Abstract

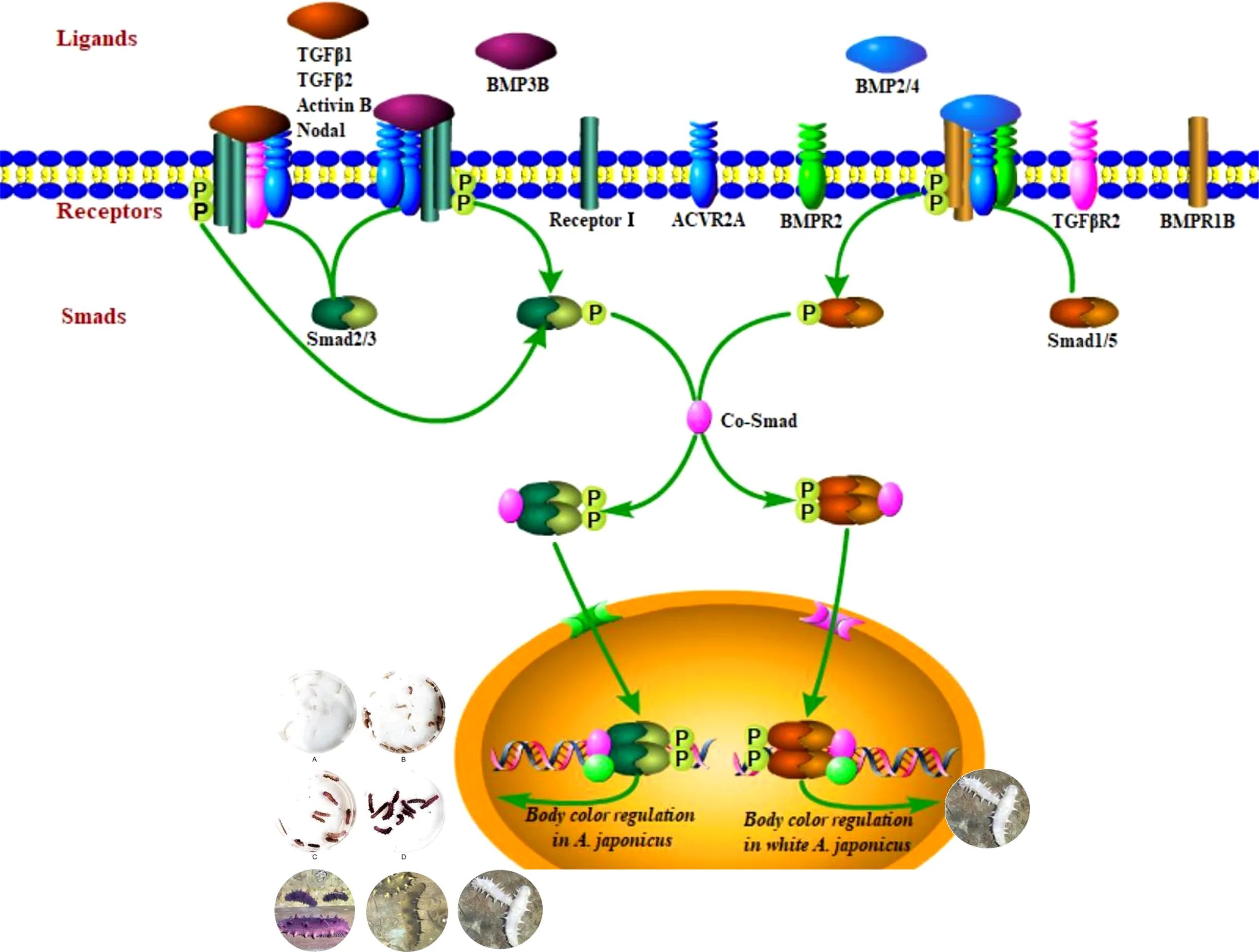

Pigmentation mediated by the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling pathway is a key trait for understanding environmental adaptability and species stability. In this study, TGFβ signaling pathway members and their expression patterns in different color morphs of the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus were evaluated. Using a bioinformatics approach, 22 protein sequences of TGFβ signaling pathway members in A. japonicus were classified, including 14 that were identified for the first time in the species, including 7 ligands, 6 receptors, and 1 R-Smad. We further evaluated mRNA expression data for different color morphs and pigmentation periods. These results support the hypothesis that both subfamilies of the TGFβ superfamily, i.e., the TGFβ/activin/Nodal and BMP/GDF/AMH subfamilies, are involved in the regulation of pigmentation in A. japonicus. The former subfamily was complete and contributes to the different color morphs. The BMP/GDF/AMH subfamily was incomplete. BMP2/4-induced differentiation of white adipocytes was regulated by the BMP2/4–ACVR2A–Smad1 signaling pathway. These findings provide insight into the TGFβ family in early chordate evolution as well as the molecular basis of color variation in an economically valuable species.

1 Introduction

The sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus is a commercially important marine species in China (Chen et al., 2022). Color variation, one of the most important characteristics of A. japonicus, plays a significant role in determining market price (Kang et al., 2011) and is an important trait for breeding. In China, this species is mainly green, and purple and white morphs are very rare and highly valuable (Bai et al., 2016). Extensive studies have shown that the growth and development of sea cucumber are affected by various environmental factors, such as temperature and salinity (Chen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Ji et al., 2008). There are significant differences in the tolerance of sea cucumbers with different body colors to environmental factors (Bao, 2008; Guo et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). For example, purple A. japonicus has a wider temperature range and stronger salt tolerance, while the white morph has a higher temperature tolerance but narrower range of salinity tolerance than those of the green morph (Zhao et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2013).

Pigmentation is a tractable and relevant trait for understanding key issues in evolutionary biology such as adaptation, speciation and the maintenance of balanced polymorphisms (Henning et al., 2013).Substantial recent research has focused on the identification of genetic pathways that determine pigmentation variation (Hubbard et al., 2010; Henning et al., 2013). Studies of animal models have found that the TGFβ signaling pathway mediates many biological processes, such as pigmentation, tissue and organ development, and stress resistance (Cheng, 2008; Hubbard et al., 2010). Recent structural, biochemical, and cellular studies have provided significant insight into the mechanisms underlying TGFβ signaling. In brief, a TGFβ ligand initiates signaling by binding to and bringing together type I and type II receptor on the cell surface. This allows receptor II to phosphorylate receptor I, which then regulates target gene expression by the phosphorylation of Smad proteins. The number and type of TGFβ family members have been evaluated in model organisms, ranging from worms and flies to mammals (Massagué and Chen, 2000; Patterson and Padgett, 2000; ten Dijke et al., 2000). Six conserved cysteine residues characteristic of the TGFβ family are encoded by 6 open reading frames in worms, 9 in flies, and 42 in humans (Linton et al., 2001).

Although studies of the TGFβ family in non-model organisms are increasing, relatively little is known about functional changes and divergence in expression patterns between invertebrates and vertebrates (Lapraz et al., 2007; Weiss and Attisano, 2013; Zheng et al., 2018). Echinoderms, which first appeared in the early Cambrian period (Bottjer et al., 2006), occupy a critical phylogenetic position for understanding the origin of chordates (Lowe et al., 2015). The radiation of echinoderms was believed to be responsible for the Mesozoic Marine Revolution (Signor and Brett, 1984). In particular, sea cucumbers are an outstanding representative of the phylum, as they have survived ice ages and are considered “living fossils” (Bottjer et al., 2006). Despite the importance of pigmentation mediated by the TGFβ signaling pathway (Cheng, 2008; Hubbard et al., 2010; Henning et al., 2013), few studies have evaluated the TGFβ signaling pathway in sea cucumbers. Only 14 ligands (some sharing the same name), 6 receptors, and 2 R-Smads have been recorded in GenBank. In addition, some loci have informal names, such as Sj-BMP2/4 (accession no. PIK56114.1 and BAC53989.1), and some were not classified in detail, e.g., putative TGFβ (accession no. PIK61515.1). Accordingly, their functions and roles in morphs with different body colors are unclear. This can be explained, in part, by poor sampling of genomes (Sodergren et al., 2006; Cameron et al., 2015; Hall et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). In this study, the types and quantities of TGFβ signaling pathway members in A. japonicus were characterized for the first time and expression levels in different color morphs and developmental stages were evaluated, providing an important basis for analyses of functions of TGFβ signaling in invertebrates.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sequence analysis

All TGFβ ligand receptors and Smad protein sequences of A. japonicus available on NCBI were obtained and compared using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) (Tables 1–3). Multiple sequence alignments were analyzed using the ClustalW Multiple Alignment program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/). Separate trees were generated based on ligand, receptor, and SMAD amino acid sequences using the neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm within MEGA version 7.0. The reliability of the tree was assessed by 1000 bootstrap repetitions.

