Abstract

The Black Sea ecosystem faces significant challenges due to climate change and human activities. Despite this, the opportunities and potential of its Blue Economy and the role of Turkish stakeholders in the key sectors have not been well documented. To define the needs of the Black Sea’s Blue Economy and outline existing problems, a workshop entitled “Engaging Stakeholders: Trabzon Multi-Actor Forum” was held in Trabzon (Türkiye) in November 2022. Stakeholders from the research sector, academia, civil society, industry, business, competent authorities, and government shared their thoughts on various sectors of the Blue Economy, covering 17 areas. They discussed political, environmental, social, technical, legal, and economic aspects, revealing opportunities, challenges, and areas where more research is needed. This meeting provided valuable insights, indicating that efficient collaboration with stakeholders could lead to effective solutions and strategies, helping to improve the Blue Economy in the Black Sea region.

1 Introduction

The Black Sea is a semi-enclosed basin with unique hydrological and environmental conditions, characterized by stratified water layers that restrict oxygen circulation, resulting in anoxic conditions below 200 metres (Murray et al., 1989; Bakan and Büyükgüngör, 2000; Rudneva and Petzold-Bradley, 2001; Sezgin et al., 2017; Radulescu, 2023). This makes the basin highly susceptible to external stressors such as nutrient inflows and pollution, which intensify eutrophication and create hypoxic zones (Sezgin et al., 2017; Hidalgo et al., 2018; Vasilica et al., 2023). Significant river systems, including the Danube, Dniester, and Dnieper, further influence its hydrology by transporting both nutrients and contaminants into the sea (Bakan and Büyükgüngör, 2000; Sezgin et al., 2017; Alkan, 2019).

The region faces numerous environmental challenges, including overfishing, habitat degradation, marine litter, and climate change impacts, distinguishing the Black Sea Blue Economy from other regions (Oguz et al., 2012; Oral, 2013). Despite these obstacles, the Black Sea holds significant potential for sustainable Blue Economy growth, particularly in sectors such as marine aquaculture, offshore renewable energy (wind, wave, and solar), sustainable tourism, maritime transport, and multi-use platforms (Schultz-Zehden et al., 2018; Melikidze et al., 2019; Bennett et al., 2021; Martínez-Vázquez et al., 2021). The basin’s strategic location as a bridge between Europe and Asia enhances its trade and economic opportunities (Aydin, 2005; Armonaite, 2020). However, realizing this potential hinges on overcoming basin-specific challenges such as inadequate infrastructure, uneven capacities among coastal nations, and geopolitical tensions while fostering sustainable development through ecological preservation and stakeholder collaboration (Oguz et al., 2012; Hidalgo et al., 2018; Afanasyev et al., 2020; Armonaite, 2020; Vasilica et al., 2023).

The EU’s EMODnet Black Sea Checkpoint project identified 11 key challenges relevant to advancing the Blue Economy, such as sustainable development of offshore industries, fisheries management, eutrophication, and climate change impacts (Palasov et al., 2019). It also highlighted the importance of emergency response to oil spills and biodiversity preservation through Marine Protected Areas (Martín Míguez et al., 2019). Platforms like EMODnet and Copernicus provide accessible, high-quality marine observation data that support integrated approaches to balancing economic and environmental priorities (Calewaert et al., 2016; EMODnet, 2024).

The Turkish coastline of the Black Sea plays a pivotal role in the region’s Blue Economy, supporting diverse activities such as small-scale fisheries, aquaculture (notably trout farming), maritime transport, coastal tourism, and renewable energy projects (Candan et al., 2007; Karamushka, 2009; Oguz et al., 2012; Afanasyev et al., 2020; Seyhan et al., 2022). Coastal tourism, driven by the area’s natural and cultural assets, significantly contributes to the local economy (DOKA, 2023). However, like other parts of the Black Sea, this region faces challenges, including fragmented governance frameworks, underdeveloped offshore energy infrastructure, overexploitation of fish stocks, pollution from land-based activities, and limited cross-sectoral collaboration (Candan et al., 2007; Afanasyev et al., 2020; Massa et al., 2021; Dürrani et al., 2022; Dürrani et al., 2024). Addressing these issues offers an opportunity for Turkish stakeholders to align with EU sustainability goals and drive progress through cross-border initiatives (Açıkmeşe, 2012; Yazgan, 2017; Council of the European Union, 2024). Efforts to enhance collaboration among researchers, policymakers, and private sector actors can drive innovation in renewable energy, aquaculture, and other sectors, fostering sustainable growth in the Black Sea’s Blue Economy (Hoerterer et al., 2020; Aivaz et al., 2021).

This workshop, titled “Engaging Stakeholders: Trabzon Multi-Actor Forum” was organized with the aim of bringing together local stakeholders from various sectors to engage in in-depth discussions on the diverse opportunities and challenges associated with the Blue Economy in the Black Sea region. The primary objective was to identify key sectors within the framework of the Blue Economy, while the second involved scrutinizing the various barriers that currently hinder its development. Additionally, the workshop addressed gaps in collaboration and understanding across sectors, exploring strategies to bridge these divides, with particular emphasis on incorporating the perspectives of Turkish stakeholders and highlighting their critical role in advancing the region’s Blue Economy.

2 Materials and methods

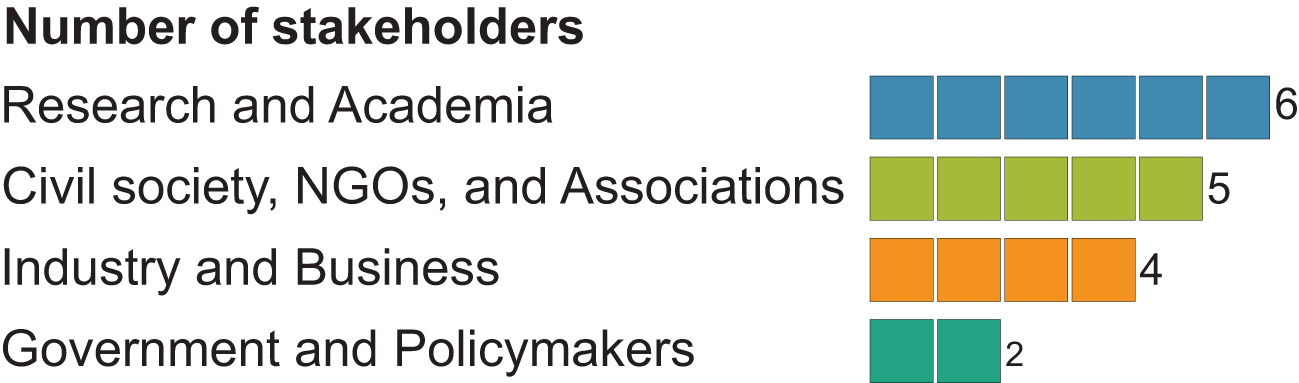

The workshop was designed to promote in-depth dialogue and was deliberately restricted to 17 carefully selected participants to ensure fruitful discussion and avoid an impersonal mass event (Figure 1). These participants represented a broad spectrum of sectors crucial to the Blue Economy, including industry and business (i.e., shipbuilding, marine aquaculture, and tourism), governmental and policymaking bodies (i.e., focusing on fisheries research and coastal safety), civil society, non-governmental organizations, and professional associations (i.e., covering fisheries cooperatives, environmental and agricultural engineering, and marine environment protection), as well as the research and academic community (i.e., fisheries, aquaculture, marine sciences, and biology).

Figure 1

Illustrates the distribution of stakeholder groups.

2.1 First session

The first interactive session provided stakeholders with three weighted votes, scored as 1, 2, and 3, to allocate among three of the 17 Blue Economy sectors to assess their importance and the immediate need for action (Figure 2).

