Abstract

Nearshore fringing reefs have been shown to establish and accrete within sediment-laden coastal environments over millennial timescales. However, the mechanisms governing the evolution of turbid-water reefs remain inadequately understood. This study focuses on a fringing reef in the Changpi (CP) region along the eastern coast of Hainan Island, China. Sedimentological and geochronological analyses of four drill cores provided the first comprehensive growth history for this marginal reef setting through a systematic reconstruction of its developmental chronology, architectural framework, and ecological characteristics. Radiocarbon dating reveals reef initiated at about 7,400 cal yr BP and ceased accretion after 4,000 cal yr BP. By integrating core observations, thin-section petrography, and X-ray diffraction results, five distinct lithofacies were identified. These lithofacies exhibit varying degrees of mixing between siliciclastic and carbonate components, revealing that the reef system was periodically influenced by terrigenous siliciclastic input. The vertical accretion of the CP reef underwent three primary stages: (1) colonization stage (7,400-6,400 cal yr BP), characterized by well-preserved coral assemblages in high-energy, clear-water conditions with relatively low accretion rates (ca 0.35 mm/yr) and gradual coral diversification; (2) turbid stage (6,400-5,500 cal yr BP), marked by rapid terrigenous clastic deposition that produced persistent turbidity, leading to accelerated accretion rates (up to 6.29 mm/yr) and reduced coral diversity; and (3) stabilization stage (5,500-4,000 cal yr BP), during which stabilized siliciclastic input restored clear-water conditions, supporting renewed coral growth at moderate accretion rates (ca 2.70 mm/yr). This case study demonstrates that terrestrial sediment fluxes can exert a greater influence on nearshore reef trajectories than sea-level changes, particularly in regions or periods characterized by high sediment input. As suggested by the findings, this underscores the necessity of integrated coastal zone management strategies aimed at reducing agricultural runoff and controlling construction sediment to enhance reef resilience.

1 Introduction

As globally significant repositories of marine biodiversity, coral reef ecosystems deliver critical ecological services through their unparalleled productivity and complex habitat structures, sustaining coastal communities across tropical latitudes (Knowlton and Jackson, 2008; Barnes et al., 2019; Woodhead et al., 2019). Excessive terrigenous sedimentation is widely regarded as one of the concerning factors detrimental to coral reef health (Browne, 2012; Ellis et al., 2019). The siliciclastic influx process conventionally degrades reefs through multiple pathways: (1) photosynthetic inhibition via light attenuation (Fabricius, 2005; Roder et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2019); (2) larval recruitment suppression (Wittenberg and Hunte, 1992); (3) polyp smothering through corallite occlusion (Rogers, 1990; Weber et al., 2012), and (4) the prevalence of tissue infections (Voss and Richardson, 2006). Counterintuitively, emerging evidence demonstrates that certain reef systems exhibit remarkable adaptive capacity to chronic sediment stress (Sofonia and Anthony, 2008; Johnson et al., 2019; Rodgers et al., 2021; Gischler et al., 2023; Kappelmann et al., 2024).

The coral reef systems that grow in relatively turbid waters within nearshore zones (within 20 km of the coastline and not exceeding 20 m water depths) are defined as nearshore turbid zone reefs (Browne et al., 2012). These reefs are considered to have adapted to environments with high sediment yields and significant turbidity fluctuations caused by wave-driven resuspension of fine sediments (Browne et al., 2013; Morgan et al., 2016; Zweifler (Zvifler) et al., 2021), and they would exhibit greater resilience to increased sediment inputs than offshore reefs (Soares, 2020; Rodgers et al., 2021; Bonesso et al., 2023). Consequently, the identification of these turbid-zone coral reef ecosystems has fundamentally challenged conventional paradigms regarding coral environmental thresholds (Browne et al., 2013; Guest et al., 2016; Zweifler (Zvifler) et al., 2021). Central to ongoing scientific debate is the paradoxical accretion mechanisms operating under persistent terrigenous sedimentation. This scientific dichotomy stems from critical limitations in current observational frameworks. First, the majority of studies employ less than 200-year observational windows, insufficient to capture millennial-scale reef developmental cycles (Roche et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2016a; Chen et al., 2021a). Second, geographic bias persists with most published cases concentrating on the Great Barrier Reef (e.g. Perry et al., 2013; Ryan et al., 2018; Sanborn et al., 2020), Kimberley regions (Wilson et al., 2011; Solihuddin et al., 2015, 2016) in Australia, and the eastern Brazilian margin (Dechnik et al., 2019, 2021), leaving other areas relatively understudied. These constraints make it hard to understand how reef systems balance carbonate production with sediment input, maintain growth under changing turbidity, and develop long-term ecological resilience.

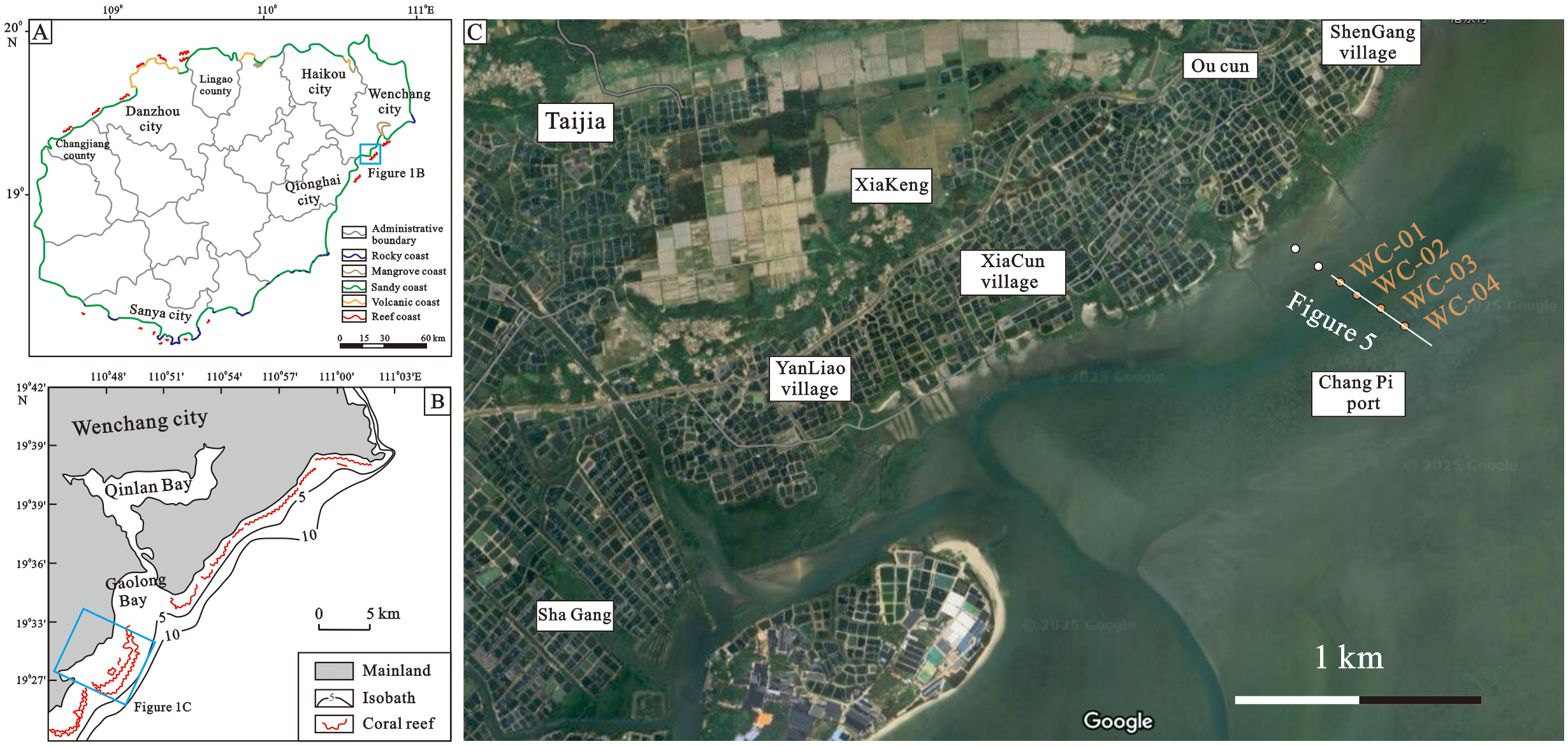

Coastal surveys have confirmed the widespread distribution of coral reef around the coast of Hainan Island, China (Quan et al., 1993; Wu et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2017) (Figure 1A). Geochronological constraints indicate reef initiation postdates 9,000 cal yr BP across the region (Zhang et al., 1990). In 2011, several seaward cores were conducted by the Hainan Academy of Ocean and Fisheries Sciences in the nearshore area of the Changpi (CP) region, located on the eastern coast of Hainan Island (Figures 1B, C), targeting its sedimentological architecture and growth history. The core observations reveal variable mixing of coral reef deposits with siliciclastic materials, evidencing sustained terrigenous influence throughout the reef’s developmental history (the result will be discussed in detail below). This geological record enables systematic examination of nearshore fringing reef evolution under prolonged terrigenous sedimentation. The study objectives are threefold: (1) to reconstruct a robust chronological framework using complete drill core data; (2) to characterize sedimentary features and vertical evolutionary patterns through integrated lithofacies, grain size, and biocompositional analyses; and (3) to identify the role of terrigenous siliciclastic inputs that govern the sedimentary evolution of the CP reef system. By focusing on millennial-scale reef development, this work elucidates distinct responses of nearshore reefs to terrestrial sedimentation, complementing traditional sea-level change paradigms and expanding on long-term data on turbid reefs in Asia. The findings advance mechanistic understanding of turbid reef systems and inform conservation strategies for sediment-impacted coastal reefs.

Figure 1

Geographic context of the study area and drill core locations. (A) Coastline distribution of Hainan Island and the location of the Changpi (CP) region. The CP region is a typical coral reef system located on the southwestern coastline of Wenchang City in northeastern Hainan Island (adapted from Wu et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2016). (B) The study site is located approximately 10 km south of the bay mouth of Gaolong Bay. Coral communities here occur along the 1-2 m isobaths, about 1-3 km from the shoreline, and are exposed during low tide. (C) Aerial photograph showing the studied ocean-facing transect. Four drilling cores, containing complete Holocene coral deposits and marked by orange circles, are the primary focus of the study. These cores are labeled WC-01, WC-02, WC-03, and WC-04, respectively.

2 Regional setting

Hainan Island is located in the northwestern South China Sea and is part of the continental shelf islands of the region, covering a total area of 33,920 km² and featuring a coastline about 1,528 km. Based on geomorphological and sedimentary characteristics, the coastline of Hainan Island can be classified into five principal types: sandy, volcanic, rocky, mangrove, and coral reef coasts (Gao et al., 2016, Figure 1A). Of these, although occupying a relatively limited spatial extent (< 10% of total coastline length), coral reef coasts represent the most distinctive geomorphological feature of the island (Yuan et al., 2006). These reefs are primarily found along the southeastern and western shores, including areas such as Sanya, Wenchang, Qionghai, Chengmai, and Danzhou region (Wu et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2017). The fringing reef, the primary reef type on Hainan Island, forms a broad reef flat that extends seaward and exhibit a sequence of distinct geomorphic features. These include massive coral zones, inner reef flats, and outer reef flats, each marked by unique carbonate deposits and reef communities (Zeng et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2011; Shao et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2019). Drilling data from previous studies show that the continuous thickness of reef deposits rarely exceeds 10 m and primarily dates back to the Holocene (Qiu, 1985; Zhang et al., 1990). The development of fringing reef is governed by multiple interacting factors. First, regional sea-level fluctuations exhibit close correspondence with reef depositional sequences, making these reefs reliable archives for reconstructing paleo-sea levels (Yao et al., 2013; Yue et al., 2024). Second, localized tectonic activity has induced differential subsidence rates across coastal sectors, creating spatial heterogeneity in reef accretion patterns (Qiu, 1985; Gao et al., 2016). Third, geomorphic and environmental factors exert vital effects on these reefs. The geomorphic configuration of the Hainan Island radiated from central highlands (peak elevation 1,840 m) to peripheral seas, establishing source-to-sink pathways for weathered terrestrial materials since the Holocene (Wang et al., 2006; Xia, 2015; Gao et al., 2016). During the Holocene transgression and highstand (9,000-2,000 yr BP), intensified monsoon-driven precipitation promoted pervasive chemical weathering (Clift et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2020). The resultant dissolved and particulate fluxes, transported via fluvial systems (e.g., Nandu and Wanquan Rivers), delivered both nutrients and siliciclastic sediments to proximal reef zones (Hu et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2021b).

Wenchang City, situated along the northeastern coastal margin of Hainan Island, sustains the island’s most extensive coral reef ecosystems extending over 200 km. The CP area, a southeastern coastal sector of Wenchang, exemplifies a classic fringing reef system characterized by direct coastal attachment without intervening lagoon development. Field survey reveals that the reef comprises two zones. The inner flat is dominated by relict coral frameworks and Porites spp. microatoll structures with minimal live coral, while the outer flat mainly consists of fragmented Acropora branches forming unconsolidated rubble fields (Cai et al., 2015). The coral reef communities in the study area are located approximately 10 km from the mouth of Gao Long Bay and about 1-3 km from the shoreline, making them susceptible to terrigenous clastic input (Li et al., 2015; Figure 1B).Since the 1970s, anthropogenic pressures from coastal reclamation and intensive aquaculture operations have driven substantial reef degradation, with estimates indicating a loss of at least 50% of original reef structures across the region (Hughes et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study materials

To establish a comprehensive understanding of reef development history, systematic core drilling was conducted in 2011 across the fringing reef complex. Operations were strategically timed with low-tide periods to maximize accessibility, employing shoreline-perpendicular transects progressing seaward from the coastal margin (Figure 1C). Core extraction utilized rotary drilling technology, terminating penetration upon encountering consolidated Pleistocene substrates. The retrieved core samples were stored in core barrels to ensure stability and minimize disturbance during transportation. Post-recovery protocols involved refrigeration at 4°C within climate-controlled laboratory facilities to preserve sedimentological integrity for subsequent analyses.

