Introduction

The Seaflower Biosphere Reserve (SFBR) is renowned for its remarkably diverse marine life, particularly its rich fish fauna. Several species inhabiting the reserve are under some threat category and there is no exclusive fish species inventory for Courtown Cays (Isla Cayo Bolívar), an atoll located in the southern part of this marine protected area where intense artisanal fishing activities are carried out and illegal fishing has increased since 2006. To address this situation and enhance our scientific understanding of the region’s marine life, a dataset is presented with information about the marine fish species found in this oceanic reef complex during the Seaflower Scientific Expedition 2022. A total of 223 species were registered, distributed in 31 orders and 57 families, with Serranidae (25 spp.) and Labridae (24 spp.) showing the highest species richness. Forty-three species are recorded for the first time in this locality and one of them is recorded for the first time in the SFBR. These results highlights the critical importance of safeguarding vulnerable ecosystems, particularly oceanic coral reefs, which harbor hundreds of species of ecological and economic value and provide numerous ecological and economic benefits. This emphasizes the need of protection and prompt sustainable use of these resources.

Methods

Study area and data collection

The Seaflower Biosphere Reserve (SFBR), created in 2000, is a protected marine area of great importance for the conservation of the natural and cultural heritage of the Archipelago of San Andres, Providencia, and Santa Catalina, covering approximately 180,000 km2. This reserve is home to around a quarter of the Caribbean ichthyofauna (Bolaños-Cubillos et al., 2015; Acero et al., 2019), constituting one of the main reasons for the protection and proper management of its natural richness. Courtown Cays (Isla Cayo Bolívar) are located in the southern part of the reserve, at 12° 22’ – 28’ N and 81° 25’ – 31’ W, has a total area of 50.3 km2 (Díaz et al., 2000) and is part of the complex of 10 islands, keys, banks, and shoals that give the archipelago its name.

Scientific research in this area began at the end of the 20th century (Mejía et al., 1998; Mejía and Garzón-Ferreira, 2000); Bolaños-Cubillos et al. (2015) synthesized the existing knowledge about the ichthyofauna up to that date, providing a list of species for the so-called “southern keys”, Albuquerque and Courtown Cays, based on a compilation of information obtained in previous expeditions, explorations and studies that used different methodologies. The National Plan for Scientific Expeditions carried out by the government of Colombia marked the starting point in the monitoring of these remote areas and the expedition carried out during 2022 allowed the generation of an exclusive list for Cayo Bolivar due to the lack of this information.

