Abstract

Maritime countries, including Indonesia, have indicated their interest in developing a national ocean policy and blue economy plan to boost economic growth while promoting sustainability in and from oceanic activities. In 2017, the Government of Indonesia published the Indonesian Ocean Policy (IOP), the first of its kind since independence, and subsequently developed a series of blue economy documents as an integral part of its national development agenda whilst also indicating its support for the global sustainability objectives stipulated in the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, development obstacles such as: declining ocean health; climate crises; fragmented ocean management; inadequate infrastructure and technology; limited data support; low sustainable investment; and the blurred definition of the blue economy, pose risks to successful outcomes of sustainable ocean development in Indonesia. When unaddressed, these challenges can inhibit the policy’s effectiveness in delivering its intended outcomes. This qualitative study explores Indonesia’s interests in sustainable ocean development and how it pursues them while advancing economic objectives and commitments towards SDGs and net zero emission targets. The study finds that maintaining ocean health and ensuring sustainable use of ocean resources are Indonesia’s most vital interests for sustainable ocean development. The national ocean policy and the blue economy have been employed as two successive and simultaneous avenues to pursue Indonesia’s maritime interests. Unfortunately, to date, both approaches have yet to obtain maturity and ocean affairs are overshadowed by other national development priorities. By focusing on ocean governance and its development in the contemporary context, this article sheds light on the important role of policymaking in modern-day ocean governance. A cautious approach to policy design is crucial to avoid common pitfalls in sustainable ocean development, such as weak implementation strategies and the consequent failure to meet core sustainability objectives.

1 Introduction

Since 1982, as the nations concluded the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Indonesia has gained its formal status as an archipelagic state. Owing to the immense size of its maritime zones, encompassing 6.4 million square kilometers and 17,504 named and unnamed islands, Indonesia is the largest archipelagic state in the world that encapsulates vast ocean areas with abundant living and non-living resources (CMMAI-RI, 2018). Despite the great potential of its ocean resources and the opportunities to grow as a future maritime power, Indonesia struggles to manage its lengthy coastline and diverse oceanic ecosystems across the archipelago (Government of Indonesia, 2015a, 2017b, 2020a; Oegroseno, 2017, 2020; Sari and Muslimah, 2020). To date, the potential of the natural advantages within Indonesia’s vast ocean jurisdiction has not been well utilized. The World Bank (2021) warned:

“… there are challenges to the extent and integrity of Indonesia’s marine and coastal ecosystems that, if not managed well, could undermine the potential of Indonesia’s ocean economy.”

In this context, the ideas of a national ocean policy and the blue economy have become increasingly appealing and challenging for Indonesia. Maritime countries, including Indonesia, have indicated their interest in developing a national ocean policy and blue economy plan to boost economic growth while promoting sustainability in and from oceanic activities (Cicin-Sain et al., 2015; Bolaky, 2020; Ocean Panel, 2022; Wuwung et al., 2022). Unfortunately, so far, it is hard to point out any count4ries or projects that represent a successful and proven record of the blue economy practice in the real world (GOF, 2024). What we know today are the various capacities of different countries and their progress in the development of blue economy policy at the national level (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2021; Adrianto, 2022; Wuwung et al., 2022).

In 2017, the Government of Indonesia published the Indonesian Ocean Policy (IOP), the first of its kind since independence, and most recently it has developed a series of blue economy documents. Indonesia’s blue economy development has become an integral part of the country’s national development agenda, which focuses on unlocking the potential for new sources of economic growth (Pane et al., 2021). However, development obstacles such as: declining ocean health; climate crises; fragmented ocean management; inadequate infrastructure and technology; limited data support; low sustainable investment (Dirhamsyah, 2006; Pane et al., 2021; Wardhani et al., 2023; Yulaswati, 2023); and the blurred definition of the blue economy (Smith-Godfrey, 2016; Keen et al., 2018; Voyer et al., 2018a; Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2022), pose risks to sustainable ocean development in Indonesia. When unaddressed, these challenges can inhibit the policies’ effectiveness in delivering their intended outcomes.

Responding to the conundrum of ocean governance in Indonesia, the aim of this study is to draw insights from Indonesia’s ocean policy and blue economy approaches. The study’s primary source of literature includes policies and planning documents, laws and regulations, reports, and relevant journal articles about sustainable ocean development in Indonesia. The analysis focuses on exploring the development and implementation of ocean policy and the blue economy in Indonesia to showcase sustainable ocean development practices at the national level in the context of developing countries. Moreover, by focusing on ocean governance and its development in the contemporary context, this article sheds light on the important role of policymaking in modern-day ocean governance. A cautious approach in policy design is crucial to avoid common pitfalls in sustainable ocean development, such as weak implementation strategies and the consequent failure to meet core sustainability objectives.

2 Materials and method

This study adopts a qualitative analysis approach to address two research questions: What are Indonesia’s interests in sustainable ocean development? And how does Indonesia pursue those interests?

The exploratory nature of the study requires qualitative research to unveil a complex and detailed understanding of the research questions (Creswell and Poth, 2018). This study involved analyzing publications relevant to identifying Indonesia’s interest in ocean governance, along with ways and means to implement them successfully, through document analysis (Bowen, 2009; Morgan, 2022). Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2022) was used to generate themes that help answering the research questions.

The reference types included were: government documents; laws and regulations; books and book sections; journal articles; and reports on ocean policy and the blue economy in Indonesia from 2010 to (July) 2024. Additionally, relevant grey literature including: government reports; policy statements and issues papers; conference proceedings; theses and dissertations; online multimedia (e.g., online webinar, workshop, conference); official websites; news; and press releases relevant to the development and implementation of ocean policy and blue economy in Indonesia were also analyzed in this study. The grey literature sources mainly come from the government websites and YouTube channels (such as CMMAI-RI, Bappenas-RI, MMAF-RI, BPS, etc.), education and research institutions and media that engaged with ocean policy and blue economy development in Indonesia. As the study focuses on national-level policy analysis on sustainable ocean development in Indonesia, literature dealing with the geostrategic level of international relations or emphasizing technical details on marine engineering and science that are not directly relevant to national-level policymaking and implementation have been excluded from the analysis.

A combination of searches using library (Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest) and non-library (e.g. google scholar/google) databases, was used to collect materials for analysis. The search strategy used sets of English and Indonesian keywords or search terms listed in Table 1.

Table 1

| Indonesia AND “blue economy” OR “ocean economy” OR “marine economy” OR “maritime economy” OR “marine policy” OR “maritime policy” OR “ocean policy” OR “kebijakan kelautan” OR “kebijakan maritim” |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria: 1) Included: • Category: Peered reviews (non-peered reviews articles were included, subject to its relevance and reliability), journal articles, books/chapters, conferences proceeding, and report. • Language: English and Indonesia. • Country/Territory: Indonesia • Date: 2010 to (July) 2024. 2) Excluded: Literatures with technical focus not directly relevant to ocean policy and blue economy development; and literatures with maritime geopolitical and security focus. Endnote was used to help in screening references that are not relevant to focus of analysis. |

The search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

As of the date of writing, 238 references were identified that meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria set in this study, which include grey literatures and online multimedia (e.g. webinar and online workshop/conference) (see Supplementary Table 4).

The study has been structured into two core sections, followed by a discussion. The first section is a brief historical review of ocean development in Indonesia that explores Indonesia’s interests in sustainable ocean development. This is followed by an analysis of the main national strategic documents on ocean governance to shed light on the six strategic issues of Indonesia’s integrated approach to ocean governance (natural capital, human capital, maritime security, ocean economy, integrated management, and natural vulnerability). The second section seeks to comprehend how Indonesia pursues its interests in sustainable ocean development. The discussion section analyses the competing interests in advancing sustainable ocean development in Indonesia and identifies key areas (strategic priorities) for improving the current policies.

3 Indonesia’s interest in sustainable ocean development

Indonesia’s interest in sustainable development is shaped by historical developments of ocean affairs in Indonesia dating back to the Neolithic age. In this era, the movement of people across the Australasian region helped establish maritime trade and communication networks in the Southeast Asia region (Solheim et al., 2006). Since Indonesia gained independence in 1945, the country’s interests in ocean development continue to evolve and be influenced by global, regional, and national dynamics, yet they remain anchored in the national objectives stipulated in the 1945 Constitution of Indonesia. The year 2045 which will mark one hundred years of Indonesia’s independence has triggered the government of Indonesia to boost the national development and to accelerate the achievement of Indonesia’s national goals.

The following section identifies the historical influences shaping Indonesia’s interest in sustainable ocean development and then explores the translation of its constitutional objectives into national development doctrine, vision, and goals.

