Abstract

Chile is amidst an unprecedented legal and institutional change since the restoration of democracy at the end of the 80’s, which is expected to affect fisheries governance. A global lead in marine resource landings, Chile implemented significant fisheries management reforms in the past decade. Yet, Chilean fisheries still face sustainability challenges. In this paper we reflect on the results of a survey carried out in 2019-2020 with key informants aimed to identify fisheries policy reform priorities in country. Addressing Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing; Developing a priority national research agenda to improve fisheries management in Chile; Addressing the lack of legitimacy of the fisheries law; Developing a new national fisheries policy; and Update the Artisanal Fisheries Registry were identified as priority topics by respondents.

1 Introduction

In a declaration made on August 2022, the Chilean President Gabriel Boric Font gave “extreme urgency” to the bill, that was initially presented on January 19, 2016, that declares the nullity of the current Fisheries Law, which was delegitimized due to the court’s conviction, after 9 years since, a former senator and a former Member of Parliament for receiving bribes from a major fishing company (El Mostrador, 2022a) during the development of the law. The government also announced that a Bill for a New Fisheries Law will be presented between April and May 2023. This process should start in September 22 with debates in a pre-legislative work (El Mostrador, 2022b). All these processes are very relevant for ocean conservation and fisheries sustainability as Chile is one of the leading producers and exporters of marine resources in the world (FAO, 2022). In 2019, fisheries sector landings amounted to 2 million tons, 49 percent of which were caught by the artisanal sector (SERNAPESCA, 2019). Anchoveta, Jack mackerel, Araucanian herring, Chub mackerel, Jumbo flying squid, and Chilean hake are among the most important resources in terms of catch volume (SUBPESCA, 2020a).

In recent years, Chile has implemented significant fisheries regulation and management reforms, including updating its fisheries legislation with the implementation of a polycentric governance model (Gelcich, 2014) that incorporates co-management mechanisms covering the most important fisheries through Management Committees1 (MC) and Technical Scientific Committees and the subsequent modernization law (N° 21.132, 2019) of the governmental fisheries control agency SERNAPESCA (National Fisheries and Aquaculture Service). By 2019 Chile took a step forward in terms of transparency by uploading satellite vessel information to the Global Fishing Watch platform2, and has considerably increased the surveillance efforts at the landing sites. These and other developments allowed some industrial fisheries, such as Southern hake and Jack mackerel, to obtain MSC certification3. The 2020 accountability paper of the Undersecretariat for Fisheries and Aquaculture (SUBPESCA as per its acronym in Spanish) reported improvements in the stock health of Anchoveta fisheries (from Valparaíso to Los Lagos), Jack mackerel (from Arica and Parinacota to Los Lagos), Chilean seabass (from Arica and Parinacota to -47° SL) and Chilean seabass (47°-57° SL) (SUBPESCA, 2021). Despite this, the SUBPESCA, 2021 report shows that, out of the 27 national fisheries managed with biological reference points, 1 was underexploited, 12 were fully exploited, 8 were overexploited, and 6 were depleted or collapsed. These findings indicate that, Chilean fisheries still face important sustainability challenges.

This document presents an analysis of the results of a 2020 survey to key stakeholders to identify policy improvement priorities related to the fisheries sector. The aim of the survey was to understand the stakeholders’ points of view, to contribute to the improvement processes in public policy, governance, and fisheries management by identifying priorities and solutions. After what can be considered a political impasse in Chilean politics since the so called “social explosion” in October 2019 and the follow-on constitutional process coupled with the COVID pandemic, we consider the results of this 2020 study are still relevant for the institutional process going forward as the policy focus harks back to legal reform affecting fisheries governance.

2 Methodology

This study builds upon a consultation process carried out with key fisheries stakeholders of Chile, specifically focused on gathering their opinion on public policy improvement priorities to advance sustainability in Chilean fisheries. The study also aimed to identify the main issues along with the main possible improvement measures for the different prioritized topic. Data gathering was carried out in three stages.

During the first stage, a literature review was conducted in 2019 to identify recurrent topics pointed to in the literature as policy improvement areas for fisheries management in Chile. A total of 16 topics were identified in peer-reviewed journals, gray literature and journalistic reports written by fisheries specialists. The topics identified were (1) Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing; (2) Integration of an economic and social perspective in fisheries research and management; (3) Update of the Artisanal fisheries registry (RPA); (4) Development of a priority national research agenda to improve fisheries management in Chile; (5) Legitimacy of the current fisheries law; (6) Participative assessment of the fisheries management systems effectiveness; (7) Development of a new national fisheries policy; (8) Use of fishing gear which damages coastal habitats within the first five marine miles; (9) Consumption of seafood from Chile in order to guarantee food security in the country; (10) Incentives to the participation of professionals in the scientific technical committees (CCT), (11) Economic resources for the operation of management committees; (12) Transfer of tradable fishing licenses among sectors; (13) Creation of the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture; (14) Representativeness of women in the consultation and management decision making bodies; (15) Indigenous people’s rights on fishing resources; and (16) Structure of the Fisheries Promotion Institute’s governing board (IFOP) (Table 1).

Table 1

Topics considered in the consultation process.

In a subsequent stage, an online survey4 (Supplementary Material 1) was carried out comprising of open-ended and closed-ended questions divided into three sections. The first section sought to collect general information. The second section was composed by closed-ended questions and allowed each informant to determine the relevance of each of the 16 previously identified topics using the Likert scale (from “not relevant” to “very relevant”) and also included a space to propose additional topics. Finally, the third section required each respondent to choose the most urgent topic, as well as the second and third most urgent topics. Respondents were also asked to explain the issues derived from each topic and to propose specific actions to solve them.

The online survey was distributed to the largest possible number of fishery experts and stakeholders through a snowball sampling strategy. A total of 152 responses were collected from key informants from the artisanal sector, academia, government officials, industrial sector professionals, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and non-governmental organizations (NGO)s. The responses were collected between February 4 and April 7, 2020.

