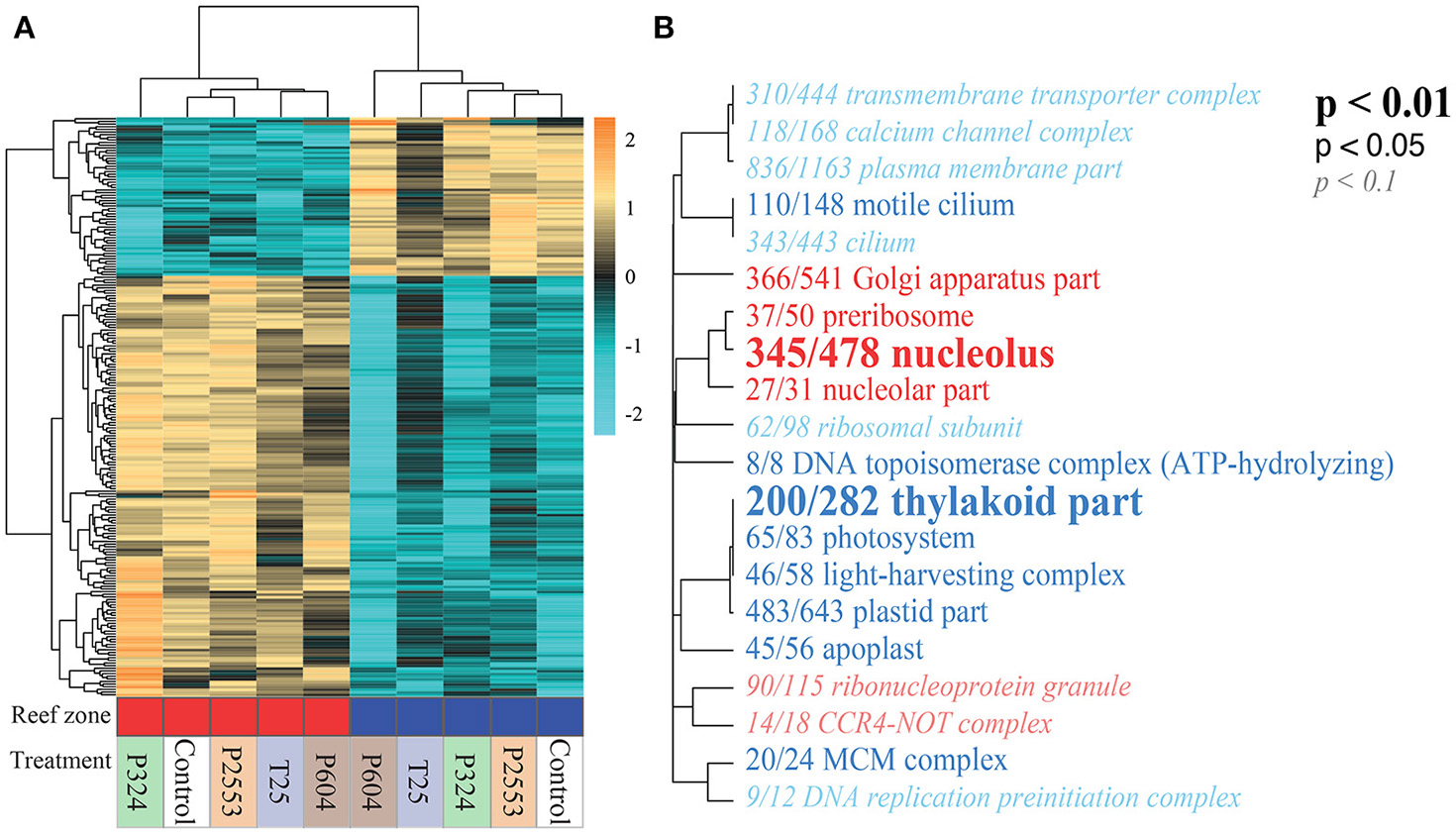

Minimal response to acidification stress, with population-specific differences in expression of genes associated with photosynthesis

Without consideration of the high temperature treatment libraries that were excluded due to low mapped reads, transcriptomic analysis of S. goreaui gene expression across the remaining treatments exhibited few DEGs relative to the control treatment, with 92 (25°C), 40 (324 μatm), 576 (604 μatm), and 23 (2,553 μatm) DEGs observed for the respective treatments relative to control treatments, representing a total of 1.69% of the entire transcriptome responding to any treatment (Figure 3A; Supplementary Table 4). In contrast, 24.45% of genes were differentially expressed with respect to reef zone, with 3,792 upregulated in nearshore specimens and 6,441 upregulated in forereef specimens, regardless of treatment condition—demonstrating a strong whole-transcriptomic response to reef zone (Figures 3B, 4A, p = 0.016; Supplementary Table 4). No significant differences in whole-transcriptome response were detected across experimental treatments (p = 0.33; Figure 3B). Gene ontology enrichment analysis across reef zones revealed many significantly enriched GO terms within cellular components, which were dominated by GO terms associated with photosynthesis in forereef S. goreaui [e.g., thylakoid part (GO:0044436), photosystem (GO:0009521), light-harvesting complex (GO:0030076), plastid part (GO:0044435)], suggesting fundamentally different regulation of photosynthetic genes across reef zones (Figure 4B). Genes associated with these GO categories can be found in Supplementary Table 5.

Figure 3

Global RNAseq patterns for in hospite Symbiodinium goreaui under different pCO2 (28°C) and low temperature (25°C) treatments. (A) Venn diagram of the number of differentially expressed S. goreaui genes (out of 45,947, FDR = 0.05) in experimental conditions relative to control conditions. Orange numbers indicate overrepresented genes and turquoise numbers indicate underrepresented genes, but overall very little transcriptomic response is observed. (B) Principal coordinate analysis of all r-log transformed isogroups clustered by experimental treatment and reef zone, demonstrating significantly different transcriptome profiles across S. goreaui from different locations, regardless of experimental treatment (NS = nearshore and FR = forereef; T25 = 25.01 ± 0.14°C, 515 ± 92 μatm; Control = 28.16 ± 0.24°C, 477 ± 83 μatm; P324 = 28.14 ± 0.27°C, 324 ± 89 μatm; P604 = 28.04 ± 0.28°C, 604 ± 107 μatm; P2553 = 27.93 ± 0.19°C, 2553 ± 506 μatm).

