Abstract

In this review, the potentials of jellyfish-based plastics as an alternative to conventional plastics are looked at principally regarding their use at sea. The collagen and additional biopolymers extracted from jellyfish have distinct physical and chemical properties i.e., biodegradability, toughness, and can blend with the environment, which enables it to manufacture green material to substitute the plastic fillers found in the ocean. In the review, what is known about jellyfish biomolecules is summarized, their properties studied, and how these biomolecules are subjected to biodegradation in marine ecosystems, as well as their use to package, create fishing gear, marine sensors, and agrochemical release controls in aquaculture, is discussed. The effect of environmental factors on the degradation, useful life cycle and large-scale production and regulation challenges are also examined. This review applies the concepts of material science, marine biotechnology, and environmental policies to suggest significant research gaps, as well as describe potential new concepts that can support the application of jellyfish-derived bioplastics to create marine and environmental sustainability.

1 Introduction

The problem of plastic waste that has accumulated in the marine environment recently is regarded as one of the most severe and rapidly spreading environmental problems of the modern time. It is estimated that 8 million metric tons of plastic waste are released into the world oceans annually, polluting both the nearshore and the deep ocean environment (Thushari and Senevirathna, 2020). The majority of convention plastics are manufactured using a petroleum product such as polyethylene, polypropylene and polystyrene all created to be tough, durable and resistant to deterioration. These properties make plastics useful in so many ways but it is through them that nature is polluted since biological methods cannot easily break down plastics. When the plastics are released into the water, they are physically broken by exposure to ultraviolet radiation, mechanical abrasion, and decomposition by living organisms into microplastic (0.5 mm) and nanoplastics (0.1 nm). These small plastic pieces may be ingested by a wide variety of marines including zooplankton and giant marine mammals, to enter and bioaccumulate in complex food webs (Diepens and Koelmans, 2018). This has contributed to the widespread contamination when they get accumulated on oceans; marine organisms are contaminated via ingestion, entangling, and even changing habitats (Thushari and Senevirathna, 2020). Environmental plastic pollution may also cause physical challenges and harm the internal frameworks, result in the chemical release and alter behaviors of reproduction and food consumption and degrade the ecosystem processes. The combined effect of these impacts is a threat to biodiversity in the sea, fisheries and finally human health through food intake, i.e. through seafood (Kumar et al., 2021). Bio plastics are a wide category of materials that are made of biological sources such as polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids with aim of matching the functional characteristics of the traditional plastics and being more environmentally compatible (Shafqat et al., 2020). The properties of algae, crustaceans, and gelatinous zooplankton provide beneficial marine organism biopolymers suitable in the production of bioplastics (Samalens et al., 2022). An interesting solution in marine biotechnology is exploiting the jellyfish to produce sustainable bioplastics. The phylum Cnidaria consisting of jellyfish has increasingly gained significance in the past years both ecologically and biotechnologically. There have been remarkable population increases of them in most of the coasts, which are most recently linked to human activities, such as overfishing, and climate change (Tinta et al., 2019). Jellyfishes consist mainly of water in their biomass (ca. 95%), however, their dry tissue includes large proportions of collagen as well as other proteins that have extraordinary mechanical and biochemical properties (Cadar et al., 2023). Jellyfish derived collagen has been investigated because of its biocompatibility and low immunogenicity in possible biomedical use.

There is potential of degrading these bioplastics by sun and water which would be less harmful to the natural ecosystems as compared to the regular plastic. Moreover, the use of jellyfish biomass will potentially help to control jellyfish blooms, with its economic and ecological effects (Chia et al., 2020). Significantly, a large portion of bioplastics is designed to be biodegraded or composted under specific environmental factors, which theoretically allows them to decompose by means of bacterial/microbial enzymes. Nevertheless, not all bioplastics are the same since they may be composed of a wide variety of chemical compounds and decay at different time rates. Not every bioplastic has its effective biodegradation in marine environment; some types need conditions of industrial composting, and others degrade poorly or not in the ocean (Folino et al., 2020). The most significant research and business interest should be to speedily produce rapidly degrading bioplastics which can easily address the plastic waste in aquatic and marine ecosystem as a whole.

Although jellyfish consist largely of water (about 95%), they still have the remainder of the dry biomass in them, and it contains important amounts of collagen and glycoproteins, which show excellent biodegradability, biocompatibility, and good mechanical qualities, making them potentially usable biomaterials (Harussani et al., 2023). The collagen of jellyfish has different structural properties, unlike mammalian ones, and the lower immunogenic epitope and its unique amino acids profile contribute to its applicability in biomedical devices, tissue engineering, scaffold, and environmentally compatible materials (Ahmed et al., 2021). New methods of purification and extraction have allowed obtaining high-purity collagen and gelatin of jellyfish species of different kinds, which contributes to the use of jellyfish in bioplastics, wound dressings, and biodegradable films (Islam and Mis Solval, 2025). In addition to the collagen, jellyfish engender other bioactive materials such as mucus and secretion of bioactive compounds, which are characterized by antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects and can be incorporated in the development of composite biomaterials (Rigogliuso et al., 2023).

Jellyfish valorization is not only a promising solution to the adverse effects of blooms but also helps produce bio-based material with an ecological footprint (Vieira Veríssimo et al., 2021). Still, the major issues remain surrounding the unification of extraction procedures as well as the ability to reproduce properties of the materials, and adequately assess environmental safety and biodegradability of products obtained using jellyfish (Coppola et al., 2020). This review is a summary of the current state of research or development of jellyfish biomaterials with particular consideration to how it can be used in the development of bioplastics with a focus on marine sustainability. It examines all significant processes that should take part in characterizing the composition, the isolation techniques and the characteristics of jelly fish collagen and other polymers utilized in the production of bioplastics. The degradability of the bioplastics produced by jellyfish in the ocean sphere is also studied in terms of the temperature, the salinity, the presence of the UV radiation, and the activity of the present microorganisms. The research into the potential use of these materials in marine industries through the production of biodegradable packaging, fishing nets and aquaculture tools is given with the aim to demonstrate how this practice can join the cause of combating marine plastic pollution. It also presents issues that are associated with the production of bigger batches, minimizing environmental impact during the life cycle, using rules and guidelines, and responding to unanswered questions to ensure that the jellyfish-based bioplastics can be applied more commonly. This way, the review is in line with the mission to identify and expand to new forms of materials that assist in preserving the oceans and the environment. This review will represent a critical synthesis of the present findings, rather than a descriptive. Every segment has been designed so that the results from the original experiment studies can be compared and evaluated. In addition, the section discusses the strengths, weaknesses and gaps of study methodologies. Peer review experimental work, not secondary review sources, is becoming the driving force for scientific credibility.

2 Jellyfish biomolecules as bioplastics

The jellyfish can be a new underwater source of extracting biomolecules, which manufactures bioplastics. Except for water content, the remaining jellyfish component is composed of a large portion of proteins, polysaccharides, lipids and polymeric biomolecules that are significant in the construction of sustainable materials for degradable bioplastics (D’Ambra and Merquiol, 2022). The study of the individual components and operation of each of these biomolecules is paramount towards having a bioplastic developed that will aid in mitigating the rising cases of pollution by plastics in the ocean. It investigates the valuable biomolecules such as collagen and other proteins of jellyfish that represent bioplastics and the other forms of biopolymer (Coppola et al., 2020). It explains the process of mining, how to mine it by extracting it in the best possible way and making the most out of it (Table 1).

Table 1

| Extraction method | Jellyfish species | Collagen type(s) | Key parameters | Yield (%) | Purity (%) | Advantages | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acid Solubilization | Nemopilema nomurai | Type I-like, II-like | 0.5 M Acetic acid, 24–48 h, 4°C | 50–60 | 85–90 | Simple, low cost | Longer extraction time | (Ma et al., 2024) |

| Enzymatic (Pepsin digestion) | Rhopilema esculentum | Type I-like | Pepsin 1%, 24–48 h, pH 2–3 | 65–75 | >95 | Higher purity, preserves triple helix | Enzyme cost, sensitive process control | (Liu et al., 2013) |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction | Aurelia aurita | Type I-like | Ultrasound 150 W, 20–30 min, 25°C | 70–80 | 90–95 | Faster, eco-friendly | Equipment cost | (Balikci et al., 2024a) |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction | Phyllorhiza punctata | Type I and II-like | Microwave 300 W, 10 min, acid solvent | 60–70 | 88–92 | Rapid process | Possible molecular damage | (Carneiro et al., 2011) |

| Enzymatic + Acid Combination | Cyanea capillata | Type II-like | Pepsin + Acetic acid, 24 h, 4°C | 68 | >90 | Improved yield and purity | Multi-step complexity | (Zhang et al., 2017) |

| Subcritical Water Extraction | Chrysaora quinquecirrha | Type I-like | 150°C, 30 min, water under pressure | 55–65 | 85–90 | Solvent-free, environmentally benign | Requires specialized equipment | (Bloom et al., 2001) |

| Enzymatic Hydrolysis (Collagenase) | Pelagia noctiluca | Type I-like | Collagenase digestion, 24 h, pH 7 | 60–70 | 93 | High specificity | Expensive enzymes, longer process | (Marino et al., 2008) |

| Alkali Pretreatment + Enzyme | Rhizostoma pulmo | Type I and II-like | NaOH pretreatment + pepsin digestion | 65 | 90 | Improved purity, effective deproteinization | Alkali waste handling | (Rastogi et al., 2017) |

| Acid Solubilization + Ultrasound | Mastigias papua | Type I-like | 0.5 M Acetic acid + Ultrasound 100 W, 30 min | 70–78 | 92–95 | Increased yield, shorter time | Equipment and process optimization needed | (Djeghri et al., 2021) |

| Enzymatic Extraction + Freeze Drying | Cassiopea andromeda | Type I-like | Pepsin digestion + freeze drying | 68–72 | >95 | Preserves structure and purity | Freeze drying cost | (De Domenico et al., 2023) |

Extraction methods and yields of jellyfish collagen.