Table 1

| Accession no. | Protein name | Species |

|---|---|---|

| PIK34829.1 | putative TGFβ1 like | Apostichopus japonicus |

| QHG11580.1 | putative TGFβ1X1 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| PIK56215.1 | putative TGFβ1X1 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_029964045.1 | TGFβ1X2 | Salarias fasciatus |

| XP_041850924.1 | TGFβ1X1 | Melanotaenia boesemani |

| XP_031614329.1 | TGFβ1 | Oreochromis aureus |

| XP_033486555.1 | TGFβ1X1 | Epinephelus lanceolatus |

| XP_040902844.1 | TGFβ1 | Toxotes jaculatrix |

| XP_033851930.2 | TGFβ1X1 | Acipenser ruthenus |

| XP_035241816.1 | TGFβ1X1 | Anguilla anguilla |

| XP_026865903.2 | TGFβ1X2 | Electrophorus electricus |

| XP_036440909.1 | TGFβ1X1 | Colossoma macropomum |

| KAG9273341.1 | TGFβ1X1 | Astyanax mexicanus |

| PIK45926.1 | BMP2A | Apostichopus japonicus |

| PIK48439.1 | BMP2 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| PIK57098.1 | BMP | Apostichopus japonicus |

| AAF19841.1 | BMP2/4 | Branchiostoma belcheri |

| QYF06707.1 | BMP2/4 | Holothuria scabra |

| PIK56114.1 | Sj-BMP2/4 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| BAC53989.1 | Sj-BMP2/4 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| AAD28038.1 | BMP2/4 | Lytechinus variegatus |

| ACA04460.1 | BMP2/4 | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| ABG00199.1 | BMP2/4 | Paracentrotus lividus |

| BBC77411.1 | BMP2/4 | Temnopleurus reevesii |

| PIK37799.1 | BMP3/3B | Apostichopus japonicus |

| KAF3695343.1 | BMP3 | Channa argus |

| XP_033946079.1 | BMP3 | Pseudochaenichthys georgianus |

| XP_007425424.1 | BMP3 | Python bivittatus |

| XP_042727338.1 | BMP3 | Lagopus leucura |

| XP_021252303.1 | BMP3 | Numida meleagris |

| PIK42868.1 | TGFβ family member nodal | Apostichopus japonicus |

| ACF32774.1 | Nodal | Heliocidaris erythrogramma |

| ACF32773.1 | Nodal | Heliocidaris tuberculata |

| XP_036937551.1 | Nodal2 | Acanthopagrus latus |

| XP_034426535.1 | Nodal2 | Hippoglossus hippoglossus |

| KFM00388.1 | Nodal | Aptenodytes forsteri |

| XP_035248296.1 | Nodal | Anguilla anguilla |

| RXN30610.1 | Nodal | Labeo rohita |

| QYF06711.1 | GDF8 | Holothuria scabra |

| AJQ81037.1 | GDF8 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_013394669.1 | GDF8 | Lingula anatina |

| XP_014253049.1 | GDF8 | Cimex lectularius |

| XP_046672106.1 | GDF8 | Homalodisca vitripennis |

| RWS12911.1 | GDF8 | Dinothrombium tinctorium |

| XP_023223240.1 | GDF8 | Centruroides sculpturatus |

| QYF06710.1 | inhibin | Holothuria scabra |

| PIK34215.1 | putative inhibin beta C chain-like | Apostichopus japonicus |

| QYF06712.1 | activin | Holothuria scabra |

| PIK48233.1 | putative activin B X1 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_037927328.1 | INHβB | Teleopsis dalmanni |

| XP_022218905.1 | INHβA | Drosophila obscura |

| XP_017154392.1 | INHβA | Drosophila miranda |

| XP_002028363.1 | INHβA | Drosophila persimilis |

| XP_033236864.1 | INHβA | Drosophila pseudoobscura |

| QYF06713.1 | TGFβ2 | Holothuria scabra |

| PIK61515.1 | putative TGFβ2 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_022090565.1 | TGFβ2 | Acanthaster planci |

| XP_038073348.1 | TGFβ2 | Patiria miniata |

| BCB62973.1 | TGFβ | Patiria pectinifera |

| XP_041467929.1 | TGFβ2 | Lytechinus variegatus |

| XP_030855505.1 | TGFβ2 | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| QAV52899.1 | TGFβ | Mesocentrotus nudus |

| XP_041951915.1 | TGFβ3 | Alosa sapidissima |

| XP_042562890.1 | TGFβ3 | Clupea harengus |

| XP_039597176.1 | TGFβ3 | Polypterus senegalus |

| XP_028678165.1 | TGFβ3 | Erpetoichthys calabaricus |

| XP_042593951.1 | TGFβ2 | Cyprinus carpio |

| KAA0709699.1 | TGFβ2 | Triplophysa tibetana |

| XP_039388520.1 | TGFβ2X2 | Mauremys reevesii |

| XP_037751639.1 | TGFβ2 | Chelonia mydas |

| XP_005307005.1 | TGFβ2 | Chrysemys picta bellii |

| XP_003800184.1 | TGFβ2X2 | Otolemur garnettii |

| XP_008825028.1 | TGFβ2 | Nannospalax galili |

| CAA40672.1 | TGFβ2 | Mus musculus |

| XP_021016320.1 | TGFβ2X2 | Mus caroli |

Ligand protein sequences included in the present study.

Table 2

| Accession no. | Protein name | Species |

|---|---|---|

| XP_026886611.2 | TβR2 | Electrophorus electricus |

| TSK92904.1 | TβR2 | Bagarius yarrelli |

| XP_017324951.1 | TβR2 | Ictalurus punctatus |

| XP_026802727.2 | TβR2 | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus |

| PIK56848.1 | putative TβR2 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_033116886.1 | TβR2 | Anneissia japonica |

| XP_030828751.1 | TβR2 | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| XP_038058105.1 | TβR2 | Patiria miniata |

| XP_033624779.1 | TβR2 | Asterias rubens |

| PIK56867.1 | putative TβR3 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| CAC5417350.1 | TβR3 | Mytilus coruscus |

| CAG2237547.1 | TβR3 | Mytilus edulis |

| XP_038129033.1 | TβR3 | Cyprinodon tularosa |

| XP_040482976.1 | TβR3X2 | Ursus maritimus |

| XP_036901372.1 | TβR3X1 | Sturnira hondurensis |

| XP_025893663.1 | TβR3 | Nothoprocta perdicaria |

| XP_005238531.1 | TβR3X1 | Falco peregrinus |

| XP_040466106.1 | TβR3X2 | Falco naumanni |

| PIK46054.1 | putative BMPR2 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_033099609.1 | BMPR2 | Anneissia japonica |

| XP_790983.2 | BMPR2 | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| XP_041459768.1 | BMPR2 | Lytechinus variegatus |

| XP_033624844.1 | BMPR2 | Asterias rubens |

| XP_038058132.1 | BMPR2 | Patiria miniata |

| XP_022088502.1 | BMPR2 | Acanthaster planci |

| PIK52453.1 | putative ACVR2AX2 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_030828527.1 | ACVR2A | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| XP_041458652.1 | ACVR2A | Lytechinus variegatus |

| XP_038079379.1 | ACVR2AX1 | Patiria miniata |

| XP_033624296.1 | ACVR2A | Asterias rubens |

| XP_042301709.1 | ACVR2AX2 | Sceloporus undulatus |

| XP_032880604.1 | ACVR2AX2 | Amblyraja radiata |

| XP_043550051.1 | ACVR2AX1 | Chiloscyllium plagiosum |

| XP_041056629.1 | ACVR2A | Carcharodon carcharias |

| XP_022103314.1 | ACVR1X4 | Acanthaster planci |

| XP_033113857.1 | ACVR1X4 | Anneissia japonica |

| PIK59495.1 | putative ACVR1 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| NXL14502.1 | ACVR1 | Setophaga kirtlandii |

| NWI57693.1 | ACVR1 | Calyptomena viridis |

| NXY49840.1 | ACVR1 | Ceuthmochares aereus |

| NXB24442.1 | ACVR1 | Rhagologus leucostigma |

| NP_001383423.1 | ACVR1 | Gallus gallus |

| KFP78435.1 | ACVR1 | Apaloderma vittatum |

| XP_032435030.1 | BMPR1BX3 | Xiphophorus hellerii |

| XP_005795012.2 | BMPR1B | Xiphophorus maculatus |

| XP_027890208.1 | BMPR1BX3 | Xiphophorus couchianus |

| PIK51009.1 | putative BMPR1B | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_797469.4 | BMPR1B | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| XP_041485680.1 | BMPR1B | Lytechinus variegatus |

| XP_033644308.1 | BMPR1B | Asterias rubens |

| XP_038060789.1 | BMPR1B | Patiria miniata |

| XP_022089444.1 | BMPR1B | Acanthaster planci |

Receptor protein sequences included in the present study.

Table 3

| Accession no. | full name | Species |

|---|---|---|

| XP_041459990.1 | Smad4X1 | Lytechinus variegatus |

| XP_030827838.1 | Smad4X1 | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| XP_033109387.1 | Smad4X2 | Anneissia japonica |

| XP_033646664.1 | Smad4X1 | Asterias rubens |

| XP_022081844.1 | Smad4X1 | Acanthaster planci |

| XP_038058605.1 | Smad4X1 | Patiria miniata |

| XP_032649614.1 | Smad4 | Chelonoidis abingdonii |

| XP_035384718.1 | Smad4 | Electrophorus electricus |

| XP_030421567.1 | Smad4X1 | Gopherus evgoodei |

| XP_035314530.1 | Smad4X1 | Cricetulus griseus |

| XP_016004267.1 | Smad4X1 | Rousettus aegyptiacus |

| XP_030885493.1 | Smad4 | Leptonychotes weddellii |

| XP_033127281.1 | Smad6 | Anneissia japonica |

| ADW95340.1 | Smad6 | Paracentrotus lividus |

| XP_798238.2 | Smad6 | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| XP_022083936.1 | Smad6 | Acanthaster planci |

