Abstract

Coastal countries have traditionally relied on the existing marine resources (e.g., fishing, food, transport, recreation, and tourism) as well as tried to support new economic endeavors (ocean energy, desalination for water supply, and seabed mining). Modern societies and lifestyle resulted in an increased demand for dietary diversity, better health and well-being, new biomedicines, natural cosmeceuticals, environmental conservation, and sustainable energy sources. These societal needs stimulated the interest of researchers on the diverse and underexplored marine environments as promising and sustainable sources of biomolecules and biomass, and they are addressed by the emerging field of marine (blue) biotechnology. Blue biotechnology provides opportunities for a wide range of initiatives of commercial interest for the pharmaceutical, biomedical, cosmetic, nutraceutical, food, feed, agricultural, and related industries. This article synthesizes the essence, opportunities, responsibilities, and challenges encountered in marine biotechnology and outlines the attainment and valorization of directly derived or bio-inspired products from marine organisms. First, the concept of bioeconomy is introduced. Then, the diversity of marine bioresources including an overview of the most prominent marine organisms and their potential for biotechnological uses are described. This is followed by introducing methodologies for exploration of these resources and the main use case scenarios in energy, food and feed, agronomy, bioremediation and climate change, cosmeceuticals, bio-inspired materials, healthcare, and well-being sectors. The key aspects in the fields of legislation and funding are provided, with the emphasis on the importance of communication and stakeholder engagement at all levels of biotechnology development. Finally, vital overarching concepts, such as the quadruple helix and Responsible Research and Innovation principle are highlighted as important to follow within the marine biotechnology field. The authors of this review are collaborating under the European Commission-funded Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action Ocean4Biotech – European transdisciplinary networking platform for marine biotechnology and focus the study on the European state of affairs.

Introduction

Marine environments provide a plethora of ecosystem services leading to societal benefits (Townsed et al., 2018). These services are mostly linked to supporting services (primary production and nutrient cycling), provisioning services (such as food) and cultural services, including tourism. The recent advancements of science and technology have facilitated the implementation of marine biotechnology, where marine organisms and their compounds are identified, extracted, isolated, characterized and used for applications in various sectors to benefit the society, ranging from food/feed to pharmaceutical and biomedical industries. Life in marine environments is diverse with wide environmental gradients in the physical, chemical, and hydrological parameters such as temperature, light intensity, salinity, and pressure. Marine organisms have adapted to these diverse environments by developing a broad spectrum of forms, functions, and strategies that play a crucial role for survival, adaptation and thriving in the multitude of these competitive ecosystems.

Among the vast array of evolutionary traits present in extant marine phyla, the production of biomolecules (secondary metabolites, enzymes, and biopolymers) is one of the most stimulating for biotechnology. Biomolecules mediate chemical communication between organisms, act as a protective barrier against adverse environmental conditions, serve as weapons for catching prey or for protection against predators, pathogens, extreme temperature or harmful UV radiation and are primordial in many other life-sustaining processes. Biomolecules have evolved to improve the organisms’ survival performance in their marine habitats and they are usually capable of exerting biological activity even at low concentrations to counteract dilution/dispersion effects occurring in the sea. The unique and complex structures of many marine metabolites enable the discovery of new and innovative applications with a commercial interest. Over 50% of the medicines currently in use originate from natural compounds, and this percentage is much higher for anticancer and antimicrobial treatment agents (Newman and Cragg, 2020). Apart from biomolecules, other properties and functions of marine organisms can also be beneficial and of interest to various industries, including the removal and degradation of individual chemical compounds or organic matter, as well as the development of intricate biochemical processes. However, marine resources remain largely underexplored and undervalorized.

Joint explorations of field and experimental biologists as well as chemists, supported by the recent advancements of techniques to access the ocean, fueled the increase in knowledge levels from the mid 20th century on. By the turn of the century, marine natural products chemistry became a mature and fully established subfield of chemistry with a focus on isolation and structure elucidation of secondary metabolites (Baslow, 1969; Faulkner, 2000; Gerwick et al., 2012).

Besides carrageenans or other polysaccharides that were extracted from seaweeds and widely used as food additives and cosmetic ingredients since the 1930s, modern marine biotechnology expanded after the 1970s with the intensification of research on marine organisms and their secondary metabolites (Rotter et al., 2020a). The first studies focused on natural products isolated from representative taxa inhabiting marine ecosystems like sessile macroorganisms including sponges, cnidarians, bryozoans, and tunicates, revealing a unique chemical diversity of bioactive metabolites (de la Calle, 2017). Multicellular organisms from all types of habitats were also reported to host complex and specialized microbiota (the holobiont concept, Margulis, 1991; Souza de Oliveira et al., 2012; Simon et al., 2019). These symbiotic microbial communities have major impacts on the fitness and function of their hosts and they contribute to the production of several secondary metabolites that play important roles against predators, pathogens or fouling organisms (Wilkins et al., 2019). This is especially true for soft-bodied, sessile organisms such as cnidarians and sponges, which are the best studied invertebrates and the most prolific source of bioactive molecules (Mehbub et al., 2014; Steinert et al., 2018). In fact, microorganisms make up approximately 40–60% of the sponge biomass (Yarden, 2014) and many bioactive molecules have been demonstrated or predicted to have a microbial origin (Gerwick and Fenner, 2013). Moreover, microorganisms represent nearly 90% of the living biomass in the oceans and are fundamental for the function and health of marine ecosystems by managing biogeochemical balances (de la Calle, 2017; Alvarez-Yela et al., 2019). They can produce a plethora of secondary metabolites with less stringent ethical and environmental requirements for research and product scale-up processes. Due to the broad range of manipulation possibilities, microorganisms are gaining importance for sustainable marine biotechnology and almost 60% of the new marine natural products nowadays are derived from microorganisms (Carroll et al., 2019). Nevertheless, macroorganisms still represent an active source and field of research for novel natural metabolites.

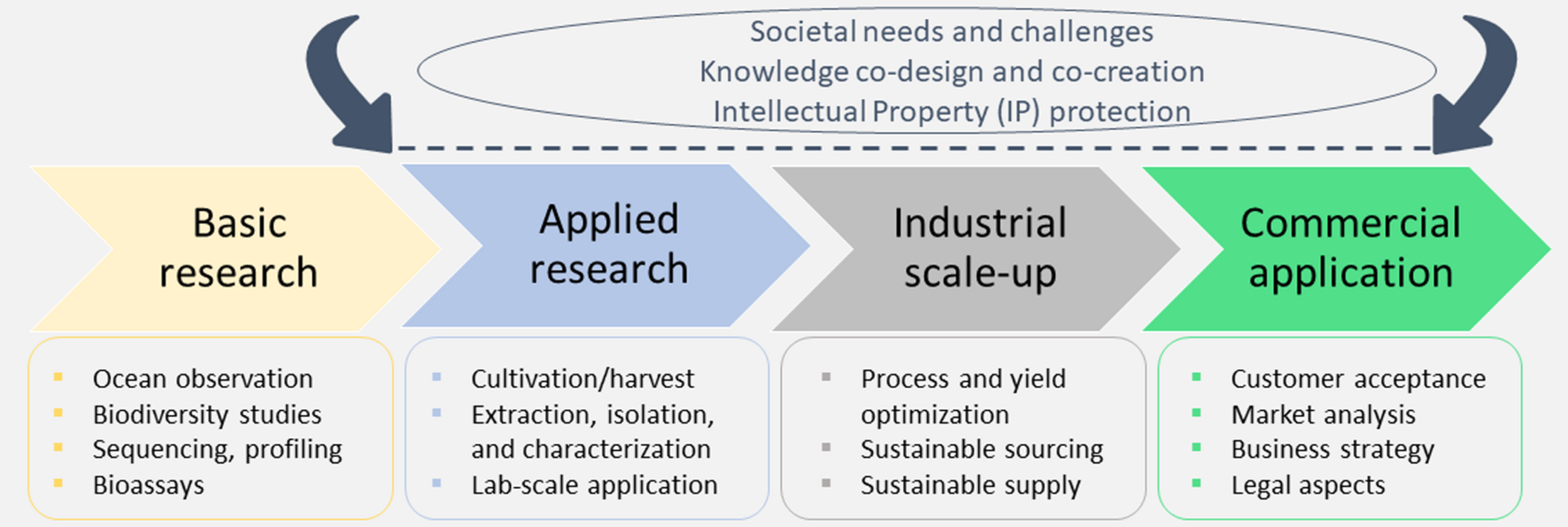

A simplified marine biotechnology workflow (Figure 1) depicts that product development from marine organisms is an inherently transdisciplinary and multidimensional task. The scientific community, industry, policy makers and the general public have a role to play in this process. Initially, the scientific community, while adhering to the ethical and legal guidelines, conducts systematic bioprospecting and screenings of marine organisms, elucidates the structure of bioactive molecules and their mechanisms of action, and sets up the protocols for product development. Often the financing of product development is dictated by the societal needs and challenges (such as health, well-being, or environmental protection) and suitable intellectual property (IP) protection. However, due to the transdisciplinary character of any biotechnology research, the co-design of processes and co-creation of knowledge is a necessary step in advancing the biodiscovery pipeline that ensures a faster product uptake. This also involves the collection of information about people’s perceived and actual needs, which is of paramount importance. Outreach activities are therefore conducted to engage the public in protecting the marine environment and promoting its sustainable use. Their feedback to both the scientific and industrial communities, either through directed questionnaires (in case of market research/analyses aiming to provide feedback on novel food, cosmeceuticals, and other products), workshops or other means of communication, often represents a key milestone for increasing consumers’ acceptance of bio-based products. Subsequent steps in new marine product development, e.g., scale-up, delivery format, validation of potency and toxicity, in vivo testing and implementation of statistically powered pre-clinical studies are generally performed by the pharmaceutical, biotechnological, biomedical, and food/nutraceuticals sectors.

