Abstract

Marine litter colonization by marine invertebrate species is a major global concern resulting in the dispersal of potentially invasive species has been widely reported. However, there are still several methodological challenges and uncertainties in this field of research. In this review, literature related to field studies on marine litter colonization was compiled and analyzed. A general overview of the current knowledge is presented. Major challenges and knowledge gaps were also identified, specifically concerning: 1) uncertainties in species identification, 2) lack of standardized sampling methodologies, 3) inconsistencies with the data reported, and 4) insufficient chemical-analytical approaches to understand this phenomenon. Aiming to serve as a guide for future studies, several recommendations are provided for each point, particularly considering the inaccessibility to advanced techniques and laboratories.

1 Introduction

Marine litter is defined as all synthetic, or processed material, discarded, disposed or abandoned in the marine environment or beaches. One of the possible classifications of litter is based on material categories, such as plastics, metals, and glass, among others, and one of the main types of litter found in these environments is plastic (Ribeiro et al., 2021; Póvoa et al., 2022). Plastics are some of the most widely used materials in virtually all industries and commercially available products (Andrady and Neal, 2009; Hahladakis et al., 2018). Since the 1950s, plastic production has increased continuously due to its versatility, lightweight, resistance to corrosion, and low production costs (Andrady, 2017; Tuladhar and Yin, 2019; Torres and De-la-Torre, 2021). However, due to insufficient solid waste management systems, infrastructure and reach, as well as the lack of environmental awareness (Prata et al., 2020; Mihai et al., 2021; Wichmann et al., 2022), plastic pollution has become one of the major issues threatening the world oceans (Walker, 2018; Chassignet et al., 2021; Haarr et al., 2022; De-la-Torre et al., 2022b). Upon entering marine and coastal environments, plastic litter interacts with biota in multiple ways (Costa et al., 2022). For instance, plastic ingestion and entanglement or entrapment are recognized as some of the most impactful plastic-biota interactions, which could compromise the survival of many top predators, such as marine birds, turtles, and mammals (Poeta et al., 2017; Battisti et al., 2019; Staffieri et al., 2019; Santillán et al., 2020; Ammendolia et al., 2022; Fukuoka et al., 2022; Provencher et al., 2022). A less considered plastic-biota interaction is the fouling of plastic litter surfaces, thus, acting as substrates for the development of invertebrate species or microbial communities (Barnes, 2002; Gong et al., 2019; Pinochet et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2021) (Figure 1). The most of plastic litter is affected by ocean surface currents due to the positive buoyancy of this object in seawater, possibly travelling for interoceanic distances (Maes and Blanke, 2015; Luna-Jorquera et al., 2019; Thiel et al., 2021). Other types of litter might reach the bottom sediments and being colonized by benthic organisms. However, less dense material can later detach or resurface. The transport of colonized litter for long distances is known as ocean rafting (Tutman et al., 2017). This phenomenon represents a threat to foreign ecosystems through the arrival of plastic rafts, which have been reported to host alien invasive species (AIS) (Rech et al., 2016; Rech et al., 2018b; Gracia and Rangel-Buitrago, 2020).

Figure 1

Examples of a plastic bottle (A) colonized by the bivalve Semimytilus algosus(B), anemones (Order: Actiniaria) (C) y bristle worms (Class: Polychaeta) (D), and a rubber boot (E) colonized by Balanus sp. (F). (Photographs by G.E.D.).

AIS is defined as exotic species that could potentially generate an impact on the ecosystem they invade (Koh et al., 2013). Upon settlement in a foreign environment, AIS may lead to the displacement of native species, particularly endemic ones, and are very difficult to eradicate (García-Gómez et al., 2021). They also represent a significant economic cost, as they compromise natural resources used to produce market goods and services (García-Gómez et al., 2021). While non-native species are able to travel long distances by natural means, like attaching to migratory biota (Thiel and Gutow, 2005), the influence of anthropic activities is undeniable. For instance, sessile species may be transported attached to ship hulls (Hänfling et al., 2011), transported in ship ballast water (Walker et al., 2019), and, as aforementioned, floating plastic litter may also act as a vector of AIS (Tutman et al., 2017; Rech et al., 2021). The latter has been subject to significant research in the last decade (Póvoa et al., 2021). However, multiple factors influencing the transportation of AIS through floating litter remain poorly understood, such as the main types of litter and polymers carrying attached biota, significant donors and recipients of colonized litter, and their overall contribution to the global issue of AIS dispersal (Rech et al., 2016).

Due to the relevancy and risk that marine litter represents for the dispersion of non-native and potentially invasive species, multiple authors have compiled and analyzed the literature. For instance, Kiessling et al. (2015) compiled studies on organisms that inhabit floating marine litter. The characteristics of the litter and biological traits of associated species were analyzed to understand their colonizing behavior. However, in the last six years, recent studies have allowed researchers to elucidate new findings related to marine litter colonization that were not previously understood, such as the influence of chemical-analytical aspects of synthetic substrates and the use of genetic identification of fouling species (e.g., molecular analyzes). More recently, García-Gómez et al. (2021) carried out a literature search aiming to compare the potential of plastic as a vector of non-native species compared to other sources of dispersal (e.g., ship hull biofouling and ballast waters). Also, their analysis of the composition of fouling communities on marine litter substrates, primarily plastic, indicated that these species generally have a short life cycle and larval development. Póvoa et al. (2021) conducted a literature review focused on the research questions proposed by Rech et al. (2016) and Gracia C. et al. (2018). Although the aforementioned studies correctly compiled information regarding marine litter colonization and carried out multiple analyzes, it is necessary to carry out an updated literature search to analyze the multiple challenges that remain in this field of research. Hence, in the present review, an updated overview of the current knowledge regarding the occurrence of marine litter colonized by marine macroinvertebrates is provided. We aim to identify and discuss the various factors surrounding this field of research and establish key recommendations to guide future studies, particularly concerning sampling, species identification, litter data reporting, and chemical characterization methodologies.

2 Literature search methodology

The literature search was conducted adjusting De-la-Torre et al.’s (2022a) criteria to the topic of the present study. On the 10th of August 2022, the Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/) database was consulted with the keywords “litter” OR “plastic” in conjunction with “fouling” OR “rafting” OR “invasive species” OR “non-native” OR “biological invasion” in conjunction with “marine” OR “ocean”. The search was carried out within the title, abstract, and keywords of the documents in the database. Publication year intervals were set from 2000 to 2023. Additionally, three document types (editorials, book chapters, and reviews) and the subject areas (Computer Science, Social Sciences, Mathematics, Economics, and Business management) were excluded from the search. The search resulted in 274 documents, which were exported to the virtual platform Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/), where the title and abstract of each document were revised in detail to determine whether to include or exclude studies according to a specific criteria. Studies were included if reports of colonizing organisms on marine litter (either marine or coastal zones), including those recovered from benthic areas, were presented. Only field studies (e.g., marine litter surveys) were included. Studies conducting involving litter colonization under controlled experimental conditions were excluded from the analysis.