| XP_038077875.1 | Smad6 | Patiria miniata |

| XP_026878186.2 | Smad6b | Electrophorus electricus |

| XP_015996485.2 | Smad6X1 | Rousettus aegyptiacus |

| XP_003500538.2 | Smad6X1 | Cricetulus griseus |

| XP_032621963.1 | Smad6 | Chelonoidis abingdonii |

| XP_030434864.1 | Smad6 | Gopherus evgoodei |

| XP_016003943.1 | Smad7X1 | Rousettus aegyptiacus |

| XP_007644509.3 | Smad7X1 | Cricetulus griseus |

| XP_032637417.1 | Smad7X1 | Chelonoidis abingdonii |

| XP_030423387.1 | Smad7X1 | Gopherus evgoodei |

| XP_033124235.1 | Smad3 | Anneissia japonica |

| XP_041460773.1 | Smad3 | Lytechinus variegatus |

| XP_033624249.1 | Smad3X1 | Asterias rubens |

| XP_022083075.1 | Smad3X2 | Acanthaster planci |

| XP_038076479.1 | Smad3X1 | Patiria miniata |

| XP_006749953.1 | Smad3 | Leptonychotes weddellii |

| XP_026860560.1 | Smad3a | Electrophorus electricus |

| XP_015996478.1 | Smad3 | Rousettus aegyptiacus |

| XP_007639432.2 | Smad3X1 | Cricetulus griseus |

| XP_028706267.1 | Smad3X1 | Macaca mulatta |

| XP_030434068.1 | Smad3X1 | Gopherus evgoodei |

| XP_032620241.1 | Smad3 | Chelonoidis abingdonii |

| XP_035391548.1 | Smad2X1 | Electrophorus electricus |

| XP_032654336.1 | Smad2X1 | Chelonoidis abingdonii |

| XP_003501086.1 | Smad2X1 | Cricetulus griseus |

| XP_006738743.2 | Smad2 | Leptonychotes weddellii |

| XP_028693529.1 | Smad2X2 | Macaca mulatta |

| XP_036085916.1 | Smad2X1 | Rousettus aegyptiacus |

| PIK47643.1 | mothers against decapentaplegic-like protein 1 | Apostichopus japonicus |

| XP_032620791.1 | Smad1X2 | Chelonoidis abingdonii |

| XP_030420831.1 | Smad1X2 | Gopherus evgoodei |

| XP_036089426.1 | Smad1X1 | Rousettus aegyptiacus |

| XP_030895811.1 | Smad1 | Leptonychotes weddellii |

| XP_026859416.1 | Smad5 | Electrophorus electricus |

| XP_032631983.1 | Smad5 | Chelonoidis abingdonii |

| XP_030428443.1 | Smad5 | Gopherus evgoodei |

| XP_003503786.1 | Smad5 | Cricetulus griseus |

| XP_014996357.1 | Smad5X1 | Macaca mulatta |

| XP_015993196.1 | Smad5 | Rousettus aegyptiacus |

| XP_022079499.1 | Smad5X2 | Acanthaster planci |

| XP_033632185.1 | Smad5 | Asterias rubens |

| XP_038055290.1 | Smad5 | Patiria miniata |

| XP_041455371.1 | Smad5 | Lytechinus variegatus |

| XP_030836187.1 | Smad5 | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus |

| ACU12852.1 | Smad1 | Paracentrotus lividus |

| PIK47644.1 | Smad1 | Apostichopus japonicus |

Smad protein sequences included in the present study.

2.2 Animals

2.2.1 Sea cucumbers of different color morphs

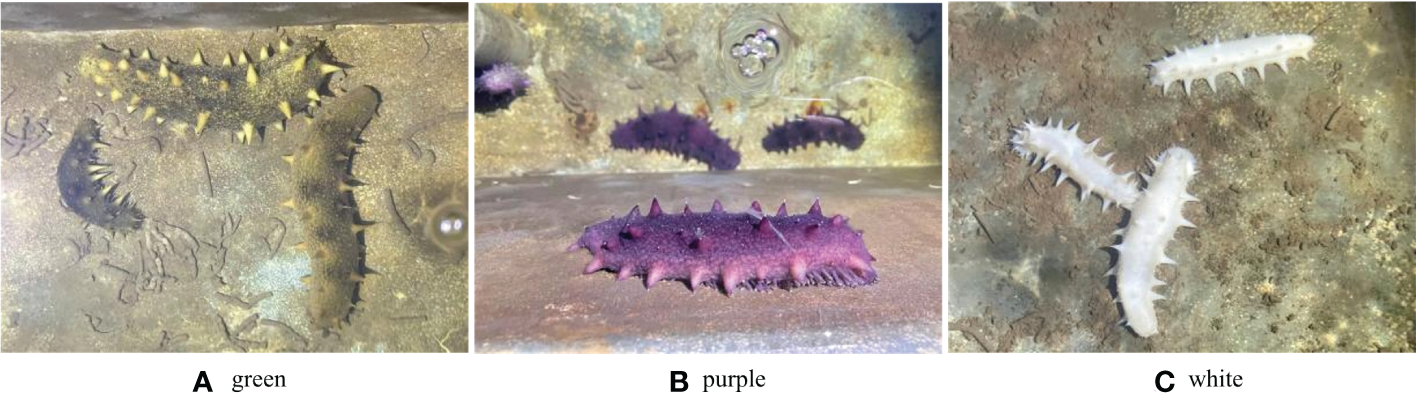

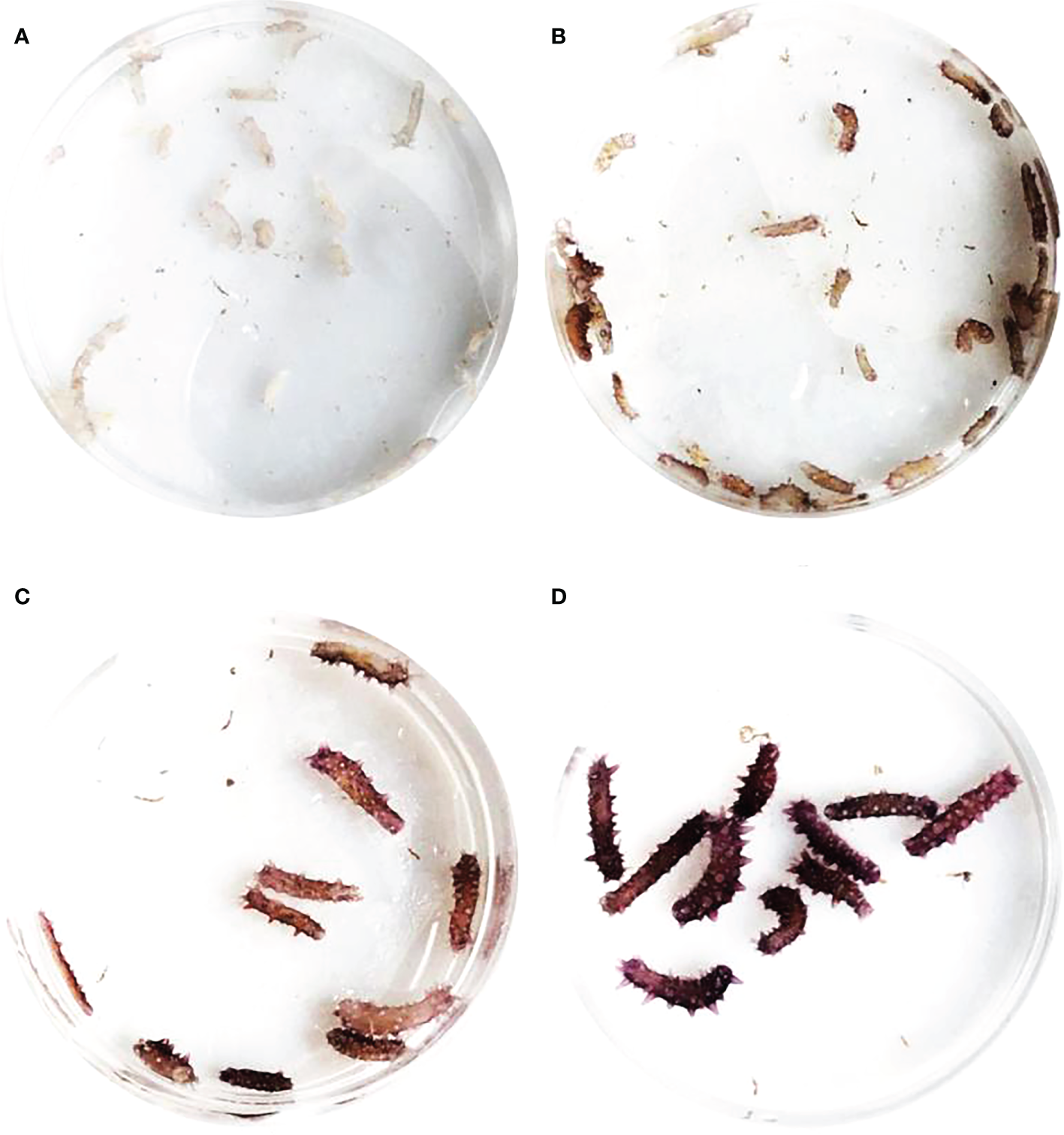

Healthy sea cucumbers aged 2 years and weighing 120 ± 10 g were collected from green, purple, and white cultivated populations (Figure 1). The purple and white morphs are genetically stable and have been bred by our research team for nearly 20 years.

Figure 1

Green, purple and white A. japonicus.

2.2.2 Purple sea cucumber at different developmental stages

9 purple sea cucumbers with a body weight of >180 g were screened as the parent population. Artificial labor was stimulated by drying in the shade and running water (20.5°C). Male individuals were removed from the incubator immediately after ejaculation. All parents were removed when the egg density was 20–30 eggs/mL. Then, the water temperature was increased to 21.0 ± 0.2°C for incubation. During the incubation period, the incubator was agitated once an hour, and micro-aerated continuously for 24 h to ensure an even distribution of fertilized eggs. Marine red yeast was fed to early auricularia after hatching. When 10% to 20% of doliolaria formed, a corrugated plate frame after disinfection was placed as the attachment matrix. After the larvae were attached, they were gradually transitioned to artificial compound feed. The feeding amount was 0.5% to 2% of the body weight. Juveniles were randomly selected every 3 days after the larvae developed to pentactula and were placed in a Petri dish to observe the change in body color. The pigmentation stage was defined at the point at which 80% of individuals were completely pigmented.