FIGURE 1

A simplified representation of the marine biotechnology pipeline that is intrinsically interdisciplinary, combining basic and applied research with industry and business sectors.

The present article reviews some of the important aspects of marine biotechnology workflow. As marine biotechnology is an important contributor to bioeconomy, this concept is introduced in section “Bioeconomy.” In section “Marine biodiscovery areas,” we elaborate on hotspots of marine biodiscovery, from water column, the seafloor, microbial biofilms, beach wrack, to side streams. Section “Marine organisms and their potential application in biotechnology” introduces the main marine organisms being targeted for biotechnological research. Section “Methodology for exploration of marine bioresources” provides an overview of the general marine biotechnology pipeline and its key elements: organism isolation, data analysis and storage, chemical methods for isolation, and characterization of compounds. Production and scaling-up to guarantee sufficient supply at the industrial level are presented in section “Production upscaling.” Section “Use case scenarios” presents interesting use case scenarios where marine biotechnology can significantly address the societal challenges such as energy production, agronomy, bioremediation, food, feed, cosmetics, bio-inspired materials, and pharmaceuticals. Furthermore, the legislative and ethical issues arising from the development of marine biotechnology should not be overlooked and they are presented in section “Legislation and funding.” Section “Communication and stakeholder engagement in development finalization” concludes with a discussion on the importance of science communication both to raise consumer awareness on new products and establish new collaborations on one hand and implement knowledge transfer channels with stakeholders from the industrial, governmental and public sectors, on the other hand. The establishment of efficient communication that enables productive collaboration efforts is essential for the market entry and successful commercialization of marine biotechnology products. We conclude with an overview of the marine biotechnology roadmap in Europe.

Bioeconomy

Marine biotechnology is recognized as a globally significant economic growth sector. The field is mostly concentrated in the European Union (EU), North America and the Asia-Pacific (Van den Burg et al., 2019). Some of the globally renowned marine biotechnology centers are in China (e.g., the Institutes of Oceanology, the institutes of the Chinese Academy of Sciences), Japan (e.g., Shimoda Marine Research Center), United States (e.g., Scripps Institute of Oceanography), Australia (e.g., Australian Institute of Marine Science). In other countries, marine biotechnology is an emerging field to address global economic challenges, such as in South America (Thompson et al., 2018), Middle East (Al-Belushi et al., 2015) and Africa (Bolaky, 2020). However, the proper implementation of the field has its limitations: the lack of investment, need for appropriate infrastructure and human capital (Thompson et al., 2017, 2018). To enable the development of the marine bioeconomy, national or global partnerships with the leading research labs are established (Vedachalam et al., 2019), including European participation.

The European Commission defines blue bioeconomy as an exciting field of innovation, turning aquatic biomass into novel foods, feed, energy, packaging, and other applications1. This is also reflected in the revised EU Bioeconomy Strategy2, setting several priorities that are relevant for marine biotechnology, such as developing substitutes to plastics and to other fossil-based materials that are bio-based, recyclable and marine-biodegradable. In the European Union, blue economy (including all the sectors) reached €750 billion turnover and employed close to 5 million people in 2018 (European Commission, 2020). Marine biotechnology is a niche within the ocean-based industries. As this is a growing field, it is projected that in 2030 many ocean-based industries will outperform the growth of the global economy as a whole, providing approximately 40 million full-time equivalent jobs (Rayner et al., 2019). Besides creating new jobs, the development of marine biotechnology can contribute to the existing employment structures by diversification of additional income for fishermen or aquaculture specialists. In this aspect, the policy making sector is aware that future marine research priorities should include improved techniques for mass production and processing of marine biomass (European Commission, 2019). This imposes several challenges: (i) the need for harmonization and later standardization of processes, protocols and definitions; (ii) the need to establish ethical guidelines that will be endorsed and respected by national administrative authorities and concern the fair share and use of biological resources; (iii) the need to bridge the collaboration and communication gap between science and industry on one hand, and policy makers on the other. This entails some changes in the mode of action. For example, networking activities such as brokerage events and participatory workshops should be used for the exchange of expertise, opinion and potential co-creation of strategic documents. (iv) There is a need to develop strategies for showcasing individual expertise, such as the creation of open access repositories of experts and their contacts. (v) Finally, there is a need to sustain the investment into ocean observations that provide evidence of regulatory compliance and support the valuation of natural assets and ecosystem services (Rayner et al., 2019). Open science, also through full access to research publications (embraced by Plan S and supported by the EC3) and access to data are of key importance here, enabling fair access to public knowledge.

Marine Biodiscovery Areas

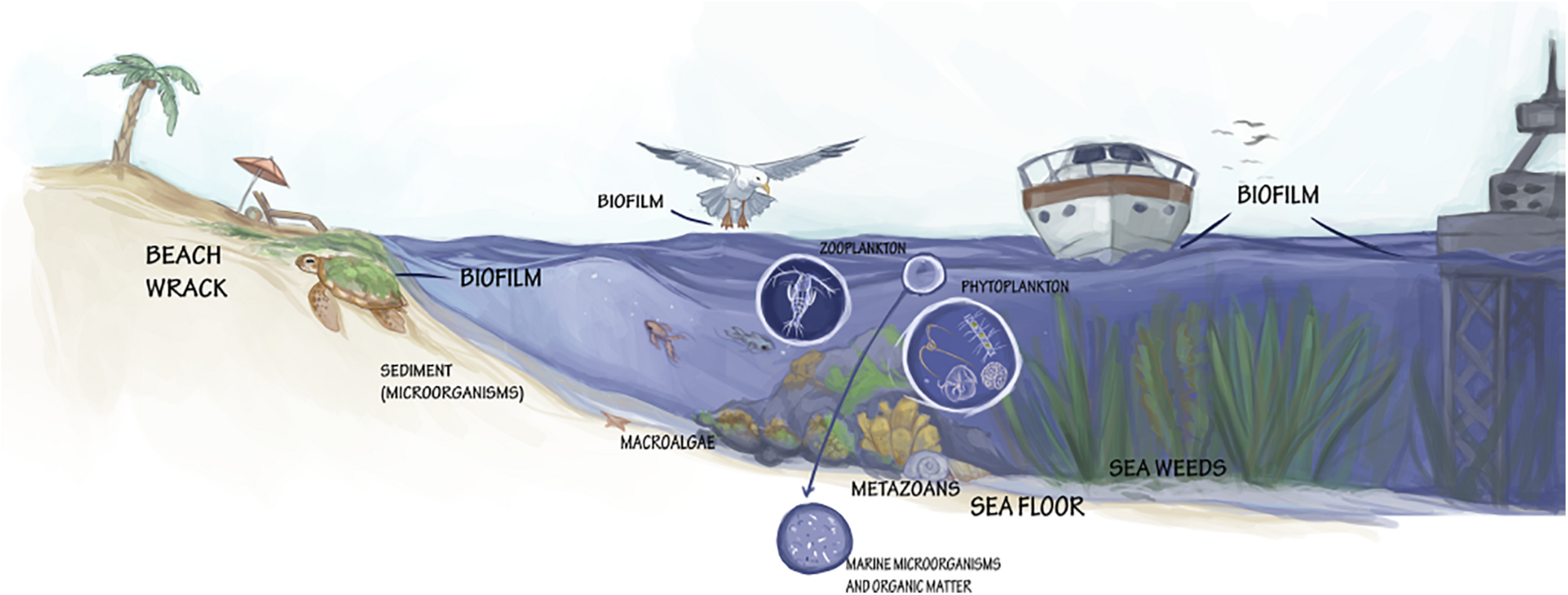

The marine environment with its unique physico-chemical properties harbors an extraordinary source of yet undiscovered organisms (Figure 2) and their chemical/biochemical compounds to develop commercially interesting bio-based products.

FIGURE 2

Various formations and taxa with valorization potential for marine biotechnology.

Since the early 21st century, the exploration of marine microbial biodiversity has been driven by the development of high-throughput molecular methods such as High Throughput Sequencing (HTS), and their direct application on intact seawater samples without requiring any prior isolation or cultivation of individual microorganisms (Shokralla et al., 2012; Seymour, 2019). The HTS approach utilizes specific gene regions (barcodes) to provide massive amounts of genetic data on the various microbial communities with continuing improvements in data quality, read length and bioinformatic analyses methods, leading to a better representation of the genetic based taxonomic diversity of the sample. HTS methods detect both the most abundant community members but also the rare species, which cannot otherwise be retrieved by traditional culture-dependent methods. The Global Ocean Sample Expedition (GOS4) led by J. Craig Venter Institute is exemplary for that. Recently, the most important step forward in elucidating world-wide eukaryotic biodiversity were cross-oceanic expeditions such as Malaspina, Tara Oceans, and Biosope (Grob et al., 2007; Claustre et al., 2008; Bork et al., 2015; Duarte, 2015; de Vargas et al., 2015). These studies have also confirmed that much of the eukaryotic plankton diversity in the euphotic zone is still unknown and has not been previously sequenced from cultured strains. The Tara Oceans dataset also provided significant new knowledge to protistan diversity, identifying many new rDNA sequences, both within known groups and forming new clades (de Vargas et al., 2015).

