Abstract

Plastic debris has been accumulating in the marine realm since the start of plastic mass production in the 1950s. Due to the adverse effects on ocean life, the fate of plastics in the marine environment is an increasingly important environmental issue. Microbial degradation, in addition to weathering, has been identified as a potentially relevant breakdown route for marine plastic debris. Although many studies have focused on microbial colonization and the potential role of microorganisms in breaking down marine plastic debris, little is known about fungi-plastic interactions. Marine fungi are a generally understudied group of microorganisms but the ability of terrestrial and lacustrine fungal taxa to metabolize recalcitrant compounds, pollutants, and some plastic types (e.g., lignin, solvents, pesticides, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, polyurethane, and polyethylene) indicates that marine fungi could be important degraders of complex organic matter in the marine realm, too. Indeed, recent studies demonstrated that some fungal strains from the ocean, such as Zalerion maritimum have the ability to degrade polyethylene. This mini-review summarizes the available information on plastic-fungi interactions in marine environments. We address (i) the currently known diversity of fungi colonizing marine plastic debris and provide (ii) an overview of methods applied to investigate the role of fungi in plastic degradation, highlighting their advantages and drawbacks. We also highlight (iii) the underestimated role of fungi as plastic degraders in marine habitats.

Ocean Plastic Pollution

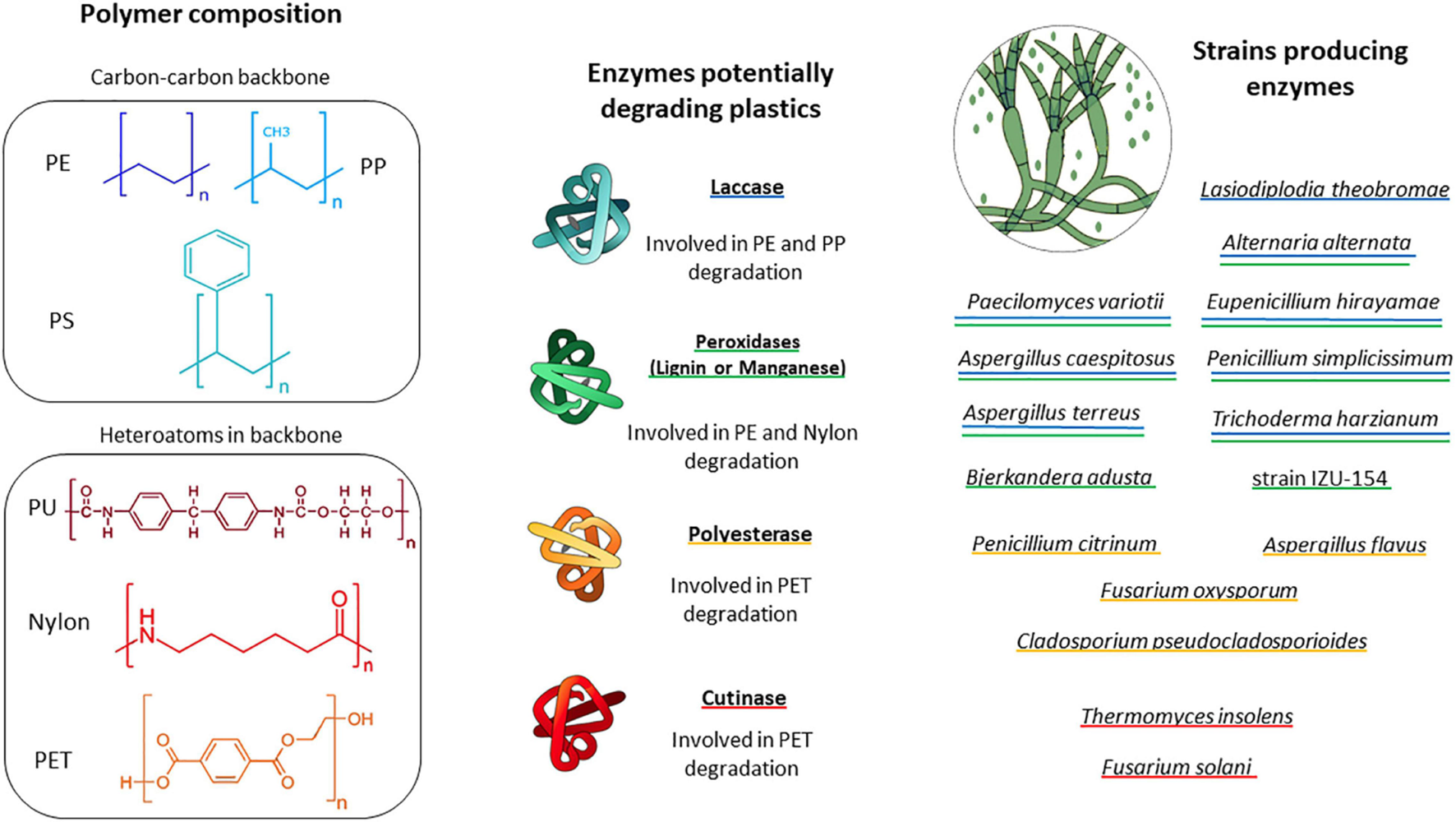

Plastics are man-made materials of mostly petrochemical origin – so-called conventional plastics that are commonly considered as non-biodegradable (Wayman and Niemann, 2021). Most conventional plastics comprise a carbon-carbon backbone, e.g., polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP) and polystyrene (PS), while other plastics feature heteroatoms, e.g., polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyurethane (PU) or polyamides (PA, Nylon). Conventional plastics are used in nearly all industrial sectors, most importantly packaging, construction and transport. The global annual production of plastics reached 359 Mt in 2018 (PlasticsEurope, 2020). Recently, biopolymer alternatives, based on renewable sources (e.g., starch and cellulose) have been developed, but their global market share is still small. In 2020, the global production of bioplastics amounted to approximately 2 Mt (Bioplastics Market Data update, 2020). Among the plastic types produced from renewable carbon sources, approximately half are biodegradable, while the second half is non-biodegradable.

A substantial fraction of plastic waste is mismanaged (Geyer et al., 2017), and it has been estimated that this fraction represented an average of 80 Mt (60 to 99 Mt) accumulated in total (Lebreton and Andrady, 2019). Mismanaged plastic waste ends up in all ecosystem compartments, such as soils (Chae and An, 2018), lakes (Mason et al., 2016) and rivers (Lebreton et al., 2017). Thus, freshwater bodies function as a transport vector for plastic ultimately reaching the ocean though the magnitude of this transport mechanism is discussed controversially (Weiss et al., 2021). In addition, plastic litter can be airborne, thus, the atmospheric deposition of plastic litter is a potentially important source for the ocean’s plastic budget (Liss, 2020). Indeed, plastic litter has emerged as a major pollution issue in marine environments (Eriksen et al., 2014; UNEP, 2014; van Sebille et al., 2015; Wayman and Niemann, 2021). Plastic debris forms the most abundant component of marine litter, accounting for up to 95% of waste found on shorelines, ocean surface water and the seafloor (Galgani et al., 2015). In fact, sedimented plastic litter might become a stratigraphic marker horizon of the Anthropocene epoch (Zalasiewicz et al., 2016). It has been estimated that 0.1% (Cózar et al., 2015) to up to 4.6% (Jambeck et al., 2015) of the global plastic production enters the ocean. As a result, the total accumulated plastic waste in the ocean might have reached 320 Mt in the year 2015 (Wayman and Niemann, 2021).

Plastic floating at the ocean surface is typically dominated by PE and PP, roughly in accordance with global production figures (Erni-Cassola et al., 2019). However, plastic debris in the ocean varies in size: macroplastics (>5 mm), microplastics (1 μm – 5 mm) and nanoplastics (<1 μm) (Wayman and Niemann, 2021). Several studies have tried to quantify the different size fractions to estimate the total concentration of plastics and the fate of it in marine environments. For example, in the Mediterranean Sea, the density of floating microplastic was about 2.5 × 105 items per km2 (Cózar et al., 2015). The abundance of floating plastic in the ocean is usually determined by surface trawling with nets (typically > 300 μm mesh size). Consequently, these methods discriminate against smaller size classes, which could account for an important fraction of the floating plastic budget (Poulain et al., 2019). Furthermore, surface trawls do not account for submerged and sedimented plastics debris (Woodall et al., 2014). Finally, the distribution of floating plastic is not homogenous, as large quantities concentrate in subtropical ocean gyres and enclosed basins, making balanced sampling efforts over large areas difficult (Lindeque et al., 2020).

Microbial Biofilms on Marine Plastic Debris

Rapid microbial colonization occurs on any available material that ends up in the ocean, whether it is of natural or synthetic origin (such as plastic debris). From a microbial perspective, transiting from pelagic to a particle-attached lifestyle provides advantages; e.g., better access to nutrients, and protection against UV exposure and grazing (de Carvalho, 2018). Several studies have investigated the composition of microbial communities living on plastic materials in different marine environments (Zettler et al., 2013; Amaral-Zettler et al., 2015; Eich et al., 2015; Oberbeckmann et al., 2016; Debroas et al., 2017; Dussud et al., 2018; Ogonowski et al., 2018; Miao et al., 2019; Dudek et al., 2020; Krause et al., 2020; Vaksmaa et al., 2021b). Some of these reported a difference in community structure when comparing microbes in biofilms on plastics to those in the surrounding seawater or those attached to natural surfaces. A detailed overview of this matter is compiled in Wright et al. (2020). However, most studies applied amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, and focused on bacterial and archaeal communities in biofilms attached to the plastic debris. In contrast, fungal community composition on plastic in the marine environment has, until now, been investigated seldomly (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Source | Polymer | Location | Primers | Phyla detected |

| Oberbeckmann et al., 2016 | PET bottles | North Sea | 1391F – 1795R | Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Chytridiomycota |

| Kettner et al., 2017, 2019 | PE, PS | Baltic Sea and Warnow river | Eu565F – Eu918R | Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota and Rozellomycota |

| De Tender et al., 2017 | PE | North Sea (coast and offshore) | fITS7bis (adapted) – ITS4NGSr | Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, and Mucormycota |

| Kirstein et al., 2018 | HDPE, LDPE, PP, PS and PET | North Sea (flow-through system) | Eu565F – Eu918R | Chytridiomycota |

| Lacerda et al., 2020 | PE, Nylon, PU, PP and PS | Western south Atlantic and Antarctic Peninsula | 1391F – EukB, TAReuk454FWD1 – TAReukREV3, ITS1f – ITS4 and gITS7 – ITS4 | Aphelidomycota, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Rozellomycota, Mucoromycota and Zoopagomycota |

Studies on the diversity of fungal communities on microplastics in marine environments.

