Abstract

We evaluated connectivity, resiliency, and spatiotemporal variation in fish associations between the Tramandal River estuary (TRE) and the adjacent coast (AC). This was based on intermittent and seasonal data covering a discontinuous 21-year period (1995 to 2016) obtained using a standard beach seine with replicate samples collected at several points. In the TRE (405 samples; 42,987 individuals) 55 species were captured. In the AC (297 samples; 54,295 individuals) 41 species were captured. After data standardization the expected richness of the TRE [E(S) = 18.2] was significantly greater (P < 0.05) than that of the AC [E(S) = 14.4]. The fish association structure and distribution patterns in TRE and AC were dynamic and interconnected but quite different in terms of species composition, especially due to the influence of local salinity. The TRE association was richer in a number of species but numerically dominated by marine estuarine-dependent juveniles. The AC association was represented by a few typical marine species in addition to a couple of estuarine-related transient species who used the surf-zone as a passageway to enter the estuary. Even if there was a higher percentage of common species reported (30 out of 66), the monthly average Jaccard index of similarity (IJ = 28%) and the monthly average percent similarity index (IPS = 30%) were low, suggesting that the shallow water functional connectivity between AC and TRE was represented by few species that occur equally in abundance in both environments. Trachinotus marginatus and Mugil liza numerically dominated in the AC and M. liza, Mugil curema, and Atherinella brasiliensis at TRE. Juvenile M liza and M curema added up to >70% of the total individuals sampled in both environments. General linearized models (GLM) revealed that diversity was not influenced by interannual variations, evidencing that juvenile fish assemblage of AC and TRE are resilient through the years. Standardized beach samples are able to reveal long-term fluctuation in shallow estuarine fish communities but without an apparent loss in species composition, richness, and relative total abundance. The only observed interdecadal trend was the reduction in abundance of juvenile M. liza that seemed to parallel the reduction in abundance of the adult fishing stocks in southern Brazil.

Introduction

Globally, estuaries, and coastal areas are environments with high biological productivity, and are considered important nursery areas for juvenile of many coastal fish species, including those of economic interest (Beck et al., 2001; Barletta et al., 2010). Estuaries potentially provide connectivity between marine and freshwater environments (Guimarães et al., 2014; Petry et al., 2016) and several species develop dependency on them. The natural variation of the estuarine environment and anthropogenic effects influence the dynamics of fish populations over time (Barletta et al., 2010; Martins et al., 2015).

The southern coastal plain of Brazil, especially the Rio Grande do Sul state, is composed of several aquatic ecosystems, encompassing habitats of great biological importance (Ramos and Vieira, 2001; Odebrecht et al., 2017). The Tramandaí River estuary (TRE; 29°S; estuarine area c.18.8 km2) is the second larger estuary after the Patos Lagoon estuary (32°S; estuarine area c. 1,000 km2).

Ecological studies of the Patos Lagoon estuary show that increased precipitation during El Niño events change the salinity regime due to increased runoff of continental water. As a consequence there is an increase in the number of freshwater fish species in the estuary (Garcia and Vieira, 2001; Garcia et al., 2004, 2017; Possamai et al., 2018). Freshwater species are much less frequent in the coastal region adjacent to estuaries (Ramos and Vieira, 2001; Monteiro-Neto et al., 2003; Lima and Vieira, 2009; Rodrigues et al., 2014), but the general abundance and diversity of the fish fauna in the marine coastal region are also affected by freshwater runoff coming from the estuary (Martins et al., 2015).

The Tramandal River estuary (TRE) is characterized as a dynamic system, ecologically complex, with high fish diversity, and having significant economic, and recreational importance (Silva, 1982, 1984; Ramos and Vieira, 2001; Guimarães et al., 2014). The system is permanently connected to the sea by an estuarine bar, which represents a transition zone (Silva, 1982) where juvenile marine-estuarine related fishes shelter and feed in shallow estuarine waters (Ramos and Vieira, 2001). Artisanal fishing is of social and economic importance for a large part of the local population, and the TRE attracts tourists during the summer vacation (Silva, 1982; Malabarba and Isaia, 1992; Santos et al., 2018). Other anthropogenic activities in the TRE, such as the petroleum industry, agriculture, forestry, rice cultivation, and sand extraction, have increased considerably in recent decades (Loitzenbauer and Mendes, 2012) and could adversely affect the functional and ecological execution of the system.

Long-term studies are key to determine changes in ecological processes in coastal environments (James et al., 2013; Barceló et al., 2016). In some cases, long-term records are used as the basis for environmental quality or restoration program targets (Tonn et al., 1990). Long-term studies, such as the Brazilian Long Term Ecological Program (PELD) in the Patos Lagoon estuary, provide a unique perspective on the complex dynamics of organisms and ecosystems (Odebrecht et al., 2017). Long-term studies have provided answers concerning spatial and temporal patterns of fish abundance and diversity. They have also explained relationships between environmental variables, anthropic activities and especially natural phenomena (for example, El Niño events) in the Patos Lagoon estuarine region (Garcia and Vieira, 2001; Garcia et al., 2004, 2012; Vieira et al., 2010). These studies enhance the capacity to predict biodiversity responses to global change, specifically responses to both anthropogenic pressures and large-scale climatic events, and can lead to proposals for the conservation and sustainability of local areas (Odebrecht et al., 2017).

Currently, limited information has been compiled about the TRE and the adjacent coast (AC—Ramos and Vieira, 2001; Malabarba et al., 2013; Garcia et al., 2018b; Santos et al., 2018). However, the Laboratory of Ichthyology at the Federal University of Rio Grande (FURG) has a series of unpublished long-term data on the TRE.

Based on a set of intermittent and seasonal data collections, covering a period of 21 years (1995 to 2016), the present study investigated the connectivity between the shallow water of the TRE and the AC. The study specifically examined and compared the structure of shallow water fish associations and local species diversity of TRE and AC throughout the study period of three decades. The seasonal influence of local abiotic variables (salinity, temperature, and water transparency) and connectivity between both environments was scrutinized.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