The isolation of DNA from environmental samples – eDNA – is already well established in the field of microbiology and marine monitoring (Diaz-Ferguson and Moyer, 2014; Pawlowski et al., 2018). Metabolic engineering is being used for characterization of bacterial communities in sediments since the 1980’s (Ogram et al., 1987) and monitoring entire microbial populations in seawater samples (Venter et al., 2004). However, this approach has been applied to the analyses of macroorganisms only in recent years (Thomsen et al., 2012; Kelly et al., 2017; Jeunen et al., 2019). The study of eDNA in the water column (Keuter et al., 2015) or in seafloor sediments (Keuter and Rinkevich, 2016) has received considerable attention for high-throughput biomonitoring using metabarcoding of multiple target gene regions, as well as for integrating eDNA metabarcoding with biological assessment of aquatic ecosystems (Pawlowski et al., 2018). In addition, targeted detection of species using quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) assays have been implemented for both micro- and macroorganisms (Gargan et al., 2017; Hernández-López et al., 2019) in seawater samples. The potential for using eDNA in aquatic ecosystems has been the topic of several concerted actions (like DNAqua-Net COST Action5; Leese et al., 2016) and there have been considerable efforts to standardize DNA approaches to supplement or replace the existing methods, often dictated by regulatory frameworks such as the European Union Water Framework Directive– EU WFD [Directive 2000/60/EC] and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive – EU MSFD [Directive 2008/56/EC]. In-depth knowledge on the biodiversity of marine microorganisms has been substantially improved with the adaptation of various DNA barcoding protocols and approaches (Leese et al., 2016; Paz et al., 2018; Weigand et al., 2019). Although metagenomic data generated from eDNA samples can provide vast amounts of new information, datasets from complex microbial communities are difficult to process. Metagenome assemblies and their functional annotations are challenging (Dong and Strous, 2019). A large fraction (>50%) of the detected genes has no assigned function. The use of functional metagenomics applications and tools (including metagenomics coupled with bioactivity screening/enzyme screening, meta-transcriptomics, meta-proteomics, meta-metabolomics), is key to solve this problem. One of the most used applications of functional metagenomics is the activity-based screening of metagenomics libraries. Enzyme discovery is currently the largest field of its use, including marine enzymes (Hårdeman and Sjöling, 2007; Di Donato et al., 2019).

High throughput sequencing offers a culture-independent characterization of microbial diversity, but the biotechnological exploitation of marine microorganisms often requires their cultivation in pure cultures and the optimization of production yield for the compounds of interest. It is estimated that over 85% of microorganisms are unculturable under the current laboratory cultivation techniques (Wade, 2002; Lloyd et al., 2018). This is the “great plate anomaly,” a consequence of the difficulties in mimicking the complexity of natural habitats in the laboratory (i.e., cultivations under finely tuned conditions for various parameters, such as temperature, salinity, oxygen, agitation and pressure, and use of species-specific growth substrates with trace elements). Additionally, cell-to-cell interactions, occurring both between symbiotic and competing organisms in the natural environment may be absent when pure cultures (axenic) are grown in laboratory conditions (Joint et al., 2010). Other strategies, like mimicking in situ nutritional composition and physico-chemical conditions as well as the addition of signaling molecules are used to increase the diversity of isolated marine microorganisms (Bruns et al., 2003). It is however important to realize the limitations of methods and tools used in culture-based techniques. For example, the sampling and isolation of bacteria from seawater relies on filters with specific retention characteristics (e.g., 0.22 micron pore size), that typically fail to capture the smaller bacteria (Hug et al., 2016; Ghuneim et al., 2018). Hence, the establishment of pure microbial cultures remains one of the main hurdles in the discovery of bioactive constituents in microorganisms. To increase the number of harnessed microbes, a new generation of culture approaches has been developed that mimic the proximity of cells in their natural habitat and exploit interspecific physiological interactions. Several techniques, such as diffusion chambers (Kaeberlein et al., 2002), the iChip (Nichols et al., 2010), as well as the recently developed miniaturized culture chips (Chianese et al., 2018) have been employed to address microbial cultivation problems. Another reason preventing the wider valorization of marine microorganisms is that some strains cannot exist in nature without their symbionts: often microorganisms that are associated or in symbiosis with marine macroorganisms are the true metabolic source of marine natural products (McCauley et al., 2020). To uncover the potential of these species, many microbiological studies are focusing on bulk-community dynamics and how the performance of ecosystems is supported and influenced by individual species and time-species interaction (Kouzuma and Watanabe, 2014). Such advancements in the field of microbial ecology provide robust background knowledge for biotechnological exploitation. Hence, as natural communities are complex and difficult to assess, characterize and cultivate in artificial conditions, researchers use synthetic microbial communities of reduced complexity in their laboratory studies. These artificial communities are prepared by retaining only the microorganisms carrying out a specific biosynthetic process, as well as those providing culture stability and performance, to enable their use in biotechnological applications (Großkopf and Soyer, 2014).

To maximize the biotechnological potential of our oceans it is essential to exploit microbial communities with their complex networking systems engaged in cooperation and competition. Currently, the integrative omics approach provides comprehensive information describing the community through sophisticated analyses from genes to proteins and metabolites. Shotgun metagenome analysis allows the sequencing of genomes of the dominant organisms to link the enzymes of interest directly to organisms. Functional metagenomics is an excellent tool for studying gene function of mixed microbial communities, with a focus on genomic analysis of unculturable microbes and correlation with their particular functions in the environment (Lam et al., 2015). The conventional approach to construction and screening of metagenomic libraries, which led to the discovery of many novel bioactive compounds as well as microbial physiological and metabolic features, has been improved by sequencing of complete microbial genomes from selected niches. Metatranscriptomics and metaproteomics, important for further functional analysis of microbial community composition, may indicate their role in many crucial processes such as carbon metabolism and nutrition acquisition (Shi et al., 2009).

The development of sequencing, computational and storage capacities reduced the financial and time investment needed for new discoveries of biotechnological interest. This is now enabled with genome mining, the process of extracting information from genome sequences to detect biosynthetic pathways of bioactive natural products and their possible functional and chemical interactions (Trivella and de Felicio, 2018; Albarano et al., 2020). It is used to investigate key enzymes of biosynthetic pathways and predict the chemical products encoded by biosynthetic genes. This can reveal the locked bioactive potential of marine organisms by utilizing the constantly evolving sequencing technologies and software tools in combination with phenotypic in vitro assays. This approach can facilitate natural products discovery by identifying gene clusters encoding different potential bioactivities within genera (Machado et al., 2015). These bioactive molecules are usually synthesized by a series of proteins encoded by biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) which represent both a biosynthetic and an evolutionary unit. The complete genome sequence of several marine microorganisms revealed unidentified BGCs even in highly explored species, indicating that the potential of microorganisms to produce natural products is much higher than that originally thought (Lautru et al., 2005). BGCs are mostly classified based on their product as: saccharides, terpenoids, polyketide synthases (PKSs), non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), and ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs). PKS and NRPS have long been attractive targets in genome mining for natural products with applications in medicine. For example, salinilactam A was the first compound spotted by genome mining from a marine-derived actinomycete (Zerikly and Challis, 2009) and the angucyclinones, fluostatins M–Q, produced by Streptomyces sp. PKU-MA00045 were isolated from a marine sponge (Jin J. et al., 2018). In parallel, a recent increase in discoveries of novel RiPP classes revealed their bioactive potential in the biomedical field, e.g., as novel antibiotics (Hudson and Mitchell, 2018). Thus, different methodologies are currently available for RiPP genome mining, focused on known and/or novel classes finding, including those based on identifying RiPP BGCs, or identifying RiPP precursors using machine-learning classifiers (de los Santos, 2019; Kloosterman et al., 2021).

With the development of in situ molecular tools (such as fluorescence in situ hybridization – FISH), it is possible to quantify and follow the dynamics of specific bacterial groups (Pizzetti et al., 2011; Fazi et al., 2020). Such tools may also help to uncover whether microbial communities with explicit characteristics can favor biosynthesis processes for specific compounds of interest.

Water Column, Seafloor, and Sediments

Spatial and temporal distribution patterns, as well as the actual abundance of phytoplankton, bacterioplankton and viruses are defined by a variety of physico-chemical parameters (e.g., light availability, nutrient supply, temperature, water column stratification) and biological processes (e.g., microbial activity, competition, zooplankton grazing pressure, viral lysis) (Field et al., 1998; Kirchman, 2000; Mousing et al., 2016). Seafloor provides diverse habitats for organisms. Besides forming stromatolites in the sediments surface, cyanobacteria can secrete or excrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) (Golubic et al., 2000) that can further stabilize sediments and protect them from antimicrobial compounds and other various biotic and abiotic stressors (Costa et al., 2018). Ocean sediments cover the greatest portion of the Earth’s surface and host numerous bacterial phyla and individual species, the biosynthetic capabilities of which are largely unknown. This is particularly true for the poorly accessible deep seas. As an example, phylogenetic studies from the ultra-oligotrophic eastern Mediterranean Sea have shown that sediments down to almost 4,400 m depth host a vast diversity of bacteria and archaea (Polymenakou et al., 2015). More importantly, a large fraction of 16S rDNA sequences retrieved from the same environment (∼12%) could not be associated with any known taxonomic division, implying the presence of novel bacterial species (Polymenakou et al., 2009). Moreover, the OceanTreasures expedition revealed new and diverse actinobacteria strains adapted to life in the ocean (i.e., marine obligates) with biotechnological potential and other bacteria that are capable of producing exopolysaccharides, obtained from sediments collected off the Madeira Archipelago, Portugal, down to 1,310 m in depth (Prieto-Davó et al., 2016; Roca et al., 2016).

Given that the world’s ocean average depth is 2,000 m, the advent of diving and vessel-operated sampling equipment and techniques, such as dredges, collectors and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), allowed exploring previously inaccessible environments (such as hydrothermal vents and deep sea), opening new prospects and horizons for marine biotechnology. The exploration of these extreme environments requires specific equipment, skills, and resources for long cruises, which include systematic mapping, especially in the deep ocean and seabed.