Figure 2

A stakeholder to allocate votes to any three of the 17 Blue Economy sectors to assess their importance and immediate need for action.

2.2 Second session

The second interactive session focused on the top eight sectors that received the most votes. Stakeholders were then asked to provide feedback on sticky notes addressing the political, environmental, social, technical, legal, and economic challenges relevant to these sectors (Figure 3). The feedback was then anonymously shared with the panel for further discussion to identify and validate the needs and gaps.

Figure 3

A stakeholder providing feedback on sticky notes.

2.3 Summarization by authors

The authors gathered and refined the feedback from the workshop into a summary that outlined key needs in the Blue Economy. They clearly identified what stakeholders needed and where there were shortfalls in meeting these needs. This summary helps in understanding the sector better, guiding focused actions, and planning to bridge these gaps, aligning with Blue Economy’s broader objectives.

3 Results

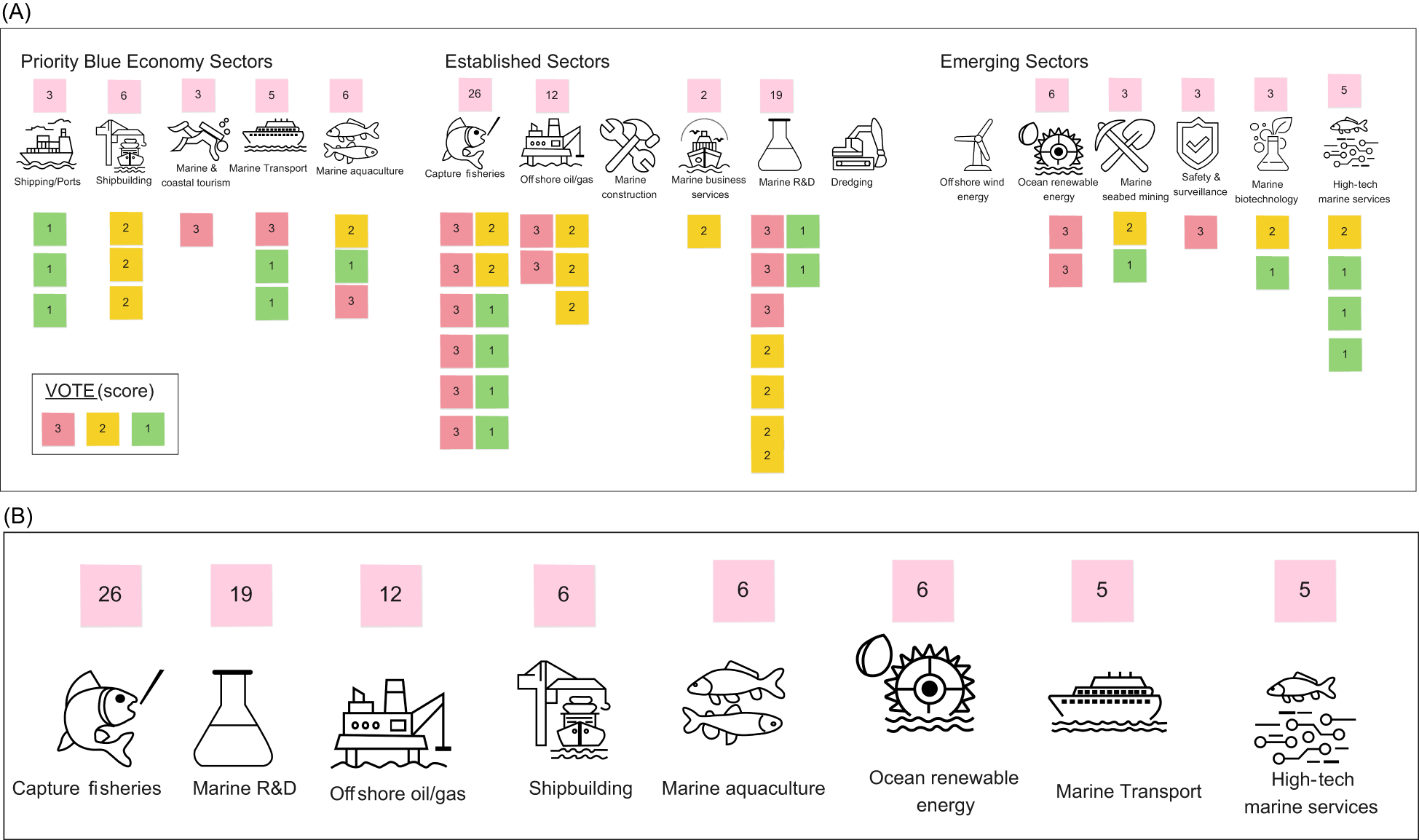

Out of the 17 Blue Economy sectors, three of the sectors, viz., Marine construction, dredging, and offshore wind energy, did not receive any vote from the stakeholders (Figure 4A). The highest score was received for capture fisheries, with 26 scores, and marine R&D, with 19, followed by offshore oil/gas, with 12 scores (Figure 4B).

Figure 4

(A) Scores assigned by stakeholders to various Blue Economy sectors in the Black Sea based on prioritization. (B) Illustration of the prioritization of Blue Economy sectors in the Black Sea based on the highest scores received.

3.1 Political

The Blue Economy faces numerous challenges and opportunities that are often influenced by political factors (Table 1). In the capture fisheries industry, political pressures and deficits in effective governance, enforcement, and long-term planning often prioritize short-term gains over scientific advice, suggesting the need for science-based decision-making by organizations, legislators, and academia rather than politicians. This includes the implementation of fishing bans and laws grounded in scientific research, comprehensive policies, regular inspections, and proper training. For marine research and development (R&D), the development of legal and policy frameworks in collaboration with experts is crucial to avoiding political interference, with an emphasis on increased state focus and funding. The offshore oil and gas sector requires strengthening political frameworks and continuous research support to enhance the Black Sea region’s influence and economic growth. The shipbuilding industry lacks adequate political support, which requires principled policies and targeted support. The marine aquaculture and ocean renewable energy sectors also suffer from insufficient political support, highlighting the need for principled policies and efficient collaboration for sustainable development. Marine transport highlights the need for political support and the resolution of geopolitical challenges for effective maritime transport. High-tech marine services, such as offshore renewable energy projects like wind farms, smart shipping technologies, autonomous underwater vehicles for marine research, and advanced aquaculture systems, require unbiased political support and the development of sustainable technologies. Across these sectors, the common thread is the need for depoliticizing management, enhancing political infrastructure for support, and prioritizing sustainable practices to ensure the long-term viability of the Blue Economy.