All studies applied next generation sequencing by using the Illumina MiSeq platform.

A Brief Introduction to the Fungal Kingdom

The fungal kingdom constitutes a major lineage within the domain Eukarya and diverged from a common ancestor with the animals >800 million years ago (Parfrey et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2015). Fungi exhibit highly diverse lifestyles and can cope with different redox conditions. The majority of fungi seemingly prefer oxic environments, however some fungal species inhabit oxygen minimum zones (Stief et al., 2014). Furthermore, anaerobic fungi (mainly studied in gut microbiomes) have been identified (Gruninger et al., 2014; Mura et al., 2019). Morphologically, fungi may be unicellular (e.g., yeasts and cells with a flagellum such as zoospores), filamentous (e.g., molds and mushrooms) or dimorphic (i.e., they exists in two forms, yeast-like single cells or hyphae forming) (Boyce and Andrianopoulos, 2015). They can be found as free-living organisms, in mutualistic symbiotic associations (such as those forming mycorrhizas, lichens, in gut microbiomes) (Watkinson, 2016) or as parasitic pathogens of several plants and animals, including humans (Szabo and Bushnell, 2001). Fungi are ubiquitous and occur throughout terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments (Sutherland, 1916; Raghukumar, 2017; Walker et al., 2017; Gladfelter et al., 2019).

Taxonomically, nineteen major fungal phyla are recognized: Aphelidiomycota, Ascomycota, Basidiobolomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Calcarisporiellomycota, Caulochytriomycota, Chytridiomycota, Entomophthoromycota, Entorrhizomycota, Glomeromycota, Kickxellomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Mortierellomycota, Mucoromycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Olpidiomycota, Rozellomycota, and Zoopagomycota (Wijayawardene et al., 2020). However, the phylogeny and taxonomy of the fungal kingdom has been a matter of debate (Hibbett et al., 2007; Spatafora et al., 2016, 2017). Some fungal phyla are rarely sampled and our understanding of the deeply branching groups is insufficient (Naranjo-Ortiz and Gabaldón, 2019). Lately, the number of available fungal genomes has been increasing. But these new data showed that complex inter-species relationships occur, such as introgression and hybridization (Gabaldón, 2020), that blur the definition of a species. The estimated total number of fungal species could range from 2 to 4 million (Hawksworth and Lücking, 2017), but only ∼100000 have been described (Wu et al., 2019) of which only ∼1100 species originate from marine environments (Amend et al., 2019).

Recently, an online database, www.marinefungi.org, containing marine fungal species was created (Jones et al., 2019). Many fungal species are found in both, terrestrial and marine environments (Gladfelter et al., 2019). It has been proposed that early diverging fungi, Chytridiomycota and Rozellomycota, originate from aquatic environments (Berbee et al., 2017, 2020). These phyla also have members found in the present-day ocean. On the other hand, fungi from the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota phyla, commonly present in marine environments, are proposed to originate from terrestrial ancestors. Because of this difference in origin (terrestrial vs. aquatic), a clear definition of “marine fungus” is challenging. The recent definition suggests that a marine fungus is “any fungus that is recovered repeatedly from marine habitats and: (1) is able to grow and/or sporulate (on substrata) in marine environments; or (2) forms symbiotic relationships with other marine organisms; or (3) is shown to adapt and evolve at the genetic level or is metabolically active in marine environments” (Pang et al., 2016). Marine fungi are found ubiquitously in the ocean (Comeau et al., 2016; Tisthammer et al., 2016; Raghukumar, 2017) including coastal environments (Taylor and Cunliffe, 2016; Picard, 2017; Banos et al., 2020), mangroves (Hyde and Lee, 1995; Alias et al., 2010; Pang et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2019), the water column (Richards et al., 2015; Tisthammer et al., 2016; Morales et al., 2019) and sediments (Kohlmeyer and Kohlmeyer, 1979a; Khudyakova et al., 2000; Mouton et al., 2012; Tisthammer et al., 2016). Marine fungi have also been detected in extreme marine habitats such as the deep sea biosphere (Orsi et al., 2013; Rédou et al., 2015), the Arctic (Rämä et al., 2017; Hassett et al., 2019) and oxygen minimum zones (Cathrine and Raghukumar, 2009; Jebaraj et al., 2010; Manohar et al., 2015).

Metabolically, fungi participate in different biogeochemical processes and occupy a plethora of ecological niches. Fungi play a major role in decomposing recalcitrant substrates, making them an integral part of food web structures, contributing to carbon cycling and nutrient regeneration in, at least, terrestrial environments. For example, saprophytic fungi accelerate carbon and nitrogen cycling and symbiotic fungi such as mycorrhiza networks, enhance primary production in symbionts and hosts (Lindahl et al., 2007; Walder et al., 2012). Similar to terrestrial systems, parasitic fungi in aquatic environments were found to have a great impact on pelagic food webs and thus biogeochemical cycling (Jobard et al., 2010; Sime-Ngando, 2012). Also some symbiotic interactions are known from the marine environment, for example, with phytoplankton seaweeds and sponges (Rasconi et al., 2011; Richards et al., 2012; Webster and Taylor, 2012; Du et al., 2019). Similar to terrestrial systems, fungi in coastal and surface marine environments were found to degrade wood (lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose) (Bucher et al., 2004) and remains of marine animals (Kohlmeyer and Kohlmeyer, 1979b,c; Raghukumar, 2017). Marine fungi were furthermore found to degrade complex components of algae such as agar (in laboratory conditions; Balabanova et al., 2018) and fungi dominate the microbial composition of bathypelagic marine snow where they might play the role as saprotrophs (Bochdansky et al., 2017). Fungi contribute to different nitrogen cycle processes such as nitrification (Falih and Wainwright, 1995) and denitrification (Shoun et al., 1992; Stief et al., 2014; Maeda et al., 2015) in both, terrestrial and the marine environment (Cathrine and Raghukumar, 2009). Marine fungi mobilize metals by excreting siderophores and act as bio-sorbents for some metals, thereby alleviating metal toxicity (Taboski et al., 2005; Vala, 2010). These processes influence the cycles of several elements among them: Fe, Mn, Hg, Ni, Zn, Ag, Cu, Cd, and Pb (Gadd, 2004). Finally, some fungi break down rocks and minerals to harvest nutrients (Ortega-Morales et al., 2016).

Life on Plastic Is Fantastic: Fungal Colonization of Marine Plastic Debris

Fungi in Marine Environments as Part of Marine Plastic Debris Associated Biofilms

Marine fungi are generally understudied, which is also reflected by the relatively limited number of studies targeting fungi on marine plastic debris (MPD) (Jacquin et al., 2019). Oberbeckmann et al. (2016) conducted a seasonal comparison of microbial communities including both bacteria and fungi on submerged PET bottles, glass slides, and seawater in the North Sea. Fungal communities were represented by Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Chytridiomycota. The study showed that the PET-attached eukaryotic communities (fungi among them) varied significantly with season and location. Kettner et al. (2017, 2019) conducted exposure experiments with PE and PS in the Baltic Sea and the river Warnow and investigated colonization of these plastic surfaces by fungi. The fungal genus Chytridium, as well as fungi-like Rhinosporideacae, Rhizidiomyces, and Pythium taxa, had a high read count on both plastic types at both locations. However, a substantial number of sequences was assigned as unclassified fungi. The fungal community composition was significantly influenced by location but not polymer type. Furthermore, the alpha diversity was significantly lower for PE and PS compared to the surrounding water and wood particles. De Tender et al. (2017) conducted a 44-week experiment during which PE plastic sheets and dolly ropes were weighed down close to the sediment at a harbor and an offshore location in the North Sea. Similar to the Baltic Sea studies by Kettner et al. (2017, 2019), they found that the Ascomycota were highly abundant followed by a smaller fraction of Basidiomycota and Mucoromycota. Furthermore, a minor fraction of members of Ascomycota from the Lecanoromycetes class (Physconia, Candelariella, Caloplaca) were identified. Analyses on the beta diversity of the fungal community composition showed statistically significant effects of sample type (natural substrate vs. plastic polymers), environment, and exposure time. Some of the detected species were previously identified as potential PE degraders in terrestrial environments: Cladosporium cladosporioides (Bonhomme et al., 2003) and Fusarium redolens (Albertsson, 1980; Albertsson and Karlsson, 1990).

