Abstract

Sea surface temperature (SST) has increased worldwide since the beginning of the 20th century, a trend which is expected to continue. Changes in SST can have significant impacts on marine biota, including population-level shifts and alterations in community structure and diversity, and changes in the timing of ecosystem events. Seagrasses are a group of foundation species that grow in shallow coastal and estuarine systems, where they provide many ecosystem services. Eelgrass, Zostera marina L., is the dominant seagrass species in the Northeast United States of America (USA). Multiple factors have been cited for losses in this region, including light reduction, eutrophication, and physical disturbance. Warming has the potential to exacerbate seagrass loss. Here, we investigate regional changes in eelgrass presence and abundance in relation to local water temperature using monitoring data from eight sites in the Northeastern USA (New Hampshire to Maryland) where a consistent monitoring protocol, SeagrassNet, has been applied. We use a hurdle model consisting of a generalized additive mixed model (GAMM) with binomial and beta response distributions for modeling eelgrass presence and abundance, respectively, in relation to the local summer average water temperature. We show that summer water temperature one year prior to monitoring is a significant predictor of eelgrass presence, but not abundance, on a regional scale. Above average summer temperatures correspond to a decrease in probability of eelgrass presence (and increased probability of eelgrass absence) the following year. Cooler than average temperatures in the preceding year, down to approximately 0.5°C below the site average, are associated with the highest predicted probability of eelgrass presence. Our findings suggest vulnerability in eelgrass meadows of the Northeast USA and emphasize the value of unified approaches to seagrass monitoring, conservation and management at the seascape scale.

Introduction

Sea surface temperature (SST) has increased worldwide since the beginning of the 20th century (Hartmann et al., 2013; NOAA, 2016a; NOAA, 2016b). In the Northern Hemisphere, SST is projected to rise by approximately 0.05 to 0.5°C per decade to the end of the 21st century (Alexander et al., 2018), with warming expected to be amplified in shallow coastal waters (Oczkowski et al., 2015). The primary cause of increasing SST is climate warming due to increasing amounts of greenhouse gases being released into the atmosphere by anthropogenic activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels (IPCC, 2018). These gases reduce the amount of heat that is radiated from the Earth’s surface back into space and the upper ocean is absorbing over ninety percent of the excess heat retained by the Earth (Bindoff et al., 2007). Changes in SST have been shown to vary with season, year, and region (Hartmann et al., 2013) and can have significant impacts on marine biota, including population shifts, alterations in community structure and diversity, and changes in plant phenology and the timing of other ecosystem-level events and processes (Parmesan and Yohe, 2003; Doney et al., 2012).

Seagrasses are a group of foundation species that grow in shallow coastal and estuarine waters. They form extensive meadows ranging from a few square meters to hundreds of square kilometers and can be found along every continent except Antarctica (Green and Short, 2003). Seagrass meadows provide many ecosystem services such as improved water quality and clarity, increased biodiversity and habitat, sediment stabilization, and nutrient accumulation (Orth et al., 2006). Seagrass meadows also store significant quantities of carbon in biomass and sediments (Fourqurean et al., 2012), minimize exposure of bacterial pathogens to humans, fish, and invertebrates (Lamb et al., 2017; Reusch et al., 2021) and support global fisheries (Unsworth et al., 2018). Despite their importance, seagrasses are among the most threatened ecosystems on earth, with global trends of loss occurring since 1880 (Waycott et al., 2009; UNEP, 2020; Dunic et al., 2021). The primary causes of loss are sustained pressure from coastal development, declines in water quality, and climate change, including thermal stress due to rising SST (Short and Wyllie-Echeverria, 1996; Waycott et al., 2009; Wilson and Lotze, 2019).

The response of seagrass species to increased water temperature depends on their relative thermal tolerances and their optimum temperatures for photosynthesis, respiration, and growth (Short and Neckles, 1999; Björk et al., 2008). Temperature stress on seagrasses can result in altered growth rates, distribution shifts, changes in patterns of sexual reproduction, and mortality. Temperature stress has been linked to seagrass mortality in the Mediterranean Sea (Díaz-Almela et al., 2009; Jordà et al., 2012), Australia (Seddon et al., 2000; Nowicki et al., 2017; Strydom et al., 2020), southeast Asia, and the Caribbean (Hall et al., 2016; Zieman et al., 1999), and shifts in the species composition of communities dominated by Zostera marina L. (eelgrass; Shields et al., 2019). Likewise, increased SST has been linked to the northward expansion of Halophila decipiens into the Mediterranean Sea (Gerakaris et al., 2020) and an increase in flowering intensity and frequency in Posidonia oceanica and Zostera japonica (Ruiz et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2019). Environmental factors, such as hypersalinity (Durako and Howarth, 2017; Wilson and Dunton, 2018), shallow water depths (Collier and Waycott, 2014), limited circulation (Koch and Erskine, 2001; Binzer et al., 2005), and reduced oxygen and light (Moore and Jarvis, 2008) can amplify the impacts of temperature stress on seagrass meadows (Lefcheck et al., 2017).

The ability of seagrasses to resist the effects of stressors and recover from disturbance depends on multiple biotic and abiotic factors (O’Brien et al., 2018). Recovery of seagrass meadows following heat-induced disturbance and mortality has been attributed to increased genetic diversity (Reusch et al., 2005) and the presence of viable seed banks (Moore and Jarvis, 2008; Strydom et al., 2020). The self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms present in continuous seagrass meadows create conditions that promote further seagrass growth and may buffer against disturbance (Maxwell et al., 2017). Fragmented and sparse meadows of slow-growth species may have reduced capacity to buffer stresses due to minimal ability to modify their habitat, therefore, prospects for recovery will rely on long-distance dispersal of seeds and vegetative expansion (Nowicki et al., 2017). Prolonged periods without recovery can lead to regime shifts in which conditions are no longer habitable for seagrass. For example, Moksnes et al. (2018) document a local regime shift following the loss of eelgrass along the Swedish West Coast.

Eelgrass is the most widely distributed seagrass species in temperate marine environments of the Northern Hemisphere. The species has a wide temperature tolerance with an optimal range between 10 and 25°C (Moore et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007). Exposure to temperatures above 25°C have been shown to cause plant mortality (Greve et al., 2003; Reusch et al., 2005; Moore and Jarvis, 2008; Moore et al., 2014). For example, in Northern Europe the performance and survival of eelgrass was severely impacted when plants were exposed to water temperatures ≥25°C during a series of heat waves (Reusch et al., 2005; Nejrup and Pedersen, 2008; Ehlers et al., 2008). Likewise, complete vegetative dieback was observed in Chesapeake Bay, VA following a heat wave where waters exceeded 30°C (Moore and Jarvis, 2008). Moore et al. (2014) also suggested that short-term exposure to rapidly increasing temperature by 4-5°C above the average of normal summer months can result in widespread diebacks.

Here, we use data from eight SeagrassNet monitoring sites located along the northeastern coast of the United States of America (USA) (New Hampshire to Maryland) to investigate changes in eelgrass presence and abundance in relation to summer water temperature. SeagrassNet is a global seagrass monitoring network that uses a standardized monitoring protocol to detect and document seagrass habitat changes and relate them to environmental trends. The SeagrassNet program began in 2001 in the Western Pacific and now includes 126 sites in 33 countries (Short et al., 2006; Short et al., 2014). Along the east coast of the USA, it is estimated that up to 50% of all eelgrass habitat has been lost in the past century, and the prospects for recovery in most of this area are low (Green and Short, 2003). More recently, a global assessment of seagrass trajectories found eelgrass extent to be in rapid decline in the region (Turschwell et al., 2021) where mean SST is warming at a rate of 0.4°C per decade (Alexander et al., 2018), and summer SST has increased more than 2°C since 1902 (Karmalkar and Horton, 2021). The large geographic coverage of our dataset and time-period in which it spans provide an opportunity to investigate the influence of changing temperature regimes on eelgrass in the Northeast USA.