Submarine caves were recently recognized as biodiversity hotspots (Gerovasileiou and Voultsiadou, 2012; Gerovasileiou et al., 2015), with most of them being largely unexplored. The organisms hosted in these environments are of particular biotechnological interest. A range of mesophilic and thermotolerant microorganisms have been reported from submarine caves and cavities, characterized by elevated concentrations of hydrogen sulfide (Canganella et al., 2006), while methanogenic and sulfate reducing microbial species with potential applications in biogas production and bioremediation have been isolated from similar environments (Polymenakou et al., 2018). Besides biogas production, the biotechnological interest of bacteria originating from unique submarine caves could be even greater in terms of their secondary metabolites.

Biofilms

Biofilm formation is an important life strategy for microorganisms to adapt to the wide range of conditions encountered within aquatic environments (Figure 2). Biofilms are complex and dynamic prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbial communities. Besides being a novel species bank of hidden microbial diversity and functional potential in the ocean, biofilms are increasingly being recognized as a source of diverse secondary metabolites (Battin et al., 2003; Zhang W. et al., 2019). Scarcity of some microbial species in seawater prevents their capture in global sequencing efforts and they can only be detected when their relative abundance increases during biofilm formation. The biofilm microbiome can be analyzed by metagenomic approaches such as Illumina and visualized by microscopic imaging techniques such as CARDFISH (Parrot et al., 2019). Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) techniques, such as DESI-MSI allows the identification and spatial distribution and localization of marine microbial natural products in the biofilm (Papazian et al., 2019; Parrot et al., 2019).

The main component of biofilms, accounting for up to 90% of the dry biomass, are EPS, which comprise polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA, lipids and other substances, forming a complex 3-D structure that holds the cells nearby (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). This matrix of EPS keeps the biofilm attached to the colonized surface (Battin et al., 2007; Flemming and Wingender, 2010). Moreover, the dense EPS matrix provides a protective envelope against biocides and antibiotics produced by other (micro)organisms, and physical stress. Exopolysaccharides can remain bound to the cell surface or be directly released into the aquatic environment. The assessment of the distribution of specific microbes within the biofilm and their exopolysaccharide composition is therefore of crucial importance for biotechnological applications (Pereira et al., 2009; Lupini et al., 2011; Fazi et al., 2016). EPS composition varies greatly depending on the microorganisms present and environmental conditions (e.g., shear forces, temperature, nutrient availability, Di Pippo et al., 2013). This compositional variability suggests the contribution of various biosynthetic mechanisms, that are, in turn, dependent on environmental and growth conditions (De Philippis and Vincenzini, 2003; Pereira et al., 2009). EPS are responsible for adhesion of microorganisms to surfaces, aggregation of microbial cells, cohesion within the biofilm, retention of water, protection, and enzymatic activity (Žutić et al., 1999). Furthermore, they are important for the absorption of organic and inorganic compounds, exchange of genetic material, storage of excess carbon and they can serve as a nutrient source (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). These features can be exploited in different applications. The biodegradable and sustainable carbohydrate-based materials in biofilms provide mechanical stability and can be exploited as packaging materials, films, prosthetics, food stabilizers and texturizers, industrial gums, bioflocculants, emulsifiers, viscosity enhancers, medicines, soil conditioners, and biosorbents (Li et al., 2001; Roca et al., 2016). Furthermore, the extracellular proteins and enzymes can find interesting applications in medical biofilm dispersion or bioconversion processes. In addition, EPS contain biosurfactants with antimicrobial activity and extracellular lipids with surface-active properties that can disperse hydrophobic substances, which can be useful for enhanced oil recovery or bioremediation of oil spills (Baldi et al., 1999; Flemming and Wingender, 2010). Understanding the molecular mechanisms behind various secondary metabolites that are used for interspecies communication within biofilms will also be useful in combating the biofilm-forming pathogenic bacteria (Barcelos et al., 2020).

Biofilms are involved in marine biofouling and defined as the accumulation of microorganisms, algae and aquatic animals on biotic and abiotic surfaces, including human-made structures that are immersed in seawater (Amara et al., 2018). The environmental impact of biofouling is significant due to the reduction of the water flow and the increase of debris deposition below the aquaculture farms (Fitridge et al., 2012). Biofouling can seriously affect the environmental integrity and consequently impact the worldwide economy. Ships’ hulls can increase fuel consumption by up to 40% due to the increased drag and weight of the ships (Amara et al., 2018) and can also increase ship propulsion up to 70% (Trepos et al., 2014), resulting in a rise in carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide emissions by 384 and 3.6 million tons per year, respectively (Martins et al., 2018). The transport delays, the hull repairs and the biocorrosion cost an additional 150 billion dollars per year (Schultz, 2007; Hellio et al., 2015). Moreover, ships might transport invasive fouling species, thus threatening indigenous aquatic life forms (Martins et al., 2018). The use of antifouling paints incorporating biocides like heavy metals and tributyltin was the chemical answer to the fouling issue, but these substances are known to leach into the water and pose deleterious effects to many non-target species (Yebra et al., 2004; Amara et al., 2018). Marine natural products, originating from bacteria as well as higher organisms, can represent an environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic biocides (Eguía and Trueba, 2007; Adnan et al., 2018; Bauermeister et al., 2019) and an economically advantageous solution to foul-release polymers (Trepos et al., 2014; Chen and Qian, 2017; Pereira et al., 2020). In particular, the compounds that inhibit quorum sensing signals that regulate the microbial colonization and formation of aggregates could mitigate the impact of biofilms (de Carvalho, 2018; Salehiziri et al., 2020).

Biofilms are useful as a core part of the nitrification bioreactors, operated in recirculating aquaculture systems and are called biofilters, as they convert excreted ammonia from animals to nitrates. This restores healthy conditions for farmed fish and shrimp. Aquaculture biofilms have a complex microbiome, the composition of which varies depending on the farmed species and culture conditions. However, these biofilms can also harbor pathogens that can be harmful for farmed fish. Therefore, careful manipulation of microbial communities associated with fish and their environment can improve water quality at farms and reduce the abundance of fish pathogens (Bentzon-Tilia et al., 2016; Bartelme et al., 2017; Brailo et al., 2019).

Beach Wrack

Beach wrack (Figure 2) consists of organic material (mainly seagrasses and seaweeds) washed ashore by storms, tides, and wind. According to the European Commission Regulation (EC) No 574/2004 and the European Waste Catalog (EWC), waste from beaches is defined as “municipal wastes not otherwise specified” (Wilk and Chojnacka, 2015). Therefore, specific regulations within each country are implemented concerning the collection of municipal solid waste (Guillén et al., 2014) which typically results in large amounts of unexploited beach wrack. Moreover, the removal of wrack eliminates valuable nutrients that may affect sandy beach and dune ecosystem’s food chains, and it can cause a reduction in species abundance and diversity (Defeo et al., 2009). For example, the role of Posidonia oceanica “banquettes” (dead leaves and broken rhizomes with leaf bundles) is fundamental in protecting beaches from erosion, and its removal can have a dramatic negative impact on P. oceanica ecosystem services, including the conservation of beaches (Boudouresque et al., 2016). On the other hand, a high deposition of beach cast can be encountered from the blooms of opportunistic macroalgae as a result of elevated nutrient loading. In such cases, a removal of beach cast is seen as a mitigation action to remove excess nutrients from the marine environments (Weinberger et al., 2019). The collected beach wrack and its chemical constituents could find use in interesting biotechnological applications, but such harvesting interventions should also take into account the ecological role that algae and plant debris play in the coastal ecosystems (Guillén et al., 2014). Collection and handling methods should therefore be tailored to fit the characteristics of each coastal system, including the type of the dominant species and the quantities of biomass. Solutions should then be verified from economical, technical, and environmental perspectives.

As beach wrack often includes contaminants, the decay of this biomass can lead to the reintroduction of toxic pollutants into the aquatic environment. Before the implementation of industrial agriculture practices in the 20th century, beach wrack was used in Europe as a fertilizer (Emadodin et al., 2020). The high salt content was reduced by leaving the biomass on the shore for weeks to months so that the salt could be washed out by the rain. The implementation of adapted recycling methods should be included for further processing of wrack biomass before its removal from the coastal ecosystem. Besides high salt content, sand removal is another obstacle for the immediate utilization of beach wrack. New technologies, including the magnetic modification of marine biomass with magnetic iron oxide nano- and microparticles and its subsequent application for the removal of important pollutants can be considered (Angelova et al., 2016; Safarik et al., 2016, 2020).

Coastal biomass displays good biotransformation potential for biogas, which is comparable to higher plants containing high amounts of lignin. Besides biogas production, the bioactive substances of this biomass (mainly exopolysaccharides) can be used to develop cosmetics, as well as for pharmaceutical and biomedical products (Barbot et al., 2016). This biomass may also be used for the removal of various types of contaminants by biosorption (Mazur et al., 2018). Hence, there is interest in the adoption of circular economy principles for the sustainable management of coastal wrack biomass. This can enable the production of valuable solutions, while at least partially substituting the use of fossil fuels, the use of electricity at a biogas plant and the use of chemical fertilizers (using degassed or gasified/torrefied biomass), thus avoiding “dig and dump” practices and landfill emissions. The implementation of these methods can also contribute to local small-scale energy unit development in coastal regions (Klavins et al., 2019).