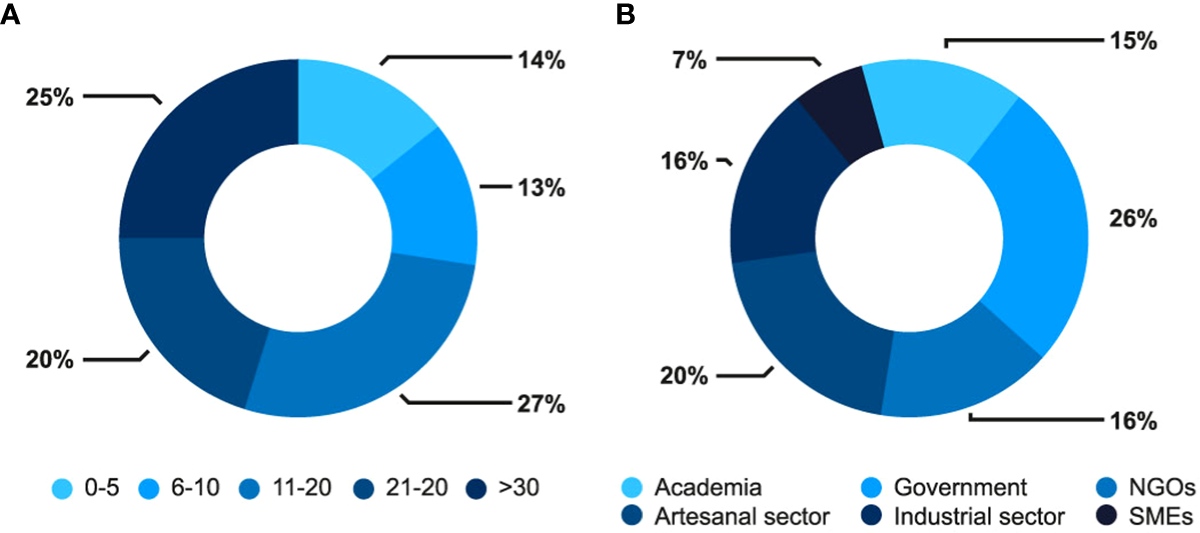

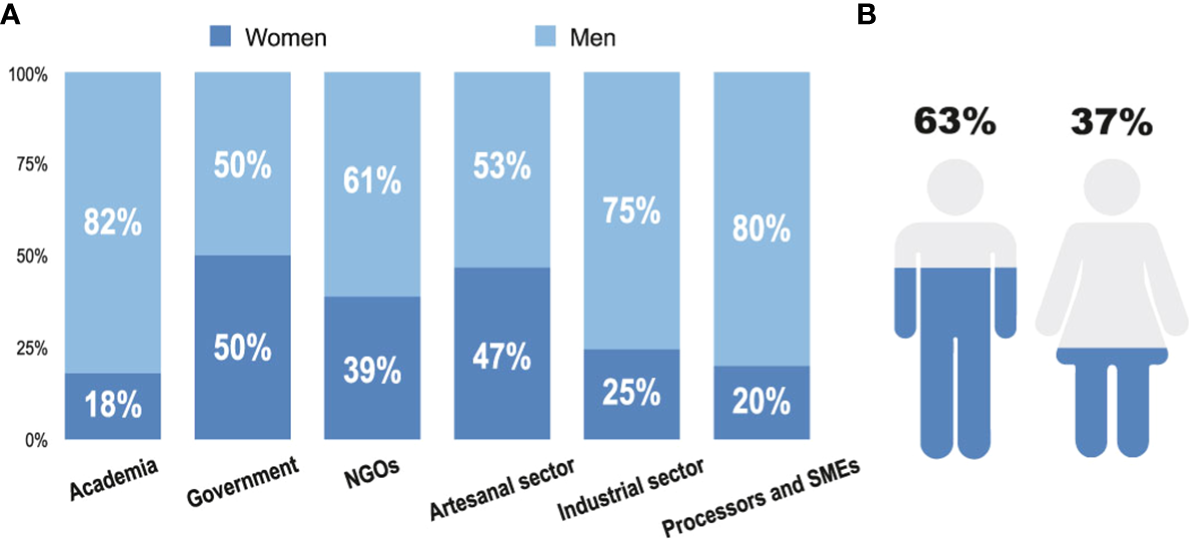

The third stage of the study focused on analyzing the content of the surveys. The respondents were classified by sector and by years of experience (Figure 1), as well as by gender (Figure 2). The relevance given by respondents to each topic was quantified. The relevance level of each topic was considered as the weighted average of the answers given by each respondent. Each respondent had the opportunity to rate each topic by assigning a score. The topics considered “not relevant” were given a “0” score, topics “slightly relevant” scored “1”, “regular” topics scored “2”, “relevant” topics scored “3” and topics considered “very relevant” were given the score of “4”. The topics with a weighted average between 4.00 and 3.01 were considered “very relevant”, those scoring between 3.00 and 2.01 were considered “relevant”, scores between 2.00 and 1.01 were considered “regular” and those between 1.00 and 0.01 were considered “slightly relevant”.

Figure 1

(A) Respondents by years of experience in the fisheries industry and (B) Respondents by sector.

Figure 2

(A) Respondents by gender according to sector and (B) total number of people surveyed.

Further to the above, the level of urgency to address to the topics was quantified, assigning a score of three to the most urgent topics, and a score of two and one to the second and third most urgent topics respectively. In this way, the study defined the priority topics that, according to the respondents, are the most urgent to be addressed. Finally, using the information provided by the respondents on the issues and possible solutions, the study described the five most urgent topics to be addressed in order to improve fisheries management in Chile.

