Abstract

Introduction:

The Red Sea is a narrow rift basin characterized by latitudinal environmental gradients which shape the diversity and distribution of reef-dwelling organisms. Studies on Symbiodiniaceae associated with select hard coral taxa present species- specific assemblages and concordant variation patterns from the North to southeast Red Sea coast at depths shallower than 30 m. At mesophotic depths, however, algal diversity studies are rare. Here, we characterize for the first-time host-associated algal communities of a mesophotic specialist coral species, Leptoseris cf. striatus, along the Saudi Arabian Red Sea coast.

Methods:

We sampled 56 coral colonies spanning the eastern Red Sea coastline from the Northern Red Sea to the Farasan Banks in the South, and across two sampling periods, Fall 2020 and Spring 2022. We used Next Generation Sequencing of the ITS2 marker region in conjunction with SymPortal to denote algal assemblages.

Results and discussion:

Our results show a relatively stable coral species-specific interaction with algae from the genus Cladocopium along the examined latitudinal gradient, with the appearance, in a smaller proportion, of presumed thermally tolerant algal taxa in the genera Symbiodinium and Durusdinium during the warmer season (Fall 2020). Contrary to shallow water corals, our results do not show a change in Symbiodiniaceae community composition from North to South in this mesophotic specialist species. However, our study highlights for the first time that symbiont communities are subject to change over time at mesophotic depth, which could represent an important phenomenon to address in future studies.

Introduction

Zooxanthellate scleractinian corals rely on their interaction with photoautotrophic dinoflagellates of the family Symbiodiniaceae Fensome, Taylor, Norris, Sarjeant, Wharton and Williams, 1993 (Muscatine and Porter, 1977). The mutualistic interaction of Symbiodiniaceae with stony corals is essential for the functioning and persistence of tropical and subtropical coral reef ecosystems worldwide (LaJeunesse et al., 2018). Different Symbiodiniaceae can present different physiological responses to environmental stressors, such as photoprotection or thermal tolerance against temperature changes (Rowan, 2004; Sampayo et al., 2008; DeSalvo et al., 2010), which allow them to survive under different environmental conditions (Little et al., 2004; Suwa et al., 2008; Cantin et al., 2009; Jones and Berkelmans, 2011). The different physiological requirements of Symbiodiniaceae also influence the coral host distribution range (Rodriguez-Lanetty et al., 2001), their metabolic performance (Cooper et al., 2011a), and stress tolerance (Berkelmans and Van Oppen, 2006; Abrego et al., 2008; Howells et al., 2012). Most zooxanthellate corals are consequently restricted in their depth distribution to the photic zone (Dubinsky and Falkowski, 2011; Lesser et al., 2018; Tamir et al., 2019). However, some zooxanthellate coral species can be found in mesophotic conditions commonly associated with greater depths. These contribute to shaping the Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems (MCEs), i.e., tropical and subtropical light-dependent communities between approximately 30 m and 150 m in depth (Lesser et al., 2009; Hinderstein et al., 2010; Baker et al., 2016; Pyle and Copus, 2019).

Among the Scleractinia playing an essential role in MCEs, several species of the genus Leptoseris Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849, family Agariciidae Gray, 1847, are important constituents of the MCEs (Fricke et al., 1987; Hinderstein et al., 2010; Rooney et al., 2010; Kahng et al., 2014, 2017; Loya et al., 2019). Different Leptoseris species were reported from Indo-Pacific MCEs (see, for example, Fricke and Knauer, 1986; Kahng et al., 2010; Luck et al., 2013; Pochon et al., 2015; Rouzé et al., 2021). In the Red Sea, different authors addressed the physiology and the distribution of Leptoseris cf. striatus Saville Kent, 1871 (previously referred to as Leptoseris fragilis Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849, but see Benzoni, 2022) (Schlichter et al., 1985, 1986, 1994, 1997; Fricke et al., 1987; Schlichter and Fricke, 1991; Kaiser et al., 1993; Ferrier-Pagès et al., 2022). These studies demonstrated that L. cf. striatus is a depth-specialist coral species, living between 70 and 145 m depth (Fricke and Schuhmacher, 1983; Fricke and Knauer, 1986; Kaiser et al., 1993; Tamir et al., 2019). The mesophotic success of this species seems to reside in its morphological and physiological characteristics (Schlichter et al., 1985, 1986, 1988, 1994, 1997; Fricke et al., 1987; Schlichter and Fricke, 1991). Fricke et al. (1987) hypothesized that L. cf. striatus conical knobs and plate-light growth forms would act as coral “light traps.” Furthermore, Schlichter et al. (1985, 1986, 1988) and Schlichter and Fricke (1991) reported that in this species, fluorescent proteins beneath zooxanthellae promote photosynthesis by shifting low-wavelength irradiance into long wavelengths within the action spectrum for photosynthesis (i.e., host light-harvesting system). The host light-harvesting system amplifies and increases the zooxanthellae’s photosynthetic efficiency and the coral host’s metabolic efficiency under low-light conditions (Schlichter et al., 1985, 1986, 1988; Schlichter and Fricke, 1991). Moreover, Fricke et al. (1987) demonstrated the inability of this species to grow shallower than 40 meters when transplanted, further reinforcing the idea that L. cf. striatus is an obligate mesophotic coral. In particular, the efficient host light-harvesting system mentioned above (Schlichter et al., 1986) is partially destroyed at depths shallower than 40 m, impeding growth (Fricke et al., 1987). Fricke et al. (1987) also reported that the Symbiodiniaceae density associated with L. cf. striatus decreases with depth. However, the diversity of the zooxanthellae community associated with the mesophotic specialist L. cf. striatus remains unstudied, hence the role of the symbiont’s identity and their variation in space and time, or lack thereof, is unknown.

The Red Sea is a young rift basin characterized by strong latitudinal environmental gradients in water temperature and salinity, which change from the North to the South (Sofianos and Johns, 2003; Raitsos et al., 2013; Rowlands et al., 2014, 2016; Chaidez et al., 2017; Manasrah et al., 2019; Berumen et al., 2019a). These conditions influence the diversity, distribution, and evolution of the Red Sea reef-dwelling marine organisms (Berumen et al., 2019a). A total of 331 zooxanthellate coral species are reported from the basin from shallow to mesophotic (see Arrigoni et al., 2019; Berumen et al., 2019b; Terraneo et al., 2019b, 2021), but a few studies focused on the characterization of their Symbiodiniaceae community composition to date (e.g., Winters et al., 2009; Nir et al., 2011, 2014; Byler et al., 2013; Ziegler et al., 2015; Einbinder et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2017; Ben-Zvi et al., 2020; Ferrier-Pagès et al., 2022; Terraneo et al., 2023). In fact, most studies addressed the Symbiodiniaceae diversity in different coral genera and species from the shallow, euphotic Red Sea water (shallower than 30 m) (Winters et al., 2009; Sawall et al., 2014; Arrigoni et al., 2016; Ezzat et al., 2017; Ziegler et al., 2017; Terraneo et al., 2019a; Hume et al., 2020; Osman et al., 2020; Terraneo et al., 2023). Two reports assessed the Symbiodiniaceae diversity of shallow-water corals along the Red Sea latitudinal gradient, reporting a correlation between the algae diversity and the environmental gradients along the basin, shown as a shift of algae community composition from North to South (Arrigoni et al., 2016; Terraneo et al., 2019a). In particular, the Red Sea species ascribed to the genus Stylophora Schweigger, 1820, and the genus Porites Link, 1807, presented a shift in algae community from North to South, passing from the genus Cladocopium LaJeunesse & H.J.Jeong, 2018 to the genus Symbiodinium Freudenthal, 1962, dominance and from the genus Cladocopium to the genus Durusdinium LaJeunesse, 2018 dominance, respectively (Arrigoni et al., 2016; Terraneo et al., 2019a). At mesophotic depths, however, zooxanthellae diversity studies are mostly limited to the Eilat coast of the Gulf of Aqaba (Winters et al., 2009; Nir et al., 2011, 2014; Byler et al., 2013; Einbinder et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2017; Ben-Zvi et al., 2020; Ferrier-Pagès et al., 2022), comprising one study from the NEOM region in the Northern Red Sea (Terraneo et al., 2023), and one study from the central Saudi Arabian Red Sea (Ziegler et al., 2015). Most of these studies focused on a few coral model species. Conversely, the composition and zonation of MCEs Symbiodiniaceae associated with a Red Sea non-model coral species, such as L. cf. striatus, and the community variation along the Red Sea latitudinal gradient are still mainly unknown.

With the overall aim to (a) characterize the composition of the Symbiodiniaceae community in the strictly mesophotic L. cf. striatus along the Red Sea latitudinal gradient and (b) investigate if symbiont communities are subject to change over time in the Gulf of Aqaba and the North Red Sea (NEOM area), we used Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) of the ITS2 amplicon from 56 colonies of L. striatus collected from five distinct regions of the Saudi Arabian Red Sea, spanning from the northern Red Sea (NEOM area) to the South of the Red Sea, as part of an unprecedented sampling effort to characterize the country’s marine resources.

Materials and methods

Coral sampling

A total of 56 L. cf. striatus colonies were collected during the Red Sea Deep Blue Expedition in October and November 2020 (15 colonies), the Red Sea Decade Expedition from February to June 2022 (32 colonies), and the OceanX Relationships Cultivation Expedition in June 2022 (9 colonies) on board the M/V OceanXplorer along the Saudi Arabian Red Sea coast (Appendix S1). Sampling occurred in regions spanning the whole latitudinal range of the Saudi Arabian coast from the Gulf of Aqaba (GoA) (4 sites) and northern Red Sea (NRS) (8 sites) in NEOM waters to the Al Wajh region (AlW) (4 sites), central Red Sea (CRS) (namely Yanbu and Thuwal) (10 sites) and southern Red Sea (SRS) (4 sites) (Appendix S2). The two distinct sampling regions in NEOM waters were sampled both in Fall 2020 and in Spring 2022, thus allowing us to investigate the Symbiodiniaceae community composition stability across time and between two seasons.