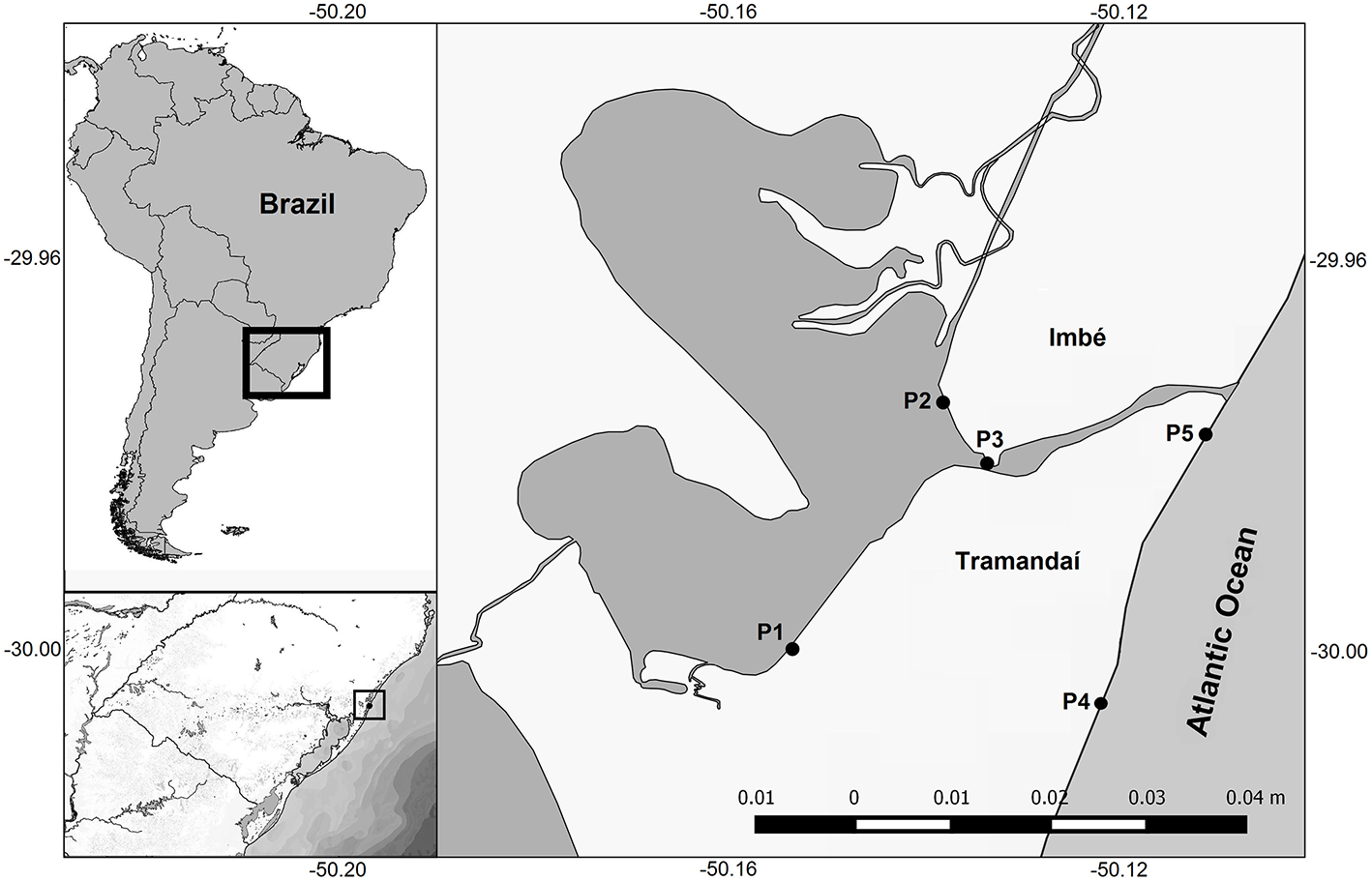

Sampling was conducted over the estuarine system of the Tramandaí-Armazém lagoons (TRE with an area of 18.8 km2) and at the surf-zone of the AC (29° 55′ to 30° 00′ S; 50° 06′21″ to 50° 11′20″ W; Figure 1). The TRE is located on the northern coast of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, and is part of the Tramandaí-Mampituba ecoregion (Abell et al., 2008). The Tramandaí River basin (2,500 km2) is connected to the Atlantic Ocean by a permanent channel (1.5 km long and 100 m wide) (Würdig, 1988) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

South America, Brazil, Rio Grande do Sul State, and study area with the location of collection points in the Tramandaí River estuary (TRE; P1, P2, and P3) and adjacent coast (AC; P4 and P5).

We used a historical intermittent seasonal database (1995–2003) and recent samples (2015–2016) clustered in 15 seasonal sample periods called “visits.” The first 11 intermittent seasonal visits correspond to the summer of 1995, winter of 1996, summer of 1997, spring of 2001, autumn of 2002, winter of 2002, spring of 2002, summer of 2003, autumn of 2003, winter of 2003, and spring of 2003. The four recent visits were during the period autumn 2015 to summer 2016. At each visit at least five sampling points were systematically collected (Figure 1): three points in the estuarine system (P1, P2, and P3) and two in the adjacent marine surf-zone region (P4 and P5). At each visit to the sampling points, environmental variables such as salinity (optical refractometer), temperature (thermometer), and transparency of the water column (Secchi disk) were recorded.

Shallow-water fishes were collected using a “picaré” beach seine (9 m long and 1.5 m high, with a 13 mm mesh in the 3 m wings, and 5 mm mesh in the central part). The minimum sampling effort corresponded to five beach seine hauls at each sampling point per visit. All fishes captured were fixed with 10% formalin solution and processed at the Laboratory of Ichthyology at FURG. All specimens were identified at the lowest possible taxonomic level, counted and weighed (g) using an analytical balance. Changes in nomenclature of the species over the years, including synonyms, have been adjusted. Type specimens were stored in the collection of the Laboratory of Ichthyology at FURG.

Data Analysis

Data collections were compared with each other in terms of space (sampling points along the gradient sea/estuary) and time (seasonal visits). The abundance of each species was determined by means of the catch per unit effort (CPUE), obtained using the ratio N:f, where N is the total number of fishes caught in a specific sampling points and f is the number of beach seine hauls (effort).

For each sample point and visit, the numerical relative abundance (%CPUE) was determined from the ratio of the CPUE for a given species, divided by the sum of the CPUEs of the set of collected species (×100). Frequency of occurrence (%FO) of individual species was calculated using the ratio between the number of occurrences of a given species, divided by the total number of samples (×100) at each point and visit.

Based on Garcia and Vieira (2001), and modified by Artioli et al. (2009), the dominance pattern of each species at each collection point was determined using a combination of %CPUE and %FO. Values of %CPUE and %FO were compared with their respective means (μ%CPUE and μ%FO), and the species classified as follows: abundant and frequent (%CPUE ≥ μ%CPUE, FO% ≥ μFO%); abundant and non-frequent (%CPUE ≥ μ %CPUE, FO% < μ FO%); non-abundant and frequent (%CPUE < μ %CPUE, FO% ≥ μ FO%); or present (%CPUE < μ %CPUE, FO% < μ FO%). The species identified as abundant and frequent were considered as dominant (Artioli et al., 2009; Ceni and Vieira, 2013).

Principal co-ordinates analysis (PCO), from a dissimilarity matrix (coefficient of Bray-Curtis), based on the dominant species was used to evaluate the patterns of spatial distribution of species. PERMANOVA was used to test significant differences between the centroid distances of each group (Anderson and Willis, 2003). Canonic co-ordinate analysis principal (CAP) was used to describe which of the environmental variables analyzed explained the patterns of spatial distribution (in TRE and AC) of fish associations in the best way. The influence of environmental variables (temperature, transparency and salinity) on the association of fishes in the TRE and AC was evaluated by canonical correspondence analysis (CCA). The analyses were performed using software R (https://www.r-project.org).

The faunal similarity analysis, based on the species presence/absence relationship between samples, was calculated using the Jaccard index (JI). The faunal similarity, based on species relative abundance, was obtained by calculating the percent similarity index (PSI) (Krebs, 1989; Magurran, 2004; Ceni and Vieira, 2013).

In order to compare the richness of species between the points sampled (in TRE and AC), the cumulative curves of number of species per sample and the cumulative curves of number of individuals per species collected were constructed (Magurran, 2004; Ceni and Vieira, 2013). To calculate the species richness per zone (in TRE and AC) at each visit, independent of the total number of individuals sampled (N), the rarefaction technique (E[S]) was performed (Sanders, 1968; Hurlbert, 1971; Krebs, 1989) using the PAST software (https://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past/).

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to investigate the variation of fish species richness (gamma distribution) and the probability of the presence of four dominant species (binomial distribution), considering the two environments (TRE and AC) as a single data set, in response to a set of predictor variables (salinity, temperature, transparency of water, season, and year). Predictive variables were tested for co-linearity using the Spearman coefficient prior to model formulation (Beger and Possingham, 2008). In the models, no highly correlated variables were included (R2 > 0.8). To choose the best model, we followed the “backward stepwise” procedure by selecting the template that had the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) value (Anderson and Burnham, 2002). The percentage of total deviance explained, and the relative contribution of each predictor were independently verified for each model (Vasconcelos et al., 2013, 2015).

Results

A total of 97,282 individuals were captured, belonging to 11 orders, 27 families, and 66 species (Appendix 1). The dominant group of species per visit for each environment was identified (Tables 1, 2). Among the 41 species that occurred in the AC, only 10 were classified as dominant in at least one visit (Table 1). Trachinotus marginatus Cuvier 1832 and Mugil liza Valenciennes 1836 occurred as dominant in at least 50% of the visits in the AC. Among the 55 species that occurred in the TRE, only eight were classified as dominant in at least one visit (Table 2). Three species occurred as dominant in at least 50% of visits in the TRE: M. liza, Mugil curema Valenciennes 1836 and Atherinella brasiliensis Quoy and Gaimard, 1825.

