Abstract

Underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand are ecologically significant habitats supporting diverse coral communities and associated marine life. However, these areas are increasingly threatened by abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), which causes several damages to coral colonies and disrupts benthic ecosystems. This study investigates the occurrence, types, sources, distribution, and ecological impacts of ALDFG at 13 underwater pinnacles across six coastal provinces. Using SCUBA-based belt transects and roving diving surveys. We assessed coral cover, identified ALDFG materials, and evaluated damage indicators such as tissue necrosis, coral fragmentation, algal overgrowth, and sediment accumulation. A total of 138 ALDFG items were recorded, predominantly composed of polyethylene nets, monofilament lines, and squid jigs. Identified gear types included otter board trawl nets, handlines, gillnets, crab traps, and squid hooks. The most common damage was tissue necrosis, with massive corals such as Porites lutea showing the highest vulnerability. Statistical analysis revealed significant spatial differences in gear types and coral impacts are influenced by distance from mainland and the level of utilization. Our findings call attention to the urgent need for targeted management strategies, including gear marking, community-based retrieval programs, and integration of ALDFG monitoring into national marine conservation frameworks. This research supports sustainable fisheries and coral reef protection through evidence-based policy and stakeholder engagement.

Introduction

Marine debris, particularly plastic debris, has become a significant environmental challenge, posing global ecological and socioeconomic concerns, due to their persistent nature (Agamuthu et al., 2019; Gilman et al., 2021). It was estimated that at least 500 kilotones of ocean plastic inputs were generated annually (Kaandorp et al., 2023). Abandoned, Lost, or Discarded Fishing Gear (ALDFG) is a critical subset of marine debris that significantly impacts ocean ecosystems and marine wildlife. ALDFG primarily consists of fishing gear that is unintentionally or intentionally abandoned in aquatic environments, posing distinct threats compared to general marine debris. Approximately, 50–100% of fishing gear is made of plastic (Apete et al., 2024), contributing to the decrease in marine plastic pollution. The volume of ALDFG has been notably increasing due to rising fishing activity and the pervasive use of synthetic materials in fishing gear, which are more durable and buoyant compared to traditional materials (Yang, 2022; Gilman et al., 2016). It has been documented that ALDFG contributes significantly to the annual increase in marine debris, with estimates indicating that global fishing gear losses account for approximately 5.7%, 8.6%, and 29% of all fishing nets, traps, lines are lost each year (Richardson et al., 2019). Approximately 18 % of the traps used in the Seribu Islands are lost annually (Riyanto et al., 2025).

Abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) is a major contributor to marine biodiversity loss. Several studies indicate that ALDFG can be as entangle, ensnare, and cause mortality to marine organisms, leading to a phenomenon referred to as ghost fishing. Ghost fishing is the indiscriminate use of fishing gear, leading to abandoned and accidentally lost ones in the marine environment, can capture marine life even after being lost (Richardson et al., 2019; Gilman et al., 2021; Angiolillo and Fortibuoni, 2020). Studies have documented effects on a multitude of taxa, with over 418 reef species reported to be affected by entanglement in ALDFG in Mediterranean environments, highlighting its ecological disruption on vital marine ecosystems (Angiolillo and Fortibuoni, 2020). In Hawaiian Islands, about 23 species of marine life interacting with derelict fishing gear (Baker et al., 2024). Ghost fishing catch in Norwegian waters reaches more than 500 tons annually, leading to a decline in fish stocks and species extinction (Vodopia et al., 2025).

Habitat destruction is another critical consequence of abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG). As it sinks to the seafloor, it can create physical and ecological damage sensitive benthic habitats, particularly coral reefs and seagrass beds, through abrasion and entanglement. Drifting or static fishing gear, especially heavy items such as nets, traps, cable or rope destroy delicate structures of reefs and injure benthic organisms (Royer et al., 2023). ALDFG can cause physical injury and mortality on branching corals like Acropora sp. due to entanglement, and plastic materials can cause physical damage and tissue loss in massive coral e.g., Porites sp (Pillai et al., 2024). Such physical damages to coral reefs by smothering corals and blocking essential light, which is crucial for photosynthesis, leading to coral disease and overall health. Plastic waste found on reef can increase 4 – 89% of risk to diseases (Chiappone et al., 2002, 2005; Lamb et al., 2018). These nets and lines can also trap sediment that may result in organic enrichment of sediments, thus increased mortality rates within coral populations (Weber et al., 2012). Furthermore, ALDFG can alter local hydrodynamics, affecting water flow around reefs, which is necessary for nutrient distribution and gas exchange vital for coral health (Angiolillo and Fortibuoni, 2020). This destruction of this critical habitat not only affects the species reliant on these environments for shelter and breeding but also disrupts the overall health and functioning of marine ecosystems (Palummo et al., 2024). The deleterious effects of ALDFG extend to altering community structures within these ecosystems, leading to shifts in biodiversity that can have cascading effects (Lovell, 2023). Moreover, ALDFG may contribute to broader plastic pollution issues in marine environments. As ALDFG degrades over time, it can fragment into microplastics, which pose additional environmental threats by entering the food chain and impacting various marine organisms (Ramos et al., 2025).

Underwater pinnacles provide an environment that is highly suitable for the growth of coral communities and hold ecological significance equivalent to coral reefs, which are among the most biodiverse, complex, and fragile ecosystems in the ocean. These habitats serve as shelters, feeding grounds, spawning sites, and nursery areas for numerous marine species (Castro and Huber, 2003; Nybakken and Bertness, 2005; Hajisamae et al., 2006; Meixia et al., 2008; Turak and DeVantier, 2019; Sutthacheep et al., 2019, 2022; Galbraith et al., 2021; Rangseethampanya et al., 2021; Cresswell et al., 2023; Yeemin et al., 2023, 2024). Underwater pinnacles are valuable natural resources with immense economic potential, particularly in areas such as tourism and pharmaceutical development, and as crucial fisheries habitats that have been important from the past to the present. Moreover, they provide a wide range of ecosystem services, including biodiversity support, habitat provision, and ecological resilience (Spurgeon, 1992, 1999; Letourneur et al., 1998; Yeemin et al., 1999, 2001; UNEP, 2006; Sala et al., 2021; Galbraith et al., 2022). However, both natural and anthropogenic factors can induce stress in coral communities. For example, physical damage from wave action or sediment deposition may ultimately result in coral mortality (Brown and Howard, 1985; Fabricius, 2005; Hughes et al., 2017; Ballesteros et al., 2018; Tuttle and Donahue, 2022; Sutthacheep et al., 2024).

Underwater pinnacles and coral reefs in the Gulf of Thailand are increasingly threatened by anthropogenic impacts, especially from abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), which includes nets, mesh panels, fishing lines, hooks, and traps. As some underwater pinnacles are located outside protected areas, these areas are being at risk from various anthropogenic activities, particularly fishing and tourism. Uncontrolled fishing and tourism severely damage coral reefs outside of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) through destructive practices, pollution, and physical damage, while also degrading the reef’s ability to recover from other stressors. Destructive fishing methods like using explosives or poison, unregulated or unsustainable fishing practice such as placing traps or net on reefs, bycatch issues, and the lack of regulations in both activities, directly harm corals and alter reef ecosystems, leading to a decline in reef health (Suebpala et al., 2017; Suebpala et al., 2021). These areas exhibit a high probability of encountering abandoned or lost fishing gear, which poses substantial ecological threats. Such gear often causes entanglement, physical breakage, and significant structural damage to coral colonies (Ballesteros et al., 2018; Yang, 2022; Rades, 2024; Pillai et al., 2024). The persistent presence of these materials degrades coral reef integrity and undermines ecosystem functionality in affected regions.

Knowledge on abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) in Thailand in various dimension is limited. Few studies on catch composition of ghost fishing. Putsa et al. (2016) investigated the impacts of ghost fishing on collapsible crab traps in Chonburi Province, Thailand. As many as 520 individuals from 25 different species were entrapped in the trap underwater 374 days and more than 95% of which were bycatch. Sukhsangchan et al. (2020) studied catch composition and estimated economic impacts of ghost-fishing squid traps in Rayong province, Thailand. During the experiment, about 46 – 56% were lost during May-October. The catch composition changed overtime, in the first week of soaking, more than 95% of catch was cephalopods (mostly bigfin reef squid). In the second and third week, the majority of catch (more than 90%) was non-commercial bycatch. After three weeks of soaking, the number of other commercial bycatch increase to 25% of all catch. Two studies focus on ALDFG, i.e., Wongnutpranont et al. (2021) investigated derelict fishing gears and other marine debris on coral communities on underwater pinnacles in Chumphon Province, Thailand through the reef cleanup programs. Fishing nets, ropes, monofilament lines, and fishing traps were mostly found on coral reefs, leading to several impacts on corals such as pale tissue, tissue loss, diseases, fragmentation, and bleaching. Mehrotra et al. (2024) assessed ecological impacts of derelict and discarded fishing gear across Thailand, highlighting that the impacts on corals and other species like crabs, muricid snails, and demersal fish were impacted due to entanglement with ALDFG. This substantial gap in knowledge and baseline information makes it difficult to combat ALDFG problems on coral reefs and underwater pinnacles in Thailand.

Therefore, this study has three primary objectives: (1) to investigate the structure of coral communities and to assess the types, quantities, and physical characteristics of abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) found around underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand, where these areas are utilized for both tourism and fisheries; (2) to determine the potential sources of ALDFG by examining its physical features, including material, color, mesh design, nets, floats, in conjunction with interviews conducted with local fishers regarding the types of gear used, the time of gear loss, and fishing locations; and (3) to analyze the impacts of ALDFG on corals and other sessile benthic organisms by identifying and categorizing the observed types of damage, such as tissue loss, colony breakage, algal overgrowth, coral diseases, and sediment accumulation. Beside, practical management recommendations for addressing ALDFG to mitigate its ecological impacts on coral reef ecosystems and support the sustainable management of marine resources, are additionally provided.

Materials and methods

Study sites

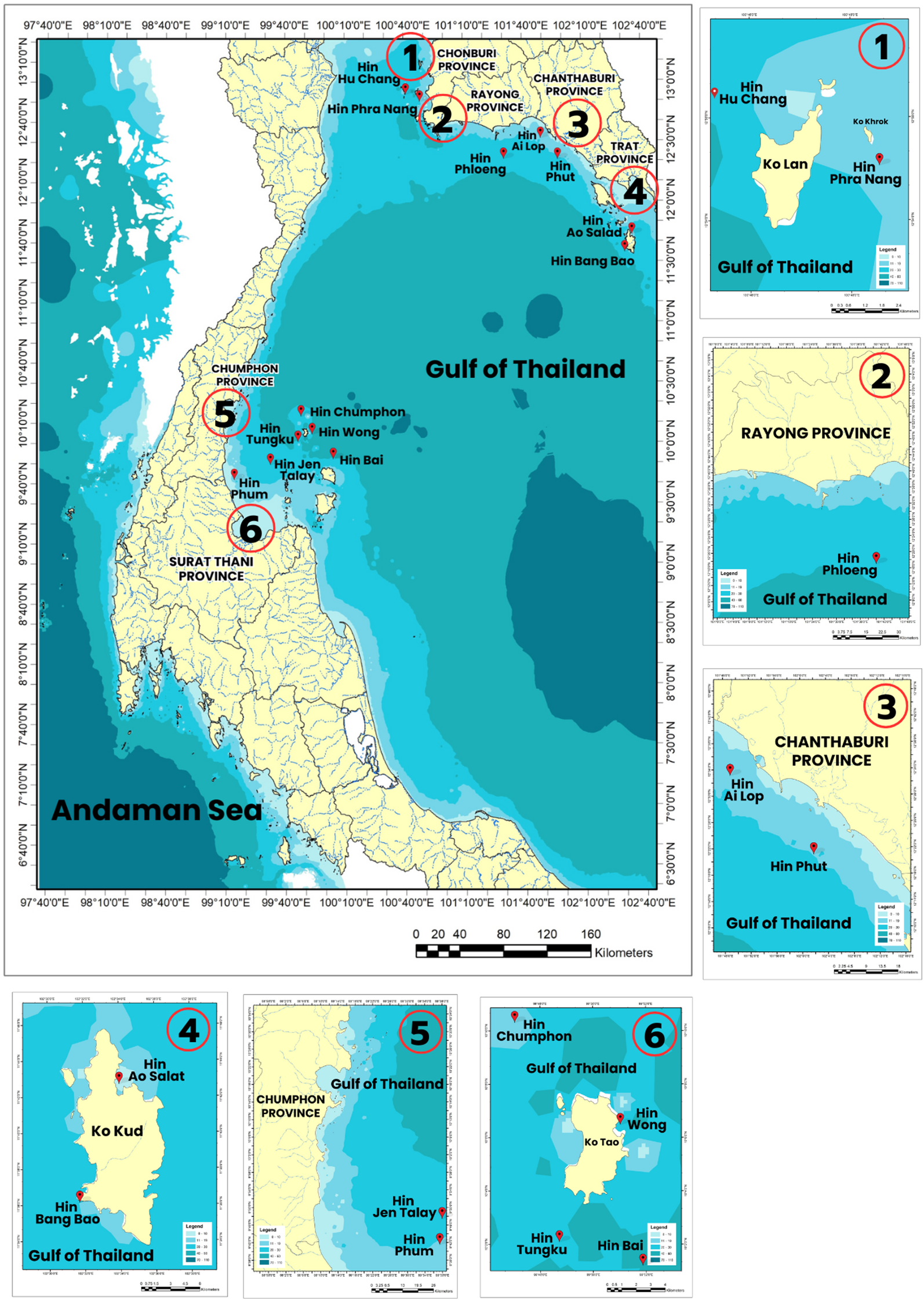

This study, surveys were conducted at13 underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand, located in the provinces of Trat, Chanthaburi, Rayong, Chon Buri, Chumphon, and Surat Thani. These sites had depth ranges from 0 to 30 meters and varied in levels of marine utilization (Figure 1; Table 1). Based on the informal interview with experienced fishers, major activities of marine tourism in the underwater pinnacles include SCUBA diving and snorkeling. Fishing gear generally found at/near the underwater pinnacles includes traps, gillnets, squid fishing hooks, and handlines and pole & lines. Trawlers and purse seine can be found near coastal waters and underwear pinnacles. Most of the sites were classified as having moderate utilization levels, including Hin Bang Bao, Hin Ao Salad, Hin Ai Lop, Hin Phut, for both tourism and fisheries, with the number of tourism and fishing vessels of 5–15 and 6–14 vessels per month. about Hin Phranang and Hin Hu Chang were classified as moderate level of tourism (8–16 vessels per month) but low level of fisheries utilization (1–6 vessels per month). Some areas, such as Hin Jen Talay and Hin Phum in Chumphon Province, were categorized as having low utilized status for tourism (1–2 vessels per month) but high status for fisheries (12–25 vessels per month). In contrast, the areas with high-utilization for tourism (18–30 vessels per month) and low-utilization for fisheries areas (1–5 vessels per month) included Hin Phloeng in Rayong Province and all four sites (Hin Chumphon, Hin Wong, Hin Bai, Hin Tungku) in Surat Thani Province.

