Abstract

Through the advancement of observation systems, our vision has far extended its reach into the world of fishes, and how they interact with fishing gears—breaking through physical boundaries and visually adapting to challenging conditions in marine environments. As marine sciences step into the era of artificial intelligence (AI), deep learning models now provide tools for researchers to process a large amount of imagery data (i.e., image sequence, video) on fish behavior in a more time-efficient and cost-effective manner. The latest AI models to detect fish and categorize species are now reaching human-like accuracy. Nevertheless, robust tools to track fish movements in situ are under development and primarily focused on tropical species. Data to accurately interpret fish interactions with fishing gears is still lacking, especially for temperate fishes. At the same time, this is an essential step for selectivity studies to advance and integrate AI methods in assessing the effectiveness of modified gears. We here conduct a bibliometric analysis to review the recent advances and applications of AI in automated tools for fish tracking, classification, and behavior recognition, highlighting how they may ultimately help improve gear selectivity. We further show how transforming external stimuli that influence fish behavior, such as sensory cues and gears as background, into interpretable features that models learn to distinguish remains challenging. By presenting the recent advances in AI on fish behavior applied to fishing gear improvements (e.g., Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), coupled networks), we discuss the advances, potential and limits of AI to help meet the demands of fishing policies and sustainable goals, as scientists and developers continue to collaborate in building the database needed to train deep learning models.

1 Introduction

In observing fishes, the human eye can efficiently distinguish swimming movements, where the fish is, how it is swimming, how it is interacting with other fishes and its environment (He, 2010). For ethologists, interpreting behaviors from visual observations come almost instantaneously. As developments of non-invasive and autonomous underwater video cameras continue to advance (Graham et al., 2004; Moustahfid et al., 2020), behavioral observations can now be derived from a plethora of high-resolution marine imagery and videos (Logares et al., 2021). The reach of human vision continues to extend as cameras can be used in most conditions (Shafait et al., 2016; Christensen et al., 2018; Jalal et al., 2020), such as light, dark and muddy underwater conditions, and can go to greater depth and longer periods (Torres et al., 2020; Bilodeau et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2022). Cameras can now provide vision in 2D or 3D into how fishes interact with fishing gears used to capture marine species (e.g., pots, lines, trawls and nets) where behavior can be recorded by an observation system. It allowed direct vision on how gear components affect catches and escapements (Graham, 2003; Nian et al., 2013; Rosen et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2016; Langlois et al., 2020; Sokolova et al., 2021; Lomeli et al., 2021) and has opened windows to observe behaviors of fishes in any kind of environmental condition (Robert et al., 2020; Cuende et al., 2022).

This marked an important step to capture finer details in the process of fishing gear selectivity (i.e., the gear’s ability to retain only targeted species, while avoiding bycatch of vulnerable, unwanted species or undersized individuals). Innovations in gear selectivity continue to bring in new types of selection and bycatch reduction devices added to gear designs (e.g., for review of selective and bycatch reductions devices, see Vogel, 2016; Matt et al., 2021; for grid, see Brinkhof et al., 2020, for mesh size: Kim et al., 2008; Aydin and Tosunòlu, 2010; Cuende et al., 2020b; Cuende et al., 2022, for panels: Bullough et al., 2007; Ferro et al., 2007). By observing the influence of these modifications, finer selectivity patterns have been unraveled, highlighting how the visual, hearing and tactile cues that species are sensitive to are key in the capture process of fishes (Arimoto et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2010). As studies in fish vision show differences in behavior across species in relation to their spectral sensitivity (Goldsmith and Fernandez, 1968; Carleton et al., 2020), gears continue to be developed with visual components, such as light and color, that aim to make them more or less detectable (Ellis and Stadler, 2005; Sarriá et al., 2009; Underwood et al., 2021). Mesh and panel configurations affect tactile cues and herding behavior that can differ among species (Ryer et al., 2006). Thus, they are continually being tested across different fishing zones (Ferro et al., 2007; Cuende et al., 2020a) as environmental conditions such as depth and light penetration change fish behavior (Blaxter, 1988). Observations of how visual, acoustic, or mechanosensory stimuli elicit fish movement have been extensively studied (e.g., Forlim and Pinto, 2014; Popper and Hawkins, 2019; Xu et al., 2022). Quantifying reactions of fishes to stimuli or gear modifications requires an assessment of their swimming patterns that are highly variable and nonlinear as they are under stress, in constant locomotion (Kim and Wardle, 2003; Kim and Wardle, 2005) and are affected by several environmental factors (Schwarz, 1985; Baatrup, 2009; Yu et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022). Moreover, their movement often differ between individual and group behavior (Viscido et al., 2004; Stienessen and Parrish, 2013; Harpaz et al., 2017; Schaerf et al., 2017).

As of today, automated tools in fish recognition have been mostly driven by economical frameworks such as in monitoring their welfare on fish farms. (Zhou et al., 2017; Muñoz-Benavent et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2019; Måløy et al., 2019; Bekkozhayeva et al., 2021; X. Yang et al., 2020), in directing migratory trajectories in river passageways (Stuart et al., 2008; Cooke et al., 2020; Eickholt et al., 2020; Jones and Hale, 2020) and stock assessments (Mellody, 2015; Myrum et al., 2019; Connolly et al., 2021; Ovchinnikova et al., 2021). Artificial Intelligence (AI) has thus become a multi-purpose data processing tool in marine science that is integrated in model simulations, predictions of physical and ecological events (Chen et al., 2013) and imagery data processing from large-scale to fine-scale observations (Beyan and Browman, 2020). Yet, observations are often focused on the temporal aspects of swimming behavior on a 2D-scale (Lee et al., 2004; G. Wang et al., 2021) with lack of spatial depth and 3D components of the real world, providing only a narrow window of their actual behavior as a whole. These movements and their complexity need to be transformed into meaningful metrics derived from video observations (Aguzzi et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2020). This requires a tremendous amount of time, focus, effort and is subject to error and incomplete manual observations (Huang et al., 2015; Guidi et al., 2020). This is where AI methods enter (Packard et al., 2021): the principle is to translate what the human eye sees and what the brain interprets into computer vision (or machine vision) and artificial neural networks (van Gerven and Bohte, 2017; Boyun et al., 2019). For computer vision, images of fishes and their corresponding features (temporal and spatial) must therefore be translated to numerical units that the computer can understand (Aguzzi et al., 2015).

Studies and innovations on fish observations over the past decade have successfully generated models that can automatically see fishes on videos, identify taxa and follow their swimming direction with considerable accuracy (Hsiao et al., 2014; Nasreddine and Benzinou, 2015; Ravanbakhsh et al., 2015; Boudhane and Nsiri, 2016; Qin et al., 2016; Marini et al., 2018; Xu and Matzner, 2018; Salman et al., 2019; Cai et al., 2020; Cui et al., 2020; Jalal et al., 2020; Raza and Hong, 2020; Yuan et al., 2020; Ben Tamou et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2021; Crescitelli et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Lopez-Marcano et al., 2021; Knausgård et al., 2021). Despite recent advancements, it remains challenging to train existing AI models (e.g., Convolutional Neural Network, CNN; Faster Recurrent CNN, Faster RCNN; Residual Network, ResNet; Long Short-Term Memory, LSTM; Convolutional 3-dimensional network, C3D, etc.) that could recognize fish behaviors from their swimming movements in 3D (Li et al., 2022) given the myriad of variability occurring at sea (Christensen et al., 2018). Artificial Intelligence may help to further improve the sustainability of fishing as the classical selective studies are reaching a plateau due to bottleneck in data collection inherent to the challenge of obtaining direct, in situ observations.

This paper addresses common stimuli that trigger fish reactions from selective devices in fishing gears and how these behavioral responses are transformable into quantifiable metrics with selectivity modeling and classification methods that can be pipelined in AI methods (Section 2). Section 3 presents current state and limitations of AI applied to fish gear interactions through a bibliometric analysis and the recent developments in automatic behavior recognition. The fourth section addresses the hurdles of observing interactions of fishes across fishing gear selectivity studies and how AI methods may help face these challenges.

2 Observing stimuli-response in fishing gears: The teaching base of AI models for behavior recognition

“Researchers now realised that, like the rest of the vertebrate kingdom, fishes exhibit a rich array of sophisticated behaviour and that learning plays a pivotal role in behavioural development of fishes. Gone, or at least redundant, are the days where fishes were looked down upon as pea-brained machines whose only behavioural flexibility was severely curtailed by their infamous 3-second memory” (Brown et al., 2006)

2.1 Observations of fish behavior in fishing gears

Early testing, through manual counting, size measurement, and quantification of catches/retention, has paved the way for selective devices and gear modifications to be integrated in the design of commercial fishing gear. Mesh modifications were suggested through empirical approaches by studying catch retention (e.g., catch comparison or covered codend methods) (Dealteris and Reifsteck, 1993; Ordines et al., 2006; Aydin and Tosunòlu, 2010b; Anders et al., 2017b), tank experiments for manual observations of fish passing through meshes (Glass et al., 1993; Glass et al., 1995) and even numerical approaches which estimates catches a posteriori (e.g., SELECT; Fonseca et al., 2005). Optic and sonar imaging rapidly came into play to directly estimate catches during capture (Silicon Intensified Target, SIT camera system, Krag et al., 2009; acoustic imaging, Ferro et al., 2007), then applied to observe species behavior in gears (Mortensen et al., 2017). Over the years, observing fishes became achievable in various conditions with the breadth of available technology that can be autonomously deployed for ecological and fisheries monitoring (Durden et al., 2016; Moustahfid et al., 2020). Example of technological solution to observe behavior in real world condition are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Condition of observation | Technological Solutions | Limitation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Turbidity | High spatial acuity cameras, laser-imaging, Cameras with polarized filters or light sources | High cost | (Lu et al., 2017) |

| Backscatter of natural light | |||

| Dark environment | Far-red illumination (680 nm LED), near-infrared illumination | Less features in images; narrow range of view | (Chidami et al., 2007; Shcherbakov et al., 2012) |

| Species-level recognition | High-definition cameras | High cost, limited to RGB cameras | (Crescitelli et al., 2021; Murugaiyan et al., 2021) |

| Abrupt changes in animal orientation, fast-swimming species | High shutter speed (> 200 frames per second) | High cost | (Catania et al., 2008) |

| Continuous recordings of species distribution | Long-battery/low-energy/cabled cameras | Limited spatial range | (Rosen and Holst, 2013; DeCelles et al., 2017) |

| Collective behavior, capturing large elements or objects | Stage-wide cameras/multiple set-up cameras, far-range sonars, hydroacoustic | High cost; logistically demanding | (Wei et al., 2022) |

| Capture depth/3D features | 3D/holographic/stereo cameras, cameras with distance-compensated structured lighting, Optical-Acoustic Hybrid Imaging | Heavy computational cost; logistically demanding | (Sawada et al., 2004; Negahdaripour, 2005; Pautsina et al., 2015) |

| Small compartments/space | Compact/micro cameras | Low image resolution | (Duecker et al., 2020) |

Example of technological solution to observe behavior in varying conditions.