Seafood Industry By-Products/Side Stream Valorization

Fish represent the main commodity among marine resources; of the 179 million tons of global production over 85% was used for direct human consumption in 2018 (FAO, 2020). Due to the lack of adequate infrastructures and services to ensure proper handling and preservation of the fish products throughout the whole value chain, 20–80% of marketed fish biomass is discarded or is wasted between landing and consumption (Gustavsson et al., 2011; Ghaly et al., 2013). In addition, large quantities of marine by-products are generated mainly as a result of fish and shellfish processing by industrial-scale fisheries and aquaculture (Ferraro et al., 2010; Rustad et al., 2011; Radziemska et al., 2019). Besides fish, the phycocolloid industry also generates considerable amounts of seaweed by-products that are good sources of plant protein, cellulosic material and contain taste-active amino acids. They can also be used in food flavoring (Laohakunjit et al., 2014), animal feed (Hong et al., 2015) or as feedstock biomass for bioenergy (Ge et al., 2011).

The by-products are often treated as waste, despite containing valuable compounds. Direct composting and combustion should be avoided in favor of recovery of valuable compounds. The biorefinery concept integrates biomass conversion processes and equipment to produce value-added chemicals, fuels, power and heat from various types of side stream (waste) biomass. In this context, marine biorefinery employs recycling/reutilization of marine waste biomaterials to produce higher-value biologically active ingredients/components, such as minerals, proteins, peptides, lipids, long-chain ω-3 fatty acids, enzymes, and polysaccharides (Nisticò, 2017; Kratky and Zamazal, 2020; Kumar et al., 2020; Prabha et al., 2020). The processed leftovers from fish and shellfish typically include trimmings, skins and chitin residues from crustacean species, heads, frames (bone with attached flesh) and viscera. Only a small portion of these cut-offs is further processed, mostly into fish meal and fish oil, while a part is processed to extract value-added compounds that can be used in the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical products (Senevirathne and Kim, 2012) for prevention and management of various disease conditions, such as those associated with metabolic syndromes (Harnedy and FitzGerald, 2012). Extracted collagen can be used for wound healing dressings, drug delivery, tissue engineering, nutritional supplement, as an antibiofilm agent, or as an ingredient in cosmetics and pharmaceutical products (Abinaya and Gayathri, 2019; Shalaby et al., 2019). Gelatin and chondroitin have applications in the food, cosmetic and biomedical sectors. Chitin and chitosan resulting from shellfish are other examples of marine by-products with applications in the food, agriculture and biomedicine sectors (Kim and Mendis, 2006). Hydroxyapatite derived from fish bone has demonstrated relevance for dental and medical applications (Kim and Mendis, 2006) and can also be used as feed or fertilizers in agriculture or horticultural use. Cephalopod ink sac is considered a by-product that is discharged by most processing industries (Hossain et al., 2019). However, the ink from squid and cuttlefish can be a potential source of bioactive compounds, such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, or chemopreventive agents (Smiline Girija et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2009; Shankar et al., 2019). Moreover, microbes that live in fishes’ slimy mucus coating can be explored as drug-leads for the pharmaceutical industry (Estes et al., 2019). The main challenge for the valorization of all these by-products is their very short shelf-life, implying that the processing steps should be fast enough to prevent oxidation and microbial degradation.

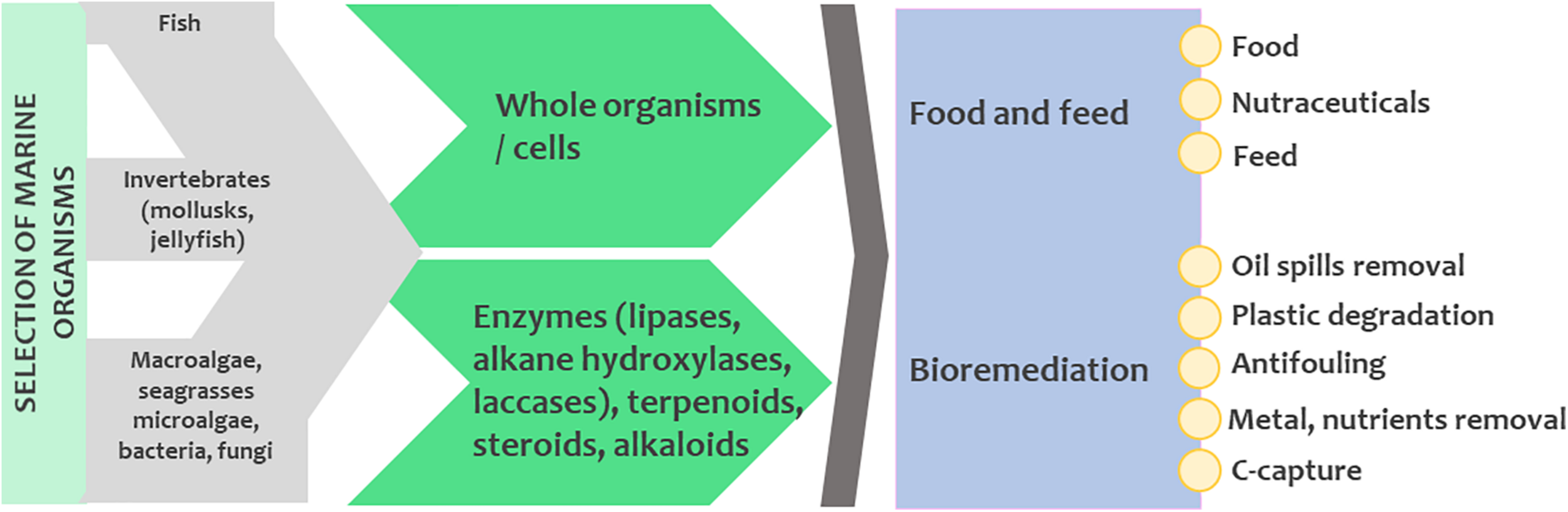

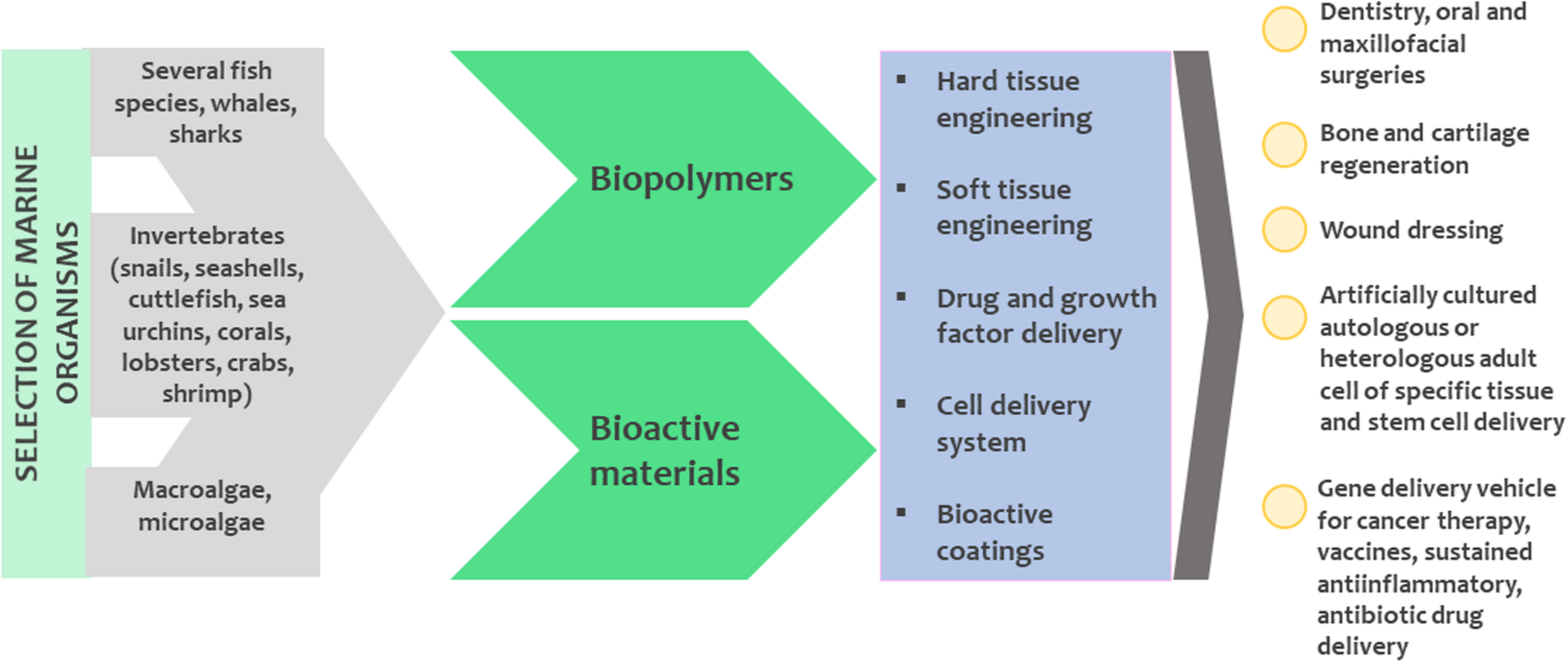

Marine Organisms and Their Potential Application in Biotechnology

All groups of marine organisms have the potential for biotechnological valorization (Figure 2). Table 1 presents the different groups of marine organisms and their main biotechnological applications that are currently being developed, while a more detailed discussion on this topic follows in subsequent sections.