A total of six drill cores were completed during this operation. Observations of the core samples revealed that reefal material was absent from the two landward-most drilling wells, and the investigation was focused on the four seaward cores containing reef sediments. The cores were designated as WC-01, WC-02, WC-03, and WC-04, which were arranged sequentially from land to sea (Figure 1C). They range in depth from 6 to 9 m, with recovery rates ranging from 60% to 80% across different stratigraphic intervals. Positioned along a 1 km coastal-perpendicular transect, the borehole distribution offers valuable insights into the lateral and vertical structure of the reef.

3.2 Facies analysis

Sedimentary facies were determined based on the compositional and textural attributes of the sediments, with the processes outlined below. Following recovery, the cores were first systematically logged for visual analysis. The work began with the preliminary identification of rock and bioclast types. Basic rock facies were classified according to the carbonate classification (Dunham, 1962; Embry and Klovan, 1971) and the standard textural scheme of the Udden-Wentworth nomenclature (Udden, 1914; Wentworth, 1922). Further detailed records of the rock features were made, including the delineation of sequence boundaries and hiatuses, as well as the documentation of physical features such as algal encrustation.

More detailed sedimentary analyses were conducted afterwards, including microscopical observations, X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) testing, and grain size analysis. First, petrographic microscopy involved preparing 30 resin-impregnated thin sections from stratigraphically representative intervals across three cores. Quantitative modal analysis via point-counting (300 counts/section) following Gazzi-Dickinson methodology determined component abundance ratios (Ingersoll et al., 1984). Second, XRD analysis was employed due to its sensitivity in distinguishing between fine-scale mineralogical components. It provided precise measurements of terrigenous and carbonate content that are critical for understanding the depositional environment. A total of 82 samples from four cores were analyzed using a X’Pert Pro powder X-ray Diffractometer at the China University of Geosciences (Wuhan). The samples were soaked in deionized water, stirred, and allowed to settle for 12 hours before being dried at 50°C and ground into fine powders (20-40 μm) with an agate mortar. For analysis, 0.4 g of each powdered sample was pressed into a glass sample holder. XRD scanning was conducted over a 5°-80° range, and the resulting diffraction patterns were processed with JADE software and the ICDD PDF database to calculate relative mineral contents. Finally, grain size characterization was performed on 58 core-derived samples at the laboratory center of the Hainan Academy of Ocean and Fisheries. Each sample was first sieved through a 2 mm mesh to segregate coarse (> 2 mm) and fine (< 2 mm) fractions. The coarse fraction’s mass proportion was gravimetrically determined, while the fine fraction was subjected to laser diffraction analysis using a Malvern Mastersizer 2000. Prior to analysis, carbonate dissolution was achieved through 3 mol/L HCl treatment (24-hour digestion), followed by organic matter removal via 20 mL of 20% H2O2 oxidation in a boiling water bath overnight. Subsequently, these samples were centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 4 minutes, after which half of the supernatant was decanted. The samples were treated with 0.5 mol/L sodium hexametaphosphate solution and soaked for 24 hours to ensure particle dispersion. After pre-treatment, the dispersed sample was thoroughly stirred, and an aliquot was transferred to the sample chamber of the laser granulometer for testing. After each test, the sample chamber was rinsed three times to prepare for subsequent samples. Grain size distributions were plotted by incorporating the proportions of > 2 mm and < 2 mm fractions, using grain size divisions based on the Udden-Wentworth scale (Udden, 1914; Wentworth, 1922).

3.3 Taxonomic analysis

Environmental reconstructions integrated both coral assemblage data and foraminiferal biofacies indices. For coral species identification, 66 coral samples were systematically collected in sequence from the bottom to the top of each core. Before identification, these samples were cleaned with a high-pressure water jet. This removed the surface mud and made the skeletal structures visible. Coral species were identified based on macroscopic features, including skeletal morphology, the shape and arrangement of coral cups, and colony growth forms, with reference to established classification systems and atlases (Wells, 1956; Zou et al., 1975). Generic-level identifications were prioritized for fossil specimens at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Additionally, 58 sediment samples were analyzed from three cores for foraminifera identifications using standardized processing. 50 g aliquots were oxidized with 10% hydrogen peroxide solution and were heated to boiling until the sediment was fully disaggregated, wet-sieved through 63 μm stainless steel mesh, and oven-dried at 40°C. Microfossil extraction utilized Leica M205C stereomicroscopy at China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), enabling further species-level identifications and quantitative counts (minimum 300 specimens/sample).

3.4 Radiocarbon dating

To ensure the reliability and precision of the dating results, well-preserved, fresh, and dense coral samples were first selected for XRD testing through careful core identifications. Samples with aragonite content exceeding 95%, signifying the preservation of unaltered aragonite coral and the absence of significant diagenetic alteration, were selected for subsequent radiocarbon dating. 13 coral samples meeting the selection criteria were securely sealed and sent to Beta Analytic Laboratory in the United States for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) 14C testing. The procedures for AMS radiocarbon dating were conducted following the workflow outlined on the Beta Analytic Laboratory’s official website (https://www.radiocarbon.com/beta-lab).

All radiocarbon dates were calibrated using the calibration program BetaCal 4.2 (Ramsey, 2009), and calibration curve Marine 20 (Reimer et al., 2020). This study uses the ΔR value of -25 ± 20 years for age calibration, corresponding to the average value proposed by Southon et al. (2002) for the south/central part of the South China Sea. The value may be the best current estimate of variance in the local open water marine reservoir effect for Wenchang region and adjacent areas. Results are reported as calibrated age ranges at 95.4% probability (or at 2σ) and median age in years Before Present (cal yr BP).

4 Results

4.1 Facies and sediment characteristics

The diagnostic lithofacies of the CP reef complex have been delineated through integrated sedimentological analyses, combining macroscopic core logging, petrographic microscopy, grain sizes and quantitative mineral characterization. The lithofacies exhibit a hybrid terrigenous-carbonate framework, which is characterized by coral skeletons or clasts, mixed with various bioclastic particles and siliciclastic components. Based on the differential abundance of siliciclastics and coralline, five distinct lithofacies have been discerned. Each of the lithofacies characteristics and associated sedimentary attributes has been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Lithofacies code | LF1 | LF2 | LF3 | LF4 | LF5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nomenclature | Coral framestone facies | Sand-bearing coral framestone facies | Muddy, coral framestone facies | Sandy, mixed coral, rudstone facies | Coral clasts, sandstone facies |

| Texture | Well-preserved coralline framework textures | Well-preserved coral morphology, with fine-grained carbonate and siliciclastic sediments | In situ corals, with muddy terrigenous sediments | Admixure of coral fragments, bioclastic particles and siliciclastic sediments | Fine- to medium-grained, sandy textures |

| Components | In-situ coral framework associated with minor siliciclastic components (< 10 %) |

Major coral framework associated with siliciclastic components (ranging from 10 to 25 %) | Major coral framework associated with a clay matrix (ranging from 15 to 30 %) | Fragments of coral clasts present (comprising 40 to 50 %) with 20-50% medium- to coarse-sized siliciclastics | Dominance of siliciclastic components (ranging from 50 to 70%) with 20-40% coral and other bioclastic fragments |

| Fossils | Massive coral colonies of Favia, Favites, and Cyphastrea; occurrences of thin crusts of coralline algae (ca 0.5-0.8 mm) | Massive coral colonies of Favia and Favites | Massive coral colonies of Favia and Favites | Coral fragments, along with subordinate amounts of foraminifera, gastropods, and echinoderm debris, and minor traces of calcareous encrustation on the coral skeleton | Coral debris, along with some fragments of foraminifera and echinoid spines |

Summary of lithofacies characteristics and associated sedimentary attributes.