3 Results

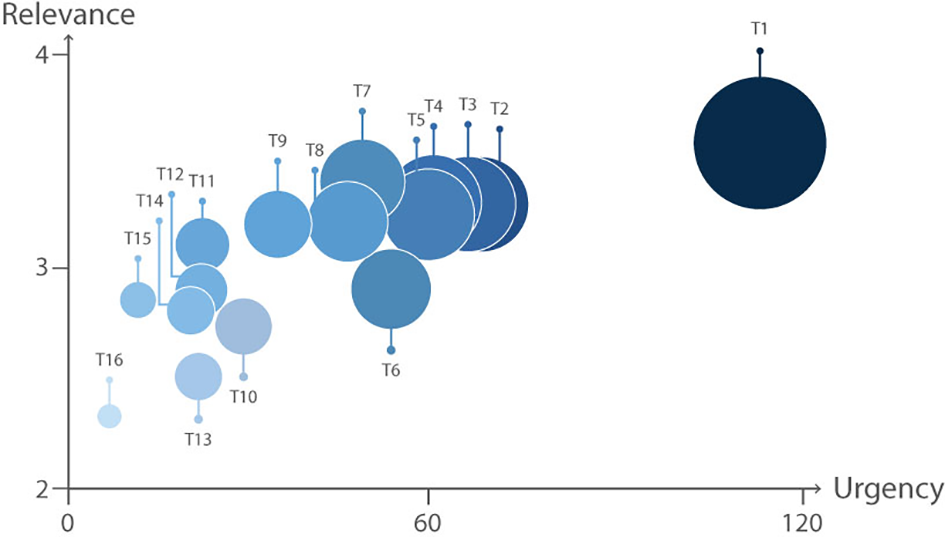

“Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing” was by far the most urgent issue to be addressed, scoring 120 points (Table 2; Figure 3). This was followed in second and third places by “developing a priority national research agenda to improve fisheries management in Chile” and “legitimacy of the current fisheries law,” scoring 71 and 69 points, respectively. Ranked in fourth and fifth places, with 63 and 62 points, respectively, were “developing a new national fisheries policy” and “updating the Artisanal Fisheries Registry (RPA by its acronym in Spanish)”. Further to the 16 improvement areas initially identified in the first stage (literature review) and scored for relevance and urgency by all 152 respondents, two new improvement areas were identified by 27 respondents, mainly from the NGO sector. Specifically, the development of an ecosystem approach and climate change adaptation within the fisheries5. Yet, the analysis below focuses only on the five top priority improvements areas for policy reform. For details on the distribution of priority improvement areas per respondent’s sector see Figure 4.

Table 2

| Issue | Relevance | Urgency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing | Very relevant (3.60) | 120 |

| T2 | Development of a priority national research agenda to improve fisheries management in Chile | Very relevant (3.32) | 71 |

| T3 | Legitimacy of the current fisheries law | Very relevant (3.32) | 69 |

| T4 | Development of a new national fisheries policy | Very relevant (3.33) | 63 |

| T5 | Update of the Artisanal Fisheries Registry (RPA) | Very relevant (3.27) | 62 |

| T6 | Creation of the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture | Relevant (2.94) | 56 |

| T7 | Integration of economic and social perspectives in fisheries research and management | Very relevant (3.41) | 51 |

| T8 | Participative assessment of the fisheries management systems effectiveness | Very relevant (3.23) | 48 |

| T9 | Consumption of seafood from Chile in order to guarantee food security in the country | Very relevant (3.22) | 37 |

| T10 | Representation of women in the consultation and management decision-making bodies | Relevant (2.75) | 30 |

| T11 | Use of fishing gear that damages coastal habitats within the first five marine miles | Very relevant (3.13) | 23 |

| T12 | Economic resources for the operation of management committees | Relevant (2.92) | 23 |

| T13 | Indigenous peoples’ rights on fishing resources | Relevant (2.52) | 23 |

| T14 | Transfer of tradable fishing licenses among sectors | Relevant (2.83) | 21 |

| T15 | Incentives for the participation of professionals in the scientific technical committees (CCT) | Relevant (2.88) | 12 |

| T16 | Structure of the Fisheries Promotion Institute’s governing board (IFOP) | Relevant (2.34) | 7 |

Relevance and urgency score of the issues proposed in the survey.

Figure 3

Topics by relevance and urgency level. Relevance: “Very relevant”: [4.00;3.00> and “relevant”: [3.00:2.00>. Urgency is measured as the score assigned by respondents surveyed. Circle diameter = relevance x urgency. The topics are provided in Table 2.

Figure 4

The top four improvement priorities in fisheries policies identified per respondent’s sector. The artisanal sector has five improvement priorities because the last two priorities were tied in terms of scoring points. The topics are provided in Table 2.

3.1 Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing

Most respondents chose IUU fishing as the most urgent issue to be addressed in the Chilean fisheries sector. In fact, it was ranked the most urgent issue by government officials, the industrial sector and academia. In such regard, a law was enacted in January 2019 to modernize and strengthen SERNAPESCA.

Despite this law being relatively new, respondents were able to identify certain structural problems and possible solutions to tackle problems associated with IUU fishing. Respondents pointed to structural gaps such as the lack of human resources (HR), technology, and budget available for SERNAPESCA to perform monitoring, control, and surveillance (MCS) operations. Furthermore, some respondents stated that a main problem that undermines the credibility of the control system itself is the lack of trust in the fishery industry data collection. According to respondents, in addition to enhancing data-collection systems and investing more in MCS resources (e.g., infrastructure, staff), the creation an official baseline on IUU fishing in Chile was proposed in order to quantify illegal fishing, identify hot spots, and rebuild catches for every fishery. This exercise would reduce uncertainty of stock assessment models and the associated management measures. Additionally, these measures would allow stakeholders to effectively integrate IUU fishing in management plans (MP), setting specific goals and deadlines to solve this problem and to implement strategies to tackle structural challenges and specific critical issues.

In addition to improving MCS systems, respondents highlighted the need to develop strategies that would discourage IUU fishing and generate a better understanding of its impact. They also advocated the creation of incentives to favor compliance with the regulations in force. To this end, more than only enforcing more inspection activities, respondents believe that information and education campaigns, as well as compliance incentives, needs to be implemented.

Respondents also highlighted the need to raise consumer awareness and encourage effective market participation to become more demanding and request products from accredited legal fisheries.