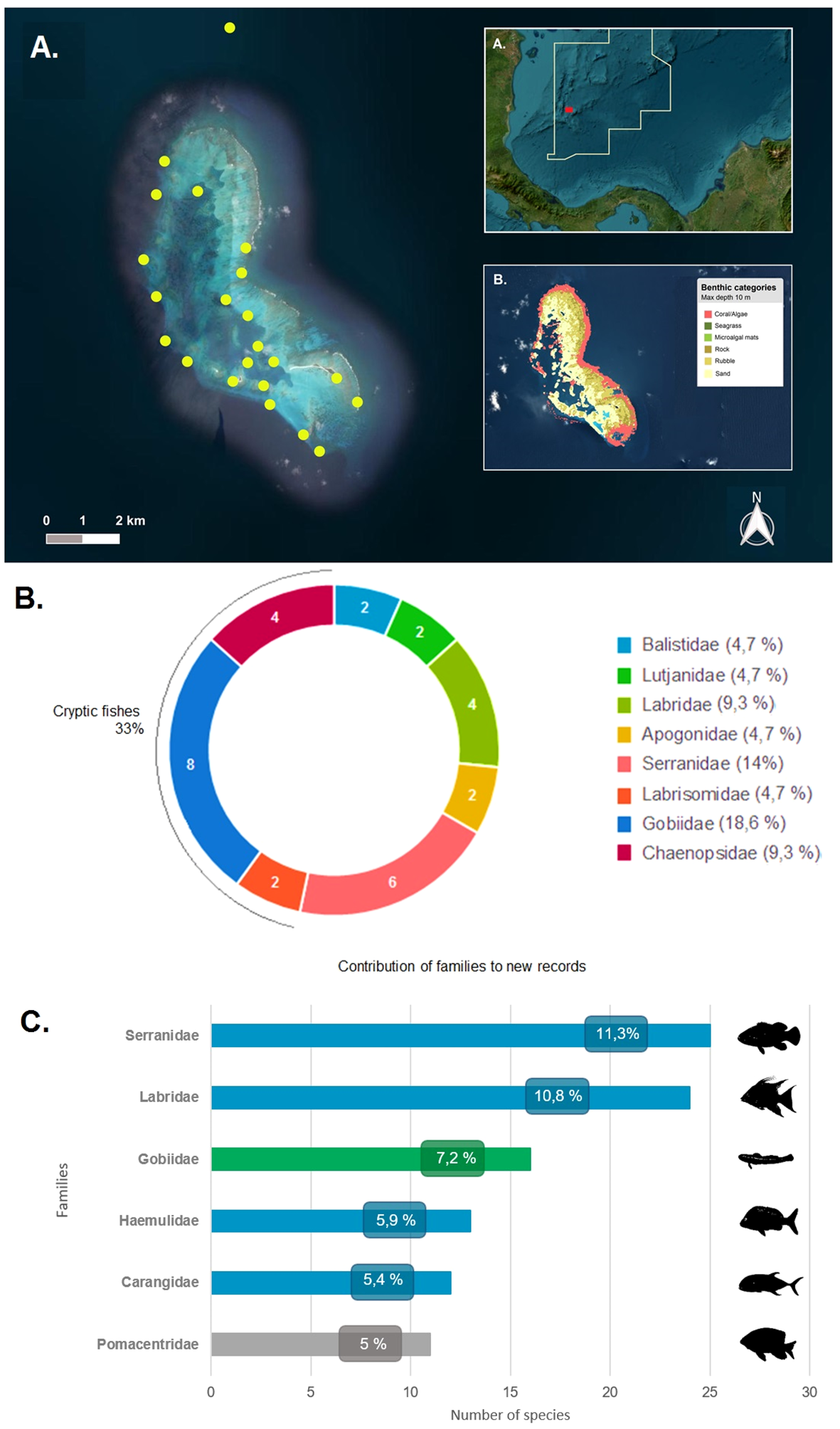

During the Seaflower Scientific Expedition between the 9th and the 21st September, 2022, data was collected through visual censuses in coral reef formations and seagrass beds. The diversity of environments and formations (shallow peripheral reef, lagoon terrace, consolidated reefs, seagrass meadows and continental slope) made of this island an interesting site to study. Explorations were made by four divers through SCUBA diving using a 30 min timed swim method at different depths (0-35 m) in different sites of the key (Figure 1A). Occurrences and counts were conducted for all the species observed along the reef complex. Some specimens were collected to verify their identity and later deposited in the ichthyology collection of the Universidad del Valle (CIRUV). To verify new records, the works of Bolaños-Cubillos et al. (2015); Acero et al. (2019) and Robertson and Van Tassell (2019) were used as a reference.

Figure 1

(A) Distribution of the sampling locations in Courtown Cays reef complex, Seaflower Biosphere Reserve. (AA). Geographical location of the study area. The solid line demarcates the marine protected area. (AB). Bottom characteristics and distribution of benthic categories in Courtown Cays (Allen Coral Atlas, 2022). (B) Families that contributed the most to new records in the study area. White numbers within the circle indicate the number of species recorded per family and the legend denote the percentages that each family contributes to the new records. (C) Families with the highest species richness in Courtown Cays reef complex. In green cryptic fishes and in blue families with fishes of commercial interest.

Data availability

The dataset “Fish biodiversity of Courtown Cays, Seaflower Biosphere Reserve (Colombian Caribbean): new records and an annotated checklist” was assembled using the Darwin Core standard (DwC) and is available through the Integrated Publishing Tool of the Ocean Biogeographic Imation System (OBIS) and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) Colombian nodes (SIBM-SIB Colombia). Links (Acero et al., 2023):

SiB Colombia: https://biodiversidad.co/data?datasetKey=75301af4-c7b0-4b93-818f-bdf5d7cdabe0