Table 1

| SECTOR | Political | Environmental | Social | Technical | Legal | Economics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPTURE FISHERIES | 1. Political pressure and deficits influence the fisheries industry, often prioritizing short-term gains over scientific advice. 2. Fisheries management should be in the hands of organization legislators, and academia, rather than politicians, to ensure that decisions are science-based. 3. The application of fishing bans and laws should be grounded in scientific research. without political interference. 4. There is a need for comprehensive policies, regular inspections, and proper training within the sector. 5. The Black Sea’s fisheries management requires a holistic approach by all stakeholders, with a focus on sustainable practices and preventing the catch of small, immature fish. 6. Rules governing the fisheries sector should be clearly defined and enforced, keeping politics at bay to prioritize ecological sustainability. The non-implementation of existing laws and the prevalence of illegal fishing activities are often due to political challenges, underscoring the need for depoliticizing fisheries management. |

1. A weak environmental culture and insufficient protection measures lead to environmental degradation. 2. The lack of clear regulation results in environmental overload and pollution, especially in urban areas, hydroelectric power plants, and mining. 3. Environmental issues are exacerbated by a lack of education and awareness. 4. The fishing sector is significantly impacted by environmental factors, including pollution, which reduces fish populations and sea clarity. 5. Critical environmental challenges include climate change, the spread of invasive species, and the decline in the diversity and abundance of commercial fish species. 6. There is an urgent need for stringent environmental regulations and proper implementation to prevent further damage. 7. Pollution (both domestic and industrial), the impact of hydroelectric power plants, climate change, overfishing, and harmful fishing practices disturb the environmental balance and harm marine ecosystems. |

1. Fisheries provide significant job opportunities that contribute to employment. 2. There is a need for enhanced coordination between research activities and the various sectors within fisheries. 3. Efforts are being made to encourage increased fish consumption by the public. 4. The fisheries sector has a robust social dimension, showing potential for internal development and growth. 5. Fisheries generate social returns at both regional and national levels. 6. A notable conflict between artisanal and industrial fisheries highlights social tensions within the sector. |

1. The unique ecosystem of the Black Sea necessitates careful consideration of technology use because methods suited for open seas may be harmful. 2. There is an urgent need to curtail the use of certain fishing technologies to prevent further harm to fish populations. 3. Advanced fishing technologies and their unmonitored use exert excessive pressure on fish stocks. 4. Implementing monitoring and tracking systems can enhance sustainable fishing practices. 5. Conscious fishing practices should be promoted, including the use of appropriately powered vessels and gear tailored to specific fish types to minimize ecological impact. 6. High-tech fishing methods contribute to the decline of certain fish species by enabling overfishing. 7. The proliferation of ships equipped with modern technology, such as fish finders, necessitates stricter regulation of ship licenses to combat overfishing. The development of new fishing technologies in the digital age offers potential for innovation, but it also requires careful regulation to ensure sustainability. |

1. Laws and quotas for specific species should be established based on thorough research to ensure sustainable fishing practices. 2. There is a need for re-evaluating and strengthening control mechanisms to effectively enforce regulations. 3. A significant issue in fisheries is the inadequate implementation and enforcement of existing legal regulations and sanctions, often due to insufficient regular cheques. 4. The influence of lobbies over science in legislative processes undermines the effectiveness of laws designed to protect fisheries. 5. Despite having comprehensive legal frameworks, the lack of consistent and fair inspections compromises the effectiveness of these regulations. 6. Economic sustainability in marine fisheries is challenged by the absence of legal scaling, emphasizing the necessity for everyone to adhere to established regulations. Inadequacies in enforcing fisheries regulations, combined with insufficient penalties, contribute to non-compliance and intensify legal deficiencies in the sector. |

1. Transitioning from fuel to electrical energy is essential for addressing the energy challenges faced by the fisheries sector. 2. The Black Sea is economically significant, with the country deriving 60-70% of its fisheries from this area, indicating the need for region-specific vessel standards and limitations on ship dimensions and machinery. 3. The fisheries economy is struggling because of insufficient economic strategies and support, highlighting the need for recovery and enhanced economic perspectives. 4. Despite its considerable contribution to the national economy and public welfare, the fisheries sector faces challenges such as lack of financial support, especially in implementing fishing quotas. 5. Economic inefficiencies in fishing products and the issue of overfishing driven by excessive profit motives underscore the need for sustainable practices. 6. The economic importance of fishing for local communities and countries emphasizes the need for policies that support both the environment and livelihoods that are dependent on fisheries. Supporting the culture of mussels and oysters is recommended to diversify and strengthen the economic base of the fisheries sector. |

| MARINE R&D | 1. Develop legal and policy frameworks for marine research in collaboration with experts to avoid political interference. 2. The lack of political support and funding for marine research indicates misalignment of national priorities. 3. Increased state focus and funding are essential to overcome political barriers and enhance marine research. 4. Integrate marine research into strategic plans using political support to achieve more effective outcomes. 5. Economic limitations and lack of facilities hinder marine research progress, necessitating better funding. International collaboration on marine research can mitigate political issues and encourage sustainable resource use. |

1. Marine research is essential for ecosystem health but lacks depth, underscoring the urgency for better studies to combat marine pollution. 2. Rising marine pollution demands thorough research to gauge its effects and identify remedies. 3. A notable lack of studies exists on safeguarding marine environments from construction and pollution. 4. Research is key to overcoming environmental challenges, necessitating further efforts to diminish pollution and boost ecosystem resilience. 5. The rapid resolution of mucilage in the Sea of Marmara in 2022 highlights the impact of focused marine research. 6. Effective environmental policies and enhanced research are vital for safeguarding future ecosystems. The negative impact of marine pollution on fish and ecosystems highlights the need for extensive environmental data. |

1. Public apathy toward marine research is widespread. 2. Marine research’s social benefits are significant but underappreciated. 3. The sea offers potential for community engagement, yet it is often overlooked. 4. A lack of social engagement in marine conservation and research. Communicating marine research’s value to the public is challenging. |

1. Türkiye faces a technological gap in marine research because of limited access to advanced tools. 2. Lack of investment in technology impedes marine research progress. 3. Researchers need but lack access to emerging technologies. 4. Urgent technological support and funding must enhance research capabilities. 5. Marine technological research and its dissemination to authorities are inadequate. 6. Up-to-date methods and equipment are essential for effective marine ecosystem monitoring. Insufficient research equipment hinders thorough and accurate marine studies. |

1. Improved technical equipment is crucial for the application of legal frameworks in marine research. 2. Although existing laws are adequate, updates and new agreements are essential for progress. 3. Revising legal regulations is necessary to align with marine research advancements. There is a need to enact and rigorously audit laws to strengthen marine research and compliance. |

1. Marine research faces funding and resource shortages that underscore economic challenges. 2. Increased financial investments are crucial to sustainable and economically viable fisheries. 3. The need for adequate budgeting for marine research is underscored. 4. The sector faces limited support, researcher scarcity, and financial constraints. 5. Economic shortfalls hinder scientific study funding, necessitating greater budget support. Strategic research with detailed cost-benefit analyses is essential to achieve optimal efficiency and results. |

| OFFSHORE OIL/GAS | 1. Strengthening the political framework is crucial for offshore oil and gas exploration in the Black Sea, emphasizing the need for targeted energy research to assert regional influence. 2. Continuous support and increased research in Türkiye’s marine Blue Economy are essential for its development. 3. New policies should be developed to facilitate studies and initiatives in areas such as the Blue Economy, highlighting its significant potential for regional economic growth. Political commitment to gas exploration and sustainability is vital, along with the need for international cooperation to achieve these objectives. |

1. Geographic suitability for offshore operations requires better evaluation. 2. Environmental considerations, including legal assessments of environmental impacts, are crucial for offshore activities. 3. Mitigating environmental damage caused by oil and gas extraction is essential, and it is important to acknowledge the risks associated with such extraction. Research on the use of liquefied CO2 to fill underground voids after extraction highlights innovative environmental management strategies. |

1. Gas and oil production is expected to positively transform social life through economic contributions. 2. Advancements in the economy and technology in these sectors will boost social welfare. 3. Increasing public awareness of the significance of offshore activities is crucial. 4. Exploration in these areas introduces new economic opportunities for livelihoods. Educating the public about the benefits of these developing sectors can mitigate opposition. |

1. New technologies will enhance the efficiency of offshore exploration. 2. Energy research should prioritize technological tools for improvement. 3. High-value hydrate gases should be evaluated using advanced technology. 4. Advanced researchers are required to focus on these areas. Sustainability in offshore operations requires advanced technology. |