Table 1 shows that the extraction efficiency and quality of jellyfish collagen depend strongly on the method used, the species processed, and the extraction parameters. Acid-solubilization approaches typically yield 50–60% collagen with 85–90% purity, as shown for Nemopilema nomurai (Ma et al., 2024), making this method simple and low-cost but time-intensive. In contrast, enzymatic extraction—especially pepsin digestion—provides higher yields (65–75%) and exceptional purity (>95%), as demonstrated for Rhopilema esculentum (Liu et al., 2013), due to better preservation of the collagen triple helix. Newer technologies such as ultrasound-assisted extraction yield 70–80% collagen with high purity (90–95%) in Aurelia aurita (Balikci et al., 2024), offering faster and more energy-efficient processing. Microwave-assisted extraction produces rapid yields of 60–70% for Phyllorhiza punctata (Carneiro et al., 2011), although risks of thermal denaturation remain. Combined acid–enzyme protocols improve collagen recovery to around 68% with >90% purity in Cyanea capillata (Zhang et al., 2017), while subcritical water extraction, though equipment-dependent, provides an eco-friendly method yielding 55–65% collagen from Chrysaora quinquecirrha (Bloom et al., 2001). Collagenase digestion and alkali pretreatments further enhance purity in species such as Pelagia noctiluca (Marino et al., 2008) and Rhizostoma pulmo (Rastogi et al., 2017). Overall, the table highlights that enzymatic and ultrasound-assisted extraction methods consistently deliver the highest purity and yield, positioning them as optimal candidates for producing high-quality collagen suitable for bioplastic fabrication.

2.1 Collagen and proteins content in jellyfish

The presence of collagen contributes more than 70 as well as 80 percent of dry weight in jellyfish mesoglea. In contrast to mammalian collagen which is predominantly composed of types I, II and III, jellyfish collagen is enriched with type I and II collagen-like protein and is unique in its structure in that it increases the flexibility of the jellyfish and also decreases the chances of realizing an immune response (Ahmed et al., 2021) (Table 2). The triple-helical structure facilitates the material to work properly by endowing strength and heating-resistance by glycine, proline and hydroxyproline that are in large extent. The chemical composition of jellyfish collagen shows that it is composed of dissimilar amino acids when compared to earth collagen and could be of beneficial application to biomedical and environment science.

Table 2

| Jellyfish species | Water content (%) | Collagen content (% dry weight) | Glycoproteins (%) | Polysaccharides (%) | Protein content (% dry weight) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nemopilema nomurai | ~95 | 65–75 | 10–15 | 5–8 | 70–80 | (Geng et al., 2024) |

| Rhopilema esculentum | ~94 | 60–70 | 12–18 | 6–10 | 65–75 | (Pivnenko et al., 2022) |

| Aurelia aurita | ~96 | 55–65 | 10–12 | 4–7 | 60–70 | (Balikci et al., 2024b) |

| Cyanea capillata | ~95 | 58–68 | 11–14 | 5–9 | 65–78 | (Sipos and Ackman, 1968) |

| Chrysaora quinquecirrha | ~93 | 50–60 | 9–13 | 6–11 | 60–72 | (Xia et al., 2021) |

| Cassiopea andromeda | ~94 | 52–63 | 8–12 | 7–10 | 58–70 | (De Rinaldis et al., 2021) |

| Phyllorhiza punctata | ~95 | 55–67 | 10–16 | 5–9 | 62–75 | (Rodrigues et al., 2025) |

| Pelagia noctiluca | ~94 | 53–65 | 9–14 | 6–8 | 60–72 | (Malej et al., 1993) |

| Rhizostoma pulmo | ~95 | 56–66 | 11–15 | 5–9 | 63–74 | (Stabili et al., 2019) |

| Mastigias papua | ~93 | 54–64 | 8–13 | 6–10 | 60–73 | (Djeghri et al., 2021) |

Biochemical composition of selected jellyfish species.

Table 2 highlights clear biochemical differences among jellyfish species that influence their potential use in bioplastics. Species such as Nemopilema nomurai exhibit the highest collagen contents (65–75%), as reported by Geng et al. (2024), while Rhopilema esculentum similarly shows 60–70% collagen (Pivnenko et al., 2022), making both ideal for applications requiring strong, structurally stable bioplastic films. Aurelia aurita contains slightly lower collagen levels (55–65%) (Balikci et al., 2024), yet retains balanced polysaccharide and glycoprotein fractions that enhance film-forming ability. Historical reports such as Sipos and Ackman (1968) for Cyanea capillata and Malej et al. (1993) for Pelagia noctiluca provide consistent protein-rich compositions suitable for biopolymer processing. Species including Cassiopea andromeda (De Rinaldis et al., 2021) and Chrysaora quinquecirrha (Xia et al., 2021) offer moderate collagen (50–63%) but higher glycoprotein and polysaccharide levels that contribute to elasticity, hydration and flexibility, beneficial for softer or composite bioplastic designs. Phyllorhiza punctata also provides a balanced biochemical profile (Rodrigues et al., 2025), enabling its use in blended biomaterials. Overall, Table 2 indicates that species rich in collagen (e.g., N. nomurai, R. esculentum) are best suited for mechanically strong bioplastics, whereas species with higher polysaccharides and glycoproteins offer better viscoelasticity, water-binding capacity, and functional adaptability, making them advantageous for tailored marine bioplastic formulations.

Other proteins are fibrillar, glycoproteins and various enzymes in the mesoglea. It is due to these proteins that the gelatinous matrix is made elastic, viscoelastic and tough. Carbohydrate moieties in glycoproteins modify the potential of them to interact with the water molecules and aid in the creation of materials that consist of other biomolecules, providing biomaterials with the necessary strength and functionality (Su et al., 2021). Connectivity between collagen fibers in jellyfish provides bioplastics produced of them with a greater possibility to remain stable and biodegraded upon a specified period of time (Ballesteros et al., 2025). Jelly farms contain proteoglycans and mucopolysaccharides that assist the body in retaining water and helping its bodies. There are possibilities when making changes to biopolymers in collagen based biomaterials which may alter the material and its muscle like properties e.g. tensile strength and/or elasticity and breakdown of such materials. There are many theories that Jellyfish-based materials can heal themselves out which is aided by enzymes contained in their matrix so as we can utilize their self-healing properties and create adaptive and self-healing plastic.

2.2 Other biopolymers extracted from jellyfish, aside from collagen

Other than collagen and proteins, jellyfish would also be usable to form other biopolymers which may be used as bioplastics. The water retention and stiffness is also due to Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which are sulfated polysaccharides found in the jellyfish mesoglea. Polymersomes resemble chondroitin sulfate and hyaluronic acid, therefore, possessing such important characteristics as water-absorption capability, body-safety and biodegradability. Jellyfish GAGs extraction can be resourceful in the formation of bioplastics, which are bendable and can easily degrade in the ocean water (Bhende et al., 2023). Jellyfish mucus is a complex mixture of proteins, lipids and carbohydrates that exhibit antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Bio plastics can be more effective as packaging and defend the marine coatings because the jellyfish mucus or the active substances kept the growth of the microbes, the duration of the product in fouling and increment of the storage life. They are quite useful in a scenario where something is going to be in the sea water a long time. The other jellyfish side product, collagen gelatin, is a biopolymer that was recognized to form robust films (Farooq et al., 2024). Jellyfish gelatin is mechanically good and has the ability to form thin, tough and clear films which can be used as biodegradable wrappings. These composites can possess enhanced strength and barriers because it can be combined with other bio-polymers very effectively. The use of various biopolymers made of jellyfish creates numerous possibilities to develop new bioplastics that will save the environment (Steinberger et al., 2019).