Recently, Lacerda et al. (2020) studied the fungal diversity associated with plastics in the surface waters of the Western South Atlantic and the Antarctic Peninsula by investigating three different molecular marker genes for fungal identification: ITS2 (Internal transcribed spacer), the variable regions V4 and V9 of the 18S rRNA gene sequence. To date, this is the only study aiming to resolve fungal diversity on plastic using multiple marker genes. Across the tested marker genes, a total of 64 different fungal orders were associated with plastics. The primers targeting the 18S rRNA gene (V4 and V9 regions) were able to detect a higher number of Chytridiomycota. Some taxa that were totally omitted by the ITS2 marker were detected, such as Rozellomycota, Zoopagomycota, Aphelidomycota, and Blastocladiomycota. Across all samples, the genus Aspergillus was the most abundant. Some of its OTUs were assigned at the species level, identifying A. vitricola, A. restricus, and A. wentii. None of the identified strains were previously reported as plastic degraders, although other Aspergillus species have been shown to be able to oxidize different plastic types (Table 2). Lacerda and colleagues also reported on fungal taxa, such as Aphelidomycota, Zoopagomycota, Mucoromycota, and Blastocladiomycota, that had previously not been detected to colonize plastic in the marine environment.

TABLE 2

| Strains | References | Environment of isolation | Polymer | Degradation assessment technique | Incubation time experiment | Main observed results |

| Alternaria alternata | Ameen et al., 2015 | Mangrove | LDPE | Weight loss, SEM, enzyme activity assays, quantification of CO2 | 28 days | Increased biomass in culture with LDPE, CO2 emission and increased production of laccase, MnP and lignin peroxidase |

| Aspergillus caespitosus | Ameen et al., 2015 | Mangrove | LDPE | Weight loss, SEM, enzyme activity assays, quantification of CO2 | 28 days | Increased biomass in culture with LDPE, CO2 emission and increased production of laccase and MnP |

| Aspergillus flavus | Alshehrei, 2017 | Seawater | PE | Weight loss, tensile strength, SEM, FTIR | 30 days | 16.2% weight loss of polyethylene |

| Aspergillus flavus | Deepika and Madhuri, 2015 | Soil from waste disposal site | PE | Halo test, weight loss | 180 days | Reduction of 16% in molecular weight |

| Aspergillus flavus | Zhang et al., 2020 | Guts of wax moth Galleria mellonella | HDPE | Halo test, HT-GPC, FTIR | 28 days | Decreased Mn. Carbonyls groups FTIR and two laccase-like multicopper oxidases (LMCOs) genes, afla_006190 and afla_053930, displayed up-regulation |

| Aspergillus flavus ITCC no. 6051 | Mathur and Prasad, 2012 | Soil from waste disposal site | PU | Weight loss, SEM, FTIR, and thermogravimetric analysis, enzyme activity assay | 30 days | Weight loss of PU, detection of PU degradation via FTIR and production of esterase |

| Aspergillus flavus VRKPT2 | Sangeetha Devi et al., 2015 | Coastal area of gulf of Mannar | HDPE | SEM, FTIR, weight loss, total protein content measurement | 30 days | Weight loss of 8.5 ± 0.1% |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Alshehrei, 2017 | Seawater | PE | Weight loss, tensile strength, SEM, FTIR | 30 days | 20.5% weight loss of polyethylene |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Zahra et al., 2010 | Landfill soil | LDPE | UV treated LDPE, SEM, FTIR | 100 days | Molecular weight decreases and use of UV LDPE as sole Carbon source and detection of structural changes by FTIR |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Raghavendra et al., 2016 | Soil from waste disposal site | PU and LDPE UV irradiated for 50 h | Halo test, weight loss | 90 days | Weight loss for PE and PU after 90 days and loss of tensile strength |

| Aspergillus glaucus | Kathiresan, 2003 | Mangrove soil | PE | Weight loss | 30 days | Weight loss of 28.8 ± 2.4% |

| Aspergillus niger | Alshehrei, 2017 | Seawater | PE | Weight loss, tensile strength, SEM, FTIR | 30 days | 19.5% weight loss of PE |

| Aspergillus niger | Raghavendra et al., 2016 | Soil from waste disposal site | PU and LDPE UV irradiated for 50 h | Halo test, weight loss | 90 days | Weight loss for PE and PU after 90 days and loss of tensile strength |

| Aspergillus niger | Deepika and Madhuri, 2015 | Soil from waste disposal site | PE | Halo test, weight loss | 180 days | Reduction of 26% in Mn |

| Aspergillus niger | Kathiresan, 2003 | Mangrove soil | PE | Weight loss | 30 days | Weight loss of 17.4 ± 2% |

| Aspergillus niger (ITCC no. 6052) | Mathur et al., 2011 | Soil from waste disposal site | HDPE | Weight loss, tensile strength, SEM, FTIR | 30 days | Reduction of 3.44% in Mn and 61% reduction in tensile strength |

| Aspergillus nomius | Munir et al., 2018 | Soil from waste disposal site | LDPE | Weight loss, tensile strength | 45 days | Weight loss of 6.63% and tensile strength reduction of 40% |

| Aspergillus oryzae | Muhonja et al., 2018 | Soil from waste disposal site | LDPE | Weight loss, FTIR analysis | 112 weeks | Weight loss of 36.4 ± 5.53% and degradation products detection by FTIR |

| Aspergillus sp. | Pramila and Ramesh, 2011 | Seawater | LDPE | SEM, Quantification of CO2 | 7 to 17 days | Visual signs of degradation via SEM and about 4g–L of CO2 produced |

| Aspergillus sp. | Osman et al., 2018 | Soil from waste disposal site | PU | Weight loss, quantification of CO2, SEM, FTIR, DSC | 28 days | 15–20% of weight loss. Change in melting temperature and detection of degradation products via FTIR |

| Aspergillus sp. in co-culture with Lysinibacillus xylanilyticus XDB9 | Esmaeili et al., 2013 | Landfill soils | UV and non-UV irradiated LDPE | Tensile strength, SEM, FTIR, CO2 measurements | 126 days | Carbon dioxide measurements: biodegradation 7.6 and 8.6% of mineralization for the non-UV irradiated and UV irradiated LDPE respectively after 126 days vs. 29.5 and 15.8% in presence of co-culture |

| Aspergillus sydowii | Sangale et al., 2019 | Mangrove dumpsite | PE | Weight loss, tensile strength, SEM, FTIR | 60 days | Cracks and holes visible by SEM, FTIR analysis, weight loss of 37.94 ± 3.06% (pH = 7) and tensile strength reduction |

| Aspergillus terreus | Sangale et al., 2019 | Mangrove dumpsite | PE | Weight loss, tensile strength, SEM, FTIR | 60 days | Cracks and holes visible by SEM, FTIR analysis, weight loss of 41.82 ± 5.47% (pH = 9.5) and tensile strength reduction |

| Aspergillus terreus | Alshehrei, 2017 | Seawater | PE | Weight loss, tensile strength, SEM, FTIR | 30 days | 21.8% weight loss of polyethylene |

| Aspergillus terreus | Ameen et al., 2015 | Mangrove | LDPE | Weight loss, SEM, enzyme activity assays, quantification of CO2 | 28 days | Increased biomass in culture with LDPE, CO2 emission and increased production of laccase, MnP and lignin peroxidase |

| Aspergillus terreus | Zahra et al., 2010 | Soil from waste disposal site | LDPE | UV treated LDPE, SEM, FTIR | 100 days | Molecular weight decreases and use of UV LDPE as sole carbon source and detection of structural changes by FTIR |

| Aspergillus terreus MF12 | Balasubramanian et al., 2014 | Soil with PE wastes | HDPE was pretreated by physical (heat and UV), chemical (citric acid and KMnO4/HCl), and biological (microbial) treatments in different combinations | SEM, GC-MS, weight loss and FTIR | 30 days | Highest degradation rates for UV treated PE |

| Aspergillus tubingensis | Khan et al., 2017 | PU buried in soil | PU | SEM, tensile strength and ATR-FTIR | 20 days | SEM surface cracking, erosion, pore formation or loss in tensile strength and ATR-FTIR detected degradation products |

| Aspergillus tubingensis VRKPT1 | Sangeetha Devi et al., 2015 | Coastal area of gulf of Mannar | HDPE | SEM, FTIR, weight loss, total protein content (alkaline hydrolysis treatment) | 30 days | Weight loss of 6 ± 0.2% |

| Bjerkandera adusta | Friedrich et al., 2007 | Collection | Nylon-6 | Halo test, SEM, DSC, HPLC, Enzyme activity assay | 60 days | Decrease in number Mn and production of MnP in presence of Nylon |

| Cladosporium cladosporioides | Brunner et al., 2018 | Shoreline of lake Zurich | PU | Halo test | several days | Halos indicating potential plastic usage |

| Cladosporium pseudocladosporioides strain T1.PL.1 | Álvarez-Barragán et al., 2016 | Soil | PU (Impranil) | Halo test, SEM, FTIR, GCMS, enzyme activity assay | 14 days | detection of PU degradation via FTIR and GCMS. Production of esterase in presence of PU |

| Eupenicillium hirayamae | Ameen et al., 2015 | Mangrove | LDPE | Weight loss, SEM, enzyme activity assays, quantification of CO2 | 28 days | Increased biomass in culture with LDPE, CO2 emission and increased production of laccase and MnP |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Raghavendra et al., 2016 | Soil from waste disposal site | PU and LDPE UV irradiated for 50 h | Halo test, weight loss | 90 days | Weight loss for PE and PU after 90 days and loss of tensile strength |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nimchua et al., 2007 | Terrestrial environment | PET | Enzyme activity assay and increase of hydrophilicity detection | 7 days | Increase of hydrophobicity and release of TPA from PET in presence of esterase |