3.2 Development of a priority national research agenda to improve fisheries management in Chile

This second issue identified by respondents was mainly prioritized by government officials, academia and SMEs, who consider there is a need to set strategic priorities to be included in medium- and long-term planning, which in turn should inform the research needs of government institutions involved in the fishing sector. According to respondents, existing research focuses on the short-term and exclusively on the fishing activities, neglecting the social and economic perspective. There was also the perception that, in some cases, there is a disconnection between research and the decision-making processes by management. This is particularly relevant for fisheries with Management Plans that have to deal with delayed fishery statistics, making it difficult to take decisions with the updated available information.

Respondents believe that there are constraints concerning Human Resources, infrastructure and funding for research. Nevertheless, the absence of a strategic vision stands out as a key opportunity for improvement. The lack of prospective studies on species that are currently not being and that could potentially contribute to diversifying the sector’s production, was exploited mentioned as an important gap resulting from this lack of strategic planning. A better understanding of environmental variability impacting fisheries are also gaps to be included in a future agenda.

To provide the national research agenda with a strategic vision, some respondents suggest creating a coordinating body responsible for identifying and systematizing research challenges, create and monitor plans and build strategic alliances with different agencies. This proposal is presented as a continuous and multidisciplinary process with a medium and long-term vision, aiming at the integration of principles of ecosystem management. It also incorporates the human component and seeks to strike a balance between ecosystem health and the well-being of fishing communities. In that regard, respondents believe that planning should be a participative process that involves research and government institutions, the industrial and artisanal sectors and relevant supply chain stakeholders. For the process to prove effective, some consider starting by identifying current limitations of resources available to the fisheries administration and in terms of fisheries knowledge. Another factor to be considered, is the adequate integration of local ecological knowledge and the empirical information provided in real time by the producing sector for research purposes.

3.3 Legitimacy of the fisheries law

According to artisanal sector stakeholders, NGOs, industry and government representatives, this issue required urgent action. An amendment to the fisheries legislation was approved in 2013, but despite the progress made in fisheries management (Ríos, 2015), the fisheries law was largely deemed illegitimate due to the corruption cases associated with its origin (Reyes et al., 2017).

Three different narratives were identified among the answers collected in 2020. Some respondents considered that the law was legitimate and appropriate from a technical standpoint. Others believed that the law has some positive aspects, but there is a need to change aspects linked to the assignment of rights. Finally, other respondents consider that, despite the positive aspects, the law should be repealed because it is illegitimate. Regardless the contrasting narratives, there was consensus regarding the urgent need to address this issue. Some even warned against the risks derived from delaying finding a timely solution, both for institutions and for users, given that the lack of legitimacy increases the risk of non-compliance.

Despite the polarizing climate, the 2020 survey shed light on shared concerns, not only regarding a call for action, but also regarding the proposed solutions. Respondents indicated that the solution was to create a democratic and participative space to identify strengths and weaknesses of the law, and to establish the most appropriate corrective actions in the development of a new legislative framework. This issue was highlighted by respondents as a challenge due to the lack of trust amongst sectors, specially between the artisanal and the industrial sectors, at the time the survey was carried out.

3.4 Development of a new national fisheries policy

This fourth issue was considered urgent by respondents from academia, government, the artisanal sector and NGOs. Respondents referred to the lack of an explicit fisheries policy and pointed out that the 2007 is out of date.

Respondents suggested that the current vision and goals of the fisheries policy is too narrow as it focuses mainly on the maximum exploitation of resources, neglecting other areas, such as conserving the ecosystem, adapting to climate change, creating greater added value, and maintaining the jobs and the economic well-being of the fishing communities. A new fisheries policy should therefore have clear goals on areas beyond resource exploitation (e.g., job creation, food security, export revenues) and actions to meet those.

Respondents refer to the need for the new fisheries policy proposal to build a common vision for the development of the sector in the long term by performing a holistic analysis of the Chilean fisheries sector. This analysis should result from the work of multidisciplinary groups and consultation processes among stakeholders. In addition, to avoid legitimacy problems, this process requires a high level of independence of the authorities.

3.5 Updating the Artisanal fisheries registry

This issue was considered urgent by the artisanal and industrial sector, government officials and NGOs. There seemed to be ample consensus around the fact that Chilean fisheries are facing great challenges because the RPA is outdated. This out-of-date registry has failed to limit fishing efforts creates perverse incentives by enabling IUU fishing.

The original purpose of the RPA was to adapt fleets size to biologically sustainable exploitation. Nevertheless, respondents state that this has not been accomplished, because the registration process is not dynamic enough: fishers who have passed away or who have retired remain on the list, while active fishers cannot access the registry. As a result, many young fishers end up fishing illegally or buying a place in the registry from retired fishers.

Stakeholders suggested the need to apply existing expiration rules for inactive fishing permits in the short term. In the medium and long terms, respondents recommend migrating to a more dynamic system that articulates RPA data with landing certificates and other databases. This new system would allow rapid identification of fishers who discontinue their fishing activity, enable a better control of artisanal fishing efforts and provide the dynamism that the activity requires in the assignment of artisanal fishing permits.

4 Actionable recommendations

This section summarizes the five main actionable policy recommendations in ranking order to improve fisheries governance and to address sustainability challenges in Chilean fisheries:

-

Improve budget allocation for MCS activities by SERNAPESCA and related government agencies. Prepare an official diagnosis on the impacts of IUU fishing in Chile to estimate its value in terms of volume and economic impact. This issue should also be included in the Management Plans of different fisheries to design a joint strategy, set goals and deadlines that will help reach specific milestones in the eradication of IUU fishing. Activities should also include information and education initiatives as well as the implementation of incentives for harvesters.

-

Develop a national research agenda to identify and systematize research gaps and needs through a continuous, multidisciplinary process with a medium- and long-term vision. This new research agenda should not only focus on the exploitation of target species, but it should also be aligned with ecosystem management principles and incorporate socioeconomic research seeking to maintain the balance of environmental health and human well-being.

-

Create a participative space where stakeholders can discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the legislation and agree on any corrective actions. Today’s polarized scenario among sectors represents a barrier, so tackling the lack of legitimacy of the fisheries law is an urgent priority measure.

