Abstract

The reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi) is a threatened filter-feeding elasmobranch that requires immediate management and protection across large parts of its range. Despite being well-studied, a detailed understanding of their feeding ecology, which shapes their residency, movement patterns, and behaviour, remains underexplored. Both global and site-specific research is required to fill significant knowledge gaps essential for designing effective conservation strategies for this species and their habitats. This study investigated M. alfredi feeding behaviour in relation to plankton biomass dynamics at D’Arros Island in the Seychelles, the largest known M. alfredi aggregation site in the country and a gazetted marine protected area. Plankton samples were collected, along with corresponding environmental data, during M. alfredi feeding and non-feeding behaviour. Statistical modelling revealed that surface feeding occurred predominantly during periods of higher plankton biomass, with a critical prey density threshold of 26.9 mg/m³, which had a significant relationship with tidal phase. Additionally, there were no significant differences in feeding behaviour and plankton biomass across seasons, which demonstrates the year-round value of D’Arros Island to this species. These findings provide new insights into the feeding ecology of M. alfredi in the Seychelles and support future conservation and management initiatives for this threatened species.

1 Introduction

Reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) are filter feeders that utilise their specialised cephalic lobes to funnel water into their mouths, primarily consuming pelagic and demersal zooplankton (Dewar et al., 2008; Last and Stevens, 2009; Couturier et al., 2012; Couturier et al., 2013; Peel et al., 2019a; Harris et al., 2023). Their foraging behaviour is closely associated with dense zooplankton aggregations (Armstrong et al., 2016; Armstrong et al., 2021), which are necessary to meet the energetic demands of this large species with its high metabolic rate (Meekan et al., 2015). To optimise feeding efficiency and balance energy expenditure, M. alfredi often target zooplankton blooms where prey densities surpass a critical threshold. These events are ephemeral and influenced by dynamic environmental processes (Couturier et al., 2011; Weeks et al., 2015; Armstrong et al., 2016; Armstrong et al., 2021).

Although research on M. alfredi has advanced the understanding of their feeding ecology (Couturier et al., 2013; Peel et al., 2019a; Harris et al., 2023), the dynamics of zooplankton availability, an important factor influencing the residency, movement, and foraging behaviour of manta rays, are not fully understood (Armstrong et al., 2021). A significant gap still exists in understanding their feeding ecology, including dietary composition, spatial and temporal patterns in feeding and the environmental conditions that drive aggregations. This knowledge is essential for designing effective conservation regulations for this threatened species and its habitats. Since this species has a wide circumglobally distribution (Marshall et al., 2022), further investigations across a broader range of locations, habitat types, and environmental conditions would enhance knowledge of its feeding ecology and support the development of targeted conservation strategies. Research conducted at Lady Elliot Island in Australia (Armstrong et al., 2016) and Hanifaru Bay in the Maldives (Armstrong et al., 2021) revealed that although M. alfredi tended to feed in areas with high zooplankton densities, however, zooplankton accumulation varied under different conditions at the two locations. In Australia, zooplankton densities were higher around the low tide, while in the Maldives, they peaked around high tide. The prey density threshold (PDT), a level beyond which the probability of feeding increases significantly, was identified as 11.2 mg/m³ in Australia and 53.7 mg/m³ in the Maldives. Analysis of the zooplankton composition in Australia showed that neither size nor species composition affected feeding behaviour, highlighting zooplankton accumulation as the primary factor influencing feeding behaviour rather than composition. However, in the Maldives, composition significantly influenced feeding behaviour, with M. alfredi showing a preference for calanoid copepods over gelatinous taxa such as chaetognaths or eggs (Armstrong et al., 2016; Armstrong et al., 2021). These variations could be attributable to differences in habitats across geographically distinct locations, driving scientific interest in various sites and habitat types.

D’Arros Island is utilised by M. alfredi year-round and hosts the largest known aggregation in the Seychelles. In contrast, the species is less frequently observed around other islands throughout the region (Peel et al., 2019a; Peel et al., 2019b; Peel et al., 2024). In 2023, the surrounding waters of D’Arros Island were officially gazetted as a Marine Protected Area (MPA) with the highest level of protection (Zone 1 – Marine National Park under the Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan Initiative (Official Gazette No 34 – Ministry of Agriculture, Climate Change and Environment, 2020)), encompassing the known foraging grounds located close to the island. Before finalising the site-specific management plan, science-based research is required to inform appropriate regulations for the effective management of both the species and its habitat. Understanding factors such as preferred feeding areas and the conditions that drive M. alfredi aggregations can help identify key feeding sites and guide regulations for recreational and commercial motorised activities. This study contributes to ongoing efforts and strengthens the existing knowledge of M. alfredi feeding ecology.

This study aimed to understand the relationship between plankton biomass and feeding behaviour of M. alfredi to provide insights into the key environmental drivers that influence its foraging activities. This knowledge will aid in optimizing research and conservation efforts. Quantifying the PDT for M. alfredi at this site provides valuable information in understanding the critical point at which plankton biomass levels start influencing feeding behaviour. By comparing this threshold to the only two others that have been calculated for M. alfredi in Australia (Armstrong et al., 2016) and the Maldives (Armstrong et al., 2021), regional differences and similarities in feeding behaviour, prey and habitat requirements can be assessed. Such comparisons are crucial for contextualizing study findings. Lastly, although M. alfredi are present year-round, observations of seasonal peaks in their abundance between July and December suggests potential seasonal variations (SOSF-DRC unpublished data). To explore this further, it is important to investigate whether these peaks in M. alfredi abundance are correlated with variations in prey availability. This approach will help to identify patterns of prey availability like those observed in the Maldives, where a more pronounced seasonality in both food supply and M. alfredi numbers has been documented (Harris et al., 2020). Understanding these seasonal dynamics will not only allow for more accurate predictions of M. alfredi visitations but also provide valuable insights into other life-history traits, such as reproduction and migratory patterns. Regarding its conservation value, this research will inform the development of rules and regulations for the D’Arros Island marine protected area, which are currently being drafted. Within the management plan, information acquired from this study on patterns in surface feeding of reef manta rays will directly influence the placement of speed restriction zones.