GBIF: https://www.gbif.org/dataset/75301af4-c7b0-4b93-818f-bdf5d7cdabe0

OBIS: https://obis.org/dataset/097332d5-d8af-4e83-9f02-4750c1e439c4

Outcomes and discussion

A total of 223 species were recorded for Courtown Cays (Isla Cayo Bolivar) (Table 1). Exploring this atoll allowed us to observe one of the highest fish richness in the SFBR [Roncador: 140 spp.; Serrana: 155 spp.; Serranilla: 166 spp.; Providencia: 248 spp.; Albuquerque: 207 spp.; Courtown Cays (present study): 223 spp.], although we noticed low abundances of large bony predators, which are in turn of high commercial interest such as snappers, groupers and some parrotfishes. Yet, 48 (22%) of the recorded species are of commercial interest to local communities. Twenty-seven of the species observed (12%) have been assigned with some threat category by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and/or the regional assessment included in the Red Book of Marine Fishes of Colombia (Chasqui et al., 2017), and 43 (20%) species were new records for this location.

Table 1

| Order and family | Specie | TC | CI | NR | NRSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARCHARHINIFORMES | |||||

| Carcharhinidae | Carcharhinus perezii | x | x | ||

| Galeocerdo cuvier | x | x | |||

| Negaprion brevirostris | x | x | |||

| Rhizoprionodon sp. | x | x | x | ||

| Sphyrnidae | Sphyrna mokarran | x | x | x | |

| ORECTOLOBIFORMES | |||||

| Ginglymostomatidae | Ginglymostoma cirratum | x | |||

| MYLIOBATIFORMES | |||||

| Dasyatidae | Hypanus americanus | x | x | ||

| Myliobatidae | Aetobatus narinari | x | x | ||

| ANGUILIFORMES | |||||

| Muraenidae | Enchelycore nigricans | ||||

| Gymnothorax funebris | |||||

| Gymnothorax miliaris | |||||

| Gymnothorax moringa | |||||

| Congridae | Heteroconger longissimus | ||||

| Ophichthidae | Myrichthys breviceps | ||||

| CLUPEIFORMES | |||||

| Clupeidae | Jenkinsia sp | ||||

| AULOPIFORMES | |||||

| Synodontidae | Synodus intermedius | ||||

| Synodus synodus | |||||

| HOLOCENTRIFORMES | |||||

| Holocentridae | Holocentrus adscensionis | ||||

| Holocentrus rufus | |||||

| Myripristis jacobus | |||||

| Neoniphon marianus | |||||

| Sargocentron vexillarium | |||||

| SCOMBRIFORMES | |||||

| Scombridae | Thunnus atlanticus | x | |||

| SYNGNATHIFORMES | |||||

| Aulostomidae | Aulostomus maculatus | ||||

| Dactylopteridae | Dactylopterus volitans | ||||

| Mullidae | Mulloidichthys martinicus | ||||

| Pseudupeneus maculatus | |||||

| Syngnathidae | Cosmocampus elucens | x | |||

| GOBIIFORMES | |||||

| Gobiidae | Coryphopterus dicrus | ||||

| Coryphopterus eidolon | x | ||||

| Coryphopterus glaucofraenum | |||||

| Coryphopterus personatus | x | ||||

| Coryphopterus thrix | x | x | |||

| Coryphopterus tortugae | x | x | |||

| Ctenogobius saepepallens | x | ||||

| Gnatholepis thompsoni | |||||

| Elacatinus evelynae | |||||

| Elacatinus horsti | |||||

| Elacatinus lori | x | ||||

| Elacatinus louisae | x | ||||

| Elacatinus prochilos | x | x | |||

| Priolepis hipoliti | |||||

| Ptereleotris helenae | x | ||||

| Risor ruber | x | ||||

| KURTIFORMES | |||||

| Apogonidae | Apogon conklini | ||||

| Apogon maculatus | |||||

| Apogon robbyi | x | ||||

| Astrapogon puncticulatus | x | ||||

| Phaeoptyx sp. | |||||

| INCERTAE SEDIS – CARANGARIA | |||||

| Sphyraenidae | Sphyraena barracuda | x | |||

| Sphyraena borealis | x | x | |||