Table 1

| AC | Su-95 | Wi-96 | Su-97 | Sp-01 | Au-02 | Wi-02 | Sp-02 | Su-03 | Au-03 | Wi-03 | Sp-03 | Au-15 | Wi-15 | Sp-15 | Su-16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | |||||||||||||||

| Mugil liza | 0.8 | 421.9 | 2.1 | 12.7 | 28.0 | 3.9 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 7.6 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| Mugil curema | 307.0 | 0.4 | 705.8 | 0.2 | 4.5 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 31.2 | 0.1 | 1.2 | |||||

| Trachinotus marginatus | 3.6 | <0.1 | 23.6 | 1.3 | 35.7 | 3.7 | 83.2 | 62.8 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 1.1 | 127.2 | 13.7 | 28.3 | |

| Odontesthes argentinensis | 0.6 | 2.3 | 21.2 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 6.0 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | |||

| Micropogonias furnieri | 0.4 | 0.4 | 95.9 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| Stellifer rastrifer | 34.4 | ||||||||||||||

| Mugil sp.1 | 0.1 | 5.7 | 8.8 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | |||||||

| Umbrina canosai | 6.9 | 0.1 | 1.1 | ||||||||||||

| Platanichthys platana | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 6.8 | |||||||||||

| Trachinotus carolinus | 3.6 | <0.1 | 5.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 6.6 | |||||||||

| Brevoortia pectinata | 7.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | <0.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 18.1 | 0.8 | ||||||

| Atherinella brasiliensis | 8.9 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 0.6 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Menticirrhus littoralis | 0.1 | <0.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.1 | <0.1 | 0.3 | 3.0 | 0.2 | ||

| Pomatomus saltatrix | 4.8 | <0.1 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||

| Caranx latus | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||

| Oncopterus darwinii | 0.6 | <0.1 | 0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| Samples | 20 | 27 | 29 | 10 | 23 | 29 | 36 | 14 | 10 | 30 | 29 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Number of species | 16 | 11 | 22 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 15 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 17 | 8 | 4 | 9 |

| CPUE total | 334.2 | 426.7 | 866.2 | 71.9 | 81.0 | 12.3 | 100.4 | 71.9 | 12.8 | 9.8 | 14.7 | 199.4 | 16.3 | 1.8 | 38.6 |

| Temperature (°C) | 27 | 15 | 25 | 24 | 18 | 15 | 23 | 22 | 19 | 17 | 24 | 25 | 17 | 21 | 28 |

| Salinity | 30 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 34 | 31 | 34 | 32 | 36 | 33 | 34 | 37 | 33 | 28 | 23 |

| Transparency (cm) | 9 | 34 | 8 | 42 | 26 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 5 | 15 | 29 | 30 | 20 | 17 | 40 |

List of species caught per season per year in the marine adjacent coastal area (AC) and number of samples, number of species, total catch per unit effort (CPUE), mean temperature (°C), mean salinity and mean transparency (cm).

Based on the species frequency of occurrence (%FO) and relative abundance (CPUE%) the species were classified as: abundant and frequent (black shading), frequent and not abundant (light gray shading), abundant and infrequent (dark gray shading), infrequent and not abundant (no shading) or absent (–).

Table 2

| TRE | Su-95 | Wi-96 | Su-97 | Sp-01 | Au-02 | Wi-02 | Sp-02 | Su-03 | Au-03 | Wi-03 | Sp-03 | Au-15 | Wi-15 | Sp-15 | Su-16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | |||||||||||||||

| Mugil liza | 2.3 | 83.4 | 43.2 | 78.7 | 25.8 | 174.8 | 90.3 | 5.0 | 30.2 | 27.1 | 5.8 | 19.0 | 22.1 | 0.7 | 5.4 |

| Mugil curema | 3.8 | 1.9 | 137.9 | 11.4 | 1.7 | 8.3 | 35.7 | 0.7 | 8.7 | 378.7 | 0.1 | 21.4 | |||

| Atherinella brasiliensis | 6.5 | 7.7 | 5.8 | 12.4 | 10.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 4.6 | 42.5 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 11.5 | |

| Jenynsia multidentata | 9.3 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.1 | |||||

| Ctenogobius schufeldti | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 | |||

| Odontesthes argentinensis | 1.9 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Eucinostomus melanopterus | 2.3 | <0.1 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 0.5 | ||||||

| Lycengraulis grossidens | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 5.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.9 | ||||||

| Eucinostomus argenteus | 4.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | ||||||||||

| Eucinostomus lefroyi | 29.6 | 16.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | <0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |||||||

| Brevoortia pectinata | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 | <0.1 | 3.6 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 8.7 | 58.9 | |||||

| Micropogonias furnieri | 0.1 | 6.9 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 3.2 | |||||||

| Mugil sp.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 21.3 | 0.1 | |||||||||

| Astyanax lacustris | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | <0.1 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| Astyanax eigenmanniorum | 0.1 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 4.3 | ||||||||||

| Platanichthys platana | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 14.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||||||

| Umbrina canosai | <0.1 | 0.7 | |||||||||||||

| Caranx latus | 0.2 | 0.1 | <0.1 | 0.7 | |||||||||||

| Samples | 20 | 19 | 18 | 14 | 46 | 59 | 61 | 20 | 34 | 25 | 29 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Number of species | 14 | 7 | 18 | 17 | 22 | 20 | 29 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 17 | 20 | 7 | 12 | 13 |

| CPUE total | 60.3 | 93.7 | 232.2 | 93.6 | 66.5 | 197.5 | 107.5 | 47.1 | 32.9 | 32.6 | 39.7 | 478.4 | 24.6 | 3.5 | 108.4 |

| Temperature (°C) | 32 | 15 | 27 | 24 | 21 | 16 | 24 | 22 | 19 | 17 | 25 | 24 | 15 | 23 | 32 |

| Salinity | 1 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 14 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Transparency (cm) | 41 | 80 | 39 | 13 | 29 | 17 | 28 | 35 | 10 | 22 | 14 | 47 | 59 | 62 | 62 |

List of species caught per season per year in Tramandaí River estuary (TRE) and number of samples, number of species, total catch per unit effort (CPUE), mean temperature (°C), mean salinity, and mean transparency (cm).

Based on the species frequency of occurrence (%FO) and relative abundance (CPUE%), the species were classified as: abundant and frequent (black shading), frequent and not abundant (light gray shading), abundant and infrequent (dark gray shading), infrequent and not abundant (no shading) or absent (–).

