Abstract

Small yellow croaker Larimichthys polyactis is an important commercial fish species; however, industrial-scale fishing has largely contributed to the changes in its biological characteristics, such as individual miniaturization, faster growth, and younger average age. Robust understanding of the pivotal life history of L. polyactis, a typical oceanodromous species, is needed for its conservation and restoration. However, L. polyactis fidelity to natal or spawning sites is not well understood and, at present, there is no effective management strategy to guarantee the sustainable exploitation of L. polyactis. This study used laser ablation inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry to analyse the elemental composition of otoliths from 60 adult yellow croakers caught in the southern Yellow Sea, including two spawning groups with 1- and 2-year-old fish (S1 and S2, respectively) sampled close to China and one overwintering group including two-year-old fish (O2) sampled close to South Korea. The ratios of elements (Li, Na, Sr, and Ba) to Ca in the otolith core zones were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in those of the year one (Y1) and year two (Y2) annual rings, but there were no significant differences in the elemental ratios between the Y1 and Y2 zones. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the elemental otolith signatures of the core, Y1, and Y2 zones in the three groups revealed two distinct clusters (cluster 1: S1-core, S2-core, and O2-core zones; cluster 2: S2–Y1, O2–Y1, S2–Y2, and O2–Y2 zones) and one zone (S1–Y1), suggesting spawning-site fidelity and natal-site fidelity uncertainty, especially considering the dispersal by current in prolonged period (50 h) from fertilized eggs to hatching and internal effect, such as yolk sac and maternal effect. Furthermore, these results indicated that the S2 and O2 groups could represent the same population, suggesting a stable migratory route for L. polyactis in Chinese and South Korean waters, whereas the S1 group could represent another population. This suggests the possibility a mixed L. polyactis population in the southern Yellow Sea. Characterization L. polyactis spawning-site fidelity is a crucial step toward linking spawning-site fidelity of this overexploited species with thorough conservation and management strategies.

Introduction

Migration is a fundamental behavioral characteristic of many animal species (Alo et al., 2020). All animals demonstrate some types of movement during their life span; among them, two have captivated the attention of scientists and non-experts: natal-site philopatry (i.e., return to birthplace) and spawning-site philopatry [i.e., return to a previous spawning site (Dingle and Drake, 2007; Chen et al., 2020)]. From an evolutionary point of view, natal philopatry enables isolation of specific breeding populations (“stocks”) and provides potential for local adaptation in order to increase reproductive capacity, decrease the potential of recruitment failure, and stabilize the ability to adjust to environmental change and exploitation (Hilborn et al., 2003; Sadovy and Domeier, 2005). However, there are consequences to natal-site philopatry, including the risk of inbreeding depression (Miller et al., 2001) and increased competition (Sandercock, 1991; Di Franco et al., 2012). The phenomenon opposite to philopatry is dispersal, which is the migration away from the birthplace prior to reproduction (Mora and Sale, 2002). High rates of dispersal have been documented when the chance of inbreeding and population density are increased (Cote et al., 2010), suggesting that dispersal might counterbalance some of the negative consequences of natal-site philopatry for the population fitness. Therefore, reproductive fidelity in mobile marine species may regulate the spatial population structure and connectivity (Hastings and Botsford, 2006). The fidelity to natal or spawning sites can effectively be used to make informed decisions about conservation strategies, especially regarding future marine protected areas (MPAs), which, ultimately, should improve the management and conservation of marine fishery resources (Bardbury et al., 2008; Di Franco et al., 2012; Tripp et al., 2020).

Determination of natal-site fidelity is quite challenging, and requires the tracking of fish from eggs until breeding (Ovenden, 2013). During the past 30 years, a range of tagging techniques have been reported, which can be categorized as external (Florin and Franzén, 2010; Lowerre-Barbieri et al., 2013), implanted (Mellish et al., 2007), and natural (Reis-Santos et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020; Stone et al., 2020). However, external and implanted tagging can have negative effects on health, reproduction, and survival; furthermore, they are costly and time-consuming, and may not be effective for small-sized and long-distance migratory fish because of the low recapture rate (Bishop et al., 2010; Humston et al., 2010). Recent technological advances have enabled the potential of distinct biological hard tissues as natural tags; among them, the elemental composition of otoliths has been used as an important marker for tracking movement and determining the connectivity patterns in fish species (Elsdon and Gillanders, 2003; Tanner et al., 2016; Honig et al., 2020; Martinho et al., 2020). Otoliths grow continuously over the lifespan in daily and annular rhythms and are not reabsorbed (Schulz-Mirbach et al., 2019); therefore, they have been widely used as indicators of fish age (Campana, 1999). Also, a substantial number of elements (e.g., calcium, Ca; strontium, Sr; barium, Ba; sodium, Na; magnesium, Mg; magnesium, Mn; potassium, K; lead, Pb; zinc, Zn), are co-precipitated in the otolith growth increments as the fish grows (Campana, 1999). Unfortunately, as otolith chemistry varies over time with respect to salinity, temperature, and ontogenetic stage, as well as ambient water occupied (Barnes and Gillanders, 2013; Taddese et al., 2019), single-element profiles may not be a reliable means of spatially tracking individuals (Kraus and Secor, 2004). Thus, the microchemical composition of equivalent otolith parts can serve as a natural marker to determine fish origin, reconstruct migration pathways, and discriminate among fish groups (Gillanders, 2002; Kraus and Secor, 2004; Svedäng et al., 2007; Munch and Clarke, 2008; Thorisson et al., 2010; Engstedt et al., 2013).

Small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) is an important commercial fish species endemic to the Northwest Pacific, particularly coastal waters of the East China, Yellow, and Bohai Sea between China and the Korean Peninsula (Lin, 1987). L. polyactis is an iteroparous species, which starts spawning at the age of 1 year, as evidenced by histological analyses of female individuals (Xie et al., 2021). For decades, L. polyactis has been an important source of seafood for local markets in China, Japan, and South Korea (Ma et al., 2020; Szuwalski et al., 2020); however, environmental deterioration and overfishing have led to a major decline in its population since the 1970s (Li et al., 2011). From 2000, the global capture production of L. polyactis, mainly by China and South Korea, has been increasing, reaching a maximum of 4.58 × 105 t in 2010 (Fishbase, 2019). Owing to intense fishing pressure, the current population of L. polyactis is characterized by individual miniaturization, decreased asymptotic length and weight, faster growth, and younger average age (Shan et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2019). Moreover, because of high fishing pressure L. polyactis has shifted its spawning grounds from nearshore to offshore waters (Lin et al., 2008). To avoid L. polyactis population collapse, such as happened to its sister species the large yellow croaker Larimichthys crocea, much stricter conservation measures based on scientific data must be implemented (Choi and Kim, 2020; Li et al., 2020).

Larimichthys polyactis is a typical oceanodromous fish that is born in estuaries or nearshore areas, grows and matures in nearby coastal waters, and migrates offshore to overwintering grounds (Xiong et al., 2017). Although progress has been made regarding the detailed migratory cycle of L. polyactis (Xu and Chen, 2009; Xiong et al., 2017; Song et al., 2022), understanding of its natal- or spawning-site fidelity is limited, hampering the development and implementation of appropriate conservation and resource management strategies for this overexploited and highly targeted species. Based on the morphological variations and migratory routes of L. polyactis, three wild populations have been suggested to exist in the China Seas: and the East China Sea population, the southern Yellow Sea population, and the northern Yellow/Bohai Sea population (Lin, 1987; Zhang et al., 2014). The southern Yellow Sea population has its overwintering grounds in the area defined by Sino-Korean fisheries agreements and in the exclusive South Korean economic zone (Lin, 1987; Baik et al., 2004; Han et al., 2020); however, its natal and spawning sites are uncertain. Therefore, it is critical to know whether L. polyactis returns to its natal and spawning sites to determine rational fishing quotas in China and South Korea (Xue, 2005).

Larimichthys polyactis analyzed in this study is an iteroparous species. Its spawning period in Chinese waters differs slightly from south to north, with the spawning peak of L. polyactis in the southern Yellow Sea being in April (Lim et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2018). Therefore, specimens of the spawning group were all sampled in April; the gonadosomatic indices (GSI) were all at stages V or VI, confirming the spawning period. The deposition of elements in the otoliths of L. polyactis exhibits annual periodicity (Li et al., 2013; Zhan et al., 2016; Zhang T. T. et al., 2019; Song et al., 2022). Accordingly, the otolith elemental composition in the equivalent parts of the otolith can be used as a biological tracer to examine natal- and spawning-site fidelity. Therefore, laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICPMS) was applied to the spawning group and overwintering group equivalent parts in sagittal otoliths of L. polyactis. The aim of this study was to examine the connectivity between L. polyactis spawning groups from China nearshore areas and overwintering groups from South Korea offshore areas based on otolith chemical signatures, which are metabolically stable, and thus to allow accurate stock classification. We also assessed the potential use of otolith element composition as a natural tag to examine natal- and spawning-site fidelity of L. polyactis in the southern Yellow Sea. This information should help to improve fishery management, including the development of appropriate fishing regulations and rational quotas for China and South Korea.

