Abstract

Biomass is defined as organic matter from living organisms represented in all kingdoms. It is recognized to be an excellent source of proteins, polysaccharides and lipids and, as such, embodies a tailored feedstock for new products and processes to apply in green industries. The industrial processes focused on the valorization of terrestrial biomass are well established, but marine sources still represent an untapped resource. Oceans and seas occupy over 70% of the Earth’s surface and are used intensively in worldwide economies through the fishery industry, as logistical routes, for mining ores and exploitation of fossil fuels, among others. All these activities produce waste. The other source of unused biomass derives from the beach wrack or washed-ashore organic material, especially in highly eutrophicated marine ecosystems. The development of high-added-value products from these side streams has been given priority in recent years due to the detection of a broad range of biopolymers, multiple nutrients and functional compounds that could find applications for human consumption or use in livestock/pet food, pharmaceutical and other industries. This review comprises a broad thematic approach in marine waste valorization, addressing the main achievements in marine biotechnology for advancing the circular economy, ranging from bioremediation applications for pollution treatment to energy and valorization for biomedical applications. It also includes a broad overview of the valorization of side streams in three selected case study areas: Norway, Scotland, and the Baltic Sea.

Introduction

Marine biomass represents a biotechnological resource with great diversity in composition and functional properties due to various bioactive compounds, from polyphenols and peptides to polysaccharides. Considering the shortage of terrestrial resources, the constantly increasing and aging population, there is an urgent need to propose alternative sources of food and novel medicine. There is a growing consumer awareness regarding the relationship between diet and health, resulting in elevated demand for new fish products with enhanced nutritional and functional properties (Al Khawli et al., 2019). Moreover, according to the World Health Organization (2021), musculoskeletal conditions are the main contributors that cause disability, thus personalized solutions, methods and materials for tissue regeneration are widely studied. Although often overlooked, marine waste can represent a practical alternative resource to address multiple societal challenges (Chubarenko et al., 2021). This review discusses mainly the state-of-the-art of valorization potential of two sources of marine wastes, (i) marine industries biowaste (focusing on fishery and aquaculture industries), as well as (ii) beach wrack. Indeed, the exploitation of marine biomass and valorization of seafood by-products either directly or by the extraction of biopolymers seems to be a promising alternative, leading to more environmentally sustainable uses of marine resources and higher economic benefits, in line with the circular economy and blue bioeconomy concepts. The realization of such developments is hampered by the lack of appropriate regulatory frames to enable the use of waste and by-products and to ensure the safety, quality, and acceptability of the product.

Beach Wrack

Beach-cast sea wrack or simply beach wrack is an organic material consisting of seagrass or seaweed biomass (Macreadie et al., 2017), various marine invertebrates, as well as human-made litter, mostly plastics (Oliveira et al., 2020), which accumulates on beaches due to the action of waves, tides, and aperiodical water level fluctuations (Suursaar et al., 2014). Despite the natural origin of most of this material and its significant ecological role (Dugan et al., 2003; Orr et al., 2005; Defeo et al., 2009; Nordstrom et al., 2011), beach wrack often becomes a social amenity (Kirkman and Kendrick, 1997; Macreadie et al., 2017) and/or presents environmental issues, if accumulated in excessive amounts (McGwynne et al., 1988; Macreadie et al., 2017). Anthropogenic pressure, such as shoreline reconfiguration (Macreadie et al., 2017), eutrophication (Risén et al., 2017) and climate change (Macreadie et al., 2011), stimulate the accumulation of wrack onshore and multiply the negative impacts on the environment as mentioned above. Likewise, marine eutrophication and climate change do not only affect the accumulation of sea wrack and its degradation, but this may be exacerbated in return by the products of aerobic decomposition as well. It is estimated that the annual global carbon flux from seagrass wrack to the atmosphere is between 1.31 and 19.04 Tg C/yr (Liu et al., 2019). Coordinated collection and valorization of beach wrack could be an intervention to mitigate the eutrophication processes by lowering the nutrient concentrations from the sea as well as lowering the nitrogen to phosphorus ratio. The collection and processing of beach wrack is in line with the European Union (EU) waste law (Regulation, 2008/98/EC), where its recycling is a priority. Importantly, the collection and removal of near-shore beach wrack is associated with estimated costs between 6 and 120 € per ton of disposed wrack or 38 € per meter of beach and an additional 85 € per ton for material drying (Mossbauer et al., 2012; Barbot et al., 2016). Hence, new value chains and business models should be developed to change the perspective of beach wrack from a cost-intensive to a profitable activity. Traditionally, this biomass was either composted (also with fresh-terrestrial green waste, thus contributing to the blue-green innovations) and utilized as a biofertilizer or for biomethane production (Barbot et al., 2016; Weinberger et al., 2020; Borchert et al., 2021). However, there are still unexploited opportunities to maximize its valorization potential in other industries, thus maintaining the circularity of financial and biological resources.

By-Products From Fishery and Aquaculture

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in 2018, about 88% of 179 million tons of total fish production was utilized for direct human consumption, while the remaining 12% was used for non-food purposes (FAO, 2020). Until now, all by-products of fish processing, estimated at up to 75% of the raw material (Rustad et al., 2011), were discarded or used directly as feed, in silage or fertilizers. Such fishery waste includes fish or by-catch species, having low or no commercial value, undersized or damaged commercial species, species of commercial value caught in insufficient amount to warrant a sale, as well as unused fish tissues, including fins, heads, skin and viscera (WRAP, 2012; Caruso, 2016). Nowadays, there is an increasing trend of using these by-products as materials to produce fishmeal and fish oil (currently estimated at 25–35%) (FAO, 2020). Moreover, other aquatic organisms, such as shellfish, seaweeds and aquatic plants, are being increasingly used in experimental projects for the production of food, feed, pharmaceutical and cosmetic products, as well as to produce biomaterials, biofuels and to improve the efficiency of water treatment (Barbot et al., 2016; Nisticò, 2017; Poblete-Castro et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the world’s fisheries discards are still high, exceeding 10%, equivalent to 9.1 million tons of the total production of marine fishery catch (as per 2014 data) and around 5.2 million tons/yr in the European Union (Pérez Roda et al., 2019). In fisheries and aquaculture combined, it is estimated that 35% of the global harvest is either lost or wasted every year (FAO, 2020). Therefore, additional valorization approaches are needed to minimize the amounts of discards and maintain the circularity of resources.

Since January 2019, discards at sea have become an illegal practice in the waters of the EU, increasing the need for a complete valorization of all landed fishery waste, both for large-scale and small fisheries operators. This creates a sociological and environmental imperative for the reduction of these discards and utilization of fishery waste as a potential resource (Rustad et al., 2011; Caruso, 2016). Regulatory frameworks, capacity building, services, infrastructure, as well as physical access to markets are therefore needed to reduce fish loss and waste. The above-mentioned measures can also contribute to improving resource sustainability and food security (FAO, 2020). Furthermore, the need for responsible fisheries and aquaculture practices to help preserve aquatic biodiversity has driven the search for alternative valorization routes for fish waste streams, such as heads, guts, skins, scales, and bones.