| CARANGIFORMES | |||||

| Carangidae | Alectis ciliaris | x | |||

| Caranx bartholomaei | x | ||||

| Caranx crysos | x | ||||

| Caranx latus | x | ||||

| Caranx lugubris | x | ||||

| Caranx ruber | x | ||||

| Decapterus tabl | x | x | x | ||

| Elagatis bipinnulata | x | ||||

| Selar crumenophthalmus | x | ||||

| Seriola rivoliana | x | ||||

| Trachinotus goodei | x | ||||

| Trachinotus falcatus | x | ||||

| Coryphaenidae | Coryphaena hippurus | x | |||

| Echeneidae | Echeneis naucrates | ||||

| Echeneis neucratoides | x | ||||

| PLEURONECTIFORMES | |||||

| Bothidae | Bothus lunatus | ||||

| INCERTAE SEDIS – OVALENTARIA | |||||

| Grammatidae | Gramma loreto | ||||

| Gramma melacara | |||||

| Opistognathidae | Opistognathus aurifrons | ||||

| Opistognathus maxillosus | |||||

| Opistognathus whitehursti | x | ||||

| Pomacentridae | Abudefduf saxatilis | ||||

| Azurina cyanea | |||||

| Azurina multilineata | |||||

| Chromis insolata | |||||

| Microspathodon chrysurus | |||||

| Stegastes adustus | |||||

| Stegastes diencaeus | |||||

| Stegastes leucostictus | |||||

| Stegastes partitus | |||||

| Stegastes planifrons | |||||

| Stegastes xanthurus | |||||

| BELONIFORMES | |||||

| Belonidae | Strongylura timucu | x | |||

| Tylosurus crocodrilus | x | ||||

| Exocoetidae | Exocoetus sp. | ||||

| Hemiramphidae | Hemiramphus balao | ||||

| BLENNIIFORMES | |||||

| Blenniidae | Entomacrodus nigricans | ||||

| Ophioblennius macclurei | |||||

| Chaenopsidae | Acanthemblemaria aspera | x | |||

| Acanthemblemaria maria | x | ||||

| Acanthemblemaria spinosa | |||||

| Chaenopsis sp. | x | ||||

| Emblemaria pandionis | x | ||||

| Emblemariopsis sp. | |||||

| Lucayablennius zingaro | |||||

| Labrisomidae | Gobioclinus bucciferus | ||||

| Gobioclinus kalisherae | x | ||||

| Malacoctenus aurolineatus | x | ||||

| Malacoctenus boehlkei | |||||

| Malacoctenus erdmani | |||||

| Malacoctenus gilli | |||||

| Malacoctenus macropus | |||||

| Malacoctenus triangulatus | |||||

| Tripterygiidae | Enneanectes boehlkei | ||||

| INCERTAE SEDIS – EUPERCARIA | |||||

| Malacanthidae | Malacanthus plumierii | ||||

| Pomacanthidae | Centropyge argi | x | |||

| Holacanthus ciliaris | |||||

| Holacanthus tricolor | |||||

| Pomacanthus arcuatus | |||||

| Pomacanthus paru | |||||

| Sciaenidae | Eques punctatus | ||||

| GERREIFORMES | |||||

| Gerreidae | Eucinostomus sp. | x | |||

| LABRIFORMES | |||||

| Labridae | Bodianus rufus | ||||

| Clepticus parrae | |||||

| Halichoeres bivittatus | |||||

| Halichoeres cyanocephalus | x | ||||

| Halichoeres garnoti | |||||

| Halichoeres maculipinna | |||||

| Halichoeres pictus | x | ||||

| Halichoeres poeyi | x | ||||

| Halichoeres radiatus | |||||

| Lachnolaimus maximus | x | x | |||

| Scarus coelestinus | x | ||||

| Scarus guacamaia | x | ||||

| Scarus iseri | |||||

| Scarus taeniopterus | |||||

| Scarus vetula | x | ||||

| Sparisoma atomarium | |||||

| Sparisoma aurofrenatum | |||||

| Sparisoma chrysopterum | |||||

| Sparisoma radians | |||||

| Sparisoma rubripinne | |||||

| Sparisoma viride | x | ||||

| Thalassoma bifasciatum | |||||

| Xyrichtys martinicensis | x | ||||

| Xyrichtys splendens | |||||

| CHAETODONTIFORMES | |||||

| Chaetodontidae | Chaetodon capistratus | ||||

| Chaetodon ocellatus | |||||

| Chaetodon sedentarius | |||||

| Chaetodon striatus | |||||

