Abstract

Sepia pharaonis, the pharaoh cuttlefish, is a commercially valuable cuttlefish species across the southeast coast of China and an important marine resource for the world fisheries. Research efforts to develop linkage mapping, or marker-assisted selection have been hampered by the absence of a high-quality reference genome. To address this need, we produced a hybrid reference genome of S. pharaonis using a long-read platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies PromethION) to assemble the genome and short-read, high quality technology (Illumina HiSeq X Ten) to correct for sequencing errors. The genome was assembled into 5,642 scaffolds with a total length of 4.79 Gb and a scaffold N50 of 1.93 Mb. Annotation of the S. pharaonis genome assembly identified a total of 51,541 genes, including 12 copies of the reflectin gene, that enable cuttlefish to control their body coloration. This new reference genome for S. pharaonis provides an essential resource for future studies into the biology, domestication and selective breeding of the species.

Introduction

Sepia pharaonis Ehrenberg, 1,831 (pharaoh cuttlefish) is commonly distributed in the Indo-Pacific from 35°N to 30°S and from 30°E to 140°E and is present in shallow waters to a depth of 100 m (Minton et al., 2001; Al Marzouqi et al., 2009; Anderson et al., 2011). S. pharaonis exhibit behaviors beyond those of ordinary aquatic animals, such as inkjet, camouflage, clustering, sudden changes of color in reaction to excitement and escape (Hanlon et al., 2009; How et al., 2017). This remarkable ability depends on their skin structure and a unique protein, the reflectin, expressed exclusively in cephalopods (Crookes, 2004; Cai T. et al., 2019).

The population is scattered into five groups (Anderson et al., 2011) forming a species complex. Anderson et al. (2011) identifies five S. pharaonis subclades depending of the geographical locations: Western Indian Ocean, North-eastern Australia, Iran, Western Pacific Ocean and Central Indian Ocean. No extensive population genetic study has, to date, been conducted. Population structure, size and extent of the potential species complex is unknown.

Sepia pharaonis is also an important species economically for local fisheries, especially in the Yemeni Sea, Suez Canal, Gulf of Thailand and the northern Indian Ocean (Al Marzouqi et al., 2009). It is also economically important along the southeast coast of China, with an annual catch of approximately 150,000 tonnes. As a giant cuttlefish species, it can grow up to 42 cm in mantle length and 5 kg in weight. S. pharaonis is the largest, most abundant, and exploited species of cuttlefish in the Gulf of Thailand and Andaman Seas, accounting for 16% of the annual offshore cephalopods trawled and 10% of the offshore fixed net catches (Iglesias et al., 2014). S. pharaonis fisheries are in constant increase while the real conservation status of S. pharaonis is still classified as “Data Deficient” (Barratt and Allcock, 2012), only Yemen have an annual fishing quota (Reid et al., 2005). Efforts have been made over the last few years to develop S. pharaonis commercial production methods. S. pharaonis species have been successfully cultivated in China since 2012; the rearing methods include cement pond culture, pond culture and tank culture (Li et al., 2019). The development of farming protocols to breed, feed, ensure good health and welfare of farmed stocks requires a good understanding of the species biology, behavior and adaptations.

The lack of genomic resources coupled with limited understanding of the population structure and size, molecular basis of gene expression and phenotypic variation have limited advancements in environmental conservation and aquaculture-based development. To keep up with global demand and to fight disease and environmental stress, appropriate management of wild stocks and farmed S. pharaonis is necessary to promote the production, sustainability and biosecurity of the industry. An assembled and annotated genome sequence for this species is required to support future selective breeding programs, environmental stress and adaptation research and fundamental genomic and evolutionary studies.

In this study, we report the first draft genome assembly for S. pharaonis using a hybrid assembly technique, with Oxford Nanopore Technologies PromethION, a long-read platform for genome assembly, and Illumina HiSeq X Ten short-read for precise correction of sequence errors.

Materials and Methods

Material Collection

The S. pharaonis used in this work was obtained from a male S. pharaonis (Body length 21.5 cm, Weight 1.205 kg) cultured in a farm located along the coast of Ningbo City, China (29°35′N, 121°59′E). Muscles were collected and instantly frozen in liquid nitrogen and preserved at −80°C. Genomic DNA was extracted using a TIANamp Marine Animal DNA Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Library Construction and Sequencing

High-quality DNA was used for subsequent library preparation and sequencing using both the PromethION and Illumina platforms (Biomarker Technologies Corporation, Beijing, China). To obtain long non-fragmented sequence reads, 15 μg of genomic DNA was sheared and size-selected (30–80 kb) with a BluePippin and a 0.50% agarose Gel cassette (Sage Science, Beverly, MA, United States). The selected fragments were processed using the Ligation Sequencing 1D Kit (Oxford Nanopore, Oxford, United Kingdom) as directed by the manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced using the PromethION DNA sequencer (Oxford Nanopore, Oxford, United Kingdom) for 48 h.

For the estimation and correction of genome assembly, an Illumina DNA paired-end library with an insert size of 350 bp was built in compliance with the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, United States) with paired-end 150 read layout.

RNA Isolation, cDNA Library Construction and Sequencing

The total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity and concentration were measured using a NanoDrop-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). The preparation and sequencing reactions of cDNA library were done by the Biomarker Technology Company (Beijing, China). Briefly, the poly (A) messenger RNA was isolated from the total RNA with oligo (dT) attached magnetic beads (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). Fragmentation was carried out using divalent cations under elevated temperature in Illumina proprietary fragmentation buffer. Double-stranded cDNAs were synthesised and sequencing adaptors were ligated according to the Illumina manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). After purification with AMPureXP beads, the ligated products were amplified to generate high quality cDNA libraries. The cDNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 4000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) with paired-end reads of 150 nucleotides.