Interesting behaviors from fishes have since been unearthed such as anti-predatory responses (Rieucau et al., 2014), encounters of fish with nets (Jones et al., 2008; Rudstam et al., 2011), differences in swimming speed (He, 1993; Breen et al., 2004; Spangler and Collins, 2011), avoidance (de Robertis and Handegard, 2013), exhaustion (Krag et al., 2009), orientation (Odling-Smee and Braithwaite, 2003; Holbrook and Perera, 2009; Haro et al., 2020), escapement (Glass et al., 1993; Mandralis et al., 2021), herding behavior (Ryer et al., 2006), and unique social behaviors (Anders et al., 2017a) from which selectivity studies in gears are based on. Knowledge of fish reaction and escape behavior has thus grown, leading to the development of novel gears with more open meshes, careful placement of sorting grids, and other devices to improve both size and species selectivity (Stewart, 2001; Watson and Kerstetter, 2006; Vogel, 2016; O’Neill et al., 2019). Gear selectivity might also be improved by triggering active species responses, using light, sound, and physical stimuli (O’Neill and Mutch, 2017).

2.2 Current observations of fish stimuli-response

2.2.1 Responses to light and color stimuli

Fish responses to light has been mainly studied in controlled environments and in aquaculture. It is challenging to observe light responses at sea as light attenuation limits the direct observations of fish behavior. The response to light—i.e., phototaxis—can improve gear selectivity as fishes greatly depend on vision for sensory information (Guthrie, 1986). Depending on the species and the development stage (Kunz, 2006), fishes can exhibit either positive (swimming towards light source) or negative phototaxis (swimming away) to different wavelength and intensities of light (Raymond and Widder, 2007; Underwood et al., 2021). Thus, artificial illumination is taking considerable attention for behavioral guidance of fishes to dissuade fishes from entering the gear (Larsen et al., 2017), or to help them escape from within (Southworth et al., 2020). Illumination in gears take either the form of LED light installments (e.g., illuminated escape rings for non-targeted species, Watson, 2013; illuminated separation grids for ground fishes, O’Neill et al., 2018b) or with glow-in-the-dark netting material (Karlsen et al., 2021). In dark environments, near-infrared light or red light is usually used to observe the behaviors of fishes instead of white light that may disrupt behaviors of fishes (Widder et al., 2005; Raymond and Widder, 2007; Underwood et al., 2021).

Responses of fish to color also play an important part as most bony fishes are tetrachromatic, allowing them to see colors more vividly than humans (Bowmaker and Kunz, 1987). Some fishes may be more visually sensitive to certain kinds of light wavelength and intensity (Lomeli and Wakefield, 2019), other may be non-responsive (Underwood et al., 2021). Researchers thus use these species-selective traits to install light devices (LED lights, infrared light, laser beams) on gears or change the color of the fishing nets (white, transparent, black) depending on the selected species (Simon et al., 2020; Méhault et al., 2022)

2.2.2 Responses to acoustic stimuli

Sound has been long used by fishers to scare fishes and gather them for bottom trawling. Yet, the response to sound—i.e., phonotaxis—can also be used for selectivity as hearing species are generally sensitive to specific frequencies (Dijkgraaf, 1960). Selectivity studies typically observe negative phonotaxis (i.e., avoidance) triggered by low-frequency sound (Schwarz and Greer, 2011), which can be displayed by fishes in different ways (Popper and Carlson, 1998; de Robertis and Handegard, 2013). Similar to light responses, some fishes tend to be more sensitive to certain sound frequencies, some are called “hearing specialists” such as Atlantic herring and cod (Chapman and Hawkins, 1973; Doksæter et al., 2012; Pieniazek et al., 2020). O’Neill et al. (2019) also suggested that passive acoustic approaches with sound reflectors can be designed with gears to make them more detectable for echo-locating species (He, 2010). Mainly, sound and light added to fishing gears can help attract the targeted species and help deter vulnerable or harmful animals such as mammals or fish predators (Putland and Mensinger, 2019; Lucas and Berggren, 2022). Although fishing techniques with sound have been in practice since a while (He, 2010), exploration for species selective sound devices are still at its early stages.

2.2.3 Responses to physical stimuli

The response to physical contact—i.e., thigmotaxis—shows the tendency of fishes to remain close to the seabed, or the lateral structure of gears (Millot et al., 2009). This behavior can be utilized to modify mechanical structures and panels in gears. Physical stimuli can play an important role for allowing fishes to escape (Mandralis et al., 2021) or be sorted (Larsen and Larsen, 1993; Brinkhof et al., 2020). These are usually installed in or on the gears after a series of behavioral trials on fish responses to different configurations (Santos et al., 2016). Physical stimuli are thus often drawn from the species-specific behavior (Ferro et al., 2007; Cuende et al., 2020a).

Fishes tend to orient themselves to face the water flow to hold a stationary position and lower the amount of energy they spend; this is called rheotaxis (Painter, 2021). The directional behavior due to water flow may be used to improve selectivity in trawls. For example, veil nets on shrimp fishery can modify the flow within gears, directing fishes to selective grids and net structures (Graham, 2003) and water jets projecting downward of forward can elicit early avoidance from fishes about to enter the gear (Jordan et al., 2013).

2.2.4 Other stimuli and combination of stimuli

Other stimuli relating to chemical responses (chemotaxis; Løkkeborg, 1990) and electrosensory responses (i.e., electrotaxis; Sharber et al., 1994; O’Connell et al., 2014) in fishes still need to undergo trials. Chemotaxis, which fishes use for foraging, may help fishes acquire information from greater distances (Weissburg, 2016) and are used in baited fisheries (Rose et al., 2005). Electrotaxis that elasmobranchs use to detect weak electromagnetic signals is exploited in longline fishing to reduce bycatch with electropositive metals and magnets (Kaimmer and Stoner, 2008; Robbins et al., 2011; O’Connell et al., 2014). Combination of multiple stimuli such as acoustic and visual signals also promote different responses from fishes, enhancing or impeding the responses to other cues (Lukas et al., 2021). Overall, understanding multi-sensory modalities of marine animals may help adjust selective devices, reducing bycatch and focusing catches to targeted species (Walsh et al., 2004; Jordan et al., 2013).

2.3 AI application to fish stimuli

Studying fish responses to stimuli require empirical studies, which are often limited in terms of replicates due to logistical constraints and temporal demand to collect and process raw data. Stimuli have thus been studied manually, since automatization remains difficult to apply to in situ conditions due to heterogeneous, moving background and environmental conditions. Manual observations of stimuli response currently provide the reference point for behavior recognition which now faces more and more data to process from continued observations at sea. Applying AI models may ease the data processing and enable to exploit larger amount of data. As opposed to traditional tracking method applicable to controlled experiments (e.g., background subtraction and Kalman filters, Simon et al., 2020), deep learning models are less sensitive and may be applied to harsher conditions (Sokolova et al., 2021). Computer vision can also be improved by selecting the observation system the most appropriate to produce imagery data for the fishing gear used; the variety of systems and data processing approaches for stimuli is presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Stimuli | Behavioral studies | Data Processing | Fishery Potential Application | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxi (Response) | Short-term Behavior | Current Observation Systems (Computer vision) | Behavioral Data Processing | AI application | Advantage/Limitation of Computer Vision | Fishing gears | Selective Device/Method | |

| Chemical | Chemotaxis | Attraction, repulsion, feeding, herding | Baited Remote Underwater Videos (BRUV), Optical (RGB) or Infrared) and Hydroacoustic camera | Automated | Cascade Faster R-CNN (Méhault et al., 2022), C3D Model (G. Wang et al., 2021), Dual Stream Recurrent Network (Måløy et al., 2019) | Zero to low visibility of chemical diffusion in water that can be seen by computer vision | Baited gears (fish pots, hook-and-line, longline, gillnets, trawling) | Natural or artificial baits |

| Light | Phototaxis | Attraction, repulsion, herding | Optical cameras, Hydroacoustic camera | Automated | C3D Model (G. Wang et al., 2021), YOLOv2 + behavioral metric pipeline (Barreiros et al., 2021) | Light attenuation in water | Any type of gears (Pots, longline, Gillnet, Surrounding nets, Lift nets, Seine, Trawl, Dredge) | LED lights, laser beams |

| Sound | Phonotaxis | Attraction or repulsion | Optical cameras (RGB or Infrared), Hydroacoustic camera | Automated | C3D Model (G. Wanget al., 2021), YOLOv2 + behavioral metric pipeline (Barreiros et al., 2021) | Sound diffusion can only be detected with acoustic cameras, stimuli origin not visible to optical cameras | Gillnet, Purse Seine | Acoustic beams (Gan et al., 2012), pingers/sonar reflectors, fish calling devices (donburi, payao) (Yan et al., 2010) |

| Water current | Rheotaxis | Change in orientation, herding, or speed | Optical cameras (RGB or Infrared), Hydroacoustic camera | Manual | Particle image velocimetry (PIV) (Oteiza et al., 2017) | Requires additional measurement for speed of current | Any type of gears (Pots, longline, Gillnet, Surrounding nets, Lift nets, Seine, Trawl, Dredge) | Bait diffusion from source, Water jets, gear panels |

| Physical barriers/touch | Thigmotaxis | Herding, sheltering behavior | Optical cameras (RGB or Infrared), Hydroacoustic camera | Automated | Motion influence map + RNN (Zhao et al., 2018) | Requires wide angles of video recording and image capture | Any type of gears (Pots, longline, Gillnet, Surrounding nets, Lift nets, Seine, Trawl, Dredge) | Panels, mesh size and shape, netting grids |

Examples of fish behavior studies exploring species’ responses to stimuli using AI and their application on fisheries.