Materials and Methods

Sampling and Laboratory Procedures

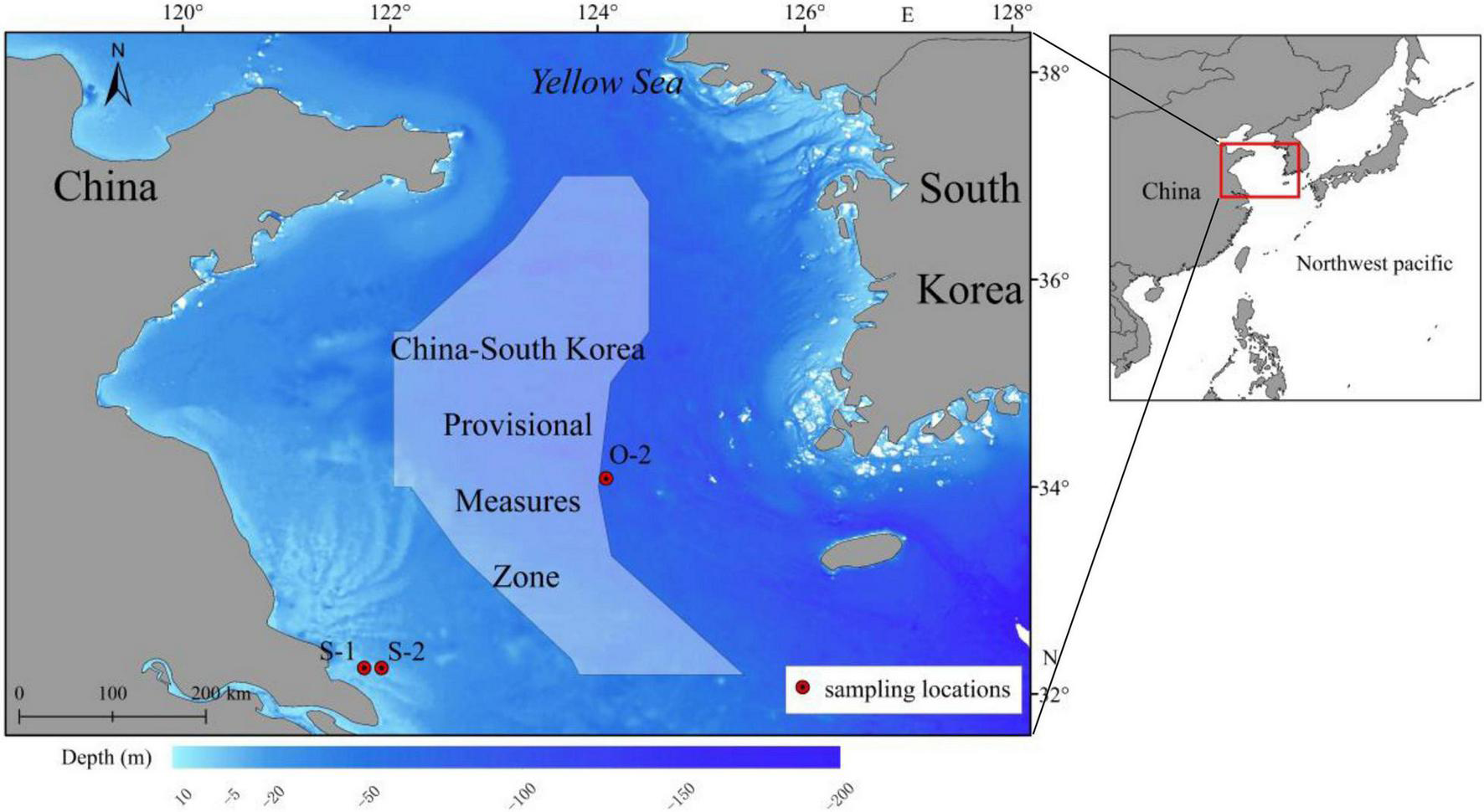

A total of 60 adult L. polyactis fish were collected from spawning grounds (close to China) and overwintering grounds (close to South Korea) in the Southern Yellow Sea (Figure 1); the samples included 20 1-year-old spawning individuals (S1) obtained in April 2017, 20 2-year-old spawning individuals (S2) obtained in April 2018, and 20 2-year-old overwintering individuals (O2) obtained in November 2018 (Table 1). Samples of S1/S2 and O2 fish were randomly collected from the catches of commercial vessels, which used anchored stow nets (cod-end mesh size, 25 mm) and gill nets (mesh size, 50 mm), respectively. The samples of fish were immediately refrigerated and transported to the laboratory. Fish body length, body weight, and sex were recorded in sequence. The nearest body length and weight are 0.1 mm and 0.1 g, respectively. Then, the gonadosomatic index (GSI) was determined by visual examination to confirm the assignment of L. polyactis to spawning groups (GSI: stage V and VI; Lim et al., 2010). Subsequently, sagittal otoliths were extracted, dried, weighed, and stored in plastic tubes; the numbers of seasonal growth rings (annulae) in the otoliths were counted to confirm fish age, and outlier specimens were excluded from further analysis. Detailed information on the samples used for otolith microchemistry analysis is presented in Table 1.

FIGURE 1

Map showing L. polyactis sampling sites in the southern Yellow Sea and the provisional measures zone under the China-South Korea fishery agreement.

TABLE 1

| Sampling site | Site code | Sampling time | Sample size (n) | Body length, mm (mean ± SD) | Age (years) |

| South Yellow Sea nearshore zone | S1 | April 2017 | 20 | 104.4 ± 6.0 | 1+ |

| S2 | April 2018 | 20 | 129.2 ± 9.8 | 2+ | |

| South Yellow Sea offshore zone | O2 | November 2018 | 20 | 145.5 ± 4.0 | 2+ |

Characteristics of L. polyactis populations analysed for otolith microchemistry.

Otolith Elemental Analysis

Left sagittal otoliths were embedded in epoxy resin (Epofix; Struers, Copenhagen, Denmark), mounted on petrographic slides, sectioned by grinding in the sagittal plane on both surfaces with grit silicon carbide paper (to reveal the nucleus, daily growth increments), and annual growth increments, and further polished with 0.3 μm Al2O3-embedded lapping paper on an automated polishing wheel (Labopol-35, Struers, Copenhagen, Denmark) to remove major scratches. After final polishing, otoliths slides were sonicated in an ultrasonic cleaning bath for 5 min, rinsed with deionized water for 6 times, and dried at 38°C overnight for chemical analysis.

Elemental analysis of L. polyactis otoliths was performed using laser ablation inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS; Jiang et al., 2016) in an NW213 laser ablation module (New Wave Research, Fremont, CA, United States) with an Agilent 7500ce inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, United States). The laser was operated at a wavelength of 213 nm, pulse rate of 10 Hz, high voltage of 10 kV, and energy density of 12.58 J/cm2. To assess natal- and spawning-site fidelity, ablated spots of 20 μm in diameter were located in the core and annual rings with a dwell time of 5 s (Figure 2). The numbers of ablated spots in the core and annual rings were 1 and 3, respectively, allowing for more reasonable and accurate elemental information representing the environment of natal and spawning site. And, the three spots on annuals were ablated on the front, middle, and back of the annual ring with 20 μm interval. The ablated material was transported from the laser unit to ICP mass spectrometer using a mixture of argon and helium gases. Two standard samples, MACS-3 (United States Geological Survey, Reston, VA, United States) and NIST612 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, United States), were analyzed at the beginning and end of each sampling session (10 samples). Limits of detection (LOD) were determined based on 100 s background counts at the beginning and end, and the relative standard deviations (%) were calculated based on repeated measurements of a standard sample to determine the precision accuracy for each element. The results of elemental concentrations are expressed as the ratios of six elements (7Li, 23Na, 57Fe, 59Co, 88Sr, and 138Ba) to Ca.