The entire coral colonies, or fragments, were collected between 70 and 127 m water depth using an Argus Mariner XL Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) or a Triton 3300/3 submersible with a Schilling T4 hydraulic manipulator. The ROV and the submersible dives were video-recorded, and frame grabs of the colonies were extracted from the videos using the open-source software MPC-HC (Media Player Classic – Home Cinema) and Adobe Premier software PRO™, respectively. The underwater vehicles position was provided by Kongsberg HIPaP 501 USBL (Ultra-Short Baseline), Sonardyne Sprin INS (Inertial Navigation System), and Sonardyne Ranger Pro 2 USBL.

After sampling, a small fragment of each colony, or the whole colony, was preserved in absolute ethanol for molecular analyses. The remaining part of the corallum was bleached in sodium hypochlorite for 48 hours to remove organic tissue parts, rinsed with fresh water, and air-dried for morphological identification. The coral skeletons and tissue samples are deposited at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST, Saudi Arabia).

Environmental data acquisition

Temperature, salinity, and depth at the sampling localities were recorded using a RBR Maestro CTD mounted on the ROV. Downcast RBR Maestro CTD data were extracted and visualized with Origin Pro 2020 (Origin Lab) software. Standard deviation (SD) was used as an uncertainty metric. RBR Maestro CTD raw data is available in Appendix S3.

Symbiodiniaceae MiSeq sequencing library preparation

Symbiodiniaceae genomic DNA was extracted from the coral tissues using the DNeasy® Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Symbiodiniaceae genotypes were characterized using PCR amplification of the ITS2 region for the Illumina MiSeq platform in the KAUST Bioscience Core Laboratory. The primer sequences were (overhang adapter sequences underlined): 5’ TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGAATTGCAGAACTCCGTGAACC 3’ (SYM_VAR_5.8S2) and 5’GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCGGGTTCWCTTGTYTGACTTCATGC 3’ (SYM_VAR_REV) (Hume et al., 2018). PCRs were run with 11 μL of 2X Multiplex PCR kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany), 2μL of 10 μM of each primer, and 5 μL of DNA, in a total volume of 25 μL. The following PCR conditions were used: 15 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 90 s, 72°C or 30 s, and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. PCRs success was tested with QIAxcel Advanced System (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). Amplified samples were cleaned with Agencourt AMPPure CP magnetic bead system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Nextera XT indexing and sequencing adapters were added via PCR (8 cycles) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were normalized and pooled using SequalPrep™ Normalization Plate Kit 96-well (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The samples were then checked with Aligen BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and qPCR (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to check library size and concentration. Libraries were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and kit reagents v3 (2 x 300bp pair-ended reads) at KAUST Bioscience Core Lab, following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Symbiodiniaceae MiSeq data processing

Demultiplexed forward and reverse fastq.gz files were submitted online to the SymPortal framework (https://symportal.org; Hume et al., 2019). A standardized quality control (QC) of sequences was conducted as part of the submissions using mothur 1.39.5 (Schloss et al., 2009), the BLAST+ suite of executables (Camacho et al., 2009), and Minimum Entropy Decomposition (MED; Eren et al., 2015; Hume et al., 2019). Then, existing sets of ITS2 sequences on the database were used to find and assign ITS2 profiles to samples. The Symbiodiniaceae genotypes are represented as proxies by the ITS2 profile predictions in the SymPortal outputs. The online framework was used to download the post-MED ITS2 sequence relative abundances (Appendix S4), the ITS2 profiles relative abundances (Appendix S5), and the corresponding absolute counts between sample distances and between profile distances. We created stacked bar plots to relate the Symbiodiniaceae genotypes to different categorical levels (i.e., body of water, sampling depth) with the R package ggplot2 (Wickham et al., 2016).

Comparison with Porites lutea and Porites columnaris in the Red Sea

The Symbiodiniaceae type profiles of Porites lutea Milne Edwards & Haime, 1851, and Porites columnaris Klunzinger, 1879, from Terraneo et al. (2019a), obtained through SymPortal submission, were taken into consideration for this study. In particular, patterns of specificity and generalism and comparison with algal communities of L. cf. striatus (this study) and P. lutea and P. columnaris (Terraneo et al., 2019a) were visualized using Venn Diagrams (Heberle et al., 2015).

Results

Coral identification

The scleractinian coral species studied in this work (Figure 1) belongs to the family Agariciidae in the complex clade (Kitahara et al., 2016). To date, it has not been studied from a molecular point of view and is currently synonymized with Leptoseris hawaiiensis Vaughan, 1907 (Hoeksema and Cairns, 2023). However, a morphological study of the type material of both species (illustrated in Dinesen, 1980) has shown consistent differences in corallite shape, size, and number of radial elements. Previous studies in the Red Sea addressing the physiology of this mesophotic specialist have identified it as Leptoseris fragilis (Schlichter et al., 1985, 1986, 1994, 1997; Fricke et al., 1987; Schlichter and Fricke, 1991; Kaiser et al., 1993; Ferrier-Pagès et al., 2022). However, Benzoni (2022) recently re-described the type material of L. fragilis and provided its first detailed description based on which all diagnostic characters based on skeletal morphology differ from the material we examined.

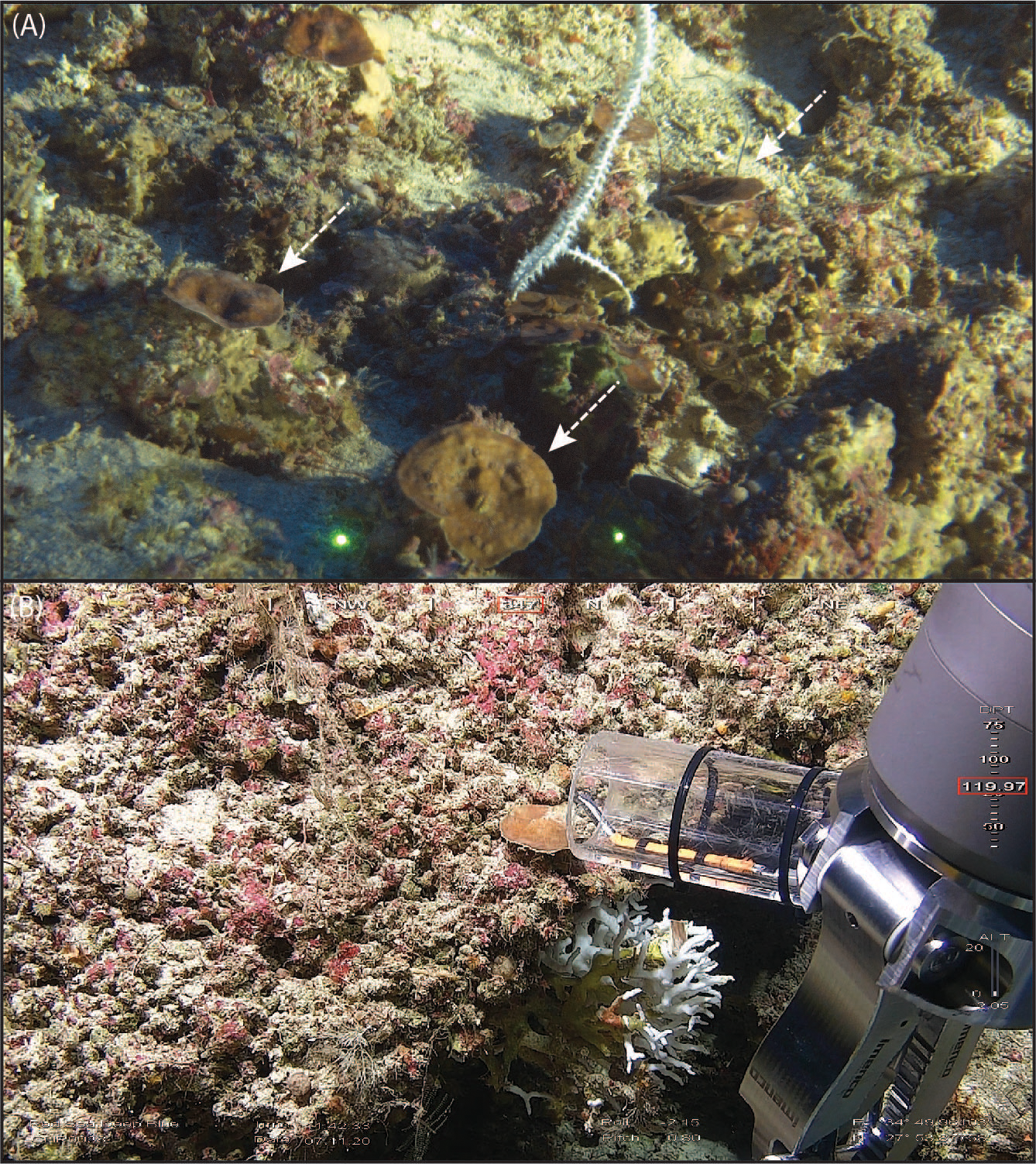

Figure 1

In situ pictures of some Leptoseris cf. striatus specimens analyzed in this study. (A) Different L. cf. striatus colonies (pointed with arrows) found during dive NTN0035. (B) Sampling of CHR0038_17.