Figure 1

Location of the study sites.

Table 1

| Province | Study site | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | Depth (m) | Distance from mainland (km) | Utilization intensity* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism | Fisheries | ||||||

| Trat | Hin Bang Bao | 11°35’51.74” N | 102°31’46.80” E | 9-15 | 42.60 | Moderate | Moderate |

| Hin Ao Salad | 11°42’52.57” N | 102°33’58.93” E | 3-7 | 32.40 | Moderate | Moderate | |

| Chanthaburi | Hin Ai Lop | 12°33’30.03” N | 101°47’47.78” E | 7-14 | 12.40 | Moderate | Moderate |

| Hin Phut | 12°20’46.93” N | 102° 2’0.36” E | 8-15 | 11.70 | Moderate | Moderate | |

| Rayong | Hin Phloeng | 12°25’51.36” N | 101°39’51.30” E | 5-20 | 31.60 | High | Low |

| Chon Buri | Hin Phranang | 12°55’9.41” N | 100°48’35.57” E | 6-14 | 5.20 | Moderate | Low |

| Hin Hu Chang | 12°54’41.35” N | 100°40’39.97” E | 4-9 | 19.70 | Moderate | Low | |

| Chumphon | Hin Jen Talay | 9°48’09.4” N | 99°18’22.4” E | 10-15 | 18.60 | Low | High |

| Hin Phum | 9°44’19.9” N | 99°18’15.2” E | 8-15 | 17.70 | Low | High | |

| Surat Thani | Hin Chumphon | 10° 17’21.94” N | 99°77’85.81” E | 12-30 | 109.30 | High | Low |

| Hin Wong | 10° 6’31.78” N | 99°50’58.94” E | 8-27 | 89.40 | High | Low | |

| Hin Bai | 9°56’41.49” N | 99°59’24.57” E | 9-27 | 75.80 | High | Low | |

| Hin Tungku | 10° 2’37.10” N | 99°48’59.23” E | 0-28 | 81.70 | High | Low | |

Study sites, geographic coordinates, depth ranges, and marine utilization levels at 13 underwater pinnacle sites in the Gulf of Thailand.

*Estimation was made using information from informal interview with experienced fishers. Low, moderate, and high level of intensity refers to the number of vessels of 1 – 5, 6 – 15, more than 15 vessels per month, respectively.

Fieldwork

Fieldwork was conducted from November 19, 2024, to April 10, 2025, at 13 sites across the provinces of Trat, Chanthaburi, Rayong, Chonburi, Chumphon, and Surat Thani, Thailand. These areas are utilized for both tourism and fisheries (Table 1). Coral communities were surveyed using SCUBA diving along three belt transects, each measuring 50 × 1 m2 (English et al., 1997). The types of substrates recorded included live coral, dead coral, coral rubble, sand, and other benthic components.

To investigate abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) around underwater pinnacles, the roving diving technique was employed. This method is widely recognized for its effectiveness in maximizing the detection of derelict fishing gear. Each dive lasted approximately one hour, with a maximum operating depth of 30 meters (Munro, 2005; Ballesteros et al., 2018). When ALDFG was encountered, the following procedures were implemented: a) record the environmental conditions at the site where the gear was found by photographing the surrounding habitat, noting seabed characteristics, and documenting the types of marine organisms present, such as corals, sponges, and sea anemones; b) carefully collect the fishing gear when feasible. If the gear can be safely removed without causing further damage, retrieve it and record its structural characteristics, ensuring minimal disturbance to the surrounding ecosystem; c) inspect the physical characteristics of the fishing gear, including the material, mesh size, color, netting pattern, floats, ropes, or any identification tags (if present), to aid in source attribution and traceability (Guzman, 2021; Einarsson et al., 2023); d) identify coral species affected by the gear using scientific names, following classification guidelines provided in Veron (2000); e) assess the type of damage observed on each coral colony. Common categories of damage include TN = Tissue Necrosis, CF = Colony Fragmentation, CD = Coral Disease, AO = Algal Overgrowth, SA = Sediment Accumulation, and ND = No Damage) The characteristics of ALDFG (Abandoned, Lost, or Discarded Fishing Gear) observed during field surveys were examined in conjunction with in-depth interviews with local fishers.

Five key informants from each province were informally interviewed, all of whom had extensive experience in fishing activities around underwater pinnacles using a variety of gear types, to help identify collected ALDFG using ALDFG collected from the fields or photographs as well as other information of fishing gear used in the area, including common locations where gear loss or damage frequently occurs, management recommendations (Richardson et al., 2022).

Data analyses

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to examine the number and characteristics of ALDFG across the different study sites. Spearman’s rank correlation was conducted to assess the relationship between the distance from the mainland and the number of ALDFG. A one-way ANOVA with Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc tests was used to perform pairwise comparisons and identify whether the average number of ALDFG differed among utilization levels, illustrating the relationship between ALDFG occurrence and the intensity of tourism and fishing activities. A principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis, based on Euclidean distance, were employed to explore similarities in ALDFG composition patterns among study sites. Data were normalized prior to analysis. A Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was used to test for differences in ALDFG composition patterns among provinces and between nearshore and offshore locations. PCA ordination plots were generated to visualize the distribution of impacted colonies/taxa in relation to different damage types: tissue necrosis (TN), coral fragmentation (CF), coral disease (CD), algal overgrowth (AO), sediment accumulation (SA), and total damage (TD). Univariate analyses were conducted in R version 4.5.1, and multivariate analyses were performed using PRIMER version 7.0.24 (Clarke & Gorley, 2001).

Results

Occurrence of ALDFG on the underwater pinnacles

Based on field surveys and informal interviews with local fishers at 13 underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand, a wide variety of abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) was observed in both quantity and physical characteristics (Table 2; Figure 2). The number of ALDFG among study sites varied from 0–32 items with a total number of 138 items. The highest number of ALDFG items was recorded at Hin Phum (32 items) and Hin Jen Talay (25 items) in Chumphon Province. In contrast, the underwater pinnacles in Surat Thani Province showed the low number of ALDFG; none was recorded at Hin Wong and Hin Bai. Hin Chumphon and Hin Tungku had only a few ALDFG.

Table 2

| Province | Study site | No. of ALDFG (items) | Main materials | Stretched mesh size (cm.) | Observed parts | Possible gear type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trat | Hin Bang Bao | 10 | PE, Nylon multifilament, ABS | 2.5 – 10.0 | Net, Line, Squid jig | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line |

| Hin Ao Salad | 9 | PE, Nylon multifilament | 2.5 – 8.0 | Net, Line | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line | |

| Chanthaburi | Hin Ai Lop | 14 | PE, Nylon mono/multifilament, ABS | 2.5 – 10.0 | Net, Line, Squid jig | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line |

| Hin Phut | 7 | PE, Nylon multifilament, ABS | 2.5 – 10.0 | Net, Line, Squid jig | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line | |

| Rayong | Hin Phloeng | 10 | PE, Nylon multifilament, ABS | 2.5 – 7.0 | Net, Line, Squid jig | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line |

| Chon Buri | Hin Phranang | 14 | PE, Nylon multifilament, ABS | 3.0 – 10.0 | Net, Line, Squid jig | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line |

| Hin Hu Chang | 12 | PE, Nylon multifilament, ABS | 2.5 – 10.0 | Net, Line, Squid jig | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line | |

| Chumphon | Hin Jen Talay | 25 | PE, Nylon mono/multifilament, ABS | 1.5 – 8.0 | Net, Line, Squid jig, Trap frame | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line, Squid trap, Squid cast net, Crab trap |

| Hin Phum | 32 | PE, Nylon mono/multifilament, ABS | 2.0 – 10.0 | Net, Line, Squid jig, Trap frame | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet, Hook and line, Squid trap, Squid cast net, Crab trap | |

| Surat Thani | Hin Chumphon | 2 | PE, Nylon multifilament | 2.5 – 10.0 | Net | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet |

| Hin Wong | 0 | – | – | – | – | |

| Hin Bai | 0 | – | – | – | – | |

| Hin Tungku | 3 | PE, Nylon multifilament | 2.5 – 10.0 | Net | Otter board trawl, Drift gillnet |

Number and characteristics of abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) found around underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand.

Data obtained from field surveys and interviews with local fishers indicate that commonly found fishing gears include otter board trawl, drift gillnet, hook and line, squid jig, and squid cast net. These gears are often discarded or lost near coral reefs or underwater pinnacles.