Methods

Eelgrass Monitoring

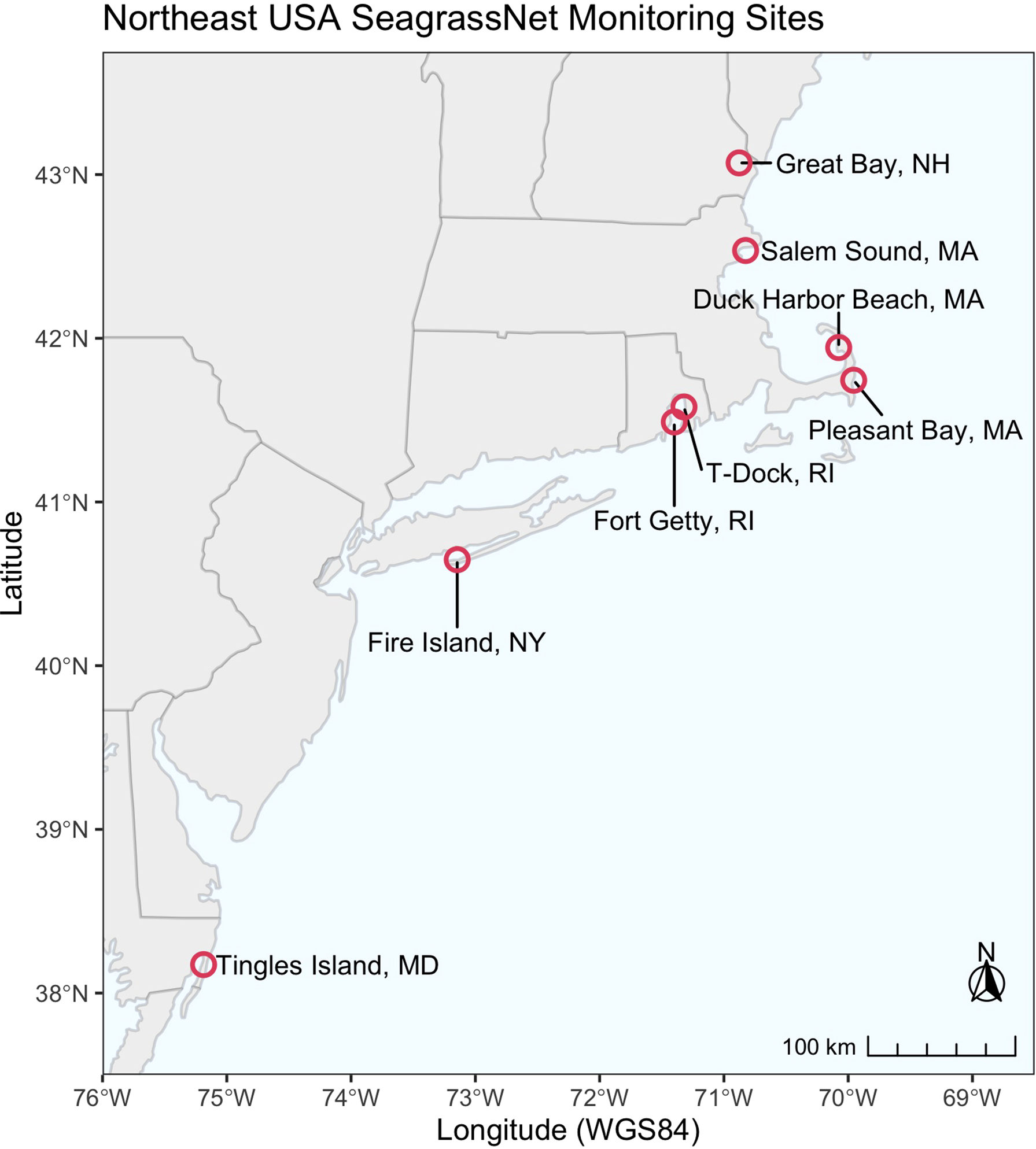

Eelgrass was monitored annually at eight SeagrassNet monitoring sites located along a latitudinal gradient on the northeastern Atlantic coastline of the USA (Figure 1). The sites vary in their geomorphic setting, surrounding land use, tide range, bed size, and sources of disturbance (Supplemental Material). Summer (June-August) temperatures at each site reflect primarily site latitude (Table 1), geomorphic setting, residence time, and proximity to oceanic flushing. A SeagrassNet site includes three 50-m transects that parallel the shoreline along an increasing depth gradient. SeagrassNet monitoring sites are chosen to be representative of seagrass in the area of interest (Short et al., 2005). Seagrass abundance is measured within twelve permanent 0.25 m2 quadrats positioned at random locations along the transects.

Figure 1

SeagrassNet sites located in Northeast USA.

Table 1

| SeagrassNet Site | Coordinates | Average Daily Mean Temperature (June-Aug.) | Temperature Record Time Periods | n Years | Water temperature data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Bay, New Hampshire | N 43° 2.5632’ W 70° 31.8294’ | 20.9°C | 2006-2012, 2014-2020 | 14 | Great Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (NOAA National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS), 2021); distance from monitoring transect 2.5 km |

| Salem Sound, Massachusetts | N 42° 19.9080’ W 70° 29.4000’ | 15.7°C | 2011, 2013-2019 | 8 | Within monitoring transect |

| Duck Harbor Beach, Massachusetts | N 41° 34.0560’ W 69° 34.3980’ | 20.7°C | 2003-2018, 2020 | 17 | Within monitoring transect |

| Pleasant Bay, Massachusetts | N 41° 27.0600’ W 69° 34.3980’ | 22.3°C | 2004-2018, 2020 | 16 | Within monitoring transect |

| T-Dock, Rhode Island | N 41° 34.8402’ W 71° 19.2798’ | 20.8°C | 2005-2012, 2016 | 9 | Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (NOAA National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS), 2021); T-Wharf Surface, distance from monitoring transect 0.25 km |

| Fort Getty, Rhode Island | N 41° 29.6400’ W 71° 23.8602’ | 21.2°C | 2005-2007, 2010-2011 | 5 | University of Rhode Island URI 169 Quonset Point, Surface Sonde (NERACOOS, 2021); distance from monitoring transect 10 km |

| Fire Island, New York | N 41° 6.0000’ W 70° 31.8240’ | 24.3°C | 2006, 2008, 2010-2016, 2019-2020 | 11 | Long Island Shore, Smith Point Bridge (LIShore, 2021); distance from monitoring transect 6 km; and within monitoring transect (2019-2020) |

| Tingles Island, Maryland | N 38° 6.7440’ W 75° 6.5640’ | 27.0°C | 2009-2018, 2020 | 11 | Within monitoring transect |

SeagrassNet site locations and time period average of the daily average summertime water temperatures (used for centering) within each site.