2.3 mRNA expression of TGFβ signaling pathway genes mRNA in A. japonicas

9 body walls from each sample of different color morphs and purple sea cucumber at different developmental stages were peeled away carefully, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for subsequent total RNA extraction. Specific primers for BMP2/4, ACVR2A, Smad1, TGFβR2, Smad2/3, and grb2 (a housekeeping gene used as an internal reference) based on known A. japonicus sequences (Table 4) were designed using Oligo 7.0. Primers were synthesized by Invitrogen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). TRIzol Reagent was used to isolate total RNA from the body walls according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and contaminating genomic DNA was eliminated using RNase-free DNase (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The RNA samples were reverse-transcribed using the Prime Script RT-PCR Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Equal amounts of cDNA were used for real-time quantitative RT-PCR using in a PikoReal 96-well RT-PCR System (Thermo Scientific., Waltham, MA, USA). Amplification was performed in a total volume of 10 μL, containing 5 μL of 2× SYBR Green master Mix, 1 μL of diluted cDNA, 0.4 μL of each primer, and 3.2 μL of PCR-grade water. The PCR cycling conditions were 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 min. Each sample was run in triplicate along with the internal control gene (grb2). The PCR products were visualized on a UV-transilluminator after electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

Table 4

| Gene | Accession no. | Primer sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP2/4 | AB057451.1 | Forward | 5’- CCAAAAGGCAGAAAAGCA -3’ |

| Reverse | 5’- ACCCACAATGGCAAAGTC -3’ | ||

| ACVR2A | BSL78_25911 | Forward | 5’- ACAGAGAAGCGTGGTGAAG -3’ |

| Reverse | 5’- GGTAGTCATAGAGGGAGCCA -3’ | ||

| Smad1 | BSL78_15508 | Forward | 5’- ATTCTCCTTTACCAGTCCAGTT -3’ |

| Reverse | 5’- AGCCTTCTCCAGTTCTTCC -3’ | ||

| TβR2 | BSL78_06251 | Forward | 5’- GAGCCGAAAGAAGACAGAAC -3’ |

| Reverse | 5’- TATCGTAGAGGGAAGGACTCA -3’ | ||

| Smad 2/3 | BSL78_11878 | Forward | 5’- GCTACCGCCTCCATCTTT -3’ |

| Reverse | 5’- CCTCCATACTGTTGTCATTGG -3’ | ||

| grb2 | C112121_gl_il | Forward | 5’- ATCTTTCACATATTGCGAGCCAG -3’ |

| Reverse | 5’- ATGACCATTCCGATGCCCTAA -3’ | ||

Oligonucleotide primers for A. japonicus.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0, and all data were assessed using one-way ANOVA. Differences in means between groups were assessed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test for post hoc multiple comparisons. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Values of p < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

3 Results

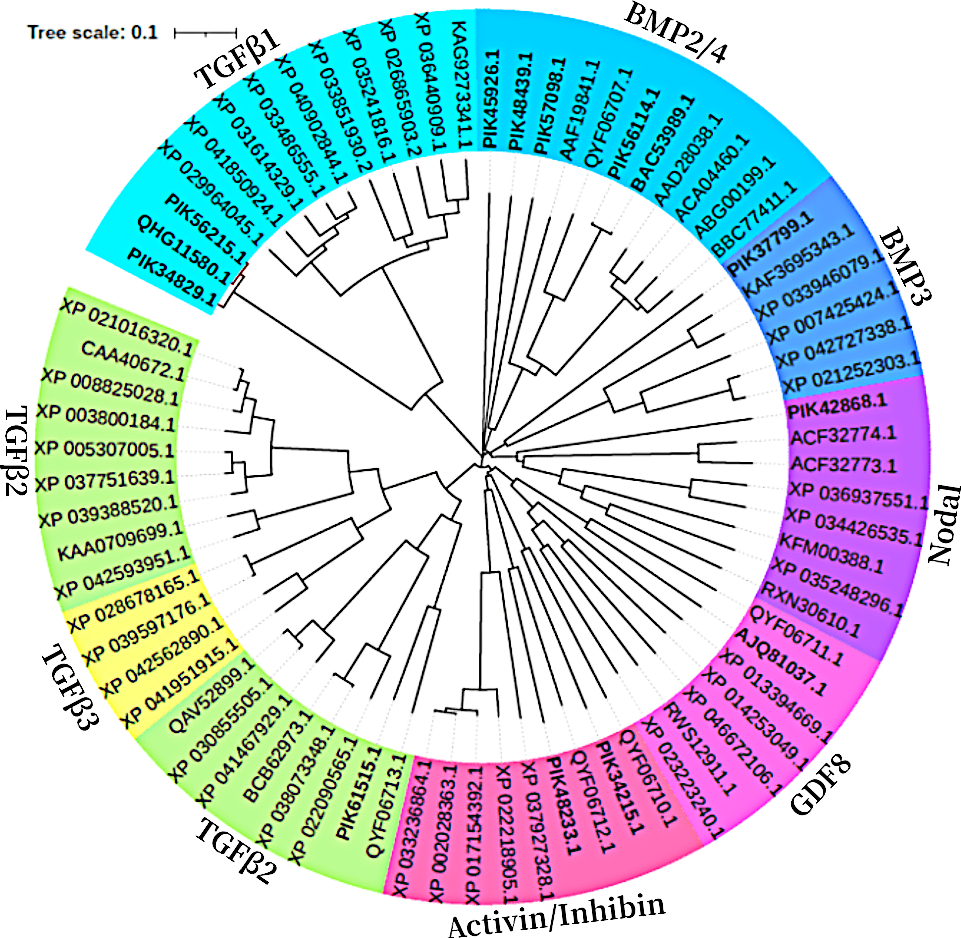

3.1 Phylogenetic analysis based on ligand sequences

In a phylogenetic tree based on amino acid sequences from multiple TGFβ ligands, the ligands of the same type formed clusters. The phylogenetic tree is shown in Figure 2 and the corresponding sequences are shown in Table 1. According to the phylogenetic tree, 14 known TGFβ ligands from A. japonicus were assigned to 7 classes: TGFβ1, TGFβ2, Nodal, Activin/Inhibin, BMP2/4, BMP3, and GDF8 (Growth Differentiation Factor 8, alternative name myostatin (de Caestecker, 2004)). Notably, TGFβ2 of A. japonicus was classified as TGFβ2 but was also closely related to TGFβ3. The BMP2/4 cluster contained BMP2A, BMP2, BMP, and Sj-BMP2/4 of A. japonicus. BMP3/3B of A. japonicus was classified into BMP3. Putative activin BX1 and putative inhibin beta C chain-like of A. japonicus were included in the Activin/Inhibin cluster.

Figure 2

Phylogenetic analysis of the 14 ligands proteins compared to other species.

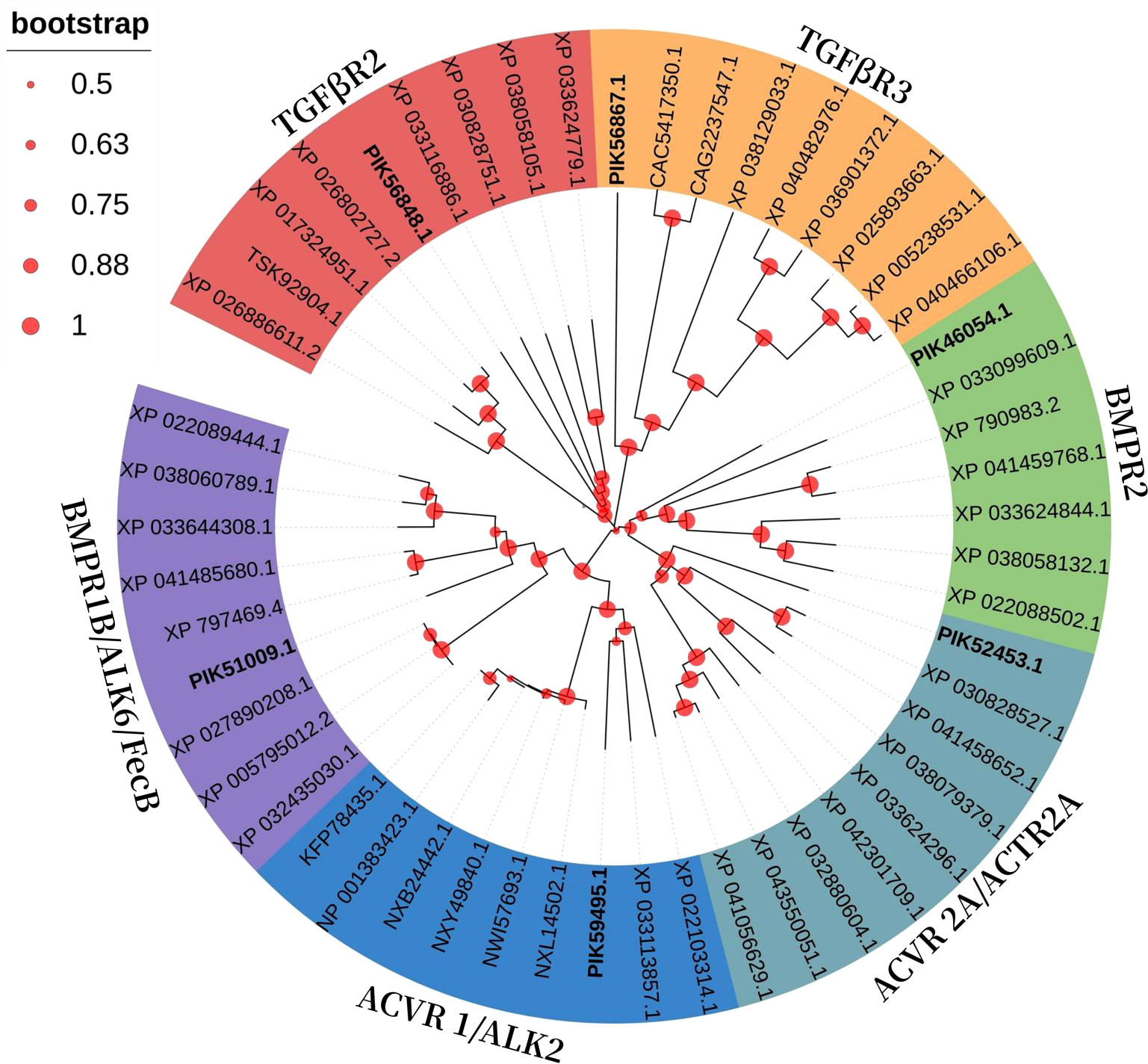

3.2 Phylogenetic analysis of receptors

In a phylogenetic tree based on amino acid sequences from multiple TGFβ receptors proteins, each type of receptor assembled in a cluster. The phylogenetic tree is shown in Figure 3 and corresponding sequences are shown in Table 2. According to the phylogenetic tree, six TGFβ receptors from A. japonicus were classified into six classes: TGFβR2 [transforming growth factor beta receptor 2, alternative name TβR2 (Hart et al., 2002)], TGFβR3 (transforming growth factor beta receptor 3, alternative name TβR3), BMPR1B [bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 1B, alternative name ALK6, FecB (Li et al., 2021)], BMPR2 (bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2), ACVR1 [activin receptor type 1, alternative name ACTR1, ALK2 (Lee et al., 2017)], and ACVR2A [activin receptor type 2A, alternative name ACTR2A (Bondulich et al., 2017)].