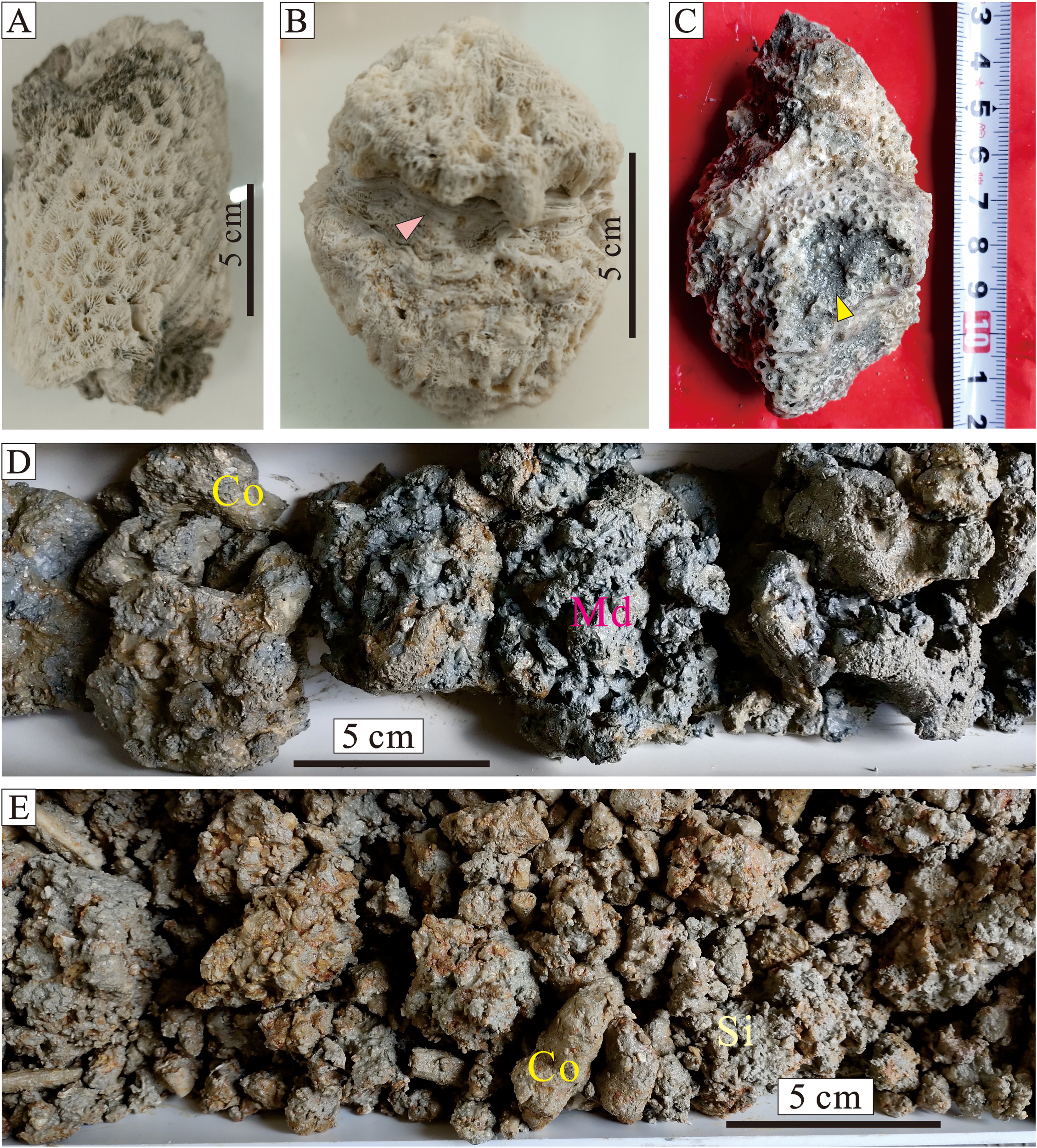

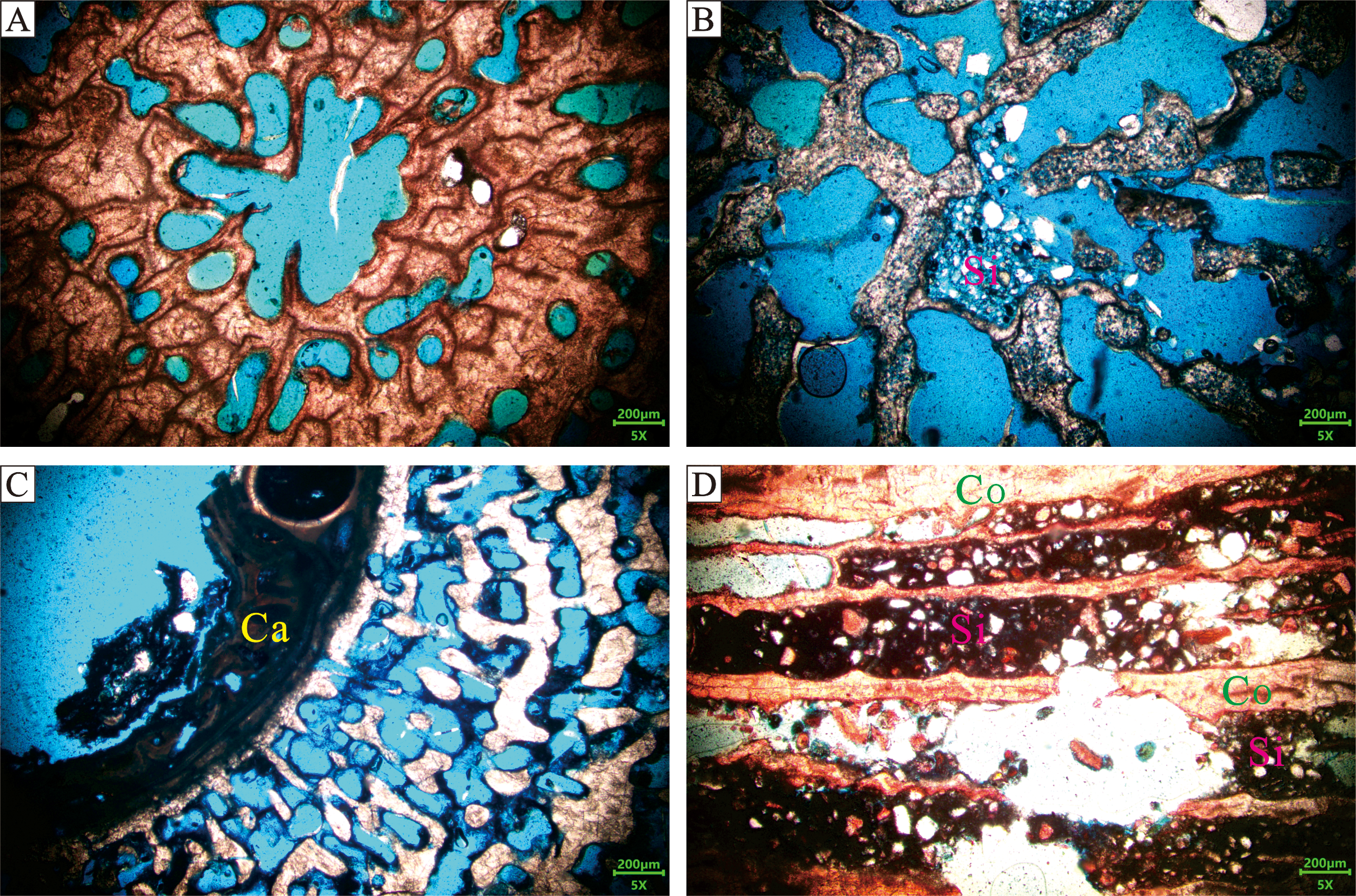

4.1.1 LF1: coral framestone facies

This lithofacies exhibits light gray to white coloration with well-preserved coralline framework textures, displaying core thicknesses of 1.0-1.5 m. The dominant identifiable coral specimens within the lithofacies include massive colonies of Favia, Favites, and Cyphastrea. Hand specimens reveal that coral corallites have circular to elliptical cross-sections and well-developed radial septa (Figure 2A). Microscopic analysis shows intact cross-sectional coral architectures that feature interconnected pore networks (Figure 3A). Siliciclastic components account for less than 10% of the volume and occur sporadically within the framework interstices (Figure 3B). These detrital components primarily comprise fine-grained, angular to subangular quartz and feldspar grains. Additionally, coral surfaces are locally bounded by thin crusts of coralline algae (ca 0.5-0.8 mm), forming a distinct coating on the coral skeleton (Figures 2B, 3C).

Figure 2

Representative core photographs showing identified lithofacies of the CP fringing reef. (A) Coral framestone facies (LF1) showing Favites corals that form a massive coral framework. Coral individuals are circular or elliptical in shape, with diameters ranging from 4-6 mm. The primary septa consist of 6-8 plates, while the secondary septa are shorter and thinner compared to the primary septa (well WC-04, ~6.95 m depth). (B) Massive corals encrusted with coralline algal crusts (ca 0.8 mm thick, indicated by the pink arrow) as found in a hand specimen (well WC-04, ~7.00 m depth). (C) Sand-bearing coral framestone facies (LF2) showing well-preserved coral morphology, with coral matrix voids infilled by fine-grained carbonate and siliciclastic sediment (indicated by the yellow arrow, well WC-03, ~3.50 m depth). (D) Close-up picture of the muddy, coral framestone facies (LF3) from the core of well WC-04 (~ 0.55-0.8m depth), showing coral clasts (Co) embedded in a mud-rich sediment matrix (Md). (E) Close-up picture of the sandy, mixed coral, rudstone facies (LF4) from the core of well WC-02 (~ 3.70-3.90 m depth), showing variable proportions of siliciclastic and bioclastic admixtures. Coral clasts (Co) are surrounded by sandy siliciclastics (Si).

Figure 3

Representative microphotographs illustrating the characteristics of LF1 and LF2. (A) Coral framestone facies (LF1) exhibiting well-preserved cross-sectional coral framework (well WC-04, ~1.36 m depth). (B) Within the LF1, minor siliciclastic components (less than 10% by volume, denoted as Si) occurring sporadically within the interstices of the coral framework (well WC-04, ~7.00 m depth). (C) Photomicrograph of the LF1 showing locally encrusting red coralline algae (denoted as Ca) on the coral framework (well WC-04, ~5.50 m depth). (D) Within LF2, siliciclastic constituents, ranging from 10% to 25%, show more enrichment compared to LF1. These main siliciclastic components (Si) are fine-grained, angular quartz and feldspar grains, along with some amounts of mud-sized clay minerals, distributing uniformly within the pore networks of the coralline framework (denoted as Co) (well WC-02, ~3.53 m depth).

4.1.2 LF2: sand-bearing coral framestone facies

This lithofacies consists of well-preserved coral morphology, with coral species distinguishable. Cores observations revealed a coral framework with voids infilled with fine-grained carbonate and siliciclastic sediment (Figures 2C, 3D). The main siliciclastic components are fine-grained, angular quartz and feldspar grains, along with mud-sized clay minerals (Figure 3D). Microscopic statistics show that siliciclastic constituents, ranging from 10% to 25%, are more enriched when compared with LF1.

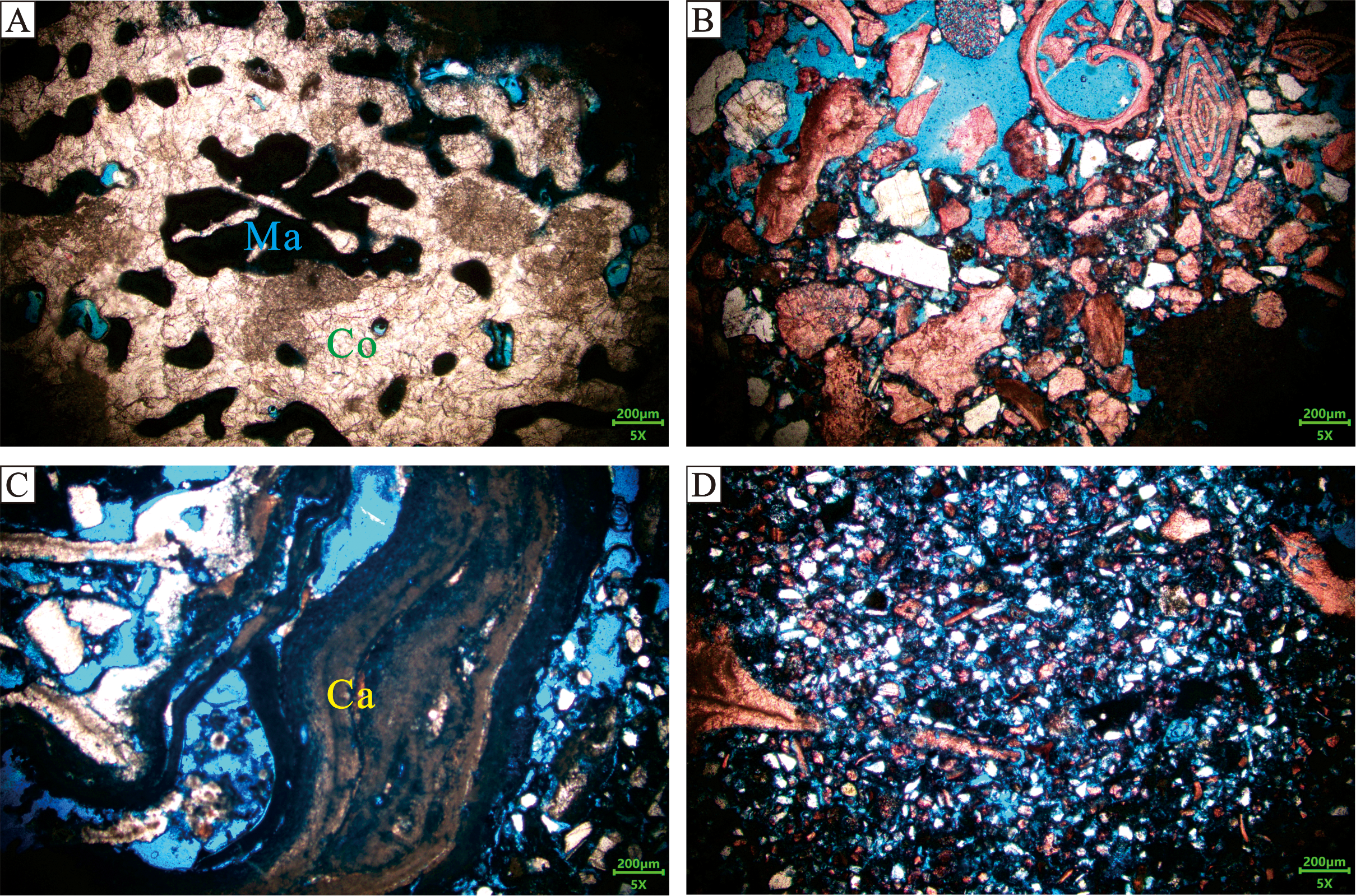

4.1.3 LF3: muddy, coral framestone facies

This lithofacies is characterized by the presence of in situ corals and muddy terrigenous sediments (Figure 2D). The coral skeletons generally retain their primary framework, with some coral clasts existing. Thin section observations reveal that coral framework is pervasively occluded by a clay matrix (15-30%) (Figure 4A), and there are sporadic occurrences of silt-sized quartz and feldspar grains.

Figure 4

Representative microphotographs illustrating the characteristics of LF3-LF5. (A) Primary coral framework (Co) is occluded by a clay matrix (Ma) within the LF3 (well WC-04, ~0.48 m depth). (B) Photomicrograph of LF4, exhibiting coral clasts and subordinate bioclastic fragments mixed with medium- to coarse-sized, angular to subangular quartz and feldspar grains (well WC-04, ~5.75 m depth). (C) Calcareous encrustation is observed as isolated, thin (~1 mm) crusts of crustose coralline algae on coral clasts (well WC-03, ~3.25 m depth). (D) LF5 is characterized by moderately sorted, fine- to medium-grained siliciclastic components (50-70% by volume), mixed with bioclastic fragments comprising 20-40% of the lithofacies. Coral skeletons exhibit extensive mechanical fragmentation, stained red with Alizarin Red S (well WC-04, ~1.70 m depth).

4.1.4 LF4: sandy, mixed coral, rudstone facies

This lithofacies exhibits variable proportions of siliciclastic and bioclastic admixtures, with depositional units measuring 30-150 cm in thickness across different cores (Figure 2E). The bioclastic particles range from 40 to 50%. They are predominantly consisted of angular coral fragments (0.5-2 cm), along with subordinate amounts of foraminifera, gastropods, and echinoderm debris. Coral material is primarily present as fragments, while intact specimens are uncommon. Additionally, siliciclastic components, constituting 20-50% of the lithofacies, are mainly composed of medium- to coarse-sized quartz and feldspar grains with angular to subangular morphologies (Figure 4B). Minor traces of calcareous encrustation are also observed in the form of isolated, thin (0.5-1 mm) crusts of crustose coralline algae on the coral skeleton (Figure 4C).

4.1.5 LF5: coral clasts, sandstone facies

This lithofacies is dominated by moderately sorted, fine- to medium-grained siliciclastic components (50-70%), comprising angular to subangular quartz, feldspar and minor clay matrix (Figure 4D). Bioclastic components are mainly coral debris, showing extensive mechanical fragmentation. They account for 20 - 40%, along with 5% of other bioclastic content, such as foraminifera and echinoid spine.