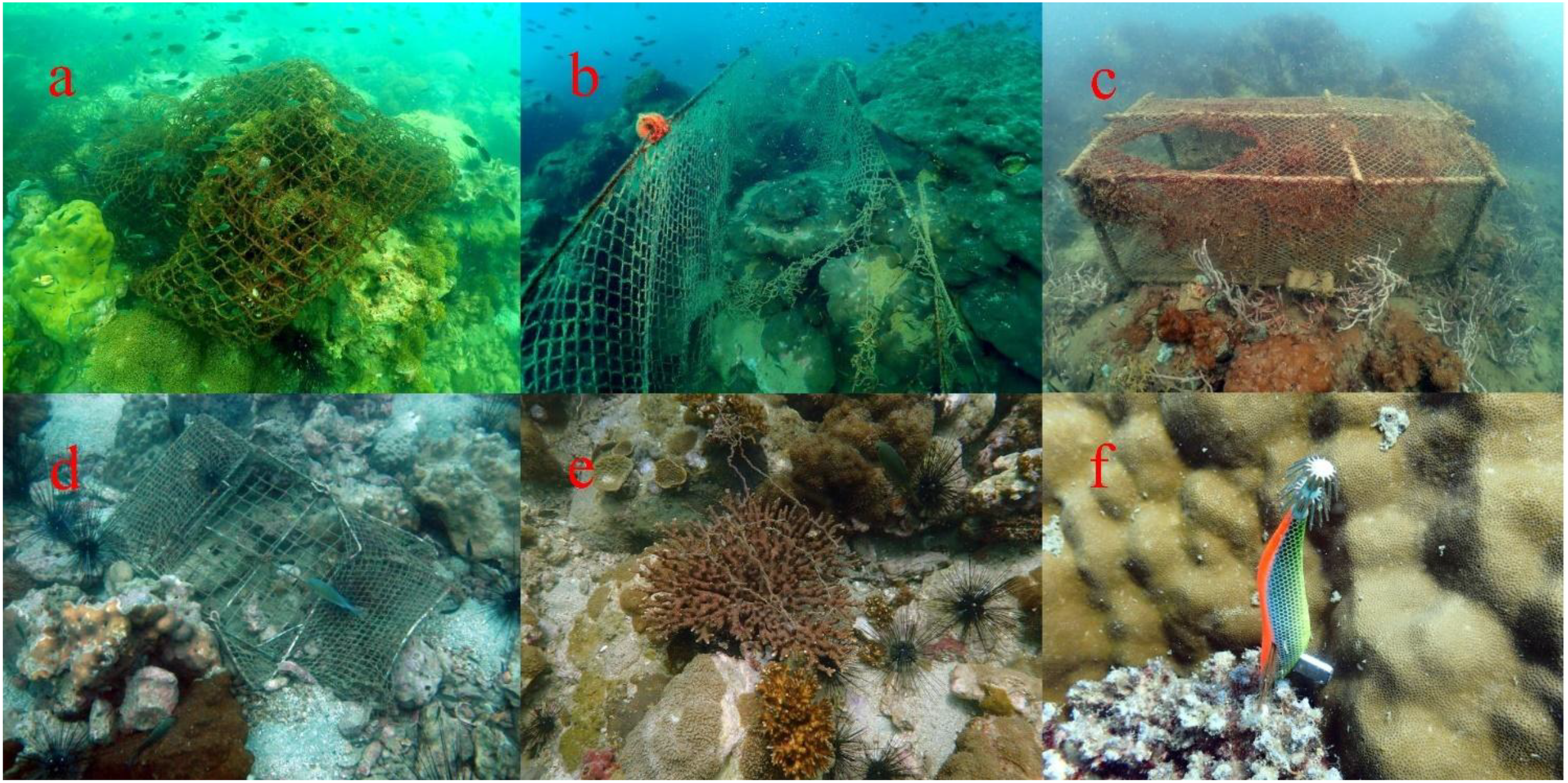

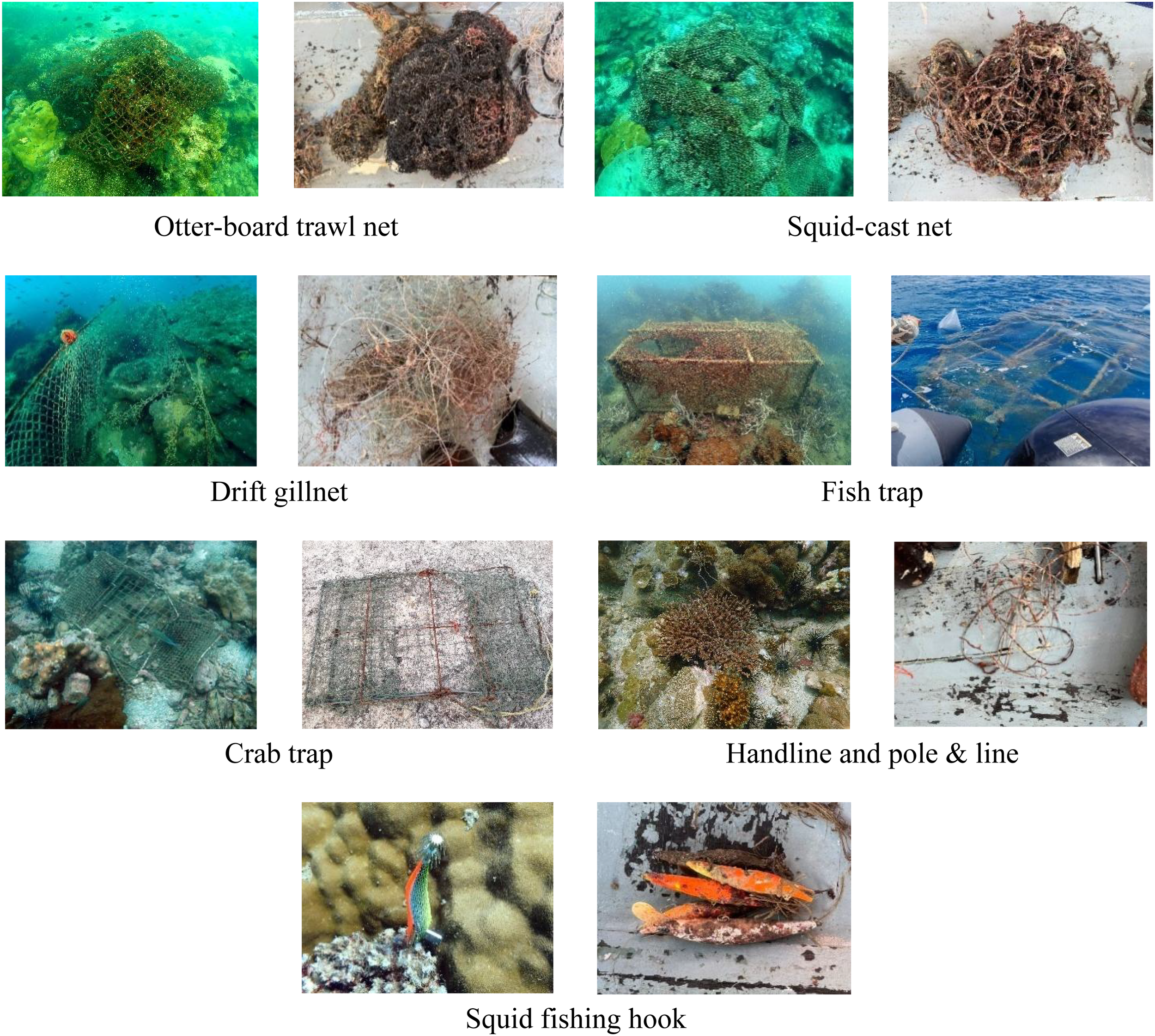

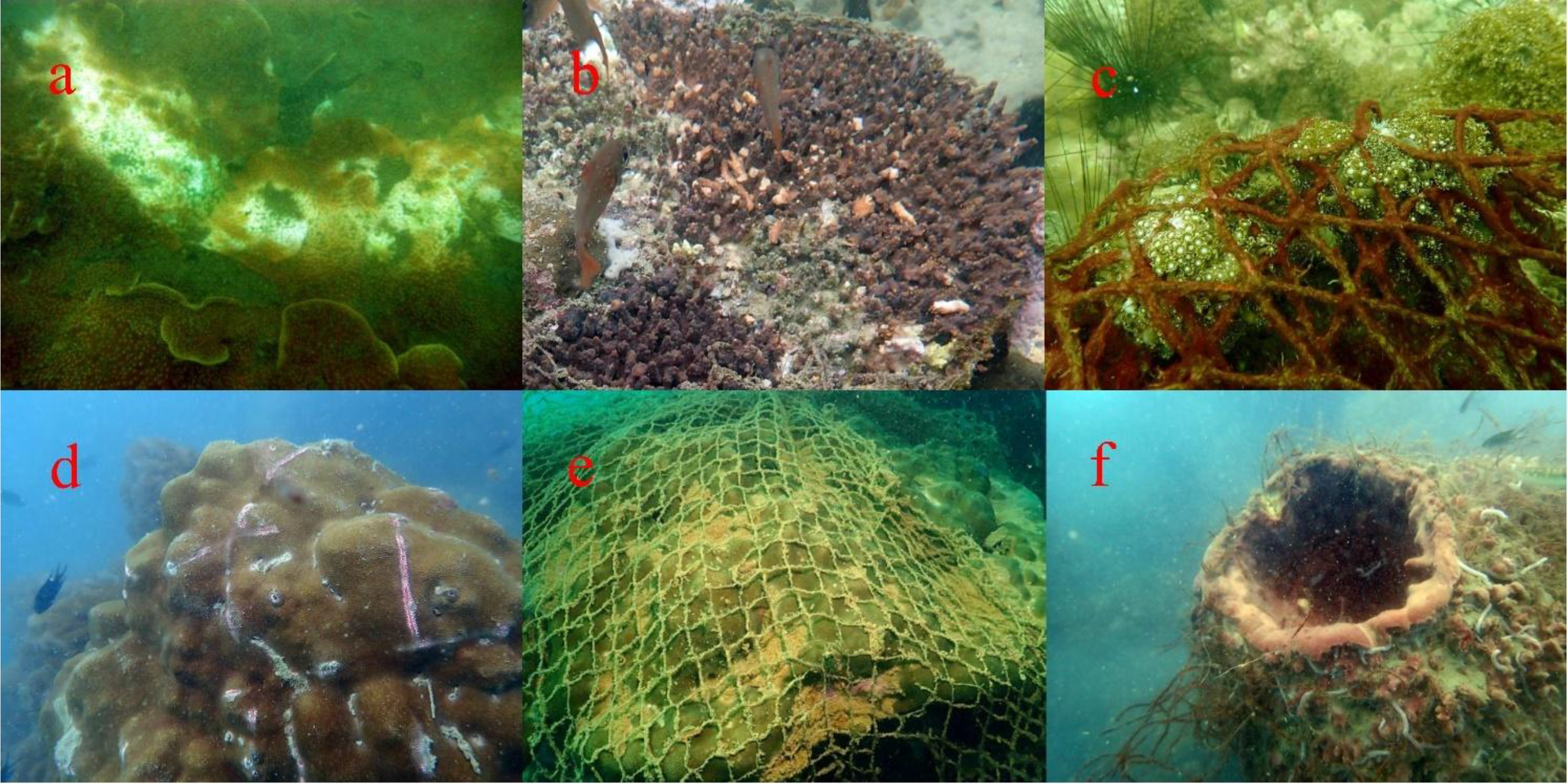

Figure 2

Examples of abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) found around underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand: (A) Otter board trawl net entangled on a coral colony of Porites lutea, (B) Drift gillnet draped over reef structures, (C) Fish trap resting on the reef floor, (D) Crab trap crushing live coral, (E) Handline and pole & line gear entangled on a coral colony of Acropora sp., (F) Squid fishing hook embedded in a coral colony of Pocillopora acuta.

The main materials found were polyethylene (PE), nylon lines (mono/multifilament), and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic, which is often used in squid jigs. The stretched mesh sizes of nets ranged from 1.5 to 10.0 cm, indicating the use of different fishing gears targeting various marine species. The most frequently encountered components were ropes and squid jigs, which reflect the widespread use of otter board trawls, drift gillnets, and hook & lines in the surveyed areas. Most ALDFG items were found near coral reefs and underwater pinnacles. Fishing gear types inferred from the recovered materials and parts included otter board trawls, drift gillnets, hook & lines, and in some locations (specifically in Chumphon Province), squid traps and squid cast nets.