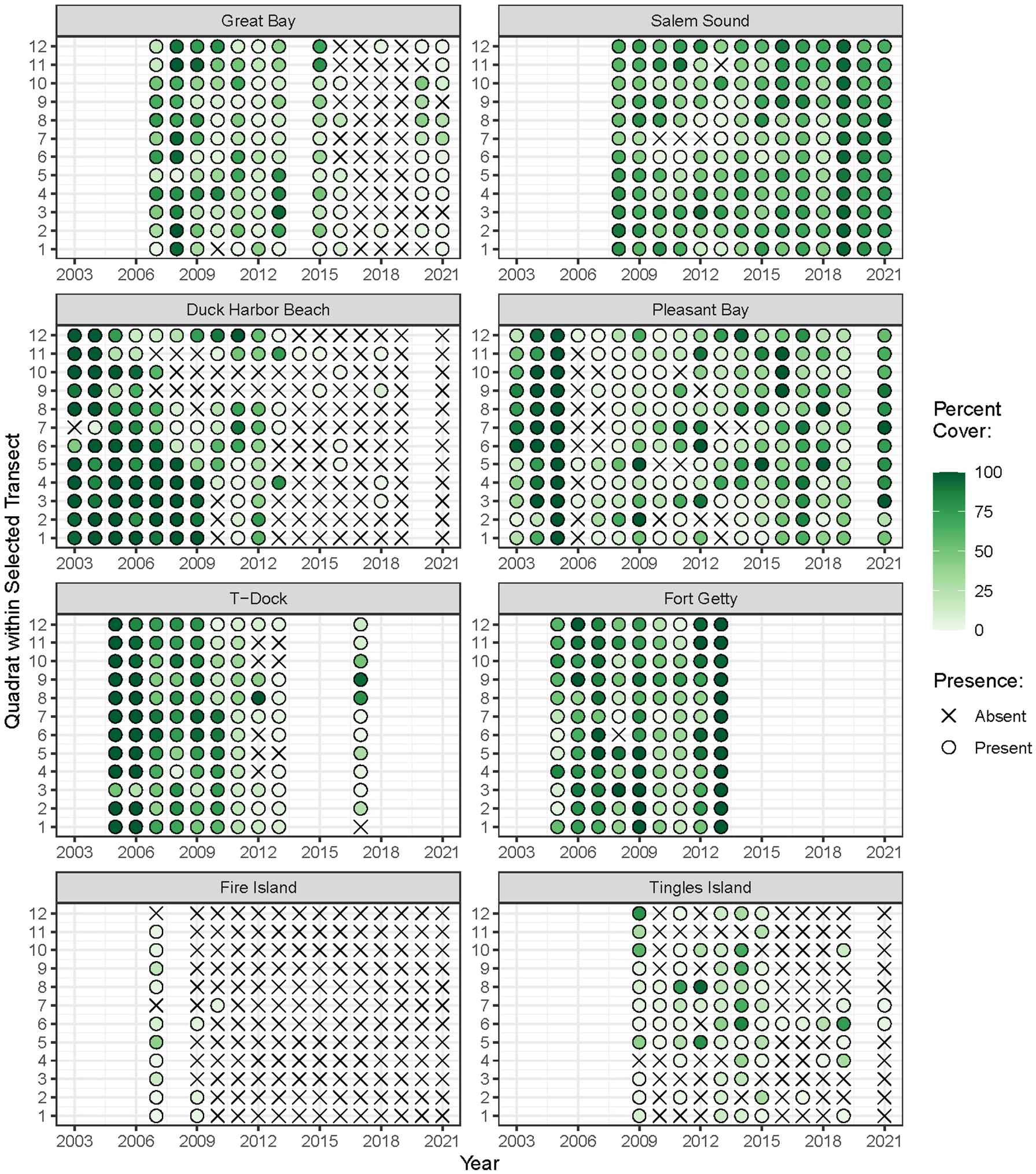

Eelgrass was monitored annually at most sites over nine- to 17-year periods between 2003 and 2021. The years in which monitoring occurred varied among sites (Figure 2). We examined eelgrass percent cover as an abundance metric that integrates shoot density and canopy height, measured during the season of peak biomass. Although widgeongrass (Ruppia maritima) grows throughout the region, it was present in only three sites and was therefore excluded from quantitative analyses. To standardize depth among sites and control for the effect of light availability, we restricted our analyses to the shallowest transect at which eelgrass occurred at each site.

Figure 2

Monitoring years and percent cover of eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) within each quadrat over time. Absence of plant cover is depicted with an × symbol.

Water Temperature

Continuous temperature records were obtained from various sources either within or near the eight SeagrassNet sites. Temperature was measured directly within four of the sites using temperature loggers (Onset Computer Co. Onset, MA) deployed near the substrate surface at one end of the shallow transect. At the other four sites, water temperature records from nearby locations representative of the monitoring stations were acquired through publicly available internet sources (Table 1). We investigate the effect of the previous year’s mean summer (June 1 – August 31) water temperature on eelgrass percent cover. Evidence suggests that the negative effects of high thermal stress on eelgrass persists into the following growing season (Lefcheck et al., 2017). Daily mean summer temperatures were derived from the continuous temperature records. This level of aggregation was necessary to account for different temperature sampling intervals among sites. Annual summer mean water temperatures were then calculated for each site using the daily mean records. Additionally, to control for the confounding effect of latitude on water temperature, and the likely adaptation of eelgrass to local temperature (DuBois et al., 2022), summer water temperatures within each site were centered prior to modeling (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Eelgrass percent cover varied on a near-continuous interval from 0 to 100% (i.e., [0,1]) across all quadrats and sites during the period of interest. All instances of percent cover measurements equal to 1 were converted to 0.99 for model parsimony because there is not a meaningful ecological difference between the two values. However, since there is an ecologically important distinction between absence (percent cover = 0) and presence (percent cover > 0) of eelgrass, we used a hurdle model to accommodate the presence of zeros in the data (Cragg, 1971; Potts and Elith, 2006). This modeling framework has the added benefit of allowing for inference on two separate ecologically meaningful processes related to eelgrass: presence and abundance.

The hurdle model presence and abundance component consisted of a generalized additive mixed model (GAMM) with binomial and beta response distributions, respectively. Each mean response was modeled as a smooth function [denoted s(·)] of both year and the centered average water temperature in the preceding year using thin-plate regression splines (Wood, 2003). Site and quadrat were included as nested random effects to account for unmeasured differences (heterogeneity) among SeagrassNet sites. The full model specification and model diagnostics are included in Supplemental Material.

All analyses were carried out using the R Statistical Computing Environment (R Core Team, 2021). Each hurdle model component GAMM was fit using the mgcv package (Wood, 2011; Wood et al., 2016) and visualized using the gratia package (Simpson, 2021).

Results

Summary of Eelgrass Cover and Site Temperature

The time-periods in which eelgrass cover was surveyed varied across the region. All sites but one had at least 10 years of eelgrass data. Average eelgrass percent cover over all years of monitoring across the region ranged from 0 to 100 percent and averaged 34.5 percent. The frequency of eelgrass presence/absence along a transect fluctuated over the sample years within sites, with some sites having relatively infrequent observations of eelgrass presence and chronically low to no cover (Figure 2).

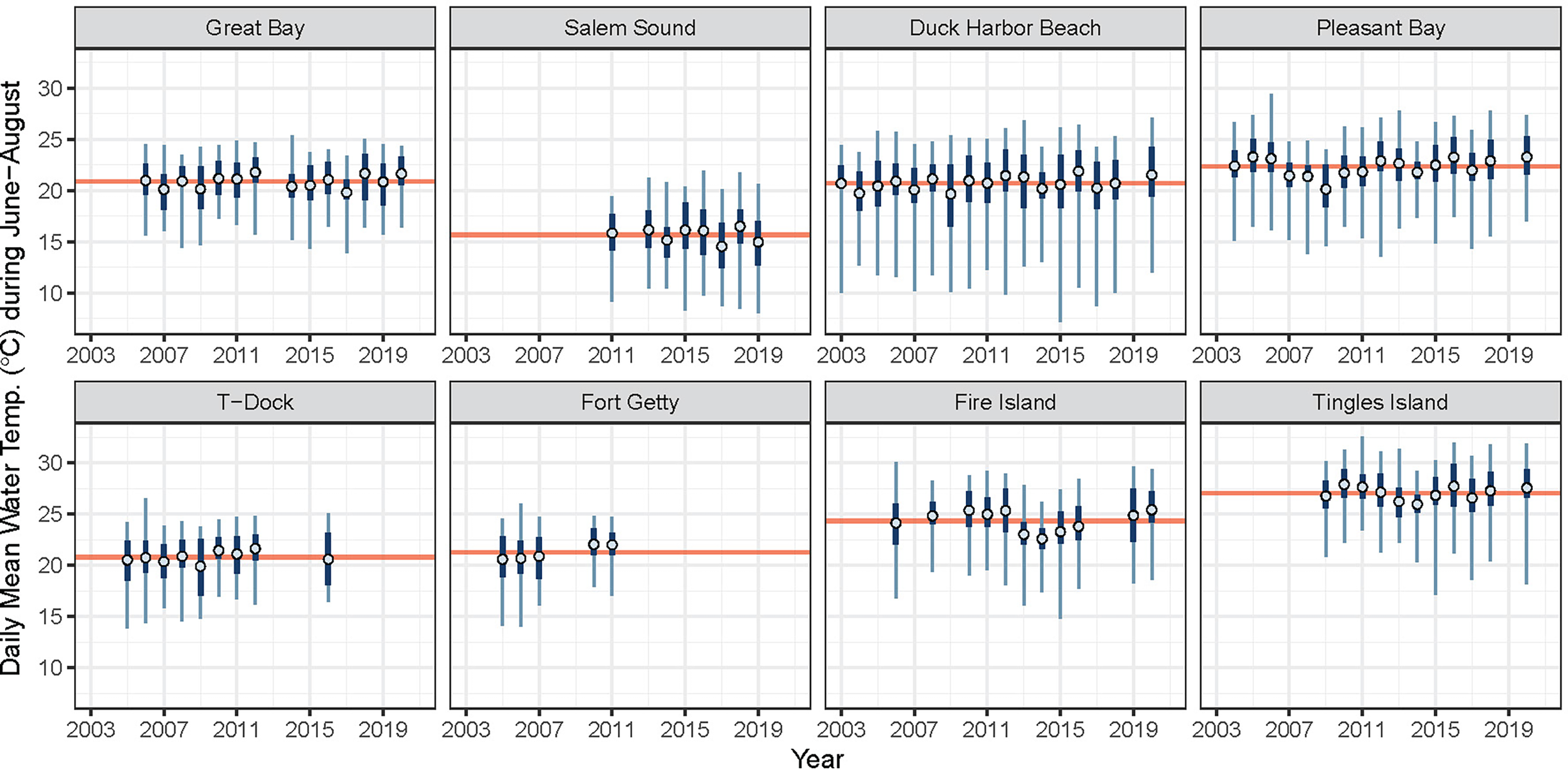

Site mean summer temperature across the region ranged from 15.7°C (Salem Sound) to 27.0°C (Tingles Island) (Table 1). Figure 3 illustrates the variability in summer temperature across the region and shows that the range of summer temperature is narrower in some sites than others.