| Fusarium solani | Ronkvist et al., 2009 | Collection | PET (low crystallinity) | Weight loss, SEM, DSC and HPLC | 4 days | Degradation of PET into TPA via cutinase (named FsC) and 5% of film weight loss |

| Fusarium sp. | Tachibana et al., 2010 | Nylon 4 films buried in composted soil | Nylon-4 | Weight loss, Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), NMR, MALDI-TOF and SEM | 35 days | Decreased average weight and SEM evidence |

| Gloeophyllum trabeum | Krueger et al., 2015 | Collection | PS (polystyrene sulfonate) | Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) | 20 days | Depolymerization of up to 50% reduction in Mn |

| Lasiodiplodia crassispora | Raghavendra et al., 2016 | Soil from waste disposal site | PU and LDPE UV irradiated for 50 h | Halo test, weight loss | 90 days | Weight loss for PE and PU after 90 days and loss of tensile strength |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Sheik et al., 2015 | Terrestrial environment | LDPE and PP (Gamma irradiated) | Weight loss, DSC, SEM, FTIR, enzyme activity assay | 90 days | production laccase, weight loss in PP and PE and detection of degradation products via FTIR |

| Leptosphaeria sp. | Brunner et al., 2018 | Shoreline of lake Zurich | PE, PU | Halo test | several days | Halos indicating potential plastic usage |

| Paecilomyces variotii | Ameen et al., 2015 | Mangrove | LDPE | Weight loss, SEM, Enzyme Activity Assays, Estimation of CO2 Evolution | 28 days | Increased biomass in culture with LDPE, CO2 emission and increased production of laccase, MnP and lignin peroxidase |

| Penicillium chrysogenum | Ojha et al., 2017 | Soil from waste disposal site | LDPE and HDPE | SEM, AFM, and FTIR | 90 days | Visual with SEM and detection of degradation compounds with FTIR after 60 days |

| Penicillium citrinum | Liebminger et al., 2007 | Landfill soil | PET | Increase of hydrophilicity detection (rising height and drop dissipation measurements) | 1 day | Polyesterase hydrolyzed PET showed by rising height (5.1 cm) and drop dissipation measurements (55 s) |

| Penicillium griseofulvum | Brunner et al., 2018 | Shoreline of lake Zurich | PE, PU | Halos test | several days | Halos indicating potential plastic usage |

| Penicillium oxalicum | Ojha et al., 2017 | Soil from waste disposal site | LDPE and HDPE sheets | SEM, AFM, and FTIR | 90 days | Visual with SEM and detection of degradation compounds with FTIR after 60 days |

| Penicillium simplicissimum | Sowmya et al., 2015 | Soil from waste disposal site | UV treated PE, non uv autoclaved, non uv surface sterilized | Halo test, SEM, FTIR, NMR spectroscopy, Enzyme activity assay | 90 days | Weight loss for UV treated polyethylene was 38%. FTIR detected degradation products. NMR indicated degradation. Both laccase and MnP when treated with PE disk showed weight loss and morphological changes in FTIR spectrum. |

| Penicillium simplicissimum YK | Yamada-Onodera et al., 2001 | Soil | PE | HT-GPC, FTIR, visual growth assessment | 90 days | Lower molecular weight and FTIR detection of degradation products |

| Penicillium sp. | Alshehrei, 2017 | Seawater | PE | Weight loss, tensile strength, SEM, FTIR | 30 days | 43.4% weight loss of PE |

| Penicillium sp. | Raghavendra et al., 2016 | Soil from waste disposal site | PU and LDPE UV irradiated for 50 h | Halo test, weight loss | 90 days | Weight loss for PE and PU after 90 days and loss of tensile strength |

| Penicillium sp. | Magnin et al., 2019 | Waste from terrestrial environment | PU | Weight loss, FTIR, SEM | 60 days | SEM showed visual signs of degradation. Detection of PU degradation via FTIR |

| Phialophora alba | Ameen et al., 2015 | Mangrove | LDPE | Weight loss, SEM, Enzyme Activity Assays, Estimation of CO2 Evolution | 28 days | Increased biomass in culture with LDPE, CO2 emission and increased production of laccase and MnP |

| strain IZU-154 | Deguchi et al., 1997 | Collection | Nylon-6 | NMR | 20 days | NMR showed formation of four end groups, CHO, NHCHO, CH3, and CONH2 indicating degradation |

| strain IZU-154 | Iiyoshi et al., 1998 | Collection | PE | Tensile strength, enzyme activity assay, HT-GPC | 12 days | Decrease of tensile strength in presence of strain. Production of MnP. Loss in Mn with MnP treatment |

| Thermomyces (formerly Humicola) insolens | Ronkvist et al., 2009 | Collection | PET (low crystallinity) | Weight loss, SEM, DSC and HPLC | 6 days | Degradation of PET into TPA via cutinase (named HiC) and 97% weight loss |

| Trichoderma harzianum | Raghavendra et al., 2016 | Soil from waste disposal site | PU and LDPE UV irradiated for 50 h | Halo test, weight loss | 90 days | Weight loss for PE and PU after 90 days and loss of tensile strength |

| Trichoderma harzianum | Sowmya et al., 2014 | Dumpsite soil | PE | SEM, FTIR, NMR analyses and enzyme assay | 90 days | Weight loss of UV PE was 40%. Enzymes causing degradation were identified as laccase and MnP |

| Trichoderma viride | Munir et al., 2018 | Soil from waste disposal site | LDPE | Weight loss, tensile strength | 45 days | Weight loss of 5.13% and tensile strength reduction of 58% |

| Xepiculopsis graminea | Brunner et al., 2018 | Shoreline of lake Zurich | PE, PU | Halos test | several days | Halos indicating potential plastic usage |

| Zalerion maritimum (ATTC 34329) | Paço et al., 2017 | From collection but marine strain | PE | FTIR-ATR, NMR | 28 days | FTIR analysis (carbonyl index), mass loss of 56.7 ± 2.9% of the plastic |

Selection of fungal strains that showed plastic degradation potential.

PE, polyethylene; LDPE, low density polyethylene; HDPE, high density polyethylene; PP, polypropylene; PS, polystyrene; PU, polyurethane; Nylon, polyamides; PET, polyethylene terephthalate; TPA, terephthalic acid; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; FTIR, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; HT-GPC, high temperature gel permeation chromatography; GC-MS, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization – time-of-flight mass spectrometry; Mn, average molecular weight; MnP, manganese peroxidase.

In contrast to environmental studies, Kirstein et al. (2018) studied the microbial composition formed on microplastics under controlled laboratory conditions. Their set-up consisted of a flow-through system with North Sea water in which HDPE (High Density Polyethylene), LDPE (Low Density Polyethylene), PP, PS and PET were incubated in the dark. The 18S rRNA gene sequencing analysis of the eukaryotic community of biofilms revealed that the highest fungal read abundances belonged to Chytridiomycota (up to 3% of sequences on PET). This can be explained by this taxa’s dominance throughout aquatic environments (Comeau et al., 2016) or the compatibility of biofilm presence on PET and chytrid’s parasitic lifestyle.

Plastic Biodegradation Potential of Fungi

Biodegradation is the degradation of compounds and substrates mediated by living organisms, most commonly microorganisms. The soluble products of biodegradation (typically low molecular weight compounds) are absorbed or assimilated by the microorganisms. The biodegradation can be partial or complete. Complete biodegradation results in the formation of CO2 and is also referred to as biomineralization. On the other hand, degradation of organic matter without a terminal electron acceptor, conditions that are countered in some reduced environments, leads to the formation of CH4 and/or other short-chain hydrocarbons. In natural environments, biodegradation is mediated by enzymes or by other compounds (such as acids and peroxides), secreted by microorganisms.

Fungi are able to degrade synthetic compounds; e.g., persistent organic pollutants (POPs) (Singleton, 2001), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (Cerniglia and Sutherland, 2001), benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylenes (BTEX compounds) (Buswell, 2001) and pesticides (Pinto et al., 2012). The metabolic versatility of fungi and ability to degrade complex compounds indicates that biodegradation of plastics in the environment could be a potential metabolic trait of some fungi (Vaksmaa et al., 2021a). To date, some plastic degrading fungi have indeed been identified mostly from the Ascomycete phylum to which also Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Penicillium belong (Table 2Fusarium sp. and F. oxysporum isolated from soil provoked weight loss of Nylon, PE, and PU) (Tachibana et al., 2010; Raghavendra et al., 2016). F. solani from a collection hydrolyzed PET to terephthalic acid (TPA) via a cutinase (Ronkvist et al., 2009). Furthermore, several strains belonging to Penicillium are considered as potential plastic degraders. P. chrysogenum, P. oxalicum, P. simplicissimum isolated from soil (Yamada-Onodera et al., 2001; Sowmya et al., 2012; Ojha et al., 2017) and Penicillium sp. isolated from seawater (Alshehrei, 2017) showed potential to degrade PE. Similar to Penicillium, different species belonging to the genus Aspergillus were found to be potential plastic degraders as well (Table 2). A. flavus isolated from soil (Deepika and Madhuri, 2015), wax moth gut (Zhang et al., 2020) and a marine environment (Sangeetha Devi et al., 2015; Alshehrei, 2017) exhibited the potential to degrade PE and A. niger isolated from soil (Deepika and Madhuri, 2015; Raghavendra et al., 2016) and seawater (Alshehrei, 2017) showed potential to degrade PE and PU. Also, A. terreus isolated from soil (Zahra et al., 2010), mangrove sediments (Ameen et al., 2015; Sangale et al., 2019) and seawater (Alshehrei, 2017) were potentially able to degrade PE. In addition to these species, several other types of Aspergillus strains were considered as potential PE and PU degraders. Many of the plastic degrading species that were isolated from terrestrial environments (Table 2) are also found in marine habitats. However, it has not been confirmed if all of the plastic degrading strains found in terrestrial environments perform equally well in the marine realm.