-

Update the fisheries policy to establish a common vision between sectors and stakeholders and promote the long-term development of the sector. This should be a binding political process.

-

Update the RPA in order to have a dynamic tool to grant fishing rights and adequate the effort to each fishery. The update of the RPA should involve connection with other relevant registries that control artisanal fisheries (e.g., sanctions, landings, logbooks).

5 Discussion

The 2020 survey to key informants involved in the fishery served to identify some of the priority policy areas that stakeholders from different sectors within the sector considered as priority. Yet, it also served to highlight the areas where more awareness is needed, such as social, gender and equity issues. The profiles of the informants, which for example did not include specific groups (e.g., indigenous peoples) as respondents, have probably impacted the focus on some relevant issues, such as the tenure rights of indigenous communities. The effect of this methodological gap has been probably exacerbated by the discrimination that Indigenous peoples suffer in Chile, not only when it comes to fisheries related issues (Hiriart-Bertrand et al., 2020), but in other areas of life (see e.g., Merino et al., 2009; de Cea et al., 2016).

Since the development of the survey in 2019-2020, a number of papers have reinforced the relevance of IUU fishing in Chile (Oyanedel, 2019), analyzing the specific motivations for non-compliance with specific rules (such as the quota) (Oyanedel et al., 2020), the essential role of traders in shaping illegality in market trends (Oyanedel et al., 2021) and the required multidimensional interventions that are required to resolve the wicked challenges of illegal trade in the Chilean artisanal hake fishery (Oyanedel et al., 2022). Building upon analysis of 20 Chilean fisheries, Donlan et al. (2020) estimated that illegal landings account for as much as 70% of the national landings and propose a methodology that, building upon enforcement officers’ knowledge, enables effective institutionalization of illegal fishing estimates. All this recent evidence (see as well RPS Submitter et al., 2022) points that the issue of illegal fishing remains largely unresolved, and that the development of a new legal framework can contribute to address, at least partially. New policy developments in this field will largely benefit from the extensive advances in knowledge on the topic in Chile resulting from the increased interest by a number of researchers.

Since the completion of the online survey in 2020, some advances have been made in regards the update of the Artisanal Fisheries Registry. The Chilean government opened the RPA to crew members in some specific fisheries as jumbo flying squid, stone crab among other fisheries (SUBPESCA, 2020b). By June 2022 the Chilean government initiated an agenda with 20 actions to support the artisanal fishing sector; amongst them the issuance of a bill aimed at improving the system of deadlines to regularize the registration in the RPA in the event of the death of the vessel owner. Additionally, the government rolled out a system for replacing vacancies generated by fishers that have passed away or have retired in fisheries without risk of overexploitation or whose status allows it (Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo, 2022). Effectively addressing the shortages of an outdated RPA is a crucial issue for the governance of small-scale fisheries as it has direct ramifications for tenure rights and IUU fishing, but also to the entire co-management system because, as pointed out by Tapia-Jopia (2022), the lack of a complete RPA prevents equitable access to representation within the Management Committees. Álvarez Burgos (2020) points as well to the ramifications that an incomplete RPA have in terms of gender equity, as women working in the sector who are not directly involved in the fishing itself cannot register in the RPA, leaving them as informal workers, without social protection and with less tools to participate in productive development funds. Some improvements have been incorporated in August 2021 in order to promote gender equity in the fisheries and aquaculture sector (Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, 2021). Amongst other issues, the policy ensures that women’s representation in any participatory platform of the fishers’ governance system (such as the Management Committees and the Technical Scientific Committees) is at a minimum of one third of the total elected members (with a maximum of two thirds). It is still soon to evaluate the implementation of these recent policy improvements.

Upon recent years, challenges have also been raised regarding communications flows, mainly downward and upward, between fishers and Management committees’ representatives. Regarding downward communications, Reyes et al., 2017 recommends disposing an operating protocol for Management Committees that includes a communication and dissemination plan, since it is essential to inform the management measures included in the management plans to local users. Nevertheless, little is still known about upwards communications, namely the way fishers communicate their concerns to Management Committees representatives. In this sense, progress needs to be done in the design of fisheries management models that consider local information and traditional knowledge. This issue becomes more relevant when we analyze data-poor populations. According to Reyes et al. (2017), participation could be improved if Management Committees establishes periods for groups of people and/or institutions to present their concerns, suggestions, studies, background regarding to managements plans.

The current government has taken steps to address one of the main policy improvements identified in the 2020 survey, the lack of legitimacy of the fisheries law. The development of a new legal framework should focus on addressing the root causes that triggered the lack of legitimacy the previous legal framework (tenure rights for the artisanal sector), strike a balance with the positive elements of the old fisheries legal framework (as pointed out by the 2020 survey informants, mainly linked to co-management and the polycentric approach) and include the few but important policy improvements that were introduced since 2020. Achieving this balance will benefit from extensive consultation and stakeholder participation, as was pointed out by survey respondents.

Statements

Author contributions

RG-W and RV: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, data analysis, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization. GO, GA, LH-B and RL-C: writing – review and editing. EA-P: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Walton Family Foundation (Grants 2018-524, 00104468 and 00104470).

Acknowledgments

Special acknowledgement is given to Renu Mittal for her work in fostering an environment of collaboration between the organisations involved in this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2023.1073397/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^ http://www.subpesca.cl/portal/616/w3-propertyvalue-38010.html

2.^ https://globalfishingwatch.org/

3.^ https://fisheries.msc.org/

4.^ https://es.surveymonkey.com/r/5SYV9VW

5.^The relevance and urgency of these two improvement areas cannot be compared with the relevance-urgency scoring results of the other topics due to the differences in the sampling size. The two newly identified improvement areas were scored only by the 27 respondents who identified them as a priority, in contrast to the 152 respondents who scored the initially identified 16 improvement areas.

References

1

Aceituno P. Solar P. Bitar S. (2017) Estrategia Chile 2030 aporte de ideas para una reflexión nacional. Available at: www.prospectivayestrategia.cl (Accessed July 30, 2022).