3 Results and discussion

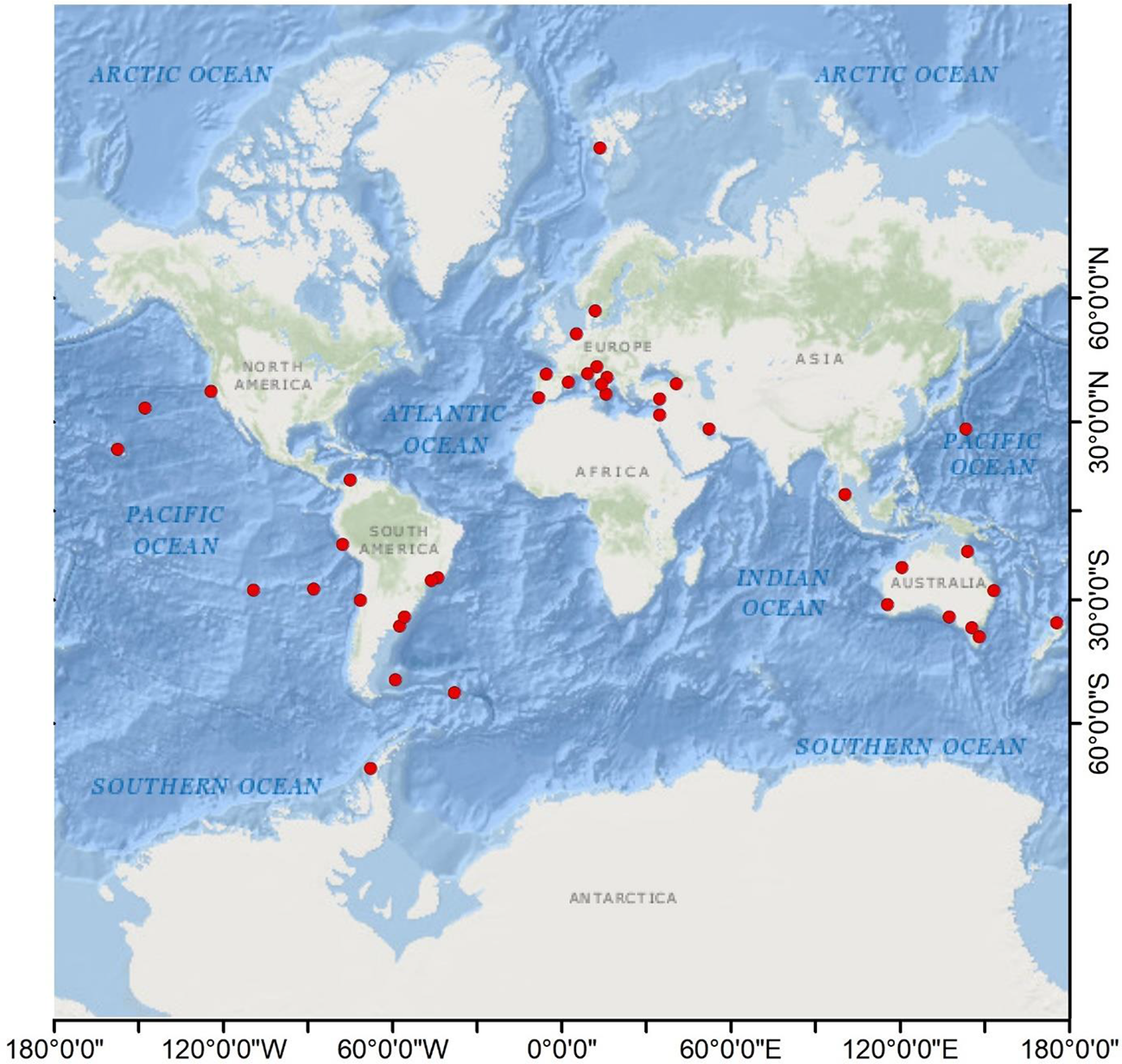

A total of 39 documents were selected. Relevant information (time, location, environmental matrix, number of species, type of litter, and sources) from each study was extracted to obtain a better understanding of the current state of the knowledge. Table 1 summarizes the main elements of each study. Additionally, a geographic map was constructed indicating the main locations of each of the consulted studies (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, most studies were conducted in South America, Oceania, and Europe, with a single study reported on the Antarctic Peninsula by Barnes and Fraser (2003), while East Asia and Africa have been poorly assessed, as well as the coasts surrounding the Indian Ocean, and the east coast of North America. It should be mentioned that the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami sparked various studies conducted in the following years investigating marine litter arriving from Japan to North America (North Pacific Ocean) (Carlton et al., 2017; McCuller and Carlton, 2018; Póvoa et al., 2021).

Table 1

| Country | Specific zone | Environmental Matrix | Sampling year | Sampling type | Species list 1 | Taxonomic class 2 | Type of litter | Source | Polymer types | Ref. |

| Peru | Lima-Cañete | Beach | 2019-2020 | Whole beach survey |

Balanus laevis

Semimytilus algosus Prisogaster niger Alia unifasciata Perumytilus purpuratus Hyalella sp. Tetrapygus niger Ocypode occidentalis Emerita analoga Chiton cumingsii Tegula atra |

Bivalvia Gastropoda Thecostraca Ophiuroidea Malacostraca Polychaeta Echinoidea Polyplacophora |

Clothing Bottles Food containers Plastic bags Sheetings Monofilament line Fishing net Other plastic Timber |

Land-based (81.5%) Sea-based (18.5%) |

Polyester/PET (18.5%) Nylon/PA (11.1%) PP (25.9%) LDPE (22.2%) Latex (3.7%) |

(De-la-Torre et al., 2021) |

| Spain | Gijon port | Beach | 2017 | Whole beach survey |

Platynereis dumerilii

Syllis gracilis Mytilus edulis Patella vulgata |

Polychaeta Bivalvia Gastropoda |

Plastic bag Bottles Fabric Buoy Fishing gear EPS Plastic debris |

Land-based Sea-based |

– | (Ibabe et al., 2020) |

| Pacific Ocean | North Pacific Subtropical Gyre | Ocean | 2012 | Floating debris picked up manually | Class: Hydrozoa Actiniidae Family: Actiniidae Family: Metridiidae Amphinome rostrata Chaetopterus sp. Parasabella sp. Hipponoe gaudichaudi Lepidonotus sp. Mytilus sp. Fiona pinnata Lottia pelta Lepas spp. Idotea metallica Pentidotea wosnesenskii Glebocarcinus amphioetus Plagusia squamosa Planes major Planes marinus Membranipora spp. Psenes sp. Pomacentridae |

Hydrozoa Hexacorallia Polychaeta Bivalvia Gastropoda Thecostraca Malacostraca Gymnolaemata Actinopterygii |

Buoy Toy ball Bottle cap Flat piece of plastic Bottle Boat bumper |

Land-based Sea-based |

– | (Gil and Pfaller, 2016) |

| Turkey | Sarayköy Beach | Beach | 2016-2017 | OSPAR transect protocol |

Mytilus sp. Family: Balanidae Class: Gastropoda Phylum: Bryozoan |

Bivalvia Thecostraca Gastropoda |

Plastic bottle Foam Shoe |

Land-based | – | (Aytan et al., 2019) |

| Brazil | Ilha Grande Bay | Beach | 2018-2020 | Along the strandline |

Amphibalanus

improvisus Amphibalanus reticulatus Amphibalanus sp. Newmanella radiata Lepas anatifera Ostrea puelchana Saccostrea cuculatta Hydroides elegans Hydroides sp. Family: Membraniporidae Tubastraea coccinea Tubastraea sp. Tubastraea tagusensis |

Thecostraca Bivalvia Polychaeta Gymnolaemata Anthozoa |

Caps Shoes Buoy Shoes Rubbers Styrofoam Plastic fragments |

Land-based Sea-based |

– | (Póvoa et al., 2022) |

| Brazil | Ilha Grande Bay | Beach and deep sea | 2012-2014 (Benthos) 2018-2020 (Beach) |

Scuba diving Along the strandline |

Tubastraea coccinea

Tubastraea tagusensis |

Hexacorallia | Buoy EPS Rope Electric cable Flip-flop (shoe) Wood Tire Glass bottle |

Land-based (75%) Sea-based (25%) |

– | (Mantelatto et al., 2020) |

| Spain | Catalan Sea (NW Mediterranean) | Beach and sea | 2020-2021 (Trawling) 2020 (Beach) |

Trawling Along the strandline |

Spirobranchus triqueter

Novocrania sp. Chorizopora brongniartii Scyliorhinus sp. Arbopercula tenella Aetea sica Annectocyma sp. Cryptosula pallasiana Fenestrulina malusii Phallusia mammillata Ophiothrix fragilis Barbatia barbata Aplousina sp. Copidozum tenuirostre Escharella variolosa Hagiosynodos latus Myriapora truncata Plagioecia sp. Reptadeonella violacea Schizomavella cornuta Schizoporella dunkeri Alcyonium palmatum Eunicella verrucosa Lepas anatifera Leptogorgia sarmentosa Neopycnodonte cochlear |

Polychaeta Craniata Gymnolaemata Chondrichthyes Stenolaemata Ascidiacea Ophiuroidea Bivalvia Stenolaemata Anthozoa Thecostraca |

Not specified | – | PE (47%) PP (13.7%) PET (11.8%) Chlorinated poly-ethylene (CPE) (9.8%) PS (7.8%) PU (3.9%) PVC (3.9%) PA (2.0%) |

(Subías-Baratau et al., 2022) |

| Argentina | Mar Chiquita, Buenos Aires | Beach | 2017-2018 | Debris collected from bins at beach |

Amphibalanus improvisus

Brachidontes rodriguezii Ostrea sp. Membranipora sp. Amphisbetia operculata Class: Polychaeta |

Thecostraca Bivalvia Gymnolaemata Hydrozoa Polychaeta |

Fishing line Buoy Fishing rope Cap Swim googles Strap Plastic bottle Sunglasses Food film Backpack strap Electric cable Aluminized paper Hose Tire Other plastics |

Land-based (66.6%) Sea-based (33.3%) |

– | (Rumbold et al., 2020) |

| Croatia | Mar Adriático | Sea | 2014 | Floating debris picked up manually |

Planes minutus

Liocarcinus navigator |

Malacostraca | Tire Sandal Shoe |

Land-based (100% | – | (Tutman et al., 2017) |

| Colombia | Atlantico department | Beach | NS | Transect protocol |

Arbopercula tenella

Arbopercula angulata 3 unidentified bryozoan Lepas anserifera Class: Polychaeta |

Gymnolaemata Thecostraca Polychaeta |

Wood Propagule Plastic debris Cap Plastic jar Plastic bottle Plastic ring Paint pot Glass bottle Other plastics |

Land-based | – | (Gracia C. et al., 2018) |

| Colombia | Atlantico and Magdalena department | Beach | 2018 | – | Perna viridis | Bivalvia | Buoy | Sea-based | – | (Gracia and Rangel-Buitrago, 2020) |

| Italy and Portugal | Venice and Algarve | Beach | 2016 | Whole beach survey |

Austrominius modestus

Amphibalanus amphitrite Anomia epphipium Hesperibalanus fallax Magallana angulata Bugula neritina Balanus trigonus Hiatella arctica Hydroides sanctaecrucis Hydroides elegans Sabellaria alveolata Serpula vemicularis Spirobranchus triqueter Lepas pectinata Lepas anatifera Mytilus edulis Mytilus galloprovincialis Mytilus sp. Modiolula sp. Ostrea edulis Chthamalus montagui Perforatus Verruca stroemia Class: Ophiuroidea |