General Processing Aspects

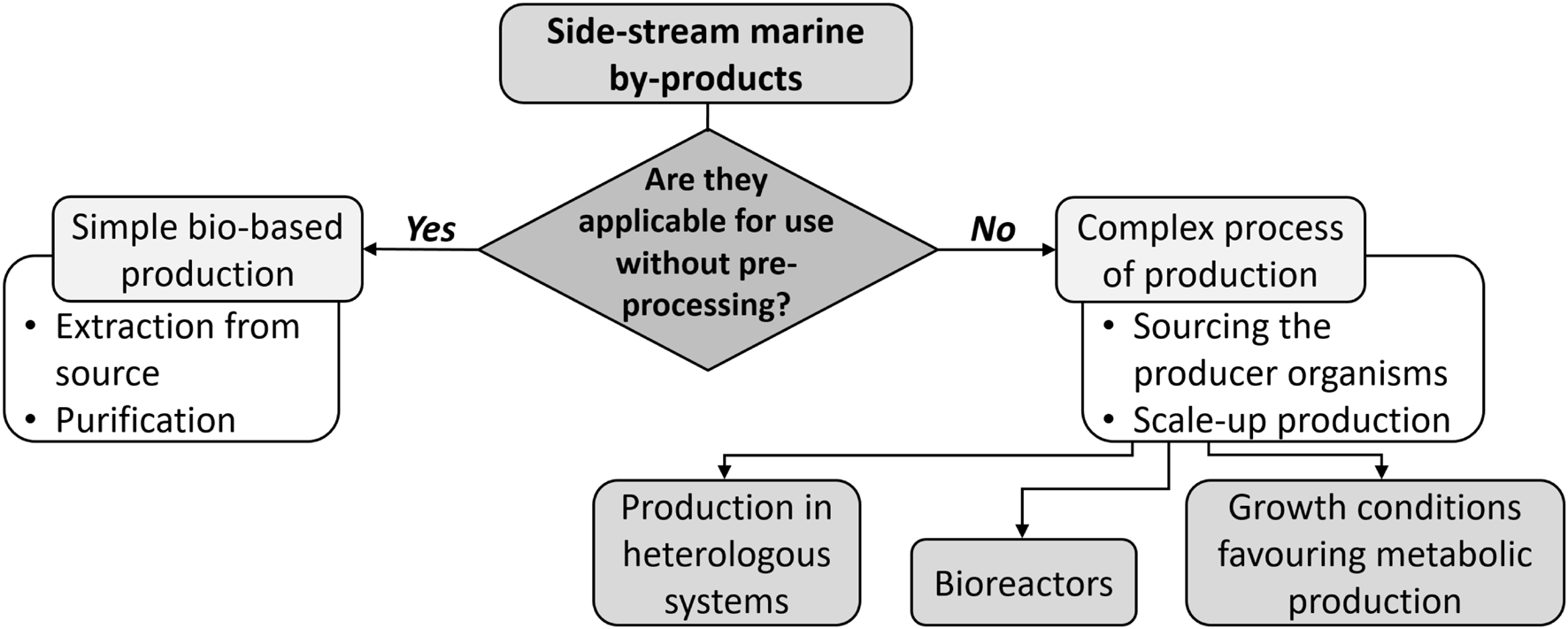

When processing beach wrack or fishery by-products, it is crucial to start their processing as early as possible to minimize physical, chemical, and microbial degradation. To preserve the raw materials for as long as possible, chilling, freezing or acidification using organic acids is performed (Rustad et al., 2011). In general, by-products from side streams or waste can be valorized as they are, using appropriate extraction, purification and downstream processing methods (Figure 1). Alternative methods, such as hydrolysis, ensilaging, fermentation and gelation (surimi production from the fish protein fraction) with food-grade enzymes and/or microorganisms have been optimized for extraction and production of concentrated marine oils, functional protein food ingredients and products, as well as pharmaceutical-grade biopolymers and textiles (Kim, 2013; Lopez-Caballero et al., 2014). These methods are easily used to a wide range of industrial applications in the food, nutraceutical or biomedical sectors. This valorization approach favors the circular economy concept, providing an immediate solution for the reuse or recycling of materials. Biobased production of biopolymers can then be coupled with either sourcing the producer organism and its growth in bioreactors or microbial production in heterologous systems to guarantee a sustainable supply of the biopolymers. For example, hyaluronic acid production was demonstrated in Bacillus subtilis, Lactococcus lactis, and Pichia pastoris (de Oliveira et al., 2016; Badri et al., 2019). However, there are still challenges to successfully produce biopolymers using microorganisms, namely the complex regulatory mechanisms and in vivo polymerization. Nevertheless, fine-tuning of the expression of endogenous or heterologous genes has now advanced using molecular techniques, applying inducible and/or controllable genetic switches, such as CRISPR-Cas tools.

FIGURE 1

The options for utilization of side-stream marine by-products: simple production or combination of bio-based production and growth of producer species or production in heterologous systems, guaranteeing a sustainable sourcing (in case of bio-based production) or a sustainable supply (in case of the complex process of production) of marine biopolymers.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section “Direct valorization of marine waste biomass” describes the alternatives for direct utilization of marine waste biomass. Section “Valorization of marine biopolymers” presents the potential applications of biopolymers from waste biomass, while the overarching European strategies are depicted in Section “Valorization of marine biomass as a European strategy.” Finally, Section “Case studies” describes selected case studies in Norway, Scotland and the Baltic Sea. These Northern European solutions could serve to provide future transfer of knowledge action plans toward Southern Europe and beyond.

Direct Valorization of Marine Waste Biomass

Biosorbents

The basic definition of biosorption is the removal of various contaminants using materials of biological origin (biomass). It is a process typically independent of energy, employing dead or waste biomass of low cost. Most biological waste materials can be efficiently and directly used as readily available biosorbents for removal of organic and inorganic pollutants and radionuclides from e.g., residual waters (de Freitas et al., 2019; Silva et al., 2019; Beni and Esmaeili, 2020; Fawzy and Gomaa, 2020; Magesh et al., 2020; Ubando et al., 2021; Table 1). Biosorption of pollutants on biosorbents usually includes several mechanisms based on the presence of appropriate functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl, amino, phosphate, sulfate, amide, imidazole, thiol, acetamide, etc.), which can interact with target pollutants. The adsorption efficiency can be increased through appropriate physical or chemical treatments (Bulgariu and Bulgariu, 2016; Safarik et al., 2018). The exhausted biosorbents have to be appropriately treated, including regeneration and reuse of biosorbents in multiple biosorption cycles. The totally exhausted biosorbents can then be used as fertilizers for soil remediation, or to form biochar through pyrolysis (Bãdescu et al., 2018). On the contrary, bioaccumulation employs living (micro-) organisms, and appropriate nutrients must be added continuously. Most pollutants are accumulated inside the cell, and thus the possibility of regeneration and repeated use is very limited (Beni and Esmaeili, 2020).

TABLE 1

| Type of marine biomass | Taxonomy | Target pollutant | References |

| Heavy metals | |||

| Algae | Enteromorpha prolifera (magnetically modified) Cladophora sericea | Cobalt, Nickel Antimony | Zhong et al., 2020 Ungureanu et al., 2016 Ungureanu et al., 2016 |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Cadmium | Cheng et al., 2017 | |

| Sargassum sp. | Lead, Copper, Cadmium, Nickel, Zinc, Cobalt, Mercury | Davis et al., 2003; Sheng et al., 2007; He and Chen, 2014; Saldarriaga-Hernandez et al., 2020 | |

| Sargassum cinereum | Lead | Kishore Kumar et al., 2018 | |

| Sargassum filipendula | Silver, Cadmium, Chromium, Copper, Nickel, Zinc | Cardoso et al., 2017 | |

| Padina pavonia | Uranium, Lead | Aytas et al., 2014; He and Chen, 2014 | |

| Pelvetia canaliculata | Nickel | Bhatnagar et al., 2012 | |

| Ulva fasciata | Chromium, Copper | He and Chen, 2014; Shobier et al., 2020 | |

| Ulva intestinalis | Mercury | Fabre et al., 2020 | |

| Ulva lactuca | Mercury, Cadmium | He and Chen, 2014; Fabre et al., 2020 | |

| Ulva rigida | Antimony | Ungureanu et al., 2016 | |

| Ulva rigida | Arsenic, Selenium | Filote et al., 2017 | |

| Crab shell | Clistocoeloma sinensis | Lead, Zinc | Zhou et al., 2016 |

| Cancer pagurus | Mercury | Rae et al., 2009 | |

| Shrimp shell | Farfantepenaeus aztecus | Nickel | Hernández-Estévez and Cristiani-Urbina, 2014 |

| Industrial dyes | |||

| Algae | Bifurcaria bifurcata | Reactive Blue 19, Methylene Blue | Bouzikri et al., 2020 |

| Caulerpa lentillifera | Astrazon® Blue® FGRL, Astrazon Red GTLN | Marungrueng and Pavasant, 2007 | |

| Cymopolia barbata (magnetically modified) Cystoseira barbata (magnetically modified) Euchema spinosum | Safranin O Methylene Blue Methylene Blue | Mullerova et al., 2019 Ozudogru et al., 2016 Mokhtar et al., 2017 | |

| Kappaphycus alverezii | Methylene Blue | Vijayaraghavan et al., 2015 | |

| Nizamuddina zanardini | Acid Black 1 | Esmaeli et al., 2013 | |

| Sargassum sp. | Anionic dyes, Methylene Blue, Malachite Green, Acid Black | Saldarriaga-Hernandez et al., 2020 | |

| Sargassum horneri (magnetically modified) Sargassum swartzii | Acridine orange, Crystal violet, Malachite Green, Methylene Blue, Safranin O Malachite Green | Angelova et al., 2016 Jerold and Sivasubramanian, 2016 | |

| Sargassum wightii | Brilliant Green | Vigneshpriya et al., 2017 | |

| Seagrass Crab shell | Posidonia oceanica (magnetically modified) Penaeus indicus | Acridine Orange, Bismarck Brown Y, Brilliant Green, Crystal Violet, Methylene Blue, Nile Blue A, Safranin O Acid Blue 25 | Safarik et al., 2016a Daneshvar et al., 2014 |

| Inorganic nutrients | |||

| Algae | Gracilaria birdiae | Nitrates, phosphates | Marinho-Soriano et al., 2009 |

| Kappaphycus alverezii | Phosphates | Rathod et al., 2014 | |

| Organic compounds | |||

| Algae | Chlorella vulgaris | Tetracycline | de Godos et al., 2012 |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Progesterone, Norgestrel, Triclosan | Wang et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2014 | |

| Lessonia nigrescens | Sulfamethoxazole | Navarro et al., 2014 | |

| Macrocystis integrifolia | Sulfacetamide | Navarro et al., 2014 | |

| Synechocystis sp. | Paracetamol | Escapa et al., 2017 | |

Potential of marine biomass to act as biosorbents of organic and inorganic pollutants.

Seagrasses, macroalgae, as well as microalgae, have been extensively studied as biosorbents for the removal of various aquatic pollutants (e.g., metal ions, dyes, etc.) (Table 1). The algal cell wall is composed of polysaccharides (e.g., alginate), which have multiple functional groups that act as binding sites for metals and other pollutants. Brown algae, in particular, are very efficient biosorbents for the removal of different metal ions from water due to their unique features, such as high alginate content, higher uptake capacities, and their unlimited availability in the oceans (Davis et al., 2003). The biosorption capacity of algae for specific metals depends on several factors, such as the number of binding sites in the algae, the sites’ accessibility, the availability of the site and affinity between the binding site and the metal (Davis et al., 2003). For example, Saldarriaga-Hernandez et al. (2020) reviewed the bioremediation potential of Sargassum sp. in a circular economy approach. Brown marine macroalgae as natural cation exchangers for the removal of toxic metals were also reviewed (Figueira et al., 2000; Davis et al., 2003; Bilal et al., 2018; Mazur et al., 2018). He and Chen (2014) published a comprehensive review of heavy metal biosorption by algal biomass and discussed materials, performances, chemistry and modeling simulation tools. Biomass from marine macroalgae and seagrasses can be obtained in large quantities at a low price, provided that their harvesting is sustainable and does not affect the ecosystem balance in coastal areas. Different species of marine algae have been used to remove various metal ions, colorants (dyes) and other pollutants from water (Sheng et al., 2007; Bhatnagar et al., 2012; Aytas et al., 2014; Navarro et al., 2014; Rathod et al., 2014; Vijayaraghavan et al., 2015; Jerold and Sivasubramanian, 2016; Ungureanu et al., 2016; Mokhtar et al., 2017; Vigneshpriya et al., 2017; Arumugam et al., 2018; Kishore Kumar et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2019; Bouzikri et al., 2020; Coração et al., 2020; Fabre et al., 2020; Safarik et al., 2020a,b; Shobier et al., 2020; Table 1). Also, waste macroalgae biomass obtained after selected industrial processes can be employed for the same purposes (Safarik et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2018). Several commercially available biosorbents, such as Alga SORBTM, Bio-recovery Systems Inc., and B.V. Sorbex use marine algae. Despite the ease of the algal biosorption process, the technology is not yet recognized, and it requires further research and development efforts at a larger scale using industrial effluents.