Environmental parameters

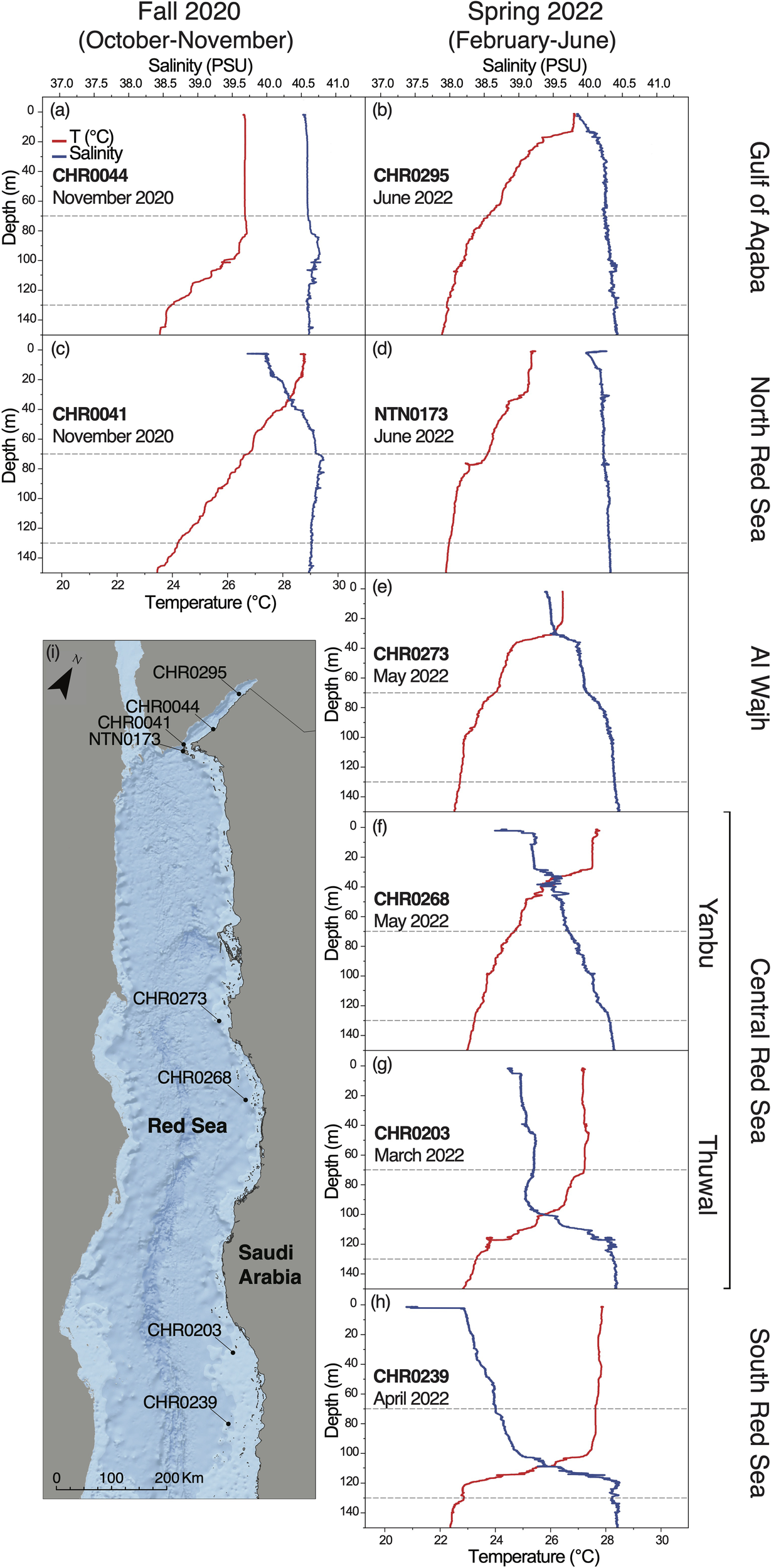

In Fall 2020, considering this study depth range of 70-130 m, the GoA and the NRS were comparable in terms of water temperature and salinity (25.9 ± 0.7 °C, 40.7 ± 0.05, respectively, for the GoA, and 25.5 ± 0.6 °C, 40.7 ± 0.04, respectively, for the NRS) (Figure 2; Appendix S3). In Spring 2022, the coolest and most saline basin was the GoA (22.9 ± 0.3 °C, 40.33 ± 0.04), followed by the NRS (23.05 ± 0.3 °C, 40.3 ± 0.02), AlW (23.1 ± 0.3 °C, 40.2 ± 0.09), Yanbu (23.8 ± 0.3 °C, 39.9 ± 0.1), Thuwal (25.2 ± 1.4 °C, 39.6 ± 0.5), and finally, SRS (25.8 ± 1.9 °C, 39.4 ± 0.6) (Figure 2; Appendix S3), with the temperature increasing from the North to the South, and the salinity decreasing along the North to South gradient, in agreement with the already known water seasonal and latitudinal gradient previously described from the basin (Sofianos and Johns, 2003; Raitsos et al., 2013; Rowlands et al., 2014, 2016; Chaidez et al., 2017; Berumen et al., 2019a; Manasrah et al., 2019).

Figure 2

Environmental parameters (temperature, and salinity) measured with the RBR CTD along the five regions we investigated during two different seasons, namely (A, B) Gulf of Aqaba, (C, D) North Red Sea, (E) Al Wajh, (F, G) Central Red Sea (Yanbu and Thuwal), (H) South Red Sea. The depth range focused in this study (70-130 m) is highlighted with grey dashed-lines. Temperature profile is in red and salinity profile is in blue. (I) Map of the Saudi Arabian Red Sea showing RBR CTD sampling sites. ESRI World Oceans Basemap, source: Esri, GEBCO, NOAA, National Geographic, DeLorme, HERE, Geonames.org, and other contributors.

Symbiodiniaceae community diversity

A total of 6,876,798 sequences were produced using Illumina MiSeq and then submitted to the SymPortal. The post-MED output included 75 different ITS2 sequences associated with L. cf. striatus. Of these, 12 belonged to the genus Symbiodinium, 60 to the genus Cladocopium, and three to the genus Durusdinium. Durusdinium was only recorded during Spring 2022 in the North and South Red Sea, while Symbiodinium and Cladocopium were found all along the Saudi Arabian Red Sea coast. Overall, in the 56 coral samples examined, the genus Symbiodinium represented 2.6% of the Symbiodiniaceae community, the genus Cladocopium 97.1%, and the genus Durusdinium 0.02% (Appendices S5, S6).

A total of 17 ITS2 profiles were recovered (Appendix S4). The ITS2 type profile composition per specimen was visualized using stacked bar charts to compare the relative abundance at each locality (Figure 3). Overall, the type profiles were not equally distributed among the samples, with 50/56 specimens interacting with two newly discovered ITS2 profiles (C1-C1cu-C1me-C42dr-C1mf-C1db-C1mg-C1aq and C1-C1cu-C1me-C42dr-C1mf-C1db-C1mg-C89b), and 53/56 specimens associating with the C1 ITS2 majority sequences (Appendix S5). The A1 radiation was found in 14/56 specimens. The remaining profiles, found associated with single specimens, belonged to A11, C3/C3u, C39/C1, C116/C116f, C39, C3/C1, C3, and D4 radiations.

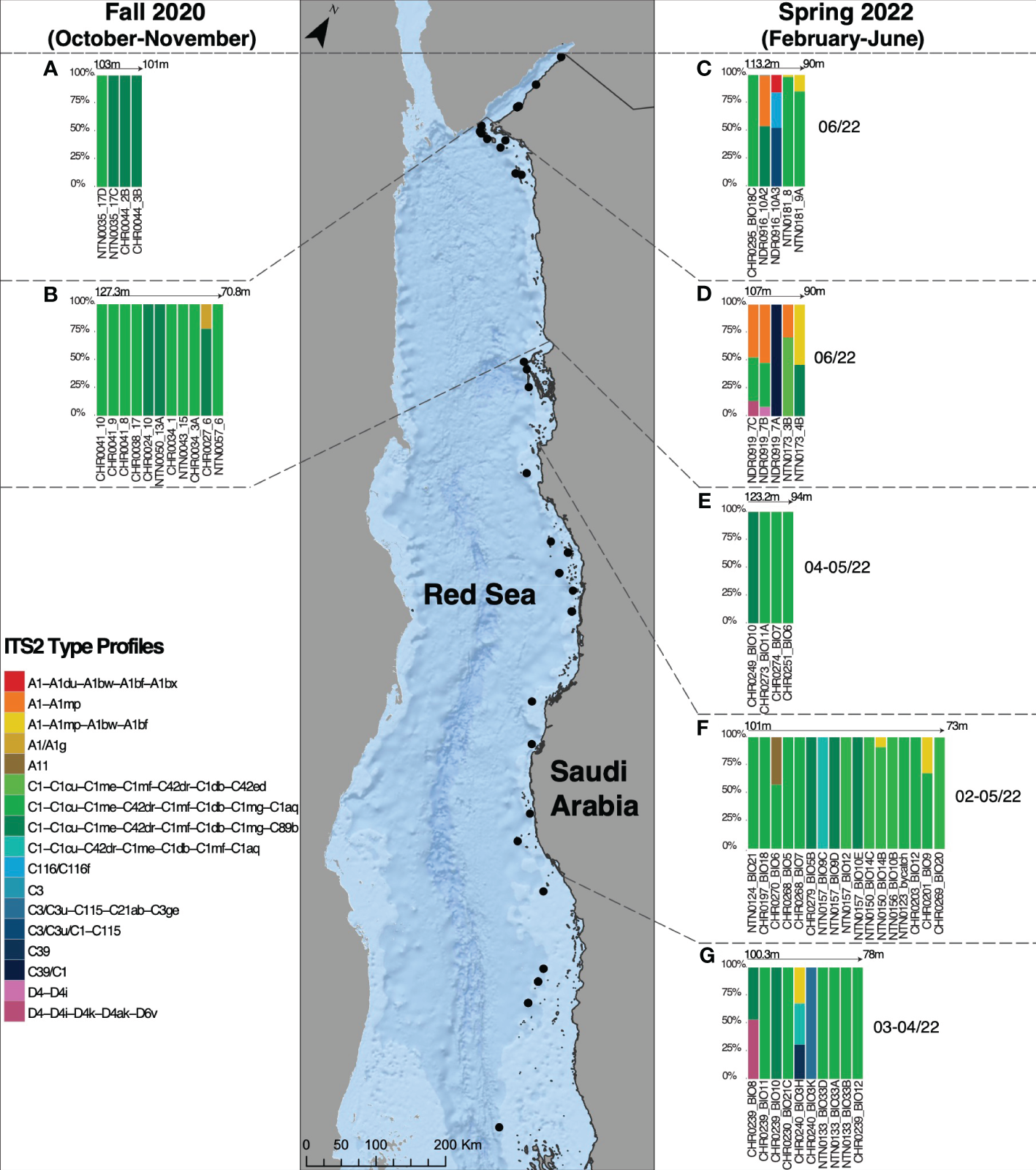

Figure 3

Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 type profiles in Leptoseris cf. striatus in the Gulf of Aqaba (A, C), in the North Red Sea (B, D), in Al Wajh (E), in the Central Red Sea (Yanbu and Thuwal) (F), and in the South Red Sea (G), found during two different sampling seasons, Fall 2020 (October-November) and Spring 2022 (February-June).