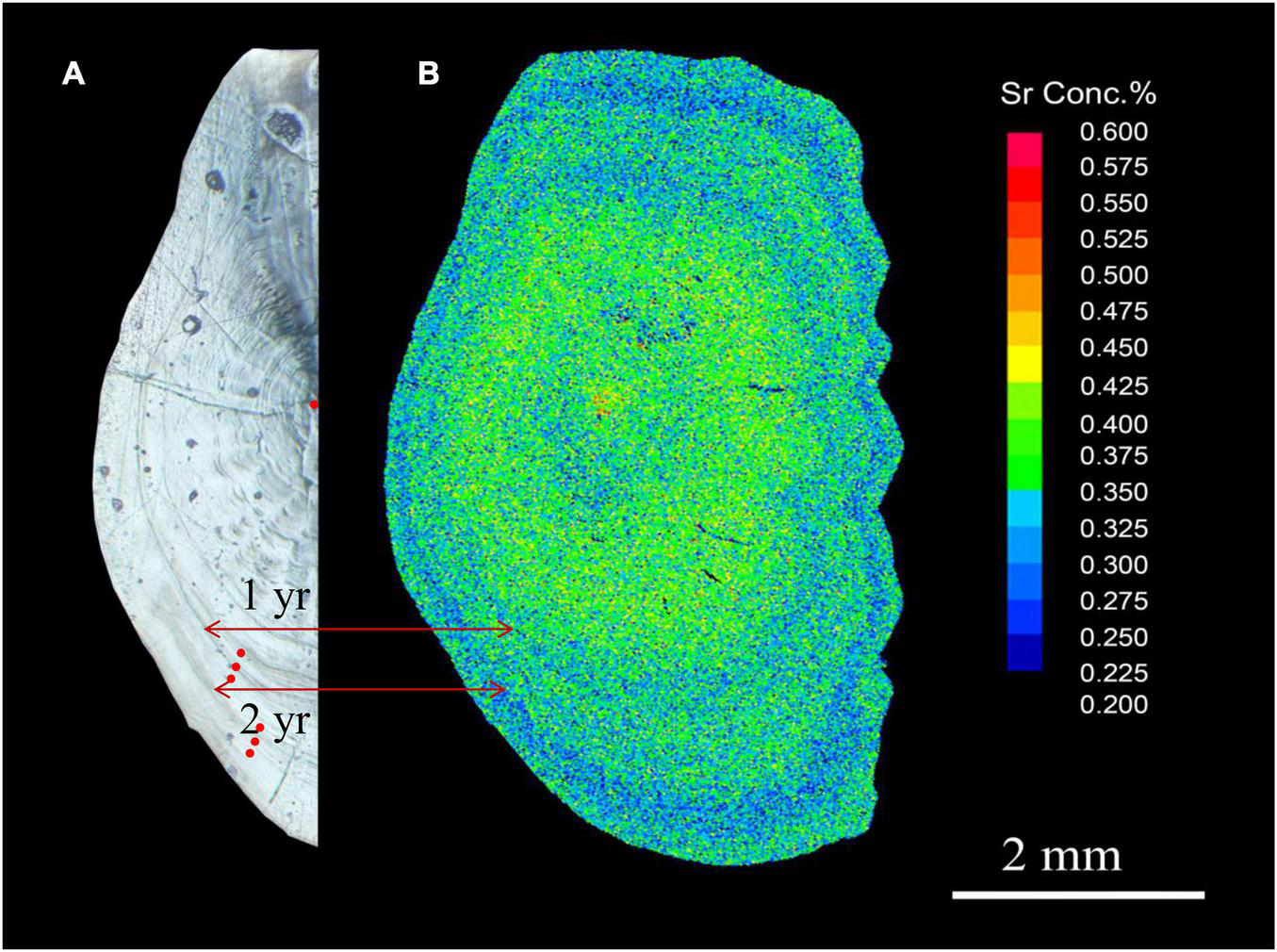

FIGURE 2

Representative images of a sagittal section through the core of an L. polyactis otolith. (A) Otolith morphology (light microscopy). Red dots indicate the location of ablated spots in the core and annual rings; (B) Sr content (electron probe microanalysis).

Larimichthys polyactis can reach sexual maturity after 1 year (Lim et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2021), and fish of the S1 and S2 groups were believed to be in the spawning period. Therefore, the otoliths of the S1 group were analysed for the chemical composition of the core and the first annual ring (Y1) reflecting the local environment of the natal site and the first spawning site, respectively, and those of the S2 and O2 groups were in addition analysed for the composition of the second annual ring (Y2). The reliability of the described analysis could be illustrated by comparing the X-ray intensity map of Sr content and the light microscopy image of an L. polyactis otolith (Figure 2), which showed that low Sr (blue) regions, which correspond to the spawning period in coastal waters, matched the annual rings (Elsdon and Gillanders, 2003). These results indicat that combined with the sampling time and migratory patterns of L. polyactis (Lin et al., 2018), the ablation spots of the core and annual rings accurately represent the natal and spawning period environments, respectively.

Data Analysis

As the data did not fully meet homogeneity of variance/covariance and multivariate parametric assumptions of normality, we used methods that were based on relaxed assumptions or did not require them. Kruskal–Wallis tests was used to determine whether the elemental ratios of the core and Y1 ring differed among the S1, S2, and O2 groups. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to determine the differences in Y2 ring composition between the S2 and O2 groups. Canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) with jackknife cross-validation (Amano et al., 2018) was carried out to assess the utility of element-to-Ca ratios in different ablation levels as a tag for L. polyactis stocks. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to evaluate the potential of employing the element-to-Ca ratio in otoliths to discriminate between ablated zones in otoliths. The data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance of difference. All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics (V23.0) software.

Results

Otolith Geochemistry

Otoliths were isolated from L. polyactis (S1, S2, and O2 groups) captured in the southern Yellow Sea. In total, 242 ablated spots were analyzed with a maximum of 7 per otolith. For the following elements, the detected concentrations in otoliths were above the LODs (mmol/mol): Li (2.53 × 10–3), Na (3.33 × 10–1), Fe (4.83 × 10–2), Co (5.46 × 10–4), Sr (1.63 × 10–4), and Ba (1.63 × 10–4). The analytical accuracy of the standards across all samples was high for the six elements with relative standard deviations ranging from 2.24 (Sr) to 9.27 (Co).