3.1 The origin of Indonesia’s maritime vision

Indonesia’s maritime vision was founded long before Indonesia was recognized as an independent country. Solheim’s hypothesis of the Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network (NMTCN) was a hallmark of Indonesia’s historical culture and identity as a maritime nation with its maritime-oriented people (Solheim et al., 2006). Solheim claims that Southeast Asia (including Indonesia) is the origin and source of the spread of people and culture to the broader region of Austronesia, including the eastern part of Africa territories, such as Madagascar (Solheim et al., 2006; Bellwood, 2017; Oegroseno, 2017). The linguistic and cultural footprint found in Madagascar and artefacts in Indonesia, for example, a ship relief in Borobudur temple with two sails and outriggers (Dick-Read, 2005; Beale, 2006; Indonesia.Go.Id, 2019a; Serva and Pasquini, 2022), substantiate the Nusantao’s argument. The arrival of European colonial powers in Southeast Asia at the brink of the 16th Century during the age of exploration gradually changed the maritime architecture in the region (Lapian, 2009). Maritime trade was dominated by colonial merchant fleets, representing a new global maritime capitalist order, marginalized domestic and traditional fleets as a form of local adaptation (Lapian, 2009; Sulistiyono et al., 2021). Since then, piracy and sea robbery have grown sporadically across the strategic chokepoints in Southeast Asia maritime trade routes such as Malacca Strait and Sulu Sea, which remain contemporary challenges to maritime security (Young, 2005; Lapian, 2009). Another legacy of colonialism in Indonesia was the shift from maritime to land-oriented development (Kusumaatmadja, 2005; Bappenas-RI, 2023e). These historical developments in ocean affairs shaped Indonesia’s modern-day ocean governance approach and its vision to become the Global Maritime Fulcrum (GMF).

Indonesia’s maritime vision is also driven by its national ideology, constitution and fundamental norms shaping its nationhood. Pancasila, the national ideology of Indonesia, serves as the guiding principle and norms for national development. The core values of Pancasila, such as unity, democracy, inclusivity, and social justice, are some of the principal tenets for ocean policy development in Indonesia (compare Bennett et al., 2019; Quina et al., 2022). The 1945 Constitution of Indonesia (Second Amendment), article 25E provides legitimate guidance for national development based on the concept of an archipelagic state characterized by Nusantara (Ave, 1989; Evers, 2016; Alverdian, 2024; Simarmata et al., 2023), which is also aligned with the structure of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI: Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia) and the national motto of “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” or Unity in Diversity. Additionally, article 33 lays out guidance for national economic and social development by highlighting the importance of natural resource utilization for the greatest benefit of the people and underlining the fundamental values of inclusivity, efficiency, fairness, sustainability, environmental friendliness, independence and the balance between the national growth and integrity of the national economy. These fundamental bases are the prime foundation for national development in Indonesia, including the aspiration to become a maritime-oriented country.

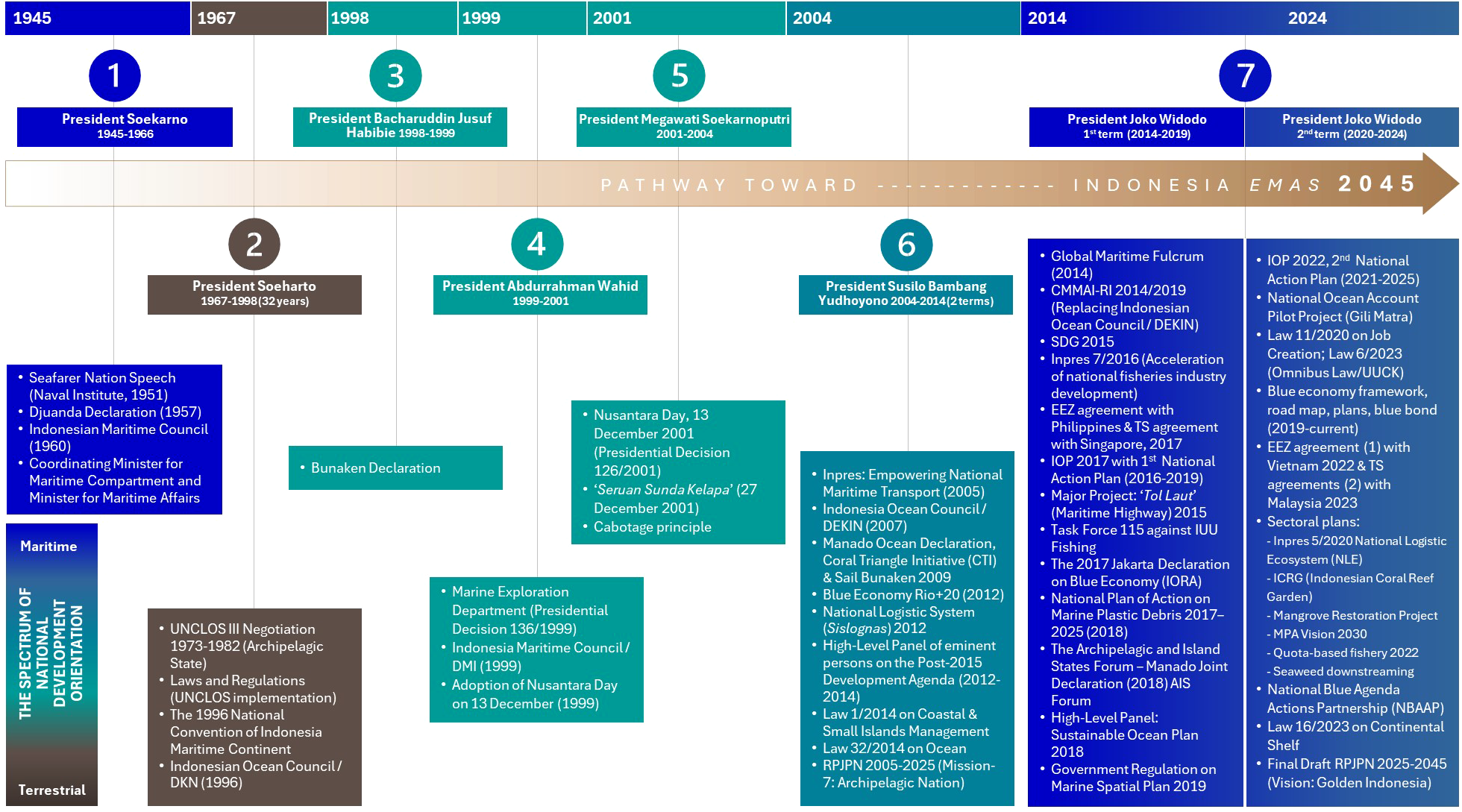

Indonesia’s ocean development hinges on the vision and priorities of its leaders; as John C. Maxwell once uttered: “Everything rises and falls on leadership”. Since independence, there have been leadership acknowledgements of the importance of Indonesia’s maritime destiny, and all leaders since 1945 have expressed their maritime aspiration in a different forms, outlooks, and practices during their respective tenures (Simarmata et al., 2023; Soesilo, 2020). In fact, the number and influence of ocean-based policy initiatives indicate the importance of ocean development in Indonesia across different administrations (see Figure 1). Over three decades, during President Soeharto’s administration, national development was leant intensely toward terrestrial sectors. In the last decade, President Widodo has become the most robust leader and has been passionate about Indonesia’s vision of becoming a strong maritime nation. Under his administration, Indonesia has launched several strategic initiatives to advance programs and activities relevant to sustainable ocean development, with tangible outcomes expected in the longer term.

Figure 1

The maritime orientation and priorities of Indonesian presidents (1945 to 2024).

The GMF vision, introduced early in President Widodo’s 2014 election campaign, has revived and elevated the country’s awareness of the maritime agenda to national development (Kominfo-RI, 2016; Efriza, 2018; Indonesia.Go.Id, 2019b). The GMF unveils both the potential and revival of Indonesia’s historical maritime success by leveraging the country’s geostrategic, geopolitical and geoeconomic advantages. It envisions Indonesia to become a sovereign, advanced, independent, and strong maritime nation, able to contribute to regional and global peace and security aligned with the country’s national interests (Government of Indonesia, 2017b). The GMF vision is propagated and translated into several implementing instruments, for example, Nawacita (The Nine National Visions of Indonesia), the Medium-Term National Development Plan or RPJMN (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional) 2015-2019, and the 2017 Indonesian Ocean Policy (IOP).