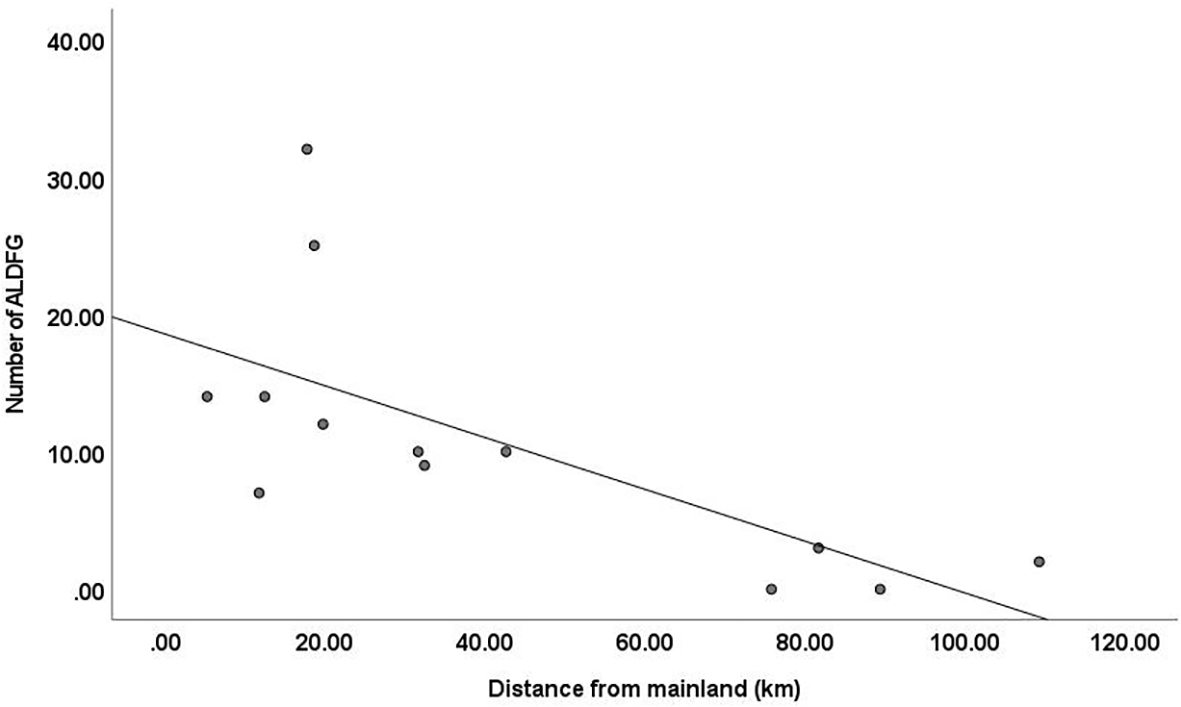

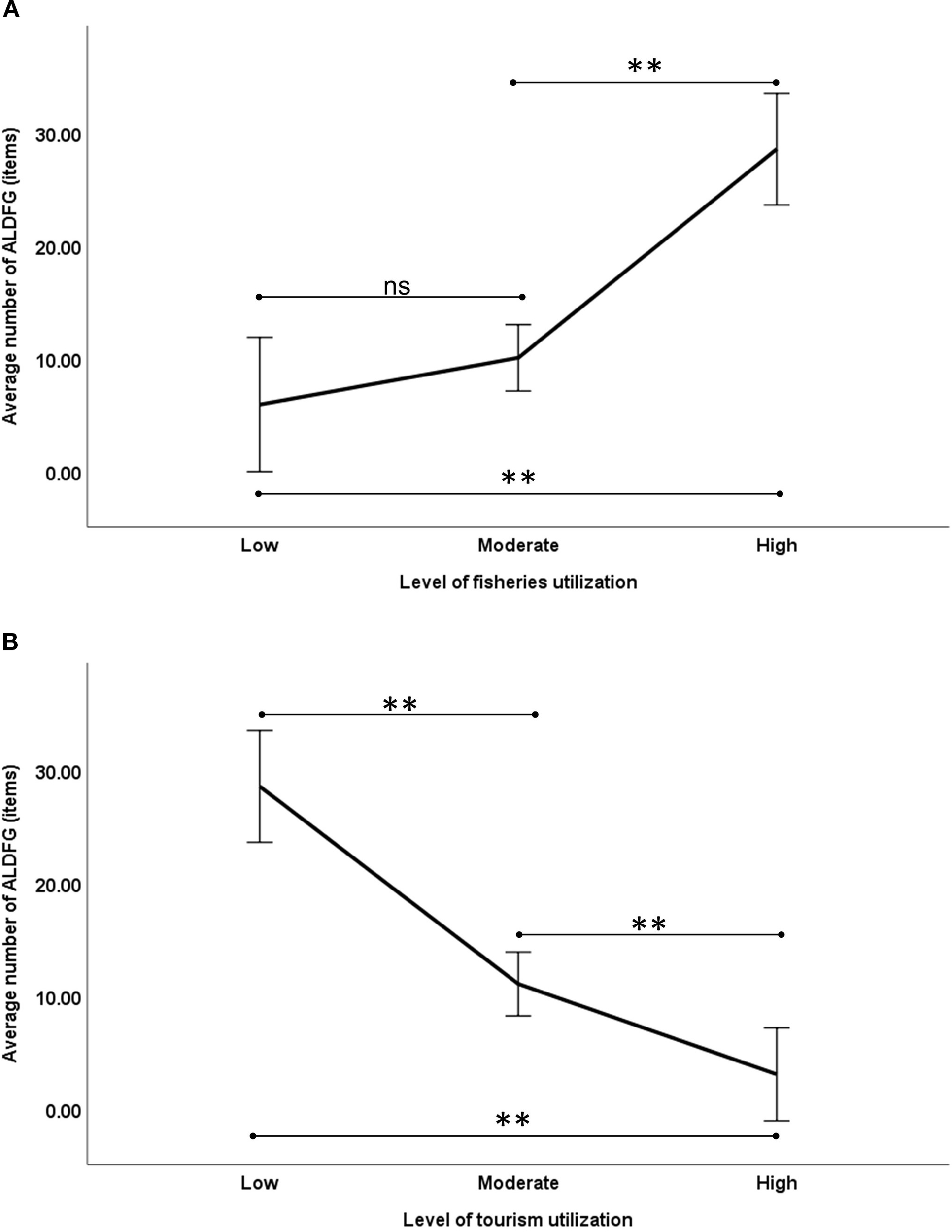

The number of ALDFG on the underwater pinnacles varied significantly by several factors i.e. distance from mainland and level of utilization intensity. Correlation analysis showed negative correlation between the distance from mainland and the number of ALDFG (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) = -0.745, n = 13, p = 0.003), revealing that the occurrence of ALDFG tended to decrease with greater distance from mainland (Figure 3). There are relationships between the average number of ALDFG across the levels of utilization, categorized as Low, Moderate, and High (Figure 4). For the utilization for fisheries, the trend shows a significant increase in ALDFG as fishing intensifies (F2,10 = 15.183, p = 0.001). The average number of ALDFG at the underwater pinnacles with high level was significantly different from those of moderate (p = 0.002) and low levels (p < 0.001). Conversely, the trend shows a significant decrease in ALDFG as tourism intensifies (F2,10 = 35.116, p < 0.001). The average number of ALDFG at the underwater pinnacles varied significantly across all levels of utilization for tourism (p < 0.01).

Figure 3

Relationship between the distance from mainland and number of ALDFG found on the underwater pinnacles (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r)= -0.745, n = 13, p = 0.003).

Figure 4

Average number of ALDFG across utilization levels for fisheries (A) and tourism (B). ns indicates not significant (p>0.05); ** indicates significant difference (p< 0.01).

ALDFG source analysis

A total of 138 items of abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) recorded from 13 underwater pinnacles across 6 provinces in the Gulf of Thailand (Figure 5) were photo-identified by experienced fishers (n = 30). Most of the them were between 24 and 62 years old. The largest proportion of interviewed fishers were 45–50 years old (36.67%), followed by those older than 50 (30.00%), 31–40 years old (23.33%), and 21–30 years old (10.00%). Fishing experience ranged from 5 to 45 years, with the majority having 10–30 years of experience (63.4%), followed by more than 30 years (23.33) and less than 10 years (13.33) of fishing experience, respectively. The results of ALDFG identification were shown below (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Results of ALDFG photo identification.

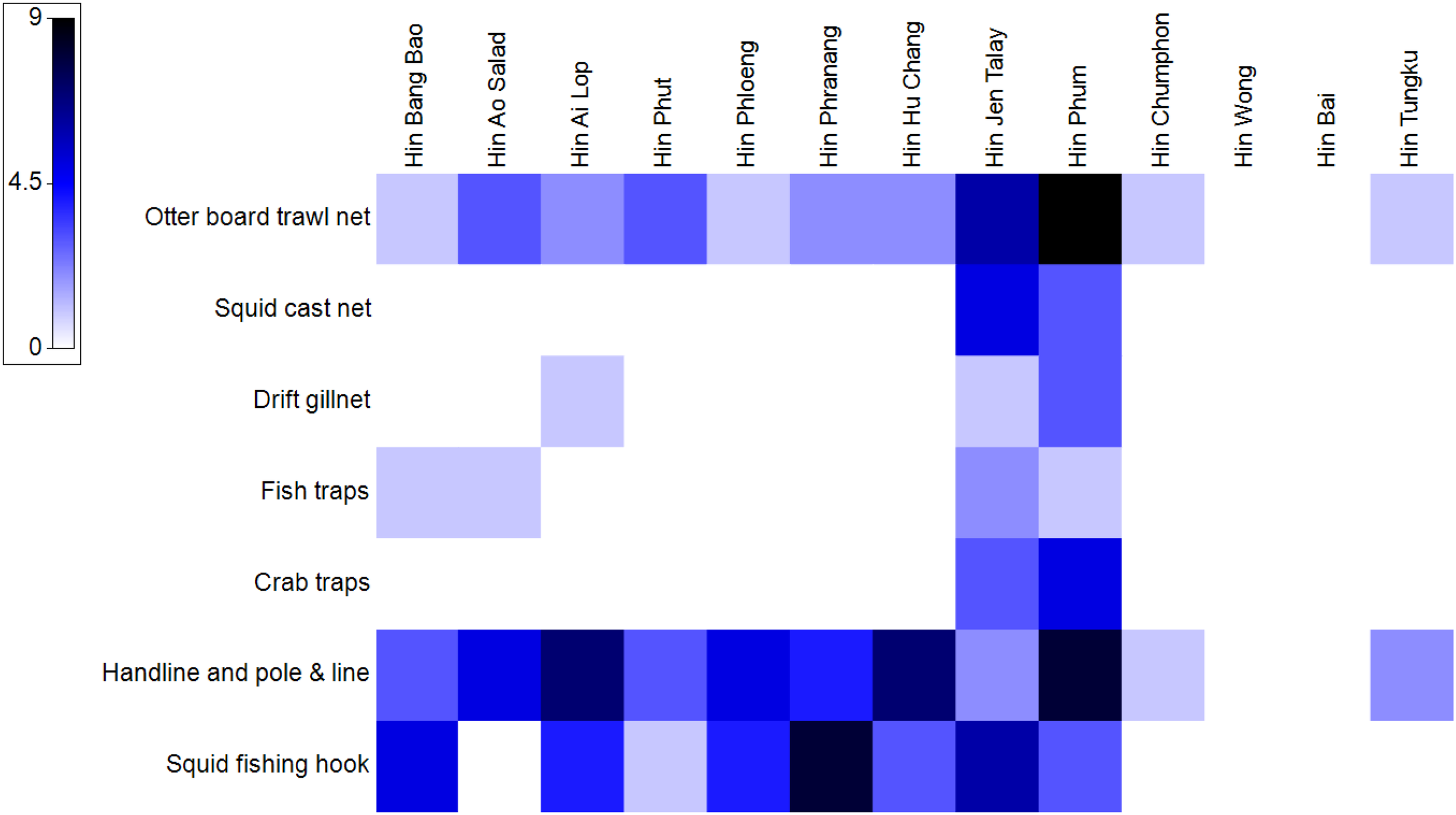

Most of ALDFG were frequently identified as handlines and pole & lines (47 items, 34.1%), followed by squid fishing hooks (34 items, 24.6%) and otter board trawl nets (31 items, 22.5%). Other gear types were found in smaller proportions, such as drift gillnets (5 items), fish traps (5 items), crab traps (8 items), and squid cast nets (8 items). The study sites with the highest number of ALDFG were Hin Phum (32 items), Hin Jen Talay (25 items), and Hin Ai Lop (14 items), all of which are areas heavily utilized for both fishing and tourism activities. These figures may reflect the frequency and intensity of human use in these locations. At the provincial level, Chumphon Province reported the highest number of discarded fishing gear, with 57 items, accounting for 41.3% of the total. Hin Phum and Hin Jen Talay contributed significantly to this figure, with frequent findings of otter board trawl nets, crab traps, and handlines. Meanwhile, Chanthaburi and Chon Buri each recorded 21 and 36 items, respectively, though the types of fishing gear varied. Chon Buri showed a greater prevalence of handlines and squid hooks, compared with Chantaburi. Handlines, pole & lines and squid fishing hooks were the major ALDFG found Trat and Rayong province (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Heatmap of abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) occurrence categorized by gear type at each underwater pinnacle in the Gulf of Thailand.