Thecostraca Bivalvia Gymnolaemata Polychaeta Ophiuroidea |

Buoy Mussel bag Fishing trap Ropes Plastic bottles Other plastics Processed timber |

Land-based (36%) Sea-based (64%) |

– | (Rech et al., 2018b) |

| Chile | Easter Island | Beach | 2017 | Along the strandline | Family: Serpulidae Planes major Halobates sericeus Lepas anatifera Chthamalidae sp. Jellyella eburnea Pocillopora sp. Class: Hydrozoa Other |

Polychaeta Malacostraca Insecta Thecostraca Gymnolaemata Anthozoa Hydrozoa |

Bottle caps Plastic bottles Crates/Baskets Fishing gear Rope Other plastic |

Land-based Sea-based |

– | (Rech et al., 2018c) |

| Australia | Victoria | Beach | 2019 | Not specified | Lepas pectinata | Thecostraca | Bottle | Land-based | – | (Cooke and Sumer, 2021) |

| Spain | Asturias | Beach | 2016 | Whole beach survey |

Amphibalanus amphitrite

Austrominius modestus Perforatus Chthamalus stellatus Neoacasta laevigata Lepas anatifera Lepas pectinata Pachygrapsus marmoratus Polybius henslowii Magallana gigas Mytilus edulis Mytilus galloprovincialis Mytilus trossulus Tritia reticulata Eumida bahusiensis Neodexiospira alveolata Paragorgia arborea |

Thecostraca Malacostraca Bivalvia Gastropoda Polychaeta Anthozoa |

Bottles Fishing gear |

Land-based (~40%) Sea-based (~60% |

– | (Miralles et al., 2018) |

| Italy | Ganzirri (Sicily) | Beach | 2016-2019 | Not specified |

Megabalanus tulipiformis

Pachylasma giganteum Octolasmis sp. Adna anglica Alcyonium coralloides Coenocyathus cylindricus Desmophyllum pertusum Desmophyllum dianthus Family: Caryophylliidae Madrepora oculata Order: Zoantharia Errina aspera Sertularella sp. Family: Sertulariidae Class: Hydrozoa Pedicularia sicula Neopycnodonte cochlear Striarca lactea Family: Serpulidae Metavermilia multicristata Vermiliopsis sp Filogranula sp. Filogranula gracilis Filograna sp Semivermilia agglutinata Semivermilia sp. Serpula vermicularis Placostegus tridentatus Sycon raphanus Order: Cheilostomatida Celleporina sp Cellepora sp Haplopoma sp. Cellaria salicornoides Puellina cfr gattyae Puellina sp. Order: Cyclostomatida |

Thecostraca Anthozoa Hydrozoa Gastropoda Bivalvia Polychaeta Calcarea Gymnolaemata Stenolaemata |

Fishing gear | Sea-based | – | (Battaglia et al., 2019) |

| USA | – | Beach | 2012-2017 | Not specified | 289 species | – | vessels, docks, buoys, totes (crates), wood, and many other objects, identified as JTMD | Land-based Sea-based |

– | (Carlton et al., 2017) |

| Spain | Asturias | Beach | 2016 | Whole beach survey |

Lepas anatifera

Lepas anserifera Lepas pectinata Dosima fascicularis Austrominius modestus Chthamalus stellatus Chthamalus montagui Balanidae sp Verruca stroemia Caprella andreae Mytilus edulis Mytilus galloprovincialis Mytilus sp Crassostrea gigas Ostrea stentina Gibbula umbilicali Spirobranchus triqueter Spirobranchus taeniatus Serpula columbiana Neodexiospira sp. Spirobranchus sp. Bougainvillia muscus Obelia dichotoma Helix aspersa |

Malacostraca Thecostraca Malacostraca Bivalvia Gastropoda Polychaeta Hydrozoa |

Hard plastic Other plastic Foam Non-plastic |

Land-based Sea-based |

– | (Rech et al., 2018a) |

| Sweden | Gothenburg | Beach | – | Transect protocol | 63 species | Bivalvia Phylum: Bryozoan Polyplacophora Gastropoda Malacostraca Polychaeta Thecostraca Others |

Glass Ceramic Wood Fabric Metal Plastic |

– | – | (Garcia-Vazquez et al., 2018) |

| South Pacific Ocean | – | Ocean | 2015-2017 | Floating debris recovery using nets, trawls, and snorkeling |

Campanulariidae sp. 1 Campanulariidae sp. 2 Obelia sp. Pocillopora sp. Fiona pinnata Hipponoe gaudichaudi Lepas sp. Lepas pectinata Order: Amphipoda Stenothoe gallensis Caprella andreae Planes minutus Planes marinus Idotea metallica Idotea sp. Jellyella eburnea Jellyella tuberculata Hirundichthys sp. Cheilopogon sp. Others |

Hydrozoa Anthozoa Gastropoda Polychaeta Thecostraca Malacostraca Gymnolaemata |

Plastic pieces Jerrycans and buckets Crates and baskets Buoys Others |

Land-based (28.8%) Sea-based (41.2%) |

PP (3.4%) EV (3.4%) PE (93.1%) |

(Rech et al., 2021) |

| Norway | Svalbard | Beach | 2017 | Transect protocol |

Electra spp. Eucratea loricata Lepas anatifera Semibalanus balanoides Class: Gastropoda Mytilus sp. |

Gymnolaemata Thecostraca Gastropoda Bivalvia |

Fishing box Barrel Containers |

Land-based Sea-based |

– | (Węsławski and Kotwicki, 2018) |

| Malaysia | Penang and Langkawi | Beach | – | Whole beach survey |

Acanthodesia perambulata

Acanthodesia irregulata Jellyella eburnea |

Gymnolaemata | Plastic debris Glass bottle |

– | – | (Taylor and Tan, 2015) |

| Chile | Coquimbo | Ocean | 2001-2005 | Floating debris picked up manually | 102 species | Ascidiacea Polychaeta Malacostraca Thecostraca Others |

Buoys | Sea-based | – | (Astudillo et al., 2009) |

| Antarctica | Adelaide Island | Beach | 2003 | Not specified |

Laevilitorina antarctica

Aimulosia antarctica Arachnopusia inchoata Ellisina antarctica Fenestrulina rugula Micropora brevissima Others |

Demospongiae Polychaeta Hydrozoa Gastropoda |

Plastic band | Land-based | – | (Barnes and Fraser, 2003) |

| Uruguay | Rocha department | Beach | 2014 | Not specified | Pinctada imbricata | Bivalvia | Rope | Land-based | – | (Marques and Breves, 2014) |

| Brazil | Rio de Janeiro | Beach | 2012 | Not specified | Petaloconchus varians | Gastropoda | Marine debris | – | – | (Breves and Skinner, 2014) |

| The Netherlands | Texel | Beach | 2009 | Not specified | Favia fragum | Anthozoa | Metal cylinder | – | – | (Hoeksema et al., 2012) |

| Brazil | Sao Paulo Rio de Janeiro |

Beach | – | Not specified |

Tubastraea coccinea

Tubastraea tagusensis |

Anthozoa | Styrofoam | – | – | (Faria and Kitahara, 2020) |

| Iran | Coast of the Persian Gulf | Beach | 2016-2018 | Along the strandline |

Amphibalanus amphitrite

Microeuraphia permitin Striatobalanus amaryllis Chthamalus barnesi Spirobranchus kraussii Spirorbis sp. Hydroides sp. Saccostrea cucullata Isognomon legumen Class: Bivalvia Diodora funiculata Chiton sp. Parasmittina egyptica Microporella browni Antropora tincta Paracyathus stokesii Class: Ascidiacea |

Bivalvia Gastropoda Thecostraca Polychaeta Polyplacophora Gymnolaemata Anthozoa Ascidiacea |

Plastic Wood Glass Metal cans |

– | – | (Shabani et al., 2019) |

| North Pacific Ocean | – | Ocean | 2009-2012 | Floating debris picked up with a net | 95 species | Polychaeta Malacostraca Thecostraca Pycnogonida Gymnolaemata Stenolaemata Perciformes Phylum: Chordata Heterotrichea Anthozoa Hydrozoa Ophiuroidea Polythalamea Bivalvia Gastropoda Rhabditophora Turbellaria Calcarea Demospongiae |

Rigid fragment Rope clumps Flexible substrates Expanded foam |

– | – | (Goldstein et al., 2014) |

| Stewart Island Falkland Island Bird Island |

– | Beach | 2001-2004 | Not specified | Lepas australis | Thecostraca | Plastic debris Wood |

– | – | (Barnes et al., 2004) |

| New Zealand | Western Coromandel Peninsula | Beach | 2015-2016 | Transect protocol | NS | Phylum: Porifera Phylum: Hydrozoa Phylum: Bryozoa Phylum: Arthropoda Phylum: Mollusca Phylum: Annelida |

Plastic Ceramic/glass Metal Cloth Foam Rubber Wood |

– | – | (Campbell et al., 2017) |

| Turkey | Mersin Bay | Ocean | – | Trawling |

Bougainvillia muscus

Spirobranchus triqueter Hydroides sp. Serpula sp. Serpula vermicularis Order: Sabellida Phylum: Bryozoa Neopycnodonte cochlear Musculus subpictus Anomia ephippium Corbula gibba Sephia officinalis Diodora sp. Lepas anatifera Perforatus Galathea intermedia Ascidiella aspersa Phallusia mammillata Ciona intestinalis Styela sp. |