For comprehensive summary of fishing gears, see (He et al., 2021).

3 Artificial Intelligence for fish behavior applications

3.1 Bibliometric analysis

3.1.1 Bibliometric analysis methods

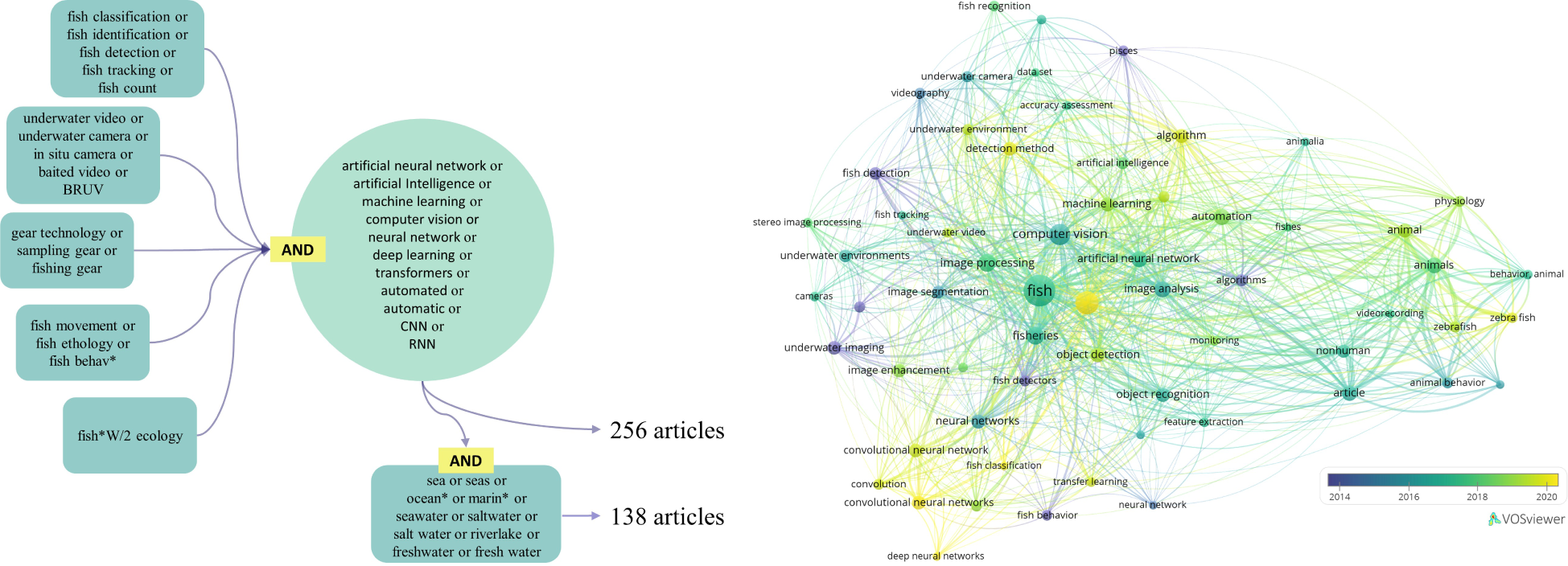

A bibliographic research was done in February 2022 on SCOPUS for scientific journals on 2 sets of 5 queries (Figure 1). Each of the query of the first set (256 articles) included AI-related keywords. The queries linked to the AI keywords were selected to obtain studies that focus on fish behavior, underwater observations, fishing gears, and in ecological studies. The second set had the same keywords as the first set but included keywords for both saltwater and freshwater ecosystems to exclude automatic detection and classification of fish species done onboard fishing vessels with the use of keywords in all the 5 queries. This narrowed down the number of extracted publications to 138 articles (Figure 1). However, both sets of publications still included studies not relevant to the topic, so a manual screening was undertaken. The screening was done one by one among the extracted studies to keep only the relevant studies which were cross analyzed with other pertinent studies that have not been included in the SCOPUS results but are mentioned in this review. The studies that were removed from the list focused on topology mapping, stock assessment, climatological studies, biochemical studies, and automatic identification for other marine fauna and flora such as sea cucumber and algae. A final list of 384 relevant studies was collected and reviewed to extract the studies with automated fish detection, counting, species classification, motion tracking and behavior recognition with deep learning models in underwater systems.

Figure 1

Visualization of bibliographic search. Top photo: Set of queries in SCOPUS and number of resulting articles. Fish*W/2 ecology keyword was used to focus the search on ecologically-based studies. Bottom photo: Bibliometric landscape of topics from articles (Linkage of keywords, occurrence > 5).

3.1.2 Bibliometric analysis results

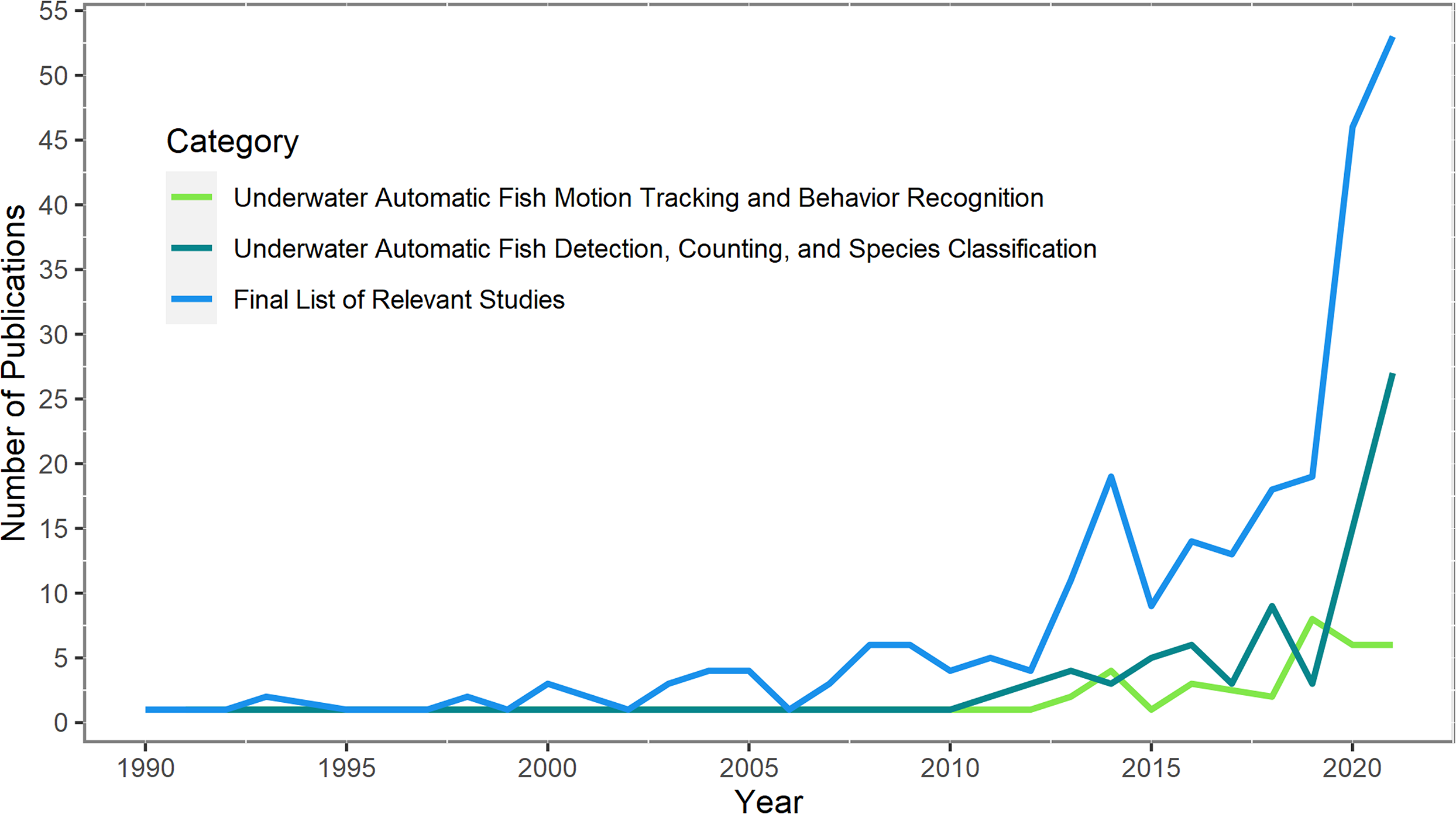

The gathered studies show that the automation of tasks such as fish detection, species classification, fish counting, fish tracking, and behavior recognition is progressively materializing in the 21st century (Figure 2). The onset of ecological studies of fishes based on AI and computer vision has surfaced in the past 10 years (87 publications in relation to fish detection and classification; 36 in relation to fish behavior recognition extracted from bibliography search in SCOPUS). Developments are still on their early stages but are gaining attention rapidly, particularly for automatic detection and classification techniques thanks to the rise of deep learning (LeCun et al., 2015). Studies are fewer for automatic motion tracking of fishes and behavior recognition compared to detection and classification studies as they build on the AI methods of the latter and require more complex processing. While fish detection is being widely applied in marine habitats for several years (Fisher et al., 2016), automatic tracking and behavior recognition of fishes during capture process has yet to be applied. The following sections expand the results from the bibliometric analysis and give a brief explanation of AI and examples on the current applications of behavior recognition that can be transferred to selectivity studies.

Figure 2

Number of publications between 1989 and 2022 for the 3 categories. The number of publications in all categories is from the cross-analysis between bibliographic search in SCOPUS and manual search in both Google Scholar and Web of Science. The final list includes 388 relevant articles reviewed one by one and categorized by the authors according to the methods included in each study.

