Abstract

Introduction:

Coral reefs are essential ecosystems facing severe global decline due to various environmental stressors. Understanding coral resilience and adaptability is critical for their conservation.

Methods:

We examined the microbial communities associated with the scleractinian coral Favia fragum in both mangrove and adjacent reef habitats in the Panamanian Caribbean.

Results:

Our results reveal that F. fragum colonies in mangrove habitats at different sites share similar microbial communities, distinct from those in adjacent reef habitats. Notably, certain bacterial lineages, including Cyanobacteria and Hyphomicrobiales, are enriched in mangrove-associated corals, suggesting potential roles in carbon and nitrogen cycling. Conversely, the family Vibrionaceae, which includes known coral pathogens, is more abundant in reef habitats.

Discussion:

These findings emphasize the significance of microbial communities in coral resilience and highlight the complex interplay between corals and microbial symbionts across different habitats. Protecting mangroves, which serve as nurseries for coral biodiversity, is crucial for overall reef health in the face of global coral decline.

Introduction

Coral reefs are experiencing a significant decline in abundance and biodiversity worldwide due to various local and global factors, such as global oceanic warming, pollution, habitat degradation, and fragmentation (Knowlton, 2001. Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). The loss of coral reefs is a major concern, as they provide important ecosystem services, including habitat, coastal protection, and tourism (Knowlton, 2001). It is estimated that coral reefs have declined, not only in abundance but also in their ability to provide ecosystem services by 50% since 1950 (Eddy et al., 2021). Human activities can negatively impact corals locally, reducing their resilience to global stressors (Knowlton, 2001). However, some coral populations are thriving through adaptation and acclimatization to new environmental conditions, or due to resilient life strategies. For example, positive interactions between corals and thermally resistant symbionts have been identified as a key factor in coral success in adapting to anthropogenic climate change (Howells et al., 2020).

Among resilient corals, brooding species also exhibit traits such as asexual larval reproduction, high fecundity, rapid growth rates, limited dispersal, and a strong tendency for philopatry. These traits, initially predicted by Knowlton (2001) and since observed (Green et al., 2008; Burgess et al., 2021), have allowed brooding corals to maintain their abundance, albeit with an increase in relative abundance, while other reef corals decline from bleaching events, storm damage or other anthropogenic effects. The prevalent traits of brooding corals contribute to their ability to quickly adapt to new environments and their resilience in the face of stressors (van Oppen et al., 2015). In addition to brooding offspring, Darling et al. (2012) classified F. fragum as a “stress-tolerant” species based on a cluster analysis of 11 life-history traits. A principal components ordination (Darling et al., 2012) revealed that F. fragum is also quite similar to “weedy” species due to its morphology, high fecundity, and brooding capacity, while being distinct from “competitive” corals that have larger colony sizes and branching morphologies. Stress-tolerant corals found in thermally variable intertidal zones can recover from bleaching events faster than “weedy” and “competitive” corals, which dominate subtidal reefs that exhibit less thermal variation (Speelman et al., 2023) Studying coral species with reproductive modes and life history strategies that promote fast adaptation and acclimatization to novel and different environments increases our ability to identify important mechanisms in coral reef ecology and evolution that can inform more effective conservation strategies.

The global decline in corals underscores the importance of studying populations engaged in positive interactions with other species to understand how those relationships can benefit coral reefs. In the Caribbean, there is growing evidence that corals benefit from their association with mangrove forests (Rogers and Herlan, 2012; Rogers, 2017; Kellogg et al., 2020; Stewart et al., 2021, 2022). Mangrove forests are highly productive coastal ecosystems that provide a range of ecosystem services and act as a refuge for many marine organisms. The marine habitats beneath mangrove forests are characterized by unique environmental conditions, including reduced light from the dense canopy, increased turbidity, and high nutrient loads from terrestrial runoff (Feller et al., 2003). These factors create an environment that is distinct from traditional coral reefs, providing a potential buffer from global stressors affecting coral reefs.

The potential role of mangroves as coral refugia (Stewart et al., 2021) has prompted coral biologists to compare corals associated with mangroves with those inhabiting traditional coral reef ecosystems, particularly in light of the substantial disparities in environmental conditions and phenotypes between these habitats (Lord et al., 2021). Novel interactions between corals and other organisms that ecologically interact with mangroves, such as commensals, symbionts, and pathogens, can arise from novel associations between corals and mangroves (Wright et al., 2023). Furthermore, current relationships with important herbivores that spend part of their lifetime in mangroves can be altered. For example, Parrotfishes are highly abundant in habitats with mangrove-associated corals (Wright et al., 2023). Juvenile rainbow parrotfish, Scarus guacamaia, live exclusively in mangrove habitats, and are crucial herbivores of coral reefs as adults (Mumby et al., 2004).

The well-being of all organisms is connected to their microbial communities (Freeman and Thacker, 2011; Berendsen et al., 2012; Clemente et al., 2012; Haney et al., 2015; Kelly et al., 2021; Bosch and McFall-Ngai, 2011), otherwise known as microbiomes, which vary with phylogenetic history, location, and environmental conditions (Ritchie, 2006; Sunagawa et al., 2010; Marino et al., 2017; Easson et al., 2020). The decline of coral reefs worldwide has resulted in extensive research on the role and diversity of microbes associated with coral reefs (Thompson et al., 2015; van Oppen and Blackall, 2019). This microbial diversity includes pathogens such as Vibrio corallyticus, V. charchariae, and V. harveyi, which are associated with coral diseases in the tropics (Brown et al., 2013; Ritchie and Smith, 1998; Gignoux-Wolfsohn and Vollmer, 2015; Luna et al., 2010). The taxonomic composition and abundance of these microbes are crucial to the host’s metabolism, as they supply and cycle nutrients, and are also correlated with important body functions of corals such as disease resistance, growth rates, post-disturbance survival, thermal tolerance, and even reproduction (Thompson et al., 2015). The assembly of coral microbiomes is a complex process that is host-specific and can vary with changes in the environment (Mohamed et al., 2025; Ziegler et al., 2019; Pollock et al., 2018).

Favia fragum (Esper, 1797) the golfball coral, is a small hermaphroditic brooder with short to medium dispersal and high philopatry (Carlon and Lippe, 2008). It is one of the few coral species that can and primarily self-fertilize its progeny, as 80-99% of its progeny is self-fertilized (Carlon and Lippe, 2011). Like most other brooding corals, F. fragum vertically transmits photosynthetic symbionts and other microbes to their offspring (Baird et al., 2009; Carlon and Lippe, 2008). F. fragum inhabits a wide range of environments, from reefs (15m depth) to shallow roots (<0.2m depth) on the fringes of mangrove forests. While all scleractinian corals are listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), this particular species is not categorized as endangered or threatened because of its rapid rate of growth and early age of reproduction (Hoeksema et al., 2012). Consequently, the removal of entire colonies for microbiome analysis imposes less strain on local communities than the potential damage to long-lived, slow-growing colonies that have existed for thousands of years and serve as vital habitats for numerous other species.

Evaluating potential differences in microbial communities between corals living on coral reefs and mangrove roots is an important step towards understanding how corals interact with mangrove ecosystems. We hypothesized that changes in the F. fragum microbiome are necessary for this coral to acclimate to living under mangrove canopies. In this study, we assessed differences in microbial communities between corals living on coral reefs and mangrove roots by testing the hypothesis that site and habitat impact the community structure of coral microbiomes.