De novo Genome Assembly

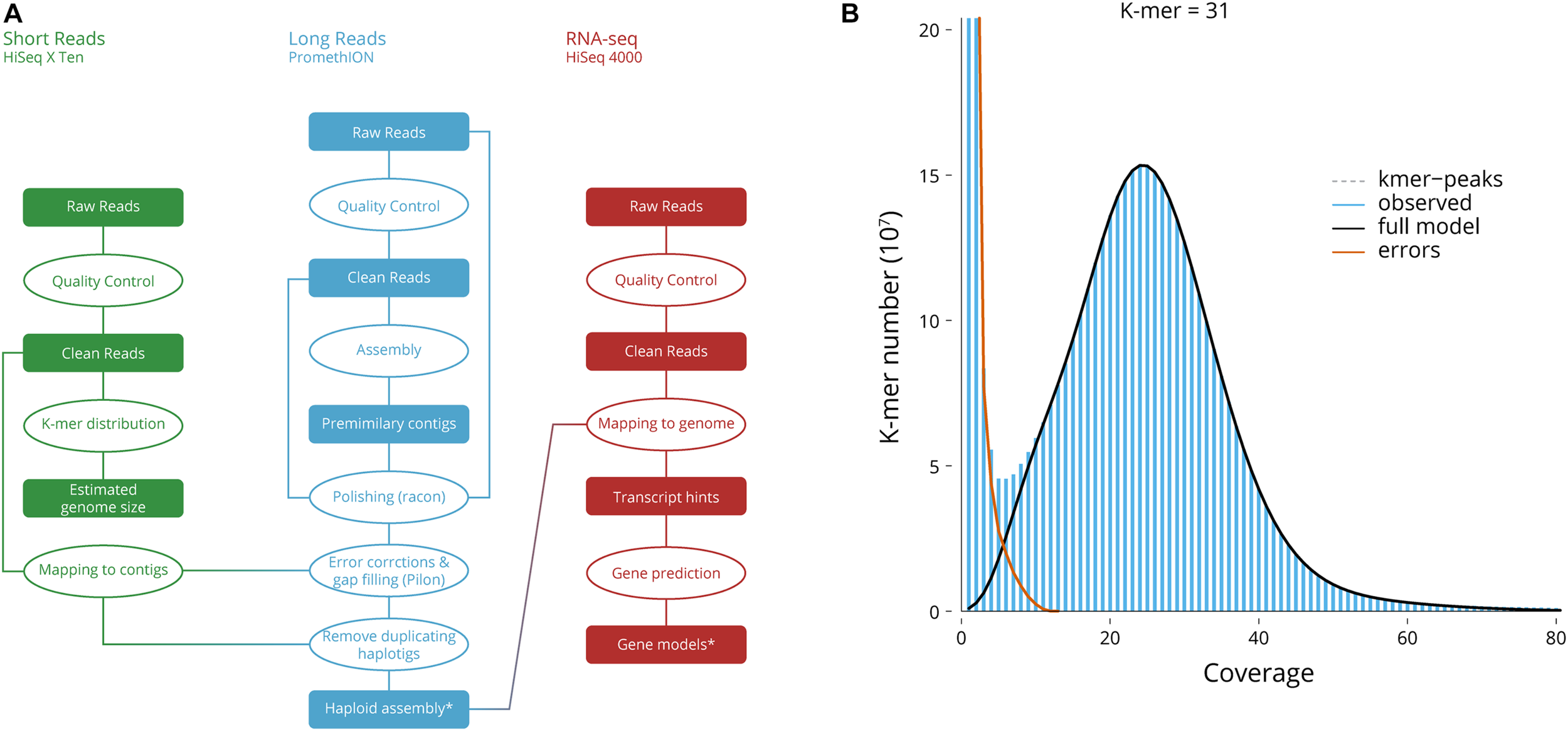

Reads from the two types of sequencing libraries were used independently during assembly stages (Figure 1A). Long-reads were filtered for length (>15,000 nt) and complexity (entropy over 15), while all short reads were filtered for quality (QC > 25), length (150 nt), absence of primers/adaptors and complexity (entropy over 15) using fastp (Chen et al., 2018).

FIGURE 1

Genome assembly. (A) Genome assembly workflow. *Deposited genome sequence. (B) Genome size, the 31-mer distribution used for the estimation of genome size and heterozygosity.

Using Jellyfish (Marçais and Kingsford, 2011), the frequency of 31-mers in the Illumina filtered data was calculated with a 1 bp sliding window (Vurture et al., 2017) to evaluate genome size.

Long-reads were then assembled using wtdbg2 (Ruan and Li, 2020) which uses fuzzy Bruijn graph. As it assembles raw reads without error correction and then creates a consensus from the intermediate assembly outputs, several error corrections, gap closing, and polishing steps have been implemented. The initial output was re-aligned to the long-read and polished using Minimap2 (Li, 2018) and Racon (Vaser et al., 2017), first with filtered reads, to bridge potential gaps, then with the filtered reads to correct for error. Finally, Pilon (Walker et al., 2014) was used to polish and correct for sequencing error using the short-reads. The redundant contigs due to diploidy were reduced by aligning the long reads back to the assembly with Minimap2 (Li, 2018) and by passing the alignment through the Purge Haplotigs pipeline (Roach et al., 2018). This reduced the artifact scaffolds and created the final haploid representation of the genome.

Transcriptomic Data

RNA-seq reads of poor quality (i.e., with an average quality score less than 20) or displaying ambiguous bases or too short and PCR duplicates were discarded using fastp (Chen et al., 2018). Ribosomal RNA was further removed using SortMeRNA (Kopylova et al., 2012) against the Silva version 119 rRNA databases (Quast et al., 2012).

Gene Models

The cleaned RNA-seq reads were pooled and mapped to the genome using the using HiSat2 (Kim et al., 2019). We used a combined approach that integrates ab initio gene prediction and RNA-seq-based prediction to annotate the protein-coding genes in S. pharaonis genome. We used Braker (Hoff et al., 2019) to make de novo gene predictions. We improved the accuracy and sensitivity of the predicted model by applied iterative self-training with transcripts.

Repeat Sequences

The transposable elements have been annotated using a de novo prediction using RepeatModeler (Smit and Hubley, 2017) and LTR-Finder (Stanke et al., 2008). The repetitive sequences yielded from these two programs have been combined into a non-redundant repeat sequence library. With this library, we scanned the S. pharaonis genome using RepeatMasker (Smit and Hubley, 2017).

Evaluating the Completeness of the Genome Assembly and Annotation

The completeness of gene regions was further tested using BUSCO (Simão et al., 2015) with a Metazoa (release 10) benchmark of 954 conserved Metazoa genes.

Annotation and Functional Classification

The predicted coding sequences have been annotated using InterProScan (Jones et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2019), Swiss-Prot release 2020_02 (Bateman et al., 2017) and Pfam release 32.0 database (El-Gebali et al., 2019). For classification, the transcripts were handled as queries using Blast + /BlastP v2.10.0 (Camacho et al., 2009), E-value threshold of 10–5, against Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) release 94.1 (Kanehisa et al., 2019). Gene Ontology (Ashburner et al., 2000) was recovered from the annotations of InterPro, KEGG and SwissProt. Subsequently, the classification was performed using R v4.0.0 (R Core Team, 2020) and the Venn diagram was produced by jvenn (Bardou et al., 2014).