3.2 Introduction to Artificial Intelligence

As current observations of fish behaviors in fishing gears now step into the era of AI and deep learning along with other domains in marine science (Malde et al., 2020; Logares et al., 2021; Packard et al., 2021), Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT) and Big Data coupled to AI will inevitably revolutionize the field (Jahanbakht et al., 2021). Today, behavioral studies in fisheries science stand on top of highly evolving tools to automatize analysis and processing of data. They are curated from interdisciplinary fields among marine science, computer science, neuroscience, and mechanical science among many other disciplines that are now coagulating because of AI (Xu et al., 2021). Some useful references for AI in marine science and reviews can be found in Beyan and Browman (2020); Malde et al. (2020) and Goodwin et al. (2021).

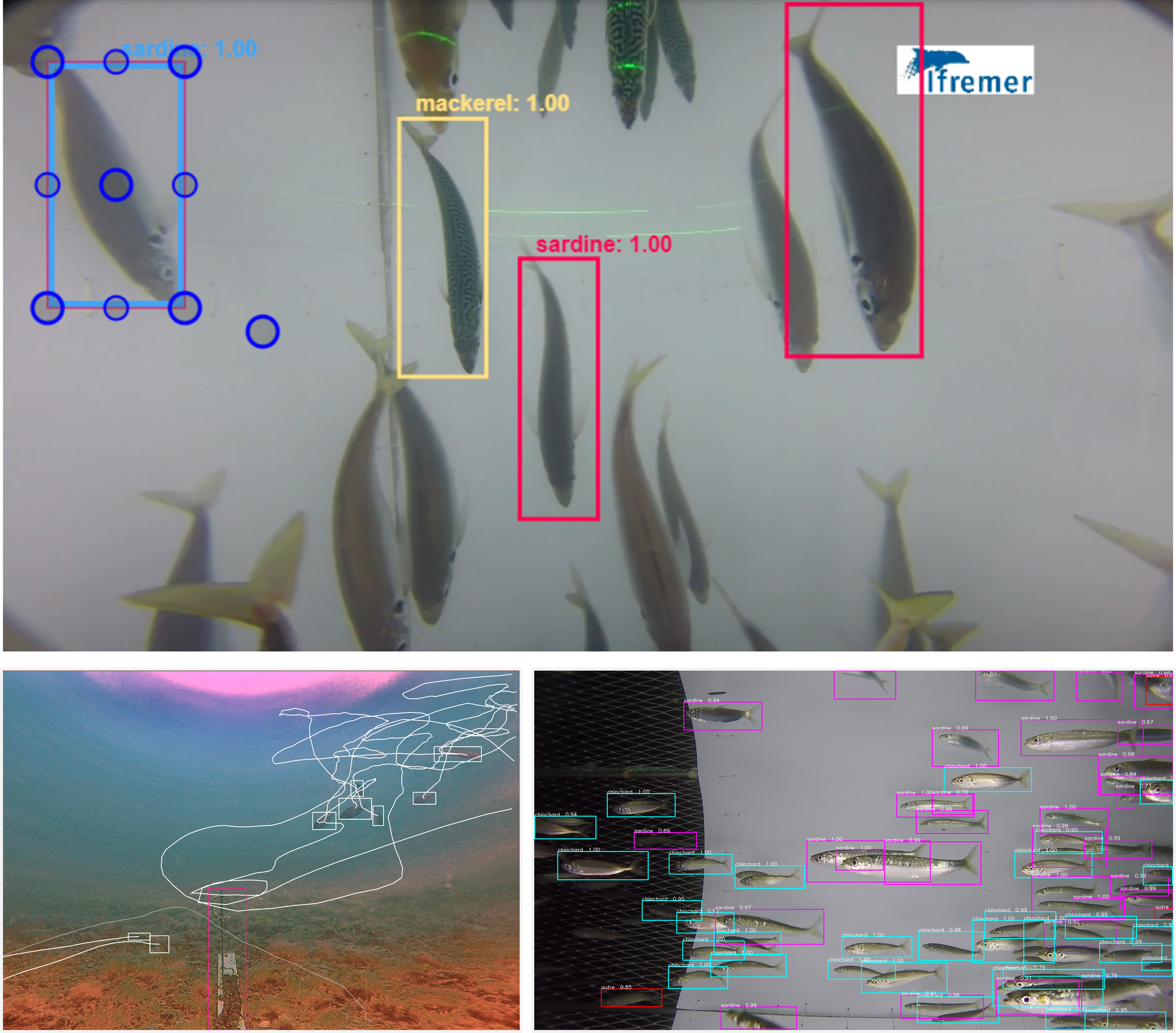

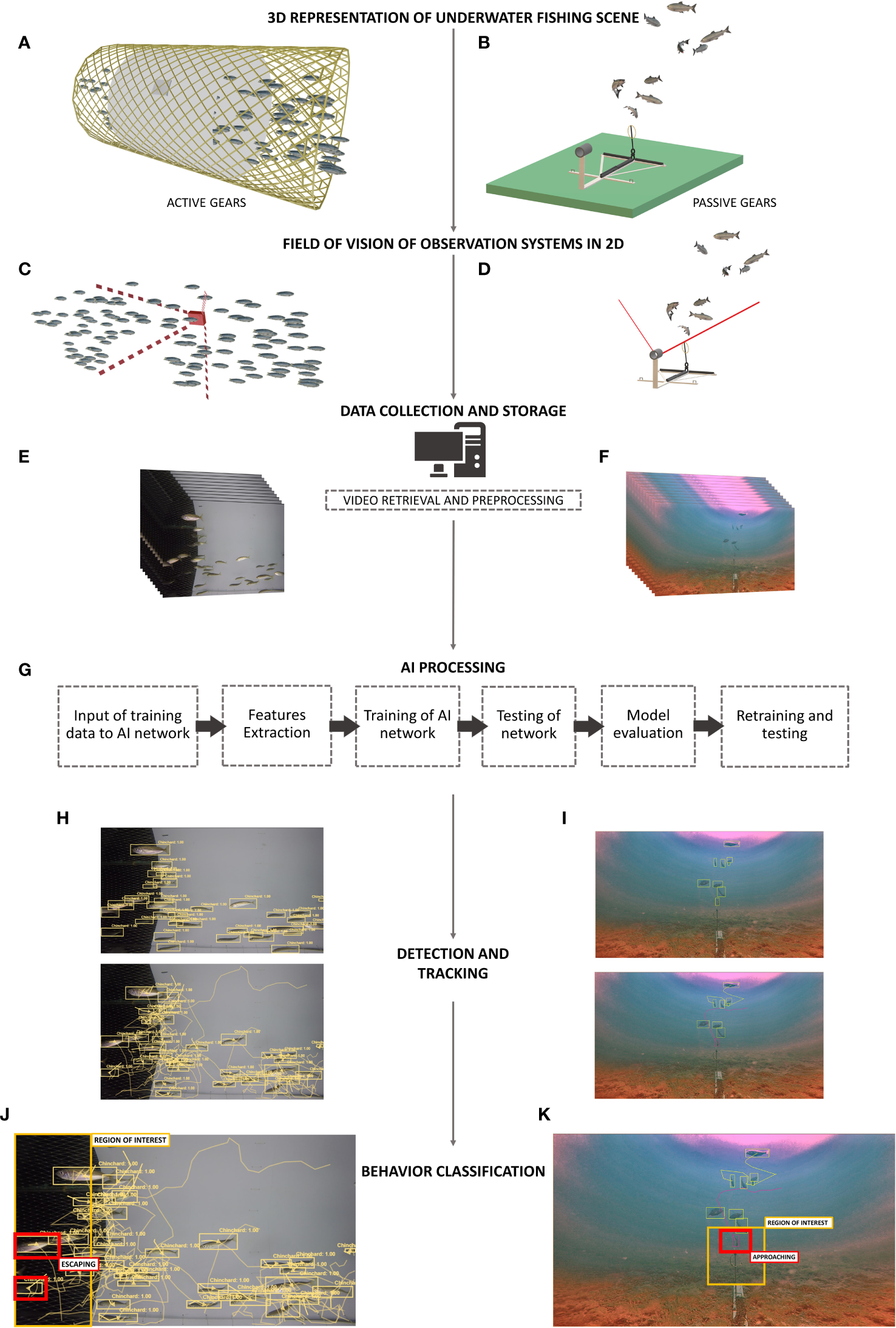

In marine sciences, neural networks used for object detection are usually “supervised” (Cunningham et al., 2008), meaning that they are trained using ground-truth objects, manually located in images, and classified into pre-defined classes. These objects, defined using the four coordinates of their bounding boxes and their associated classes (see Figure 3 for examples of bounding boxes), are then used to train the model to localize and classify these target objects within new images. Indeed, objects are assigned to one or several categories based on the probability of belonging to each of the classes used to train the model (Pang et al., 2017; Ciaparrone et al., 2020). Once object detection is done on different frames (Figure 4E, F), the tracking model pairs the bounding boxes among frames to reconstruct the track of each object through time and space (Belmouhcine et al., 2021; Park et al., 2021). During the training, if the model can predict classes and bounding boxes that match the groundtruth validation data with a minor error, depending on the given parameters, it can be considered an accurate model. However, if the model has poor predictive performances, then the learning continues.

Figure 3

Examples of bounding boxes of fishes. Top panel: Tracking of fishes on the open-source VIAME platform for image and video analysis (Dawkins et al., 2017). Bottom left: multiple trajectories of black seabreams around a fixed bait. Bottom right: In situ detections of sardines and horse mackerel inside a gear (Game of Trawls Project).

Broadly speaking, images are streamlined into computer algorithms to extract information. These algorithms contain artificial neural networks that apply a sequence of mathematical operations (convolution, pooling, etc.) to perform object detection. Those operations are linked together to orchestrate a pipeline, so that image processing is not interrupted (Figure 4G). The operations can detect objects because they determine patterns in pixels (i.e., binary trait of computers; Shaw, 2004; Pietikäinen et al., 2011) from the input images that define features (Blum and Langley, 1997). Features are measurable variables that can be interpreted from images, such as shapes and textures of objects (Chandrashekar and Sahin, 2014). Algorithms trained to detect patterns from features automatically are called detection models. Before training the model, images are preprocessed to be enhanced (i.e., neutralize discriminations and scale dimensions) so that models can learn better (Nawi et al., 2013; Calmon et al., 2017), since data are generally noisy when captured in the real-world conditions. Recent artificial neural networks contain attention modules (Vaswani et al., 2017; Gupta et al., 2021) to capture long-range dependencies and understand what is going on in an image globally (Grauman and Leibe, 2011).