Figure 3

Average daily mean water temperature during June-August each year (blue open circle) for associated years in which eelgrass cover was surveyed. Interquartile range and range of observed daily mean water temperatures are plotted in dark and light blue, respectively. The time period average (mean of all daily means) is plotted as horizontal red line. Water temperature data were not available for all years at all sites. Displayed here are only the temperature records used in the analysis.

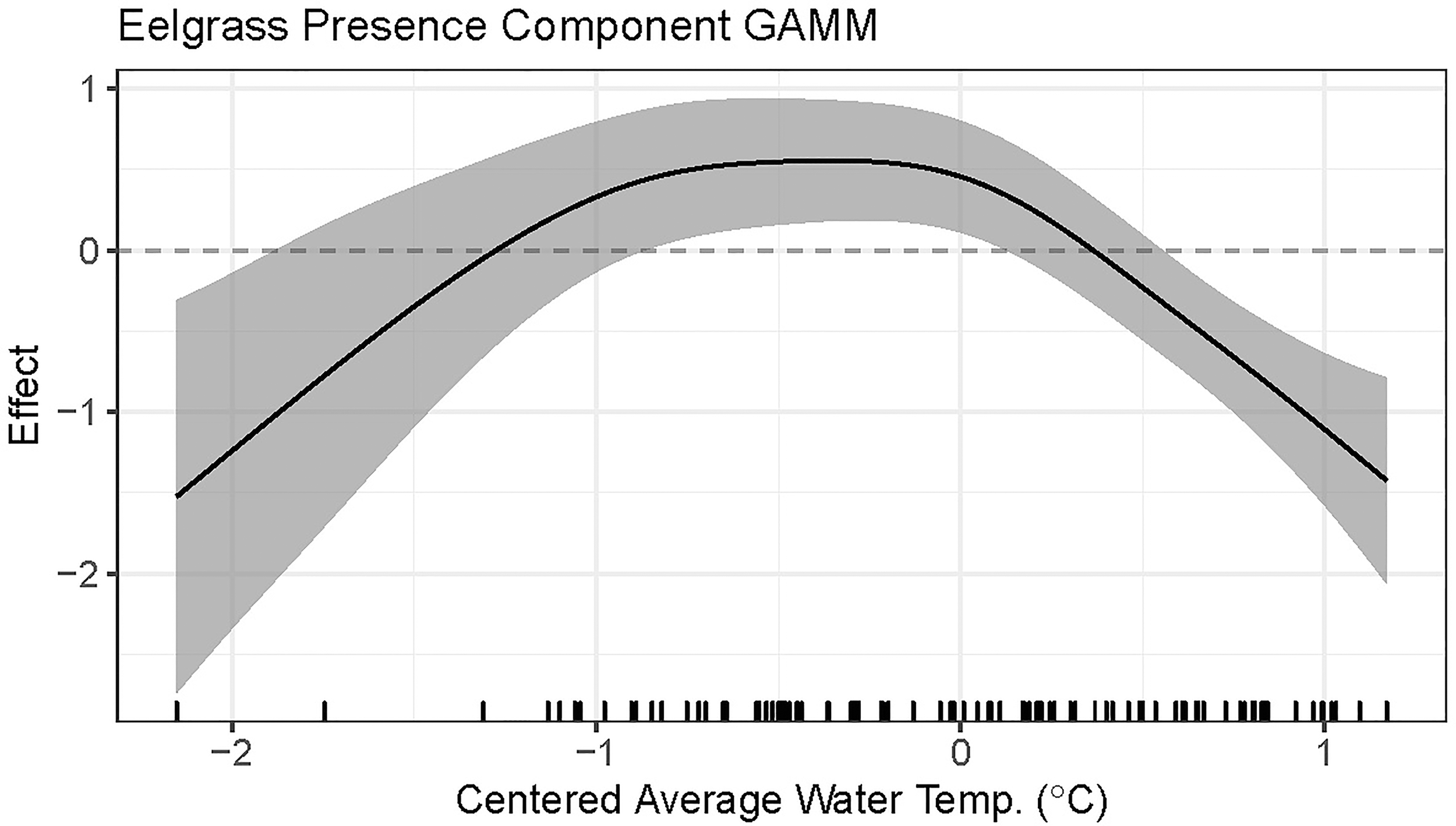

GAMM

Centered average water temperature in the preceding year was found to be a statistically significant nonlinear predictor of eelgrass presence in the following year (approximate p-value < 0.0001, Table 2). For preceding years that are hotter than average (i.e., greater than the time-period average), an increase in average summer water temperature by 0.5°C or more for that year is associated with a linear decrease in the predicted probability of eelgrass presence the subsequent year (Figure 4). Cooler than average temperatures in the preceding year, down to approximately 0.5°C below the time-period average, are associated with the highest predicted probability of eelgrass presence. For eelgrass abundance, however, centered average water temperature in the preceding year was not found to be a statistically significant predictor (approximate p-value = 0.7820, Table 3).

Table 2

| Parametric coefficients: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

| Intercept | 1.54 | 0.89 | 1.73 | 0.0842 |

| Approximate significance of smooth terms: | ||||

| edf | Referencedf | χ2Statistic | p-value | |

| s(Site) | 6.74 | 7 | 252.87 | < 0.0001 |

| s(Quadrat within Site) | 13.64 | 95 | 17.66 | 0.0653 |

| s(Centered Avg. Temperature) | 2.89 | 9 | 377.17 | < 0.0001 |

| s(Year) | 4.50 | 9 | 1292.77 | < 0.0001 |

| Standard deviations of random effects: | ||||

| Std. Deviation | ||||

| s(Site) | 2.47 | |||

| s(Quadrat within Site) | 0.39 | |||

| Deviance explained = 45.5% | ||||

| n = 1092 | ||||

Eelgrass presence/absence component GAMM (binomial response distribution with logit link function) summary.

Figure 4

Plot of the presence component GAMM fitted smooth with 95% confidence interval for the effect of centered average water temperature in the preceding year on eelgrass presence.

Table 3

| Parametric coefficients: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

| Intercept | -0.27 | 0.26 | -1.06 | 0.2880 |

| Approximate significance of smooth terms: | ||||

| edf | Referencedf | χ2 Statistic | p-value | |

| s(Site) | 6.66 | 7 | 98.61 | < 0.0001 |

| s(Quadrat within Site) | 0.00 | 93 | 0.00 | 0.8490 |

| s(Centered Avg. Temperature) | 0.00 | 9 | 0.00 | 0.7820 |

| s(Year) | 3.79 | 9 | 1464.38 | < 0.0001 |

| Standard deviations of random effects: | ||||

| Std. Deviation | ||||

| s(Site) | 0.71 | |||

| s(Quadrat within Site) | 0.00 | |||

| Deviance explained = 33.9% | ||||

| n = 713 | ||||

Eelgrass abundance, given presence, component GAMM (beta response distribution with logit link function) summary.

Discussion

We analyzed eight monitoring data sets from locations along a latitudinal gradient in the Northeastern USA to investigate associations between summer water temperature and eelgrass presence and abundance on a regional scale. We found that above average summer temperatures corresponded to a decreased probability of eelgrass presence (and increased probability of eelgrass absence) the following year. Our results showed that temperatures down to 0.5°C below the site average, corresponded to the highest probability of eelgrass presence. In contrast, we detected no association between eelgrass abundance (when present) and prior summer average temperature. However, eelgrass must survive to grow, so the lack of a statistically significant association between eelgrass abundance and prior year summer temperature cannot be taken outside of the context of the negative association between eelgrass presence and average summer temperature and highlights the importance of considering multiple fitness metrics when assessing species’ response to temperature (Hughes et al., 2019). Overall, these findings suggest eelgrass meadows in the Northeast USA are vulnerable to warming and, further, this vulnerability increases as water temperatures rise above the summer mean.