| Prognathodes aculeatus | |||||

| ACANTHURIFORMES | |||||

| Acanthuridae | Acanthurus chirurgus | ||||

| Acanthurus coeruleus | |||||

| Acanthurus tractus | |||||

| LUTJANIFORMES | |||||

| Haemulidae | Anisotremus surinamensis | ||||

| Anisotremus virginicus | |||||

| Brachygenys chrysargyreum | |||||

| Haemulon album | x | ||||

| Haemulon aurolineatum | |||||

| Haemulon carbonarium | |||||

| Haemulon flavolineatum | |||||

| Haemulon macrostomum | x | ||||

| Haemulon melanurum | x | ||||

| Haemulon parra | x | ||||

| Haemulon plumierii | x | ||||

| Haemulon sciurus | x | ||||

| Haemulon vittatum | |||||

| Lutjanidae | Apsilus dentatus | x | |||

| Lutjanus analis | x | x | |||

| Lutjanus apodus | x | ||||

| Lutjanus buccanella | x | x | |||

| Lutjanus griseus | x | ||||

| Lutjanus jocu | x | x | |||

| Lutjanus mahogoni | x | ||||

| Lutjanus synagris | x | x | |||

| Lutjanus chrysurus | x | x | |||

| LOBOTIFORMES | |||||

| Lobotidae | Lobotes surinamensis | ||||

| SPARIFORMES | |||||

| Sparidae | Calamus bajonado | ||||

| Calamus calamus | |||||

| PRIACANTHIFORMES | |||||

| Priacanthidae | Heteropriacanthus cruentatus | ||||

| LOPHIIFORMES | |||||

| Antennariidae | Antennarius pauciradiatus | x | |||

| TETRAODONTIFORMES | |||||

| Balistidae | Balistes capriscus | ||||

| Balistes vetula | x | x | x | ||

| Canthidermis maculata | |||||

| Canthidermis sufflamen | x | ||||

| Melichthys niger | |||||

| Diodontidae | Diodon holocanthus | ||||

| Diodon hystrix | |||||

| Xanthichtys ringens | x | ||||

| Monacanthidae | Aluterus scriptus | ||||

| Cantherines macrocerus | |||||

| Cantherines pullus | |||||

| Monacanthus tuckeri | |||||

| Ostraciidae | Acanthostracion polygonius | ||||

| Acanthostracion quadricornis | |||||

| Lactophrys bicaudalis | |||||

| Lactophrys trigonus | |||||

| Lactophrys triqueter | |||||

| Tetraodontidae | Canthigaster rostrata | ||||

| Sphoeroides spengleri | |||||

| PEMPHERIFORMES | |||||

| Pempheridae | Pempheris schomburgkii | ||||

| CENTRARCHIFORMES | |||||

| Cirrhitidae | Amblycirrhitus pinos | ||||

| Kyphosidae | Kyphosus cinerascens | x | |||

| Kyphosus vaigiensis | |||||

| PERCIFORMES | |||||

| Serranidae | Cephalopholis cruentata | x | |||

| Cephalopholis fulva | x | ||||

| Diplectrum bivittatum | |||||

| Epinephelus guttatus | x | ||||

| Hypoplectrus aberrans | |||||

| Hypoplectrus affinis | x | ||||

| Hypoplectrus guttavarius | |||||

| Hypoplectrus indigo | |||||

| Hypoplectrus maculiferus | x | ||||

| Hypoplectrus nigricans | |||||

| Hypoplectrus providencianus | x | ||||

| Hypoplectrus puella | |||||

| Hypoplectrus randallorum | x | ||||

| Hypoplectrus unicolor | |||||

| Liopropoma rubre | |||||

| Mycteroperca bonaci | x | x | |||

| Mycteroperca interstitialis | x | x | |||

| Mycteroperca tigris | x | x | |||

| Mycteroperca venenosa | x | x | |||

| Serranus baldwini | x | ||||

| Serranus tabacarius | |||||

| Serranus tigrinus | |||||

| Serranus tortugarum | x | ||||

| Rypticus saponaceus | |||||

| Schultzea beta | x | ||||

| Scorpaenidae | Pterois volitans | ||||

| Scorpaena cf. albifimbria | |||||

| Scorpaena plumieri | |||||

Inventory of the species observed in Cayo Bolivar during the Seaflower Scientific Expedition 2022.

Species under some threat category: TC; species of commercial interest: CI; new record for the locality: NR; new record for the SFBR: NRSF.