Figure 4

General process from in situ observations to behavior classification. (A), Representation of a section of an active gear (i.e., pelagic net) with a white-colored material that act as a clear background for video capture. (B), Representation of a passive gear (i.e., baited gear)-baitfish prototype fixed on the seafloor with a remote underwater video set-up. (C), Field of vision of a camera secured attached on one side of the pelagic net section. (D), Field of vision of a camera facing the bait. (E, F), Frames from video footage of the underwater observation systems. (G), General workflow for deep learning model application on object detection. (H, I), Sample of fish detections with bounding boxes and fish tracking with bounding boxes and line trails (Game of Trawls and Baitfish)., (J) Representation of behavior classification labels inside active gear. The “region of interest” labels the section of the gear near the exit and “escaping” labels the fishes that are exiting. (K), Representation of behavior classification labels with passive gear. The “region of interest” labels the area in proximity of the bait and “approaching” labels the fish within this proximity. 3D model of baited gear credit to BAITFISH project and image of fishes inside the pelagic net credit to Game of Trawls project.

Current deep learning methods are mostly “black boxes” since humans cannot see how individual neurons work together to compute the final output (e.g., why a fish in an image has been detected or not), so improving the accuracy of models relies on better inputs and comparison of trainings (LeCun et al., 2015). However, unsupervised learning is gaining more interest as it allows the transition from recognition to cognition (Forbus and Hinrichs, 2006; Xu et al., 2021). This means that innovations in the AI domain are now making interpretable models that can figure out why and how they localize and classify objects on a scene (Ribeiro et al., 2016; Hoffman et al., 2018; Gilpin et al., 2019). Among unsupervised learning models, Generative Adversarial Neural Networks (GAN) are composed of two networks: a generator that generates synthetic data and a discriminator that classify the data as real or fake. The generator learns how to fool the discriminator by learning the real data distribution and generating synthetic data that follow this distribution. The discriminator should not be able to distinguish real from synthetic data. Thus, object detection models can now be coupled to a GAN and learn by themselves, in a semi-supervised manner, by artificially generating new sets of images (from the generator model) that feed through another model: the object detector (e.g., generator model produces synthetic images of fishes for another model to detect them; Creswell et al., 2018). Applying these AI methods to fish interactions with fishing gears would enable us to decipher which behaviors lead to the catch and escapement of fish at more significant scales than what could be reached until today. For a comprehensive review on available deep learning-based architectures, see Aziz et al. (2020).

3.3 AI for fish behavior

Tools for automatic behavior recognition are being developed mainly in aquaculture (Valletta et al., 2017; Niu et al., 2018) and in coastal fish communities (e.g., Kim, 2003; Fisher et al., 2016; Capoccioni et al., 2019; Lopez-Marcano et al., 2021; Ditria et al., 2021a). Over the last decade, there has been an emergence of automatic fish detection, species classification, combined with tracking innovations, and this has contributed to a robust foundation for behavioral recognition. Behavioral studies of fishes in aquaculture looked at feeding behavior to monitor appetite and abnormal behaviors in intensive farming conditions (Kadri et al., 1991; Zhou et al., 2017; Niu et al., 2018; Måløy et al., 2019; Pylatiuk et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020). Behaviors that were automatically detected include: feeding movements at individual and school level, feeding intensity (Zhou et al., 2019), abnormal behaviors due to lack of oxygen or stress response (J. Wang et al., 2020), and curiosity by showing inspection behaviors when interacting with bait or objects in experimental set-up (Papadakis et al., 2012).

In laboratory experiments, goal-directed behaviors of fishes have also been recognized by computer vision and are automatically detected (Long et al., 2020) such as construction of spawning nests by cichlid fishes that either form mounds or burrow in the sand. This type of complex behavior can be distilled into recognizable patterns such as manipulation of their physical environment (cichlid fish use its mouth and fins to move sand) and distinct fish movements such as quivering (usual mating movement observed from cichlid fishes). Automatically recognizing these behavior patterns contributes to systematic analysis of these traits across taxa (York et al., 2015) and can be an effective metric for measuring natural variations (Long et al., 2020).

Artificial Intelligence methods trained to recognize fish behavior have multiple components that are all connected in branching streams of mathematical and statistical operations. From a video of swimming schools of fishes, the attributes of what is happening in the scene would be broken down into features of the fishes, their appearance in terms of shape, texture, or color, and their reaction to different types of stimuli translated into quantifiable metrics. Some additional examples of applications can be found in Spampinato et al. (2010); Fouad et al. (2014); Hernández-Serna and Jiménez-Segura (2014); Iqbal et al. (2021) and Lopez-Marcano et al. (2021).

3.3.1 AI-based automatic behavior recognition for fishes

Fish detection by AI models is when individuals or species are recognized on a single image (Sung et al., 2017). An algorithm is trained to identify features of fishes and localize regions in a scene. The YOLO (You Only Look Once; Redmon et al., 2016) object detection framework has been frequently used for fish detection and species classification on 2D images (Cai et al., 2020; Jalal et al., 2020; McIntosh et al., 2020; Raza and Hong, 2020; Bonofiglio et al., 2022; Knausgård et al., 2021). The YOLO algorithm and its different versions are widely used since its detecting speed on an entire image are faster and more accurate than classic object detectors (for technical specifications, see: Redmon et al., 2016). A trained detection model can thus differentiate targeted and non-targeted species, and identify differences between their morphology (i.e., round vs flat fish). Moreover, a cluster of individual detections can also illustrate herding behavior from crowd movements.

Identifying different swimming patterns between targeted and non-targeted species, however, requires tracking the spatial alignments of trajectories inside gears and directions of swimming through time, i.e., tracking. Fish tracking is done using motion algorithms based on successions of images with multiple or individual fish until they are no longer seen on the footage (Li et al., 2021). To track fishes, algorithms are thus trained as a single network or are coupled into a pipeline of networks for more complex behavior interpretations (Table 3). Different implementations of deep learning-based tracking have been used across studies, depending on their tracking objectives or available resources (for object detection: Faster R-CNN, for instance segmentation: Mask R-CNN, for tracking based on loss: Minimum Output Sum of Squared Error (MOSSE), for tracking based on comparing similarity among masks (similarity learning): Siamese Mask (SiamMask), and for tracking based on Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) applied to sequences: Seq-NMS). Their differences lie on the way they compute detections from frame to frame and associate them to new or existing tracks of detected fishes (Lopez-Marcano et al., 2021). Coupled networks in AI pipelines are thus used for tracking to interpret finer details in behavior (Table 3).

Table 3

| AI & Pipelines | Application | Results | Behavior classes | Scene | Light source | Underwater Observation System | Database Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv3 + dense optical flow method + trajectory image compression with VGG19 + data augmentation generative sampling + binary behavior classification | Response of zebrafish (Danio rerio) to odorants | Best accuracy achieved among tested classifiers of 0.867 with data augmentation and decision tree classifier | Olfactory response | Lab | Low-light intensity | Infrared video camera | Own dataset + PASCAL VOC and MS-COCO | Banerjee et al., 2021 |

| Pre-trained ResNet50 + Motion estimation algorithm for optical flow data | Grazing behavior of free-swimming luderick (Girella tricuspidata) on sea grass patches | Recall, precision and F1 score between 0.73 and 0.79 (without spatiotemporal filtering); Recall, precision, F1 score between 0.84 and 0.87 (with spatiotemporal filtering) | Grazing/non grazing | In situ open water | Natural light | Action cameras (Haldex Sports Action Cam HD 1080p) | Own dataset (RGB videos) | Ditria et al., 2021b |

| YOLOv3 + MobileNetv2 backbone + improved detection method with pyramid pooling block and multiscale feature extraction technique | Quantify feeding and stress behavior of carps (Carassius auratus) and catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) | Precision of 0.897, a recall of 0.884, an intersection over union of 0.892 | Separate feeding and hypoxia experimental conditions | Fish tank | 120 light-emitting diodes | Go-pro Hero 7 Black | Own dataset (RGB videos) | Hu et al., 2021 |

| Idtracker.ai hybrid system (Gaussian mixture model + greedy acceleration minimization principle) | Characterized mutual motor coordination and multi-functional maneuvers in zebrafish (Dania rerio) | Identification accuracy of 0.98 | Fighting behavior | Lab | light intensity of 200–300 lx at the water surface | Video camera – not specified | Own dataset | Laan et al., 2018 |

| 3D Residual Networks | Behavior of cichlids (foraging, construction, and social behavior) | Accuracy for behavior recognition of construction behavior of 0.76 | Construction, feeding, mating | Lab | Artificial light source | RaspberryPi camera v2 | Own dataset (RGB videos) | Long et al., 2020 |

| Mask RCNN + 3 different trackers (MOSSE, Seq-NMS, SiamMask) | Characterizing movement behavior of yellowfin seabreams (Acanthopagrus australis) | Detection F1 score of 0.91, 120 of 169 individuals correctly identified, 0.78 tracking accuracy (MOSSE and SiamMask) and 0.84 (Seq-NMS) | Tracking angles: | In situ rocky (rocky reefs and seagrass meadows) | Natural light | Action cameras (1080p Haldex Sports Action Cam HD) | Own dataset (RGB videos) | Lopez-Marcano et al., 2021 |

| Dual-Stream Recurrent Network (DSRN) (Spatial Network + 3D CNN + LSTM) | Tracking if feeding behavior of salmon (Salmo salar) | Behavior prediction of 0.80 | Feeding/Non feeding | Breeding cages at sea | Natural light | Video camera (not specified) | Own dataset (RGB videos) | Måløy et al., 2019 |

| YOLOv3 + LSTM networks | Identifying startle behavior in sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbria) | Average precision of 0.85 | Startle/non-startle event on video clips | In situ, open water, tropical | Natural light | Fixed in situ camera | Own dataset (RGB videos) | McIntosh et al., 2020 |