The recovery of seagrass meadows following disturbances can vary greatly, depending on the resilience of the meadow, (i.e., its ability to absorb changes and continue to persist; Holling, 1973). Even when water temperatures are below thermal thresholds, high temperature can interact with other stressors to exacerbate declines and prevent recovery. Because more light is required at higher temperatures for eelgrass to maintain a positive carbon balance (Marsh et al., 1986; Moore et al., 1997; Staehr and Borum, 2011; Beca-Carretero et al., 2018), light limitation and temperature increases can combine to cause eelgrass declines (Moore et al., 2014). Salo and Pedersen (2014) found that synergistic effects of high temperature and low salinity resulted in higher eelgrass mortality rates and lower leaf production. Additionally, Neckles et al. (1993) showed that high summer temperatures exacerbated the negative effects of epiphytes on eelgrass growth. As water temperatures continue to increase, these types of negative interactions are likely to worsen. The light experienced by eelgrass at the different SeagrassNet sites is influenced by water depth, tidal range, and water quality. Management actions that aim to improve water quality and clarity may also increase eelgrass resilience to higher temperatures.

In addition, ecological feedback mechanisms play a major role in the resilience of seagrass ecosystems (Maxwell et al., 2017). The degradation of seagrass meadows, and subsequent loss of self-reinforcing feedbacks (wherein seagrasses create conditions promoting further seagrass growth), can lead to a positive feedback loop in which recovery capacity is reduced, which can lead to conditions that are unsuitable for seagrass (Duarte et al., 2009). Thus, the ecological consequences of reduced eelgrass presence with higher-than-average summer temperature may differ considerably among meadows with chronically high versus low eelgrass presence. Moreover, eelgrass meadows of the Northeast USA are part of seascapes and exist as metapopulations (Olsen et al., 2004). Connectivity among populations is critical for sustaining the eelgrass resources and the ecological services they provide at the local and regional scale (Kendrick et al., 2012). To prevent irreversible eelgrass losses as waters warm, proactive management actions are needed such as transplanting or seeding declining meadows with heat-tolerant genotypes and reducing synergistic stressors such as reduced light due to nutrient loading or turbidity from coastal construction, as well as mechanical disturbance to the bottom (such as dock construction over eelgrass or fishing practices that involve dredging or dragging gear along the seafloor; Neckles et al., 2005).

An important component of future targeted management actions to enhance eelgrass resilience to warming may include transplanting and seeding of genotypes that are more tolerant to warm waters into areas experiencing declines (Björk et al., 2008; Unsworth et al., 2015). For instance, Plaisted et al. (2020) planted eelgrass shoots collected from multiple populations into mesocosms and found resilience to reduced light and increased sediment organic matter to be positively associated with source population genetic diversity. Transplant and seeding of heat tolerant genotypes should occur at the seascape scale (de la Torre-Castro et al., 2014; Unsworth et al., 2015). For example, the distribution of eelgrass over a large latitudinal temperature gradient within the northeast region suggests southerly populations, adapted to warmer conditions, could boost resiliency at northern sites. However, a study of the seagrass species Posidonia oceanica found that transplants originating from the cool-edge of the thermal range performed equally well to warm-edge transplants when transplanted into the warm-edge of the thermo-geographical range, suggesting cool-edge seagrass populations may be more resilient to warming than expected (Bennett et al., 2022). Transplanting of eelgrass to areas that natural dispersal is rare or nonexistent raises other concerns which include spreading non-native epibiont species (Carman and Grunden, 2010) and disease (Groner et al., 2016). Also, eelgrass from southerly locations is potentially adapted to latitudinal gradients other than temperature, such as day length or seasonality (Clausen and Clausen, 2013; Clausen et al., 2014; Jueterbock et al., 2021).Finally, eelgrass restoration has experienced low success rates due to a variety of factors, including high seed loss due to seed predation and bioturbation, and high seedling mortality due to light availability and physical disturbances, as examples (Infantes et al., 2016).

Local-scale mosaics in environmental stress can also lead to gradients in heat-tolerance among eelgrass meadows (DuBois et al., 2022). Importantly, these local temperature mosaics are disassociated from latitudinal gradients (Helmuth et al., 2006) and can occur over spatial scales within the natural dispersal range of eelgrass and eelgrass associated species. For example, in our study, eelgrass in Great Bay, NH experiences average mean summertime temperatures 5°C warmer than Salem Sound, MA despite its more northerly locale and thus could be a possible source of heat-tolerant eelgrass. The potential for local-scale population differentiation to buffer the effects of warming without the same potential pitfalls of transplanting eelgrass across larger geographic distances highlights the importance of identifying local phenotypic variation among meadows and protecting eelgrass populations that span a variety of environmental conditions within regions. To identifyi gradients of heat-tolerance, monitoring of seagrass presence, abundance and distribution, as well as water temperature must occur at wider spatial scales than that which we present here.

Temperature stress may also result in distribution shifts of seagrass species. For example, Shields et al. (2019) documented a shift in species composition from eelgrass to a more transient sub-dominant species, Ruppia maritima (widgeongrass) in response to increasing summer temperature regimes. Although not included in the present study, increases in widgeongrass following eelgrass declines at both Tingles Island, MD and Fire Island, NY have been observed (Peck and Plaisted, in prep.). These two species co-occur in many areas, and widgeongrass has a higher optimum growth temperature (Evans et al., 1986); therefore, it has the potential to expand into areas where eelgrass recovery is limited by stressful water temperatures. Widgeongrass expansion has been documented in a variety of systems where it co-occurs with eelgrass, including San Diego, CA (Johnson et al., 2003), northwest Mexico (Lopez-Calderon et al., 2010), and the Chesapeake Bay (Shields et al., 2018; Richardson et al., 2018). The ability of widgeongrass to at least temporarily replace eelgrass after its decline may be a crucial mechanism of resiliency for these seagrass meadows. Widgeongrass ecosystem functions, including trapping sediment and improving water clarity, may create a positive feedback loop for the recolonization of eelgrass, though the extent to which this occurs remains an important area of research.

Although our study was limited by the data that were available, our results indicate that eelgrass presence on a regional scale is threatened by warming waters. Furthermore, differences in mean eelgrass presence and abundance among sites coupled with the known importance of self-reinforcing feedbacks in seagrass ecosystems (Duarte et al., 2009; Maxwell et al., 2017) suggests that sites with greater eelgrass presence and abundance may be more resilient to temperature stress than sites with chronically low eelgrass metrics. Proactive seeding of vulnerable sites with heat-tolerant eelgrass may be an important tool to combat eelgrass losses associated with rising temperatures in the Northeast USA. These topics warrant future research including continued regional monitoring of seagrass and water temperature at temporal and spatial scales necessary to answer both local and seascape level questions (Unsworth et al., 2019; Neckles et al., 2012). In summary, by using yearly percent cover data paired with high frequency temperature data, we were able to assess the impacts of warming on this important foundation species at a regional scale. Predictions of future response to dominant driving variables under warming conditions and factors limiting recovery are needed for managers to identify and minimize vulnerability to loss or degradation and reverse declining trajectories of seagrass ecosystems.

Conclusion

Our study exemplifies the value of long-term monitoring in tracking change in seagrass meadows and relating patterns to key drivers. The factors leading to eelgrass presence and abundance are complex, though our finding of reduced eelgrass presence with increased summer temperature supports other work linking eelgrass loss to additive effects of high thermal stress (Lefcheck et al., 2017). Discussion of the management action needed to improve the success of eelgrass must include an awareness of the role of temperature in exacerbating other stressors.

Funding

Funding for various aspects of SeagrassNet were provided by The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Oak Foundation, the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation and Tom Haas, and the University of New Hampshire. Funding for the herein analysis and manuscript was provided by the Northeast Coastal and Barrier Inventory and Monitoring Network of the US National Park Service.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://datadryad.org/stash/share/sRVnIbj397_nghEFD9DdVGSbqjHwVVM85bmBZyZl9DM.