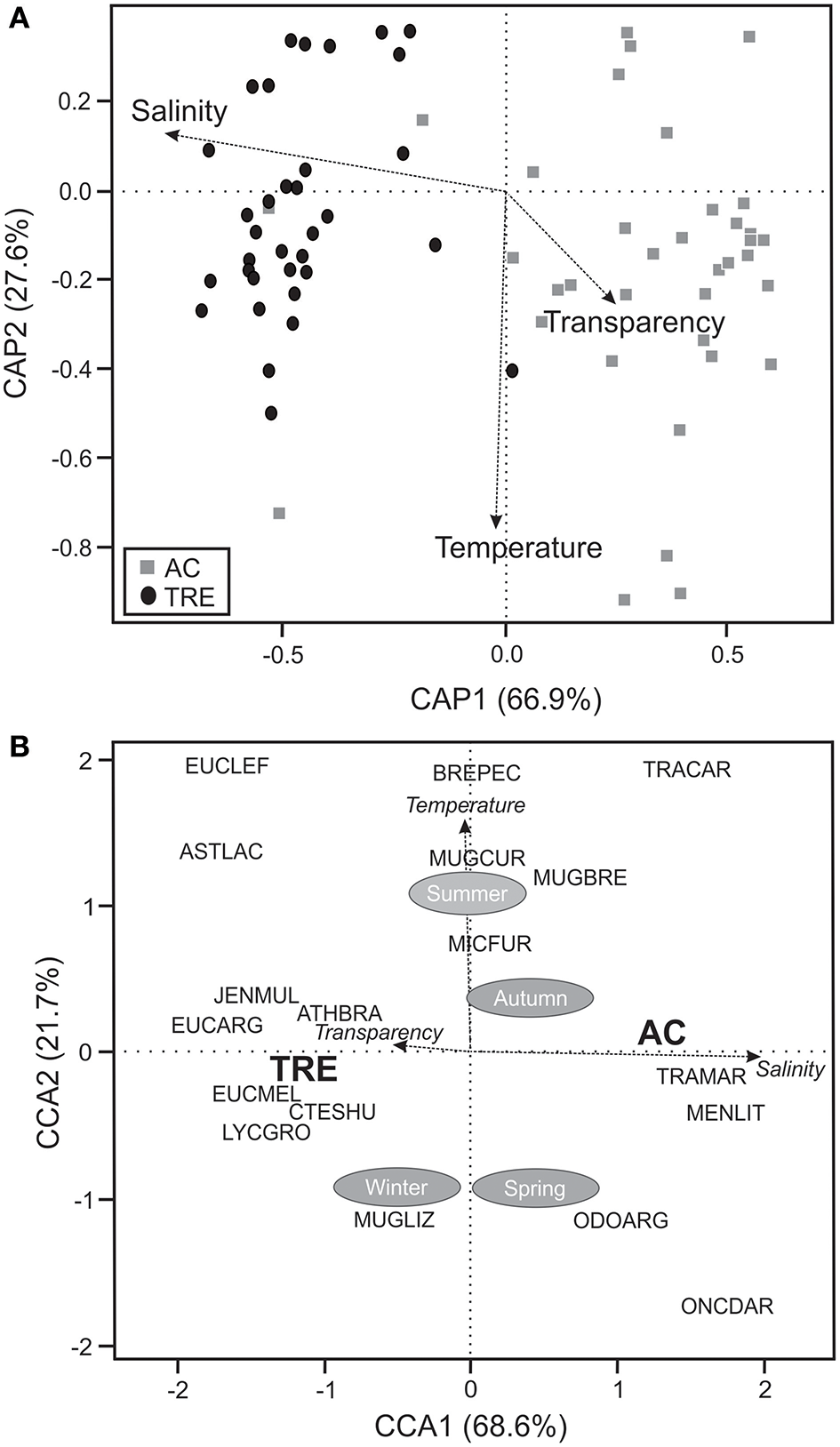

Based on the CCA and CAP it was possible to discriminate two fish associations (Figure 2A): one was related to the TRE sampling points and another to the AC. Using PERMANOVA significant differences (P < 0.05) in the spatial variation of those associations were detected. Salinity was the variable that explained most the spatial distribution among species (Figure 2A). The CCA confirmed that salinity was the variable that best explained the variability in the structure of the fish fauna of TRE and AC, and that temperature explained the temporal-seasonal distribution of the species (Figure 2B).

Figure 2

(A) Canonic coordinate analysis principal (CAP) based on dominant species and (B) canonical correlation analysis (CCA) relating the dominant species to the environmental variables and seasons. TRE, Tramandaí River estuary; AC, marine adjacent coastal area.

In AC, 297 samples were taken capturing 41 species. In the same period at TRE, 405 samples were taken capturing 55 species (Tables 1, 2). Between AC and TRE it was possible to observe a significant difference (P < 0.05) in the average sampling effort (f = 19.8 AC; f = 27.0 TRE) and in the average number of species caught per visit (S = 11.3 AC; S = 15.1 TRE). A greater number of individuals was collected in the AC (n = 54.295) than in the TRE (n = 42.987), although there was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the mean number of individuals collected per sample (CPUE) between the areas (Table 3).

Table 3

| Variable | t-test | Mean | S.D | MIN | MAX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | AC | TE | AC | TE | AC | TE | AC | TER | |

| Samples | 0.04 | 19.8 | 27 | 9.61 | 16 | 10 | 14 | 36 | 61 |

| Number of species | 0.02 | 11.33 | 15.13 | 4.67 | 6.12 | 4 | 7 | 22 | 29 |

| Total CPUE | 0.53 | 150.53 | 107.88 | 235.03 | 120.31 | 1.8 | 3.47 | 866.21 | 478.4 |

A t-test comparison (mean, minimum and maximum values, and S.D.) of the variables (number of samples, number of species, and catch per unit effort, CPUE) in the Tramandaí River estuary (TRE) and marine adjacent coastal area (AC).

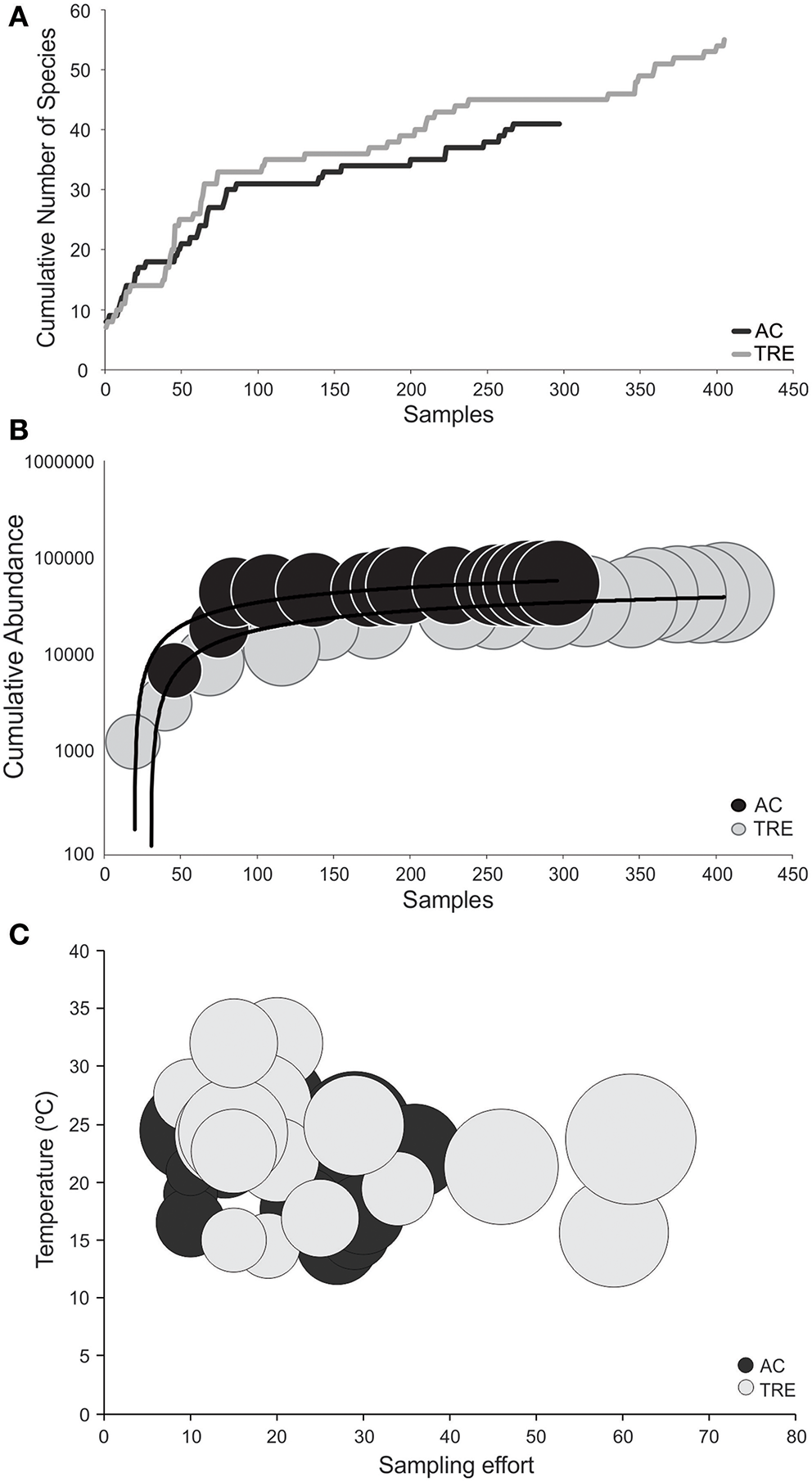

It is possible to observe (Figure 3A) that the rate of cumulative number of species per sample is greater in the TRE than in the AC. The cumulative influence of sampling effort (x-axis) and total number of individuals collected (y-axis) on the final number of species (size of the circles) is observed at Figure 3B. The largest number of samples in the TRE (f = 405) is the factor that best explains the greater species richness observed in the TRE as compared to the AC (f = 297) (Figure 3B). It is important also to emphasize that the lack of parity in number of sample (different efforts between TRE and AC) interferes with the comparison of observed species richness between the two habitats.

Figure 3

(A) Cumulative curve of number of species per sample; (B) cumulative curve of number of individuals collected (y-axis) per samples (x-axis) and the relationship with number of species (circle size is proportional to species richness); and (C) the relationship between the variables predicted by the gamma model (effort and temperature) and species richness (circle size is proportional to species richness), separated by environment. TRE, Tramandaí River estuary; AC, marine adjacent coastal area.