Legal readiness, both domestically and internationally, is crucial for offshore oil and gas exploration. | 1. Offshore oil and gas exploration is vital to economic growth and can significantly contribute to national development. 2. Economic research in this area is crucial for maximizing benefits and strengthening the economy. 3. localizing gas procurement can lead to substantial economic prosperity and reduce import dependency. Investments in offshore exploration are key to enhancing economic power and revenue generation. |

| SHIPBUILDING | 1. The shipping and shipbuilding industries lack adequate political and state support. 2. There is a need for principles, inspections, and targeted support beyond fishing vessels. 3. Positive political approaches can significantly enhance the service quality of shipbuilding. Careful attention is required during the construction phase to ensure high quality and efficiency. |

1. The shipbuilding industry must adopt environmentally friendly practices to minimize environmental and noise pollution. 2. Sustainable methods and materials should be prioritized to reduce marine pollution. 3. Embracing green management practices in shipbuilding is crucial for environmental conservation. Despite its economic benefits, including job creation and contribution to the national economy, the industry must address its environmental impact. 4. Legal regulations for the use of non-harmful paints and materials are essential. |

1. This sector enhances social status and adds value to life. 2. It offers job opportunities. There is a need for more qualified and trained staff. |

1. The shipbuilding industry must adopt the latest and most advanced technologies to improve efficiency and meet global standards. 2. Establishing better-equipped shipyards in the Black Sea is essential for sector growth. 3. Workforce training is crucial for supporting technological advances in shipbuilding. 4. The industry must lead technological developments and contribute significantly to the national economy. Innovations, including the use of electric motors and generators, are key to reducing fossil fuel dependency and offering economical solutions. |

1. Laws governing open sea vessels should also apply to the Black Sea. 2. Enhancing legal regulations could significantly boost the shipbuilding industry’s success. Strengthening legal standards enforcement is essential. |

— |

| MARINE AQUACULTURE | 1. Political support in the sector has led to significant economic growth, resulting in environmental damage as well. 2. Despite being a growing industry, marine aquaculture lacks the necessary political backing and recognition. |

1. Marine aquaculture sites should be selected scientifically to avoid pollution. 2. The industry faces environmental challenges, notably from practices such as cage farming. 3. Fish farming should diversify protein sources to reduce reliance on feeding fish to fish. 4. There is a significant environmental impact, including pollution, from current practices. 5. Facility locations and feeding practices must be environmentally considerate, ensuring that non-toxic materials are used. Education concerning environmental practices and the implementation of strict regulations are required for businesses and workers in the sector. |

1. Aquaculture offers both social benefits and employment. 2. Awareness needs to be boosted to combat the “sea takes it away” mindset. 3. The environmental impact of aquaculture should be clearly communicated to the public. The society has become accustomed to aquaculture products. |

1. New technologies for offspring and larval rearing can decrease early-stage losses in aquaculture. 2. Public awareness of the consumption of processed aquaculture products requires improvement. The relationship between aquaculture practices and environmental impact should be clearly regulated. |

1. Legal frameworks for aquaculture must be established. 2. Export regulations for bivalves require timely completion to meet legal standards. 3. New regulations are needed to address overfishing and ghost nets. 4. Laws applicable in the Aegean and Mediterranean regions should be reviewed and adapted for the newly developing sector in the Black Sea. The use of fish below the legal size in aquaculture feed production must be prohibited. |

1. Aquaculture’s economic benefits are significant, often outweighing environmental concerns. 2. Aquaculture should diversify beyond fish to include other marine and freshwater species. 3. Exports from aquaculture in the Black Sea are poised to surpass those of hazelnuts. 4. The growing aquaculture production trend is crucial to the national economy. 5. Economic pressures sometimes lead to non-compliance with procedures. 6. Aquaculture sectors significantly boost a country’s economy, especially through exports. Enhancing the value of sea products through processing can further contribute to economic growth. |

| OCEAN RENEWABLE ENERGY | 1. The sector requires immediate preparation and enhancement of its political infrastructure. 2. Decision makers need to allocate more attention and political support to meet the growing energy demand. 3. Investments in this sector, including renewable energy production, should receive government incentives and legal backing. 4. While support is crucial for a country’s economic and energy needs, over-spending, which leads to rapid growth, poses risks. Principled policies and efficient collaboration with political infrastructure are necessary for sustainable development. |

1. Renewable energy from waves and currents should be promoted for environmental benefits. 2. The importance of cautious implementation to prevent potential environmental harm is emphasized. 3. Location selection for renewable energy projects must be strategic and not arbitrary. 4. Adopting environmentally friendly alternative energy sources is crucial. 5. A meticulous examination of environmental ramifications alongside the formulation of pertinent policies is indispensable for securing long-term sustainability. It is imperative that the technologies employed prioritize environmental integrity to effectively address and assuage ecological concerns. |

1. Raising social and environmental awareness is crucial in the context of renewable energy. 2. The social impacts of renewable energy initiatives must be thoroughly investigated. 3. Public awareness campaigns are essential to highlight the benefits and necessity of renewable energy. 4. Using mass educational programs to disseminate knowledge on energy sustainability. 5. Clear communication with the public on the importance of renewable energy is vital. Efforts must be made to correct societal misconceptions related to renewable energy sources. |

1. Enhance efficiency by integrating developing technology into renewable energy projects. 2. Building robust future technological infrastructure with a focus on renewable equipment. 3. Support environmentally friendly technologies and develop methods to harness marine resources for energy production. 4. Special emphasis on evaluating and investing in floating ship energy turbines because of the current lack of investment. 5. Training experts within the sector and promoting high-level technological use and innovation. 6. Encourage public awareness and investment in technology, along with equipment improvements for optimal site identification. Leveraging the region’s suitability for renewable technology through targeted attempts and initiatives. |

1. New legal regulations are needed for the emerging sector. 2. Infrastructure improvements could lead to more efficient outcomes. Existing legislation should be thoroughly reviewed because of the current lack of specific legislation. |

1. State support is crucial for economic development within the sector. 2. Economic contributions from industry significantly benefit the country’s economy. 3. The potential for economic growth and resource contribution through the sector should be further explored and expanded. 4. Increasing economic support is essential for enhancing the sector’s impact on national development. The energy-harvesting economy of harnessing currents and waves presents favorable conditions but incurs high costs. |

| MARINE TRANSPORT | 1. An essential need for political support in maritime transport. 2. The geopolitical significance of the Black Sea complicates policymaking and international cooperation. 3. Maritime transport should be promoted as a viable alternative to road and rail transport. 4. The preparation and development of political infrastructure are crucial for the sector’s success. 5. Maritime transport faces potential political obstacles because of its role as an alternative to land transport. 6. A principled policy approach and infrastructure creation are necessary for effective maritime transport. Political agreements between countries on maritime transport exist, but issues in their implementation need to be resolved. |

1. Preparation of environmental infrastructure is crucial for maritime transport. 2. Adoption of environmentally compatible technologies to minimize pollution. 3. Enhance environmental awareness and supervision to promote sustainability. 4. Implementing green management practices for a more environmentally friendly industry. 5. The importance of sanctions and regulations, especially concerning ballast water discharge, to mitigate environmental impact. Maritime transport serves as a viable alternative to terrestrial transport, emphasizing the need for eco-friendly practices. |

1. Increased social research is needed in maritime transport. 2. Ports play a crucial role in providing livelihoods and enhancing mobility. 3. The social impacts of maritime technologies must be thoroughly investigated. 4. The sector’s positive contributions to social life, employment, and welfare are significant. Maritime transportation has gained importance with a growing population, necessitating further emphasis. |

1. Emerging communication and information technologies enhance sector efficiency. 2. Transportation technology standards should dictate classification into different classes and levels. 3. Monitoring and keeping abreast of new maritime technologies are crucial. 4. Construction of modern boats tailored for sea transportation is essential. Technological support is vital for maintaining competitiveness and innovation. |