2 Methods

2.1 Study site

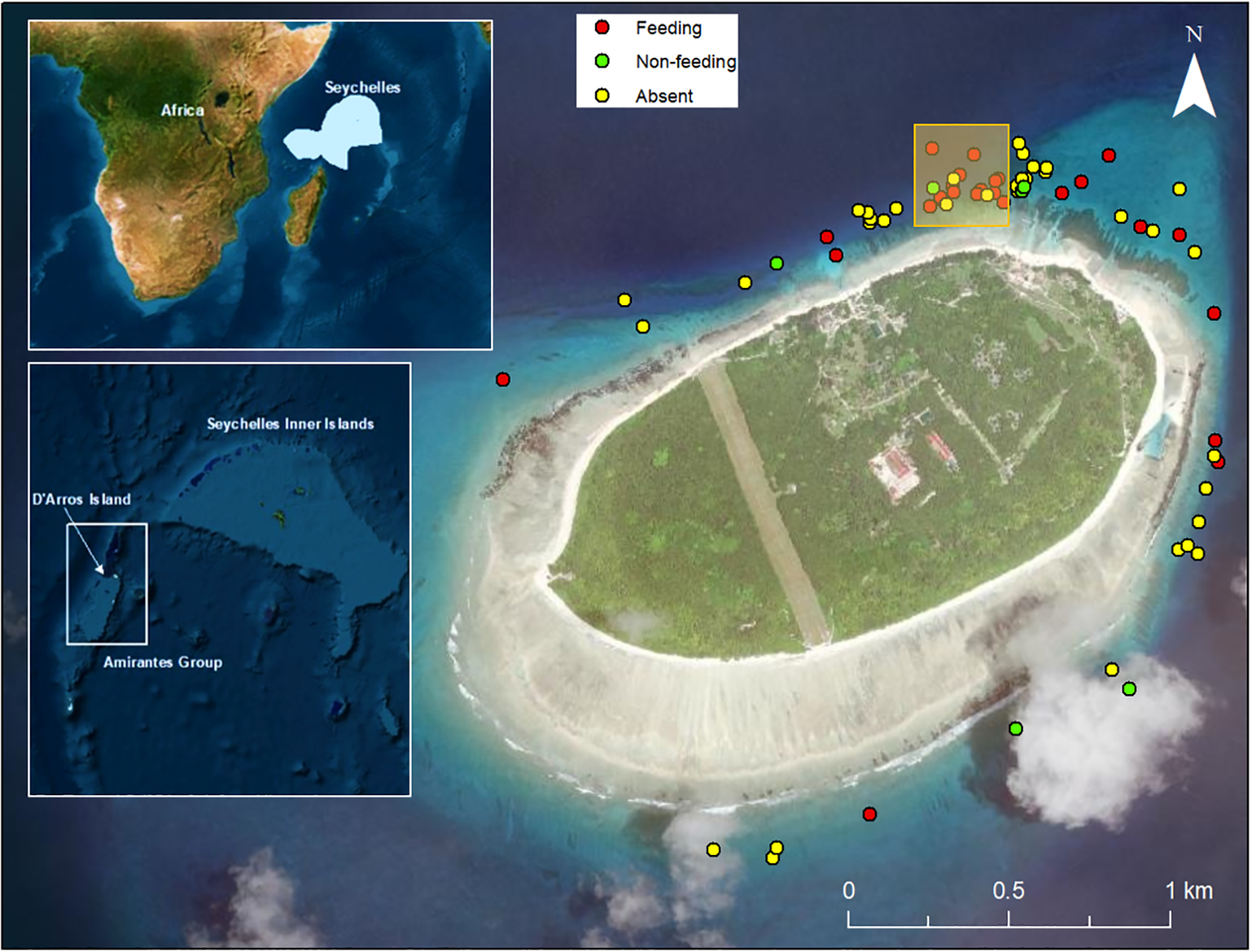

D’Arros Island (Figure 1), a coral sand cay covering 1.71 km2, is one of the 11 islands and sand cays within the Amirantes Group, in the Seychelles (5°24.9’S, 53°17.9’E). Its surrounding reefs are utilised by M. alfredi for feeding, cleaning, courtship, and cruising, with surface feeding being the most common behaviour observed (Peel et al., 2024). At this site nearly 300 individuals of M. alfredi have been first-sighted, accounting for 60% of all known individuals in Seychelles (SOSF-DRC unpublished data). Across the Seychelles, the climate is shaped by the western Indian Ocean monsoon system, comprising two components described as the North-west monsoon and South-east monsoon (Castillo-Trujillo et al., 2021). The wet north-west monsoon, characterized by lighter and less persistent north-westerly winds, occurs from November to April during the austral summer monsoon. In contrast, the dry south-east monsoon brings stronger and more consistent south-easterly winds from May to October (Schott and McCreary, 2001; Komdeur and Daan, 2005).

Figure 1

Satellite image of D’Arros Island showing sampling locations of plankton tows where M. alfredi were observed feeding and where they were non-feeding or absent. The yellow square indicates the area in which more than 50% of all feeding behaviour was recorded. Upper left inset highlights geographic reference and Seychelles Exclusive Economic Zone, EEZ (blue). Lower left inset highlights the position of D’Arros Island in the Amirantes Island group and relative to the Seychelles Inner Islands. Map base layer source: Esri ®.

2.2 Data collection

2.2.1 Manta survey

Mobula alfredi presence and feeding behaviour were recorded at the site through weekly surface-based boat (21’ powerboat) surveys for a one-year period from March 2023 to March 2024 (due to logistical constraints, sampling during January and February 2024 was not conducted). During surveys, the boat patrolled nearshore areas (usually < 300 m from shore, depth range 2–40 m) where M. alfredi is frequently seen, at steady speeds of 4–6 knots. The survey route constituted a single full lap of D’Arros Island in a counter-clockwise direction, covering ~ 6–8 km in distance and taking approximately 90–120 minutes to conduct, depending on the number of M. alfredi encountered. When an individual was sighted, the boat was stopped and a researcher entered the water to obtain images or video that allow for individual identification via the animal’s unique ventral spot patterns. Other information such as the time of observation, number of M. alfredi seen, behaviour (feeding or not feeding: e.g. cruising, cleaning) and sex were also recorded. Each individual was later identified using an image gallery with all known individuals in the Seychelles population, to confirm the exact number of M. alfredi present. If no M. alfredi were observed, their absence was noted in the records.