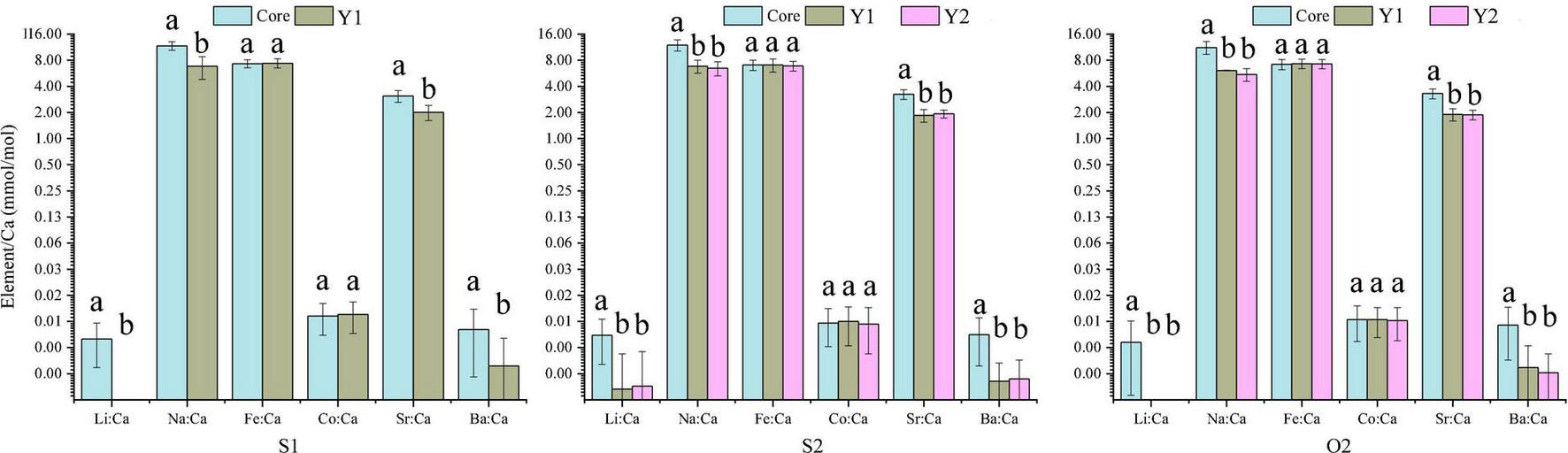

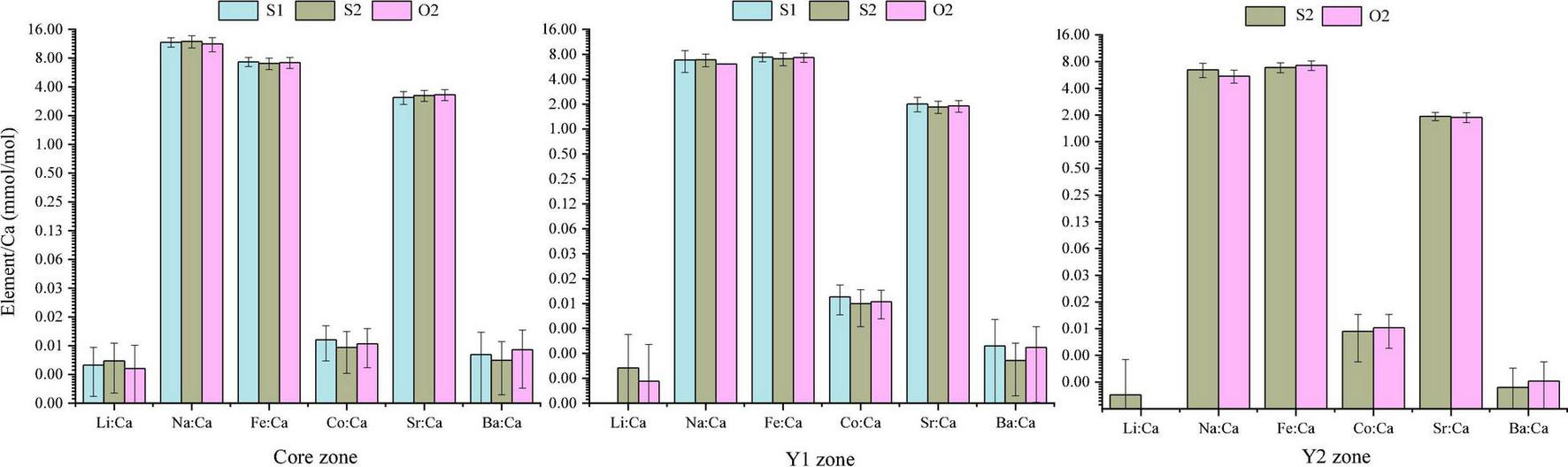

The 60 specimens of L. polyactis from the S1, S2, and O2 groups shared a common feature: the Li:Ca, Na:Ca, Sr:Ca, and Ba:Ca ratios in the core zone were significantly higher than those in the Y1 and Y2 zones (P < 0.05; Figure 3). No significant differences between/among the same ablated zone were observed among the elemental ratios of three sampling groups (P > 0.05) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3

Mean element-to-Ca ratios (mmol/mol) in the otolith’s core zone and Y1 and Y2 rings of three L. polyactis age groups. Different low-case letters indicate significant differences between growth zones (P < 0.05).

FIGURE 4

Comparison of mean element-to-Ca ratios (mmol/mol) in otolith growth zones of L. polyactis from different groups.

Canonical Discriminant Analysis of Element-to-Ca Ratios

Overall, natal- or spawning-site fidelity was reflected in the assignment to the actual zones of per otolith. According to CDA with jackknife cross-validation, the percentages of good assignment of different ablated zones to their actual zones were 95% for S1, 71.57% for S2, and 76.05% for O2 group (Table 2). The percentage of assignment of the core zone to its actual zone was high (95–100%) among the three sampling groups, but that of the Y1 and Y2 zones was rather low (50–70%), and one was frequently mistaken for the other (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Sampling group | Original ablated zone | Predicted ablated zone |

Sample number | Correct prediction | Total correct prediction | ||

| Core | Y1 | Y2 | |||||

| S1 | Core | 19 | 1 | 20 | 95.00% | 95.00% | |

| Y1 | 1 | 19 | 20 | 95.00% | |||

| S2 | Core | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 100% | 71.57% |

| Y1 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 50.00% | ||

| Y2 | 0 | 6 | 11 | 17 | 64.71% | ||

| O2 | Core | 19 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 95.00% | 76.05% |

| Y1 | 0 | 14 | 6 | 20 | 70.00% | ||

| Y2 | 0 | 7 | 12 | 19 | 63.16% | ||

Re-classification matrix constructed based on CDA with jackknife cross-validation of element-to-Ca ratios in otolith zones of the S1, S2, and O2 L. polyactis groups.

Bold numbers indicate individual assignment to capturing locations.

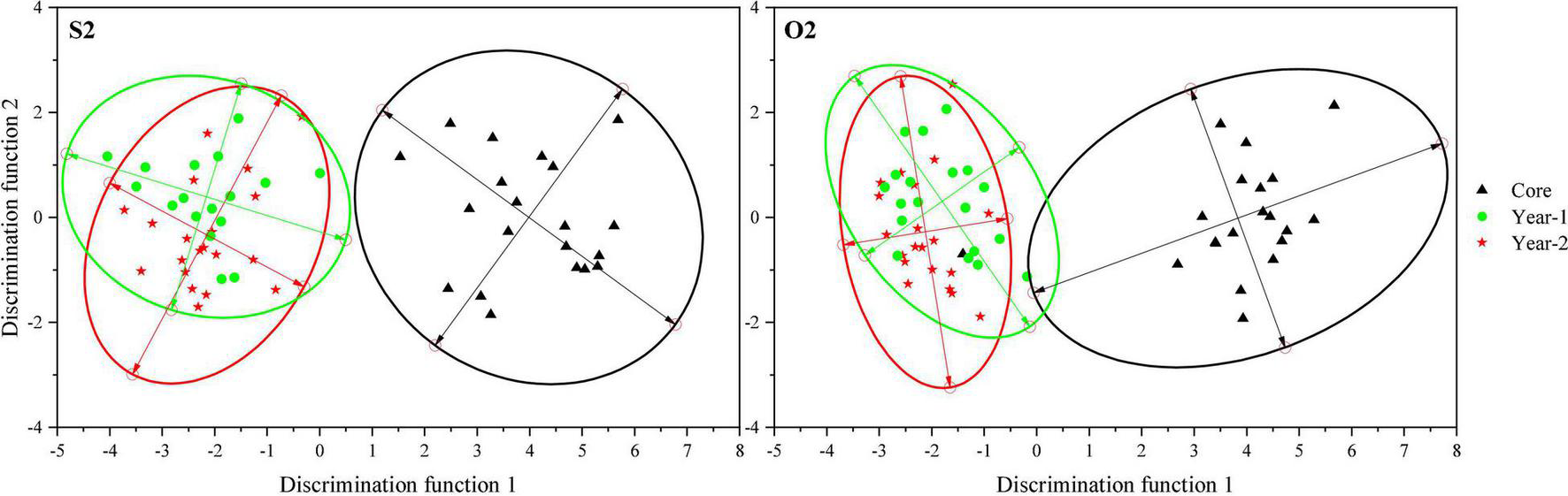

Canonical discriminant analysis provided clear separation between the core and Y1/Y2 zones in the S2 and O2 groups, which formed two distinct clusters: the natal environment cluster represented by the core zone and the spawning environment cluster represented by the Y1 and Y2 zones (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

Scatter plots showing the separation of the core, Y1, and Y2 otolith zones in the S2 and O2 groups (based on CDA). Ellipses indicate the mean 95% confidence level contours for each zone.