The enzymes utilized by plastic degrading fungi in the environment are typically not constrained. However, fungi produce a wide range of enzymes that have the potential to break down the chemical bonds of the plastic polymers (Figure 1). Amongst these are manganese peroxidase (MnP) and lignin peroxidase (LiP), which are commonly associated with lignin degradation (Xu et al., 2013). These enzymes catalyze oxidation-reduction reactions, involving free radicals, transforming several compounds into oxidized or polymerized products (Wei and Zimmermann, 2017). Peroxidase are also used in industrial applications for degrading recalcitrant organic pollutants, PAHs, industrial dyes and chlorophenols (Qin et al., 2014). Lignin peroxidase is characterized by a high redox potential, and enables oxidation of non-phenolic aromatic compounds. Another enzyme that might be involved in plastic degradation is laccase, a multicopper oxidase, which is a well classified lignin-modifying enzyme (Mehra et al., 2018) and mediates the oxidation of the polymers’ carbon backbone (Amobonye et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1

Schematic of important plastic types encountered in the marine environment. Fungal enzymes and fungal groups potentially involved in plastic degradation are displayed. Blue underline indicates fungi producing laccase. Green underline indicates fungi producing peroxidase, Yellow underline indicates fungi producing polyesterase and red underline indicates fungi producing cutinase. PE, polyethylene; PP, polypropylene; PS, polystyrene; PU, polyurethane; Nylon, polyamides; PET, polyethylene terephthalate.

Elevated laccase, manganese peroxidase and lignin peroxidase activities were observed during PE degradation by a fungal consortium in a mangrove (Ameen et al., 2015). It appears likely that these enzymes also play a role in potential plastic degradation in the ocean. Marine adapted fungi have the ability to regulate the expression of their enzymes according to salinity. Cultivated in marine conditions, Peniophora sp., for example, showed multigene transcription of ligninolytic laccase enzymes (Otero et al., 2017). Fungi isolated from marine environments can also produce enzymes that allow them to grow in liquid media with sole carbon sources such as agar, alginate, carrageenans, laminarians, and ulvans, i.e., polymers which are common in the marine realm (Wang et al., 2016). However, whether these compounds are also utilized by marine fungi in situ, i.e., in the ocean, still needs to be shown. Similarly to several biopolymers in the terrestrial realm, these marine polymers also feature chemical similarities with some plastic types (presence of aromatic compounds, presence of carbonyl groups). The ability of marine fungi to regulate their metabolism and to adapt to different environments and substrates indicates that the number of marine fungi with the potential to degrade plastics could be underestimated.

Analytical Tools for Assessing the Potential for Fungi-Mediated Plastic Degradation

Relatively little is known about the potential for microbial plastic biodegradation in the marine environment (Wayman and Niemann, 2021). However, the chemical structures of most plastic polymers render them rather durable, which makes it challenging to evaluate the biodegradability of conventional plastics and to identify the key organisms mediating this process. As the majority of studies evaluating plastic breakdown have been conducted in the terrestrial environment (Ru et al., 2020), the methods reviewed below do not focus solely on the marine systems (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Methods | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Gravimetric measurements and growth of biomass | Monitoring strains biomass growth with plastic as sole carbon source and plastic weight changes | Easily performed measurement and inexpensive | Not accurate and weight loss can be due to other processes than biodegradation |

| Clearance zone formation | Visual assessment based on the appearance of clearance zones on agar plates containing solubilized plastic | Easy assessment and cheap. Great screening technique before further studies. | The plastic is not the sole carbon source (presence of agar) so the strain growth cannot be automatically imputed to the biodegradation of plastic |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Microscopy technique allowing visual assessment of strain growth and physical changes within the polymer | High resolution allowing a clear visual assessment | Changes in polymer physical structure and strain growth are not sufficient to prove plastic biodegradation |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Microscopy technique allowing collection of data on the surface roughness | Precise quantitative and qualitative data on the surface roughness | Changes in polymer surface roughness are not sufficient to prove plastic biodegradation |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Spectroscopy technique allowing the obtention of an infrared spectrum of physio-chemical properties of a sample | Reliable detection and semi-quantification of changes of the polymer configuration | Sensitive to biofilm attachment and chemical treatments. Only proves degradation of the plastic |

| Assays with 13C or 14C labeled polymers | Tracing of isotopically labeled carbon from the plastic polymers | Precise quantification of plastic degradation products and traces incorporation in microbial biomass | High costs |

| Respiratory assays | Measurements of O2 consumption and/or CO2 production of strains | Can provide quantitative information on degradation | Respiration cannot be automatically imputed to biodegradation of plastic |

| Tensile resistance Thermo Gravimetrical Analysis (TGA) Differential scanning calorimetric analysis (DSC) High-Temperature Gel Permeation Chromatography (HT-GPC) |

Detection of physio-chemical properties changes (tensile resistance strength, thermal stability, glass transmission, molecular weight). The decrease detected in these properties indicates structural alteration of the plastic polymer | Easy measurements that can indicate plastic polymer degradation | Changes in these properties do not automatically indicate biodegradation of plastic as these methods are sensitive to other processes of degradation |

Most common methods used to assess plastic degradation advantages and disadvantages.

Gravimetric Measurements and Growth of Biomass

To date, the most commonly applied technique to assess plastic biodegradation is based on gravimetric measurement of weight/mass loss of the polymer over a specific time period during which the plastic is exposed to an environmental matrix or to cultured microbes. Weight loss of plastic has been demonstrated both in studies where plastics were exposed to soils, the marine water column and sediments (Syranidou et al., 2017; Welden and Cowie, 2017) as well as in studies focusing on the capability of a single strain to degrade specific plastic polymers (Table 2). However, in environmental studies, it remains unclear to which extent the observed plastic breakdown was due to solely fungal activity. In the environment, the observed breakdown may be facilitated by microorganisms other than fungi and/or by microbial consortia, and/or by abiotic factors, such as mechanical degradation. These factors remain inseparable from potential fungal biodegradation. In contrast, laboratory studies with single strains decrease the number of biotic and abiotic factors, that may contribute to the plastic degradation. Fungal isolates recovered from municipal solid waste revealed that Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus fumigatus, Lasiodiplodia crassispora, Aspergillus niger, Penicillium sp., and Trichoderma harzianum were all able to cause a weight loss of PE as well as PU (Raghavendra et al., 2016). A. niger showed the highest biodegradation efficiency leading to a weight loss of 2.9, 4.3, and 5.1% of LDPE sheets and 0.8, 1.5, and 2.2% of PU sheets exposed for 30, 60 and 90 days, respectively. Fusarium oxysporum as well as Aspergillus sp. have previously been shown to cause weight loss of LDPE (Das and Kumar, 2014). Trichoderma viride and Aspergillus nomius, isolated from landfill soil, caused weight loss of LDPE films of 5.1 and 6.6%, respectively, after 45 days (Munir et al., 2018). Cladosporium tenuissimum caused 25.9 and 65.3% of weight loss of PE-PU foams with and without flame retardants, respectively (Álvarez-Barragán et al., 2016). The marine fungus Zalerion maritimum exposed to PE microplastics caused mass loss of 56.7 ± 2.9% of the plastic, corresponding to 43% of removal after 2 weeks of exposure (Paço et al., 2017).

Although determining the weight loss of plastic is a straightforward method, it requires a long monitoring time, ranging from months to years to yield measurable gravimetric changes, while short term studies often yield inconclusive results (Lee et al., 1991). Gravimetric measurements require post incubation treatments, i.e., the removal of the biofilm from the incubated plastic. This can easily cause measurement artifacts; e.g., the incomplete removal of biofilm or accidental removal of a polymer respectively leads to an under or overestimation of weight loss. Weight loss measurements indicate that plastic polymers indeed disintegrate over time, however, this type of measurement does not reveal whether the polymer is broken down physiochemically (e.g., plastics release lower molecular weight compounds as a result of photooxidation; Wayman and Niemann, 2021) or if the plastic polymer was hydrolyzed and metabolized by microbes. Some plastics (e.g., polyvinyl chloride) contain high quantities of additives which, if soluble, can be released, and thus bias weight loss measurements. Also, biomass figures (i.e., cell numbers, culture dry weight) are typically not reported for culture-based studies, making these investigations quantitatively non-repeatable, thus, severely limiting comparability. Hence, gravimetric measurements are insufficient to identify plastic degrading organisms and microbial kinetics, but should be accompanied by other methods.

Determining microbial biomass growth on plastic as the sole carbon source (e.g., monitoring cell numbers) has been used to infer the biodegradability of a specific polymer. Together with monitoring the weight loss of the polymer, some studies have measured an increase in fungal biomass as an indicator for the activity of fungi (Paço et al., 2017), and interpreted that the increase in fungal biomass occurred at the expense of carbon originating from the plastics.

Clearance Zone Formation

The growth of fungi at the expense of plastic can be monitored visually with degradation assays based on plates coated with agar and solubilized plastic. Inoculation at the surface and utilization of the plastic leads to the formation of clearance zones, referred to as ‘halos.’ Appearance of ‘halos’ on plates with plastics as the sole carbon source is used as an indicator for plastic degradation. The fungal species Cladosporium cladosporioides, Xepiculopsis graminea, and Penicillium griseofulvum and Leptosphaeria sp., isolated from plastic debris from the lake Zurich, formed clearance zones on PU. However, none of these strains were able to degrade polyethylene (Brunner et al., 2018). Attempts to use polyethylene and clearance zone formation have been successful for Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus flavus (Deepika and Madhuri, 2015).