Reflectin

Sepia officinalis Reflectin protein sequences were aligned using Blast + v2.10.0 (Camacho et al., 2009) against both S. pharaonis protein sequences (BlastP, Coverage > 75% query, E-value threshold of 10–20), and S. pharaonis whole genome (using tBlastN, > 75% query, E-value threshold of 10–60). The identified reflectin sequences were aligned using GramAlign (Russell, 2014). A Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree was inferred under the GTR model with gamma-distributed rate variation (Γ) and a proportion of invariable sites (I) using a relaxed (uncorrelated lognormal) molecular clock in RAxML (Stamatakis, 2014).

Code Availability

The versions, settings and parameters of the software used in this work are as follows:

-

Genome assembly: (1) fastp: version 0.20.0, short-reads parameters: -q 25 -y -Y 15 -l 150 -detect_adapter_for_pe; (2) fastp: version 0.20.0, long-reads parameters: -Q -l 15,000 -y -Y 15; (3) wtdbg2: version 2.4, parameters: -x rs -k 23 -p 0 -AS 6 -R -g 4,248 m -rescue-low-cov-edges; (4) wtpoa-cns: version 2.4, default parameters; (5) minimap2: version 2.17, parameters: -x map-ont -r2k; (6) racon: version 1.4.3, default parameters; (7) bwa: version 0.7.17, mode mem, default parameters; (8) pilon: version 1.23, parameters: -diploid -fix all -changes; (9) minimap2: version 2.17, parameters: -ax map-ont -secondary = no; (10) Purge Haplotigs pipeline: version 1.1.1, “cov” mode parameters: -l 5 -m 20 -h 150; (11) BUSCO: version 4.0.2, parameters: -l metazoa_odb10; (12) RepeatModeler: version 1.0.11, parameters: -database cuttlefish; (13) LTR_Finder: version 1.07, default parameters; (14) RepteatMasker: version 4.0.9, parameters: -lib cuttlefish-families.fa; (15) Braker: version 2.1.4, parameters: -gff3 -softmasking; (16) barrnap: version 0.9, parameters: -kingdom euk -reject 0.3.

-

K-mer analysis: (1) jellyfish: version 2.3.0, parameters: -m 31 -C -s 10G; (2) GenomeScope: version 2.0, default parameters.

-

RNA-seq mapping: (1) fastp: version 0.20.0, short-reads parameters: -q 25 -y -Y 15 -l 150 -detect_adapter_for_pe; (2) SortMeRNA: version 3.0.2, parameters: -fastx -num_alignments 1 -aligned -m 64,000; (3) Hisat2: version 2.2.0, parameters: -no-unal -k 20.

-

Mitochondria annotation: (1) MITOS: revision 999, online version, parameters: “Genetic code 5.”

-

Functional annotation: (1) InterProScan: revision 5.44–79.0, parameters: -iprlookup -goterms -pa -f tsv -dp.

-

Phylogenetic analysis: (1) GramAlign: version 3.0, parameters: -C -F 1; (2) RaxML: version 8.2.12, mode PTHREADS-SSE3, parameters: -# 10000 -f a -m GTRGAMMAI.

Results and Discussion

Sequencing Results

After sequencing with the PromethION platform, a total of 14.4 million (338.9 Gb) long-reads were generated and used for the following genome assembly. The N50 length of the sequences was 30,604 nt. The Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform produced 599 million (179.4 Gb) paired-ended short reads (150 nt). The genome size of closely related taxon Euprymna scolopes (also from the Order Sepiida) is estimated to have a C-value of 3.75 pg, or 3.67 Gb (Gregory, 2020); therefore, the average sequencing coverage was 92x and 49x, respectively (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Category | Number/length |

| Total number of long reads | 14,388,299 |

| Total number of bases | 338,903,748,234 |

| N50 length | 30,604 nt |

| Maximum read length | 238,936 nt |

| Coverage | 92x |

| Total number of PE short reads | 599,337,524 |

| Total number of bases | 179,413,175,878 |

| Read length | 150 nt |

| Coverage | 49x |

| Total number of PE short RNA-seq | 144,686,812 |

| Total number of bases | 41,714,818,701 |

| Read length | 150 nt |

| Coverage | 11x |

Sequencing data statistics.

De novo Assembly of the S. pharaonis Genome

Using Jellyfish, the frequency of 31-mers in the Illumina filtered data was determined and followed the theoretical Poisson distribution (Figure 1). The proportion of heterozygosity in the S. pharaonis genome was evaluated as 0.35%, and the genome size was estimated as 4.85 Gb, with a repeat content of 77.3% (Table 2). However, this estimated haploid genome size might be an underestimate, since some portions of the genome (e.g., GC-extreme regions) may have not been sequenced, and/or that repeated sequences may have not been adequately resolved by the k-mer, provided that mollusc genomes are generally known to be repeat rich (Cai H. et al., 2019).

TABLE 2

| Category | Number/length |

| K-mer = 31 | |

| Estimated genome size | 4,248,702,992 nt |

| Estimated repeats | 966,038,761 nt |

| Estimated heterozygosity | 0.35% |

| Largest contig | 11,781,549 nt |

| Total length | 4,785,531,890 nt |

| N50 | 1,926,397 nt |

| GC | 33.2% |

| Mapped | 96.6% |

| Avg. coverage depth | 87.5x |

| Coverage over 10x | 99.8% |

| N’s per 100 kbp | 0 |

| BUSCO recovered | 89.7% |

| Predicted rRNA genes | 30,131 |

| Modeled protein coding genes | 51,541 |

| Modeled protein coding genes (incl. splice variants) | 53,533 |

Statistics of the genome assembly of S. pharaonis.

Long-read assembly using wtdbg2, polished with Racon and sequence-corrected with short-read and Pilon, created an assembled genome of S. pharaonis containing 5,642 contigs with a total length and contig N50 of 4.79 Gb and 1.93 Mb, respectively (Table 2).