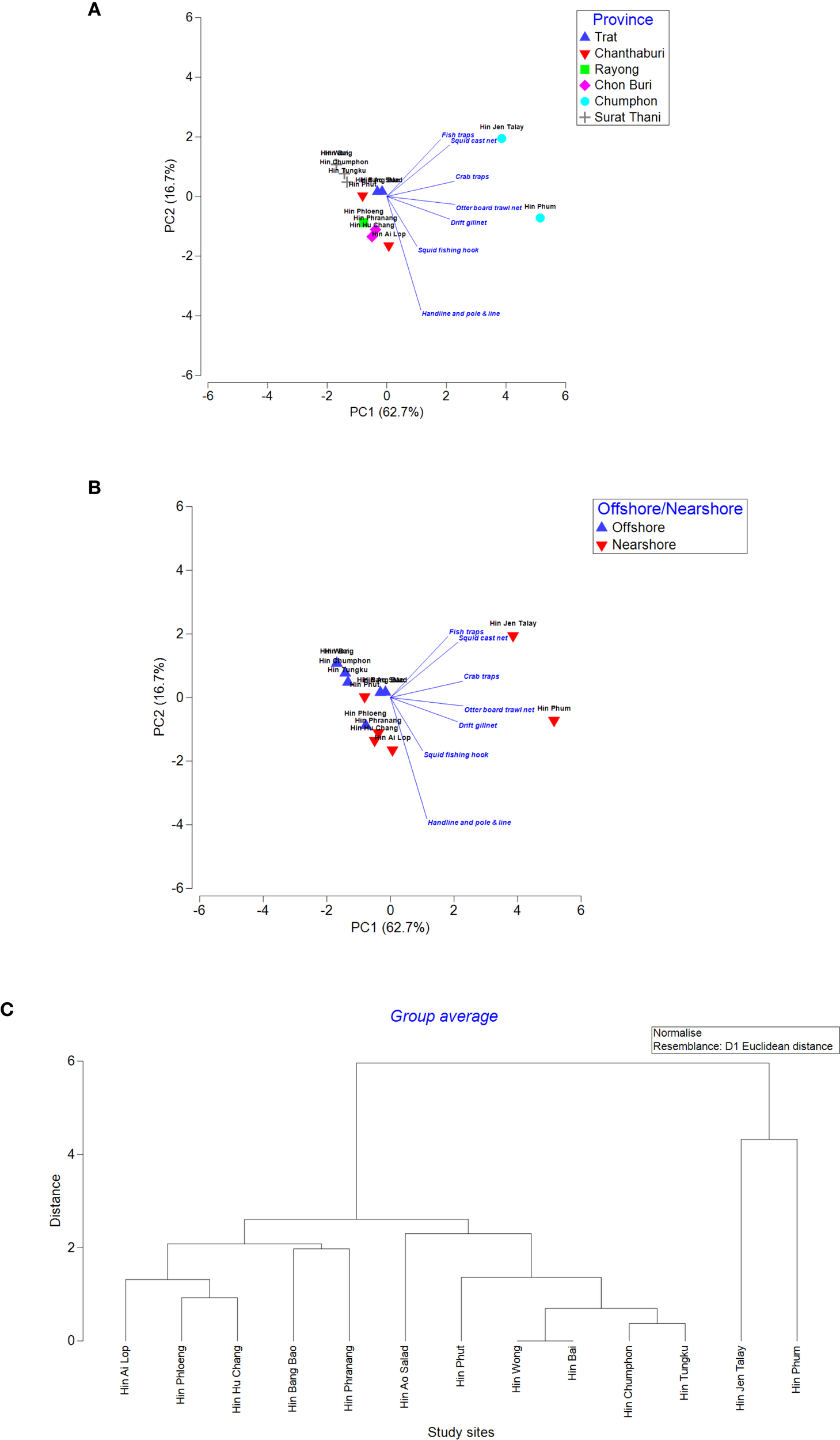

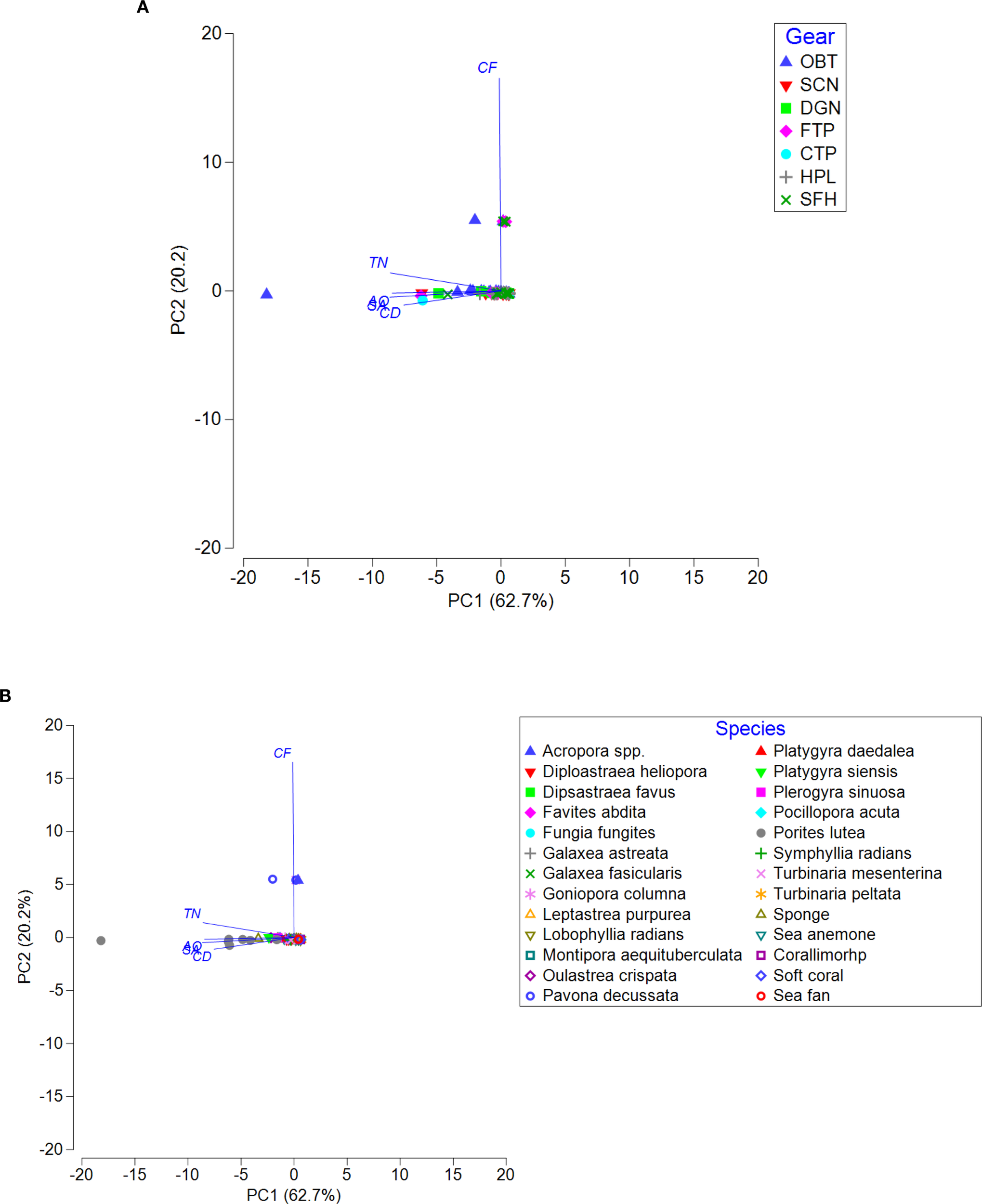

With the Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the similarity of ALDFG of each surveyed underwear pinnacle was successfully explained in the first two axes, which explained 62.7% and 16.7% of the total variation of ALDFG composition, respectively (Figures 7A, B). Cluster analysis of ALDFG shows two distinct groups of underwater pinnacles with different ALDFG composition based on Euclidean distance: Group1 consists of Hin Jen Talay and Hin Phum, showing the most diversity with high occurrence of ALDFG. The vectors on the PCA ordination graphs show that the two study sites had increasing tendency of having the higher number of fishing gear across all categories (Figures 7A–C). Group 2 consists of the other surveyed underwater pinnacles. Within this group, Hin Chumphon, Hin Tungku, Hin Wong, and Hin Bai, having least diversity with occurrence. No ALDFG was found at Hin Wong and Hin Bai. Only two ALDFG (Otter board trawl nets and handlines/pole & lines) were found with less occurrence at Hin Chumphon and Hin Tungku. The rest of the surveyed underwater pinnacles within group two were dominated by ALDFG of otter board trawl nets, handlines, pole and lines, and squid fishing hooks. Result of overall PERMANOVA showed a clear separation of ALDFG composition between Chumphon Province and the other provinces (PERMANOVA Psuedo-F = 5.051, p = 0.010). Also, significant difference of ALDFG composition between offshore and nearshore groups (cut point = 22 km or 12 nautical miles from mainland) was detected (PERMANOVA Psuedo-F = 3.451, p = 0.015), illustrating that the underwater pinnacle located nearshore tend to have higher diversity of ALDFG (Figures 7A, B).

Figure 7

Ordination plot of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the ADLFG quantity of each study site, categorized by province (A) and nearshore/offshore (B). The vectors indicate the correlations between the selected variables and axes. The length and direction of the vectors represent the strength of the relationships between types of ADLFGs and locations. Cluster dendrogram with Euclidean distance (C) of ALDFG showing the groups of the underwater pinnacles with similar ALDFG composition.

Abandoned, Lost, or Discarded Fishing Gear (ALDFG) was found in various types around underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand, differing in number, size range, total area or length, and mean dimensions (Table 3). The most frequently encountered gear was handlines and pole & lines, with 47 items totaling 162.70 meters in length and a mean length of 3.46 meters (S.D. = 2.77). This was followed by squid fishing hooks (34 items) and otter board trawl nets (31 items), with the latter having a total area of 33.96 m² and a mean area of 1.10 m² (S.D. = 2.53). The fishing gear type with the highest mean area was the drift gillnets, with an average of 3.69 m² (S.D. = 6.88), despite having only 5 items. Fish traps also had a relatively high average area of 2.73 m², with a size range of 2.00–3.22 m². In contrast, crab traps and squid fishing hooks had the lowest average sizes (0.13 m² and 0.12 m, respectively), indicating that although these gear types were frequently found, their spatial impact may be less significant compared to larger gear such as nets and traps.

Table 3

| Fishing gear type | Number of ALDFG (n) | Range (m² or m) | Total area/length (m² or m) | Mean area/length (m² or m) | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otter board trawl net (m²) | 31 | 0.08–11.70 | 33.96 | 1.10 | 2.53 |

| Squid cast net (m²) | 8 | 0.18–1.04 | 4.16 | 0.52 | 0.32 |

| Drift gillnet (m²) | 5 | 0.4–16.00 | 18.45 | 3.69 | 6.88 |

| Fish trap (m²) | 5 | 2.00–3.22 | 13.64 | 2.73 | 0.54 |

| Crab trap (m²) | 8 | 0.09–0.15 | 1.05 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| Handline and pole & line (m) | 47 | 0.60–9.50 | 162.70 | 3.46 | 2.77 |

| Squid fishing hook (m) | 34 | 0.09–0.15 | 4.11 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

Dimensions and quantities of abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) found in the Gulf of Thailand.

ALDFG impact assessment

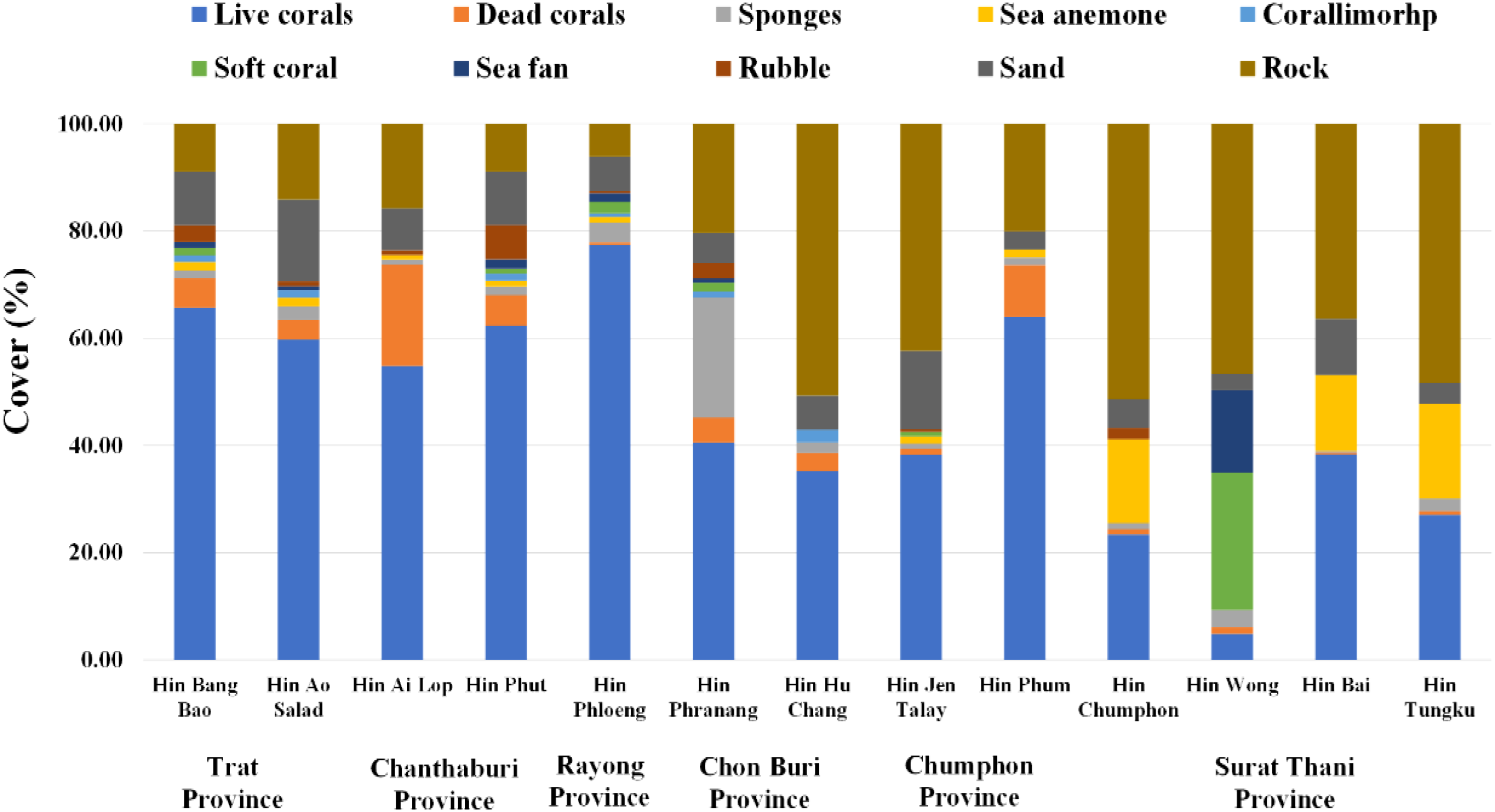

In terms of benthic habitat composition (% cover) at each underwater pinnacle, the structure of benthic cover across the underwater pinnacles varied considerably (Figure 8). Live corals were the dominant benthic component in several sites, including Hin Bang Bao, Hin Ao Salad, Hin Ai Lop, Hin Phut, Hin Phloeng, and Hin Phum, where live coral cover exceeded 60 percent of the total surveyed area. In contrast, other sites such as Hin Hu Chang, Hin Jen Talay, Hin Chumphon, Hin Bai, and Hin Tungku exhibited high proportions of coral rubble and rock, indicating more degraded or less structurally complex habitats. Furthermore, some locations showed relatively high proportions of other benthic organisms such as sponges, sea anemones, sea fans, and soft corals. A significant correlation only between the number of ALDFG and portion of dead corals was observed (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) = 0.554, p = 0.049).

Figure 8

Benthic habitat composition (% cover) at each underwater pinnacle surveyed across six provinces in the Gulf of Thailand.