Hydrozoa Polychaeta Phylum: Bryozoa Bivalvia Cephalopoda Gastropoda Hexanauplia Malacostraca Ascidiacea |

Plastic debris | – | EPC (2%) PE (72%) PET (3%) Poly-E (1%) PP (12%) NY-6 (1%) PVC (1%) PS (1%) SAC (1%) PET/PP (1%) Unidentified (7%) |

(Gündoğdu et al., 2017) |

| Israel | Shefayim | Beach | 2014 | Not specified |

Cerithiopsis tenthrenois

Crisilla semistriata Arca noae Striarca lactea Gregariella cf. ehrenbergi Musculus subpictus Musculus costulatus Lithophaga Modiolus cf. barbatus Arcuatula senhousia Brachidontes pharaonis Septifer cumingii Mytilaster cf. minimus Pinctada imbricata radiata Ostrea edulis Dendostrea cf. folium Malleus regula Chama pacifica Sphenia binghami Cucurbitula cymbium Rocellaria dubia |

Gastropoda Bivalvia |

Buoy | Sea-based | – | (Ivkić et al., 2019) |

| Australia | – | Ocean | – | Trawling | Phylum: Bryozoa Lepas spp. Order: Isopoda Halobates sp. Phylum: Annelida |

Phylum: Bryozoa Phylum: Annelida Insecta Malacostraca Thecostraca |

Plastic fragments | – | PE (83%) PP (17%) |

(Reisser et al., 2014) |

| Mediterranean Sea | Ligurian sea | Ocean | 1997 | Floating objects were collected |

Arbacia lixula

Bowerbankia gracilis Callopora lineata Clytia hemisphaerica Cymodocea nodosa Doto sp. Electra posidoniae Eudendrium sp. Fiona pinnata Gonothyrea loveni Idotea metallica Laomedea angulata Lepas pectinata Membranipora membranacea Nereis falsa Obelia dichotoma Phtisica marina Spirobranchus polytrema |

Echinoidea Gymnolaemata Hydrozoa Gastropoda Malacostraca Thecostraca Polychaeta |

Plastic bag Hard plastic debris Styrofoam Bottles Wood Fishing gear |

– | – | (Aliani and Molcard, 2003) |

| Mediterranean Sea | Gulf of Pozzuoli | Ocean | 2019 | Trawling at different depths | – | Phylum: Bryozoa Phylum: Cnidaria Phylum: Porifera Phylum: Chordata Phylum: Arthropoda Phylum: Mollusca Phylum: Annelida |

Cotton Glass Metal Nylon Paper Plastic Pottery Concrete Rubber Synthetic textile Wood |

Land-based (83.6%) Sea-based (16.4%) |

– | (Crocetta et al., 2020) |

| USA | – | Beach | 2012-2017 | Large-scale landing on coastlines (no specific methodology) | 49 species of bryozoans | Stenolaemata Gymnolaemata |

Totes, crates or containers Vessels Buoys, floats Other items Post and beam wood Trees/logs Pontoon sections Misawa docks |

Land-based Sea-based |

– | (McCuller and Carlton, 2018) |

| Morocco | Mediterranean coast | Beach | 2022 | Whole beach survey |

Lepas pectinata

Perforatus Lepas anatifera Phylum: Bryozoa Class: Thecostraca Spirobranchus triqueter Neopycnodonte cochlear Hydroides sp Ophiothrix fragilis Eunicella verrucosa Myriapora truncuta |

Thecostraca Phylum: Bryozoa Polychaeta Bivalvia Ophiuroidea Octocorallia Gymnolaemata |

Bottles <2 L Bottles >2 L Food containers Plastic bags Plastic buoys Ropes Plastic tube Clothing, shoes Bottles and jars Other wood |

Land-based (93.3%) Sea-based (6.7%) |

– | (Mghili et al., 2022) |

Characteristics of methodologies and results of the 39 studies evaluated.

ABS-indicates acrylonitrile butadiene styrene; PC-indicates polycarbonate; PE-indicates polyethylene; LDPE-indicates low-density polyethylene; MDPE-indicates medium-density polyethylene; HDPE-indicates high-density polyethylene; PET-indicates polyethylene terephthalate; PMMA-indicates poly (methyl methacrylate); PP-indicates polypropylene; PTFE-indicates polytetrafluoroethylene; PS-indicates polystyrene; PVC-indicates polyvinyl chloride; PU-indicates polyurethane. Species in bold were identified as non-indigenous species or AIS.

1If organisms were not identified at species level, the lowest possible taxonomic classification was mentioned.

2If organisms were not identified at class level, the phylum was mentioned.

Figure 2

Geographic map indicating the marine litter colonization studies (red dots). The map was constructed using ArcGIS (version 10.7).

The studies consulted addressed multiple research questions involving the occurrence of colonized litter in diverse areas, as well as the transportation of colonized litter (rafting). Most studies surveyed stranded litter, although the focus of the studies differed depending on specific sources of contamination. For instance, Rech et al. (2018b) focused on understanding the contribution of mariculture areas on the release of rafting AIS in Europe, while Rech et al. (2018c) investigated the arrival of colonized litter on beaches of the Rapa Nui Island, a remote island in the South Pacific Ocean. Furthermore, De-la-Torre et al. (2021) highlighted that the Peruvian coast may act as a source of colonized marine litter rather than the arrival of rafts containing AIS. McCuller and Carlton (2018) focused on a very specific event (e.g., the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011) and its repercussion on transoceanic species dispersal on large-scale marine litter. On the other hand, Crocetta et al. (2020) investigated benthic marine litter composition and abundance of mega- and macrofauna by trawling at depths of 50 and 100 m. The number of studies focusing on benthic marine litter is reduced, while others combined approaches by investigating beaches, floating, and benthic marine litter (e.g., Subías-Baratau et al., 2022). Conducting multiple approaches allows researchers to understand important factors in the transport of floating marine litter, such as the role of biofouling on plastic sinking rates (Chen et al., 2019). While marine litter colonization remains less investigated than other dispersal pathways (García-Gómez et al., 2021), recent studies have provided multiple perspectives on the factors involved in biofouling colonization and dispersal. However, several challenges remain ahead.

As mentioned previously, 28 studies (71.8%) were conducted in coastal zones or beaches, while studies recovering fouled litter from the open ocean or sea are limited (11 studies, 28.2%) (Table 1). This is likely due to the ease and accessibility to coastal zones as also mentioned by Póvoa et al. (2021). Likewise, one study evaluated the state of colonization of submerged litter (Mantelatto et al., 2020), although submerged debris (generally dense materials) is unlikely to resurface and serve as AIS rafts. Nevertheless, submerged debris may be subject to abiotic influences (e.g., weathering conditions, water currents) and colonizing species than those experienced by floating debris.

Sampling methodologies have not been standardized to assess colonizing biota on beached litter. Seven studies (17.9%) chose to monitor the entire beach, from the tide line to the maximum limit of the beach (vegetation or trails) (e.g., Miralles et al., 2018; Rech et al., 2018a; Ibabe et al., 2020; De-la-Torre et al., 2021). This method (covering the entirety of the beach) allows recovering a greater amount of litter and obtaining a complete view of the abundance of litter per beach. However, this method may incur in sampling bias when the sampling length or quadrants dimensions are different across sampling locations, in addition to requiring more effort, as determined by Pizarro-Ortega et al. (2022). To this end, the resolution of sampling designs should be standardized and similar across sampling locations. Conversely, other studies (n = 5; 12.8%) followed the tidal lines in search of colonized litter (Rech et al., 2018c; Mantelatto et al., 2020; Póvoa et al., 2022; Subías-Baratau et al., 2022). With this method, it is possible to quickly assess the litter that has been in contact with the tides that are concentrated in the tide line. Regardless, focusing on the strandline or whole beach area may be indicators of incoming or accumulated colonized litter, respectively. Thus, studies should consider this interpretation to determine the methodology that better aligns with their objectives. Other studies ran transect- and quadrat-based sampling methods (n = 5; 12.8%) (Taylor and Tan, 2015; Gracia C. et al., 2018; Aytan et al., 2019). On several occasions, the sampling methodology was not specified (n = 9; 23.1%). It could be assumed that colonized litters were collected opportunistically, although important data, such as colonized litter density (e.g., colonized litters per total number of litter or beach area), is not obtained. The heterogeneity in the methodologies used to search for colonized litter makes the comparison between studies difficult. For this reason, it is necessary to reach a consensus regarding the methodology used for this purpose, as well as the reported data, as also mentioned by Póvoa et al. (2021). For example, very few studies reported the percentage of colonized litter with respect to the total number of litter found (Rech et al., 2018c; Póvoa et al., 2022). Also, no previous study reported the number of colonized (and non-colonized) marine litter per unit area.