The use of GLM technique on the entire dataset (Table 4) shows that species richness for both the TRE or AC vary in the same way, regardless of the environment and are best explained by three variables. Temperature (Figure 3C) explained 14.4% of species richness and sampling effort 12.2%, which is associated with the number of individuals collected (9.5%; Figure 3B). This observation suggests that rarefaction techniques have to be applied in order to compare species richness independently of effort and number of individuals collected. In a simulation, where all the samples from both the TRE and AC were pooled and resampled at c.300 individuals, the expected richness of the TRE [E(S) = 18.2] was significantly greater (P < 0.05) than that of the AC [E(S) = 14.4].

Table 4

| Predictor | P | Res. dev. | Deviance | % Expl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richeness | ||||

| Gamma model | ||||

| NULL | 22.478 | |||

| Samples | 4.67e-05*** | 19.739 | 2.7389 | 12.18 |

| Abundance | 0.0003171*** | 17.596 | 2.1428 | 9.53 |

| Temperature | 9.326e-06*** | 14.35 | 3.2464 | 14.44 |

| Total explained | 36.2 |

Variability and adjustment for the logistic and gamma general linear models fitted to the fish richness values of the Tramandaí River estuary (TRE) and marine adjacent coastal area (AC).

Significance values (P) for each factor, residual deviance (Res. Dev.), deviance, and percentage of the total deviance explained by each factor (%Expl.) are presented. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Thirty out of 66 species collected were common between the TRE and AC, but the average similarity between the TRE and AC among visits was low (JI = 28%). The average similarity based on species relative abundance among visits was also low (PSI = 30%). The combination of low monthly average JI and low monthly average PSI suggests that the same species occurring equally in both environments dominate in abundance (Tables 2, 3).

Both the TRE and AC were dominated by two species of mullets (M. liza and M. curema). In both environments, these two add up to >70% of individuals caught. The diversity differences between TRE and AC are due to the remaining additional species.

The GLM model (Gamma) adjusted for the log10 (CPUE+1) of both M. liza and M. curema, shows similar patterns (Table 5). For M. liza, the variables year (17.8%) and environment (12.8%) were the most significant predictors. For M. curema, seasonality (22.5%) was the variable with the best explanatory power (Table 5). Although both species were conspicuous in the area, M. liza showed a tendency to be more abundant within the TRE during the colder periods and M. curema more abundant in warmer months in the AC. The abundance pattern of M. liza presented a year-to-year downward trend during 21 years of observation, and this decrease in abundance was more obvious in the AC than in the TRE.

Table 5

| Predictor | P | Res. dev. | Deviance | % Expl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abundance (Gamma model) | ||||

| Mugil liza | ||||

| NULL | 36.082 | |||

| Environment | 0.00004654*** | 31.465 | 4.6166 | 12.79 |

| Year | 0.001601** | 25.019 | 6.4461 | 17.87 |

| Total explained | 30.66 | |||

| Mugil curema | ||||

| NULL | 22.868 | |||

| Environment | 0.926304# | 22.864 | 0.0034 | 0.01 |

| Season | 0.005056** | 17.713 | 5.1519 | 22.53 |

| Transparency | 0.029575* | 15.809 | 1.9032 | 8.32 |

| Total explained | 30.87 |

Variability and adjustment for the logistic and gamma general linear models fitted to the abundance values (Log10 (CPUE+1) for Mugil liza and Mugil curema in the Tramandaí River estuary (TRE) and marine adjacent coastal area (AC).

Values of significance (P) for each factor, residual deviance (Res. Dev.), deviance and percentage of the total deviance explained by each factor (%Expl.) are presented.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001;

P > 0.1.

Discussion

Understanding the level of connectivity between estuarine and marine environments is essential for the appropriate management of taxa associated with coastal zones. Connectivity, from a fish ecological perspective, can be described as a mechanism that facilitates the movement of fish between distinct spatio-temporal units (Dale and Sheaves, 2015) and contributes to the composition and richness of species of coastal zones environments (Petry et al., 2016).

The TRE (S = 55) has a greater number of juvenile species than the AC (S = 41). Many studies suggest that collections should be standardized to better compare community structures and monitor trends in fish abundance (Fischer and Paukert, 2009; Mourão et al., 2014). The larger species richness in the TRE compared to the AC cannot only be attributed to differences in collection effort because even after standardization (rarefaction techniques) the expected richness of the TRE [E(S) = 18.2] was significantly greater (P < 0.05) than that of the AC [E(S) = 14.4]. It is possible that other factors may contribute to this difference.

The estuarine regions in southern Brazil present a greater variety of habitats compared to adjacent coastal zones (Ramos and Vieira, 2001; Odebrecht et al., 2017). With regard to the TRE and AC complex, Garcia et al. (2018b) shows that fish assemblages in continental systems are sustained by a greater number of autotrophic sources than in the adjacent marine systems. Habitat heterogeneity should contribute to the greater richness of species in TRE, and also to other environments, especially coastal lagoons and other estuaries (Petry et al., 2016). These findings could be explained by the greater number of food web components (autotrophic sources, fishes trophic guilds and prey) associated with pelagic and benthic food chains within the estuary in comparison to the adjacent systems studied (Garcia et al., 2018b).

The adjacent coast (surf-zone) represent transitional areas that function as estuarine-dependent species migratory routes, indicating the connectivity between coastal zones and estuaries (Monteiro-Neto et al., 2003; Lima and Vieira, 2009; Mourão et al., 2014; Silva et al., 2016). Even if there is a good percentage of common juvenile species (30 out of 66) between the shallow water of both environments, the monthly faunal similarity based on species relative abundance (PSI = 30%), was low and similar to the average similarity based on the species presence/absence (JI = 28%). This revealed that only a few species were numerically dominant in the shallow-water fish associations. Thus, the shallow-water fish assemblages of TRE and AC have a few dominant species in common, and these common species are abundant in both environments and occur through the sampling period. These observations suggest that shallow-water estuarine and surf-zone connectivity between TRE and AC is effective for only a few species which are able to take advantage of both environments.

The surf-zone and shallow-water of estuaries of southern Brazil are mostly dominated by juveniles of Mugilidae (<50 mm total length; Vieira et al., 2010; Mont'Alverne et al., 2012). In the TRE and AC, juveniles of two species of Mugil represented c.76% of the total catch in both environments sampled. Juvenile M. liza showed higher abundance in the estuarine environment (54%) and M. curema in the marine environment (50%). Although salinity preference seems to be the main factor that segregate the juveniles of these two species, temperature is the variable that best separates them (Vieira, 1991; Garcia et al., 2018b; Mai et al., 2018). Adults of both species spawn in the marine environment and juveniles use the coastal region and estuaries as nurseries (Vieira, 1991; Mai et al., 2018). Juvenile M. curema abundance is associated with hot seasons, as a consequence of spawning during warmer conditions (Mai et al., 2018). It is important to note that adult M. curema are scarce in coastal environments located south of TRE (Patos Lagoon, for example). Mugil liza, however, have a high abundance of juveniles during cooler periods (Vieira, 1991; Ramos and Vieira, 2001; Lemos et al., 2014; Mai et al., 2018). They spawn during the winter and adults occur in higher numbers south of TRE (Vieira, 1991). It is possible that, in addition to the reproductive period, ecological processes related to feeding and to habitat use influence spatial patterns of juveniles of these two species (Garcia et al., 2018a).

Abiotic interactions affect ecological processes (migration, dispersion, and invasion) and also contribute to the composition and species richness of estuaries and marine areas (Desmond et al., 2002; Andrade-Tubino et al., 2008; Franco et al., 2008; Cheung et al., 2012). In south Brazilian coastal areas the seasonal variations of temperature and spatial oscillation of salinity, among other factors, provide intra- and inter-annual variability that is associated with the occurrence of larger scale climatic phenomena (Garcia et al., 2004, 2012; Moraes et al., 2012; Martins et al., 2015). Temperature plays an important role in seasonal migrations of some species, having a direct effect on the metabolic, reproductive, and abundance processes of the fish fauna (Mont'Alverne et al., 2012; Moraes et al., 2012; Cattani et al., 2016). Thus, recruitment of young fishes determines the composition and the seasonal variations in abundance of shallow-water species (Mont'Alverne et al., 2012; Moraes et al., 2012). Although temperature determines seasonal variation and enhances fish species diversity at both the TRE and AC, salinity was responsible for spatial distribution between these two environments.