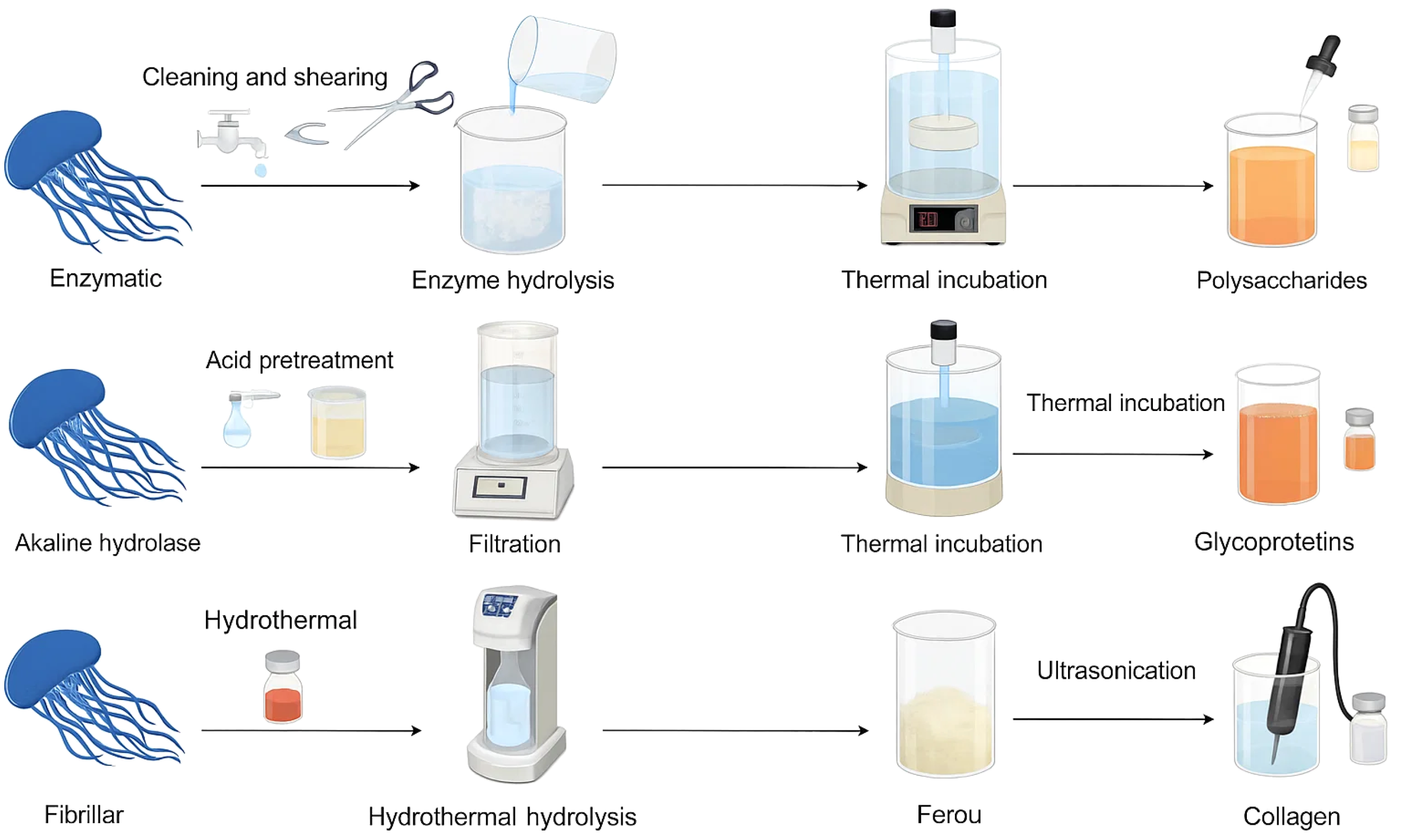

2.3 Extraction and purification

Another significant factor that leads to bioplastic production is how well the jellyfish biomolecules are extracted and purified (Figure 1; Table 2). The collagen is typically extracted by dissolving its bonds using diluted acetic acid followed by the further degradation of the collagen using a collection of enzymes referred to as proteases. In this step the enzyme fragments some areas of the fibril, without modifying the triple helix required to perform its functions. The yield of collagen as well as its qualities depends much on time of extraction, temperature, pH and enzyme quantity. Apart from acid dissolution and enzymatic digestion, there are other ways to extract. They include alkaline hydrolysis, ultrasound-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, and sub/supercritical extraction. Each approach offers specific benefits and trade-offs. An example of this is ultrasound- and microwave-assisted techniques that enhance extraction and diminish solvent use, they might create risks for collagen denaturation. The use of pepsin or collagenase for enzymatic hydrolysis provides better quality but is expensive. Alkaline pretreatment could effectively eliminate non-collagenous proteins but produces chemical waste. In order to understand which protocol is the most sustainable and efficient, the parameters must be evaluated. Additional purification removing any remaining non-collagenous proteins and enzymes, and salts is achieved via methods of salt precipitation (usually using NaCl), dialysis and filtration. Traditionally, due to the use of ultrafiltration and chromatography, the purity of collagen is increased, and the various types of collagen can be separated with respect to each other (Ahmed et al., 2020). SDS-PAGE, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) are the essential tests to characterize the molecules, to determine their integrity and fitness to undergo the subsequent steps of processing. Enzymatic digestion is used to degrade proteins in glycosaminoglycans after extraction in water, then subsequent precipitation using organic solvents e.g. ethanol, or cetylpyridinium chloride. Such methods as ultrasound-assisted extraction and membrane filtration have been verified in order to simplify extraction process, reducing the amount of used solvents and scaling up the project (Cauduro et al., 2025). These technologies aim at reducing impact on the nature and making their usage at scale as accessible as possible. But it is hard to standardize the protocol across a very broad range of jelly populace, and to handle the variation season to season in biomass, and ensure a habitually reproducible batch. The solutions to these issues become very essential to convert jellyfish biomolecules of experimental purposes into commercial applications.

Figure 1

Overview of extraction and purification routes for jellyfish collagen and associated biopolymers.

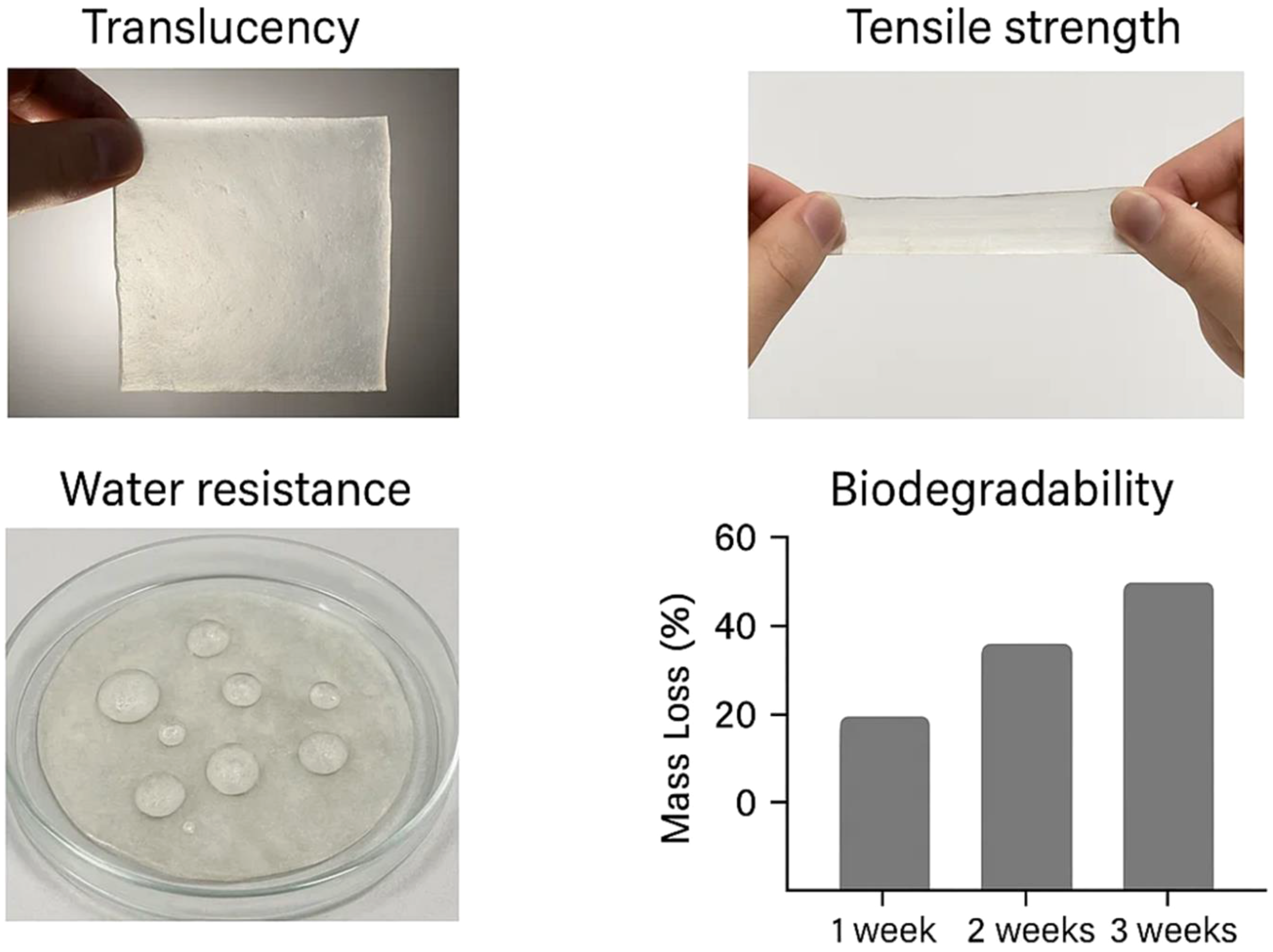

3 Jellyfish as bioplastics have physical and chemical characteristics that differ structurally

It is the physicochemical characteristics of jellyfish-based bioplastics that influence its performance, strength and ecological advantages strongly. They will decide how effectively these materials will respond during processing, in use and when they begin to wear out. Their physical properties strength, temperature tolerance etc should also be deeply compared so as to design their usage to the ocean as well as to the health. The remaining aspect in this section is key physicochemical properties, including mechanical strength or flexibility, ability to resist high temperatures, and safety of their use (Figure 2). Before discussing mechanical strength, it is important to outline the fundamental characteristics of jellyfish-based bioplastics, including composition, film-forming ability, and crosslinking potential, as these factors directly influence subsequent processing behavior.

Figure 2

Conceptual representation of physical and chemical properties of jellyfish-based bioplastics.

3.1 The quality of muscles structure and adaptation

To make any bioplastic successful in real application, it should be strong and ductile due to the fact that this is the measure of how easily the material can withstand damage due to applying external loads and remain intact as its shape varies. Collagen, which is jellyfish bioplastics, relies primarily on the protein, which has a triple-helix structure and offers superior tensile force and elasticity. The mechanical behavior of collagen-based bioplastics depends, to a large extent, on the methods of extraction, their level of crosslinking and post-processing treatments. Empirical results have indicated that jellyfish collagen films and composites had tensile strength capabilities of about 30 to 70-megapascals (MPa), competitive with ground-based collagens. As an example, polymers/composites built out of N. nomurai collagen achieved tensile strengths of more than 60 MPa, following improved enzymatic extraction and chemical crosslinking, representing similar values to certain commercial synthetic biopolymers (Balikci et al., 2024). This tensile strength and significant elongation at break (up to 30%), suggests a good balance between strength and flexibility, which are much required in flexible packaging, biodegradable nets, and marine coatings.