A significant number of species have been reported, belonging to 31 taxonomic classes, as displayed in Table 1. While some authors focused on one or two relevant species (Gracia and Rangel-Buitrago, 2020; Cooke and Sumer, 2021), others report hundreds of species found as a result of more extensive sampling methodologies (Astudillo et al., 2009; Carlton et al., 2017). Some of the most frequent taxonomic classes among studies are Bivalvia (Phylum: Mollusca), Gastropoda (Phylum: Mollusca), Thecostraca (Phylum: Arthropoda), Malacostraca (Phylum: Arthropoda), Polychaeta (Phylum: Annelida), and Gymnolaemata (Phylum: Bryozoa). Most of the species in these classes are sessile or have a limited degree of mobility, while others, such as those of the class Malacostraca, have a higher degree of mobility. This suggests that, in terms of species transport, marine litter not only functions as a substrate for species proliferation but also as a potential hiding place for more mobile species. In a particular case, Subías-Baratau et al. (2022) reported the presence of egg capsules of a shark of the genus Scyliorhinus. This behavior would not only mean a possible dispersion of species, but also an impact on the survival of oviparous chondrichthyans. However, the dynamics between oviposition, dispersal and hatching of larger species require further investigation, as studies are limited (De-la-Torre et al., 2022c). It should be noted that biofilm-forming microbial communities that settle on the synthetic substrate in the first weeks in contact with seawater may influence macroinvertebrate assemblages. Diatoms and bacteria become attached to the surface of a substrate that is rich in protein, carbohydrates, and glycoproteins after being in contact with seawater; these organisms then secrete extracellular polymeric substances to become embedded (Müller et al., 2013). The proliferation of macroalgae and other organisms occurs later on (Kiessling et al., 2015). While this review focused on macroinvertebrates, the importance of the first biofilm-forming microbes to understanding complex macroinvertebrate assemblages on marine litter should be noted and further investigated.

Most of the studies reported native or cosmopolitan species (e.g., Lepas spp.) in their samples, or did not categorize them, while invasive species and their proportion with respect to the total species are reported in a few studies. For instance, in aquaculture areas of Italy and Portugal, Rech et al. (2018b) reported the presence of invasive species of the class Thecostraca [Amphibalanus amphitrite (Darwin, 1854), Austrominius modestus (Darwin, 1854), Balanus trigonus (Darwin, 1854) and Hesperibalanus fallax (Broch, 1927)], Polychaeta [Hydroides elegans (Haswell, 1883) and Hydroides sanctaecrucis (Krøyer, 1863)] and Bivalvia [Magallana angulata (Lamarck, 1819)]. Póvoa et al. (2022) found several species of anthozoans (Class: Anthozoa) classified as invasive [Tubastraea coccinea (Lesson, 1830), Tubastraea sp., and Tubastraea tagusensis (Wells, 1982)] mainly in polystyrene-based materials (e.g., buoys and expanded polystyrene) on Brazilian beaches. Likewise, the bivalve Saccostrea cuculatta (Born, 1778), and polychaete H. elegans in expanded polystyrene and plastic fragments, respectively. Although several studies recognize invasive species by comparing international databases (e.g., Global invasive species database, http://www.issg.org/database) and regional studies, considering the multiple species of various taxonomic levels, the list may be evolving. Regardless, it is almost impossible to determine the source of dispersal of non-native species that are already proliferating in foreign environments.

One of the main barriers in the study of invasive species is the identification of these at the species level as also mentioned by Póvoa et al. (2021). In multiple studies, organisms are identified at family, order, or class level (Gil and Pfaller, 2016; Carlton et al., 2017; De-la-Torre et al., 2021), which makes it difficult to determine potential invaders. However, several studies opted for the genetic identification of some potentially invasive species through DNA barcoding (Miralles et al., 2018; Rech et al., 2018a; Rech et al., 2018b; Rech et al., 2018c; Ibabe et al., 2020; Rech et al., 2021). For example, Rech et al. (2018a) identified species classified as invasive Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1793), Ostrea stentina (Payraudeau, 1826) (class: Bivalvia), A. modestus (class: Thecostraca), Serpula columbiana (Johnson, 1901), and Neodexiospira sp. (class: Polychaeta) through DNA barcoding. The main limitation of DNA barcoding is the availability of reference libraries for taxonomic identification of the genetic sequence (Hellberg et al., 2016). However, new studies are constantly contributing to filling the gaps in reference libraries (Leite et al., 2020). On the other hand, DNA barcoding is not always readily available to research groups and institutions worldwide, particularly in developing countries, such as Peru and Brazil. In this context, taxonomists or research groups must make efforts to consider taxonomic analyzes that help build barcoding libraries of invertebrates and make efforts to construct fruitful collaborations to gain access to genetic identification.

Types of colonized litter reported in these studies are generally diverse, including textiles, bottles, plastic containers and bags, processed wood, fishing gear (e.g., nets), and buoys, among others (e.g., Gracia C. et al., 2018; Mantelatto et al., 2020; Rumbold et al., 2020; De-la-Torre et al., 2021). However, the categorization of litter is often not standardized (Póvoa et al., 2021). For example, Rech et al. (2018a) classify most litter as “hard plastic”, “other plastics”, “foams”, and “non-plastic”, while Mantelatto et al. (2020) propose a more specific classification, including tires, plastic bottles, electric cables, Styrofoam, among others. Other studies report the predominance of only one or two types of colonized litter, mainly buoys and plastic bottles (e.g., Aytan et al., 2019; Cooke and Sumer, 2021), or they do not report it and concentrate on its chemical composition (e.g., Subías-Baratau et al., 2022). The divergence between the classifications used between studies generates complications when integrating the data reported in the literature to determine which substrates are widely preferred by organisms. For this reason, it is necessary to standardize the classification with remarkable specificity. Furthermore, substrate preference may also by influenced by litter type availability. In this sense, litter classification should also include a standard method for litter type (different substrate types) quantification.

The diversity of litter types found can be influenced by experimental design, sources of contamination, and sampling efforts (Rees and Pond, 1995; Velander and Mocogni, 1999). A temporary study carried out in a large coastal area contaminated by a variety of sources is likely to report a greater diversity of colonized litter than a shorter, more focused study. For instance, Carlton et al. (2017) carried out the most extensive study on the occurrence of colonized marine litter on the Pacific coast of the United States. In more than six years, 634 objects and litter from Japan of a great variety (wood, buoys, plastics, metals, ropes, boxes, and electronics) were reported. Secondly, Gracia and Rangel-Buitrago (2020) focused on reporting the occurrence of the invasive bivalve Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) in buoys found on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, while Astudillo et al. (2009) compared the communities found in buoys in use and detached. In both cases, only buoys are reported; however, these areas remain susceptible to the arrival of other types of colonized litter.

The origin of litter colonized by epibionts can be tracked in specific scenarios. For instance, in Italy and Portugal, it has been reported that 64% of the colonized litter originated from aquaculture activities (Rech et al., 2018b). Aquaculture items are easily recognizable while considering that the study by Rech et al. (2018b) was carried out in those areas. However, associating the occurrence of colonized litter with specific anthropic activities may be a rather difficult task on most occasions. For instance, while plastic bottles are generally assumed to originate from land (e.g., incorrectly discarded by beachgoers), studies suggest that a significant number of PET bottles are dumped by ships off shore (Ryan et al., 2019; Ryan, 2020; Ryan et al., 2021), but a definitive number cannot be attributed to either source.

A factor that plays an important role in the colonization process, although it is generally underestimated, is the polymeric composition of the litter (normally plastics). Experimental studies have previously shown that some invertebrate species, such as bryozoans, have a preference for plastics with multiple polymer compositions (Li et al., 2016; Pinochet et al., 2020; Póvoa et al., 2022). A total of 13 different polymers have been identified in the literature, including blends. However, in field studies, there is still great uncertainty regarding the preference of observed organisms for different types of polymers. Only five studies were found that identified the polymeric composition of plastic litter. De-la-Torre et al. (2021) tried to relate the organisms found at the taxonomic class level with the polymers or materials that make up the substrates they inhabit. However, their results are not enough to be conclusive. Similarly, Rech et al. (2021) identified the polymer from the floating plastic debris found. However, the number of litters analyzed was not sufficient to evaluate this factor as a predictor variable. Subías-Baratau et al. (2022) carried out a more exhaustive identification, including a greater number of litters analyzed and reported a greater variety of polymers than previous studies. The three studies agree that the two predominant types of polymers are polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP). This makes sense since these are the two types of polymers most produced and traded worldwide (PlasticsEurope, 2021). Other polymers found are polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which could be attributed to bottles and some textiles, polyamides (PA), which could originate in fishing nets, among others. One possible reason for the low use of polymeric identification techniques is the cost and scope of sophisticated equipment and analysis, such as Fourier Transform Infrared Radiation (FTIR) spectrometry, particularly in developing countries (Silva et al., 2018; Aragaw, 2021). However, more exhaustive monitoring of the polymers that transport marine organisms is necessary at a global level. Secondly, Cooke and Sumer (2021) reported the presence of Lepas pectinata (Spengler, 1793) in the neck of a plastic bottle. The particularity of this finding is that, after a contact angle analysis, the neck of the bottle presented higher hydrophilicity compared to the rest of the bottle. Although more in-depth studies are needed regarding the physicochemical characteristics of the colonized litter, the study by Cooke and Sumer (2021) preliminarily put into perspective the relevance of materials science aspects in this field of research.