2.2.2 Plankton samples collection and environmental data

Plankton tows were conducted to collect plankton samples at the closest possible location to where M. alfredi were observed, after researchers had entered the water to collect animal identification. On occasions with no M. alfredi observed, samples were also collected from different areas around the island. Tows for each sample were taken over a 50 m distance, which was estimated by taking a GPS point then navigating 50 m from the point (against prevailing current or wind) using the GPS. A 200 μm mesh plankton net (General Oceanics Inc, FL, USA) with a 50 cm diameter mouth opening (a mouth diameter to length ratio of 4:1 and lightweight 200 μm mesh bag style cod-end) was used. A digital flowmeter (General Oceanics Inc, FL, USA) was fitted to the mouth opening, halfway between the net mouth centre and the rim. The flowmeter reading (Flow OUT - Flow IN) aided in calculating the tow distance (m), and hence the volume of water filtered during each tow (m3), which was used to calculate the biomass of plankton per water volume (mg/m3). The contents of the cod-end were transferred into the labelled 500 ml container and brought to the lab for processing. Time from sampling to lab storage was generally < 30 minutes and always less than two hours.

For each sample, a list of variables was logged. This included (1) wind speed (knots), (2) wind direction (compass directions) obtained from the website Windy.com (© 2016–2025 Windyty, S.E.), (3) tidal phase (hours from high tide) obtained from the Seychelles Maritime Safety Authority (SMSA) tide table, (4) fraction of the moon illuminated (%) obtained from the website United States Naval Observatory (USNO), and using a multiparameter probe (YSI 2030 Pro – Xylem Inc. Washington DC, USA) to record (5) water temperature (°C), (6) salinity (ppt) and (7) dissolved oxygen (mg/l).

2.2.3 Sample processing

For processing, each sample was split into two equal sub-samples using a Folsom splitter (Wildco). One sub-sample was filtered using a 200 μm sieve (Floplast) to remove all water, then dried using a standard food dehydrator at 70 °C for five hours to obtain the dry weight for calculating biomass. The other half was preserved in 4% buffered formaldehyde for further composition structure analysis.

2.3 Data analysis

Data were analysed in RStudio (R version 4.3.1). Generalised Linear Models (GLMs) were used to investigate the relationships between a variety of predictor variables with M. alfredi feeding behaviour and plankton biomass (each as an independent response variable). GLMs represent a flexible extension of linear regression modelling that are not required to meet the assumption for normally distributed response variables (McCullagh, 2019). For models with M. alfredi feeding behaviour as a response variable, a GLM with a binomial error structure and a logit link function was used, since M. alfredi feeding behaviour was binary, either feeding (=1) or non-feeding (=0). Feeding (=1) comprised of instances where at least one M. alfredi was present and actively feeding, whereas non-feeding (=0) comprised instances where M. alfredi was present but not feeding (e.g., cruising) or absent. Five predictor variables were included in the initial model, including season (North-west, South-east), moon phase (on a continuous scale from 0 during the New Moon to 1 at Full Moon), average wind (knots) (local records taken from the Windy App), tide (as hours from high tide) and plankton biomass (described above), as well as interactions between these variables. A binomial GLM was also used to estimate the PDT (feeding = 1, non-feeding = 0), in relation to plankton biomass. The critical density threshold was measured as the plankton biomass at which the proportion of M. alfredi feeding exceeded 0.5 (as in (Armstrong et al., 2016)). Models were also generated with plankton biomass as the response variable and with tidal phase, season, moon illuminance and average wind as predictors. Since plankton biomass is a continuous positive variable, these models were generated with a gaussian error distribution and identity link function. Collinearity of model variables was tested using variance inflation factor (VIF) within the ‘car’ package (Fox and Weisberg, 2018) in RStudio. Variables were sequentially removed based on the greatest VIF values until no variable had a VIF greater than three (Zuur et al., 2010). For each response variable, a suite of candidate models were then tested against respective null models utilizing a full subset approach with the glmulti package in R studio (Calcagno and de Mazancourt, 2010). The model with the greatest support was selected using Aikike Information Criterion, corrected for small sample sizes (AICc) and AICc evidence weights (Burnham and Anderson, 2004).

3 Results

A total of 89 plankton samples were collected (Feeding - 39, Non-feeding – 10 and Absent 40) from November 2022 to March 2024 encompassing both the North-west monsoon and South-east monsoon. Supplementary Table S1 shows the dates of sampling, number of mantas sampled on each date, their behaviour, and the plankton biomass recorded on that date.