There are very large numbers of collage based medical devices relying on glutaraldehyde, genipin and carbodiimides to bond collagen molecules and reinforce the device against mechanical and water degradation. At that, with excessively strong crosslinking, the product obtained may be inflexible and probably crack under the pressure. Consequently, the crosslinking should be well-balanced in order to obtain the optimum balance of strength and flexibility. The addition of plasticizers such as small polymers such as glycerol, sorbitol or polyethylene glycol has also been effective in breaking the hydrogen bonding between the collagen chains, thereby enhancing chain mobility in the polymer and enhancing flexibility and extensibility (Vieira et al., 2011). Composites of jellyfish collagen and substances such as chitosan, alginate or gelatin can be mixed, providing a stronger mechanic of bioplastics, increased toughness and better inherence to substances. These composites have greater water vapor permeability and retention of elasticity than collagen films, which increases their applicability (Coppola et al., 2020). Jellyfish bioplastics can handle a change in form and will unload energy when required, because they are viscoelastic, which is significant to use in the sea, where they would absorb variance in loading. The rheological studies results show that jellyfish collagen bioplastics are more processable, but do not disintegrate, as they stiffen. Studies have shown that jellyfish-based films have tensile strengths of around 30–70 MPa. These original studies, such as (Balikci et al., 2024) have some key differences in extraction conditions and crosslinker type. In the future studies should quantify elasticity and water-vapor permeability to maximize the applications in flexible packaging and marine coatings.

3.2 Describing thermal behavior and technical processing

Bioplastics are considered thermally stable when they do not lose their functions or deteriorate at different temperatures during each stage of their use. Jellyfish collagen undergoes denaturation at temperatures as low as 30°C to 50°C, compared to mammalian collagen. Differences in protein building blocks, their crosslinks and special types of sugar molecules are the reasons why. High processing temperatures aren’t recommended because collagen’s heat stability is low, yet solvent methods at low temperatures are preferred and commonly apply to the manufacture of collagen films and scaffolds (Zhang et al., 2020). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of jellyfish collagen bioplastics reveals a multi-phase thermal degradation profile. Moisture loss happens as the material warms from 50°C to 120°C and then degradation of the polypeptide chains occurs above 200°C. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) studies typically identify endothermic peaks representing collagen denaturation and thermal decomposition. These thermal transitions guide selection of processing temperatures to avoid compromising the triple-helical structure, which is critical for mechanical performance and biodegradability (Li et al., 2025; Yorke et al., 2025). Microstructure, thermal properties and pH, ion concentration and drying speed all influence the bioplastics produced. If drying occurs slowly and under control, films become denser and more uniform with better mechanical and barrier properties. By contrast, rapid drying may result in brittle and porous films. Furthermore, plasticizers reduce intermolecular hydrogen bonding, lowering glass transition temperatures and improving thermal flexibility at the expense of some thermal resistance (Lian et al., 2019; Han et al., 2024). Mixing jellyfish collagen with polysaccharides or synthetic biodegradable polymers makes the material more heat tolerant and easier to process. For example, composite materials with alginate or polylactic acid have demonstrated improved heat resistance, enabling applications requiring sterilization or higher temperature exposure. The best results are obtained when these blends are optimized to both resist harsh industry processes and still degrade in the environment.

3.3 Before using biomaterials, we must check if they are biocompatible and safe

Bioplastics designed for medical or marine uses must be both safe and biocompatible. Jellyfish collagen has proven to be biocompatible, with few studies reporting either immunogenicity or cytotoxicity. The molecular uniqueness of jellyfish collagen, including differences in amino acid sequences and reduced antigenic determinants compared to mammalian collagen, underlies its favorable biological profile (Addad et al., 2011; Rigogliuso et al., 2023). Genipin and other natural crosslinkers or the enzymatic route, allow biocompatible materials to be made rather than using the toxic by-products of synthetic agents such as glutaraldehyde. Moreover, the degradation products of jellyfish collagen bioplastics are typically non-toxic amino acids and peptides, mitigating ecological and health risks during material breakdown in marine or biological environments (Baksi et al., 2025).

When materials are used in marine environments, biofouling occurs which can have a major impact on a material’s longevity. Incorporation of bioactive compounds derived from jellyfish mucus, known for antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, can confer inherent resistance to biofouling, reducing the need for synthetic biocides harmful to marine ecosystems (Jayaprakashvel et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2024). This property ensures bioplastic devices are safe to use and last longer than other bioplastics. It is important to test all aspects of ecotoxicology to confirm that neither bioplastics nor their by-products harm marine organisms at every level of the food chain. At this early stage, safety indicators look good, yet additional studies are needed to check how well jellyfish-based bioplastics are suited for large-scale environmental use. When we look at all the important physicochemical features, it’s clear that jellyfish-based bioplastics are excellent alternatives to traditional plastics. Research should continue to help optimize these properties and ensure they are safe for the environment, so they can be used for fighting marine plastic pollution and developing marine biotechnology.

4 Biodegradation

The biodegradability of jellyfish bioplastics decides whether they are compatible and sustainable in maritime environments. The chemicals in jellyfish-derived bioplastics are safely biodegradable within months, in contrast to conventional plastic which stays in the environment for long periods. Such biomolecules are more vulnerable to damage from natural forces and living organisms seen in the ocean. Realizing how biodegradation works, how fast it can happen and which factors affect it is key for developing new bioplastics that minimize environment damage.

4.1 The ways biodegradation happens in marine environments

Biodegradation of polymers in oceans happens as different factors such as chemical, physical and biological, play their respective roles sequentially and together. Initially, abiotic degradation occurs through photodegradation by ultraviolet (UV) radiation, mechanical abrasion from wave action, tidal forces, and sediment friction, as well as hydrolysis facilitated by seawater chemistry. These processes induce polymer chain scission, surface erosion, and increased porosity, which expose new reactive sites and enhance microbial colonization (Bond et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2022). Because jellyfish bioplastics are made of protein, enzymes can digest them efficiently. Marine bacteria and fungi secrete collagenases, proteases, and peptidases that cleave peptide bonds within the collagen matrix, converting high-molecular-weight proteins into peptides, amino acids, and ultimately mineralizing these into carbon dioxide, water, and microbial biomass (Bhende et al., 2023). This enzymatic hydrolysis typically proceeds via extracellular digestion, with microbes forming biofilms on the polymer surface to concentrate enzymatic activity. Moreover, biofilms not only facilitate degradation by creating a localized microenvironment but also promote syntrophic microbial interactions, enhancing biodegradation pathways (Al-Madboly et al., 2024). The rates of degradation are controlled by how salty the water is, how much oxygen is dissolved and the presence of needed nutrients for microbes. Compared to synthetic plastics, which lack enzymatic recognition sites and are chemically inert, jellyfish bioplastics are more readily assimilated by native marine microbiota (Mohanan et al., 2020).

4.2 How much these types of plastic degrade and how fast compared to typical products

The plastics degradation rate and number of plastics exist are tightly linked to their effect on the environment. Conventional plastics like polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS) possess stable carbon-carbon bonds that are resistant to hydrolysis and enzymatic breakdown, leading to accumulation and fragmentation into persistent microplastics (Cai et al., 2023). Such persistence contributes to long-term ecological and health hazards including bioaccumulation of toxic substances and physical harm to marine organisms. Jellyfish-derived bioplastics are known to degrade rapidly and converts fully into mineral form in the presence of water. Controlled laboratory studies have reported mass losses exceeding 60–80% within 90 days for collagen-based films in simulated seawater conditions (Coppola et al., 2020). The quick decay of these materials brings down the risk of microplastics fragmentation and the related negative impacts. But the rate of degradation varies significantly with the way materials are manufactured. High crosslink density or incorporation of non-biodegradable additives can reduce enzymatic accessibility and slow degradation (Yao et al., 2025). Modifying the moisture and crystalline properties of polymers increases the chance of microbial growth and increases the rates of enzymatic reactions. Real-world degradation may be further influenced by biofouling, sediment burial, and physical abrasion, which can either facilitate fragmentation or shield polymers from microbial attack (Zhang et al., 2024). To confirm laboratory results and measure environmental stability, long-term in situ tests are necessary because marine influence and ecology can be different in various regions.

4.3 Influence of environmental factors (temperature, salinity, microbes)

Bioplastics made from jellyfish are broken down in marine ecosystems in ways that depend strongly on environmental factors. Enzymes and microbes function better at certain temperatures and in tropical and temperate parts of the ocean, the warm temperatures lead to rapid degradation. Conversely, colder polar and deep-sea environments exhibit slower microbial activity, prolonging material persistence (Marques, 2020). Microbial communities and the stability of enzymes change with changes in salinity. Both halophilic and halotolerant microbes in salty domains have evolved to produce enzymes that break down marine biopolymers. Fluctuations in salinity within estuaries or coastal zones can therefore modulate biodegradation efficiency (Rezaei et al., 2025). Changes in how polymers swell, resulting from osmotic stress, may affect enzyme availability. Microbial community make-up, numbers and diversity matter. Collagenolytic bacteria such as Vibrio, Pseudoalteromonas, and Alteromonas, along with marine fungi, have been documented to degrade jellyfish biomolecules effectively (Rotter et al., 2024). Because microbes group together in biofilms, these areas are better for teamwork in breaking down pollutants. Nutrient availability, oxygen concentration, and competition also regulate microbial activity and succession on bioplastic surfaces (Oliva-Albert et al., 2025). Ultraviolet light, the chemical environment, motions of water and things like organic matter further affect how biological degradation occurs. UV can initiate photodegradation, fragmenting polymers and increasing microbial susceptibility, although excessive UV may inhibit microbial communities (Wang et al., 2015). Although both of these sediments can be mineralized, aerobic ones usually do this faster because they lack the anoxic conditions needed for other biochemical cycles. The breakdown of jellyfish bioplastics is controlled by a range of variables and depends on where and how it happens. Creating polymers that suit the marine environment in each region improves how fast they degrade and how safe they are for marine life.