2

Álvarez Burgos M. C. (2020). No queremos ser pesca acompañante, sino pesca objetivo. Interfaces socioestatales sobre enfoque de género en la pesca artesanal en Chile. Runa41(2), 67–85. Instituto de Ciencias Antropológicas, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires. doi: 10.34096/runa.v41i2.8691

3

Andrade Bone E. (2016) Ley longueira: Una ley de pesca que carece de legitimidad (Piensa Chile). Available at: http://piensachile.com/2016/09/ley-longueira-una-ley-pesca-carece-legitimidad/ (Accessed September 8, 2022).

4

AQUA (2017) Cambios Al RPA: Sin registro para pescar. Available at: https://www.aqua.cl/reportajes/cambios-al-rpa-sin-registro-pescar/ (Accessed October 10, 2022).

5

AQUA (2018) La pesca ilegal en Chile, un problema más allá de nuestras fronteras. Available at: https://www.aqua.cl/columnas/la-pesca-ilegal-chile-problema-mas-alla-nuestras-fronteras/ (Accessed October 10, 2022).

6

AQUA (2019) Subpesca acogió petición para la apertura de registros artesanales. Available at: https://www.aqua.cl/2019/12/30/subpesca-acogio-peticion-para-la-apertura-de-registros-artesanales/ (Accessed July 04, 2022).

7

Bezamat S. (2017). Las Comunidades de Pescadores Artesanales y La Resiliencia Comunitaria. El Fortalecimiento de La Resiliencia Comunitaria Utilizando Los Enfoques de Riesgo y de Medios de Vida Sostenibles [dissertation/master's thesis]. Santiago, Chile: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

8

Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile (2018) Pesca ilegal, no declarada y no reglamentada en américa latina: Un problema para abordar en conjunto (Biblioteca Del Congreso Nacional de Chile). Available at: https://www.diarioconstitucional.cl/2018/06/25/sobre-la-pesca-ilegal-no-declarada-y-no-reglamentada-en-america-latina-un-problema-para-abordar-en-conjunto/ (Accessed September 27, 2022).

9

Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile (2021) Ley 21370. modifica cuerpos legales con el fin de promover la equidad de género en el sector pesquero y acuícola. Available at: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1164124 (Accessed July 4, 2022).

10

Carrere M. (2018) Sobreexplotación, pesca ilegal y conservación: Este Es El panorama del océano en Chile (MONGABAY). Available at: https://es.mongabay.com/2018/08/oceano-en-chile-sobreexplotacion/ (Accessed September 8, 2022).

11

Chile Atiende (2019) Inscripción en El registro pesquero artesanal (RPA). Available at: https://www.chileatiende.gob.cl/fichas/2893-inscripcion-en-el-registro-pesquero-artesanal-rpa (Accessed September 08, 2022).

12

Colegio de Ingenieros Agrónomos de Chile (2019) Funciones que tendrá El nuevo ministerio de agricultura, alimentos, pesca y recursos forestales. Available at: https://ingenierosagronomos.cl/funciones-que-tendra-el-nuevo-ministerio-de-agricultura-alimentos-pesca-y-recursos-forestales/ (Accessed October 10, 2022).

13

Cuba A. (2019). “Extractive industries in coastal and marine zones,” in Marine and Fisheries Policies in Latin America: A Comparison of Selected Countries, ed. Ruiz MullerM.OyanedelR.MonteferriB., (Routledge) 55–65. doi: 10.4324/9780429426520

14

Cuba A. (2019). “Extractive industries in coastal and marine zones,“. Mar. Fisheries Policies Latin America: A Comparison Selected Countries, 55–65. doi: 10.4324/9780429426520

15

de Cea M. Heredia M. Valdivieso D. (2016). The Chilean elite’s point of view on indigenous peoples. Can. J. Latin Am. Caribbean Stud.41 (3), 328–347. doi: 10.1080/08263663.2016.1225675

16

Diario Concepción (2018) La inaceptable magnitud de la pesca ilegal chilena. Available at: https://www.diarioconcepcion.cl/editorial/2018/04/15/la-inaceptable-magnitud-de-la-pesca-ilegal-chilena.html (Accessed October 10, 2022).

17

Donlan C. J. Wilcox C. Luque G. M. Gelcich S. (2020). Estimating illegal fishing from enforcement officers. Sci. Rep.10 (1), 1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69311-5

18

El Mostrador (2022a). Available at: https://www.elmostrador.cl/dia/2022/01/07/caso-corpesca-jaime-orpis-llega-a-tribunales-para-cumplir-condena-por-fraude-al-fisco-y-cohecho/ (Accessed October 12, 2022).

19

El Mostrador (2022b). Available at: https://www.elmostrador.cl/dia/2022/08/25/gobierno-anuncio-que-presentara-nueva-ley-de-pesca-en-2023/ (Accessed September 8, 2022).

20

Empresa Océano (2017) Tripulantes pesqueros: Los problemas de la pesca en Chile son la captura ilegal y exceso de flota artesanal sin reclasificar. Available at: http://www.empresaoceano.cl/tripulantes-pesqueros-los-problemas-de-la-pesca-en-chile-son-la-captura/empresaoceano/2017-11-06/165220.html (Accessed October 10, 2022).

21

Equipo el Día (2019) Sonapesca propone 10 medidas para combatir la pesca ilegal en la región y El país. Available at: https://www.impreso.diarioeldia.cl/economia/pesca/sonapesca-propone-10-medidas-para-combatir-pesca-ilegal-en-region-pais (Accessed September 8, 2022).

22

FAO (2016) Informe final. proyecto UTF/CHI/042/CHI. asistencia para la revisión de la ley general de pesca y acuicultura, en El Marco de Los instrumentos, acuerdos y buenas prácticas internacionales para la sustentabilidad y Buena gobernanza del sector pesquero. Available at: https://www.subpesca.cl/portal/616/articles-94917_informe_final.pdf (Accessed October 12, 2022).

23

FAO (2017) Plan para la seguridad alimentaria, nutrición y erradicación del hambre de la CELAC 2025 (Santiago de Chile: Capítulo Chile). Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/i4493s/i4493s.pdf (Accessed October 10, 2022).