Some studies attempted to modify algae to enhance their biosorption (Volesky, 2003), but this has not been considered favorable since it may increase the cost, both for the treatment onside and of the polluted biosorbent afterward, without always improving the sorption capacity. Moreover, active sorption sites are sometimes destroyed due to chemical treatment, resulting in lower biosorption than the untreated algal biosorbent. Despite these discouraging drawbacks, research is still progressing to modify specific properties of biosorbents to increase the biosorption capacities or simplify their recovery. An interesting strategy employs magnetic modification to obtain smart biomaterials, exhibiting several types of responses to an external magnetic field. Such materials can be easily and selectively separated from desired environments using permanent magnets, electromagnets or appropriate magnetic separators (Kanjilal and Bhattacharjee, 2018; Safarik et al., 2018; Hassan et al., 2020). Thus, magnetically responsive marine-derived biosorbents can find significant applications, especially for removing various inorganic and organic pollutants from wastewater. Several procedures can be employed for magnetic modification of marine-based biomass. Usually, magnetic iron oxide nano- and microparticles (Laurent et al., 2008) are used as magnetic labels for marine biomass modification (Safarik et al., 2016b, 2018, 2020a,b). Magnetically modified Sargassum horneri biomass was employed to remove several organic dyes (Angelova et al., 2016), while Sargassum swartzii modified with nanoscale zero-valence iron particles was used for crystal violet biosorption (Jerold et al., 2017). The brown alga Cystoseira barbata coated with magnetite particles was used for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution (Ozudogru et al., 2016), while the tropical marine green calcareous alga Cymopolia barbata, magnetically modified with microwave-synthesized iron oxide nano- and microparticles, was used for the removal of safranin O (Mullerova et al., 2019). The marine seagrass Posidonia oceanica was magnetically modified using three procedures and subsequently used to remove seven water-soluble organic dyes (Safarik et al., 2016a; Table 1).

Biochar is an intensively studied carbon-based material produced by pyrolysis of biomass in the absence of oxygen. The study of Macreadie et al. (2017) provided clear evidence that the conversion of beach wrack to biochar could be a viable environmental solution for dealing with unwanted wrack, offsetting carbon emissions and providing a commercially valuable product for agriculture and wastewater and its sludge treatment. The use of macroalgae biomass for biochar (charcoal) production, with energy co-generation potential, provides a value-driven model to sequester carbon and recycle nutrients (Bird et al., 2011). In specific cases, macroalgal biomass can be used as biochar and magnetic biochar precursor, as shown in several cases using brown or green macroalgae (Jung et al., 2016; Son et al., 2018a, b; Foroutan et al., 2019; Jung et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019). The prepared magnetic biochars were employed as efficient adsorbents of acetylsalicylic acid, water-soluble organic dyes and copper ions (Jung et al., 2019).

Biofuels

Almost 80% of the world’s energy supply is provided by fossil fuels (Balachandar et al., 2013). Energy demands are increasing worldwide due to industrialization, population growth and modernization, leading to the over exploitation of limited available natural fossil fuel reserves (Kumar and Thakur, 2018; Kumar et al., 2020). These fuels represent a significant threat to the environment due to their greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions, which are the main cause of global warming. This stimulates the research on bioenergy production from biomass (Kumar and Thakur, 2018; Karkal and Kudre, 2020). Biofuel and related technologies are considered renewable alternatives to fossil-based fuels due to their sustainable features to overcome the global energy demand (Klavins et al., 2018). As biomass production can be quite expensive to meet the energy needs alone, energy production from waste biomass with the biorefinery approach is alternatively used. Waste biorefineries are attracting significant interest worldwide as sustainable waste management solutions (Khoo et al., 2019). In this case, both required energy needs are met, and a solution to the waste management problem is found in the circular economy context (Tuck et al., 2012; Ahrens et al., 2017).

Production of the first-generation of biofuels is mainly based on the biomass of terrestrial plants, such as corn, soybean, sugar cane, palm oil, among others (Chen et al., 2017; Yu and Tsang, 2017; Shuba and Kifle, 2018). However, their utilization also creates ecosystem damage, water shortage and food vs. fuel debate. Considering the problems related to the first-generation of biofuels, the second- and the third- generations have become alternative options, which are respectively produced from waste materials (plant and agricultural waste, municipal sludge) and microorganisms, without disrupting the environment and natural resources (Kumar et al., 2016, 2018; Shuba and Kifle, 2018).