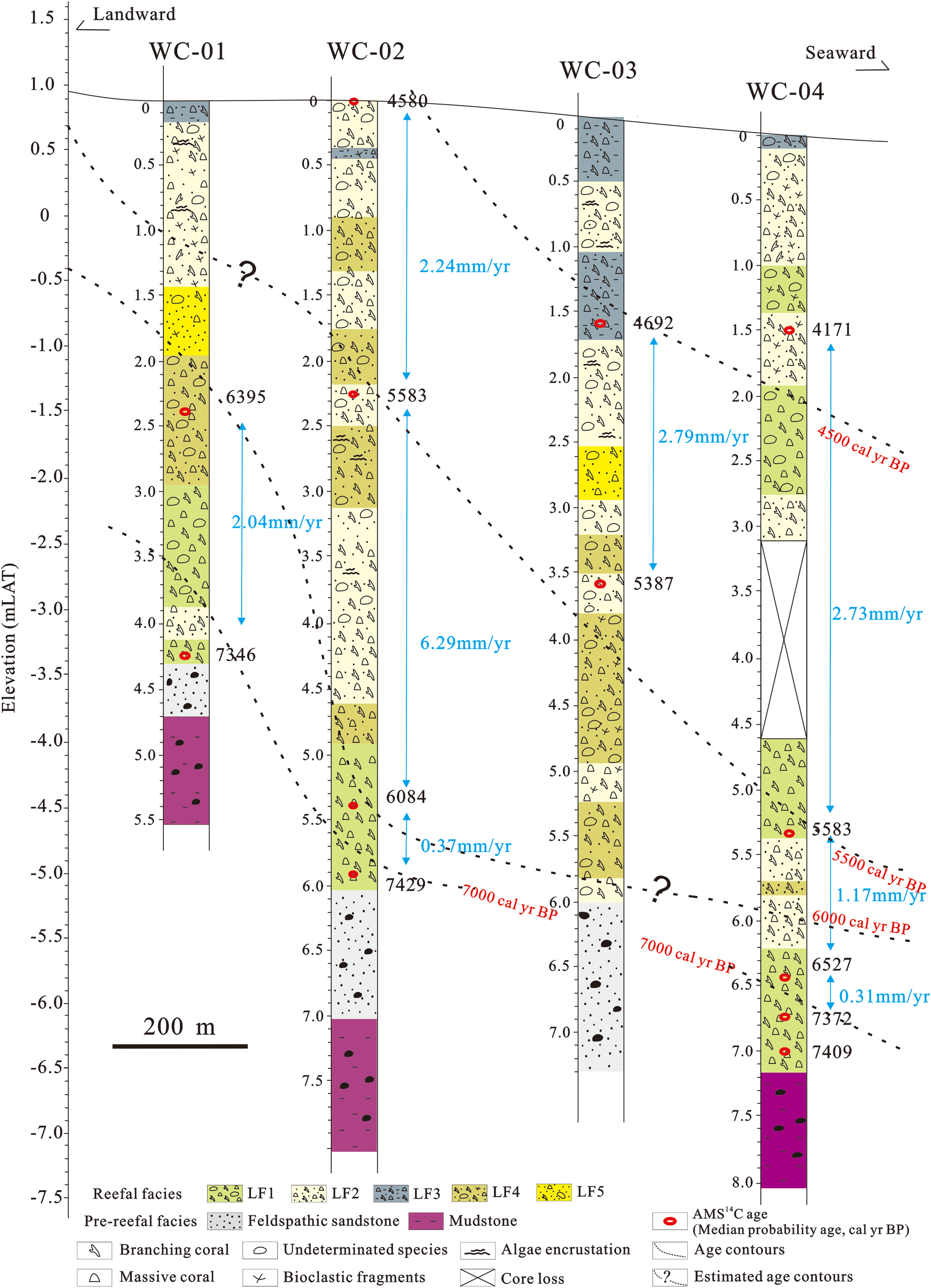

4.2 Reef chronostratigraphy and vertical accretion rates

The chronostratigraphy of the reef was reconstructed through 13 in situ coral specimens from four drill cores (Table 2; Figure 5). All dated samples fall within the Holocene period, exhibiting stratigraphic coherence without age reversals. Core WC-01 records basal ages of 7,346 cal yr BP (~4.25 m depth) and 6,395 cal yr BP (~2.31 m depth). WC-02 displays a vertical age progression from 7,429 cal yr BP (base) to 4,580 cal yr BP (shallowest). WC-03 contains mid-Holocene deposits at 5,387 cal yr BP (~3.56 m depth) and 4,692 cal yr BP (~1.56 m depth). WC-04 preserves the most complete sequence, with basal ages clustering at 7,409 cal yr BP and terminating at 4,171 cal yr BP. The stratigraphic congruence between WC-01 and WC-04 basal layers indicates reef initiation ~7,400 cal yr BP (Figure 5). The most recent age, 4,171 cal yr BP, was recorded in core WC-04. Given 1.5 m of unconsolidated sediment overlying the youngest dated horizon in WC-04, we constrain reef accretion cessation after ~4,000 cal yr BP.

Table 2

| Well | Sample code | Depth (m) | Material | Conventional age (yr BP) | Calibrated age (95 % probability) (cal yr BP) |

Median probability age (cal yr BP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WC-04 | ZK6C-1 | 7.00 | Coral | 7080 ±30 | 7272-7551 | 7409 |

| ZK6C-2 | 6.72 | Coral | 7040 ±30 | 7231-7512 | 7372 | |

| ZK6C-3 | 6.46 | Coral | 6260 ±30 | 6357-6695 | 6527 | |

| ZK6C-4 | 5.36 | Coral | 5380 ±30 | 5429-5745 | 5583 | |

| ZK6S-18 | 1.50 | Coral | 4230 ±30 | 3983-4360 | 4171 | |

| WC-03 | ZK5CI-4 | 3.56 | Coral | 5190 ±30 | 5246-5557 | 5387 |

| ZK5CI-9 | 1.62 | Coral | 4630 ±30 | 4514-4843 | 4692 | |

| WC-02 | ZK4C-1 | 5.90 | Coral | 7100 ±30 | 7289-7563 | 7429 |

| ZK4C-2 | 5.40 | Coral | 5840 ±30 | 5925-6248 | 6084 | |

| ZK4C-3 | 2.25 | Coral | 5380 ±30 | 5429-5745 | 5583 | |

| ZK4S-16 | 0 | Coral | 4540 ±30 | 4411-4780 | 4580 | |

| WC-01 | ZK3CI-1 | 4.25 | Coral | 7010 ±30 | 7198-7485 | 7346 |

| ZK3CI-20 | 2.31 | Coral | 6140 ±30 | 6248-6567 | 6395 |

Radiocarbon ages on individual fossil corals from vibrocores.

Samples were securely sealed and sent to Beta Analytic Laboratory in the United States for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) 14C testing. The procedures for AMS radiocarbon dating were conducted following the workflow outlined on the Beta Analytic Laboratory’s official website (https://www.radiocarbon.com/beta-lab). All radiocarbon dates were calibrated using the calibration program BetaCal 4.2, and calibration curve Marine 20. A ΔR value of -25 ± 20 was applied for the marine reservoir corrections.

Figure 5

Chronostratigraphic framework of the CP fringing reef along transect shown in Figure 1, based on AMS 14C calibrated ages of selected samples (locations are marked by red circles). Vertical arrows show average reef growth rates. Inferred age contours are based on dated intervals within the core.

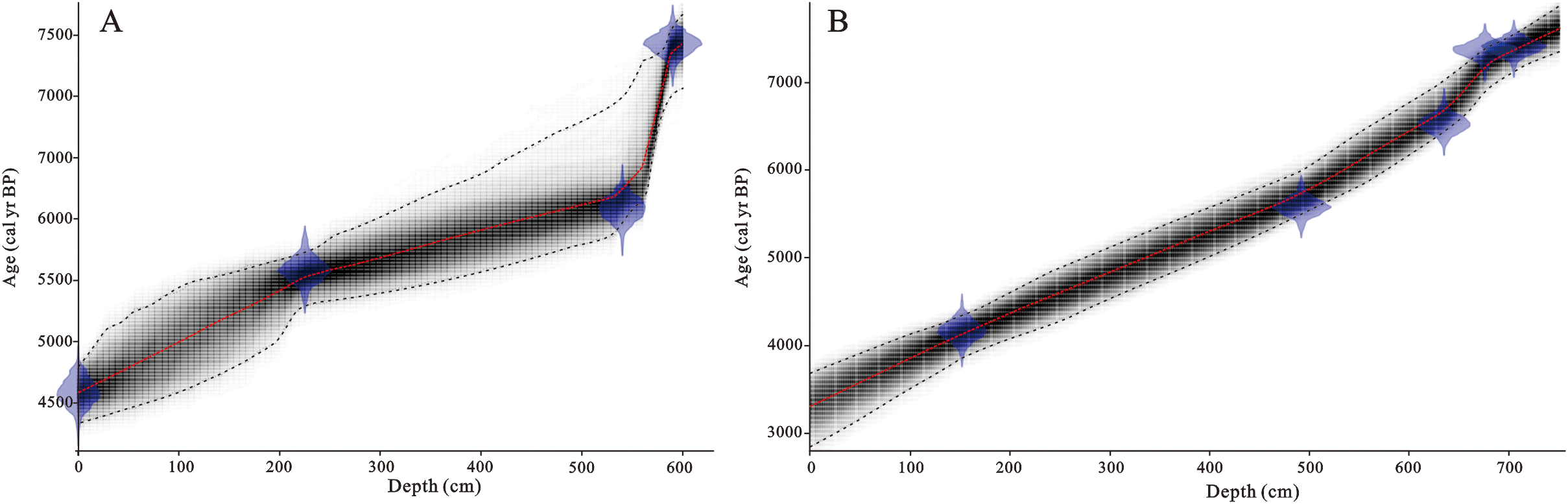

The age-depth relationships for wells WC-02 and WC-04 were calculated using the Bayesian approach (Figure 6). Based on the slope of the age-depth curve and the dating results from the cores, the variation trend of vertical accretion has been determined. During the initial establishment phase (~7,400-6,000 cal yr BP), accretion rates remained subdued at 0.31-0.37 mm/yr. Subsequent mid-Holocene intensification (~6,000-5,500 cal yr BP) exhibited accelerated accretion rates to peak values of 6.29 mm/yr. However, the accretion rate declined to about 2.70 mm/yr after 5,500 cal yr BP.

Figure 6

The age-depth models for wells WC-04 (A) and WC-06 (B) using a Bayesian approach, based on the distributions of individual dates (blue diamonds). The red line represents the median probability age, while the area between the black dashed lines indicates chronological uncertainties.