Precipitation is an important factor in establishing spatial variation in salinity and the taxonomic structure of juvenile fish assemblages (Vinagre et al., 2009; Jenkins et al., 2010; Gillanders Bronwyn et al., 2011). The occurrence of the El Niño increases rainfall, which raises freshwater flow into the estuaries. This favors the presence of freshwater species, which increases species richness in the estuary (Garcia and Vieira, 2001; Garcia et al., 2004, 2012; Vieira et al., 2010).

During the 21-year period covered in this study, two different El Niño events were observed, 1997–98 and 2015–16, with the El Niño of 2015–16 being considered one of the most severe since 1950. The presence of freshwater species in TRE samples during this period raised species richness, masking any reduction in other estuarine and marine-related species. However, the effect of precipitation during El Niño events was not observed in AC.

A broad variety of sampling strategies and fishing gears has been developed to collect and record the presence and abundance of different fish species occurring in estuarine and coastal marine habitats. The beach seine, due to its robustness, rusticity, and ease of use and maintenance, is an appropriate gear for regular work in environments without catchers and entanglement (Vieira, 2006; Ceni and Vieira, 2013; Lombardi et al., 2014). The drawback of a beach seine, however, is that the catches provide low precision in estimates of abundance (Lombardi et al., 2014). However, the beach seine is a good sampling device for regular low-cost projects (Vieira, 2006; Ceni and Vieira, 2013) and we strongly recommend this gear to be used in the future so comparisons can be made with past data that have been gathered using this seine. This is illustrated in the long term studies of the Patos Lagoon estuary and adjacent area where this seine have been employed monthly since 1996 (Vieira et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2017).

The logic behind a long-term study at TRE and AC, which analyses data from a 21-year period for two distinct but interconnected environments, is that the estuary, with a restricted topography, is subjected to more anthropic effects and greater chances of being impacted. Over the 21-year period covered by this study, local anthropic activities (fishing, tourism, and population growth), together with extreme climatic events, would be anticipated to influence the diversity and abundance of the TRE and AC fish species.

It is known that estuarine fish assemblages are highly resilient despite exposure to vast hydrodynamic variations and stress (Ching, 2015). Standardized beach samples are able to reveal long-term fluctuation in shallow estuarine fish communities but without an apparent loss in species composition, richness, and relative total abundance.

The challenge of long-term ecological studies is to understand resilience of the communities (Garcia and Vieira, 2001; Garcia et al., 2004, 2012; Vieira et al., 2010; Barceló et al., 2016). The TRE seams to be resilient especially to multiple and compounding stressors. The use of robust spatial-temporal data analysis techniques, such as GLM, was able to improve data analysis and help to show spatial and seasonal trends in the TRE and AC.

Regarding species richness, the inter-annual variations (year factor) did not appear to be significant in the GLM analysis. Therefore, this technique did not detect a reduction in species richness over the period covered by this study. The only species, during the 21-year study, in which a reduction in abundance was detected was M. liza, especially at surf-zone sampling points. Reported reduction of M. liza fishing stocks (Lemos et al., 2016; Sant'Ana et al., 2017) and juvenile abundance (Rodrigues et al., 2014; Martins et al., 2015) suggested that both adults and juveniles have shown a decrease in abundance in southern Brazil. This observation parallels the reduction in juvenile abundance of M. liza in AC, suggesting that this phenomenon should be better investigated in the future since mullets are among the most important fisheries resource of the TRE and adjacent coastal zones.

Statements

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Brazilian Ministry of Environment (MMA) and all data collections and fish handling were endorsed by the Permanent License for Collection of Zoological Material (Number: 10125-2) granted to JV since September 2007. The fish collections analyzed in this paper occurred before the ethics committee of FURG (Comissão de Ética em Uso Animal—CEUA) was established. Nowadays the Laboratory of Ichthyology is under the CEUA license number 07/2017.

Author contributions

This paper is part of VR-R máster studies at Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia de Ambientes Aquáticos Continentais at FURG. VR-R and MdS collected data between 2015 and 2016. LR collected data from 2001 to 2003. VR-R, FR, and MdS help with data collection and analysis. JV participate in all data collection and analyses. All the authors reed part or all of this manuscript and agree with the publication of it.

Acknowledgments

VR-R was a master's student at FURG with a scholarship from OAS-CAPES (Organization of AmericanStates—Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel). JV (Proc. 482236/2011-6) received a CNPq grant. This work is a contribution of FAPERGS Proc. 2327-2551/14-6.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Abell R. Thieme M. Revenga C. Bryer M. Kottelat M. Bogutskaya N. et al . (2008). Freshwater ecoregions of the world: a new map of biogeographic units for freshwater biodiversity conservation. Bioscience. 58, 403–414. 10.1641/B580507

2

Anderson D. R. Burnham K. P. (2002). Avoiding pitfalls when using information theoretic methods. J. Wildlife. Manage.66, 912–918. 10.2307/3803155

3

Anderson M. J. Willis T. J. (2003). Canonical analysis of principal coordinates: a useful method of constrained ordination for ecology. Ecology. 84, 511–525. 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[0511:CAOPCA]2.0.CO;2

4

Andrade-Tubino M. Ribeiro A. L. Vianna M. (2008). Organização espaço-temporal das ictiocenoses demersais nos ecossistemas estuarinos brasileiros: uma síntese. Oecol. Bras. 12, 640–661. 10.4257/oeco.2008.1204.05

5

Artioli L. G. Vieira J. P. Garcia A. M. Bemvenuti M. A. (2009). Distribuição, dominância e estrutura de tamanhos da assembleia de peixes da lagoa Mangueira, sul do Brasil. Iheringia. Ser. Zool.99, 409–418. 10.1590/S0073-47212009000400011

6

Barceló C. Ciannelli L. Olsen E. M. Johannessen T. Knutsen H. (2016). Eight decades of sampling reveal a contemporary novel fish assemblage in coastal nursery habitats. Glob. Change. Biol.22, 1155–1167. 10.1111/gcb.13047

7

Barletta M. Jaureguizar A. J. Baigun C. Fontoura N. F. Agostinho A. A. Almeida-Val V. M. et al . (2010). Fish and aquatic habitat conservation in South America: a continental overview with emphasis on neotropical systems. J. Fish. Biol. 76, 2118–2176. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02684.x

8

Beck M. W. Heck K. L. Able K. W. Childers D. L. Eggleston D. B. Gillanders B. et al . (2001). The identification, conservation, and management of estuarine and marine nurseries for fish and invertebrates: a better understanding of the habitats that serve as nurseries for marine species and the factors that create site-specific variability in nursery quality will improve conservation and management of these areas. BioScience. 51, 633–641. 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0633:TICAMO]2.0.CO;2

9

Beger M. Possingham H. P. (2008). Environmental factors that influence the distribution of coral reef fishes: modeling occurrence data for broad-scale conservation and management. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.361, 1–13. 10.3354/meps07481

10

Cattani A. Jorge F. Ribeiro G. Wedekin L. Lopes P. C. Rupil G. M. et al . (2016). Fish assemblages in a coastal bay adjacent to a network of marine protected areas in southern Brazil. Braz. J. Oceanogr.64, 295–308. 10.1590/S1679-87592016121306403

11

Ceni G. Vieira J. P. (2013). Looking through a dirty glass: how different can the characterization of a fish fauna be when distinct nets are used for sampling?Zoologia30, 499–505. 10.1590/S1984-46702013000500005

12

Cheung W. W. L. Meeuwig J. J. Feng M. Harvey E. Lam V. W. Y. Langlois T. et al . (2012). Climate-change induced tropicalisation of marine communities in Western Australia. Mar. Freshwater. Res. 63, 415–427. 10.1071/MF11205

13

Ching V. M. (2015). Contrasting tropical estuarine ecosystem functioning and stability: a comparative study. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. S.155, 89–103. 10.1016/j.ecss.2014.12.044

14

Dale P. Sheaves M. (2015). Estuarine connectivity in Encyclopedia of Estuaries, ed KennishM. (Dordrecht: Springer), 258–260. 10.1007/978-94-017-8801-4_281