Figure 3

Phylogenetic analysis of the 6 receptors proteins compared to other species.

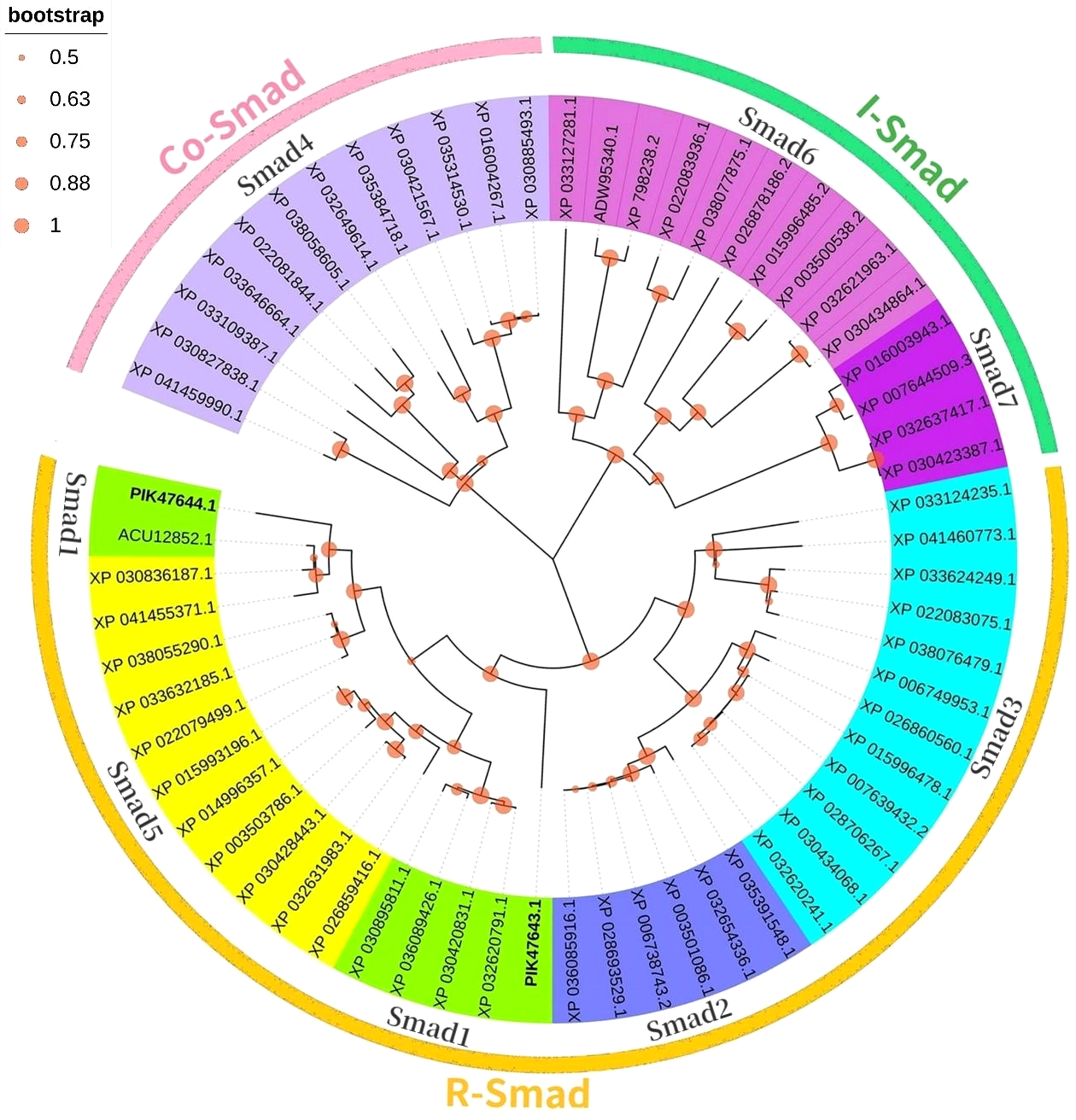

3.3 Phylogenetic analysis of Smads

In a phylogenetic tree based on amino acid sequences of multiple Smads, the each type of Smad assembled in a cluster. The phylogenetic tree is shown in Figure 4 and the corresponding sequences are shown in Table 3. According to the phylogenetic tree, two kinds of known R-Smads from A. japonicus were classified into one class, the Smad1 class. Notably, they were closely related to Smad5.

Figure 4

Phylogenetic analysis of the 2 Smads proteins compared to other species.

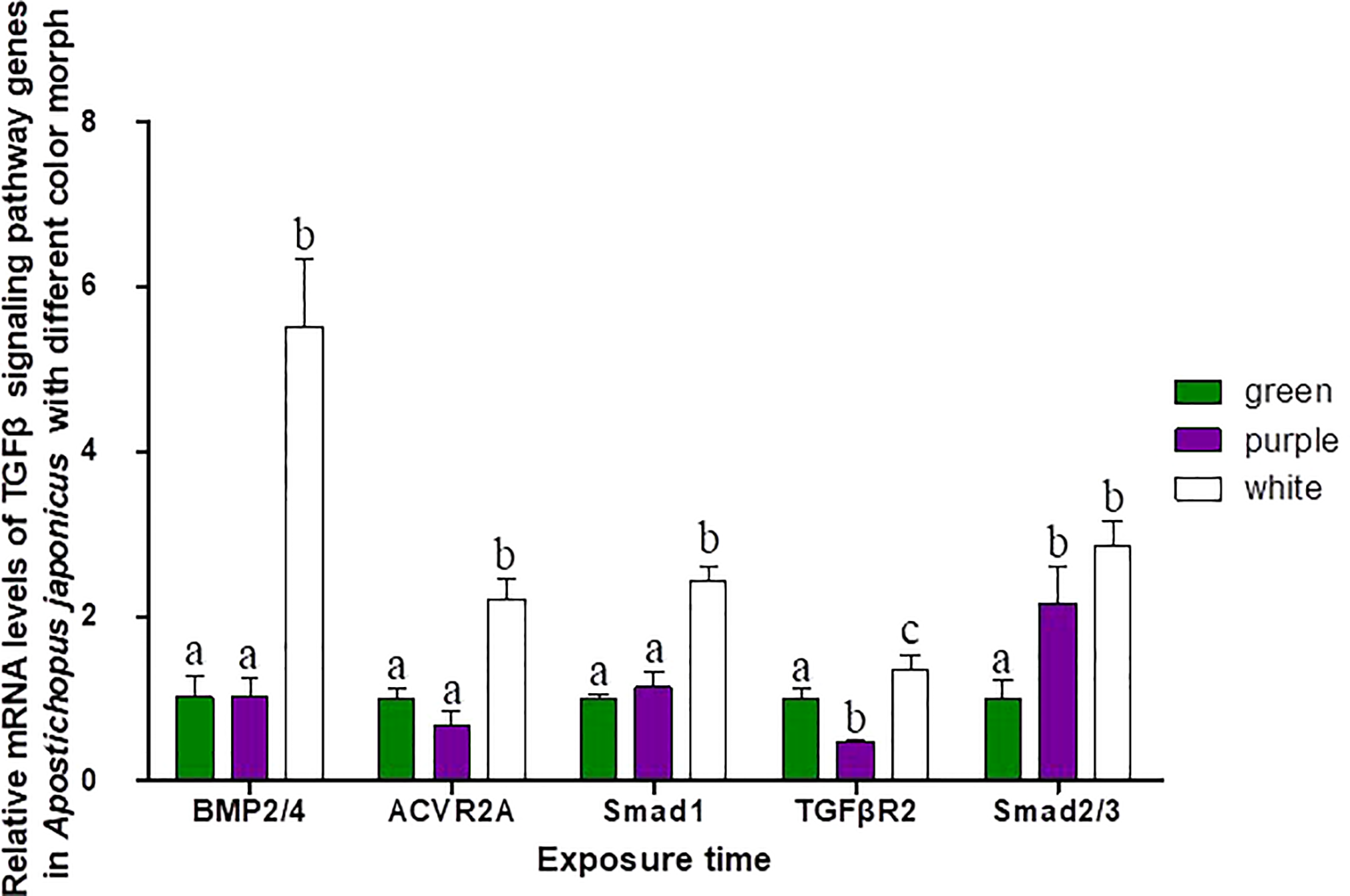

3.4 mRNA levels of TGFβ signaling pathway genes in A. japonicus color morphs

Three different color morphs of A. japonicus are shown in Figure 1. mRNA levels of TGFβ signaling pathway genes in A. japonicus with different colors are shown in Figure 5. Compared to levels in green A. japonicus, the mRNA expression levels of all TGFβ signaling pathway genes were much higher in purple A. japonicus, with significant differences in TGFβR2 and Smad2/3 levels between morphs (p < 0.05). The mRNA expression levels of BMP2/4, ACVR2A, Smad1, and TGFβR2 of the purple individuals were significantly lower than those in the white morph (p < 0.05), with no difference in Smad 2/3 (p > 0.05).