To date, two octopod cephalopods, Callistoctopus minor (Kim et al., 2018) and Octopus bimaculoides (Albertin et al., 2015), and three decapod cephalopods, Euprymna scolopes (Belcaid et al., 2019), Architeuthis dux (da Fonseca et al., 2020) and S. pharaonis, are available. Their genomes range from 2.7 to 5.1 Gb (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Genome size | Protein-coding genes | rRNA | Repeat (total) | References | |

| Callistoctopus minor | 5.09 G | 30,010 | n.a. | 44.43% | Kim et al., 2018 |

| Octopus bimaculoides | 2.7 Gb | 33,638 | 907 | 45% | Albertin et al., 2015 |

| Euprymna scolopes | 5.1 Gb | 29,259 | n.a. | 46% | Belcaid et al., 2019 |

| Architeuthis dux | 2.7 Gb | 33,406 | 24,000 | 49.17% | da Fonseca et al., 2020 |

| Sepia pharaonis | 4.8 Gb | 51,541 | 30,131 | 64.89% | This study |

Comparison of size and structure among available cephalopod genomes.

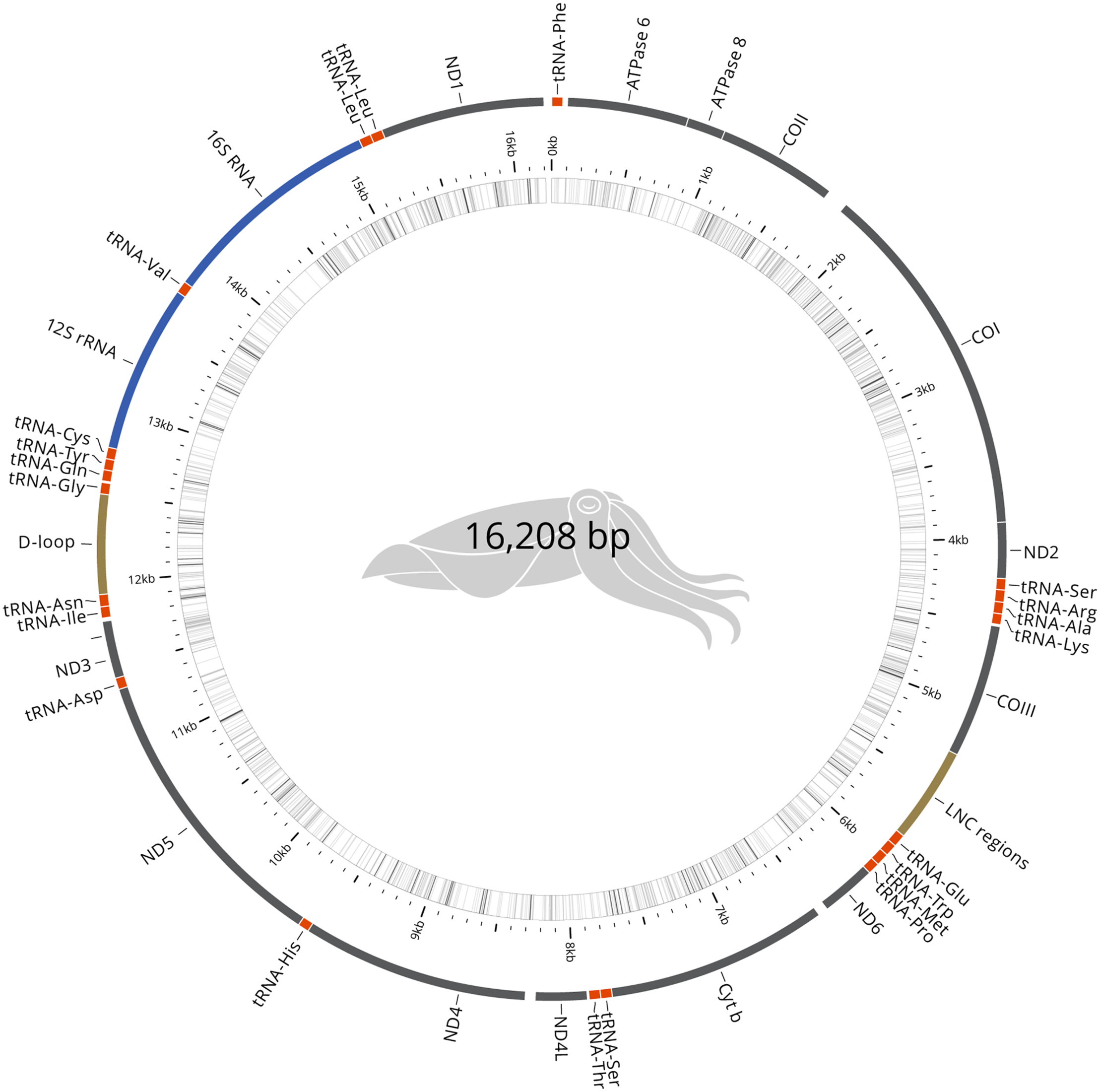

Mitochondrial Genome

The mitochondrial genome was recovered manually from the genome assembly. The mitogenome, 16,208 bp, has been validated for continuity and circularity and annotated using MITOS (Bernt et al., 2013). The complete mitochondrial genome (Figure 2) was compared to the reference S. pharaonis genome (Wang et al., 2014). Only one haplotype was recovered, which is similar at 92% with the reference genome (EBI Accession AP013076).

FIGURE 2

Genome comparisons. S. pharaonis annotated mitochondrial genome.

Repeat Sequences and Gene Models

Transposable elements and repeated sequences have been annotated using RepeatMasker and LTR-Finder. In total, we found 3.11 Gb (64.89%) of repetitive sequences (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Element | Number of elements* | Length occupied | Percentage of sequence |

| SINEs | 218,459 | 40,876,727 bp | 0.85% |

| ALUs | 0 | 0 bp | 0.00% |

| MIRs | 0 | 0 bp | 0.00% |

| LINEs | 3,015,976 | 874,897,165 bp | 18.28% |

| LINE1 | 32,039 | 17,552,571 bp | 0.37% |

| LINE2 | 14,199 | 1,865,319 bp | 0.04% |

| L3/CR1 | 948,295 | 308,456,261 bp | 6.45% |

| LTR elements | 325,691 | 127,098,231 bp | 2.66% |

| ERVL | 0 | 0 bp | 0.00% |

| ERVL-MaLRs | 0 | 0 bp | 0.00% |

| ERV classI | 86,038 | 8,328,047 bp | 0.17% |

| ERV classII | 15,475 | 3,268,511 bp | 0.07% |

| DNA elements | 2,735,236 | 539,157,097 bp | 11.27% |

| hAT-Charlie | 214,530 | 26,969,622 bp | 0.56% |

| TcMar-Tigger | 30,040 | 6,420,004 bp | 0.13% |

| Unclassified | 6,795,072 | 1,238,025,739 bp | 25.87% |

| Small RNAs | 103,607 | 19,661,419 bp | 0.41% |

| Satellites | 3,245 | 488,101 bp | 0.01% |

| Simple sequence repeats (SSR) | 3,743,300 | 227,501,973 bp | 4.75% |

| Low complexity | 297,081 | 37,527,556 bp | 0.78% |

| Total repeats | 3,105,234,008 bp | 64.89% |

Repeat Masker statistics.