TABLE 1

| Source | Use | Representative phyla (exemplary genera/species) | Challenges |

| Metazoans | Medicine, cosmetics | Tunicates - Chordata (Ecteinascidia turbinata), Mollusca (Conus magus), sponges - Porifera (Mycale hentscheli), Cnidaria (Sinularia sp., Clavularia sp., Pseudopterogorgia sp.) | Sourcing and supply sustainability |

| Macroalgae and seagrasses | Food, feed, medicine, cosmetics, nutraceuticals, biofertilizers/soils conditioners, biomaterials, bioremediation, energy | Rhodophyta (Euchema denticulatum, Porphyra/Pyropia spp., Gelidium sesquipedale, Pterocladiella capillacea, Furcellaria lumbricalis, Palmaria spp., Gracilaria spp.), Chlorophyta (Ulva spp.), Ochrophyta (Laminaria hyperborea, Laminaria digitata, Ascophyllum nodosum, Saccharina japonica, Saccharina latissima, Sargassum, Undaria pinnatifida, Alaria spp., Fucus spp.), seagrasses (Zostera, Cymodocea) | Sourcing and supply sustainability Yield optimization, large-scale processing and transport Disease management |

| Microalgae | Sustainable energy, cosmetics, food, feed, biofertilizers, bioremediation, medicine | Chlorophyta (Chlorella, Haematococcus, Tetraselmis), Cryptophyta, Myzozoa, Ochrophyta (Nannochloropsis), Haptophyta (Isochrysis), Bacillariophyta (Phaeodactylum) | Bioprospecting and yield optimization (1 – increase in biomass/volume ratio, 2 – increase yield of compound/extract production and 3 – Improve solar-to-biomass energy conversion) |

| Bacteria and Archaea | Medicine, cosmetics, biomaterials, bioremediation, biofertilizers | Actinobacteria (Salinispora tropica), Firmicutes (Bacillus), Cyanobacteria (Arthrospira, Spirulina), Proteobacteria (Pseudoalteromonas, Alteromonas), Euryarchaeota (Pyrococcus, Thermococcus) | Culturing for non-culturable species, yield optimization |

| Fungi | Bioremediation, medicine, cosmetics, food/feed, biofertilizers | Ascomycota (Penicillium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Cladosporium) | Limited in-depth understanding, yield optimization |

| Thraustochytrids | Food/feed, sustainable energy production | Bigyra (Aurantiochytrium sp.), Heterokonta (Schizochytrium sp.) | Limited in-depth understanding, yield optimization |

| Viruses | Medicine, biocontrol | Mycoviruses, bacteriophages | Limited in-depth understanding, yield optimization |

A non-exhaustive example list of the most prominent marine taxa, their use and challenges toward production scale-up.

Metazoans

Most initial studies on marine natural products focused on marine metazoans such as sponges, cnidarians, gastropods and tunicates, as they were representative organisms of the studied marine ecosystems and relatively easy to collect by scuba diving (reviewed in Molinski et al., 2009). These sessile organisms with limited motility tend to produce a vast assemblage of complex compounds with defensive (e.g., antipredatory, antifouling) or other functional properties such as communication or chemoreception (Bakus et al., 1986). The first described drugs from the sea that were used in clinical trials decades after their discoveries were vidarabine (ara-A®) and cytarabine (ara-C®), two chemical derivatives of ribo-pentosyl nucleosides extracted in the 1950s from a Caribbean marine sponge, Tectitethya crypta (Bergmann and Feeney, 1951). Other early drugs originating from the sea were ziconotide, a synthetic form of ω-conotoxin, extracted from the Pacific cone snail Conus magus and commercialized under the trade name Prialt® for the treatment of chronic pain (Olivera et al., 1985; Jones et al., 2001), ω-3 acid ethyl esters (Lovaza®) from fish for hyperlipidemia conditions, the anticancer drugs Eribulin Masylate (E7389) macrolide marketed as Halaven®, and Monomethyl auristatin E derived from dolastatin peptides isolated from marine shell-less mollusk Dolabella auricularia commercialized as Adcetris® (Jimenez et al., 2020). In 2007, about 40 years after its initial extraction from the Caribbean ascidian Ecteinascidia turbinata, ecteinascidin-743 (ET-743), also known as trabectedin or its trade name Yondelis®, was the first marine-derived drug to be approved for anticancer treatments (Rinehart et al., 1990; Corey et al., 1996; Martinez and Corey, 2000; Aune et al., 2002). Multiple strategies were tested to produce the drug at the industrial scale, including mariculture and total synthesis, and eventually a semisynthetic process starting from cyanosafracin B, an antibiotic obtained by fermentation of Pseudomonas fluorescens, solved the problem (Cuevas et al., 2000; Cuevas and Francesch, 2009). Since then, the discovery of marine-derived compounds extracted from metazoans is expanding (Molinski et al., 2009; Rocha et al., 2011) and sponges and cnidarians are the most prominent as far as novel marine natural products discovery is concerned (Qi and Ma, 2017; Blunt et al., 2018; Carroll et al., 2020). The annual number of new compounds reported for each is consistently high at approximately 200 along the past decade, while the respective number for other widely investigated marine phyla, such as mollusks, echinoderms and tunicates (subphylum Chordata), is limited between 8 and 50 for the same period (Carroll et al., 2020). Bryozoans are acknowledged as an understudied group of marine metazoans with regard to metabolites production, with the newly discovered natural products fluctuating from zero to slightly over 10 in the last few years (Blunt et al., 2018; Carroll et al., 2020). Those pronounced differences in marine product discovery either reflect an innate trend toward the production of complex secondary metabolites (Leal et al., 2012) or the study effort toward a phylum or another taxonomic group, often due to the lack of taxonomic expertise for some groups. Yet, the differences in discovered marine products do not appear to reflect the biodiversity included within each group, since sponges, cnidarians, bryozoans, and echinoderms each include a comparable number (6,289–11,873) of accepted species (Costello and Chaudhary, 2017; WoRMS Editorial Board, 2020). At the same time, mollusks are one of the richest marine metazoan phyla in terms of biodiversity with 48,803 extant species (WoRMS Editorial Board, 2020) but a poor source of novel marine products (17 new metabolites in 2017, according to Carroll et al., 2020). While sponges and cnidarians, in particular corals, can be cultured on a large-scale to support drug discovery (Duckworth and Battershill, 2003; Leal et al., 2013), the provision of marine invertebrates in sufficient quantities for implementing a battery of activity tests on their natural products is challenging as sustainable supply has always been a bottleneck.

Sponges are prominent candidates for bioproduction-oriented cultivation, due to their simple body plan and regenerative capacity, and their richness in bioactive substances. While sponge farming in the open sea has been proposed (and often accomplished) as an effective strategy to resolve the supply bottleneck and ensure sustainable production of sponge-derived compounds (Duckworth, 2009), it is still limited by the necessity to destructively collect primary material from wild populations in various phases of the cultivation. Little progress has been made toward “closed life cycle cultivation,” i.e., successfully inducing reproduction and recruitment of larvae to the aquaculture (Abdul Wahab et al., 2012). Cell culturing can provide advantages in terms of control of desirable biological characteristics and fine-tuning of production (Sipkema et al., 2005), while recent advances have shown potential for the establishment of sponge cell lines and the development of sustainable processes to produce sponge metabolites (Pérez-López et al., 2014; Conkling et al., 2019).

Since many marine invertebrates host massive associations with microbes, the origin of detected metabolites can be the organism itself, its symbionts (e.g., bacteria) or the food source (e.g., algae) of the metazoan (Loureiro et al., 2018). Hence, metazoans can act as concentrators of natural compounds. Symbionts can produce molecules of biotechnological interest, e.g., enzymes or polyhydroxyalkanoates – PHAs (Bollinger et al., 2018). The antitumor depsipeptide kahalalide F (Shilabin and Hamann, 2011; Salazar et al., 2013), produced by the alga Bryopsis spp. at very low concentrations, was originally identified from the sea slug Elysia rufecens that feed on Bryopsis algae and accumulate this natural compound at 5,000 fold higher concentrations (Hamann et al., 1996). The cultivation of particular metazoan-associated microorganisms is thus becoming a promising opportunity to discover new metabolites (Esteves et al., 2013).