5 Uses of jellyfish biosplastics in marine sectors

Due to their unusual features, bioplastics from jellyfish are promising for use in many marine industries. They use the fact that these materials are safer for the earth, stronger and can interact with living organisms to take the place of traditional, non-biodegradable plastic that pollutes the ocean. This section explains the important ways that marine bioplastics can be applied in packaging seafood, making gear used for fishing you can break in water, adding to sensors in the ocean and coming up with new ways to release agrichemicals in farming in the sea.

5.1 Seafood and aquaculture packaging

It is important that packaging for seafood and aquaculture maintains freshness, provides mechanical security and is environmentally safe. Conventional plastic packaging materials, such as polyethylene films and expanded polystyrene containers, contribute significantly to marine litter when discarded improperly (Gallo et al., 2018). Jellyfish-derived bioplastics offer an eco-friendly alternative due to their biodegradability in marine environments and ability to form transparent, flexible films with good barrier properties (Rotter et al., 2024). Collagen-based films derived from jellyfish exhibit favorable oxygen and moisture barrier characteristics, critical for inhibiting oxidation and microbial spoilage of seafood products during transportation and storage (Farooq et al., 2024). Moreover, their inherent biocompatibility and non-toxicity make them safe for direct food contact applications. These bioplastic films can be engineered with additives such as natural antioxidants and antimicrobials extracted from jellyfish mucus to extend shelf life and reduce food waste (Periyasamy et al., 2025). In the aquaculture industry, the use of biodegradable materials for packaging and transportation helps keep polluting substances at bay, even if accidental release happens. The compostability and marine degradability of jellyfish bioplastics ensure that lost or discarded packaging materials minimize long-term environmental accumulation (Datta et al., 2024).

5.2 Fishing gear and fishing nets that disintegrate in water

Fishing gear such as nets, lines, traps, and cages fabricated from synthetic plastics are major contributors to marine debris and ghost fishing phenomena, causing ecological damage and economic losses (Kozioł et al., 2022). Jellyfish-derived bioplastics provide a renewable and biodegradable material platform for manufacturing fishing gear that degrades after a defined service life, thereby mitigating these environmental impacts (Rotter et al., 2021). The mechanical strength and flexibility of collagen-based composites derived from jellyfish are sufficient to meet the demands of fishing nets and lines, while biodegradation ensures that lost gear does not persist indefinitely (Harussani et al., 2023). Crosslinking and polymer blending allow tuning of degradation rates to balance operational durability with environmental safety. Because biodegradable nets naturally disintegrate, they reduce ghost fishing which helps stop more accidental deaths of marine life.

Biofouling and the difficulty of dragging in boat nets can be reduced when conventional gear is coated with jellyfish-based biodegradable polymers. The addition of bioactive compounds inherent in jellyfish mucus may enhance anti-fouling properties, extending gear lifespan and reducing maintenance costs (Esparza-Espinoza et al., 2025). Adoption of jellyfish-based biodegradable gear aligns with emerging regulatory frameworks mandating reduction of marine plastic pollution and supports sustainable fisheries management (Edelist et al., 2021).

5.3 Marine sensors and devices constructed with bioplastic parts

The increasing deployment of sensor networks and monitoring devices in marine environments necessitates materials that minimize ecological footprint and withstand harsh conditions (Glaviano et al., 2022). Because jellyfish bioplastics are biodegradable and tough, they can be used as a novel covering or shell for sensors and gadgets in the ocean. Bioplastics can be engineered to provide protective coatings or housings that degrade harmlessly after device end-of-life, preventing accumulation of electronic waste in the oceans (Nomadolo and Muniyasamy, 2024). Additionally, collagen-based films possess optical transparency and flexibility desirable for sensor interfaces or wearable devices for marine animals (Farooq et al., 2024). Incorporation of jellyfish-derived bioactive molecules into sensor materials may enable self-cleaning surfaces resistant to biofouling, a major challenge impairing sensor performance. Research into integrating conductive nanomaterials with jellyfish bioplastics aims to develop biodegradable electronic components capable of sensing temperature, salinity, or chemical pollutants, thereby advancing marine environmental monitoring technologies (Pesterau et al., 2025).

5.4 Application of agrochemicals through controlled release is considered in marine farming

Marine aquaculture often requires precise delivery of nutrients, antibiotics, or pesticides to maintain healthy stock and optimize yields. Using traditional chemical delivery can add to pollution and encourage harmful substances to build up in the environment. Jellyfish-derived bioplastics can serve as biodegradable carriers for controlled release of agrochemicals, enabling targeted, sustained delivery in marine settings (Rotter et al., 2021).

Collagen and associated polysaccharides have properties that make it easier to put active ingredients into polymer or hydrogel materials. These matrices gradually degrade in seawater, releasing encapsulated agents in a controlled manner responsive to environmental triggers such as temperature or pH changes (She et al., 2025). By using such delivery systems, farmers can lower the use of chemicals, avoid problems with off-target effects and cut down on leftover pollution in marine sediments. Moreover, the bioactive components of jellyfish biomaterials may synergistically enhance antimicrobial efficacy or modulate immune responses in cultured organisms (Rigogliuso et al., 2023). Research into formulating jellyfish-based micro- and nano-carriers for aquaculture is ongoing, representing a promising direction toward sustainable marine farming practices (Duarte et al., 2022).

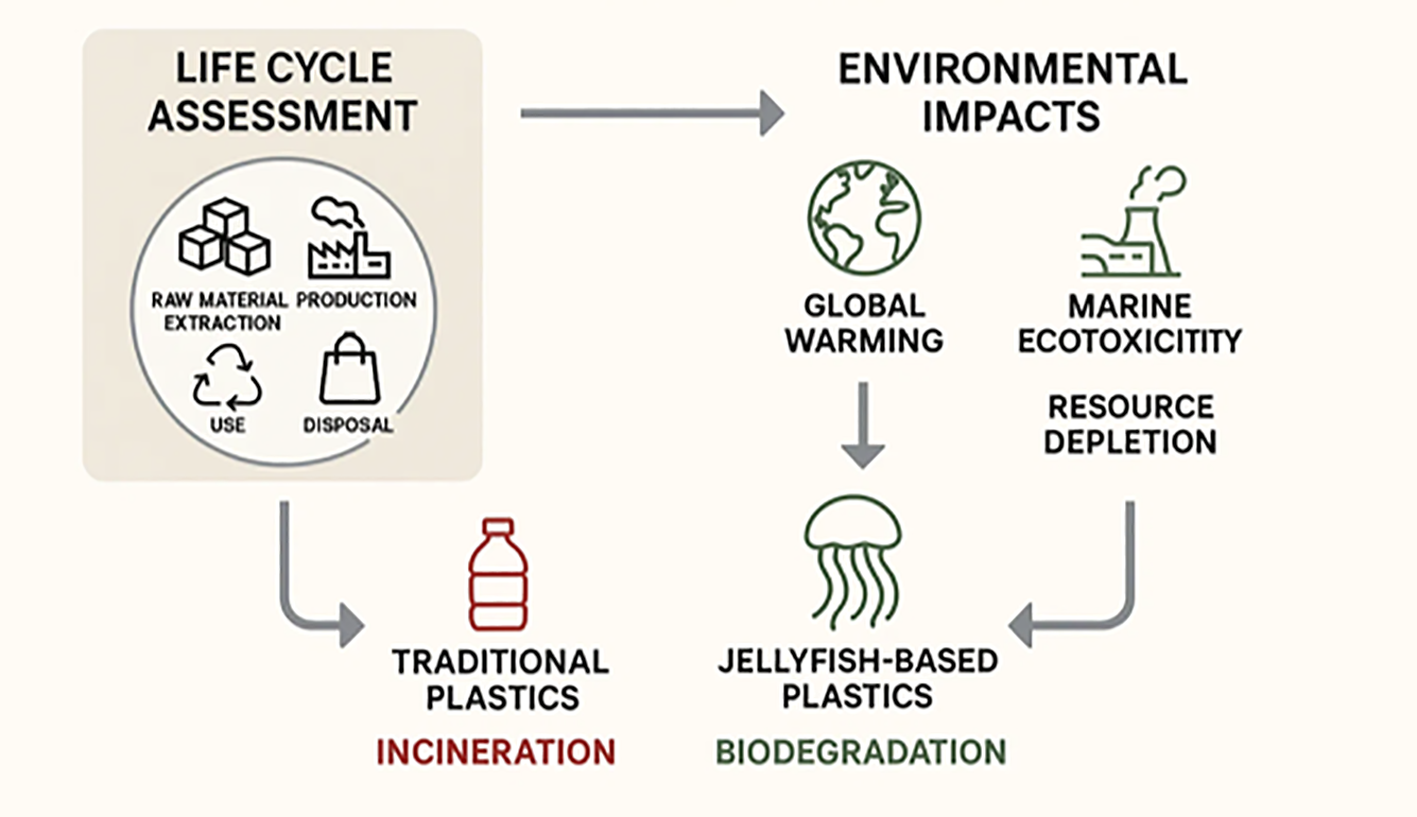

6 How green the project turns out

Checking how sustainably jellyfish bioplastics can be made is crucial to judge whether they are real replacements for regular plastics in water-based environments. The entire chain includes collecting the biomass from jellyfish, extracting its biopolymers, developing the bioplastics, using them and processing their breakdown. It is necessary to review these dimensions to guarantee that jellyfish bioplastics support the environment and reduce pollution in the oceans. This section elaborates on life cycle assessments (LCA) specific to jellyfish bioplastics, their potential to alleviate marine plastic pollution, and the challenges encountered in scaling production for commercial application (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Environmental impact and life cycle assessment of jellyfish-based plastics.