The most abundant families were Serranidae (11%), Labridae (11%), Gobiidae (7%), Haemulidae (6%), Carangidae (5%), and Pomacentridae (5%), with other families representing less than 5% of the total fish richness (Figure 1B). Families Serranidae, Labridae, Haemulidae and Carangidae have species of commercial interest, which therefore highlights the crucial role and potential of these areas in the conservation of fish stocks.

Pomacentridae is one of the most abundant families that can be found in the Caribbean Sea assemblages and are characterized by its numerical dominance of small bodied species and broader distribution (Seeman et al., 2018). Other studies carried out in the Caribbean have found similar results, with this being one of the most recorded fish families (Dominici-Arosemena and Wolff, 2005; Alemu, 2014; Andradi-Brown et al., 2016).

Gobiidae was the third richest family in the study and contributed with 16 species. Other families of cryptic fishes, such as Chaenopsidae and Labrisomidae, were also significant as they represent 33% of the new records of this study (Figure 1C). A large proportion of tropical reef fish diversity is composed of cryptobenthic fishes: bottom-dwelling, morphologically or behaviorally cryptic species typically less than 50 mm in length (Depczynski and Bellwood, 2003). Their small body size allowed them to diversify at high rates exploiting small microhabitats and develop a wide range of life-history adaptations. However, despite their diversity and abundance, these fishes are poorly studied, overlooked and an underestimated component due to their small size, difficult identification, and cryptic habits (Herler et al., 2011). Since the information about the geographic coverage of cryptobenthic fishes is poor, this emphasizes the remarkable reservoir of biodiversity that is yet to be discovered (Brandl et al., 2018). On the other hand, the crucial ecological role of this community of fishes in coral reef trophodynamics is of great value (Bellwood et al., 2012; Goatley et al., 2016; Brandl et al., 2019) and makes necessary to apply greater efforts to study this “hidden half” of the vertebrate biodiversity on coral reefs (Brandl et al., 2018).

The high number of new records calls upon the need to continue the exploration and monitoring on remote localities and join research efforts to expand knowledge about the ecology, systematics, and conservation of understudied groups. Most of the new records may be due to reduced methodologies, limitations in sampling and few studies previously carried out in this location. The two new records of sharks were provided by Diego Cardeñosa, who carried out a study using baited remote underwater videos BRUVS. The use of this methodology different from the classic visual censuses has been found to be especially effective at observing predatory and mobile species, such as elasmobranchs, since the behaviour of many fish changes in the presence of divers (Watson and Harvey, 2007).

In the case of the cherubfish Centropyge argi, the yellowcheek wrasse Halichoeres cyanocephalus, the sargassum triggerfish, Xanthichthys ringens, the school bass Schultzea beta and the chalk bass Serranus tortugarum it has been found that they are only present at depths greater than 30 m or are more abundant in deep environments (Randall, 1963; Colin, 1974; Moyer et al., 1983; Weaver et al. 2006; Robertson and Van Tassell, 2019) so they appear to be indicator species of mesophotic habitats (García-Sais, 2010) and are difficult species to census since depth becomes a limitation when carrying out studies through autonomous diving. Other species such as the rosy razorfish Xyrichtys martinicensis may have gone unnoticed previously since they do not actually live in coral reefs, but rather in sandy bottoms or near seagrass meadows.

These results place these small key as a strategic point in the conservation of the ichthyic fauna of the SFBR, as well as of the Greater Caribbean. However, despite the species richness found, the observed abundances indicated the presence of only a few representatives of fish families of high-body sizes and of commercial interest mainly because they are targeted by artisanal fishermen and illegal fishing. Therefore, it is imperative to direct efforts for the protection, monitoring, control and surveillance of these localities that are little studied but intensively exploited.

Statements

Data availability statement

The dataset “Fish biodiversity of Courtown Cays, Seaflower Biosphere Reserve (Colombian Caribbean): new records and an annotated checklist” was assembled using the Darwin Core standard (DwC) and is available through the Integrated Publishing Tool of the Ocean Biogeographic Imation System (OBIS) and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) Colombian nodes (SIBM-SIB Colombia). Links (Acero et al., 2023):

SiB Colombia: https://biodiversidad.co/data?datasetKey=75301af4-c7b0-4b93-818f-bdf5d7cdabe0

GBIF: https://www.gbif.org/dataset/75301af4-c7b0-4b93-818f-bdf5d7cdabe0

OBIS: https://obis.org/dataset/097332d5-d8af-4e83-9f02-4750c1e439c4

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AP-S: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. NO: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. NR: Validation, Writing – review & editing. JT: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This workwas supported by Universidad Nacional de Colombia – Sede Caribe, Universidad del Valle and the Colombian Ocean Commission –CCO [for its Spanish initials]. The publication of this manuscript was financially supported by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation through the Colombia Bio Program, the Corporation Center of Excellence in Marine Sciences – CEMarin and the Colombian Ocean Commission through the special cooperation agreement No. 80740-026-2022.