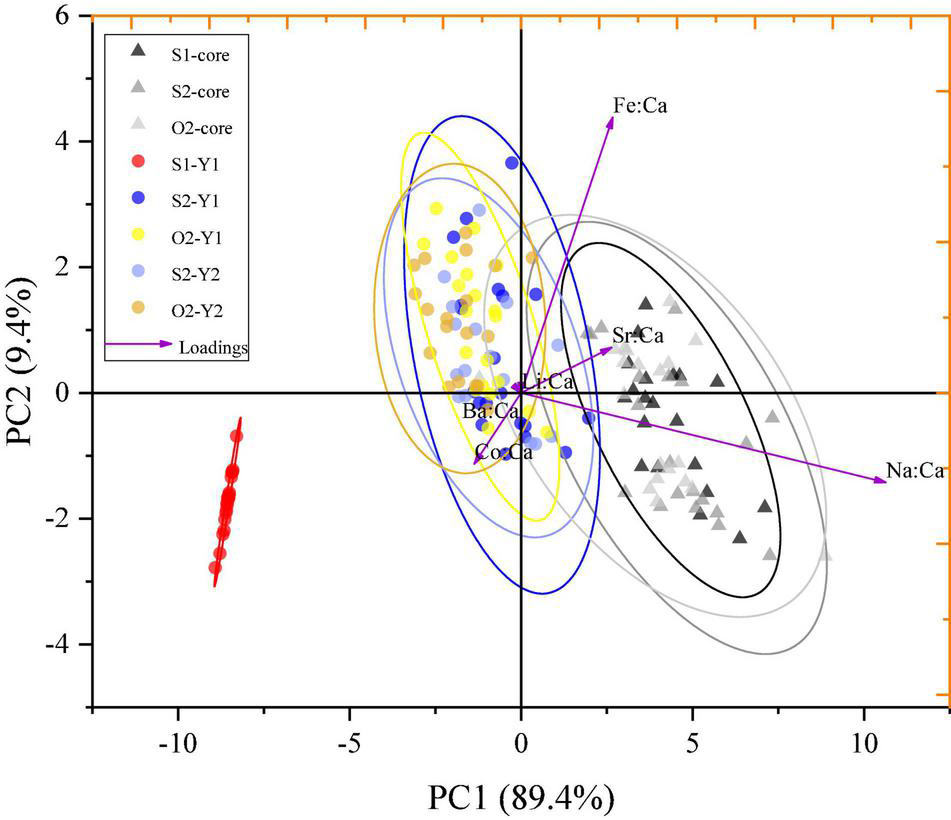

Group Discrimination

Principal component analysis conducted on the element-to-Ca ratios in different otolith zones explained 98.8% of the total variance (PC1:89.4% and PC2: 9.4%) and revealed spatial variations of the ablated zones within the sampling groups (Figure 6). Distinct geochemical signatures were identified for one zone (S1–Y1) and two clusters (cluster 1: S1-core, S2-core, and O2-core zones; cluster 2: S2–Y1, O2–Y1, S2–Y2, and O2–Y2 zones; Figure 6). The S1–Y1 zone was clearly separated from the other zones, whereas cluster 2 showed significant overlapping (Figure 6), suggesting that the S1 group represented a separate population, while the S2 and O2 groups represented the same population. Cluster 1 was isolated from S1–Y1 and cluster 2, suggesting that L. polyactis may have spawning-site fidelity but not natal-site fidelity.

FIGURE 6

PCA for element-to-Ca ratios in ablated zones of otoliths from S1, S2, and O2 L. polyactis groups. Ellipses indicate the mean 95% confidence level contours for each zone; triangles and circles indicate the natal and spawning sites, respectively.

Discussion

Natal- and Spawning-Site Fidelity

The results of this study indicate that the natal sites of the S1, S2, and O2 L. polyactis groups can be discriminated with high accuracy using element-to-Ca ratios (Table 2 and Figure 5), among which Na:Ca, Li:Ca, Ba:Ca, and Sr:Ca ratios are particularly useful natal signatures. The ratios of these four elements to Ca in the core zone were generally higher than those in the Y1 and Y2 zones (P < 0.05). Element Sr is a key element involved in the formation of otoliths (Walther, 2019) and higher Sr:Ca ratios in the core zone have also been observed in Urophycis brasiliensis (Biolé et al., 2019), Anguilla japonica (Tzeng, 1996; Tsukamoto and Arai, 2001), Collichthys lucidus (Liu et al., 2015), and Miichthys miiuy (Xiong et al., 2015). The potential reasons for the higher Sr:Ca ratios in the core zone of L. polyactis otoliths have been summarized by Song et al. (2022): (1) before hatching, L. polyactis feeds on the yolk sac and not on exogenous sources (Zhan et al., 2016); (2) Sr:Ca ratios are mainly influenced by the habitat environment (Elsdon and Gillanders, 2003); (3) during the embryonic stage of fish species, higher concentrations of protein and lower Ca could lead to an increase in the levels of other alkaline earth metals from the Ca group, such as Sr and Ba (Campana, 1999; Murayama et al., 2004). Indeed, Ba:Ca ratios, similar to Sr:Ca ratios, were also higher in the otolith core zone, which is consistent with the observation that high Sr concentrations facilitate Ba uptake into fish otoliths (De Vries et al., 2005). Although the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood, the differences in Ba:Ca ratios are thought to reflect the levels of Ba dissolved in ambient water (Campana, 1999; Ashford et al., 2005). Ba has a nutrient-like vertical distribution with a much higher concentration in deeper waters, and its surface concentration is significantly increased during upwelling (Arkhipkin et al., 2004), as observed along the Lvsi coast on the north and west sides of the submarine canyon off the Yangtze River estuary (Lv et al., 2006; Hu and Wang, 2016), where the individuals of the S1 and S2 groups were sampled. These sampling areas are characterized by large-scale coastal upwelling centered on 31°30′N and 122°40′E, which is influenced significantly by the massive coastal currents (e.g., Yellow Sea and Zhejiang–Fujian coastal currents) and riverine inputs (Changjiang River Diluted Water) (Lv et al., 2006; Hu and Wang, 2016). Therefore, these areas tend to be more Ba-enriched and productive because of supplementation by terrestrial runoff, nutrient-rich bottom waters, and dissolution of Ba in submarine sediments (Hu and Wang, 2016). Among the four elements that were significantly higher in the core zone, Ba and Li concentration mostly reflect the physico-chemical status of the water environment (Sturrock et al., 2012; Grammer et al., 2017). Element Li shows strong positive correlation with the ambient chlorophyll level and could be a potential indicator of marine productivity (Grammer et al., 2017). However, Na should be mentioned as a necessary physiological element required for metabolic reactions and processes associated with growth and reproduction (Loewen et al., 2016). Moreover, Na deposition in otoliths appears to be affected by ontogenetic stages and, to a lesser extent, by stress (Mohan et al., 2014; Grammer et al., 2017).

As elements incorporated into fish otoliths are mainly derived from the environment (Elsdon and Gillanders, 2003), the significant difference in the elemental composition between the core zone and Y1/Y2 zones suggests that the hatching and spawning areas do not completely coincide. The pelagic eggs of L. polyactis are likely to be carried by ocean currents for nearly 2 days. The hatching of fertilized eggs takes ∼ 50 h in seawater (salinity 28) at 18°C (Zhan et al., 2016). Li and Ba concentrations are increased in the nutrient-rich environment, and these important elements contribute to the hatching and forage of L. polyactis, which is reflected by their higher ratios in the core zone compared with the Y1 and Y2 zones.

In addition to the effect of the water environment on the elemental incorporation in otoliths, the contribution of the internal factors was also considered. The otolith core is the area mostly formed during embryogenesis (i.e., the primordium and yolk sac stages; Zhan et al., 2016). Previous studies showed that the 4th increment appears after the first-feeding check with a distance of 20.67 ± 2.28 μm from the central nucleus; it is wide, dark, and well-defined (Li et al., 2013; Zhang T. T. et al., 2019; Song et al., 2022). The 20 μm ablation spots of the core zone were fully within the boundaries of the embryonic stage, indicating that the deposition of elements in the core zone was influenced by endogenous factors. The otolith Sr:Ca ratio, which is widely used to reveal the migration of fish species, in the core zone should reflect maternal rather than environmental effects (Campbell et al., 2002; Shippentower et al., 2011). It can be inferred that the elemental chemistry of the otolith core zone in L. polyactis depends on the internal conditions at the primordium and yolk sac stages and not on the surrounding water. Still, regardless of the factors behind the specificity of the elemental composition in the core zone, the natal-site fidelity of L. polyactis remains uncertain at present.

In contrast, it was difficult to discriminate between the Y1 and Y2 zones representing the spawning site, since the CDA and PCA scatter plots for the S2 and O2 groups notably overlapped (Figure 5 and Figure 6). There were no significant differences in the element-to-Ca ratios between the Y1 and Y2 zones of the S2 and O2 fish sampled in the southern Yellow Sea, indicating that the spawning-site environments for these groups were very similar and suggesting the existence of spawning-site fidelity in L. polyactis. To fully understand the philopatry in L. polyactis populations, natal- and spawning-site fidelities must be considered separately because the latter without the former does not lead to genetic isolation and local adaptation among spawning stocks (Miller et al., 2001). Previous population genetic studies of L. polyactis using diverse types of genetic markers have shown persistently high levels of genetic connectivity and a lack of population structure in L. polyactis (Wang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2020). Fish must first spawn at the previous grounds to avoid intermating and genetic homogenization within populations (Miller et al., 2001). Therefore, at this moment, we suggest that L. polyactis exhibits spawning-site fidelity.

Connectivity Between Overwintering and Spawning Grounds

The PCA scatter plot indicated that the Y1 zone of the S1 group was clearly isolated from the other zones, whereas the Y1 and Y2 zones of the S2 and O2 groups significantly overlapped (Figure 6). These results, together with previous data on the L. polyactis population division (Lin, 1987; Zhang et al., 2014), indicate that the S2 and O2 groups represent the same southern Yellow Sea population, whereas the S1 group represents another population. Some individuals of the southern Yellow Sea and East China Sea populations are mixed in the southern Yellow Sea (Lin et al., 2010; Xu and Chen, 2009), suggesting that the S1 group may be the East China Sea population. The fact that the S2 and O2 groups are the same population indicates that L. polyactis has a stable migratory route in Chinese and South Korean waters. L. polyactis spawns in the coastal region of China but afterward migrates to regions of the Yellow Sea, where it can also be caught by South Korean fishing vessels (Xue, 2005). The discovery of the connectivity between overwintering and spawning groups and the existence of mixed populations in the southern Yellow Sea could contribute to the implementation of fishery management strategies for L. polyactis in China. Although spatial management, including MPAs, has been promoted as a method to conserve biodiversity and manage fishery resource (Agardy, 2017; Li et al., 2020), its design faces many practical issues and requires sound knowledge of ecological processes and population dynamics (Li et al., 2020). Continuing debates on the efficacy of MPAs have determined the need for analytical models that capture the spatial dynamics of marine species, especially in relation to natal- or spawning-site fidelity and larval dispersal (Jones et al., 2009; Krueck et al., 2017). The finding of spawning-site fidelity of L. polyactis has important consequence for the design of MPAs, which should be based on scientific data in order to be effective in the conservation of marine resources, because ultimately, the credibility of agencies that promote and administer MPAs will be evaluated based on the choice of suitable geographical location for protection.