Figure 4

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of Symbiodinium goreaui across reef zones and treatments. (A) Heatmap for the top 300 DEGs for reef zone where each row is a gene and each column is a unique transcriptome library. The color scale is in log2 (fold change relative to the gene's mean) and genes and samples are clustered hierarchically based on Pearson's correlation of their expression across samples. Red and blue blocks indicate that libraries originated from nearshore and forereef corals, respectively. Treatment conditions are noted below the bar (T25 = 25.01 ± 0.14°C, 515 ± 92 μatm; Control = 28.16 ± 0.24°C, 477 ± 83 μatm; P324 = 28.14 ± 0.27°C, 324 ± 89 μatm; P604 = 28.04 ± 0.28°C, 604 ± 107 μatm; P2553 = 27.93 ± 0.19°C, 2553 ± 506 μatm). Hierarchical clustering of libraries (columns) demonstrates strong reef zone differences in gene expression. (B) Gene ontology (GO) enrichment of the “Cellular component (CC)” category derived from the transcriptomic differences across reef zones. Dendrograms depict sharing of genes between categories (categories with no branch length between them are subsets of each other), with the fractions corresponding to proportion of genes with an unadjusted p < 0.05 relative to the total number of genes within the category. Text size and boldness indicate the significance (Mann–Whitney U tests) of the term. Blue categories are enriched in forereef S. goreaui while red categories are enriched in nearshore S. goreaui. Forereef S. goreaui exhibit enrichment of GO categories associated with photosynthesis.

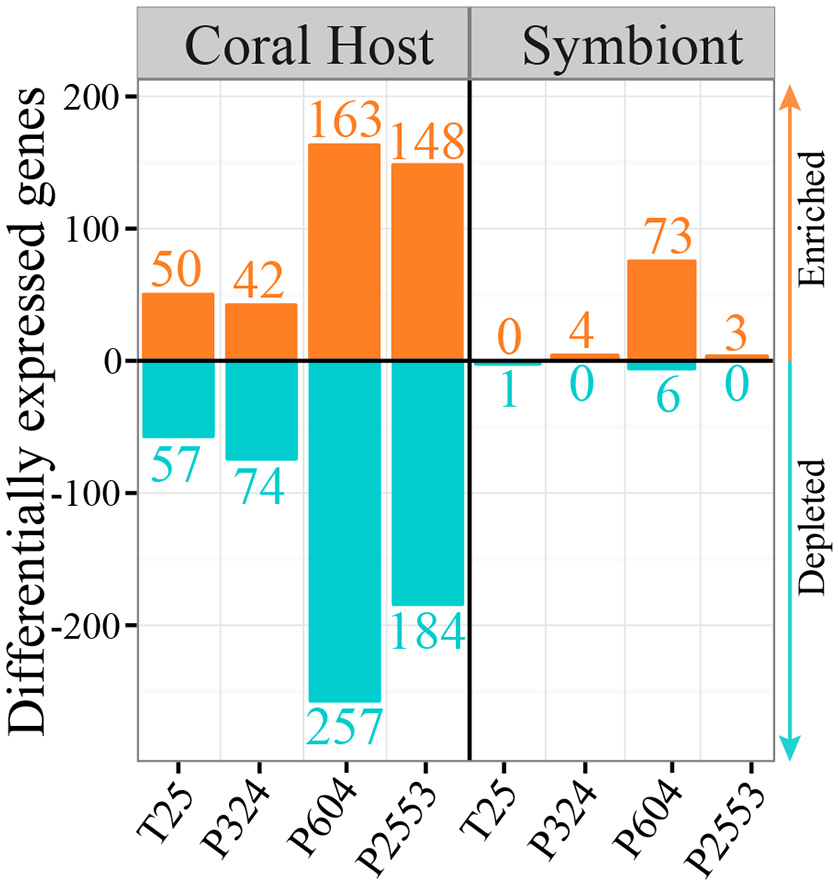

Coral host elicits stronger transcriptomic response than Symbiodinium goreaui

Contrasting gene expression patterns of the HCG sets of the coral host (S. siderea) and in hospite S. goreaui (N = 2,862; Supplementary Table 2) reveal that coral hosts were far more transcriptionally responsive to experimental treatments than their Symbiodinium partners (Figure 5). Among these HCGs, coral hosts modified expression by 3.7–15.7% across experimental treatments, while S. goreaui only modified expression by 0.05–2.8% across the same treatments, demonstrating that coral hosts were far more responsive to low temperature and acidification stress when compared to their algal symbionts (Figure 5). Heatmaps also confirmed that the lack of differential expression of HCG within S. goreaui was not driven by high levels of within-treatment variance arising from strong differences in S. goreaui gene expression across reef zones. Instead, genes that were highly differentially expressed in the host showed no differences in expression across reef zones for S. goreaui (Supplementary Figures 2A–D), although other genes within S. goreaui were differentially expressed across reef zone.

Figure 5

Barplot showing numbers of significantly (p < 0.05) differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for the host (left) and its algal symbiont Symbiodinium goreaui (right) across the four experimental treatments relative to the control for the 2862 highly conserved genes (HCG) across host and symbiont. Orange bars represent enriched genes and turquoise bars represent depleted genes in the treatment (T25 = 25.01 ± 0.14°C, 515 ± 92 μatm; P324 = 28.14 ± 0.27°C, 324 ± 89 μatm; P604 = 28.04 ± 0.28°C, 604 ± 107 μatm; P2553 = 27.93 ± 0.19°C, 2553 ± 506 μatm) relative to the control (28.16 ± 0.24°C, 477 ± 83 μatm). Overall, hosts exhibit a much stronger response across HCGs when compared to in hospite S. goreaui, regardless of experimental treatment.

Discussion

Increased thermotolerance of Siderastrea siderea from more thermally variable environments

Reductions in Symbiodinium photosynthetic ability have been strongly correlated with a lack of thermal tolerance and increased susceptibility to bleaching (Warner et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 2009; Howells et al., 2012). Here, we observed strong reductions in photochemical efficiency in response to elevated temperatures (Figure 1A), which has been consistently observed for Symbiodinium exposed to thermal stress (Warner et al., 1996; Roth, 2014). Strong reductions in calcification rate (Castillo et al., 2014) and overall host gene expression reflecting disruption of homeostasis (Davies et al., 2016) was previously observed for these same coral specimens in response to the prescribed thermal stress. These severe impairments in physiological measures of the host in response to chronic high temperatures might be driven, in part, by the observed reductions in symbiont photochemical efficiency (Figure 1A).

Notably, we observed that reductions in S. siderea symbiont photophysiology at 32°C were dependent on a coral's natal reef location, where the photochemical efficiency (Figure 1A) and coral color intensity (Figure 1B) of nearshore Symbiodinium were significantly higher under thermal stress than those of forereef Symbiodinium. Since Symbiodinium photophysiology is often associated with thermal tolerance (Warner et al., 1996, 1999; Ragni et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012), these fluctuating responses may be due to photoacclimation or adaptation of Symbiodinium to more thermally variable nearshore environments (Castillo and Helmuth, 2005; Baumann et al., 2016) or to variation in light availability across reef environments. Indeed, Castillo et al. (2012) observed reductions in linear extension rates over the past three decades of anthropogenic warming within cores of forereef S. siderea colonies, while cores of nearshore, and backreef colonies exhibited constant (nearshore) or increasing (backreef) extension rates over the same interval. Castillo et al. (2012) attributed these differential trends in linear extension to thermal preconditioning of backreef and nearshore corals, to the extent that nearshore and backreef environments experience more extreme baseline diurnal and seasonal fluctuations in seawater temperature compared to more thermally stable forereef environments. However, differences in light levels across reef environments and seasons have also been shown to influence cross-reef differences in a coral's response to anthropogenic warming and bleaching (Iglesias-Prieto et al., 2004) and may also contribute to Symbiodinium performance.