6.1 Examining all the steps of producing jellyfish bioplastic

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a comprehensive methodology used to evaluate the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product’s life. When studying jellyfish-derived bioplastics, LCA considers obtaining the jellyfish, processing them, making the bioplastics, distributing them, how they are used and how they will be disposed of or break down. Early LCA studies indicate that jellyfish bioplastics have a comparatively lower carbon footprint than petroleum-based plastics due to their renewable source and potential for low-energy extraction techniques (Olatunji, 2020). Harvesting jellyfish biomass often involves minimal input energy, especially when utilizing natural blooms that otherwise contribute to ecosystem imbalance (Graham et al., 2014). Extraction methods leveraging enzymatic processes and green solvents further reduce environmental burdens compared to chemical-intensive protocols. Even so, the amount of energy used in the final steps—purification, drying and turning the solution into a film can change the overall sustainability. Use of renewable energy sources and process optimization are therefore critical to enhancing environmental performance.

Materials used at the end of their products’ lives are expected to biodegrade and turn into minerals, so less plastic waste remains in landfill. Compared to conventional plastics, which often persist in environments for centuries, jellyfish-derived bioplastics decompose into non-toxic products under marine conditions, significantly reducing environmental persistence (Coppola et al., 2020). Nonetheless, comprehensive LCAs integrating marine degradation pathways and ecological effects remain limited, underscoring the need for further research to quantify real-world sustainability benefits.

6.2 Improving the prospects of reducing plastic found in the ocean

Being biodegradable, coming from nature and fitting marine needs, jellyfish bioplastics can play a key role in combating marine plastic pollution. Their rapid enzymatic breakdown in seawater decreases the accumulation of persistent plastic debris and microplastics, which are major threats to marine biodiversity and food security (Datta et al., 2024). By substituting conventional plastics in applications such as packaging, fishing gear, and aquaculture equipment, jellyfish bioplastics can directly lower the input of non-degradable materials into marine environments (Pagnotta, 2025). Moreover, utilization of jellyfish biomass harvested from blooms can transform an ecological challenge into a resource, promoting circular economy principles and ecosystem restoration (D’Ambra and Merquiol, 2022). Integration of jellyfish bioplastics into regulatory frameworks and industry standards aimed at marine pollution reduction can accelerate their adoption and contribute to global plastic waste management strategies. Getting people aware and encouraging policies will be key to shifting toward biodegradables from marine sources. Problems in making ideas work on a large scale and turning them into profitable businesses. Even with the benefits for the environment, several things stop jellyfish-based bioplastics from being produced on a large scale. Variability in jellyfish species composition, seasonal biomass availability, and geographic distribution complicate consistent raw material (Bastian et al., 2014). Efficient harvesting and processing technologies must be developed to enable cost-effective biomass collection without disrupting marine ecosystems (Sagarminaga et al., 2024).

In order to achieve the highest yield, purity and performance from plant materials, extraction and purification must be optimized to use as little energy and solvent as possible. Scaling enzymatic extraction and maintaining quality control pose technical hurdles that impact product consistency. Economic factors such as production costs, market demand, and competition with established petrochemical plastics influence commercial feasibility. Investment in research, infrastructure, and supply chain development is necessary to reduce costs and achieve economies of scale. Furthermore, regulatory uncertainties and lack of standardized certification for marine biodegradable plastics hinder market penetration. Robust ecotoxicological and lifecycle data are required to meet regulatory requirements and consumer expectations (Fletcher et al., 2021). Combining work from various fields, innovation and positive policies can fully exploit the green benefits of jellyfish bioplastics in ocean protection.

7 Suggestions for further study

Bioplastics made from jellyfish can only be fully adopted in marine settings if they improve in material science, biotech and by meeting regulations. Developing better qualities in jellyfish-based bioplastics is a major focus of today’s research. Jellyfish collagen is combined with other natural polymers to improve the strength, flexibility, sealing qualities and biodegradation of materials for a variety of usages, including packaging and marine devices. Chemical crosslinking biocompatible agents and adding bioactive molecules found in jellyfish mucus or nanocellulose or graphene oxide are ways to further improve the material, making it more durable, more active against microbes and more resistant to being fouled by marine organisms. Thus, these composites are expected to address weaknesses in pure jellyfish collagen and may be used more widely within the commercial sector. While working on material optimization, genetic and biotechnological approaches provide another way to boost jellyfish production and improve the process of collecting useful molecules. Improvements in marine genomics and synthetic biology allow researchers to find and handle genes that are important for collagen production and release in jellyfish. Biotechnology could let us increase the production or give added functions to collagen or bioactive substances. Growing jellyfish in special aquaculture conditions, improved by selective breeding and adjusting the environment, can give us a reliable and adjustable type of biomass. Making feasible microbial fermentation to produce recombinant or analog jellyfish collagen could transform the supply chain by ensuring steady and stable high-quality biopolymers.

The success and careful use of jellyfish-based marine bioplastics depend heavily on policy and regulations. Developing standard tests for biodegradability in the sea is necessary to confirm that some bioplastics do not harm the marine environment. Authorities and world organizations ought to create rules that encourage bioplastic research and at the same time monitor the environment and check for ecological safety. Likewise, using jellyfish bioplastics in wider efforts to reduce marine pollution such as asking producers to manage and own their products’ waste, can increase both adoption by industry and acceptance by the public. Talking with citizens and spreading information about the problem are important to help society move away from traditional plastics. Together, scientists, policymakers, industry and communities must join forces to solve technical, economic and social problems, allowing jellyfish bioplastics to fully help the world towards sustainability and save marine habitats.

8 Conclusion

Working with jellyfish-based bioplastics has shown great potential for dealing with many marine plastics and helping create new, sustainable products. The information covered in this review combines studies of jellyfish biochemistry, especially the presence of collagen, which makes turning jellyfish biomass into environmentally friendly plastics with suitable performance possible. Being strong, stable in hot conditions and considered safe, specially made plastics could eventually replace the commonly found plastic waste in the oceans. Biodegradation that is seen in seawater, thanks to the action of enzymes, points to how bioplastic can be environmentally sustainable and play a role in handling the ecological effects of plastic waste buildup over time. All the findings point to the importance of jellyfish-based bioplastics within the area of sustainable marine biotechnology.

There are major impacts for sustainable marine biotechnology. By utilizing jellyfish, we turn a harmful problem called jellyfish blooms into something useful and support blue economy ideas that help the environment thrive. Because jellyfish bioplastics are versatile, they are useful in many marine sectors such as seafood packaging, aquaculture, fishing gear and marine sensors which helps cut down on using synthetic plastics and their pollution. Using jellyfish compounds in the material makes the material easier to clean and helps prevent unwanted growth on surfaces which solves real issues found in marine environments. All of these qualities advance the efforts to care for nature and encourage innovation. At the same time, making the most of bioplastics from jellyfish calls for overcoming some essential obstacles. Different types of jellyfish and their uneven biomass lead to the need for dependable ways to farm or catch them sustainably. Improving the way extraction and processing are carried out is very important for gaining better yields, similar material each time and lower costs. Besides, performing detailed life cycle studies and toxicity evaluations adds proof to the environmental advantages and helps to build appropriate regulations. If maritime regulations encourage and recognize products with marine biodegradability, the market and responsible deployment can be helped. Future discoveries would benefit from connecting different fields such as material science, marine biology and environmental policy, to address current uncertainties in the field. Progress in genetic engineering and biotechnology could lead to increased biomolecule production and customizing new composite blends can be used for different application needs. In essence, jellyfish-based materials offer good prospects for the future in terms of sustainability and the economy. Their efforts mix several techniques such as using marine resources and developing biodegradable material, to reduce marine plastic pollution. Making strong investments in research, innovation and policy is necessary to turn these scientific breakthroughs into solutions that support and help marine ecosystems everywhere.

Statements

Author contributions

SJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Addad S. Exposito J.-Y. Faye C. Ricard-Blum S. Lethias C. (2011). Isolation, characterization and biological evaluation of jellyfish collagen for use in biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs9, 967–983. doi: 10.3390/md9060967

2

Ahmed Z. Powell L. C. Matin N. Mearns-Spragg A. Thornton C. A. Khan I. M. et al . (2021). Jellyfish collagen: A biocompatible collagen source for 3D scaffold fabrication and enhanced chondrogenicity. Mar. Drugs19, 405. doi: 10.3390/md19080405

3

Ahmed M. Verma A. K. Patel R. (2020). Collagen extraction and recent biological activities of collagen peptides derived from sea-food waste: A review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm.18, 100315. doi: 10.1016/j.scp.2020.100315

4

Al-Madboly L. A. Aboulmagd A. El-Salam M. A. Kushkevych I. El-Morsi R. M. (2024). Microbial enzymes as powerful natural anti-biofilm candidates. Microb. Cell Fact23, 343. doi: 10.1186/s12934-024-02610-y

5

Baksi S. Pal P. Baksi S. (2025). “ Green valorization protocols for marine food waste: collagen and chitin recovery,” in Food waste valorization: green techniques in sustainable management. Ed. SarkarT. ( Springer US, New York, NY), 359–383. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-4646-5_15

6

Balikci E. Baran E. T. Tahmasebifar A. Yilmaz B. (2024). Characterization of collagen from jellyfish aurelia aurita and investigation of biomaterials potentials. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.196, 6200–6221. doi: 10.1007/s12010-023-04848-5

7

Ballesteros A. Torres R. Pascual-Torner M. Revert-Ros F. Tena-Medialdea J. García-March J. R. et al . (2025). Jellyfish collagen in the mediterranean spotlight: transforming challenges into opportunities. Mar. Drugs23, 200. doi: 10.3390/md23050200

8

Bastian T. Lilley M. K. S. Beggs S. E. Hays G. C. Doyle T. K. (2014). Ecosystem relevance of variable jellyfish biomass in the Irish Sea between years, regions and water types. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci.149, 302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2014.08.018