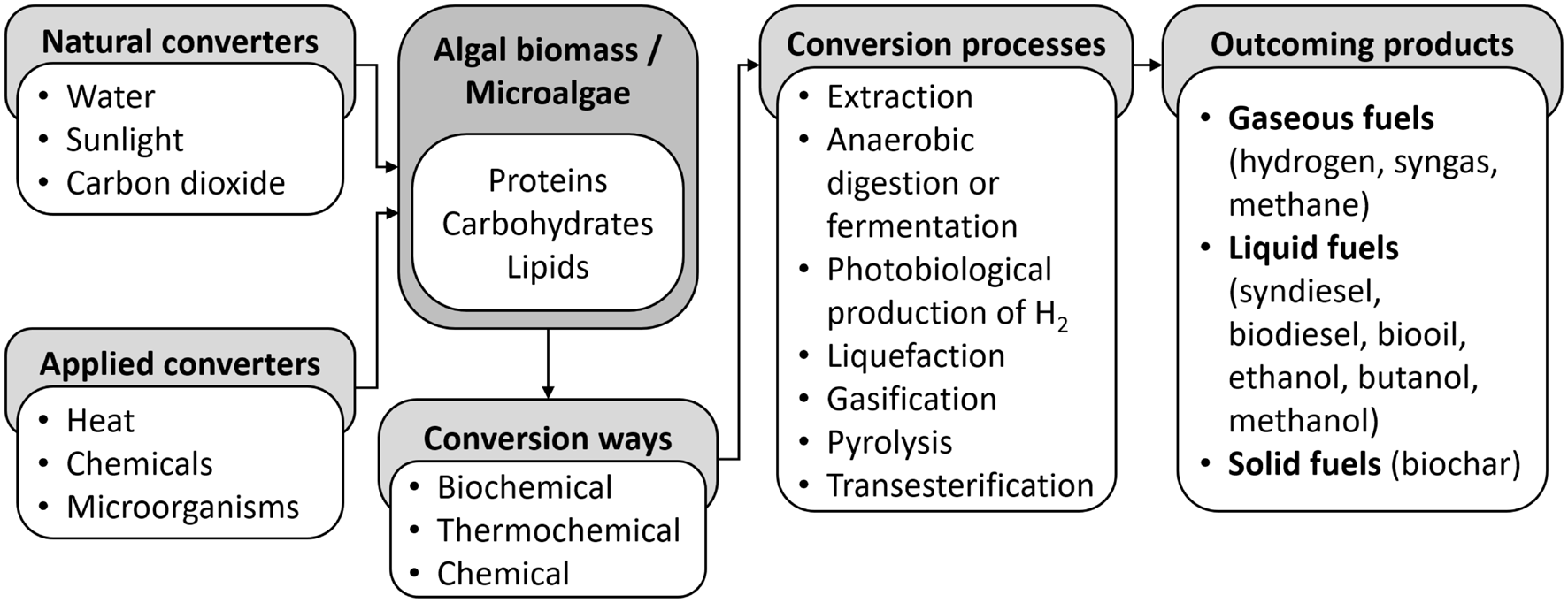

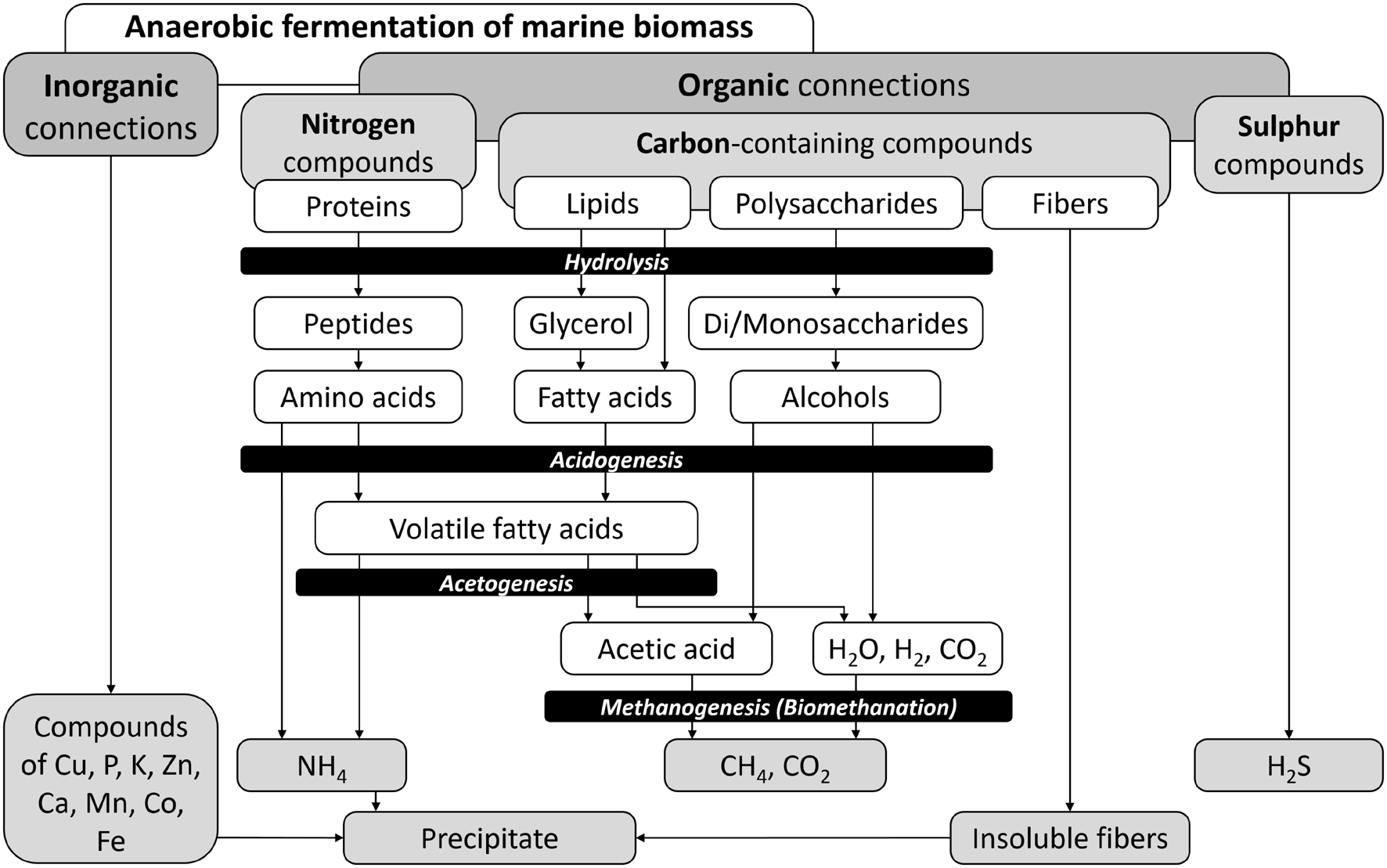

The incorporation of wastewater treatment with microalgae for biofuel production has both environmental and economic benefits. In this process, microalgae are used as biosorbents before biofuel production. Different conversion technologies are used for the production of biofuels (Figure 2), such as biochemical – anaerobic digestion (biogas) and fermentation (bioethanol), and chemical conversion – extraction and transesterification (biodiesel) (Chen et al., 2015; Sikarwar et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2020). In addition, several non-fermentation options for the production of energy from macroalgae are available, including direct combustion (heat energy), gasification (syngas for heat and power generation, liquefaction and production of hydrogen) and pyrolysis (production of liquid bio-oil, syngas and charcoal) (Bruhn et al., 2011; Luo and Zhou, 2012; Rowbotham et al., 2012).

FIGURE 2

Schematic overview of conversion of algal biomass into economically significant products – biofuels, indicating the major converters, conversion ways and processes (Sikarwar et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2020).

Torrefaction, also known as destructive drying and slow pyrolysis, is a mild pyrolytic process that recently received wide attention from the scientific community, as both a method of pre-treatment and upgrade of low-quality fuels (Chew and Doshi, 2011; Chen et al., 2015), as well as for the production of biochar. This process may be organized at scales ranging from extensive industrial facilities down to the individual farms (Lehmann and Joseph, 2009) and even at the domestic level (Whitman and Lehmann, 2009), making it applicable to various socioeconomic situations.

Table 2 summarizes the most important algal biofuels, their production mechanisms and applications. Sustainability is the most important issue for biofuel production. Hence, currently, algae, especially microalgae are the most promising source for biofuels due to their availability and continuous supply. In addition, different biofuel production techniques can be applied depending on the type of algae and biofuel. Thus, the use of algae can still be regarded as a viable option for the next generation of biofuels.

TABLE 2

| Type of biofuel | Content | Process | Extraction protocol | Potential algae | Application | References |

| Biodiesel | Mixture of fatty acid alkyl esters. All the algal lipid contents are extracted from the biomass | Transesterification | These extracted lipid contents are majorly composed of triglycerides, which react with alcohol to produce fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs). | Scenedesmus dimorphus, Nannochloropsis sp., Chlorella vulgaris | Recently FAME is mixed in petro-diesel in a specific proportion (max 20%) and is directly used in the diesel engines without any engine modifications | Chisti, 2007; Adeniyi et al., 2018 |

| Bioethanol | Algae store high amounts of carbohydrates mainly glucose, galactose, and mannitol | Hydrolysis followed by fermentation of sugars | Liquefaction is carried out to increase the efficiency of the produced ethanol. | Eucheuma spinosum | The production of bioethanol for fuel from algae waste could be quite efficient as the industrial waste of Eucheuma spinosum can be converted into bioethanol with an efficiency of 75%. | Chen et al., 2015; Khan et al., 2018; Alfonsín et al., 2019 |

| Biogas | Algal biomass | Methane and carbon dioxide | Anaerobically digested to convert its organic contents into bio-gas. | Ulva lactuca, Chlorella minutissima | Domestic as well as industrial purposes | Cirne et al., 2007; Koçer and Özçimen, 2018 |

| Bio-oil | Algal biomass | Thermal cracking Pyrolysis | Thermal cracking is carried out to extract the lipid contents from the biomass at a very low calorific power range. Pyrolysis is the conversion of algal biomass into bio-oil in the absence of oxygen. | Desmodesmus sp., Gelidium sesquipedale | Conversion into liquid fuel (bio-oil) | Chaiwong et al., 2013; Gang et al., 2017 |

The main algal biofuels and their use.

Fertilizers and Soil Improvers

Beach wrack can be utilized as a biofertilizer for the cultivation and growth of plants. Nowadays, biofertilizers are preferred over chemical fertilizers due to their environmentally friendly and cost-effective nature. Biofertilizers contain microorganisms that can fix nitrogen, solubilize phosphate and promote plant growth. The shells of many bivalves, e.g., blue mussels and oysters, are rich in CaCO3, a mineral currently mined from limestone, representing a widely exploited resource for many industrial applications in agriculture, as a biofilter medium for wastewater treatment, or even cement production (Oso et al., 2011; Yao et al., 2014; Morris et al., 2019; Scialla et al., 2020). In Galicia (Spain), the second global largest aquaculture producer of blue mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis), their shells are commonly used in agriculture for liming the acidified soil (Morris et al., 2019) or for the absorption of heavy metals (e.g., arsenic) to reduce soil pollution (Osorio-López et al., 2014). Marine organic waste, such as seagrasses washed ashore, can also be considered as an alternative and sustainable fertilizer source because of its content of essential macro- and microelements (Bãdescu et al., 2017; Emadodin et al., 2020). Algae contain regulatory macro- and micronutrients, plant hormones such as cytokines, auxins, gibberellins and betaines that can increase plant growth, as well as vitamins, amino acids and metabolites with antibacterial and antifungal activity, which improve productivity. However, the low concentration of phosphorus, the presence of litter or toxic materials in the biomass, especially if the sampling area is subjected to high levels of anthropogenic pressure, can be of concern for using beach wrack as fertilizer (Villares et al., 2016). The salinity of seaweed leachates can be another obstacle; thus, applying it at appropriate rates and leaching of salts before the application can be crucial to obtain an optimal beneficial effect on plant root development. Although already applied in practice, the use of marine algae as biofertilizers is an ongoing field of research. One of the remaining research questions is to understand what role fertilizers from seaweed play in marginal coastal conditions by stimulating the growth of terrestrial plants or for the provision of specific nutrient elements. As an example, beer barley, grown in Scotland, is traditionally fertilized with seaweed and is known for the ability to cope with marginal, high pH soils without inorganic fertilizer addition (Brown et al., 2020).

Biochar has demonstrated applications as a soil enhancer, capable of improving water holding capacity, nutrient status and microbial ecology of many soils (Lehmann et al., 2006; Lehmann and Joseph, 2009; Thies and Rillig, 2012). Bird et al. (2011) showed that macroalgal biochar has properties that provide direct nutrient benefits to soils and stimulate crop productivity and are especially useful for application on acidic soils. In contrast to bioenergy, in which all CO2 that is fixed in the biomass by photosynthesis is returned to the atmosphere quickly as fossil carbon emissions are offset, biochar has the potential for more significant impact on climate through its enhancement of the productivity of infertile soils and its effects on soil GHG fluxes (Woolf et al., 2010).

Feed

For decades, fishery waste has largely been used in fishmeal production (due to its high protein and lipid contents), but this application is no longer considered the only option. Vázquez et al. (2019a, b) described alternative processes to valorize fish discards and produce fish mince, gelatins, oils and fish protein hydrolysates to be used as aquaculture feed ingredients. Wastes generated from the industrial processing of various fish species can also be turned into peptones (water-soluble products of partial hydrolysis of proteins to be used as a liquid medium for growing bacteria) (Vázquez et al., 2020). Mussel meat is rich in protein, lipids, carbohydrates, minerals and carotenoid pigments (Grienke et al., 2014) with potential application as food/feed supplements, preservation agents and enzymes. Seaweeds were traditionally used for animal feeding, either as aquaculture or cattle feed (Araújo et al., 2021). The interest in their use as feed was increased after the 1960s when Norway started producing seaweed meal from kelp (Makkar et al., 2016). Nowadays, they are still used as additional feed for free-range ruminants grazing on beach cast seaweeds in the coastal areas (Bay-Larsen et al., 2016). Brown seaweeds are more often used as feed because of their large size and ease of harvesting (Makkar et al., 2016). Seaweeds can supply the rumen with high amounts of rumen-degradable protein or can be used as a source of digestible bypass protein (Tayyab et al., 2016; Molina-Alcaide et al., 2017). In remote regions, like the Arctic, seaweeds are considered as local protein sources for sustainable sheep farming to replace imported soya (Bay-Larsen et al., 2018). However, the latest research highlights the challenges when applying seaweed proteins in animal feed (Novoa-Garrido et al., 2017; Özkan Gülzari et al., 2019; Emblemsvåg et al., 2020; Koesling et al., 2021; Krogdahl et al., 2021). Some seaweed species, for example, Asparagopsis taxiformis, have antimethanogenic activity on fermentation and can inhibit methanogenesis in the rumen at very low inclusion levels (Machado et al., 2016). Hence, the most appropriate method for processing such seaweeds and feeding to livestock in systems with variable feed quality and content has not been determined yet (Kinley et al., 2016).

Seaweeds tend to accumulate heavy metals (e.g., arsenic) or iodine. Consequently, using polluted beach wrack for feeding could negatively affect animal health. The decomposition and pollution, together with variable and undefined composition, may make beach wrack unsuitable for feed, and considerable sorting and cleaning may be required. Moreover, to have a continuous supply for feeding purposes, industrial cultivation of algae might be considered.