Materials and methods

The Archipelago of Bocas del Toro, Panama offers many occurrences of mangrove forests in close proximity to coral reefs (Stewart et al., 2021, 2022). We hand-collected tissue samples from 38 colonies of F. fragum in Bahia Almirante from two sites with adjacent mangrove forest fringe and conventional reef habitats between June and July 2018. All collected colonies were of the same morphotype (Morphotype 1, as in Carlon and Budd, 2002). Reef specimens were collected from the forereef at both sites, although the topography of Bocas del Toro reefs is unusual and results in ecotonal transitions and overlapping mangrove, seagrass, and coral reef habitats at some sites (Collin, 2005; Guzman et al., 2005). The two sites were approximately 10 km apart and varied in the proximity between habitats: habitats at STRI point were ~200m apart, whereas habitats at Coral Cay had a separation of over 1km (Figure 1). Colonies of F. fragum were collected at comparable depths within each habitat type across sites. At Coral Cay reef, colonies were sampled between 3.7-4.9m depth, whereas STRI reef colonies were found between 3.0-6.1m depth due to a steep reef slope. Coral Cay mangrove colonies occurred between 0.3-2.4m depth, while STRI mangrove colonies were found between 0.3-3.0m. The distances between collected colonies varied notably between sites. At STRI, colonies were situated only a few centimeters to less than 300 m apart, while at Coral Cay, colonies were separated by distances ranging from a few centimeters to more than 1 km. We removed whole polyps with skeletal material from the perimeter of each colony with dissection tools and bone-cutting shears, stored in 95% ethyl alcohol, and exported them to Stony Brook University for DNA extraction and library preparation.

Figure 1

Map (A) and satellite imagery (B, C) of sites sampled. The map denotes the spatial distribution of the two sites. Satellite imagery of each site, namely STRI (B), and Coral Cay (C) visually represent the spatial distribution of habitats within each site. Teal polygons delineate the sampling areas within each site for reef habitats, while brown polygons represent the sampled areas within mangrove habitats.

Sample processing and DNA sequencing

We extracted DNA from collected samples using the DNeasy PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions with some modifications. We amplified the V4 region of the 16s rRNA gene from extracted DNA following the Earth Microbiome Project protocol (Thompson et al., 2017) using the primers 515f (5’ GTG YCA GCM GCC GCG GTA A 3’) and 806rB (5’ GGA CTA CNV GGG TWT CTA AT 3’; Apprill et al., 2015). We conducted Polymerase Chain Reactions in 50uL volumes, with 25uL of GoTaq Master Mix with 3mM MgCl2 (Promega, Madison WI), 19uL of Nuclease-free water, 2uL of each of the primers at 10uM concentration, and 2uL of template DNA. Thermocycler conditions entailed an initial denaturing step at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of the following steps: 94°C for 45 seconds, 50°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 90 seconds. The last step for elongation was set at 72°C for 10 minutes. We multiplexed amplicon libraries using 12bp Golay barcodes by quantifying nucleotide concentrations for each library using a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and pooling all libraries equimolarly. The Biotechnology Resource Center (BRC) Genomics Facility (RRID: SCR_021727) at the Cornell Institute of Biotechnology performed BluePippin DNA size selection and sequencing of the amplicon libraries using a Nano 2x250bp kit on an Illumina MiSeq.

DNA sequence and community data analysis and visualization

We used Trimmomatic v0.39 (Bolger et al., 2014) to trim low-quality ends of all reads of the pooled amplicon libraries using the following parameters: TRAILING:15 SLIDINGWINDOW:5:15 MINLEN:100. Next, we demultiplexed and trimmed adapters from the trimmed reads using Cutadapt v4.1 (Martin, 2011). We performed further quality control steps using the DADA2 pipeline v1.22.0 (Callahan et al., 2016), including the removal of chimeric sequences, as well as the taxonomic inference of operational taxonomic units (OTU) in Rstudio v4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021). We aligned sequences and generated a distance matrix using DECIPHER v2.22.0 (Wright, 2016). Based on the distance matrix, we used phangorn v2.8.1 (Schliep, 2011) to reconstruct a rooted tree with unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA). We used the command “tree_glom()” in the package speedyseq v. 0.5.3.9018 (McLaren, 2022) to agglomerate microbial variants identified as unique by the DADA2 pipeline based on phylogenetic distances at a resolution of 0.05, thus generating OTUs based on 90% sequence similarity. We utilized the SILVA database version 138.2 (Quast et al., 2012) for taxonomic inference.

We analyzed and visualized microbial communities by using the packages Phyloseq v1.38.0 (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013), vegan v2.5-7 (Oksanen et al., 2025), microbiome v1.16.0 (Lahti and Shetty, 2017), and microbiomeutilities v1.00.17 (Shetty and Lahti, 2023). We used a Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) on Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity Indices between microbial communities of Favia fragum from mangrove and reef habitats at both sites to visualize patterns of similarity and dissimilarity between habitats. A PERMANOVA (adonis2) tested differences between habitats and sites in microbial communities. We confirmed homogeneity in dispersion between groups by using a Permutation test under the vegan package. A Linear Discriminant Analysis with Effect Size (LEfSe) under the package microbiomeMarker v1.0.2 (Cao et al., 2022) determined statistically significant biomarkers (Segata et al., 2011) enriched in each habitat. Finally, we generated an unrooted bacterial tree to visualize differences in the abundance of all the bacterial lineages present across all samples using the package metacoder v0.3.6 (Foster et al., 2017).

Results

The sequencing run generated 1.02 million reads, with 715,636 (69.6%) containing Golay barcodes. After quality filtering and removal of chimeric sequences, a total of 245,603 (23.9%) high-quality reads were retained for downstream analysis. The DADA2 pipeline identified 4,771 unique OTUs across all 38 samples, of which 1,000 variants were classified as chloroplasts or mitochondria and were removed, resulting in a total of 3,771 unique prokaryotic microbe sequences across all samples. Due to the low number of reads, quantified as less than 1% of the total number of reads that passed filters, sample CC10 was excluded from the analysis, leaving a final dataset of 568 microbial variants after agglomerating OTUs based on phylogenetic distances.