According to previous studies on fish morphology and spawning migration routes, three populations are distinguished: the East China Sea, the southern Yellow Sea, and the Bohai/northern Yellow Sea populations (Lin, 1987; Liu, 1990). With the introduction of various methods of population division analysis, such as evaluation of otolith morphology and microchemistry (Zhang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016), morphometric characteristics (Zhang et al., 2015), and population genomics (Zhang B. D. et al., 2019), an increasing number of cryptic populations have been reported. In addition to an unrecognized L. polyactis cryptic population, its spawning grounds also should also be considered in the design of management strategies. Previous studies have shown that spawning grounds have expanded from nearshore to offshore waters (Ding et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2008; Song et al., 2022). Despite new data on cryptic populations, biological characteristics, and the range of spawning grounds, spatial management measures, especially MPAs, have not been improved since the implementation of the national aquatic germplasm resources reserve of L. polyactis in the Lvsi fishing grounds in December 2009 (Ministry of Agriculture [MOA], 2021), and the monitoring and enforcement of protected areas have been unsatisfactory (Cao et al., 2017). The unprecedented changes in the biological characteristics and population structure of L. polyactis call for new management approaches to counteract anthropogenic impacts (Li et al., 2020). Moreover, regarding stocks that occur within the exclusive economic zones of two or more states, Article 63 of the Law of the Sea Convention requires relevant countries to collaborate and ensure the rational utilization of stocks, because for shared species, protective measures implemented only by one country may have a weak effect unless they are also observed by the others. Cooperation between China and South Korea along the same migratory route of L. polyactis is crucial for protecting this overexploited and highly targeted species.

In conclusion, in this study we analysed the natal- and spawning-site fidelity and connectivity among three groups of L. polyactis sampled in different locations based on the elemental signatures of otolith zones. The results indicate that (1) L. polyactis has spawning-site but not natal-site fidelity and that (2) the three groups represent two L. polyactis populations, namely, the southern Yellow Sea population (S2 and O2) and the East China Sea population (S1), indicating a stable migratory route of L. polyactis between Chinese and South Korean waters. The identification of L. polyactis natal- and spawning-site fidelity is critical for marine spatial planning and management of this highly targeted fish species through cooperation between China and South Korea. With the development of advanced analytical instruments for fine scale elemental analysis, in future study, we intend to investigate the oxygen and carbon stable isotopic ratios (δ18O and δ13C) of otoliths from the core to the edge for comparison with the locations of annual rings, reaching a robust and reliable conclusion on natal-site fidelity. Of course, multidisciplinary techniques are often required in population studies; owing to complexity of the stock, the results from different methods should therefore be integrated to reach a consensus. In future study on population division, we will use various methods, including otolith shape, body morphology, and genetics to reach a robust conclusion.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by institutional animal care and use Committee of Shanghai Ocean University.

Author contributions

DS, ZK, and YX conceived and designed the experiments. DS performed the experiments, wrote the manuscript, analyzed the data, and applied the statistical analyses with the help of YX. All authors provided editorial advice and agreed this version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 3180 2297).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all scientific staff and crew for their assistance with sample collection and experimental implementation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Agardy T. (2017). Justified ambivalence about MPA effectiveness.ICES J. Mar. Sci.751183–1185. 10.1093/icesjms/fsx083

2

Alo D. Lacy S. N. Castillo A. Samaniego H. A. Marquet P. H. (2020). The macroecology of fish migration.Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr.3099–116. 10.1111/geb.13199

3

Amano Y. Kuwahara M. Takahashi T. Shirai K. Yamane K. Kawakami T. et al (2018). Low-fidelity homing behaviour of Biwa salmon Oncorhynchus sp. landlocked in Lake Biwa as inferred from otolith elemental and Sr isotopic compositions.Fish. Sci.84799–813. 10.1007/s12562-018-1220-7

4

Arkhipkin A. I Campana S. E. FitzGerald J. Thorrold S. R. (2004). Spatial and temporal variation in elemental signatures of statoliths from the Patagonian longfin squid (Loligo gahi).Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.61212–1224. 10.1139/F04-075

5

Ashford J. R. Jones C. M. Hofmann E. Everson I. Moreno C. Duhamel G. et al (2005). Can otolith elemental signatures record the capture site of Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides), a fully marine fish in the Southern Ocean?Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.622832–2840. 10.1139/f05-191

6

Baik C. Cho K. D. Lee C. Choi K. H. (2004). Oceanographic conditions of fishing ground of Yellow Croaker (Pseudosciaena polyactis) in Korean Waters.J. Kor. Fish. Soc.37232–248.

7

Bardbury I. R. Campana S. E. Bentzen P. (2008). Otolith elemental composition and adult tagging reveal spawning site fidelity and estuarine dependency in rainbow smelt.Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.368255–268. 10.3354/meps07583

8

Barnes T. C. Gillanders B. M. (2013). Combined effects of extrinsic and intrinsic factors on otolith chemistry: implications for environmental reconstructions.Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.701159–1166. 10.1139/cjfas-2012-0442

9

Biolé F. G. Thompson G. A. Vargas C. V. Leisen M. Barra F. Volpedo A. V. et al (2019). Fish stocks of Urophycis brasiliensis revealed by otolith fingerprint and shape in the Southwestern Atlantic Ocean.Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci.229:106406. 10.1016/j.ecss.2019.106406

10

Bishop M. A. Reynolds B. F. Powers S. P. (2010). An in situ, individual-based approach to quantify connectivity of marine fish: ontogenetic movements and residency of lingcod.PLoS One5:e14267. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014267

11

Campana S. E. (1999). Chemistry and composition of fish otoliths: pathways, mechanisms, and applications.Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.188263–297. 10.3354/meps188263

12

Campbell J. L. Babaluk J. A. Cooper M. Grime G. W. Halden N. M. Nejedly Z. et al (2002). Strontium distribution in young-of-the-year Dolly Varden otoliths: potential for stock discrimination.Nucl. Inst. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms.189185–189. 10.1016/S0168-583X(01)01039-4

13

Cao L. Chen Y. Dong S. Hanson A. Huang B. Leadbitter D. et al (2017). Opportunity for marine fisheries reform in China.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.114435–442. 10.1073/pnas.1616583114

14

Chen K.-Y. Ludsin S. A. Marcek B. J. Olesik J. W. Marschall E. A. (2020). Otolith microchemistry shows natal philopatry of walleye in western Lake Erie.J. Great Lakes Res.461349–1357. 10.1016/j.jglr.2020.06.006

15

Choi M. J. Kim D. H. (2020). Assessment and Management of Small Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) Stocks in South Korea.Sustainability12:8257. 10.3390/su12198257

16

Cote J. Clobert J. Brodin T. Fogarty S. Sih A. (2010). Personality-dependent dispersal: characterization, ontogeny, and consequences for spatially structured populations.Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B.3654065–4076. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0176

17

De Vries M. C. Gillanders B. M. Elsdon T. S. (2005). Facilitation of barium uptake into fish otoliths: influence of strontium concentration and salinity.Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta694061–4072. 10.1016/j.gca.2005.03.052

18

Di Franco A. Gillanders B. M. De Benedetto G. Pennetta A. De Leo G. A. Guidetti P. (2012). Dispersal patterns of coastal fish: implications for designing networks of marine protected areas.PLoS One7:e31681. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031681

19

Ding F. Y. Lin L. S. Li J. S. Cheng J. H. (2007). Relationship between Redlip Croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) Spawning Stock Distribution and Water Masses Dynamics in Northern East China Sea Region.J. Nat. Resour.221013–1019.

20

Dingle H. Drake V. A. (2007). What is migration?BioScience57113–121. 10.1641/b570206

21

Elsdon T. S. Gillanders B. M. (2003). Reconstructing migratory patterns of fish based on environmental influences on otolith chemistry.Rev. Fish Biol. Fish.13217–235. 10.1023/B:RFBF.0000033071.73952.40

22

Engstedt O. Engkvist R. Larsson P. (2013). Elemental fingerprinting in otoliths reveals natal homing of anadromous Baltic Sea pike (Esox Lucius L.).Ecol. Freshw. Fish.23313–321. 10.1111/eff.12082

23

Fishbase (2019). Fishbase.Available Online at: https://fishbase.in/summary/Larimichthys-polyactis.html[accessed Dec 10, 2020].