*repeats fragmented by insertions or deletions have been counted as one element.

We used a hybrid approach that combines ab initio gene prediction and RNA-seq-based prediction to annotate protein-coding genes in S. pharaonis genome. A total of 51,541 distinct gene models and 30,131 rRNAs (almost all seem to stem from 5S rRNAs) were annotated. Both numbers are consistent with the recently assembled A. dux draft genome (da Fonseca et al., 2020) which reported a genome of 2.7 Gb with 51,225 candidate gene models and more than 24,000 loci derived from 5S rRNA.

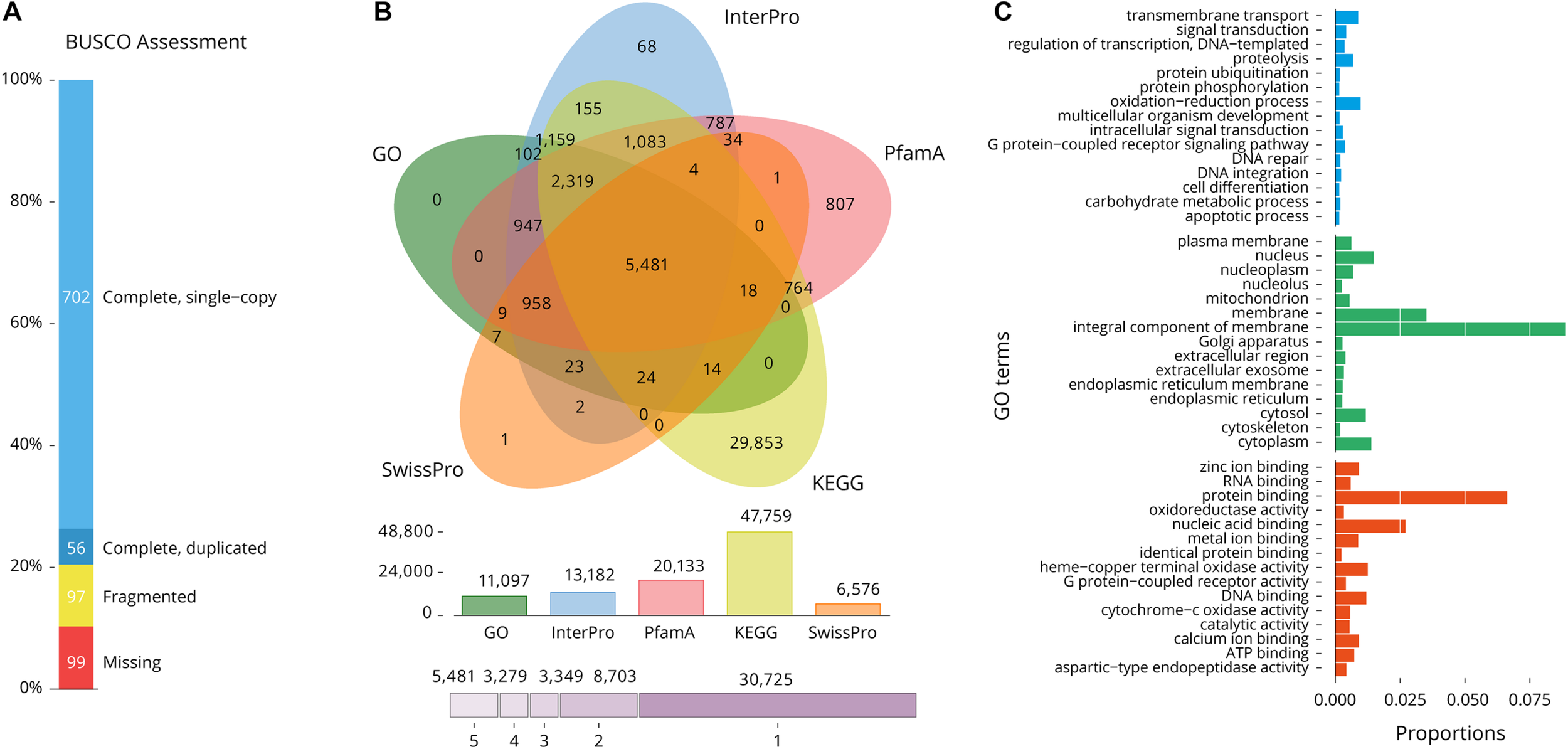

Evaluating the Completeness of the Genome Assembly and Annotation

In order to estimate the quality of the genome assembly, short readings were mapped back to the consensus genome using bwa (Li and Durbin, 2009) and a cumulative mapping of 96.6% rate was reported, suggesting that the assembly contains comprehensive genomic information.

The completeness of gene regions was further assessed using BUSCO (Simão et al., 2015) and a Metazoa (release 10) benchmark of 954 conserved Metazoa genes, of which 79.5% had complete gene coverage (including 5.9% duplicated ones), 10.2% were fragmented and only 10.3% were absent (Figure 3A). These data largely support the high-quality of the S. pharaonis genome assembly.

FIGURE 3

Gene composition and annotation estimations. (A) BUSCO assessment (Metazoa database; number of framework genes 954), 89.7% of the gene were recovered; (B) A five-way Venn diagram. The figure shows the unique and overlapped transcript showing predicted protein sequence similarity with one or more databases (details in Table 4); (C) Level 2 GO annotations using the gene ontology of assembled transcripts [Blue (top): Biological process, Green: Cellular component, Red (bottom): Molecular function].

BlastP similarity searches against SwissProt, Pfam, InterPro, KEGG and GO databases were performed on the predicted proteins. Of the total of 51,541 gene models, 30,724 (59.6%) were annotated in at least one database and 5,481 (10.6%) were annotated in all five databases (Table 5 and Figure 3B). A total of 11,097 predicted transcripts were reported in three major Gene Ontology (GO) classes: “biological processes,” “cellular components” and “molecular functions” (Figure 3C). A total of 20,812 gene models are supported by a least one transcript and two unrelated protein databases, indicative of likely genes, while the remaining 30,729 are supported by only one database and are a more putative set of gene.

TABLE 5

| Database | Number annotated |

| PfamA | 20,133 |

| InterPro* | 13,182 |

| SwissProt | 6,576 |

| KEGG | 47,759 |

| GO | 11,097 |

| All | 5,481 |

| Total | 51,541 |

Summary of annotation results for S. pharaonis gene models using a range of databases.