The present review focused on the role of marine litter in the transportation of colonized floating marine litter (rafting), which could harbor invasive or potentially invasive species. Other anthropic sources of dispersal may include biofouling boat hulls and ballast water (Costello et al., 2022), as well as natural pathways. Natural dispersal pathways have been demonstrated on several occasions. For instance, non-native cnidarian [e.g., Rhopilema nomadica (Galil, 1990)] and fishes [e.g., Lagocephalus sceleratus (Gmelin, 1789), and Pterois miles (Bennett, 1828)] have been found in the Mediterranean Sea as a result of drifting and swimming pathways (Deidun et al., 2011; Coro et al., 2018; Galanidi et al., 2018). Comparing the multiple anthropic and natural dispersal pathways is a complicated task as these may occur simultaneously, although more attention has been given to biofouling and ballast water pathways (García-Gómez et al., 2021). This is likely due to the increase and exacerbation of biological invasions associated with anthropic activities, as well as the capacity of transoceanic dispersal (e.g., international maritime activity) (Encarnação et al., 2021). Attributing specific pathways to already triggered biological invasions is extremely difficult if active monitoring of the various anthropic and natural vectors is lacking. On the other hand, ecological research must support determining if non-native organisms are harmful invasive species for specific ecosystems. Whether a certain dispersal pathway is more or less harmful than others may be debatable. However, constant monitoring is required to understand species dispersal dynamics and elaborate control and conservation programs, including natural pathways.

4 Recommendations

Based on the results of this review and identified limitations, several recommendations are proposed:

-

In many cases, identifying organisms to the lowest taxonomical level by just applying morphological characteristics is insufficient, thus, it is recommended to carry out molecular analyzes of the predominant species that show traits of being an AIS. Considering the difficulty to access techniques, such as DNA barcoding, research groups are encouraged to seek collaborative projects with mutually beneficial objectives.

-

In light of the lack of a standard marine litter classification, the item categorization according to Fleet et al. (2021) is recommended. Additionally, digital approaches are required to facilitate data collection in the field. Further, the item categories indicated by Fleet et al. (2021) should be taken as standardized litter categories master list, while maintaining some flexibility for local-level litter peculiarities. A clear example is the great number of laminated candy wrappers, which are specific to cities like Lima, Peru. On the other hand, specific events that induce unusual and unprecedented sources of marine litter should also be taken into account. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be relevant to include an additional category referring to face masks or personal protective equipment (such as gloves and face shields).

-

The overall number or abundance of marine litter at each sampling site, regardless of their colonization status, should be taken as a reference frame. Thus, fouling litter surveys must report the percentage of fouled items with respect to the total number of litters at each sampling location.

-

Comprehensive studies should include species preference analyses based on the chemical characteristics of a substantial part of all the biofouled items. For instance, in the case of plastics, identifying the polymer type through FTIR or Raman spectroscopy is recommended, as well as the hydrophilicity of the material and surface microstructure.

5 Conclusions

The growing literature on floating marine litter have evidenced its indubitable ability to serve as a substrate for multiple organisms, possibly acting as a vehicle for species dispersal, including AIS. In the present review, an updated literature search was carried out focusing on field research reporting the occurrence of marine macro-biota colonizing or inhabiting marine litter. Results indicate that, from a geographic point of view, there is a lack of information on African and East Asian countries, as well as on the open ocean. Methodologies used to investigate colonized litter in coastal areas lack standardization, thus, making studies difficult to compare. Also, a consensus is needed regarding litter classification and unit expression, as well as combining litter classification with polymer identity. On the other hand, the difficult access to species identification through molecular analyzes and incomplete libraries are important barriers to precisely estimating the contribution of marine litter to AIS dispersal. Based on the main limitations identified in the present review, a list of recommendations was proposed.

Statements

Author contributions

GD-l-T: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MA and VR: Conceptualization, Methodology Investigation, Writing – original. AP and TW: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Validation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author is thankful to Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola for financial support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aliani S. Molcard A. (2003). Hitch-hiking on floating marine debris: macrobenthic species in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Hydrobiol2003 5031 503, 59–67. doi: 10.1023/B:HYDR.0000008480.95045.26

2

Ammendolia J. Saturno J. Bond A. L. O’Hanlon N. J. Masden E. A. James N. A. et al . (2022). Tracking the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic-related debris on wildlife using digital platforms. Sci. Total Environ.848, 157614. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2022.157614

3

Andrady A. L. (2017). The plastic in microplastics: A review. Mar. pollut. Bull.119, 12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.01.082

4

Andrady A. L. Neal M. A. (2009). Applications and societal benefits of plastics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc B. Biol. Sci.364, 1977–1984. doi: 10.1098/RSTB.2008.0304

5

Aragaw T. A. (2021). Microplastic pollution in African countries’ water systems: a review on findings, applied methods, characteristics, impacts, and managements. SN Appl. Sci.3, 629. doi: 10.1007/s42452-021-04619-z

6

Astudillo J. C. Bravo M. Dumont C. P. Thiel M. (2009). Detached aquaculture buoys in the SE pacific: potential dispersal vehicles for associated organisms. Aquat. Biol.5, 219–231. doi: 10.3354/ab00151

7

Aytan U. Sahin F. B. E. Karacan F. (2019). Beach litter on sarayköy beach (SE black sea): Density, composition, possible sources and associated organisms. Turkish J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.20, 137–145. doi: 10.4194/1303-2712-v20_2_06

8

Barnes D. K. A. (2002). Biodiversity: Invasions by marine life on plastic debris. Nature416, 808–809. doi: 10.1038/416808a

9

Barnes D. K. A. Fraser K. P. P. (2003). Rafting by five phyla on man-made flotsam in the southern ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.262, 289–291. doi: 10.3354/MEPS262289

10

Barnes D. K. A. Warren N. L. Webb K. Phalan B. Reid K. (2004). Polar pedunculate barnacles piggy-back on pycnogona, penguins, pinniped seals and plastics. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.284, 305–310. doi: 10.3354/MEPS284305

11

Battaglia P. Consoli P. Ammendolia G. D’Alessandro M. Bo M. Vicchio T. M. et al . (2019). Colonization of floats from submerged derelict fishing gears by four protected species of deep-sea corals and barnacles in the strait of Messina (central Mediterranean Sea). Mar. pollut. Bull.148, 61–65. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2019.07.073

12

Battisti C. Staffieri E. Poeta G. Sorace A. Luiselli L. Amori G. (2019). Interactions between anthropogenic litter and birds: A global review with a ‘black-list’ of species. Mar. pollut. Bull.138, 93–114. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.11.017

13

Breves A. Skinner L. F. (2014). First record of the vermetid petaloconchus varians (d’Orbigny1841 841) on floating marine debris at ilha grande, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev. Gestão Costeira Integr.14, 159–161. doi: 10.5894/RGCI457

14

Campbell M. L. King S. Heppenstall L. D. van Gool E. Martin R. Hewitt C. L. (2017). Aquaculture and urban marine structures facilitate native and non-indigenous species transfer through generation and accumulation of marine debris. Mar. pollut. Bull.123, 304–312. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2017.08.040

15

Carlton J. T. Chapman J. W. Geller J. B. Miller J. A. Carlton D. A. McCuller M. I. et al . (2017). Tsunami-driven rafting: Transoceanic species dispersal and implications for marine biogeography. Science347. doi: 10.1126/science.aao1498

16

Chassignet E. P. Xu X. Zavala-Romero O. (2021). Tracking marine litter with a global ocean model: Where does it go? Where Does It Come From? Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/FMARS.2021.667591/BIBTEX

17

Chen X. Xiong X. Jiang X. Shi H. Wu C. (2019). Sinking of floating plastic debris caused by biofilm development in a freshwater lake. Chemosphere222, 856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.015

18

Cooke A. Sumer H. (2021). Possible transoceanic rafting of lepas spp. on an unopened plastic bottle of Chinese origin washed ashore in Victoria, Australia. Asian J. Water Environ. pollut.18, 85–90. doi: 10.3233/AJW210011

19

Coro G. Vilas L. G. Magliozzi C. Ellenbroek A. Scarponi P. Pagano P. (2018). Forecasting the ongoing invasion of lagocephalus sceleratus in the Mediterranean Sea. Ecol. Modell.371, 37–49. doi: 10.1016/J.ECOLMODEL.2018.01.007

20

Costa L. L. Fanini L. Ben-Haddad M. Pinna M. Zalmon I. R. (2022). Marine litter impact on sandy beach fauna: A review to obtain an indication of where research should contribute more. Microplastics1, 554–571. doi: 10.3390/MICROPLASTICS1030039

21

Costello K. E. Lynch S. A. McAllen R. O’Riordan R. M. Culloty S. C. (2022). Assessing the potential for invasive species introductions and secondary spread using vessel movements in maritime ports. Mar. pollut. Bull.177, 113496. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2022.113496

22

Crocetta F. Riginella E. Lezzi M. Tanduo V. Balestrieri L. Rizzo L. (2020). Bottom-trawl catch composition in a highly polluted coastal area reveals multifaceted native biodiversity and complex communities of fouling organisms on litter discharge. Mar. Environ. Res.155, 104875. doi: 10.1016/J.MARENVRES.2020.104875

23

Deidun A. Arrigo S. Piraino S. (2011). The westernmost record of rhopilema nomadica (Galil1991 990) in the Mediterranean – off the Maltese islands. Aquat. Invasions6, 99–103. doi: 10.3391/ai.2011.6.S1.023

24

De-la-Torre G. E. Dioses-Salinas D. C. Pérez-Baca B. L. Millones Cumpa L. A. Pizarro-Ortega C. I. Torres F. G. et al . (2021). Marine macroinvertebrates inhabiting plastic litter in Peru. Mar. pollut. Bull.167, 112296. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112296