Figure 5

Relative mRNA levels of TGFβ signaling pathway genes in A. japonicus of different body colors. Means followed by different lower-case letters are significantly different at P<0.05.

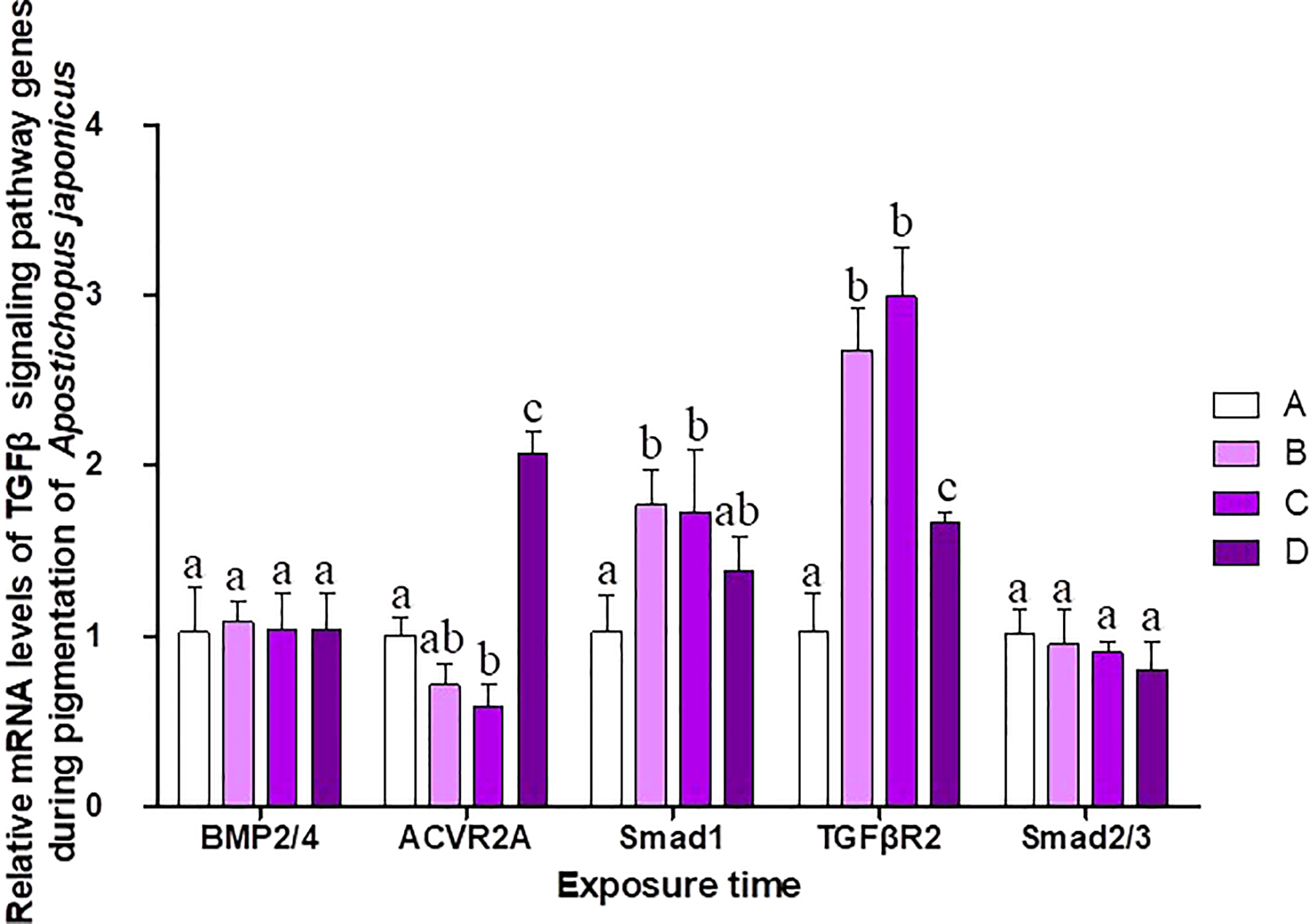

3.5 mRNA levels of TGFβ signaling pathway genes during pigmentation in A. japonicus

The pigmentation process in purple sea cucumber was divided into four stages: A, B, C, and D (Figure 6). mRNA levels of TGFβ signaling pathway genes at each stage are shown in Figure 7. BMP2/4 and Smad2/3 levels did not differ among pigmentation stages in A. japonicus (p > 0.05). Compared to levels at stage A, the mRNA expression of ACVR2A was lower at stage C and higher at stage D. The mRNA expression levels of Smad1 and TGFβR2 were significantly higher at stages B and C than at stage A. As time progressed, the expression level of TGFβR2 began to decrease, with lower levels at stage D than at stages B and C.

Figure 6

Pigmentation stages of purple A. japonicus.

4 Discussion

The TGFβ superfamily consists of over 50 structurally related ligands and can be divided into two subfamilies based on sequence similarity and the specific signaling pathways they activate: the TGFβ/activin/Nodal subfamily and BMP/GDF/AMH (anti-Mullerian hormone) subfamily (Shi and Massagué, 2003; Massagué, 2012; Miyazono et al., 2018). These have been described in a large number of studies of TGFβ superfamily ligand, receptor, and R-Smad interactions in various species (Piek et al., 1999; Attisano and Wrana, 2002; de Caestecker, 2004; Schilling et al., 2008; Romano et al., 2012) and were detected in the sea cucumber genome (Tables 1–3) . Ligand–receptor–R-Smad interactions in A. japonicus were inferred, as shown in Table 5, and putative TGFβ-mediated signaling pathways in A. japonicus are shown in Graphical Abstract. In the first subfamily, ligands (TGFβ1, TGFβ2, Activin B, Inhibin, and Nodal), Receptor II (TGFβR2 and ACVR2A/ACTR2A), and R-Smads (Smad2, 3) were found in A. japonicus. In the second subfamily, ligands (BMP2, BMP4, BMP3, and BMP3B), Receptor I (BMPR1B/ALK6), Receptor II (ACVR2A/ACTR2A and BMPR2), and R-Smad (Smad1, 5 and Smad2, 3) were found in A. japonicus.

Table 5

| Subfamily | Ligand | Receptor I | Receptor II | R-Smad |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ/activin/Nodal | TGFβ1 | no records | TGFβR2 | Smad2, 3 |

| TGFβ2 | no records | TGFβR2 | Smad2, 3 | |

| Activin B | no records | ACVR2A/ACTR2A | Smad2, 3 | |

| Inhibin | No type I receptor | ACVR2A | no specific R-Smads | |

| Nodal | no records | ACVR2A/ACTR2A | Smad2, 3 | |

| BMP/GDF/AMH | BMP2 | BMPR1B/ALK6 | ACVR2A/ACTR2A and BMPR2 | Smad1, 5 |

| BMP4 | BMPR1B/ALK6 | ACVR2A/ACTR2A and BMPR2 | Smad1, 5 | |

| BMP3 | No type I receptor | no records | no records | |

| BMP3B | no records | ACVR2A/ACTR2A | Smad2, 3 |

TGFβ superfamily ligand-receptor-Smad specificity.

The TGFβ signaling pathway is considered a good marker for the evolution of animal genomes (Long, 2019). Three TGFβ isoforms are known in mammals (Derynck et al., 1985; Van Obberghen-Schilling et al., 1987; ten Dijke et al., 1988; Miller et al., 1989a; Miller et al., 1989b) and in birds (TGFβ2, β3, and β4) (Jakowlew et al., 1988a; Jakowlew et al., 1988c; Jakowlew et al., 1988b; Jakowlew et al., 1990), two in amphibians (TGFβ2 and TGFβ5) (Kondaiah et al., 1990; Rebbert et al., 1990), and four in fish (TGFβ1, β2, β3 and β6) (Funkenstein et al., 2010). In the present study, two TGFβ ligand isoforms (TGFβ1 and TGFβ2) were identified in A. japonicus (Figure 2). A BLAST search against GenBank entries (putative TGFβ1 like, PIK34829.1, putative TGFβ1X1, PIK56215.1, and putative TGFβ1X1, QHG11580.1) revealed high amino acid sequence homology with TGFβ1 (Figure 2 and Table 1). It is worth noting that although TGFβ2 was classified as TGFβ2, it was closely related to TGFβ3 (Figure 2 and Table 1). Activin is the dimer of β-subunits, activin A (βA-βA), activin B (βB-βB), and activin AB (βA-βB). Inhibin A, B, C are dimers composed of an α-subunit associated with βA, βB, and βC (Burger, 1988; Mellor et al., 2000; Ushiro et al., 2006). Accordingly, the putative activin BX1 and putative inhibin beta C chain-like of A. japonicus clustered in the Activin/Inhibin cluster on the phylogenetic tree and showed a relatively low identity (Figure 2 and Table 1). The TGFβ family member nodal of A. japonicus were assigned to the Nodal cluster (Figure 2 and Table 1). In summary, sea cucumber possessed the complete TGFβ/activin/Nodal ligand subfamily.

Although no typical receptor I was found in the TGFβ/activin/Nodal subfamily (Table 5), significant differences in the mRNA expression levels of TGFβR2, ACVR2A, and Smad2/3 were detected in sea cucumbers with different body colors (Figure 5). Expression levels of TGFβR2 during different pigmentation stages of purple A. japonicus were significantly higher than those during the unpigmented period; however, the expression levels of Smad2/3 did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) (Figure 7). This indicates that TGFβR2 is involved in the regulation of the coloration process of A. japonicus; however, its specific regulatory mechanism is still unclear. TGFβR2 and Smad2/3 also differ significantly between peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and a normal control group (Sun et al., 2013). When ACVR2A function is reduced in melanocytes, gray hair develops (Han et al., 2012). These findings are consistent with the higher expression of ACVR2A in the white morph than in the other color morphs of A. japonicus. More broadly, there are ethnic differences in TGFβ signaling in African American and Caucasian skin (Fantasia et al., 2013). Taken together, these studies support the hypothesis that the TGFβ/activin/Nodal subfamily is involved in the regulation of body color of A. japonicas.