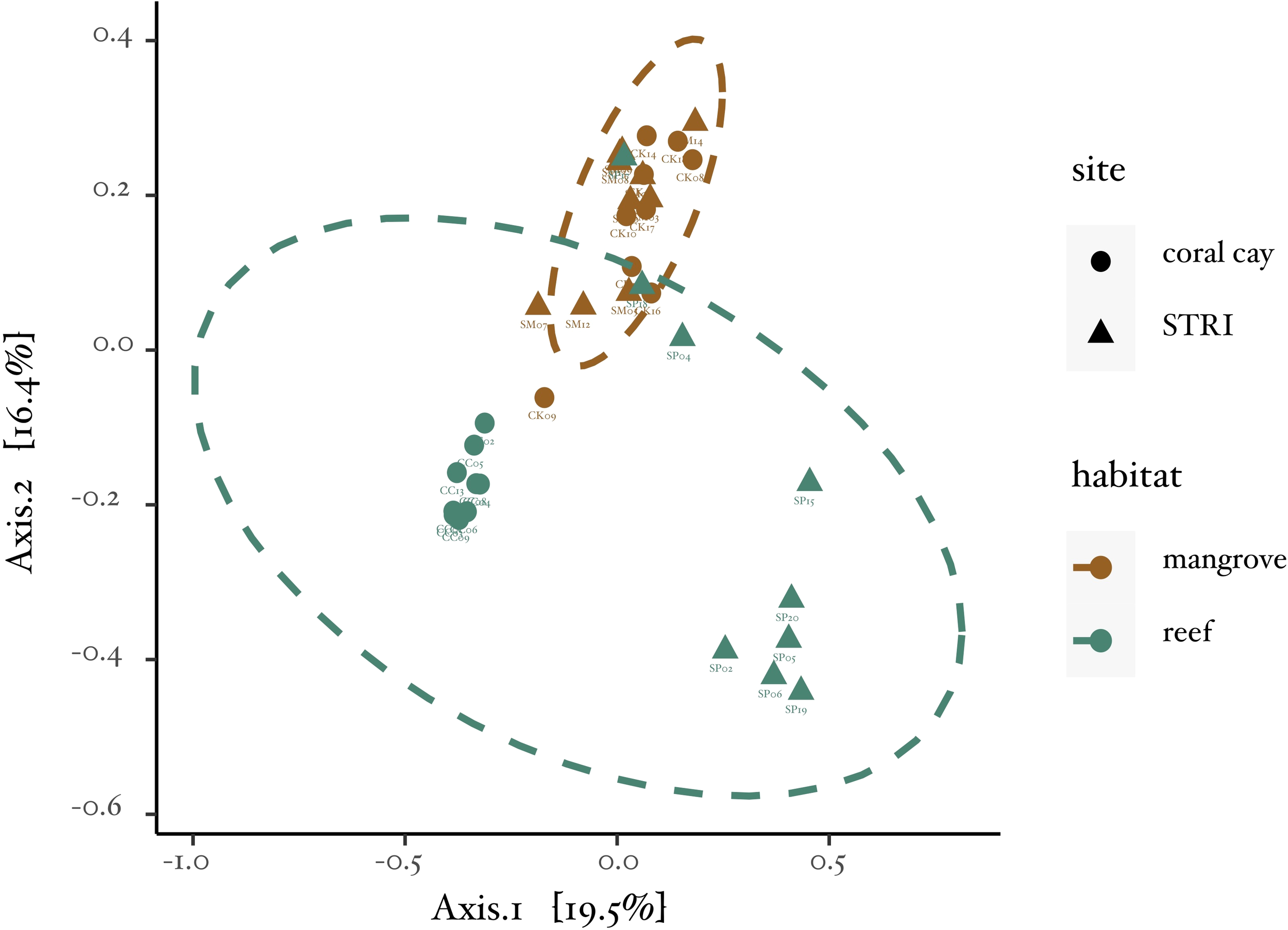

The microbiomes of golfball corals in mangrove and reef habitats at both sites exhibited clear clustering (Figure 2), indicating distinct microbiome composition between these habitats. The assumptions of the PERMANOVA were confirmed through testing for differences in dispersion and homogeneity between groups (Permutest: df = 1, F = 0.75, P-value = 0.41). The PERMANOVA identified significant differences between habitats (adonis2: df = 1, F = 5.47, R2 = 0.12, P-value < 0.001), sites (adonis2: df = 1, F = 3.96, R2 = 0.08, P-value < 0.001), and a significant interaction between habitat and site (adonis2: df = 1, F = 5.10, R2 = 0.11, P-value < 0.001). Notably, some specimens from the STRI reef site displayed overlapping microbiome composition with specimens from the mangroves (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) ordination plot. Representation of Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity Indices between all samples. The plot visually captures the relationships and clustering patterns among the samples based on their compositional differences.

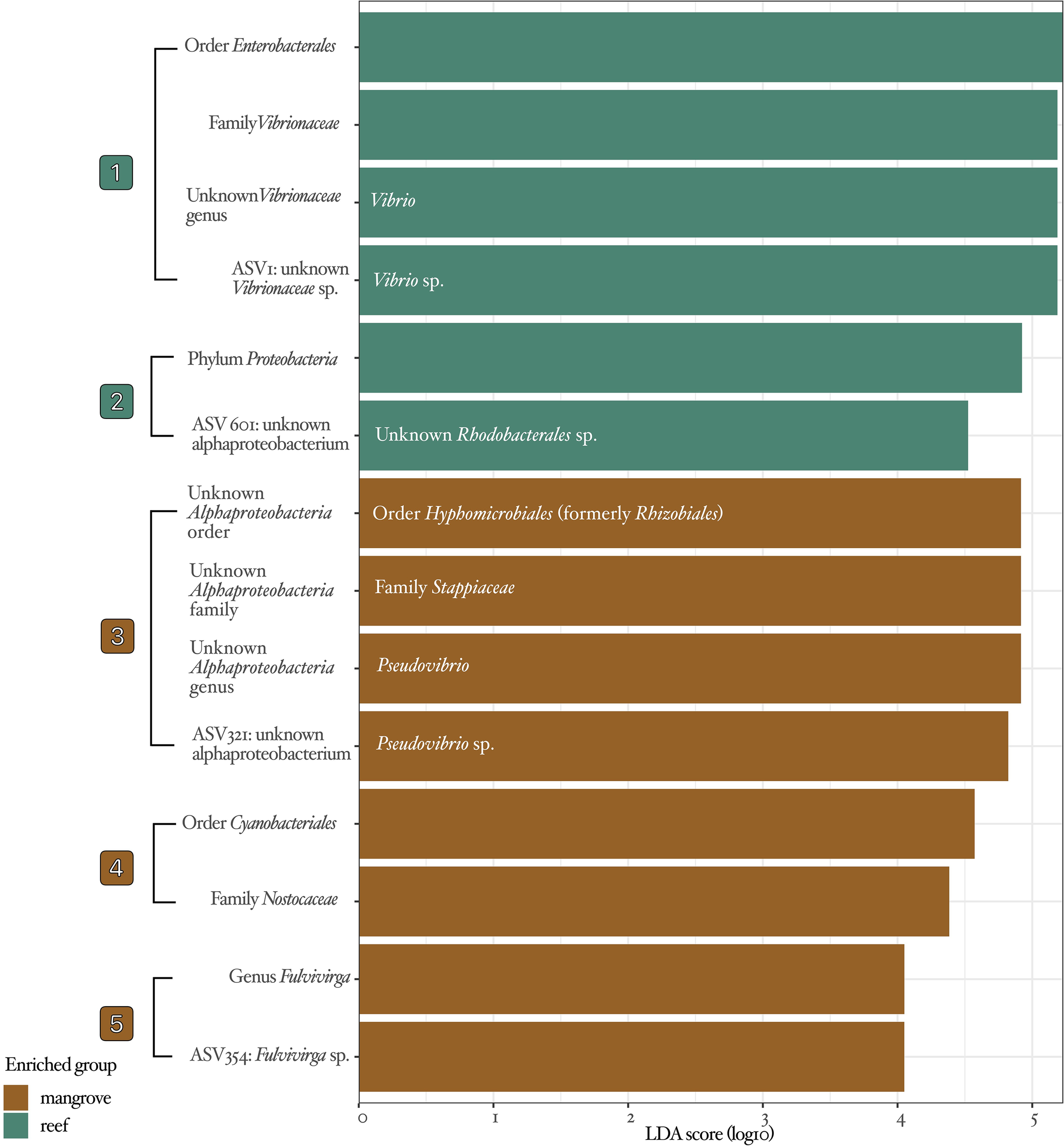

Of the 568 variants, 215 were unique to mangrove habitats, 179 were unique to reef habitats, and 174 were found in both. The LEfSe identified five bacterial lineages that were significantly associated with a particular habitat, with two lineages enriched in reef habitats and three lineages enriched in mangrove habitats (Figure 3). Of the five lineages identified as biomarkers, four included bacterial variants. Sequences of variants that were unable to be assigned taxonomy by the DADA2 pipeline were inferred based on the classification of the top 100 matches in the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). For instance, OTU321 was classified as an unknown alphaproteobacterium, but all of the top 100 matches in BLAST to that variant’s sequence were of cultured and uncultured bacteria in the genus Pseudovibrio, hence, it was classified as Pseudovibrio sp. (white text within bars, Figure 3).