5 Discussion

5.1 Phase of reef growth

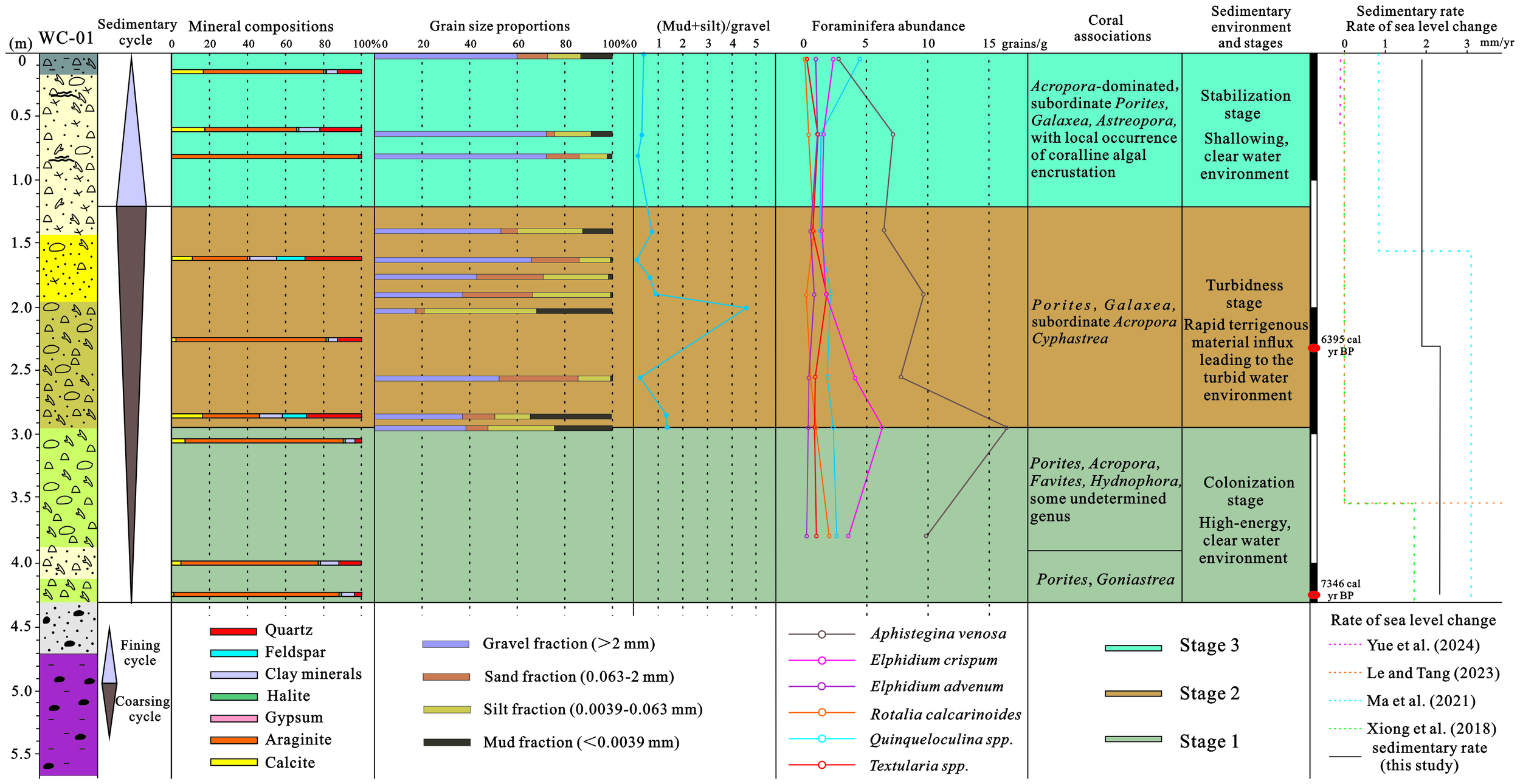

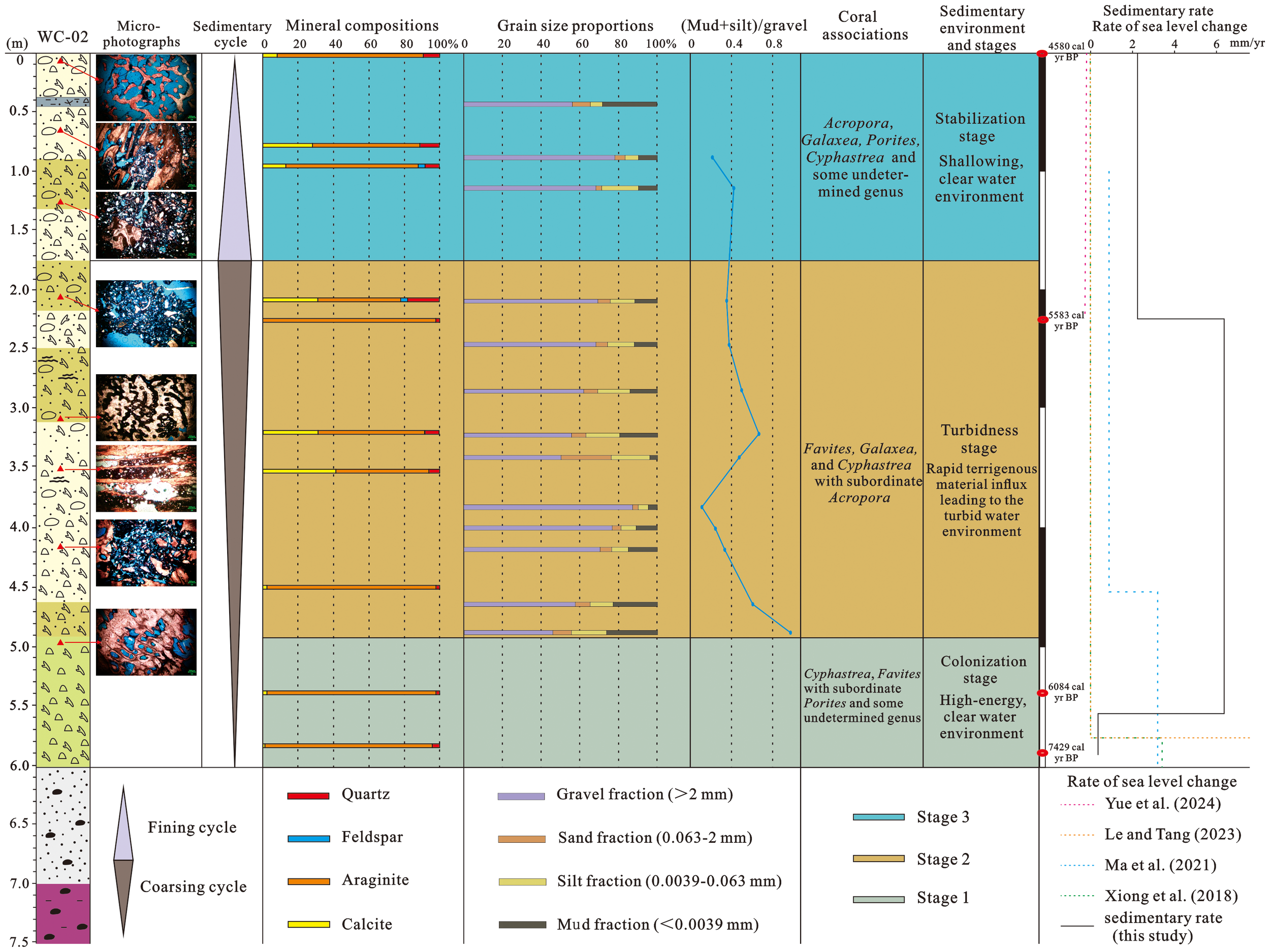

Four paired cores retrieved from the reef flat reveal a succession of grayish-white, gravel-bearing, medium- to coarse-grained feldspathic sandstone overlying reddish-brown gravelly mudstone at 4.5-7.0 m depth. Although undated, these strata exhibit lithological characteristics consistent with the Lower Holocene Wanning Formation (8-10 cal ka BP) and Upper Pleistocene Basuo Formation (~12 cal ka BP) documented in Hainan Island’s Quaternary coastal sequences (Zhang et al., 1987). The recovery of these units confirms the acquisition of a complete Holocene reef sequence. Afterward, integrated analysis of sediment architecture, including lithofacies, mineral composition, grain size, and variations in foraminifera and coral assemblages, identifies three developmental stages in the CP fringing reef evolution (Figures 7–10; Table 3).

Figure 7

Composite core log of well WC-01, displaying (from left to right) lithofacies cycles, mineral composition, grain size content, and palaeo-ecological data (including foraminifera abundance and coral species association). The identified depositional stages include the colonization stage (stage 1, ~3.0-4.4 m depth), the turbidity stage (stage 2, ~1.2-3.0 m depth), and the stabilization stage (stage 3, 0-1.2 m depth). The grain size of deposits displays an upward coarsening trend from the colonization stage to the turbidity stage, followed by a fining cycle during the stabilization stage. The sedimentation rate remained about 2 mm/yr, and has been greater than the sea-level change rate since 7,400 cal yr BP. The legend for the lithologic log is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 8

Composite core log of well WC-02, showing (from left to right) microphotographs, lithofacies cycles, mineral composition, grain size content, and palaeo-ecological data (coral species association). The identified depositional stages include the colonization stage (stage 1, ~4.9-6.0 m depth), the turbidity stage (stage 2, ~1.75-4.90 m depth), and the stabilization stage (stage 3, 0-1.75 m depth). The grain size of deposits displays an upward coarsening trend from the colonization stage to the turbidity stage, followed by a fining cycle during the stabilization stage. The sedimentation rate increased from 0.37 mm/yr (ca 7,400-6,000 cal yr BP) to 6.29 mm/yr (ca 6,000-5,500 cal yr BP), then decreased to about 2.24 mm/yr (after 5,500 cal yr BP). In comparison, the sea-level change rate has significantly declined to nearly 0 mm/yr since 7,400 cal yr BP. The legend for the lithologic log is shown in Figure 5.

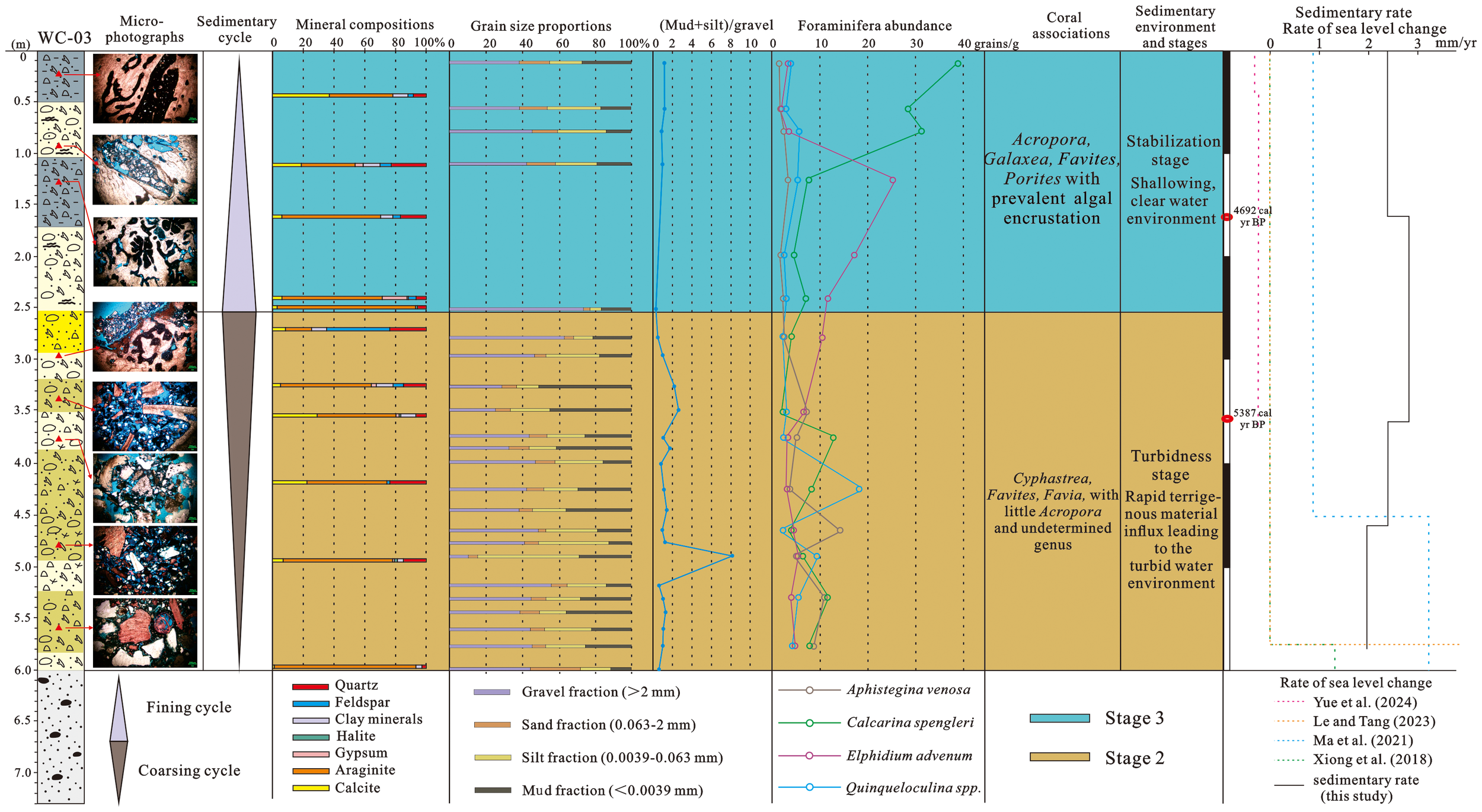

Figure 9

Composite core log of well WC-03, exhibiting (from left to right) microphotographs, lithofacies cycles, mineral composition, grain size content, and palaeo-ecological data (including foraminifera abundance and coral species association). The identified depositional stages only include the turbidity stage (stage 2, ~3.2-6.0 m depth) and the stabilization stage (stage 3, 0-3.2 m depth). The grain size of deposits displays an upward coarsening trend during the turbidity stage, followed by a fining cycle during the stabilization stage. The sedimentation rate remained consistently between 2 and 2.79 mm/yr, and has been greater than the sea-level change rate during the reef evolution. The legend for the lithologic log is shown in Figure 5.

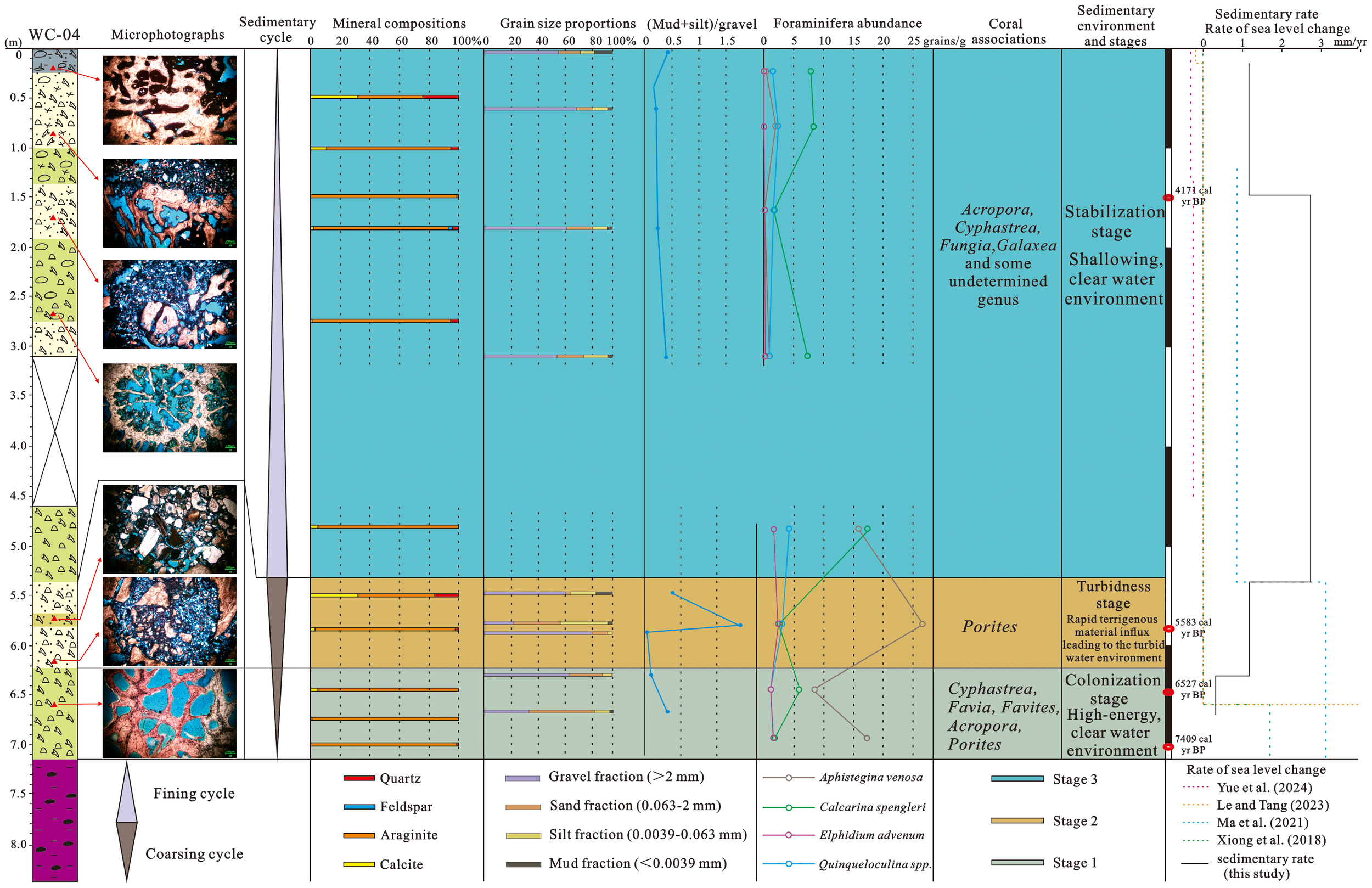

Figure 10

Composite core log of well WC-04, demonstrating (from left to right) microphotographs, lithofacies cycles, mineral composition, grain size content, and palaeo-ecological data (including foraminifera abundance and coral species association). The identified depositional stages include the colonization stage (stage 1, ~6.2-7.15 m depth), the turbidity stage (stage 2, ~5.4-6.2 m depth), and the stabilization stage (stage 3, 0-5.4 m depth). The grain size of deposits displays an upward coarsening trend from the colonization stage to the turbidity stage, followed by a fining cycle during the stabilization stage. The sedimentation rate increased from 0.31 mm/yr (ca 7,400-6,400 cal yr BP) to 2.73 mm/yr (ca 5,500-4,000 cal yr BP), then slightly decreased (after 4,000 cal yr BP). The sea-level change rate has significantly declined to nearly 0 mm/yr since 7,400 cal yr BP. The legend for the lithologic log is shown in Figure 5.