Clearance zone tests allow for rapid visual observations. However, the technique has the drawback that it requires dissolving the polymer in an organic solvent that can be applied to the petri dish at relatively cold temperatures to avoid agar melting. Furthermore, remnants of the solvents (rather than the plastic) may act as a carbon source for the fungi, leading to false-positive results. In addition, bias associated with clearance zone formation is relatively large, as clearance zones are not uniform in size or shape. Finally, fungi with hyphae may grow through the plastic, thus gain access to the agar below, which can also lead to false-positive results. As agar also represents a carbon source, this test alone does not prove microbial plastic degradation.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is used to create a surface image by directing a high-intensity electron beam at the surface and scanning over this surface. SEM allows high magnification, thus offers high resolution at the nanometer range. SEM-based observations are used to examine and evaluate the colonization of plastic films or particles by microorganisms and to simultaneously visualize cracks, pits and deformations on the plastic surface (Zettler et al., 2013; Vaksmaa et al., 2021a), which in return can indicate if the polymer is degraded. SEM has been applied in several studies to investigate fungi on plastics, for example, to visualize the growth of C. tenuissimum and C. pseudocladosporioides hyphae within PE-PU foams (Álvarez-Barragán et al., 2016). Furthermore, Paço et al. (2017) visualized the attachment of Z. maritimum on PE. With SEM, also surface roughness of single plastic fragments can be visualized. Floating marine plastics often feature signs of abrasion, cracking and ongoing fragmentation (Zettler et al., 2013; Vaksmaa et al., 2021b). Also, plastics exposed to the marine environment developed such signs during the incubation. For example, Welden and Cowie (2017) exposed PE, PP and Nylon to marine sediment for 12 months and found breaks and increased fraying on nylon ropes, surface scratching and roughening on PE filament rope, cracks, fissures and finer surface fibers scaling off from PP.

Scanning electron microscopy is a rapid technique, and allows to visualize surface attachment and morphological microstructures. Observations by SEM without chemical fixation can be achieved by applying FIB-SEM (Focused Ion Beam milling combined with Scanning Electron Microscopy). However, SEM does not allow phylogenetic identification of the microbes (unless the strain-specific morphological characteristics allow this) and the formation and attachment of biofilms is not necessarily an indication for biodegradation. Furthermore, though SEM is a valuable tool to visualize surface defects (e.g., cracks) of the plastic, it does not allow to scale in Z-direction (i.e., to measure the depth of cracks). Alternatively, this may be achieved by atomic force microscopy (AFM). For example, an increase in surface roughness and formation of cracks and grooves on PE films were investigated with AFM after exposure to two different Penicillium strains (Ojha et al., 2017).

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) is a technique used to obtain an infrared spectrum of absorption, emission, and photoconductivity of a material allowing to determine the chemical identity of most polymers. Furthermore, the FTIR spectrum enables detection and semi-quantification of changes of the original polymer configuration, for example, the introduction of carbonyl groups during polymer oxidation (Xu et al., 2019; Almond et al., 2020). The degree of carbonylation can be enumerated by determining the carbonyl index (calculated from the ratio between the integrated band absorbance of the carbonyl and that of the methylene peaks). Carbonyl indexes, as a measure of degradation, has been applied for a variety of polymers, such as PU (Filip, 1979; Álvarez-Barragán et al., 2016), PE (Paço et al., 2017), PS (Tian et al., 2017), and PP (Sheik et al., 2015). PE degradation has been evaluated by FTIR in co-cultures of bacteria and fungi, Lysinibacillus xylanilyticus and A. niger, isolated from soil (Esmaeili et al., 2013). For example, Penicillium variabile CCF3219 strain decreased the carbonyl peaks of pre-oxidized 14C-βPS after 16 weeks of incubation and ozonation pre-treatment enhanced subsequent biodegradation (Tian et al., 2017). An additional advantage of FTIR is that it can be used for small plastic particles (the diffraction limit in IR spectroscopy is ∼10–20 μm).

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy is a straightforward and reliable technique, however, it often yields non-quantitative results that are difficult to compare between studies. Also, the attachment of biofilm on the plastic surfaces affects the plastics optical properties in the IR range because proteinic and polysaccharide contents of the biomass will change the polymer’s IR spectrum (Bonhomme et al., 2003). Samples must hence be pretreated to remove biofilms, e.g., using hydrogen peroxide (Löder and Gerdts, 2015) or sodium dodecyl sulfate (Zhang et al., 2020). These chemicals have been described as the least aggressive. Nevertheless, chemical treatments can modify the molecular structure of plastic surfaces, which can introduce biases.

Assays With 13C or 14C Labeled Polymers

Isotopically labeled plastics can be traced into biodegradation products sensitively and quantitatively (Lanctôt et al., 2018; Taipale et al., 2019). The first studies involving isotopically labeled plastics were conducted with the radio isotope 14C. The fungus Fusarium redolens liberated 14C-CO2, originating from pulverized 14C-labeled HDPE (Albertsson, 1978, 1980; Albertsson et al., 1978). 14C labeled 14C-CO2 formation was also evaluated after photoirradiation of 14C-αPS and 14C-βPS, exposed to garden soil and activated sludge, showing higher 14C-CO2 formation in treatments with photo oxidized polymer. The authors quantified degradation rates and showed that complete degradation of the 14C-αPS polymer in garden soil would require 20 to 80 years and in activated sludge from 11 to 24 years (Guillet et al., 1974). 14C labeled polystyrene was also used to test PS degradation capabilities of 17 different fungal species in a 14 days incubation experiment during which 0 to 0.24% of the 14C-PS was degraded (Kaplan et al., 1979). Because radioactivity can be measured and quantified extremely sensitively, radio isotope probing allows determining extremely low plastic degradation rates. Nevertheless, the use of radio-chemicals entails the necessity for specialized laboratory facilities and trained personnel, and the radio-labeled base materials for synthesizing polymers are extremely expensive or not available at all. This makes the use of radio isotopes mostly impractical. However, using plastics labeled with stable isotopes (e.g., containing a high degree of 13C or 2H) provides a good alternative. Similar to radio isotope probing, stable isotope probing (SIP) offers the advantages to allow tracing plastic derived matter into degradation products (Sander et al., 2019; Taipale et al., 2019), though the ubiquitous presence of 13C and 2H in most types of matter makes SIP assays less sensitive compared to approaches with radio isotopes. Nevertheless, no study using 13C or 2H labeled conventional plastics (PE, PP, PET, PS, PU, and nylon) for investigating interactions of marine fungi and plastics has been published yet. On the other hand, Zumstein et al. (2018) used 13C-PBAT (Polybutylene adipate terephthalate) to study its microbial degradation in soil.

Other Methods

Additional methods to evaluate plastic degradation include the following techniques: (i) Respiratory measurements of O2 consumption or CO2 production, which can provide quantitative information of degradation, but cannot discriminate between different respiration pathways. (ii) Tensile resistance alterations of plastic can be used as a measure of the strength/integrity of the plastics, which will decrease as a function of degradation (yet, also physiochemically induced degradation reduces tensile strength). (iii) Thermo Gravimetrical Analysis (TGA) characterizes the thermal stability of a polymer, which can potentially indicate its degradation (similar to tensile strength). (iv) Differential scanning calorimetric (DSC) analysis assesses the thermal properties of synthetic polymers, such as glass transition Temperature (Tg).

Lower Tg temperatures are often related to a decrease in the stability, indicating degradation (Lucas et al., 2008). (v) High-Temperature Gel Permeation Chromatography (HT-GPC) provides information on the molecular weight (Mn%) and molecular weight distribution of the polymer. A decrease in Mn% is evidence of chain cleavage that can be related to microbial degradation. Nevertheless, just as alterations of tensile resistance, glass transition Temperature, thermal stability and the molecular weight will also change in response to physicochemical processes Finally, none of the other methods described in this section is able to unambiguously prove the occurrence of complete microbial biodegradation, from initial depolymerization to mineralization and biomass assimilation.

Limitations of Studying Fungal Communities

In comparison to bacteria, fungi in the marine realm are understudied and often overlooked. It seems likely that fungi are relevant as saprotrophs in general and may act as plastic degraders, yet this needs to be demonstrated in future studies. However, in comparison to investigating bacterial communities, taxonomic and physiological characterization of (marine) fungi is not as straightforward and standardized methods are generally lacking. Indeed, molecular studies on fungi still encounter classic difficulties and biases related to molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) bias, library preparation bias, sequencing bias, bioinformatics biases and unequal sequencing depth. Perhaps the most hindering factors in molecular studies of fungi are: (i) nucleic acid extraction method bias (ii) marker gene bias when using 18S rRNA or ITS spacer and (iii) primer bias. In addition, also (iv) culture-based methods are hindered by the fact that identification based on morphological features (alone) is difficult, growth conditions are hard to determine and fungi have complex life cycles.

-

(i)

Fungal genomic DNA extraction is less straightforward in comparison to extracting DNA from bacteria. Fungal cell walls are made of chitin making them more robust than a peptidoglycan bacterial cell wall (Fredricks et al., 2005; Shin, 2018). Breaking down fungal cells requires further steps such as the addition of lysing agents (for example, adapting the lysis buffer or adding enzymes such as cutinases) and/or mechanical disruption (e.g., increasing bead-beating steps or introducing freeze-thaw cycles) to increase fungal DNA yields, while maintaining the integrity of the DNA. Furthermore, different fungal strains may require different extraction steps to be added, complicating DNA extraction from the whole fungal community in environmental samples.