Figure 3

LEfSe analysis results. Bar plots illustrate the effect size of individual taxonomic features in elucidating abundance variations between habitats. Teal bars indicate taxonomic features enriched in reef habitats, while brown bars represent lineages enriched in mangrove habitats. The taxonomic identifications from the DADA2 pipeline using the SILVA database are shown in black text to the left of bars. Improvements in taxonomic identification for unknown taxa were performed via BLAST and are included in white text within the bars. Numbers next to brackets summarize the five lineages identified as biomarkers, which will be further visualized in Figure 4 on an unrooted bacterial tree of differential abundance.

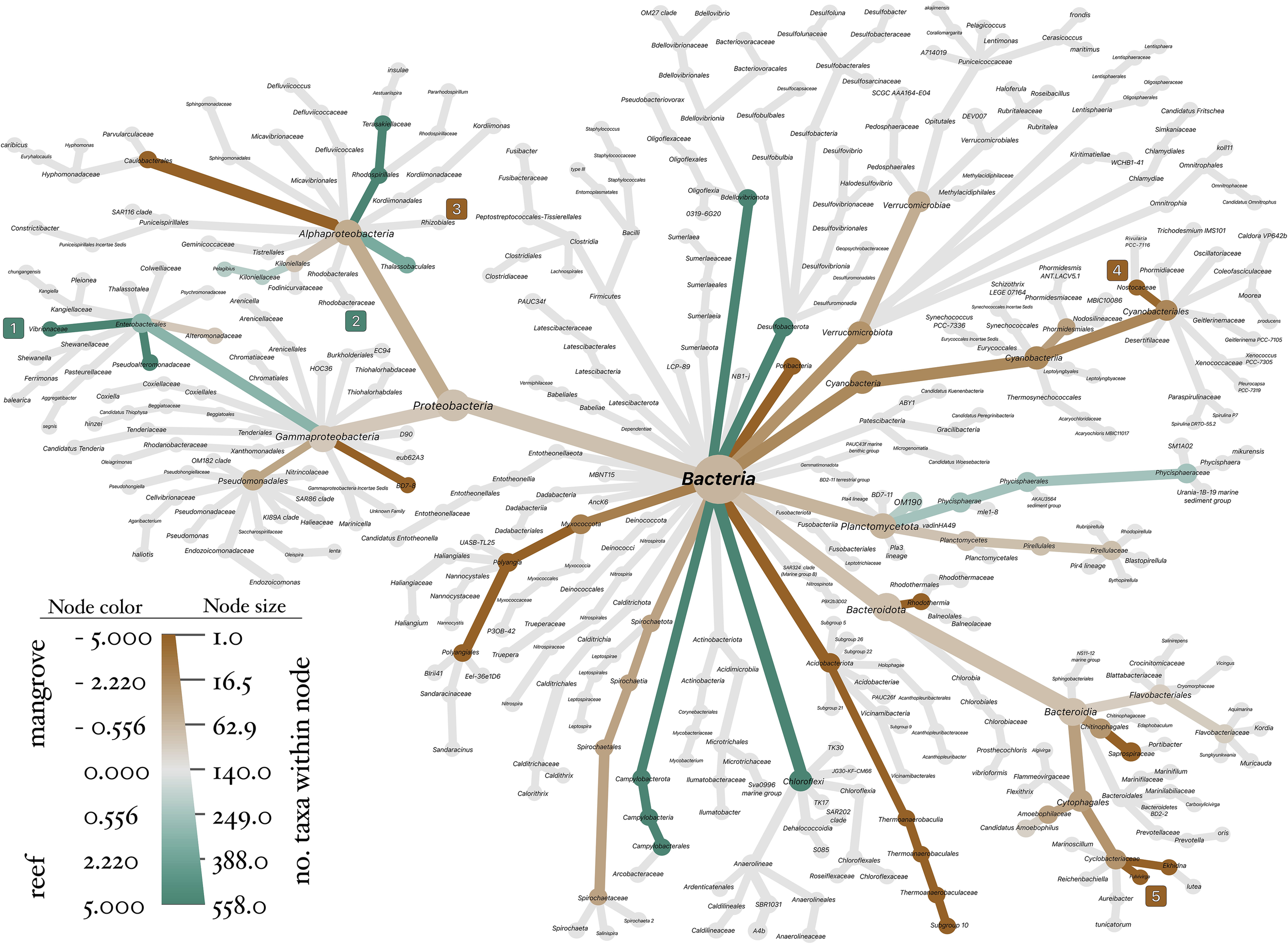

The abundance of most bacterial lineages was higher in mangrove habitats compared to reef habitats (Figure 4), including important bacterial groups such as cyanobacteria and Hyphomicrobiales. However, some bacterial lineages were more abundant in reef habitats, as is the case of the genus Vibrio. The biomarkers identified by LEfSe include 5 lineages in 5 families and 3 phyla. The biomarkers associated with each habitat are located at various positions on the tree and are not necessarily clustered together (Figure 4), which suggests that the biomarkers represent a diverse set of taxa.

Figure 4

Differences in abundance of bacterial lineages between habitats. Visualization of abundance variations in bacterial lineages between habitats, represented as an unrooted bacterial tree. The color gradient reflects the log-2 ratio of median proportions, providing a visual representation of the relative abundance differences between reef habitats in teal, and mangrove habitats in brown. The terminal nodes are marked with numbers enclosed in colored squares, indicating the five lineages identified as biomarkers by LEfSe.

Discussion

Results from this study indicate that microbiomes of Favia fragum in mangrove and reef habitats cluster distinctly (Figure 2), as confirmed by PERMANOVA. Among the 568 variants observed in this study, 215 are unique to mangroves, 179 to reefs, and 174 are shared. LEfSe identified five habitat-associated lineages as biomarkers (Figure 3), with taxonomy assignments improved via BLAST revealing these lineages as: Vibrio (Genus) > Vibrio sp., Hyphomicrobiales (Order) > Stappiaceae (Family)> Pseudovibrio (Genus)> Pseudovibrio sp., and an unknown bacterium variant. Most bacterial lineages were more abundant in mangroves, but exceptions to this pattern existed (Figure 4). Microbiomes of golfball corals living beneath mangrove canopies were significantly different from those living on reefs. In addition, the similar community structure of microbial communities within mangrove habitats and the higher relative abundance estimated from the log2 ratios of median proportions (Figure 4) of bacteria in mangrove habitats support the hypothesis that mangrove habitats significantly influenced the microbial communities of F. fragum.

A notable finding from our study was the observation that some golfball coral specimens from the STRI reef site exhibited similar microbiomes to those found in the adjacent mangrove habitats observed through overlapping communities with small dissimilarities. This overlap was not observed at Coral Cay, where reef and mangrove sites were dissimilar. We propose that this observation can be attributed to the contrasting spatial distributions of habitats at our two study sites. At STRI, the reef sampling locations were located a few meters from the mangrove fringe, suggesting that the close proximity likely facilitates a greater exchange and mixing of microbes between the two habitats. This mixing could occur through various mechanisms such as tidal flushing, ocean currents, or sediment transport. In contrast, the reef samples at Coral Cay were located approximately one kilometer from the mangrove habitat. This greater distance likely acts as a significant barrier to such extensive microbial exchange, thereby maintaining the dissimilarities in microbial communities between habitats at that site.

Differences in microbiome community structure between mangrove and coral reef habitats have been previously observed (Haydon et al., 2021). In their recent study, Haydon et al. (2021) found differences in the microbiomes of Pocillopora acuta between a reef and a mangrove in Australia. However, the lack of habitat replication in their study design complicates the interpretation of their results and may confound differences due to environmental conditions between habitats with differences due to the geographic distance between their field sites. In our study, corals occurring in mangrove habitats at two sites, separated by ~10km, hosted similar microbiomes. Furthermore, mangrove habitats at both sites were associated with an enriched relative abundance of three biomarker lineages: Cyanobacteria, Rhizobiales and Bacteroidia.