The potential for local adaption of Symbiodinium is thought to be high given their haploid genomes and short generation times (Santos and Coffroth, 2003; Correa and Baker, 2011). Howells et al. (2012) observed increased thermotolerance of Symbiodinium C1 originating from warmer reef locations, both in hospite and in culture, and Hume et al. (2016) detected strong selection for thermal tolerance in S. thermophilium, a lineage found in extreme temperatures of the Persian Gulf. Recent work has also revealed that Symbiodinium can rapidly evolve thermal tolerance in culture (Chakravarti et al., 2017), providing further evidence of Symbiodinium's potential for local adaptation to thermal stress. However, these variations in photochemical efficiencies in nearshore Symbiodinium may also be attributed to the relative changes in ITS2-determined symbiont communities [from S. goreaui (C1) to S. trenchii (D1a): Figure 2], which warrant future exploration.

Chronic high temperatures cause loss of symbiodinium goreaui

Symbiodinium genetic diversity has been reported to vary not only among different coral host species and environments, but also within a single species of coral (Baker, 2003; Coffroth and Santos, 2005; Thornhill et al., 2014, 2017). This genetic diversity has been shown to drive physiological variation within Symbiodinium (Iglesias-Prieto and Trench, 1994; Warner et al., 1999; Iglesias-Prieto et al., 2004) and numerous studies have demonstrated that thermo-tolerance varies amongst lineages of Symbiodinium (Robison and Warner, 2006; Suggett et al., 2008). Consequently, some lineages of Symbiodinium appear less affected by thermal stress, while others are impacted by even small changes in temperature (Rowan, 2004; Berkelmans and Van Oppen, 2006; Jones and Berkelmans, 2010; Hume et al., 2016).

Here, we observed that long-term thermal stress induced compositional shifts in Symbiodinium communities from S. goreaui (C1) to S. trenchii (D1a) in S. siderea, regardless of natal reef zone (Figure 2). However, this result is at least partially due to a loss of symbiosis with S. goreaui, rather than S. trenchii becoming more successful in hospite under increased temperatures since corals were exhibiting color loss evident of bleaching (Figure 1B). These results are consistent with prior work showing that S. siderea from southern Belize primarily host S. goreaui (C1) and S. trenchii (D1a) (Baumann et al., 2018), although Finney et al. (2010) also observed that shallow water S. siderea from Carrie Bow Caye (>100 km north of the sites sampled here) hosted Symbiodinium C3, which was not found here.

Symbiodinium trenchii (D1a) are generally associated with hosts from marginal reef environments exposed to increased thermal stress (Pettay et al., 2011, 2015; Pettay and Lajeunesse, 2013). Correspondingly, Pacific Acropora millepora corals hosting predominantly clade D Symbiodinium have been shown to exhibit greater thermal tolerance when compared to those corals hosting Symbiodinium C2 (Berkelmans and Van Oppen, 2006; Jones et al., 2008). However, there appears to be a trade-off associated with hosting more thermally tolerant symbionts, as A. millepora hosting clade D Symbiodinium were observed to grow significantly slower than corals hosting C2 under both control and field conditions (Jones and Berkelmans, 2010). Although it is unclear from the data at hand if the Symbiodinium communities tested here would shift back to being dominated by S. goreaui after the alleviation of thermal stress (Sampayo et al., 2016), these shifts could represent acclimation potential for corals exposed to future ocean warming (Cunning et al., 2015; Silverstein et al., 2015).

symbiodinium gene expression and photochemical efficiency are unresponsive to co2-induced acidification

Increases in atmospheric pCO2 have been shown to reduce calcification rates of reef-building corals (Kleypas et al., 1999; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007; Chan and Connolly, 2013; Castillo et al., 2014), but the effects of pCO2 on corals' algal symbionts are less clear. Some studies report that elevated pCO2 enhances Symbiodinium primary production, suggesting that the concentration of dissolved inorganic carbon in seawater—elevated under high pCO2–is the limiting substrate for photosynthesis (Crawley et al., 2010; Brading et al., 2011). In contrast, others have observed negative effects of increased pCO2 on Symbiodinium physiology, including reduced productivity, photochemical efficiency, and calcification (Anthony et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2016). Here, we observed minimal effects of elevated pCO2 on Symbiodinium photochemical efficiencies across a wide range of pCO2 conditions (Figure 1A). This lack of response starkly contrasts the strong physiological response (i.e., impaired photophysiology) and community shifts (i.e., C1–D1a) of Symbiodinium under increased temperatures (Figures 1, 2). One explanation for this lack of physiological response to pCO2 could be that the specific S. goreaui populations investigated here are simply not stressed by elevated pCO2, which has been observed for other Symbiodinium strains (Brading et al., 2011).

This lack of S. goreaui physiological response to acidification stress was also evident at the whole-transcriptome level, where no significant differences in overall gene expression were observed across low temperature and variable pCO2 treatments (Figure 3), even when reef zone-specific responses were considered (Supplementary Figure 2). This paucity of a transcriptional stress response in Symbiodinium in response to stress is consistent with previous studies, which generally observe little to no transcriptional responses to environmental stressors (Leggat et al., 2011; Putnam et al., 2013; Barshis et al., 2014), with the exception of extreme heat stress (Baumgarten et al., 2013; Levin et al., 2016; Gierz et al., 2017)—which we were unable to investigate here due to a combination of low symbiont RNA yield (Figure 1A) and compositional changes in Symbiodinium communities under elevated temperature (Figure 2).

Instead of responding transcriptionally, it has been proposed that Symbiodinium use post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, including translational regulation, and post-translational modifications, to drive molecular responses. Evidence suggests that very few transcription factors are present in Symbiodinium transcriptomes and genomes (Bayer et al., 2012; Shoguchi et al., 2013). Instead, it has been proposed that these algae utilize small RNAs and microRNAs, (Baumgarten et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2015), RNA-editing (Liew et al., 2017), and trans-splicing of spliced leader sequences (Zhang et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2010; Lin, 2011) to regulate their environmental stress responses. Another possibility is that the timescale of this study (95 days) was insufficient to trigger physiological and molecular responses in Symbiodinium. Although the stability of dinoflagellate mRNA is known to be considerably longer than for other organisms (Morey and Van Dolah, 2013), it is possible that physiological and transcriptomic responses were minimized by long-term acclimatization of Symbiodinium via phenotypic buffering (Reusch, 2014).