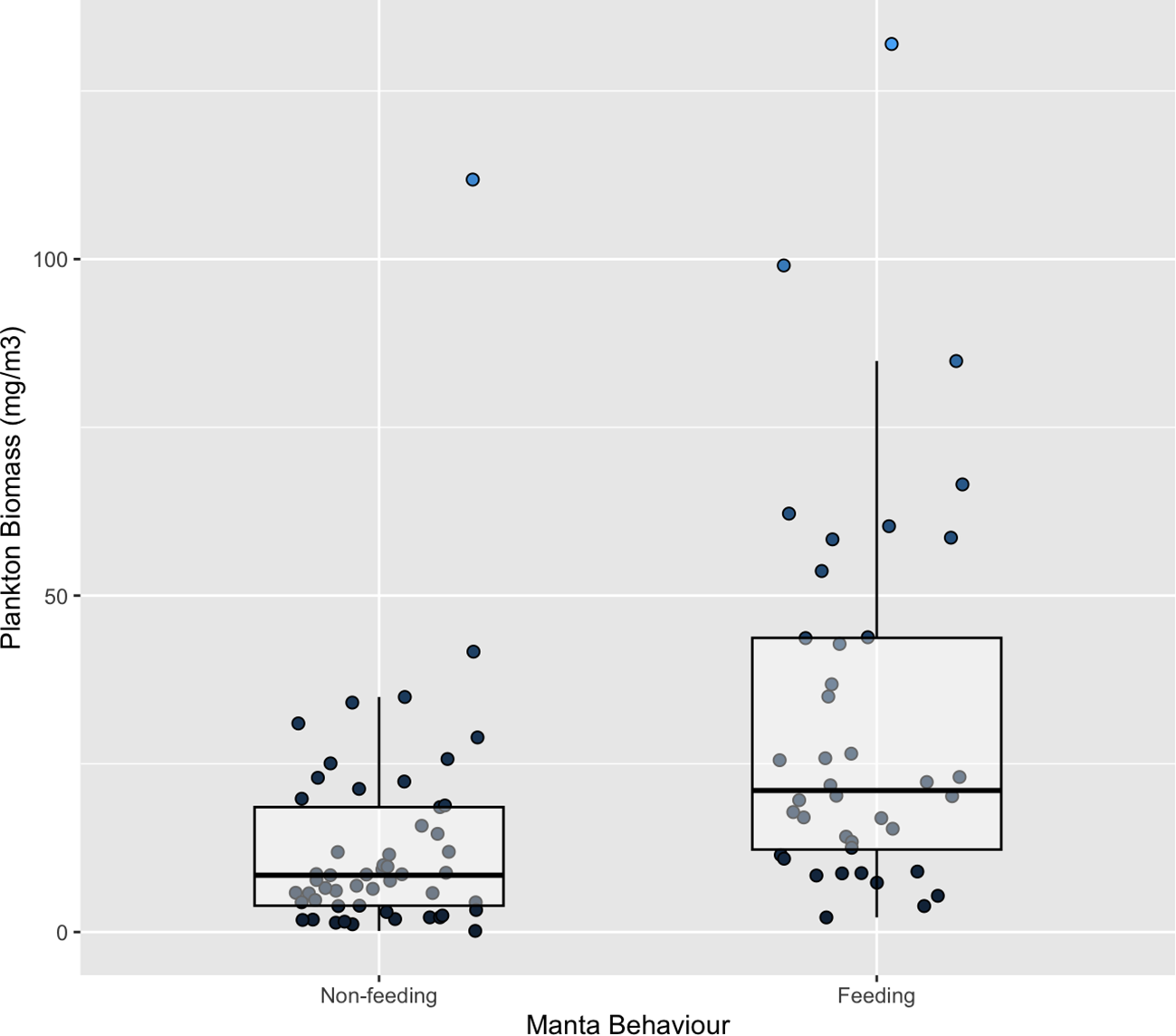

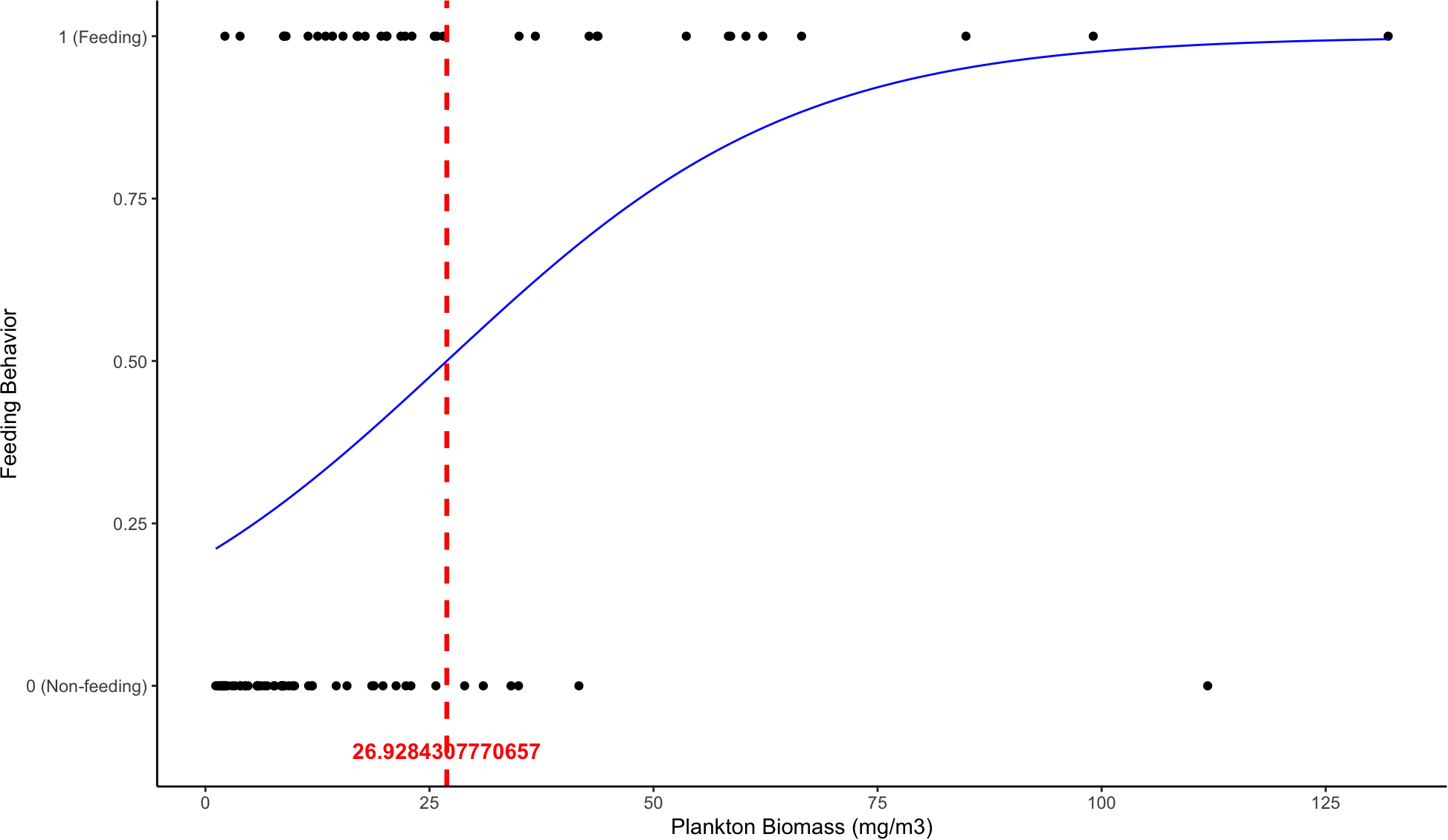

GLM for feeding behaviour showed that plankton biomass had a significant relationship with M. alfredi feeding behaviour, whereas all other variables did not (Table 1; Figure 2). Four models contributed to the top two AICc units and eight models contributed 95% evidence weight (see Supplementary Table S2). The model with the greatest support was that which included biomass, wind average and moon phase as predictors. A PDT of 26.9 mg/m³ was estimated (Figure 3), representing the minimum plankton density required for M. alfredi to feed efficiently. Plankton biomass exceeded this threshold value during surface feeding events compared to non-feeding instances, which did not (Figure 2). Mean biomass during feeding = 31.65 mg/m³ ± 4.48 SE whereas mean biomass when non-feeding =13.16 mg/m³ ± 2.35 SE.