25

De-la-Torre G. E. Pizarro-Ortega C. I. Dioses-Salinas D. C. Castro Loayza J. Smith Sanchez J. Meza-Chuquizuta C. et al . (2022a). Are we underestimating floating microplastic pollution? a quantitative analysis of two sampling methodologies. Mar. pollut. Bull.178, 113592. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2022.113592

26

De-la-Torre G. E. Pizarro-Ortega C. I. Dioses-Salinas D. C. Rakib M. R. J. Ramos W. Pretell V. et al . (2022b). First record of plastiglomerates, pyroplastics, and plasticrusts in south America. Sci. Total Environ.833, 155179. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2022.155179

27

De-la-Torre G. E. Valderrama-Herrera M. Urizar Garfias Reyes D. F. Walker T. R. (2022c). Can oviposition on marine litter pose a threat to marine fishes? Mar. pollut. Bull.185, 114375. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114375

28

Encarnação J. Teodósio M. A. Morais P. (2021). Citizen science and biological invasions: A review. Front. Environ. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/FENVS.2020.602980/BIBTEX

29

Faria L. C. Kitahara M. V. (2020). Invasive corals hitchhiking in the southwestern Atlantic. Ecology101, e03066. doi: 10.1002/ECY.3066

30

Fleet D. Vlachogianni T. Hanke G. (2021). A JointList of litter categories for marine macrolitter monitoring. Luxembourg. doi: 10.2760/127473

31

Fukuoka T. Sakane F. Kinoshita C. Sato K. Mizukawa K. Takada H. (2022). Covid-19-derived plastic debris contaminating marine ecosystem: Alert from a sea turtle. Mar. pollut. Bull.175, 113389. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2022.113389

32

Galanidi M. Zenetos A. Bacher S. (2018). Assessing the socio-economic impacts of priority marine invasive fishes in the Mediterranean with the newly proposed SEICAT methodology. Mediterr. Mar. Sci.19, 107–123. doi: 10.12681/mms.15940

33

García-Gómez J. C. Garrigós M. Garrigós J. (2021). Plastic as a vector of dispersion for marine species with invasive potential. A. Rev. Front. Ecol. Evol.9. doi: 10.3389/FEVO.2021.629756/BIBTEX

34

Garcia-Vazquez E. Cani A. Diem A. Ferreira C. Geldhof R. Marquez L. et al . (2018). Leave no traces – beached marine litter shelters both invasive and native species. Mar. pollut. Bull.131, 314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.04.037

35

Gil M. A. Pfaller J. B. (2016). Oceanic barnacles act as foundation species on plastic debris: implications for marine dispersal. Sci. Rep.6, 19987. doi: 10.1038/srep19987

36

Goldstein M. C. Carson H. S. Eriksen M. (2014). Relationship of diversity and habitat area in north pacific plastic-associated rafting communities. Mar. Biol.161, 1441–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2432-8

37

Gong M. Yang G. Zhuang L. Zeng E. Y. (2019). Microbial biofilm formation and community structure on low-density polyethylene microparticles in lake water microcosms. Environ. pollut.252, 94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.090

38

Gracia C. A. Rangel-Buitrago N. Flórez P. (2018). Beach litter and woody-debris colonizers on the atlantico department Caribbean coastline, Colombia. Mar. pollut. Bull.128, 185–196. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2018.01.017

39

Gracia A. A. Rangel-Buitrago N. (2020). The invasive species perna viridis (Linnaeus1751 758 - bivalvia: Mytilidae) on artificial substrates: A baseline assessment for the Colombian Caribbean Sea. Mar. pollut. Bull.152, 110926. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.110926

40

Gündoğdu S. Çevik C. Karaca S. (2017). Fouling assemblage of benthic plastic debris collected from mersin bay, NE levantine coast of Turkey. Mar. pollut. Bull.124, 147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.07.023

41

Haarr M. L. Falk-Andersson J. Fabres J. (2022). Global marine litter research2012, 015–2020: Geographical and methodological trends. Sci. Total Environ.820, 153162. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2022.153162

42

Hahladakis J. N. Velis C. A. Weber R. Iacovidou E. Purnell P. (2018). An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Hazard. Mater.344, 179–199. doi: 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2017.10.014

43

Hänfling B. Edwards F. Gherardi F. (2011). Invasive alien Crustacea: dispersal, establishment, impact and control. BioControl56, 573–595. doi: 10.1007/S10526-011-9380-8

44

Hellberg R. S. Pollack S. J. Hanner R. H. (2016). “Seafood species identification using DNA sequencing,” in Seafood authenticity and traceability: A DNA-based pespective. Eds. NaaumA. M.HannerR. H. (London, UK: Academic Press), 113–132. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801592-6.00006-1.

45

Harayashiki C. A. Y. Ertas A. Castro I. B. (2021). Anthropogenic litter composition and distribution along a chemical contamination gradient at Santos Estuarine System—Brazil . Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci.46, 101902. doi: 10.1016/J.RSMA.2021.101902

46

Hoeksema B. W. Roos P. J. Cadée G. C. (2012). Trans-Atlantic rafting by the brooding reef coral favia fragum on man-made flotsam. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.445, 209–218. doi: 10.3354/MEPS09460

47

Ibabe A. Rayón F. Martinez J. L. Garcia-Vazquez E. (2020). Environmental DNA from plastic and textile marine litter detects exotic and nuisance species nearby ports. PloS One15, e0228811. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0228811

48

Ivkić A. Steger J. Galil B. S. Albano P. G. (2019). The potential of large rafting objects to spread lessepsian invaders: the case of a detached buoy. Biol. Invasions21, 1887–1893. doi: 10.1007/s10530-019-01972-4

49

Kiessling T. Gutow L. Thiel M. (2015). Marine litter as habitat and dispersal vector, in: Marine anthropogenic litter. Springer Int. Publishing, 141–181. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-16510-3_6

50

Koh L. P. Kettle C. J. Sheil D. Lee T. M. Giam X. Gibson L. et al . (2013). “Biodiversity state and trends in southeast Asia,” in Encyclopedia of biodiversity: Second edition. Ed. LevinS. A. (Academic Press: London, UK), 509–527. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384719-5.00357-9.

51

Leite B. R. Vieira P. E. Teixeira M. A. L. Lobo-Arteaga J. Hollatz C. Borges L. M. S. et al . (2020). Gap-analysis and annotated reference library for supporting macroinvertebrate metabarcoding in Atlantic Iberia. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci.36, 101307. doi: 10.1016/J.RSMA.2020.101307

52

Li H. X. Orihuela B. Zhu M. Rittschof D. (2016). Recyclable plastics as substrata for settlement and growth of bryozoans bugula neritina and barnacles amphibalanus amphitrite. Environ. pollut.218, 973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.08.047

53

Luna-Jorquera G. Thiel M. Portflitt-Toro M. Dewitte B. (2019). Marine protected areas invaded by floating anthropogenic litter: An example from the south pacific. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst.29, 245–259. doi: 10.1002/AQC.3095

54

Maes C. Blanke B. (2015). Tracking the origins of plastic debris across the coral Sea: A case study from the ouvéa island, new Caledonia. Mar. pollut. Bull.97, 160–168. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2015.06.022

55

Mantelatto M. C. Póvoa A. A. Skinner L. F. Araujo F. V. Creed J. C. (2020). Marine litter and wood debris as habitat and vector for the range expansion of invasive corals (Tubastraea spp.). Mar. pollut. Bull.160, 111659. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111659

56

Marques R. C. Breves A. (2014). First record of pinctada imbricata Röding1791 798 (Bivalvia: Pteroidea) attached to a rafting item: a potentially invasive species on the Uruguayan coast. Mar. Biodivers.45, 333–337. doi: 10.1007/S12526-014-0258-8

57

McCuller M. I. Carlton J. T. (2018). Transoceanic rafting of bryozoa (Cyclostomata, cheilostomata, and ctenostomata) across the north pacific ocean on Japanese tsunami marine debris. Aquat. Invasions13, 137–162. doi: 10.3391/ai.2018.13.1.11

58

Mghili B. De-la-Torre G. E. Analla M. Aksissou M. (2022). Marine macroinvertebrates fouled in marine anthropogenic litter in the Moroccan Mediterranean. Mar. pollut. Bull.185, 114266. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2022.114266

59

Mihai F. C. Gündogdu S. Markley L. A. Olivelli A. Khan F. R. Gwinnett C. et al . (2021). Plastic pollution, waste management issues, and circular economy opportunities in rural communities. Sustain14, 20. doi: 10.3390/SU14010020

60

Miralles L. Gomez-Agenjo M. Rayon-Viña F. Gyraitė G. Garcia-Vazquez E. (2018). Alert calling in port areas: Marine litter as possible secondary dispersal vector for hitchhiking invasive species. J. Nat. Conserv.42, 12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2018.01.005

61

Müller W. E. G. Wang X. Proksch P. Perry C. C. Osinga R. Gardères J. et al . (2013). Principles of biofouling protection in marine sponges: A model for the design of novel biomimetic and bio-inspired coatings in the marine environment? Mar. Biotechnol.15, 375–398. doi: 10.1007/S10126-013-9497-0

62

Pinochet J. Urbina M. A. Lagos M. E. (2020). Marine invertebrate larvae love plastics: Habitat selection and settlement on artificial substrates. Environ. pollut.257, 113571. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113571

63

Pizarro-Ortega C. I. Dioses-Salinas D. C. Fernández Severini M. D. López A. D. F. Rimondino G. N. Benson N. U. et al . (2022). Degradation of plastics associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Mar. pollut. Bull.176, 113474. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2022.113474

64

PlasticsEurope (2021). “Plastics - the facts 2021,” in An analysis of European plastics production, demand and waste data.