9

Bhende P. P. Sharma A. Ganguly A. Bragança J. M. (2023). “ Marine environment: A treasure trove of natural polymers for tissue engineering,” in Marine bioactive molecules for biomedical and pharmacotherapeutic applications. Eds. Veera BramhachariP.BerdeC. V. ( Springer Nature, Singapore), 161–185. doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-6770-4_9

10

Bloom D. A. Radwan F. F. Y. Burnett J. W. (2001). Toxinological and immunological studies of capillary electrophoresis fractionated Chrysaora quinquecirrha (Desor) fishing tentacle and Chironex fleckeri Southcott nematocyst venoms. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C: Toxicol. Pharmacol.128, 75–90. doi: 10.1016/S1532-0456(00)00180-0

11

Bond T. Ferrandiz-Mas V. Felipe-Sotelo M. van Sebille E. (2018). The occurrence and degradation of aquatic plastic litter based on polymer physicochemical properties: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol.48, 685–722. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1483155

12

Cadar E. Pesterau A.-M. Sirbu R. Negreanu-Pirjol B. S. Tomescu C. L. (2023). Jellyfishes—Significant marine resources with potential in the wound-healing process: A review. Mar. Drugs21, 201. doi: 10.3390/md21040201

13

Cai Z. Li M. Zhu Z. Wang X. Huang Y. Li T. et al . (2023). Biological degradation of plastics and microplastics: A recent perspective on associated mechanisms and influencing factors. Microorganisms11, 1661. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11071661

14

Carneiro R. F. V. Nascimento N. R. F. Costa P. P. C. Gomes V. M. de Souza A. J. F. de Oliveira S. C. B. et al . (2011). The extract of the jellyfish Phyllorhiza punctata promotes neurotoxic effects. J. Appl. Toxicol.31, 720–729. doi: 10.1002/jat.1620

15

Cauduro V. H. Gohlke G. da Silva N. W. Cruz A. G. Flores E. M. (2025). A review on scale-up approaches for ultrasound-assisted extraction of natural products. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng.48, 101120. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2025.101120

16

Chia W. Y. Ying Tang D. Y. Khoo K. S. Kay Lup A. N. Chew K. W. (2020). Nature’s fight against plastic pollution: Algae for plastic biodegradation and bioplastics production. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology4, 100065. doi: 10.1016/j.ese.2020.100065

17

Coppola D. Oliviero M. Vitale G. A. Lauritano C. D’Ambra I. Iannace S. et al . (2020). Marine collagen from alternative and sustainable sources: extraction, processing and applications. Mar. Drugs18, 214. doi: 10.3390/md18040214

18

D’Ambra I. Merquiol L. (2022). Jellyfish from fisheries by-catches as a sustainable source of high-value compounds with biotechnological applications. Mar. Drugs20, 266. doi: 10.3390/md20040266

19

Datta D. Sarkar S. Biswas S. Mandal E. Das B. (2024). “ Valorization of marine waste towards the production of high-value-added products, bioplastics, and other industrial applications,” in Multidisciplinary applications of marine resources: A step towards green and sustainable future. Eds. RafatullahM.SiddiquiM. R.KhanM. A.KapoorR. T. ( Springer Nature, Singapore), 161–185. doi: 10.1007/978-981-97-5057-3_8

20

De Domenico S. De Rinaldis G. Mammone M. Bosch-Belmar M. Piraino S. Leone A. (2023). The zooxanthellate jellyfish holobiont cassiopea andromeda, a source of soluble bioactive compounds. Mar. Drugs21, 272. doi: 10.3390/md21050272

21

De Rinaldis G. Leone A. De Domenico S. Bosch-Belmar M. Slizyte R. Milisenda G. et al . (2021). Biochemical characterization of cassiopea andromeda (Forsskål 1775), another red sea jellyfish in the western mediterranean sea. Mar. Drugs19, 498. doi: 10.3390/md19090498

22

Diepens N. J. Koelmans A. A. (2018). Accumulation of plastic debris and associated contaminants in aquatic food webs. Environ. Sci. Technol.52, 8510–8520. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02515

23

Djeghri N. Pondaven P. Le Grand F. Bideau A. Duquesne N. Stockenreiter M. et al . (2021). High trophic plasticity in the mixotrophic Mastigias papua–Symbiodiniaceae holobiont: implications for the ecology of zooxanthellate jellyfishes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.666, 73–88. doi: 10.3354/meps13707

24

Duarte I. M. Marques S. C. Leandro S. M. Calado R. (2022). An overview of jellyfish aquaculture: for food, feed, pharma and fun. Rev. Aquaculture14, 265–287. doi: 10.1111/raq.12597

25

Edelist D. Angel D. L. Canning-Clode J. Gueroun S. K. M. Aberle N. Javidpour J. et al . (2021). Jellyfishing in europe: current status, knowledge gaps, and future directions towards a sustainable practice. Sustainability13, 12445. doi: 10.3390/su132212445

26

Esparza-Espinoza D. M. Rodríguez-Felix F. Santacruz-Ortega H. del C. Plascencia-Jatomea M. Salazar-Leyva J. A. et al . (2025). Development of jellyfish (Stomolophus sp. 2) gelatine–chitosan films: structural, physical, and antioxidant properties. Gels11, 836. doi: 10.3390/gels11100836

27

Farooq S. Ahmad M. I. Zheng S. Ali U. Li Y. Shixiu C. et al . (2024). A review on marine collagen: sources, extraction methods, colloids properties, and food applications. Collagen Leather6, 11. doi: 10.1186/s42825-024-00152-y

28

Fletcher C. A. Niemenoja K. Hunt R. Adams J. Dempsey A. Banks C. E. (2021). Addressing stakeholder concerns regarding the effective use of bio-based and biodegradable plastics. Resources10, 95. doi: 10.3390/resources10100095

29

Folino A. Karageorgiou A. Calabrò P. S. Komilis D. (2020). Biodegradation of wasted bioplastics in natural and industrial environments: A review. Sustainability12, 6030. doi: 10.3390/su12156030

30

Gallo F. Fossi C. Weber R. Santillo D. Sousa J. Ingram I. et al . (2018). Marine litter plastics and microplastics and their toxic chemicals components: the need for urgent preventive measures. Environ. Sci. Eur.30, 13. doi: 10.1186/s12302-018-0139-z

31

Geng X.-Y. Wang M.-K. Hou X.-C. Wang Z.-F. Wang Y. Zhang D.-Y. et al . (2024). Comparative analysis of tentacle extract and nematocyst venom: toxicity, mechanism, and potential intervention in the giant jellyfish nemopilema nomurai. Mar. Drugs22, 362. doi: 10.3390/md22080362

32

Glaviano F. Esposito R. Cosmo A. D. Esposito F. Gerevini L. Ria A. et al . (2022). Management and sustainable exploitation of marine environments through smart monitoring and automation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.10, 297. doi: 10.3390/jmse10020297

33

Graham W. M. Gelcich S. Robinson K. L. Duarte C. M. Brotz L. Purcell J. E. et al . (2014). Linking human well-being and jellyfish: ecosystem services, impacts, and societal responses. Front. Ecol. Environ.12, 515–523. doi: 10.1890/130298

34

Han Y. Weng Y. Zhang C. (2024). Development of biobased plasticizers with synergistic effects of plasticization, thermal stabilization, and migration resistance: A review. Vinyl Additive Technol.30, 26–43. doi: 10.1002/vnl.22048

35

Harussani M. M. Sapuan S. M. Iyad M. Wong H. K. A. Farouk Z. I. Nazrin A. (2023). “ Collagen based composites derived from marine organisms: as a solution for the underutilization of fish biomass, jellyfish and sponges,” in Composites from the aquatic environment. Ed. AhmadI. ( Springer Nature, Singapore), 245–274. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-5327-9_12

36

Islam J. Mis Solval K. E. (2025). Recent advancements in marine collagen: exploring new sources, processing approaches, and nutritional applications. Mar. Drugs23, 190. doi: 10.3390/md23050190

37

Jayaprakashvel M. Sami M. Subramani R. (2020). “ Antibiofilm, antifouling, and anticorrosive biomaterials and nanomaterials for marine applications,”,” in Nanostructures for antimicrobial and antibiofilm applications. Eds. PrasadR.SiddhardhaB.DyavaiahM. ( Springer International Publishing, Cham), 233–272. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-40337-9_10

38

Kozioł A. Paso K. G. Kuciel S. (2022). Properties and recyclability of abandoned fishing net-based plastic debris. Catalysts12, 948. doi: 10.3390/catal12090948

39

Kumar R. Verma A. Shome A. Sinha R. Sinha S. Jha P. K. et al . (2021). Impacts of plastic pollution on ecosystem services, sustainable development goals, and need to focus on circular economy and policy interventions. Sustainability13, 9963. doi: 10.3390/su13179963

40

Li P. Zhang J. Liu X. Xu Z. Zhang X. Ma J. et al . (2025). Frontiers in bioinspired polymer-based helical nanofibers from electrospinning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces17, 26156–26177. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5c04110

41

Lian M. Zheng F. Lu X. Lu Q. (2019). Tuning the heat resistance properties of polyimides by intermolecular interaction strengthening for flexible substrate application. Polymer173, 205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2019.04.032

42

Liu X. Zhang M. Jia A. Zhang Y. Zhu H. Zhang C. et al . (2013). Purification and characterization of angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum. Food Res. Int.50, 339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.11.002

43

Ma Y. Yu H. Teng L. Geng H. Li R. Xing R. et al . (2024). NnM469, a novel recombinant jellyfish venom metalloproteinase from Nemopilema nomurai, disrupted the cell matrix. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules281, 136531. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136531

44

Malej A. Faganeli J. Pezdič J. (1993). Stable isotope and biochemical fractionation in the marine pelagic food chain: the jellyfish Pelagia noctiluca and net zooplankton. Mar. Biol.116, 565–570. doi: 10.1007/BF00355475