Additional Direct Valorization of Side Streams

Shells can be further exploited as a useful source for the production of biocomposites (Gigante et al., 2020), bio-based insulation material in environmentally responsive building solutions (Martínez-García et al., 2020) or even as a substitute for concrete components to reduce the dependency on conventional natural materials and to decrease the emission of GHG (El Biriane and Barbachi, 2020). Furthermore, seashells can be used as a calcium source to produce bioactive materials in tissue engineering, such as hydroxyapatite, which is the main inorganic phase of the bone (Hart, 2020; Hembrick-Holloman et al., 2020). Finally, direct human patch applications (fish skin grafts) of high ω-3 rich fish skins, like cod or tilapia, are also used for tissue regeneration in chronic or trauma wounds (Lima-Junior et al., 2019).

Valorization of Marine Biopolymers

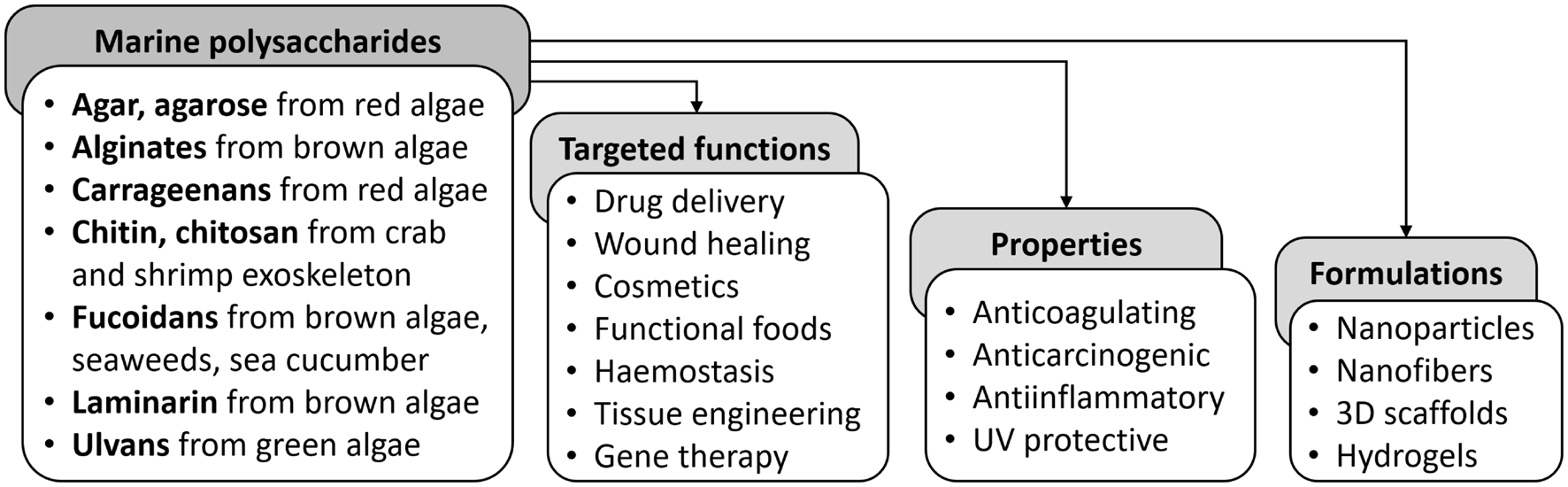

The valorization of side stream biopolymers into useful compounds can have positive environmental, economic, social and technical added values, contributing to the circular economy development. Marine polysaccharides that are present in various marine organisms have the broadest valorization potential. The molecular structure of marine polysaccharides is characterized by long molecular chains of repeating monosaccharide units linked together by glycosidic bonds (Nitta and Numata, 2013). Serving mostly as energy storage and with structural functions, they are derived from various marine resources, including crustaceans and marine algae (Raveendran et al., 2013). Marine polysaccharides are characterized by outstanding chemical and structural diversity, and due to their biocompatibility and biodegradability, they have been used as a material of choice in numerous biomedical applications (Table 3). Exhibiting a wide range of bioactivities (such as anticoagulant, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticancer, immunomodulatory, or antiviral), they are ideal candidates as low-cost, renewable, non-toxic and abundant biomaterials for the development of novel biosystems, such as 3D scaffolds, nanofibers, membranes, hydrogels, and bioinks for tissue engineering, drug delivery and wound dressing applications (Manivasagan et al., 2017).

TABLE 3

| Biopolymer | Structure | Function | Extraction protocol | Application | References |

| Cellulose | Linear homo-polysaccharide of D-glucose units connected by (1,4)-β-glycosidic linkages | The main structural component of the cell walls in higher plants and many seaweeds | Sequential extraction based on three steps: (1) initial Soxhlet extraction to remove lipidic compounds and pigments using organic solvents, (2) mild acid treatment (usually known as bleaching) to remove lignin and some hemicelluloses and (3) basic treatment to eliminate hemicelluloses | Paper industry, food packaging, and pharmaceutical applications | Abdollahi et al., 2013a; Ramamoorthy et al., 2015; Trache et al., 2016; Khalil et al., 2017 |

| Agar | Mixture of the linear polysaccharide agarose and agaropectin | Structural components of the cell walls in several red seaweeds, such as Gelidium and Gracilaria spp. | Application of alkaline pre-treatments, followed by high-temperature and high-pressure extraction treatments, high-temperature filtration and several freeze-thawing cycles. Alternative extraction protocols, based on simplified heating treatments or using ultrasound-assisted methods, have been recently explored for the production of less purified agar-based extracts. These less purified agar-based extracts show similar rheological behavior to the pure agar, but they form softer gels | One of the phycocolloids more widely used in the microbiology field, as well as in the food industry as gelling agent and stabilizing agent for food products | Chemat et al., 2017; Flórez-Fernández et al., 2017; Martínez-Sanz et al., 2019, 2020b |

| Carrageenan | Backbone of disaccharide repeating units of alternating α-1,3-linked D-galactopyranosyl and β-1,4-linked D-galactopyranosyl groups with 3,6-anhydrogalactose residues | Present in the cell walls and the intercellular matrix of some red seaweeds of the class Rhodophyceae | Before extraction, the seaweeds are washed for removal of impurities and in some cases are subjected to pre-treatment with organic solvents for de-colorization. The extraction process involves the application of physical separation methods, followed by alkaline treatments at high temperatures, removal of insoluble residues through filtration and filtrate concentration | Used in various biomedical applications owing to their anticancer, immunomodulatory, anticoagulant and antihyperlipidemic properties. Additionally, they find applications in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries. They are also widely used in the food industry due to their good texturizing properties (thickening and/or gelling capacity) | Fan et al., 2008; Manivasagan et al., 2017; Rahmati et al., 2019 |

| Alginate | Linear anionic polysaccharides, forming a block copolymer of β-1,4-D-mannuronic acid (M-blocks) and α-L-guluronic acid (G-blocks) in which the uronic blocks are organized in a heteropolymeric (alternating M and G residues) or homopolymeric (consecutive M or G residues) arrangement | Found in the cell walls from some brown algae (such as Ascophyllum nodosum, Laminaria spp., Lessonia and Macrocystis, among others) and brown seaweeds of the class Phaeophyceae | Pre-treatment step is usually employed to remove pigments and lipids using various solvents and solvent mixtures. The pre-treated seaweed may be further exposed to vacuum or freeze-drying methods. Seaweeds are then treated with hot aqueous, acidic or salt solutions at increased temperatures and for extended time periods, followed by precipitation | Wound healing and other biomedical applications | Goh et al., 2012; Abdollahi et al., 2013b; Sirviö et al., 2014; Varaprasad et al., 2020 |

| Fucoidans | α-1,3-fucopyranose residues or alternating α-1,3- and linked α-1,4- fucopyranosyls | Structural components in the cell walls, especially those from the families Fucaceae and Laminariaceae | Under acidic conditions, alginate is removed as water-insoluble alginic acid, leaving a rather pure fucoidan extract. Subsequently, the extracted fucoidan is precipitated by the addition of high volumes of alcohol or cationic surfactants, such as hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (Cetavlon®) at low temperatures (4°C) | Due to their non-toxic nature, in conjunction with their antioxidant, antiinflammatory, anticoagulant, antithrombotic and antitumor properties, fucoidans have been used in drug delivery and other biomedical applications | Mautner, 1954; Karunanithi et al., 2016; Dobrinčić et al., 2020; Jönsson et al., 2020 |

| Ulvans | Charged anionic sulphated polysaccharides composed mainly of L-rhamnose, D-xylose, D-glucose, and D-glucuronic and iduronic acids | 8–35% of the dry weight in green seaweeds from the class Ulvales | Extraction with hot water and subsequent precipitation with ethanol | Texture modifiers in the food industry, antioxidant, immunomodulation, antiviral, antihyperlipidemic and anticancer pharmaceutical applications | Lahaye and Robic, 2007; Toskas et al., 2012; Kikionis et al., 2015; Tziveleka et al., 2020 |

| Chitin, chitosan | Chitin: linear polysaccharide consisting of β-1,4- linked 2-amino-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranose. Chitosan: polycationic linear polysaccharide consisting of β-1,4-linked N-acetyl-2 amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose (N-acetylglucosamine) and 2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose (glucosamine) residues | Crustacean exoskeletons, such as crabs and shrimps, also found in squid, corals, sponges, fungi and yeasts | Chitin is commercially extracted chemically or enzymatically from crab and shrimp shells. Chitosan is commercially obtained from chitin involving chemical methods, using corrosive acidic and basic solutions, which have adverse environmental effects | Applications in the biomedical field due to antimicrobial, anticoagulant and wound-healing properties, food packaging | Kumar, 2000; Fan et al., 2008; Ifuku et al., 2009; Danti et al., 2019; Yadav et al., 2019 |

| Laminarin | Low molecular weight β-glucan | Main storage polysaccharide in some brown species (especially those from the Laminariaceae family | Hot water extraction | Natural health product, due to the antitumor, anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, and antioxidant activity | Guiry and Blunden, 1991; Kadam et al., 2015 |

| Proteins – collagen and gelatin | Collagen: three helical α-chains are tightly packed together, forming a final superhelix with a hydrophobic core. Gelatin is a partially hydrolyzed form of collagen | Structural protein derived from fish skin and bones and marine invertebrates | Bioconversion of fish skin may include extraction by acid-alkaline hydrolysis, enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation, using microorganisms or ultrasonic treatment without changing the molecule and enzymatic action | Pharmaceutical/cosmeceutical, nutraceutical and food packaging industries due to their biocompatibility and easy biodegradability. Antihypertensive, antioxidant, antimicrobial, neuroprotective, antihyperglycaemic, and antiaging properties | Liu et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016; León-López et al., 2019 |

The main marine biopolymers and their use.