Table 3

| Evolutionary stage | Lithofacies | Component characteristics | Biotic assemblage | Sedimentation Rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral composition | Grain size distribution | Coral association | Foraminifera assemblage | |||

| Coral colonization stage | Dominated by LF1, interbedded with thin strata of LF2 | Aragonite and calcite collectively constituting over 80% of the mineral assemblage, subordinate quartz and clay minerals | Dominated by intact coral skeleton, with large grain components > 2mm | Diversified communities, with emergent genus of Goniastrea, Porite, Acropora, Favites, and several unidentified genera | Foraminiferal amounts are sparse (< 5 specimens/g), dominated by Amphistegina venosa | Relatively low accretion rates (ca 0.35 mm/yr) |

| Turbidness stage |

Associations of LF2, LF4, and LF5 | A fluctuating aragonite content (25-80%) along with quartz (10-25%) and clay minerals (5-10%) | A predominance of gravel-sized reef-derived clasts (10.4-87.4%), interspersed with silt-mud fractions (9.2-84.5%), and the (silt + clay) / gravel ratio is variable | Coral diversity and abundance decline markedly with main coral species identifiable as Cyphastrea, Favites, and Galaxea | Foraminiferal abundance fluctuates, generally declining over time | Accelerated accretion rates (up to 6.39 mm/yr) |

| Stabization stage |

Dominated by LF2 and LF3, with subordinate occurrences of LF1 | Aragonite constitutes over 80% of the main mineral composition, whereas terrigenous clastic minerals (predominantly quartz), comprise less than 10% | Gravel-sized bioclastic fractions (25.3-73.7%) intermixed with silt-mud siliciclastics (13.7-66.5%), yielding consistent (mud + silt) / gravel ratios of 0.2-0.4 |

Coral assemblages begin to increase, with Acropora spp. dominant, and Cyphastrea, Fungia, Galaxea, and several undetermined taxa as subordinates | Certain foraminiferal genera, such as Calcarina spengleri, show a relative increase, with Amphistegina venosa and Calcarina spengleri exceeding 15 specimens/g in abundance | Reduced accretion rate (ca 2.70 mm/yr) |

Summary of sedimentary characteristics for different evolutionary stages within CP fringing reef.

The initial stage is characterized by well-preserved coral deposits with minimal siliciclastic input (< 10%), as demonstrated by core observations and/or thin-section petrography (Figures 7, 9, 10). During this stage, the main lithofacies associations are dominated by LF1, interbedded with thin strata of LF2. XRD analysis confirms that aragonite and calcite collectively constitute over 80% of the mineral assemblage, subordinate quartz and clay minerals also being identified. Notably, coral assemblages evolve from monospecific dominance to more diversified communities. For example, in the lower section of Well WC-01 (~3-4.3 m depth), the main coral species are initially dominated by Goniastrea and Porites. Moving upward, species diversity increases with the emergence of Acropora, Porites, Favites, and several unidentified genera (Figure 7). Although foraminiferal assemblages are sparse (< 5 specimens/g), they are dominated by Amphistegina venosa, which is a diagnostic indicator of high-energy reefal environments (Parker and Gischler, 2011; Meng et al., 2022). Collectively, these sedimentological and biological data suggest persistently clear-water conditions that limited terrigenous sedimentation, facilitating coral colonization and subsequent diversification succession. In this study, this stage is designated as the coral colonization stage based on these sedimentological characteristics.

The second stage is characterized by a lithofacies transition from LF1 to associations of LF2, LF4, and LF5. Grain-size analyses and microscopic observations indicate that these lithofacies associations mainly consist of reef-derived bioclastic fragments intermingled with terrigenous grains. For example, the WC-02 core (~1.75-4.90 m depth) exhibits a grain-size distribution characterized by a predominance of gravel-sized reef-derived clasts (45.8-87.4%), interspersed with silt-mud fractions (9.2-46.3%), and a (silt + clay)/gravel ratio ranging from 0.11 to 0.97 (Figure 8). Correspondingly, XRD results show a fluctuating aragonite content (25-80%) alongside quartz (10-25%) and clay minerals (5-10%) (Figures 7-10). These component and mineralogical characteristics clearly point to a significant enhanced influx of terrigenous materials into the coral area. Under these conditions, both coral diversity and foraminiferal abundance decline markedly. The identifiable coral species are limited to Cyphastrea, Porites, and Galaxea. Foraminiferal abundance fluctuates from a few to several specimens per gram (Figures 7, 9, 10). Overall, these proxies delineate a “turbid-water stage” characterized by terrestrial sediment dominance over reef-building processes.

Compared to the second stage, the third developmental stage is marked by relatively stable siliciclastic and carbonate sedimentation. For instance, the upper section of the WC-04 core (~0-5.4 m depth) shows stable gravel-sized bioclastic fractions (56-70%) intermixed with silt-mud siliciclastics (15-33%), yielding consistent (mud + silt)/gravel ratios of 0.2-0.4. XRD analyses confirm that aragonite constitutes over 80% of the main mineral composition, whereas terrigenous clastic minerals (predominantly quartz) comprise less than 10% (Figure 10). In the context of this setting, coral assemblages begin to increase again, with identifiable genera including Acropora, Cyphastrea, Fungia, Galaxea, and several undetermined taxa. Notably, Acropora spp. emerge as the dominant coral genus, owing to their rapid vertical growth during periods of simple coral communities (Perry et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2022). Certain foraminiferal genera, such as Calcarina spengleri show a relative increase. Even Amphistegina venosa and Calcarina spengleri achieve abundances exceeding 15 specimens/g. (Figure 9). Besides, hand specimen observations reveal the onset of extensive algal encrustation on coral surfaces. This phenomenon is likely attributed to episodic shallowing of the water column, which hindered coral growth and facilitated the establishment of algal dominance (Solihuddin et al., 2016; Gischler et al., 2019). Consequently, this stage is defined as a period of stable terrigenous clastic input that restored clear-water conditions. Relatively shallow and clear water facilitated biotic recovery and ecosystem recovery.

5.2 Depositional model for reef development

Radiometric age dating indicates that reef development in the CP region had initiated by at least 7,400 cal yr BP (Figure 5). This period coincided with the Holocene highstand, a global proliferation phase for coral reef development (Lewis et al., 2013; Smithers and Larcombe, 2003; Leonard et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2024). As mentioned above, the deposition of the LF1 coral framestone facies serves as a typical marker for the colonization stage, and subsequent depositional stages document the progressive influx of terrigenous sediments into the reef system. The initial land-derived input is constrained by an age of 6,376 ± 155 cal yr BP from well WC-01 (at approximately 2.4 m depth), indicating that the end of coral colonization and siliciclastic influx occurred prior to 6,400 cal yr BP (Figure 5). In terms of depositional rate, the first stage is characterized by a vertical framework buildup of approximately 2.0 m, with an estimated accumulation rate of 0.31-0.37 mm/yr (ca 0.35 mm/yr; Figure 5). The subsequent progression of siliciclastic sedimentation significantly altered the reef architecture, transitioning from vertically accreting frameworks to laterally prograding mixed deposits. Between 6,400 and 5,500 cal yr BP, all cores exhibit lithologies characterized by a mixture of sandy terrigenous clasts and coral fragments. The accumulation rate accelerated to 6.29 mm/yr, as recorded in core WC-02. After 5,500 cal yr BP, until the reef cessation, deposits of mixed siliciclastic and carbonate sedimentations prograded seaward, especially it was confined to the seaward cores (WC-03 and WC-04) after around 4,500 cal yr BP. During this stage, the depositional rate declined to the stable range of 2.24-2.79 mm/yr (Figure 5). Dullo (2005) compiled vertical accretion rates for Holocene coral reefs from the Indian and Pacific Oceans, which ranged from 0.67 to 8.57 mm/yr, with an average of 4.40 mm/-yr. Correspondingly, the CP reef complex initially exhibited accretion rates below the average, reached a peak above the average during its mid-development, and ultimately stabilized at values below the mean. Variations in sedimentation rates correspond with terrigenous clastic loading and hydrodynamic instability. Increased sedimentation rates likely reflect an enhanced supply of terrigenous clasts, resulting in abrupt shifts in the relative proportions of terrigenous and biogenic fragments, as described in the “turbidness stage”. Conversely, when terrigenous input stabilizes, compositional equilibrium is restored, resulting in a steady state of the (mud + silt)/gravel ratio, as described in the preceding “stabilization stage”.

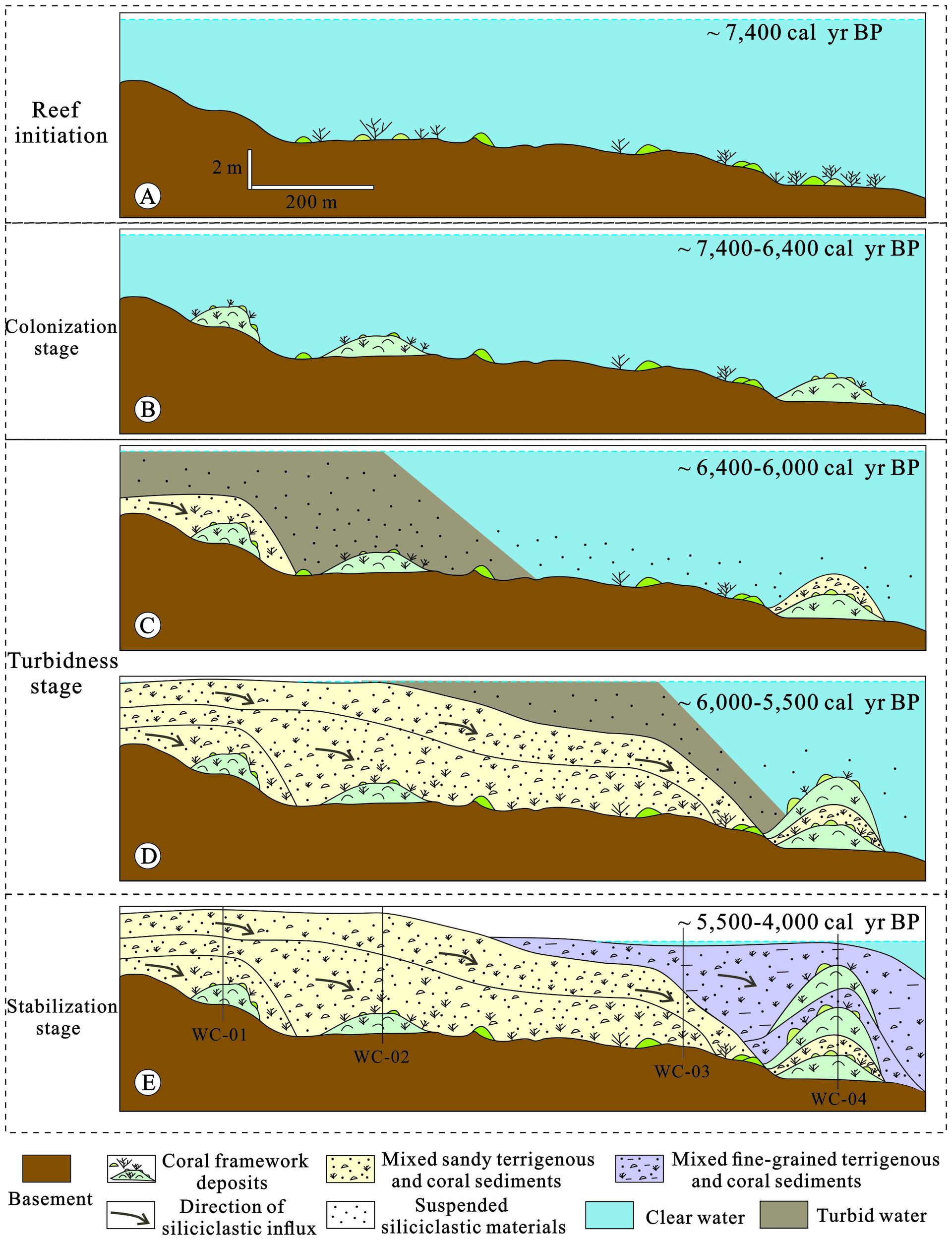

In summary, the sedimentary evolution model of the CP fringing reef is established through integrated sedimentological and chronostratigraphic analysis (Figure 11). During the mid-Holocene highstand, accommodation space for reef development increased to 1-2 m above modern sea level (Le and Tang, 2023; Yue et al., 2024), providing the ideal condition for reef initiation at ∼7,400 cal yr BP (Figure 11A). From approximately 7,400 to 6,400 cal yr BP, the CP reef was largely unaffected by terrigenous sediment influx and experienced a slow rate of vertical accretion. During the pioneer phase, clear-water conditions promote a progressive shift in coral communities from single-species dominance to multispecies (Figure 11B). Subsequently, during 6,400-5,500 cal yr BP, a marked influx of terrigenous sediments induced a transition in the water column from clear to persistently turbid conditions. Concurrently, the seaward accumulation of terrigenous sediments led to a rapid increase in sedimentation rates, facilitating a shift from vertical accretion to lateral progradation of the reef (Figures 11C, D). These environmental changes resulted in fluctuations in bioclast components and a significant reduction in coral species diversity. Finally, during approximately 5,500-4,000 cal yr BP, the system entered a phase of reduced siliciclastic input and improved water conditions. The restoration of shallow photic conditions and enhanced water clarity promoted the dominance of fast-colonizing coral genera, such as Acropora spp., thereby facilitating the recovery of the coral community (Figure 11E).

Figure 11

Conceptual model of reef development for the CP fringing reef. (A) Reef initiation around ~7,400 cal yr BP during the Holocene highstand. (B) Coral reef sparsely distributed and primarily experienced a low vertical accretion during a clear-water stage (~7,400-6,400 cal yr BP). (C) Terrigenous clastics began to locally influence the reef system (~6,400-6,000 cal yr BP). (D) Continued terrigenous clastic accumulation towards the seaward side, facilitating the lateral progradation of deposits (~6,000-5,500 cal yr BP). (E) Terrigenous clastic input occurred at a relatively low deposition rate, promoting water quality improvement and the recovery of the coral community (~5,000–4,000 cal yr BP).