*InterPro covers 12 databases [CATH-Gene3D, CDD, HAMAP, MobiDBLite, PANTHER, PIRSF, PRINTS, ProDom, PROSITE (patterns and profiles), SFLD, SMART, SUPERFAMILY, and TIGRFAMs].

Comparison Against Other Cephalopods

Only four other cephalopod genomes are available, allowing very little genomic comparisons (Table 3). While all genome sizes range from 2.7 to 5.1 Gb; S. pharaonis tends to have a greater number of protein coding genes and repeats (64.89%). However, the number of rRNAs and, in particular, 5S rRNAs are high but comparable to A. dux. The 3,743,300 potential microsatellite markers (covering 4.75% of genome) identified in the genome will be very useful to decipher the genetic variability and population structure of S. pharaonis subclades.

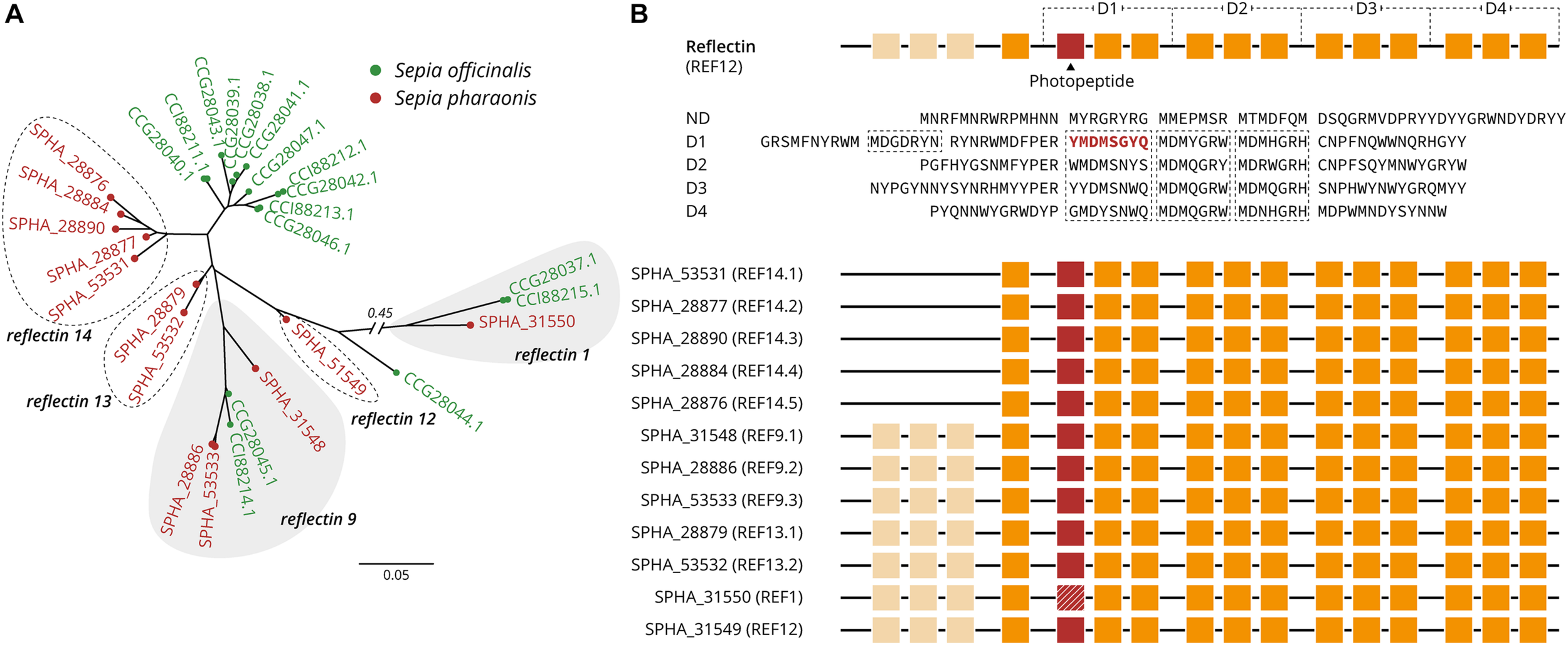

Reflectin

A total of 12 reflectin copies/loci were identified in S. pharaonis genome, including three new classes (Table 6). Compared to S. officinalis, where 16 reflectin genes have been identified, S. pharaonis appears to have only 12 genes. The phylogenetic analysis shows that while reflectin genes 1 and 9 have orthologs in both organisms, the majority of the genes do not have a shared history and had an independent gene expansion/duplication (Figure 4A); S. pharaonis introduces three new class: reflectin 12, 13, and 14. The photopeptide (YMDMSGYQ) is present in all proteins except reflectin 1 where the peptide is degenerated, in both S. pharaonis and S. officinalis (Figure 4B).

TABLE 6

| Locus Tag | Gene ID | Class | Scaffold | Start | Stop |

| SPHA_28890 | REF14.3 | Reflectin 14 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 604,603 | 605,331 |

| SPHA_28876 | REF14.5 | Reflectin 14 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 698,066 | 697,338 |

| SPHA_28884 | REF14.4 | Reflectin 14 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 671,893 | 671,165 |

| SPHA_28879 | REF13.1 | Reflectin 13 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 574,866 | 575,726 |

| SPHA_28877 | REF14.2 | Reflectin 14 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 651,153 | 651,881 |

| SPHA_28886 | REF9.2 | Reflectin 9 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 453,362 | 454,219 |

| SPHA_53531 | REF14.1 | Reflectin 14 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 627,014 | 627,742 |

| SPHA_53532 | REF13.2 | Reflectin 13 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 711,767 | 712,627 |

| SPHA_53533 | REF9.3 | Reflectin 9 | CAHIKZ030001140 | 536,863 | 537,717 |

| SPHA_31548 | REF9.1 | Reflectin 9 | CAHIKZ030001299 | 119,139 | 118,303 |

| SPHA_31549 | REF12 | Reflectin 12 | CAHIKZ030001299 | 157,469 | 156,615 |

| SPHA_31550 | REF1 | Reflectin 1 | CAHIKZ030001299 | 100,899 | 101,753 |

Reflectin genes class and location.