Cryptic coral lineages have recently been emphasized as a potential source of genetic variation that could allow coral species to acclimatize and adapt to climate change (Grupstra et al., 2024). For example, cryptic diversity within the Acropora hyacinthus species complex, resulting in differences in symbiont associations, explains differences in resilience to bleaching (Rose et al., 2021). Furthermore, intraspecific cryptic diversity can provide a mechanism for resilience to thermal stress in corals (Aichelman et al., 2025). For example, three functionally distinct lineages that differ in morphology, phenomes, distributions, and symbiotic associations were observed in the coral Siderastrea siderea in Bocas del Toro, Panama; each of these lineages responded differently to a thermal challenge (Aichelman et al., 2025). The distinct associations between F. fragum on mangrove roots and coral reefs found in our study provide a foundation to explore cryptic diversity within the golfball coral that could explain our observations of distinct microbial communities between corals in mangroves and adjacent coral reefs.

One compelling finding of our study is the unexpectedly high relative abundance of Cyanobacteria and Hyphomicrobiales in mangrove-associated corals compared to reef-associated corals. Hyphomicrobiales and Cyanobacteria are nitrogen-fixers that can greatly influence the availability of nitrogen in the local environment of coral reef associated taxa such as sponges (Wilkinson and Fay, 1979) and scleractinian corals (Charpy et al., 2012). Coral reef habitats have been considered a paradox since Darwin (Darwin, 1842, as cited by Lesser, 2021) because they are hotspots of biodiversity in oligotrophic waters (Lesser, 2021). The highly evolved relationship between corals and endosymbiotic photosynthetic dinoflagellates has led to the evolutionary success of corals despite the low abundance of nutrients (Stanley, 2006; LaJeunesse et al., 2018). The high relative abundance of nitrogen-fixing taxa in mangrove habitats suggests that coral hosts could potentially shift metabolic functions from bacterial symbionts that thrive in nutrient-depleted, high-light environments to bacterial symbionts that can thrive in nutrient-rich, light-limited habitats.

Mangrove-associated corals challenge the conventional boundaries of coral reef ecosystems. Cyanobacteria are considered ubiquitous in reef habitats, but a high abundance of cyanobacteria is frequently reported as an indicator of declining coral reef health (Hallock, 2005). Cyanobacteria are known to produce toxins that can be harmful to corals, and their presence in coral reefs has been linked to coral disease (Richardson et al., 2005; Charpy et al., 2012). Cyanobacteria can also compete with corals for light, by forming microbial mats that can shade coral photosymbionts; such shading could be even more detrimental in the light-limited environment found under mangrove canopies. In addition, cyanobacterial mats, often associated with higher temperatures and nutrient loading, can inhibit the photochemical efficiency of coral symbionts and can act as reservoirs for coral pathogens (Cissell et al., 2022). While the detrimental effects of Cyanobacteria are well-documented, the effects of a high abundance of Hyphomicrobiales are currently unknown. The role of Hyphomicrobiales in a coral’s microbiome and their potential impact on host health remain a key area for future research. This study provides empirical evidence that a shift in microbial community structure is a potential mechanism through which corals can acclimate to nutrient-rich habitats such as mangroves.

We also found significant differences in the abundance of Vibrio and its close relatives (Family Vibrionaceae) between studied habitats, with higher abundances observed in the reef sites. Vibrionaceae are known to be important pathogens in corals, and their higher abundance in these sites could have important implications for coral health. For example, bacterial species of the genus Vibrio have been identified as causative agents for diseases and syndromes in corals such as white syndrome (Vibrio harveyi, Luna et al., 2010), white-band disease (Vibrio charchariae, Ritchie and Smith, 1998; Gignoux-Wolfsohn and Vollmer, 2015), brown-band disease (Vibrio corallyticus, Brown et al., 2013), and coral bleaching (Vibrio shiloi, Kushmaro et al., 2001). Future studies of coral populations beneath mangrove canopies could provide valuable insights into the factors contributing to the lower prevalence of bacterial taxa that contain known coral pathogens in these habitats.

Mass bleaching events can trigger disease outbreaks that result in high mortality (Miller et al., 2009). Importantly, there is limited empirical evidence supporting coral bleaching under mangroves during mass bleaching events. Two main schools of thought explain why corals living under mangrove canopies are more resilient to bleaching events. Rogers and Herlan (2012) suggest that lower mortality after regional bleaching events is due to less disease in mangrove-associated corals, which may relate to higher quality of individuals and lower risk of bleaching. Additionally, Stewart et al. (2021) used a reciprocal transplant experiment to conclude that light intensity is the primary parameter that increases the likelihood of bleaching and lowers survival in corals; they found that coral fragments from reefs were less likely to bleach when transplanted to mangrove habitats than fragments from mangrove-associated corals transplanted to reef sites. Stewart et al. (2021) suggest that alternate morphologies (e.g., morphologies of corals in deeper waters experiencing light limitation), changes in photosymbionts, and increased levels of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) are mechanisms by which corals can specialize into low-light environments; these mechanisms could also explain their observed variation in likelihood of bleaching after transplant. Importantly, microbial symbionts are responsible for the production of cnidarian MAAs (Dunlap and Shick, 1998), including bacteria (Arai et al., 1992; Garcia-Pichel and Castenholz, 1993) and Symbiodiniaceae dinoflagellates (i.e., zooxanthellae; Corredor et al., 2000).

One possible explanation for the observed lower incidence of Vibrio at mangrove habitats is that corals under mangrove canopies are more resilient than their conspecifics at reef habitats. Observations from Rogers and Herlan (2012), and Stewart et al. (2021) agree with the proposed mechanism that novel ecological interactions and symbiont associations in mangrove habitats are responsible for increased coral resilience in mangrove-associated corals. A shift in microbiome structure could explain differences in prevalence of disease-causing agents like Vibrio because corals in mangroves can associate with bacteria not found in reef habitats; these novel associations could potentially hinder the incidence of pathogens. Furthermore, shifts in microbiomes could be the result of sustained lower light intensity by shifting the coral host dependency on photosymbiont-produced compounds to other agents found in mangrove habitats. Future work should test whether the observed lower Vibrionaceae and higher cyanobacteria abundances in mangrove-associated corals reflect these environmental and ecological factors, rather than assuming a direct causal link to coral health by conducting comparative assessments of disease prevalence at these sites, which was beyond the scope of our current study.

Experiments manipulating light and microbial communities could clarify the mechanisms driving this pattern and inform targeted conservation strategies. This inquiry would determine whether this phenomenon results from reduced light stress from mangrove canopies, or from the overall enhanced resilience of coral populations thriving beneath mangrove canopies due to novel ecological interactions. For example, if mangroves primarily serve as protective shelters from intense sunlight, managers should prioritize the preservation and expansion of mangrove coverage. This approach could be coupled with the strategic transplantation of corals from reefs into vacant mangrove niches. To address extreme heat stress during peak hot periods, the use of floating shading structures to temporarily shield coral reefs deserves strong consideration. Conversely, if the enhanced coral health under mangroves primarily results from unique ecological interactions, a focused approach should involve transplanting corals specifically within mangrove habitats while avoiding cross-habitat transplants.