15

Desmond J. S. Deutschman D. H. Zedler J. B. (2002). Spatial and temporal variation in estuarine fish and invertebrate assemblages: analysis of an 11-year data set. Estuaries25, 552–569. 10.1007/BF02804890

16

Fischer J. R. Paukert C. P. (2009). Effects of sampling effort, assemblage similarity, and habitat heterogeneity on estimates of species richness and relative abundance of stream fishes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.66, 277–290. 10.1139/F08-209

17

Franco A. Elliott M. Franzoi P. Torricelli P. (2008). Life strategies of fishes in European estuaries: the functional guild approach. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.354, 219–228. 10.3354/meps07203

18

Garcia A. F. S. Garcia A. M. Vollrath S. R. Schneck F. Silva C. F. M. Marchetti Í. J. et al . (2018a). Spatial diet overlap and food resource in two congeneric mullet species revealed by stable isotopes and stomach content analyses. Community. Ecol.19, 116–124. 10.1556/168.2018.19.2.3

19

Garcia A. F. S. Santos M. L. Garcia A. M. Vieira J. P. (2018b). Changes in food web structure of fish assemblages along a river-to-ocean transect of a coastal subtropical system. Mar. Freshwater. Res.70:402–16. 10.1071/MF18212

20

Garcia A. M. Vieira J. P. (2001). O aumento da diversidade de peixes no estuário da Lagoa dos Patos durante o episódio El Niño 1997-1998. Atlantica.23, 133–152.

21

Garcia A. M. Vieira J. P. Winemiller K. O. Grimm A. M. (2004). Comparison of 1982–1983 and 1997–1998 El Niño effects on the shallow-water fish assemblage of the Patos Lagoon estuary (Brazil). Estuar. Coast.27, 905–914. 10.1007/BF02803417

22

Garcia A. M. Vieira J. P. Winemiller K. O. Moraes L. E. Paes E. T. (2012). Factoring scales of spatial and temporal variation in fish abundance in a subtropical estuary. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.461, 121–135. 10.3354/meps09798

23

Garcia A. M. Winemiller K. O. Hoeinghaus D. J. Claudino M. C. Bastos R. Correa F. et al . (2017). Hydrologic pulsing promotes spatial connectivity and food web subsidies in a subtropical coastal ecosystem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.567, 17–28. 10.3354/meps12060

24

Gillanders Bronwyn M. Elsdon Travis S. Halliday Ian A. Jenkins Gregory P. Robins Julie B. Valesini Fiona J. (2011). Potential effects of climate change on Australian estuaries and fish utilising estuaries: a review. Mar. Freshwater. Res. 62, 1115–1131. 10.1071/MF11047

25

Guimarães T. F. Hartz S. M. Becker F. G. (2014). Lake connectivity and fish species richness in southern Brazilian coastal lakes. Hydrobiologia. 40, 207–217. 10.1007/s10750-014-1954-x

26

Hurlbert S. H. (1971). The nonconcept of species diversity: a Critique and alternative parameters. Ecology52, 577–586. 10.2307/1934145

27

James N. C. Niekerk L. V. Whitfield A. K. Potts W. M. Götz A. Paterson A. W. (2013). Effects of climate change on South African estuaries and associated fish species. Climate Res.57, 233–248. 10.3354/cr01178

28

Jenkins G. P. Conron S. D. Morison A. K. (2010). Highly variable recruitment in an estuarine fish is determined by salinity stratification and freshwater flow: implications of a changing climate. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.417, 249–261. 10.3354/meps08806

29

Krebs C. J. (1989). Ecological Methodology. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers.

30

Lemos V. M. Troca D. F. Castello J. P. Vieira J. P. (2016). Tracking the southern Brazilian schools of Mugil liza during reproductive migration using VMS of purse seiners. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res.44, 238–246. 10.3856/vol44-issue2-fulltext-5

31

Lemos V. M. Varela A. S. Schwingel P. R. Muelbert J. H. Vieira J. P. (2014). Migration and reproductive biology of Mugil liza (Teleostei: Mugilidae) in south Brazil. J. Fish. Biol.85, 671–687. 10.1111/jfb.12452

32

Lima M. S. Vieira J. P. (2009). Variação espaço-temporal da ictiofauna da zona de arrebentação da Praia do Cassino, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Zoologia26, 499–510. 10.1590/S1984-46702009000300014

33

Loitzenbauer E. Mendes C. A. B. (2012). Salinity dynamics as a tool for water resources management in coastal zones: an application in the Tramandaí River basin, southern Brazil. Ocean. Coast. Manage.55, 52–62. 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.10.011

34

Lombardi P. M. Rodrigues F. L. Vieira J. P. (2014). Longer is not always better: the influence of beach seine net haul distance on fish catchability. Zoologia31, 35–41. 10.1590/S1984-46702014000100005

35

Magurran A. E. (2004). Measuring Biological Diversity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

36

Mai A. C. G. Santos M. L. Lemos V. M. Vieira J. P. (2018). Discrimination of habitat use between two sympatric species of mullets, Mugil curema and Mugil liza (Mugiliformes: Mugilidae) in the rio Tramandaí Estuary, determined by otolith chemistry. Neotrop. Ichthyol.16:e170045. 10.1590/1982-0224-20170045

37

Malabarba L. R. Carvalho-Neto P. Bertaco V. A. Carvalho T. P. Santos J. F. Artioli L. G. S. (2013). Guia de Identificação dos Peixes da Bacia do Rio Tramandaí. Porto Alegre: Via Sapiens.

38

Malabarba L. R. Isaia E. A. (1992). The fresh water fish fauna of the rio Tramandaí drainage, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, with a discussion of its historical origin. Comunicações do Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia da PUCRS, Zoologia.5, 197–223.

39

Martins A. C. Kinas P. G. Marangoni J. C. Moraes L. E. Vieira J. P. (2015). Medium-and long-term temporal trends in the fish assemblage inhabiting a surf zone, analyzed by Bayesian generalized additive models. Aquat. Ecol.49, 57–69. 10.1007/s10452-015-9504-9

40

Mont'Alverne R. Moraes L. E. Rodrigues F. L. Vieira J. P. (2012). Do mud deposition events on sandy beaches affect surf zone ichthyofauna? A southern Brazilian case study. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. S102, 116–125. 10.1016/j.ecss.2012.03.017

41

Monteiro-Neto C. Cunha L. P. Musick J. A. (2003). Community structure of surf zone fishes at Cassino Beach, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J. Coastal. Res. 35, 492–501.

42

Moraes L. E. Paes E. Garcia A. M. Möller O. Vieira J. P. (2012). Delayed response of fish abundance to environmental changes: a novel multivariate time-lag approach. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.456, 159–168. 10.3354/meps09731

43

Mourão K. R. Ferreira V. Lucena-Frédou F. (2014). Composition of functional ecological guilds of the fish fauna of the internal sector of the Amazon Estuary, Pará, Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc.86, 1783–1800. 10.1590/0001-3765201420130503

44

Odebrecht C. Secchi E. R. Abreu P. C. Muelbert J. H. Uiblein F. (2017). Biota of the Patos Lagoon estuary and adjacent marine coast: long-term changes induced by natural and human-related factors. Mar. Biol. Res.13, 3–8. 10.1080/17451000.2016.1258714

45

Petry A. C. Guimarães T. F. Vasconcellos F. M. Hartz S. M. Becker F. G. Rosa R. S. et al . (2016). Fish composition and species richness in eastern South American coastal lagoons: additional support for the freshwater ecoregions of the world. J. Fish. Biol.89, 280–314. 10.1111/jfb.13011

46

Possamai B. Vieira J. P. Grimm A. M. Garcia A. M. (2018). Temporal variability (1997-2015) of trophic fish guilds and its relationships with El Niño events in a subtropical estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. S.202, 145–154. 10.1016/j.ecss.2017.12.019

47

Ramos L. A. Vieira J. P. (2001). Composição específica e abundância de peixes de zonas rasas dos cinco estuários do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Bol. Inst. Pesca.27, 109–121.