Acknowledgments

The Colombian Ocean Commission who lead the National Plan for Scientific Expeditions, the Instituto de Estudios en Ciencias del Mar (CECIMAR), Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Sede Caribe and Universidad del Valle for their contribution to the logistics and development of this project. To Diego Cardeñosa for the records provided from his project and to Edgardo Londoño for its support in taking photographs of the specimens

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1327438/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1Fishes observed and/or collected during the Seaflower Scientific Expedition 2022. (A)Acanthemblemaria spinosa. (B)Acanthemblemaria maria. (C)Emblemaria pandionis female. (D)Elacatinus louisae. (E)Coryphopterus tortugae.(F)Gobioclinus kalisherae.(G)Canthidermis maculata and Lobotes surinamensis.

References

1

Acero P. A. Puentes-Sayo A. Tavera J. J. Pabon-Quintero P. E. Rivas-Escobar N. Ossa-Hernández N. (2023). Biodiversidad íctica de Isla Cayos de Bolívar: potencial del territorio insular Colombiano en la conservación de especies amenazadas. v1.0 (the Ocean Biodiversity Information System: Universidad Nacional de Colombia). Dataset/Occurrence. doi: 10.15472/4a8ygj

2

Acero P. ,. A. Tavera J. J. Polanco A. Bolaños-Cubillos N. (2019). Fish biodiversity in three northern islands of the Seaflower Biosphere Reserve (Colombian Caribbean). Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00113

3

Alemu J. B. (2014). Fish assemblages on fringing reefs in the southern Caribbean: biodiversity, biomass and feeding types. Rev. Biol. Trop.62 (3), 169–181.

4

Allen Coral Atlas . (2022). Imagery, maps and monitoring of the world's tropical coral reefs. Available at: https://allencoralatlas.org/atlas/#12.00/12.4000/-81.4167.

5

Andradi-Brown D. A. Macaya-Solis C. Exton D. A. Gress E. Wright G. Rogers E. et al . (2016). Assessing caribbean shallow and mesophotic reef fish communities using baited-remote underwater video (BRUV) and diver-operated video (DOV) survey techniques. PloS One11 (12), e0168235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168235

6

Bellwood D. R. Baird A. H. Depczynski M. González-Cabello A. Hoey A. S. Lefevre C. D. et al . (2012). Coral recovery may not herald the return of fishes on damaged coral reefs. Oecologia170, 567–573. doi: 10.1007/s00442-012-2306-z

7

Bolaños-Cubillos N. Abril A. Bent-Hooker H. Caldas J. P. Acero P. A. (2015). Lista de peces conocidos del Archipiélago de San Andrés, Providencia y Santa Catalina, Reserva de la Biosfera Seaflower, Caribe Colombiano. Bol. Invest. Mar. Cost.44, 127–162. doi: 10.25268/bimc.invemar.2015.44.1.24

8

Brandl S. J. Goatley C. H. R. Bellwood D. R. Tornabene L. (2018). The hidden half: Ecology and evolution of cryptobenthic fishes on coral reefs. Biol. Rev. Cambridge Philos. Soc93 (4), 1846–1873. doi: 10.1111/brv.12423

9

Brandl S. J. Tornabene L. Goatley C. Casey J. M. Morais R. A. Côté I. M. et al . (2019). Demographic dynamics of the smallest marine vertebrates fuel coral-reef ecosystem functioning. Sci. (New York N.Y.)., eaav3384. doi: 10.1126/science.aav3384

10

Chasqui L. Polanco A. Acero P. A. Mejía-Falla P. Navia A. Zapata L. A. et al . (2017). Libro rojo de peces marinos de Colombia. Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras. Invemar, Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible (Santa Marta, ColombiaInstituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras. Invemar, Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible), 552.