Overall, during Fall 2020, three ITS2 profiles were recorded, specifically C1-C1cu-C1me-C42dr-C1mf-C1db-C1mg-C1aq (9 colonies), C1-C1cu-C1me-C42dr-C1mf-C1db-C1mg-C89b (6 colonies), and A1/A11g (1 colony) (Figure 3). During Spring 2022, the ITS2 profiles C1-C1cu-C1me-C42dr-C1mf-C1db-C1mg-C1aq and C1-C1cu-C1me-C42dr-C1mf-C1db-C1mg-C89b were recovered in association with L. cf. striatus at all five examined regions, indicating high levels of specificity (Figure 3). The second most abundant type profile, retrieved from specimens collected in Spring 2022, A1-A1du-A1bw-A1bf, was associated with five colonies at four sampling localities (namely, GoA, NRS, CRS, and SRS) (Figure 3). The ITS2 profiles C116/C116f, C3/C3u/C1-C115, and C3 were found only in the GoA during the spring sampling collection (Figure 3). The type profiles A1-A1mp and A1-A1du-A1bw-A1bf-A1bx were recovered in the NEOM area (GoA and NRS) and only in the GoA, respectively, in Spring 2022 (Figure 3). Finally, the A11 type profile was associated with one Yanbu (CRS) sample in May 2022 (Figure 3). Considering the genus Durusdinium, during spring 2022, we recorded only two type profiles (D4-D4i-4k-D4ak-D6v and D4-D4i) associated with L. cf. striatus specimens (Figure 3). The first was associated with two samples in the NRS and SRS, while the latter was associated with one colony in the NRS (Figure 3).

In the different geographical regions that we identified, we also recovered colony-specific profiles, suggesting latitudinal and seasonal signatures (Figure 3). In the GoA, we recovered three specific ITS2 profiles belonging to the A1, C116, and C3 radiations (Figure 3). In the NRS, we found four ITS2 profiles, one found during Fall 2020 (A1/A1g) (Figure 3), and the remaining recovered only during Spring 2022, belonging respectively to A1, D4, C1, and C39 radiations (Figure 3). In the CRS (Yanbu and Thuwal), only one host-specific ITS2 profile was recorded, namely A11 (Figure 3). Finally, in the SRS, we found two ITS2 profiles belonging to the C3 and C39 radiations (Figure 3).

Unique and shared Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 type profiles of L. cf. striatus

Overall, two Symbiodiniaceae type profiles associated with L. cf. striatus were the most abundant and found at each analyzed site (Figures 3, 4). Of the remaining 15 type profiles, four were shared between pairs of regions (in particular, one between CRS and SRS; one between GoA and NRS; one between NRS and SRS; finally, one found in all four regions mentioned before) (Figures 3, 4), while 11 were only found associated at a specific region (Figures 3, 4).

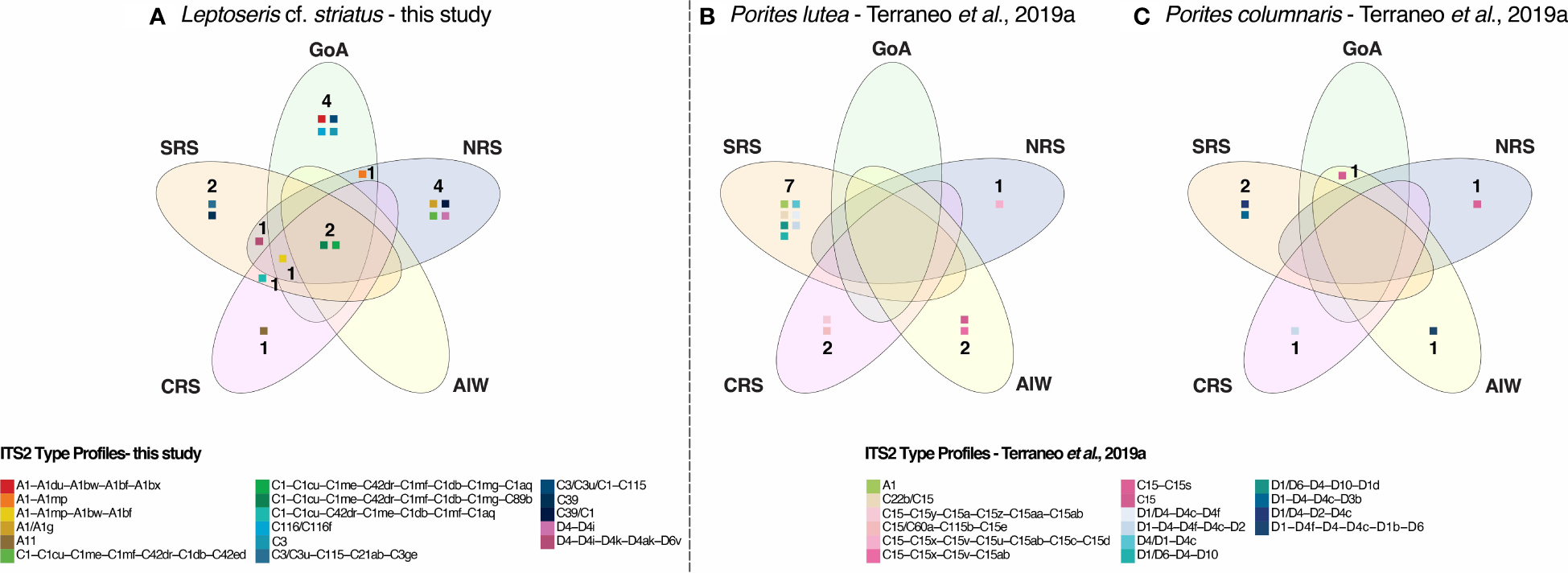

Figure 4

Venn diagrams comparing the unique and shared Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 type profiles of Leptoseris cf. striatus(A) from this study with the unique and shared Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 type profiles of Porites lutea(B) and Porites columnaris(C) from Terraneo et al. (2019a).

Discussion

In this work, we characterized for the first time the Symbiodiniaceae community diversity associated with the mesophotic-specialist coral L. cf. striatus, occurring from 70 to 127 m water depth along the Saudi Arabian Red Sea coast. Our measures of temperature and salinity at mesophotic depths showed a decrease in water temperature and an increase in salinity from North to South during Spring 2022. Conversely, in Fall 2020, at upper mesophotic depths, the temperature and the salinity of the Gulf of Aqaba and the Northern Red Sea were comparable (25.9 ± 0.7 °C and 40.7 ± 0.05, respectively, for the first and 25.5 ± 0.6 °C and 40.7 ± 0.04, respectively, for the latter). Then, to identify L. cf. striatus dominant zooxanthellae genotypes and compare their diversity throughout the study area, we performed Next Generation Sequencing of the ITS2 marker. Our results showed the presence of 17 Symbiodiniaceae type profiles associated with L. cf. striatus, with 2 of them being dominant in each sampling region.

Symbiodiniaceae genotypes at mesophotic depths

Zooxanthellate corals’ growth and survival are influenced by light availability, with consequent limitations on their depth distribution (Done, 2011; Muir et al., 2015). Understanding how zooxanthellate corals can survive in extreme environments, such as mesophotic waters, is still highly debated and is receiving increasing attention as technology improvements allow the exploration of previously inaccessible depths (Armstrong et al., 2019; Turner et al., 2019). Structural adaptation in macro and micro-morphological characters are commonly encountered in mesophotic corals in response to low-light availability, e.g., less self-shading (Ow and Todd, 2010), lower calical relief, or lower corallite density (Wijsman-Best, 1974; Willis, 1985; Carricart-Ganivet and Beltrán-Torres, 1993; Muko et al., 2000; Klaus et al., 2007). Moreover, the coral holobiont, particularly the associated Symbiodiniaceae community, can influence the host’s adaptability to such extreme environments. In the Red Sea, L. cf. striatus occurs in the lower mesophotic zone (70-145 m) (Fricke and Schuhmacher, 1983; Fricke and Knauer, 1986; Kaiser et al., 1993; Tamir et al., 2019; Ferrier-Pagès et al., 2022). Despite being considered a model species for research on coral physiology and ecology in mesophotic waters, its symbionts remain largely uncharacterized. Here, we provide the first assessment of the L. cf. striatus Symbiodiniaceae community. In agreement with previous works on different scleractinian taxa (Ezzat et al., 2017; Osman et al., 2020; Terraneo et al., 2023), we found in L. cf. striatus a Cladocopium-dominated community of zooxanthellae also consistent with Ziegler et al. (2017) who hypothesized a strong selection for this Symbiodiniaceae genus throughout the entire Arabian region (Osman et al., 2020).