Table 1

| Variable | Log odds ratio | Standard error | Odds ratio | LCI odds ratio | UCI odds ratio | P - value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plankton biomass | 0.03923 | 0.01625 | 1.04001 | 1.00741 | 1.073666 | 0.0158* |

| Wind average | -0.01106 | 0.06563 | 0.98899 | 0.86961698 | 1.1247710 | 0.8662 |

| Moon phase | 1.1499 | 0.7289 | 3.14242 | 0.75304314 | 13.1131758 | 0.1162 |

Coefficient estimates for predictor variables in the M. alfredi behaviour model (GLM), with estimates reported as log odds and odds ratios with upper and lower 95% confidence intervals (UCI, LCI). .

*significant result.

Figure 2

Relationship between plankton biomass (mg/m³) and M. alfredi behaviour (Feeding vs. Non-feeding).

Figure 3

Prey density threshold for M. alfredi around D’Arros Island. Logistic regression curve showing the relationship between M. alfredi feeding behaviour (1 = Feeding, 0 = Non-feeding) and plankton biomass (mg/m³). A generalized linear model (GLM) with a binomial error structure was used to estimate the critical prey density threshold, defined as the plankton biomass at which the probability of feeding exceeds 0.5 (dashed red line). The blue curve represents the fitted logistic regression model, indicating an increased likelihood of feeding behaviour with co-occurence of higher plankton biomass.

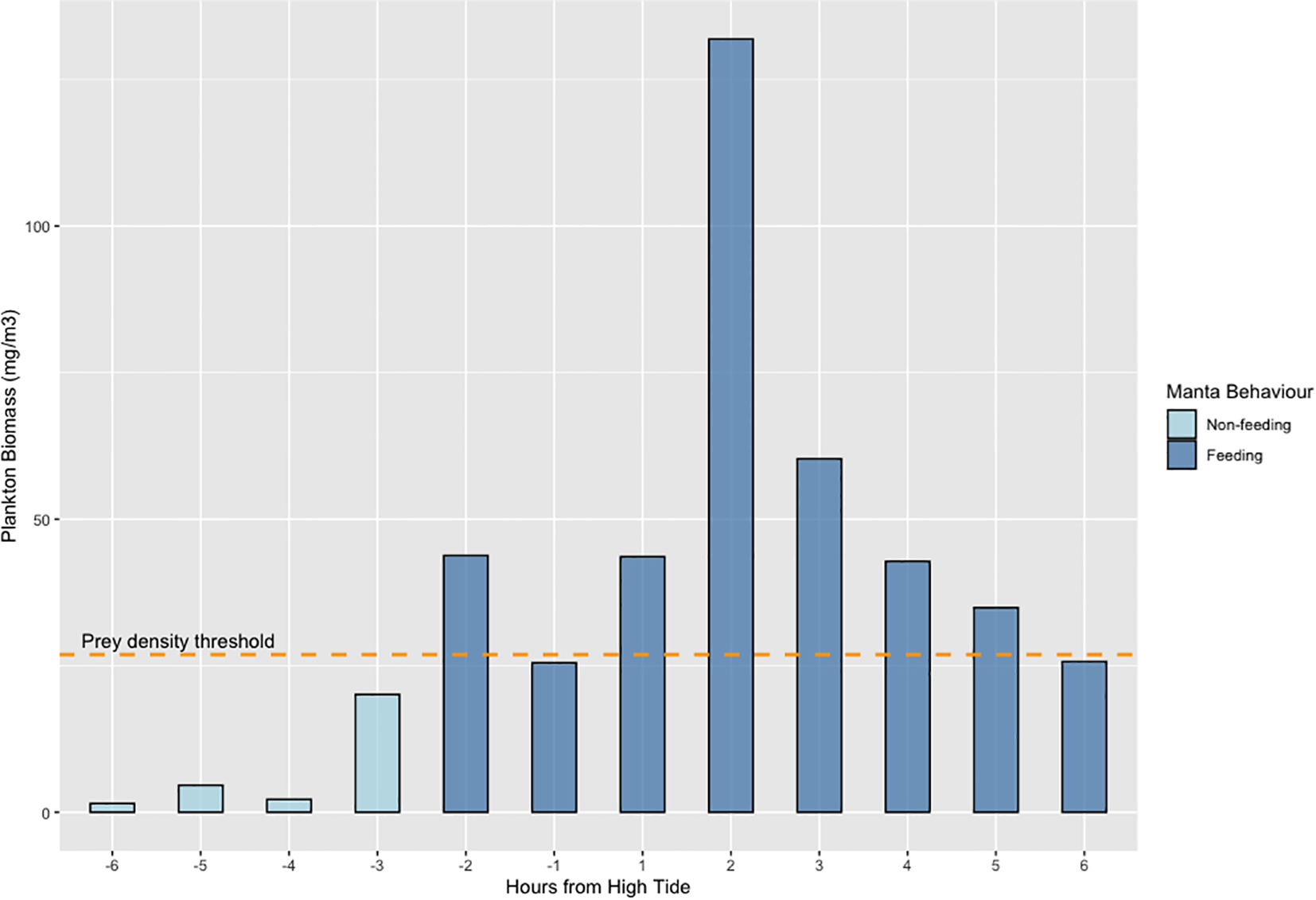

The GLM with plankton biomass as a response variable showed a significant relationship between plankton biomass and tide (Table 2). Two models contributed to the top two AICc units and four models contributed 95% evidence weight. The model with the greatest support was that which included wind average, moon and tide as predictors (see Supplementary Table S3). Feeding was mostly observed on the northeast side of the island with the exception of two observations further to the west and south (see Figure 1). M. alfredi are infrequently found on the southern and western side of D’Arros, resulting in the limited sampling in that area. Consequently, a significant proportion of sampling was conducted along the northeastern coast of D’Arros with > 50% of all feeding behaviour observed in a 300 m stretch along the northern coastline (highlighted with yellow box in Figure 1). Biomass data (max values) from this location were presented across the tidal cycle for visualisation (Figure 4). Plankton biomass surpassed the critical PDT for M. alfredi feeding described above in the time between two hours before to five hours after the high tide. Some samples were collected during these tidal windows without any M. alfredi observed feeding. Moreover, no M. alfredi feeding was observed outside of this part of the tidal cycle.