Macroalgae and Seagrasses

Seaweeds, or marine macroalgae gained wide interest in recent years due to the opening of new applications and markets (i.e., biofuel, feed and food supplements, food ingredients, nutraceuticals, and cosmetics), which contributed to the development of aquaculture on several species (Stévant et al., 2017). The term “seaweed” includes macroscopic and multicellular marine red, green, and brown algae. Seaweeds are a rich source of proteins, minerals, iodine, vitamins, non-digestible polysaccharides, and bioactive compounds with potential health benefits. They are present in almost all shallow water habitats. Like phytoplankton, the distribution patterns of seaweed species are controlled by several abiotic environmental factors and biological interactions. Dense beds of large brown seaweeds (i.e., Fucus and Sargassum species) are frequently found together with red and green algae of smaller size. The competition for space between species is strong, and the removal of one species can impact the structure of the whole community. However, invasive species can be valorized for biotechnological applications and in some areas this has showed promising results and has been already used for skincare products (Rotter et al., 2020b). By harvesting invasive seaweeds, the adverse effects on local biodiversity can also be mitigated. In addition to their nutritional value, seaweeds exhibit antimicrobial, immunostimulatory and antioxidant properties (Gupta and Abu-Ghannam, 2011). Due to the growing demand for marine proteins and lipids in the fishfeed industry over the last 20 years, the use of seaweed extracts as prophylactic and therapeutic agents in shellfish and fish aquaculture has become increasingly popular (Vatsos and Rebours, 2015). There are also other macroalgal biomolecules (mainly polysaccharides and carotenoids) that can be used as functional food, nutraceuticals and cosmeceuticals. In 2016 alone, over 32.8 million tons of seaweed were produced from capture and aquaculture worldwide, and the seaweed production increased around 10% annually in the last 3 years, mainly due to an increase in the aquaculture sector (European Commission, 2020). Globally, over 95% of seaweeds are produced through aquaculture (FAO, 2020) with Asian countries being the leaders in this activity, whereas the European seaweed production is primarily based on the harvesting of natural resources (Ferdouse et al., 2018; FAO, 2020), primarily kelp (Laminariales) and in smaller volumes knotted wrack (Ascophyllum nodosum) for production of alginates and seaweed meals or extracts, respectively. Saccharina latissima is presently the species that is cultivated in Europe on a large scale. The yield of the active substances extracted from seaweed is ranging from less than 1% up to 40% of the dry algal mass, depending on various factors, such as target metabolite, species and season (Pereira and Costa-Lotufo, 2012). To increase the value of commercial seaweeds it is important to study the remaining biomass after the extraction of the target substances and find new strategies for its further valorization, for example with the Gelidium sesquipedale and Pterocladiella capillacea biomass remaining after agar extraction (Matos et al., 2020). Understanding the physiological effects of seaweeds or seaweed extracts is a complicated task; similarly to other marine organisms their properties differ depending on the geographical origin and season of harvest. The extraction method of the bioactive components can affect the efficacy of the final extracts. The feasibility of using any of these extracts on a commercial scale needs to be examined to define the extraction cost and reveal how the extracts can be delivered under intensive farming conditions. It is finally worth mentioning that seaweeds can act as habitats for endophytes (Flewelling et al., 2015; Manomi et al., 2015; Mandelare et al., 2018). Endophytes are microorganisms (bacteria and fungi) that live in the plant tissue and in many cases support the plant immunity and growth under extreme or unfavorable conditions and against pathogens and pests (Liarzi and Ezra, 2014; Bacon and White, 2016; Gouda et al., 2016). Endophytes are a rich source of secondary metabolites with potential use in medical, agricultural and industrial applications (Liarzi and Ezra, 2014; Gouda et al., 2016).

Seagrasses are higher plants (angiosperms) that live in marine environments, and along with macroalgae, they play a significant role in coastal ecosystems as they provide food, habitat, and are nursery areas for numerous vertebrates and invertebrates. When harvested sustainably, they can be a potential source to produce bioactive compounds as seagrasses are very resistant to decomposition (Grignon-Dubois and Rezzonico, 2013). Seagrasses are rich in secondary metabolites like polyphenols, flavonoids, and fatty acids, which are the key factors involved in the adaptation to biotic and abiotic environments and for the defense mechanism (Custódio et al., 2016). Many different bioactivities including antioxidant, antiviral and antifungal activities are frequently found in extracts of marine seagrasses such as Halodule uninervis or Posidonia oceanica (Bibi et al., 2018; Benito-González et al., 2019). Seagrasses have potential cytotoxic, antimicrobial, and antifouling activity (Zidorn, 2016; Lamb et al., 2017). Luteolin, diosmetin, and chrysoeriol have been often detected in seagrass tissues (Guan et al., 2017). Zosteric acid from the genus Zostera is one of the most promising natural antifoulants due to its low bioaccumulation and no ecotoxicity effects (Vilas-Boas et al., 2017). Seagrass secondary metabolites are often produced by their associated microorganisms such as fungi or bacteria (Panno et al., 2013; Petersen et al., 2019).

A recent study demonstrated that the presence of seagrasses might contribute to a reduction of 50% in the relative abundance of bacterial pathogens that can cause disease in humans and marine organisms (Lamb et al., 2017). Their preservation can therefore benefit both humans and other organisms in the environment. Achamlale et al. (2009) analyzed the content of rosmarinic acid, a phenolic compound with economic interest, from Zostera noltii and Z. marina beach wrack. Its high amount obtained from seagrass flotsam represents a high value-added potential for this raw material and a real economical potential for industries such as cosmetic and herbal ones. Additionally, chicoric acid, another phenolic compound with demonstrated therapeutic applications and high value on the nutraceutical market, has been found in high amounts in Cymodocea nodosa detrital leaves (Grignon-Dubois and Rezzonico, 2013). Considering the rare occurrence of this compound in the plant kingdom, this makes the abundant beach-cast seagrass biomass of interest for dietary and pharmaceutical applications. However, to maintain the ecological stability, novel approaches need to be designed, such as chemical synthesis of seagrass biomolecules, to prevent the over-harvesting of these protected species.

Microalgae

Microalgae have high growth rates and short generation times and can double their biomass more than once per day in the fastest growing species. Microalgal biomass yields have been reported to be up to 20 kg/m2/year for microalgal cultures (Varshney et al., 2015) and they have the potential of transforming 9–10% of solar energy into biomass with a theoretical yield of about 77 g of biomass/m2/day, which is about 280 ton/ha/year (Melis, 2009; Formighieri et al., 2012), however practical yields in large scale cultivation are much lower (e.g., 23 g/m2/day, Novoveská et al., 2016). As their specific growth rate is 5–10 times higher than those of terrestrial plants, the interest in microalgal biotechnology has increased over the last decades. Microalgal biomass could be considered as genuine “cell factories” for the biological synthesis of bioactive substances used in the production of food, feed, high-value chemicals, bioenergy, and other biotechnological applications (Skjånes et al., 2013; de Morais et al., 2015; de Vera et al., 2018). Large-scale cultivation of marine microalgae is usually performed on land, although near-shore cultivation facilities have been tested (Wiley et al., 2013). Saltwater is pumped from the ocean and introduced into ponds or bioreactors where marine microalgae are cultivated on a larger scale. While land is still needed for microalgae cultivation, this does not have to be the high-quality arable land required for agricultural activities. Microalgal production may utilize wastewater as a nutrient source and/or recycled CO2 from industrial facilities or geothermal power plants (Sayre, 2010; Hawrot-Paw et al., 2020).

Microalgae-based production combines several bioprocesses: cultivation, harvesting, extraction and isolation of active components. Parameters to be controlled in cultures include levels of carbon dioxide, light, oxygen, temperature, pH, and nutrients as they have a crucial effect on biomass activity and productivity. The control of predators in industrial scale microalgae production must also be considered (Rego et al., 2015). The biochemical composition of microalgae can be manipulated by optimizing parameters or by applying specific environmental stress conditions, such as variations in nitrate concentration, light spectrum and intensity or salinity, to induce microalgae to produce a high concentration of target bioactive compounds (Markou and Nerantzis, 2013; Yu X. et al., 2015; Vu et al., 2016; Chokshi et al., 2017; Smerilli et al., 2017).

Microalgal species can produce valuable compounds including antioxidants, enzymes, polymers, lipids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, peptides, vitamins, toxins, and sterols (Moreno-Garcia et al., 2017; Vignesh and Barik, 2019). Microalgae also contain pigments such as chlorophylls, carotenoids, keto-carotenoids, and phycobiliproteins (Zullaikah et al., 2019). Due to their contents, microalgae are considered as a promising feedstock for renewable and sustainable energy, cosmetics, food/feed industry both as whole biomass and as nutritional components, colorants or stabilizing antioxidants and for the synthesis of antimicrobial, antiviral, antibacterial and anticancer drugs (Suganya et al., 2016; Moreno-Garcia et al., 2017). Microalgal biomass can also be used in bio-surfactants, bio-emulsifiers, and bioplastics. Unused biomass can be utilized as bio-fertilizer or it can be digested for biomethane or biohydrogen production (Skjånes et al., 2008, 2013). Among microalgae, marine dinoflagellates are efficient producers of bioactive substances, including biotoxins, some of the largest, most complex and powerful molecules known in nature (Daranas et al., 2001). Biotoxins are of great interest not only due to their negative impact on seafood safety, but also for their potential uses in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications (de Vera et al., 2018). Nonetheless, the supply of these metabolites remains challenging due to their low cellular abundance and the tremendous difficulties involved in large-scale microalgae production (Gallardo-Rodríguez et al., 2012; Molina-Miras et al., 2018).

Currently, the most lucrative large-scale production systems focus on pigments (Novoveská et al., 2019), for example, the production of β-carotene from genus Dunaliella. Nannochloropsis species rich in ω-3 fatty acids are used for eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) production. The cultivation of Haematococcus pluvialis in large quantities for the commercial production of astaxanthin has also attracted worldwide interest, as this compound is considered to be a “super antioxidant” with numerous applications, ranging from human nutraceuticals and cosmetics to aquaculture feed additives and beverages (Kim et al., 2016; Shah et al., 2016). Many other marine microalgae are being investigated as they are genetically adapted to a variety of environmental conditions. The basis of these adaptations and/or acclimation mechanisms are still being uncovered (Mühlroth et al., 2013; Brembu et al., 2017a,b; Mühlroth et al., 2017; Alipanah et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2020). Consequently, several research groups have been bioprospecting new microalgal strains that accumulate bioactive compounds of interest (Nelson et al., 2013; Bohutskyi et al., 2015; Erdoǧan et al., 20166).

Selection and breeding of marine algae lag some 10,000 years behind similar activities for terrestrial plants. Recent developments in the fields of molecular biology, genomics and genetic engineering have enabled the implementation of detailed functional studies and precise editing of traits/properties of marine microalgae (Nymark et al., 2016, 2017; Kroth et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2018; Serif et al., 2018; Slattery et al., 2018; Nymark et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2020). The molecular biology and genomics tool-box for marine microalgae is growing rapidly and we will soon be able to optimize growth, stack properties and transfer complete metabolic pathways from one species to another or from other types of organisms (Noda et al., 2016; Slattery et al., 2018; Nymark et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2020).