Ziegler et al. (2015) collected different coral species between 1 and 60 meters along the Red Sea to understand the mechanisms behind the coral holobiont photoacclimatization at mesophotic depths. Their data suggested that the Symbiodiniaceae ITS2 type profiles play a role in the vertical distribution of corals. In particular, analysis of the zooxanthellae associated with coral samples revealed five distinct ITS2 sequences of known type profiles (C1, C3, C15, C39, D1a) (Ziegler et al., 2015). Similarly, our study reported an association between L. cf. striatus and the known type profiles A1, A11, C1, C116, C3, C39, and D4 radiations, with the Symbiodiniaceae community dominated by the C1 genotypes. Symbiodiniaceae type profile C1 was found to be associated with coral hosts ascribed to the genera Leptoseris and Seriatopora Lamarck, 1816, over different mesophotic depth ranges in other locations outside the Red Sea, e.g., Hawaii and Western Australia (Chan et al., 2009; Cooper et al., 2011b). The prevalence of Cladocopium genotypes in mesophotic species could be related to the ability of the genus to fix carbon under low-light environments (Ezzat et al., 2017). At the same time, different studies reported that the genus Durusdinium could be found in higher proportions during thermal stress than in normal environmental conditions (Stat et al., 2013; Cunning et al., 2015; Poquita-Du et al., 2020; Dilworth et al., 2021). We found Durusdinium genotypes associated with L. cf. striatus in the Northern and the Southern Red Sea in June and April 2022, during a season characterized by cooler sea temperatures. Different Symbiodiniaceae genotypes associated with stony corals are reported to cope differently with various environmental stressors (Silverstein et al., 2011, 2012; Rouzé et al., 2019). Certain corals can change symbiont proportions and Symbiodiniaceae species in response to different disturbances (Rowan, 2004; Berkelmans and Van Oppen, 2006). This ability has been shown to directly correlate with Symbiodiniaceae diversity within the host (Cunning et al., 2015; Rouzé et al., 2019). It is still unclear whether these adaptations similarly apply to L. cf. striatus. However, we hypothesized that the appearance of presumed thermal taxa in the genus Durusdinium in association with L. cf. striatus could be linked to environmental perturbation, such as exposure to cooler sea temperatures, a pattern already found in some colonies of Leptoria phrygia (Ellis and Solander, 1786) in Taiwan (Huang et al., 2020).

Algal symbiont specificity in the mesophotic Red Sea

The Red Sea is characterized by environmental gradients (Sofianos and Johns, 2003; Raitsos et al., 2013; Rowlands et al., 2014, 2016; Chaidez et al., 2017; Manasrah et al., 2019; Berumen et al., 2019a), which can shape the distribution of the Symbiodiniaceae along the Saudi Arabian coast in shallow (< 30 m) zooxanthellate corals (Berumen et al., 2019a). In fact, previous studies focusing on shallow-water corals reported a zooxanthellae community composition break along the Red Sea latitudinal gradient. For example, Terraneo et al. (2019a) characterized the Symbiodiniaceae community associated with different Porites species along the entire Saudi Arabian Red Sea. Their data showed a shift from the genus Cladocopium to the genus Durusdinium, going from the North to the South of the Red Sea, with the central Red Sea Porites harboring both genera. Similarly, Sawall et al. (2014) and Arrigoni et al. (2016) reported a shift from Cladocopium-dominated to Symbiodinium-dominated communities along the same Red Sea latitudinal gradient in the hard coral genus Pocillopora Lamarck, 1816 and Stylophora, respectively. Together, these results point to a relationship between the Red Sea environmental gradients and the Symbiodiniaceae biogeographical patterns in shallow water taxa.

In this study, when considering zooxanthellae patterns at the genus level, we did not find latitudinal differences in association with the strictly mesophotic L. cf. striatus, as the coral species presented Cladocopium-dominated communities all along the Saudi Arabian Red Sea coast, despite the presence of modest temperature and salinity gradients in the mesophotic layer, compared to stronger gradients in surface waters. Similar results were found by Terraneo et al. (2023) for the corals Coscinaraea monile (Forskål, 1775), Blastomussa merleti (Wells, 1961), Psammocora profundacella Gardiner, 1898, and Craterastrea levis Head, 1983, The authors, however, only compared colonies from the Gulf of Aqaba and the Northern Red Sea, thus a smaller latitudinal gradient than the one examined in this study, and focused on zooxanthellate species commonly mainly occurring at shallow depths with the notable exception of C. levis. This species, known to be exclusively living in low-light conditions (Benzoni et al., 2012), showed a lower Symbiodiniaceae diversity at mesophotic depths than the others and was associated with only one profile belonging to the C1 radiation in both the Gulf of Aqaba and the Northern Red Sea (Terraneo et al., 2023). Other studies reported Cladocopium-dominated communities in the mesophotic waters of the Gulf of Aqaba (Ezzat et al., 2017; Osman et al., 2020). In fact, there is no evidence of environmental gradients, which we confirm here for temperature and salinity along latitude, shaping symbionts distribution in the Red Sea mesophotic waters.

We compared the variability of L. cf. striatus zooxanthellae communities (Figure 4A) to the one previously published from the shallow water P lutea and P. columnaris sampled along the Red Sea latitudinal gradient (Terraneo et al., 2019a) (Figures 4B, C). In particular, the previously examined cases of the two shallow water Porites species showed a total of 16 different Symbiodiniaceae type profiles (Figure 4) and presented a latitudinal pattern, with only one type profile, C15, shared between the GoA and AlW in P. columnaris (Figure 4) (Terraneo et al., 2019a). Hence, the ITS2 type profiles associated with the Porites species in the euphotic zone were mostly host-generalist and associated with specific sampling localities. Moreover, both species showed a shift in the Symbiodiniaceae community from Cladocopium in the North to Durusdinium in the South. As a result, no type profile was shared among the different sampling areas in either species (Figures 4B, C). Conversely, the genotypes recovered in L. cf. striatus were mainly represented by the genus Cladocopium at all sites. Furthermore, our results show only five genotypes belonging to Symbiodinium and two belonging to Durusdinium, both occurring together with Cladocopium. As a result, L. cf. striatus shared the same two type profiles found in all regions along the Red Sea latitudinal gradient (Figure 4A). This suggests that for this mesophotic specialist coral, the Symbiodiniaceae community variability is not shaped by the same environmental gradients as in the shallow reef dwelling species.

Site and temporal partitioning of Leptoseris cf. striatus Symbiodiniaceae community

The five Saudi Arabian Red Sea regions we investigated were recently identified as four distinct bioregions based on phytoplankton phenology (Kheireddine et al., 2021). The Gulf of Aqaba is commonly considered a coral refuge and resilience area, with the coral communities able to persist through different disturbances and thermal stressors (Fine et al., 2013, 2019). This bioregion (3), together with the Northern and Central Red Sea (4) and the Southern Red Sea (2) bioregions, present a phytoplankton bloom during winter (October to March) and a recurrent summer phytoplankton boom peak (Raitsos et al., 2013; Kheireddine et al., 2021). Conversely, the Southern Red Sea bioregion (1, including the Farasan Banks and the Dahlak Archipelago) is characterized by a summer phytoplankton bloom starting at the end of May (Kheireddine et al., 2021). We sampled the Gulf of Aqaba and the Northern Red Sea in two different years, both supposedly concurrently with the reported phytoplankton bloom (October/November 2020 and June 2022). Our results did not reveal the presence of presumed thermal tolerant genotypes such as Durusdinium radiations during fall, when the sea water was warmer and less saline than in June 2022. Conversely, Symbiodinium and Durusdinium genotypes appeared in June 2022, when the seawater was cooler and more saline sea, indicating that some ecological variables related to temporal environmental changes could shape coral-zooxanthellae association at mesophotic depths. During Spring 2022, we reported a North-South gradient in water temperature and salinity in the mesophotic layer, less pronounced than those reported for surface waters (see Raitsos et al., 2013; Chaidez et al., 2017; Berumen et al., 2019a), in agreement with previous studies (Sofianos and Johns, 2003; Manasrah et al., 2019). In particular, the temperature increases from North to South while the salinity decreases, thus mirroring the shallow water gradient. However, all the remaining regions analyzed during Spring 2022 (namely Al Wajh, Central Red Sea, and Southern Red Sea) presented Cladocopium-dominated communities with more presumed thermally tolerant Symbiodiniaceae genotypes in one sample in the southern Red Sea, and not a shift on the Symbiodiniaceae community as shown in other Red Sea shallow water studies (Arrigoni et al., 2016; Terraneo et al., 2019a), indicating that the algal community of this mesophotic coral is consistent across the Red Sea latitudes. Moreover, different studies reported site and seasonal-specific acclimation signatures in corals (e.g., Brown et al., 1999; Fitt et al., 2001; Edmunds, 2009; Anthony et al., 2022; Sawall et al., 2022). However, processes other than seasonality (e.g., environmental stressors, thermal adaptation, host-symbiont specificity, and anthropogenic disturbances) (see, for example, Silverstein et al., 2012; Cunning et al., 2015; Terraneo et al., 2019a; Howe-Kerr et al., 2020; Claar et al., 2022); could drive the algal community shift in symbiotic corals. It is still unclear which processes made the algal community of L. cf. striatus change across 2 sampling time points. Hence, future studies encompassing longer sampling duration and sampling the same individual over time would be required to address whether seasonality or other processes play a role in the Symbiodiniaceae community composition of L. cf. striatus.

Conclusions

This study characterizes the composition and provides evidence for the limited variability of the Symbiodiniaceae community in a depth specialist coral species along a latitudinal gradient spanning approximately 1.300 km of coastline in the Saudi Arabian Red Sea. We found an increase in the mesophotic water temperature and a decrease in the salinity from the North to the South, in agreement with other studies from the basin. Moreover, contrary to shallow water corals, the Symbiodiniaceae communities associated with the strictly mesophotic coral Leptoseris cf. striatus were dominated by the same symbiont genus, Cladocopium, and type profile radiation, C1, across the entire Red Sea latitudinal gradient and a time span of 1.5 years, with the appearance, in a smaller proportion, of presumed thermally tolerant algal taxa in the genera Symbiodinium and Durusdinium during the colder water season (Spring 2022). Thus, we conclude the absence of a correlation between Red Sea environmental gradients and the L. cf. striatus-associated Symbiodiniaceae community in mesophotic waters of the basin, likely due to strong selection pressures for low-light adaptation. Our results open up questions about drivers of Symbiodiniaceae community changes at mesophotic depth and the need for more in-depth studies addressing the biology and ecology of scleractinian corals occurring in the mesophotic zone.