In 2023, in accordance with the National Development Planning System (Government of Indonesia, 2004), Bappenas-RI led the formulation of the Long-Term National Development Plan or RPJPN (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Panjang Nasional) 2025-2045 through a series of public consultations (Bappenas-RI, 2023b). By law, this document functions as the legislative anchor to ensure that every President, Governor, Regent and Mayor remains aligned with established long-term planning and no longer possesses individual discretion for different visions and missions (Maharani, 2023). RPJPN 2025-2045 envisages Indonesia’s twenty-year vision for national development, named Indonesia Emas 2045, aiming for a sovereign, advanced, and sustainable NKRI (The Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia). One of the main goals to measure the development progress of this vision is to be a high-income country with a GNI per capita of USD 30,300 and a doubling of maritime GDP contribution from 7.6% (current) to 15% in 2045 (CMMAI-RI and BPS, 2023; Bappenas-RI, 2023b). Realizing the importance of maritime sectors for Indonesia’s long-term development, the Head of Bappenas-RI (Monoarfa, 2023a) posited that:

“Cultural and structural transformations must be undertaken to address the challenges in realizing the grand vision of becoming a maritime nation. First, there needs to be a paradigm shift and commitment to viewing the sea as the front yard. Second, there needs to be an economic transformation to make the sea a source of prosperity that should be managed in a modern, fair, and sustainable manner. Third, institutional and governance transformations are needed to create a more efficient, transparent, and inclusive management of maritime utilization.” (Translated from Indonesian to English by the main author)

3.2 Six strategic issues of Indonesia’s ocean governance

Despite the vast potential of its ocean resources and its advantageous position as the largest archipelagic state, some identifiable, recurring, and complex problems (Government of Indonesia, 2017b) have impeded Indonesia’s ability to become a strong maritime nation (Setiadi and Habil, 2022). Several national development documents that guide sustainable ocean development in Indonesia set out these issues (see Supplementary Table 1) (Government of Indonesia, 2007, 2015a, 2017b, 2020a, 2022c; CMMAI-RI, 2020). Through the document analysis, six major cross-cutting themes were discovered in this study: natural capital, human capital, maritime security, ocean economy, integrated management, and natural vulnerability. These six themes signify the opportunities and impediments in promoting sustainable ocean development in Indonesia. The sections below discuss these strategic issues in more detail.

3.2.1 Natural capital

Indonesia’s natural ocean assets offer advantages but also introduce numerous challenges for sustainable ocean development in the archipelago (Government of Indonesia, 2017b), depending on how well they are managed. The size of Indonesia’s ocean jurisdiction makes it difficult to chart and map the entire areas that will be very useful in ocean policy formulation and decisions (CMMAI-RI, 2024a). Indonesia’s ocean and the coastal regions contain a wealth of natural capital including: fisheries (about 12 million tons annually); rich marine biodiversity (8,500 fish species, 555 seaweed species, 590 coral reef biota); mangrove areas (3.36 million ha); seagrass meadow areas (0.29 million ha); and seaweed areas (1.2 million ha) (Kuswardani et al., 2023). The scale and magnitude of this natural capital has great potential to support human livelihoods and the health of planetary systems by contributing to the global climate change mitigation efforts (for example, net zero emission target, blue carbon initiatives based on mangrove restoration and global biodiversity targets) (IPBC, 2020; King et al., 2021; Sidik et al., 2021; Government of Indonesia, 2022b).

However, development activities that rely on natural resource extraction in developing countries like Indonesia face a dilemma where economic growth puts too much pressure on environmental and social systems (WCED, 1987; Praptiwi et al., 2021; Raharja and Karim, 2022; Rasyid et al., 2022; Sihombing et al., 2022). The current level of Indonesia’s Ocean Health Index (OHI) at the value of 69 (2023), lower than the global average of 73 out of 100 (Ocean Health Index, 2024), indicates the environmental challenge of sustainable ocean development in the country. Marine debris, oil spills and the depletion of fish stocks (over and fully exploited) present substantial challenges for the environment and livelihoods of those who rely on ocean resources (Jambeck et al., 2015; Pane et al., 2021; MMAF-RI, 2022; Wiryawan et al., 2024). The recent achievements of marine debris program performs only at 35.36%, falling short of the target of 70% in 2025 (ADB, 2024; TKN PSL, 2024). The main contributor is plastic debris, especially plastic bags, primarily from land and sea sources, with a higher proportion originating from the former (Purba et al., 2019; Faizal et al., 2022; TKN PSL, 2024). In addition, marine conservation is challenging in Indonesia as indicated by the low percentage of MPAs that are in fully/highly protected level (<1% assessed by the MPA Guide) (Marine Conservation Institute, 2024; Syukri et al., 2024). Therefore, ensuring the long-term sustainability of Indonesia’s natural capital in the ocean requires careful re-evaluation of management strategies.

3.2.2 Human capital

As of 2020, Indonesia’s population was recorded at 270.2 million, with 186.77 million or 69.28% of the population within the productive age (15 to 64 years) (BPS, 2021, 2023b). This figure represents a demographic advantage for Indonesia. A recent report predicted that the demographic bonus will end at the earliest by 2039, and the productive age group will decline to 63.63-64.88% by 2050 (BPS, 2023b; Bappenas-RI, 2023d). The sheer size of this population introduces opportunities for the provision of a future maritime workforce and offers ongoing domestic market opportunities for marine products.

However, the large and growing population does not guarantee smooth and easy pathways toward a competitive ocean economy. BPS statistics in 2023 showed that only 12.32% of the Indonesian workforce holds higher education qualifications (diplomas and above), which hinders the country’s competitiveness and productivity (BPS, 2023a). Lack of skilled and educated workforce, limited accessibility to maritime education and training, and limited ocean literacy are constraints on employment opportunities within the maritime sectors in Indonesia. Fisheries communities in coastal areas often have low Human Development Index (HDI) scores, underscoring Indonesia’s challenge in maximizing human capital due to the traditional habits of day-to-day surviving mode, relying on natural resources from the sea, and unwise spending on daily necessities (Sukoyono and Suhana, 2015). To tackle this problem, the Coordinating Ministry for Maritime and Investment Affairs (CMMAI-RI) initiated ocean literacy programs to promote the maritime culture pillar of the IOP to help prepare the future maritime workforce. The initiative aims to raise maritime awareness among school-aged children, teachers and young people and promote the incorporation of maritime knowledge into the curriculum for all educational stages from early childhood to high school (CMMAI-RI, 2016).

3.2.3 Maritime security

The size of Indonesian maritime jurisdiction and its archipelagic setting introduce a range of maritime security challenges. The maritime geography adds to the complexity of the country’s capability to perform ocean monitoring, controlling and surveillance effectively, particularly against unlawful and destructive activities at sea that undermine economic, ecology, and social values from the oceans. Violations of the law on the use of natural resources damage the environment by jeopardizing the sustainability of marine resources and increasing the risk of biodiversity loss, for example through marine pollution (Wiryawan et al., 2024) and the threat of illegal fishing to sustainable tuna production in Indonesia (Khan et al., 2024).

From the blue economy lens, unresolved maritime boundaries have immediate impact on marine resources concession for commercial exploration and pose uncertainty for investment (Voyer et al., 2018b). Indonesia, to date, has yet to reach agreements with ten neighboring countries on several segments of its maritime borders (Susmoro et al., 2019; Raharja and Karim, 2022). Over the past decade, five maritime borders have been agreed upon between Indonesia and its neighbors: Singapore (1), the Philippines (1), Vietnam (1), and Malaysia (2) (Arsana, 2023; Tran, 2023; MOFA-RI, 2024). While the agreements with Singapore and the Philippines have been ratified, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam must ratify their agreements for them to be effective. In law enforcement at sea, Indonesia has adopted approaches to consolidate the maritime law enforcement arrangements within national institutions to tackle the maritime security threats. Government Regulation Number 13 of 2022 on the Implementation of Security, Safety, and Law Enforcement in Indonesian Waters and Jurisdiction is a tangible effort to solve the problem of overlapping legislation, jurisdiction and authority among Indonesian maritime law enforcement agencies (Government of Indonesia, 2022a; Sitorus and Said, 2023). The attempt to integrate multiple law enforcement institutions continues with the idea of merging Bakamla-RI and KPLP (Kesatuan Penjaga Laut dan Pantai or Sea and Coast Guard Unit) into a single body, known as the Indonesian Coast Guard (ICG) (CMMAI-RI, 2023d).

3.2.4 Ocean economy

Recent global instability has been a wake-up call for the world community to reinforce national resilience. The World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recommended that a blue economy strategy as one viable option for Indonesia’s post-pandemic recovery (OECD, 2020; World Bank, 2021; Anna, 2023; Halada and Burhanuddin, 2023). The estimated value of the ocean economy in Indonesia is calculated using different methodologies, covers different sectors, and calculated by different institutions (Ebarvia, 2016; Sapanli et al., 2020; OECD, 2021). CMMAI-RI and LIPI (Indonesian Institute of Science) estimated Indonesia’s maritime GDP contribution was 11.40% in 2010, then it reduced to 10.41% in 2018 (CMMAI-RI, 2020). However, according to the recent update from CMMAI-RI and BPS, the ocean economy value in 2021 was 7.6% of the national GDP (CMMAI-RI and BPS, 2023). This inconsistency reflects the intricacies of estimating national ocean economic values (Kildow and McIlgorm, 2010; Colgan, 2018), particularly difficult in Indonesia, due to its vast and diverse island geographies. There have been no significant changes in Indonesia’s ocean economy structure and sectoral dynamics in the last decade. The fisheries and oil and gas sectors are the leading contributors to Indonesia’s maritime GDP, while other maritime sectors have reported low value and productivity (Alamsjah, 2017; Nasution, 2022; CMMAI-RI and BPS, 2023; Hidayat, 2023; Pandjaitan, 2023). For this reason, CMMAI-RI, in collaboration with stakeholders, seeks to promote the downstream value-added strategies for ocean sectors (e.g., seaweed industry), inspired by the success of the land-based downstream value-added project (CMMAI-RI, 2023b, 2024b, 2024c; Hidayat, 2023; Pandjaitan, 2023; Sea6 Energy, 2024).