-

(ii)

Selection of a reliable marker gene (gene section) is influenced not only by the number of targeted taxa, but also the feasibility of down-stream analysis as this depends on the availability of data stored in publicly available databases. For prokaryotes, several and up to date databases exist for 16S rRNA gene sequences (and are publicly accessible), while far less information is available for 18S rRNA sequences. One of the most commonly used database is SILVA, but while the SILVA ref 138.1 release (Quast et al., 2013) contains 2,052,220 16S rRNA gene sequences (1,983,022 bacterial and 69,198 archaeal sequences), it only contains172,520 18S rRNA gene sequences, of which 30,386 were classified as fungi. SILVA also, hosts a repository of 9329 representative 18S rRNA gene sequences covering all of the fungal kingdom and includes a manually curated alignment, and reference phylogenetic tree (Yarza et al., 2017). An alternative database for the identification of fungi is the ITS sequence database UNITE, but the most recent release (Nilsson et al., 2018) contains a similarly low number of 30,555 fungal sequences. Reich and Labes (2017) reviewed the available molecular ecology tools including their advantages and drawbacks when applied to the community studies of marine fungi. Even when the available number of 18S rRNA gene sequences, ITS sequences and fungal genomes has increased substantially, these numbers stand in stark contrast to the estimated several million fungal species (Nilsson et al., 2015). About 50% of the described fungal species still lack any DNA sequence information in public databases (Xu, 2016). In order to fill the taxonomic marker-related gaps in public databases, it has been suggested to use third-generation sequencing and apply ribosomal tandem repeat sequencing to cover all ribosomal markers for fungi (Wurzbacher et al., 2019).

-

(iii)

Different nuclear ribosomal DNA marker genes are used for the identification of fungal species. However, environmental studies on fungal communities, apply most commonly the ITS and the 18S rRNA marker gene. The ITS region has been proposed as a universal barcode for fungal DNA as it may allow for a better resolution of fungal taxonomy than the 18S rRNA gene overall (Schoch et al., 2012). ITS barcoded sequencing has been successfully applied for both unicellular as well as for filamentous fungi (Vu et al., 2016, 2019). Many ITS targeting primers have been developed in recent years (Martin and Rygiewicz, 2005; Manter and Vivanco, 2007; Toju et al., 2012). However, choosing adequate thresholds for taxonomic assignments in ITS processing pipelines is delicate as the average intraspecific ITS variability is fluctuating (Smith et al., 2007; Simon and Weiß, 2008). For example, 0.2% for A. fumigatus, 3.1% for F. solani and up to 24.2% for the Ascomycota Xylaria hypoxylon (Nilsson et al., 2008). Vu et al. (2016, 2019) suggested that a threshold of 98.41% should be applied for ITS to distinguish between yeast species and a threshold of 99.6% should be applied to discriminate between filamentous fungi. Moreover, within an individual, ITS polymorphism (Alper et al., 2011) and ITS hybrid forms (Sriswasdi et al., 2019) were reported. Consequently, even when using fungal specific primers (ITS), intraspecific variability might not lead to species identification. Use of ITS shows even more limitations when dealing with marine fungi. Indeed, the ITS marker has a higher divergence rate compared to the 18S rRNA marker gene in marine fungal communities where early diverging fungi are abundant, and thus results into low classification success rates for ITS (Nilsson et al., 2019). For example, De Tender et al. (2017) could not assign 28 to 99% of the fungal reads acquired in their study when using ITS. To overcome this issue, it has been suggested to combine multiple marker genes for the molecular identification of the members of marine fungal communities. Banos et al. (2018) suggested to apply a fungi-specific 18S rRNA primers according to different environments, conditions or goals. This raises a new issue when using fungal specific ITS/18S primers, as different sets may overestimate some taxa and, in some cases, not target any fungus at all. By using a long read sequencing approach multiple marker genes can be retrieved at the same time, which allows for better taxonomic resolution (Heeger et al., 2018). Studies focusing on fungi colonizing plastic debris are scarce and the use of different marker genes and short read sequencing technology (Table 1) makes comparison between different datasets difficult. Unfortunately, no credible hypotheses on the presence or absence of a core fungal community living on plastic can be formulated yet.

-

(iv)

Culture-based methods are time-consuming and the culture media will have a selective effect on fungal growth. There is no specific medium for marine fungi available to date, but only adaptions of media selective for terrestrial fungi. The morphological diversity associated with different developmental stages of the same species, complicates the identification of fungal isolates (Xu, 2016). Nevertheless, only culturing of strains isolated from environmental samples enables in-depth investigation of their physiological and metabolic capabilities. Overy et al. (2019) published a toolkit of best practices for the culturing and isolation of marine fungi. We thus argue that combining molecular and isolation/culturing effort is the best way to evaluate interactions between fungal communities and plastics in marine environments.

Conclusion-Outlook

This mini-review summarizes the current knowledge on marine fungi – PMD interactions; i.e., the ability of fungi to colonize plastics and specific strains known to degrade plastics as well as the methodological advances and difficulties in studying fungi – PMD interactions. Investigating the interaction of marine fungi and PMD is an emerging and exciting field of research when considering the high potential for plastic degradation of several fungal strains. Yet, for a well-constrained appraisal of marine fungi and their role as plastic degraders, several knowledge gaps still need to be filled. Firstly, a more general and fundamental understanding of fungi in the marine environment needs to be achieved by addressing fungal prevalence and diversity in the ocean. By using new molecular markers, the available sequence databases could be expanded for future classification of fungi detected on plastic polymers and to classify currently unclassified fungi. To address the biodegradation potential of fungi, comparable detection methods should be used to enable comparison between different strains, polymers and studies. Also, we suggest applying several complementary techniques for assessing biodegradation, particularly if the used techniques might cause false positives. Once fungal species degrading plastic in the marine environment are identified, future research should address the enzymatic potential of these fungi, which might then serve biotechnological applications for plastic waste bioremediation.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

EZ wrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. HN supervised the project. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was financed through the European Research Council (ERC-CoG Grant No. 772923, project VORTEX).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Albertsson A. (1978). Biodegradation of synthetic polymers. II. A limited microbial conversion of 14C in polyethylene to 14CO2 by some soil fungi.J. Appl. Poly. Sci.223419–3433.

2

Albertsson A. Baanhidi Z. Beyer-Ericsson L. (1978). Biodegradation of synthetic polymers. III. The liberation of 14CO2 by molds like Fusarium redolens from 14C labeled pulverized high-density polyethylene.J. Appl. Poly. Sci.223435–3447.

3

Albertsson A.-C. (1980). The shape of the biodegradation curve for low and high density polyethenes in prolonged series of experiments.Eur. Poly. J.16623–630. 10.1016/0014-3057(80)90100-7

4

Albertsson A.-C. Karlsson S. (1990). The influence of biotic and abiotic environments on the degradation of polyethylene.Prog. Poly. Sci.15177–192. 10.1016/0079-6700(90)90027-X

5

Alias S. A. Zainuddin N. Jones E. G. (2010). Biodiversity of marine fungi in Malaysian mangroves.Botan. Mar.53545–554.

6

Almond J. Sugumaar P. Wenzel M. N. Hill G. Wallis C. (2020). Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy.e-Polymers20369–381. 10.1515/epoly-2020-0041

7

Alper I. Frenette M. Labrie S. (2011). Ribosomal DNA polymorphisms in the yeast Geotrichum candidum.Fung. Biol.1151259–1269. 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.09.002

8

Alshehrei F. (2017). Biodegradation of Low Density Polyethylene by Fungi Isolated from Red Sea Water.Internat. J. Curr. Microb. Appl. Sci.61703–1709. 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.608.204

9

Álvarez-Barragán J. Domínguez-Malfavón L. Vargas-Suárez M. González-Hernández R. Aguilar-Osorio G. Loza-Tavera H. (2016). Biodegradative Activities of Selected Environmental Fungi on a Polyester Polyurethane Varnish and Polyether Polyurethane Foams.Appl. Environ. Microbiol.825225–5235. 10.1128/AEM.01344-16

10

Amaral-Zettler L. A. Zettler E. R. Slikas B. Boyd G. D. Melvin D. W. Morrall C. E. et al (2015). The biogeography of the Plastisphere: implications for policy.Front. Ecol. Env.13541–546. 10.1890/150017

11

Ameen F. Moslem M. Hadi S. Al-Sabri A. E. (2015). Biodegradation of Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE) by Mangrove Fungi from the Red Sea Coast.Prog. Rubber, Plast. Recycl. Technol.31125–143. 10.1177/147776061503100204

12

Amend A. Burgaud G. Cunliffe M. Edgcomb V. P. Ettinger C. L. Gutiérrez M. H. et al (2019). Fungi in the Marine Environment: Open Questions and Unsolved Problems.mBio10e1189–e1118. 10.1128/mBio.01189-18

13

Amobonye A. Bhagwat P. Singh S. Pillai S. (2021). Plastic biodegradation: Frontline microbes and their enzymes.Sci. Total Env.759:143536. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143536

14

Balabanova L. Slepchenko L. Son O. Tekutyeva L. (2018). Biotechnology Potential of Marine Fungi Degrading Plant and Algae Polymeric Substrates.Front. Microb.9:1527. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01527

15

Balasubramanian V. Natarajan K. Rajeshkannan V. Perumal P. (2014). Enhancement of in vitro high-density polyethylene (HDPE) degradation by physical, chemical, and biological treatments.Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.2112549–12562. 10.1007/s11356-014-3191-2

16

Banos S. Gysi D. M. Richter-Heitmann T. Glöckner F. O. Boersma M. Wiltshire K. H. et al (2020). Seasonal Dynamics of Pelagic Mycoplanktonic Communities: Interplay of Taxon Abundance, Temporal Occurrence, and Biotic Interactions.Front. Microb.11:1305. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01305

17

Banos S. Lentendu G. Kopf A. Wubet T. Glöckner F. O. Reich M. (2018). A comprehensive fungi-specific 18S rRNA gene sequence primer toolkit suited for diverse research issues and sequencing platforms.BMC Microbiol.18:190. 10.1186/s12866-018-1331-4

18

Berbee M. L. James T. Y. Strullu-Derrien C. (2017). Early Diverging Fungi: Diversity and Impact at the Dawn of Terrestrial Life.Annu. Rev. Microbiol.7141–60. 10.1146/annurev-micro-030117-020324

19

Berbee M. L. Strullu-Derrien C. Delaux P.-M. Strother P. K. Kenrick P. Selosse M.-A. et al (2020). Genomic and fossil windows into the secret lives of the most ancient fungi.Nature Rev. Microb.18717–730. 10.1038/s41579-020-0426-8

20

Bioplastics Market Data update (2020). European Bioplastics. Available online at: https://docs.european-bioplastics.org/conference/Report_Bioplastics_Market_Data_2020_short_version.pdf [Accessed February 3, 2021].