Author contributions

HP, ES, AN, CP, and FS contributed to study conception, data compilation and analysis, conception of tables and figures, results interpretation and manuscript writing. PD contributed to statistical analyses, results interpretation and writing. JC, NE, SF, SH, RH, KM, BN, BP, FTS, and AT contributed to study conception, results interpretation, and writing. TM and DP contributed results interpretation and writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many staff, interns, researchers, and students who contributed to the collection of the data used in this collaborative project. Thanks also to the organizations for their support in implementing and maintaining SeagrassNet monitoring sites in the Northeast USA: University of New Hampshire; Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership; Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries; Save The Bay, Rhode Island; Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve; US National Park Service: Northeast Coastal and Barrier Network, Cape Cod National Seashore, Fire Island National Seashore, and Assateague Island National Seashore. Thank you to Sara Stevens for initial review and editing. We especially thank Drs Hilary Neckles and Blaine Kopp formerly of the US Geological Survey for establishing four SeagrassNet sites, and Dr. Neckles specifically for her leadership in the initial conception of this paper, as well as her dedication to maintaining the seagrass monitoring program at Cape Cod National Seashore and advancing seagrass monitoring, research and management throughout the Northeast USA.

Conflict of interest

Authors CP and PD are employed by Neptune and Company, Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.920699/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alexander M. A. Scott J. D. Friedland K. D. Mills K. E. Nye J. A. Pershing A. J. et al . (2018). Projected Sea Surface Temperatures Over the 21st Century: Changes in the Mean, Variability and Extremes for Large Marine Ecosystem Regions of Northern Oceans. Elem Sci. Anth6, 9. doi: 10.1525/elementa.191

2

Beca-Carretero P. Olesen B. Marbà N. Krause-Jensen D. (2018). Response to Experimental Warming in Northern Eelgrass Populations: Comparison Across a Range of Temperature Adaptations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.589, 59–72. doi: 10.3354/meps12439

3

Bennett S. Alcoverro T. Kletou D. Antoniou C. Boada J. Buñuel X. et al . (2022). Resilience of Seagrass Populations to Thermal Stress Does Not Reflect Regional Differences in Ocean Climate. New Phytol.233, 1657–1666. doi: 10.1111/nph.17885

4

Bindoff N. L. IPCC Willebrand J. Artale V. Cazenave A. Gregory J. M. Gulev S. et al (2007). “Climate Change,” in The Physical Science Basis. Ed. SolomonS.et alet al, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press), 385−428.

5

Binzer T. Borum J. Pedersen O. (2005). Flow Velocity Affects Internal Oxygen Conditions in the Seagrass Cymodocea nodosa. Aquat. Botany.83, 239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2005.07.001

6

Björk M. Short F. T. Mcleod E. Beer S. (2008). Managing Seagrasses for Resilience to Climate Change (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN), 56pp.

7

Carman M. R. Grunden D. W. (2010). First Occurrence of the Invasive Tunicate Didemnum Vexillum in Eelgrass Habitat. Aquat. Invasions5, 23–29. doi: 10.3391/ai.2010.5.1.4

8

Clausen K. K. Clausen P. (2013). Earlier Arctic Springs Cause Phenological Mismatch in Long-Distance Migrants. Oecologia173, 1101–1112. doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2681-0

9

Clausen K. K. Krause-Jensen D. Olesen B. Marbà N. (2014). Seasonality of Eelgrass Biomass Across Gradients in Temperature and Latitude. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.506, 71–85. doi: 10.3354/meps10800

10

Collier C. Waycott M. (2014). Temperature Extremes Reduce Seagrass Growth and Induce Mortality. Mar. pollut. Bull.83 (2), 483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.03.050

11

Cragg J. G. (1971). Some Statistical Models for Limited Dependent Variables With Application to the Demand for Durable Goods. Econometrica J. Econometric Soc., 39, 829–844. doi: 10.2307/1909582

12

de la Torre-Castro M. Di Carlo G. Jiddawi N. S. (2014). Seagrass Importance for a Small-Scale Fishery in the Tropics: The Need for Seascape Management. Mar. pollut. Bull.83, 398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.03.034

13

Díaz-Almela E. Marbà N. Martínez R. Santiago R. Duarte C. (2009). Seasonal Dynamics of Posidonia oceanica in Magalluf Bay (Mallorca, Spain): Temperature Effects on Seagrass Mortality. Limnol. Oceanogr.54, 2170–2182. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.54.6.2170

14

Doney S. C. Mary Ruckelshaus M. Duffy J. E. Barry J. P. Chan F. English C. A. et al . (2012). Climate Change Impacts on Marine Ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.4, 11–37. :1. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-041911-111611

15

Duarte C. M. Conley D. J. Carstensen J. S´anchez-Camacho M. (2009). Return to Neverland: Shifting Baselines Affect Eutrophication Restoration Targets. Estuaries Coasts32 (5), 29–36. doi: 10.1007/s12237-008-9111-2

16

DuBois K. Pollard K. N. Kauffman B. J. Williams S. L. Stachowicz J. J. (2022). Local Adaptation in a Marine Foundation Species: Implications for Resilience to Future Global Change. Global Change Biol.00, 1–15. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16080

17

Dunic J. C. Brown C. J. Connolly R. M. Turschwell M. P. Côté I. M. (2021). Long-Term Declines and Recovery of Meadow Area Across the World’s Seagrass Bioregions. Glob. Change Biol.27, 4096–4109. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15684

18

Durako M. J. Howarth J. F. (2017). Leaf Spectral Reflectance Shows Thalassia testudinum Seedlings More Sensitive to Hypersalinity Than Hyposalinity. Front. Plant Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01127

19

Ehlers A. Worm B. Reusch B. H. (2008). Importance of Genetic Diversity in Eelgrass (Zostera marina) for its Resilience to Global Warming. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.355, 1–7. doi: 10.3354/meps07369

20

Evans A. S. Webb K. L. Penhale P. A. (1986). Photosynthetic Temperature Acclimation in Two Coexisting Seagrasses, Zostera marina L. And Ruppia maritima L. Aquat. Bot.24, 185–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(86)90095-1

21

Fourqurean J. W. Duarte C. M. Kennedy H. Marbà N. Holmer M. Mateo M. A. et al . (2012). Seagrass Ecosystems as a Globally Significant Carbon Stock. Nat. Geosci.5, 505–509. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1477

22

Gerakaris V. Lardi P. Issaris Y. (2020). First Record of the Tropical Seagrass Species Halophila decipiens Ostenfeld in the Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Bot.Volume 160. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2019.103151

23

Green E. P. Short F. T. (Eds.) (2003). World Atlas of Seagrasses (Berkeley: University of California Press).

24

Greve T. M. Borum J. Pedersen O. (2003). Meristematic Oxygen Variability in Eelgrass (Zostera marina). Limnology Oceanography48, 210–216. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.1.0210

25

Groner M. L. Maynard J. Breyta R. Carnegie R. B. Dobson A. Friedman C. S. et al . (2016). Managing Marine Disease Emergencies in an Era of Rapid Change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci.371 (1689), 20150364. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0364

26

Hall M. Furman B. Merello M. Durako M. (2016). Recurrence of Thalassia testudinum Seagrass Die-Off in Florida Bay, USA: Initial Observations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.560, 243–249. doi: 10.3354/meps11923

27

Hartmann D. L. Klein Tank A. M. G. Rusticucci M. Alexander L. V. Brönnimann S. Charabi Y. et al . (2013). “Chapter 2: Observations: Atmosphere and Surface”, in IPCC AR5 WG1 2013, 159–254.

28

Helmuth B. Broitman B. R. Blanchette C. A. Gilman S. Halpin P. Harley C. D. G. et al . (2006). Mosaic Patterns of Thermal Stress in the Rocky Intertidal Zone: Implications for Climate Change. Ecol. Monogr.76, 461–479. doi: 10.1890/0012-9615(2006)076[0461:MPOTSI]2.0.CO;2

29

Holling C. S. (1973). Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.4, 1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

30

Hughes A. R. Hanley T. C. Moore A. F. P. Ramsay-Newton C. Zerebecki R. A. Sotka E. E. (2019). Predicting the Sensitivity of Marine Populations to Rising Temperatures. Front. Ecol. Environ.17 (1), 17–24. doi: 10.1002/fee.1986

31

Infantes E. Eriander L. Moksnes P. O. (2016). Eelgrass (Zostera marina) Restoration on the West Coast of Sweden Using Seeds. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.546, 31–45. doi: 10.3354/meps11615

32

IPCC (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. Eds. Masson-DelmotteV.ZhaiP.PörtnerH. O.RobertsD.SkeaJ.ShuklaP. R.PiraniA.Moufouma-OkiaW.PéanC.PidcockR.ConnorsS.MatthewsJ. B. R.ChenY.ZhouX.GomisM. I.LonnoyE.MaycockT.TignorM.WaterfieldT.

33

Johnson M. R. Williams S. L. Lieberman C. H. Solbak A. (2003). Changes in the Abundance of the Seagrasses Zostera marina L. (Eelgrass) and Ruppia maritima L. (Widgeongrass) in San Diego, California, Following an El Niño Event. Estuaries26 (1), 106–115.