Lastly, and perhaps most likely, it could be that in hospite Symbiodinium simply do not respond to changes in pCO2 because their positions within host-derived tissue-bound spaces buffer the algae from external changes in pH (Rands et al., 1993; Venn et al., 2009; Barott et al., 2015). However, determination of the specific factor(s) that account for these results requires further examination, as they cannot be assessed with the data at hand.

Reef zone differences in photochemical efficiency and genes related to photosynthesis

Symbiodinium exist endosymbiotically across a variety of hosts and habitats, which presents these algae with diverse challenges with respect to photosynthesis and survival. Photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) is widely used as an indicator of photosynthetic performance and stress (Murchie and Lawson, 2013). Here, higher Fv/Fm values observed in forereef Symbiodinium relative to nearshore symbionts (Figure 1A) may indicate photoadaptation between the two populations of symbionts, since nearshore environments experience increased temperatures and nutrients along with reduced light levels relative to forereef habitats (Castillo and Lima, 2010; Baumann et al., 2016). These environmental differences may stimulate nearshore corals to rely more heavily on heterotrophy and dissolved/particulate organic matter relative to corals in light-replete forereef habitats (Grottoli et al., 2006; Tremblay et al., 2014).

It is important to note, however, that both nearshore and forereef Symbiodinium exhibited Fv/Fm > 0.6, which is generally considered healthy. Therefore, these data do not necessarily indicate that forereef hosts are receiving increased photo-assimilates from their Symbiodinium, which corroborates the comparable calcification rates for coral specimens from different reef zones within each experimental pCO2-temperature treatment (Castillo et al., 2014). Instead, because the photochemical efficiencies of symbionts from forereef and nearshore corals were divergent even after 95 days in the same experimental treatments, we speculate that the environment could have selected for distinct nearshore and forereef Symbiodinium “ecotypes” that reflect photoadaptation to their natal reef zone (Iglesias-Prieto et al., 2004; Howells et al., 2012; Chakravarti et al., 2017)—although further work is required to test this hypothesis. Another possibility is that S. goreaui populations from the nearshore and forereef reef zones represent distinct species, although analyses of higher resolution loci are required to test this hypothesis.

Notably, reef-zone-specific photochemical efficiencies were also reflected at the transcriptomic level, where consistent differences in gene expression were observed (Figures 3B, 4A). Divergent stable-state gene expression is perhaps not surprising given that transcriptomic differences across clades (Barshis et al., 2014; Rosic et al., 2015) and across strains within a clade (Parkinson et al., 2016) have been previously observed. Gene ontology enrichment analysis of differential gene expression across reef zones detected strong upregulation of genes related to photosynthesis in forereef symbionts (Figure 4B), corroborating our observation of higher photochemical efficiencies for forereef S. goreaui. These differences in regulation of photosynthesis-related genes across reef zone could facilitate the cross-reef-zone differences in physiological responses to thermal stress observed in the present study (Figure 1A).

Thermally sensitive Symbiodinium have been shown to exhibit increased disruption of PSII photochemistry (Warner et al., 1999; Robison and Warner, 2006), which has been associated with variations in the regulation of genes involved in photosynthesis (Mcginley et al., 2012). Given that investigations into the differences in gene expression amongst Symbiodinium lineages consistently observe enrichment of photosynthesis-related genes (Baumgarten et al., 2013; Barshis et al., 2014; Rosic et al., 2015; Parkinson et al., 2016; this study), we propose the evolution of unique photoadaptive Symbiodinium “ecotypes” that can be differentiated by their transcriptomic signatures of photosynthesis-related genes.

Coral hosts elicit stronger transcriptomic responses than symbiodinium goreaui

Understanding how each partner of the coral–Symbiodinium symbiosis responds to environmental stress is required to accurately predict the susceptibility of corals reefs to future global change (Weis, 2008). Although both partners exhibit a wide array of physiological stress responses, Symbiodinium are assumed to initiate symbiosis breakdown (Berkelmans and Van Oppen, 2006; Stat et al., 2006; Stat and Gates, 2011) due to their production of ROS, which can damage the host (Lesser, 1996; Weis, 2008). In contrast, S. siderea exhibit stronger transcriptomic responses to thermal and CO2-acidification stress than their Symbiodinium symbionts across a HCG (Supplementary Table 2) set (Figure 5), suggesting that symbiosis breakdown, or the process of “bleaching” in S. siderea, is initiated by the host instead of the symbiont. In addition, the observation that this color loss is associated with a shift from S. goreaui (C1) to the more thermotolerant S. trenchii (D1a) suggests that symbiont loss influences functional diversity of the symbiont community in a manner that supports thermal tolerance.

Strong transcriptomic responses of coral hosts are well-documented (Desalvo et al., 2010b; Meyer et al., 2011; Moya et al., 2012; Seneca and Palumbi, 2015; Davies et al., 2016), while Symbiodinium transcriptomic responses are generally more subtle (Leggat et al., 2011; Baumgarten et al., 2013; Barshis et al., 2014). For example, Barshis et al. (2014) similarly observed few transcriptional changes across >50,000 genes in response to thermal stress across two Symbiodinium lineages involved in symbiosis (D2, C3K), starkly contrasting the broad transcriptomic shifts observed in the symbiont's host when exposed to identical conditions (Barshis et al., 2013). As discussed above, S. goreaui in our study may be unresponsive to the stressors investigated, or the stressors may not have been applied long enough to elicit a transcriptomic response. Alternatively, transcriptomic stability of S. goreaui could result from in hospite buffering of the symbiosome under pCO2 stress, which has been observed in corals exposed to variable seawater pH (Rands et al., 1993; Venn et al., 2009; Barott et al., 2015) and in response to cold stress (Parkinson et al., 2015). Although potentially costly to the host, manipulation of Symbiodinium responses to stress through active regulation of the symbiont's environment might be favored over the potential chemical toxicity resulting from the release of reactive molecules by stressed Symbiodinium (e.g., Lesser, 1996).

Conclusion

Acclimation and adaptation play critical roles in determining an organism's ability to tolerate environmental variability (Schlichting and Pigliucci, 1996; Reusch, 2014). Here, we demonstrate that coral-associated Symbiodinium exhibit the potential for photoadaptation and/or photoacclimation to thermal and acidification stress. Photochemical efficiencies of S. goreaui from nearshore locations were more resilient to thermal stress when compared to forereef symbionts, suggestive of local adaptation across reef zones. We also observed differences in gene expression between S. goreaui from nearshore and forereef environments that were coupled with differences in photochemical efficiencies, irrespective of treatment condition. These transcriptomic differences suggest that photosynthesis-related gene expression varies by habitat, which may reflect photoadaptation to unique environments over potentially long timescales. Host retention of a more thermotolerant S. trenchii (D1a) under thermal stress was also documented, providing evidence for a potential mechanism of coral acclimation to thermal stress. Acclimation to pCO2 was also observed at both physiological and transcriptomic levels, the mechanism(s) of which have not yet been identified, although pH-buffering by the host remains a viable hypothesis. Thus, we find evidence for both photoadaptation and photoacclimation in the S. siderea-Symbiodinium symbiotic relationship, which may explain the relative resilience of this coral species to global change stressors.