21

Bochdansky A. B. Clouse M. A. Herndl G. J. (2017). Eukaryotic microbes, principally fungi and labyrinthulomycetes, dominate biomass on bathypelagic marine snow.ISME J.11362–373. 10.1038/ismej.2016.113

22

Bonhomme S. Cuer A. Delort A.-M. Lemaire J. Sancelme M. Scott G. (2003). Environmental biodegradation of polyethylene.Poly. Degrad. Stab.81441–452. 10.1016/S0141-3910(03)00129-0

23

Boyce K. J. Andrianopoulos A. (2015). Fungal dimorphism: the switch from hyphae to yeast is a specialized morphogenetic adaptation allowing colonization of a host.FEMS Microbiol. Rev.39797–811. 10.1093/femsre/fuv035

24

Brunner I. Fischer M. Rüthi J. Stierli B. Frey B. (2018). Ability of fungi isolated from plastic debris floating in the shoreline of a lake to degrade plastics.PLoS One13:e0202047. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202047

25

Bucher V. Hyde K. Pointing S. Reddy C. (2004). Production of wood decay enzymes, mass loss and lignin solubilization in wood by marine ascomycetes and their anamorphs.Fungal Div.151–14.

26

Buswell J. A. (2001). “Fungal biodegradation of chlorinated monoaromatics and BTEX compounds,” in Fungi in BioremediationBritish Mycological Society Symposia, ed.GaddG. M. (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 113–135. 10.1017/CBO9780511541780.007

27

Cathrine S. J. Raghukumar C. (2009). Anaerobic denitrification in fungi from the coastal marine sediments off Goa. India.Mycolog. Res.113100–109.

28

Cerniglia C. E. Sutherland J. B. (2001). “Bioremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by ligninolytic and non-ligninolytic fungi,” in Fungi in BioremediationBritish Mycological Society Symposia, ed.GaddG. M. (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 136–187. 10.1017/CBO9780511541780.008

29

Chae Y. An Y.-J. (2018). Current research trends on plastic pollution and ecological impacts on the soil ecosystem: A review.Env. Pollut.240387–395. 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.008

30

Chang Y. Wang S. Sekimoto S. Aerts A. L. Choi C. Clum A. et al (2015). Phylogenomic Analyses Indicate that Early Fungi Evolved Digesting Cell Walls of Algal Ancestors of Land Plants.Genome Biol. Evol.71590–1601. 10.1093/gbe/evv090

31

Comeau A. M. Vincent W. F. Bernier L. Lovejoy C. (2016). Novel chytrid lineages dominate fungal sequences in diverse marine and freshwater habitats.Sci. Rep.6:30120. 10.1038/srep30120

32

Cózar A. Sanz-Martín M. Martí E. González-Gordillo J. I Ubeda B. Gálvez J. et al (2015). Plastic Accumulation in the Mediterranean Sea.PLoS One10:e0121762. 10.1371/journal.pone.0121762

33

Das M. P. Kumar S. (2014). Microbial deterioration of low density polyethylene by Aspergillus and Fusarium sp.Int. J. Chem. Tech. Res.6299–305.

34

de Carvalho C. C. C. R. (2018). Marine Biofilms: A Successful Microbial Strategy With Economic Implications.Front. Mar. Sci.5:126. 10.3389/fmars.2018.00126

35

De Tender C. Devriese L. I. Haegeman A. Maes S. Vangeyte J. Cattrijsse A. et al (2017). Temporal Dynamics of Bacterial and Fungal Colonization on Plastic Debris in the North Sea.Environ. Sci. Technol.517350–7360. 10.1021/acs.est.7b00697

36

Debroas D. Mone A. Ter Halle A. (2017). Plastics in the North Atlantic garbage patch: A boat-microbe for hitchhikers and plastic degraders.Sci. Total Env.599–6001222–1232. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.059

37

Deepika S. Madhuri R. J. (2015). Biodegradation of low density polyethylene by micro-organisms from garbage soil.J. Exp. Biol. Agricult. Sci.315–21.

38

Deguchi T. Kakezawa M. Nishida T. (1997). Nylon biodegradation by lignin-degrading fungi.Appl. Environ. Microbiol.63329–331. 10.1128/aem.63.1.329-331.1997

39

Du Z.-Y. Zienkiewicz K. Vande Pol N. Ostrom N. E. Benning C. Bonito G. M. (2019). Algal-fungal symbiosis leads to photosynthetic mycelium.eLife8:e47815. 10.7554/eLife.47815

40

Dudek K. L. Cruz B. N. Polidoro B. Neuer S. (2020). Microbial colonization of microplastics in the Caribbean Sea.Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett.55–17. 10.1002/lol2.10141

41

Dussud C. Hudec C. George M. Fabre P. Higgs P. Bruzaud S. et al (2018). Colonization of Non-biodegradable and Biodegradable Plastics by Marine Microorganisms.Front. Microbiol.9:1571. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01571

42

Eich A. Mildenberger T. Laforsch C. Weber M. (2015). Biofilm and Diatom Succession on Polyethylene (PE) and Biodegradable Plastic Bags in Two Marine Habitats: Early Signs of Degradation in the Pelagic and Benthic Zone?PLoS One10:e0137201. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137201

43

Eriksen M. Lebreton L. C. M. Carson H. S. Thiel M. Moore C. J. Borerro J. C. et al (2014). Plastic Pollution in the World’s Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea.PLoS One9:e111913. 10.1371/journal.pone.0111913

44

Erni-Cassola G. Zadjelovic V. Gibson M. I. Christie-Oleza J. A. (2019). Distribution of plastic polymer types in the marine environment; A meta-analysis.J. Hazard. Mater.369691–698. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.02.067

45

Esmaeili A. Pourbabaee A. A. Alikhani H. A. Shabani F. Esmaeili E. (2013). Biodegradation of Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) by Mixed Culture of Lysinibacillus xylanilyticus and Aspergillus niger in Soil.PLoS One8:e71720. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071720

46

Falih A. Wainwright M. (1995). Nitrification in vitro by a range of filamentous fungi and yeasts.Lett. Appl. Microb.2118–19.

47

Filip Z. (1979). Polyurethane as the sole nutrient source for Aspergillus niger and Cladosporium herbarum.Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.7277–280. 10.1007/BF00498022

48

Fredricks D. N. Smith C. Meier A. (2005). Comparison of six DNA extraction methods for recovery of fungal DNA as assessed by quantitative PCR.J. Clin. Microbiol.435122–5128. 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5122-5128.2005

49

Friedrich J. Zalar P. Mohorčič M. Klun U. Kržan A. (2007). Ability of fungi to degrade synthetic polymer nylon-6.Chemosphere672089–2095. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.09.038

50

Gabaldón T. (2020). Hybridization and the origin of new yeast lineages.FEMS Yeast Res.20:40. 10.1093/femsyr/foaa040

51

Gadd G. M. (2004). Mycotransformation of organic and inorganic substrates.Mycologist1860–70. 10.1017/S0269915X04002022

52

Galgani F. Hanke G. Maes T. (2015). ““Global Distribution, Composition and Abundance of Marine Litter,”,” in Marine Anthropogenic Litter, edsBergmannM.GutowL.KlagesM. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 29–56. 10.1007/978-3-319-16510-3_2

53

Geyer R. Jambeck J. R. Law K. L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made.Sci. Adv.3:e1700782. 10.1126/sciadv.1700782

54

Gladfelter A. S. James T. Y. Amend A. S. (2019). Marine fungi.Curr. Biol.29R191–R195. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.009

55

Gruninger R. J. Puniya A. K. Callaghan T. M. Edwards J. E. Youssef N. Dagar S. S. et al (2014). Anaerobic fungi (phylum Neocallimastigomycota): advances in understanding their taxonomy, life cycle, ecology, role and biotechnological potential.FEMS Microb. Ecol.901–17.

56

Guillet J. E. Regulski T. W. McAneney T. B. (1974). Biodegradability of photodegraded polymers. II. Tracer studies of biooxidation of Ecolyte PS polystyrene.Env. Sci. Tech.8923–925.

57

Hassett B. T. Borrego E. J. Vonnahme T. R. Rämä T. Kolomiets M. V. Gradinger R. (2019). Arctic marine fungi: biomass, functional genes, and putative ecological roles.ISME J.131484–1496. 10.1038/s41396-019-0368-1

58

Hawksworth D. L. Lücking R. (2017). Fungal Diversity Revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 Million Species.Microbiol. Spectr.2017:5.

59