The major source of marine polysaccharides are algae, with carrageenans mainly present in red algae, alginates and fucoidans in brown algae and ulvans in green algae, ranging from 4 to 76% dry weight (Kraan, 2012). ι-Carrageenan, a sulfated polysaccharide from red seaweed, has been approved by FDA, as Carragelose®, for the treatment of viral and respiratory diseases (Lu et al., 2021). Moreover, many crustacean shells (e.g., those of shrimps) are composed of chitin, a nitrogen-containing linear polysaccharide with wide industrial use, for example, in drug delivery, cosmetics and food. Chitin is regarded as the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature, after cellulose, used for the commercial production of chitosan, a water-soluble derivative obtained by demineralization, deproteinization, and decolourization of chitin (Jiménez-Gómez and Cecilia, 2020).

Novel Materials for Biomedical Applications

The extraordinary biocompatibility, non-antigenicity, chelating ability and bioavailability of marine biopolymers make them suitable materials for biomedical applications. Due to the broad spectrum of reported bioactivities exhibited by marine polysaccharides, they are ideal candidates for novel biomedical systems and have been utilized in various formulations for drug delivery, wound healing and tissue engineering applications. The interest of the biomedical sector in marine polysaccharides is steadily increasing not only because of their natural origin and their unique biological and physicochemical properties, but also due to their stability, safety and high availability at a relatively low cost (Venkatesan et al., 2017; Choi and Ben-Nissan, 2019; Rahmati et al., 2019; Bilal and Iqbal, 2020).

In the pharmaceutical sector, marine polysaccharides have been used as binders, stabilizers, thickeners, matrix materials, emulsifiers, and suspending agents (Figure 3). Over the years, they have been utilized in various formulations, such as gels and hydrogels, micro/nanoparticles (MPs/NPs), films and membranes, nanofibers, as well as 3D porous structures, serving as drug release modifiers, bioadhesives, coatings, wound dressing materials and tissue engineering scaffolds for various biomedical applications (Ruocco et al., 2016; Vanparijs et al., 2017; Joshi et al., 2019).

FIGURE 3

Examples of marine polysaccharides and their applicability for biomedical purposes (Ruocco et al., 2016; Joshi et al., 2019).

Mussel byssus contains high levels of collagen, another widely used raw material (Rodríguez et al., 2017). Collagen extracted from fishery resources is seen as a very promising direction of biotechnological valorization as it is available to a great extent, lacks toxicity and the sociocultural barriers are absent. Mussels easily attach to wet substrates or rocks in wave-battered seashores thanks to adhesive proteins and amino acids (e.g., 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, DOPA). This fact has fueled research on mussel-inspired multifunctional coatings and bioadhesives for use on various surfaces (Lee et al., 2007; Shin et al., 2020). Shell extract of scallop (Pecten maximus) has been shown to stimulate the biosynthesis of extracellular matrix and both type I and type II collagen biosynthesis in primary cells, pointing out their potential in dermatology and cosmetic sectors (Latire et al., 2014).

Gels and Hydrogels

In the biomedical field, gels and hydrogels are recognized as promising biomaterials for drug delivery, tissue engineering, biosensors, self-healing and hemostasis systems due to their highly porous structure, tunable biodegradability and biocompatibility (Venkatesan et al., 2015; Chai et al., 2017). Hydrogels are gels that consist of hydrophilic polymer chains arranged in a 3D cross-linked network. This polymeric network can be controlled and easily manipulated for inclusion and, subsequently, the modified diffusion of various active ingredients (Domalik-Pyzik et al., 2019). Hydrogel scaffolds possess the ability to swell without dissolving in biological fluids; however, due to the fragility of their gel matrix, the need for novel and more stable hydrogel systems is still high (Hoare and Kohane, 2008).

In this respect, carrageenans possess enormous water retaining capacity and gelling properties and have been widely exploited to develop bio-hydrogels (Oun and Rhim, 2017). Alginate hydrogels have been widely used for wound dressing applications and other biomedical applications (Galli et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2018). When cross-linked with natural or synthetic components, they form soft or stiff gels with different physicochemical properties depending on the alginate mannuronic acid:guluronic acid ratio, the material composition and the degree of cross-linking (Gharazi et al., 2018). Chitosan-based hydrogels have been modified with catechol, hydrocaffeic acid, and poly(ethylene glycol) to enhance the bioadhesive, mechanical and antibacterial properties. The developed hydrogel patches and injectable gels can be used as soft tissue engineering materials (Du et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020).

Polymeric Micro- and Nanoparticles

In recent years, various delivery systems have attracted significant attention in the drug delivery sector. Owing to the benefits provided by their small sizes, the application of natural origin MPs/NPs has emerged as a very promising approach for targeted drug delivery. Polymeric MPs/NPs can be fabricated through different methods, such as polyelectrolyte complexation, emulsification and ionic gelation, exhibiting many advantages, such as improved drug solubility, distribution and bioavailability (Chifiriuc and Grumezescu, 2016). Due to their adjustable size and surface characteristics, they can be used as novel carriers for the controlled delivery of active pharmaceutical ingredients with improved pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (Nikam et al., 2014; Manivasagan and Oh, 2016). Several studies have shown the collagen applications as a carrier in different drug delivery systems (Gu et al., 2019), having remarkable abilities and being the focus of extensive research efforts. In particular, collagens from a variety of marine sources have been used to produce micro (diameters between 0.1 and 100 μm) and nano (1–100 nm) bio-based drug delivery systems and are attractive and promising for applications in biomedical and pharmaceutical industries. Marine polysaccharides have been explored to design polymeric MPs/NPs, mainly because of their ionic nature. Oppositely charged polysaccharides can interact with ions, resulting in complex polyelectrolyte structures that can encapsulate various active compounds. The release of the embedded compounds from the complex can be controlled and achieved through various mechanisms, such as charge interactions, ion exchange mechanisms, polymer degradation or dissolution of the polyelectrolyte matrix (Venkatesan et al., 2016).

Numerous studies on the preparation of marine polymer-based nanoparticles have been reported over the years for targeted drug delivery (Bilal and Iqbal, 2020). In a recent report, hybrid alginate/chitosan nanoparticles were investigated for the in vitro release of lovastatin as promising new drug carriers (Thai et al., 2020). Ulvan/lysozyme nanoparticles have exhibited enhanced antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, while at the same time highlighting the potential of ulvan for the preparation of peptide/protein delivery systems (Tziveleka et al., 2018). The use of carrageenan in MPs/NPs-based drug delivery systems for various biomedical applications has also been actively explored. Insulin-loaded lectin-functionalized carboxymethylated κ-carrageenan microparticles were produced by ionic gelation technique, and their potential use as an improved carrier for the oral delivery of insulin was evaluated (Leong et al., 2011). Oral administration of the lectin-functionalized insulin-carrageenan microparticles (diameter 1273 ± 201 μm) in diabetic rats resulted in a sustained release of the insulin in the intestinal region and a prolonged duration of the hypoglycaemic effect, confirming their therapeutic efficacy. κ-Carrageenan extracted from the red algae Eucheuma cottonii was utilized to encapsulate the poorly soluble coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) using the spray drying technique. The CoQ10-κ-carrageenan microparticles were shown to represent an efficient model to increase the water solubility of coenzyme Q10, creating a new water-based product for the food industry to be used either as a main ingredient or as an enriched additive (Chan et al., 2016). Microparticles synthesized using carrageenan with a different number of sulfate groups κ, ι, and λ, were prepared by microemulsion polymerization/crosslinking and were shown to include a wide range of particle sizes (0.5–100 μm). The particles and their modified forms were found to have broad biomedical applicability due to their drug delivery capability, antimicrobial activity, anticancer, high blood clotting effect, good biocompatibility, and cell viability (Sahiner et al., 2017).

Despite being one of the most widespread natural polysaccharides, chitin was for a long time considered as an intractable polymer due to its lack of solubility in common solvents, which limits its processing and practical use (Rinaudo, 2006). Recent studies have mainly focused on chitin NPs (Mincea et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2012) and their applications in different fields. In nature, chitin occurs as micro/nanofibrils that form a composite together with proteins, pigments and calcium carbonate and has a structural role in the exoskeleton of crustaceans and insects (Chen et al., 2008). The unique properties of chitin NPs, such as their renewable and biodegradable characteristics, small size, low density, chemical stability, biological activity, biocompatibility and no cytotoxicity, make them excellent candidates for use in an extensive range of medical applications, nanocomposite fields, water treatment, cosmetics, electronics devices, etc. (Zeng et al., 2012). Several applications of chitin NPs have been developed during the last years in different fields; however, the application in the fields of materials science and health are the most predominant. The addition of nanochitin as a filler in the production of biocomposites enhances the physicochemical properties of the material in addition to its antifungal properties (Salaberria et al., 2014, 2015a, b; Herrera et al., 2017). Its biological activity and non-cytotoxicity have promoted the use of nanochitin for health care and medical applications, such as scaffold and tissue regeneration (Zubillaga et al., 2018; Danti et al., 2019; Smirnova et al., 2019; Zubillaga et al., 2020), drug and cosmetics (Mellou et al., 2019; Coltelli et al., 2020).