24

FAO (2022) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2022. towards blue transformation (Rome: FAO). doi: 10.4060/cc0461es (Accessed October 10, 2022).

25

Gelcich S. (2014). Towards polycentric governance of small-scale fisheries: insights from the new ‘Management plans’ policy in Chile. Aquat. Conservation: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst.24, 575–581. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2506

26

González Poblete E. Cerda D’Amico R. Quezada Olivares J. Martínez González G. López Araya E. Thomas Álvarez F. et al . (2013). Propuesta de política pública de desarrollo productivo para la pesca artesanal. In: Estudio para la determinación de una propuesta de política pública de desarrollo productivo para la pesca artesanal. pontificia universidad católica de valparaíso, escuela de ciencias del mar a encargo de la subsecretaría de pesca, valparaíso. Available at: https://www.subpesca.cl/portal/618/articles-80500_recurso_1.pdf (Accessed September 13, 2022).

27

Hiriart-Bertrand L. Silva J. S. Gelcich S. (2020). Challenges and opportunities of implementing the marine and coastal areas for indigenous peoples policy in Chile. Ocean Coast. Manage.193, 105233. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105233

28

Ibañez F. (2018) ¿Por qué Se busca modificar la ley de pesca? pauta. Available at: https://www.pauta.cl/negocios/bloomberg/por-que-se-busca-modificar-la-ley-de-pesca (Accessed October 10, 2022).

29

IFOP (2016) Informe hito crítico: Proyecto ‘Fortalecimiento de capacidades tecnológicas para la generación de valor público del instituto de fomento pesquero – IFOP – etapa perfil’ código. Available at: https://www.ifop.cl/cp/wp-content/contenidos/uploads/minisitios/7/2016/06/Informe_hito_cr%C3%ADtico.pdf.

30

IFOP (2018a). Informe final: Programa de observadores científicos 2017-2018. In: Programa de investigación del descarte y captura de pesca incidental en pesquerías pelágicas. programa de monitoreo y evaluación de Los planes de reducción del descarte y de la pesca incidental 2017-2018 (Santiago de Chile). Available at: https://www.ifop.cl/wp-content/contenidos/uploads/RepositorioIfop/InformeFinal/P-581129.pdf (Accessed October 12, 2022).

31

IFOP (2018b) Enfoque ecosistémico de la pesca (EEP): Definición y alcances para El manejo y la investigación aplicada. Available at: https://www.ifop.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/EEP-2-2.pdf (Accessed September 13, 2022).

32

Merino M. E. Mellor D. J. Saiz J. L. Quilaqueo D. (2009). Perceived discrimination amongst the indigenous mapuche people in Chile: Some comparisons with Australia. Ethnic Racial Stud.32 (5), 802–822. doi: 10.1080/01419870802037266

33

Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo (2022). Available at: https://www.economia.gob.cl/2022/06/20/gobierno-compromete-20-medidas-de-apoyo-a-la-pesca-artesanal.htm (Accessed June 30, 2022).

34

Monteza D. (2020). Evaluación de impacto de Los planes de manejo pesquero sobre Los ingresos de Los pescadores artesanales de recursos bentónicos en Chile. [dissertation/master's thesis]. (Santiago, Chile: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile).

35

Observatorio Regional de planificación para el Desarrollo de América Latina y el Caribe (2018)Programa de gobierno de chile, (2018-2022). In: Observatorio regional de planificación para El desarrollo de américa latina y El caribe. Available at: https://observatorioplanificacion.cepal.org/es/planes/programa-de-gobierno-de-chile-2018-2022 (Accessed September 15, 2022).

36

Oyanedel R. (2019). Pesca ilegal e incumplimiento. mar, costas y pesquerías: Una mirada comparativa desde Chile, méxico y perú (Sociedad Peruana de Derecho Ambiental), 71–81. Available at: https://acortar.link/zUiV1j.

37

Oyanedel R. Gelcich S. Mathieu E. Milner-Gulland E. J. (2022). A dynamic simulation model to support reduction in illegal trade within legal wildlife markets. Conserv. Biol.36 (2), 1–11. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13814

38

Oyanedel R. Gelcich S. Milner-Gulland E. J. (2020). Motivations for (non)compliance with conservation rules by small-scale resource users. Conserv. Lett.13 (5), 1–9. doi: 10.1111/conl.12725

39

Oyanedel R. Gelcich S. Milner-Gulland E. J. (2021). A framework for assessing and intervening in markets driving unsustainable wildlife use. Sci. Total Environ.792, 148328. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148328

40

Partarrieu B. (2015) Ley de pesca: Pagos ilícitos a parlamentarios no serán investigados por la FAO. Available at: https://ciperchile.cl/2015/05/28/ley-de-pesca-pagos-ilicitos-a-parlamentarios-no-seran-investigados-por-la-fao/ (Accessed September 15, 2022).

41

Portal del Campo (2017) Pesca ilegal en Chile hasta cuadruplica a la lícita y gobierno la combatirá con nueva ley. Available at: https://portaldelcampo.cl/Noticias/61872_pesca-ilegal-en-chile-hasta-cuadruplica-a-la-licita-y-gobierno-la-combatira-con-nueva-ley.html (Accessed October 10, 2022).

42

Portal Frutícola (2020) Chile: Firman proyecto de ley que crea ministerio de agricultura, alimentos y desarrollo rural. Available at: https://www.portalfruticola.com/noticias/2020/01/22/chile-firman-proyecto-de-ley-que-crea-ministerio-de-agricultura-alimentos-y-desarrollo-rural/ (Accessed October 10, 2022).

43

Queirolo D. Canales C. Gatica C. Sepúlveda A. Ahumada M. Apablaza P. et al . (2019) Selectividad en redes de arrastre en uso en la pesquería de merluza común: su efecto en la explotación, en la fauna acompañante y en la captura incidental. Available at: https://www.subpesca.cl/fipa/613/articles-97773_informe_final.pdf (Accessed October 12, 2022). Informe Final. Informe Técnico FIPA N°2017-47.