3.2.5 Integrated management

The principle of integration has always been a critical priority for Indonesia in governing and managing its vast ocean areas since centuries ago. Indonesia takes a viewpoint of “Wawasan Nusantara” or “Nusantara Outlook”, seeing the ocean as a unifying factor for the nation rather than a divisive one (Saha, 2016; Government of Indonesia, 2017b; Adi, 2018). However, integration is not easy in practice; breaking the sectoral silos in ocean governance remains a “wicked” problem not only at the global or regional level but also at the national level (Winther et al., 2020); Indonesia is no exception. Apart from existing cross-sectoral fragmentation, vertical integration between central, provincial, and local governments is also challenging in Indonesia (Sunyowati and Butar, 2018; Rusman, 2020). This is due to the inadequate institutional coherence between central and local governments, the provincial and regency development plans are often misaligned with the national policy or plan such as IOP (Heryandi, 2019). Also, under the current system, there is no provincial-level institutions coordinate and synchronize ocean management within their jurisdictions (OECD, 2021). This gap reveals the need for sub-national ocean policies or blue economy plans that serve as regional or local interpretation of national ocean policy into the respective localized context.

Moreover, regional disparities induced by the past Java-centric development has caused multifaceted inequalities between the Western and Eastern parts of Indonesia, including the economic capacity, education and human resources, access to goods, health, and information (Sugiarto, 2016). It is also linked to the limited connectivity between islands, which the government has tried to address by implementing the “Maritime Highway” (Tol Laut) project (Handoko et al., 2020).

3.2.6 Natural vulnerability

The geographical layout of Indonesia’s maritime continent poses natural risks such as earthquakes, landslides, tsunamis, volcano eruptions, floods, extreme weather, coastal erosion and inundation, and the impact of sea level rise (SLR) on populated coastal communities, particularly in northern Java cities (Kryspin-Watson et al., 2019; Nurhidayah and McIlgorm, 2019). The impacts of climate change on marine and coastal sectors in Indonesia include a change in the coastal morphology due to floods which cause erosion, reduce natural coastal buffers and pollution that, damage marine ecosystem (e.g., coral reef bleaching), decrease small boats fishing range and reduce marine safety due to extreme wave height (Bappenas-RI, 2018; Bappenas-RI and LCDI, 2021). Some climate-driven incidents are evident in Indonesia, such as heavy rainfall, river flooding and local tornadoes in West Java and South Kalimantan Provinces that displace residents and damage properties, with flooding alone resulting in more than USD 62 million economic losses (World Meteorological Organization, 2023). Indonesia needs to improve its national efforts in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in ocean and coastal areas (Poernomo and Kuswardani, 2019).

At present, Indonesia’s climate change strategy involves adopting a national action plan for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, a national action plan for climate change adaptation, and Climate Resilience Development (CRD) policy or Kebijakan Pembangunan Berketahanan Iklim (PBI) (Bappenas-RI, 2014, 2020, 2023c; Government of Indonesia, 2011b; Bappenas-RI and LCDI, 2021; Nasution et al., 2022). Although the IOP does not explicitly cover climate change mitigation and adaptation or natural disaster mitigation issues, Indonesia can explore opportunities from ocean-based initiatives to address this growing concern. The need to recognize the climate and ocean nexus will grow in line with the government’s commitment to meeting climate change targets, the SDGs agenda and other ocean conservation requirements.

Overall, the six strategic cross-cutting issues above inform ocean policy areas that need more specific attention today and in the future. Classifying complex problems related to sustainable ocean development in Indonesia into easily identifiable themes assists with the development of effective policies to address them. Thus, Indonesia must design ocean policies with sound implementation strategies that adequately address the six strategic issues elaborated above. The national ocean policy and blue economy must respond directly to the complexity of nature, people, security, integration and the inherent fragility of the archipelago.

4 Sustainable ocean development in Indonesia

In the last decade, Indonesia has made two core policy interventions in the ocean affairs: first, adopting a national ocean policy; and second, developing a series of blue economy policy frameworks. This section explores how Indonesia has developed and implemented a national ocean policy and the blue economy policy frameworks as two approaches in pursuing the country’s interests in sustainable ocean development, following three assessment criteria for blue economy development at the national level: policy development, implementation strategies and sustainability inclusion (Wuwung et al., 2022).

4.1 Indonesian Ocean Policy

The aspiration for Indonesia to have an integrated ocean policy emerged in the early 1990s when UNCLOS entered into force (Agoes, 1991, 1997; Rudiyanto, 2002; CMMAI-RI, 2020). However, it was not until 2014, when Joko Widodo was elected as Indonesia’s Seventh President, that the idea of formulating an ocean policy was realized. President Widodo’s administration started by establishing the Coordinating Ministry of Maritime Affairs (CMMA-RI) in late 2014, which took leadership for ocean policy formulation (Government of Indonesia, 2014b; Yuniarto, 2020). In 2017, the IOP was finalized and became evidence of the government’s strengthened commitment to realize its maritime vision (Government of Indonesia, 2017b).

4.1.1 Policy development

The agenda-setting for the IOP followed a top-down approach with a visionary focus on restoring Indonesia’s maritime power. CMMA-RI took the lead and acted as the initiator for IOP development. IOP development followed a typical policy and regulatory formulation process in Indonesia (Government of Indonesia, 2011a). A special committee comprising inter-ministerial and/or non-ministerial members was formed to draft the policy document. In 2015, CMMA-RI conducted a series of activities to coordinate and synchronize ocean activities within its responsibility, including the process of preparing the IOP draft for adoption in the form of a Presidential Decree (CMMAI-RI, 2016). Outside the committee, CMMA-RI also sought public input on the policy’s formulation through a series of policy discussions involving experts from the government, NGO, academia, practitioners, fisheries communities, and other professionals. In 2017, the IOP with its action plan (2016-2019) was issued as an executive order with a Presidential Decree.

In 2022, the Government of Indonesia promulgated the Second Action Plan of IOP 2021-2025 by Presidential Decree Number 34 of 2022, indicating the government’s consistent commitment to maintain continuity to the next policy phase (Raharja and Karim, 2022; Warta Ekonomi, 2022). The policy update process commenced in 2019 following a similar procedure to the development of the first edition (CMMAI-RI, 2022a). Similar to its predecessor, the Second Action Plan aims to uphold the integrity and continuity of the policy by laying out the program and activities of forty ministries and national institutions and all provincial/local governments to plan, implement, monitor and evaluate their activities in pursuing the policy objectives (Cabinet Secretary, 2022). The focus of the second edition of the IOP action plan had shifted from laying the GMF foundation to developing the maritime industry ecosystem as the continuation of the earlier phase (Warta Ekonomi, 2022). To date, the IOP has been consistently developed and updated, and it has provided strong guidance and outlined concrete plans of action to drive the country’s ocean and coastal development.