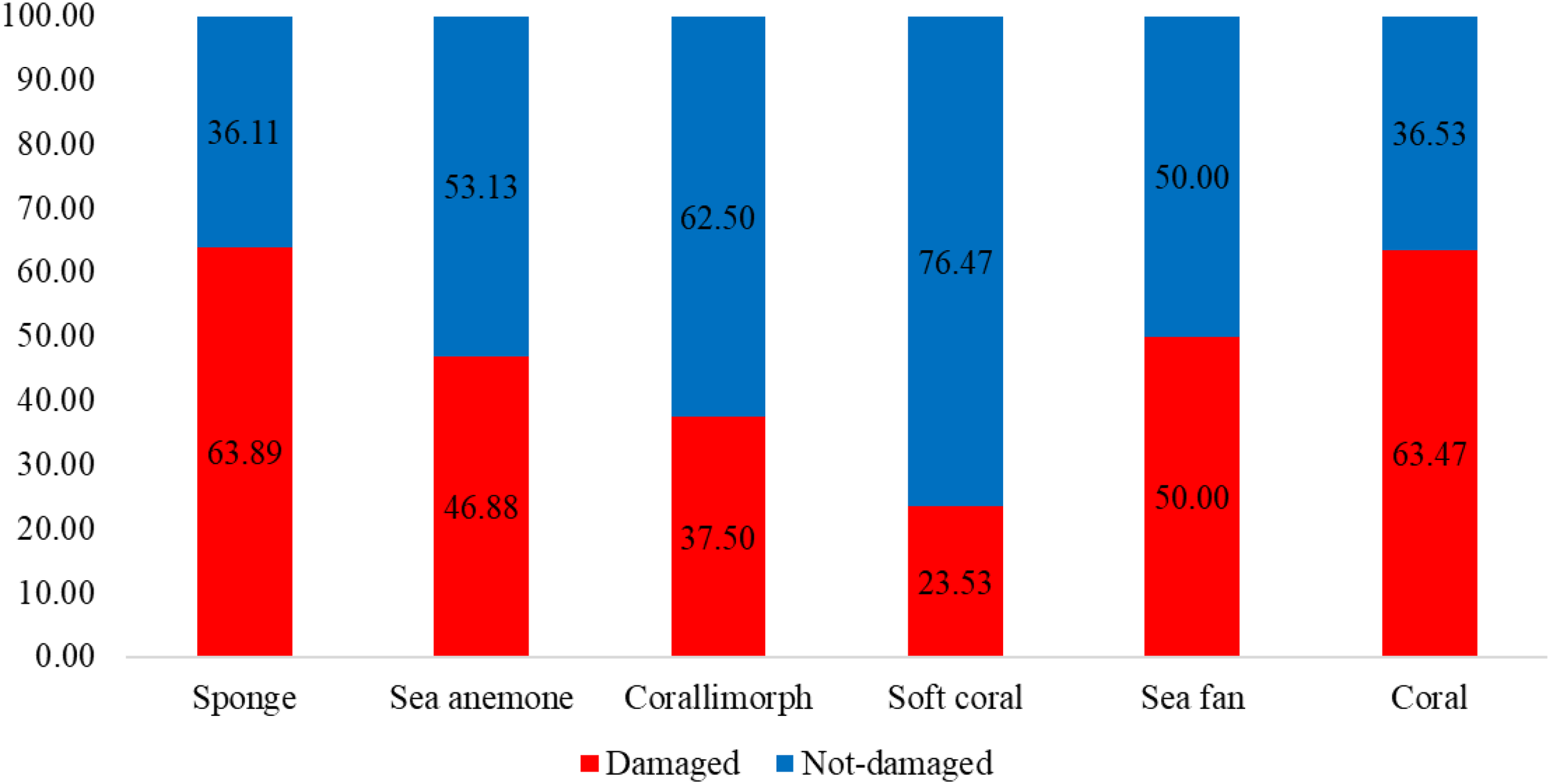

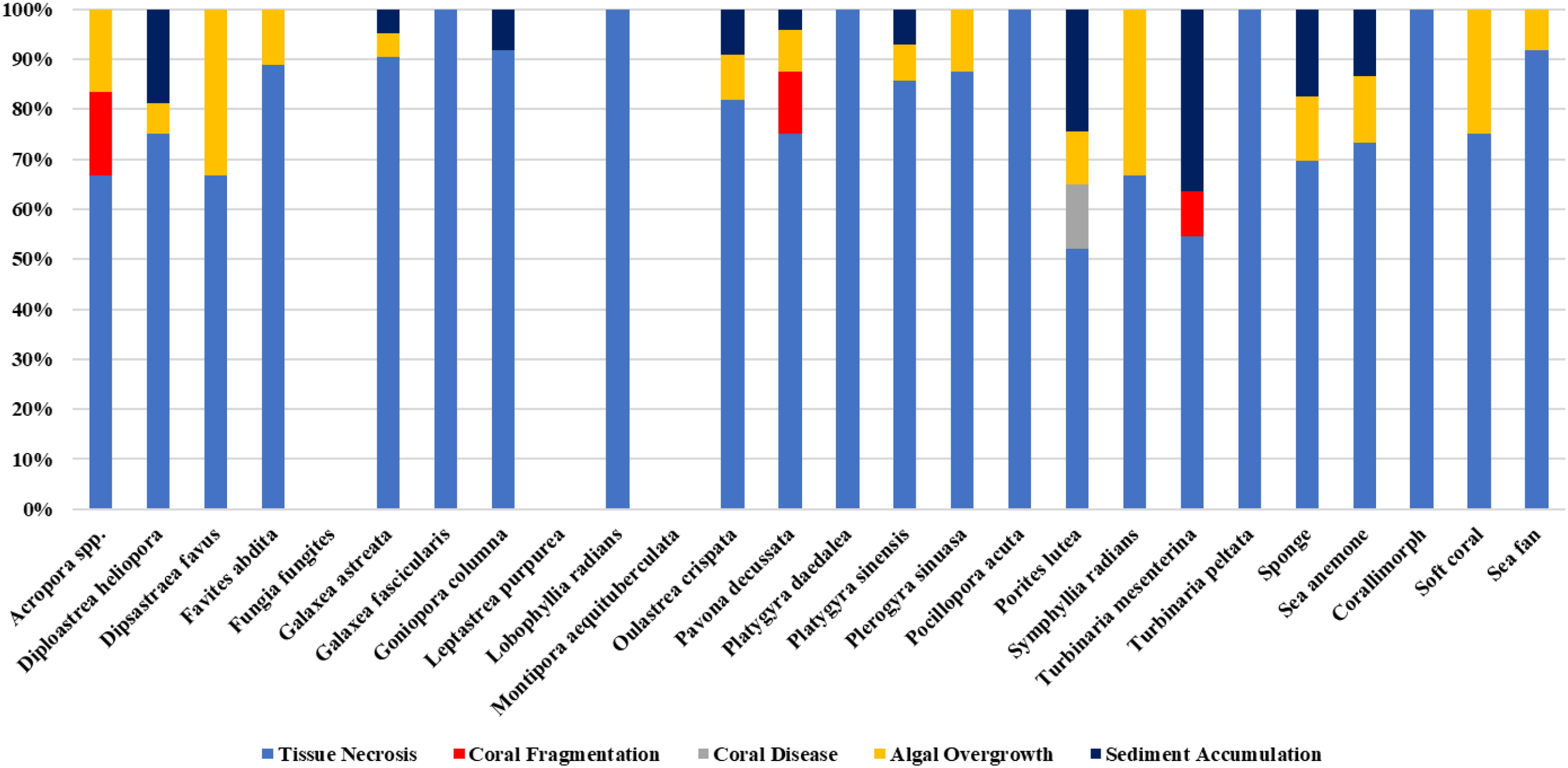

The assessment of abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) impacts on coral reef organisms revealed a range of physical damages affecting 24 coral species and 5 associated benthic invertebrate groups, including sponges, sea anemones, corallimorphs, soft corals, and sea fans. The types of fishing gear encountered included otter board trawl nets, squid cast nets, drift gillnets, fish traps, crab traps, handlines, pole & lines, and squid fishing hooks. The five major damage types assessed were tissue necrosis (TN), coral fragmentation (CF), coral disease (CD), algal overgrowth (AO), and sediment accumulation (SA). The most frequent damage observed was tissue necrosis (TN), with a total of 233 colonies, followed by sediment accumulation (SA) (48 colonies), algal overgrowth (AO) (32 colonies), coral disease (CD) (16 colonies), and coral fragmentation (CF) (6 colonies). The total damaged colonies across all species were 335, whereas 220 colonies showed no visible damage (ND). Sponges showed the highest likelihood of damages caused by ALDFG (63.89%), followed by corals (63.47%), sea fans (50.00%), sea anemones (46.88%), and corallimorphs (37.50%), while soft corals showed the lowest likelihood of damages (23.53%) (Figures 9 and 10). Among coral species, Porites lutea exhibited the highest number of damaged colonies (123 colonies), with significant occurrences of tissue necrosis (52.30%), coral disease (13.00%), algal overgrowth (10.56%), and sediment accumulation (24.39%). Other highly impacted species included Pavona decussata (24 colonies), Galaxea astreata (21 colonies), Diploastrea heliopora (16 colonies), and Platygyra sinensis (14 colonies). Most of the damaged colonies were damaged with tissue necrosis. Several taxa such as Fungia fungites, Leptastrea purpurea, and Montipora aequituberculata showed no observed damage (Table 4; Figure 11).

Figure 9

Proportion of damaged and non-damaged colonies caused by ALDFG.

Figure 10

Proportion of impacted coral colonies/taxa categorized by damage types.

Table 4

| Coral species/organisms | Fishing gear types | Number of colonies categorized by types of damages | ND | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TN | CF | CD | AO | SA | Total | |||

| Acropora spp. | OBT, FTP, HPL, SFH | 8 | 2 | – | 2 | – | 12 | 8 |

| Diploastrea heliopora | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, HPL, SFH | 12 | – | – | 1 | 3 | 16 | 13 |

| Dipsastraea favus | OBT, SCN, FTP, HPL, SFH | 2 | – | – | 1 | – | 3 | 5 |

| Favites abdita | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, CTP, HPL, SFH | 8 | – | – | 1 | – | 9 | 14 |

| Fungia fungites | DGN, FTP | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| Galaxea astreata | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, CTP, HPL, SFH | 19 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 21 | 13 |

| Galaxea fascicularis | OBT, HPL | 5 | – | – | – | – | 5 | 5 |

| Goniopora columna | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, CTP, HPL, SFH | 11 | – | – | – | 1 | 12 | 16 |

| Leptastrea purpurea | OBT, DGN | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| Lobophyllia radians | OBT, DGN, HPL | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 3 |

| Montipora aequituberculata | OBT, HPL | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| Oulastrea crispata | OBT, HPL, SFH | 9 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 11 | 5 |

| Pavona decussata | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, HPL, SFH | 18 | 3 | – | 2 | 1 | 24 | 18 |

| Platygyra daedalea | HPL | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Platygyra sinensis | OBT, HPL, SFH | 12 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 14 | 14 |

| Plerogyra sinuasa | DGN, HPL | 7 | – | – | 1 | – | 8 | 1 |

| Pocillopora acuta | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, CTP, HPL, SFH | 3 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 8 |

| Porites lutea | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, CTP, HPL, SFH | 64 | – | 16 | 13 | 30 | 123 | 25 |

| Symphyllia radians | OBT, SCN, FTP | 2 | – | – | 1 | – | 3 | 1 |

| Turbinaria mesenterina | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, HPL | 6 | 1 | – | – | 4 | 11 | 4 |

| Turbinaria peltata | OTN | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| Sponge | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, HPL, SFH | 16 | – | – | 3 | 4 | 23 | 13 |

| Sea anemone | OBT, DGN, FTP, HPL, SFH | 11 | – | – | 2 | 2 | 15 | 17 |

| Corallimorph | FTP, HPL | 3 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 5 |

| Soft coral | OBT, DGN, FTP, HPL | 3 | – | – | 1 | – | 4 | 13 |

| Sea fan | OBT, SCN, DGN, FTP, HPL, SFH | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 233 | 6 | 16 | 32 | 48 | 335 | 220 | |

Impacts of ALDFG on coral species and benthic organisms.

Damage types abbreviations: TN, Tissue Necrosis; CF, Coral Fragmentation; CD, Coral Disease; AO, Algal Overgrowth; SA, Sediment Accumulation; ND, No Damage. Fishing gear abbreviations: OBT, Otter board trawl net; SCN, Squid cast net; DGN, Drift gillnet; FTP, Fish trap; CTP, Crab trap; HPL, Handline and pole & line; SFH, Squid fishing hook.

Figure 11

Examples of coral reef damage caused by abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG): (A) Tissue necrosis on a coral colony of Porites lutea caused by contact with derelict fishing gear; (B) Coral fragmentation of Acropora sp. resulting from gear-induced breakage; (C) Algal overgrowth on a coral colony of Goniopora columna following entanglement with net debris; (D) Coral disease and tissue necrosis on Porites lutea, indicated by pink banding patterns; (E) Sediment accumulation on Porites lutea due to overlying fishing net structures; (F) Barrel sponge (Xestospongia sp.) enveloped by monofilament lines and net fragments.

Two axes of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) explained 62.7% and 20.2% of the total variation of impacted colonies with damage types, respectively (Figures 12A, B). The PCA ordination explains overall relationship between fishing gears and damage types, illustrating that otter-board trawl nets cause a wide range of damages on coral reefs. Coral fragmentation was mainly caused by otter-board trawl nets, fish traps and squid fishing hooks (Figure 11A). Considering between damage type and reef species/taxa, Porites lutea was mainly impacted by different types of damages i.e. tissue necrosis, coral disease, algal overgrowth, and sediment accumulation. Several species, particularly Acropora spp., Pavona decussata, and Turbinaria mesenterina were impacted by coral fragmentation (Figure 11B).

Figure 12

Ordination plot of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of observed colonies/taxa across the damage types. Symbols on the plane indicate observed colonies categorized by ADLFGs (A) and species/taxa (B). The vectors indicate the correlations between the selected variables and axes. The length and direction of the vectors represent the strength of the relationships between damage types and ADLFGs (A) and species/taxa (B). Damage types abbreviations: TN, Tissue Necrosis; CF, Coral Fragmentation; CD, Coral Disease; AO, Algal Overgrowth; SA, Sediment Accumulation. Fishing gear abbreviations: OBT, Otter board trawl net; SCN, Squid cast net; DGN, Drift gillnet; FTP, Fish trap; CTP, Crab trap; HPL, Handline and pole & line; SFH, Squid fishing hook.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) is widely distributed across underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand, with substantial spatial variation driven by human activities, fishing practices, and proximity to the mainland. The total of 138 ALDFG items recorded across 13 pinnacles aligns with global findings that geomorphological features such as pinnacles, seamounts, and reefs often act as gear-entanglement hotspots, trapping drifting or snagged fishing gear (Macfadyen et al., 2009; Richardson et al., 2022). The notably high occurrence at Hin Phum and Hin Jen Talay in Chumphon Province suggests that these sites may be particularly vulnerable due to nearshore location and frequent use by local fisheries. The predominance of polyethylene ropes, nylon lines, and ABS components reflects materials commonly used in modern fishing operations, consistent with patterns reported in Southeast Asian waters (Jambeck et al., 2015). The diversity of mesh sizes and gear types further confirms that multiple fisheries, especially hook & lines, otter board trawls, and squid fisheries, contribute to gear loss. Identification by experienced fishers indicated that handlines and pole-and-lines were the most frequently encountered ALDFG, echoing previous studies where small-scale fisheries were found to be major sources of gear loss due to frequent snagging on reef structures (Macfadyen et al., 2009).

Human use intensity strongly influenced ALDFG distribution. Pinnacles closer to the mainland had significantly higher occurrence, a pattern consistent with higher fishing density in nearshore waters (Richardson et al., 2022). Additionally, fishing-intensive sites contained significantly more ALDFG, whereas tourism-intensive sites exhibited reduced gear presence. This inverse relationship may reflect spatial segregation between tourism and fishing activities, as well as greater monitoring and control in areas frequented by recreational divers (Bergmann et al., 2017). ALDFG is often concentrated in areas with high fishing activity, which is generally dominated in nearshore waters. PCA and cluster analyses, underscores the influence of spatial fishing behavior on ALDFG composition. The PERMANOVA results reveal the difference of ALDGE composition between nearshore and offshore pinnacles reinforces the higher vulnerability of nearshore reefs to ALDFG diversity as nearshore fisheries often employ multiple gear types due to the richness of species and habitat variability (McClanahan & Mangi, 2004).