| Built-in algorithms in LabView software + Vision Development Module | Detection of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) changes in speed and position | Less than 21 frames, equivalent to 2.3 s, were lost from a total number of 778,378 recorded frames per day | Net inspection and net biting | Lab | Artificial light | Charge coupled device (CDD) cameras | Own dataset | Papadakis et al., 2012 |

| 2 converging streams of event classifier with SVM + trajectory-based algorithms | Influence of typhoons on mixed coral reef fish behavior in tropical underwater scenes | Accuracy of 0.80 for fish detection, 0.95 for tracking, 0.97 for event detection | Typhoon/non typhoon videos | In situ | Natural light | GoPro cameras | Fish4Knowledge dataset | Spampinato et al., 2014 |

| Dual-stream 3D convolutional network with State Definition + Tracking Encoding + Decoding by Directed Cycle Graph (DSC3D) | Behavior of spotted knifejaw (Oplegnathus punctatus) in high stress environments | Mean correct behavior recognition of 0.950 | 5 behavioral states: Feeding, Hypoxia, Hypothermia, Frightening, Normal | Lab | Artificial light source | HD digital camera (HikvisionDS-2CD2T87E(D)WD-L) | Own dataset (RGB and optical flow videos) | G. Wang et al., 2021 |

| Motion influence map + RNN | Detection, localization, recognition of unusual local behavior in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Accuracy for detection (0.98), location (0.92), recognition (0.90) | Unusual (3 behavioral subcategories of sudden movements) | Aquaculture tank | Artificial light | Charge coupled device (CDD) cameras (DS-2CD6233F-SDI, Hikvisio) | Own dataset (RGB images) | Zhao et al., 2018 |

| Clustering index with near-infrared images | Analyze of feeding behavior of carps (Cyprinus carpio var. specularis) | Accuracy of 0.945 | Temporal feeding states before, during and after (t=5, 15,30,60 s) | Aquaculture | Near-infrared light source | Industrial camera (Mako G-223B NIR) | Own dataset (infrared images) | Zhou et al., 2017 |

| LeNet5 7 layered CNN structure | Assessing fish appetite of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Accuracy of 0.90 | Fish appetite (none, strong, medium, weak) | Aquaculture | Near-infrared light | Industrial camera (Mako G-223B NIR) | Own dataset (infrared images) | Zhou et al., 2019 |

Summary of AI pipelines for fish behavior recognition in different underwater environments.

Full terms of included abbreviations, LSTM, Long Short-Term Memory; CNN, Convolutional Neural Network; MOSSE, Minimum Output Sum of Squared Error; RNN/RCNN, Recurrent Neural Network/Recurrent Convolutional Neural Network; Seq-NMS, Sequential Non-Maximum Suppression; SiamMask, Siamese Mask; SVM, Support Vector Machine; YOLO/v3, You Only Look Once version 3.

To decipher underlying behavioral patterns of fishes from manual or automatically generated fish tracks, repeated patterns can be translated into sets of labelled classes (i.e., n number of trajectory moving in an x, y direction = escaping to upper panel), representing one or several specific behaviors. In AI, classes that can be labelled and quantified (i.e., fish passing a mesh) can be learned by a deep learning model so manual behavior classification can then be automated. In aquaculture, swimming behavior have been manually classified and fed through an algorithm that learns how to recognize the behavioral classes from computer vision (Long et al., 2020; J. Wang et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2021) . In commercial fishing, the challenge lies in deciphering these patterns as fishes interact with different structure of gears, modified parts, and selective devices. To have AI models classify these types of interactions, a systematic approach may thus be needed first in controlled environment, such as fish tanks or behavioral chambers. This would allow stimuli to be restricted and localized (Skinner, 2010) rather than being enhanced or inhibited by spatiotemporal conditions (Ryer and Olla, 2000; Owen et al., 2010; Maia and Volpato, 2013; Heydarnejad et al., 2017; Lomeli et al., 2021).

Recurrent AI models based on LSTM architecture targeting fish tracking are getting more attention since they are designed to give more weight to significant movement patterns among chaotic ones as they are trained. This adds a more cognitive ability to the learning of AI models. For instance, Gupta et al. (2021) investigated different vision-based object-tracking algorithms for multiple fishes in underwater scenes both in controlled and uncontrolled environments. They combined an object tracker designed with two complex networks (a siamese network and a recurrent network) named DFTNet (for Deep Fish Tracking Network). The first network used two identical neural networks to reidentify fish, and the second network is an LSTM that allows the AI model to learn from the fish’s chaotic motions.

In fishing activities, AI architecture with attention and memory is thus particularly important to address the chaotic patterns seen among species during capture process. Tracks can show swimming angles or abrupt changes in movement that measure distance from gear structures (Santos et al., 2020), mean trajectory in relation to the stimuli source (Peterson, 2022), selective device placement or difference in position of group or individual trajectories within gears. The visual features from automatic detection (i.e., color, texture, shape among species, group, or individual level) and the spatiotemporal features from tracking (i.e., swimming direction, angle, speed) (Figure 4H, I) can then be combined to define the behavior classification (Figure 4J, K).

3.3.2 Behavioral classes tailored with AI architecture

Fish behavior recognition is when a model can recognize a behavior based on tracking features identified as events. An event is a scene (Figure 4A, B) directly observed from videos, for example, when a group of fish swims out from fishing gear. The combination of fish detections and tracks (swimming patterns) can be categorized as a class “escapement”, and behavioral metrics can be derived from such events (see Figure 4J). Automatic behavior recognition is thus trained from classified sets of tracking features and is the final step in synthesizing chaotic fish swimming into distinguished sets of behaviors.

Classes of behaviors are defined by scientists and are used to label an image sequence or a video clip that shows a defined behavior. For example, a class label of escapement behavior can be defined from a clip of a fish passing through a mesh. This can be defined as when the detected body of the fish overlaps or touches the mesh. A behavior class of a fish not escaping is when the detected trajectory of the fish stays within the mesh barrier, or a class can consequently show it has escaped if the tracked fish is detected outside the gear. The option to label whether a fish has escaped is a detail that depends on the study’s classification decisions (i.e., either when the fish’s body is entirely outside the gear or as the fish passes through the mesh). Classes can also be separated into action, and non-action classes (see Table 3), where a defined behavior present in a video clip is labeled as the action class, and another clip presenting unchanged or normal fish movement is labeled with the non-action class. McIntosh et al. (2020) defined four features that translate the startling behavior of sablefish from their trajectories into measurable metrics: direction of travel, speed, aspect ratio, and Local Momentary Change metric. They combined the four features into a form suited to train an AI-based classifier with an LSTM architecture (i.e., tensor data). Like applying LSTM for tracking, an AI behavior recognizer with LSTM remembers important features efficiently to classify swimming movements (Niu et al., 2018; L. Yang et al., 2021). Behavior classes have been defined in selectivity studies as events classified in empirical models (Santos et al., 2016, Santos et al., 2020) or video tracking software (Noldus et al., 2001). J. Wang et al. (2020) proposed a method for real-world detections of anomalous behavior for multiple fish under high stress with a 3-stage pipeline. Examples of AI pipelines are summarized in Table 3, with the underwater scene, light source, and type of underwater observation system used included for comparison.

3.3.3 The problem of occlusion emphasized in the crowded scenes of fishing

The occlusion problem is when fishes overlap or swim behind one another, leading to a loss of fish detections and fragmentation of tracks (Gupta et al., 2021). Multiple objects tracking on videos is challenging since overlaps are flattened in a 2D view (See Figure 4C, D, F). This problem occurs when studying behaviors in crowded scenes of fishing. In 2D images and videos, training models to recognize the body parts of fish can help to overcome occlusion. In general, if a detector fails to locate an entire fish, a tracker can still follow the movement according to other features of the fish (i.e., fisheye, fins, tail). For example, Liu et al. (2019) simultaneously track the fish head and its center body so the head can be detected even when the center body is hidden. Therefore, trackers can maintain fish identity after occlusion happens if more appearance features are learned by the model (Qian et al., 2014). Fish heads have relatively fixed shapes and colors, so tracking them from frame to frame can still be done even after frequent occlusions (L. Yang et al., 2021). The darker color intensity of the head behind another and its elliptical shape can be characterized as a blob and still be tracked.

Three-dimensional tracking from stereo cameras or multiple camera systems where 3D components can be triangulated can help address occlusion problems. By reconstructing trajectories on a 3D view, fish trajectories are seen with depth, improving reidentifying a fish after an occlusion (Cachat et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2021) . However, AI models trained to recognize 3D trajectories demand computationally intensive algorithms to associate the deconstructed features together (L. Yang et al., 2021).

3.3.4 Transfer learning for data-deficient environments

We have shown that assessing fish behavior relies on analyzing trajectories. Considering tracks instead of detections generates even larger amounts of data than single detections of fishes on frames. Thousands to millions of such fish trajectories have likely been generated worldwide. These data may now be used to train models to detect fishes, at species level or as generic fish, in unseen environments. We provide a few examples of available published datasets that have been used to train models (Table 4).