The second subfamily involved BMP/GDF/AMH. BMP is the largest subfamily of TGFβ ligands. In the current study, two BMPs, BMP2/4 and BMP3, were found. The BMPs (PIK57098.1) of A. japonicus were classified as BMP2/4. Sj-BMP2/4 was recorded in GenBank with two different accession numbers (PIK56114.1 and BAC53989.1). A Blast analysis showed that the two proteins were highly homologous (query cover: 100%, identity: 99.29%). A. japonicus and Stichopus japonicus are two different names for the same species (Chang et al., 2009). Accordingly, Sj-BMP2/4 corresponds to BMP2/4 of A. japonicus. In this study, the mRNA expression of BMP2/4 did not differ among pigmentation stages of purple A. japonicus (Figure 7). However, BMP2/4 expression was significantly higher in the white morph than in the green and purple morphs (Figure 5), suggesting that BMP2/4 is closely related to formation of the white body color. Numerous studies have shown that BMP2 and BMP4 can induce stem cells to differentiate into adipocytes and to differentiate into white adipocytes (Ahrens et al., 1993; Wang et al., 1993; Sottile and Seuwen, 2000; Bowers and Lane, 2007; Gomes et al., 2012). White sea cucumbers are uniformly white on the dorsal and ventral sides, while purple and green sea cucumbers have obvious color differences, i.e., the dorsal side is darker than the ventral side (Figures 1, 6). The specificity of BMP2/4 was receptor I (BMPR1B)–receptor II (ACVR2A and BMPR2)–R-Smad (Smad1,5). In A. japonicus, their expression levels in white sea cucumber were significantly higher than those in the purple and green sea cucumbers (Figure 5). These results suggest that the BMP2/4-induced differentiation of white adipocytes in A. japonicus is regulated by this signaling pathway. Functional tests, including gain- or loss-of-function assays, using exogenous BMPs or BMP antagonists are necessary to validate the roles of this pathway in A. japonicus. In the GDF gene family, only GDF8 was detected in A. japonicus (Figure 2 and Table 1). There was no record of AMH in sea cucumber. Accordingly, the BMP/GDF/AMH ligand subfamily in sea cucumber is incomplete.

Figure 7

Relative mRNA levels of TGFβ signaling pathway genes during different pigmentation stages of purple A. japonicus. Means followed by different lower-case letters are significantly different at P<0.05.

5 Conclusions

In summary, 14 TGFβ signaling pathway members were identified in A. japonicus for the first time, including 7 ligands, 6 receptors, and 1 R-Smad. Detailed phylogenetic and gene expression analyses support the hypothesis (Graphical Abstract) that both subfamilies of the TGFβ superfamily were involved in the regulation of pigmentation in different color morphs of A. japonicus. The TGFβ/activin/Nodal subfamily was complete and contributed to the regulation of different color morphs. The BMP/GDF/AMH subfamily was incomplete, and the BMP2/4-induced differentiation of white adipocytes was regulated by the BMP2/4–ACVR2A–Smad1 signaling pathway.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LY and CL conceived and designed the experiments. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by LY, BZ, QW, XJ, SH, WH. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LY and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2022QC183), Key R&D Plan of Shandong Province (2021TZXD008), National Key Research and Development Program “Blue Granary Scientific and Technological Innovation” (2018YFD0901602).

Conflict of interest

Author XJ was employed by the company Country Conson CSSC Qingdao Ocean Technology CO., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ahrens M. Ankenbauer T. Schröder D. Hollnagel A. Mayer H. Gross G. (1993). Expression of human bone morphogenetic proteins-2 or-4 in murine mesenchymal progenitor C3H10T½ cells induces differentiation into distinct mesenchymal cell lineages. DNA Cell Biol.12 (10), 871–880. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.871

2

Attisano L. Wrana J. L. (2002). Signal transduction by the TGF-β superfamily. Science296 (5573), 1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809

3

Bai Y. Zhang L. Xia S. Liu S. Ru X. Xu Q. et al . (2016). Effects of dietary protein levels on the growth, energy budget, and physiological and immunological performance of green, white and purple color morphs of sea cucumber, apostichopus japonicus. Aquaculture. 437, 297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.08.021

4

Bao J. (2008). Effects and mechanism of environment on growth of green and red sea cucumber, apostichopus japonicus (Ocean University of China).

5

Bondulich M. K. Jolinon N. Osborne G. F. Smith E. J. Rattray I. Neueder A. et al . (2017). Myostatin inhibition prevents skeletal muscle pathophysiology in huntington’s disease mice. Sci. Rep.7 (1), 1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14290-3

6

Bottjer D. J. Davidson E. H. Peterson K. J. Cameron R. A. (2006). Paleogenomics of echinoderms. Science.314 (5801), 956–960. doi: 10.1126/science.1132310

7

Bowers R. R. Lane M. D. (2007). A role for bone morphogenetic protein-4 in adipocyte development. Cell Cycle6 (4), 385–389. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.4.3804

8

Burger H. G. (1988). Inhibin: definition and nomenclature, including related substances. J. Endocrinol.117 (2), 159–160. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1170159

9

Cameron R. A. Kudtarkar P. Gordon S. M. Worley K. C. Gibbs R. A. (2015). Do echinoderm genomes measure up? Mar. Genomics22, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2015.02.004

10

Chang Y. Feng Z. Yu J. Ding J. (2009). Genetic variability analysis in five populations of the sea cucumber stichopus (Apostichopus) japonicus from China, Russia, south Korea and Japan as revealed by microsatellite markers. Mar. Ecol.30 (4), 455–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.2009.00292.x

11

Cheng K. C. (2008). Skin color in fish and humans: Impacts on science and society. Zebrafish5 (4), 237–242. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0577

12

Chen Y. Gao F. Liu G. Shao L. Shi G. (2007). The effects of temperature,salinity and light cycle on the growth and behavior of apostichopus japonicus. J. Fisheries China31 (5), 687–691. doi: 1000-0615(2007)05-0687-05

13

Chen J. Lv Z. Guo M. (2022). Research advancement of apostichopus japonicus from 2000 to 2021. Front. Mar. Sci., 1595. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.931903

14

de Caestecker M. (2004). The transforming growth factor-β superfamily of receptors. Cytokine Growth factor Rev.15 (1), 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.004

15

Derynck R. Jarrett J. A. Chen E. Y. Eaton D. H. Bell J. R. Assoian R. K. et al . (1985). Human transforming growth factor-β complementary DNA sequence and expression in normal and transformed cells. Nature316 (6030), 701–705. doi: 10.1038/316701a0

16

Fantasia J. Lin C. B. Wiwi C. Kaur S. Hu Y. Zhang J. et al . (2013). Differential levels of elastin fibers and TGF-β signaling in the skin of caucasians and African americans. J. Dermatol. Sci.70 (3), 159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.03.004

17

Funkenstein B. Olekh E. Jakowlew S. B. (2010). Identification of a novel transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β6) gene in fish: regulation in skeletal muscle by nutritional state. BMC Mol. Biol.11 (1), 1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-11-37

18

Gomes S. P. Deliberador T. M. Gonzaga C. C. Klug L. G. Oliveira L. Urban A. C. et al . (2012). Bone healing in critical-size defects treated with immediate transplant of fragmented autogenous white adipose tissue. J. Craniofacial Surg.23 (5), 1239–1244. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31825da9d9

19

Guo Z. Wang Z. Hou X. Zhang H. (2020). Comparative study on genetic structure of three color variants of the sea cucumber ( apostichopus japonicus) based on mitochondrial and ribosomal genes. J. Shandong Univ. ( Natural Science)55 (11), 7. doi: 10.6040/j.issn.1671-9352.0.2020.231

20

Hall M. R. Kocot K. M. Baughman K. W. Fernandez-Valverde S. L. Gauthier M. E. Hatleberg W. L. et al . (2017). The crown-of-thorns starfish genome as a guide for biocontrol of this coral reef pest. Nature544 (7649), 231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature22033

21

Han R. Beppu H. Lee Y. K. Georgopoulos K. Larue L. Li E. et al . (2012). A pair of transmembrane receptors essential for the retention and pigmentation of hair. Genesis50 (11), 783–800. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22039

22

Hart P. J. Deep S. Taylor A. B. Shu Z. Hinck C. S. Hinck A. P. (2002). Crystal structure of the human TβR2 ectodomain–TGF-β3 complex. Nat. Struct. Biol.9 (3), 203–208. doi: 10.1038/nsb766

23

Henning F. Jones J. C. Franchini P. Meyer A. (2013). Transcriptomics of morphological color change in polychromatic Midas cichlids. BMC Genomics14 (1), 171–171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-171

24

Hubbard J. K. Uy J. Hauber M. E. Hoekstra H. E. Safran R. J. (2010). Vertebrate pigmentation: from underlying genes to adaptive function. Trends Genet.26 (5), 231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.02.002

25

Jakowlew S. B. Dillard P. J. Kondaiah P. Sporn M. B. Roberts A. B. (1988a). Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid cloning of a novel transforming growth factor-beta messenger ribonucleic acid from chick embryo chondrocytes. Mol. Endocrinol. (Baltimore Md.)2 (8), 747–755. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-8-747

26

Jakowlew S. B. Dillard P. J. Sporn M. B. Roberts A. B. (1988b). Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid cloning of a messenger ribonucleic acid encoding transforming growth factor β 4 from chicken embryo chondrocytes. Mol. Endocrinol.2 (12), 1186–1195. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-12-1186