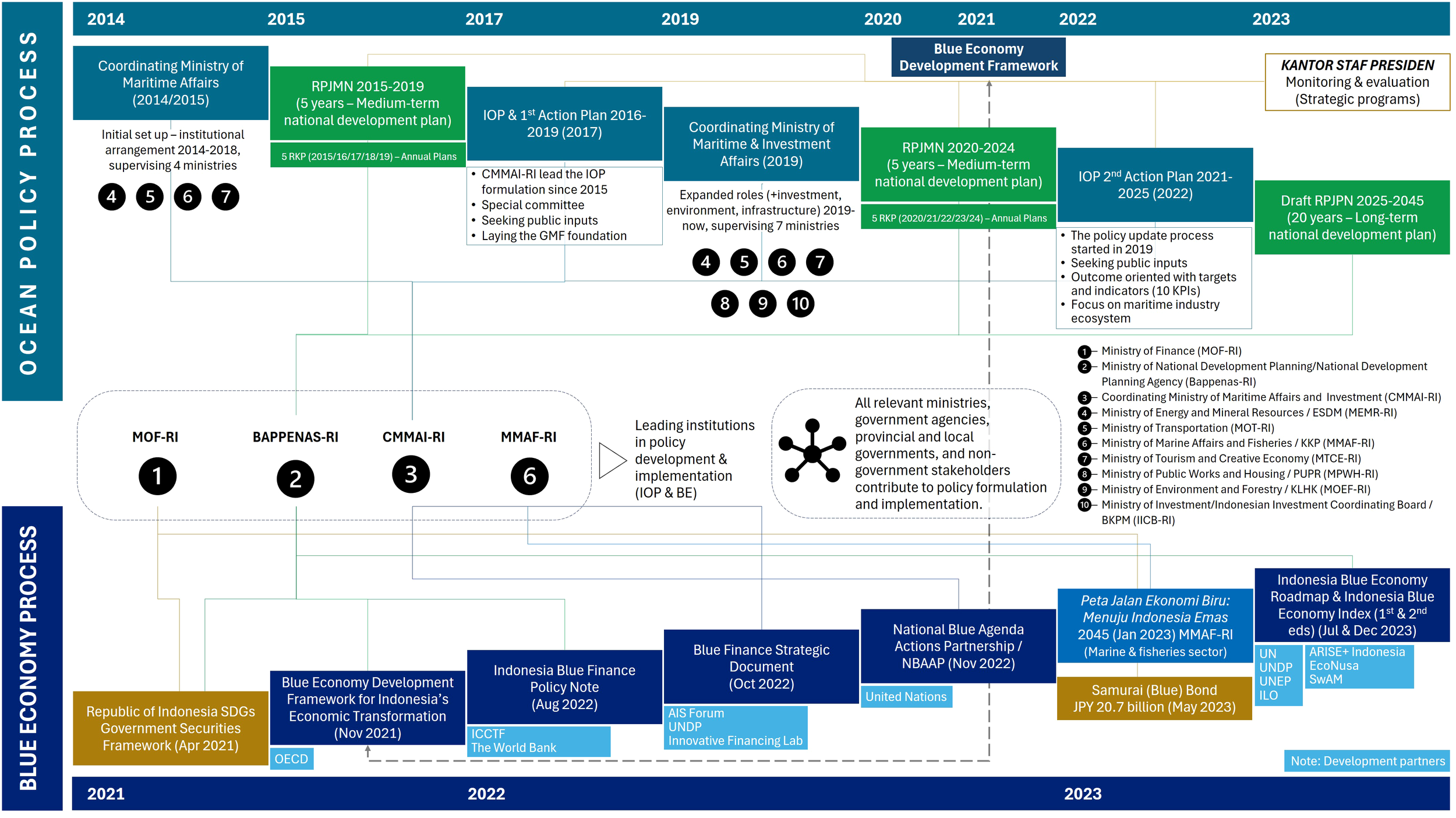

4.1.2 Implementation strategies

The operationalization of the IOP was primarily realized through the two concrete steps the Indonesian government has taken since 2014 (Government of Indonesia, 2022c) (see Figure 2). First was establishing CMMA-RI within President Widodo’s First Cabinet in late 2014, which coordinated, synchronized, and controlled ministerial affairs in maritime portfolios (Government of Indonesia, 2014b, 2015b). From 2015 to 2019, CMMAI-RI’s supervisory and coordinating roles expanded from four to seven ministries, including the addition of the Ministry of Investment in 2019 (Government of Indonesia, 2019). In 2023, CMMAI-RI issued a Minister regulation, the Guidelines for the Implementation of Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting, and Adjustment of the Action Plan for IOP, to improve the effectiveness of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms (CMMAI-RI, 2023a). The Minister’s regulation also seeks to ensure that the plan is being executed as intended, identifying any obstacles to gain an overall understanding of the progress of all programs and activities related to the IOP Action Plan. CMMAI-RI collates the reports from implementing agencies and passes them to the Executive Office of the President or KSP (Kantor Staf Presiden), which is tasked to monitor, evaluate, and provide a progress report on the policy implementation, particularly all programs and activities prioritized in the national development plan.

Figure 2

Indonesian Ocean Policy and blue economy processes (2014-2023).

The second essential step to implementing IOP was the adoption of an action plan that outlines what programs and activities are required and who is responsible for their implementation. This involves multiple actors across different jurisdictions, from national to sub-national levels of government. In this context, successful integration and achieving cumulative impacts and outcomes from different institutions’ programs and activities entail sound cross-cutting coordination and harmonization mechanisms. As of 2022, the Government of Indonesia updated the IOP action plan, which marked a shift from output to an outcome-oriented plan with Ten Key Performance Indicators in the new action plan. The financial scheme to operationalize the IOP followed the existing planning and budgeting mechanism for government institutions to execute programs and activities (Government of Indonesia, 2017a, 2017b; CMMAI-RI, 2020). However, there is no clear, legally binding obligation for the budget allocation to ensure the delivery of all programs and activities listed in the IOP action plan. Furthermore, Bappenas-RI incorporates ocean development agenda into national development plans: 20 years plan (RPJPN), five years plan (RPJMN), and annual plans (Rencana Kerja Pemerintah/RKP).

4.1.3 Sustainability inclusion

In Indonesia, sustainable development and blue economy are two fundamental principles adopted in IOP that promote the integration of environmental, social, and economic objectives in ocean development (Government of Indonesia, 2017b). These principles aim to ensure the balance between the ocean development objectives and inter-generational benefits in promoting the protection and responsible use of ocean resources. Moreover, RPJMN 2020-2024 (Government of Indonesia, 2020b) promoted SDGs as one of the four mainstreaming components of the current national development with a further direction to achieve the balance between economic, social and environmental outcomes and impacts. From the sustainable ocean development lens, the IOP Action Plan is deemed to align with the RPJMN; therefore, it is a crucial factor in all SDG elements, as emphasized in the RPJMN and the IOP action plan. The importance of sustainability in ocean development is also highlighted by the advent of the blue economy at the global and regional levels (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2015; Ocean Panel, 2020; European Commission, 2021; Gardera, 2023). A more detailed discussion on blue economy development in Indonesia is provided in the section below.

4.2 Indonesia’s blue economy

The potential of the Indonesian ocean economy has gained awareness in recent years through the development of a series of blue economy documents by Indonesian government institutions (see Figure 2). The sections below elaborate on the conceptualization and institutionalization of the blue economy in Indonesia and how Indonesia attempts to incorporate its implementation within the national development frameworks.

4.2.1 Policy development

The emergence of the blue economy concept in Indonesia can be traced back to Rio+20 when President Yudhoyono revealed the blue economy concept in support of voices from small island developing states in 2012 (Yudhoyono, 2012; Dinarto, 2017). The initial stage of the blue economy development in Indonesia was influenced by Gunter Pauli’s blue economy concept, emphasizing new business models through innovation and entrepreneurship in economic activities (Pauli, 2010; Lukita, 2012; MMAF-RI and DEKIN, 2012; Soesilo, 2014; Poernomo and Kuswardani, 2019). Law Number 32 of 2014 on Ocean Affairs, article 14 provides a legislative reference to the blue economy that was adopted as a principle in marine resources utilization and management (Government of Indonesia, 2014a). Similarly, the blue economy was adopted as one of the principles in the IOP document in 2017 (Government of Indonesia, 2017b). Unfortunately, neither the law nor the ocean policy document clearly elaborates precisely how Indonesia will implement the blue economy principle at the levels of ministerial and provincial/local governments.

At the global and regional levels, Indonesia is among the proponents of the blue economy initiatives. Indonesia is one of the 18 countries that has joined the High-Level Panel, promoting transformations for a sustainable ocean economy (Ocean Panel, 2023). Indonesia also indicated a strong political commitment to supporting the blue economy concept, for example, by participating in regional declarations on the blue economy spearheaded by ASEAN, IORA and East Asia countries (PEMSEA, 2012; IORA, 2017; ASEAN, 2021). Indonesia’s leadership in the blue economy is also evidenced by the establishment of the Archipelagic and Island States (AIS) Forum and the recent initiative in developing the blue economy framework for Indonesia and ASEAN (ARISE+Indonesia, 2023; CMMAI-RI, 2023c).

At the national level, Indonesia has formulated several policy documents to expedite the practice of the blue economy in the country. Unlike IOP, the blue economy documents were developed as policy frameworks that need legal support; otherwise, they cannot be implemented. Also, the formulation of blue economy policies involves external assistance from development partners such as UNDP, UNEP, OECD, SwAM (Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management), and NGOs like EcoNusa (see Figure 2). The Republic of Indonesia SDGs Government Securities Framework (2021) was the first relevant framework that provides initial guidance for sustainable financing schemes in Indonesia (Government of Indonesia, 2021). The SDG Bond covers some blue-focused projects that are eligible for SDG expenditures, including coastal protection, marine biodiversity conservation, and marine spatial planning. Bappenas-RI, in collaboration with the OECD, issued the Blue Economy Development Framework for Indonesia’s Economic Transformation in 2021, providing a solid basis for future blue economy policy planning and implementation in Indonesia (Pane et al., 2021).

Thereafter, in 2022, the Blue Finance Policy Note and the Blue Finance Strategic Document were developed to push forward the implementation of the blue economy (CMMAI-RI and UNDP, 2022; Pratama et al., 2022). The policy note outlines a sustainable finance scheme to fund blue economy activities in Indonesia. The Blue Finance Strategic Document was prepared to bolster and develop Indonesia’s blue economy and further support Indonesia’s capability to meet the SDG targets. Further, in July 2023, Bappenas-RI concluded the development of the Indonesia Blue Economy Roadmap (first edition) through analysis and recommendations from stakeholders to advance maritime sector development in the archipelago (ARISE+Indonesia, 2023). The roadmap aims to guide and accelerate the implementation of policies and programs as part of the economic transformation strategy to realize Indonesia’s Vision 2045 to rise to a high-income economies (Sambodo et al., 2023a). The second edition of the roadmap, revised in December 2023, improved the assessment tool, the Indonesia Blue Economy Index (IBEI), to monitor the progress of blue economy development in all of Indonesia’s provinces (Bappenas-RI, 2023a; Sambodo et al., 2023b). IBEI employs economic, social, and environmental pillars, subsectors and indicators, which are supported by technology and governance as enablers, to measure the performance of blue economy in Indonesia (Mugijayani et al., 2023). The Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF-RI) developed a sectoral version of the blue economy roadmap under the ministry’s responsibility, outlining five blue economy strategies, including: expanding MPAs; implementing quota-based fishery; promoting sustainable aquaculture; managing coastal areas and small islands; and addressing marine debris (Kuswardani et al., 2023).