1. Penalties and sanctions should be a sufficient deterrent to ensure compliance. 2. The legal framework in Türkiye supports its strong position in the Black Sea, with no major legal issues. 3. New laws and regulations are necessary for industry growth. Adherence to both national and international laws is crucial for the maritime sector. |

1. Maritime transport is a key driver of economic prosperity. 2. Economic support and investment in maritime transport and port development are crucial. 3. High economic returns are associated with maritime transport, significantly affecting both world and national economies. 4. Enhanced maritime tourism, including cruise tourism, can enhance economic growth. 5. The environmental impact of marine tourism should be carefully examined. Increasing maritime transport is expected to benefit the region economically. |

| HIGH-TECH MARINE SERVICES | 1. The sector requires support without political bias. 2. Sustainable technologies should be supported in the marine sector. 3. The development of policies and regulations for advanced marine technologies is essential. 4. Political support is needed to advance the sector. 5. The issue should be prioritized by decision makers, noting the limited progress made thus far. |

1. Technology should prioritize environmental friendliness. 2. It should contribute to environmental protection efforts. 3. The adoption of this technology can help reduce marine pollution. |

— | 1. Use technology’s benefits in the marine sector. 2. Support technological research and development in this area. 3. Technology can shape the future of marine exploration. Focus on developing devices and technologies for data transmission at challenging depths. |

1. Legal arrangements for the sector should be prioritized. 2. Preparing a legal infrastructure is crucial. Regulations for advanced marine technology studies must be established. |

1. Economical transportation solutions are achievable. 2. Emerging technologies can positively impact the national economy. 3. Increased budget allocation is essential for sector development. Investment in this sector is necessary for its advancement. |

Multi-sectoral stakeholder perspectives on the political, environmental, social, technical, legal, and economic challenges in the Blue Economy of the Black Sea.

3.2 Environmental

The environmental dimension of the Blue Economy sector underscores the pressing need for sustainable practices and stringent regulations across various industries to mitigate environmental degradation (Table 1). In capture fisheries, challenges such as limited awareness, pollution, and climate change lead to unsustainable practices, ecosystem damage, reduced fish stocks, and disrupted marine life cycles, emphasizing the need for stricter regulations and sustainable fishing practices. Marine research and development are essential for addressing marine pollution and fostering ecosystem health, which is defined as the ability of ecosystems to maintain their structure, function, and resilience under stress by advancing innovative technologies, conducting comprehensive studies, and implementing restoration efforts to mitigate pollution, preserve biodiversity, and sustain ecological processes. The offshore oil and gas industry must carefully evaluate environmental impacts and adopt innovative strategies to mitigate pollution risks. The shipbuilding industry is urged to adopt environmentally friendly practices and materials to minimize its ecological footprint. Marine aquaculture requires scientific site selection and the use of diversified protein sources in commercial fish feed, such as plant-based proteins, insect meals, and sustainably harvested marine ingredients, to reduce environmental impacts, highlighting the importance of education and stringent regulations. Ocean renewable energy advocates for cautious implementation of projects to harness environmental benefits without causing harm, prioritizing environmentally friendly technologies. Marine transport and high-tech marine services emphasize the urgent need to adopt green management practices, such as energy-efficient technologies and waste reduction strategies, while fostering greater environmental awareness among stakeholders. These efforts must be supported by robust regulatory frameworks to ensure sustainable operations and minimize pollution. This highlights the shared recognition across sectors of the Blue Economy that achieving environmental responsibility is essential for long-term economic and ecological sustainability.

3.3 Social

The social aspects of the Blue Economy sector highlight the significant impact of various industries on employment, social welfare, and community engagement (Table 1). In the capture fisheries sector, job opportunities contribute to regional development but must be balanced with the challenge of overfishing, especially in the Black Sea, while addressing tensions between artisanal and industrial fisheries. Marine R&D faces public apathy, yet their social benefits and potential for community engagement remain underappreciated, pointing to the need for better communication of their value. The offshore oil and gas industry is expected to transform social life positively through economic contributions, necessitating increased public awareness of the benefits of offshore activities. The shipbuilding sector contributes to social status, offers job opportunities, and requires more qualified staff. Marine aquaculture provides social benefits and employment, though there’s a need to enhance public awareness about its environmental impacts and products. Ocean renewable energy highlights the need to increase social and environmental awareness, conduct thorough assessments of its social impacts, and educate the public on the benefits and importance of transitioning to renewable energy sources. Marine transport highlights the need for increased research on its social impacts, the crucial role of ports in supporting livelihoods and mobility and the significant contributions of the sector to social life and welfare. Across these sectors, the emphasis on education, awareness, and communication underscores the need to address societal misunderstandings and promote sustainable practices for the betterment of community welfare and environmental stewardship.

3.4 Technical

The technical challenges and innovations in the Blue Economy sector emphasize the critical balance between advancing technology and ensuring sustainability (Table 1). In capture fisheries, especially in the unique ecosystem of the Black Sea, there is an urgent need to phase out harmful fishing technologies, such as bottom trawling and overfishing practices, in favor of advanced, sustainable methods like selective fishing gear and real-time monitoring systems. These technologies are designed to reduce bycatch, protect habitats, and ensure the long-term health of fish stocks. The unmonitored use of advanced fishing technologies has led to overfishing, highlighting the need for stricter regulations and the careful introduction of digital innovations to maintain fish populations. Marine research and development in Türkiye are hindered by a technological gap and insufficient investment, requiring urgent support and access to advanced tools for effective ecosystem monitoring and marine studies. The offshore oil and gas sector sees new technologies as pivotal for enhancing exploration efficiency, with sustainability as a crucial goal. In shipbuilding, adoption of the latest technologies, workforce training, and innovations such as electric motors are essential for sector growth and reducing fossil fuel dependency. Marine aquaculture benefits from technologies that reduce early-stage losses in fish and shellfish production, whereas ocean renewable energy projects require the integration of developing technologies and public investment to efficiently harness marine resources. Emerging technologies in marine transport, such as automated vessels, fuel-efficient propulsion systems, and digital navigation tools, improve efficiency and competitiveness, requiring ongoing monitoring and innovation. High-tech marine services focus on leveraging technologies like remote sensing, subsea robotics, and real-time data transmission systems for marine exploration and deep-sea data collection, underscoring the sector-wide need for technological advancement while maintaining environmental and ecological integrity.

3.5 Legal

The legal challenges and necessities within the Blue Economy sector highlight the comprehensive need for the establishment, re-evaluation, and rigorous enforcement of laws and regulations across various domains to ensure sustainability and compliance (Table 1). In capture fisheries, the call for laws and quotas based on thorough research, stronger control mechanisms, and resolution of issues stemming from inadequate enforcement and the influence of politics over science is evident. This highlights the need for economic sustainability through legal adherence and consistent implementation of comprehensive legal frameworks. Marine R&D suffers from outdated legal frameworks that necessitate updates and strict auditing to keep pace with technological advances. Offshore oil and gas exploration requires legal readiness at both national and international levels, and the shipbuilding industry could significantly benefit from enhanced legal regulations and the application of open sea vessel laws to the Black Sea. Legal frameworks tailored specifically for the aquaculture sector are needed, along with regulations addressing overfishing, ghost nets, and the use of undersized fish in feed production. The emerging ocean renewable energy sector requires new legal regulations and a review of existing legislation to meet its specific needs. Marine transport highlights the importance of enforcing deterrent penalties and sanctions, adhering to national and international laws and introducing new regulations to support sector growth. High-tech marine services also face a critical need for prioritized legal arrangements and the preparation of legal infrastructure to support technological advancements, underscoring the sector-wide imperative for legal innovation and enforcement to foster responsible and sustainable growth in the Blue Economy.