45

Marino A. Morabito R. Pizzata T. La Spada G. (2008). Effect of various factors on Pelagia noctiluca (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa) crude venom-induced haemolysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol.151, 144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.06.013

46

Marques L. (2020). “ Collapse of biodiversity in the aquatic environment,” in Capitalism and environmental collapse. Ed. MarquesL. ( Springer International Publishing, Cham), 275–301. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-47527-7_11

47

Mohanan N. Montazer Z. Sharma P. K. Levin D. B. (2020). Microbial and enzymatic degradation of synthetic plastics. Front. Microbiol.11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.580709

48

Nomadolo N. Muniyasamy S. (2024). “ End-of-life options of biobased plastic materials,” (Biodegradable Polymers, Blends and Biocomposites. (Boca Raton: CRC Press). doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.153638

49

Olatunji O. (2020). Aquatic biopolymers: understanding their industrial significance and environmental implications (Cham: Springer International Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-34709-3

50

Oliva-Albert M. Bellostas-Carreras A. Guijosa-Ortega J. L. Doménech-Pascual A. Boadella J. Casas-Ruiz J. P. et al . (2025). Microbial colonization and function of biofilms developing on plastics and bioplastics in a pristine mountain stream ecosystem. Limnology Oceanography70, 2239–2255. doi: 10.1002/lno.70107

51

Pagnotta L. (2025). Sustainable netting materials for marine and agricultural applications: A perspective on polymeric and composite developments. Polymers (Basel)17, 1454. doi: 10.3390/polym17111454

52

Periyasamy T. Asrafali S. P. Lee J. (2025). Recent advances in functional biopolymer films with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties for enhanced food packaging. Polymers17, 1257. doi: 10.3390/polym17091257

53

Pesterau A.-M. Popescu A. Sirbu R. Cadar E. Busuricu F. Dragan A.-M. L. et al . (2025). Marine jellyfish collagen and other bioactive natural compounds from the sea, with significant potential for wound healing and repair materials. Mar. Drugs23, 252. doi: 10.3390/md23060252

54

Pivnenko T. N. Kovalev A. N. Pozdnyakova Yu. M. Esipenko R. V. (2022). The Composition of Collagen-Containing Preparations from Rhopilema asamushi Uchida Jellyfish and Assessment of the Safety of their External Use. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol.58, 864–872. doi: 10.1134/S0003683822070043

55

Qiu Q. Gu Y. Ren Y. Ding H. Hu C. Wu D. et al . (2024). Research progress on eco-friendly natural antifouling agents and their antifouling mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J.153638, 495. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.153638

56

Rastogi A. Sarkar A. Chakrabarty D. (2017). Partial purification and identification of a metalloproteinase with anticoagulant activity from Rhizostoma pulmo (Barrel Jellyfish). Toxicon132, 29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.04.006

57

Rezaei Z. Amoozegar M. A. Moghimi H. (2025). Innovative approaches in bioremediation: the role of halophilic microorganisms in mitigating hydrocarbons, toxic metals, and microplastics in hypersaline environments. Microb. Cell Fact24, 184. doi: 10.1186/s12934-025-02817-7

58

Rigogliuso S. Campora S. Notarbartolo M. Ghersi G. (2023). Recovery of bioactive compounds from marine organisms: focus on the future perspectives for pharmacological, biomedical and regenerative medicine applications of marine collagen. Molecules28, 1152. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031152

59

Rodrigues T. Barroso R. A. Campos A. Almeida D. Guardiola F. A. Turkina M. V. et al . (2025). Unveiling the bioactive potential of the invasive jellyfish phyllorhiza punctata through integrative transcriptomic and proteomic analyses. Biomolecules15, 1121. doi: 10.3390/biom15081121

60

Rotter A. Barbier M. Bertoni F. Bones A. M. Cancela M. L. Carlsson J. et al . (2021). The essentials of marine biotechnology. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.629629

61

Rotter A. Varamogianni-Mamatsi D. Pobirk A. Z. Matjaž M. G. Cueto M. Díaz-Marrero A. R. et al . (2024). Marine cosmetics and the blue bioeconomy: From sourcing to success stories. iScience27, 12111339. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.111339

62

Sagarminaga Y. Piraino S. Lynam C. P. Leoni V. Nikolaou A. Jaspers C. et al . (2024). Management of jellyfish outbreaks to achieve good environmental status. Front. Ocean Sustain.2. doi: 10.3389/focsu.2024.1449190

63

Samalens F. Thomas M. Claverie M. Castejon N. Zhang Y. Pigot T. et al . (2022). Progresses and future prospects in biodegradation of marine biopolymers and emerging biopolymer-based materials for sustainable marine ecosystems. Green Chem.24, 1762–1779. doi: 10.1039/D1GC04327G

64

Shafqat A. Tahir A. Mahmood A. Tabinda A. B. Yasar A. Pugazhendhi A. (2020). A review on environmental significance carbon foot prints of starch based bio-plastic: A substitute of conventional plastics. Biocatalysis Agric. Biotechnol.27, 101540. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101540

65

She J. Liu J. Mu Y. Lv S. Tong J. Liu L. et al . (2025). Recent advances in collagen-based hydrogels: Materials, preparation and applications. Reactive Funct. Polymers207, 106136. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2024.106136

66

Sipos J. C. Ackman R. G. (1968). Jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) lipids: fatty acid composition. J. Fish. Res. Bd. Can.25, 1561–1569. doi: 10.1139/f68-141

67

Stabili L. Rizzo L. Fanizzi F. P. Angilè F. Del Coco L. Girelli C. R. et al . (2019). The jellyfish rhizostoma pulmo (Cnidaria): biochemical composition of ovaries and antibacterial lysozyme-like activity of the oocyte lysate. Mar. Drugs17, 17. doi: 10.3390/md17010017

68

Steinberger L. R. Gulakhmedova T. Barkay Z. Gozin M. Richter S. (2019). Jellyfish-based plastic. Advanced Sustain. Syst.3, 1900016. doi: 10.1002/adsu.201900016

69

Su L. Feng Y. Wei K. Xu X. Liu R. Chen G. (2021). Carbohydrate-based macromolecular biomaterials. Chem. Rev.121, 10950–11029. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01338

70

Thushari G. G. N. Senevirathna J. D. M. (2020). Plastic pollution in the marine environment. Heliyon6, 8e04709. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04709

71

Tinta T. Kogovšek T. Klun K. Malej A. Herndl G. J. Turk V. (2019). Jellyfish-associated microbiome in the marine environment: exploring its biotechnological potential. Mar. Drugs17, 94. doi: 10.3390/md17020094

72

Vieira M. G. A. da Silva M. A. dos Santos L. O. Beppu M. M. (2011). Natural-based plasticizers and biopolymer films: A review. Eur. Polymer J.47, 254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2010.12.011

73

Vieira Veríssimo N. Ussemane Mussagy C. Alves Oshiro A. Nóbrega Mendonça C. M. Carvalho Santos-Ebinuma V. de Pessoa A. et al . (2021). From green to blue economy: Marine biorefineries for a sustainable ocean-based economy. Green Chem.23, 9377–9400. doi: 10.1039/D1GC03191K

74

Wang J. Liu L. Wang X. Chen Y. (2015). The interaction between abiotic photodegradation and microbial decomposition under ultraviolet radiation. Global Change Biol.21, 2095–2104. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12812

75

Wu X. Liu P. Zhao X. Wang J. Teng M. Gao S. (2022). Critical effect of biodegradation on long-term microplastic weathering in sediment environments: A systematic review. J. Hazardous Materials437, 129287. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129287

76

Xia W.-X. Li H.-R. Ge J.-H. Liu Y.-W. Li H.-H. Su Y.-H. et al . (2021). High-continuity genome assembly of the jellyfish Chrysaora quinquecirrha. Zool Res.42, 130–134. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.258

77

Yao X. Yang X. Lu Y. Qiu Y. Zeng Q. (2025). Review of the synthesis and degradation mechanisms of some biodegradable polymers in natural environments. Polymers17, 66. doi: 10.3390/polym17010066

78

Yorke S. K. Yang Z. Wiita E. G. Kamada A. Knowles T. P. Buehler M. J. (2025). Design and sustainability of polypeptide material systems. Nat. Rev. Materials1–19, 750–768. doi: 10.1038/s41578-025-00793-3

79

Zhang H. Wang Q. Xiao L. Zhang L. (2017). Intervention effects of five cations and their correction on hemolytic activity of tentacle extract from the jellyfish Cyanea capillata. PeerJ5, e3338. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3338

80

Zhang X. Xu S. Shen L. Li G. (2020). Factors affecting thermal stability of collagen from the aspects of extraction, processing and modification. J. Leather Sci. Eng.2, 19. doi: 10.1186/s42825-020-00033-0

81

Zhang X. Yin Z. Xiang S. Yan H. Tian H. (2024). Degradation of polymer materials in the environment and its impact on the health of experimental animals: A review. Polymers (Basel)16, 2807. doi: 10.3390/polym16192807

Summary

Keywords

jellyfish bioplastics, marine biodegradation, collagen extraction, sustainable materials, marine pollution mitigation, biodegradable fishing gear, aquaculture applications

Citation

Jeyachandran S and Aman M (2026) Jellyfish-derived bioplastics: properties, degradation, and marine applications. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1666791. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1666791

Received

15 July 2025

Revised

25 November 2025

Accepted

08 December 2025

Published

02 February 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Meivelu Moovendhan, Saveetha Medical College & Hospital, India

Reviewed by

Zahra Rajabimashhadi, University of Salento, Italy

Hind Mkadem, Agronomic and Veterinary Institute Hassan II, Morocco

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Jeyachandran and Aman.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sivakamavalli Jeyachandran, sivakamavalli.sdc@saveetha.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.