4.2.2 Implementation strategies

Bappenas-RI has taken the lead in most of Indonesia’s blue economy framework and planning development. While playing a significant role in the conceptual development of the blue economy in Indonesia, CMMAI-RI has been identified as the leading agency in the implementation phase. CMMAI-RI is currently overseeing at least 30 major projects under RPJMN 2020-2024, including land-based infrastructure projects (CMMAI-RI, 2020, 2022b). In addition, twenty-four other institutions with different roles in ocean affairs, including the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs and the Ministry of Finance, contribute to the development and implementation of blue economy policy (Sambodo et al., 2023a). Modelled after the National Plastic Action Partnership (NPAP), the Government of Indonesia in collaboration with development partners initiated the creation of the National Blue Agenda Actions Partnership (NBAAP) in 2022 (United Nations, 2022). NBAAP promotes four pillars of the Blue Action Plan: Blue Health, Blue Food, Blue Innovation and Blue Finance. At present, NBAAP stands as a prominent mechanism driving the advancement of the blue economy in Indonesia. Besides, Bappenas-RI intends to establish a Special Blue Economy Secretariat with a specific assignment to coordinate stakeholders’ cooperation for implementing the blue economy roadmap (ARISE+Indonesia, 2023).

In May 2023, Indonesia continued its commitment to sustainable financing by issuing its first Blue Bond worth JPY 20.7 billion (approximately USD 140 million), nearly ten times the Seychelles Blue Bond of USD 15 million (World Bank, 2018; UNDP Indonesia, 2023). This bond was released through a Public Samurai Bond Issuance, with tenors of 7 and 10 years (MOF-RI, 2023). The second Blue Bond worth JPY 25 billion was recently issued in May 2024, with an additional longer tenor of 20 years (MOF-RI, 2024). The Sovereign Blue Bonds, issued under the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) principles, aim to fund eligible projects that promote the sustainable use of the country’s marine resources and stimulate the emergence of alternative financial instruments that can support and invest in marine-related projects involving private and public actors. The logic of this financial instrument was that it accounted for the limitations in the state budget to support the SDGs agenda (Government of Indonesia, 2021), including sustainable ocean development throughout Indonesia’s vast and diverse archipelago. In the 2023 fiscal year, the blue bond was used to fund underlying projects under three line ministries (MOEF-RI, MMAF-RI, and MPWH-RI), such as mangrove and coral reef rehabilitation, shrimp and milkfish pond rehabilitation, coastal protection, tide control and breakwater development (MOF-RI, 2024; Wibowo, 2024).

4.2.3 Sustainability inclusion

Sustainability is an important lens through which to examine Indonesia’s blue economy development. The country’s perspective towards the blue economy can help us understand how sustainability is embraced. The debate about the meaning of the blue economy and what constitutes activities to be included or excluded from the blue economy sectors (Silver et al., 2015; Voyer et al., 2018a) also creates disagreements, if not different perceptions, by different actors and purposes when defining the blue economy in Indonesia. The first formal definition of the blue economy in Indonesia refers to the explanation of Law Number 32 of 2014 on Ocean Affairs, article 14, which elaborates Indonesia’s perspective on the Blue Economy:

“an approach to improving sustainable marine management and conservation of the sea and coastal resources and their ecosystems in order to realize economic growth with the principles of community involvement, resource efficiency, minimizing waste, and double added value (multiple revenues).” (Translated from Indonesian to English by the main author from the original Law manuscript)

The recent articulation of the blue economy in Indonesia suggests a more nuanced and substantive prioritization of sustainability as found in the Indonesia Blue Economy Roadmap document (Sambodo et al., 2023a), stating the 2045 vision of blue economy development in Indonesia as follows:

“Our diverse coastal and marine resources are sustainably managed through a knowledge-led Blue Economy to create socio-economic prosperity, ensure a healthy marine environment and strengthen resilience for the benefit of current and future generations.”

This new perspective of the blue economy in Indonesia (2023) has promoted science-led policy development and an inter-generational equity component while maintaining the importance of economic and ecological dimensions similar to the earlier definition of 2014. In addition, MMAF-RI perceives that the blue economy seeks to balance all aspect of marine ecosystems which are ecology and economy with an emphasis on safeguarding the sustainability of marine ecosystems as a whole (Kuswardani et al., 2023). MMAF-RI has advanced the blue economy concept by promoting “Ecology as the Commander (Panglima)” in the policy’s development; thus marine conservation is placed as the first pillar of the blue economy policy for sustainable marine and fisheries (Rahman, 2021; MMAF-RI, 2024).

Defining blue economy clusters and sectors in Indonesia is not straightforward, as seen from a wide variety of blue economy clusters and sectors identified by institutions and actors in Indonesia (see Supplementary Table 2). Interestingly, the blue economy roadmap does not consider non-renewable sectors such as oil and gas (Sambodo et al., 2023a), which can be seen as having a detrimental effect on the environmental and social outcomes (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2022). The definition of the blue economy and the sectors it encompasses have impacts on its implementation in national programs and activities. Therefore, all ocean stakeholders at the national level need to have a common and clear understanding about the blue economy concept (Mahardianingtyas et al., 2019).

In the past decade, Indonesia has made significant strides in advancing the sustainable ocean development concept. These actions include the establishment of CMMA-RI, the issuance of IOP with action plans in 2017 and 2022, the formulation of the blue economy frameworks and being actively involved in the global and regional initiatives. These strategic interventions have also positioned Indonesia at the forefront of promoting contemporary ocean governance and management not only at the national stage but also at the regional and global stages. However, owing to its infancy, more efforts are required to make these policies successful. The discussion section below analyzes Indonesia’s interests in sustainable ocean development, including identifying the intricacies and possibilities of transforming ocean sustainability principles and concepts into a reality.

5 Discussion

Indonesia has been making notable efforts towards sustainable ocean development, focusing on the development of a national ocean policy and its blue economy frameworks. These two approaches have been exercised successively and simultaneously to pursue the country’s national interests in promoting a sustainable future in the maritime domain. However, both attempts have yet to mature, and competing interests with national development goals and other priorities overshadow ocean affairs; therefore, sound strategies and priorities are needed to advance sustainable ocean development in Indonesia.

5.1 Competing interests in Indonesia’s sustainable ocean development

For many years, it has been true that land-based economic activities and businesses have historically received more attention and investment in Indonesia; however, there is now a great opportunity for Indonesia to shift the focus and embrace the potential of its ocean economy (Kusumaatmadja, 2005; Monoarfa, 2023b). Indeed, it will take time and resources for Indonesia’s ocean economy to mature and make a significant contribution to the national income. The enormous cost of advancing the ocean economy in Indonesia is a practical hindrance to its development. This can be contrasted with long-established land-based economy sectors, like manufacturing, agricultural and mining sectors, that still dominate the GDP contribution and absorb the majority of the workforce (BPS, 2023a). In a white paper developed by KADIN Indonesia, “Building Indonesia’s tomorrow now” (KADIN Indonesia, 2023), maritime sectors’ development is not receiving as much focus as other sectors, such as manufacturing, regenerative agriculture, and biopharmaceuticals. This implies that the ocean industry’s potential contribution to the economy may be underestimated in comparison to other industries. This makes it challenging for Indonesia to add more focus to the economic development in the maritime sectors.

Despite the tangible improvements that Indonesia has made in recent years (Government of Indonesia, 2016; Oegroseno et al., 2016; CMMAI-RI, 2018; Hadyu and Leonardo, 2018; Cabinet Secretary, 2020; Suherman A. et al., 2020; Suherman A. M. et al., 2020), its ocean-based development progress is still in its growth or pre-development stages (compare the Levitt, 1965; Cox, 1967; Blue Growth Consortium, 2012; MCG, 2012). The evidence supporting this observation is clear: limited scale of ocean economic activity; inability to compete in the global market (e.g. fisheries product rejection); low productivity and reliance on imported materials (e.g. aquaculture and shipbuilding), slow maritime GDP growth (lower than national GDP growth); limited research and innovation budget and outcome; and lack of investment (e.g. offshore energy project) (Pane et al., 2021; CMMAI-RI and BPS, 2023; Sambodo et al., 2023a, 2023b).

Attempting to double maritime GDP contribution from 7.6% in 2025 to 15.0% in 2045 is a complex and challenging task for Indonesia (Sambodo et al., 2023a; Bappenas-RI, 2023b). Not counting major economic contributors like oil and gas puts more pressure on other sectors, such as fisheries and potentially ocean renewable energy, which are currently underdeveloped and underutilized, for example, the utilization rate of ocean renewable energy was as low as 0.002% in 2015 (Government of Indonesia, 2017c, Annex 1; Pane et al., 2021). Considering the current capacity, human resource readiness, and ecosystems for advancing renewable energy sources such as offshore wind or tidal waves, the forementioned 20-year timeline may not be realistic for Indonesia to become a competitive ocean energy producer, unless transformational change is adopted. Similarly, Indonesia’s seafood industries could struggle to compete, comply, enter the concentrated international market, and reach the same level of success as other seafood industries such as Maruha Nichiro and Thai Union (DG-SANTE, 2017; Virdin et al., 2021).