Statements

Data availability statement

The sequence data supporting this study's findings are openly available in GenBank of NCBI at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra. The associated **BioProject**, and **Bio-Sample** numbers are PRJNA994007, and SAMN36411768 to SAMN36411823 respectively. All the maps were created using ArcGIS® software by Esri. ArcGIS® and ArcMap™ are the intellectual property of Esri and are used herein under license. Copyright © Esri. All rights reserved. For more information about Esri® software, please visit www.esri.com. All data collected onboard during the Red Sea Decade Expedition (RSDE), including data collected by sensors, acoustic mapping devices, and images collected by ROVs and submersibles, are property of the National Center for Wildlife (NCW). The videos, images, and audio media obtained during the course of the RSDE are credited to the NCW, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions

SV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CC: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. FB: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. BH: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. FM: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MO: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – review & editing. CG: Writing – review & editing. AA: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. CRV: Validation, Writing – review & editing. MR: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. VP: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MQ: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SP: Writing – review & editing. BJ: Writing – review & editing. CD: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. FB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by KAUST (FCC/1/1973-49-01 and FCC/1/1973-50-01) and baseline research funds to FBe. The Red Sea Decade Expedition (RSDE) was funded by the National Center for Wildlife (NCW).

Acknowledgments

We thank NEOM for facilitating and coordinating the Red Sea Deep Blue expedition and, specifically, in addition to AAE, T. Habis, J. Myner, P. Marshall, G. Palavicini, P. Mackelworth, and A. Alghamdi. We thank the National Center for Wildlife (NCW, Saudi Arabia) for the invitation to participate in the Red Sea Decade Expedition. We thank M. Qurban, C. M. Duarte, J. E. Thompson, and N. C. Pluma Guerrero for facilitating and coordinating the Red Sea Decade Expedition. We thank M. Rodrigue and V. Pieribone for facilitating and coordinating the Red Sea Relationship Cultivation expedition. We want to thank OceanX and the crew of OceanXplorer for their operational and logistical support for the duration of this expedition. In particular, we would like to acknowledge the ROV and submersible teams for sample collection and OceanX for support of scientific operations on board OceanXplorer. We would also like to thank OceanX Media for documenting and communicating this work with the public. We also wish to thank A. Perry, N. Dunn, and S. Bahr for contributing to part of the sampling efforts. Finally, we thank the KAUST Genomics Core Lab for helping with NGS.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1264175/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abrego D. Ulstrup K. E. Willis B. L. van Oppen M. J. (2008). Species–specific interactions between algal endosymbionts and coral hosts define their bleaching response to heat and light stress. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.275, 2273–2282. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0180

2

Anthony C. J. Lock C. Taylor B. M. Bentlage B. (2022). Photosystem regulation in coral-associated dinoflagellates (Symbiodiniaceae) is the primary mode for seasonal acclimation. bioRxiv, 2022–2012. doi: 10.1101/2022.12.24.520888

3

Armstrong R. A. Pizarro O. Roman C. (2019). “Underwater robotic technology for imaging mesophotic coral ecosystems,” in Mesophotic coral ecosystems. Coral Reefs of the World, vol. vol. 12 . Eds. LoyaY.PugliseK.BridgeT. (Springer, Cham). doi: 10.1107/978-3-319-92735-0_51

4

Arrigoni R. Benzoni F. Terraneo T. I. Caragnano A. Berumen M. L. (2016). Recent origin and semi-permeable species boundaries in the scleractinian coral genus Stylophora from the Red Sea. Sci. Rep.6, 1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep34612

5

Arrigoni R. Berumen M. L. Stolarski J. Terraneo T. I. Benzoni F. (2019). Uncovering hidden coral diversity: a new cryptic lobophylliid scleractinian from the Indian Ocean. Cladistics35, 301–328. doi: 10.1111/cla.12346

6

Baker E. Thygesen K. Harris P. Andradi-Brown D. Appeldoorn R. S. Ballantine D. et al . (2016). Mesophotic coral ecosystems: a lifeboat for coral reefs? (Nairobi and Arendal: The United Nations Environment Programme and GRID-Arendal).

7

Benzoni F. (2022). Re-discovery of the type material of Leptoseris fragilis (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Scleractinia) from the upper mesophotic in La Réunion, a taxonomic puzzle. Zootaxa5178, 596–600. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.5178.6.8

8

Benzoni F. Arrigoni R. Stefani F. Stolarski J. (2012). Systematics of the coral genus Craterastrea (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Scleractinia) and description of a new family through combined morphological and molecular analyses. Syst. Biodivers.10 (4), 417–433. doi: 10.1080/14772000.2012.744369

9

Ben-Zvi O. Tamir R. Keren N. Tchernov D. Berman-Frank I. Kolodny Y. et al . (2020). Photophysiology of a mesophotic coral 3 years after transplantation to a shallow environment. Coral Reefs39, 903–913. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-01910-0

10

Berkelmans R. Van Oppen M. J. (2006). The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: a ‘nugget of hope’for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.273, 2305–2312. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3567

11

Berumen M. L. Arrigoni R. Bouwmeester J. Terraneo T. I. Benzoni F. (2019b). Corals of the Red Sea. Coral reefs red sea (Springer, Cham), 11, 123–155. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-05802-9_7

12

Berumen M. L. Voolstra C. R. Daffonchio D. Agusti S. Aranda M. Irigoien X. et al . (2019a). “The Red Sea: environmental gradients shape a natural laboratory in a nascent ocean,” in Coral reefs of the Red Sea (Springer, Cham), 1–10. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-05802-9_1

13

Brown B. E. Dunne R. P. Ambarsari I. Le Tissier M. D. A. Satapoomin U. (1999). Seasonal fluctuations in environmental factors and variations in symbiotic algae and chlorophyll pigments in four Indo-Pacific coral species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.191, 53–69. doi: 10.3354/meps191053

14

Byler K. A. Carmi-Veal M. Fine M. Goulet T. L. (2013). Multiple symbiont acquisition strategies as an adaptive mechanism in the coral Stylophora pistillata. PloS One8, e59596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059596

15

Camacho C. Coulouris G. Avagyan V. Ma N. Papadopoulos J. Bealer K. et al . (2009). BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinf.10, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421

16

Cantin N. E. van Oppen M. J. Willis B. L. Mieog J. C. Negri A. P. (2009). Juvenile corals can acquire more carbon from high-performance algal symbionts. Coral Reefs28, 405–414. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0478-8

17

Carricart-Ganivet J. P. Beltrán-Torres A. U. (1993). Zooxanthellae and chlorophyll a responses in the scleractinian coral Montastrea cavernosa at Triángulos-W Reef, Campeche Bank, Mexico. Rev. biología Trop., 491–494.

18

Chaidez V. Dreano D. Agusti S. Duarte C. M. Hoteit I. (2017). Decadal trends in Red Sea maximum surface temperature. Sci. Rep.7, 1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08146-z

19

Chan Y. L. Pochon X. Fisher M. A. Wagner D. Concepcion G. T. Kahng S. E. et al . (2009). Generalist dinoflagellate endosymbionts and host genotype diversity detected from mesophotic (67-100 m depths) coral Leptoseris. BMC Ecol.9, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-9-21

20

Claar D. C. McDevitt-Irwin J. M. Garren M. Vega Thurber R. Gates R. D. Baum J. K. (2022). Increased diversity and concordant shifts in community structure of coral-associated Symbiodiniaceae and bacteria subjected to chronic human distrubances. Mol. Ecol.29, 2477–2491. doi: 10.1111/mec.15494

21

Cooper T. F. Lai M. Ulstrup K. E. Saunders S. M. Flematti G. R. Radford B. et al . (2011a). Symbiodinium genotypic and environmental controls on lipids in reef building corals. PloS One6, e20434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020434

22

Cooper T. F. Ulstrup K. E. Dandan S. S. Heyward A. J. Kühl M. Muirhead A. et al . (2011b). Niche specialization of reef-building corals in the mesophotic zone: metabolic trade-offs between divergent Symbiodinium types. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.278, 1840–1850. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.2321

23

Cunning R. Silverstein R. N. Baker A. C. (2015). Investigating the causes and consequences of symbionts shuffling in a multi-partner reef coral symbiosis under environmental changes. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.282, 20141725. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1725

24

DeSalvo M. K. Sunagawa S. Voolstra C. R. Medina M. (2010). Transcriptomic responses to heat stress and bleaching in the elkhorn coral Acropora palmata. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.402, 97–113. doi: 10.3354/meps08372

25

Dilworth J. Caruso C. Kahkejian V. A. Baker A. C. Drury C. (2021). Host genotype and stable differences in algal symbiont communities explain patterns of thermal stress response of Montipora capitata following thermal pre-exposure and across multiple bleaching events. Coral Reefs40, 151–163. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-02024-3

26

Dinesen Z. D. (1980). A revision of the coral genus Leptoseris (Scleractinia: Fungiina: Agariciidae). Memoirs Queensland Museum20, 181–235.