Statements

Author contributions

KC and JR: Designed the study; AM: Completed all molecular preparations for sequencing; SD: Analyzed data with contributions from AM; SD: Wrote the paper with contributions from AM, JR, and KC.

Funding

Tank experiments were supported by NOAA award NA13OAR4310186 (to JR and KC) and NSF award OCE-1357665 (to JR), sequencing-related activities were supported by AM/KC/JR's start-ups and NSF award 1357665 (to JR), and salary/travel for SD was supported by AM/KC/JR's start-ups, NSF awards OCE-1437371, OCE-1459706 (to JR), and NSF OCE-1459522 (to KC). SD was a Simons Foundation Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation (LSRF) while completing this research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Belize Fisheries Department for all associated permits and Garbutt Marine for field assistance. B. Elder, E. Chow, K. Patel, R. Yost, and D. Shroff helped maintain experimental tanks and I. Westfield analyzed carbonate chemistry of the experimental treatments. N. Cohen and K. Delong conducted tissue preservations and H. Masters performed RNA isolations. Rafaela Granzotti conducted all coral color image analyses. In addition, we thank the two reviewers for their thorough critique on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2018.00150/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1(A) Maximum Fv/Fm of Symbiodinium vs. mean coral color intensity after 94 days under experimental heat stress (T32 = 32.01 ± 0.17°C, 472 ± 86 μatm), as measured by the sum of all color intensities in the red, green and blue channels in standardized coral photographs across all treatments. This relationship demonstrates that Fv/Fm and coral color are highly correlated under thermal stress. (B) Coral color intensity after 94 days in control and thermal stress conditions. Blue circles: forereef population average (±SE); red triangles: nearshore population average (±SE). High temperatures reduce coral color intensity, however, symbionts from nearshore and forereef corals do not differ significantly within a treatment.

Supplementary Figure 2Heatmaps for the expression of highly conserved genes (HCG) found to be differentially expressed in the coral host for each experimental treatment. The left four columns represent expression of these genes in the coral host (orange blocks) and the right four columns represent expression of these same genes in Symbiodinium goreaui (green blocks) across the experimental treatments relative to the control (28.16 ± 0.24°C, 477 ± 83 μatm): (A) low temperature (T25 = 25.01 ± 0.14°C, 515 ± 92 μatm), (B) pre-industrial pCO2 (P324 = 28.14 ± 0.27°C, 324 ± 89 μatm), (C) next-century pCO2 (P604 = 28.04 ± 0.28°C, 604 ± 107 μatm), and (D) extreme-high pCO2 (P2553 = 27.93 ± 0.19°C, 2553 ± 506 μatm). Red and blue blocks indicate that the library originated from nearshore and forereef reef zones, respectively. Each row is a gene and each column is a unique transcriptome library. The color scale is in log2 (fold change relative to the gene's mean) and genes are clustered hierarchically based on Pearson's correlation of their expression across samples. Results reveal lack of differential gene expression amongst experimental treatments relative to the control in S. goreaui, compared to strong differential gene expression amongst treatments in the host, and that this result is not due to differential gene expression amongst reef zones in S. goreaui.

Supplementary Table 1Raw Symbiont Counts.

Supplementary Table 2Normalized Counts of Highly Conserved Gene Set for Coral and Symbiont and their p values from DESeq2.

Supplementary Table 3Raw Counts Highly Conserved Gene Set for Coral and Symbiont.

Supplementary Table 4Symbiont normalized counts and gene expression results from DESeq2.

Supplementary Table 5Genes associated with photosynthetic GO categories in symbiont.

References

1

Anthony K. R. Kline D. I. Diaz-Pulido G. Dove S. Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2008). Ocean acidification causes bleaching and productivity loss in coral reef builders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.105, 17442–17446. 10.1073/pnas.0804478105

2

Baker A. C. (2001). Ecosystems - Reef corals bleach to survive change. Nature411, 765–766. 10.1038/35081151

3

Baker A. C. (2003). Flexibility and specificity in coral-algal symbiosis: diversity, ecology, and biogeography of Symbiodinium. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.34, 661–689. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132417

4

Barott K. L. Venn A. A. Perez S. O. Tambutté S. Tresguerres M. (2015). Coral host cells acidify symbiotic algal microenvironment to promote photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.112, 607–612. 10.1073/pnas.1413483112

5

Barshis D. J. Ladner J. T. Oliver T. A. Palumbi S. R. (2014). Lineage-specific transcriptional profiles of Symbiodinium spp. unaltered by heat stress in a coral host. Mol. Biol. Evol.31, 1343–1352. 10.1093/molbev/msu107

6

Barshis D. J. Ladner J. T. Oliver T. A. Seneca F. O. Traylor-Knowles N. Palumbi S. R. (2013). Genomic basis for coral resilience to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.110, 1387–1392. 10.1073/pnas.1210224110

7

Baumann J. H. Davies S. W. Aichelman H. E. Castillo K. D. (2018). Coral Symbiodinium community composition across the belize mesoamerican barrier reef system is influenced by host species and thermal variability. Microbial Ecol.75, 903–915. 10.1007/s00248-017-1096-6

8

Baumann J. H. Townsend J. E. Courtney T. A. Aichelman H. E. Davies S. W. Lima F. P. et al . (2016). Temperature regimes impact coral assemblages along environmental gradients on lagoonal reefs in Belize. PLoS ONE11:e0162098. 10.1371/journal.pone.0162098

9

Baumgarten S. Bayer T. Aranda M. Liew Y. J. Carr A. Micklem G. et al . (2013). Integrating microRNA and mRNA expression profiling in Symbiodinium microadriaticum, a dinoflagellate symbiont of reef-building corals. BMC Genomics14:704. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-704

10

Bayer T. Aranda M. Sunagawa S. Yum L. K. Desalvo M. K. Lindquist E. et al . (2012). Symbiodinium transcriptomes: genome insights into the dinoflagellate symbionts of reef-building corals. PLoS ONE7:e35269. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035269

11

Benjamini Y. Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B57, 289–300.