11

Colin P. L. (1974). Observation and collection of deep-reef fishes off the coasts of Jamaica and British Honduras (Belize). Mar. Biol.24 (1), 29–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00402844

12

Depczynski M. Bellwood D. R. (2003). The role of cryptobenthic reef fishes in coral reef trophodynamics. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.256, 183–191. doi: 10.3354/meps256183

13

Díaz J. M. Barrios L. M. Cendales M. H. Garzón-Ferreira J. Geister J. López-Victoria M. et al . (2000). Áreas coralinas de Colombia (Santa Marta: INVEMAR), 176.

14

Dominici-Arosemena A. Wolff M. (2005). Reef fish community structure in bocas del toro (Caribbean, Panama): gradients in habitat complexity and exposure. Caribb. J. Sci.41 (3), 613–637.

15

García-Sais J. R. (2010). Reef habitats and associated sessile-benthic and fish assemblages across a euphotic–mesophotic depth gradient in Isla Desecheo, Puerto Rico. Coral Reefs.29 (2), 277–288. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0582-9

16

Goatley C. González-Cabello A. Bellwood D. R. (2016). Small cryptopredators contribute to high predation rates on coral reefs. Coral Reefs.36 (1), 207–212. doi: 10.1007/s00338-016-1521-1

17

Herler J. Munday P. L. Hernaman V. (2011). “Gobies on coral reefs. Chapter 4.2,” in The biology of gobies. Eds. PatznerR. A.Van TassellJ. L.KovačićM.KapoorB. G. (Jersey, British Isles, New Hampshire: Science Publishers), 685.

18

Mejía L.S. Garzón-Ferreira J Acero P A. (1998). Peces registrados en los complejos arrecifales de los cayos Courtown, Albuquerque y los bancos Serrana y Roncador, Caribe occidental. Colombia. Bol. Ecotrópica32: 25–42

19

Mejía L.S. Garzón-Ferreira J. (2000). Estructura de la comunidad de peces arrecifales en cuatro atolones del archipiélago de San Andrés y Providencia (Caribe suroccidental). Rev. Biol. Trop.48 (4), 883–896.

20

Moyer J. T. Thresher R. E. Colin P. L. (1983). Courtship, spawning and inferred social organization of American angelfishes (Genera Pomacanthus, Holacanthus and Centropyge; Pomacanthidae). Environ. Biol. Fishes.9 (1), 25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00001056

21

Randall J. E. (1963). Three new species and six new records of small serranoid fishes from Curaçao and Puerto Rico. Stud. Fauna Curacao other Caribbean Islands19 (1), 77–110.

22

Robertson D. R. Van Tassell J. (2019). Shorefishes of the Greater Caribbean: online information system (Balboa, Panamá: Version 2.0 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute).

23

Seeman J. Yingst A. Stuart-Smith R. D. Edgar G. J. Altieri A. H. (2018). The importance of sponges and mangroves in supporting fish communities on degraded coral reefs in Caribbean Panama. PeerJ6, e4455. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4455

24

Watson D. L. Harvey E. S. (2007). Behaviour of temperate and sub-tropical reef fishes towards a stationary SCUBA diver. Mar. Freshwat Behav. Physiol.40, 85–103. doi: 10.1080/10236240701393263

25

Weaver D. C. Hickerson E. L. Schmahl G. P. (2006). Deep reef fish surveys by submersible on Alderdice, McGrail, and Sonnier Banks in the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Professional Paper NMFS 5 (Silve Springs, MD, USA: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), 69–87.

Summary

Keywords

fish species, inventory, new records, seaflower biosphere reserve, Courtown Cays

Citation

Puentes-Sayo A, Ossa N, Rivas N, Tavera J and Acero P A (2024) Fish biodiversity of Courtown Cays, seaflower biosphere reserve (Colombian Caribbean): new records and an annotated checklist. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1327438. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1327438

Received

25 October 2023

Accepted

29 January 2024

Published

16 February 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Sabrina Lo Brutto, University of Palermo, Italy

Reviewed by

Randa Mejri, University of Sfax, Tunisia

Branko Dragičević, Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries (IZOR), Croatia

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Puentes-Sayo, Ossa, Rivas, Tavera and Acero P.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alejandra Puentes-Sayo, ppunetes@unal.edu.co

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.