Overall, our results suggest that coral reefs and mangroves are associated with distinct microbial communities. The average coral is currently experiencing lethal stressors. In August of 2023, a panel of experts from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that a heatwave plaguing the Florida Keys has led to corals being “stressed, bleached and sometimes killed” within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (Press release, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2023). The highest recorded temperature in the area was 34°C at the Sombrero Reef site (Press release, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2023), which is a considerable deviation from the summer average of 29.1°C at this site (National Data Buoy Center, 2023). Some corals have adapted to novel environments that allow them to mitigate these stressors, such as corals living beneath mangrove canopies. Studying systems in which corals thrive due to novel circumstances can provide us with insights about the mechanisms responsible for those novel interactions.

Although we did not collect site-specific environmental data at the time of sampling, previous studies have shown that coral reef sites adjacent to mangrove habitats often exhibit distinct seawater chemistry compared to open reef systems. Mangrove-associated environments are typically characterized by lower pH, reduced dissolved oxygen, elevated pCO2, and decreased aragonite saturation states, largely driven by restricted water flow, organic matter inputs, and high biological activity (Yates et al., 2014; Camp et al., 2017; Burt et al., 2020). These biogeochemical conditions can fluctuate on diel and seasonal timescales and are known to influence coral physiology and microbial community composition. While temperature and salinity could remain similar across short spatial gradients, more subtle chemical differences might help explain differences in microbial communities observed between reef and mangrove sites.

Favia fragum is characterized by a stress-tolerant life history strategy, with slow-growing colonies and large polyps that favor defense and resilience over rapid competitive growth (Darling et al., 2012). This investment in stress tolerance likely contributes to its ability to persist in the highly variable and often stressful physicochemical conditions found in mangrove habitats, such as fluctuating light, oxygen, and pH. In contrast, more opportunistic, commonly referred to as “weedy”, corals may fail to thrive in such stressful conditions. Understanding coral resilience across different life history strategies is critical, as corals with differing life history strategies are responding differently to anthropogenic climate change, with some lineages declining rapidly while others persist or even expand (Green et al., 2008; Burgess et al., 2021). Examining how contrasting life history strategies mediate microbial associations and stress responses can provide key information about the composition and function of coral reef holobionts under accelerating global climate change.

The notion that coral hosts can shift their microbiomes to match changes in the environment is supported by empirical evidence. Chan et al. (2024) demonstrated that reciprocally transplanted Stylophora pistillata were flexible in microbiome assembly and gradually shifted their microbiomes to be more similar to local conspecifics. Although S. pistillata colonies were translocated over a distance of 475km, and shifted their microbiomes to match local conspecifics, some colonies retained their original bacterial symbiont lineages at high abundances, relative to their local conspecifics. Those lineages at higher abundance in translocated individuals were in similar relative abundance to their conspecifics that remained at their site of origin (Chan et al., 2024). The findings in the S. pistillata study suggest that hosts can have a strong control over their microbiomes and that environmental changes can overwhelm those mechanisms. Similar reciprocal transplants will be necessary to understand how F. fragum responds to environmental change and to differentiate between host-controlled core microbiome and habitat-specific microbes. These reciprocal transplants would allow us to identify the bacterial taxa consistently associated with F. fragum regardless of its location and which are merely transient members of the community, or can be exchanged for other microbes and therefore describing potential mechanisms for adaptive responses of this species.

Our study provides evidence that bacterial lineages associated with nutrient cycling occur in higher abundance in microbiomes of mangrove-associated F. fragum. These observations highlight the potential for shifts in microbial communities to allow corals to live in nutrient-rich conditions beneath mangroves, and suggest that the low abundance of bacterial lineages that include known coral pathogens could be a result of the better performance and higher resilience of mangrove-associated corals. Our data underscore the need for continued research into the interactions between individual coral hosts, microbes, and environmental conditions distinct to mangrove habitats, particularly through manipulative experiments.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, PRJNA1023296, https://datadryad.org/stash, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.gxd2547zf.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because invertebrate animals were used for the project. Samples for this project were collected under Scientific Permit for collection, marking, and observation No. SE/A-39-18, and exported under Scientific Permit for export No. SEX/A-57-18 from the Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Panama. International transportation of Coral Samples was recorded and permitted under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) permit No. 02118.

Author contributions

JM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Resources, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Visualization. RT: Supervision, Visualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Software, Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Field expeditions, sample collection, and export were supported by a Short Term Fellowship from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute awarded to JM. Molecular benchwork materials were funded by award EF-2025121 from the National Science Foundation to RT. Sequencing was funded by the Lawrence B. Slobodkin Fund for Ecology Research from the Department of Ecology and Evolution at Stony Brook University awarded to JM.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute for awarding JM the Ernst Mayr Fellowship in 2018, which enabled the execution and completion of this study. We would like to thank Dr. Liliana Davalos, Dr. Natasha Vitek, and Dr. Rachel Collin for their valuable feedback and suggestions that greatly improved the manuscript. Our heartfelt appreciation also goes to Dr. Joseph B. Kelly for his assistance with library preparation, and to Dr. Heather Stewart, J. Wright, and D. Vega for assistance in collecting some samples. Finally, we would like to recognize P. Gondola, A. Castillo, D. Gonzalez, C. Pena, M. Alvarez, U. Gonzalez, and N. Powell for their unwavering support in organizing the logistics of fieldwork at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Bocas del Toro Research Station.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aichelman H. E. Benson B. E. Gomez-Campo K. Martinez-Rugerio M. I. Fifer J. E. Tsang L. et al . (2025). Cryptic coral diversity is associated with symbioses, physiology, and response to thermal challenge. Sci. Adv.11, eadr5237. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adr5237

2

Apprill A. McNally S. Parsons R. Weber L. (2015). Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microbial Ecology.75, 129–137. doi: 10.3354/ame01753

3

Arai T. Nishijima M. Adachi K. Sano H. (1992). Isolation and structure of a UV absorbing substance from the marine bacterium Micrococcus sp. AK-334 (Tokyo, Japan: Marine Biotechnology Institute), 88–94.

4

Baird A. H. Guest J. R. Willis B. L. (2009). Systematic and biogeographical patterns in the reproductive biology of scleractinian corals. Annu. Rev. Ecology Evolution Systematics.40, 551–571. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120220

5

Berendsen R. L. Pieterse C. M. Bakker P. A. (2012). The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant science.17, 478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001

6

Burt J. A. Camp E. F. Enochs I. C. Johansen J. L. Morgan K. M. Riegl B. et al . (2020). Insights from extreme coral reefs in a changing world. Coral Reefs39 (3), 495–507.

7

Bolger A. M. Lohse M. Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics.30, 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

8

Bosch T. C. McFall-Ngai M. J. (2011). Metaorganisms as the new frontier. Zoology.> 114, 185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2011.04.001

9

Brown T. Bourne D. Rodriguez-Lanetty M. (2013). Transcriptional activation of c3 and hsp70 as part of the immune response of Acropora millepora to bacterial challenges. PloS One8, e67246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067246

10

Burgess S. C. Johnston E. C. Wyatt A. S. Leichter J. J. Edmunds P. J. (2021). Response diversity in corals: hidden differences in bleaching mortality among cryptic Pocillopora species. Ecology.102, e03324. doi: 10.1002/ecy.3324

11

Callahan B. J. McMurdie P. J. Rosen M. J. Han A. W. Johnson A. J. A. Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869

12

Camp E. F. Nitschke M. R. Rodolfo-Metalpa R. Houlbreque F. Gardner S. G. Smith D. J. et al . (2017). Reef-building corals thrive within hot-acidified and deoxygenated waters. Scientific Reports7 (1), 2434.