Table 2

| Variable | Log odds ratio | Standard error | Odds ratio | LCI odds ratio | UCI odds ratio | P - value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind average | 1.0305 | 0.5206 | 2.8024 | 1.010120e+00 | 7.774946e+00 | 0.05150 |

| Moon phase | 9.4088 | 6.3075 | 12195.28 | 5.215207e-02 | 2.851755e+09 | 0.14003 |

| Tide | 1.5874 | 0.5835 | 4.8911 | 1.558507e+00 | 1.534988e+01 | 0.00812* |

Coefficient estimates for predictor variables in the plankton biomass model (GLM), with estimates reported as log odds and odds ratios with upper and lower 95% confidence intervals (UCI, LCI).

*significant result.

Figure 4

Relationship between plankton biomass (mg/m³) and tidal cycle at the area in which more than 50% of all feeding behaviour was recorded during this study. The graph represents the distribution of plankton biomass at different hours relative to high tide. The dashed yellow line represents the prey density threshold for D’Arros Island (26.9 mg/m³), around which feeding behaviour is more likely to occur.

Despite known seasonal fluctuations in M. alfredi abundance at the site and several instances of higher plankton biomass recorded during the south-east monsoon, season had no statistical effect on M. alfredi feeding and plankton biomass.

4 Discussion

Findings from this study provide new insights into the feeding ecology of M. alfredi. The correlation between plankton biomass and manta feeding behaviour reported here aligns with previous studies that have indicated the requirement of dense plankton availability for M. alfredi feeding (Armstrong et al., 2016; Armstrong et al., 2021). Higher plankton biomass during feeding occurrence likely reflects M. alfredi’s need to target periods of increased prey abundance to meet its energetic demands (Meekan et al., 2015). Similarly, according to Armstrong (Armstrong et al., 2021), instances where plankton density was high, but feeding was not observed could be attributed to the composition of the zooplankton, with gelatinous species dominating certain samples, which was found to be avoided by M. alfredi in the Maldives (Armstrong et al., 2021). Due to time constraints, zooplankton composition, which requires extensive analysis, was excluded from this study; however, exploration of these data in future would help to address this.

In comparison to the PDT of 26.9 mg/m³ quantified around D’Arros Island, research conducted in Australia estimated a PDT of 11.2 mg/m³ (Armstrong et al., 2016), while research in the Maldives showed a substantially higher PDT of 53.7 mg/m³ (Armstrong et al., 2021). Such variations in PDT could be driven by adaptation to regional differences in food availability, related to habitat-specific features. PDT may therefore be linked to the size of a population using a given site, since food availability within a habitat can affect the population size of a species using it (Sibly and Hone, 2002; Edwards and Edwards, 2011). For example, the study in the Maldives, home to the largest recorded population of M. alfredi (~5,000 individuals), found higher PDT at Hanifaru Bay (53.7 mg/m³) than Seychelles (26.9 mg/m³, ~500 individuals) and Australia (11.2 mg/m³, ~1,000 individuals) (Armstrong et al., 2016; Armstrong et al., 2021). Alternatively, some sites may be preferentially selected as suitable not only for foraging but also for other key life history processes and that feeding a lower density thresholds allow M. alfredi to remain in areas important for these processes. Cleaning is an important behaviour in M. alfredi, and use of the cleaning stations at D’Arros has been shown to be an important driver of presence (Peel et al., 2024) with recent observations evidencing repetitive movements between feeding and cleaning (Newsome et al., 2024). Further research into the metabolic requirements of M. alfredi, potentially with the use of acceleration data loggers (Whitney et al., 2007; Armstrong et al., 2016), may also help to better define the underlying drivers of differences in prey density thresholds between different populations. However, these findings open opportunities for further research to better understand feeding thresholds both within and across geographically distinct populations.

Tide had the strongest correlation with zooplankton biomass, a previously known driver for plankton accumulation along coastlines (Alldredge and Hamner, 1980), and consequently M. alfredi feeding behaviour. The tidal trend reported here is similar to that reported from the Maldives (Armstrong et al., 2021), Indonesia (Dewar et al., 2008), Lady Elliot island eastern Australia (Armstrong et al., 2016), and the Chagos Archipelago (Harris et al., 2021). Tidal related changes in coastal currents, which transport zooplankton to nearshore areas, could influence the timing and locality of plankton accumulation. Slack periods over tidal cycles can create “quiet regions” which increases localised zooplankton abundance (Alldredge and Hamner, 1980). Studies from estuaries may suggest some explanations, especially the influence of slack tide on increased zooplankton abundance around the high tide. Vineetha et al. (2015) determined that periods of slack may allow zooplankton to carry out effective vertical migration in shallow areas, which they cannot do with tidal movements (Vineetha et al., 2015). Fine-scale spatial differences in the topography of D’Arros may influence surface accumulation of plankton. The shallow bank (<10m) on the northeastern side of D’Arros Island, where most feeding was recorded, may act as a buffer, with tidal movements and currents pushing zooplankton up the steep reef slopes adjacent to the shallow bank and to the surface. Not all samples collected during the peak around high tide observed M. alfredi feeding, suggesting that other factors such as plankton composition may be influencing surface abundance patterns. The topography and oceanic processes affecting the northeastern side of D’Arros, where M. alfredi tend to feed, could be further investigated to help better understand this spatial preference in comparison to the southwestern part of the island. For example, understanding how tides interact with other environmental drivers and geographical features to bring plankton to the surface, thereby supporting feeding in M. alfredi.

Since both GLM’s showed no significant seasonal differences in plankton biomass and feeding behaviour, this suggests that the variation in M. alfredi abundance throughout the year is not related to seasonal changes in food availability. However, the consistent year-round availability of prey may support the species throughout the year, highlighting the importance of this site for M. alfredi. This is supported by previous research which indicates that M. alfredi is present and feeding year-round at D’Arros Island (Peel et al., 2019b; Peel et al., 2020; Peel et al., 2024). By ruling out changes in plankton biomass throughout the year as a key factor for presence and absence of individuals, it creates opportunity for further research on the fluctuations in M. alfredi abundance and the habitat requirements for this species. For example, seasonal changes in M. alfredi numbers might be due to behavioural factors or life history traits, such as reproduction rather than feeding, as indicated by seasonal observations of courtship and mating behaviours at the site (SOSF-DRC unpublished data). The migration of females to other locations could also explain observed seasonal fluctuations (Peel et al., 2024). Average wind (which is stronger and more consistent in the south-east monsoon season) showed only a weak positive relationship to plankton biomass and no relationship with M. alfredi feeding behaviour which contrasts with findings from the Maldives where M. alfredi abundance has shown a strong relationship with wind (Harris et al., 2020). This could relate to the more pronounced seasonality in M. alfredi abundance at that study site, when compared to D’Arros.