3.6 Economics

The economic aspects of the Blue Economy sector underscore the critical importance of sustainable practices, financial investments, and strategic development across various industries to foster economic growth and national development (Table 1). In capture fisheries, the transition to electrical energy, through the adoption of electric-powered vessels and equipment to replace or supplement fossil fuels, along with the development of region-specific vessel standards and the need for enhanced economic strategies, are highlighted due to the sector’s significant contribution to the national economy and local communities. Marine R&D faces economic challenges due to funding and resource shortages, emphasizing the necessity for increased investment and strategic research with cost-benefit analyses. Offshore oil and gas exploration has emerged as a vital component of economic prosperity with the potential to reduce import dependency and contribute significantly to national revenues. Aquaculture is recognized for its substantial economic benefits and potential to surpass traditional exports although economic pressures sometimes lead to procedural non-compliance. The sector’s growth is crucial for the national economy, especially through the diversification and value enhancement of sea products. Ocean renewable energy requires state support and increased economic support to exploit its potential for economic growth, despite the high costs associated with energy generation from currents and waves. Maritime transport, a key driver of economic prosperity, benefits from investments in transport and port development, with maritime tourism offering additional economic growth opportunities. High-tech marine services highlight the potential for economical transportation solutions and the positive impact of emerging technologies on the national economy, necessitating increased budget allocation and investment for sector advancement. Collectively, these sectors reveal the intricate interplay between economic development, sustainability, and the need for targeted investment and policies to ensure the Blue Economy’s long-term viability and contribution to economic prosperity.

4 Discussions

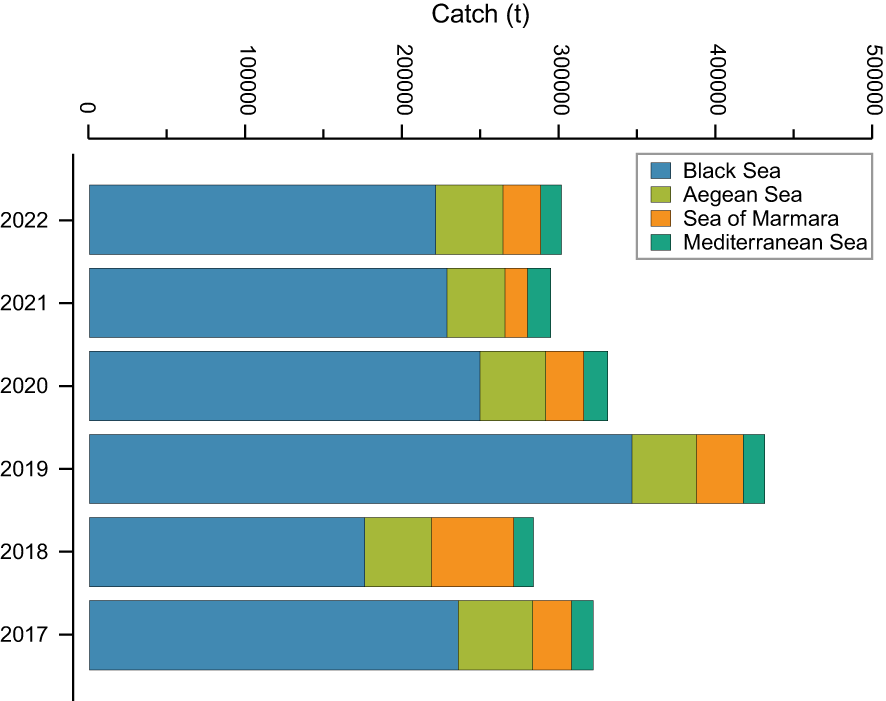

This study is the first comprehensive multi-sectoral stakeholder forum in the Turkish Black Sea region, prioritizing capture fisheries within the Blue Economy framework (Figure 4B). The forum explored barriers to development and highlighted gaps in cross-sectoral collaboration and understanding, reflecting challenges identified in other studies (Elegbede et al., 2023). The prioritization of capture fisheries underscores their vital role in Türkiye’s Blue Economy, with the Black Sea contributing 73% of the nation’s total catch fisheries production TÜİK (2023). Of this, 71% comprises marine fish, and 29% consists of other marine products (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Wild-caught fishing volume in Turkish seas (tons) (TÜİK, 2023).

4.1 Fisheries and aquaculture: a key sector

The capture fisheries sector faces multifaceted challenges, including overfishing, environmental changes (e.g., temperature fluctuations and pollution), and regulatory measures aimed at sustainability and fish stock protection. These issues align with EMODnet Black Sea Checkpoints challenges, which emphasize sustainable fisheries management, the impacts of eutrophication, riverine inputs, and climate change on fisheries’ resilience and productivity (Calewaert et al., 2016; Martín Míguez et al., 2019; Palasov et al., 2019; EMODnet, 2024). The decline in catches from 2019 to 2022 (Figure 5) highlights the urgent need for integrated management approaches to balance economic and ecological priorities.

Small-scale fisheries in the Black Sea directly support approximately 26,800 individuals, including 6,700 crew members operating 3,372 active boats, making significant contributions to livelihoods along Türkiye’s coast (Dağtekin et al., 2021; Khan and Seyhan, 2022). Similarly, aquaculture, ranked sixth in this study, plays a complementary role in food production and employment, contributing 314,408 tons of annual production during 2020–2021 and employing 2,828 people (FAO, 2023). Despite its potential, the fisheries sector faces political, environmental, social, technical, legal, and economic challenges, necessitating strengthened collaboration, coherent governance structures, and policies aligned with scientific research (Crona et al., 2019; Salinas-Zavala et al., 2022; Elegbede et al., 2023).

4.2 Marine pollution and emergency management

Marine pollution, particularly oil spills, has emerged as a critical concern (Zhang et al., 2019; Baghdady and Abdelsalam, 2024; Eryigit and Gungor, 2025). Heavy marine traffic and existing gas pipelines increase the risk of oil spills, posing significant threats to ecosystems and the Blue Economy (Akkaya Bas et al., 2017; Eryigit and Gungor, 2025). Robust emergency management frameworks, enhanced monitoring systems, and regional cooperation are essential to mitigate risks and address pollution effectively (Palasov et al., 2019; EMODnet, 2024). Past incidents underscore the need for proactive strategies to safeguard the Black Sea’s marine environment and economic potential (Öztürk et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2019).

4.3 Shipbuilding and its environmental impacts

Türkiye’s shipbuilding sector, with ~ 90 shipyards – 51 of them along the Black Sea coast – plays a significant role in the Blue Economy (KPMG, 2022). Commercial ships accounted for 62.7% of total production in 2021, while non-commercial vessels constituted 37.3% (KPMG, 2022). This sector generates substantial revenue, with new ship construction contributing $1.5 billion USD annually and ship repair and maintenance adding $1 billion USD General Directorate of Exports (2016). Turkish-built ships are exported to markets like Norway, Malta, Iceland, and Canada, reinforcing the sector’s global significance. In addition to its economic contributions, as endorsed by this study, various significant environmental risks associated with shipbuilding activities are also identified. Conventional methods such as welding, painting, blasting, and fiberglass work release harmful gases, discharge toxic chemicals into wastewater, generate hazardous waste, and contribute to noise pollution (Papaioannou, 2003; Rahman and Karim, 2015; Dragičević et al., 2022). Addressing these risks requires adopting sustainable practices, transitioning to environmentally friendly materials, and implementing green management systems. Modernizing shipyards and incorporating advanced technologies are critical for enhancing competitiveness and minimizing ecological impacts in this sector.