Ecologically, ALDFG imposed substantial damage on coral reef organisms, affecting 335 colonies across 24 coral species and multiple invertebrate taxa. A notable example is Hin Chen Thale pinnacle in Chumphon Province, where ALDFG was found to cover 23.79% of the surveyed reef area. Alarmingly, much of this gear was in direct contact with living coral colonies, raising concerns over chronic physical stress to reef-building species. The association of coral fragmentation primarily with otter board trawl nets, fish traps, and squid hooks is consistent with the high mechanical force exerted by these gear types when entangled or dragged (Wilcox et al., 2015).These observations align with prior studies conducted around Ko Tao, where Ballesteros et al. (2018) documented a high incidence of gill nets and monofilament lines entangling branching corals, particularly species in the genus Acropora. The presence of such gear on live corals can lead to tissue abrasion, partial mortality, or fragmentation, ultimately compromising coral growth, resilience, and reproductive capacity. Derelict gear inflicts multiple types of damage on reef-building corals, including tissue necrosis and partial mortality, fragmentation of coral branches, sediment entrapment leading to smothering, and algal overgrowth on damaged coral skeletons (Lamb et al., 2018), this also aligns with the study of ALDFG impacts on underwater pinnacles in Chumphon Province (Wongnutpranont et al., 2021). These impacts reduce coral recovery potential, hinder recruitment, and degrade structural complexity. As a result, reef resilience declines along with the availability of ecological niches for reef-associated organisms (Moschino et al., 2019; Figueroa-Pico et al., 2020; Gilman et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2022). The affected coral taxa, such as Porites, Dipsastraea, and Galaxea, serve as primary reef framework builders and play essential roles in providing habitat for reef fishes and invertebrates (Moberg and Folke, 1999; Darling et al., 2012; Graham and Nash, 2013; Yeemin et al., 2013).

The observed variation in ALDFG size and dimensions highlights differences in potential ecological impact. Larger gear types such as trawl nets, cast nets, drift gillnets and fish traps generally greater physical pressure on benthic communities, similar to patterns noted in other coral reef systems (Chiappone et al., 2005) as well as entanglement for several species (Mehrotra et al., 2024). Smaller items such as squid hooks and crab traps, while more frequently encountered, produce localized but repeated disturbances. Furthermore, the dominance of passive and low-cost gear types such as gill nets and handlines underscores the need to address small-scale fishing activities that may inadvertently contribute to the accumulation of ALDFG in reef habitats, particularly when these gears become damaged and turned into micro- and nano-plastics, and are carried by currents. These findings support the growing body of literature indicating that even low-intensity fisheries can produce substantial long-term ecological impacts when gear is abandoned, lost, or discarded (Macfadyen et al., 2009; Gilman et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2022; McIntyre et al., 2023).

Abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) plays a critical role in ghost fishing, whereby gear continues to entrap marine organisms indiscriminately, contributing to overexploitation and biodiversity loss. This persistent threat undermines the sustainability of fisheries and diminishes tourism revenues dependent on healthy marine ecosystems. Additionally, the accumulation of ALDFG may facilitate the colonization of invasive species and disrupt benthic community structure. These ecological impacts highlight the significant economic value of intact coral reef systems, as degradation caused by ALDFG not only reduces ecological functionality but also erodes coastal economic stability and livelihoods (Macfadyen et al., 2009; Moschino et al., 2019; Gilman et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2022; McIntyre et al., 2023).

Recent efforts in Thailand demonstrate the effectiveness of citizen science and community-based monitoring programs in tracking marine debris and ALDFG (Yeemin et al., 2021; Mehrotra et al., 2024). Initiatives such as campaigns encouraging fishers not to discard waste into the sea and the national marine debris monitoring platform have promoted data collection and raised awareness at local and regional levels. Effective management strategies include designating marine spatial zones that restrict certain fishing gear types, promoting biodegradable and GPS-tagged fishing gear, enhancing port-based retrieval programs and incentives, and integrating Ocean Accounts and Ocean Health Index (OHI) to align ecological indicators with socioeconomic planning (Halpern et al., 2012; Samhouri et al., 2012; Eikeset et al., 2018). Addressing ALDFG is crucial to achieving global and national conservation targets. Proper mitigation supports Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 14 (Life Below Water), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KM-GBF). It also reinforces Thailand’s commitments to sustainable, Net Zero and Nature Positive Tourism pathways.

Management recommendations

To mitigate the ecological impacts of ALDFG on coral reef ecosystems and promote sustainable marine resource management, a multi-tiered and collaborative approach is required. Based on empirical evidence from this study, other studies in Thai waters and global best practices, the following practical recommendations are proposed:

Enhance gear marking and tracking systems

Implement standardized gear marking schemes to improve traceability and accountability. This includes using biodegradable or color-coded tags linked to registered fishers, promoting the adoption of GPS-based gear tracking technology, particularly for longlines, traps, and gill nets (Guzman, 2021; Gilman et al., 2021). Such measures help identify the sources of lost gear and discourage deliberate gear abandonment.

Implement gear recovery incentives and cleanup programs

Support organized retrieval campaigns through community-based cleanups involving relevant agencies, local fishers, dive operators, and NGOs. Incentive mechanisms, such as “Gear Buy-Back” programs or reward systems for gear returns (Macfadyen et al., 2009; Guzman, 2021; Gilman et al., 2021; Sutthacheep et al., 2024) can reduce existing ALDFG burdens and foster stewardship behavior among stakeholders.

Introduce biodegradable and eco-friendly gear materials

Promote research, development, and subsidization of fishing gear made from biodegradable or less durable materials. These degrade faster in marine environments, minimizing long-term ecological damage (He et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2022). Regulations can mandate the use of escape panels and biodegradable twines in traps and nets to reduce ghost fishing effects.

Strengthen legal frameworks and enforcement mechanisms

Existing fisheries and environmental regulations should be revised to explicitly include penalties for gear abandonment to mandate the reporting of lost gear events, and to require inclusion of ALDFG mitigation in Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) for coastal development (Gilman et al., 2016; Ballesteros et al., 2018). Collaboration with local governments and community surveillance can enhance enforcement in marine protected areas, other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs), and high-risk zones.

Integrate ALDFG management into national ocean governance tools

ALDFG prevention and response strategies should be integrated into broader national frameworks such as Ocean Accounts (OA) to assess ALDFG-related impacts on natural capital losses, Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) to designate fishing zones and gear restriction areas, and the Ocean Health Index (OHI), which is used to monitor reef health, specifically as it is influenced by marine debris (Halpern et al., 2012; Samhouri et al., 2012; Yeemin et al., 2013; Eikeset et al., 2018; Sutthacheep et al., 2024).

Support stakeholder engagement and education

Raise awareness and build capacity among local stakeholders such as fishers, tourism operators, and local authorities through training on best practices for gear use and storage as well as ALDFG removal and management, public campaigns using local languages and cultural media, establishing participatory monitoring networks involving citizen scientists and coastal communities (Freiwald et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2020; Kasten et al., 2021).

Promote transboundary cooperation in ALDFG governance

Given the mobility of marine debris, regional coordination among ASEAN countries is essential for sharing databases on gear loss and debris hotspots, harmonizing policies on gear labeling, disposal, and port reception facilities (Richardson et al., 2022).

Conclusions

This present study aims to assess the occurrence of abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) and its impacts on the 13 underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand. A total number of 138 items of ALDFG were found, with strong variation among sites. Chumphon Province had the highest occurrence, particularly Hin Phum and Hin Jen Talay, while several pinnacles in Surat Thani had little or no ALDFG. Common materials included polyethylene, nylon lines, and ABS plastic from squid jigs. Six types of fishing gear were identified including otter board trawl nets, squid cast nets, drift gillnets, crab traps, handlines and pole & lines, and squid fishing hooks. Handlines and pole & lines were the most common ALDFG, followed by squid hooks and otter board trawl nets. ALDFG occurrence was strongly influenced by human activities and geography: pinnacles closer to the mainland tended to have more ALDFG occurrence, and sites with high fishing intensity had greater ALDFG occurrence, whereas tourism-heavy sites had less. Cluster and PCA analyses indicated two main groups of pinnacles: heavily impacted sites with higher gear diversity and lightly impacted sites with few or no ALDFG items. Nearshore pinnacles (<22 km from the mainland) had significantly more diverse ALDFG than offshore sites. Impact assessments revealed substantial impacts on coral reef communities. A total of 24 coral species and five invertebrate groups showed visible damage, dominated by tissue necrosis, sediment accumulation, and algal overgrowth. Porites lutea was the most affected species. Otter board trawl nets caused the broadest range of damage types, including fragmentation. The recommendations derived from this study offer a pragmatic framework to reduce ALDFG occurrence, mitigate its impacts on coral reef ecosystems, and strengthen sustainable marine resource governance. Success depends on the integration of science, community action, and policy enforcement across local to national scales.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

SP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MkS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. LJ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MnS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. WS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR) and the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) through the Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) and the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), as well as Ramkhamhaeng University (RU).

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the staff of the Marine Biodiversity Research Group, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Ramkhamhaeng University, for their generous support and invaluable assistance during fieldwork. We also acknowledge the contributions of citizen scientists, local community members, and volunteers who participated in marine debris monitoring and provided critical insights into local fishing practices. Their collaboration was instrumental to the success of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Agamuthu P. Mehran S. Norkhairah A. Norkhairiyah A. (2019). Marine debris: A review of impacts and global initiatives. Waste Manage. Res.37, 987–1002. doi: 10.1177/0734242x19845041

2

Angiolillo M. Fortibuoni T. (2020). Impacts of marine litter on mediterranean reef systems: from shallow to deep waters. Front. Mar. Sci.7, 581966. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.581966

3

Apete L. Martin O. V. Iacovidou E. (2024). Fishing plastic waste: Knowns and known unknowns. Mar. pollut. Bull.205, 116530. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116530

4

Baker J. D. Johanos T. C. Ronco H. Becker B. L. Morioka J. O’Brien K. et al . (2024). Four decades of Hawaiian monk seal entanglement data reveal the benefits of plastic debris removal. Science385, 1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.ado2834

5

Ballesteros L. V. Matthews J. L. Hoeksema B. W. (2018). Pollution and coral damage caused by derelict fishing gear on coral reefs around Koh Tao, Gulf of Thailand. Mar. pollut. Bull.135, 1107–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.08.033

6

Bergmann M. Lutz B. Tekman M.B. Gutow L. (2017). Citizen scientists reveal: Marine litter pollutes Arctic beaches and affects wildlife. Mar. Pollut. Bull.125(12), 535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.09.055

7

Brown B. E. Howard L. S. (1985). Assessing the effects of “stress” on reef corals. Adv. Mar. Biol.22, 1–63. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2881(08)60049-8

8

Castro P. Huber M. E. (2003). Marine biology (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Science, Engineering & Mathematics).

9

Chiappone M. Dienes H. Swanson D. W. Miller S. L. (2005). Impacts of lost fishing gear on coral reef sessile invertebrates in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Biol. Conserv.121, 221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2004.04.023

10

Chiappone M. White A. Swanson D. W. Miller S. L. (2002). Occurrence and biological impacts of fishing gear and other marine debris in the Florida Keys. Mar. Pollut. Bull.44(7), 597–604. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00290-9

11

Clarke K. R. Gorley R. N. (2001). Primer v5: User Manual/Tutorial. Primer-E Ltd., Plymouth, 91.

12

Cresswell B. J. Galbraith G. F. Harrison H. B. McCormick M. I. Jones G. P. (2023). Coral reef pinnacles act as ecological magnets for the abundance, diversity and biomass of predatory fishes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.717, 143–156. doi: 10.3354/meps

13

Darling E. S. McClanahan T. R. Côté I. M. (2012). Life histories predict coral community disassembly under multiple stressors. Glob. Change Biol.19, 1930–1940. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12191

14

Eikeset A. M. Mazzarella A. B. Davíðsdóttir B. Klinger D. H. Levin S. A. Rovenskaya E. et al . (2018). What is blue growth? The semantics of “Sustainable Development” of marine environments. Mar. Policy87, 177–179. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.10.019

15

Einarsson H. He P. Lansley J. (2023). Voluntary guidelines on the marking of fishing gear. (Rome: ). doi: 10.4060/cc4251en

16

English S. F. H. Wilkinson C. Baker V. (1997). Survey manual for tropical marine resources. ( Townsville, QLD: Australian Institute of Marine Science).

17

Fabricius K. E. (2005). Effects of terrestrial runoff on the ecology of corals and coral reefs: Review and synthesis. Mar. pollut. Bull.50, 125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.11.028

18

Figueroa-Pico J. Tortosa F. S. Carpio A. J. (2020). Coral fracture by derelict fishing gear affects the sustainability of the marginal reefs of Ecuador. Coral Reefs39 (3), 819–827. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-01926-6

19

Freiwald J. Meyer R. Caselle J. E. Blanchette C. A. Hovel K. Neilson D. et al . (2018). Citizen science monitoring of marine protected areas: Case studies and recommendations for integration into monitoring programs. Mar. Ecol.39, e12470. doi: 10.1111/maec.12470

20

Galbraith G. F. Cresswell B. J. McCormick M. I. Bridge T. C. Jones G. P. (2021). High diversity, abundance and distinct fish assemblages on submerged coral reef pinnacles compared to shallow emergent reefs. Coral Reefs40, 335–354. doi: 10.1007/s00338-020-02044-z

21

Galbraith G. F. Cresswell B. J. McCormick M. I. Bridge T. C. Jones G. P. (2022). Contrasting hydrodynamic regimes of submerged pinnacle and emergent coral reefs. PloS One17, e0273092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273092

22

Gilman E. Chopin F. Suuronen P. (2016). Abandoned, lost and discarded gillnets and trammel nets: methods to estimate ghost fishing mortality, and the status of regional monitoring and management. Scientific Reports11, 86123.