Bacteria and Archaea

Marine environments are known to host unique forms of microbial life (Poli et al., 2017). So far, an increasing number of thermophilic, halophilic, alkalophilic, psychrophilic, piezophilic, and polyextremophilic microorganisms (mostly bacteria and archaea) have been isolated. They are capable of proliferating even under extreme conditions as a result of their adaptation strategies involving diverse cellular metabolic mechanisms. As the survival strategies of extremophiles are often novel and unique, these microorganisms produce secondary metabolites or enzymes of biotechnological interest. An example is the enzymes of thermophilic or psychrophilic bacteria that are capable of degrading polysaccharides, proteins and lipids for various applications in the food industry or modifying exopolysaccharides for tissue engineering (Poli et al., 2017). In a recent study, bacteria were isolated across the water column of the CO2-venting Kolumbo submarine volcano (Northeast Santorini, Greece) and the strains originating from the hydrothermally active zone in the crater’s floor (500 m depth) were found to be several-fold more tolerant to acidity, antibiotics and arsenic, compared to the strains isolated from overlying surface waters (Mandalakis et al., 2019).

Many archaea are extremophiles. Enzymes derived from extremophiles (extremozymes) are superior to the traditional catalysts because they can perform industrial processes even under harsh conditions, where conventional proteins are completely denatured (Egorova and Antranikian, 2005). Hyperthermophiles, whose preferred growth temperatures lie above 80°C, consist mostly of archaea. Ideal extremozymes for application in a sustainable biorefinery with lignocellulosic waste material as feedstock should exhibit high specific activities at high temperatures combined with superior thermostability (Krüger et al., 2018). Over 120 genomes of hyperthermophiles have been completely sequenced and are publicly available. Of these, interesting strains belonging to extremophilic archaea that grow at elevated temperatures have been studied in detail such as the genera Pyrococcus, Thermococcus, or Thermotoga found in the marine environment (Krüger et al., 2018). Thermostable archaeal enzymes were reported to have higher stability toward high pressure, detergents, organic solvents and proteolytic degradation (Sana, 2015). However, marine organisms, especially those in biofilms or adapted to live in extreme environments, such as hyperthermophiles, may be recalcitrant to typical lysis methods, hindering protein extraction or modifying the yield of this important step. The hyperthermophile and radiotolerant archaeon Thermococcus gammatolerans, which was isolated about 2,000 m deep in the Pacific Ocean, is a typical example of such a difficult non-model organism (Zivanovic et al., 2009; Hartmann et al., 2014). Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide after cellulose, but its use as a feedstock is limited by the inability to hydrolyze it into simple sugars. Several chitinases have been characterized by extremely thermophilic archaea from marine biotopes (Straub et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019). Recently, the first thermophilic chitinase able to hydrolyze the reducing end of chitin was reported in Thermococcus chitonophagus, potentially expanding the opportunities for using this material (Andronopoulou and Vorgias, 2004; Horiuchi et al., 2016).

Halophilic archaea (haloarchaea) comprise a group of microorganisms from hypersaline environments, such as solar salterns, salt lakes and salt deposits. These microorganisms can synthesize and accumulate both C40 and C50 carotenoids (Giani et al., 2019). The bioactivity of the carotenoid extracts of some haloarchaea indicates their antioxidant, antihemolytic, and anticancer activity (Galasso et al., 2017; Hou and Cui, 2018). The main haloarchaeal carotenoid, bacterioruberin, a C50 carotenoid, presents higher antioxidant capacity when compared to other commercially available carotenoids, such as ß-carotene (Yatsunami et al., 2014).

Some groups of bacteria, like actinobacteria (commonly named actinomycetes) and cyanobacteria, stand out for their capacity to synthesize secondary metabolites. About 660 new natural products from marine bacteria were discovered between 1997 and 2008, with 33 and 39% of them originating from cyanobacteria and actinobacteria (Williams, 2009). Since then, the new hits from marine bacteria exhibited an accelerated increase. The number of marine bacterial natural products identified each year from 2010 to 2012 was approximately 115, from 2013 to 2015 was 161, while it increased to 179 in 2016 (Blunt et al., 2018). It is estimated that 10% of all marine bacteria are actinomycetes (Subramani and Aalbersberg, 2013; Subramani and Sipkema, 2019). With less than 1% of the actinomycetes isolated and identified so far, the marine environment represents a highly promising resource in the field of biodiscovery. Between 2007 and 2017, 177 new actinobacterial species belonging to 29 novel genera and three novel families were described (Subramani and Sipkema, 2019). The Gram-positive actinobacteria are a major chemically prolific source of bioactive metabolites with anticancer, antimicrobial, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory, antibiofilm activities, and antifouling properties, among others (Prieto-Davó et al., 2016; Bauermeister et al., 2018, 2019; Cartuche et al., 2019, 2020; Girão et al., 2019; Pereira et al., 2020). There are several marine-derived actinomycete metabolites described in the literature. Marinone and neomarinone, a pair of sesquiterpene napthoquinones, generated considerable interest in the biosynthesis community because terpenes are extremely rare in bacteria and because the biosynthetic gene cluster could represent a unique mechanism to produce hybrid polyketides through combinatorial biology (Pathirana et al., 1992). Cyclomarin A, a cyclic heptapeptide, also generated interest due to its uniquely modified amino acids and potent anti-inflammatory activity (Renner et al., 1999; Lee and Suh, 2016). The importance of these microorganisms (Potts et al., 2011) is clearly illustrated by the obligate marine actinomycetes from species Salinispora tropica that produce salinosporamide A (marizomib), a unique and highly potent β-lactone-γ-lactam proteasome inhibitor currently in Phase III trials as anticancer agents (Mincer et al., 2002; Feling et al., 2003; Fenical et al., 2009). Marinomycins A-D are also chemically unique bioactive metabolites with potent cytotoxicity toward cancer cell lines, possessing unprecedented polyol-polyene carbon skeletons with unique biological activities evaluated in vivo tumor models (Kwon et al., 2006), and currently being evaluated in clinical trials. Streptomyces sp. are a source of novel anticancer compounds as they exhibit significant in vitro cytotoxicity and pronounced selectivity in a diversity of cancer cell lines (Hughes et al., 2009a,b) and show potent antibiotic activity against several human pathogenic strains (Nam et al., 2010; Jang et al., 2013). However, as non-medical applications require less strict bioassays for certification, a recent trend for Streptomyces-derived antimicrobial compounds is their use in antifouling and antibiofilm products due to their capacity to inhibit the growth of biofilm-forming species (Cheng et al., 2013; Bauermeister et al., 2019; Pereira et al., 2020).

Cyanobacteria are found in a wide variety of environments and are prolific producers of bioactive secondary metabolites. Cyanometabolites are characterized by antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticoagulant, anticancer, antiprotozoal, and antiviral activities. Therefore, cyanobacteria are suitable sources of bioactive compounds for medical, food, and cosmetics applications (Silva et al., 2018; Demay et al., 2019; Kini et al., 2020). To date, 2,031 cyanobacterial metabolites have been described, among which 65% are peptides (Jones et al., 2020). Based on the similarities of their structure and biological activity, they have been organized in 55 unique bioactive classes, such as cyanopeptolins, anabaenopeptins, aerucyclamides, aeruginosines, and microginins (Welker and van Döhren, 2006; Huang and Zimba, 2019; Janssen, 2019). Frequently a single strain will produce a diverse cocktail of peptides (Supplementary Figure 1). The peptides are highly diverse often containing unusual amino acids such as the heptapeptides, the microcystins which contain an unusual hydrophobic amino acid, Adda (2S,3S,8S,9S)-3-amino-9-methoxy-2,6,8-trimethyl-10-phenyldeca-4,6-dienoic acid. Related pentapeptides, nodularins are the only other compounds to contain this amino acid. A high number of cyanopeptides was isolated from cyanobacteria previously classified to the polyphyletic genus Lyngbya. After taxonomic revision, the new genus – Moorea – being the source of more than 40% of all reported marine cyanobacterial natural products, was described. These include curacin, apratoxins, cryptophycins, and dolastatins. A total synthesis of several bioactive cyanopeptides has been successfully elaborated, which opened new opportunities for structure-activity studies and better evaluation of their potential (White et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2014; Yokosaka et al., 2018).

Cyanobacteria synthesize low molecular weight toxins (cyanotoxins), such as microcystins, anatoxins, saxitoxins, β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), and cylindrospermopsin (Janssen, 2019). Amongst cyanotoxins, microcystins are the most geographically widespread and are not restricted to any climatic zone or other geographic range (Welker and van Döhren, 2006; Overlingė et al., 2020). To date, over 279 microcystin variants have been identified and structurally characterized (Spoof and Catherine, 2017). Microcystins are potent inhibitors of type 1 and type 2A protein phosphatases (Bouaïcha et al., 2019). Modified nodularin and microcystins compounds comprise the cytotoxic agents and can be used for the therapy of various diseases (Enke et al., 2020).

Marine firmicutes and proteobacteria have been also shown to produce diverse bioactive compounds, like indole derivatives, alkaloids, polyenes, macrolides, peptides, and terpenoids (Soliev et al., 2011). Firmicutes represent 7% of the bioactive secondary metabolites produced by microorganisms. The genus Bacillus is a relevant representative of the Firmicutes phylum and is a common dweller of the marine environment. It shows high thermal tolerance and rapid growth in liquid media (Stincone and Brandelli, 2020). Species of the genus Bacillus are a prolific source of structurally diverse classes of secondary metabolites and among them, macrolactins, cyclic macrolactones consisting of 24-membered ring lactones, stand out due to their antimicrobial, anticancer, antialgal and antiviral activities (Gustafson et al., 1989; Li et al., 2007; Azumi et al., 2008; Berrue et al., 2009; Mondol et al., 2013).