12

Berkelmans R. Van Oppen M. J. (2006). The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: a ‘nugget of hope’ for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.273, 2305–2312. 10.1098/rspb.2006.3567

13

Brading P. Warner M. E. Davey P. Smith D. J. Achterberg E. P. Suggett D. J. (2011). Differential effects of ocean acidification on growth and photosynthesis among phylotypes of Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae). Limnol. Oceanogr.56, 927–938. 10.4319/lo.2011.56.3.0927

14

Castillo K. D. Helmuth B. S. T. (2005). Influence of thermal history on the response of Montastraea annularis to short-term temperature exposure. Mar. Biol.148, 261–270. 10.1007/s00227-005-0046-x

15

Castillo K. D. Lima F. P. (2010). Comparison of in situ and satellite-derived (MODIS-Aqua/Terra) methods for assessing temperatures on coral reefs. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods8, 107–117. 10.4319/lom.2010.8.0107

16

Castillo K. D. Ries J. B. Bruno J. F. Westfield I. T. (2014). The reef-building coral Siderastrea siderea exhibits parabolic responses to ocean acidification and warming. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.281:20141856. 10.1098/rspb.2014.1856

17

Castillo K. D. Ries J. B. Weiss J. M. Lima F. P. (2012). Decline of forereef corals in response to recent warming linked to history of thermal exposure. Nat. Clim. Chang.2, 756–760. 10.1038/nclimate1577

18

Chakravarti L. J. Beltran V. H. Van Oppen M. J. H. (2017). Rapid thermal adaptation in photosymbionts of reef-building corals. Glob. Chang. Biol.23, 4675–4688. 10.1111/gcb.13702

19

Chan N. C. Connolly S. R. (2013). Sensitivity of coral calcification to ocean acidification: a meta-analysis. Glob. Chang. Biol.19, 282–290. 10.1111/gcb.12011

20

Coffroth M. A. Santos S. R. (2005). Genetic diversity of symbiotic dinoflagellates in the genus Symbiodinium. Protist156, 19–34. 10.1016/j.protis.2005.02.004

21

Correa A. M. S. Baker A. C. (2011). Disaster taxa in microbially mediated metazoans: how endosymbionts and environmental catastrophes influence the adaptive capacity of reef corals. Glob. Chang. Biol.17, 68–75. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02242.x

22

Crawley A. Kline D. I. Dunn S. Anthony K. Dove S. (2010). The effect of ocean acidification on symbiont photorespiration and productivity in Acropora formosa. Glob. Chang. Biol.16, 851–863. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01943.x

23

Cunning R. Silverstein R. N. Baker A. C. (2015). Investigating the causes and consequences of symbiont shuffling in a multi-partner reef coral symbiosis under environmental change. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.282:20141725. 10.1098/rspb.2014.1725

24

Davies S. W. Marchetti A. Ries J. B. Castillo K. D. (2016). Thermal and pCO2 stress elicit divergent transcriptomic responses in a resilient coral. Front. Mar. Sci.3:112. 10.3389/fmars.2016.00112

25

Desalvo M. K. Sunagawa S. Fisher P. L. Voolstra C. R. Iglesias-Prieto R. Medina M. (2010a). Coral host transcriptomic states are correlated with Symbiodinium genotypes. Mol. Ecol.19, 1174–1186. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04534.x

26

Desalvo M. K. Sunagawa S. Voolstra C. R. Medina M. (2010b). Transcriptomic responses to heat stress and bleaching in the elkhorn coral Acropora palmata. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.402, 97–113. 10.3354/meps08372

27

Dixon G. B. Davies S. W. Aglyamova G. A. Meyer E. Bay L. K. Matz M. V. (2015). Genomic determinants of coral heat tolerance across latitudes. Science348, 1460–1462. 10.1126/science.1261224

28

Enríquez S. Méndez E. R. Hoegh-Guldberg O. Iglesias-Prieto R. (2017). Key functional role of the optical properties of coral skeletons in coral ecology and evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.284:20161667. 10.1098/rspb.2016.1667

29

Finney J. C. Pettay D. T. Sampayo E. M. Warner M. E. Oxenford H. A. Lajeunesse T. C. (2010). The relative significance of host-habitat, depth, and geography on the ecology, endemism, and speciation of coral endosymbionts in the genus symbiodinium. Microb. Ecol.60, 250–263. 10.1007/s00248-010-9681-y

30

Franklin E. C. Stat M. Pochon X. Putnam H. M. Gates R. D. (2012). GeoSymbio: a hybrid, cloud-based web application of global geospatial bioinformatics and ecoinformatics for Symbiodinium-host symbioses. Mol. Ecol. Resour.12, 369–373. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03081.x

31

Gardner S. G. Raina J. B. Ralph P. J. Petrou K. (2017). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and dimethylated sulphur compounds in coral explants under acute thermal stress. J. Exp. Biol.220(Pt 10):1787–1791. 10.1242/jeb.153049

32

Gierz S. L. Forêt S. Leggat W. (2017). Transcriptomic analysis of thermally stressed symbiodinium reveals differential expression of stress and metabolism genes. Front. Plant Sci.8:271. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00271

33

Grabherr M. G. Haas B. J. Yassour M. Levin J. Z. Thompson D. A. Amit I. et al . (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol.29, 644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883

34

Grottoli A. G. Rodrigues L. J. Palardy J. E. (2006). Heterotrophic plasticity and resilience in bleached corals. Nature440, 1186–1189. 10.1038/nature04565

35

Hoegh-Guldberg O. (1999). Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world's coral reefs. Mar. Freshw. Res.50, 839–866. 10.1071/MF99078

36

Hoegh-Guldberg O. Bruno J. F. (2010). The impact of climate change on the world's marine ecosystems. Science328, 1523–1528. 10.1126/science.1189930

37

Hoegh-Guldberg O. Mumby P. J. Hooten A. J. Steneck R. S. Greenfield P. Gomez E. et al . (2007). Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science318, 1737–1742. 10.1126/science.1152509

38

Howells E. J. Beltran V. H. Larsen N. W. Bay L. K. Willis B. Van Oppen M. J. (2012). Coral thermal tolerance shaped by local adaptation of photosymbionts. Nat. Clim. Chang.2, 116–120. 10.1038/nclimate1330

39

Hughes T. P. Kerry J. T. Álvarez-Noriega M. Álvarez-Romero J. G. Anderson K. D. Baird A. H. et al . (2017). Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature543, 373–377. 10.1038/nature21707

40

Hume B. C. Voolstra C. R. Arif C. D'angelo C. Burt J. A. Eyal G. et al . (2016). Ancestral genetic diversity associated with the rapid spread of stress-tolerant coral symbionts in response to Holocene climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.113, 4416–4421. 10.1073/pnas.1601910113

41

Iglesias-Prieto R. Beltrán V. H. Lajeunesse T. C. Reyes-Bonilla H. Thome P. E. (2004). Different algal symbionts explain the vertical distribution of dominant reef corals in the eastern Pacific. Proc. Biol. Sci.271, 1757–1763. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2757

42

Iglesias-Prieto R. Matta J. L. Robins W. A. Trench R. K. (1992). Photosynthetic response to elevated-temperature in the symbiotic dinoflagellate symbiodinium-microadriaticum in culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.89, 10302–10305. 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10302

43

Iglesias-Prieto R. Trench R. K. (1994). Acclimation and adaptation to irradiance in symbiotic dinoflagellates.1. Responses of the photosynthetic unit to changes in photon flux-density. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.113, 163–175. 10.3354/meps113163

44

Jones A. Berkelmans R. (2010). Potential costs of acclimatization to a warmer climate: growth of a reef coral with heat tolerant vs. sensitive symbiont types. PLoS ONE5:e10437. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010437.