24

Florin A.-B. Franzén F. (2010). Spawning site fidelity in Baltic Sea turbot (Psetta maxima).Fish. Res.102207–213. 10.1016/j.fishres.2009.12.002

25

Gillanders B. M. (2002). Temporal and spatial variability in elemental composition of otoliths: implications for determining stock identity and connectivity of populations.Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.59669–679. 10.1139/f02-040

26

Grammer G. L. Morrongiello J. R. Izzo C. Hawthorne P. J. Middleton J. F. Gillanders B. M. (2017). Coupling biogeochemical tracers with fish growth reveals physiological and environmental controls on otolith chemistry.Ecol. Monogr.87487–507. 10.1002/ecm.1264

27

Han Q. Grüss A. Shan X. Jin X. Thorson J. T. (2020). Understanding patterns of distribution shifts and range expansion/contraction for small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) in the Yellow Sea.Fish. Oceanogr.3069–84. 10.1111/fog.12503

28

Hastings A. Botsford L. W. (2006). Persistence of spatial populations depends on returning home.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.1036067–6072. 10.1073/pnas.0506651103

29

Hilborn R. Quinn T. P. Schindler D. E. Rogers D. E. (2003). Biocomplexity and fisheries sustainability.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.1006564–6568. 10.1073/pnas.1037274100

30

Honig A. Etter R. Pepperman K. Morello S. Hannigan R. (2020). Site and age discrimination using trace element fingerprints in the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis.J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.522:151249. 10.1016/j.jembe.2019.151249

31

Hu J. Wang X. H. (2016). Progress on upwelling studies in the China seas.Rev. Geophys.54653–673. 10.1002/2015rg000505

32

Humston R. Priest B. M. Hamilton W. C. Bugas P. E. (2010). Dispersal between tributary and main-stem rivers by juvenile smallmouth bass evaluated using otolith microchemistry.Trans. Am. Fish. Soc.139171–184. 10.1577/t08-192.1

33

Jiang T. Liu H. B. Lu M. J. Chen T. T. Yang J. (2016). A possible connectivity among estuarine tapertail anchovy (Coilia nasus) populations in Yangtze River, Yellow Sea, and Poyang Lake.Estuar. Coasts391762–1768. 10.1007/s12237-016-0107-z

34

Jones G. P. Almany G. R. Russ G. R. Sale P. F. Steneck R. S. Oppen M. J. H. et al (2009). Larval retention and connectivity among populations of corals and reef fishes: history, advances, and challenges.Coral Reefs28307–325. 10.1007/s00338-009-0469-9

35

Kraus R. T. Secor D. H. (2004). Incorporation of strontium into otoliths of an estuarine fish.J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.30285–106. 10.1016/j.jembe.2003.10.004

36

Krueck N. C. Ahmadia G. N. Green A. Jones G. P. Possingham H. P. Riginos C. et al (2017). Incorporating larval dispersal into MPA design for both conservation and fisheries.Ecol. Appl.27925–941. 10.1002/eap.1495

37

Lee Q. Lee A. Liu Z. Szuwalski C. S. (2019). Life history changes and fisheries assessment performance: a case study for small yellow croaker.ICES J. Mar. Sci.77645–654. 10.1093/icesjms/fsz232

38

Li J. Q. Ye C. C. Wang W. B. Yin Z. Q. Chen S. J. (2011). A stock assessment of small yellow croaker by Bayes-based Pella-Tomlinson model in the East China Sea.J. Shanghai Ocean Univ.20873–882.

39

Li Y. X. Tang J. H. Xu X. M. Xu J. Liu Z. Y. Xu H. et al (2013). Comparison of otolith microstructures in small yellow croaker larvae and juveniles from Sanmen Bay and Lvsi.Mar. Fish35423–431. 10.13233/j.cnki.mar.fish.2013.04.008

40

Li Y. Z. Sun M. Zhang C. L. Zhang Y. L. Xu B. D. Ren Y. P. et al (2020). Evaluating fisheries conservation strategies in the socio-ecological system: a grid-based dynamic model to link spatial conservation prioritization tools with tactical fisheries management.PLoS One15:e0230946. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230946

41

Lim H. K. Le M. H. An C. M. Kim S. Y. Park M. S. Chang Y. J. (2010). Reproductive cycle of yellow croaker Larimichthys polyactis in southern waters off Korea.Fish. Sci.76971–980. 10.1007/s12562-010-0288-5

42

Lin L. S. Cheng J. H. Jiang Y. Z. Yuan X. W. Li J. S. Gao T. X. (2008). Spatial distribution and environmental characteristics of the spawning grounds of small yellow croaker in the southern Yellow Sea and the East China Sea.Acta Ecol. Sin.283485–3492.

43

Lin L. S. Jiang Y. Z. Liu Z. L. Dou S. Z. Gao T. X. (2010). Analysis of the distribution difference of Small Yellow Croaker between the southern Yellow Sea and the East China Sea.Periodical Ocean Univ. China401–6. 10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.2010.03.001

44

Lin N. Chen Y. G. Jin Y. Yuan X. W. Ling J. Z. Jiang Y. Z. (2018). Distribution of the early life stages of small yellow croaker in the Yangtze River estuary and adjacent waters.Fish. Sci.84357–363. 10.1007/s12562-018-1177-6

45

Lin X. Z. (1987). Biological characteristics and resources status of three main commercial fishes in offshore waters of China.J. Fish. China11187–194.

46

Liu H. B. Jiang T. Huang H. H. Shen X. Q. Zhu J. B. Yang J. (2015). Estuarine dependency in Collichthys lucidus of the Yangtze River Estuary as revealed by the environmental signature of otolith strontium and calcium.Environ. Biol. Fish.98165–172. 10.1007/s10641-014-0246-7

47

Liu X. S. (1990). Fisheries Resources Survey and Zoning in the Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea Area.Beijing: Ocean Press, 191–200.

48

Loewen T. N. Carriere B. Reist J. D. Halden N. M. Anderson W. G. (2016). Linking physiology and biomineralization processes to ecological inferences on the life history of fishes.Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A202123–140. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.06.017

49

Lowerre-Barbieri S. Walters S. Bickford J. Cooper W. Muller R. (2013). Site fidelity and reproductive timing at a spotted seatrout spawning aggregation site: individual versus population scale behavior.Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.481181–197. 10.3354/meps10224

50

Lv X. Qiao F. Xia C. Zhu J. Yuan Y. (2006). Upwelling off Yangtze River estuary in summer.J. Geophys. Res.111:C11S08. 10.1029/2005JC003250

51

Ma Q. Y. Jiao Y. Ren Y. P. Xue Y. (2020). Population dynamics modelling with spatial heterogeneity for yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) along the coast of China.Acta Oceanol. Sin.39107–119. 10.1007/s13131-020-1602-4

52

Martinho F. Pina B. Nunes M. Vasconcelos R. P. Fonseca V. F. Crespo D. et al (2020). Water and otolith chemistry: implications for discerning estuarine nursery habitat use of a juvenile flatfish.Front. Mar. Sci.7:347. 10.3389/fmars.2020.00347

53

Mellish J.-A. Thomton J. Horning M. (2007). Physiological and behavioral response to intra-abdominal transmitter implantation in Steller sea lions.J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.351283–293. 10.1016/j.jembe.2007.07.015

54

Miller L. M. Kallemeyn L. Senanan W. (2001). Spawning-site and natal-site fidelity by northern pike in a large lake: mark-recapture and genetic evidence.Trans. Am. Fish. Soc.130307–316. 10.1577/1548-86592001130<0307:ssansf<2.0.co;2

55

Ministry of Agriculture [MOA] (2021). List of National Aquatic germplasm Resources Reserves.Available Online at: www.moa.gov.cn/nybgb/2010/dyq/201805/t20180529_6145100.htm[accessed Oct 15, 2021].