34

Jordà G. Marbà N. Duarte C. (2012). Mediterranean Seagrass Vulnerable to Regional Climate Warming. Nat. Clim. Change2, 821–824. doi: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1533

35

Jueterbock A. Duarte B. Coyer J. Olsen J. L. Kopp M. E. L. Smolina I. et al . (2021). Adaptation of Temperate Seagrass to Arctic Light Relies on Seasonal Acclimatization of Carbon Capture and Metabolism. Front. Plant Sci.Vol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.745855

36

Karmalkar A. V. Horton R. M. (2021). Drivers of Exceptional Coastal Warming in the Northeastern United States. Nat. Clim. Change11, 854–860. doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-01159-7

37

Kendrick G. A. Waycott M. Carruthers T. J. B. Cambridge M. L. Hovey R. Krauss S. L. et al . (2012). The Central Role of Dispersal in the Maintenance and Persistence of Seagrass Populations. Bioscience62, 56–65. doi: 10.1525/bio.2012.62.1.10

38

Koch M. S. Erskine J. M. (2001). Sulfide as a Phytotoxin to the Tropical Seagrass Thalassia testudinum: Interactions With Light, Salinity and Temperature. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.266, 81–95. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(01)00339-2

39

Lamb J. Van de Water J. Bourne D. Altier C. Hein M. Fiorenza E. et al . (2017). Seagrass Ecosystems Reduce Exposure to Bacterial Pathogens of Humans, Fishes, and Invertebrates. Science355, 731. doi: 10.1126/science.aal1956

40

Lee K. S. Park S. Kim Y. (2007). Effects of Irradiance, Temperature, and Nutrients on Growth Dynamics of Seagrasses: A Review. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecology.350, 144–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2007.06.016

41

Lefcheck J. S. Wilcox D. J. Murphy R. R. Marion S. R. Orth R. J. (2017). Multiple Stressors Threaten the Imperiled Coastal Foundation Species Eelgrass (Zostera marina) in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Global Change Biol.23 (9), 3474–3483. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13623

42

LIShore (Accessed 12 February 2021). (2021) A project of the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University in collaboration with the LIShore partners.

43

Lopez-Calderon J. Riosmena-Rodríguez R. Rodríguez-Baron J. M. Carrión-Cortez J. Torre J. Meling-López A. et al . (2010). Outstanding Appearance of Ruppia maritima Along Baja California Sur, México and Its Influence in Trophic Networks. Mar. Biodiversity40 (4), 293–300. doi: 10.1007/s12526-010-0050-3

44

Marsh J. A. Dennison W. C. Alberte R. S. (1986). Effects of Temperature on Photosynthesis and Respiration in Eelgrass (Zostera marina L.). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.101, 257–267. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(86)90267-4

45

Maxwell P. S. Eklöf J. S. van Katwijk M. M. O’Brien K. R. de la Torre-Castro M. Boström C. et al . (2017). The Fundamental Role of Ecological Feedback Mechanisms for the Adaptive Management of Seagrass Ecosystems—a Review. Biol. Rev.92, 1521–1538. doi: 10.1111/brv.12294

46

Moksnes P. O. Eriander L. Infantes E. Holmer M. et al . (2018). Local Regime Shifts Prevent Natural Recovery and Restoration of Lost Eelgrass Beds Along the Swedish West Coast. Estuaries Coasts41, 1712–1731. doi: 10.1007/s12237-018-0382-y

47

Moore K. A. Jarvis J. C. (2008). Environmental Factors Affecting Recent Summertime Eelgrass Diebacks in the Lower Chesapeake Bay: Implications for Long-Term Persistence. J. Coast. Res.55, 135–147. doi: 10.2112/SI55-014

48

Moore K. A. Shields E. C. Parrish D. B. (2014). Impacts of Varying Estuarine Temperature and Light Conditions on Zostera marina (Eelgrass) and Its Interactions With Ruppia maritima (Widgeongrass). Estuaries Coasts37, 20–30. doi: 10.1007/s12237-013-9667-3

49

Moore K. A. Short F. T. Orth R. J. Duarte C. M. , (2006). “Zostera: Biology, Ecology, and Management,” in Seagrasses: Biology, Ecology and Conservation. Ed. LarkumA. W. D.et al (Dordrecht: Springer), 323–345.

50

Moore K. A. Wetzel R. L. Orth R. J. (1997). Seasonal Pulses of Turbidity and Their Relations to Eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) Survival in an Estuary. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.215, 115–134. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(96)02774-8

51

Neckles H. A. Kopp B. S. Peterson B. J (2012). Integrating Scales of Seagrass Monitoring to Meet Conservation Needs. Estuaries Coasts35, 23–46. doi: 10.1007/s12237-011-9410-x

52

Neckles H. A. Short F. T. Barker S. Kopp B. S. (2005). Disturbance of Eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) by Commercial Mussel (Mytilus Edulis) Harvesting Inmaine: Dragging Impacts and Habitat Recovery. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.285, 57–73. doi: 10.3354/meps285057

53

Neckles H. A. Wetzel R. L. Orth R. J. Pooler P. (1993). Relative Effects of Nutrient Enrichment and Grazing on Epiphyte-Macrophyte (Zostera marina L.) Dynamics. Oecologia93 (2), 285–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00317683

54

Nejrup L. Pedersen M. (2008). Effects of Salinity and Water Temperature on the Ecological Performance of Zostera marina. Aquat. Botany.88, 239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.10.006

55

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) (2016a) Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature (ERSST.V4) ( National Centers for Environmental Information). Available at: www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/marineocean-data/extended-reconstructed-sea-surface-temperature-ersst (Accessed March 2016).

56

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) (2016b) NOAA Merged Land Ocean Global Surface Temperature Analysis (NOAAGlobalTemp): Global Gridded 5° X 5° Data ( National Centers for Environmental Information). Available at: www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/marineocean-data/noaa-global-surface-temperature-noaaglobaltemp (Accessed June 2016)

57

NOAA National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS) (2021) System-Wide Monitoring Program. Data Accessed From the NOAA NERRS Centralized Data Management Office Website. Available at: http://www.nerrsdata.org (Accessed 12 February 2021).

58

Northeastern Regional Association of Coastal Ocean Observing Systems (NERACOOS) Graduate School of Oceanography, Marine Ecosystems Research Laboratory ( University of Rhode Island). Available at: http://www.neracoos.org/erddap/tabledap/URI_169-QP_SurfaceSonde.graph (Accessed February 2021).

59

Nowicki R. Thomson J. Burkholder D. Fourqurean J. Heithaus M. (2017). Predicting Seagrass Recovery Times and Their Implications Following an Extreme Climate Event. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.567, 79–93. doi: 10.3354/meps12029

60

O’Brien K. R. Waycott M. Maxwell P. Kendrick G. A. Udy J. W. Ferguson A. J. P. et al . (2018). Seagrass Ecosystem Trajectory Depends on the Relative Timescales of Resistance, Recovery and Disturbance. Mar. pollut. Bull.Volume 134, 166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.09.006

61

Oczkowski A. McKinney R. Ayvazian S. Hanson A. Wigand C. Markham E. (2015). Preliminary Evidence for the Amplification of Global Warming in Shallow, Intertidal Estuarine Waters. PloS One10 (10), e0141529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141529

62

Olsen J. L. Stam W. T. Coyer J. A. Reusch T. B. H. Billingham M. Boström C. et al . (2004). North Atlantic Phylogeography and Large-Scale Population Differentiation of the Seagrass Zostera marina L. Mol. Ecol.13, 1923–1941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02205.x

63

Orth R. J. Carruthers T. J. B. Dennison W. C. Duarte C. M. Fourqurean J. W. Heck K. L. J. et al . (2006). A Global Crisis for Seagrass Ecosystems. Bioscience56 (12), 987–996. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[987:AGCFSE]2.0.CO;2

64

Parmesan C. Yohe G. (2003). A Globally Coherent Fingerprint of Climate Change Impacts Across Natural Systems. Nature421, 37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286

65

Peck C. P. Plaisted H. K. “Northeast Coastal and Barrier I&M Network Parks: Estuarine Nutrient Enrichment Monitoring Data Summary and Trend Analysis,” in Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NCBN/NRDS—TBD (Fort Collins, Colorado: National Park Service).