Table 4

| Dataset | Access | Size | Included Fishes | Labels | Location | Source | References for model training | Content type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BYU (Brigham Young University) Fish dataset | http://roboticvision.groups.et.byu.net/Machine_Vision/BYUFish/BYU_Fish.html | 12 labelled species (2.5 GB) | 90 Asian Carp, 110 Crucian Carp, 74 Predatory Carp, and 89 Colossoma and four non-invasive species (120 Cottids, 137 Speckled Dace, 172 Whitefish, and 240 Yellowstone Cutthroat image) | Species | Not specified | Lillywhite and Lee, 2013 | Chua et al., 2011; Rasheed, 2021; Simons and Lee, 2021 | Images |

| Croatian Fish Dataset | http://www.inf-cv.uni-jena.de/fine_grained_recognition.html#datasets (currently not accessible) | ~700 images of 12 different fish species in real life conditions (120 images in training set and 674 in testing set) | Mixed | Species | Adriatic Sea in Croatia | Jäger et al., 2015 | Okafor et al., 2018; Qiu et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2021; Pang et al., 2022 | Images |

| DeepFish | https://github.com/alzayats/DeepFish | ~40,000 annotated classification labels, collected from 20 different habitats | Mixed in situ | Fish/no fish | Coastal marine environments in Australia | Saleh et al., 2020 | Laradji et al., 2020; Saleh et al., 2020 | Images |

| Deep Vision Fish Dataset | http://metadata.nmdc.no/metadata-api/landingpage/01d102345aef4639f063a13ea20cd3f3 | Two surveys 2017 to 2019 from Deep Vision system | Blue whiting, Atlantic herring, Atlantic herring, other mesopelagic fishes | Species | In situ from surveys + synthetic data | Allken et al., 2021b | Allken et al., 2021b | Images |

| FathomNET | http://fathomnet.org | ~80,000 images of marine animals, 106 000 localizations, 26 000 h videos, 6.8 million annotations, 4 349 terms | Mixed | Mixed | Worldwide | Boulais et al., 2020; Katija et al., 2021a | Katija et al., 2021b | Images and Videos |

| Fish4Knowledge (F4K) | http://www.perceivelab.com/datasets | 3.5k bounding fishes/700k 10-minute video clips | Species of tropical fishes | Fish/no fish | Taiwan coral reefs | Boom et al., 2014; Fisher et al., 2016 | Rathi et al., 2017; Pramunendar et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Alshdaifat et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Murugaiyan et al., 2021; Prasetyo et al., 2021; Knausgård et al., 2021 | Images and Videos |

| FishNet | https://www.fishnet.ai/ | 406,463 bounding boxes in 86,029 images from 73 different electronic monitoring cameras | Majority of species detected tuna species (albacore, yellowfin, Skippack, bigeye) | Species | From longline tuna vessels in western and central Pacific | Kay and Merrifield, 2021 | Mujtaba and Mahapatra, 2022 | Images |

| Fish-Pak | https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/n3ydw29sbz/3 | 915 images of carps with different orientation, position, mouth | Ctenopharyngodon idella, Cyprinus carpio, Cirrhinus mrigala, Labeo rohita, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix, and Catla catla. | Species | Pakistan, local farms, and river systems | Shah et al., 2019 | Shah et al., 2019 | Images |

| HabCam (Habitat Mapping Camera System) | https://habcam.whoi.edu/ | 2,500,000 images | Mixed marine vertebrates and invertebrates | Species | Not specified | Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) | Unknown | Images |

| J-EDI JAMSTEC E-library of Deep-sea Images) | https://www.godac.jamstec.go.jp/jedi/e/ | 1,500,000 images | Deep sea species | Species | Not specified | Japan Agency of Marine-Earth Science and Technology | Unknown | Images and Videos |

| LifeCLEF 2015/FISHCLEF/SeaCLEF | https://www.imageclef.org/2014/lifeclef/fish | 73 annotated videos | Species of tropical fishes | Species | Taiwan coral reefs | Joly et al., 2016 | Hossain et al., 2016; Salman et al., 2016; Salman et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Ben Tamou et al., 2021 | Videos |

| NINA204 | Not retrievable | 204 video clips (101 stocked fish and 103 wild fish) | Brown trout species | No fish/stocked fish/wild fish | Stocked fish and freshwater wild species in Norway | Pedersen and Mohammed, 2021 | Albawi et al., 2017; Myrum et al., 2019 | Videos |

| NorFisk | https://dataverse.no/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.18710/H5G3K5 | 12514 annotated images (timestamp 2021 as it is expected to grow from 2020 recorded footages) 3027 annotated images of saithe, 9487 of salmonids | Saithe and salmonids | Species | Norwegian fish farms using GoPro hero 4,5 and 8 cameras (49 hours of video) | Crescitelli et al., 2021 | Crescitelli et al., 2021 | Images |

| ONC Video Data | https://github.com/bonorico/analysis-of-ONC-video-data | 9772 video clips, 9205 annotated sablefish individuals | Sablefish | Species | Berkeley Canyon, North America | Bonofiglio et al., 2022 | Fier et al., 2015; Bonofiglio et al., 2022 | Videos |

| OzFish | https://github.com/open-AIMS/ozfish | 80k labeled crop images, 45k bounding box annotations, 507 species of fish | Mixed (e.g,. Scarids, Chlorurus, Capistratoides sp). | Species/no species, fish/no fish | Stereo BRUVS | Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), 2019 | Ditria et al., 2021b | Images |

| QUT Fish Dataset | https://www.dropbox.com/s/e2xya1pzr2tm9xr/QUT_fish_data.zip?dl=0 | ∼4000 classification images, 486 species | Mixed in situ | Species | Varying ex situ and in situ habitats | Anantharajah et al., 2014 | Qiu et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2020; Pang et al., 2022 | Images |

| RockFish/Labeled fishes in the wild | https://swfscdata.nmfs.noaa.gov/labeled-fishes-in-the-wild/ | 929 images with 1005 marked fish, 17 videos at 10min long, rate of 5 fps, ∼1k bounding boxes (fish) | Ground fishes | Fish/no fish | Southern California Bight from 2000-2012 surveys | Cutter et al., 2015 | Cutter et al., 2015 | Images and Videos |

| The Nature Conservancy Fisheries Monitoring Database | https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/the-nature-conservancy-fisheries-monitoring/data | Unspecified | Albacore tuna, Bigeye tuna, Yellowfin tuna, Mahi mahi, Opah, Sharks | Species | Mixed | The Nature Conservancy Fisheries | Pelletier et al., 2018 | Images |

| TROUT39 | Not retrievable | 39 images of brown trouts in 288 frames | Brown trout species | Species | Stocked fish and freshwater wild species in Norway | Pedersen and Mohammed, 2021 | Pedersen and Mohammed, 2021 | Videos |

| VOC2012/PASCAL Visual Object Class | http://host.robots.ox.ac.uk/pascal/VOC/voc2012/ | 17,000 annotated fishes | Unspecified | Fish/no fish | Unspecified | Everingham and Winn, 2012 | Li et al., 2021 | Images |

| WildFish | https://github.com/PeiqinZhuang/WildFish | ~2000 fish categories with 103,034 wild fish images based on several professional fish websites (e.g., Fish Base, Encyclopedia of Life, Fishes of Australia) | Mixed | Species | Mixed | Zhuang et al., 2021 | Pang et al., 2022 | Images |

Summary of public datasets of fish images and videos for AI model training merged from open access database, from collection of generic image datasets (with other objects not focused on fishes) and from Ditria et al. (2020); Saleh et al. (2020) and Pedersen et al. (2021).

For tropical fishes, Fish4Knowledge (F4K; Fisher et al., 2016), a project that started in 2010, garnered millions of images from GoPro cameras that were set-up in coral reef areas of Taiwan. The project resulted to 87K hours of video (95 TB) and 145 million fish identifications. It has then made the successfully curated database available to the rest of the world and most of the developments in automatic classification and identification tools for fishes have used the database to train deep learning models (see in Table 4 uses of F4K: Spampinato et al., 2010; Palazzo and Murabito, 2014; Shafait et al., 2016; Jalal et al., 2020; Murugaiyan et al., 2021). For temperate fishes, only a few commercial species can be automatically identified by existing models but are nonetheless gaining more recognition. Bonofiglio et al. (2022) trained an AI pipeline to detect and track sablefish, Anoplopoma fimbria, in an underwater canyon in North America on ~650 hours of video recording with ~9000 manual annotations. Due to growing fish databases and application of image processing techniques, AI models can now detect fishes with human-like accuracy in some species such as Scythe butterfly fish (Benson et al., 2013), some tropical species (Spampinato et al., 2010), and mesopelagic species (Allken et al., 2021a).

Studying fish-gear interactions is particularly difficult due to the unique and challenging conditions often met at sea. Pipelines of automatic detections have applied transfer learning and data augmentation techniques to cope with the lack of available data. For example, Knausgård et al. (2021) applied transfer learning to train an AI system to identify temperate fishes that are commercially valuable, such as wrasses (Ctenolabrus rupestris, C. exoletus and Sympohodus melops) and gadoids (Gadus morhua, Pollachius virens, P. pollachius, Molva molva, and Melanogrammus aeglefinus). Using models pre-trained on available public datasets (see Table 4, e.g., Fish4Knowledge and ImageNet), they obtained high accuracies in object detection and classification using their fine-tuned models (86.96% and 99.27%, respectively). Transfer learning from pre-existing object detection algorithms coupled with existing data from other environments can thus be a promising approach for the automatic analysis of fish species even from environments that still lack data (Fisher et al., 2016; Siddiqui et al., 2018; Knausgård et al., 2021), additional augmentation methods, such as generating synthetic datasets, may help overcome the insufficiency of small datasets for training models (Allken et al., 2019; Villon et al., 2021).

4 Discussion

4.1 Insights from AI applications for behavior recognition from other domains

Automated behavior recognition has been applied to several domains outside of fisheries. Dynamic systems of fish schools, just as any large groups of moving individuals such as birds or insects (Chapman et al., 2010; Altshuler and Srinivasan, 2018), will produce a bundle of condensed and interloping trajectories when tracked. Directional patterns of behavior (i.e., individual or collective) can be interpreted from them (Sinhuber et al., 2019), but visual details of targets can be lost in footages due to occlusions or motion blur (Liu et al., 2016). Conveniently, apart from data enhancement methods, there are already available algorithms and AI methods that particularly addresses this challenge in natural systems of humans, social animals and insects (i.e., Swarm Intelligence; Ahmed and Glasgow, 2012, Boids algorithms; Alaliyat et al., 2014). Algorithms to track behavior in congested human crowds have been developed based on motion capture and optical flow techniques (Krausz and Bauckhage, 2011). Different types of human behavior can now be recognized by AI in all sorts of environment due to the considerable attention in the domain and since high performing models learn from a gigantic amount of training database of diverse human behavior (Popoola and Wang, 2012; Vinicius et al., 2013).

Three-dimensional motion capture techniques can also provide more information such as depth and detailed tracking of animal paths (Wu et al., 2009). Moreover, 3D trajectories can provide the analytics (i.e., positions, velocities, accelerations) to study cohesive and unique behaviors (Sinhuber et al., 2019). For instance, Liu et al. (2016) proposed an automatic tracking system that can reconstruct 3D trajectories of fruit flies using three high-speed cameras that can be generally adapted to large swarms of moving object. Dollár et al. (2012) made use of features of human pedestrians to geometrically quantify their overlaps and distances on a 2D scale. The AI models that recognize facial features and postures of humans or other animals therefore have the algorithmic backbone to extract behavior. Since algorithms can be scalable and adaptable (see Section 3.3.4 on transfer learning), such Al models may now be adapted to fish features and postures.