27

Done T. (2011). “Corals: environmental controls on growth,” in Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series (Springer, Dordrecht),281–293. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2639-2_10

28

Dubinsky Z. Falkowski P. (2011). “Light as a source of information and energy in zooxanthellate corals,” in Coral reefs: an ecosystem in transition (Springer, Dordrecht), 107–118. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0114-4_8

29

Edmunds P. J. (2009). Effect of acclimatization to low temperature and reduced light on the response of reef corals to elevated temperature. Mar. Biol.156, 1797–1808. doi: 10.1007/s00227-009-1213-2

30

Einbinder S. Gruber D. F. Salomon E. Liran O. Keren N. Tchernov D. (2016). Novel adaptive photosynthetic characteristics of mesophotic symbiotic microalgae within the reef-building coral, Stylophora pistillata. Front. Mar. Sci.3. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00195

31

Eren A. M. Morrison H. G. Lescault P. J. Reveillaud J. Vineis J. H. Sogin M. L. (2015). Minimum entropy decomposition: unsupervised oligotyping for sensitive partitioning of high-throughput marker gene sequences. ISME J.9, 968–979. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.195

32

Ezzat L. Fine M. Maguer J. F. Grover R. Ferrier-Pages C. (2017). Carbon and nitrogen acquisition in shallow and deep holobionts of the scleractinian coral S. pistillata. Front. Mar. Sci.4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00102

33

Ferrier-Pagès C. Bednarz V. Grover R. Benayahu Y. Maguer J. F. Rottier C. et al . (2022). Symbiotic stony and soft corals: Is their host-algae relationship really mutualistic at lower mesophotic reefs? Limnol. Oceanogr.67, 261–271. doi: 10.1002/lno.11990

34

Fine M. Gildor H. Genin A. (2013). A coral reef refuge in the Red Sea. Global Change Biol.19, 3640–3647. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12356

35

Fine M. Gildor H. Voolstra C. R. Safa A. Rinkevich B. Laffoley D. et al . (2019). Coral reefs of the Red Sea – Challenges and potential solutions. Regional Stud. Mar. Sci.25, 100498. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2018.100498

36

Fitt W. K. Brown B. E. Warner M. E. Dunne R. P. (2001). Coral bleaching: interpretation of thermal tolerance limits and thermal thresholds in tropical corals. Coral Reefs20, 51–65. doi: 10.1007/s003380100146

37

Fricke H. W. Knauer B. (1986). Diversity and spatial pattern of coral communities in the Red Sea upper twilight zone. Oecologia71, 29–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00377316

38

Fricke H. W. Schuhmacher H. (1983). The depth limits of Red Sea stony corals: an ecophysiological problem (a deep diving survey by submersible). Mar. Ecol.4, 163–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.1983.tb00294.x

39

Fricke H. W. Vareschi E. Schlichter D. (1987). Photoecology of the coral Leptoseris fragilis in the Red Sea twilight zone (an experimental study by submersible). Oecologia73, 371–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00385253

40

Heberle H. Meirelles G. V. da Silva F. R. Telles G. P. Minghim R. (2015). InteractiVenn: a web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinf.16, 169. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0611-3

41

Hinderstein L. M. Marr J. C. A. Martinez F. A. Dowgiallo M. J. Puglise K. A. Pyle R. L. et al . (2010). Theme section on “Mesophotic coral ecosystems: characterization, ecology, and management”. Coral reefs29, 247–251. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0614-5

42

Hoeksema B. W. Cairns S. (2023) World List of Scleractinia. Leptoseris hawaiiensis Vaughan 1907 (World Register of Marine Species). Available online at: https://www.marinespecies.org/alphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=207291 (Accessed 2023-05-13).

43

Howe-Kerr L. I. Bachelot B. Wright R. M. Kenkel C. D. Bay L. K. Correa A. M. (2020). Symbiont community diversity is more variable in corals that respond poorly to stress. Glob. Change Biol.26, 2220–2234. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14999

44

Howells E. J. Beltran V. H. Larsen N. W. Bay L. K. Willis B. L. Van Oppen M. J. H. (2012). Coral thermal tolerance shaped by local adaptation of photosymbionts. Nat. Climate Change2, 116–120. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1330

45

Huang Y. Y. Carballo-Bolaños R. Kuo C. Y. Keshavmurthy S. Chen C. A. (2020). Leptoria phrygia in Southern Taiwan shuffles and switches symbionts to resist thermal-induced bleaching. Sci. Rep.10, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64749-z

46

Hume B. C. Mejia-Restrepo A. Voolstra C. R. Berumen M. L. (2020). Fine-scale delineation of Symbiodiniaceae genotypes on a previously bleached central Red Sea reef system demonstrates a prevalence of coral host-specific associations. Coral Reefs39, 583–601. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-01917-7

47

Hume B. C. Smith E. G. Ziegler M. Warrington H. J. Burt J. A. LaJeunesse T. C. et al . (2019). SymPortal: A novel analytical framework and platform for coral algal symbiont next-generation sequencing ITS2 profiling. Mol. Ecol. Resour.19, 1063–1080. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13004

48

Hume B. C. Ziegler M. Poulain J. Pochon X. Romac S. Boissin E. et al . (2018). An improved primer set and amplification protocol with increased specificity and sensitivity targeting the Symbiodinium ITS2 region. PeerJ6, e4816. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4816

49

Jones A. M. Berkelmans R. (2011). Tradeoffs to thermal acclimation: energetics and reproduction of a reef coral with heat tolerant Symbiodinium type-D. J. Mar. Biol. 2011, 8590. doi: 10.1155/2011/185890

50

Kahng S. E. Copus J. M. Wagner D. (2014). Recent advances in the ecology of mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs). Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain.7, 72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.019

51

Kahng S. Copus J. M. Wagner D. (2017). “Mesophotic coral ecosystems,” in Marine animal forests. Eds. RossiS.BramantiL.GoriA.OrejasC. (Springer, Cham). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-21012-4_4

52

Kahng S. E. Garcia-Sais J. R. Spalding H. L. Brokovich E. Wagner D. Weil E. et al . (2010). Community ecology of mesophotic coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs29, 255–275. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0593-6

53

Kaiser P. Schlichter D. Fricke H. W. (1993). Influence of light on algal symbionts of the deep water coral Leptoseris fragilis. Mar. Biol.117, 45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00346424

54

Kheireddine M. Mayot N. Ouhssain M. Jones B. H. (2021). Regionalization of the Red Sea based on phytoplankton phenology: a satellite analysis. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans126, e2021JC017486. doi: 10.1029/2021JC017486

55

Kitahara M. V. Fukami H. Benzoni F. Huang D. (2016). “The new systematics of Scleractinia: integrating molecular and morphological evidence,” in The Cnidaria, Past, Present and Future: The world of medusa and her sisters (Springer, Cham), 41–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-31305-4_4

56

Klaus J. S. Budd A. F. Heikoop J. M. Fouke B. W. (2007). Environmental controls on corallite morphology in the reef coral Montastraea annularis. Bull. Mar. Sci.80, 233–260.

57

LaJeunesse T. C. Parkinson J. E. Gabrielson P. W. Jeong H. J. Reimer J. D. Voolstra C. R. et al . (2018). Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol.28, 2570–2580. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.008

58

Lesser M. P. Slattery M. Leichter J. J. (2009). Ecology of mesophotic coral reefs. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.375, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2009.05.009

59

Lesser M. P. Slattery M. Mobley C. D. (2018). Biodiversity and functional ecology of mesophotic coral reefs. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst.49, 49–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062423

60

Little A. F. Van Oppen M. J. Willis B. L. (2004). Flexibility in algal endosymbioses shapes growth in reef corals. Science304, 1492–1494. doi: 10.1126/science.1095733

61

Loya Y. Puglise K. A. Bridge T. C. (Eds.) (2019). Mesophotic coral ecosystemsVol. 12 (New York: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92735-0

62

Luck D. G. Forsman Z. H. Toonen R. J. Leicht S. J. Kahng S. E. (2013). Polyphyly and hidden species among Hawai‘i’s dominant mesophotic coral genera, Leptoseris and Pavona (Scleractinia: Agariciidae). PeerJ1, e132. doi: 10.7717/peerj.132

63

Manasrah R. Abu-Hilal A. Rasheed M. (2019). “Physical and chemical properties of seawater in the Gulf of Aqaba and Red Sea,” in Oceanographic and biological aspects of the Red Sea (Springer, Cham), 41–73. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-99417-8_3

64

Muir P. R. Wallace C. C. Done T. Aguirre J. D. (2015). Limited scope for latitudinal extension of reef corals. Science348, 1135–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.1259911

65

Muko S. Kawasaki K. Sakai K. Takasu F. Shigesada N. (2000). Morphological plasticity in the coral Porites sillimaniani and its adaptive significance. Bull. Mar. Sci.66, 225–239.

66

Muscatine L. Porter J. W. (1977). Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. Bioscience27, 454–460. doi: 10.2307/1297526

67

Nir O. Gruber D. F. Einbinder S. Kark S. Tchernov D. (2011). Changes in scleractinian coral Seriatopora hystrix morphology and its endocellular Symbiodinium characteristics along a bathymetric gradient from shallow to mesophotic reef. Coral Reefs30, 1089–1100. doi: 10.1007/s00338-011-0801-z

68

Nir O. Gruber D. F. Shemesh E. Glasser E. Tchernov D. (2014). Seasonal mesophotic coral bleaching of Stylophora pistillata in the Northern Red Sea. PloS One9, e84968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084968

69

Osman E. O. Suggett D. J. Voolstra C. R. Pettay D. T. Clark D. R. Pogoreutz C. et al . (2020). Coral microbiome composition along the northern Red Sea suggests high plasticity of bacterial and specificity of endosymbiotic dinoflagellate communities. Microbiome8, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0776-5

70

Ow Y. X. Todd P. A. (2010). Light-induced morphological plasticity in the scleractinian coral Goniastrea pectinata and its functional significance. Coral Reefs29, 797–808. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0631-4

71

Pochon X. Forsman Z. H. Spalding H. L. Padilla-Gamiño J. L. Smith C. M. Gates R. D. (2015). Depth specialization in mesophotic corals (Leptoseris spp.) and associated algal symbionts in Hawai’i. R. Soc. Open Sci.2, 140351. doi: 10.1098/rsos.140351

72

Poquita-Du R. C. Huang D. Chou L. M. Todd P. A. (2020). The contribution of stress-tolerant endosymbiotic dinoflagellate Durusdinium to Pocillopora acuta survival in a highly urbanized reef system. Coral Reefs39, 745–755. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-01902-0