FIGURE 4

S. pharaonis reflectin classification and structures. (A) Gene-tree showing the distribution and grouping S. pharaonis reflectin genes compare with the S. officinalis. Protein accession number are provided between brackets. (B) Schematic diagram of the architecture of reflectin (REF8). The coded amino acid sequence (YMDMSGYQ; here named photopeptide) appears to be a highly conserved motif in the reflectin family. Photopeptide (red boxes, or hashed for a degenerated peptide), core sequences, and domains (D1–D4) are shown in orange (adapted from Guan et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The genome was assembled into 5,642 scaffolds with a total length of 4.79 Gb, a GC content of 33.21% and a scaffold N50 of 1.93 Mb. In addition, we found 3.11 Gb (64.89% of the assembly) of repeat content, 51,541 protein-coding genes, 30,131 rRNAs and a heterozygosity of 0.35%. This high-quality reference genome will serve as an important resource for future studies in fundamental genetics and biology, such as their body coloration, as well as domestication of the species through selective breeding programs. In addition, a transcriptomic data set was created and assembled to enable more refined gene prediction, adding to the currently limited transcriptomic tools available for cephalopods. This work provides new genomic resources for future evolutionary, genomic, phylogenetic and population studies of pharaonic subclades.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw sequencing reads of all libraries are available from EBI/ENA via the accession numbers ERR3418977 (long reads), ERR3431203 (short reads) and ERR4030420, ERR4009535, ERR4009593, ERR4011047, ERR4030425, and ERR4031017 (RNA-seq). The assembled genomes are available in EBI with the accession numbers ERZ1714348 (nuclear genome) and ERZ1300763 (mitochondrial genome), project PRJEB33343.

Ethics statement

This work was approved by the Animal Care and Use committee at the School of Marine Sciences, Ningbo University. Animal handling and collection in this study were carried out following approved guidelines (Fiorito et al., 2015) and regulations (Standardization Administration of China, 2018).

Author contributions

WS, RL, and CW conceived and initialized the project. CW and HM guided the project and grants supporting the work. WS and YZ collected and prepared the sample and performed genome sequencing. MB performed data processing and genome and gene model analysis. WS, MB, and HM drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from Ningbo agricultural major projects (201401C1111001), the United Kingdom Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council China – United Kingdom Partnering Award (BB/S020357/1), CSC Scholarship (201708330421) and K.C. Wong Magana Fund in Ningbo University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Bioinformatic analysis for the study was also partly supported by the MASTS pooling initiative (The Marine Alliance for Science and Technology for Scotland) funded by the Scottish Funding Council (Grant Reference HR09011) and contributing institutions. Open access was supported by the University of Stirling.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Al Marzouqi A. Jayabalan N. Al-Nahdi A. (2009). Biology and stock assessment of the pharaoh cuttlefish, Sepia pharaonis Ehrenberg, 1831 from the Arabian Sea off Oman.Indian J. Fish.56231–239.

2

Albertin C. B. Simakov O. Mitros T. Wang Z. Y. Pungor J. R. Edsinger-Gonzales E. et al (2015). The octopus genome and the evolution of cephalopod neural and morphological novelties.Nature524220–224. 10.1038/nature14668

3

Anderson F. E. Engelke R. Jarrett K. Valinassab T. Mohamed K. S. Asokan P. K. et al (2011). Phylogeny of the Sepia pharaonis species complex (Cephalopoda: Sepiida) based on analyses of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence data.J. Molluscan Stud.7765–75. 10.1093/mollus/eyq034

4

Ashburner M. Ball C. A. Blake J. A. Botstein D. Butler H. Cherry J. M. et al (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology.Nat. Genet.2525–29. 10.1038/75556

5

Bardou P. Mariette J. Escudié F. Djemiel C. Klopp C. (2014). jvenn: an interactive Venn diagram viewer.BMC Bioinformatics15:293. 10.1186/1471-2105-15-293

6

Barratt I. Allcock L. (2012). Sepia Pharaonis. IUCN Red List Threat. Species: e.T162504A904257. 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T162504A904257.en

7

Bateman A. Martin M. J. O’Donovan C. Magrane M. Alpi E. Antunes R. et al (2017). UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase.Nucleic Acids Res.45D158–D169. 10.1093/nar/gkw1099

8

Belcaid M. Casaburi G. McAnulty S. J. Schmidbaur H. Suria A. M. Moriano-Gutierrez S. et al (2019). Symbiotic organs shaped by distinct modes of genome evolution in cephalopods.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.1163030–3035. 10.1073/pnas.1817322116

9

Bernt M. Donath A. Jühling F. Externbrink F. Florentz C. Fritzsch G. et al (2013). MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation.Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.69313–319. 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023

10

Cai H. Li Q. Fang X. Li J. Curtis N. E. Altenburger A. et al (2019). A draft genome assembly of the solar-powered sea slug Elysia chlorotica.Sci. Data6:190022. 10.1038/sdata.2019.22

11

Cai T. Han K. Yang P. Zhu Z. Jiang M. Huang Y. et al (2019). Reconstruction of dynamic and reversible color change using reflectin protein.Sci. Rep.9:5201. 10.1038/s41598-019-41638-8

12

Camacho C. Coulouris G. Avagyan V. Ma N. Papadopoulos J. Bealer K. et al (2009). BLAST+: architecture and applications.BMC Bioinformatics10:421. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421

13

Chen S. Zhou Y. Chen Y. Gu J. (2018). fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor.Bioinformatics34i884–i890. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

14

Crookes W. J. (2004). Reflectins: the unusual proteins of squid reflective tissues.Science303235–238. 10.1126/science.1091288

15

da Fonseca R. R. Couto A. Machado A. M. Brejova B. Albertin C. B. Silva F. et al (2020). A draft genome sequence of the elusive giant squid, Architeuthis dux.Gigascience9:giz152. 10.1093/gigascience/giz152

16

El-Gebali S. Mistry J. Bateman A. Eddy S. R. Luciani A. Potter S. C. et al (2019). The Pfam protein families database in 2019.Nucleic Acids Res.47D427–D432. 10.1093/nar/gky995

17

Fiorito G. Affuso A. Basil J. Cole A. de Girolamo P. D’Angelo L. et al (2015). Guidelines for the care and welfare of cephalopods in research – a consensus based on an initiative by CephRes, FELASA and the Boyd Group.Lab. Anim.491–90. 10.1177/0023677215580006

18

Gregory T. R. (2020). Animal Genome Size Database. Available online at: http://www.genomesize.com/(accessed June 1, 2020).