66

Plaisted H. K. Novak A. B. Weigel S. Short F. T. (2020). Correction to: Eelgrass Genetic Diversity Influences Resilience to Stresses Associated With Eutrophication. Estuaries Coasts43, 1584. doi: 10.1007/s12237-020-00696-2

67

Potts J. M. Elith J. (2006). Comparing Species Abundance Models. Ecol. Model.199 (2), 153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.05.025

68

Qin L. Kim S. H. Song H. Suonan Z. Kim H. Kwon O. et al . (2019). Influence of Regional Water Temperature Variability on the Flowering Phenology and Sexual Reproduction of the Seagrass Zostera marina in Korean Coastal Waters. Estuaries Coasts. 43, 449–462. doi: 10.1007/s12237-019-00569-3

69

R Core Team (2021). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.

70

Reusch T. B. H. Ehlers A. H. Hammerli A. Worm B. (2005). Ecosystem Recovery After Climatic Extremes Enhanced by Genotypic Diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. America102, 2826–2831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500008102

71

Reusch T. B. H. Schubert P. R. Marten S. M. Gill D. Karez R. Busch K. et al . (2021). Lower Vibrio Spp. Abundances in Zostera marina Leaf Canopies Suggest a Novel Ecosystem Function for Temperate Seagrass Beds. Mar. Biol.168, 149. doi: 10.1007/s00227-021-03963-3

72

Richardson J. P. Lefcheck J. S. Orth R. J. (2018). Warming Temperatures Alter the Relative Abundance and Distribution of Two Cooccurring Foundational Seagrasses in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.599, 65–74. doi: 10.3354/meps12620

73

Ruiz H. Ballantine D. L. Sabater H. (2017). Continued Spread of the Seagrass Halophila stipulacea in the Caribbean: Documentation in Puerto Rico and the British Virgin Islands. Gulf Caribb. Res.28, SC5–SC7. doi: 10.18785/gcr.2801.05

74

Salo T. Pedersen M. F. (2014). Synergistic Effects of Altered Salinity and Temperature on Estuarine Eelgrass (Zostera marina) Seedlings and Clonal Shoots. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.457, 143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2014.04.008

75

Seddon S. Connolly R. M. Edyvane K. S. (2000). Large-Scale Seagrass Dieback in Northern Spencer Gulf, South Australia. Aquat. Bot.66, 297–310. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3770(99)00080-7

76

Shields E. C. Moore K. A. Parrish D. B. (2018). Adaptations by Zostera marina Dominated Seagrass Meadows in Response to Water Quality and Climate Forcing. Diversity10 (4), 125. doi: 10.3390/d10040125

77

Shields E. C. Parrish D. Moore K. (2019). Short-Term Temperature Stress Results in Seagrass Community Shift in a Temperate Estuary. Estuaries Coasts42, 755–764. doi: 10.1007/s12237-019-00517-1

78

Short F. Coles R. Fortes M. Victor S. Salik M. Isnain I. et al . (2014). Monitoring in the Western Pacific Region Shows Evidence of Seagrass Decline in Line With Global Trends. Mar. pollut. Bull.83, 408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.03.036

79

Short F. T. Koch E. W. Creed J. C. Magalhães K. M. Fernandez E. Gaeckle J. L. (2006). SeagrassNet Monitoring Across the Americas: Case Studies of Seagrass Decline. Mar. Ecol.27, 277–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.2006.00095.x

80

Short F. T. McKenzie L. J. Coles R. G. Gaeckle J. L. (2005). SeagrassNet Manual for Scientific Monitoring of Seagrass Habitat – Caribbean Edition (Durham, NH, USA: University of New Hampshire), 74 pp. Available at: http://www.SeagrassNet.org.

81

Short F. T. Neckles H. A. (1999). The Effects of Global Climate Change on Seagrasses. Aquat. Bot.63, 169–196. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3770(98)00117-X

82

Short F. T. Wyllie-Echeverria S. (1996). Natural and Human-Induced Disturbance of Seagrasses. Environ. Conserv.23 (1), 17–27. doi: 10.1017/S0376892900038212

83

Simpson G. L. (2021) Gratia: Graceful ‘Ggplot’-Based Graphics and Other Functions for Gams Fitted Using ‘Mgcv’. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gratia.

84

Staehr P. A. Borum J. (2011). Seasonal Acclimation in Metabolism Reduces Light Requirements of Eelgrass (Zostera marina). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.407, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.05.031

85

Strydom S. Murray K. Wilson S. Huntley B. Rule M. Heithaus M. et al . (2020). Too Hot to Handle: Unprecedented Seagrass Death Driven by Marine Heatwave in a World Heritage Area. Glob. Change Biol.26, 3525–3538. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15065

86

Turschwell M. P. Connolly R. M. Dunic J. C. Sievers M. Buelow C. A. Pearson R. M. et al . (2021). Anthropogenic Pressures and Life History Predict Trajectories of Seagrass Meadow Extent at a Global Scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Nov118 (45), e2110802118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2110802118

87

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2020). Out of the Blue: The Value of Seagrasses to the Environment and to People (Nairobi: UNEP).

88

Unsworth R. K. Collier C. J. Waycott M. Mckenzie L. J. Cullen-Unsworth L. C. (2015). A Framework for the Resilience of Seagrass Ecosystems. Mar. pollut. Bull.100 (1), 34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.08.016

89

Unsworth R. K. F. McKenzie L. J. Collier C. J. Cullen-Unsworth L. C. Duarte C. M. et al . (2019). Global Challenges for Seagrass Conservation. Ambio48, 801–815. doi: 10.1007/s13280-018-1115-y

90

Unsworth R. K. F. Nordlund L. M. Cullen-Unsworth L. C. (2018). Seagrass Meadows Support Global Fisheries Production. Conserv. Lett. 12, e12566 doi: 10.1111/conl.12566

91

Waycott M. Duarte C. M. Carruthers T. J. B. Orth R. Dennison W. C. Olyarnike S. et al . (2009). Accelerating Loss of Seagrasses Across the Globe Threatens Coastal Ecosystems. PNAS106 (30), 12377–12381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905620106

92

Wilson S. S. Dunton K. H. (2018). Hypersalinity During Regional Drought Drives Mass Mortality of the Seagrass Syringodium filiforme in a Subtropical Lagoon. Estuaries Coasts41 (3), 855–865. doi: 10.1007/s12237-017-0319-x

93

Wilson K. L. Lotze H. K. (2019). Climate Change Projections Reveal Range Shifts of Eelgrass Zostera marina in the Northwest Atlantic. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.620, 47–62. doi: 10.3354/meps12973

94

Wood S. N. (2011). Fast Stable Restricted Maximum Likelihood and Marginal Likelihood Estimation of Semiparametric Generalized Linear Models. J. R. Stat. Society: Ser. B (Statistical Methodology)73 (1), 3–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2010.00749.x

95

Wood S. N. Pya N. Säfken B. (2016). Smoothing Parameter and Model Selection for General Smooth Models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.111 (516), 1548–1563. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2016.1180986

96

Wood S. N. (2003). Thin Plate Regression Splines. J. R. Stat. Society: Ser. B (Statistical Methodology)65 (1), 95–114. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00374

97

Zieman J. Fourqurean J. Frankovich T. (1999). Seagrass Die-Off in Florida Bay: Long-Term Trends in Abundance and Growth of Turtle Grass, Thalassia testudinum. Estuaries22, 460–470. doi: 10.2307/1353211

Summary

Keywords

seagrass (Zostera), climate change, monitoring, sea surface temperature, Zostera marina

Citation

Plaisted HK, Shields EC, Novak AB, Peck CP, Schenck F, Carr J, Duffy PA, Evans NT, Fox SE, Heck SM, Hudson R, Mattera T, Moore KA, Neikirk B, Parrish DB, Peterson BJ, Short FT and Tinoco AI (2022) Influence of Rising Water Temperature on the Temperate Seagrass Species Eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) in the Northeast USA. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:920699. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.920699

Received

14 April 2022

Accepted

10 June 2022

Published

22 July 2022

Volume

9 - 2022

Edited by

Kasper Elgetti Brodersen, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Reviewed by

Michael Alan Rasheed, James Cook University, Australia; Martin Dahl, Södertörn University, Sweden

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Plaisted, Shields, Novak, Peck, Schenck, Carr, Duffy, Evans, Fox, Heck, Hudson, Mattera, Moore, Neikirk, Parrish, Peterson, Short and Tinoco.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Holly K. Plaisted, holly_plaisted@nps.gov

This article was submitted to Marine Ecosystem Ecology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.