27

Jakowlew S. B. Dillard P. J. Sporn M. B. Roberts A. B. (1988c). Nucleotide sequence of chicken transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta 1). Nucleic Acids Res.16 (17), 8730. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.17.8730

28

Jakowlew S. B. Dillard P. J. Sporn M. B. Roberts A. B. (1990). Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid cloning of an mRNA encoding transforming growth factor-β2 from chicken embryo chondrocytes. Growth Factors2 (2), 123–133. doi: 10.3109/08977199009071499

29

Ji T. Dong Y. Dong S. (2008). Growth and physiological responses in the sea cucumber, apostichopus japonicus selenka: Aestivation and temperature. Aquaculture283 (1), 180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.07.006

30

Kang J. H. Yu K. H. Park J. Y. An C. M. Jun J. C. Lee S. J. (2011). Allele-specific PCR genotyping of the HSP70 gene polymorphism discriminating the green and red color variants sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus). J. Genet. Genomics38 (8), 351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2011.06.002

31

Kondaiah P. Sands M. J. Smith J. M. Fields A. Roberts A. B. Sporn M. B. et al . (1990). Identification of a novel transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta 5) mRNA in xenopus laevis. J. Biol. Chem.265 (2), 1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40162-2

32

Lapraz F. Duboc V. Thierry L. (2007). A genomic view of TGF-β signal transduction in an invertebrate deuterostome organism and lessons from the functional analyses of nodal and BMP2/4 during sea urchin development. Signal Transduction.7 (2), 187–206. doi: 10.1002/sita.200600125

33

Lee H. Chong D. C. Ola R. Dunworth W. P. Meadows S. Ka J. et al . (2017). Alk2/ACVR1 and Alk3/BMPR1A provide essential function for bone morphogenetic protein–induced retinal angiogenesis. Arteriosclerosis thrombosis Vasc. Biol.37 (4), 657–663. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308422

34

Li J. Liu J. Cao X. Wang F. Li J. Zheng L. et al . (2020). Effects of light intensity on growth, digestion and immunity of green, white and purple sea cucumber apostichopus japonicus selenka. J. Dalian Ocean Univ. 35 (02), 184–189. doi: 10.16535/j.cnki.dlhyxb.2019-057

35

Linton L. M. Birren B. W. Lander E. (2001). International human genome sequencing consortium. Nature409 (6822), 860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062

36

Li H. Xu H. Akhatayeva Z. Liu H. Lin C. Han X. et al . (2021). Novel indel variations of the sheep FecB gene and their effects on litter size. Gene767, 145176. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145176

37

Long J. (2019). Bioinformatic analysis of TGF-β signaling pathway members and their expression in Nile tilapia (Southwest University).

38

Lowe C. J. Clarke D. N. Medeiros D. M. Rokhsar D. S. Rokhsar J. (2015). The deuterostome context of chordate origins. Nature. 520 (7548), 456–465. doi: 10.1038/nature14434

39

Massagué J. (2012). TGFβ signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.13 (10), 616–630. doi: 10.1038/nrm3434

40

Massagué J. Chen Y. (2000). Controlling TGF-β signaling. Genes Dev.14 (6), 627–644. doi: 10.1101/gad.14.6.627

41

Mellor S. L. Cranfield M. Ries R. Pedersen J. Cancilla B. Kretser D. D. et al . (2000). Localization of activin βA-, β b-, andβ c-subunits in human prostate and evidence for formation of new activin heterodimers ofβ c-subunit. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.85 (12), 4851–4858. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7052

42

Miller D. A. Lee A. Matsui Y. Chen E. Y. Moses H. L. Derynck R. (1989a). Complementary DNA cloning of the murine transforming growth factor-β3 (TGFβ3) precursor and the comparative expression of TGFβ3 and TGFβ1 messenger RNA in murine embryos and adult tissues. Mol. Endocrinol.3 (12), 1926–1934. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-12-1926

43

Miller D. A. Lee A. Pelton R. W. Chen E. Y. Moses H. L. Derynck R. (1989b). Murine transforming growth factor-β2 cDNA sequence and expression in adult tissues and embryos. Mol. Endocrinol.3 (7), 1108–1114. doi: 10.1172/JCI67521

44

Miyazono K. Katsuno Y. Koinuma D. Ehata S. Morikawa M. (2018). Intracellular and extracellular TGF-β signaling in cancer: some recent topics. Front. Med.12 (4), 387–411. doi: 10.1007/s11684-018-0646-8

45

Patterson G. I. Padgett R. W. (2000). TGFβ-related pathways: roles in caenorhabditis elegans development. Trends Genet.16 (1), 27–33. doi: 10.1242/dev.00863

46

Piek E. Heldin C. Dijke P. T. (1999). Specificity, diversity, and regulation in TGF-β superfamily signaling. FASEB J.13 (15), 2105–2124. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.15.2105

47

Rebbert M. L. Bhatiadey N. Dawid I. B. (1990). The sequence of TGF-beta 2 from xenopus laevis. Nucleic Acids Res.18 (8), 2185. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.2185

48

Romano V. Raimondo D. Calvanese L. D’Auria G. Tramontano A. Falcigno L. (2012). Toward a better understanding of the interaction between TGF-β family members and their ALK receptors. J. Mol. modeling18 (8), 3617–3625. doi: 10.1007/s00894-012-1370-y

49

Schilling S. H. Hjelmeland A. B. Rich J. N. Wang X. (2008). 3 TGF-β: A multipotential cytokine. Cold Spring Harbor Monograph. Arch.50, 45–77. doi: 10.1101/087969752.50.45

50

Shi Y. Massagué J. (2003). Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. cell113 (6), 685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x

51

Signor P. W. Brett C. E. (1984). The mid-Paleozoic precursor to the mesozoic marine revolution. Paleobiology10 (2), 229–245. doi: 10.1017/S0094837300008174

52

Sodergren E. Weinstock G. M. Davidson E. H. Cameron R. A. Gibbs R. A. Angerer R. C. et al . (2006). The genome of the sea urchin strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Science314 (5801), 941–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1133609

53

Sottile V. Seuwen K. (2000). Bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal precursor cells in synergy with BRL 49653 (rosiglitazone). FEBS Lett.475 (3), 201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01655-0

54

Sun B. Tan Y. Hong X. Liu D. (2013). Expressions of TGFβR2 and Smad2 in peripheral lymphocytes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Pract. Med29 (8), 1255–1257. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-5725.2013.08.019

55

Sun J. Zhang Y. Xu T. Zhang Y. Mu H. Zhang Y. et al . (2017). Adaptation to deep-sea chemosynthetic environments as revealed by mussel genomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol.1 (5), 121. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0121

56

ten Dijke P. Hansen P. Iwata K. K. Pieler C. Foulkes J. G. (1988). Identification of another member of the transforming growth factor type beta gene family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.85 (13), 4715–4719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4715

57

ten Dijke P. Miyazono K. Heldin C.-H. (2000). Signaling inputs converge on nuclear effectors in TGF-β signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci.25 (2), 64–70. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01519-4

58

Ushiro Y. Hashimoto O. Seki M. Hachiya A. Shoji H. Hasegawa Y. (2006). Analysis of the function of activin betaC subunit using recombinant protein. J. Reprod. Dev. 52 (4), 487–495. doi: 10.1262/jrd.17110. 0604200034-0604200034.

59

Van Obberghen-Schilling E. Kondaiah P. Ludwig R. L. Sporn M. B. Baker C. C. (1987). Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid cloning of bovine transforming growth factor-β1. Mol. Endocrinol.1 (10), 693–698. doi: 10.1210/mend-1-10-693

60

Wang E. A. Israel D. I. Kelly S. Luxenberg D. P. (1993). Bone morphogenetic protein-2 causes commitment and differentiation in C3Hl0T1/2 and 3T3 cells. Growth factors9 (1), 57–71. doi: 10.3109/08977199308991582

61

Wang G. Zhu W. Li Z. Fu R. (2007). Effects of water temperature and salinity on the growth of apostichopus japonicus. Shandong Science.20 (3), 6–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-4026.2007.03.002

62

Weiss A. Attisano L. (2013). The TGFbeta superfamily signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip. Reviews: Dev. Biol.2 (1), 47–63. doi: 10.1002/wdev.86

63

Zhang X. Sun L. Yuan J. Sun Y. Gao Y. Zhang L. et al . (2017). The sea cucumber genome provides insights into morphological evolution and visceral regeneration. PloS Biol.15 (10), e2003790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003790

64

Zhao B. Hu W. Li C. Han S. (2018). Effects of temperature and salinity survival, growth, and coloration of juvenile apostichopus japonicus selenta. Oceanologia Limnologia Sin. 36 (5), 1835–1842. doi: 10.11693/hyhz20170800211

65

Zheng S. Long J. Liu Z. Tao W. Wang D. (2018). Identification and of TGF-β signaling pathway members in twenty-four animal species and expression in tilapia. Int. J. Mol. Sci.19 (4), 1154. doi: 10.3390/ijms19041154

66

Zhu H. Kong L. Li Q. Wang Y. Zhao Q. (2013). Effects of Salinity,Temperature and stocking density on the growth and srvival of white race Sea Cucumber(Apostichopus japonicus) larvae (Periodical of Ocean University of China). doi: 10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.2013.07.006

Summary

Keywords

TGFβ signaling pathway, regulatory mechanism, pigmentation, Apostichopus japonicas , gene family divergence

Citation

Yao L, Zhao B, Wang Q, Jiang X, Han S, Hu W and Li C (2023) Contribution of the TGFβ signaling pathway to pigmentation in sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus). Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1101725. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1101725

Received

18 November 2022

Accepted

09 January 2023

Published

02 February 2023

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Hongsheng Yang, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), China

Reviewed by

Yi Yang, Hainan University, China; Xinran Li, Foshan University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Yao, Zhao, Wang, Jiang, Han, Hu and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chenglin Li, lcl_xh@hotmail.com

This article was submitted to Global Change and the Future Ocean, a section of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.