The goal to graduate from the middle-income trap creates complexity for Indonesia to balance its economic growth with environmental and societal dimensions of sustainability. Developing countries, including Indonesia, face challenges in advancing national development and achieving the goal of a high-income country. Sustainable ocean development in Indonesia poses a dilemma as Indonesia must balance the need for economic growth with the importance of ecological and social sustainability. Indonesia faces the challenge of balancing these competing interests to ensure that the ocean and coastal spaces are used sustainably and equitably for the benefit of both present and future generations. The United Nations Resident Coordinator in Indonesia (Julliand, 2022) applauded that:

“…while we need to look at it from the blue economy viewpoint, in order to have better economic development and prosperity, this has to aligned as well with the ideal of respect to the ocean, the conservation and protection, this has to go hand in hand…”

Indonesia’s interests in ocean development are centered around the sustainable utilization of marine resources as aligned with the principle of economic democracy, following the guidance provided by the 1945 constitution (articles 25A and 33). Today, the sustainability of ocean development is under threat; therefore, caring for ocean health and integrity while sustainably utilizing its non-renewable marine resources are the most significant interests of sustainable ocean development in Indonesia. During High Level Panel on sustainable ocean economy event in 2019, Indonesia stated the importance of maintaining a fine balance between promoting economic growth and protecting the ocean and its resources (MOFA-RI, 2019). Acknowledging and identifying the challenges and having good ideas to address them is not enough. A clear strategy is necessary to implement solutions to identified challenges.

5.2 Making it work: avoiding the “policy on paper” trap

Too often, countries possess well-crafted policies on paper but struggle with proper implementation. Indonesia must be cautious of not falling into this trap and instead focus on enhancing policies that have proven effective. Relying solely on theoretical policies on paper or adopting policies just because other countries have taken similar approaches will not yield the desired outcomes. Hrebiniak (2006) identified several factors that can hinder the effective implementation of policies, including: resistance to change; poorly defined strategies; a lack of guidance; inadequate information sharing among stakeholders responsible for implementation; conflicting interests and power structures; and unclear responsibility and accountability for the implementation of decisions. Successful policy implementation requires overcoming such obstacles to achieve intended outcomes for constituents. Designing a good policy with effective implementation strategies will help Indonesia avoid the “policy on paper trap” by addressing four key areas (strategic priorities), which are discussed below.

First, achieving full integration in the institutional mechanisms that deliver the policy is critical to optimizing the governance and management of ocean activities in Indonesia (World Bank, 2021; Keliat et al., 2022; Rudi, 2023; Siswanto and Rosdaniah, 2023; Sambodo et al., 2023a; Monoarfa, 2023b; CMMAI-RI, 2023e). Suherman et al. (2020) identified that regulatory fragmentation causes inefficiency and contributes to sectoral competition that undermines governance effectiveness. The decision to designate CMMAI-RI as the coordinating agency for maritime affairs follows Underdal’s (1980) recommendation regarding an indirect institutional strategy for achieving integration. Theoretically, the roles of intellectual strategies, such as socialization, education, training, and direct imperative approaches, will become increasingly important to gain full integration in ocean governance and management. CMMAI-RI (2023e) highlights that future institutional arrangements for ocean governance in Indonesia must be fit for purpose, solve the problems, and not just incur costs. The ideal is that all relevant line ministries need to translate the national policy such as blue economy framework and roadmap into their sectoral plans, but at present, only MMAF-RI has taken that initiative. This shortcoming highlights the importance of coordination, communication and consultation in cross-sectoral policy development and implementation. To achieve integration, all planning and implementing agencies must work collaboratively in ensuring policy coherence across different sectors and jurisdictions. Therefore, clarity on the rights and responsibilities of institutions in Indonesia’s ocean governance is crucial for better vertical and horizontal integration in the whole of government and national approaches.

The second crucial area Indonesia needs to focus on is preparing the future maritime workforce through qualified maritime education and training systems. The current education system in Indonesia does not provide enough attention to maritime education (Sarjito, 2024), resulting in limited success in the efforts to incorporate maritime subjects into the school curriculum. There is a need to integrate ocean literacy programs into educational and public policy domains as the current scholarly interest in ocean research in Indonesia is relatively limited (Asikin et al., 2023; Jaya, 2023; Syakti, 2021). Equipping the maritime workforce with knowledge and skills is critical (Hendarman et al., 2024). Of crucial importance is ensuring that the education and training supply matches the demands for skilled workers in maritime industries for proper alignment between the two. This can only be achieved through collaboration from all stakeholders, including policymakers, educators, employers, and individuals (Siswanto and Rosdaniah, 2023). By working together, all maritime stakeholders help ensure the maritime workforce remains strong and competitive in the global economy. Importantly, ocean governance is not about managing ocean resources, such as fish, but about people’s behavior towards them (Hilborn, 2007). Fielding the maritime sector with qualified workforces will be a significant enabler for Indonesia’s ocean development in the future.

The need to achieve the right balance of economic, social, and environmental objectives of sustainable ocean development in Indonesia is the third key area for future policy improvement (World Bank, 2019, 2021; Pane et al., 2021; Sambodo et al., 2023a). The unsustainable practice and unoptimized resources management, such as overfishing and mangrove loss (Ferrol-Schulte et al., 2015; Pane et al., 2021; World Bank, 2021; Quevedo et al., 2023) are warnings for Indonesian policymakers to reconsider the meaning of sustainability in the implementation of the blue economy. Blue economy development is not solely focused on increasing economic metrics, for example, fisheries catch, but instead on creating more value from the same or a smaller number of catches (Sigfusson, 2020). It is crucial to prioritize sustainable practices over short-term gains to ensure the long-term viability of the blue economy. There are many tasks to be completed in the effort to balance the interest of economic growth with its social and environmental consequences, which are vital for sustainable ocean development in Indonesia. The concept of decoupling economic growth from environmental and societal impacts provides a viable solution to advancing sustainable ocean development in Indonesia (Vadén et al., 2020; Tominaga, 2023). By taking a forward-thinking as well as precautionary approach, one can cultivate a thriving blue economy that benefits both present and future generations while mitigating negative externalities of economic activities in the ocean.

Lastly, Indonesia must take into account threats and risk assessment of ocean activities, which is currently lacking in ocean policy and blue economy documents (e.g., framework, road map, action plan). Despite its usefulness in forward-looking policy design (Ahlqvist et al., 2012), scholars discovered that the roadmap method, with its future vision, pathways and action plan, often pays insufficient attention to the risk and uncertainty aspects of future policy planning (Miedzinski et al., 2022). Policy and planning documents often encompass assumptions and targets that exceed the financial and administrative capacities for execution and management. This type of policy planning approach creates an elusive situation when unintended consequences occur, and it is not easy to measure and monitor the cumulative impacts and trade-offs of the policies and plans (Stephenson et al., 2019; Winther et al., 2020). A tangible short-term gain such as economic growth may not represent the total outcomes and costs to society and nature. Thus, ocean policymakers need to consider the potential pitfalls by conducting threat and risk assessments against all pillars of ocean sustainability. The threat and risk assessment (TARA) framework developed by the New South Wales government provides a good model for such an assessment approach (MEMA, 2013, 2017). The TARA aims to identify the effects of various ocean activities on environmental, social, and economic benefits expressed in the level of potential consequences and the likelihood of their occurrence. The output can then be used to improve the management of the ocean estate (MEMA, 2017; Gollan et al., 2019). Integrating threat and risk assessment into Indonesia’s ocean and blue economy policies will provide a more thorough understanding of the impacts and implications of policy actions and introduce a cautious approach to policy design that leads to better decision-making in achieving sustainability goals.

Paying closer attention to and taking action on the four key areas described above as strategic priorities for future development will enable Indonesia to unlock valuable opportunities for sustainable economic growth, environmental stewardship, social justice, and equity. They are “the Achilles’ heels” of sustainable ocean development in Indonesia, where the absence of one will make it difficult for the policy to achieve all sustainable objectives. Therefore, a well-designed ocean policy and blue economy plan with an effective implementation strategy are vital to realizing Indonesia’s maritime vision.

6 Conclusion

This study set out to identify Indonesia’s interests in advancing sustainable ocean development initiatives at the national level and the approaches taken to translate those interests to actual benefits of ocean governance and management in Indonesia. Indonesia’s interests in sustainable ocean development focus on the aspiration to establish the country as the Global Maritime Fulcrum, which was built on its history of success in maritime trading. The study has shown that out of competing interests in the ocean and coastal space, upholding the ocean’s health and ensuring sustainable use of ocean resources are poised to become Indonesia’s most vital interests in achieving sustainable ocean development. In the absence of these two critical elements, the aspirations of growth and sustainability will not be achieved.