73

Pyle R. L. Copus J. M. (2019). “Mesophotic coral ecosystems: introduction and overview,” in Mesophotic coral ecosystems. Coral Reefs of the World, vol. vol. 12 . Eds. LoyaY.PugliseK.BridgeT. (Springer, Cham). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92735-0_1

74

Raitsos D. E. Pradhan Y. Brewin R. J. Stenchikov G. Hoteit I. (2013). Remote sensing the phytoplankton seasonal succession of the Red Sea. PloS One8, e64909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064909

75

Rodriguez-Lanetty M. Loh W. Carter D. Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2001). Latitudinal variability in symbiont specificity within the widespread scleractinian coral Plesiastrea versipora. Mar. Biol.138, 1175. doi: 10.1007/s002270100536

76

Rooney J. Donham E. Montgomery A. Spalding H. Parrish F. Boland R. et al . (2010). Mesophotic coral ecosystems in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Coral Reefs29, 361–367. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0596-3

77

Rouzé H. Galand P. E. Medina M. Bongaerts P. Pichon M. Pérez-Rosales G. et al . (2021). Symbiotic associations of the deepest recorded photosynthetic scleractinian coral (172 m depth). ISME J.15, 1564–1568. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-00857-y

78

Rouzé H. Lecellier G. Pochon X. Torda G. Berteaux-Lecellier V. (2019). Unique quantitative Symbiodiniaceae signature of coral colonies revealed through spatio-temporal survey in Moorea. Sci. Rep.9, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44017-5

79

Rowan R. (2004). Thermal adaptation in reef coral symbionts. Nature430, 742–742. doi: 10.1038/430742a

80

Rowlands G. Purkis S. Bruckner A. (2014). Diversity in the geomorphology of shallow-water carbonate depositional systems in the Saudi Arabian Red Sea. Geomorphology222, 3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.03.014

81

Rowlands G. Purkis S. Bruckner A. (2016). Tight coupling between coral reef morphology and mapped resilience in the Red Sea. Mar. pollut. Bull.105, 575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.11.027

82

Sampayo E. M. Ridgway T. Bongaerts P. Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2008). Bleaching susceptibility and mortality of corals are determined by fine-scale differences in symbiont type. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.105, 10444–10449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708049105

83

Sawall Y. Al-Sofyani A. Banguera-Hinestroza E. Voolstra C. R. (2014). Spatio-temporal analyses of Symbiodinium physiology of the coral Pocillopora verrucosa along large-scale nutrient and temperature gradients in the Red Sea. PloS One9, e103179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103179

84

Sawall Y. Nicosia A. M. McLaughlin K. Ito M. (2022). Physiological responses and adjustments of corals to strong seasonal temperature variations (20-28°C). J. Exp. Biol.225, jeb244196. doi: 10.1242/jeb.244196

85

Schlichter D. Fricke H. W. (1991). “Mechanisms of amplification of photosynthetically active radiation in the symbiotic deep-water coral Leptoseris fragilis,” in Hydrobiologia, vol. 216. (Kluwer Academic Publishers), 389–394). doi: 10.1007/BF00026491

86

Schlichter D. Fricke H. W. Weber W. (1986). Light harvesting by wavelength transformation in a symbiotic coral of the Red Sea twilight zone. Mar. Biol.91, 403–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00428634

87

Schlichter D. Fricke H. W. Weber W. (1988). Evidence for par-enhancement by reflection, scattering and fluorescence in the symbiotic deep-water coral Leptoseris fragilis (par= photosynthetically active radiation). Endocytobiosis Cell Res.5, 83–94.

88

Schlichter D. Kampmann H. Conrady S. (1997). Trophic potential and photoecology of endolithic algae living within coral skeletons. Mar. Ecol.18, 299–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.1997.tb00444.x

89

Schlichter D. Meier U. Fricke H. W. (1994). Improvement of photosynthesis in zooxanthellate corals by autofluorescent chromatophores. Oecologia99, 124–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00317092

90

Schlichter D. Weber W. T. Fricke H. W. (1985). A chromatophore system in the hermatypic, deep-water coral Leptoseris fragilis (Anthozoa: Hexacorallia). Mar. Biol.89, 143–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00392885

91

Schloss P. D. Westcott S. L. Ryabin T. Hall J. R. Hartmann M. Hollister E. B. et al . (2009). Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.75, 7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09

92

Silverstein R. N. Correa A. M. Baker A. C. (2012). Specificity is rarely absolute in coral–algal symbiosis: implications for coral response to climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.279, 2609–2618. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0055

93

Silverstein R. N. Correa A. M. LaJeunesse T. C. Baker A. C. (2011). Novel algal symbiont (Symbiodinium spp.) diversity in reef corals of Western Australia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.422, 63–75. doi: 10.3354/meps08934

94

Sofianos S. S. Johns W. E. (2003). An oceanic general circulation model (OGCM) investigation of the Red Sea circulation: 2. Three-dimensional circulation in the Red Sea. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans108, 17–1. doi: 10.1029/2001JC001184

95

Stat M. Pochon X. Franklin E. C. Bruno J. F. Casey K. S. Selig E. R. et al . (2013). The distribution of the thermally tolerant symbiont lineage (Symbiodinium clade D) in corals from Hawaii: correlations with host and the history of ocean thermal stress. Ecol. Evol.3, 1317–1329. doi: 10.1002/ece3.556

96

Suwa R. Hirose M. Hidaka M. (2008). Seasonal fluctuation in zooxanthellae genotype composition and photophysiology in the corals Pavona divaricata and P. decussata. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.361, 129–137. doi: 10.3354/meps07372

97

Tamir R. Eyal G. Kramer N. Laverick J. H. Loya Y. (2019). Light environment drives the shallow-to-mesophotic coral community transition. Ecosphere10, e02839. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2839

98

Terraneo T. I. Benzoni F. Arrigoni R. Baird A. H. Mariappan K. G. Forsman Z. H. et al . (2021). Phylogenomics of Porites from the Arabian Peninsula. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.161, 107173. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107173

99

Terraneo T. I. Benzoni F. Baird A. H. Arrigoni R. Berumen M. L. (2019b). Morphology and molecules reveal two new species of Porites (Scleractinia, Poritidae) from the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Syst. Biodivers.17, 491–508. doi: 10.1080/14772000.2019.1643806

100

Terraneo T. I. Fusi M. Hume B. C. Arrigoni R. Voolstra C. R. Benzoni F. et al . (2019a). Environmental latitudinal gradients and host-specificity shape Symbiodiniaceae distribution in Red Sea Porites corals. J. Biogeogr.46, 2323–2335. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13672

101

Terraneo T. I. Ouhssain M. Castano C. B. Aranda M. Hume B. C. Marchese F. et al . (2023). From the shallow to the mesophotic: a characterization of Symbiodiniaceae diversity in the Red Sea NEOM region. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1077805

102

Turner J. A. Andradi-Brown D. A. Gori A. Bongaerts P. Burdett H. L. Ferrier-Pagès C. et al . (2019). Key questions for research and conservation of mesophotic coral ecosystems and temperate mesophotic ecosystems. Mesophotic coral Ecosyst. (Springer, Cham), 12, 989–1003. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92735-0_52

103

Turner J. A. Babcock R. C. Hovey R. Kendrick G. A. (2017). Deep thinking: a systematic review of mesophotic coral ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci.74, 2309–2320. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx085

104

Wickham H. Chang W. Wickham M. H. (2016). Package ‘ggplot2’. Create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics, Vol. 2 (New York: Springer-Verlag), 1–189.

105

Wijsman-Best M. (1974). Habitat-induced modification of reef corals (Faviidae) and its consequences for taxonomy. Proc. 2nd Int. coral Reef Symp2, 217–228.

106

Willis B. L. (1985). “Phenotypic plasticity versus phenotypic stability in the reef corals Turbinaria mesenterina and Pavona cactus,” in Proceedings of the Fifth International Coral Reef Symposium, Vol. 4. 107–112.

107

Winters G. Beer S. Zvi B. B. Brickner I. Loya Y. (2009). Spatial and temporal photoacclimation of Stylophora pistillata: zooxanthella size, pigmentation, location and clade. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.384, 107–119. doi: 10.3354/meps08036

108

Ziegler M. Arif C. Burt J. A. Dobretsov S. Roder C. LaJeunesse T. C. et al . (2017). Biogeography and molecular diversity of coral symbionts in the genus Symbiodinium around the Arabian Peninsula. J. Biogeogr.44, 674–686. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12913

109

Ziegler M. Roder C. M. Büchel C. Voolstra C. R. (2015). Mesophotic coral depth acclimatization is a function of host-specific symbiont physiology. Front. Mar. Sci.2. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2015.00004

Summary

Keywords

MCEs, zooxanthellae, next generation sequencing, ITS2, SymPortal

Citation

Vimercati S, Terraneo TI, Castano CB, Barreca F, Hume BCC, Marchese F, Ouhssain M, Steckbauer A, Chimienti G, Eweida AA, Voolstra CR, Rodrigue M, Pieribone V, Purkis SJ, Qurban M, Jones BH, Duarte CM and Benzoni F (2024) Consistent Symbiodiniaceae community assemblage in a mesophotic-specialist coral along the Saudi Arabian Red Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1264175. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1264175

Received

20 July 2023

Accepted

11 March 2024

Published

26 March 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Charles Alan Jacoby, University of South Florida St. Petersburg, United States

Reviewed by

Dustin Kemp, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Karl David Castillo, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Vimercati, Terraneo, Castano, Barreca, Hume, Marchese, Ouhssain, Steckbauer, Chimienti, Eweida, Voolstra, Rodrigue, Pieribone, Purkis, Qurban, Jones, Duarte and Benzoni.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Silvia Vimercati, silvia.vimercati@kaust.edu.sa

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.