19

Guan Z. Cai T. Liu Z. Dou Y. Hu X. Zhang P. et al (2017). Origin of the reflectin gene and hierarchical assembly of its protein.Curr. Biol.272833–2842.e6. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.07.061

20

Hanlon R. Chiao C.-C. Mäthger L. Barbosa A. Buresch K. Chubb C. (2009). Cephalopod dynamic camouflage: bridging the continuum between background matching and disruptive coloration.Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.364429–437. 10.1098/rstb.2008.0270

21

Hoff K. J. Lomsadze A. Borodovsky M. Stanke M. (2019). “Whole-genome annotation with BRAKER,” in Gene Prediction: Methods and Protocols, ed.KollmarM. (New York, NY: Springer New York), 65–95. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_5

22

How M. J. Norman M. D. Finn J. Chung W.-S. Marshall N. J. (2017). Dynamic skin patterns in cephalopods.Front. Physiol.8:393. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00393

23

Iglesias J. Villanueva R. Fuentes L. (2014). “Erratum,” in Cephalopod Culture, edsIglesiasJ.FuentesL.VillanuevaR. (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 10.1007/978-94-017-8648-5

24

Jones P. Binns D. Chang H.-Y. Fraser M. Li W. McAnulla C. et al (2014). InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification.Bioinformatics301236–1240. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031

25

Kanehisa M. Sato Y. Furumichi M. Morishima K. Tanabe M. (2019). New approach for understanding genome variations in KEGG.Nucleic Acids Res.47D590–D595. 10.1093/nar/gky962

26

Kim B.-M. Kang S. Ahn D.-H. Jung S.-H. Rhee H. Yoo J. S. et al (2018). The genome of common long-arm octopus Octopus minor.Gigascience7:giy119. 10.1093/gigascience/giy119

27

Kim D. Paggi J. M. Park C. Bennett C. Salzberg S. L. (2019). Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype.Nat. Biotechnol.37907–915. 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4

28

Kopylova E. Noé L. Touzet H. (2012). SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data.Bioinformatics283211–3217. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts611

29

Li H. (2018). Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences.Bioinformatics343094–3100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191

30

Li H. Durbin R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform.Bioinformatics251754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

31

Li J. Jiang X. Zhao C. Peng R. Jiang M. Wang S. (2019). Research on the indoor scale breeding technique of Sepia pharaonis [Chinese].J. Biol.3668–72. 10.3969/j.issn.2095-1736.2019.02.068

32

Marçais G. Kingsford C. (2011). A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers.Bioinformatics27764–770. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011

33

Minton J. W. Walsh L. S. Lee P. G. Forsythe J. W. (2001). First multi-generation culture of the tropical cuttlefish Sepia pharaonis Ehrenberg, 1831.Aquac. Int.9379–392. 10.1023/A:1020535609516

34

Mitchell A. L. Attwood T. K. Babbitt P. C. Blum M. Bork P. Bridge A. et al (2019). InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations.Nucleic Acids Res.47D351–D360. 10.1093/nar/gky1100

35

Quast C. Pruesse E. Yilmaz P. Gerken J. Schweer T. Yarza P. et al (2012). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools.Nucleic Acids Res.41D590–D596. 10.1093/nar/gks1219

36

R Core Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.Vienna: R Found. Stat. Comput.

37

Reid A. Jereb P. Roper C. F. E. (2005). “Family Sepiidae,” in Cephalopods of the World. An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Cephalopod Species Known to Date: Chambered Nautiluses and Sepioids (Nautilidae, Sepiidae, Sepiolidae, Sepiadariidae, Idiosepiidae and Spirulidae), Vol. 1edsJerebP.RoperC. F. E. (Rome: FAO), 54–152.

38

Roach M. J. Schmidt S. A. Borneman A. R. (2018). Purge haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies.BMC Bioinformatics19:460. 10.1186/s12859-018-2485-7

39

Ruan J. Li H. (2020). Fast and accurate long-read assembly with wtdbg2.Nat. Methods17155–158. 10.1038/s41592-019-0669-3

40

Russell D. J. (2014). GramAlign: fast alignment driven by grammar-based phylogeny.Methods Mol. Biol.1079171–189. 10.1007/978-1-62703-646-7_11

41

Simão F. A. Waterhouse R. M. Ioannidis P. Kriventseva E. V. Zdobnov E. M. (2015). BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs.Bioinformatics313210–3212. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351

42

Smit A. F. A. Hubley R. (2017). RepeatModeler. Available online at: http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler/(accessed March 1, 2020).

43

Stamatakis A. (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies.Bioinformatics301312–1313. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033

44

Standardization Administration of China (2018). GB/T35892−2018. Laboratory Animal - Guideline for Ethical Review of Animal Welfare. [Chinese]. Beijing. Available online at: http://www.gb688.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=9BA619057D5C13103622A10FF4BA5D14(accessed October 1, 2019).

45

Stanke M. Diekhans M. Baertsch R. Haussler D. (2008). Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding.Bioinformatics24637–644. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn013

46

Vaser R. Sović I. Nagarajan N. Šikić M. (2017). Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads.Genome Res.27737–746. 10.1101/gr.214270.116

47

Vurture G. W. Sedlazeck F. J. Nattestad M. Underwood C. J. Fang H. Gurtowski J. et al (2017). GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads.Bioinformatics332202–2204. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx153

48

Walker B. J. Abeel T. Shea T. Priest M. Abouelliel A. Sakthikumar S. et al (2014). Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement.PLoS One9:e112963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963

49

Wang W. Guo B. Li J. Qi P. Wu C. (2014). Complete mitochondrial genome of the common cuttlefish Sepia pharaonis (Sepioidea, Sepiidae).Mitochondrial DNA25198–199. 10.3109/19401736.2013.796462

Summary

Keywords

Sepia pharaonis , cephalopod, sequencing, genome, mitochondria, reflectin

Citation

Song W, Li R, Zhao Y, Migaud H, Wang C and Bekaert M (2021) Pharaoh Cuttlefish, Sepia pharaonis, Genome Reveals Unique Reflectin Camouflage Gene Set. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:639670. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.639670

Received

10 December 2020

Accepted

26 January 2021

Published

15 February 2021

Volume

8 - 2021

Edited by

Andrew Stanley Mount, Clemson University, United States

Reviewed by

Simo Njabulo Maduna, Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO), Norway; Daniel Garcia-Souto, University of Vigo, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Song, Li, Zhao, Migaud, Wang and Bekaert.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunlin Wang, wangchunlin@nbu.edu.cnMichaël Bekaert, michael.bekaert@stir.ac.uk

This article was submitted to Marine Molecular Biology and Ecology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.