The analysis also confirms that Indonesia’s ocean policy and a series of blue economy initiatives seek to unlock new sources of economic growth while upholding sustainability. These have opened a window of opportunity to better manage Indonesia’s vast ocean areas and accelerate the implementation of the GMF’s vision (Government of Indonesia, 2017b). They also provide a sound foundation for Indonesia’s ocean governance based on good political will, policy and legislative bases, institutional arrangements, and financial schemes. Both policy approaches are relatively new and have yet to reach maturity as generally land-based economic sectors have overshadowed Indonesia’s aspirations to advance oceanic development.

A detailed assessment of the sector-by-sector development stage of Indonesia’s ocean economy activity lies beyond the scope of this paper. Similarly, an in-depth analysis of policy coherence and coordination within the Indonesian governance system and across different ocean sectors was not covered in this paper. Both subjects warrant further research. Furthermore, this study is limited by its method of analyzing the main policy documents and additional references based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria set out in Section 2. All filtered references are listed in Supplementary Table 4. Future improvements of the analysis may be achieved through a systematic literature review.

Indonesia’s strategic initiative to institutionalize and operationalize a national ocean policy and blue economy plans is just the beginning of its journey toward sustainable ocean development. Indonesia has an excellent opportunity to realize the GMF’s vision; but this will only happen when an integrated approach to ocean governance supported by effective implementation strategies is in place. To achieve its maritime vision, this study recommends that Indonesia must prioritize the four following actions: (1) develop a well-designed policy characterized by fully integrated and coherent policies with actionable plans supported by a fully integrated institutional framework; (2) prepare and manage the human capital in the maritime sector as its most valuable asset in order to translate policies into actions which is crucial for Indonesia; (3) clearly articulate the environmental and social objectives of the blue economy policy and strategy framework; and (4) estimate the benefits, threats, and risks of all ocean activities against all of the sustainability pillars. When these conditions come together, Indonesia will be well-positioned to navigate towards its maritime destiny by unleashing the promise and potential of its maritime capacities.

Statements

Author contributions

LW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MV: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Research funding was provided by a scholarship from the University of Wollongong. Fund for open-access publication was provided by the Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS) and the Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus for supporting the research. Special thanks are also due to Genevieve Quirk for her contribution to the proofreading part.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1401332/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1The main ocean policies and blue economy documents.

Supplementary Table 2Blue economy sectors by different actors.

Supplementary Table 3List of acronyms and abbreviations.

Supplementary Table 4References List.

References

1

ADB (2024). Proposed programmatic approach and policybased loan for subprogram 1 Republic of Indonesia: reducing marine debris program (Manila, Philippines: Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors, Issue. A. A. D. Bank). Available at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents/57018/57018-001-rrp-en.pdf.

2

Adi T. R. (2018). Maritime culture empowerment under Indonesian ocean policy. J. Ocean Culture1, 102–117. Available at: https://oak.go.kr/central/journallist/journaldetail.do?article_seq=21983.

3

Adrianto L. (2022). Blue Economy Development Index (BEDI) - Measuring the Progress of Sustainable Blue Economy International Conference on Sustainable Ocean Economy and Climate Changes Adaptation, Vietnam. Available at: https://conference.undp.org.vn/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/UNDP-Blue-Economy-Workshop-BEDI-12-05-22.pdf.

4

Agoes E. R. (1991). Indonesia and the LOS convention: Recent developments in ocean law, policy and management. Mar. Policy15, 122–131. doi: 10.1016/0308-597X(91)90011-Y

5

Agoes E. R. (1997). Current issues of marine and coastal affairs in Indonesia. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law12, 201–224. doi: 10.1163/15718089720491558

6

Ahlqvist T. Valovirta V. Loikkanen T. (2012). Innovation policy roadmapping as a systemic instrument for forward-looking policy design. Sci. Public Policy39, 178–190. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scs016

7

Alamsjah M. A. (2017). An overview of the seaweed cultivation in several countries: Technology and challenge 1st International Conference Postgraduate School Universitas Airlangga: Implementation of Climate Change Agreement to Meet Sustainable Development Goals (ICPSUAS 2017), Paris. Available at: https://www.atlantis-press.com/article/25891240.pdf.

8

Alverdian I. (2024). Indonesia’s Maritime Policy from Independence To 2019: Political Culture and Maritime Geography. 1st ed (Oxford, UKTaylor & Francis Group).

9

Anna Z. (2023). Unlocking Indonesia’s potential through a blue economy (360info). Available at: https://360info.org/unlocking-Indonesias-potential-through-a-blue-economy/ (Accessed 10 January 2024).

10

ARISE+Indonesia (2023). Menavigasi kemakmuran: peta jalan ekonomi biru Indonesia menuju pertumbuhan berkelanjutan dan pelestarian laut untuk generasi sekarang dan mendatang (ARISE+ Indonesia). Available at: https://ariseplus-Indonesia.org/id/kegiatan/perspektif/menavigasi-kemakmuran-peta-jalan-ekonomi-biru-Indonesia-menuju-pertumbuhan-berkelanjutan-dan-pelestarian-laut-untuk-generasi-sekarang-dan-mendatang.html (Accessed 20 November 2023).

11

Arsana I. M. A. (2023). Era baru batas maritim Indonesia Malaysia (Kompas). Available at: https://www.kompas.id/baca/opini/2023/07/06/era-baru-batas-maritim-Indonesia-Malaysia (Accessed 10 January 2024).

12

ASEAN (2021). ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on the Blue Economy (Brunei Darussalam: ASEAN). Available at: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/4.-ASEAN-Leaders-Declaration-on-the-Blue-Economy-Final.pdf.

13

Asikin N. Suwono H. Bambang Sumitro S. Dharmawan A. Qadri Tanjung A. (2023). Trend ocean literacy research in Indonesia: A bibliometric analysis. Bio Web Conferences79, 13002. doi: 10.1051/bioconf/20237913002

14

Ave J. B. (1989). ‘Indonesia’, ‘Insulinde’ and ‘Nusantara’; Dotting the i’s and crossing the t. Bijdragen tot taal- land- en volkenkunde145, 220–234. doi: 10.1163/22134379-90003252

15

Bappenas-RI (2014). Rencana Aksi Nasional Adaptasi Perubahan Iklim (RAN-API)/National Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI).

16

Bappenas-RI (2018). Kaji ulang RAN API 2018 proyeksi iklim laut (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI). Available at: https://lcdi-Indonesia.id/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Proyeksi-Iklim-Laut.pdf.

17

Bappenas-RI (2020). Laporan Kajian Lingkungan Hidup Strategis (KLHS) Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional (RPJMN) 2020-2024 (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI). Available at: https://lcdi-indonesia.id/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Laporan-Kajian-Lingkungan-Hidup-Strategis-Rencana-Pembangunan-Jangka-Menengah-Nasional-KLHS-RPJMN-2020-2024.pdf.

18

Bappenas-RI (2023a). Indonesia development forum 2023 (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tO-Qu7UFBVw. [YouTube].

19

Bappenas-RI (2023b). Indonesia emas 2045 - rancangan akhir RPJPN 2025-2045 (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI, Sekretariat RPJPN 2025-2045). Available at: https://Indonesia2045.go.id/ (Accessed 2 November 2023).

20

Bappenas-RI (2023c). Laporan kajian lingkungan hidup strategis (KLHS) rencana pembangunan jangka panjang nasional (RPJPN) 2025-2045 (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI). Available at: https://lcdi-Indonesia.id/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Laporan-KLHS-RPJPN-Tahun-2025-2045.pdf.

21

Bappenas-RI (2023d). Penduduk berkualitas menuju Indonesia emas: kebijakan kependudukan Indonesia 2020–2050 (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI). Available at: https://perpustakaan.bappenas.go.id/e-library/file_upload/koleksi/migrasi-data-publikasi/file/Policy_Paper/Buku%20Penduduk%20Berkualitas%20Menuju%20Indonesia%20Emas%20%20310522%20.pdf.

22

Bappenas-RI (2023e). Seminar Penguatan Tata Kelola Kelautan Berkelanjutan dan Berkeadilan dalam Rencana Pembangunan Nasional (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xj5DAvryyjY. [YouTube].

23

Bappenas-RI LCDI (2021). Executive summary - climate resilience development policy 2020-2045 (Jakarta, Indonesia: Bappenas-RI & L. C. D. I. (LCDI). Available at: https://lcdi-Indonesia.id/dokumenpublikasipembangunanberketahananiklim/.

24

Beale P. (2006). From Indonesia to Africa: Borobudur ship expedition. Ziff J.3, 17–24. Available at: http://www.swahiliweb.net/ziff_journal_3_files/ziff2006-04.pdf.

25

Bellwood P. (2017). First Islanders: Prehistory and Human Migration in Island Southeast Asia (Incorporated: John Wiley & Sons).

26

Bennett N. J. Blythe J. Cisneros-Montemayor A. M. Singh G. G. Sumaila U. R. (2019). Just transformations to sustainability. Sustainability11 (14), 1–18. doi: 10.3390/su11143881