5.3 Comparison with other Holocene turbid-water coral reefs

Traditional perspectives emphasize that sea-level fluctuations are the primary factor influencing the development of turbid-water coral reefs (Perry et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2016b; Lin et al., 2023). During rapid sea-level rise (e.g., mid-Holocene transgression), reefs typically adopt a “catch-up” growth mode, sustaining vertical accretion to match rising water depths (Twiggs and Collins, 2010; Solihuddin et al., 2015; Rodriguez-Ruano et al., 2023). This stage was characterized by vertical accretion of a mixture of terrestrial materials (e.g., quartz, feldspar, clay) and corals, where siliciclastic content could reach up to 40% (Palmer et al., 2010). Although branching corals (e.g., Acropora, Goniastrea, Montipora) rapidly constructed frameworks under high turbidity (Perry et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2016a, 2018; Gischler et al., 2023), overall reef growth occurred at a relatively slow rate (Ryan et al., 2016a; Sanborn et al., 2020). After sea-level stabilization (e.g., mid- to late Holocene period), constrained vertical accommodation promotes lateral expansion through wave or tidal sediment redistribution, and this process results in the formation of extensive reef flats (Lewis et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2016a; Bonesso et al., 2023). These mature systems exhibit either pure carbonate or mixed siliciclastic-carbonate facies, which are dominated by stress-tolerant massive corals (e.g., Porites, Goniastrea, Siderastrea) (Solihuddin et al., 2015; Dechnik et al., 2021; Bonesso et al., 2022).

However, in our study, reef development appears to be controlled by terrestrial clastic sediment deposition rather than sea level changes. Previous studies have demonstrated that the South China Sea experienced a rapid sea-level rise following the ice age in the early Holocene (ca. 11,500 a BP) (Groh and Harff, 2023; Xu et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025), reaching a peak approximately 3-4 m above the present level between 6,800 and 5,800 a BP (Bradley et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2021). Following this highstand period (post-7,000 a BP), the sea level gradually stabilized (Liu et al., 2016; Xiong et al., 2018; Le and Tang, 2023). The rapid sea-level rise expanded the coastal accommodation space, submerging previously exposed coastlines and establishing new depositional areas, thereby significantly increasing sediment load (Zhang et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2024). In this work, the developmental period of the CP reef coincided with the highstand phase in the South China Sea. Data from four boreholes indicates a gradual increase in sedimentation rates from 0.35 to 6.91 mm/yr (Figure 6), supporting the notion that sediment load intensified during this period. Notably, as the rate of sea-level rise decelerated, the sedimentation rate surpassed the rate of sea-level change (Figures 7-10). For instance, in Well WC-02, the sedimentation rate exceeded 6 mm/yr during 6,000-5,500 cal yr BP, while the sea-level change rate was only 0-2 mm/yr at that time (Figure 8). This quantitative comparison suggests that terrigenous sediment supply emerged as the key factor in reef development.

This case challenges conventional models by demonstrating that chronic terrigenous input can override both reef architectural trajectories and ecological succession patterns in nearshore turbid reef systems. Typically, turbid-water reefs transition from an initial phase of vertical accretion to lateral expansion, constrained by the available accommodation space (Morgan et al., 2020; Bonesso et al., 2023). In contrast, despite adequate accommodation conditions, the CP reef displayed significant lateral progradation between 6,400 and 4,000 cal yr BP. This behavior was largely driven by the ongoing seaward accumulation of terrigenous clastic sediments. Second, longstanding paradigms suggest that coral reef accretion slows in terrigenous, mud-rich settings, which is believed to impair coral and reef growth by burying reef frameworks with mud deposition (e.g. Ryan et al., 2016a) or elevating nutrient-sediment loading (e.g. Sanborn et al., 2024). Contrary to this expectation, the study found that the CP reef experienced much higher sedimentation rates, even under seemingly detrimental water quality conditions. This increase coincided with rapid vertical reef accretion on a shore-detached turbid-zone reef at Offshore Paluma Shoals (Perry et al., 2013). Finally, from the perspective of biological adaptation, during the turbid phase (ca 6,400-5,500 cal yr BP), coral assemblages of the CP reef significantly decreased without a distinct dominance of specific species. The observation contrasts with established paradigms of selective adaptation under high sedimentation, where taxa such as fast-growing Acropora spp. or low-light-adapted Porites spp. are typically favored (Morgan et al., 2020; Gischler et al., 2023; Sanborn et al., 2024).

Current evidence suggests that chronic terrigenous sediment loading, when it exceeds ecological thresholds, may lead to the collapse of reef ecosystems (e.g. Sanders and Baron-Szabo, 2005). However, systems with sufficient accommodation space and subthreshold nutrient levels may be able to maintain carbonate budgets over millennial timescales (Johnson et al., 2017; Bonesso et al., 2023; Kappelmann et al., 2024), even if they could experience some biodiversity losses on a centennial scale (Guest et al., 2016; Luter et al., 2021). Modern anthropogenic pressures have become a major driver of increased sedimentation and nutrient loading in nearshore and estuarine areas (Portugal et al., 2016; Soares et al., 2021). This could accelerate sediment-nutrient fluxes, potentially driving nearshore reefs beyond tipping points within decades instead of millennia (Soares et al., 2021; Liu and Yu, 2022; Gischler et al., 2023). As a result, effective protection of nearshore coral reef systems requires regulating coastal exploitation and managing agricultural runoff to reduce nutrient and sediment pressures on the nearshore reef ecosystem.

6 Conclusions

This study investigates the initiation, internal structure and depositional evolution of a fringing reef system in Changpi (CP) region, located on the eastern coast of Hainan Island, China. Radiocarbon dating (AMS 14C) indicates that reef initiation occurred at approximately 7,400 cal yr BP, with the latest coral reef deposition dating to after 4,000 cal yr BP. The identified lithofacies types are characterized by a terrigenous clastic-coral framework, revealing that the CP reef experienced varying degrees of siliciclastic input over 3,000 years during the mid-Holocene. Systematic sediment analysis and radiometric dating of core sequence identified three stages of reef development. The initial stage (7,400-6,400 cal yr BP) is marked by well-preserved coral deposits and relatively low accretion rates (ca 0.35 mm/yr). During this period, a high-energy hydrodynamic regime combined with clear-water conditions facilitated growth of coral assemblage. Between 6,400 and 5,500 cal yr BP, rapid deposition of terrigenous clasts created a “turbid water” environment, resulting in accelerated accretion rates (up to 6.39 mm/yr) and significant fluctuations in sediment composition. Coral species diversity is significantly reduced under the conditions. In the final stage (5,500-4,000 cal yr BP), a reduced rate of terrigenous input (ca 2.70 mm/yr) re-established clear-water conditions. The reduction in sediment pressure enabled Acropora spp. to emerge as the dominant coral species, thereby fostering a resurgence in coral growth.

The model of reef development established in this study reveals that since approximately 6,400 cal yr BP, the sedimentation rate has gradually increased and surpassed the rate of sea-level rise. Rapid terrigenous sediment accumulation has increased vertical sediment rate and has driven the reef system to shift from vertical accretion to lateral migration. Coral growth was significantly dependent on the control of terrigenous sediment influx on water quality conditions. These observations indicate that terrigenous influx can dictate the developmental trajectories of turbid coral reef more profound than sea‐level changes. The scientific significance of the work lies in its contribution to rethinking the mechanisms by which turbid-water reefs maintain stable carbonate deposition and resilient ecosystems, thereby offering critical insights for the management of nearshore reef systems. As suggested by our findings, effective protection necessitates stringent regulation of coastal exploitation and the management of agricultural runoff to mitigate nutrient and sediment pressures on reef ecosystems.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LS: Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. RS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources. WL: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation. QP: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. HX: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was jointly supported by the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 424RC539) and the Major Science and Technology Plan Project of Yazhou Bay Innovation Research Institute of Hainan Tropical Ocean University (2022CXYZD003).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Associate Professor Zhongjie Wu and Yuanchao Li for their invaluable technical support and insightful feedback throughout the project. Additionally, we sincerely appreciate the valuable suggestions provided by the two reviewers. Their constructive comments have significantly enhanced the overall quality of the manuscript. The authors declare no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Barnes M. L. Mbaru E. Muthiga N. (2019). Information access and knowledge exchange in co-managed coral reef fisheries. Biol. Conserv.238, 108198. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108198

2

Bonesso J. L. Browne N. K. Murley M. Dee S. Cuttler M. V. W. Paumard V. et al . (2022). Reef to island sediment connections within an inshore turbid reef island system of the eastern Indian Ocean. Sediment. Geol.436, 106177. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2022.106177

3

Bonesso J. L. Cuttler M. V. W. Browne N. K. Mather C. C. Paumard V. Hiscock W. T. et al . (2023). Reef island evolution in a turbid-water coral reef province of the Indo-Pacific. Depos. Rec.9, 921–934. doi: 10.1002/dep2.242

4

Bradley S. L. Milne G. A. Horton B. P. Zong Y. (2016). Modelling sea level data from China and Malay-Thailand to estimate Holocene ice-volume equivalent sea level change. Quat. Sci. Rev.137, 54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.02.002

5

Browne N. K. (2012). Spatial and temporal variations in coral growth on an inshore turbid reef subjected to multiple disturbances. Mar. Environ. Res.77, 71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2012.02.005

6

Browne N. K. Smithers S. G. Perry C. T. Browne N. K. (2012). Coral reefs of the turbid inner-shelf of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia: An environmental and geomorphic perspective on their occurrence, composition and growth. Earth-Sci. Rev.115, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.06.006

7

Browne N. K. Smithers S. G. Perry C. T. (2013). Carbonate and terrigenous sediment budgets for two inshore turbid reefs on the central Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Geol.346, 101–123. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2013.08.011

8

Cai Z. F. Chen S. Q. Wu Z. J. Tong Y. H. Huang J. Y. Zhang G. X. et al . (2015). Spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of reef-building corals along the northeastern coast of Hainan Island. Trans. Oceanol. Limnol.3, 78–86. doi: 10.13984/j.cnki.cn37-1141.2015.03.010

9

Chen T. R. Li S. Zhao J. X. Feng Y. X. (2021a). Uranium-thorium dating of coral mortality and community shift in a highly disturbed inshore reef (Weizhou Island, northern South China Sea). Sci. Total Environ.752, 141866. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141866

10

Chen Y. Y. Deng B. Chen Y. F. Wang D. R. Zhang J. (2021b). Holocene sedimentary evolution of a subaqueous delta off a typical tropical river, Hainan Island, South China. Mar. Geol.442, 106664. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2021.106664

11

Clift P. D. Wan S. M. Blusztajn J. (2014). Reconstructing chemical weathering, physical erosion and monsoon intensity since 25Ma in the northern South China Sea: A review of competing proxies. Earth-Sci. Rev.130, 86–102. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.01.002

12

Dechnik B. Bastos A. C. Vieira L. S. Webster J. M. Fallon S. Yokoyama Y. et al . (2019). Holocene reef growth in the tropical southwestern Atlantic: Evidence for sea level and climate instability. Quat. Sci. Rev.218, 365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.06.039

13

Dechnik B. Bastos A. C. Vieira L. S. Webster J. M. Fallon S. Yokoyama Y. et al . (2021). Environmental controls on holocene reef development along the eastern Brazilian margin. Coral Reefs40, 1321–1337. doi: 10.1007/s00338-021-02130-w

14

Dullo W. C. (2005). Coral growth and reef growth: a brief review. Facies51, 33–48. doi: 10.1007/s10347-005-0060-y

15

Dunham R. J. (1962). “Classification of carbonate rocks according to depositional texture,” in Classification of Carbonate Rocks. Ed. HamW. E. (Tulsa: Memoir of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists), 108–121.

16

Ellis J. I. Jamil T. Anlauf H. Coker D. J. Curdia J. Hewitt J. et al . (2019). Multiple stressor effects on coral reef ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol.25, 4131–4146. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14819

17

Embry A. F. Klovan J. E. (1971). A Late Devonian reef tract on northeastern Banks Island, Northwest Territories. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol.19, 730–781. doi: 10.35767/gscpgbull.19.4.730

18

Fabricius K. E. (2005). Effects of terrestrial runoff on the ecology of corals and coral reefs: review and synthesis. Mar. pollut. Bull.50, 125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.11.028

19

Fisher R. Bessell-Browne P. Jones R. (2019). Synergistic and antagonistic impacts of suspended sediments and thermal stress on corals. Nat. Commun.10, 2346. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10288-9

20

Gao S. Zhou L. Li G. C. Wang D. Yang Y. Dai C. et al . (2016). Processes and sedimentary records for Holocene coastal environmental changes, Hainan Island: an overview. Quat. Sci.36, 1–17. doi: 10.11928/j.issn.1001-7410.2016.01

21

Gischler E. Hudson J. H. Eisenhauer A. Parang S. Deveaux M. (2023). 9000 years of change in coral community structure and accretion in Belize reefs, western Atlantic. Sci. Rep.13, 11349. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-38118-5

22

Gischler E. Hudson J. H. Humblet M. Braga J. C. Schmitt D. Isaack A. et al . (2019). Holocene and Pleistocene fringing reef growth and the role of accommodation space and exposure to waves and currents (Bora Bora, Society Islands, French Polynesia). Sedimentology66, 305–328. doi: 10.1111/sed.12533

23

Groh A. Harff J. (2023). Relative sea-level changes induced by glacial isostatic adjustment and sediment loads in the Beibu Gulf, South China Sea. Oceanologia65, 249–259. doi: 10.1038/srep36260

24

Guest J. R. Tun K. Low J. Vergés A. Marzinelli E. M. Campbell A. H. (2016). 27 years of benthic and coral community dynamics on turbid, highly urbanised reefs off Singapore. Sci. Rep.6, 36260. doi: 10.1038/srep36260

25

Hu B. Q. Li J. Cui R. Y. Wei H. L. Zhao J. T. Li G. G. et al . (2014). Clay mineralogy of the riverine sediments of Hainan Island, South China Sea: Implications for weathering and provenance. J. Asian Earth Sci.96, 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2014.08.036