These findings have direct conservation application in supporting the protection of feeding reef manta rays, which can be susceptible to boat strike injuries in coastal habitats (Strike et al., 2022). The D’Arros National Marine Park is a recently designated and gazetted Zone 1 marine protected area for high biodiversity protection that came into legal effect on 31st March 2025. The Save Our Seas Foundation represents the management authority for the D’Arros site and is responsible for developing site-specific management measures for this MPA. Data collected for this study should inform the placement of speed restriction zones, particularly in the the northeastern area of D’Arros in order to mitigate boat strike injuries.

There were several limitations to the study design which should be noted. Sampling efforts fluctuated across the year due to logistical constraints, such as unfavourable weather, meaning the sampling was not conducted throughout January and February 2024 and this could have hindered interpretation of seasonal effects on both M. alfredi behaviour and plankton biomass accumulation. GLM’s are useful to identify the drivers influencing plankton biomass and ultimately feeding behaviours. However, assessing the overall fine-scale interaction between a combination of drivers and factors, such as prey availability and their shifts, using traditional modelling approaches can be challenging and sometimes impractical. This is because important components such as topography and oceanographic processes, which are highly dynamic and can strongly influence how plankton accumulates (Richardson, 2008) are often excluded. It is recommended that future research better incorporates an understanding of spatial plankton dynamics at a fine-scale. To address this and integrate fine scale elements, a computer-based parameterization model could be developed to simulate plankton movement patterns around D’Arros Island and visually interpret the findings. Such approaches have previously been used to model oceanographic drivers of coral connectivity on a regional scale (Burt et al., 2024). This model would incorporate all additional suspected drivers and factors such as ocean currents, tides, wind patterns, water temperature, topography, and other environmental parameters collected over an extended period. Such a model could help predict plankton accumulation in specific areas and once calibrated to the known PDT at which M. alfredi typically begin feeding, generate predictions for M. alfredi visitation and visualize the interaction of these drivers. To date, no such model exists for this specific application, but might be worth pursuing and could be a valuable area of focus for future research.

5 Conclusion

Overall, this research showed that feeding behaviour in M. alfredi at D’Arros Island was significantly related to plankton biomass, which, in turn, was strongly influenced by tidal phases. A PDT was identified, which differs from those identified in two previous studies, and no seasonal shifts in feeding behaviour or plankton biomass were observed. The findings from this study will actively support management efforts for the D’Arros Island marine protected area by identifying key feeding areas and temporal patterns that drive M. alfredi surface feeding aggregations. From this it should be possible to demarcate specific coastal areas as a critical feeding ground within the MPA and to establish regulations, particularly regarding motorised activities that may disturb or injure individuals. The findings will also aid in predicting M. alfredi visitation patterns, improving research efficiency and long-term monitoring programs.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

All research conducted by the Save Our Seas Foundation D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF-DRC) including that presented here is done so under a research agreement with the Seychelles Ministry of Environment, Climate, Energy and Natural Resources (MECENR). No research undertaken conflicts with any regulations for the D’Arros Island marine protected area. All methods used for the field research were in compliance with relevant national and international guidelines, including the IUCN Policy Statement on research involving species at risk of extinction as well as CITES. Methods aligned with published best practice guidelines for swimming with manta rays. No stress was caused to reef manta rays nor was there any direct interaction with reef manta rays for this study.

Author contributions

DP: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology. JH: Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HG: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. EM: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. RB: Investigation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. All equipment and facilities used to undertake this work were provided by the Save Our Seas Foundation. The open access publication fee was covered by the University of Exeter.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the founder of the Save Our Seas Foundation for their generous support which made this work possible. The authors also extend their gratitude to interns and students of the Save Our Seas Foundation - D’Arros Research Centre that contributed in any way to the completion of this study. Dillys Pouponeau was additionally affiliated with the Jersey International Centre of Advanced Studies (JICAS) and acknowledges Dr. Sean Dettman for his support and guidance.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1645268/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alldredge A. L. Hamner W. M. (1980). Recurring aggregation of zooplankton by a tidal current. Estuar. Coast. Mar. Sci.10, 31–37. doi: 10.1016/S0302-3524(80)80047-8

2

Armstrong A. O. Armstrong A. J. Jaine F. R. A. Couturier L. I. E. Fiora K. Uribe-Palomino J. et al . (2016). Prey density threshold and tidal influence on reef manta ray foraging at an aggregation site on the Great Barrier Reef. PloS One11, e0153393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153393

3

Armstrong A. O. Stevens G. M. W. Townsend K. A. Murray A. Bennett M. B. Armstrong A. J. et al . (2021). Reef manta rays forage on tidally driven, high density zooplankton patches in Hanifaru Bay, Maldives. PeerJ9, e11992. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11992

4

Burnham K. P. Anderson D. R. (2004). Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods Res.33, 261–304. doi: 10.1177/0049124104268644

5

Burt A. J. Vogt-Vincent N. Johnson H. Sendell-Price A. Kelly S. Clegg S. M. et al . (2024). Integration of population genetics with oceanographic models reveals strong connectivity among coral reefs across Seychelles. Sci. Rep.14, 4936. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-55459-x

6

Calcagno V. de Mazancourt C. (2010). glmulti: an R package for easy automated model selection with (generalized) linear models. J. Stat. software34, 1–29. doi: 10.18637/jss.v034.i12

7

Castillo-Trujillo A. C. Arzeno-Soltero I. B. Giddings S. N. Pawlak G. McClean J. Rainville L. (2021). Observations and modeling of ocean circulation in the Seychelles plateau region. J. Geophysical Research: Oceans126, e2020JC016593. doi: 10.1029/2020JC016593

8

Couturier L. I. E. Jaine F. R. A. Townsend K. A. Weeks S. J. Richardson A. J. Bennett M. B. (2011). Distribution, site affinity and regional movements of the manta ray, Manta alfredi (Krefft, 1868), along the east coast of Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res.62, 628–637. doi: 10.1071/MF10148

9

Couturier L. I. E. Marshall A. D. Jaine F. R. A. Kashiwagi T. Pierce S. J. Townsend K. A. et al . (2012). Biology, ecology and conservation of the Mobulidae. J. fish Biol.80, 1075–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03264.x

10

Couturier L. I. E. Rohner C. A. Richardson A. J. Marshall A. D. Jaine F. R. A. Bennett M. B. et al . (2013). Stable isotope and signature fatty acid analyses suggest reef manta rays feed on demersal zooplankton. PloS One8, e77152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077152

11

Dewar H. Mous P. Domeier M. Muljadi A. Pet J. Whitty J. (2008). Movements and site fidelity of the giant manta ray, Manta birostris, in the Komodo Marine Park, Indonesia. Mar. Biol.155, 121–133. doi: 10.1007/s00227-008-0988-x

12

Edwards W. Edwards C. (2011). Population limiting factors. Nat. Educ. Knowledge3, 1.