Chitosan, obtained from chitin available in the exoskeleton of crustaceans, is a cationic polymer described as an excellent material to design drug delivery systems due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability and non-toxicity. Chitosan NPs have a wide array of applications with excellent oral bioavailability for different biomolecules, such as hydrophobic drugs, nucleic acids, proteins and polysaccharides, retaining their bioactivity, improving stability and enhancing the therapeutic effect (Lang et al., 2020). Moreover, chitosan has mucoadhesive properties and a broad spectrum of bioactivities, namely antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial (Chan et al., 2016; Hafsa et al., 2016), which increase its potential interest for oral drug delivery applications. Chitosan NPs can be produced using different methods, although the most widely described ones are ionotropic gelation and polyelectrolyte complexation. These methods are simple, do not include organic solvents and provide an excellent opportunity to deliver large amounts of nanomaterial into desired products (Divya and Jisha, 2018). Other marine-derived polysaccharides, such as fucoidan, alginate, ulvan, carrageenan, and laminarin, commonly isolated from seaweeds, also have specific and interesting individual properties explored for potential application in drug delivery systems (Venkatesan et al., 2016). These natural anionic polymers can be used to produce NPs of different size, charge and shape for drug delivery applications using methods as emulsion, ionic gelation and polyelectrolyte complexing (Cardoso et al., 2016; Venkatesan et al., 2016). NPs made of marine polysaccharides have been exploited for oral delivery of active pharmaceutical drugs due to their increased stability and resistance to degradation under acidic gastrointestinal conditions leading to improved intestinal drug absorption. Insulin-loaded chitosan-alginate-pentasodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) NPs were produced by ionic gelation. The delivery by nasal administration in rabbits of this hybrid formulation showed enhanced systemic absorption demonstrating its potential in increasing nasal insulin absorption (Goycoolea et al., 2009). Fucoidan-chitosan NPs have been widely described as promising for application as carriers in oral drug delivery systems (Barbosa et al., 2019b). NPs resulting from the encapsulation of curcumin by O-carboxymethyl chitosan-fucoidan were shown to have lower toxicity in mouse fibroblasts when compared with the free form and to be efficiently internalized by Caco-2 cells, demonstrating its potential application for oral drug delivery (Huang et al., 2016). Chitosan-fucoidan NPs containing berberine were developed and shown by in vitro testing in Caco-2 cells/RAW264.7 cells co-culture to restore the barrier function in inflammatory and injured intestinal epithelial (Wu et al., 2014). Also, quercetin loaded fucoidan-chitosan NPs developed for application as a functional food were shown to be stable with controlled drug release under simulated gastrointestinal environment, while maintaining intense antioxidant activity (Barbosa et al., 2019a). Based on the known anticoagulation activity of fucoidan, NPs of chitosan-fucoidan were prepared to encapsulate red ginseng extract and improve its antithrombotic activity and physicochemical properties. Nanoencapsulation improved the ginsenoside solubility and decreased the effect of platelet aggregation in vitro. In vitro studies in the rat model also demonstrated that the NPs caused a significant reduction in thrombus formation when compared with the free red ginseng extract (Kim et al., 2016).

Production of chitosan-fucoidan NPs for pulmonary delivery of the antibiotic chitogentamicin has been described, and results indicate the improvement of antimicrobial efficacy and elimination of systemic toxicity when compared with the intravenous antibiotic administration, with great potential for pneumonia treatment (Huang et al., 2016). Marine-derived drug delivery systems based on chitosan-fucoidan NPs have been recently developed for drug delivery in cancer treatment. Gemcitabine-loaded NPs showed increased toxicity for human breast cancer cells without increasing toxic effects on endothelial cells when compared with free gemcitabine (Oliveira et al., 2018). Piperlongumine is a new class of pro-oxidant drugs with the potential for cancer-specific therapy. Encapsulation of this hydrophobic drug into chitosan-fucoidan NPs increased its solubility and bioavailability, enhancing its anticancer efficacy (Choi et al., 2019).

Studies on the production and application of marine collagen as drug delivery systems for biomedical or as supplements for the food industry are also available in the literature. A MPs protein delivery system was developed using an emulsification-gelation-solvent extraction method and a polymeric matrix of marine collagen extracted from the jellyfish Catostylus tagi. This collagen MPs system (median particle size 9.5 μm) showed promising and versatile results for the controlled release of therapeutic proteins with retained biological activity (Calejo et al., 2012). Collagen from a marine sponge (Porifera, Dictyoceratida) was used to produce a bio-based dressing for topical drug delivery able to absorb the excess wound exudate and at the same time release the drug regulating the healing process (Langasco et al., 2017). Also, collagen extracted from the marine sponge Chondrosia reniformis was used to develop collagen microspheres for dermal delivery of all-trans-retinol (Swatschek et al., 2002). Although the retinol loaded MPs showed a broad size distribution (ranging from 126 ± 2.9 nm to 2179 ± 42 nm), the dermal penetration of retinol-hydrogel-collagen MPs formulations was two-fold higher than when compared to retinol formulations without the MPs. NPs, produced with C. reniformis collagen (size 123 ± 5.5 nm), loaded with 17ß-estradiol-hemihydrate, for application in hormone replacement therapy, were shown to be a promising transdermal drug carrier system of estradiol with enhanced bioavailability, prolonged drug release and increased estradiol absorption compared to a commercial gel (Nicklas et al., 2009).

Marine collagen peptides obtained from Synodontidae fish scales were used to develop alginate NPs, loaded with collagen peptide chelated calcium (diameters approximately 400 nm). This in vivo study demonstrated that the core-shell NPs were able to improve calcium absorption and prevent calcium deficiency in rats treated with this novel biphasic material that could represent an improved calcium supplement for the food industry (Guo et al., 2015).

Polymeric Nanofibers

During the past years, polymeric nanofibers have gained considerable interest due to their unique properties, such as high surface-to-volume area, high and controlled porosity and mechanical flexibility (Kenry and Lim, 2017; Al-Enizi et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2018). Marine biopolymers, due to their biocompatibility and biodegradability, are considered ideal candidates for the development of multifunctional non-wovens. Exhibiting high encapsulation efficacy and architectural analogy to the natural extracellular matrix, they can be easily produced through the electrospinning technique, which is the most widely used method for the production of polymeric nanofibers with tailor-made properties (Teo and Ramakrishna, 2006; Greiner and Wendorff, 2007; Bhardwaj and Kundu, 2010). Various natural and synthetic polymers can be utilized in nanofibrous matrices, incorporating numerous active agents for different biomedical applications.

In most cases, marine polysaccharides, often lacking chain entanglement, have been utilized in combination with other synthetic or natural biopolymers into hybrid polymeric nanofibrous systems that offer the advantageous properties of the combined ingredients (Zhao et al., 2016). Numerous synthetic polymers, such as polycaprolactone, polyethylene oxide, polyvinyl alcohol (Zia et al., 2017), polylactic acid and cellulose acetate, have been used in the development of such hybrid marine polymer-based electrospun patches. Various nanofibrous scaffolds of alginate, fucoidans, ulvan, chitosan and chitin and other biopolymers (e.g., gelatin, cellulose, hyaluronic acid, collagen and their derivatives) have been developed, exhibiting great potential in tissue regeneration, wound healing and controlled drug delivery (Kikionis et al., 2015; Mendes et al., 2017; Augustine et al., 2020). As a recent example, metformin-loaded polycaprolactone/chitosan nanofibrous patches were reported as potential guided bone regeneration membranes (Zhu et al., 2020), while in another work, electrospun alginate nanofibrous dressings loaded with the aqueous extract of Pinus halepensis bark displayed significant in vivo anti-inflammatory activity in mice (Kotroni et al., 2019).

Membranes and Films

While various membranes and films have been developed from marine biopolymers as wound healing or tissue engineering systems, it is alginate that has been most widely used in wound dressings, either alone or combined with other biomaterials. Due to its gelling and fluid-absorption ability, alginate can promote the skin recovery process, maintaining a physiological moist wound environment. It can be easily cross-linked via electrostatic, ionic interactions, covalent-like bonding, redox reactions and coordination with various metals and oppositely charged polysaccharides. The cation interaction of its guluronate blocks with calcium electrolyte into an egg-box-like structure (Goh et al., 2012) has been employed for various wound healing applications. Furthermore, its combination with other positively charged biopolymers, like chitosan in polyelectrolyte forms, has been shown to increase the mechanical stability of the wound dressing materials. In a similar approach, aiming to develop scaffolds for cell cultivation, anionic ulvan and cationic chitosan have been combined to form novel supramolecular structures of stabilized membranes through electrostatic interactions, showing excellent attachment and proliferation of 7F2 osteoblasts (Toskas et al., 2012). As mentioned before, chitosan has been used in many wound dressing and tissue engineering applications, dressing films and membranes (Khan et al., 2020).

3D Structures

In recent years, 3D bioprinting has risen as a versatile tool in regenerative medicine. Therefore, the demand for suitable bioink materials with good printability, biocompatibility and mechanical integrity is apparent. Marine biopolymers, due to their chemical structures and biological functionalities, satisfy most requirements of 3D bioprinting. 3D bioprinting regenerative medicine techniques for human tissue and organ engineering and biofabrication currently apply to 4% chitosan, 10% gelatin, and 26% collagen from a marine origin in bioink formulations for cellular laying/encapsulation (Zhang et al., 2019). Marine polysaccharide hydrogels are naturally derived bioinks, demonstrating low immune response, sufficient biological cues and excellent biocompatibility for tissue engineering applications. Among various marine-origin macromolecules, alginate, carrageenan and chitosan have been widely used as hydrogels in 3D bioprinting for regenerative medicine, such as tissue repair and regeneration during recent years (Zhang et al., 2019). For example, the excellent biocompatibility and the thermogelation properties of κ-carrageenan and alginate have been used to fabricate the cell-laden scaffolds on alginate/carrageenan hydrogels in 3D bioprinting (Kim et al., 2019). In another approach, cells encapsulated within chitosan-based hydrogels demonstrated the printability and applicability of chitosan as a bioink for 3D bioprinting in bone tissue engineering (Demirtaş et al., 2017).