26

Hughes T. P. Huang H. Young M. A. L. (2013). The wicked problem of China’s disappearing coral reefs: China’s disappearing coral reefs. Conserv. Biol.27, 261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01957.x

27

Ingersoll R. V. Bullard T. F. Ford R. L. Grimm J. P. Pickle J. D. Sares S. W. (1984). The effect of grain size on detrital modes: A test of the Gazzi-Dickinson point-counting method. J. Sediment. Petrol.54, 103–116. doi: 10.1306/212F83B9-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D

28

Johnson J. A. Perry C. T. Smithers S. G. Morgan K. M. Santodomingo N. Johnson K. G. (2017). Palaeoecological records of coral community development on a turbid, nearshore reef complex: baselines for assessing ecological change. Coral Reefs36, 685–700. doi: 10.1007/s00338-017-1561-1

29

Johnson J. A. Perry C. T. Smithers S. G. Morgan K. M. Woodroffe S. A. (2019). Reef shallowing is a critical control on benthic foraminiferal assemblage composition on nearshore turbid coral reefs. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.533, 109240. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109240

30

Kappelmann Y. Sengupta M. Mann T. Stuhr M. Kneer D. Jompa J. et al . (2024). Island accretion within a degraded reef ecosystem suggests adaptability to ecological transitions. Sediment. Geol.468, 106675. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2024.106675

31

Knowlton N. Jackson J. B. C. (2008). Shifting baselines, local impacts, and global change on coral reefs. PloS Biol.6, e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060054

32

Le Y. F. Tang L. C. (2023). Characteristics of sea level changes in the northern South China Sea since the Holocene and prediction of the future trends. Mar. Geol. Front.39, 1–16. doi: 10.16028/j.1009-2722.2022.193

33

Leonard N. D. Lepore M. L. Zhao J. Rodriguez-Ramirez A. Butler I. R. Clark T. R. et al . (2020). Re-evaluating mid-Holocene reef “turn-off” on the inshore Southern Great Barrier Reef. Quat. Sci. Rev.244, 106518. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106518

34

Lewis S. E. Sloss C. R. Murray-Wallace C. V. Woodroffe C. D. Smithers S. G. (2013). Post-glacial sea-level changes around the Australian margin: a review. Quat. Sci. Rev.74, 115–138. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.09.006

35

Lewis S. E. Wüst R. A. J. Webster J. M. Shields G. A. Renema W. Lough J. M. et al . (2012). Development of an inshore fringing coral reef using textural, compositional and stratigraphic data from Magnetic Island, Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Mar. Geol.299–302, 18–32. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2012.01.003

36

Li J. Ashton A. D. Wang Y. P. Xu X. Gao S. (2024). Sediment dynamics on a subtidal reef flat of an atoll in the South China Sea. Mar. Geol.473, 107310. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2024.107310

37

Li Y. Li Y. Chen M. Xue Y. Zhang J. Wang L. et al . (2025). Sediment flux variation and environmental implications in the East Hainan Coast, South China Sea during the last 20 ka—a luminescence chronological investigation. Mar. Geol.480, 107453. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2024.107453

38

Li X. B. Wang D. R. Huang H. Zhang J. Lian J. S. Yuan X. C. et al . (2015). Linking benthic community structure to terrestrial runoff and upwelling in the coral reefs of northeastern Hainan Island. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.156, 92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2014.09.021

39

Lin Y. C. Whitehouse P. L. Hibbert F. D. Woodroffe S. A. Hinestrosa G. Webster J. M. (2023). Relative sea level response to mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sediment loading along the Great Barrier Reef margin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.607, 118066. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118066

40

Liu J. Xiang R. Kao S.-J. Fu S. Zhou L. (2016). Sedimentary responses to sea-level rise and Kuroshio Current intrusion since the Last Glacial Maximum: Grain size and clay mineral evidence from the northern South China Sea slope. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.450, 111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.002

41

Liu X. Yu S. (2022). Anthropogenic metal loads in nearshore sediment along the coast of China mainland interacting with provincial socioeconomics in the period 1980–2020. Sci. Total Environ.839, 156286. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156286

42

Luter H. M. Pineda M.-C. Ricardo G. Francis D. S. Fisher R. Jones R. (2021). Assessing the risk of light reduction from natural sediment resuspension events and dredging activities in an inshore turbid reef environment. Mar. pollut. Bull.170, 112536. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112536

43

Ma Y. F. Qin Y. M. Yu K. F. Li Y. Q. Long Y. T. Wang R. et al . (2021). Holocene coral reef development in Chenhang Island, Northern South China Sea, and its record of sea level changes. Mar. Geol.440, 106593. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2021.106593

44

Meng M. Yu K. Hallock P. Qin G. Jiang W. Fan T. (2022). Foraminifera indicate Neogene evolution of Yongle Atoll from Xisha Islands in the South China Sea. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.602, 111163. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.111163

45

Morgan K. M. Perry C. T. Arthur R. Williams H. T. P. Smithers S. G. (2020). Projections of coral cover and habitat change on turbid reefs under future sea-level rise. Proc. R. Soc B.287, 20200541. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.0541

46

Morgan K. M. Perry C. T. Smithers S. G. Johnson J. A. Daniell J. J. (2016). Evidence of extensive reef development and high coral cover in nearshore environments: implications for understanding coral adaptation in turbid settings. Sci. Rep.6, 29616. doi: 10.1038/srep29616

47

Palmer S. E. Perry C. T. Smithers S. G. Gulliver P. (2010). Internal structure and accretionary history of a nearshore, turbid-zone coral reef: Paluma Shoals, central Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Mar. Geol.276, 14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2010.07.002

48

Parker J. H. Gischler E. (2011). Modern foraminiferal distribution and diversity in two atolls from the Maldives, Indian Ocean. Mar. Micropaleontol.78, 30–49. doi: 10.1016/j.marmicro.2010.09.007

49

Perry C. T. Smithers S. G. Gulliver P. (2013). Rapid vertical accretion on a ‘young’ shore-detached turbid zone reef: Offshore Paluma Shoals, central Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Coral Reefs32, 1143–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00338-013-1063-8

50

Perry C. T. Smithers S. G. Roche R. C. Wassenburg J. (2011). Recurrent patterns of coral community and sediment facies development through successive phases of Holocene inner-shelf reef growth and decline. Mar. Geol.289, 60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2011.09.012

51

Portugal A. B. Carvalho F. L. de Macedo Carneiro P. B. Rossi S. de Oliveira Soares M. (2016). Increased anthropogenic pressure decreases species richness in tropical intertidal reefs. Mar. Environ. Res.120, 44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2016.07.005

52

Qiu S. J. (1985). Coral reef coastal landforms of Hainan Island. Trop. Landform6, 1–24.

53

Quan S. Q. Wang G. Z. Lv B. Q. Jiang P. L. (1993). Modern sedimentary system and their evolutionary process in the PaiPu coral reef area, Hainan Island. Acta Sedim. Sin.11, 56–66.

54

Ramsey C. B. (2009). Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon51, 337–360. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200033865

55

Reimer P. J. Austin W. E. N. Bard E. Bayliss A. Blackwell P. G. Ramsey B. C. et al . (2020). The IntCal20 northern hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon62, 1–33. doi: 10.1017/RDC.2020.41

56

Roche R. C. Perry C. T. Johnson K. G. Sultana K. Smithers S. G. Thompson A. A. (2011). Mid-Holocene coral community data as baselines for understanding contemporary reef ecological states. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.299, 159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.10.043

57

Roder C. Wu Z. J. Richter C. Zhang J. (2013). Coral reef degradation and metabolic performance of the scleractinian coral Porites lutea under anthropogenic impact along the NE coast of Hainan Island, South China Sea. Cont. Shelf Res.57, 123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2012.11.017

58

Rodgers K. S. Richards Donà A. Stender Y. O. Tsang A. O. Han J. H. J. Weible R. M. et al . (2021). Rebounds, regresses, and recovery: A 15-year study of the coral reef community at Pila’a, Kaua’i after decades of natural and anthropogenic stress events. Mar. pollut. Bull.171, 112306. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112306

59

Rodriguez-Ruano V. Toth L. T. Enochs I. C. Randall C. J. Aronson R. B. (2023). Upwelling, climate change, and the shifting geography of coral reef development. Sci. Rep.13, 1770. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-28489-0

60

Rogers C. (1990). Responses of coral reefs and reef organisms to sedimentation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.62, 185–202. doi: 10.3354/meps062185

61

Ryan E. J. Smithers S. G. Lewis S. E. Clark T. R. Zhao J. X. (2016a). Chronostratigraphy of Bramston Reef reveals a long-term record of fringing reef growth under muddy conditions in the central Great Barrier Reef. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecol.441, 734–747. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.10.016

62

Ryan E. J. Smithers S. G. Lewis S. E. Clark T. R. Zhao J. X. (2016b). The influence of sea level and cyclones on Holocene reef flat development: Middle Island, central Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs35, 805–818. doi: 10.1007/s00338-016-1453-9

63

Ryan E. J. Smithers S. G. Lewis S. E. Clark T. R. Zhao J. X. Hua Q. (2018). Fringing reef growth over a shallow last interglacial reef foundation at a mid-shelf high island: Holbourne Island, central Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Geol.398, 137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2017.12.007

64

Sanborn K. L. Webster J. M. Erler D. Webb G. E. Salas-Saavedra M. Yokoyama Y. (2024). The impact of elevated nutrients on the Holocene evolution of the Great Barrier Reef. Quat. Sci. Rev.332, 108636. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.108636

65

Sanborn K. L. Webster J. M. Webb G. E. Braga J. C. Humblet M. Nothdurft L. et al . (2020). A new model of Holocene reef initiation and growth in response to sea-level rise on the Southern Great Barrier Reef. Sediment. Geol.397, 105556. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2019.105556

66

Sanders D. Baron-Szabo R. C. (2005). Scleractinian assemblages under sediment input: their characteristics and relation to the nutrient input concept. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecol.216, 139–181. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.10.008

67

Shao C. Qi H. S. Cai F. Chen S. L. (2016). Study on storm effects on beach–coral reef system—Taking the response of Qinglangangang coast of typhoon No. 1409 as an example. Haiyang Xuebao38, 121–130. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2016.02.012

68

Smithers S. Larcombe P. (2003). Late Holocene initiation and growth of a nearshore turbid-zone coral reef: Paluma Shoals, central Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Coral Reefs22, 499–505. doi: 10.1007/s00338-003-0344-z

69

Soares M.O. (2020). Marginal reef paradox: A possible refuge from environmental changes? Ocean Coast. Manage.185, 105063. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.105063

70

Soares M. O. Rossi S. Gurgel A. R. Lucas C. C. Tavares T. C. L. Diniz B. et al . (2021). Impacts of a changing environment on marginal coral reefs in the Tropical Southwestern Atlantic. Ocean Coast. Manage.210, 105692. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105692

71

Sofonia J. J. Anthony K. R. N. (2008). High-sediment tolerance in the reef coral Turbinaria mesenterina from the inner Great Barrier Reef lagoon (Australia). Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.78, 748–752. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2008.02.025

72

Solihuddin T. Collins L. B. Blakeway D. O’ Leary M. J. (2015). Holocene coral reef growth and sea level in a macrotidal, high turbidity setting: Cockatoo Island, Kimberley Bioregion, northwest Australia. Mar. Geol.359, 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2014.11.011

73

Solihuddin T. O’Leary M. J. Blakeway D. Parnum I. Kordi M. Collins L. B. (2016). Holocene reef evolution in a macrotidal setting: Buccaneer Archipelago, Kimberley Bioregion, Northwest Australia. Coral Reefs35, 783–794. doi: 10.1007/s00338-016-1424-1

74

Southon J. Kashgarian M. Fontugne M. Metivier B. Yim W. W.-S. (2002). Marine reservoir corrections for the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia. Radiocarbon44, 167–180. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200064778

75

Twiggs E. J. Collins L. B. (2010). Development and demise of a fringing coral reef during Holocene environmental change, eastern Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Mar. Geol.275, 20–36. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2010.04.004

76

Udden J. A. (1914). Mechanical composition of clastic sediments. Bull. Geol. Soc Am.25, 655–744. doi: 10.1130/GSAB-25-655

77

Voss J. D. Richardson L. L. (2006). Nutrient enrichment enhances black band disease progression in corals. Coral Reefs25, 569–576. doi: 10.1007/s00338-006-0131-8

78

Wang B. C. Chen S. L. Gong W. P. Lin W. Q. Xu Y. (2006). Formation and evolution of embayment coast of Hainan Island (Beijing: China Ocean Press).

79

Wang Y. Shen J. W. Long J. P. (2011). Ecological-sedimentary zonations and carbonate deposition, Xiaodonghai Reef Flat, Sanya, Hainan Island, China. Sci. China Earth Sci.54, 359–371. doi: 10.1007/s11430-011-4174-5

80

Weber M. De Beer D. Lott C. Polerecky L. Kohls K. Abed R. M. M. et al . (2012). Mechanisms of damage to corals exposed to sedimentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.109, E1558–E1567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100715109

81

Wells J. W. (1956). “Scleractinia,” in Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Ed. MooreR. C. (Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press, New York), 328–444. Part F, Coelenterata.

82

Wentworth C. K. (1922). A scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. J. Geol.30, 377–392. doi: 10.1086/622910

83

Wilson B. Blake S. Ryan D. Hacker J. (2011). Reconnaissance of species-rich coral reefs in a muddy, macro-tidal, enclosed embayment, Talbot Bay, Kimberley, Western Australia. J. R. Soc West. Aust.94, 251–265.

84

Wittenberg M. Hunte W. (1992). Effects of eutrophication and sedimentation on juvenile corals: I. Abundance, mortality and community structure. Mar. Biol.112, 131–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00349736

85

Woodhead A. J. Hicks C. C. Norström A. V. Williams G. J. Graham N. A. J. (2019). Coral reef ecosystem services in the Anthropocene. Funct. Ecol.33, 1023–1034. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13331

86