4.4 Gaps in marine research and development

The forum identified critical gaps in marine research and development, including limited political support, insufficient public engagement, restricted access to technology and inadequate funding. These gaps highlight a disconnect between the essential requirements of marine research and the support it receives. Bridging these gaps through increased collaboration, funding, and public awareness is vital for advancing sustainable management of marine ecosystems (Van Hoof et al., 2019; Wisz et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2022; Pace et al., 2023). This study also demonstrated that offshore oil and gas exploration requires integrated efforts to adopt sustainable practices, manage environmental impacts, and attract strategic investments. Enhanced R&D can support these goals by developing innovative solutions and addressing gaps in public education and advanced technologies.

5 Conclusions

The Blue Economy of the Black Sea faces complex challenges, including sustainable fisheries management, marine pollution, and biodiversity preservation. Addressing these requires integrating scientific research with policymaking, strengthening governance frameworks, and investing in sustainable technologies and practices. Overcoming outdated infrastructure and economic barriers, such as insufficient funding, is equally vital.

A comprehensive, long-term strategy prioritizing sustainability, collaboration, and innovation is essential. Shifting from short-term political goals to inclusive approaches based on strong environmental regulations, public education, and regional cooperation will unlock the region’s economic potential while protecting its biodiversity. Collective action is crucial to ensuring the resilience and sustainable future of the Black Sea.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ÖD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. EA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ŞA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. KÖ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HA: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. EK: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. RM: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. PK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the European Union Research (EU HORIZON, 2020) Project called “DOORS, no:101000518” (Developing Optimal and Research Support for the Black Sea).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Açıkmeşe S. A. (2012). The EU’s black sea policies: any hopes for success? Euxeinos Online J. Center Govern. Culture Europe6, 17–23.

2

Afanasyev A. Chantzi G. Hajiyev S. Kalognomos S. Sdoukopoulos L. (2020). Black Sea Synergy: The way forward. Available online at: https://icbss.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/1977_original.pdf (Accessed January 5, 2025).

3

Aivaz K.-A. Stan M.-I. Vintilă D.-F. (2021). Why should fisheries and agriculture be considered priority domains for maritime spatial planning in the black sea? A stakeholder perspective. Ovidius Univ. Annals Econ. Sci. Ser.21, 12–20.

4

Akkaya Bas A. Christiansen F. Amaha Öztürk A. Öztürk B. Mcintosh C. (2017). The effects of marine traffic on the behaviour of Black Sea harbour porpoises (Phocoena relicta) within the Istanbul Strait, Turkey. PloS One12, e0172970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172970

5

Alkan N. Terzi Y. Khan U. Bascinar N. Seyhan K. (2019). Evaluation of seasonal variations in surface water quality of the Caglayan, Firtina and Ikizdere rivers from Rize, Turkey. Fresenius Environ. Bull.28, 9679–9688.

6

Achimescu C. Chiricioiu V. Oltean I. (2021). “Challenges to black sea governance. regional disputes, global consequences? Romanian Journal of International Law. 26, 35–61.

7

Aydin M. (2005). Europe’s new region: The Black Sea in the wider Europe neighbourhood. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud.5, 257–283. doi: 10.1080/14683850500122943

8

Baghdady S. M. Abdelsalam A. A. (2024). Ten years of oil pollution detection in the Eastern Mediterranean shipping lanes opposite the Egyptian coast using remote sensing techniques. Sci. Rep.14, 18057. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-67983-x

9

Bakan G. Büyükgüngör H. (2000). The black sea. Mar. pollut. Bull.41, 24–43. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(00)00100-4

10

Bennett N. J. Blythe J. White C. S. Campero C. (2021). Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Mar. Policy125, 104387. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387

11

Calewaert J.-B. Weaver P. Gunn V. Gorringe P. Novellino A. (2016). “The European Marine Data and Observation Network (EMODnet): Your Gateway to European Marine and Coastal Data,” in Quantitative Monitoring of the Underwater Environment: Results of the International Marine Science and Technology Event MOQESM´14 in Brest, France. Eds. ZerrB.JaulinL.CreuzeV.DebeseN.QuiduI.ClementB.Billon-CoatA. (Springer International Publishing, Cham), 31–46.

12

Candan A. Karataş S. Küçüktaş H. Okumuş İ. (2007). Marine aquaculture in Turkey (İstanbul, Turkey: Turkish Research Foundation).

13

Chen J. Zhang W. Wan Z. Li S. Huang T. Fei Y. (2019). Oil spills from global tankers: Status review and future governance. J. Cleaner Product.227, 20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.020

14

Council of the European Union (2024). Joint staff working document: Black Sea Synergy: 4th review of a regional cooperation initiative – period 2019–2023. Available online at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-11900-2024-INIT/en/pdf (Accessed January 5, 2025).

15

Crona B. Käll S. Van Holt T. (2019). Fishery Improvement Projects as a governance tool for fisheries sustainability: A global comparative analysis. PloS One14, e0223054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223054

16

Dağtekin M. Misir D. S. Şen İ. Altuntaş C. Misir G. B. Çankaya A. (2021). Small-scale fisheries in the southern Black Sea: Which factors affect net profit? Acta Ichthyol. Piscatoria51, 145–152. doi: 10.3897/aiep.51.62792

17

DOKA (2023).Blue economy of Turkey – 4BIZ country report: Current situation in the field of fisheries and aquaculture, coastal and maritime tourism, and maritime transport. Available online at: https://maritimeUkraine.com/en/25-03-2023/ (Accessed January 5, 2025).

18

Dragičević V. Levak M. Turk A. Lorencin I. (2022). Ship production processes air emissions analysis. Pomorstvo36, 164–171. doi: 10.31217/p.36.1.19

19

Dürrani Ö. Bal H. Battal Z. S. Seyhan K. (2022). Using otolith and body shape to discriminate between stocks of european anchovy (Engraulidae: Engraulis encrasicolus) from the aegean, marmara and black seas. J. Fish Biol.101, 1452–1465. doi: 10.1111/jfb.15216

20

Dürrani Ö. Seyhan K. (2024). Stock identification of the mediterranean horse mackerel (Carangidae: Trachurus mediterraneus) in the marmara and black seas using body and otolith shape analyses. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.299, 108687. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2024.108687

21

Elegbede I. O. Fakoya K. A. Adewolu M. A. JoLaosho T. L. Adebayo J. A. Oshodi E. et al . (2023). Understanding the social–ecological systems of non-state seafood sustainability scheme in the blue economy. Environ. Dev. Sustainabil. doi: 10.1007/s10668-023-04004-3

22

EMODnet (2024). European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet). Available online at: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en/black-sea-1 (Accessed January 5, 2025).

23

Eryigit E. N. Gungor Y. (2025). Oil spill kills dozens of dolphins on Russian Black Sea coast: Animal rescue group (Anadolu Agency). Available at: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/energy/oil/oil-spill-kills-dozens-of-dolphins-on-Russian-black-sea-coast-animal-rescue-group/46666.

24

EU HORIZON . (2020). Available online at: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101000518/results

25

FAO (2023). The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2023 – Special edition (Rome: General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean). doi: 10.4060/cc8888en

26

General Directorate of Exports (2016). Republic of Turkey - Ministry of Economy. Available online at: https://www.spcr.cz/images/kdvorakova/shipbuilding_industry_report.pdf.

27

Hidalgo M. Mihneva V. Vasconcellos M. Bernal M. (2018). Climate change impacts, vulnerabilities and adaptations: Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea marine fisheries. In BarangeM.BahriT.BeveridgeM.C.M.CochraneK.L.Funge-SmithS.PoulainF., eds. Impacts of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture: synthesis of current knowledge, adaptation and mitigation options. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 627. Rome, FAO.