23

Graham N. A. J. Nash K. L. (2013). The importance of structural complexity in coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs32 (2), 315–326. doi: 10.1007/s00338-012-0984-y

24

Gilman E. Musyl M. Suuronen P. Chaloupka M. Gorgin S. Wilson J. et al . (2021). Highest risk abandoned, lost and discarded fishing gear. Sci. Rep.11, 7195. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86123-3

25

Guzman R. J. (2021). Status, trends and best management practices for abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) in Asia and the Pacific. Mar. Plast. pollut. Rule Law168. SulistiawatiLinda YantiEisma-OsorioRose-Liza. (eds.) (168–203).

26

Hajisamae S. Yeesin P. Chaimongkol S. (2006). Habitat utilization by fishes in a shallow, semi-enclosed estuarine bay in southern Gulf of Thailand. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci.68, 647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2006.03.020

27

Halpern B. S. Longo C. Hardy D. McLeod K. L. Samhouri J. F. Katona S. K. et al . (2012). An index to assess the health and benefits of the global ocean. Nature488, 615–620. doi: 10.1038/nature11397

28

He P. Chopin F. Suuronen P. Ferro R. S. T. Lansley J. (2021). Classification and illustrated definition of fishing gears (FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 672) (Rome: FAO). doi: 10.4060/cb4966en

29

Hughes T. P. Kerry J. T. Álvarez-Noriega M. Álvarez-Romero J. G. Anderson K. D. Baird A. H. et al . (2017). Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature543, 373–377. doi: 10.1038/nature21707

30

Jambeck J. R. Geyer R. Wilcox C. Siegler T. R. Perryman M. Andrady A. et al . (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science347, 768–771. doi: 10.1126/science.1260352

31

Kaandorp M. L. A. Lobelle D. Kehl C. Dijkstra H. A. van Sebille E. (2023). Global mass of buoyant marine plastics dominated by large long-lived debris. Nat. Geosci.16, 689–694. doi: 10.1038/s41561-023-01216-0

32

Kasten P. Jenkins S. R. Christofoletti R. A. (2021). Participatory monitoring—A citizen science approach for coastal environments. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.681969

33

Kelly R. Fleming A. Pecl G. T. von Gönner J. Bonn A. (2020). Citizen science and marine conservation: a global review. Philos. Trans. R. Soc B375, 20190461. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2019.0461

34

Lamb J. B. Willis B. L. Fiorenza E. A. Couch C. S. Howard R. Rader D. N. et al . (2018). Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs. Science359, 460–462. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3320

35

Letourneur Y. Kulbicki M. Labrosse P. (1998). Spatial structure of commercial reef fish communities along a terrestrial runoff gradient in the northern lagoon of New Caledonia. Environ. Biol. Fishes51, 141–159. doi: 10.1023/A:1007489502060

36

Lovell T. A. (2023). Understanding the drivers, scale and impact of abandoned, lost and otherwise discarded fishing gear in small-scale fisheries: an Eastern Caribbean perspective [Original Research]. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1139259

37

Macfadyen G. Huntington T. Cappell R. (2009). Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear.UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No.185. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, No. 523. Rome, UNEP/FAO. 115 pp. Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d7a3fc14-912f-4302-b706-7e39c34f41e0/content/i0620e.htm.

38

McClanahan T. R. Mangi S. C. (2004). Gear-based management of a tropical artisanal fishery based on species selectivity and capture size. Fisheries Manage. Ecol.11, 51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2004.00358.x

39

McIntyre J. Duncan K. Fulton L. Smith A. Goodman A. J. Brown C. J. et al . (2023). Environmental and economic impacts of retrieved abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear in Southwest Nova Scotia, Canada. Mar. pollut. Bull.192, 115013. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115013

40

Mehrotra R. Monchanin C. Desmolles M. Traipipitsiriwat S. Chakrabongse D. Patel A. et al . (2024). Assessing the scale and ecological impact of derelict and discarded fishing gear across Thailand via the MARsCI citizen science protocol. Mar. pollut. Bull.205, 116577. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116577

41

Meixia Z. Kefu Y. Qiaomin Z. Qi S. (2008). Spatial pattern of coral diversity in Luhuitou fringing reef, Sanya, China. Acta Ecol. Sin.28, 1419–1428. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2032(08)60051-7

42

Moberg F. Folke C. (1999). Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ.29, 215–233. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00009-9

43

Moschino V. Riccato F. Fiorin R. Nesto N. Picone M. Boldrin A. et al . (2019). Is derelict fishing gear impacting the biodiversity of the Northern Adriatic Sea? An answer from unique biogenic reefs. Sci. Total Environ.663, 387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.332

44

Munro C. (2005). “ Diving systems,” in Methods for the study of marine benthos, 3rd ed. Eds. EleftheriouA.McIntyreA.. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). doi: 10.1002/9780470995129.ch4

45

Nybakken J. W. Bertness M. D. (2005). Marine biology: an ecological approach.

46

Palummo V. Milisenda G. Pica D. Canese S. Salvati E. V. A. SpanÒ N. et al . (2024). Improving the knowledge base of Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems’ distribution in the Amendolara Bank (Ionian Sea). Mediterr. Mar. Sci.25, 220–230. doi: 10.12681/mms.35680

47

Pillai R. R. Lakshmanan S. Mayakrishnan M. George G. Menon N. (2024). Impact of marine debris on coral reef ecosystem of Palk Bay, Indian Ocean. Aquat. Conserv.34, e4160. doi: 10.1002/aqc.4160

48

Putsa S. Boutson A. Tunkijjanukij S. (2016). Comparison of ghost fishing impacts on collapsible crab trap between conventional and escape vents trap in Si Racha Bay, Chon Buri province. Agric. Nat. Resour.50(2), 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.anres.2015.07.004

49

Rades M. (2024). Long-term effects of microplastics on the behaviour and physiology of reef-building corals. Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, Gießen, Germany.

50

Ramos S. Espincho F. Rodrigues S. M. Pereira R. Silva D. Rivoira L. et al . (2025). An integrated approach to assessing the potential of plastic fishing gear to release microplastics. Water17, 1439. doi: 10.3390/w17101439

51

Rangseethampanya P. Chamchoy C. Yeemin T. Ruengthong C. Thummasan M. Sutthacheep M. (2021). Coral community structures on shallow reef flat, reef slope and underwater pinnacles in Mu Ko Chumphon, the Western Gulf of Thailand. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.4, 1–7.

52

Richardson K. Hardesty B. D. Wilcox C. (2019). Estimates of fishing gear loss rates at a global scale: A literature review and meta-analysis. Fish Fish.20, 1218–1231. doi: 10.1111/faf.12407

53

Richardson K. Hardesty B. D. Vince J. Wilcox C. (2022). Global estimates of fishing gear lost to the ocean each year. Sci. Adv.8, eabq0135. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abq0135

54

Riyanto M. Fajri R. M. Yuwandana D. P. Wahju R. I. Purbayanto A. Richardson K. et al . (2025). Estimates of gear loss and contributing factors in trap fisheries in coastal waters: A case study from the Seribu Islands, Indonesia. Fisheries Res.289, 107500. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2025.107500

55

Royer S.-J. Corniuk R. N. McWhirter A. Lynch H. W. Pollock K. O’Brien K. et al . (2023). Large floating abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) is frequent marine pollution in the Hawaiian Islands and Palmyra Atoll. Mar. pollut. Bull.196, 115585. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115585

56

Sala E. Mayorga J. Bradley D. Cabral R. B. Atwood T. B. Auber A. et al . (2021). Protecting the global ocean for biodiversity, food and climate. Nature592, 397–402. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03371-z

57

Samhouri J. F. Lester S. E. Selig E. R. Halpern B. S. Fogarty M. J. Longo C. et al . (2012). Sea sick? Setting targets to assess ocean health and ecosystem services. Ecosphere3, 1–18. doi: 10.1890/ES11-00366.1

58

Spurgeon J. P. (1992). The economic valuation of coral reefs. Mar. pollut. Bull.24, 529–536. doi: 10.1016/0025-326X(92)90704-A

59

Spurgeon J. P. G. (1999). “ Economic valuation of damages to coral reefs,” in Coral reefs: marine wealth threatened ( National University of Mexico, Cancun, Mexico).

60

Suebpala W. Chuenpadee R. Nitithamyong C. Yeemin T. (2017). Ecological impacts of fishing gears in Thailand: Knowledge and gaps. Asian Fish. Sci.30, 284305. doi: 10.33997/j.afs.2017.30.4.006

61

Suebpala W. Yeemin T. Sutthacheep M. Pengsakun S. Samsuvan W. Nitithamyong C. (2021). Impacts of fish trap fisheries on coral reefs near Ko Mak and Ko Kut, Trat Province, Thailand. J. Fish. Environ.45 (1), 4663.

62

Sukhsangchan C. Phuynoi S. Monthum Y. Whanpetch N. Kulanujaree N. (2020). Catch composition and estimated economic impacts of ghost-fishing squid traps near Suan Son Beach, Rayong province. Thailand. ScienceAsia46 (2020), 8792. doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2020.014

63

Sutthacheep M. (2022). Assessing coral communities on underwater pinnacles as new marine protected areas at Ko Tao, Surat Thani Province. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.5, 25–43.

64

Sutthacheep M. Chamchoy C. Pengsakun S. Klinthong W. Yeemin T. (2019). Assessing the resilience potential of inshore and offshore coral communities in the Western Gulf of Thailand. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.7, 408. doi: 10.3390/jmse7110408

65

Sutthacheep M. Jungrak L. Chamchoy C. Aunkhongthong W. Sasithorn N. Suebpala W. et al . (2024). Low impacts of coral bleaching in 2024 on the underwater pinnacles from Krabi Province, the Andaman Sea. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.7, 1–14.

66

Turak E. DeVantier L. (2019). Reef-building corals of the upper mesophotic zone of the Central Indo-West Pacific. In. Mesophotic Coral Ecosyst. (Cham), 621–651. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92735-0_34

67

Tuttle L. J. Donahue M. J. (2022). Effects of sediment exposure on corals: A systematic review of experimental studies. Environ. Evid11, 4. doi: 10.1186/s13750-022-00256-0

68

UNEP (2006). Ecosystems and biodiversity in deep waters and high seas. (Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme).

69

Veron J. E. N. (2000). Corals of the world Vol. 1 (Townsville, Australia: Australian Institute of Marine Science), 463–490.

70

Vodopia D. Verones F. Askham C. Larsen R. B. (2025). Ghost fishing catch estimates based on annual retrieval operations in Norwegian waters. Fisheries Res.292, 107599. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2025.107599

71

Weber M. de Beer D. Lott C. Polerecky L. Kohls K. Abed R. M. M. et al . (2012). Mechanisms of damage to corals exposed to sedimentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.109, E1558–E1567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100715109

72

Wilcox C. Mallos N. Leonard G. H. Rodriguez A. Hardesty B. D. (2015). Using expert elicitation to estimate the impacts of plastic pollution on marine wildlife. Mar. Policy65, 107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.10.014

73

Wongnutpranont A. Suebpala W. Sutthacheep M. Pengsakun W. Yossundara N. Khawsejan T. et al . (2021). Derelict fishing gears and other marine debris on coral communities on underwater pinnacles in Chumphon Province, Thailand. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.4(2), 28–37

74

Yang C. M. (2022). Stakeholders’ perspectives for taking action to prevent abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear in gillnet fisheries, Taiwan. Sustainability15, 318. doi: 10.3390/su15010318

75

Yeemin T. Pengsakun S. Rangseethampanya P. Yossundara N. Yossundara S. Sutthacheep M. (2021). A new method for citizen science to monitor coral reefs in Thai waters. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.4, 11–20.

76

Yeemin T. Pengsakun S. Yucharoen M. Klinthong W. Sangmanee K. Sutthacheep M. (2013). Long-term changes in coral communities under stress from sediment. Deep-Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr96, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.04.019

77

Yeemin T. Ruengsawang N. Sudara S. (1999). “ Coral reef ecosystem in Thailand,” in Proc. First korea–Thailand joint workshop on comparison of coastal environment ( Seoul Natl. Univ., Seoul, Korea), 30–41.

78

Yeemin T. Sudara S. Krairapanond N. Silsoonthorn C. Ruengsawang N. Asa S. (2001). International coral reef initiative country report: Thailand Vol. 7 (Cebu, Philippines: ICRI Regional Workshop for East Asia).

79

Yeemin T. Sutthacheep M. Aunkhongthong W. Chamchoy C. Jungrak L. Chaithanavisut N. et al . (2024). Community structure of underwater pinnacles in Mu Ko Si Chang, the Upper Gulf of Thailand. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.7, 15–35.

80

Yeemin T. Sutthacheep M. Pengsakun S. Klinthong W. Aunkhongthong W. Limpichat J. et al . (2023). Diversity of scleractinian corals, microbenthic invertebrates and reef fish on underwater pinnacles in Surat Thani Province, Thailand. Ramkhamhaeng Int. J. Sci. Technol.6, 71–85.

Summary

Keywords

abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), coral damage, marine debris, sustainable fisheries, underwater pinnacles

Citation

Pengsakun S, Yeemin T, Sutthacheep M, Jungrak L, Klinthong W, Aunkhongthong W, Chamchoy C, Sukkeaw M, Odthon S and Suebpala W (2026) Environmental effects of plastic pollution from lost, discarded, and abandoned fishing gear on underwater pinnacles in the Gulf of Thailand. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1670284. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1670284

Received

21 July 2025

Revised

26 November 2025

Accepted

09 December 2025

Published

21 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Francesco Saliu, University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy

Reviewed by

Nandini Menon N, Nansen Environmental Research Centre, India

Harsha Krishnankutty, Central Institute of Fisheries Technology (ICAR), India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Pengsakun, Yeemin, Sutthacheep, Jungrak, Klinthong, Aunkhongthong, Chamchoy, Sukkeaw, Odthon and Suebpala.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wichin Suebpala, wichin.s@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.