44

Ramírez M. (2018). Tratamiento internacional y nacional de la pesca ilegal, no declarada y no reglamentada. [dissertation/bachelor's thesis]. (Santiago, Chile: Universidad de Chile).

45

Reyes F. Gelcich S. Ríos M. (2017). “Problemas globales, respuestas locales: Planes de manejo como articuladores de un sistema de gobernabilidad policéntrica de Los recursos pesqueros,” in Propuestas para Chile. Eds. IrarrázavalI.PiñaE.LetelierM. (Santiago de Chile: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile), 121–156. Propuestas para Chile, Concurso Políticas Públicas 2016.

46

Ríos M. (2015) Ley de pesca no 20.657 y misceláneas: Avances y desafíos en su implementación. serie informe económico, 252. instituto libertad y desarrollo. Available at: https://lyd.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/SIE-252-Ley-de-Pesca-N%C2%BA-20657-y-miscelaneas-Avances-y-desafios-en-su-implentacion-MRios-Octubre2015.pdf (Accessed October 10, 2022).

47

Ríos M. Gelcich S. (2017). Los Derechos de pesca en Chile: Asimetrías entre armadores artesanales e industriales. In: Center of applied ecology and sustainability (CAPES) (Santiago, Chile: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile). Available at: https://www.sociedadpoliticaspublicas.cl/archivos/noveno/Energia_Rios_Monica.pdf (Accessed October 10, 2022).

48

RPS Submitter CLALS (American University) Crime, InSight (2022) IUU fishing crimes in Latin America and the Caribbean (August 2022). Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4200724http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4200724 (Accessed October 12, 2022). CLALS Working Paper Series No. 39, 2022.

49

Ruiz Muller M. Oyanedel R. Monteferri B. (2020). Marine and fisheries policies in Latin America: A comparison of selected countries. Mar. Fisheries Policies Latin America. doi: 10.4324/9780429426520

50

Senado de la República de Chile (2019) Sectores artesanal e industrial expusieron sus visiones respecto Al proyecto que modifica la ley general de pesca. Available at: https://www.senado.cl/sectores-artesanal-e-industrial-expusieron-sus-visiones-respecto-al/senado/2019-08-01/160132.html (Accessed September 10, 2022).

51

SERNAPESCA (2019) Fiscalización en pesca y acuicultura, informe de actividades 2019. Available at: http://www.sernapesca.cl/sites/default/files/informe_actividades_de_fiscalizacion_sernapesca_2019.pdf (Accessed October 10, 2022).

52

Servicio Civil (2017) Condiciones y representación de las mujeres en El sector público. Available at: https://documentos.serviciocivil.cl/actas/dnsc/documentService/downloadWs?uuid=7af47d89-d5dc-426c-8487-c814abd9bd4c (Accessed October 10, 2022).

53

Soy Chile (2019) Mujeres de la pesca artesanal realizan intensa lucha por visibilizar su aporte en El sector. Available at: https://www.soychile.cl/Santiago/Sociedad/2019/05/15/595844/Mujeres-de-la-Pesca-Artesanal-realizan-intensa-lucha-por-visibilizar-su-aporte-en-el-sector.aspx (Accessed September 08, 2022).

54

SUBPESCA (2019) Mujeres y hombres en El sector pesquero y acuicultor del Chile 2019. Available at: http://www.sernapesca.cl/sites/default/files/3.1_mujeres_y_hombres_en_el_sector_pesquero_y_acuicultor_2019.pdf (Accessed September 19, 2022).

55

SUBPESCA (2020a) Informe sectorial de pesca y acuicultura 2019. Available at: https://www.subpesca.cl/portal/618/articles-106845_documento.pdf (Accessed October 12, 2022).

56

SUBPESCA (2020b). Available at: https://www.subpesca.cl/portal/617/w3-article-106409.html (Accessed June 30, 2022).

57

SUBPESCA (2021) Estado de situación de las principales pesquerías chilenas, año 2020. Available at: https://www.subpesca.cl/portal/618/articles-110503_recurso_1.pdf (Accessed September 19, 2022).

58

Tapia C. Durán S. Rodríguez R. Díaz M. (2016). Propuesta de política nacional de algas. Informe final (Chile: Proyecto 4728-48-LP15 de la Subsecretaría de Pesca y Acuicultura), 146.

59

Tapia-Jopia C. (2022). “Análisis del modelo de gobernanza del manejo pesquero en Chile: los comités de manejo,” in Miradas interdisciplinarias de la actividad pesquera en américa latina: hacia nuevos abordajes y una perspectiva comparada. doi: 10.4000/nuevomundo.86926

60

Villanueva García Benítez J. Flores-Nava A. (2019). The contribution of small-scale fisheries to food security and family income in Chile, Colombia, and Peru. In: Viability and sustainability of small-scale fisheries in Latin America and the Caribbean (MARE Publication Series) (Accessed September 19, 2022).

61

Villarroel C. (2017). Una reflexión intelectual, moral y política sobre la participación de Los pescadores artesanales en la ordenación de recursos marinos de Chile: Aportes desde El pluralismo y la traducción intercultural 1 (Accessed October 12, 2022).

Summary

Keywords

Chilean fisheries, fisheries management, policy, governance, sustainability

Citation

Gozzer-Wuest R, Vinatea Chávez RA, Olea Stranger G, Araya Goncalves G, Hiriart-Bertrand L, Labraña-Cornejo R and Alonso-Población E (2023) Identifying priority areas for improvement in Chilean fisheries. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1073397. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1073397

Received

18 October 2022

Accepted

20 January 2023

Published

10 February 2023

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Angus Morrison-Saunders, Edith Cowan University, Australia

Reviewed by

Christian T.K.H. Stadtlander, Independent researcher, United States; Lida Teneva, Independent researcher, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Gozzer-Wuest, Vinatea Chávez, Olea Stranger, Araya Goncalves, Hiriart-Bertrand, Labraña-Cornejo and Alonso-Población.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rolando Labraña-Cornejo, rolando.labrana@sustainablefish.org

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to Marine Affairs and Policy, a section of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.