45

Jones A. M. Berkelmans R. Van Oppen M. J. Mieog J. C. Sinclair W. (2008). A community change in the algal endosymbionts of a scleractinian coral following a natural bleaching event: field evidence of acclimatization. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.275, 1359–1365. 10.1098/rspb.2008.0069

46

Kemp D. W. Hernandez-Pech X. Iglesias-Prieto R. Fitt W. K. Schmidt G. W. (2014). Community dynamics and physiology of Symbiodinium spp. before, during, and after a coral bleaching event. Limnol. Oceanogr.59, 788–797. 10.4319/lo.2014.59.3.0788

47

Kenkel C. D. Goodbody-Gringley G. Caillaud D. Davies S. W. Bartels E. Matz M. V. (2013). Evidence for a host role in thermotolerance divergence between populations of the mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides) from different reef environments. Mol. Ecol.22, 4335–4348. 10.1111/mec.12391

48

Kleypas J. A. Buddemeier R. W. Archer D. Gattuso J. P. Langdon C. Opdyke B. N. (1999). Geochemical consequences of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on coral reefs. Science284, 118–120. 10.1126/science.284.5411.118

49

Kolde R. (2012). pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. R package version 0.6.1. Available online at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap

50

Langmead B. Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods9, 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923

51

Leggat W. Seneca F. Wasmund K. Ukani L. Yellowlees D. Ainsworth T. D. (2011). Differential responses of the coral host and their algal symbiont to thermal stress. PLoS ONE6:e26687. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026687

52

Lesser M. P. (1996). Acclimation of phytoplankton to UV-B radiation: oxidative stress and photoinhibition of photosynthesis are not prevented by UV-absorbing compounds in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum micans. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.132, 287–297. 10.3354/meps132287

53

Lesser M. P. Stat M. Gates R. D. (2013). The endosymbiotic dinoflagellates (Symbiodinium sp.) of corals are parasites and mutualists. Coral Reefs32, 603–611. 10.1007/s00338-013-1051-z

54

Levin R. A. Beltran V. H. Hill R. Kjelleberg S. Mcdougald D. Steinberg P. D. et al . (2016). Sex, scavengers, and chaperones: transcriptome secrets of divergent symbiodinium thermal tolerances. Mol. Biol. Evol.33, 3032–3032. 10.1093/molbev/msw201

55

Liew Y. Li Y. Baumgarten S. Voolstra C. R. Aranda M. (2017). Condition-specific RNA editing in the coral symbiont Symbiodinium microadriaticum. PLoS Genet.13:e1006619. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006619

56

Lin S. J. (2011). Genomic understanding of dinoflagellates. Res. Microbiol.162, 551–569. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.04.006

57

Lin S. J. Cheng S. F. Song B. Zhong X. Lin X. Li W. J. et al . (2015). The Symbiodinium kawagutii genome illuminates dinoflagellate gene expression and coral symbiosis. Science350, 691–694. 10.1126/science.aad0408

58

Lin S. Zhang H. Zhuang Y. Tran B. Gill J. (2010). Spliced leader-based metatranscriptomic analyses lead to recognition of hidden genomic features in dinoflagellates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.107, 20033–20038. 10.1073/pnas.1007246107

59

Love M. I. Huber W. Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

60

Martin J. A. Wang Z. (2011). Next-generation transcriptome assembly. Nat. Rev. Genet.12, 671–682. 10.1038/nrg3068

61

Mcginley M. P. Aschaffenburg M. D. Pettay D. T. Smith R. T. Lajeunesse T. C. Warner M. E. (2012). Transcriptional response of two core photosystem genes in Symbiodinium spp. exposed to thermal stress. PLoS ONE7:e50439. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050439

62

Meyer E. Aglyamova G. V. Matz M. V. (2011). Profiling gene expression responses of coral larvae (Acropora millepora) to elevated temperature and settlement inducers using a novel RNA-Seq procedure. Mol. Ecol.20, 3599–3616. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05205.x

63

Morey J. S. Van Dolah F. M. (2013). Global analysis of mRNA half-lives and de novo transcription in a dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis. PLoS ONE8:e66347. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066347

64

Moya A. Huisman L. Ball E. E. Hayward D. C. Grasso L. C. Chua C. M. et al . (2012). Whole transcriptome analysis of the coral Acropora millepora reveals complex responses to CO(2)−driven acidification during the initiation of calcification. Mol. Ecol.21, 2440–2454. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05554.x

65

Murchie E. H. Lawson T. (2013). Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: a guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. J. Exp. Bot.64, 3983–3998. 10.1093/jxb/ert208

66

Muscatine L. (1990). The role of symbiotic algae in carbon and energy flux in reef corals. Ecosyst. World25, 75–87.

67

Muscatine L. Cernichiari E. (1969). Assimilation of photosynthetic products of zooxanthellae by a reef coral. Biol. Bull.137, 506–523. 10.2307/1540172

68

Oksanen J. Blanchet F. G. Kindt R. Legendre P. Minchin P. R. O'hara R. B. et al . (2018). vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.5-1. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

69

Pandolfi J. M. Connolly S. R. Marshall D. J. Cohen A. L. (2011). Projecting coral reef futures under global warming and ocean acidification. Science333, 418–422. 10.1126/science.1204794

70

Parkinson J. E. Banaszak A. T. Altman N. S. Lajeunesse T. C. Baums I. B. (2015). Intraspecific diversity among partners drives functional variation in coral symbioses. Sci. Rep.5:15667. 10.1038/srep15667

71

Parkinson J. E. Baumgarten S. Michell C. T. Baums I. B. Lajeunesse T. C. Voolstra C. R. (2016). Gene expression variation resolves species and individual strains among coral-associated dinoflagellates within the genus symbiodinium. Genome Biol. Evol.8, 665–680. 10.1093/gbe/evw019

72

Pettay D. T. Lajeunesse T. C. (2013). Long-range dispersal and high-latitude environments influence the population structure of a “stress-tolerant” dinoflagellate endosymbiont. PLoS ONE8:e79208. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079208

73

Pettay D. T. Wham D. C. Pinzón J. H. Lajeunesse T. C. (2011). Genotypic diversity and spatial-temporal distribution of Symbiodinium clones in an abundant reef coral. Mol. Ecol.20, 5197–5212. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05357.x

74

Pettay D. T. Wham D. C. Smith R. T. Iglesias-Prieto R. Lajeunesse T. C. (2015). Microbial invasion of the Caribbean by an Indo-Pacific coral zooxanthella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.112, 7513–7518. 10.1073/pnas.1502283112

75

Pochon X. Gates R. D. (2010). A new Symbiodinium clade (Dinophyceae) from soritid foraminifera in Hawai'i. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.56, 492–497. 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.03.040

76

Pochon X. Montoya-Burgos J. I. Stadelmann B. Pawlowski J. (2006). Molecular phylogeny, evolutionary rates, and divergence timing of the symbiotic dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.38, 20–30. 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.028