13

Cao Y. Dong Q. Wang D. Zhang P. Liu Y. Niu C. (2022). microbiomeMarker: an R/Bioconductor package for microbiome marker identification and visualization. Bioinformatics.38, 4027–4029. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac438

14

Carlon D. B. Budd A. F. (2002). Incipient speciation across a depth gradient in a scleractinian coral? Evolution.56, 2227–2242. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00147.x

15

Carlon D. B. Lippe C. (2008). Fifteen new microsatellite markers for the reef coral Favia fragum and a new Symbiodinium microsatellite. Mol. Ecol. Resources.8, 870–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02095.x

16

Carlon D. B. Lippe C. (2011). Estimation of mating systems in Short and Tall ecomorphs of the coral Favia fragum. Mol. Ecology.20, 812–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04983.x

17

Charpy L. Casareto B. E. Langlade M. J. Suzuki Y. (2012). Cyanobacteria in coral reef ecosystems: a review. J. Mar. Biol. doi: 10.1155/2012/259571

18

Cissell E. C. Eckrich C. E. McCoy S. J. (2022). Cyanobacterial mats as benthic reservoirs and vectors for coral black band disease pathogens. Ecol. Applications.32, e2692. doi: 10.1002/eap.2692

19

Chan Y. F. Chen Y. H. Yu S. P. Chen H. J. Nozawa Y. Tang S. L. (2024). Reciprocal transplant experiment reveals multiple factors influencing changes in coral microbial communities across climate zones. Science of the Total Environment907, 167929.

20

Clemente J. C. Ursell L. K. Parfrey L. W. Knight R. (2012). The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell.148, 1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035

21

Collin R. (2005). Ecological monitoring and biodiversity surveys at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s Bocas del Toro research station. Caribbean J. Sci.41, 367–373.

22

Corredor J. E. Bruckner A. W. Muszynski F. Z. Armstrong R. A. García R. Morell J. M. (2000). UV-absorbing compounds in three species of Caribbean zooxanthellate corals: depth distribution and spectral response. Bull. Mar. science.67, 821–830.

23

Darling E. S. Alvarez-Filip L. Oliver T. A. McClanahan T. R. Côté I. M. (2012). Evaluating life-history strategies of reef corals from species traits. Ecol. Lett.15, 1378–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01861.x

24

Darwin C. (1842). The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (London: Smith, Elder and Co), 214pp.

25

Dunlap W. C. Shick J. M. (1998). Ultraviolet Radiation-absorbing mycosporine-like amino acids in coral reef organisms: A biochemical and environmental perspective. J. Phycology.34, 418–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.1998.340418.x

26

Easson C. G. Chaves-Fonnegra A. Thacker R. W. Lopez J. V. (2020). Host population genetics and biogeography structure the microbiome of the sponge Cliona delitrix. Ecol. Evol.10, 2007–2020. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6033

27

Eddy T. D. Lam V. W. Reygondeau G. Cisneros-Montemayor A. M. Greer K. Palomares M. L. D. et al . (2021). Global decline in capacity of coral reefs to provide ecosystem services. One Earth.4, 1278–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2021.08.016

28

Esper E. J. C. (1797). Fortsetzungen der Pflanzenthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Farben erleuchtet nebst Beschreibungen1. In der Raspeschen Buchhandlung

29

Feller I. C. McKee K. L. Whigham D. F. O'neill J. P. (2003). Nitrogen vs. phosphorus limitation across an ecotonal gradient in a mangrove forest. Biogeochemistry.62, 145–175. doi: 10.1023/A:1021166010892

30

Foster Z. S. Sharpton T. J. Grünwald N. J. (2017). Metacoder: An R package for visualization and manipulation of community taxonomic diversity data. PloS Comput. Biol.13, e1005404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005404

31

Freeman C. J. Thacker R. W. (2011). Complex interactions between marine sponges and their symbiotic microbial communities. Limnology Oceanography56, 1577–1586. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.5.1577

32

Garcia-Pichel F. Castenholz R. W. (1993). Occurrence of UV-absorbing, mycosporine-like compounds among cyanobacterial isolates and an estimate of their screening capacity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.59, 163–169. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.163-169.1993

33

Gignoux-Wolfsohn S. A. Vollmer S. V. (2015). Identification of candidate coral pathogens on white band disease-infected staghorn coral. PloS One10, e0134416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134416

34

Green D. H. Edmunds P. J. Carpenter R. C. (2008). Increasing relative abundance of Porites astreoides on Caribbean reefs mediated by an overall decline in coral cover. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series.359, 1–10. doi: 10.3354/meps07454

35

Grupstra C. G. B. Gómez-Corrales M. Fifer J. E. Aichelman H. E. Meyer-Kaiser K. S. Prada C. et al . (2024). Integrating cryptic diversity into coral evolution, symbiosis and conservation. Nat. Ecol. Evol.8, 622–636. doi: 10.1038/s41559-023-02319-y

36

Guzman H. M. Barnes P. A. Lovelock C. E. Feller I. C. (2005). A site description of the CARICOMP mangrove, seagrass and coral reef sites in Bocas del Toro, Panama. Caribbean J. Sci.41, 430–440.

37

Hallock P. (2005). Global change and modern coral reefs: new opportunities to understand shallow-water carbonate depositional processes. Sedimentary Geology175, 19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.12.027

38

Haney C. H. Samuel B. S. Bush J. Ausubel F. M. (2015). Associations with rhizosphere bacteria can confer an adaptive advantage to plants. Nat. Plants.1, 1–9. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.51

39

Haydon T. D. Seymour J. R. Raina J. B. Edmondson J. Siboni N. Matthews J. L. et al . (2021). Rapid shifts in bacterial communities and homogeneity of Symbiodiniaceae in colonies of Pocillopora acuta transplanted between reef and mangrove environments. Front. Microbiol.12, 756091. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.756091

40

Hoegh-Guldberg O. et al . (2007). Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science.318, 5857: 1737–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.1152509

41

Hoeksema B. W. Roos P. J. Cadée G. C. (2012). Trans-Atlantic rafting by the brooding reef coral Favia fragum on man-made flotsam. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series.445, 209–218. doi: 10.3354/meps09460

42

Howells E. J. Bauman A. G. Vaughan G. O. Hume B. C. Voolstra C. R. Burt J. A. (2020). Corals in the hottest reefs in the world exhibit symbiont fidelity not flexibility. Mol. ecology.29, 899–911. doi: 10.1111/mec.15372

43

Kellogg C. A. Moyer R. P. Jacobsen M. Yates K. (2020). Identifying mangrove-coral habitats in the Florida Keys. PeerJ.8, e9776. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9776

44

Kelly J. B. Carlson D. E. Low J. S. Rice T. Thacker R. W. (2021). The relationship between microbiomes and selective regimes in the sponge genus Ircinia. Front. Microbiol.12, 607289. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.607289

45

Knowlton N. (2001). The future of coral reefs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.98, 5419–5425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091092998

46

Kushmaro A. Banin E. Loya Y. Stackebrandt E. Rosenberg E. (2001). Vibrio shiloi sp. nov., the causative agent of bleaching of the coral Oculina patagonica. Int. J. systematic evolutionary Microbiol.51, 1383–1388. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-4-1383

47

Lahti L. Shetty S. (2017). Tools for microbiome analysis in R. Version 1.16.0. Available online at: http://microbiome.github.com/microbiome.