65

Poeta G. Staffieri E. Acosta A. T. R. Battisti C. (2017). Ecological effects of anthropogenic litter on marine mammals: A global review with a “black-list” of impacted taxa. Hystrix28, 265–271. doi: 10.4404/hystrix-00003-2017

66

Póvoa A. A. de Araújo F. V. Skinner L. F. (2022). Macroorganisms fouled in marine anthropogenic litter (rafting) arround a tropical bay in the southwest Atlantic. Mar. pollut. Bull.175, 113347. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2022.113347

67

Póvoa A. A. Skinner L. F. de Araújo F. V. (2021). Fouling organisms in marine litter (rafting on abiogenic substrates): A global review of literature. Mar. pollut. Bull.166, 112189. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2021.112189

68

Prata J. C. Silva A. L. P. Walker T. R. Duarte A. C. Rocha-Santos T. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic repercussions on the use and management of plastics. Environ. Sci. Technol.54, 7760–7765. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02178

69

Provencher J. F. Au S. Y. Horn D. Mallory M. L. Walker T. R. Kurek J. et al . (2022). “Animals and microplastics ingestion, transport, breakdown, and trophic transfer,” in Polluting textiles. Eds. WeisJ. S.De FalcoF.CoccaM., (London, UK) 30.

70

Rech S. Borrell Y. García-Vazquez E. (2016). Marine litter as a vector for non-native species: What we need to know. Mar. pollut. Bull.113, 40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.032

71

Rech S. Borrell Pichs Y. J. García-Vazquez E. (2018a). Anthropogenic marine litter composition in coastal areas may be a predictor of potentially invasive rafting fauna. PloS One13, e0191859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191859

72

Rech S. Gusmao J. B. Kiessling T. Hidalgo-Ruz V. Meerhoff E. Gatta-Rosemary M. et al . (2021). A desert in the ocean – depauperate fouling communities on marine litter in the hyper-oligotrophic south pacific subtropical gyre. Sci. Total Environ.759, 143545. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2020.143545

73

Rech S. Salmina S. Borrell Pichs Y. J. García-Vazquez E. (2018b). Dispersal of alien invasive species on anthropogenic litter from European mariculture areas. Mar. pollut. Bull.131, 10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.03.038

74

Rech S. Thiel M. Borrell Pichs Y. J. García-Vazquez E. (2018c). Travelling light: Fouling biota on macroplastics arriving on beaches of remote rapa nui (Easter island) in the south pacific subtropical gyre. Mar. pollut. Bull.137, 119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.10.015

75

Rees G. Pond K. (1995). Marine litter monitoring programmes–a review of methods with special reference to national surveys. Mar. pollut. Bull.30, 103–108. doi: 10.1016/0025-326X(94)00192-C

76

Reisser J. Shaw J. Hallegraeff G. Proietti M. Barnes D. K. A. Thums M. et al . (2014). Millimeter-sized marine plastics: A new pelagic habitat for microorganisms and invertebrates. PloS One9, e100289. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0100289

77

Ribeiro V. V. Harayashiki C.A.Y. LastNameErtaş A. Castro Í.B. (2021). Anthropogenic litter composition and distribution along a chemical contamination gradient at Santos Estuarine System—Brazil. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci.46, 101902. doi: 10.1016/J.RSMA.2021.101902

78

Rumbold C. E. García G. O. Seco Pon J. P. (2020). Fouling assemblage of marine debris collected in a temperate south-western Atlantic coastal lagoon: A first report. Mar. pollut. Bull.154, 111103. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2020.111103

79

Ryan P. G. (2020). Land or sea? what bottles tell us about the origins of beach litter in Kenya. Waste Manage.116, 49–57. doi: 10.1016/J.WASMAN.2020.07.044

80

Ryan P. G. Dilley B. J. Ronconi R. A. Connan M. (2019). Rapid increase in Asian bottles in the south Atlantic ocean indicates major debris inputs from ships. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.116, 20892–20897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1909816116

81

Ryan P. G. Weideman E. A. Perold V. Hofmeyr G. Connan M. (2021). Message in a bottle: Assessing the sources and origins of beach litter to tackle marine pollution. Environ. pollut.288, 117729. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2021.117729

82

Santillán L. Saldaña-Serrano M. De-la-Torre G. E. (2020). First record of microplastics in the endangered marine otter (Lontra felina). Mastozool. Neotrop.27, 211–215. doi: 10.31687/saremMN.20.27.1.0.12

83

Shabani F. Nasrolahi A. Thiel M. (2019). Assemblage of encrusting organisms on floating anthropogenic debris along the northern coast of the Persian gulf. Environ. pollut.254, 112979. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.112979

84

Silva A. B. Bastos A. S. Justino C. I. L. da Costa J. P. Duarte A. C. Rocha-Santos T. A. P. (2018). Microplastics in the environment: Challenges in analytical chemistry - a review. Anal. Chim. Acta1017, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.02.043

85

Staffieri E. de Lucia G. A. Camedda A. Poeta G. Battisti C. (2019). Pressure and impact of anthropogenic litter on marine and estuarine reptiles: an updated “blacklist” highlighting gaps of evidence. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res.26, 1238–1249. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3616-4

86

Subías-Baratau A. Sanchez-Vidal A. Di Martino E. Figuerola B. (2022). Marine biofouling organisms on beached, buoyant and benthic plastic debris in the Catalan Sea. Mar. pollut. Bull.175, 113405. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2022.113405

87

Taylor P. D. Tan S. H. A. (2015). Cheilostome bryozoa from penang and langkawi, Malaysia. Eur. J. Taxon2015, 1–34. doi: 10.5852/EJT.2015.149

88

Thiel M. Gutow L. (2005). The ecology of rafting in the marine environment. II. the rafting organisms and commnity. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev.43, 279–418.

89

Thiel M. Lorca B. B. Bravo L. Hinojosa I. A. Meneses H. Z. (2021). Daily accumulation rates of marine litter on the shores of rapa nui (Easter island) in the south pacific ocean. Mar. pollut. Bull.169, 112535. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2021.112535

90

Torres F. G. De-la-Torre G. E. (2021). Historical microplastic records in marine sediments: Current progress and methodological evaluation. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci.46, 101868. doi: 10.1016/J.RSMA.2021.101868

91

Tuladhar R. Yin S. (2019). “Sustainability of using recycled plastic fiber in concrete,” in Use of recycled plastics in eco-efficient concrete. Eds. Pacheco-TorgalF.KhatibJ.ColageloF.TuladharR. (Duxford, UK: Woodhead Publishing), 441–460. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102676-2.00021-9.

92

Tutman P. Kapiris K. Kirinčić M. Pallaoro A. (2017). Floating marine litter as a raft for drifting voyages for planes minutus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae) and liocarcinus navigator (Crustacea: Decapoda: Polybiidae). Mar. pollut. Bull.120, 217–221. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOLBUL.2017.04.063

93

Velander K. Mocogni M. (1999). Beach litter sampling strategies: is there a ‘Best’ method? Mar. pollut. Bull.38, 1134–1140. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00143-5

94

Węsławski J. M. Kotwicki L. (2018). Macro-plastic litter, a new vector for boreal species dispersal on Svalbard. Polish Polar Res.39, 165–174. doi: 10.24425/118743

95

Walker T. R. (2018). Drowning in debris: Solutions for a global pervasive marine pollution problem. Mar. pollut. Bull.126, 338. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.11.039

96

Walker T. R. Adebambo O. De Aguila Feijoo M. C. Elhaimer E. Hossain T. Edwards S. J. et al . (2019). “Chapter 27 - environmental effects of marine transportation,” in World seas: An environmental evaluation (Second edition) volume III: Ecological issues and environmental impacts. Ed. SheppardC. (London, UK: Elsevier B.V), 505–530. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805052-1.00030-9.

97

Wichmann C.-S. Fischer D. Geiger S. M. Honorato-Zimmer D. Knickmeier K. Kruse K. et al . (2022). Promoting pro-environmental behavior through citizen science? a case study with Chilean schoolchildren on marine plastic pollution. Mar. Policy141, 105035. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOL.2022.105035

98

Wright R. J. Langille M. G. Walker T. R. (2021). Food or just a free ride? a meta-analysis reveals the global diversity of the plastisphere. ISME J.15 (3), 789–806. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-00814-9

Summary

Keywords

flotsam, colonization, invasive, dispersal, marine litter, rafting

Citation

De-la-Torre GE, Romero Arribasplata MB, Lucas Roman VA, Póvoa AA and Walker TR (2023) Marine litter colonization: Methodological challenges and recommendations. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1070575. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1070575

Received

15 October 2022

Accepted

25 January 2023

Published

02 February 2023

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Roger C. Prince, Stonybrook Apiary, United States

Reviewed by

Lucia Fanini, University of Salento, Italy; Giuseppe Suaria, National Research Council (CNR), Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 De-la-Torre, Romero Arribasplata, Lucas Roman, Póvoa and Walker.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gabriel Enrique De-la-Torre, gabriel.delatorre@usil.pe

This article was submitted to Marine Pollution, a section of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.