77

Putnam H. M. Mayfield A. B. Fan T. Y. Chen C. S. Gates R. D. (2013). The physiological and molecular responses of larvae from the reef-building coral Pocillopora damicornis exposed to near-future increases in temperature and pCO(2). Mar. Biol.160, 2157–2173. 10.1007/s00227-012-2129-9

78

Ragni M. Airs R. L. Hennige S. J. Suggett D. J. Warner M. E. Geider R. J. (2010). PSII photoinhibition and photorepair in Symbiodinium (Pyrrhophyta) differs between thermally tolerant and sensitive phylotypes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.406, 57–70. 10.3354/meps08571

79

Rands M. L. Loughman B. C. Douglas A. E. (1993). The Symbiotic interface in an alga invertebrate symbiosis. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.253, 161–165. 10.1098/rspb.1993.0097

80

R Development Core Team (2015). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

81

Reusch T. B. (2014). Climate change in the oceans: evolutionary versus phenotypically plastic responses of marine animals and plants. Evol. Appl.7, 104–122. 10.1111/eva.12109

82

Robison J. D. Warner M. E. (2006). Differential impacts of photoacclimation and thermal stress on the photobiology of four different phylotypes of Symbiodinium (Pyrrhophyta). J. Phycol.42, 568–579. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00232.x

83

Rosic N. Ling E. Y. Chan C. K. Lee H. C. Kaniewska P. Edwards D. et al . (2015). Unfolding the secrets of coral-algal symbiosis. ISME J.9, 844–856. 10.1038/ismej.2014.182

84

Roth M. S. (2014). The engine of the reef: photobiology of the coral-algal symbiosis. Front. Microbiol.5:422. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00422

85

Rowan R. (2004). Coral bleaching - thermal adaptation in reef coral symbionts. Nature430, 742–742. 10.1038/430742a

86

Sampayo E. M. Ridgway T. Franceschinis L. Roff G. Hoegh-Guldberg O. Dove S. (2016). Coral symbioses under prolonged environmental change: living near tolerance range limits. Sci. Rep.6:36271. 10.1038/srep36271

87

Santos S. R. Coffroth M. A. (2003). Molecular genetic evidence that dinoflagellates belonging to the genus symbiodinium freudenthal are haploid. Biol. Bull.204, 10–20. 10.2307/1543491

88

Scheufen T. Iglesias-Prieto R. Enriquez S. (2017). Changes in the number of symbionts and Symbiodinium cell pigmentation modulate differentially coral light absorption and photosynthesis performance. Front. Mar. Sci.4:309. 10.3389/fmars.2017.00309

89

Schlichting C. Pigliucci M. (1996). Phenotypic Evolution: A Reaction Norm Perspective.Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

90

Seneca F. O. Palumbi S. R. (2015). The role of transcriptome resilience in resistance of corals to bleaching. Mol. Ecol.24, 1467–1484. 10.1111/mec.13125

91

Shoguchi E. Shinzato C. Kawashima T. Gyoja F. Mungpakdee S. Koyanagi R. et al . (2013). Draft assembly of the Symbiodinium minutum nuclear genome reveals dinoflagellate gene structure. Curr. Biol.23, 1399–1408. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.062

92

Silverstein R. N. Cunning R. Baker A. C. (2015). Change in algal symbiont communities after bleaching, not prior heat exposure, increases heat tolerance of reef corals. Glob. Chang. Biol.21, 236–249. 10.1111/gcb.12706

93

Simão F. A. Waterhouse R. M. Ioannidis P. Kriventseva E. V. Zdobnov E. M. (2015). BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics31, 3210–3212. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351

94

Stat M. Carter D. Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2006). The evolutionary history of Symbiodinium and scleractinian hosts - symbiosis, diversity, and the effect of climate change. Pers. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst.8, 23–43. 10.1016/j.ppees.2006.04.001

95

Stat M. Gates R. D. (2011). Clade D Symbiodinum in scleractinian corals: a “nugget” of hope, a selfish opportunist, an ominous sign, or all of the above. Mar. Biol.2011, 1–9. 10.1155/2011/730715

96

Suggett D. J. Warner M. E. Smith D. J. Davey P. Hennige S. Baker N. R. (2008). Photosynthesis and production of hydrogen peroxide by Symbiodinium (Pyrrhophyta) phylotypes with different thermal tolerances. J. Phycol.44, 948–956. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2008.00537.x

97

Takahashi S. Whitney S. M. Badger M. R. (2009). Different thermal sensitivity of the repair of photodamaged photosynthetic machinery in cultured Symbiodinium species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.106, 3237–3242. 10.1073/pnas.0808363106

98

Thornhill D. J. Howells E. J. Wham D. C. Steury T. D. Santos S. R. (2017). Population genetics of reef coral endosymbionts (Symbiodinium, Dinophyceae). Mol. Ecol.26, 2640–2659. 10.1111/mec.14055

99

Thornhill D. J. Lajeunesse T. C. Kemp D. W. Fitt W. K. Schmidt G. W. (2006). Multi-year, seasonal genotypic surveys of coral-algal symbioses reveal prevalent stability or post-bleaching reversion. Mar. Biol.148, 711–722. 10.1007/s00227-005-0114-2

100

Thornhill D. J. Lewis A. M. Wham D. C. Lajeunesse T. C. (2014). Host-specialist lineages dominate the adaptive radiation of reef coral endosymbionts. Evolution68, 352–367. 10.1111/evo.12270

101

Tremblay P. Fine M. Maguer J. F. Grover R. Ferrier-Pages C. (2013). Photosynthate translocation increases in response to low seawater pH in a coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Biogeosciences10, 3997–4007. 10.5194/bg-10-3997-2013

102

Tremblay P. Grover R. Maguer J. F. Hoogenboom M. Ferrier-Pages C. (2014). Carbon translocation from symbiont to host depends on irradiance and food availability in the tropical coral Stylophora pistillata. Coral Reefs33, 1–13. 10.1007/s00338-013-1100-7

103

Trench R. K. Blank R. J. (1987). Symbiodinium microadriaticum Fredenthal, S. Goreau sp. nov., S. Kawagut2 sp. nov., and S. pilosum sp. nov.: gymnodinoid dinoflagellate symbionts of marine invertebrates. J. Phycol.23, 469–481. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1987.tb02534.x

104

UniProt Consortium (2015). UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res.43, D204–D212. 10.1093/nar/gku989

105

Venn A. A. Tambutté E. Lotto S. Zoccola D. Allemand D. Tambutte S. (2009). Imaging intracellular pH in a reef coral and symbiotic anemone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.106, 16574–16579. 10.1073/pnas.0902894106

106

Voolstra C. R. Sunagawa S. Matz M. V. Bayer T. Aranda M. Buschiazzo E. et al . (2011). Rapid evolution of coral proteins responsible for interaction with the environment. PLoS ONE6:e20392. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020392

107