28

Hoerterer C. Schupp M. F. Benkens A. Nickiewicz D. Krause G. Buck B. H. (2020). Stakeholder perspectives on opportunities and challenges in achieving sustainable growth of the blue economy in a changing climate. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00795

29

Karamushka V. (2009). Socio-economic aspects of the Black Sea region (Commission on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution). Available at: http://www.blacksea-commission.org/_socio-economy.asp.

30

Khan U. Seyhan K. (2022). “Anchovies of the world,” in Anchovies: Ecological, economic and social evaluation. Ed. SeyhanK. (Türkiye: RİBİAD: Rize’li Bürokratlar, Yöneticiler ve İş İnsanları Derneği), 9–31.

31

Kelly R. Foley P. Stephenson R. L. Hobday A. J. Pecl G. T. Boschetti F. et al . (2022). Foresighting future oceans: Considerations and opportunities. Mar. Policy140, 105021. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105021

32

KPMG (2022). Gemi Inşa Sektörel Bakış 2022. Available online at: https://kpmg.com/tr/tr/home/gorusler/2023/04/gemi-insa-sektorel-bakis-2022.html (Accessed 01/04/2024).

33

Martínez-Vázquez R. M. Milán-García J. De Pablo Valenciano J. (2021). Challenges of the Blue Economy: evidence and research trends. Environ. Sci. Europe33, 61. doi: 10.1186/s12302-021-00502-1

34

Martín Míguez B. Novellino A. Vinci M. Claus S. Calewaert J.-B. Vallius H. et al . (2019). The European marine observation and data network (EMODnet): visions and roles of the gateway to marine data in Europe. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00313

35

Massa F. Aydın I. Fezzardi D. Akbulut B. Atanasoff A. Beken A. T. et al . (2021). Black Sea aquaculture: Legacy, challenges & future opportunities. Aquacult. Stud.21. doi: 10.4194/2618-6381-v21_4_05

36

Melikidze V. Chkhaidze V. Kobaidze S. (2019). Adoption of the Coastal Zone of the Black Sea in Georgia Based on the Principles of Blue Economy (Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University).

37

Murray J. W. Jannasch H. W. Honjo S. Anderson R. F. Reeburgh W. S. Top Z. et al . (1989). Unexpected changes in the oxic/anoxic interface in the Black Sea. Nature338, 411–413. doi: 10.1038/338411a0

38

Oguz T. Akoglu E. Salihoglu B. (2012). Current state of overfishing and its regional differences in the Black Sea. Ocean Coast. Manage.58, 47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.12.013

39

Oral N. (2013). “Chapter II State of the Black Sea: The Making and Unmaking of a Sea,” in Regional Co-operation and Protection of the Marine Environment Under International Law, vol. 45-73. (Brill Nijhoff).

40

Öztürk M. Özdemir F. Yücel E. (1997). An overview of the environmental issues in the Black Sea region. Scientif. Environ. Polit. Issues Circum-Caspian Region213-226.

41

Pace L. A. Saritas O. Deidun A. (2023). Exploring future research and innovation directions for a sustainable blue economy. Mar. Policy148, 105433. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105433

42

Palasov A. Slabakova V. Blanc F. Kallos G. Raykov V. Lardner R. et al . (2019). “EMODnet black sea checkpoint products,” in EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, 3621.

43

Papaioannou D. (2003). Environmental implications, related to the shipbuilding and ship repairing activity in Greece. Pomorski zbornik41, 241–252.

44

Radulescu V. (2023). Environmental conditions and the fish stocks situation in the black sea, between climate change, war, and pollution. Water15, 1012. doi: 10.3390/w15061012

45

Rahman A. Karim M. M. (2015). Green shipbuilding and recycling: Issues and challenges. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev.6, 838. doi: 10.7763/IJESD.2015.V6.709

46

Rudneva I. Petzold-Bradley E. (2001). “Environment and Security Challenges in the Black Sea Region,” in Responding to Environmental Conflicts: Implications for Theory and Practice. Eds. Petzold-BradleyE.CariusA.VinczeA. (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht), 189–207.

47

Salinas-Zavala C. A. Morales-Zárate M. V. Cisneros-Montemayor A. M. Bojórquez-Tapia L. A. (2022). Editorial: the approach to complex systems in fisheries. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.830225

48

Sezgin M. Levent B. Ürkmez D. Arici E. Öztürk B. (2017). Turkish Mar. Res. Found. (TUDAV) Publ. No: 46 Isntabul Turkiye.

49

Schultz-Zehden A. Lukic I. Ansong J. O. Altvater S. Bamlett R. Barbanti A. et al . (2018). Ocean Multi-Use Action Plan, MUSES project. Edinburgh, pp. 5–121. Available online at: https://medblueconomyplatform.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/file-library-062043c4815f5725986d.pdf (Accessed January 05 2025).

50

Seyhan K. Dürrani Ö. Sahin A. Terzi Y. (2022). Catch composition of non-target species escaping dredge gear of rapana fisheries in the western coast of the black sea. Mar. Biol. Res.18, 347–360. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2022.2126857

51

TÜİK (2023). Su Ürünleri Istatistikleri (Fisheries Statistics). Available online at: https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=97&locale=tr (Accessed 31.03.2024).

52

Van Hoof L. Fabi G. Johansen V. Steenbergen J. Irigoien X. Smith S. et al . (2019). Food from the ocean; towards a research agenda for sustainable use of our oceans’ natural resources. Mar. Policy105, 44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.02.046

53

Vasilica F.-A. Panaitescu M. Panaitescu F.-V. Scupi A.-A. Panaitescu V.-N. (2023). Assessing the vulnerability of marine ecosystems in the context of climate change (SPIE).

54

Wisz M. S. Satterthwaite E. V. Fudge M. Fischer M. Polejack A. St. John M. et al . (2020). 100 opportunities for more inclusive ocean research: cross-disciplinary research questions for sustainable ocean governance and management. Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00576

55

Yazgan H. (2017). Black sea synergy: success or failure for the European Union? Marmara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilimler Dergisi5, 83–94. doi: 10.14782/sbd.2017.57

56

Zhang B. Matchinski E. J. Chen B. Ye X. Jing L. Lee K. (2019). “Chapter 21 - Marine Oil Spills—Oil Pollution, Sources and Effects,” in World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation, 2nd ed. Ed. SheppardC. (Academic Press), 391–406.

Summary

Keywords

aquaculture, blue economy development, fisheries, marine coastal tourism, maritime transport, ocean policy, offshore renewable energy, shipbuilding

Citation

Seyhan K, Dürrani Ö, Papadaki L, Akinsete E, Atasaral Ş, Özşeker K, Akpınar H, Kurtuluş E, Mazlum RE, Koundouri P and Stanica A (2025) Bridging the gaps for a thriving Black Sea Blue Economy: insights from a multi-sectoral forum of Turkish stakeholders. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1491983. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1491983

Received

05 September 2024

Accepted

13 January 2025

Published

05 February 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Stefania Angela Ciliberti, Nologin Oceanic Weather Systems, Spain

Reviewed by

Svitlana Liubartseva, Fondazione CMCC Centro Euro-Mediterraneo sui Cambiamenti Climatici, Italy

George Zodiatis, University of Cyprus, Cyprus

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Seyhan, Dürrani, Papadaki, Akinsete, Atasaral, Özşeker, Akpınar, Kurtuluş, Mazlum, Koundouri and Stanica.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kadir Seyhan, seyhan@ktu.edu.tr; Adrian Stanica, astanica@geoecomar.ro

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.