56

Mohan J. Rahman M. Thomas P. Walther B. (2014). Influence of constant and periodic experimental hypoxic stress on Atlantic croaker otolith chemistry.Aquat. Biol.201–11. 10.3354/ab00542

57

Mora C. Sale P. F. (2002). Are populations of coral reef fish open or closed?Trends Ecol. Evol.17422–428. 10.1016/s0169-5347(02)02584-3

58

Munch S. B. Clarke L. M. (2008). A Bayesian approach to identifying mixtures from otolith chemistry data.Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.652742–2751. 10.1139/f08-169

59

Murayama E. Takagi Y. Nagasawa H. (2004). Immunohistochemical localization of two otolith matrix proteins in the otolith and inner ear of the rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss: comparative aspects between the adult inner ear and embryonic otocysts.Histochem. Cell Biol.121155–166. 10.1007/s00418-003-0605-5

60

Ovenden J. R. (2013). Crinkles in connectivity: combining genetics and other types of biological data to estimate movement and interbreeding between populations.Mar. Freshw. Res.64201–207. 10.1071/mf12314

61

Reis-Santos P. Tanner S. Vasconcelos R. Elsdon T. Cabral H. Gillanders B. (2013). Connectivity between estuarine and coastal fish populations: contributions of estuaries are not consistent over time.Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.491177–186. 10.3354/meps10458

62

Sadovy Y. Domeier D. (2005). Are aggregation-fisheries sustainable? Reef fish fisheries as a case study.Coral. Reefs24254–262. 10.1007/s00338-005-0474-6

63

Sandercock F. K. (1991). “Life history of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch),” in Pacific Salmon Life Histories, edsGrootC.MargolisL. (Vancouver: UBC Press), 397–445.

64

Schulz-Mirbach T. Ladich F. Plath M. Heß M. (2019). Enigmatic ear stones: what we know about the functional role and evolution of fish otoliths.Biol. Rev.94457–482. 10.1111/brv.12463

65

Shan X. Li X. Yang T. Sharifuzzaman S. M. Zhang G. Jin X. et al (2017). Biological responses of small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) to multiple stressors: a case study in the Yellow Sea, China.Acta Oceanol. Sin.3639–47. 10.1007/s13131-017-1091-2

66

Shippentower G. E. Schreck C. B. Heppell S. A. (2011). Who’s your momma? Recognizing maternal origin of juvenile steelhead using injections of strontium chloride to create transgenerational marks.Trans. Am. Fish. Soc.1401330–1339. 10.1080/00028487.2011.620488

67

Song D. Xiong Y. Jiang T. Yang J. Zhong X. Tang J. (2022). Early life migration and population discrimination of the small yellow croaker Larimichthys polyactis from the Yellow Sea: inferences from otolith Sr/Ca ratios.J. Oceanol. Limnol.10.1007/s00343-021-1041-x

68

Stone K. R. Kastelle C. R. Benson I. M. Helser T. E. Short J. A. Kang S. (2020). Stock structure of Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus) around the Korean Peninsula: an otolith microchemical perspective.Mar. Freshw. Res.72774–786. 10.1071/MF20223

69

Sturrock A. M. Trueman C. N. Darnaude A. M. Hunter E. (2012). Can otolith elemental chemistry retrospectively track migrations in fully marine fishes?J. Fish Biol.81766–795. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03372.x

70

Svedäng H. Righton D. Jonsson P. (2007). Migratory behaviour of Atlantic cod Gadus morhua: natal homing is the prime stock-separating mechanism.Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.3451–12. 10.3354/meps07140

71

Szuwalski C. Jin X. Shan X. Clavelle T. (2020). Marine seafood production via intense exploitation and cultivation in China: costs, benefits, and risks.PLoS One15:e0227106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227106

72

Taddese F. Reid M. R. Closs G. P. (2019). Direct relationship between water and otolith chemistry in juvenile estuarine triplefin Forsterygion nigripenne.Fish. Res.21132–39. 10.1016/j.fishres.2018.11.002

73

Tanner S. E. Reis-Santos P. Cabral H. N. (2016). Otolith chemistry in stock delineation: a brief overview, current challenges, and future prospects.Fish. Res.173206–213. 10.1016/j.fishres.2015.07.019

74

Thorisson K. Jonsdottir I. G. Marteinsdottir G. Campana S. E. (2010). The use of otolith chemistry to determine the juvenile source of spawning cod in Icelandic waters.ICES J. Mar. Sci.6898–106. 10.1093/icesjms/fsq133

75

Tripp A. Murphy H. M. Davoren G. K. (2020). Otolith Chemistry Reveals Natal Region of Larval Capelin in Coastal Newfoundland, Canada.Front. Mar. Sci.7:258. 10.3389/fmars.2020.00258

76

Tsukamoto K. Arai T. (2001). Facultative catadromy of the eel Anguilla japonica between freshwater and seawater habitats.Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.220265–276. 10.3354/meps220265

77

Tzeng W. N. (1996). Effects of salinity and ontogenetic movements on strontium: calcium ratios in the otoliths of the Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica Temminck and Schlegel.J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.199111–122. 10.1016/0022-0981(95)00185-9

78

Walther B. D. (2019). The art of otolith chemistry: interpreting patterns by in integrating perspectives.Mar. Freshw. Res.701643–1658. 10.1071/mf18270

79

Wang L. Liu S. F. Zhuang Z. M. Guo L. Meng Z. N. Lin H. R. (2013). Population genetic studies revealed local adaptation in a high gene-flow marine fish, the small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis).PLoS One8:e83493. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083493

80

Wang Y. K. Huang J. S. Tang X. X. Jin X. S. Sun Y. (2016). Stable isotopic composition of otoliths in identification of stock structure of small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) in China.Acta Oceanol. Sin.3529–33. 10.1007/s13131-016-0868-z

81

Xie Q. P. Li B. B. Zhan W. Liu F. Tan P. Wang X. et al (2021). A Transient Hermaphroditic Stage in Early Male Gonadal Development in Little Yellow Croaker, Larimichthys polyactis.Front. Endocrinol.11:542942. 10.3389/fendo.2020.542942

82

Xiong Y. Liu H. B. Jiang T. Liu P. T. Tang J. H. Zhong X. M. et al (2015). Investigation on otolith microchemistry of wild Pampus argenteus and Miichthys miiuy in the Southern Yellow Sea, China.Haiyang Xuebao3736–43. 10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2015.02.004

83

Xiong Y. Yang J. Jiang T. Liu H. B. Zhong X. M. Tang J. H. (2017). Early life history of the small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) in sandy ridges of the South Yellow Sea.Mar. Biol. Res.13993–1002. 10.1080/17451000.2017.1319067

84

Xu Z. L. Chen J. J. (2009). Analysis on migratory routine of Larimichthys polyactis.J. Fish. Sci. China16931–940.

85

Xue G. F. (2005). Bilateral fisheries agreements for the cooperative management of the shared resources of the China seas: a note.Ocean Dev. Int. Law36363–374. 10.1080/00908320500308767

86

Zhan W. Lou B. Chen R. Y. Mao G. M. Liu F. Xu D. D. et al (2016). Observation of embryonic, larva and juvenile development of small yellow croaker, Larimichthys polyactis.Oceanol. Limnol. Sin.471033–1039. 10.11693/hyhz20160500114

87

Zhang B. D. Li Y. L. Xue D. X. Liu J. X. (2020). Population genomic evidence for high genetic connectivity among populations of small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) in inshore waters of China.Fish. Res.225:105505. 10.1016/j.fishres.2020.105505

88

Zhang B. D. Xue D. X. Li Y. L. Liu J. X. (2019). RAD genotyping reveals fine-scale population structure and provides evidence for adaptive divergence in a commercially important fish from the northwestern Pacific Ocean.PeerJ.7:e7242. 10.7717/peerj.7242

89

Zhang C. Jiang Y. Q. Ye Z. J. Li Z. G. Dou S. Z. (2015). A morphometric investigation of the small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis Bleeker, 1877): evidence for subpopulations on the Chinese coast.J. Appl. Ichthyol.3267–74. 10.1111/jai.12923

90

Zhang C. Ye Z. J. Wan R. Ma Q. Y. Li Z. G. (2014). Investigating the population structure of small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) using internal and external features of otoliths.Fish. Res.15341–47. 10.1016/j.fishres.2013.12.012

91

Zhang T. T. Wang Y. K. Yuan W. Jin X. S. Chen C. Sun Y. (2019). Research on sagitta microstructure characteristics of Young of the Year (YOY) Larimichthys polyactis in the Bohai Sea.Prog. Fish. Sci.4135–40. 10.19663/j.issn2095-9869.20190221001

Summary

Keywords

otolith microchemistry, Larimichthys polyactis , laser ablation inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry, spawning-site fidelity, connectivity

Citation

Song D, Xiong Y, Jiang T, Yang J, Zhong X, Tang J and Kang Z (2022) Evaluation of Spawning- and Natal-Site Fidelity of Larimichthys polyactis in the Southern Yellow Sea Using Otolith Microchemistry. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:820492. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.820492

Received

23 November 2021

Accepted

30 December 2021

Published

02 February 2022

Volume

8 - 2021

Edited by

Kit Yue Kwan, Beibu Gulf University, China

Reviewed by

Ying Xue, Ocean University of China, China; Bilin Liu, Shanghai Ocean University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Song, Xiong, Jiang, Yang, Zhong, Tang and Kang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Xiong, yxiongshfu@126.comXiaming Zhong, oceanxmzh@163.com

This article was submitted to Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Living Resources, a section of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.