13

Fox J. Weisberg S. (2018). An R companion to applied regression. (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications).

14

Harris J. L. Embling C. B. Alexander G. Curnick D. Roche R. Froman N. et al . (2023). Intraspecific differences in short-and long-term foraging strategies of reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi) in the Chagos Archipelago. Global Ecol. Conserv.46, e02636. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2023.e02636

15

Harris J. L. Hosegood P. Robinson E. Embling C. B. Hilbourne S. Stevens G. M. W. (2021). Fine-scale oceanographic drivers of reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi) visitation patterns at a feeding aggregation site. Ecol. Evol.11, 4588–4604. doi: 10.1002/ece3.7357

16

Harris J. L. McGregor P. K. Oates Y. Stevens G. M. W. (2020). Gone with the wind: Seasonal distribution and habitat use by the reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi) in the Maldives, implications for conservation. Aquat. Conservation: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst.30, 1649–1664. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3350

17

Komdeur J. Daan S. (2005). Breeding in the monsoon: semi-annual reproduction in the Seychelles warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis). J. Ornithology146, 305–313. doi: 10.1007/s10336-005-0008-6

18

Last P. R. Stevens J. D. (2009). Sharks and rays of Australia (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing).

19

Marshall A. Barreto R. Carlson J. Fernando D. Fordham S. Francis M. P. et al . (2022). Mobula alfredi (amended version of 2019 assessment). doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T195459A214395983.en

20

McCullagh P. (2019). Generalized linear models. ( Routledge).

21

Meekan M. G. Fuiman L. A. Davis R. Berger Y. Thums M. (2015). Swimming strategy and body plan of the world’s largest fish: implications for foraging efficiency and thermoregulation. Front. Mar. Sci.2, 64. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2015.00064

22

Newsome R. J. Grimmel H. M. V. Pouponeau D. K. Moulinie E. E. Andre A. A. Bullock R. W . (2024). Eat-clean-repeat: reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) undertake repetitive feeding-cleaning cycles at an aggregation site in Seychelles. Front. Mar. Sci.11, 1422655. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1422655

23

Peel L. R. Daly R. Keating Daly C. A. Stevens G. M. W. Collin S. P. Meekan M. G. (2019a). Stable isotope analyses reveal unique trophic role of reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) at a remote coral reef. R. Soc. Open Sci.6, 190599. doi: 10.1098/rsos.190599

24

Peel L. R. Stevens G. M. W. Daly R. Daly C. A. K. Lea J. S. E. Clarke C. R. et al . (2019b). Movement and residency patterns of reef manta rays Mobula alfredi in the Amirante Islands, Seychelles. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.621, 169–184. doi: 10.3354/meps12995

25

Peel L. R. Stevens G. M. W. Daly R. Keating Daly C. A. Collin S. P. Nogués J. et al . (2020). Regional movements of reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) in Seychelles waters. Front. Mar. Sci.7, 558. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00558

26

Peel L. R. Meekan M. G. Daly R. Keating C. A. Collin S. P. Nogués J. et al . (2024). Remote hideaways: first insights into the population sizes, habitat use and residency of manta rays at aggregation areas in Seychelles. Mar. Biol.171, 83. doi: 10.1007/s00227-024-04405-6

27

Richardson A. J. (2008). In hot water: zooplankton and climate change. ICES J. Mar. Sci.65, 279–295. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsn028

28

Schott F. A. McCreary J. P. Jr . (2001). The monsoon circulation of the Indian Ocean . Prog. Oceanography51, 1–123. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6611(01)00083-0

29

Sibly R. M. Hone J. (2002). Population growth rate and its determinants: an overview. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B: Biol. Sci.357, 1153–1170. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1117

30

Strike E. M. Harris J. L. Ballard K. L. Hawkins J. P. Crockett J. Stevens G. M. W. (2022). Sublethal Injuries and Physical Abnormalities in Maldives Manta Rays, Mobula alfredi and Mobula birostris . Front. Mar. Sci.9, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.773897

31

Vineetha G. Jyothibabu R. Madhu N. V. Kusum K. Sooria P. M. Shivaprasad A. et al . (2015). Tidal influence on the diel vertical migration pattern of zooplankton in a tropical monsoonal estuary. Wetlands35, 597–610. doi: 10.1007/s13157-015-0650-6

32

Weeks S. J. Magno-Canto M. M. Jaine F. R. A. Brodie J. Richardson A. J. (2015). Unique sequence of events triggers manta ray feeding frenzy in the Southern Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Remote Sens.7, 3138–3152. doi: 10.3390/rs70303138

33

Whitney N. M. Papastamatiou Y. P. Holland K. N. Lowe C. G. (2007). Use of an acceleration data logger to measure diel activity patterns in captive whitetip reef sharks, Triaenodon obesus. Aquat. Living Resour.20, 299–305. doi: 10.1051/alr:2008006

34

Zuur A. F. Ieno E. N. Elphick C. S. (2010). A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol.1, 3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x

Summary

Keywords

conservation, elasmobranch, foraging ecology, filter feeder, marine protected area, planktivores, threatened species, zooplankton

Citation

Pouponeau DK, Harris JL, Grimmel HMV, Moulinie EE and Bullock RW (2026) Manta munchies: plankton dynamics and feeding behaviour of reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) around D’Arros Island in the Seychelles. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1645268. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1645268

Received

11 June 2025

Revised

14 December 2025

Accepted

15 December 2025

Published

20 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Mark Meekan, University of Western Australia, Australia

Reviewed by

Luciana C. Ferreira, Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), Australia

Abigail Mary Moore, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Pouponeau, Harris, Grimmel, Moulinie and Bullock.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dillys K. Pouponeau, dillys@saveourseas.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.