4.2 Towards smart fishing

The way we fish is constantly evolving. The more we understand the impact of fishing, the more we look for ways to make our fishing gears more selective. We are not just modifying the components of gears anymore but also adding devices and camera systems to them to create intelligent fishing gears. This turns fishing operations into interactive, fine-scale observations platforms rather than catch-then-see operations (Rosen et al., 2013; Kyllingstad et al., 2022). Performances of modified fishing gears can almost be assessed real-time which can elevate the plateau of gear selectivity studies by exploring fish-gear interactions at finer scales. The challenge now lies on obtaining consistent findings from these direct observations. In highly stimulating, crowded, and stressful scenes in fishing activities, subtle movements of fishes may turn into sharp and chaotic escapes where learned behavior and predispositions are overcome by survival instincts (Manière and Coureaud, 2020). Large volumes of fishes can also be influenced by herding behavior and individuals may tend to follow swimming routes of the group (Måløy et al., 2019). Addressing this herding constrain currently relies on applying complex pipelines, often coupled with stereovision (Rosen et al., 2013; Kyllingstad et al., 2022). Handling such data in real-time is one of the current bottlenecks because it has to be processed within embedded AI systems. To equip fishing gears, these embedded systems have to remain as light as possible, with controlled size, memory and power consumption. These issues will be partially solved as the algorithms presented above (see Section 3.3: The problem of occlusion emphasized in the crowded scenes of fishing and Table 3) keep improving in handling the occlusion problem, and as the observation systems keep improve to meet the image quality required for AI applications (see Section 2.1 Observations of fish behavior in fishing gears and Table 1).

In the meantime, AI may already facilitate the assessment of fishing gear modification. When a fishing gear is designed with a new stimulus (e.g., Southworth et al., 2020; Ruokonen et al., 2021) or when its parts are modified (e.g., Feekings et al., 2019), the certainty that they dominantly cause a change in behavior of fishes leading to escapes or retention is impossible to single out due the large variability in external and internal factors affecting the fishes’ responses. It is also unlikely that the exact movements by the same community of fishes can be observed upon two successive occasions (Ryer and Barnett, 2006; Ryer et al., 2010; Lomeli and Wakefield, 2019). Applying automatic behavior recognition in such situations would enable to process much larger amount of data on fine-scale differences than what could be done manually, even if it comes with some levels of errors inherent to using any fully automatic recognition algorithm (Faillettaz et al., 2016; Villon et al., 2021). Complementary laboratory studies may also help collect consistent findings (Hannah and Jones, 2012), which are needed to gather a database of automatically classifiable behaviors. For example, the influence of light intensity on juvenile walleye pollock Theragra chalcogramma were studied in laboratory conditions and in situ and showed that juveniles either struck the nets more often or swam closer to them in darkness than at the highest illumination (Olla et al., 2000). Such systematic behavioral responses could thus be used to train an AI model which could then be used to automatically analyze replicates of additional trials. Similarly, AI applications would enable to amplify the number of replicates of sea or laboratory trials, for example when assessing how changes in the positions of stimuli influences species behaviors (Larsen et al., 2017; Yochum et al., 2021).

4.3 Sharing and collaboration for the sake of fishes

Transferred learning of adaptable deep learning models from other behavioral studies and sceneries is key for automated fish behavior recognition, but technically executing this requires collaboration among the scientific community. The advances of fish behavior recognition in aquaculture and in situ environments often stem out of joint efforts between ecologists and computer scientists. AI practitioners mostly have the knowledge on which algorithm or AI network can be appropriated to specific study cases, while marine scientists provide the underlying ecological question and the inherent parameters (i.e., classification of fish behaviors, metrics for quantification) to fine-tune the algorithms. Automated behavior recognition models that are successful have benefited from huge streams of imagery data and unprecedented fundings in terms of technological specifications. Existing and previous data mining and collection practices included outsourcing efforts. Fish4Knowledge branched out to volunteers, subprojects, and gamifying techniques (Fisher et al., 2016). Popular datasets such as ImageNet and COCO used Amazon Analytics to crowdsource annotations of objects (Gauen et al., 2017). McClure et al. (2020) discussed that citizen science is beneficial for AI applied in ecological monitoring as it can fast track data collection since AI is now within reach because of integration in mobile devices and user-friendly platforms. The phytoplankton world is benefitting from citizen science as online portals are used by volunteers to do simple classification tasks that has led to millions of plankton ID’s to be verified (Robinson et al., 2017). Moreover, scientists are adapting FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse) data principles to realize the full value of fish behavior data and to carefully curate a unifying database (Guidi et al., 2020; Bilodeau et al., 2022).

Bridging the gap between computer and marine sciences can accelerate the development of powerful tools for automated fish monitoring (Goodwin et al., 2021). User-friendly software platforms for image processing and analysis of animal tracks and events are publicly accessible and designed for non-AI experts (Dawkins et al., 2017). So even if observations of fish-gear interactions are more demanding in terms of observation requirements that can produce small sizes of data and are distinctly case-specific, training models can still be aided by means of data transfer, open-access databases, and participatory platforms. This will be beneficial for everyone as end-tools that grow in performance will also grow in scalability thanks to shared data. If there are enough collaborations across domains, extensive engagement with fish ethologists to construct behavioral classifiers, consistent sharing of reproducible, understandable, and scalable data then it might become possible to quantify, in near completeness, what a fish is doing or how it is interacting with its environment in any conditions.

4.4 Limitation of AI: A critical view

AI-adapted electronic fishing is still fairly new to fisheries so practical applications to improve selectivity of fishing gears may not be seen directly. AI models are dependent on the quality of the training data and imagery is still currently lacking. Contrary to fisheries-based observation, land- and air-based behavior studies have more opportunity to use AI for automatic behavior recognition as aerial and terrestrial devices can be smaller and lighter than underwater camera systems (e.g., Rosen and Holst (2013) for an underwater example; Liu et al. (2016) for a land example).

The environmental impact of these developing hardware and software systems in fisheries must not also be taken for granted. They may reduce operational energy consumption with automation but if intelligent tools are eventually applied in a commercial level, this may imply significant extraction of heavy metals to manufacture the hardware and increase in the carbon footprint of storage servers (Gupta et al., 2022). Scientists should be cautious to not be swept away by the promise of intelligent fishing without also seeking the environmental cost of making and maintaining it. AI application may tip the scale in favor of fishes but the integration of AI to fisheries must be accompanied by environmental impact assessments and an active search for alternative materials for machines.

Furthermore, our perception of animal behavior can be anthropomorphic, and this bias may be transferred to artificial tools. Researchers have consistently indicated the possible transfer of human bias into artificial intelligence that can be worsened by training models with limited data (Horowitz and Bekoff, 2015). As of today, human still need to be cautious in identifying behavioral both in manual and automatic methods; unsupervised learning may help get rid of anthropomorphic biases (Sengupta et al., 2018).

Another critical view of the use of AI in fisheries sustains the reality that it can be a double edge sword. On one hand, it may help scientists understand fish behavior and reduce bycatch (e.g., Knausgård et al., 2021; Sokolova et al., 2021). On the other hand, it may help the fishing industry to increase their catch with the use of automated tools (Walsh et al., 2002). As with any other technological advancement, the practical nature of it stems on how humans decide to use them (Bostrom and Yudkowsky, 2018). It is therefore in the hands of stakeholders to discuss among one another, to stress both the negative and positive impacts of AI, and to lay down ethical practices to prevent mishandling of this new technology. Debates in using AI tools in fisheries arise but if we go forward with the intention to help address ecological problems and emphasize its use for selectivity, then it may build the tools for a sustainable use of our resources.

4.5 Navigating a rapidly evolving field of research

The main challenge of studying fish-gear interactions is not of lack but of abundance. The growing data in fish behavior and existing footages of their interactions with gears carry with them the vital information for better gears waiting to be synthesized. Automating the methods of data collection and process not only unlatches the time and effort given by scientists from laborious practices but also liberates the focus unto deeper scientific and creative endeavors. User-friendly platforms that translate complex AI algorithms into software tools can encourage interest even from non-practitioners to participate in model training and fish tracking.

As we write this review, powerful and cognitive AI models in the field of computer science are advancing in an unparalleled speed. This will inevitably pour into the development of models for fisheries. AI applied in other sectors have cognitive understanding allowing machines to have higher level of ability of induction, reasoning and acquisition of knowledge. The evolution of future AI models for automatic recognition of fish-gear interactions now depends on multiple factors:

-

- First is the careful and accurate classification of fish trajectories that considers 3D components in a moving world.

-

- Second is the adaptation and re-training of pre-trained models from different human and animal behavioral studies.

-

- Third is the production of scalable and adaptable models for different case studies in gears and the shareability of fish behavior data among scientists.

-

- Fourth is the reliance on a continued and harmonious engagement of both marine scientists and AI practitioners to develop cognitive AI for fish-gear interaction systems.

There is no magic gear that completely selects targeted species, allow all unwanted species to escape, and has no economic and biological losses. However, equipping fishing gear with state-of-the-art technologies may help address ecological problems, understand overlooked species’ behavior and make our fishing practices more sustainable, laying the right track as we step into a technological era.

Statements

Author contributions

AA, DK, RF conceptualized the content of the review. AA conducted the bibliometric analysis, generated the illustrations and drafted the initial manuscript. DK, RF wrote, commented and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was done as a part of the Game of Trawls S2 project, funded by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and France Filière Pêche (PFEA390021FA1000002). AA’s PhD program is funded by IFREMER (grant DS/2021/10).

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Abdelbadie Belmouhcine for his valuable insights on deep learning methods, to Sonia Méhault, Julien Simon and Pascal Larnaud for the discussion on gear selectivity, to Marie Savina-Rolland for her comments on the manuscript and to Megan Quimbre (IFREMER, Bibliothèque La Pérouse) for the bibliometric analysis. The authors are also grateful to the two reviewers for their time and criticisms which greatly improved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1