48

LaJeunesse T. C. Parkinson J. E. Gabrielson P. W. Jeong H. J. Reimer J. D. Voolstra C. R. et al . (2018). Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol.28, 2570–2580. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.008

49

Lesser M. P. (2021). Eutrophication on coral reefs: what is the evidence for phase shifts, nutrient limitation and coral bleaching. BioScience.71, 1216–1233. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biab101

50

Lord K. S. Barcala A. Aichelman H. E. Kriefall N. G. Brown C. Knasin L. et al . (2021). Distinct phenotypes associated with mangrove and lagoon habitats in two widespread Caribbean corals, Porites astreoides and Porites divaricata. Biol. Bull.240, 169–190. doi: 10.1086/714047

51

Luna G. M. Bongiorni L. Gili C. Biavasco F. Danovaro R. (2010). Vibrio harveyi as a causative agent of the White Syndrome in tropical stony corals. Environ. Microbiol. Rep.2, 120–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00114.x

52

Marino C. M. Pawlik J. R. López-Legentil S. Erwin P. M. (2017). Latitudinal variation in the microbiome of the sponge Ircinia campana correlates with host haplotype but not anti-predatory chemical defense. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series.565, 53–66. doi: 10.3354/meps12015

53

Martin M. (2011). Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J.17, 10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200

54

McLaren M. (2022). speedyseq Version 0.5.3.9018 Public. Available online at: https://github.com/mikemc/speedyseq.

55

McMurdie P. J. Holmes S. (2013). phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PloS One8, e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217

56

Miller J. Muller E. Rogers C. Waara R. Atkinson A. Whelan K. R. T. et al . (2009). Coral disease following massive bleaching in 2005 causes 60% decline in coral cover on reefs in the US Virgin Islands. Coral Reefs.28, 925–937. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0531-7

57

Mohamed A. R. Amin S. A. Voolstra C. R. Cárdenas A. (2025). “ Complexity of the Coral Microbiome Assembly,” in Coral Reef Microbiome (Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland), 105–110.

58

Mumby P. J. Edwards A. J. Arias-Gonzalez J. Lindeman K. C. Blackwell P. G. Gall A. et al . (2004). Mangroves enhance the biomass of coral reef fish communities in the Caribbean. Nature.427, 533–536. doi: 10.1038/nature02286

59

National Data Buoy Center (2023). Station Page for SMKF1. Available online at: https://www.ndbc.noaa.gov/station_page.php?station=smkf1 (Accessed September 21, 2023).

60

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2023). Extreme Ocean Temperatures Are Affecting Florida’s Coral Reef. Press Release. Available online at: https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/news/extreme-ocean-temperatures-are-affecting-floridas-coral-reef (Accessed September 21, 2023).

61

Oksanen J. Simpson G. Blanchet F. Kindt R. Legendre P. Minchin P. et al . (2025). “ vegan: Community Ecology Package,” in R package version 2.5-7. Available online at: http://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=vegan.

62

Pollock F. J. McMinds R. Smith S. Bourne D. G. Willis B. L. Medina M. et al . (2018). Coral-associated bacteria demonstrate phylosymbiosis and cophylogeny. Nat. Commun.9, 4921. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07275-x

63

Quast C. Pruesse E. Yilmaz P. Gerken J. Schweer T. Yarza P. et al . (2012). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res.41, D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219

64

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing ( R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/.

65

Richardson L. L. Miller J. K. Broderick K. L. (2005). Coral Disease Handbook: Guidelines for Assessment, Monitoring and Management (Gainesville, FL: Univ. of Florida Press), 133.

66

Ritchie K. B. (2006). Regulation of microbial populations by coral surface mucus and mucus-associated bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series.322, 1–14. doi: 10.3354/meps322001

67

Ritchie K. B. Smith G. W. (1998). Type II white-band disease. Rev. Biol. Tropical.46, 199–203.

68

Rogers C. S. (2017). A unique coral community in the mangroves of Hurricane Hole, St. John, US Virgin Islands. Diversity.9, 29. doi: 10.3390/d9030029

69

Rogers C. S. Herlan J. J. (2012). “ Life on the edge: corals in mangroves and climate change,” in Proceedings of the 12th International Coral Reef Symposium, Cairns, Australia, Cairns, Australia. 9–13.

70

Rose N. H. Bay R. A. Morikawa M. K. Thomas L. Sheets E. A. Palumbi S. R. (2021). Genomic analysis of distinct bleaching tolerances among cryptic coral species. Proc. R. Soc. B288, 20210678. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2021.0678

71

Schliep K. P. (2011). phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics.27, 592–593. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq706

72

Shetty S. Lahti L. (2023). microbiomeutilities: Utilities for Microbiome Analytics. R package version 1.00.17

73

Segata N. Izard J. Waldron L. Gevers D. Miropolsky L. Garrett W. S. et al . (2011). Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol.12, 1–18. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60

74

Speelman P. E. Parger M. Schoepf V. (2023). Divergent recovery trajectories of intertidal and subtidal coral communities highlight habitat-specific recovery dynamics following bleaching in an extreme macrotidal reef environment. PeerJ11, e15987. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15987

75

Stanley G. D. Jr (2006). Photosymbiosis and the evolution of modern coral reefs. Science.> 312, 857–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1123701

76

Stewart H. A. Kline D. I. Chapman L. J. Altieri A. H. (2021). Caribbean mangrove forests act as coral refugia by reducing light stress and increasing coral richness. Ecosphere.12, e03413. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.3413

77

Stewart H. A. Wright J. L. Carrigan M. Altieri A. H. Kline D. I. Araújo R. J. (2022). Novel coexisting mangrove-coral habitats: Extensive coral communities located deep within mangrove canopies of Panama, a global classification system and predicted distributions. PloS One17, e0269181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269181

78

Sunagawa S. Woodley C. M. Medina M. (2010). Threatened corals provide underexplored microbial habitats. PloS One5, e9554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009554

79

Thompson L. R. et al . (2017). A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature.551, 457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature24621

80

Thompson J. R. Rivera H. E. Closek C. J. Medina M. (2015). Microbes in the coral holobiont: partners through evolution, development, and ecological interactions. Front. Cell. infection Microbiol.4, 176. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00176

81

van Oppen M. J. Blackall L. L. (2019). Coral microbiome dynamics, functions and design in a changing world. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.17, 557–567. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0223-4

82

van Oppen M. J. Oliver J. K. Putnam H. M. Gates R. D. (2015). Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.112, 2307–2313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422301112

83

Wilkinson C. R. Fay P. (1979). Nitrogen fixation in coral reef sponges with symbiotic cyanobacteria. Nature.279, 527–529. doi: 10.1038/279527a0

84

Wright E. S. (2016). Using DECIPHER v2. 0 to analyze big biological sequence data in R. R J8, 352. Biotropica. 55 (2), 299–305. doi: 10.1111/btp.13200

85

Wright J. L. Stewart H. A. Candanedo I. D'Alessandro E. Estevanez M. Araújo R. J. (2023). Coexisting mangrove-coral habitat use by reef fishes in the Caribbean. Biotropica.55, 299–305. doi: 10.1111/btp.13200

86

Yates K. K. Rogers C. S. Herlan J. J. Brooks G. R. Smiley N. A. Larson R. A. (2014). Diverse coral communities in mangrove habitats suggest a novel refuge from climate change. Biogeosciences11 (16), 4321–4337.

87

Ziegler M. Grupstra C. G. Barreto M. M. Eaton M. BaOmar J. Zubier K. et al . (2019). Coral bacterial community structure responds to environmental change in a host-specific manner. Nat. Commun.10, 3092. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10969-5

Summary

Keywords

coral holobiont, coral reef, cyanobacteria, mangrove coral, microbiome

Citation

Moscoso JA and Thacker RW (2026) Distinct microbiomes of the scleractinian coral Favia fragum in mangrove and adjacent reef habitats in the Panamanian Caribbean. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1668895. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1668895

Received

18 July 2025

Revised

04 December 2025

Accepted

10 December 2025

Published

27 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Jinwei Zhang, University of Exeter, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Amanda Shore, Farmingdale State College, United States

Xiaolei Wang, Ocean University of China, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Moscoso and Thacker.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jose A. Moscoso, jmoscosonunez@ncf.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.