The freeze-drying technique has also been applied for the fabrication of 3D porous scaffolds. Freeze-dried scaffolds can be produced by removing the frozen solvent of a polymeric solution under vacuum, leaving empty spaces (pores) in the formed polymeric scaffold. The architectural characteristics of the produced scaffolds may be tuned by changing the freezing conditions, the polymer solution concentration and the polymer and solvent type (Reys et al., 2017). In this respect, chitosan freeze-dried sponge-like structures were obtained, exhibiting blood absorbing capacity suitable for haemostasis (Kavitha Sankar et al., 2017). Recently, the preparation of ulvan/gelatin hybrid sponge-like scaffolds was reported, exhibiting efficient mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and proliferation for bone tissue engineering applications (Tziveleka et al., 2020).

Novel Materials for Bio-Based Food Packaging

More than 380 million metric tons of plastics are produced worldwide (Ritchie and Roser, 2018). In Europe, 40% of produced plastic is used in packaging. Despite the tremendous benefits of using plastics for packaging, their single-use feature results in an enormous stream of waste with a significantly negative impact on the environment. Synthetic plastics are petroleum-based, hence consuming large amounts of fossil fuels for their production. Moreover, they are not biodegradable and, thus, after disposal, they can accumulate in natural ecosystems for up to several thousands of years. Consequently, more than 5 trillion plastic particles weighing over 250,000 tons are estimated to be floating in Earth’s oceans (Eriksen et al., 2014), posing a major threat to the trophic chain. Only 14% of plastic packaging is currently recycled (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016), and there is a clear consensus that the industry needs to shift to biodegradable plastics from renewable resources (i.e., biopolymers) for a long-term solution to the current situation (Oliveira et al., 2020). Biopolyesters, such as polylactic acid (PLA), polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and thermoplastic starch, can be used for food packaging due to their relatively good processability using industrial techniques such as extrusion or thermoforming. However, their properties are still far from synthetic polymers (especially in terms of thermal resistance, barrier and mechanical performance), and their production costs are too high to compete on the market. Moreover, the raw materials typically used to produce biopolymers originate from land crops, whose primary use is the food sector. In this context, the packaging industry is looking for alternative biopolymers with enhanced properties that can be extracted from cheaper, sustainable resources. Given its abundance and interesting composition, marine biomass has received great intererest is being focused on marine biomass as one of the most promising alternative sources for the extraction of biopolymers for food packaging applications.

The structural polysaccharides found in the cell walls from seaweeds, such as cellulose and phycocolloids (Table 3), have excellent properties, which make them promising candidates for the development of bio-based and sustainable food packaging. Cellulose from land biomass has been widely used to produce food packaging materials and applied as a filler to improve the properties of other biopolymers (Ramamoorthy et al., 2015; Trache et al., 2016). In parallel, several recent studies have reported on the outstanding properties of cellulose extracted from marine biomass (Bettaieb et al., 2015; Khalil et al., 2017; Benito-González et al., 2018; Martínez-Sanz et al., 2020a). One particularly interesting approach, given the circular economy policies that are being promoted by the governing bodies, is the valorization of marine waste biomass. For instance, the residues generated after the accumulation of leaves from the seagrass Posidonia oceanica, found in the Mediterranean shores and the industrial waste produced after extraction of agar from red seaweeds have been used to extract cellulosic fractions with different degrees of purity (Benito-González et al., 2018; Benito-González et al., 2019a; Martínez-Sanz et al., 2020a). These cellulosic fractions can be used to produce films, employing a green method based on the production of aqueous suspensions. Even though the properties of the films may vary depending on the biomass source, commonly, the presence of other non-cellulosic components in the less purified fractions may improve the performance of the films (Benito-González et al., 2019a; Martínez-Sanz et al., 2020a). This is particularly interesting since high-performance cellulose-based packaging films could be produced utilizing simplified and more sustainable methods, thus reducing the production costs and the environmental impact. These cellulosic fractions can also be used as fillers to improve the properties of other biopolymers. One recent work has reported the capacity of cellulosic fractions from P. oceanica to produce biopolymeric films with improved mechanical and barrier performance, as well as with better stability upon storage when incorporated into thermoplastic starch by melt mixing (Benito-González et al., 2019b).

Cellulose from marine biomass can also be used in a particular type of structure known as aerogels. Aerogels are lightweight and highly porous structures, which present excellent sorption capacity and can be used in food packaging as absorbent pads (for fresh products such as meat and fish) and as components for the incorporation and sustained release of bioactive compounds in smart packaging, amongst others. Their high specific surface makes them also ideal materials for catalysis and other advanced applications. Many studies have reported the production of cellulose-based aerogels (Nguyen et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2015; Buchtová et al., 2019); however, the preparation methods are often quite complex, involving several steps (disruption of cellulose crystalline structure, gelation, cellulose regeneration, solvent exchange and a final drying step through supercritical CO2 or freeze-drying). Moreover, due to the highly hydrophilic characteristic of cellulose, hydrophobization treatments are usually required to improve the water-resistance of the aerogels. A simple freeze-drying method has been recently reported to yield high-performance aerogels from cellulosic fractions derived from aquatic biomass, and a very simple strategy has been developed for hydrophobization of cellulosic aerogels, making them stable in aqueous solutions (Fontes-Candia et al., 2019; Benito-González et al., 2020; Martínez-Sanz et al., 2020a,b). These materials display a highly porous structure, especially when using less purified cellulosic fractions, conferring a great sorption capacity when soaked in hydrophilic and/or hydrophobic liquids. This has been exploited to develop bioactive aerogels, incorporating an antioxidant extract that could be released upon contact with meat, thus reducing the oxidation processes taking place upon storage (Fontes-Candia et al., 2019).

Although cellulose is, without a doubt, the most widely exploited marine biomass biopolymer for the development of food packaging, other structural polysaccharides such as phycocolloids are currently being studied. In particular, agar (Sousa and Gonçalves, 2015; Malagurski et al., 2017; Martínez-Sanz et al., 2019), carrageenans (Choi et al., 2005; Vu and Won, 2014; Farhan and Hani, 2017) and alginate (Abdollahi et al., 2013a, b; Sirviö et al., 2014; Senturk Parreidt et al., 2018) have excellent potential for the production of food packaging films with interesting properties. The main disadvantages of phycocolloid films are their excessive rigidity (which is counteracted with the addition of plasticizing agents) and their low resistance to high relative humidity conditions (which can be improved by incorporating more hydrophobic fillers). Interestingly, less purified agar-based extracts have been shown to overcome these issues due to the positive effect of other compounds remaining from the native seaweeds, such as proteins and minerals (Martínez-Sanz et al., 2019). These phycocolloids can be used to produce porous aerogels (Quignard et al., 2008; Gonçalves et al., 2016; Manzocco et al., 2017), but similarly to cellulose, complex preparation methods are often required. Further research needs to be carried out to look for alternative manufacturing processes and to identify strategies to adjust the properties of the obtained aerogels to the requirements of different food packaging applications.

Even though there are no studies reported on marine collagen as an alternative food packaging material, there are some studies on bovine/porcine collagen that has already been tested to produce edible films for protection and extension of food products, such as sausages casings (Suurs and Barbut, 2020). Moreover, the addition of chitosan to gelatin films of cuttlefish skin improves the thermal stability of the polymer network and increases the antioxidant and antimicrobial activity against some Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, which is a useful property in packaging production (Hajji et al., 2021). However, there are some restrains in a broad application of collagen as packaging material, as it is sensitive to moisture. Gelatin based packaging coatings have also been explored, but various additives (lysozyme, chitosan, chitin, essential oils, among others) need to be applied to achieve the desired properties (antimicrobial, antioxidative) (Chawla et al., 2021).

Use in the Leather Industry

Among the solutions for reducing fish waste, one potential option is utilizing fish skin to produce exotic leathers for accessories such as bags, gloves, or shoes. The valorization of any animal skin into leather materials involves tanning, a process that alters the skin protein structure, transforming the biodegradable skin into durable and flexible leather. Saranya et al. (2020) explored the potential of fish waste to produce fish oil, which could be used as a fat-liquoring agent in leather processing, and the results were better compared to those of a traditional commercial fat-liquoring agent. Thus, the fish oil fat-liquor produced from fish waste can be regarded as an eco-friendly alternative to lubricate leather as it allows to substantially reduce the sludge disposal issues in the tannery industry and reduce waste in the fisheries sector. To satisfy the trends for greener production, bio-tanning processes are being sought that replace chromium with plant-based tannins or the re-use of tanning floats, which can reduce the water consumption in the process up to 90%. An example of successful valorization of fish skin into leather is the Moroccan company SeaSkin, using a plant-based coloring system and a dry tanning process, thus reducing 95% of water in the process. Another valorization example is the use of salmon skin in leather straps for watches by the Norwegian company Berg Watches, in collaboration with the Icelandic Nordic Fishleather.

Use in Food/Feed Industries

Proteins are a highly valuable resource, present in several raw materials from plant and animal origin, available in different amounts and with the primary dietary function to provide essential amino acids and tissue building material to the human and animal body. Proteins of marine origin demonstrated higher quality due to high amounts of all essential amino acids (Abdul-Hamid et al., 2002; Prihanto et al., 2019). Several studies have also proven that the quality, digestibility and bioavailability of the essential amino acids in marine protein concentrates increase after food-grade hydrolysis processing (Faber et al., 2010; Kim, 2013). Marine protein hydrolysates can also contribute the necessary amounts of bioactive peptides with antioxidative, antihypertensive, metal-chelating, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory properties to the human diet (Kim, 2013; Abdelhedi et al., 2018; Ediriweera et al., 2019).

Marine polysaccharides (e.g., alginates, carrageenans, agar), as well as gelatin, are used in food and feed industries as gelling agents, stabilizers and/or emulsifiers. Their addition can change the product’s viscosity, which impacts the transport of volatile components and affects flavor release (Liu et al., 2015). As an excellent source of proteins, lipids, vitamins and minerals, by-products as fish skin, viscera and blood, as well as crustacean and bivalve shells, are used in the pharmaceutical and agriculture industry and innovative food processing technologies (Beaulieu et al., 2013).