48

Rodrigues F. L. Cabral H. N. Vieira J. P. (2014). Assessing surf-zone fish assemblage variability in southern Brazil. Mar. Freshwater. Res.66, 106–119. 10.1071/MF13210

49

Sanders H. L. (1968). Marine benthic diversity: a comparative study. Am. Nat.102, 243–282. 10.1086/282541

50

Sant'Ana R. Kinas P.G. Miranda L.V. Schwingel P.R. Castello J.P. Vieira J.P. (2017). Bayesian state-space models with multiple CPUE data: the case of a mullet fishery. Scientia Marina, 81, 361–370. 10.3989/scimar.04461.11A

51

Santos M. L. Lemos V. M. Vieira J. P. (2018). No mullet, no gain: cooperation between dolphins and cast net fishermen in southern Brazil. Zoologia35, 1–13. 10.3897/zoologia.35.e24446

52

Silva C. (1982). Ocorrência, distribuição e abundância de peixes na região estuarina de Tramandaí, Rio Grande do Sul. Atlantica5, 49–66.

53

Silva C. (1984). Rejeição do pescado na pesca de camarão-rosa com “aviãozinho” em Tramandaí-RS. Rel. Int. Departamento Pesca2, 1–17.

54

Silva D. Paranhos R. Vianna M. (2016). Spatial patterns of distribution and the influence of seasonal and abiotic factors on demersal ichthyofauna in an estuarine tropical bay. J. Fish. Biol.89, 821–846. 10.1111/jfb.13033

55

Tonn W. M. Magnuson J. J. Rask M. Toivonen J. (1990). Intercontinental comparison of small-lake fish assemblages: the balance between local and regional processes. Am. Nat.136, 345–375. 10.1086/285102

56

Vasconcelos R. P. Henriques S. França S. Pasquaud S. Cardoso I. Laborde M. et al . (2015). Global patterns and predictors of fish species richness in estuaries. J. Anim. Ecol.84, 1331–1341. 10.1111/1365-2656.12372

57

Vasconcelos R. P. Le Pape O. Costa M. J. Cabral H. N. (2013). Predicting estuarine use patterns of juvenile fish with Generalized Linear Models. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. S120, 64–74. 10.1016/j.ecss.2013.01.018

58

Vieira J. Garcia A. Moraes L. (2010). A assembleia de peixes, in O Estuário da Lagoa dos Patos: Um Século de Transformações, ed SeeligerU.OdebrechtC. (Rio Grande: FURG), 79–88.

59

Vieira J. P. (1991). Juvenile mullets (Pisces: Mugilidae) in the estuary of Lagoa dos Patos, RS, Brazil. Copeia2, 409–418. 10.2307/1446590

60

Vieira J. P. (2006). Ecological analogies between estuarine bottom traw fish assemblages from Patos Lake, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil and York River, Virginia, USA. Rev. Bras. Zool.23, 234–247. 10.1590/S0101-81752006000100017

61

Vinagre C. Santos F. D. Cabral H. N. Costa M. J. (2009). Impact of climate and hydrology on juvenile fish recruitment towards estuarine nursery grounds in the context of climate change. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. S85, 479–486. 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.09.013

62

Würdig N. L. (1988). Distribuição espacial e temporal da comunidade de Ostracodes nas Lagoas Tramandaí e Armazém Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Acta. Limnol. Bras.11, 701–721.

Appendix

TABLE A1

| Order | Family | Species | AC | TRE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elopiformes | Elopidae | Elops saurus | 1 | |

| Clupeiformes | Clupeidae | Brevoortia pectinata | 411 | 1137 |

| Harengula clupeola | 6 | 8 | ||

| Platanichthys platana | 203 | 441 | ||

| Ramnogaster arcuata | 13 | 1 | ||

| Sardinella brasiliensis | 25 | 25 | ||

| Engraulidae | Anchoa marinii | 4 | ||

| Lycengraulis grossidens | 26 | 423 | ||

| Characiformes | Erythrinidae | Hoplias aff. malabaricus | 4 | |

| Curimatidae | Cyphocharax voga | 1 | ||

| Steindachnerina biornata | 1 | |||

| Characidae | Astyanax eigenmanniorum | 5 | 77 | |

| Astyanax aff. fasciatus | 21 | |||

| Astyanax lacustris | 54 | |||

| Diapoma alburnum | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hyphessobrycon boulengeri | 6 | |||

| Oligosarcus jenynsii | 19 | |||

| Oligosarcus robustus | 27 | |||

| Siluriformes | Heptapteridae | Pimelodella australis | 7 | |

| Rhamdia aff. quelen | 1 | |||

| Ariidae | Genidens barbus | 370 | ||

| Genidens genidens | 46 | 317 | ||

| Callichthyidae | Corydoras paleatus | 3 | ||

| Atheriniformes | Atherinopsidae | Atherinella brasiliensis | 482 | 2672 |

| Odontesthes argentinensis | 723 | 338 | ||

| Cyprinodontiformes | Poeciliidae | Phalloceros caudimaculatus | 19 | |

| Poecilia vivipara | 54 | |||

| Anablepidae | Jenynsia multidentata | 6 | 641 | |

| Beloniformes | Belonidae | Strongylura sp. | 1 | |

| Perciformes | Centropomidae | Centropomus parallelus | 1 | |

| Pomatomidae | Pomatomus saltatrix | 141 | 15 | |

| Carangidae | Caranx latus | 29 | 15 | |

| Chloroscombrus chrysurus | 2 | |||

| Selene vomer | 1 | |||

| Trachinotus carolinus | 199 | |||

| Trachinotus falcatus | 31 | 2 | ||

| Trachinotus marginatus | 7573 | 66 | ||

| Gerreidae | Diapterus rhombeus | 1 | ||

| Eucinostomus argenteus | 189 | |||

| Eucinostomus gula | 2 | 140 | ||

| Eucinostomus lefroyi | 8 | 970 | ||

| Eucinostomus melanopterus | 22 | 310 | ||

| Eugerres brasilianus | 1 | |||

| Haemulidae | Haemulidae | 66 | ||

| Sciaenidae | Menticirrhus americanus | 12 | 1 | |

| Menticirrhus littoralis | 198 | 1 | ||

| Micropogonias furnieri | 2902 | 341 | ||

| Paralonchurus brasiliensis | 1 | |||

| Pogonias cromis | 1 | |||

| Sciaenidae | 2 | 58 | ||

| Stellifer rastrifer | 344 | |||

| Umbrina canosai | 285 | 23 | ||

| Mugilidae | Mugil curema | 27052 | 10711 | |

| Mugil liza | 12684 | 23223 | ||

| Mugil sp.1 | 431 | 360 | ||

| Mugil sp.2 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Cichlidae | Geophagus brasiliensis | 12 | ||

| Gymnogeophagus spp. | 1 | |||

| Gobiidae | Bathygobius soporator | 6 | ||

| Ctenogobius schufeldti | 25 | 150 | ||

| Gobionellus oceanicus | 2 | |||

| Stromateidae | Peprilus paru | 1 | ||

| Pleuronectiformes | Pleuronectidae | Oncopterus darwinii | 14 | |

| Tetraodontiformes | Monacanthidae | Stephanolepis hispidus | 2 | |

| Pleuronectiformes | Paralichthyidae | Citharichthys spilopterus | 9 | 17 |

| Achiridae | Catathyridium garmani | 1 | ||

| Total number of samples | 297 | 405 | ||

| Total number of species | 41 | 55 | ||

| Total number of individuals | 54,295 | 42,987 |

Composition (total number of individuals collected) of the species registered for marine adjacent coastal area (AC) and Tramandaí River estuary (TRE) by order, family and species.

Also given are total number of samples, total number of species collected, and total number of individuals caught.

Summary

Keywords

juvenile fishes, connectivity, resilience, long-term studies, mullet

Citation

Vieira J, Román-Robles V, Rodrigues F, Ramos L and dos Santos ML (2019) Long-Term Spatiotemporal Variation in the Juvenile Fish Assemblage of the Tramandaí River Estuary (29°S) and Adjacent Coast in Southern Brazil. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:269. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00269

Received

15 January 2019

Accepted

03 May 2019

Published

29 May 2019

Volume

6 - 2019

Edited by

Mario Barletta, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Brazil

Reviewed by

Xianshi Jin, Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute (CAFS), China; Alan Whitfield, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, South Africa

Updates

Copyright

© 2019 Vieira, Román-Robles, Rodrigues, Ramos and dos Santos.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: João Vieira vieira@mikrus.com.br

This article was submitted to Marine Ecosystem Ecology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.